The other day I was reading the blog posted by my friend Shri Giridhar Gopal on forced conversions of Hindus to other religions. I agree, such methods are reprehensible and must be condemned.It was not merely Islam but Christianity too that targeted Hindus and sought religious conversions to its faith by creating deprivation and loss of self-esteem, through the abuse of the power of the state against Hindus. For instance, in 1545, King John III of Portugal commanded the then Governor of Goa to ensure that neither public nor private idols of Hindu heathens be allowed on the island of Goa and that severe punishment be meted out to those who persist in keeping them. Thereafter, a terrible inquisition followed during which Hindus were killed, brutalized and their temples razed to the ground. Yet, only a minority of Hindus converted to Christianity. Hindus suffered prolonged and atrocious persecution but somehow survived as a religion of a vast majority on their own soil.

That speaks of the resilience of Hinduism and also about the futility of forced conversions. This fact was not lost on the Church which over the centuries developed soft methods in tandem with strong-arm tactics, to convert targeted groups.

Shri Giridhar Gopal also rightly observes that a thinking mind should be allowed to decide which religion he or she must follow, according to his or her conscience. He was obviously talking about conversions that come about because of one’s convictions.

That question also engaged the attention of the Church which pondered how to bring about change in ones conviction, particularly if one belongs to an older and well established culture as in India; and especially when Hindus do not consider any religion as wholly false and regard all religions as having some errors in them and that all religions lead to God; and therefore do not see the need for forcing a conversion.

That question gave raise to another issue: what is a proper way of understanding conversion?

The latter question was born out of the realization that most people do not really convert; the old habits die hard; and that most people remain, in some form or other, in the religion into which they were born. They, often, will change. Those that change find themselves in situations with a bit of conflict, and are perplexed about the issue. There was more than one motivation that drove them to change. They tilted into the new religious option in different ways; some through their heart and emotions; some, more in desperation than in real hope; and some through their intellect. In any case, what they might have disliked was certain aspects of their old religion; but not their family, society and the culture they were born into. To them, an alien religion divorced from the surrounding culture, was an artificial implant.

[ Please do click here and read Roman Catholic Brahmin]

It was therefore necessary to retain the ambiance of the host culture even after one crossed over, for whatever reason, to the new religion. The new religion should preferably nestle in to the indigenous social and cultural practices without causing much emotional disturbance. The priority was to get the lost flock; molding them in to the desired cultural patterns could come later. That was the approach of the Church in Southern India.

Accordingly, the Missionaries in Southern India of the earlier times found it prudent not to talk about social customs and observances of caste practices, while focusing on the virtues of the New Religion; since those matters belonged to the civil society and varied from caste to caste. Therefore, caste, symbols and race were treated as relative and not the object of religion. The object was not to talk about social customs, but to show the Christian way to salvation. The approach was so designed as to make a distinction between religion and culture; and to show religion is different from culture. According to which, the symbols and signs of Brahmins, such as the thread and the tuft are social not religious; and a Brahman convert can continue his caste practices and those are not to be construed as ‘idolatry’. In other words, one could talk about religion without referring to culture of the people.

The belief that religions can enter into dialogue without referring to cultural symbols that might be used in religious rituals was initiated in the Catholic Church by Roberto de Nobili (1577- 1656), a Tuscan Jesuit Missionary who arrived in the Southern city of Madurai during the early years of the seventeenth century.

***

Roberto de Nobili was born in Montepulciano, Italy, in 1577, 16 January1656. His father served in the papal army which fought the Turks during crusades. He joined the Society of Jesus in 1596 and reached Goa on May 20, 1605. After a stay in Cochin, he arrived in Madurai the temple city and a great cultural centre, during Nov 1606.

He observed that the Sadhus and Brahmins were highly respected in the society. He also noticed that generally the parangis, the Portuguese foreigners, were poorly regarded; and were looked down. The local elite found the Europeans’ leather shoes, alcohol consumption, carnivorous diet as well as their primitive hygiene rather offensive. That was compounded by the foreigners’ disdain for the indigenous religion and culture. They were therefore kept on the outer fringe of the respectable society.

De Nobili reckoned that converting only the illiterate and the lower classes of Indian society brought no credit to Christ. In 1607 he wrote to one of his relatives: “In spite of twelve years of work, our Fathers have not been able to make a single convert. At the most, they have baptized in articulo mortis three or four sick people.” He looked for a different method of approach. It seemed to him that the Hinduism could only be broken from within. He concluded that if Christianity was to be a credible religion in India, it was imperative to convert educated upper class and Brahmin scholars. That would help him serve his mission better.

**

Having that in view, he tried entering in to the core of the orthodox society. He distanced himself from the image the people had about the uncouth Portuguese. He presentedhimself as a Kshatriya, a Raja_sanyasi from the country of Roma. People of Madurai did take notice of him but could not appreciate the strange amalgam of a foreigner, a Kshtriya and a sanyasi spreading the message of an alien god. He remained at best an object of curiosity and was not taken seriously.

Having that in view, he tried entering in to the core of the orthodox society. He distanced himself from the image the people had about the uncouth Portuguese. He presentedhimself as a Kshatriya, a Raja_sanyasi from the country of Roma. People of Madurai did take notice of him but could not appreciate the strange amalgam of a foreigner, a Kshtriya and a sanyasi spreading the message of an alien god. He remained at best an object of curiosity and was not taken seriously.

De Nobili was fully convinced that to make any impact on a sophisticated culture, he had not only to learn the language but also to adapt himself to the way of life of the people. The immediate inspiration to Roberto de Nobili, in that regard, was another Italian Jesuit, who preceded him by a few decades.

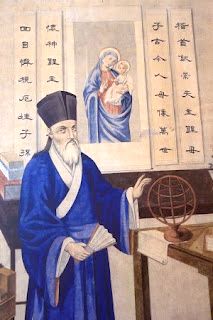

He was Matteo Ricci who lived in the mid-sixteenth century. He was one of the few missionaries allowed to enter the Chinese society. He transcended his status as a foreigner by mastering the Chinese language and the Confucian literary classics. The imperial court and the educated class recognized him as a distinguished scholar. He wore the appropriate attire for a Chinese scholar, “…silk dresses and published works on such topics as astronomy, science and philosophy.” He was particularly admired for his map-making skills as well as for being an accomplished teacher of mnemonic techniques, that is, ways of memorizing things. Ricci did not initially concern himself with making many converts. As a Confucian scholar he was convinced “…that the ethical precepts of Confucianism were reconcilable with Christian morality.” He attempted reconciling the Gospel with Confucianism which played an important role in Chinese culture. Yet, he was highly regarded by the Chinese. At his death, at age 58, hundreds paid their respects as his body “lay in state.” The emperor decreed that he be buried in a special tomb, an unheard of honour for a foreigner and even rare for any Chinese.

Ricci’s entire project was however rejected by the Vatican because it could not favor Ricci‘s endorsement of the veneration of family ancestors. However, many, even within the Church, considered its decision a retrograde step.

Roberto de Nobili in consultation with his superiors, the Archbishop of Caranganore and the Provincial of Malabar (Father Laerzio) derived a plan of breaking in to the Hindu society. Robe rto de Nobili decided to follow the steps of the fellow Jesuit, Ricci. Like Ricci, he took great care not to impose his Western views or culture on the local population. Instead, he tried becoming one among them by adopting the role, customs and attitude of a sanyasi.

rto de Nobili decided to follow the steps of the fellow Jesuit, Ricci. Like Ricci, he took great care not to impose his Western views or culture on the local population. Instead, he tried becoming one among them by adopting the role, customs and attitude of a sanyasi.

He was determined that he has to be a Brahmin mendicant in order to be effective as a religious preacher. Accordingly, he called himself a Romaca Brahmana; he shaved his head, applied gandha (sandalwood paste), started wearing ochre-robes, wooden shoes; carried danda (stick) and kamandalu (water jug) like a Hindu monk. He also gave up meat. He engaged a Brahmin cook, ate only rice and vegetables and started sleeping on the floor. He learnt Tamil and Sanskrit from a Telugu Brahmin pundit Shiva Dharma; and in a while became quiet an adept in southern languages. He studied Sanskrit texts and holy books; and started writing Christian psalms and prayers in Tamil patterned on the Indian songs and prayers.

He opened a school of catechism and slowly started introducing Christian theology.He then built a church and presbytery on a site granted to him by a cousin of the king of Madurai. All his servants were Brahmins. He lived and dressed like a Sannyassi. It is also said that he wore a three-stringed thread across the chest just like Brahmins. He claimed the three-stringed thread represented the Holy Trinity of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit . He became an Iyer (preceptor) to local people who started venerating him for his austere life, kind manners and healing powers which he had acquired modestly.

He was careful not to criticize the local customs and practices. For instance, he did not criticize the customs like Sati though, it is said, he witnessed scenes of women committing Sati on the death of Nayaka of Madurai. Instead, he praised the extraordinary courage and steadfastness of those women. He also did not criticize or comment on the caste system prevailing in the Hindu society. He appeared rather convinced that the caste customs were not all to be condemned. Certain of these, were civil and social in character, he said, and might be tolerated. Nobili, in fact, avoided all public intercourse with the lower castes.

Roberto de Nobile’s intense study of both the Hindu religion and culture gave him access to the people whom he came to admire. His way of life, his move from a house into a simple hut and his vegetarian diet of rice and Vegetables signified identification with the people of the land. He was able to secure a sympathetic hearing from the Brahmins.

His methods seemed to work. In a short period of time he succeeded in gaining more than a hundred converts in the very city where his fellow missionaries had laboured in vain for years.

The representatives of the Church in Portuguese Goa were however alarmed at the unchristian ways of De Nobili and complained to the Vatican about his dangerous methods and the consequences of indianizing the Holy faith. They were scandalized by the extent of De Nobili’s adaptation of the local culture. They powerfully argued that sacred symbols of Christianity cannot be understood and revered in isolation of the ethos and the culture from which they originated. “The Gospel message cannot be purely and simply isolated from the culture in which it was first inserted, nor, without serious loss, from the cultures in which it has already been expressed down the centuries…. It has always been transmitted by means of an apostolic dialogue”.

They were in effect stating that the Catholic religion has particular cultural roots; and it cannot entirely be “disincarnated” from its historical origins in the culture of Jesus. The more one suppresses or modifies the language of the Bible and its symbols on cultural grounds, the more one trivializes culture of the Bible itself. Similar is the case with the liturgy and other cultural expressions of the Church, which has carried the mystical life of Christ through the centuries. The Christians wherever be they placed should follow the methods, the forms, the symbols, the rituals and the dictates of the Holy See, which is the sole authority on all matters religious and secular, concerning the life of Christians

His fellow Jesuits in Madurai too charged him with countenancing superstition by allowing use of pagan rites; and encouraging schism and dissension by permitting no intermingling, even within the church, between the Brahmin converts and the lower caste converts.

De Nobili responded by submitting to the Holy See a detailed exposition of his views on religion, culture and the relation between the two. He gave ‘a norm by which we can distinguish between social actions and those purely religious’ (‘quod regulam, qua dignosci debent, quae sint apud hos Indos politica et quae sacra’).

He argued that religion was different from culture. The religion, he said, was concerned with salvation of human beings and to reveal the ways to attain that salvation. The object of religion is not to talk about social customs and observances of castes. The caste, symbols and race are all relative and are not the object of the religion; they are merely the socio-cultural patternsand had no religious meaning. These matters belong to the civil society.”These ceremonies” he asserted “belong to the mode, not to the substance of the practices; the same difficulty may be raised about eating, drinking, marriage, etc., for the heathens mix their ceremonies with all their actions”. Besides, culture is not personal; it is always a collective possession. Religion does not need to be empirically connected to cultural conditions. One can therefore talk to a person about religion without referring to culture. The religious doctrines can stand independent of the cultural symbols.

As regards the charge of schism he denied having caused any such thing. He explained that he had founded a new Christianity, which never could have been brought together with the older. The separation of the churches, he pointed out, had been approved by the Archbishop of Cranganore; and it precluded neither unity of faith nor Christian charity.

He explained that his taking up Brahmin life style, was motivated by his keen desire to convert the Brahmins to Christianity; and not to enter into a dialogue between cultures and religions. His thrust was essential to break in to Hinduism; and in a sense his life style was a weapon to win the enemies. The earlier missionaries failed to understand the ways of entering in to the Hindu society; and therefore their success, if any, in spreading the Gospel was dismal. His method, he said, had been working very well and had brought into the true faith hundreds of upper castes and Brahmins, who would truly be the future of the Faith in India. He argued, what was of paramount importance was spreading the Gospel and converting upper castes in large numbers; and it did not really matter whether they retained or not their social – cultural symbols and patterns. In any case the core concern of the Church is the Faith and not culture.

He defended himself by providing documentation of the fact the early church had sanctioned and integrated different pagan customs and rituals. In defense, Nobili wrote a comprehensive document that carefully outlined his position. It was entitled An answer to the objections raised against the method used in the new Madurai Mission to convert pagans to Christ.

In this defense Nobili supported his actions with the history of contextualization. He cited the council of Jerusalem in Acts 15 and also an unusual document containing the instructions St. Gregory sent to St. Augustine of England in the fifth century.

He traced the history and the development of Christianity and explained how the Christian faith in its early years until the fourth century absorbed and adopted the Greco Roman cultural symbols , patterns , behaviours and religious icons and rites in order to establish itself in the civilized world. He argued that a similar approach should be adopted in India too. His method, he submitted, would also demonstrate that Christianity is not confined to one race and that all races can live in it, and that caste or culture is not religion. A Brahman convert, if he is not comfortable giving up his caste marks and symbols could be allowed to retain his caste practices , so long as they do not interfere with his Christian faith. In that sense, he said, certain symbols and signs of Brahmans such as ‘the thread and the tuft are social, not religious, insignia’ (‘Lineam et Curuminum non inter superstitiosa, sed inter politica esse’) and these are not even the exclusive symbols of any one group.

De Nobili argued that the adoption of brahmanical customs was the only way in which Christian faith could be presented. He insisted that his method was in accordance with the practices of the early Church: whatever was not directly contrary to the Gospel could be employed in its service.

Initially, the reports sent against him produced an unfavorable impression, but after his defense was examined by the tribunal set up by him, Pope Gregory XV (pope from 1621 to 1623) refrained from issuing a condemnation. On 31 January, 1623, Gregory XV, by his Apostolic Letter, Romanae Sedis Antistes took an interim decision ” until the Holy See provide otherwise”, in favor of de Nobili,. Thus, de Nobili was tacitly vindicated.

A Bull of Gregory XV (1623) authorized the Brahmins and other “Gentile” converts to wear cordons (sacred thread) and kudumis (tufts), the other caste insignia such as ashes or sandal paste. The condition prescribed by the Bull was that a Cross could be attached to the thread, if so desired, provided both the Cross and the thread are handed to the converts by a Catholic priest who would bless them by reciting prayers approved by the ordinary of the district. The wearing sandal, ashes, ornaments and emblems were allowed for general use “for the sake of adornment, of good manners, and bodily cleanness, without any respect to religion and also not in satisfaction of a superstition”.

As to the separation of the converts based on their castes, it was said that the pope understood that the customs connected with the distinction of castes, are deep rooted in the ideas and habits of Hindus. An abrupt suppression, even among the Christians would impede the growth of Christianity. They were to be dealt with by the Church, as had been dealt with slavery, serfdom, and the like institutions of past times. In other words, the Church found it prudent to distance itself from the caste issue.

Robert de Nobili, encouraged by the stand taken by the Vatican continued with his methods. It is said that he succeeded in converting 1208 members of higher caste including twelve eminent Brahmins; and 2675 of lower castes. One of his early converts was his teacher Shiva Dharma himself, who of course continued to sport his tuft and the sacred thread with a Cross attached to it. That made it easier for others to retain the traits of their earlier faith and yet become Christians. On the advice of Nobili, the superiors of the mission and the Archbishop of Cranganore resolved that henceforward there should be two classes of missionaries, one for the Brahmin and the other for the lower castes.

As a part of his exercise to indianize the Catholic Mass, De Nobili introduced Indian terms in to the Catholic terminology. For instance, Kovil was used by him in place of Church; Prasadam for Communion; Aiyar for Priest, Vedam or Yesur Vedam for the Bible, and Poojai for Mass. Nobili chose to take on the name Tattuva Bodhakar or Teacher of Reality. He also initiated the process of providing Indian form to Christian names. For instance he termed Devasahayam (helped by God) for Lazar; Rayappan (person of the rock) for Peter; Arulappan (person of grace) for John; and Chinnappan (the little one) for Paul. He pioneered the efforts to popularize Christ’s message in Tamil, Telugu and Sanskrit. He tried in vain to replace Latin in Seminary by Sanskrit.

Early on Nobili noted that the growth of the Indian Church would be stunted if it depended on foreigners for its sustenance. Therefore, it wasn’t long before he devised a bold plan to raise up hundreds of indigenous leaders.

Vincent Cronin in his book “A Pearl to India: The Life of Roberto de Nobili”, writes :

Nobili wanted to train seminarists [sic] who, having preserved their Indian customs and their castes, would be respected by their Hindu countrymen, to whom they could speak on equal terms. He wanted his future priests to present Christianity to the Indian people in their own languages, not in a jargon in which all religious terms were Portuguese; to be well trained in Christian theology but also experts in the religion of the Hindus around him; to depend for support and protection on their own countrymen, not on foreigners. In the first half of the seventeenth century such a plan was extremely bold and farsighted

He had his detractors both inside and outside the Church. But in Goa Nobili had many enemies.

Nobili, they cried, was the shame—the ineffaceable shame—of the missions; he complicated the simplicity of Christian truth, he deformed the method bequeathed by the apostles, mixing with it pagan rites and ceremonies; he was destroying the old traditions of the diocese of Goa; he was polluting the Gospel with specious emblems of caste; then, by frauds and deceits, insinuating this into the depths of men’s hearts. Instead of giving them salutary and profitable advice, with his superstitious inventions he led the credulous minds of the Hindus into error and deception; he mixed together things profane and holy, earthly and heavenly, vile and excellent.

He was on one occasion imprisoned but was saved by the timely intervention of the king of Madurai. Thereafter he was transferred from Madurai to Jaffna in Sri Lanka. As his health was deteriorating he requested the Church to send him back to his city, Madurai where he wished to spend his last days. He was however shifted to Mylapore, where he came to be called O Santho Padre (saintly priest). He had grown old, partially blind and frail but kept his austere habits and vegetarian food habits. As he grew weaker day-by-day his friends tried to administer him chicken soup as nourishment. But, De Nobili refused to take that. He insisted not merely in calling himself a Brahmin but in living like one.

Someone commented that pretension when sustained over long periods is such a dangerous game. It obliterates the thin dividing line between the reality and the world of make believe. De Nobili fasted unto death like an Indian ascetic and died on 16 Jan, 1656.There is no tomb or a memorial in his name either at Madurai, Mylapore, Jaffna or Salem.

It is rather a paradox; De Nobili maintained all his working life that religion need not be empirically connected to cultural conditions. He tried demonstrating that premise by distancing himself from polluting persons and polluting substances; and rigorously simulating the austere life of a Brahmin. But that, in effect, meant De Nobili had to enter Hindu religion through its culture. In other words, the Hindu culture was his door to the Hindu religion. In order to enter into the religious world of Brahmins he had to take recourse to their cultural practices, symbols and mode of life. That obliquely demonstrated the proximity between culture and the religion; just the point De Nobili was laboring hard to disprove. That in a way supported what his detractors were stating all along: One can not talk of religion and of God merely in terms of syllogisms but it should relate to the culture that help the religion make meaningful statements. Else, the converts might eventually abandon their cultures together with their religion.

Dr. C. Joe Arun SJ in his essay Religion as Culture: Anthropological Critique of de Nobili’s Approach to Religion and Culture says that De Nobili was not concerned with understanding different religions and cultures; his main aim was to convert as many people as possible. In doing so he needed a sound justification and therefore he artificially delinked religion from culture. Dr. Joe Arun feels that De Nobili could have entered into the world of Hindus by understanding their religion as a part of their cultural traditions and still he could have made significant progress in his mission.

***

The years following De Nobili’s death witnessed some interesting developments in the Church. In the year 1659 , three years his death, the office of Propaganda Fide echoed De Nobili by stating unequivocally that European missionaries were to take with them not ‘France, Spain or Italy, or any part of Europe’ but the Faith ‘which does not reject or damage any people’s rites and customs’. They were told “To be different does not necessarily mean opposition or contradiction”.

The Vatican had agreed to localization of several preaching methods in Eastern and African countries. It meant that message of the Gospel should be conveyed in the terms that are familiar to the people, lest they perceive Christianity as something foreign and irrelevant to their way of life. The liturgy must “think, speak, and ritualize according to the local cultural pattern.”

In India, after the death of De Nobili in 1656, many of the Jesuits continued his policy, despite objections from the other religious orders, mainly the Capuchins (the members of the Franciscan order), who were in charge of the French mission at Pondicherry.

The Jesuits, in deference to the Brahmin converts, formulated a scheme, with the approval of the Pope, for organizing two classes of missionaries, one for the Brahmins and another for the lower castes. The scheme did not however come in to being because of the combination of a number of factors such as the decline in the power of the Jesuits leading to their suppression ; the invasion of India by the Dutch; the insistence of Portugal upon its rights of patronage over all the churches of India, the downfall of the religious spirit in Europe during the eighteenth century, and finally by the destruction during the French Revolution of the colleges and religious houses that supplied workers for the mission.

Charles-Thomas Maillard de Tournon, Patriarch of Antioch, sent by Pope Clement XI, with the power of legatus a latere, to visit the new Christian missions of the East Indies issued a decree dated 23 June 1704 consisting sixteen articles concerning practices in use or supposed to be in use among the neophytes of Madura and the Carnatic. The Tournon decree condemned and prohibited Jesuits’ practices as defiling the purity of the faith and religion, and forbade the missionaries, on pain of heavy censures, to permit such practices any more.

With these measures, the distinction between Brahmin and pariah missionaries became almost extinct. But, as the conversions from the higher castes became fewer and fewer, Pope Benedict XIV, at the request of the Jesuits, consented to try a new solution to the knotty problem, by forming a band of missionaries who would attend only to the care of the pariahs. The scheme became formal through the Constitution Omnium sollicitudinum published on 12 September, 1744. The scheme however was not a great success.

The Jesuit missionaries thereafter pursued a design which Nobili had also in view, but could not carry it out. They opened their college at Triruchirapalli. That enabled Jesuits to make a wide breach into the wall of Brahminic reserve, as hundreds of Brahmins sent their sons to be taught by the Catholic missionaries. Within about a few years about fifty of those young men embraced the faith of their teachers.

****

Three centuries after the death of De Nobili, Pope John XXIII revived the issue of localization of religious practices by affixing his pontifical seal of approval to the work of pioneers like Matteo Ricci and Roberto de Nobili. In calling the Second Vatican Council in 1962, he opened the windows of the Catholic Church to let in some fresh air; which according to some conservatives led to all sorts of confusion.

His successor Pope Paul VI who presided over the remaining sessions of the Second Vatican Council, too, emphasized the importance of the dialogue with the traditional religions and their cultures. In his allocution to translators in 1965, Pope Paul VI declared that vernacular languages had become vox ecclesi, the voice of the Church (EDIL 482). Pope Paul VI is said to have remarked “A faith, which does not become a culture is a faith that has not been fully received.”

The idea that the Gospel should be preached in terms familiar to the people, lest they perceive Christianity as something foreign and irrelevant to their way of life; and that the liturgy must “think, speak, and ritualize according to the local cultural pattern” was gaining ground.

***

De Nobili was partially vindicated, though in a strange a manner. De Nobili, all his life, worked hard on the premise that culture and religion are two separate concepts and religion could be independent of the culture. That premise did not seem to find favor with the Church. However, the Church found it worthwhile to adopt and pursue his methods; that of entering a host religion through the portals of its culture. Such a process came to be known, in due course, as inculturation or enculturation.

Inculturation is the theological avatar of the anthropological term enculturation. It suggested a process by which the Gospel could be presented to a specific culture that is being evangelized. The process, in effect, meant using the culture of the host society as a door to usher in Christianity.

The term Inculturation or enculturation gained currency after Pope John Paul II officially adopted it in his 1979 Apostolic Letter Catechesi Tradendae. Since then, it has become a much discussed and a highly debated issue. Innumerable books and articles have been written on the subject. It is said that the pope meant inculturation as an ongoing dialogue between local cultures and the Christian faith. And yet, the term is not always clearly understood and each group has its own interpretation. The concept still remains rather fluid.

Inculturation or enculturation does not mean amalgamation or coming together of the two cultures. Neither the Church nor the host culture is changed. The host culture is not condemned, nor is it required to be phased out in order for the people to enter the Church. Thus, inculturation, in effect, became an arrangement under which, the convert accepts the theology of the church and the person of Jesus, while the Church does not question his culture and its practices.

Inculturation focuses on the local situation; and it cannot take place until the “other” culture is understood. It tries to re-express the Gospel, using the host culture’s own value. But the problem in older societies like in India is that it is not easy to demarcate the boundaries of its culture; because its cultures and religions run into each other. Culture of the people in India is not confined to their dress, their food or their artistic expressions. Their Culture embraces the whole human reality. It includes language, thought, the entire symbolic system and especially the idioms of religious expressions. It is not easyto isolate cultural elements, customs etc. and Christianize them. Therefore, when the Church accepts the culture of its converts, it accepts a part of their religion too. That by implication means the other religions are not devilish any more.

Interestingly, the decree Nostra Aetate (meaning In our Time ), the declaration on the relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions , promulgated on Oct 28 , 1965 in affirmation of the Second Vatican Council had earlier stated, ” The Catholic Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in these religions. She regards with sincere reverence those ways of conduct and of life, those precepts and teachings which, though differing in many aspects from the ones she holds and sets forth, nonetheless often reflect a ray of that Truth which enlightens all men. ” It also spawns the idea of nurturing the “seeds of truth” present in other religions – in other words, to help the Hindu be a good Hindu or help the Muslim worship his one God – as if those seeds were themselves distinct ways of salvation, independent of Christ and even more independent of the Church. It is said the proposal was approved with an overwhelming majority of 2,221 to 88.

That put Evangelism and missionary activities of the Church in a totally different light. Conversion has always been an irritant in multi-religious countries. It involves convincing people that their religion is wrong or inadequate; and ultimately persuading them, by whatever means, to convert to the new religion. The Church, it seemed, was wary of taking that approach.

Now, once the elements of Salvation and doctrinal superiority are taken out of the equation, the conversions lose their religious significance; and are no longer religious phenomena. Perhaps the only significance they might be left with, in a multi-religious society like India, is the creation of social groups which might have the potential of turning in to vote –banks.

But, at the same time, the Church is missionary by her very nature; and every Christian is a missionary. The Church believes that its existence and growth depends on the mission carried out by its faithful. Conversions are the lifeblood of the Church. What purpose will it serve the Church if it merely carries on socio-political debates without gaining converts? The Church cannot obviously give up its missionary activities. Or does it mean the Church prefers to build the fold where the sheep are, instead of going after the sheep to bring them in to the fold ¿.There appears to be some confused or covert thinking here.

****

Many traditional and conservative Catholics within the Church were therefore not comfortable with the interpretation and the implementation of the inculturation; and they feared, the Church runs the risk of self-contradictions. Further, they pointed out, the more one suppresses or modifies the language and the rites of the Bible on cultural grounds, the more one trivializes its culture. The same argument could be applied to the liturgy and other cultural expressions of the Church. They insisted that Gospel message should not be isolated from the culture in which it was first inserted; and the unity of the Roman rite and a universal Christian vocabulary must be maintained. They argued that the changes in the liturgy should be made “only when the good of the church genuinely and certainly requires them” and not as a matter of routine.

They also pointed out a paradox in the situation. They said if you accept that inculturation expresses the mystery of Christ in a better way, it might then mean that such cultures complement something that is lacking in the Gospel. Would it not suggest that Gospel by itself is somewhat inadequate? Thus the consequences and implications of inculturation are unpredictable; and the Church better be weary of thatprocess.

***

Despite such criticisms, the contemporary evangelization lays emphasis on the importance of enculturation, with encouragement from Rome. The supporters of inculturation argue it is not always easy to distinguish between faith and culture, between values and counter- values. Finding solutions is often arduous. Inculturation, they insist, is a marvelous and mysterious exchange of gifts: “In one direction, the Gospel reveals to each culture the supreme truth of the values that the culture embodies and allows the culture to unleash that truth; in the other, each culture expresses the Gospel in an original way and reveals new aspects of it.”

But somewhere along the line the process seems to have gone overboard. While the Second Vatican Council, especially Gaudium et Spes, stressed the priority of the Faith over culture, some recent developments in India seem to suggest that evangelists regard culture as the ultimate source and norm of faith.

I understand that the Church has so far approved for India a program for Inculturation in about 168 dioceses; and about 45 churches have been fully incultured. Today , the methods innovated by De Nobili are being employed quiet brilliantly by some christian missions. The Inculturation in the Indian context involves providing a Hindu orientation to the lay out, structures and interiors, furniture and religious fixtures of a church. Some of them have been refurbished and redesigned to include murals, panels, furniture et al inspired by Hindu symbols.

In some instances the image of Jesus too is depicted in Hindu style: as in the case of Jesus sitting cross-legged on a lotus (installed in a church in Hyderabad), or Jesus emerging after a purifying bath in the Ganges with temples on the riverbanks (in a mural in a Hardwar church). At a church in Nadia, Jesus looks like Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, the 15th century Vaishna saint of Bengal, his arms raised in a beatific trance. At a church in Jhansi, scenes from Christ’s life, in a set of 40 paintings, mare depicted in Indian forms. At a seminary near Shillong Jesus is shown standing under a pine tree with people in Khasi and Garo headgear around him. At Ambapara, Jesus is shown as a Bhil tribal.

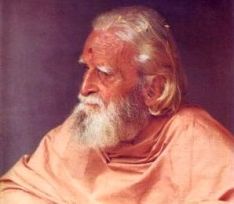

The robes of the missionaries (with saffron tinge) and in some cases even the names (such as Swami Abishiktananda etc.) have been given a Hindu orientation. . The Seminaries or Churches in many cases are called Ashrams, and resemble Hindu temples in appearance.

One of such churches was built by Bede Griffith built in Tiruchirapalli District of Tamil Nadu. It is named Sachidananda Ashramam. The gateway to the Ashram, in Hindu style, depicts God the Father as masculine, an androgynous image representing Jesus and a feminine face suggesting the Holy Spirit. The Vimana, or colorful cupola, above the temple’s sanctum, constructed in traditional style using symbolism from the Bible; and also the lotus and the symbols of the five elements, depict Christ seated in various yoga postures. His saints too adore the Vimana. The sanctum itself is built like a Garbhagriha, dark and mysterious. Jesus sits in side the sanctum on a Lotus, like a yogi. Four adjoined statues face the four cardinal directions sitting knee-to-knee in the classic lotus posture. They are situated in a large black lotus, and even Jesus is black. The monks in saffron robes begin every prayer with the sacred Sanskrit syllable Om.

The worship rituals are conducted in Hindu style with waving of Arati, burning incense and flower decorations. Chanting of mantras of Jesus in Indian style and meditations are also carried out. There is an admixture of religious symbols, bordering on syncretism. Bede Griffith himself was attired as a Hindu monk in saffron robes. Sachidananda Ashramam might look like a bridge between the Christian faith and Hinduism; yet, to many it seems to reflect an unresolved problem within Catholicism.

The other methods of inculturation or Indiazitation include not merely equating Madonna with Mother Goddess Devi; Virgin Mary with Kanya Kumari; and Infant Jesus with child Krishna, but also depicting them as such. Sometimes, it is suggested that Jesus spent his youth in India mastering forms of Yoga or that Jesus is one among the Avatars. The Sanskrit texts are interpreted to suggest that the terms such as Isa, Ishwara and Parameswara referred to Jesus in the first place; and that Prajapati is really Jehovah.

There may not be much substance in such portrayals. But they do help in melting down the natural barriers and resistance to an alien God from an alien culture; and renders it easier for the Hindus to accept the icons of Christianity as their own.

***

Recently the Church in Kerala brought an ‘Indianised’ Bible with references to the Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita, Manusmriti and drawings of a turbaned Joseph and sari clad Mother Mary with baby Jesus in her arms. The Catholic Church’s spokesperson Father Paul Thelekat described it as an attempt to make contextual reading and understanding. Over such 70 references to non Christian texts have been made in the Bible and 30 scholars participated in making the commentary, Fr Thelekat said.

The new Indian Bible has also references to Meerabai, Mahatma Gandhi, and Rabindranath Tagore in the interpretations of biblical passages.

“An attempt has been made to give a Bible which is more relevant for India. There is nothing added or subtracted from the text of the Bible, which has been reproduced as such”.

Thelekat said while interpreting Treasure in Heaven of Mt 6:19.21 said …’this concept is found a classical expression in the Bhagavad Gita’s call to disinterested action: ‘Work alone is your proper business never the fruits it may produce” (2:47), or while commenting on the third appearance of Jesus to disciples (John 21:1.14)… ‘The Lord ever stands on the shores of our life every moment and every age, every day and every night he comes, comes, ever comes’ (Gitanjali XLV

The deluge story of the Book of Genesis is interpreted with reference of such stories in Mesopotamia and Satapath Brahmana (1.8.1-10) and Mahabharata.

http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/msid-3328291,prtpage-1.cms

Please also check William Dalrymple’ article Sisters Of Mannarkad: In this pocket of Kerala, local myth fuses Goddess Bhagavati and Mother Mary into family.

The culture in Indian society is centred on the family traditions; similar is the case with the Indian Christian communities too. They have learnt to make adjustments and to work out a way of life and a way of response to the Gospel. For instance, each community has a way of celebrating a wedding. When a family turns Christian it does not abandon its traditional customs; instead, it adds on a new ritual, the Christian ritual. They keep their socio cultural customs, but add on a prayer or a symbolic action to Christianize the celebration. An inter-cultural encounter thus becomes an inter-religious encounter too.

The social status of a convert is not greatly altered; he might sometimes fall in to a different sub-category. For instance a dalit converted to Christianity is labelled a dalit Christian. He continues to follow, mainly, his family traditions and life-cycle rituals.

There are innumerable Hindus who accept Jesus Christ and follow his teachings without converting to Christian religion. There are also those who refused to join the Church officially or those that adopted an independent way of life even after baptism, like Brahmabandab Upadyayaya, Nehemiah Gorey, Manilal Parekh and Pandita Ramabhai et al.

Even among ordinary Hindus, that is at the level of people who are not regarded intellectuals, one can notice their acceptance of Christ; but in their own way. For instance, the shrine of Infant Jesus in Bangalore, especially on Thursdays, is thronged by Hindu worshippers and quite a number of them come from upper castes and Brahmin families. Their acceptance of Jesus is a matter of simple faith, an answer to their prayers. It is a direct communion between the worshipper and Jesus; and it involve neither the Church nor its doctrines.

There are other cases where Christian at some stage of his/her life discovers that s/he is heir to two religious traditions feeling that s/he is Hindu-Christian, Buddhist-Christian, etc. They seek to integrate both, with a fair amount of success. Such cases do not involve interaction with other cultures; they are inter – religious encounters. Therefore, perhaps to guard against the dangers of “reverse-inculturation”, the Church banned Yoga and other non-religious practices in the Church premises.

Inculturation has thus traversed a full circle since the time of Roberto De Nobili to the present day.

All these, bring us back to the question we started with: what is a proper way of understanding conversion and its need in a multi-cultural and multi – religious society in India, given the inculturation phenomenon.

******

Resources

History of the missions by Bernard de vaulx

History of the Catholic Church from the Renaissance to the French Revolution by Rev. James MacCaffrey

inculturation by Eugene Lapointe

Religion as Culture: Anthropological Critique of de Nobili’s Approach to Religion and Culture byDr.C. Joe Arun SJ

Malabar Rites

Roman Catholic Brahmin! By Jyotsna Kamat

The Challenges of Gospel-Culture Encounter by Fr. Michael Amaladoss, S.J.

Dialogue in a New Key by Fr. Michael Amaladoss, S.J.

Who was Roberto de Nobili?

‘Om Namah Jesus’

All illustrations are from internet