Lakshana Granthas – continued

10. The Nrttaratnavali of Jaya Senapati

Evolution of Dance During the medieval period

The medieval period spanning the Twelfth to the Fifteenth century was a very significant period in the history of Indian Dancing. And, the developments that took place during this period cast their influence on the future course of Indian Dancing. And, they were also instrumental for the emergence of numerous Dance forms, in the different regions of the country.

To start with; it was during this period that Dance along with Music (which were both clubbed under the term Samgita) emerged out of the shadows of the Drama; and, began to be recognized and discussed in their own right , as independent Art-forms rather than as adjuncts to Drama.

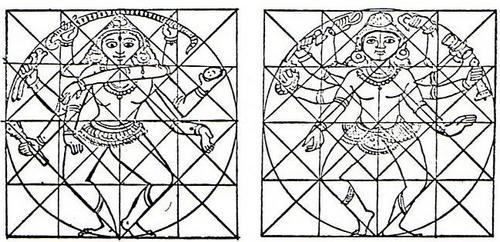

Dance, in the Natyashastra, was an ancillary part (Anga) or one of the ingredients that lent elegance and grace to theatrical performance; and, it was not yet an independent art-form, by itself. Further, Bharata had discussed Dance, mainly, in terms of Nrtta, pure, abstract and beautiful dance, performed in tune with the rhythm and tempo, to the accompaniment of vocal and instrumental music.

The Nrtta was described in terms of the motion of the limbs (Anga-vikshepa), the graceful composition of the limbs – gatram vilasena kshepaha ; the beauty of its form; the balanced geometrical structure; creative use of space; and rhythm (time). And, therefore, Nrtta was meant to be a beautiful visual presentation, as an auxiliary to Natya (Drama), pleasing the eye (Shobha hetuvena). But, it was not intended to give expression to thoughts, emotions or even to indicate objects.

Bharata, at that stage, is credited with having devised a more creative Dance-form, which was adorned with elegant, evocative and graceful body-movements of the Nrtta; performed in unison with attractive rhythm and enthralling music; in order to effectively interpret and illustrate the lyrics of a theatrical song; and, also to depict the emotional content of a dramatic sequence. Thus, Bharata, in effect, fused the rhythm and fluidity of Nrtta with the evocative grace and expressions of the Abhinaya.

But, Bharata had not assigned a name to that resultant new Art-form. It was only after the Eleventh-Twelfth century that this delightful and the most enjoyable of all Art-forms created by Bharata (Bhartopajanaka) came to be celebrated as Nrtya.

Bharata had not also classified what later came to be known as Nrtya into Tandava and Lasya types. Therefore, the terms Nrtya and Lasya do not appear either in the Natyashastra or in its early commentaries. Even Abhinavagupta (11th century) avoids using the term Nrtya. It was only during the later times (that is, during the period about which we are talking now) that Nrtya gained an independent recognition as an expressive, eloquent representational Art, which projects human experiences, with amazing fluidity and grace.

It was beginning with this period that Nrtya, a blend of two well studied, well developed and well codified Art forms – the dance of Nrtta and Abhinayas of Natya –advanced vibrantly, imbibing on its way, numerous novel features; and, soon became hugely popular among all classes of the society. It gained recognition as the most delightful Art-form; and in particular, as the most admired phrase or form of Dance.

*

It was also during this period that the element of Lasya came into prominence; and, it also developed in different regions assuming varied forms (Desi-Lasyanga).

*

By this time (say, the 12th century) the influence of the Natyashastra was getting distant and weaker; and, most writers of this period followed the interpretations of Abhinavagupta (11th century).

Further, Natya, the Sanskrit Drama, by then, was beginning to lose its appeal among the common people.

*

The tradition, techniques and definitions as prescribed and codified in the Natyashastra came to be classified as the Marga, the classic or the pristine form of Dance, as distinct from the innovative regional styles called Desi.

At the same time, those dance forms which adhered to the established regulations and conventions of the Marga; and, which had a definite structure were termed and classified as Nibaddha. And, those free-flowing dance forms, which were spontaneous, unregulated, unstructured and not bound by any rules, were treated as Anibaddha.

Anibaddha also meant allowing the dancer considerable latitude in devising body movements that best suited the aesthetic and emotional content of the theme. And, it also made room for enterprise to come up with fresh idioms of expressions.

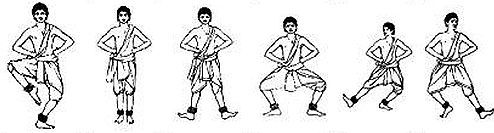

And, because such spontaneous Desi Dances , unique to each region, were practiced enthusiastically by the common people ; and, were gaining ascendency, the writers and commentators of this period, in their texts, assigned greater importance to the descriptions of the postures, feet positions and movements (Sthanaka, Cari and Karanas) of the regional and popular Desi styles.

*

Commencing with this period, there began the practice of composing texts and treatise, which were wholly devoted to the discussions on the theory, practice and techniques of Dance, as relevant to the contemporary methods of training, learning and performance. Until then, most of the texts and treatise which dealt with Music, primarily, also talked about dance, in comparatively briefly manner, towards the end.

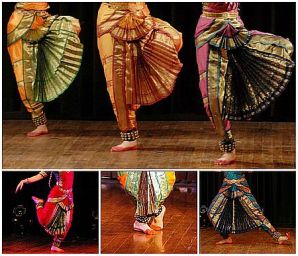

Such specialized texts of this period covered not only the well regulated dance forms (Margi), but also the individual Desi Dances (Desi-Nrtta) and the group dances (Pindibandhas) of the Desi types like Rasaka, Perani, Carcari, Daṇḍaras, Raslīlā , and other folk dances of similar nature, some of which have survived as dramatic group presentations.

Though the texts usually commenced with descriptions of the Marga features, the contemporary Desi dance-forms were given a more detailed treatment, while illustrating various postures and movements.

By about the twelfth century, the differences as also the relationship between the Nrtta (pure dance) and Nrtya (Nrtta with Abhinaya) were clearly established. And, those dance formats, in combination with music, were suitably applied and integrated into the performance of the Dance Dramas.

That marked the emergence of dance-dramas of the Uparupaka class, as a credible format of Dancing. Here, Dance was not a mere ornament as in the age of Bharata; but, it permeated the entire body of presentation. This was an altogether new genre of Dance oriented Dramas.

The concepts of Padartha-Abhinaya and Vakyartha-Abhinaya seemed to have been the basis for distinction between Rupakas and Uparupakas. According to Dr, V Raghavan:

In the Rupaka a full story was presented through all the dramatic requirements and resources fully employed; but in the Uparupaka, only a fragment was depicted and even when a full theme was handled, all the complements of the stage were not present. the Uparupaka lacked one or other or more of the four Abhinayas, thus minimizing the scope for naturalistic features (Lokadharmi); and, resorting increasingly to the resources of Natyadharmi. Thus in some, the element of speech, Vacika-abhinaya, was omitted, though the representation included a continuous theme and the portrayal of different characters by different actors or dancers.

*

Such forms of Uparupakas, composed in very attractive and entertaining formats, with the predominance of the elements of the music and dance, accompanied by soulful songs, interpreting the emotional contents of the song through Abhinaya or gestures, soon gained immense popularity.

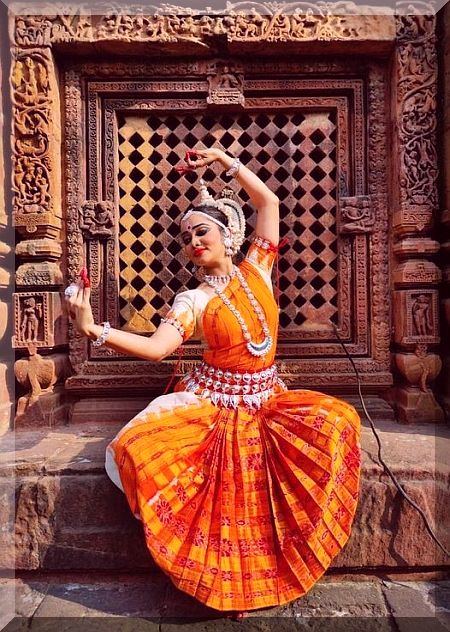

The Uparupakas, of the dance-drama type, began to develop in many regional popular styles. And, each of its derivative forms such as Kathak, Odissi, Manipuri, and Kuchipudi and so on, formulated its own tradition, ethos and idioms of expressions , anchored in its own regional and cultural background; and rooted in its own philosophy and outlook.

The features that were common to all those diverse types of regional dance forms (Desi Nrtta) could , in short, said to be :

:- the prominence assigned to the narration of the theme;

:- the dominance of Natya-dharmi mode of presentation;

:- more space and time given to dances depicting Srngara aspects performed to appropriate music, Laya (tempo) and Taala (time-units, beats);

:- employment of all the four Abhinayas in varying degrees;

:- making a distinction between the Nrtta and the Nrtya, and maintaining their distinctive features while executing the respective elements in the performance;

:- taking care to see that the Nrtta aspect, particularly the individual dance movements and postures, are governed by the special techniques developed by each school of Desi-Dance;

:- and, recognition of both the Ekaharya (solo-where a single dancer enacts the role of several characters) and Anekaharya (where several actors participate to enact their respective role) modes of presentation.

And, since then, such dance and music oriented Uparupakas have come to stay and flourish both in the solo and in the group dance forms; and, even have come to occupy a central position within the contemporary world of Art. They have also successfully retained their regional and cultural identity, while carrying forward their tradition to the present time.

[The early twentieth century witnessed the revival of the Marga tradition, thanks to the efforts of a group of artists, scholars and art-lovers. That regenerated Art-form, is celebrated by the name of Bharatanatya; and, its scope and content extends beyond Bharata’s concepts and techniques. It has brought within its ambit the formats of Nrtta, Nrtya and Natya, in addition to the Uparupaka class of Dance Dramas. Further, though it is, essentially, rooted in the principles of Natyashastra, it has adopted many features and techniques from the regional dance traditions (Desi Nrtta) ; and, has thus enlarged its repertoire; and, acquired many dimensions.

Though its teachers and the learners , alike, emphasize the importance of adhering to and preserving the purity of the Marga tradition; and, its continuation, Bharatanatya, in its practice, has brought within its fold some innovative techniques and refreshing modes of expression, in tune with the advancing times. These could be called as ‘context-sensitive interactions’.]

The Nrttaratnavali

The Nrttaratnavali of Jaya Senapati (13th century) epitomizes the characteristic features of the Indian Dance tradition of the medieval period.

The Nrttaratnavali is the first text (perhaps the only text) of this period that is entirely devoted to the discussion on the subject of Dance. All the Eight Chapters of the text discuss Dance in its varied forms; and, the aspects of vocal or instrumental music is mentioned only in the context of Dance.

Though it commences with the discussion on the Angika-Abhinaya as per the norms specified in the Natyashastra (but, actually, as per Abhinavagupta), Nrtta- ratnavali later covers, in detail, the aspects of the Desi Nrtta, on which it lays greater emphasis. In the process, the focus of the work is more on the Desi Nrtta, than on Nrtya with its Abhinaya aspects. And, that, perhaps, is the reason why the text was named as Nrtta- ratnavali.

It would be fair to say; the Nrttaratnavali went beyond the Natyashastra in its descriptions of the Karanas of the Marga Class. The Nrttaratnavali is perhaps, one of the few texts of its period, which presents graphic details for execution of a Karana along with its associated Caris (feet position), Hasthas (hand-gestures) and Pada-bedha (feet movements) , by following which a Karana could be reproduced successfully.

Apart from that; Jaya Senapati quotes the views of earlier writers on the treatment of Karanas, providing a broader view on the subject of evolution of the Karanas.

Thus, the Nrttaratnavali, apart from its theoretical merit, is also of great practical value.

*

The King Someshvara, (12th century), in his Manasollasa, was the first writer to recognize and to describe the Desi Sthanas, Caris and Karanas. He was followed by Sarangadeva (first half of 13th century), who in his Sangita-ratnakara, gave the Desi Nrtta a more detailed treatment. And, Parsvadeva (a Jain Acharya of 12th or early 13thcentury) in his Sangita-samarasya also recorded some Desi Dances.

But, it was indeed Jaya Senapati (second-half of thirteenth century), who in his Nrttaratnavali, accorded a systematic and an elaborate treatment to all aspects of Desi Nrtta.

Jaya Senapati’s work covers, in main, the Nrtta type of Dance forms and their movements as prevalent during the time of the King Ganapati Deva (13th century). Jaya Sena was the first author and commentator to write, in detail, about the dances prevalent in Andhra Pradesh.

He enumerates verities of new forms and techniques of Desi Nrtta; the entire sequence of Desi Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas; how to perform the entire form of dance; and, clarifies the major points of dance and artistic techniques. One could say that the Nrttaratnavali covers all areas of the art of Desi-Dance, its techniques, composition, and aesthetics and so on.

The Nrttaratnavali is one of the early manuals on dancing to describe Lasya, in detail. It makes Lasyanga the very heart of the Uparupakas, the minor type of Dance-dramas, narrating an incident or a segment of a theme, usually, related to the sports of Krishna (Krishna Lila). These Rasaka types of dances depict the graceful, delicate and love-laden-playful (Lalitha) dance movements associated with Srngara Rasa.

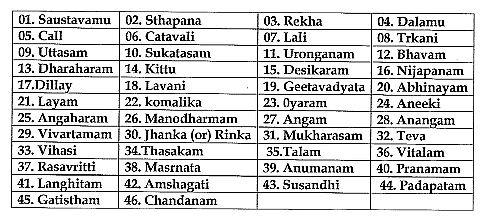

Though the text initially enumerates the Lasya elements of Marga Class, as they appear in the Natyashastra, it then goes to elaborate on the Desi-Lasya, listing as many as forty-six regional variations – Desi Lasyangas (please check page 17) of such Lasya type.

These Desi Lasyangas are presented, mainly, through the Angika (dance movements), with hardly any Vachika Abhinaya (speech). The Nrttaratnavali describes Lasya the graceful delicate (Vanapu, Vayyaram) dance performed by women; as also the Perani, a form of Tandava the vigorous forceful dance of men.

The Desi-Lasyangas enumerated in the Nrttaratnavali became the core of the Lasya dance tradition of Andhra Pradesh. Many of such Lasyangas can be seen in the performance of Padams, Javalis etc., of Kuchipudi dance form.

Therefore, Nrttaratnavali is said to mark a significant stage in the development of the dance-literature. The Dance-manuals of the later period, following the lead given by Jaya Senapati, accorded greater importance to Desi Dance sequences that were in practice during the contemporary times, instead of merely reiterating the norms of the Natyashastra.

Jaya Senapati

Jaya Senapati / Jaya Senani / Jaya Sena / Jaya Senadi-natha /Jayana / Jayappa Nayaka / Jaya-charya / Jayappa Nayadu , the author of Nrttaratnavali, was a Commander of the Elephant Forces (Gaja-Sena-pathi) as also a Elephant-trainer (Gaja-sadhanika) in the service of the Kakatiya King Ganapati Deva (1199-1262), considered as the greatest among the Kakatiya Kings, who ruled from Warangal (Andhra-Maha-Nagara). Jaya Senapati, later served the legendary Queen Maharani Rudrama Devi (ruled 1262-1289), the daughter and the successor of Ganapati Deva.

[The Kakatiyas, who were vassals of the Chalukyas of Kalyani, became independent after the defeat of the Chalukyas at the hands of the Kalachuris, towards the end of the 12th century. Thereafter, the Kakatiyas rose to power and ruled over a large part of the Deccan for nearly three centuries.]

[Gajasiksa or Gaja-sastra or Hasti Sastra, a special branch of study dealing the martial strategy of elephants, was an important component in devising military tactics. A medieval text Gajasiksa, said to have been composed by an unknown author who went by the name Naradamuni, deals with the subject of capturing wild and robust elephants and training them to take part in battles. In the introduction to Gajasiksa, edited by Dr. E.R. Sreekrishna Sarma, Shri S. Sankaranarayanan mentions: The elephant-warfare seems to have been well developed in the South, particularly in the Andhra Pradesh, since the sixth century AD. During this period many monarchs styled themselves as having won spectacular victories in the fierce battle of four-tusked elephants.]

It is said; Jayana hailed from a family of Chieftains (Ayya-kula sanjata) who, at one time, were in charge of the Velanadu region, under the Telugu Cholas who ruled from Chandavolu. And, later, Jayana’s father Pinna-Choda Nayaka was in charge of Divi Island (Divi-seema) in the Krishna Delta, under Kakatiya King Ganapati Deva.

The King Ganapati Deva, an enlightened ruler and a patron of Arts, having noticed the intelligence , politeness and studiousness of Jayana, as also his desire to learn , took the boy Jayana under his care; and supervised his education. He arranged for Jayana’s Dance –education under the Natyacharya Gundamatya.

The King Ganapati Deva later appointed Jaya as the Nayaka of the Tamrapuri (said to be in Guntur District); and honoured him with the title ’Vairigodhuma Gharatta’

Jayana though an army commander by profession, was at heart a true Artist; and, was a well qualified Nartaka. He grew to become a Natyacharya, a Master who imparted training to the aspirants desirous of learning Dance. He was also a qualified musician and a composer. He has to his credit the Geeta-ratnavali, a treatise on Music, as a companion volume to his Nrtta- ratnavali, a manual on Dance.

Jaya Sena mentions that the text of the Nrtta-ratnavali was completed during – Vaivasvata Manvantara, Kaliyuga, Prathama Pada, after 4355 years during this period, and in the year named Ananda-nama-Samvathsara – which equates to the year 1253 -54 AD. It is said; by then Jaya Sena had grown into a wise and erudite scholar of about sixty years of age.

He reveals that it was not easy for him to compose Nrtta- ratnavali, a work of a highly technical nature, in Sanskrit verses. He had to study much, work hard and had to consult many experts in various fields.

Jaya Sena mentions that he studied the Natyashastra of Bharta Muni , diligently , spending hours upon hours poring over its tedious text; delving deep into the depths of its numerous commentaries; debating endlessly with the well disposed scholars, each adhering to his tradition; learning from many Gurus the secrets of the Shastra; and, above everything else he had the faith he could successfully accomplish his task, blessed with the infinite mercy and Grace of Lord Shiva , the Supreme Natyacharya. (Nr. Rv. 1.12).

[Abhyasate Bhartokti-bhanghisu, bahau-vyakya patesu sramath, samvadath Guru sampradaya suhrudam, Shambho prasadadapi, jnathava shastra rahasyam, nirmitamidam maharthanvitam, nasyath kasya hitaya shasvata yashasam rakshanam lakshanam – Nr.Rv. 1.12]

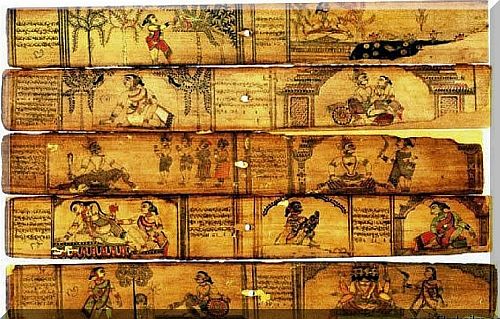

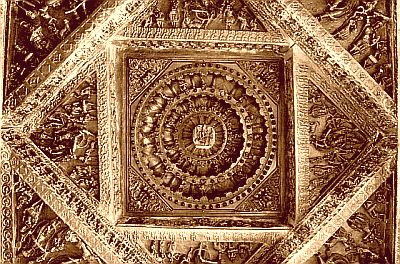

He also studied the Dance sculptures of the Ramappa Devalaya, dedicated to Lord Shiva, as Ramalingeswara, at Warangal, depicting various Karanas. It was built during 1213 AD by a General Recherla Rudra, during the reign of the Kakatiya ruler Ganapati Deva, under whom Jaya Sena served.

The temple is known for its elaborate carvings that adorn the walls, pillars and the ceilings of its marvelous edifice. In addition, there are images of Shiva in his various forms; the sculptures of Naginis, musicians; and, the bracket-figures of dancers executing various Karanas.

[ As regards the bracket-figures (Sala-bhanjika) , some readers have made an interesting observation.

One of the Lady-figures is shown wearing a high-heeled platform-type of footwear, perhaps to make her look taller. Considering that the figures were sculpted in the eleventh century, it is indeed amazing.

***

Apart from the study of the traditional texts, Jaya Sena mentions that he learnt much from the practicing Devadasis, the temple-dancers. For instance; on the question ‘how to bend the knees’, he says : The danseuse must reduce her height by bending at the knees and groin by four, eight or twelve angulas as measured by the first section of her forefinger. Jaaya Senapati strikes a fine balance between individual and ‘class-room’ training methods.

And, he put that practical-learning to good use. He cites as many as three hundred dances performed by the Devadasis at the Natya Mantapas of various temples, as illustrations in his text Nrtta- ratnavali.

And, in return, Jaya Sena trained many young Devadasis, along with the Raja-Nartakis who danced at the King’s Court.

The Nrtta-ratnavali is thus the fruit of Jaya Sena’s dedication to his Art, earnestness and long years of learning from various sources. He remarks: Lord Shiva, verily, is formless (amurta); but, since he loved Dancing, he, in his boundless compassion (karunya) and love for the beings, assumed the form (murta) of Nrtta, in order to be accessible to the aspirants. For my humble-self, the Nrtta, indeed, is Shiva incarnated (Shiva-svarupam).

Structure of the Nrtta-ratnavali

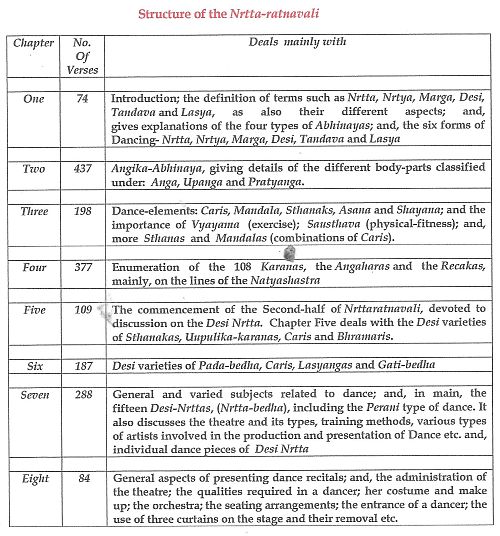

The Nrtta-ratnavali is a comprehensive study of dance, structured into Eight Chapters (Asta-adhyayi). It has, in all, about 1700 verses (Slokas).

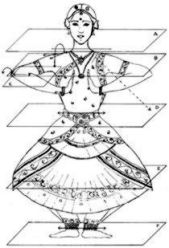

All the Eight Chapters of the text deal with dance exclusively. The first Four Chapters describe the Angika Abhinaya, generally following the Natyashastra of Bharata (which is the Marga tradition). And, the Four Chapters, in the latter half of the text, are devoted to the Desi Nrtta, keeping in view the contemporary practices , as prevalent during the Kakatiya reign. These include Folk dance forms like Perani, Prenkhana, Suddha Nartana, Carcari, Rasaka, Danda Rasaka, Shiva Priya, Kanduka Nartana, Bhandika Nrityam, Carana Nrityam, Chindu, Gondali and Kolatam.

The description of the traditional regional dances differs from that of the Marga tradition in two ways: first, by putting its emphasis on the style of presentation rather than on the content of the composition; and, second, by concentrating on the use of more acrobatic movements. Their treatment should be seen as a different stylistic approach that grew through the course of time into a separate branch out of the same basic or the main Art form or tradition .

In short:

The Chapter one , which serves as a sort of introduction, provides the definition of terms such as Nrtta, Nrtya, Marga, Desi, Tandava and Lasya, as also their different aspects ; and, gives explanations of the four types of Abhinayas.

The Chapter Two deals with Angika-Abhinaya, giving details of the different body-parts classified under: Anga, Upanga and Pratyanga.

The Chapter Three explains the Dance-elements: Caris, Mandala, Sthanaks, Asana and Shayana; and the importance of physical fitness (Anga saustava).

The Chapter Four enumerates the 108 Karanas, the Angaharas and the Recakas.

As mentioned; the first four chapters contain material as per the Marga tradition.

In the latter half of the text;

the Chapter Five deals with the Desi varieties of Sthanakas, Uupulika-karanas, Caris and Bhramaris

The Chapter Six describes Desi varieties of Pada-bedha, Caris, Lasyangas and Gati-bedha.

The Chapter Seven discusses general topics related to dance; and, in main, the fifteen Desi-Nrttas, (Nrtta-bedha), including the Perani type of dance. It also discusses the theatre and its types, training methods, various types of artists involved in the production and presentation of Dance etc.

The last Chapter Eight describes the general aspects of presenting dance; and, the administration of the theater.

The Chapters Five to Eight are devoted to Desi Nrtta, in the light of the then current practices.

Brief Summary of the Contents of the Nrtta-ratnavali – Chapter-wise

As regards the Chapter-wise details:

1.The First Chapter (74 verses) of Nrtta-ratnavali begins with the customary benediction, praising dance as an Art-form par excellence, and, defining Nrtta, Nrtya and Natya. And, it also explains the four modes of Abhinaya, i.e., Angika, Vacika, Aharya and Sattvika; and, describing , in detail , the six forms of Dancing- Nrtta, Nrtya, Marga, Desi, Tandava and Lasya .

Jaya Sena explains, the verbal root ‘Nata’ represents the pulsations that occur when the innermost feelings of a being are stirred, awakened and move up (Uccara) towards awareness

Spandana artha taya dhootornateh Satvika puritam ; Rasa-ashrayam ca jneyam vakhyarta abhinayam atmakam –Nr.Rv.1.26

As regards Abhinaya, Jaya Sena says, when the prefix ‘Abhi’ is added to the verbal root ’ni’; and, when it ends in ‘an’, the term Abhinaya is formed. Its purpose is to bring forth and to express thoughts and emotions, as also to indicate objects. Abhinaya, he explains, is the act of experiencing a feeling and expressing its meaning variously , with clarity, through the postures, gestures and movements of the parts of the body , the major and minor limbs (Shakha, Anga and Upangas).

Shakha, Angair Upangai ca prayogena vibhavayan, artan bahau vidhan prapyena va Abhinaya mathah –Nr.Rv.1.28

Jaya Sena defines Nrtta as the movements of the limbs (Anga-vikshepam), in harmony with the rhythm (Laya), the music of the instruments and the song. It is pure Dance, devoid of Abhinaya etc.

Gita-vadyadi militam, laya-matra samashrayam, Anga-vikshepam Nrttam, Bhaved –Abhinayojjitam –Nr.rv.1.53

And, Nrtta and Nrtya, he says, are of two kinds each: Lasya, the delicate (sukumaram) and graceful; and, Tandava the vigorous (uaddatam).

Lasyam- Tandava bhedena dvaya metat dvidha punaha, sukumaram, tayo -radhyam bhaved para uaddatam-Nr.rv.1.56

The mutual attraction and love between man and woman, he says, is Laasa. And, that which is meant to express such Laasa is Lasya. The Lasya comprises those delicate and graceful movements of the body, which arouse a pleasant euphoric feeling (manasija ullasa) and erotic desire. The Lasya is to be performed only be women.

Bhavah Stri-Pumsayor Laasam, tad artam tatra sadhu va Lasyam manasija ullasa hetu mrudvanga horavat Devyai Devo upadistatvat prayaha Stribhi prayujyate –Nr.rv.1.57

Then, Jaya Sena enumerates ten forms of Lasyanga (Lasyangani):

-

- Geyapada;

- Sthitapāṭhya;

- Āsīna;

- Puṣpagaṇḍikā;

- Pracchedaka;

- Trimūḍhaka;

- Saindhavaka;

- Dvimūḍhaka,

- Uttamottamaka; and

- Uktapratyukta (Nr.rv.1.58-59)

These ten Lasyangas, of Marga Class, mentioned by Jaya Senani are the same as in Natyashastra – Lāsye daśa-vidhaṃ hyetad-aṅganirdeśa-lakṣaṇam.

Geyapadam, Sthitapāṭhyam, Asīnaṃ Puṣpagaṇḍikā। Pracchedakaṃ Trimūḍhaṃ ca Saindhavākhyaṃ Dvimūḍhakam ॥119॥ Uttamottamakaṃ caivam Uktapratyuktam eva ca ॥ NS.19. 120॥

[The Lasyangas, according to Jaya Sena, are the elements of the traditional forms of Dance (Marga). In the first part of his work, Jaya Sena presents the Lasyanga as per Bharata, whose emphasis was on the dramatic nature of Lasya. In the Second half of the work, Jaya Sena deals with the Desi –Lasya, the regional variations of the Lasya. He lists as many as forty-six (on page 17) such Desi-Lasyas, which are entirely rooted in Angika movements, with very little of speech element, the Vacika.]

Jaya Sena remarks; some authorities include two more types of Lasyangas – Vicitrapada and Bhavika – but, he would not accept them; and, would adhere to the ten, as enumerated by Bharata Muni – Angani Dasa caiveti Munina yat prakirthitam (Nr.rv.1.72).

1 . Geyapada : The Lasya opens with Geyapada; and, it is accompanied by instrumental music; and, by the singing of the Sushka Aksharas, the rhythmic syllables (Svaras) by the musicians. Then the heroine enters, in dance-like movements; takes her seat; and, sings a song praising the virtues and merits of her Lover.

2. Sthitapāṭhya: The love-stricken Nati or heroine (still seated) renders a song composed in a Prakrit language, pining for her lover; and, pouring out her pain and pangs of separation.

3. Āsīna : The heroine continues to sit in a depressed mood, ruminating over her forlorn condition. She expresses her sorrow and misery through her doleful eyes and facial expressions.

4. Puṣpagaṇḍikā: The sad looking heroine enters the further phase of her love-pangs; and, with her friends by her side, she imitates her Lover, his gestures and his speech. And, the Nati-Nayika, assuming the role of a man dances and sings a song, as her Lover would do.

5. Pracchedaka: This stage depicts the overpowering influence of moonlit-nights over the beloveds. They, still separated, forget and forgive each other’s mistakes; and, long to be together again.

6. Trimūḍhaka: This is similar to the fourth stage of Lasyanga. Here, the pains of separation experienced by the Lover (male) is conveyed through a song composed in Sanskrit, in which the metre is even, employing words that are neither harsh nor severe; but , is natural. The accompanying Dance too is gentle.

7. Saindhavaka: Here, the heroine is depicted as of a Vipra-labdha, waiting for her Lover who fails to turn up on time at the place of tryst. She is sad, disappointed and restless; and, she sings a plaintive song in Prakrit of the Sindhu region (Saindhavi), arousing pity. Her dance follows her mood.

8. Dvimūḍhaka: This is a happier dance, celebrating the heroine’s joy. In her Abhinaya, there is a clear portrayal of her Bhava and Rasa. She , in her playful exuberance, makes pretentious gestures, dances delightfully; turning and swinging merrily in circular movements. The accompanying melodious vocal and instrumental music reflect her happiness.

9. Uttamottamaka: This takes the heroine through a more joyous mood. She celebrates her Love through playful, seemingly mischievous and cheerful movements. The songs she sings are composed in verses of striking beauty. And, the instrumental music is lively and uplifting.

10. Uktapratyukta: The two lovers finally meet and come face-to-face. The Lady-Love, in mock anger, blames the erring Lover for the misery he caused her; and, brisk words are exchanged (Uktapratyukta). After due explanations, the two beloveds forgive each other; assert their Love for each other; and, promise never to be apart. The songs depict the moods and the theme of their exchanges. Then, the heroine dances around her Hero, sublimely.

[ Jaya Sena, in the latter part of the text, lists forty-six Desi- Lasyangas.]

2.The Chapter Two (437 verses) , which is the longest , having the most number of verses, deals with Angika Abhinaya, the movements of body-parts, which are most relevant to dance. Jaya Sena describes, in detail, the movements of the major and minor limbs – Angikani – (Anga, Pratyanga and Upanga).

He mentions six Angas (head, hands, chest, waist and feet)

– Shiro, hastha, Purah, Parshva, Kati, Padau, sat-kramath (Nr.rv.2.1)

The six Pratyangas listed are: the neck, shoulders, stomach, spine, thighs and shanks

– Griva, Bhuja, Kushiro, Prusta, Uru, Jamha, Prtyangani sat ( Nr.rv.2.2)

And, the six Upangas are: the eyes, eyebrows, nose, lips cheeks, and chin-

– –Vilocana, Bhru, Nasika, Oustya, Kapola, Chabukani, sat Upangani (Nr.rv. 2.2.)

*

Then he goes on to describe

: – thirteen types of head – movements (Shiro-lakshanam- verses 3 to 29);

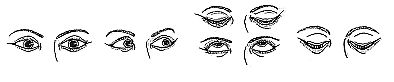

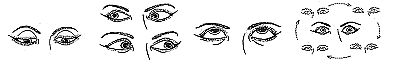

:- thirty-six type of eye movements or glances (Dristi-lakshanam) ; of which eight types of glances are based in eight Rasas (Rasa-dristi); eight glances expressing Sthayi-Bhavas (Sthayi-dristi) ; and those expressing the Sancari-Bhavas being twenty – (verses 30 to 72 )

: – Jaya Sena also describes the applications or uses of the glances enumerated by him (Dristinam Viniyogah) – (Verses 73 to 83)

: – Thereafter he moves on to describe nine kinds of the movements of the eyeballs (Tara karma) and its uses (Tara karma Viniyogah) – (verses 84 to 91)

: – Next, eight types of eye-expressions (Darsha Prakara) are described (Verses 92 to 96)

: – The nine types of the movements of the eyelids (Puta Karma) are described next (Verses 97 to 104)

: – The seven types of the movements of the eyebrows (Bru-karma) are described next – (verses 105 to 115)

: – Thereafter, Jaya Sena moves on to Nasika -lakshanam, the six types of movements of the nose (Nasa-karma) – (Verses 116 to 122)

: -The movements of the lips (Oustya or Adhara-lakshanam) are six – (verses 123 to 131)

: – The movements of the cheeks (Kapola-lakshanam) are also six – (Verses 131 to135)

: – The movements of the chin (Chibuka-lakshanam) are seven; these are coordinated with those of the tongue, teeth, lips. These are mentioned as Hanu-lakshanam, Jihva-lakshanam, and Danta-kama (Verses 136 to 151)

: – The movements of the neck (Griva-lakshanam) are of nine types – (verses 152 to 157)

: And, the facial colors (Mukha-ragam) are three- (Verses 158 to 163)

Hastha –lakshanam

Jaya Sena deals with the gestures and movements of hands (Hastha-lakshanani) in fair detail. Here again, he, generally, follows the enumerations and the descriptions as provided in the Natyashastra. He also explains why he is adhering to the enumerations made by Bharata Muni; and, is not accepting the changes and modifications made by Someshvara and other commentators.

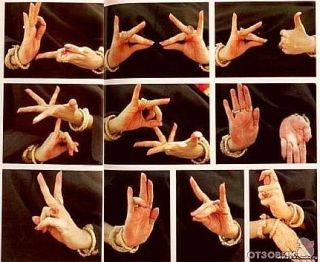

Jaya Sena describes 14 types of the movements of the single hand (Asamyukta-hasta) – (Verses 165-167); 13 types of the movements generated by the combination of both the hands (Samyukta-hastha) – (Verses 168-169); and, 29 types of the Nrtta hastha- (Verses 170 to 175) . Thus, the Hasthas, in all, add up to sixty-six representations.

Jaya Sena describes each of the elements of the Asamyukta-hasta (Verses-187-263); the Samyukta-hastha (Verses-264-286); and, the Nrtta-hastha (Verses-26-375), along with their Viniyogas (applications). During the course of presenting his explanations, Jaya Sena quotes the views of other authors, such as Abhinavagupta, Klrtidhara and others.

At the commencement of the discussion on the Hastha-lakshanam, Jaya Sena makes a very interesting observation. He compares the movements and gestures of the hands and fingers to a vast ocean. He says, the subject is very vast; and is indeed, endless. Just as the ocean contains in itself, varieties of animals, creatures, vegetation etc., the Hasthas have varied and almost countless varieties of expressions.

Vast is indeed the subject of the gestures of the hands, just as the ocean. The waters of the ocean, in their depth, house the wily animals like crocodiles; on its surface are the lovely flowers like lotuses; and, over its surface fly the swarm of bees in graceful abandon. The waters are dotted and decorated by the beautiful wings of the swans; and, by the dancing petals of the lotus. The ocean, of course, is also the home of creatures like crabs etc.

Chatura Makaradi prollasat-padma-kosam, Bhramara-Lalita-Lilam, Hamsa paksha-abhiramam, pravicalad-alapadmam, karkata-dirupetam , jaladi jalami vedam, brumahe hastha-lakshanam (Nr.rv.2.164)

The terms that are cleverly used by Jaya Sena in this verse, also stand for the various types of hand-gestures (Hastha-bedha): Chatura; Macara; Padma-kosa; Bhramara; Lalitha; Hamsa-paksha; Ala-padma; and Karkata. He has woven these terms, ingeniously, into the descriptive verse.

Referring to the limitless potential of the hand-gestures (Hasthanam ananthathvam) to express various suggestions, thoughts, emotions and objects; Jaya Sena remarks: the whole universe can be expressed through these gestures. Their ways are truly endless. There are might be many Hasthas that are applicable in a particular context; but, there could be several more such. The skill of the performer lies in exploring; and, in choosing from the vast resources, the one that is most appropriate. The use (Viniyoga) of the Hasthas is, indeed, infinite –ananta.

Abhijneyam jagat –sarvam ananto abhinayo pyayam, yo eva yujyate hastho tesam api anantata – Nr.rv. 2.287

Jaya Sena counsels: the truly wise must study deep, exercise their discretion to choose the most suitable Hastha, taking into consideration the context of place, time , performance and its purpose. Its expressions of the Sthayi and Sancari Bhavas must be adequately supported by the suitable meaningful eye- movements.

Desa, Kala, prayogartha vedi, netradi dristi cestitai, anukulai prayanjita sthayi-sancari-suchacaihi – (Nr.rv.2.290)

*

Thereafter, Jaya Sena moves on to describe the movements of the other limbs (Pratyangas), such as the arms, shoulders, stomach, spine, thighs and shanks, with particular attention to the feet movement:

-

- Bahu Prakara (310-325);

- Paksha-lakshanam (376-382);

- Parshva-lakshanam (383-388);

- Jatara-lakshanam (389-390);

- Kati-lakshanam (391-395);

- Uru-lakshanam (396-400);

- Janu-karmani (401-404);

- Jampa-karmani (405-411);

- Pada-lakshanam (412-426); and,

- Padanguli-lakshanam (427- 437 ).

3. The Chapter Three (198 Verses) is mainly about Caris (movements of one leg), Sthanas (postures); Nyaya (stance to be assumed while wielding a weapon in a fight); Vyayama (exercise); Sausthava (physical fitness); and, more Sthanas and Mandalas (combinations of Caris).

Here, Jaya Sena broadly follows the enumerations and definitions as per Bharata; but, makes certain variations.

He describes 16 types of Bhu Caris – both feet in contact with the ground (Verses 14 to 40) and 16 types of Akasha Caris – one foot in the air or a leap (Verses 41 to 69). Jaya Sena remarks, though for the purposes of the text the Caris are counted as 32 in number; its varieties are truly endless.

He also describes ten earthly (Bhu) Mandalas and ten aerial (Akasha) Mandalas.

As regards the Sthanas, standing-postures, Jaya Sena makes a distinction between the Sthanas meant for men (Purusha-Sthana) and those for women (Stri-Sthana). He reckons the following six Sthanas as being suitable for men:

-

- Vaishnava,

- Sampada,

- Vaisakha,

- Mandala,

- Alidha and

- Pratya-alida.

He describes, in fair detail, the Nyayas or the positions and postures to be assumed while fighting and wielding weapons.

4. The Chapter Four (377 Verses) describes Karanas (dance-units) and Angaharas (sequences of dance-units); and, ends with Recakas (extending movements of the neck, the hands, the waist and the feet), mainly, on the lines of the Natyashastra. In general, Jaya Sena’s treatment of the Marga tradition is faithful to Bharata and Abhinavagupta.

The groups of Karanas as listed in the text are :

-

- Valitoru (encircling);

- Aksipta (embrace);

- Kranta (anklet movement);

- Harinapluta (leaping like a deer);

- Bhujanga-ancita (curving-like-a-snake);

- Parsva-kranta (moving sideways);

- Apavidda (entertaining);

- Vrshabha-krida (like a bull); and,

- Urdhva-janu (lifting up the knee).

He then provides various combinations of the Stanakas, Nrtta-hasthas and Caris in order to compose varieties of Karanas. He describes several aspects of Angaharas; and, remarks, that by altering the sequence in the combinations of the Karanas, infinite variations of the Angaharas can be produced.

Here, while commenting on the Angaharas, Jaya Sena observes: Generally, a combination of three or four Karanas could be said to compose an Angahara. But, there is no such strict rule in that regard. Bharata had used the prefix ‘va’ to indicate that there could be more options. A combination of two Karanas is named Matraka; of three as Kalapa; of four as Khanda; and, of five Karanas as Sanghata.

Therefore, the Karanas can be made into sets of six, seven, eight and even nine to form an Angahara. And there is no strict rule; it is left to the imagination and skill of the performer.

5. The Chapter Five (109 Verses) marks the commencement of the Second-half of Nrttaratnavali; and, this latter-half is devoted to discussion on the Desi Nrtta.

The term ‘Desi’ had been in use since the time of Matanga’s Brhad-Desi; and , later it was extensively used by other authors , such as : King Someshvara (Manasollasa) , Srangadeva (Sangita-ratnakara) and Parsvadeva (Sangita-samaya-sara). All these commentators described the various types of Desi dance-postures, movements and Dances.

As mentioned earlier, Jaya Sena in his Nrttaratnavali deals with the Desi Dances and their elements in Four Chapters (from Chapter 5to 8). Here again, he discusses the Desi tradition in two parts: in the First Part (Chapters 5 and 6) he describes the Desi types of Sthanakas, Utpluti-karanas, Bhramaris, Pada, Pata, Cari, Lasyanga and Gati-bhedas as being derivatives or supplements to the Marga -bhedas.

And, in the second Part (particularly the Chapter 7), Jaya Senani focuses on the various types of Desi Dances that were prevalent during the time of his King Ganapati Deva; and, these include Dances forms that were peculiar to the Andhra region (Desi Nrtta) such as : Perini, Rasakam, Carchari, Bahurumpam, Kanduka , Bhandika , Kollatamu , Chindu and Gondali.

Jaya Sena commences the Chapter Five by defining the term ‘Desi’ as that which is innovative, depicting new subjects, in newer forms of Dance movements (Nava Nrttam), that are peculiar to the culture (Desanusara) of each region (Desi); and, that which are devised for the delight of the Kings, who are always interested in newer forms of entertainment; as also for gladdening the hearts of common people of.

Bhavanti Dharanipalah prayena Abhinaya-priyah, atah triptiyedyapi yad utpadyate navam Nrttam tatah smrutam Desi tat Desanusaraha (Nr.rv. 5.3)

He then goes on to describe twenty-three types of Desi Sthanas (Verses 12 to 38); Fourteen types of Utpluti-karanas (Desi Karanas with leaping movements)- (Verses 39- 46) and their thirty-two types of applications (Verses 47 to 81); and, thirteen types of Bhramaris (pirouettes, spins and turns) – (Verses 82 10 109)

6. The Chapter Six (187 Verses) deals with the movements of the feet. These are described here as Desi-Padas, which are also called as Desi Caris by other authors. But, in the tradition of Bharata, the Caris and Padas are treated as being distinct.

Jaya Senani, following Bharata, treats these separately. He has a separate section for dealing with his Desi-Caris, some of which are not found in the earlier texts. Similarly, the descriptions of the Desi-Patamanis are his own.

Here, the Desi Pada implies merely contact of the feet with the ground; and, Desi -Patamani involves stamping or striking the ground with the feet (Pada-tadana); and, Desi-Caris involve movements of one extended leg.

Matanga, in his Brhad-Desi, had described sixteen verities of foot-positions (Sodasa-Desi–Pada-bedhah) that add beauty to the Desi Nrtta. Jaya Sena after describing these Desi-Padas (Verses 1 to 12) extends them to twenty-eight foot-movements – Astavimsati-patah (verses 13 to 53).

Jaya Sena recalls the statement made by Matanga that with some enterprise and imagination, one can devise more number of Desi Padas; and, Jaya Sena avers that he would be following Matanga’s advice. Accordingly, Jaya Sena describes forty-two verities of Desi-Caris, of which twenty-six are Bhumi-Caris (with feet in contact with the ground)- (Verses 63 to 88); and, sixteen are Akashi Caris (with at least one leg in the air) – (Verses 89 to 105).

Jaya Sena, in addition, describes four mixed varieties of Caris (Sankirna-Cari) : Talasarpanika (chain-like movements on foot soles), Hamsarutham (swan-like movements gliding back and forth), Tittiri-gati (simulating butterfly movements perched on toes) and Antarapadmasam (squatting in Padmasana and moving up) (verses 106 to 112).

Then Jaya Sena takes up Desi-Lasyanga, describing its forty-six varieties, following, in main, Srangadeva and Parsvadeva- (Verses 118 to 169).

Jaya Senani defines Lasya and Tandava as the two varieties of Nrtta and Nrtya. The Lasya, he says, is a feminine dance style, which arouses the Srngara Rasa with its delicate and graceful movements. Shiva taught this dance style to his consort Parvati.

In contrast, Tandava, a pure Nrtta with no element of Abhinaya, is a vigorous type of dance, performed in various Talas to invigorating music, in brisk and aggressive movements, exuding Veera and Bhayanaka Rasas. In the Desi Nrtta, Tandava is basically the dance of the warriors performed only by men.

*

The Chapter Six concludes with description of the Gatis (gaits), in slow (vilambita), medium (madhyama) and fast tempos (druta) – (Verses 170 to 187). During the sequence of taking such steps, the pace of gaits could vary from slow to fast or medium etc., or the other way; it would then be a Sankirna-Gati. Jaya Sena also indicates the Talas (the time units) that are appropriate for the Gatis of each tempo (Kala). For instance; if the performer takes two, three or more steps within a Time-unit (Tala), then that could be called Druta-Gati (Verse 172).

7. The Seventh Chapter discusses varied subjects such as : auspicious dates for beginning dance lessons (the term that Jaya Sena uses here is Nrtya); the characteristics of the stage and some general discussion on presentation; the time and location of dance performances; the worship of Ganesha; the methods of training and practice; the qualifications desirable in a dancer; the dance costume; the hand-gestures for practice; and, the accompanying vocal and instrumental music. The Chapter then focuses its attention on describing individual dance pieces, calling them Desi Nrtta.

*

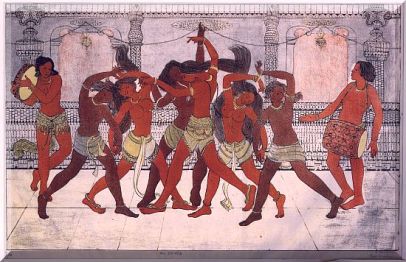

There is an elaborate description of Perani. It is said; the term Perani was derived from ‘Prerana’ meaning inspiration. And, Perani is one who is inspired by Lord Shiva; or a dance form that invokes (Prerana) and is dedicated to the Supreme Dancer Shiva.

The text carries an elaborate description of Perani, lauding him in choosiest words of praise and attributing to him all the noble virtues.

A Perani , a dancer, is one who is capable of taking the spectators to the heights of aesthetic delight; an attractive person of great reputation; descending from commendable linage; a sentient connoisseur; and adept in rhythm; expert in music; master of several instruments; devoid of aberrations; learned in several, branches of knowledge ; proficient in many languages; a dancer of great quality, who is well versed in both the Lasya and Tandava Dance forms; one who can execute the Karanas involving leaps , turns and spins; and, an adept in all the Dance techniques.( Nr.rv. 7. 34 to 37)

The text mentions; the Prerana dance has five aspects: Nrttam; Kaivaram; Ghargaram; Vikatam; and, Geetam.

Prerar-angani panchasya Nrtta, kaivarah, Vikatam, Geetam ityesham karma laksham pracakshapa (Nr.rv.7.43)

It is said; while performing such types of Dances the Perani Dancer should invariably be adorned with belled-anklets tightly around the shanks (Kinkini-bandha)

It is believed that this dance form invokes ‘Prerana‘ (inspiration) and is dedicated to supreme dancer Shiva.

Jaya Sena describes the five parts of the Prerana Dance. And says :

: – The Nrtta is that which has both the aspects of Lasya and Tandava- tan Nrttam yat dvidataktam Lasya Tandava bhedah (Verse 44).

:- The Kaivara is the dance which adulates and celebrates the virtues and valour of the Great kings of the past; and, through the metaphors used for such a great person , the King who is on the throne is lavishly praised (Verse 45).

:- The Gharghara is that war-dance which is enthused by vigorous and rousing beats of the thundering Gargara war-drums; dancing furiously, employing six of the ten Pada-bhedas (other than Parsva, Gattitama, Suci and Anguliprusta) – (Verse 55).

:- The Vikata is the grotesque dance where the dancers wearing the ghastly make up and costumes of the demons and ghouls (Pisaca), covering their faces with masks of ugly faces, frightening eyes and repelling lips ; even turning their shoulders, stomachs and legs into ghastly proportions (Vikruta) , scream , shout most annoyingly ; and, jump, twist, turn in ugly ways. Some call this Dance as Vagada. (Verses 56 and 57)

: – And, Geetam is that where the performers dance to the melodious and tuneful singing of the songs from the traditional Shuddha Chayalaga Prabandha Music format. (Verse 58).

**

The Perani Paddati the ways of performing the Perani Dance are described in Verses 59 to 68. Here, Jaya Sena specifies the types of music, songs and instruments, as also the stage preparations suitable for performing all the five aspects of the Prerana Dances, in their sequence.

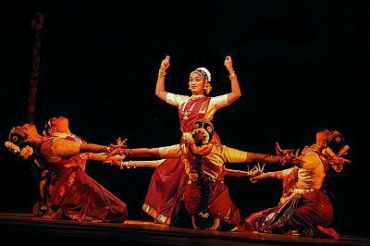

[The Perini Tandava is a vigorous Nrtta, usually, performed by warriors (Veerulu) before they leave for to the battlefield. It is therefore called ‘Dance of Warriors’. The Perini Tandava, done to the resounding beats of drums, is indeed believed to be the most invigorating and intoxicating male dance form. While dancing, the warrior invokes Shiva to come into him ; and, to dance through him. Dancers drive themselves to a state of frenzy, where they feel the power of Siva in their body.

The dance form, Perini, reached its pinnacle during the rule of the Kakatiya Kings, who established their dynasty at Warangal and ruled for almost two centuries. The Perini dance form almost disappeared after the decline of the Kakatiya dynasty.]

Jaya Sena outlines the Desi Paddathi of presenting a Dance performance.

The performance begins with the auspicious instrumental music; that is followed by Yati-Praharana; and Pushpajali is performed without song or musical accompaniment. Then follow the Jhenkara; Rigavani; Tundaka; and, Camatkara.

Thereafter come the Geetanga, the orchestral music, the auspicious songs and finally the Praharana- (Verses 69-70) . Further details are provided in Verses 71 to 77.

[Pardon me; I am not very clear about some of the terms used here to indicate the ingredients of the Desi-Paddathi.]

*

Jaya Sena, following the explanations provided by Matanga for classifying the Prabandhas, says that Nartana can also be classified into two classes: Shuddha Suda and Salaga Suda.

According to Jaya Sena, Nartana that follow the Shudda Suda type of Prabandha has nine forms (Verses 80 and 81) :

-

- Ela;

- Karana;

- Varnasara;

- Kaivara;

- Jhombada;

- Tribanghi;

- Vartani,

- Rasaka; and

- Ekatali.

And, the Salaga Suda has seven types: Dhruva, Mantha, Prati-mantha, Nihsaru, Addatala, Rasaka and Ekatali. (Verse 88)

The following twelve types of Desi Nrttas are described in the Nrttaratnavali:

-

- 1. Rasakam;

- 2. Carcari;

- 3. Natya-Rasaka;

- 4. Danda-Rasaka;

- 5. Sivapriyam;

- 6. Cinthu-Nrtta;

- 7. Kanduka-Nrtta;

- 8. Bhandika-Nrtta;

- 9. Ghatisani-Nrtta;

- 10. Carana-Nrtta;

- 11. Bahurupa-Nrtta; and,

- 12. Kollata- Nartana.

Rasaka

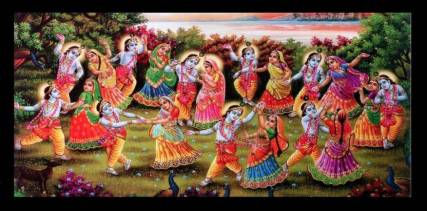

Jaya Sena, then, takes up the description of the Rasaka, which is a Pindibandha class of Group Dances. The Pindibandhas, or group dances, a form Nrtta, are performed by six, eight, twelve or more pairs of men and women. The Pindibandhas are classified into four types: Pindi (Gulma-lump-like formation); Latha (entwined like creeper or net like formation, where dancers put their arms around each other); Srinkhalika (chain like formation by holding each other’s hands); and, Bhedyaka (where the dancers occasionally break away from the group and perform individual numbers).

Of these four types of Pindibandhas, the Rasaka is treated as a Pindibandha of the Latha variety of Lasya, which is related to Srngara-rasa, portraying love and other softer, graceful aspects.

Jaya Sena describes the Rasaka type of Desi Nrtta in Verses 84 to 99.

According to Jaya Senapati, Rasaka is to be performed by experienced, young, dancers in pairs of 8,12 or 16 , dressed appropriately, exhibiting various Caris , entering from either sides of the stage , in tune with the musical instruments, the Sangita Vadya. He describes the beauty, youth and alluring qualities of the dancers; and, their flashing movements, comparing them to lightning.

Carcari

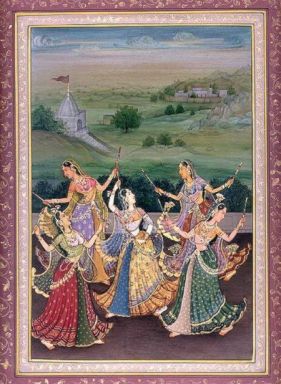

Carcari is described as a springtime-dance performed by a group of female dancers, celebrating the Vasantotsava festival, singing sweet songs in Raga Vasantha; weaving various patterns and designs as they dance; clapping hands; snapping the fingers or striking each other’s palms while they dance around in circles; and form manifold patterns while performing Khanda, mandala, Cari etc., as in the Pindibandhas. Carcari is a kind of ensemble dance, resembling the Rasa-Lila of the Gopis.

Carcari is a jubilant Dance, a festive sport of merriment , singing songs of Srngara Rasa, where the cheerful women, as they dance, move around in circles, and sing praise the virtues of the Nayaka , the presiding King (Verses 98 and 99) .

It is said; the Carcari Prabandha is known as Jajara in some Telugu texts. And, Raja Bhoja, in his Srngara Prakasa, uses the term Carcari as an alternate name for Natya-Rasaka.

Natya-Rasaka

Jaya Sena explains Natya-Rasaka as a Dance performed in the spring season (Vasantha) by the women of the Court singing Desi Songs in Hindola Raga, praising the virtues and merits of the King ; and, interpreting the words of the song through Abhinaya (Padartha-abhinaya)- (Verse 100)

*

Danda Rasaka

The Danda-Rasaka is Nrtta, a Pindibandha or group dance performed by eight or more pairs of men women, playing with coloured sticks. There is much singing and dancing in rhythmic steps; but, not much speech and Abhinaya. It is similar to the Rasaka. This type is also known as the Krida-Rasaka of the Gopis, where the Gopis play the Rasa with Sri Krishna.

Jaya Sena explains the Danda Rasaka as a form of group performance during spring season. It is performed by even number of pair of dancers, usually in multiples of 4 to 24, with sticks held in both the hands. In some variations, fly-whisks, daggers are held by the dancers in one hand and sticks in the other.

The instrumentalists play melodious music to which dancers perform choreographic patterns including Lasyangas, Brahmaris, Caris and Utplavanas (leaps), in circling movements, to the accompaniment of rhythmic striking of sticks. Khandas or dance segments must be continued along with elegant leaps to the left and right hand sides as well as executing the circular movements. Specific strokes of the sticks must create the required beats.

Regarding the mode of the entry of the dancers, Jaya Sena said: Eight of them may enter first, gradually by addition of batches of four, the number may go up to sixty-four, forming two rows.

Jaya Sena says that the songs are composed in praise of the King’s virtues. Dances are to be performed by experienced dancers. (Verses 101 to 107)

Shiva Priya

Shiva Priya, is again, a group dance performed by men and women to the accompaniment of the beats of the various types of drums, cymbals, trumpets (Kahala). The participating men and women each holds in his/her left hand a replica of a snake made of brass or copper; and, a sword in the right hand. They all rhythmically make sounds ‘Kirikiti’.

They all wear garlands made of Rudraksha beads; three stripe of Vibuthi across their forehead (Tripundra); and, reverently sing songs in praise of Shiva (Shiva stuti).

The Shiva Priya dance consists in the performers dancing in rhythmic steps, displaying Lasyanga, singing songs ; and, sometimes facing each other in rows of two ; and, then breaking to form circles in various patterns . This Dance is said to be particularly dear to Shiva (Shiva Priya) – (Verses 108 t0 118)

*

Cintu Nrtta

According to Jaya Sena, Chitu is a type of Desi Nrtta that originated in the Dravida Desa; and, it (Cindu) is very dear to the people of Tamil Nadu. Groups of well dressed young women dance swaying their arms and bodies, rhythmically, to the accompaniment of instrumental music. As they clap their hands and dance in playful steps, displaying the Padas, Caris and Gatis of Lasyanga, they sing songs composed in Dvipadi. The dancers interpret the meaning of the words of the song with predominance of Lasyanga, through Pada-artha-abhinaya.

**

Kanduka-Nrtta

Kanduka is a peculiar kind of a Desi Nrtta and a ball-game as well, played by wide-eyed, young and beautiful women, in the prime of their youth, in a jubilant mood (Vibhrama). As these playful and joyous lovely women play and dance, the songs selected from the Prabahdhas relating to the Desi Nrtta; or the songs meant for the depiction of Bhandas (patterns) such as: Padma, Gomurtica, Naga, and Chakra, are sung and played on musical instruments.

The ball, these women play with, is made either of gold, silver or brass; and, is hallow inside. The ball holds within it number of beads, which rattle and make sounds, as the dancing women jump in the air, run around throwing and catching the ball.

As these beautiful women with mischievous flickering eyes, jump in the air, and, perform various types of Caris, Gatis, Padas of Lasyanga, while they create patterns resembling fish, lotus filled ponds etc. (Verses 118 to 125)

**

Bhandika Nrtta

The Bhandika Nrtta is comical dance performed by clowns. As they dance around in irregular and difficult steps , mimicking Adavus, the instrumentalists pretend as though they are playing the pipe or beating the drums. The dancing jesters create their own rhythms by clap of hands; and imitate the movements of hunchbacks, dwarfs and the maimed and , they also make varieties of sounds of birds and animals such as : peacock, parrot, monkey, donkey, dog, camel etc.

While making the sounds of each bird or animal they imitate its movements in exaggerated, funny and mischievous manners. These hilarious dances blow away the sorrows and anxieties of the spectators; and, make them laugh till their sides ache. (Verses 126to 129)

*

Ghatisani-Nrtta

The Ghatisani-Nrtta is a dance that is oriented towards rendering a song with action, in the company of her friends. Here, a beautiful Candala women, dressed in light and modest costume; and, gifted with melodious voice and clear diction; sings songs, while playing on the Panduka Vadya (a kind of hand-held musical instrument). The songs she sings are variously selected from the Desi Suda Prabandha and Carya-Prandha, describing the playful actions of Shiva in his Kirata (hunter) aspect, holding bow and arrows.

As she sings and dances along with other male and female dancers, to accompaniment of the sounds of the drums , cymbals , trumpets (Kahala) and Karata Vadya (?); and to the rendering of Tala-Prabandha, Yati, Praharana etc., she moves along delightfully, in delicate (Sukumara) dance-steps, spreading cheer and happiness. (Jaya Sena mentions that even a male who is endowed with the requisite virtues can perform Ghatisani-Nrtta.)- (Verses 130 to 134)

*

Carana-Nrtta

According to Jaya Sena, the Carana-Nrtta is the dance of the professional nomadic dancers and singers who come from the Saurastra region in the Western India. They travel (Carana) from place to place displaying their artistry. Their songs composed in Dohas (couplets) or Dohaka, derived from Dohaka metre, laden with Rasas, set to attractive beats, are sung in melodious Ragas, with playful Desi-Kakus (intonations). They sing along merrily, clapping their hands, twisting, spinning (Bhramari) and tumbling somersaults (laghava); moving in swift but not with very aggressive (Lalita-uddhata) footwork (Pada-vinyasa) ; they , in between, shout in booming voice ‘Bhi- Bhoo’ imitating the sound of instruments. Jaya Sena observes, the Carana women-dancers cover their heads with a part of the sari they are wearing (Pallu). – (Verses 135-138)

Bahurupa Nrtta

The Bahurupa Nrtta is the display of varied forms of dresses, behaviors, speech etc., of persons coming from different regions and cultural groups.

Describing the qualities of a competent Bahurupa Nrtta performer, Jaya Sena mentions that such a dancer must be: young, agile, learned, clever, witty, fluent in his expressions, proficient in Sanskrit and regional languages; and, should induce happiness. In addition, such a Bahurupi should be a well trained, experienced dancer having a pleasant voice; he should be quick in changing the costumes and make up; he should, preferably have shaved off the beard and the hair on his head. A woman endowed with these qualities can also perform as a Bahurupi.

As regards the performance of the Bahurupi, Jaya Sena mentions, the dancer should adopt the Natyadharmi mode of presentation. And, in his versatility , he should be able to credibly represent the two-footed , the four-footed and even the feet-less living beings . He should, following the instrumental music and the songs, dance according to the situation. And, in between, he should also sing. More importantly, he should never cross the limits of decency. A Bahurupi would do well to enact the roles of a King or of a renowned person in the history. (Verses 145 to 148)

*

Kollata- Nartana

The Kollata – Nartana that Jaya Sena describes is , in fact, the dance of the acrobats who perform at the street corners. They are also called ‘Dombigas’ or ‘Domburu’.

Initially the acrobats perform Desi Caris, Karanas and other dance movements. And, then, as the drums, cymbals, bells, blow-horns (Bheri) play vigorously; and with the spectators clapping and cheering loudly, the tempo of the Dance increases. Thereafter, the acrobat climbs on the tripod supporting the leather strap or the rope that stretches across. He then begins to walk along the rope in careful steps. And, while on the rope he does dance movements with a remarkable sense of balance. Then, after reaching the other end of the rope , standing on the tripod, he executes dexterous and risky Bhramaris (Turns), wielding dangerous weapons like swords.

Then, after jumping down from the rope, the Kollatiga, dances around carrying incredibly heavy objects, twirling swords etc. The acrobat performs many types of skillful, swift and attractive dances; leaping, spinning, twisting, turning, tumbling, cart-wheeling etc.- (verses 149-152)

**

Thereafter, Jaya Sena concludes the Chapter Seven by describing in great detail the qualities of the female dancer (Nartaki), the male dancer (Nartaka) , the main singer (Mukhya-gayaka),the instrumentalist who plays the pipe (Mukhari) , the orchestra (Vadya-brunda) ; and the stage-manager (Sabhapati) . He also describes the theater (Nrtta-mandala)- (Verses 153 to 288)

8. The Eighth and the Final chapter (84 verses) is the shortest. And, in general, it provides more information regarding presentation; the age, the required qualities as also the physical and emotional requirements of the girl to learn dance; the ritual to be performed before beginning the training; the state of mind, auspicious time, place of practice, costume for practice (in accordance with the physique); how to focus and get into the right mood to execute perfect Abhinaya; the recital; the appropriate time for its presentation; the arrival of the chief guest ; and, the welcome to be accorded to the king and other important members of the audience; the orchestra; the seating arrangements; the entrance of a dancer; the use of three curtains on the stage and their removal etc.

The chapter also talks about honoring the dancer, the musicians and the poet

Gejjala Mantapam – (Dance pavilion for public)

Jaya Senapati remarks that the spectators are very much a part of the Art-experience; and, even a very good performance would be of no avail unless the spectators are cultured, refined and truly capable of appreciating and enjoying the presentation.

Jaya Sena concludes his work with the Verse, which says: This garland named as Nrttaratnavali was knitted by Jaya Senadi-natha, with the aid of Nrtta-angas composed of Sucimukha, Gati, Guna and Shikhara.

Here, he was playing on the words, by comparing the Nrttaratnavali to a garland ; and the various elements of Nrttanga to sharp needle (Suci), thread(Gati); knitting (Guna) and the successful completion (Shikara).

Sucimukha, Gatisuchya, Guna, Shikara-shobini, Jaya-Senadi-nathena Nrttaratnavali krtah (Verse 81)

Eti Sriman Maharajadhi Raja Ganapathi Deva Gaja-sadhanica Jaya Senapati virachitam Nrtta-ratnavali Sampurnam

In the Next Part, we shall move on to another text.

Continued

In

The Next Part

References and Sources

- Nrttaratnavali (Translated into Telugu) by Prof. Rallapalli Ananata Sharma – published by Andhra Pradesh Sangita Nataka Academy –1969

- Movement and Mimesis: The Idea of Dance in the Sanskritic Tradition by Dr Mandakranta Bose

- http://www.andhraportal.org/literature-nrtta-ratnavali/

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/25592/9/09_chapter%201.pdf

- Bharatanatya: a paper presented by Dr.V Raghavan at the Dance Seminar held Sangita Natak Academy

- All PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET

As a part of her preparation, the dancer should offer her respects to the well-shaped dainty (Surupa) little (Sukshma) ankle-bells (Kinkini) made of bronze (Kamsya-racita), giving pleasant sounds (Susvara), with insignia of the presiding star-deities (Nakshatra-devata), and tied together with an indigo string (Nila-sutrena). Before wearing the anklet-bells, the dancer should reverently touch her forehead and eyes with them; and repeat a brief prayer (AD.

As a part of her preparation, the dancer should offer her respects to the well-shaped dainty (Surupa) little (Sukshma) ankle-bells (Kinkini) made of bronze (Kamsya-racita), giving pleasant sounds (Susvara), with insignia of the presiding star-deities (Nakshatra-devata), and tied together with an indigo string (Nila-sutrena). Before wearing the anklet-bells, the dancer should reverently touch her forehead and eyes with them; and repeat a brief prayer (AD.

Abhinavagupta, in his typical style, provides a totally different sort of explanation to the term Tandava. According to him, the term Tāṇḍava is derived from the sounds like ‘Tando; tam-tam’, produced by the accompanying Damaru shaped drums. It follows the manner, in Grammar (vyākaraṇa), of naming an object, based on the sound it produces – śabda-anukṛti.

Abhinavagupta, in his typical style, provides a totally different sort of explanation to the term Tandava. According to him, the term Tāṇḍava is derived from the sounds like ‘Tando; tam-tam’, produced by the accompanying Damaru shaped drums. It follows the manner, in Grammar (vyākaraṇa), of naming an object, based on the sound it produces – śabda-anukṛti.