Sri Shyama Shastry – Music-Continued

STRUCTURE

Kriti, which is the most highly evolved form of musical composition in Karnataka Samgita, is a descendant of Prabandha, a Musical format, which was in vogue for about a thousand years, till the Seventeenth Century.

To put it briefly, without much discussion:

Prabandha

The Prabhandha is a well structured (Prabhadyate iti Prabandhah), strictly regulated (Nibaddha) Samgita, which is made up of Six Angas (shadbhir-angaisca) and Four Dhatus (chaturbhi-dhaturbh-ischayah).

The Six Anga-s or elements of a musical Prabandha-s are: Pada; Svara; Taala; Paata; Tenaka, ; and Birudu.

And, the four Dhatus are: Udgraha, Melapaka, Dhruva and Abhoga.- The term Dhatu, in this context, stands for an element or a section or sections of a Prabandha composition

– Chaturbhir-dhatubhih shadbhishcha-angairyah syat prarbandhate tasmat prabandhah

*

[Here in this definition, the Six Angas (elements) were:

Pada (passage of meaningful words);

Svara (notes or sol-fa passage);

Taala (musical meter or the cyclic time units;

Paata (vocalized drum syllables or beats of the percussion and other musical instruments);

Tenaka (vocal syllables, meaningless and musical in sound with many repetitions of the syllables like Te and Tna conveying a sense of auspiciousness (mangala-artha-prakashaka); And,

Birudu (words of praise, extolling the subject of the song and also including the name of the singer or the patron) ]

*

Of the six Angas, it was said : Tena and Pada, reflecting auspiciousness and meaning respectively are its two eyes; Paata and Birudu are the two hands, because they are produced by the hands, the cause (Kaarana) being figuratively taken for effect (Kriya) ; Taala and Svara are like the two feet as they cause the movement of the Prabandha-purusha.

*

As regards the Dhatus :

The Kalyana Chalukya King Somesvara III (1127-1139 AD) in his Manasollasa explains the four Dhatu-s :

: – Udgraha is the commencing section of the song. Here the song is first grasped (udgrahyate), hence the name Udgraha.

Udgraha is said to consist a pair of rhymed lines, followed by an ornamental passage; and, then by a passage of text describing the subject of the song. Thus there should be pair of lines in the Udgraha and in the third section as well.

: – Melapaka is the bridge, the link that unites the Udgraha and Dhruva.

The Melapaka should be rendered adorned with ornamentation (Alamkara).

: – Dhruva is the main body of the song; and, is that which is repeated. Dhruva is so called because it is rendered again and again (refrain); and, because it is obligatory or constant (dhruvatvat). [It is also said ’the Dhruva is in the Udgraha itself – Udgraha eva yatra-syad Dhruvah]; and,

: –Abhoga is the conclusion of the song. Abhoga gets its name because it completes (Abhoga) the Dhruva. It should mention the name of the singer.

And, once the Abhoga has been sung, Dhruva should be repeated.

**

A Prabandha was categorized (Prabandha-Jaati) depending on the number and type of Dhatus (sections) that constituted its structure: Dvi-dhatu (Udgraha and Dhruva); Tri-dhatu (Udgraha, Dhruva and Abogha); and, Chatur-dhatu (Udgraha, Melapaka, Dhruva and Abogha).

*

Among the four Dhatus, the two – Udgraha and Dhruva – are essential and indispensable. And the other two, Melapaka and Abhoga are optional.

;-The rendering of the Prabandha composition of the type Medini Jaati Prabandha (having all the Six Angas); and, having four Dhatus (Chatur-dhatu) would commence with Udgraha (that which is grasped- Udgrahyate).

Here, each Dhatu (section) is set in a different Raga and Taala.

The opening Udgraha will begin with a couplet set to mater (Chhandas), in meaningful words (Pada- pada prayoga) setting out the main theme of the song and continuing with elaboration of the melodic syllables (Svaras).

:-Then, in the interlude, which functions as the bridge (Melapaka), one may or may not have passages of Tena.

:-Then comes the main section Dhruva set in meaningful words (pada) and meter (Chhandas) with appropriate Taala cycles. Here, the rhythmic element of the song gets more intense. Then, one could have an optional section (Antara) perhaps with rapidly recited Paata syllables – before coming to the concluding section.

:-For the concluding section (Abogha), the Anga-Birudu is required as the signature (Mudra) of the composer or singer or as a dedication to the patron. The performance could conclude with repletion (refrain) of main lines from Dhruva.

*

During the Seventeenth Century, the Golden period of Karnataka Samgita, the Prabandha format was revised and recast, paving way for the introduction of a more elegant form of musical composition – the Kriti.

Certain changes were effected, in regard to the Angas and to the Dhatus as well.

*

As regards the Angas, the basic components; Pada, Svara and Taala were retained, almost as they were in the Prabandhas. But, certain changes were brought in with regard to the status of the other three Angas: Paata; Tenaka; and Birudu.

Paata:

Paata, the percussion syllables (Paata),which was once a characteristic feature of the Bandha–karana of the ancient Shuddha-Suda–Prabandhas, led to the creation of new forms such as the Tillanas. This became an independent musical format; and, got associated more with Dance.

And, under the revised scheme, the Paata, the vocalized Mrdanga syllables, was taken out from the main body of the repertoire of the stage performances (Sabha-gana); such as the singing of Kirtanas, Kritis etc.

But, its corresponding Svaras, when coordinated with the Sahitya passages, re-appeared as Chitte Svara in the Kritis.

*

Tena or Tenaka

In the Prabhanda rendering, the vocal syllables – meaningless and musical in sound – with many repetitions of the syllables or sounds like tenna-tena-tom, conveying a sense of auspiciousness (mangala-artha-prakashaka), used to be sung after rendering Ragalapiti; but, before the main section of the Prabandha i.e. the Dhruva.

Tena, an A-nibaddha-Samgita (an unstructured, improvised, meaningless, non-verbal music), was taken out of the main body of the structured (Nibaddha) format; and, was treated as a separate segment to be rendered after Alapana (Ragaalapi); but, before taking up the Pallavi or the Kriti. Tena was re-named as Taanam. But, singing Tanam was optional. Every Kriti that was sung need not have to be preceded by Taanam rendering.

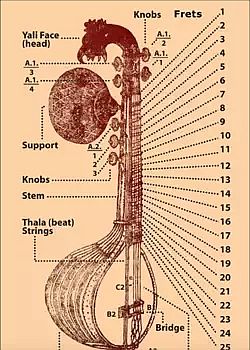

Tena, which was originally used in the Tena-karana of the Prabandha, gained greater importance in the playing of the Veena. The Tanam rendering on the Veena, was derived from the Tena-karana , which was meant to be played on the Veena in the Nanda type of songs of the Viprakirna class of Prabandha. The Taanam (played soon after the latter part of the Alapana) is a particularly endearing segment of the Veena-play of the Karnataka Sangita.

*

Birudu

The Birudu, which was an independent Anga of a Prabandha, was taken out and integrated into the Carana of a composition (usually in the concluding Mudra-Carana). And, it appeared in the Kritis, as Vaggeyakara-mudra; Raga-mudra; or Kshetra mudra

*

Udgraha and Melapaka

Now, as regards the Udgraha , the couplet with which the composition started and which introduced the textual and the musical theme of the Prabandha, it was now assigned the name of Pallavi; suggesting that which is blossoming or is about to bloom-Pallava .

And, the second section, Melapaka, the bridge that connected the Udgraha and Dhruva, now came to be known as Anu-pallavi (that which follows the Pallavi). And the Music here is in a higher register (Svara-sthana); and, its flow is natural.

Now, in the Kriti, the theme introduced in the Pallavi is continued further. The Anupallavi acts as a connecting link between the Pallavi and the Carana. The length of these Dhatus (sections of the song) can be extended, if need be (optional), by introducing, the Antara, as the second theme into Anu-pallavi.

Although the Anupallavi performs a very useful role; it, nevertheless, is not mandatory. In the Samasti-Carana type of Kritis, the composer can straight away proceed from Pallavi to Carana, circumventing the Anupallavi.

*

Abhoga

And, Abhoga, which was the concluding section of the Prabandha, now became a part of the last Carana of the Kriti, accommodating the Vaggeyakara-Mudra (signature) of the composer.

*

Dhruva

At the same time, the number of stanzas in the Dhruva section was reduced.

Dhruva was the main body of a Prabandha-song; and, that which was repeated. It was called Dhruva, because it was rendered again and again (refrain); and, because it was an essential and a constant Anga (dhruvatvat).

Dhruva was renamed as Carana, the feet which takes the Kriti forward; and, also enables it to gain movements. The Carana, at the same time, is the cream, the substance or the body of the Kriti.

Here, in the Pallavi, the theme of the song is briefly initiated. And it is slightly more expanded in the Anu-pallavi; mainly, in order to bridge the Pallavi with the Carana.

But, it is in the Carana, the theme is extensively elaborated in various ways; and, it is here that the composition finds its fulfillment. In the process, there might be slight variations of the contents, depending upon the creativity of the composers, who strive to bring more variety and richness into their compositions.

The third Dhatu Carana, generally, has twice the number of the cycles (Avartanas) of Anupallavi. The melody of the first half of Carana is set in the middle register (Madhyama-kala), closer to the main theme of the Pallavi. And, it also amplifies the theme further.

The second part of the Carana is closer or is similar to the Anupallavi in its music-content; and, finally it leads back to the Pallavi. The entire composition is a unity of several elements and segments, all of which coming together harmoniously, to present a wholesome performance. The Carana is the sum total; the aggregate.

Thus, the Kriti effectively uses the three Dhatus in developing its theme, progressively– in stages. Some scholars, employing the textual analogy, have described the Pallavi as Sutra; Anu-pallavi as Vritti; and Caranas as Bhashya.

[In the traditional texts , the term Sutra denotes a collection highly condensed pellets of references ; Vritti attempts to slightly expand on the Sutra to bring some clarity; and Bhashya is a detailed commentary on the subjects dealt with by the Sutra and the Vritti. ; and, primarily, it continues to be based on the Sutra.]

*

Thus the four Dhatus (Chatur-dhatu) of the Prabandha were remodelled and adopted into the Kriti of three Dhatus (Tri-dhatu). And, the Tri-dhatu format is now established; and, perhaps it will continue to be so for a very long time.

[Although, Prabandha, as a genre, has disappeared, its influence has been long-lasting, pervading most parts, elements and idioms of Indian Music. The structures , internal divisions, the elements of Meter (Chhandas), Raga, Taala and Rasa , as also the musical terms that are prevalent in the Music of today are all derived from Prabandha and its traditions. Many well-known musical forms have emerged from the bygone Prabandha. Thus, Prabandha is, truly, the ancestor of the entire gamut of varieties of patterns of sacred-songs, art-songs, Dance-songs and other musical forms created since 17-18th century till this day.]

Kriti

In Karnataka Samgita, Kriti is an icon of Nibaddha Samgita, a structured composition. A Kriti is explained as that which is constructed (yat krtam tat kritih). It is primarily a pre-composed music (kalpitha Samgita), which aims to delineate the true nature of a Raga in all its vibrant colours. And, at the same time, it tries to harmonize the four essential components of the Kriti: the words of the song (Sahitya); its emotional content (Mano-bhava); its Music (Raga-bhava) and, the rhythm (Laya and Taala). All these elements have to be crafted into a well organized, crystalline, articulate and a very well designed structure, as per the tradition (Sampradaya), satisfying all the requirements prescribed in the Lakshana-Granthas.

A Kriti comprising the three segments (Tri-Dhatu) Pallavi, Anu-pallavi and Caranas, honouring the disciplines of Grammar and Chhandas, and set to appropriate Taala, is the most advanced form of musical composition in Karnataka Samgita.

Generally, the Pallavi is the shortest section of a Kriti. And, Aupallavi could be either be equal in length to the Pallavi or be double that. The Carana will have more number of Avartanas , as also more number of words, as compared to the Pallavi and Anupallavi. Usually, the ratio of Pallavi, Anupallavi and Carana , in terms of their Avartanas and their lengths, is 1 : 2 : 4.However, this is not mandatory.

There could be variations in its structure. In Samasti Carana type of Kritis the Anupallavi and Carana is fused into one segment. It will have just two segments (Dvi-Dathu): the Pallavi, which introduces the musical theme; and the Carana, which expands on that.

In either case, in these Kritis, the Mathu (be it Sahitya, Pada, Svrakshara (sol-fa syllables) or the rhythmic syllables of Taala); and, the Dhatu (Musical content, Nadadthmaka) need to be in perfect harmony:

Dhatu-Matu samayuktam Gitam-ityuchyate budhaih: Tatrah Nadatmako Dhatu Matur-akshara sambhavat

A Kriti might also have a single Carana or multiple Caranas. The lengths and Music-content (Dhatu) of the Caranas could also vary.

A Kriti could be Laya-pradhana or Bhava-pradhana. In the former case, the Laya, the rhythm, is more dominant (say, as in the Raghuvamsa Sudha of Sri Pattanam Iyyer , and the Pancha-ratna Kritis of Sri Thyagaraja). In the latter, the sentiment and emotion that the Kriti depicts would get greater importance (as in Mokshamu-galada (Saramathi ) of Sri Thyagaraja and in the slow-paced (Vilamba-kala) kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry).

*

Despite the importance that has been now accorded to the Kriti, it took a considerable time for it to be called by that name. Even in the Sangita-Sampradaya-Pradarshini of Sri Subbarama Dikshitar, this form of compositions was referred to as Kirtana, although there are some subtle differences between the two formats. Now, hopefully, the term Kriti has come to stay.

*

Although the Kriti as a preeminent musical format was perfected by the Trinity of Karnataka Samgita, the process of its formation had stared much earlier. And, a number of compositions of that nature were written by some eminent musicologists.

The most noted among such scholars was Sri Margadarshi Sesha Iyengar, (17th century), whose Vaggeyakara-mudra was ‘Kosala’. He is also known by the name Pallavi Sesha Ayyangar

His compositions were set in the Tri-Dhatu format of Pallavi, Anupallavi and Three Caranas. He was also the earliest to use the Ragas Begada and Brindavan.a-saranga.

Sadly, all his compositions were said to have been lost. However, the Sarasvathi Mahal Library, Thanjavur, I understand, has brought out a collection of about thirty-one Krits ascribed to Sri Sesha Ayyangar. It is said; the songs therein were culled out of a bunch of manuscripts bundled as ‘Seshayyangaru -Kirtanalu’. And, the collection ended with the phrase ‘Kosalam Kirtanalu Sampurnam’. All the songs are set in chaste Sanskrit.

[ Please click here , for the list of those thirty-one songs.]

Sri Sesha Ayyangar seemed to have influenced Sri Swati Tirunal Maharaja, who in his treatise concerning the Sabda-alamkara–Prasa, the ‘Muhanaprasa- antyaprasa-vyavastha’ often cites from the compositions of Sri Sesha Iyengar, as illustrations of the Prasa-phrases.

It said; Sri Sesha Ayyangar was the first to introduce the rhetorical beauties like, Dvitiya-kshara-prasa, Muhana, Antarukti, etc into musical compositions. The Muhana-prasa, the subject of Sri Swati Tirunal Maharaja’s treaties, refers the rhyming patterns, wherein the same or similar syllable or phrase occurring at the commencement of the first Avarta of a section of a musical composition, is featured also in the second Avarta of the same section.

[The three Sabdalankaras used in composing Sahitya for music are : Muhana, Prasa and Antyaprasa.

Muhana is a type of Sabdalankara, in which the same letter as in the beginning of an Avarta or any of its substitutes occurs in the beginning of the second Avarta. For example, ‘Dinakara Kula dipa / Dhrita divya sara chapa!’

As regards the substitution; if the letter (Akshara) at the beginning of the Avarta is ‘a’, then its substitute in the Muhana will be : ‘Aa,Ai,Au, y,h’. Similarly the if the first letter in the Avarta is ‘i (ee)’ its substitute would be ‘I,e,r’. And , for the letter ‘u’, it would be ‘U, O’.

Prasa is the repetition of the second letter in the first Avarta in the same position in the subsequent Avarta in the same position in the subsequent Avartas. This is concerned only with consonants, not vowels. Prasa can be for a single letter or for a group of letters.

Its example from Sri Sesha lyengar’s Kriti is:

Tanuja sarana pa- Vanaja mukha pari- jana / jagadahita-danuja madahara / manuja tanu dhara / vanaja dala nayana /

Antyaprasa is the repetition of a letter or group of letters at the end of the Avartas. . It differs from Prasa; because, while the Prasa is confined to consonants, here the vowels are also included. For instance, a word like Netram can have Antyaprasa only with words like Gatram, Sutram, etc.; and, not with words like satrum, atrim etc. ]

*

Sri Sesha Ayyangar was also the earliest composer to use the Antarukti, the method of splitting the words, in order to maintain a Prasa. The term Antar +ukti, literally means the ‘in-between utterance’.

The method of Antarukti is by way of inserting one or more syllables between two words. It is done mostly for the sake of maintaining the flow of the Taala. Sri Sesha Ayyangar employed the Antarukti between two words which are in Muhana Prasa. For instance; in the line ‘Hanumantam Chintayeham paVana’, the word ‘Pavana’ was split to render ‘Vana’ as a Prasa to the sound ‘Hanu’. The syllable ‘pa’, here, is said to an Antarukti.

*

Later, Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar, in particular, as also Sri Shyama Shastry and Sri Thyagaraja employed such types of Prasas quite often.

[For more on these, please do read an extensive Doctoral thesis prepared by Dr. Manjula Sriram, under the guidance of Professor Smt. Gowri Kuppuswamy.]

Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry

Most of the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, as per the usual norms, follow the then accepted format of Tri-dhatu, comprising three clear segments of Pallavi, Anu-pallavi and Carana.

At the same time, in a few cases, he deviated from the normal; and, in some of them he also brought in variations by way of building into the structure of the Caranas, the innovative feature of Svarasahitya.

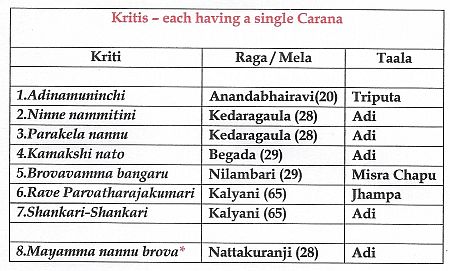

And, of the sixty Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, in eight of the Kritis the decorative Anga (element) of Svara-sahitya is ingeniously structured into the Carana. The group of these eight Kritis comprise those having One Carana (1); Two Caranas (1); and Three Caranas (6).

Of the sixty known Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, 1 Kriti has no Carana; 8 (7+1) Kritis have one Carana; 5 (4+1) Kritis have two Caranas; 4 Kritis have four Caranas; and, the rest 42 (36+6) Kritis have three Caranas.

Of these, Sri Shyama Shastry’s very famous Kriti ‘Devi brova samayamide’ in Raga Chintamani, having a Pallavi and three Caranas is classified as a Dvi-Dathu-Kriti type; meaning, it has only two elements (Dathu): Pallavi and Carana, but has no Anu-pallavi. It is a Samasti-Carana type of Kriti.

*

Eight of his Kritis have each only one Carana; of which in one Kriti – ‘Mayamma nannu brova ‘(28-Nattakuranji, Adi) has a Pallavi; Anupallavi; and One Carana followed by Svarasahitya passage as an Upanga (an auxiliary element).

*with Svarasahitya

*with Svarasahitya

The shorter Krits are simple, with a string of names describing glory of the goddess (Namavali); and praying for protection. In these Kritis, the Pallavi is followed by a short Caranas. And, while singing, the Pallavi line is repeated after the Carana .

*

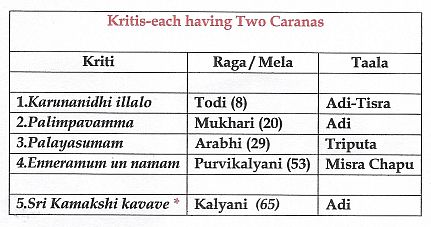

Four of the Kritis , have a structure of Pallavi; Anupallavi; and, Two Caranas. Of these four Kritis, one Kriti ‘Sri Kamakshi Kavave’ (65-Kalyani-Adi) has a Pallavi; Anupallavi; and Two Caranas and a Svarasahitya passage.

*with Svarasahitya

*

And, Four of the Kritis have a structure of Pallavi; Anupallavi; and, Four Carana

*

Thus, apart from the 8 (1+7) Kritis, the rest 52 Kritis have multiple Caranas. Of those 52 Kritis, as many as 43 (37+6) Kritis have three Caranas each. It could therefore be said about two-thirds of his Kritis consist of three Caranas.

Generally, in the case of Kritis having multiple Caranas, the Pallavi and Anupallavi would of the same length; and, the Carana would be double in length.

But, in the case of the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, rarely do the Pallavi, Anupallavi and Carana have a uniform/ proportionate length. They do vary.

In the case of Kritis having multiple Caranas, the Music of the Caranas would, usually, be consistent, until the final Carana, with the Vaggeyakara Mudra, is taken up. So is the case with most of the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, which carry multiple Caranas.

But, while singing, few Kritis – like Mayamma-yeni (Ahiri, Adi) and Saroja-dala-netri (Shankarabharanam, Adi) – the Pallavi is sung and elaborated repeatedly , as a refrain, after the Anupallavi and also after each of the three Caranas. And, the singing concludes with the rendering of the Pallavi again.

*

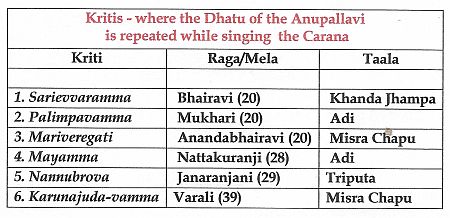

Among the other Kritis having the structure of Tridhatu (Pallavi, Anupallavi and Carana); and having multiple Caranas; in the following cases, the Dhatu (Music) of the Anupallavi is repeated at the second half (Uttarardha) of each Carana.

*

And, in some of the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, each of the three sections of the Kriti – Pallavi, Anu- Pallavi and Carana – are set to different Ragas and different Taalas.

The following Kritis have different Dathu-s for its different Caranas (Dhatu-vyatyaya) . The term Dhatu indicates the Musical content-Nadatmaka – which is enriched by varied Laya patterns, Gamakas, Sangatis and other innovative embellishments.

**

The Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry are normally found with three Caranas. Yet, the Kriti Nannu-brovu in Lalita Raga is found with four Caranas; and, the Kriti Devi-brova-samaya-mide in Raga Chintamani is found without the Anupallavi section.

Normally, the duration of Avartas in Adi-Taala-Kritis is 2-2-4 for the Pallavi, Anupallavi and Carana respectively. With the addition of Chittasvara or Svarasahitya, the number of Avartas of the Anupallavi or Carana will each be increased by another 2 Avartas.

The organisation of the duration of Avartas in Rupaka Taala is 4-4-8 or 8-8-8

The Kriti Marivere, in Ânandabhairavi Raga in Misra Chapu Taala, is found with 8-8-16 ; and with another 8 Avartas for Chittasvara.

The Kriti, Shankari in Saveri Raga is seen with the format of 8+8+8; and, a Chittasvara for 8 Avartas.

Most of the Kritis in Misra-Laghu or Misra-Chapu-Taala are found with the pattern of 8+8+16; and, only in some Kritis, the additional element of Svarasahitya is found with another 8 Avartas, reckoning the Svara part and the Sahitya part as a single unit.

The music settings of the three Angas are separate; and, all the Caranas are sung to the same Dhatu in the compositions of Sri Shyama Shastri.

Only in rare cases –for example, in the kriti Marivere (Ânandabhairavi) and in Brôvavamma ( Manji Raga) – the last two lines of the Carana are sung to the same Dhatu as that of the Anupallavi.

Normally slow medium tempo is employed in the Kritis set in Adi Taala (Irandu) two Kaalai, with profusion of words without any intermediary ending of the words. All the Angas will be set in the same tempo. But in two Kritis we find the number of words is increased in the Angas – Anupallavi and Carana – in Kanaka-shaila in Punnnagavarali; and, in the Carana of the Kriti Mayamma in Ahiri. This increases the tempo of the Angas , as if they are in madhyama-kâla, though in fact they are not.

Angas- Alamkara- decorative features

Sri Shyama Shastry was indeed very proficient in introducing into the Kritis the aesthetic delights, devises or the adornments (Alamkara).These decorative Angas were applied in order to enrich the Dhatu, Mathu and the combination of the both.

His Kritis are rich in the Angas, such as beautiful Svaraksharas, Chittasvaras, Svara-sahitya, as also the intricate Gamakas and variations of the Taala patterns etc.

The Laya-soukhya, the comfort and ease in the rhythmic flow is one of the endearing aspects of the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry. The other related feature is his dexterous use of the Misra Chapu Taala; and, its reversed sequences in Viloma Chapu.

Smt. Vidya Shankar writes:

The beauty of the melodic structure of Sri Shyama Shastry’s compositions lies in the various artistic stresses and strains given to the Musical phrases (Bigu-Sugu). This is the key note of the rhythmic richness found in the works of Sri Shastry. It leaves the impression that every spot is transformed with special charm and grandeur by the infusion of this quality of Laya (change in the tempo) – Shyama Sastry by Smt. Vidya Shankar – Page 55)

*

But, the delight of his compositions is in the Vilamba-kaala, like the spacious, calmly spreading, gently flowing river; which immerses the singer and the listener in tranquil joy.

*

Sri Shyama Shastry also brought into his Kritis, several of the decorative Angas that are generally applied to embellish the Sahitya or Mathu, such as: Prasa; Yati; Madhyama-kala-Sahitya, Vaggeyakara-mudra; Kshetra-mudra etc.

**

Apart from the Alamkara of Dhatu (Nadatmaka) the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry are also rich in the element of Mathu, the literary and rhetorical beauties like Svaraksharas, Madhyama-kala Sahitya, Chittasvaras, Gamakas and varieties of Prasas etc., in addition to various adaptations in coining his Vaggeyakara-Mudras.

Sri Shyama Shastry was an adept in introducing into the Kritis, the aesthetic devises or the adornments (Alamkara) such as beautiful Svara-sahitya, Svaraksharas, as also intricate Gamakas and variations of the Taalas etc.

Sri Shyama Shastry had also used varied patterns in the structure of the Kritis, like appending the Svarasahitya to the Carana; and, employing the Dhatu of the Anupallavi in the Carana again, as in the Kritis ‘Marivegati’ (Anandabhairavi); ‘Sari evvaramma’ (Bhairavi); and, ‘Ninne namminanu’ (Todi).

[In wielding of the Alamkaras such as, the Svarasahitya, Svaraksharas and Chittasvaras, Sri Shyama Shastry was indeed an expert and, the foremost.

But, his use of certain other Alamkaras, such as: Sangathis; Madhyama-kala-Sahitya; Yati-prasa; and, Raga-mudra, etc., were rather limited. There are also no noticeable instances of Taala-mudra. Some of the Sangathis that are now applied to his Kritis are believed to have been inserted by the musicians of later generations.]

*

Let’s, briefly, try to go over some these features, with special reference to the compositions of Sri Shyama Shastry.

Sangathi

The Sangathi, the melodic variations, is a process of embellishing a particular passage of a musical composition, with varied improvisations to bring out the different shades of the Sahitya and also of the Raga, without, however, altering the Mathu (Sahitya or words) of that segment

The Sangathis are, generally, improvised while rendering the Pallavi or Anupallavi (rarely in Carana); and at the same time, retaining the words of the text (Sahitya). Though they are sung to the same Sahitya, each Sangati is a logical progression from the previous one.

In certain cases, with the recurrence of the musical phrases, the Sahitya gets hidden under the melodic variations. And, in certain others, in the Sahitya-bhava-Sangatis, the meaning of the Sahitya gets emphasised, to stimulate its effect.

The Sangathis are not developed from the opening phrase; but, only in the later portions. But, the Sthayi and tempo may be varied; and, increased gradually from Sama-kala, to Madhyama-kala and to Durita-kala. Or else, they may be rendered at the tempo assigned for that segment of the Kriti. With the increase in the tempo; and, with variations, the length and time of the Pallavi or Anupallavi get elongated.

And, in either case, the Sangathis contribute in bringing out the various shades of the Raga; and also the complex layers of the emotional aspects and meaning of that particular Sahitya. Hence, the Sangathis being endowed with the potential to bring forth varied possibilities are used as creative ornamentations at various places.

In some Kritis, the Sangatis are applied only to the Pallavi and Anupallavi. In certain other cases, the Sangathis are applied either at the commencing part of Pallavi; or at a particular part of the Kriti; or, it is applied with variations in other parts as well.

Sangathi is a much used Anga in the Kritis of Sri Thyagaraja. But, Sangathi is not a major issue in the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry; but, still there are some instances of Sangathi prayoga.

*

In the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, the Sangatis are developed gradually and extended to successive Avartas, heightening the Raga-bhava and the Sahitya-bhava; and, the final Sangathis spread over the full line.

But, While singing the Kriti Saroja-dala-netri’ (Shankarabharanam) , we find that the Sangathis are developed by the performers and extended over the whole Avarta in the second line of the Pallavi. The First Sangati is developed from the place ‘Sri Meenaksamma’; while the second is developed from the beginning with slight changes occurring here and there.

And, while singing the Kriti Durusuga (Saveri) the Sangathis, as developed by the performers, fill in the gaps that are without Sahitya, at the end of first Avarta of the Anupallavi. Here, the Sangathis are executed with a series of ’Aaa-karas’ (or non-verbal sounds); and, no words are added even after the ‘Aaa-karas’.

The second and Third Sangathis are developed to fill in the gaps, by breaking up the Sahitya phrase and elaborating its component-words in a variety of ways. And, by the gradual increase of the Svaras in two speeds (Druta), the Sangathis are progressed.

Svrakshara

The device (Anga), which adds lustre and delight to both Dhatu and Mathu are the Svaraksharas. It is a variety of Sabda-alamkara; and, is described as Dhatu-Mathu-Samyukta-Alamkara, in which the Sahitya syllable (Mathu) and the Svara syllable (Dhatu) are identical or sounding similar.

This structural beauty, termed as Dhatu-Mathu-Alamkara, is a happy confluence of both the types of decorative elements: Svara (sol-fa-notes); and, the identical or similar sounding syllable (Akshara) of the Sahitya (lyrics). Here, the Svaras are rendered in the proper Svara-sthana assigned to them (order or Krama).

They figure in almost all the musical forms like: Kritis, Varnas,, Raga-malikas, Svarajatis, Tillanas etc. The Svarakshara can be Hrasva (short) or Dheerga (long) depending on the nature of the syllables. E.g.: Pa- Da- Sa- Roja (Dheerga Svaraksharas) in ‘Pada saroja-muna nammi ‘the Carana of the Navaragamalika Varna.

The Svaraksharas occurring in his Kritis blend harmoniously and naturally with the Sahitya; and, give forth a pleasant feeling. These are generally found in the beginning of Pallavi, Anupallavi or Carana.

But, Svarakshara is an Alamkara that can be noticed and enjoyed only in vocal music; since, in the instrumental music, the Sahitya cannot be explicitly brought out.

*

The art of composing Svarakshara is often compared to Chitra-Kavya or ornamental poetry, where the syllables and words are graphically presented as patterns or images. Creating the right type of beautiful sounding Svaraksharas; and, introducing them at appropriate places in the Kritis is an art, a precious gift; and, it is also a measure of the musical and literary capabilities of the composer.

Sri Shyama Shastry excelled in structuring into his compositions delightful Svarakshara passages, in all their forms.

In the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastri, we find the extensive use of Svaraksharas of both the varieties: Shuddha and Suchita Svaraksharas. They occur more often as a two or three lettered word, than as single syllable.

The Svaraksharas could be either direct (Shuddha), where the literary (Sahitya) syllables are exactly like the Sol-fa notes; or, they could be mere suggestive (Suchita), where the Sahitya-syllables (Akshara) might sound slightly different from the Svara-syllables, because of the vowel-changes (Svara-vyatyaya) in the Sahitya syllables

In any case; it is said; the Svaraksharas should convey some meaning by themselves or when combined with other non-Svarakshara syllables.

The Sahitya-(Sari) evvaramma (Bhairavi-Adi) is an instance of Shuddha- Svarakshara indicating the notes Sa and Ri. And, in the Kriti ‘Devi brova samaya’ (Punnagavarali), the term ‘Sama’ is set to Svaras ‘Sa-Ma’. And, in the Kriti Kamakshi Bangaru (Varali), the Svaraksharas are Ga-Ma.

The combinations like ‘Sa-Ma’; ‘Pa-Ri; ‘Sa-Ri’; ‘Ga-Ma’; ‘Ni-Dha’; ‘Dha-Ri-Sa; and, ‘Pa-Dha-Sa’, are some such Svaraksharas found in the Kritis.

And in his other Kriti, the phrase in ‘Du –ru-su’ ga krupa’ (Saveri-Adi) suggests the sounds Du-Da, ru-ra , su-sa. And, in his another Kriti (Mi) nalochana brova (Dhanyasi-Chapu) the Sahitya-syllable ‘Mi’ suggests (Suchita) the Svara Ma.

Sri Shyama Shastry has also employed a combination (Misra) of Shuddha-Suchita Svarakshara, as in the line: Ri-Ga-Ma-Pa-Dha-Ni , corresponding to ‘Sri- Ka –Makshi – Ni’.

*

In some of his Kritis, the Pallavi, Anupallavi and Carana begin with Svaraksharas. For instance; (Sa-ri) evvaramma; (Pa) rama-pavani – Anupallavi; and, (Ma) dhava Sodari – Carana, are Svaraksharas.

And, his other Kritis in Yadukula-kambhoji, Mukhari, Kalyani and Ritigaula, the Svarasahitya commence with Svaraksharas.

Similarly, in the Kriti ‘Marivere-gati’ (Anandabhairavi) the Svarasahitya ‘(Pa da) yu-ga’; and, ‘Janani Ninnu vina ‘have some Shuddha Svaraksharas.: Pa-Dha-Pa-Ma / Pa-da-yu-ga.

And, in one more instance of the Kriti Ninne-namminanu (Todi) the Svaraksharas appear in the Svarasahitya in the line ‘kamala bhava danuja ripu nuta pada’-

- (Ga Ma) Ga Ri Sa (Dha) Ma Ga Ri Sa (Ni Dha) Ma Ga(Ga) Ri

- (Kama) la bhava; (da)nu ja ri pu (nu ta) pa da (Ka) ma

There are many Svaraksharas here, throughout the Svara Sahitya

**

The three Svarajatis have numerous examples of both Shuddha and Suchita Svaraksharas in the Svarasahitya.

And, similarly, his Varnam ‘Dayanidhe mamava’ (29-Begada, Adi) starts with a Suddha Svarakshara in all its three Angas.

Chittasvaras

Chittasvara, an Alamkara-Anga, is a series of Svara phrases (Sol-fa passages) set in order to enhance the beauty and the musical appeal of a composition. And, in a Kriti, the Chittasvaras are, usually, rendered at the end of the Anupallavi; or towards the conclusion of the Carana; or at the end of each section in Raga-malika-Kritis.

They may be in the Sama-kaala (same tempo) or in the Madhyama Kaala. But, generally, the Chittasvaras are sung in Madhyama-kaala at the end of the Carana, even if they were rendered in Sama-Kaala after the Anupallavi.

In Sri Shyama Shastry’s Kriti Marivere (Anandabhairavi), the Chittasvara is sung in Dhuritha (two speeds) after the Anupallavi; and, the Chittasvara-Sahitya– is sung after the Carana, in the corresponding Svara.

Where the Svara-sanchara of the Chittasvaras is integrated by the composer himself; it might even be considered as pre-composed Kalpana-svaras. And, in addition, the performer on the stage, the singer, could also improvise in all artistry to illuminate the Raga-bhava.

Generally, the Chittasvaras are composed by the Vaggeyakara himself, as passages of few Avartas of Svara-sanchara. But, there are many instances, where they were inserted at a later time by his disciples or descendents.

This decorative Anga comprising of Svara passages of 2 or 4 Avartas (cycles) would be set to the tempo (Kaala) of the Kriti. The Avartas may vary in accordance with the kaala to which the segment of the Kriti is set. For instance; if the Anupallavi is to be rendered in Vilamba-kaala, then it would be Vilambita Kala Chittasvara; and, it would be Dhruta-laya-Chittasvara after the Carana.

The Laya or the rhythm of the Chittasvara also varies with the Taala. For instance; in the Adi Taala, the recurrence (Avarta) will be 2 to 4; and, in the Rupaka Taala, it will be 8 to 16 Avartas.

Based on the tempo, the Chittasvaras are classified either as Sama-kala-Chittasvara or as Madhyama-kala-Chittasvara.

[In the Kritis, ‘Devi mina- netri’ and ‘Mariveregati’, the Chittasvaras are being sung also in the Madhyama-kala (second degree of the speed).]

The Chittasvaras could again be classified as those that end evenly (Sama) or as those with Muktayi patterns or Makuta–Svaras, peaking to a higher note towards the conclusion. The Makutas are structured with short, crisp and attractive Svara phrases. And, the Makuta could again be short (Hrsva) or Dheerga (elongated). In either case, the Muktayi should be proportionate to the length of the Chittasvara.

A further innovation is brought into the rendering of the Chittasvaras.

Normally, it is sung as a straight or a linier phrase (Anuloma). But, they can even be rendered in the reverse (Viloma) order of its set Svaras. However, the Viloma type of Chittasvaras can be introduced only in the case of those Kritis, which are set to Ragas having symmetrical Arohana (ascent) and Avarohana (descent) in their Svara structure. Such Ragas could be Sampurna (having all the seven Svaras), Shadava (having six of the seven Svaras in its scale) or Oudava (having only five of the seven Svaras in its scale).

In certain other instances, a corresponding Sahitya, known as the Chittasvara-Sahitya would also be inserted.

Another variety is the admixture of Svara-phrases with the Jati or the Pata-ksharas – (Sollukattu). These are known as ‘Sollkattu Svaras’. And, in the songs, specially meant for Dance, the Sollukattu syllables would be mingled with Sahitya (Sollukattu-Sahitya).

[Sollukattu -(or Pataksharas– vocalized Mrdangam syllables or beats of other percussion instruments or cymbals)- is said to be a variety of Chittasvara, indicating the arrangement of rhythmic beats in a time sequence (Taala-pramana).

Here, the Svara passages are interspersed by Jatis (sequence of drum-syllables measuring the time-units). Its Dhatu will be the same as that of the Chittasvara, which in turn will be in the tempo of the Kriti. The Sollukattu in the Anupallavi will be sung in Vilamba -kala (first degree of speed); and in the Carana, it will be sung in Madhyama-kala (second degree of speed)

As the section is sung, one will hear the Svaras and Jatis alternately, providing the Kriti some variety and depth.

A variation of Sollukattu is Sollukattu-Svara-Sahitya, where, in addition to Svaras and Jatis, suitable Sahitya would also be composed for the passage.

Sollukattu-Svaras are commonly used in the compositions that are dedicated to those gods who are associated with Dance, such as, Ganapthi, Nataraja or Krishna.

Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar is believed to be the first to use this Anga in a Kriti. ]

*

It appears that the Chittasvara-prayoga was not in much use before the time of the Trinity. Even among the Trinity, it was only Sri Shyama Shastry who experimented with Chittasvaras; and was also the first to introduce the Svarasahitya into the Kritis.

He used the Chittasvaras in quite a number of his Kritis.

Svarasahitya

Svarasahitya refers to Chittasvara passages (Dhathu) adorned with appropriate Sahitya (Mathu) ingeniously structured into the Carana. And, Chittasvara are a set of Svaras (sol-fa passages) integrated into a composition, to enrich its beauty. It is sung at the end of the Anupallavi or the Carana.

The Svarasahitya is a musical passage, where every letter of the Sahitya line corresponds to a Svara note. If the letter (Akshara) in a word is elongated (Dheerga) the corresponding the Svara is also elongated – according to the degree (Dheerga) long, or Hrsva (short) letters; and, the Svaras will have their corresponding duration..

The Svarasahitya could perhaps be called as musical notations that trace the progression in the process of noting the Svaras and Sahitya elements of the composition.

*

The Svara-line of the Svarasahitya passage is affixed to the Anupallavi; and, the corresponding Sahitya line is appended to Carana; before the Pallavi is rendered again as refrain, in each case.

That is to say; the Svarasahitya, is an Alamkara, which contains both the Dhatu and Mathu elements; and, it is built into a Kriti. And, while rendering the Kriti, the Dathu portion of the Svarasahitya will be sung after the Anupallavi; and, its Mathu portion after the Carana. Thus, the theme and the content of the Svarasahitya will be apportioned between the Anupallavi and the Carana.

The presentation of this passage enhances the beauty of the rendering of the composition.

The rendering of the Chittasvara and Svarasahitya passages in the middle of a composition helps to establish the unique nature of the Raga; particularly ,in the case of rare and Vakra Ragas.

It also facilitates the displaying rare Prayogas, leading to Kalpana-Svaras; thus, lending variety and attractiveness to the performance, particularly when skilfully supported by the accompanying musicians. The audience in the concert too love such engaging passages .

The Svarasahitya must be in conformity with the Sahitya of the Anupallavi and of the Carana. The syllables of the Mathu have to be in accordance with the Svaras or the Dhatu syllables.

Though prosodic beauties are not strictly complied with, as required for the Svarasahitya, some literary ornamentation like Yati and Prasa do occur in few cases. Here, the Prasa-akshara is independent of the Anupallavi and Carana. And, the Sangathi or such other repetitive improvisations are not included.

*

According to Vidushi Smt. Vidya Shankar, the Svarashitya is a miniature form of Svarajati, the speciality of Sri Shyama Shastry. And she further illustrates a Svarasahitya passage, with reference to a Kriti of Sri Shyama Shastry.

A remarkable feature of Sri Shastry’s compositions is the matching of the Mathu and Dathu i.e. the Sahitya with its corresponding Svara-structure. With absolute ease, he establishes a perfect harmony with the syllabic duration with the melodic duration of the phrases.

Sri Shastry’s dexterity in expressing this pattern of rhythmic structures has won him the prime place among the composers of Svarajatis.

In its miniature form, the structure of the Svarajati is transformed to a Svarasahitya-arga in most of his Kritis. This technique was adopted and followed by his son and disciple. I shall wind up this by the illustration of a Svarasahitya of Shyama Shastry’s Varali-Raga-kriti ‘Kamakshi Bangaru’ in Chapu Taala:

Na maanvini vinu Devi / Nive gatiyeni namminanu / Mayamma vegame karuna judavamma / Bangaru Bomma (Kamakshi)

*

Sri Shyama Shastry might have found the Svarasahitya very fascinating; and, challenging too. This Anga, which presents a melodic line, projected by Svara syllables, to which meaningful text (Sahitya) is appended, is creatively woven into his Kritis as also into his Svarajatis. This indeed is a magnificent achievement.

This element of ornamentation (Alamkara Anga), the Svarasahitya, is said to be an original contribution of Sri Shyama Shastry to the development and the beautification of the Karnataka Samgita. He was the first composer to introduce this decorative Anga into the Kritis. He did extremely well in this aspect; and, used Svarasahitya extensively in his Kritis and other types of compositions, such as Varnas and Svarajatis.

The Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry contain many enchanting Svarasahitya passages, with independent Prasa, so that they can be sung at the end of the Anupallavi and also at the end of each Carana.

He seemed to be fond of the latter part (Upanga) of the Svarasahitya, where a Svara-passage comes in the Anupallavi; and, its corresponding Sahitya-passage comes in the Carana

Since then, the general practice has been to sing the Dhathu part of the Svarasahitya at the end of the Pallavi; and, the Mathu part at the end of the Carana.

*

Sri Shyama Shastry does not seem to have composed any Svarasahitya, in the Madhyama Kala, per se. Generally they follow of the tempo of the Anupallavi or the Carana, as the case may be.

For instance; in his Kriti ‘Durusuga’ (Saveri) the number of syllables per beat is the same both in the Music (Dhatu) and in the Svarasahitya. But, in his another Kriti ‘Marivere’ (Anandabhairavi) there is an apparent stepping up of the tempo of the Svarasahitya. Here, in this Kriti, its main body, the Pallavi, Anupallavi and the Carana are built to a cycle of 4 to 5 syllables per beat; whereas, the Svarasahitya which follows the Carana, has around 6 to 7 syllables per beat.

*

In some of the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, the Svarasahitya was added at a later time by his descendants or by his disciples.

For instance; it is said, the Svarasahitya for the ‘Palinchu Kamakshi’ (Madhyamavathi) was composed and inserted by Annaswamy Shastry, the grandson of Sri Shyama Shastry. And for the Kriti ‘O Jagadamba’ (Anandabhairavi), the Svarasahitya was submitted as Guru-dakshina, by Sangita Swamy, a Sanyasin and the long lost first disciple (Prathama-sishya) of Sri Shyama Shastry.

The Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry adorned with many beautiful Svarasahityas, with independent Prasa-aksharas.

*Varna

Madhyama-kala Sahitya

Madhyama-kala Sahitya, one of the optional sections in a Kriti, usually follows the Anupallavi or Carana or both. It will usually be half the Avarta of the Pallavi or Anupallavi, having a proportionate relationship with the length of the Carana.

This Anga is found mainly in the Kritis of Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar. And, in his Kritis, this section also occurs after the Samasti-Carana.

The Madhyama-kala-Sahitya passage will, usually, be set in the same tempo as of the Kriti. This will be usually in 2 or 4 Avartas. But, in case of Kritis having Samasti-Carana, the tempo would be doubled. There is no scope here of Sangatis or other elaborations.

*

Sri Shyama Shastry used this Anga rather sparingly. But, in his Kriti O Jagadamba (Anandabhairavi) the entire Anupallavi is in the Madhyama-kala; besides, the Madhyama-kala-sahitya is in the Carana and in Svarasahitya.

In the next Part we shall take a look at the other Angas such as Prasas, Gamakas,

Taala etc.,; and, also at the Language of the Kritis

Continued

In

The Next Part

Sources and References

- Indian Culture, Art and Heritage by Dr. P. K. Agrawal

- Shodhganga chapter Six

- Shodhganga Chapter Seven

- Shodhganga Chapter VI

- Shodhganga Chapter VII

- Shodhganga handle

- A Voyage through Dēśa and Kāla

- Compositions of Shyama Shastri (1762-1827)

- Origin and development of Indian music

- https://archive.org/stream/composers00ragh/composers00ragh_djvu.txt

- https://archive.org/details/composers00ragh/page/46/mode/1up

- Prof. P. Sambamoorthy

- https://ebooks.tirumala.org/downloads/syamasasthri.pdf

- https://www.sangeethapriya.org/tributes/shyamakrishna/dl_krithis.html

- http://www.medieval.org/music/world/carnatic/shyama.html

- http://carnatica.net/special/shyama.pdf

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/173579/11/11_chapter%204.pdf

All images are taken from Internet

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**