Lakshana-granthas – texts concerning the Performing Arts of India

Some time back – as a part of the series on the Music of India – I had posted brief profiles of some of the well known texts on Samgita-shastra (Musicology), which established a sound theoretical basis (Lakshana) for the structural framework of the classical Music traditions; and, their practice (Lakshya). Those texts, produced over a long period of time, described, in precise terms, the concepts of Music; its concerns; how it should be taught, learnt and performed; and, how it should be experienced and enjoyed. It was an evolutionary process cascading towards greater sophistication.

Those Lakshana-granthas projected their vision of how the Music should develop and prosper in future, at the same time taking care to ensure retaining the pristine purity of the time-honored tradition. In the process, those texts, produced over the centuries, defined and protected the principles; as also, guided and regulated the performance of the chaste Music of India.

Some friends and readers inquired whether I could write, on similar lines, about the texts concerning the evolution of the principles and techniques of the performing arts of India; and, particularly , about Dance , which is the most enchanting form of them all; rich in elegance and beauty ; comprehensive; and highly challenging.

Various thinkers and writers of the Lakshana granthas, over a long period, have put forward several theories based on their concept of the essential core, the heart or the soul of the art of Dance (Natyasya Atma).

In the series of articles that are to follow, I have attempted to trace the unfolding of the principles and practice of the performing arts of India, as discussed in various texts spread over several centuries.

In the present installment of the series, let’s take an overview of the texts of the Indian Dancing traditions. In the subsequent parts, we may discuss each of the selected texts, in fair detail.

This may also be treated as a sort of General Introduction to the theories of Indian Dancing.

The Natyashastra

It is customary to commence with Natyashastra, when it comes to any discussion related to the art-forms of India. To start with, we shall, briefly, talk about the text of the Natyashastra, in general; and, then move on to Natyashastra in the context of Dance.

The Natyashastra of Bharata is regarded as the seminal and the earliest text extant text, represents the first stage of Indian arts where the diverse elements of arts, literature, music, dance, stage management and cosmetics etc., combined harmoniously in order to produce an enjoyable play. It is the source book for all art forms of India. The Nāṭyaśāstra, surely, is a work of great antiquity. Yet; the scholars opine that looking at the way the text has been compiled and structured; it appears to be based on earlier works.

It is said that the text which we know as Natya-Shastra was based on an earlier text that was much larger. That seems very likely; because, the Natyasastra, as we know, which has about 6,000 karikas (verses), is also known as Sat-sahasri. The later authors and commentators (Dhanika, Abhinavagupta and Sarada-tanaya) refer to the text as Sat-sahari; and, its author as Sat-sahasri-kara. But, the text having 6,000 verses is said to be a condensed version of an earlier and larger text having about 12,000 verses (dwadasha-sahasri). It is said; the larger version was known as Natya- agama and the shorter as Natya-shastra.

*

And, again, According to Prof. KM Varma, there were three types of works which preceded the Natyashastra that we know:

- (1) Sutra – a work on Natya;

- (2) Bhashya – a commentary on it; and

- (3) Anuvamsya – a collection of verses , from which Bharata often quotes.

He also points out that Bharata mentions in the Samgraha (the table of contents to Natyashastra) that the subjects to be discussed in the text have reference to what is stated in the Sutra and the Bhashya. That leads to the conclusion that a comprehensive theory of Natya existed much before the time of Bharata; and that he incorporated some of that into his work – the Natyashastra.

*

Further, from what Panini suggests, it appears there were texts on Natya even prior to his time; which means such texts were in existence much before the Natyashastra.

Panini (Ca.500 BCE) the great Grammarian, in his Astadhyayi (4.3.110-11), mentions two ancient Schools – of Krsava and Silalin – that were in existence during his time

–Parasarya Silalibhyam bhikshu nata-sutreyoh (4.3.110); karmanda krushas shvadinihi (4.3.111).

It appears that Parasara, Silalin, karmanda and Krsava were the authors of Bhikshu Sutras and Nata Sutras. Of these, Silalin and Krsava were said to have prepared the Sutras (codes) for the Nata (actors or dancers).

At times, Natyashastra refers to the performers (Nata) as Sailalaka-s. The assumption is that the Silalin-school, at one time, might have been a prominent theatrical tradition. Some scholars opine that the Nata-sutras of Silalin (coming under the Amnaya tradition) might have influenced the preliminary part (Purvanga) of the Natyashastra, with its elements of worship (Puja).

However, in the preface to his great work Natya-shastra of Bharatamuni (Volume I, Second Edition, 1956) Pundit M. Ramakrishna Kavi mentions that in the Natyavarga of Amara-kosha (2.8.1419-20) there is reference to three schools of Nata-sutra-kara: Silalin; Krasava; and, Bharata.

Śailālinas tu śailūṣā jāyājīvāḥ kṛśāśvinaḥ bharatā ityapi naṭāś cāraṇās tu kuśīlavāḥ

It appears that in the later times, the former two Schools (Silali and Krasava) , which flourished earlier to Bharata , went out of existence or merged with the School of Bharata; and, nothing much has come down to us about these older Schools. And, it is also said, the Bharata himself was preceded by Adi-Bharata, the originator and Vriddha (senior) Bharata. And, all the actors, of whatever earlier Schools, later came to be known as Bharata-s.

All these suggest that there were texts on Natya even before the time of Bharata; and, by his time Natya was already a well established Art.

[The ancient texts such as Ramayana, Mahabharata and Satapatha Brahmana, use the term Śailūṣa (शैलूष) – (śilūṣasya apatyam) to refer to an actor, dancer or a performer

– avāpya śailūṣa ivaiṣa bhūmikām (अवाप्य शैलूष इवैष भूमिकाम्)]

*

The Natyasastra, that we know, is dated around about the second century BCE . The scholars surmise that the text was in circulation for a very long period of time, in its oral form; and, it was reduced to writing several centuries after it was articulated. Until then, the text was preserved and transmitted in oral form.

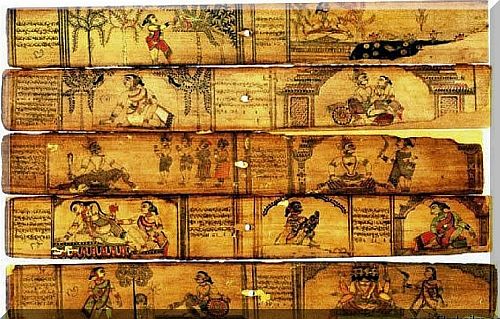

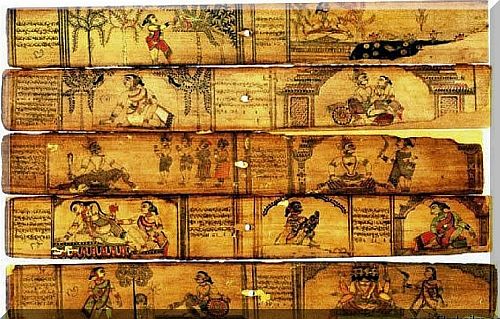

The written text facilitated its reach to different parts of the country; and, to the neighboring states as well. In the process, each region, where the text became popular, produced its own version of Natyasastra; in its own script.

For instance, Natyasastra spread to Nepal, Almora to Ujjain, Darbhanga and also to the Southern states. The earliest known manuscripts which come from Nepal were in Newari script. The text also became available in many other scripts – Devanagari, Grantha, and several regional languages. It became rather difficult for the later-day scholars, to evolve criteria for determining the authenticity and purity of the text, particularly with grammatical mistakes and scribes errors that crept in during the protracted process of transliterations.

Therefore, written texts as they have come down to us through manuscripts , merely represent the residual record or an approximation to the original; but, not the exact communication of the oral tradition that originated from Bharata.

It is the general contention that the text of the Natyashastra, as it is available today, was not written at one point of time. Its form, as it has come down to us, includes several additions and alterations. It is also said; many views presented in Natya-Shastra might possibly have been adopted from the works of other scholars. That seems quite likely; because, there are frequent references to other writers and other views; there are repetitions; there are contradictory passages; there are technical terms, which are not supported by the tradition.

And, in regard to Dance, in particular, the Chapter Four (Tandava-lakshanam) is the most important portion, as it details the dance-techniques. The editor of Nāṭya Śāstra, Sri. Ramaswami Sastri, however remarks that ‘this section of Nāṭya Śāstra dealing with Karaṇas, being of a highly technical nature, was less understood and was rendered more difficult by numerous errors committed by the scribes as well as by the omissions of large portions in the manuscripts’.

Though such additions, deletions and alterations have not been pinpointed precisely, some scholars, particularly Prof. KM Varma, surmise that the verses of a long portion of the Fourth Chapter beginning from Sloka number 274 and ending with the chapter seem to be interpolated. These verses do not also fit into the context. Abhinavagupta also admits the possibility of their insertions.

Further, Prof. KM Varma also mentions that the portion from the Samanya-abhinaya chapter (Chapter 22) to the beginning of the chapter on Siddhi; as also the portions beginning after the chapter on Avanaddha to the end of the present text, are the later additions.

And, by about the tenth century, two recessions of the Nāṭyaśāstra were in circulation. One was the longer version; and, the other the shorter. There have been long drawn out debates arguing which of the two is the authentic version. Abhinavagupta in his commentary of the Nāṭyaśāstra used the shorter recession as the basis of his work; while some authors of the medieval period like Raja Bhoja used the longer version.

However, Pandit Ramakrishna Kavi, who examined as many as about forty Manuscripts of the text, opined that the longer recession seemed to be ancient, although it contains some interpolation. But, in any case, now, both the versions are treated as ‘authentic’; and, are used depending upon the choice of the commentator.

( For a note on the Life and Works of Manavalli Ramakrishna Kavi, please click here.)

Natyashastra in the context of Dance

Natyashastra was mainly concerned with successful play-production. And, the role of Music and Dance, in conjunction with other components, was primarily to beautify and to heighten the dramatic effects of the acts and scenes in the play. These were treated as enchanting artistic devices that articulate the moods of various theatrical situations in the Drama. The Dance, at that stage, was an ancillary part (Anga) or one of the ingredients that lent elegance and grace to theatrical performance. That is to say; though Music and Dance were very essential to Drama, neither of the two, at that stage, was considered as an independent Art-form.

Further, for a considerable length of time, say up to the middle period, both music and dance were covered by a single term Samgita. The term Samgita in the early Indian context meant a composite art-form comprising Gita (vocal singing), Vadya (instrumental accompaniments) and Nrtta the limb movement or dance (Gitam, Vadyam, Nrttam Samgita-mucchyate). The third component of Samgita, viz., Nrtta, involved the use of other two components (Gita and Vadya).

Thus, the term Samgita combined in itself all the different phases of music, including dance. For Dance (Nrtta), just as in the case of vocal (Gita) and instrumental (Vadya) music, the rhythm (Laya) is very vital. The Dance too was regarded as a kind of music. This is analogous to human body where its different limbs function in harmony with the body’s rhythm.

It was said; all the three elements should, ideally, coordinate and perform harmoniously – supporting and strengthening each other with great relish. And, the three Kutapa-s, in combination should suggest a seamless movement like a circle of fire (Alaata chakra); and, should brighten (Ujjvalayati) the stage.

Thus, till about the middle periods, Dance was regarded as a supporting decorative factor; but, not an independent Art form.

Coming back to Natyashastra, the Dance that it deals in fair detail is, indeed, Nrtta, the pure dance movements – with its Tandava and Sukumara variations – that carry no particular meaning. The Nrtta was described as pure dancing or limb movements (aṅgavikṣepa), not associated with any particular emotion, Bhava. And, it was performed during the preliminaries (Purvaranga), before the commencement of the play proper. The Nrtta was meant as a praise offering (Deva-stuti) to the gods.

And, later Bharata did try to combine the pure dance movements of Nrtta (involving poses, gestures, foot-work etc.) with Abhinaya (lit., to bring near, to present before the eyes), to create an expressive dance-form that was adorned with elegant, evocative and graceful body-movements, performed in unison with attractive rhythm and enthralling music, in order to effectively interpret and illustrate the lyrics of a song; and, also to depict the emotional content of a dramatic sequence.

But, for some reason, Bharata did not see the need to assign a name or a title to this newly created amalgam of Nrtta and Abhinaya. (This art-form in the later period came to be celebrated as Nrtya).

Even at this stage, Dance was not an independent art-form; and, it continued to be treated as one of the beautifying factors of the Drama.

Bharata had not discussed, in detail, about Dance; nor had he put forward any theories to explain his concepts about Dance. The reason for that might be, as the scholars explain, Bharata had left that task to his disciple Kohala; asking him to come up with a treatise on dancing, explaining whatever details he could not mention in the Natyashastra. In fact, Bharata, towards the end of his work says: ‘the rest will be done by Kohala through a supplementary treatise’

– śeṣam-uttara-tantreṇa kohalastu kariṣyati – (NS.37.18.)

But, unfortunately, that work of Kohala did not survive for long. And, by the time of Abhinavagupta (10-11th century), it was already lost.

Texts concerning dance

When it comes to the texts concerning dance , there are certain issues or limiting factors.

There is reason to believe that many works on dancing were written during the period following that of Bharata. But most of those works were lost.

For instance; the ancient writers such as Dattila or Dantila (perhaps belonging to the period just after that of Bharata) and Matanga or Matanga Muni (sixth or the seventh century) who wrote authoritatively on Music, it appears, had also commented on Dance. But again, the verses pertaining to Dance in their works, have not come down to us entirely. Some of those verses have survived as fragments quoted by the commentators of the later periods; say , for example, the references pertaining to Taala and Dance from the Brihaddeshi of Matanga .

Similarly, between the time of Natyashastra (Ca. 200 BCE) and the Abhinavabharati of Abhinavagupta (10-11th century), several commentaries were said to have been produced on the subject of Drama, Music, Dance and related subjects. Some of such ancient authorities mentioned by Abhinavagupta are:

Kohala, Nandi, Rahula, Dattila, Narada, Matanga, Shandilya, Kirtidhara, Matrigupta, Udbhata, Sri Sanuka, Lottata, Bhattanayaka and his Guru Bhatta Tauta and others.

But, sadly the works of those Masters are lost to us; and, they survive in fragments as cited by the later authors.

Abhinavagupta, states that much of the older traditions had faded out of practice. And he says that one of the reasons, which prompted him to write his work, was to save the tradition from further erosion.

Texts on Music etc., which also dealt with Dance

There are not many ancient texts that are particularly devoted to discussions on Dance, its theories and techniques.

In the earlier texts on Dance, the techniques of Dancing are seldom discussed in isolation. It invariably is discussed along with music and literature (Kavya). Similarly, the treatise on sculpture (Shilpa) , Drama(Natya), music (Gitam) and painting (Chitra) , do devote a portion , either to Dance itself or to discuss certain technical elements of these art forms in terms of the technique of Dance (Nrtya or Nrtta).

For instance; the treatises on painting discuss the Rasa-drsti in terms of the glances (Drsti) of the Natyashastra; and, the treatises on sculpture enumerate in great detail the Nrtta-murti (dancing aspects) of the various gods and goddesses(prathima-lakshanam) , and discuss the symbolism of the hasta-mudra in terms of the hasta-abhinaya of the Natyashastra.

The Vishnudharmottara emphasizes the inter relation between the various art forms. Sage Markandeya instructs :

One who does not know the laws of painting (Chitra) can never understand the laws of image-making (Shilpa); and, it is difficult to understand the laws of painting (Chitra) without any knowledge of the technique of dancing (Nrtya); and, that, in turn, is difficult to understand without a thorough knowledge of the laws of instrumental music (vadya); But, the laws of instrumental music cannot be learnt without a deep knowledge of the art of vocal music (gana).

*

Therefore, most of the texts and treatise which dealt with Music, primarily, also talked about dance, in comparatively briefly manner, towards the end. For instance:

[Here, in this portion, I have followed Dr. Mandakranta Bose, as in her very well researched paper (The Evolution of Classical Indian Dance Literature: A Study of the Sanskritic Tradition ) . I gratefully acknowledge her help and guidance.]

(1) Visnudharmottara Purana (Ca. fifth or sixth century) a text encyclopedic in nature. Apart from painting, image-making, Dancing and dramaturgy, it also deals with varied subjects such as astronomy, astrology, politics, war strategies, treatment of diseases etc. The text, which is divided into three khandas (parts), has in all 570 Adhyayas (chapters). It deals with dance, in its third segment – chapters twenty to thirty-four.

The author follows the Natyasastra in describing the abstract dance form, Nrtta; and, in defining its function as one of beautifying a dramatic presentation. The focus of the text is on Nrtta, defining its vital elements such as Karanas, Cari etc., required in dancing. In addition, the author briefly touches upon the Pindibandhas or group dances mentioned by Bharata; and, goes on to describe Vrtti, Pravrtti and Siddhi; that is – the style, the means of application and the nature of competence.

*

(2) The Abhinavabharati of Abhinavagupta (11th century) though famed as a commentary on Bharata’s Natyasastra, is, for all purposes, an independent treatise on aesthetics in Indian dance, music, poetry, poetics (alaṅkāra-śhāstra), art , Tantra, Pratyabhijnana School of Shaiva Siddanta etc. Abhinavabharati is considered a landmark work; and is regarded important for the study of Natyasastra.

Abhinavabharati is the oldest commentary available on Natyasastra. All the other previous commentaries are now totally lost. The fact such commentaries once existed came to light only because Abhinavagupta referred to them in his work; and, discussed their views. Further, Abhinavagupta also brought to light and breathed life into ancient and forgotten scholarship of fine rhetoricians Bhamaha, Dandin and Rajashekhara.

Abhinavagupta also drew upon the later authors to explain the application of the rules and principles of Dance. As Prof. Mandakranta Bose observes : One of the most illuminating features of Abhinavagupta’s work is his practice of citing and drawing upon the older authorities critically , presenting their views to elucidate Bharata’s views ; and , often rejecting their views , putting forth his own observations to provide evidence to the contrary.

Abhinavagupta, thus, not only expands on Bharata’s cryptic statements and concepts; but also interprets them in the light of his own experience and knowledge, in the context of the contemporary practices. And, therefore, the importance of Abhinavagupta’s work can hardly be overstated.

He also discusses, in detail, the Rasa-sutra of Bharata in the light of theories Dhvani (aesthetic suggestion) and Abhivyakti (expression). And, Dance is one of the subjects that Abhinavabharati deals with. As regards Dance, Abhinavabharati is particularly known for the explanations it offers on Angikabhinaya and Karanas. The later authors and commentators followed the lead given by Abhinavagupta.

*

(3) The Dasarupaka of Dhananjaya (10-11th century), is a work on dramaturgy; and, basically is a summary or compilation of rules concerning Drama (Rupaka), extracted from the Natyashastra of Bharata. As regards Dance, Dhananjaya, in Book One of his work, which provides lists of definitions, mentions the broad categories of Dance-forms as: the Marga (the pure or pristine); and, the Desi (the regional or improvised). And, under each class, he makes a two-fold division: Lasya, the graceful, gentle and fluid pleasing dance; and, Tandava, the vigorous, energetic and brisk invigorating movements (lasya-tandava-rupena natakad-dyupakarakam) . The rest of his work is devoted to discussion on ten forms of Drama (Dasarupaka)

*

(4) The Srngaraprakasa of Raja Bhoja (10-11th century) is again a work; spread over thirty-six chapters, which deal principally with poetics (Alamkara shastra) and dramaturgy. In so far as Dance is concerned, it is relevant for the discussion carried out in its Eleventh Chapter on minor types of plays (Uparupakas) or musical Dance-dramas.

(5) The Natya-darpana of Ramacandra and Gunacandra (twelfth century) is also a treatise, having four chapters, devoted mainly to dramaturgy; discussing characteristics of Drama.

The Natyadarpana by Ramachandra and Gunachandra, two Jain authors, is an important work in the field of Sanskrit dramaturgy, the science of Drama. The text presents a clear picture of the chief principles of dramaturgy, its critical points and problems.

The Natyadarpana is composed in two segments: (1) Karika-s (verses); and, (2) Vritti-s (prose).

(1) The Karika-s, in the form of Sutras set to Anustubh Chhandas; give an outline of the topics to be dealt with in the text; and, also define the important principles in a nutshell.

The Karika-s, 207 in number, are spread over Four Chapters (Viveka-s).

The First Chapter, titled Nataka-nirnaya, discusses the nature and the form of Nataka, the most important form of Drama (Rupaka). It enumerates and defines the structures of the Nataka: Plot (Vastu); the five stages (Avastha) of its depiction: Arambha, Yatna, Praptyasa, Niyatapti and Phalagama. It also details the five alternate stages of plot development – Arthaprakrti (Bija, Bindu etc).Then; it goes on to mention the five junctures – Sandhi-s (Mukha, Prathimukha, Garbha, Avamarsa and Nirvahana); five Arthopakshepa-s; ( five ways of suggesting to the spectators the scenes and incidents yet to come); and 64 Sandhyanga elements.

The Second Chapter Prakarana-adya-ekadasa-rupa-nirnaya) discusses the nature and structure of other types of Dramas (Rupakas): Prakarana, Vyayoga, Samavakara, Bhana, Prahasana, Dhima, Utsrstikanka, Ihamrga, and Vithi. In addition, it also discusses the other minor forms of Drama: the Natika and Praranika. Thus, the forms of Drama mentioned here are twelve (as compared to ten enumerated by Dhananjaya).

The Third Chapter (Vrtti-Rasa-Bhava-Abhinaya-Vicara) discusses the details of Theatrical presentations; such as: styles of acting and speaking; portrayal of sentiments; exhibiting the states of being; and, gesticulations (Abhinaya).

The Fourth Chapter (Sarva-Rupaka-Sadharana-Lakshana-Nirnaya) covers general topics and miscellaneous elements of a Theatrical production. These cover topics that are common to all the twelve types of Dramas. These cover issues such as : the desired qualities of the hero and heroine ( of all types) and other characters ; the rules regarding the language and dialogue delivery suitable to each type of character; and the , details of the preliminaries , such as Naandi ( prayers) , Prarochana ( introductions) etc.

*

(2) The Vrtti-s (or the Gloss) commenting, in detail, on the subjects briefly covered in the Karika-s, form the most important part of the Text. Apart from commenting on the various issues covered by the Karika-s, the authors also provide the views of other theoreticians, along with illustrations, examples etc. Here, they often criticize the opposing views,

Of the Four Chapters (Viveka-s), the commentary on the First is most elaborate; and, it forms almost half the size of the whole text.

*

The text is useful to Dance, because in its third chapter while discussing Anigikabhinaya, it lists the names of the movements of the different parts of the body, as well as extended sequences and compositions. The text enumerates 13 types of head movements(Shiro-bedha); 36 types of eye-glances (Dristi-bedha); 7 types of eye-brow movements; many types of eye-lid movements; 6 types of nose –movements; 6 types of cheek movements; 6 types of movements of the lower-lip; many types of chin-movements; and nine types of neck-movements.

(6) Another text of great interest from the twelfth century is the Manasollasa ( also called Abhjilashitarta Chintamani) ascribed to the Kalyana Chalukya King Someshwara III (1127-1139 AD). It is an encyclopedic work, divided into one hundred chapters, clustered under five sections, covering a wide variety of subjects, ranging from the means of acquiring a kingdom, methods of establishing it, to medicine, magic, veterinary science, valuation of precious stones, fortifications, painting , art, games , amusements , culinary art and so on .

As regards Dance, the Manasollasa deals with the subject in the sixteenth chapter, having in 457 verses, titled Nrtya-vinoda, coming under the Fourth Section of the text – the Vinoda vimsathi- dealing with types of amusements.

Manasollasa is also the earliest extant work having a thorough and sustained discussion on dancing. It is also the earliest work, which laid emphasis on the Desi aspect for which later writers on this subject are indebted. Another important contribution of Nrtya Vinoda is that it serves as a source material for reconstruction of the dance styles that were prevalent in medieval India. For these and other reasons, the Nrtya Vinoda of Manasollasa, occupies a significant place in the body of dance literature.

Someshwara introduces the subject of dancing by saying that dances should be performed at every festive occasion, to celebrate conquests, success in competitions and examinations as well as occasions of joy, passion, pleasure and renouncement. He names six varieties of dancing and six types of Nartakas. The term Nartaka, here, stands for performers in general; and, includes Nartaki (danseuse), Nata (actor), Nartaka (dancer), Vaitalika (bard), Carana (wandering performer) and kollatika (acrobat).

Manasollasa is also significant to the theory of Dance, because it classified the whole of dancing into two major classes: the Marga (that which adheres to codified rules) and Desi (types of unregulated dance forms with their regional variations). Manasollasa also introduced four-fold categories of dance forms: Nrtya, Lasya, Marga and Desi.

At another place, Someshwara uses the term Nartana to denote Dancing, in general, covering six types: Natya (dance), Lasya (delicate), Tandava (vigorous), Visama (acrobatic), Vikata (comical) and Laghu (light and graceful).

The other authors, such as Sarangadeva, Pundarika Vittala and others followed the classifications given Manasollasa.

In regard to Dance-movements, Someshwara classifies them into six Angas, eight Upangas and six Pratyangas. The last mentioned sub-division viz. Pratyanga is an introduction made by Someshwara into Natya terminology; the Natyashastra had not mentioned this minor sub-category.

The other important contribution of Someshwara is the introduction of eighteen Desi karanas, (dance poses) that were not mentioned in other texts.

*

(7) A work from this period, but not dated with certainty, which deal with drama is the Nataka-laksana-ratna-kosa of Sagaranandin. The text, as the name suggests, discusses, in detail, the nature and characteristics of Nataka as well as other varieties of drama. This work is of interest to Dance insofar as it lists and describes ten types of Lasyanga that are used in the Lasya variety of dance.

*

(8) The Bhavaprakasana of Saradatanaya (1175 -1250 A.D.) containing ten Adhikaras or chapters, is a compendium of poetics and dramaturgy based on the critical works written right from the period of Natyashastra. Its relevance to dance is in its discussions on glances that express Bhavas, as given at the end of the fifth chapter. And, the tenth and final chapter explains the distinction between Nrtta and Nrtya; and, between Marga and Desi.

He contradicts Dhananjaya; and, asserts that Nrtta, the pure dance, is rooted in Rasa (Nrttam rasa-ahrayam). Saradatanaya’s definition meant that Nrtta not only beautifies a presentation, but is also capable of generating Rasa. This, during his time, was, indeed, a novel view.

*

(9) The Sangita Samayasara of Parsvadeva ( a Jain Acharya of 12th or early 13thcentury) is an important work, which is devoted to musicology. It is its seventh chapter that is of interest to Dance. It is not until the Sangita Samayasara that we find any description of a complete dance.

The Sangita Samayasara, though it deals, mainly, with Music, is of great relevance to Dance. The Seventh Chapter is devoted entirely to Desi dance (referred to as Nrtta); its definition; and, the Angas or body movements (Angika), the features of Desi dances (Desiya-Angani).

This text not only describes specific Nrtta dance pieces (such as: Perana, Pekkhana, Gundali and Dandarasa), but also adds a number of new movements of the Cari, the Sthanas and the Karanas of the Desi variety, all of which involving complicated leaping movements. Here, Parsvadeva describes the utplatti-karanas, needed for the Desi dances; eleven Desi karanas with different Desi-sthanas; and, five Bhramaris.

Towards the end of the Seventh Chapter, Parsvadeva describes the requirements of a good dancer; her physical appearance; and, the way she should be dressed etc.

(10) By about the 13th century, dance had gained its own existence; and, was no longer an ancillary to drama, as it was during the time of Natyashastra. The concept of Nrtta was still present; Nritya as a delightful art form was fully established; and, the two forms retained their individual identity. And, both were discussed along with Natya. This is reflected in the appearance of numerous works on the art of Music, Dance and Drama, the most significant of which was the Samgita Ratnakara of Sarangadeva

The Sarangadeva’s Sangita-ratnakara (first half of 13th century) is one of the most influential works on music and dance. The Sangita-ratnakara is a great compilation, not an original work, which ably brings together various strands of the past music traditions found in earlier works like Nāţyashastra, Dattilam, Bŗhaddēśī, and Sarasvatī-hŗdayālańkāra-hāra. It is greatly influenced by Abhinavagupta’s Abhinavabharati. But for Samgita-ratnakara, it might have been more difficult to understand Natyasastra, Brhaddesi and other ancient texts. But, while dealing with Desi class of Dance, Sarangadeva follows Manasollasa of Someshwara.

The text of Sangita-ratnakara has 1678 verses spread over seven chapters (Saptaadhyayi) covering the aspects of Gita, Vadya and Nrtta: Svaragat-adhyaya; Ragavivek-adhyaya; Prakirnaka-adhyaya; Prabandh-adhyaya, Taala-adhyaya; Vadya-adhyaya and Nartana-adhyaya. The first six chapters deal with various facets of music and music-instruments; and, the last chapter deals with Dance. Sangita-ratnakara’s contribution to dance is very significant.

Chapter Seven– Nartana: The seventh and the last chapter, is in two parts; the first one deals with Nartana. Sarangadeva, following Someshwara, uses a common term Nartana to denote the arts of Nŗtta, Nŗtya and Nāţya. In describing the Marga tradition of Dance, Sarangadeva follows Natyashastra. As regards the Desi class of Dance he improves upon the explanations offered in Manasollasa of King Someshwara and Sangita Samayasara of Parsvadeva.

According to Sarangadeva, the Nrtya covers rhythmic limb movements (Nrtta) as also eloquent gestures expressing emotions through Abhinaya. It is a harmonious combination of facial expressions, various glances, poses and meaningful movements of the hands, fingers and feet. Nrtyam, the dance, delightfully brings together and presents in a very highly expressive, attractive visual and auditory form, the import of the lyrics (sahitya), the nuances of its emotional content to the accompaniment of soulful music and rhythmic patterns (tala-laya).

Although he follows Bharata in describing the movements of the body, he differs from Bharata in dividing the limbs into three categories, Anga, Upanga and Pratyanga.

He also differs from Natyashastra which identifies Tandava as Shiva’s dance and Sukumara (Lasya) as Parvati’s. According to Sarangadeva, Tandava requires Uddhata (forceful) and Lasya requires Lalita (delicate) movements.

Sarangadeva’s description of Cari, Sthana, Karana and Angaharas of the Marga type are the same as in the Natyashastra. But the Desi Caris, Sthanas and Utputi–karanas are according to Manasollasa of Someshwara.

Sarangadeva explains the importance of aesthetic beauty; and also lays down the rules of exercise. He also describes the qualities and faults of a performer (including a description of her make-up and costume); and, those of the teacher and the group of supporting performers. Then he describes the sequential process of a performance, including the musical accompaniment, in the pure mode or suddha-paddhati.

(11) The Sangita Upanishad Saroddhara is a treatise on music and dance written in the fourteenth century (1350 A.D.) by the Jaina writer Sudhakalasa. The work is in six chapters, the first four of which are on Gita (vocal music), Vadya (musical instruments) and on Taala (rhythm). The fifth and the sixth chapters are related to dancing.

The term he uses to denote dance is Nrtya. His understanding of the terms Nrtta, Nrtya and Natya varied from that of his predecessors. According to him, Nrtta is danced by men, Nrtya by women, while Natya is Nataka, performed by both men and women.

And, his treatment of the movements of the feet (pada-karmas) and the postures (Sthanas and Sthanakas) differs from that of other texts. According to him, Sthanas are postures meant for women; while, Sthanakas are postures meant for men. Karanas, according to Sudhakalasa, are components of Lasyangas and Nrtya. Obviously, he was recording the contemporary practice, without specific reference to the earlier texts and traditions.

*

(12) The Sangitacandra is a work containing 2168 verses by Suklapandita, also known as Vipradasa (Ca. fourteenth century). He explains the procedures of the Purvaranga; and classifies its dance Nrtta into three categories: Visama (heavy), Vikata (deviated) and Laghu (light). Such classification of Nrtta and such terms to describe Nrtta had not been used earlier by any author.

He then, initially, divides Nrtya, the dance, into two classes: Marga-nrtya which expresses Rasa; and, Natya-nrtya, which expresses Bhava. And, then, brings in the third variety of Nrtya, the Desiya Nrtya, the regional types. Thereafter, he divides each of the three varieties of Nrtya into Tandava and Lasya.

Again, Vipradasa‘s understanding of the terms and concepts of Dance and their treatment; and, emphasis on the Desi dances, reflect the contemporary practices of the medieval period.

*

(13) A major work of the medieval period is the Sangita-damodara by Subhankara (ca. Fifteenth century). Although the Sangita-damodara is principally a work on music and dance, it includes substantial discussions on drama as well. Of its Five Chapters, the Fourth one relates to Dance. Here, dancing is discussed under two broad heads: Angahara (Angaviksepa, movements of the body) and Nrtya (the dance proper).

Under Angahara, the author includes Angikabhinaya, as related to Drama, because it means acting by using the movements of the limbs. As regards Nrtya, he treats it, mostly, as Desi Nrtya, the regional dances. Nrtya is divided into two types: Tandava, the Purusha-nrtya, danced by men; and, Lasya, the Stri-nrtya, danced by women.

Under Natya, Subhankara includes twenty-seven major type of Dramas (Rupaka) and minor types of Drama (Uparupaka). He classifies them under the heading Nrtye naksatramala, the garland of stars in Nrtya.

Thus, by then , the concept of dance in terms of its male and female forms and movements had crept in. Further, the Dance-drama, based in music, was treated as a form of Nrtya. The Nrtya was generally understood as Desi Nrtya.

*

(14) Another important work from this period is the Nrtyadhyaya of Asokamalla (Ca. fourteenth century). The Nrtyadhyaya consisting of 1611 verses follows the Desi tradition of dance, as in Sangita-ratnakara and the Nrtta-ratna-vali.

The text describes, in detail, the hand gestures followed by the movements of the major and minor limbs, that is, Anga, Upanga and Pratyanga.

It also describes Vicitra-abhinaya (various ways of acting), dividing it into elements of Bhava-abhinaya (expressions displaying emotions); and, Indriya-abhinaya (gestures through use of limbs), resembling the Samanya-abhinaya and Citra-abhinaya, as in Natyashastra. The author also describes one hundred and eight Karanas of Bharata. The text ends with descriptions of Kalasas, generally understood as dance movements with which a performance concludes.

*

(15) The Rasakaumudi of Srlkantha (a contemporary and student of Pundarika Vitthala – 16th-17th century) is again a work of general nature that deals with vocal music (Gana), instrumental music (Vadya), Dance (Natya) , Drama (Rupaka) and aesthetics (Rasa) etc. The text is of interest to Dance, mainly because of the contemporary scene of dancing it portrays. It mentions ten divisions of Natya as: Natya, Nrtya, Nrtta, Tandava, Lasya, Visama, Vikata, Laghu, Perani and Gaundali. But, he calls only the first variety Natya as being authentic.

But, the main contribution of Rasakaumudi is the introduction of the concept of ‘Prana’ or the essential elements of the performance; the summation of what a dancer should aim at, while performing. The ten Pranas listed are : the line (Rekha); the steadiness (Sthirata); the swiftness (Vega); the pirouettes (Bhramari), the glance (Dristi); the desirous smile (Smita); the pleasing appearance (Priti); the intellect (Medha); the speech (Vachya); and , the song (Gitam) – RK. 5. 162.

*

(16) The Sangltadarpana of Chatura Damodara (a poet at Jahangir’s court, which places him in the seventeenth century) is, again, a work on music and dance. Its seventh, the final chapter, is related to dancing; and, it generally follows Nartananirnaya of Pundarika Vittala. It also adopts Nartana as the general name for dancing; and, mentions Nrtta, Nrtya, Natya, Tandava and Lasya as the types of Nartana. It then divides Nrtya into five sub-divisions: Visama, Vikata, Laghu, Perani and Gaundali, all of which are Desi forms.

There is greater emphasis on Desi forms, in its discussions. And, the authors of this period followed and adopted the views of the Nartananirnaya; and, there was a steady drift taking the discussions away from the concepts and terminologies of the Natyashastra.

*

(17) Sangitanarayana by Purusottama Misra, a poet at the court of Gajapati Narayanadeva of Orissa (seventeenth century), in its four chapters deals with music and dance. For a greater part, it reproduces the concepts and terms of dancing as in the other texts, particularly Nartananirnaya. The new information it provides relates to the enumeration of the names of twelve varieties of Desi-Nrttas; five varieties of Prakara-Natya of the Desi type; eleven varieties of Marga Natyas and sixteen varieties of Desi Natyas – dramatic presentations ; and, names of thirty-two Kalasa-karanas

*

(18) The Sangita-makaranda of Vedasuri (early seventeenth century) follows Nartananirnaya of Pundarika Vitthala. The new information it provides is with regard to the Gatis. He treats each Gati like a dance sequence; and, describes each Gati with all its components of movements. For instance; while describing the Marga-gati, the author gives all the movements necessary for its presentation, such as the appropriate Karana, Sthanas, Cari, the hand-gestures, the head movements and glances.

He seems to have been interested mainly in the structure of dance compositions as combinations of smaller movements. He describes these movements step by step; and, includes with each movement the appropriate rhythm and tempo that it should go with.

Texts dealing mainly with the theory and practice of Dance

There were also texts and treatise, which were wholly devoted to the discussions on the theory, practice and techniques of Dance. The numbers of such texts are not many; but, are relevant to the contemporary Dance training and learning. The following are the more significant ones, among them:

(1) The date of the Abhinaya Darpana of Nandikeshvara is rather uncertain. The scholars tend to place it in or close to the medieval period; because, it divides dance into three branches: Natya, Nrtta and Nrtya. But, such distinctions did not come about until the time of Sangita-ratnakara (13th century). Also, the Abhinaya Darpana views Tandava and Lasya as forms of masculine and feminine dancing, which again was an approach adopted during the medieval times.

Abhinaya Darpana deals predominantly with the Angikabhinaya (body movements) of the Nrtta class; and, is a text that is used extensively by the Bharatanatya dancers. It describes Angikabhinaya, composed by the combination of the movements of Angas (major limbs- the head, neck, torso and the waist), Upangas (minor limbs – the eyes, the eyebrows, the nose, the lower lip, the cheeks and the chin), Pratayangas (neck, stomach, thighs, knees back and shoulders, etc) and the expressions on the countenance. When the Anga moves, Pratyanga and Upanga also move accordingly. The text also specifies how such movements and expressions should be put to use in a dance sequence.

According to the text, the perfect posture that is, Anga-sausthava, which helps in balancing the inter relationship between the body and the mind, is the central component for dance; and, is most important for ease in the execution and carriage. For instance; the Anga-sausthava awareness demands that the performer hold her head steady; look straight ahead with a level gaze; with shoulders pushed back (not raised artificially); and, to open out the chest so that back is erect. The arms are spread out parallel to the ground; and, the stomach with the pelvic bone is pushed in.

The techniques of dance, body movements, postures etc. described in this text, is a part of the curriculum of the present-day performing arts.

The emphasis on Angikabhinaya in Nrtta requires the dancer to be in a fit physical condition, in order to be able to execute all the dance movements with grace and agility, especially during the sparkling Nrtta items according to the Laya (tempo) and Taala (beat).

[Another text Bharatarnava is often discussed along with the Abhinavadarpana. There is a School of thought, which holds the view that the two texts relating to the practice of Dancing – Abhinaya Darpana and Bharatarnava – were both composed by Nandikesvara. It also asserts that the Abhinaya Darpana is, in fact, an abridged edition or a summary of the Bharatarnava; literally, the Ocean of Bharata’s Art. But, identity of Nandikesvara who is said to have authored the Abhinaya Darpana is not clearly established

But the authorship and the Date of the Bharatarnava is much disputed. Now, it is generally taken that the two texts –Abhinaya Darpana and Bharatarnava – were composed by two different authors, who lived during different periods.]

(2) Closely following upon the Sangita-ratnakara, the Nrtta-ratnavali by Jaya Senapati was written in the thirteenth century A.D. This is the only work of that period, which deals exclusively with dance, in such detail. Nrtta-ratnavali devotes all its eight chapters to dance; and, discusses vocal or instrumental music only in the context of dance.

The first four chapters of the text discuss the Marga tradition, following the Natyashastra; and, the other four discuss the Desi.

The Marga, according to Jaya Senapati, is that which is faithful to the tradition of Bharata; and, is precise and systematic. While dealing with the Marga, although he broadly follows the Bharata, Jaya Senapati provides specific details of the execution of the Karanas and Caris. He also quotes the views of earlier writers, in order to trace the evolution of Dance and its forms.

The First Chapter describes the four modes of Abhinaya, i.e., Angika, Vachika, Aharya and Sattvika; as also the six forms of dancing – Nrtta, Nrtya, Marga, Desi, Tandava and Lasya. The Chapter Two deals with Abhinaya, describing in detail the movements of the major and minor limbs: six Angas, six Pratyangas and six Upangas. The Third Chapter is on Caris (movements of one leg); Sthanas (postures); Nyaya (rules of performance); Vyayama (exercise); Sausthava (grace); more Sthanas and Mandalas (combinations of Caris). The Fourth Chapter describes Karanas (dance-units) and Angaharas (sequences of dance-units); and, ends with Recakas (extending movements of the neck, the hands, the waist and the feet) mainly following their descriptions as given in the Natyasastra.

The second half of the text is devoted to the Desi tradition. The more significant contribution of Nrttaratnavali is in its detailed descriptions of the Desi Karanas, Angaharas and Desi Caris. And, of particular interest is its enumeration and description of Desi dance pieces.

The Fifth Chapter defines the term Desi; and, goes on to describe the Desi sthanas, Utpati-karanas (Desi karanas) and Bhramaris (spin and turns). The sixth chapter deals with movements of the feet, Desi Caris. Jaya Senapati then describes forty-six varieties of Desi Lasyangas, which include the Desi Angas, following the Sangita-samaya-sara. The Gatis or gaits are described next. The Seventh Chapter mainly deals with individual Desi dance pieces, Desi-nrtta. These include Perani, Pekkhana, Suda, Rasaka, Carcari, Natyarasaka, Sivapriya, Cintu, Kanduka, Bhandika, Ghatisani, Carana, Bahurupa, Kollata and Gaundali.

The Eighth and Final Chapter , provides information regarding presentation in general, the recital, the appropriate time for its presentation, the arrival of the chief guest and the welcome accorded the king, other members of the audience, the qualities required in a dancer, her costume, the orchestra, the sitting arrangements, the entrance of a dancer, the use of three curtains on the stage and their removal. The Chapter ends with advice on honoring the dancer, the musicians and the poet.

(3) The Nrtya-ratna-kosa of Maharana Kumbha (a scholar king of the fifteenth century), is part of a larger work, the Sangita-raja, which closely follows the Sangita-ratnakara of Sarangadeva. It is the Fourth Chapter of Sangita-raja; and, deals with Nrtya. The Nrtya-ratna-kosa is divided into four ullasas or parts; each consisting of four pariksanas or sections. It is mostly a compilation of the concepts, definitions, theories and practices concerning Dance – both Marga and Desi– culled out from earlier texts, particularly from Sangita-ratnakara. While describing various types of dance-movements, the emphasis is more on the Desi types.

The first section of the first part describes the origin of the theories of Natya (shastra); the rules of building the performance-hall; the qualifications of the person presiding; and, of the audience. It also offers definitions of certain fundamental terms.

Raja Kumbha defines the terms Nrtta, Nrtya and Natya. According to him, Nrtta is made up of combination of Karanas and Angaharas (Karanam angaharani caiva Nrttam); Nrtya is Rasa (Nrtya sabdena ca Rasam punaha); and, Natya is Abhinaya (Natyena abhinayam).

The Nrtya is classified as Marga; and, Nrtta as Desi. The Pindibandhas or group dances, performed by sixteen female dancers as part of the preliminaries are included under Nrtta.

The rest of the verses are devoted to Angikabhinaya or the movements of the body. The text discusses, in detail, about limb movements like Pratyangas, Upangas etc.; and, also about Aharya-bhinaya or costume, make-up and stage properties.

There are also descriptions of Marga and Desi Caris, Shanakas or postures, meant for men and women, for sitting and reclining. Similarly, the Karanas are classified as Shuddha karanas (pure) of the Marga class; and, as Desi Karanas.

That is followed description of four Vrttis or styles and six kalasas (dance movements with which a performance concludes), with its twenty-two sub-varieties.

Towards the end, it enumerates the qualities and faults of a performer. It discusses make-up; different schools of performing artists; their qualities and faults; the Shuddha-paddhati or the pure way of presentation; and, states the ways of imparting instructions to performers.

(4) The Nartana-nirnaya of Pundarika Vitthala (16th-17th centuries) is a very significant work in the history of Indian Dancing. Till about the time of Raja Kumbha, the Dance was discussed mainly in terms of Marga and Desi. Pundarika Vitthala introduces a novel feature (hitherto not tried by anyone else), which is the principles of Bhaddha (structured) and Anibhaddha (neither bound nor structured) for stratifying the dance forms into two separate classes. Even though the later texts on dancing generally followed the Sangita-ratnakara, they did take into consideration Nartana-nirnaya’s classification of Bhaddha and Anibaddha, as a part of their conceptual framework. His classification of Dance forms into Baddha and Anibaddha was a significant theoretical development.

The Nartana-nirnaya was written in the sixteenth century, while Pundarika Vitthala (or Pandari Vitthala) was in the service of the Mughal Court. It comes about five hundred years after Sangitaratnakara. This period between these two texts was marked by several interesting and rather radical changes and transformations that were taking place in India , in the field of Arts.

The Nartananirnaya was composed in an altogether different ambiance. The courts of Raja Man Singh, Raja Madhav Singh and Akbar provided the forum for interaction between the North and South Indian traditions on one hand; and between Indian and Persian practices on the other. This was an interesting period when diverse streams of Art came together.

Pundarika Vittala mentions that he wrote the Nartananirnaya, concerning music and dance, at the suggestion of Akbar, to cater to his taste – Akbara-nrupa rucyartham

The subject matter central to Nartana-nirnaya is dancing. The technical details of dance as detailed in the Nartananirnaya are an important source for reconstructing the history of Indian music and dance during the middle period. This was also the time when the old practices were fading out and new concepts were stepping in. For instance, by the time of Pundarika Vittala, the 108 Karanas were reduced to sixteen. At the same time , dance formats such as Jakkini, Raasa nrtya were finding place among traditional type of Dances.

In his work, Pundarika Vitthala does not confine only to the traditional dances of India and Persia; but, he also describes the various dance traditions of the different regions of India that were practiced during his time. The information he provides on regional dance forms is quite specific, in the sense that he points to the part/s of India from where the particular style originated, the language of the accompanying songs and the modes its presentation. The Nartana-nirnaya is, therefore, an invaluable treasure house on the state of regional dance forms as they existed in the sixteenth century India. Thus, Nartana-nirnaya serves as a bridge between the older and present-day traditions of classical Indian dancing.

The chapter titled Nartana-prakarana, dealing with Nrtta and Nartana, is relevant to Dancing. The Nrtta deals with the abstract aesthetic movements and configuration of various body parts. And, Nartana is about the representational art of dancing, giving expression to emotions through Abhinaya. The Nartana employs the Nrtta as a communicative instrument to give a form to its expressions.

Another chapter, Nrttadhikarana is virtually about the Grammar of Dance. It describes the Nrtta element of Dancing with reference to the special configuration of the static and moving elements of the Dance, such as: Sthanaka, Karana, Angahara, Cari, Hasta, Angri, Recaka, Vartana etc.

Then the text goes on to enumerate the items of the dance recital: entry of the dancer (Mukhacali, including Pushpanjali); Nanadi Slokas invoking the blessings of the gods; the kinds of Urupa, Dhavada, Kvada, Laga and Bhramari. It also mentions the dance forms originating from various regions: Sabda, Svarabhinaya, Svaramantha, Gita, Cindu, Dharu, Dhruvapada, Jakkadi and Raasa.

Some of these are classified under Bandhanrtta, the group dances with complex configurations and formations. These are also of the Anibaddha type, the graceful, simple dances, not restricted by the regimen of the rules etc.

The Nartana-nirnaya is indeed a major work that throws light on the origins of some of the dance forms – particularly Kathak and Odissi – that are prevalent today

[We shall discuss many of the texts enumerated above, individually and in fair detail, later in the series.]

Overview

All the texts enumerated above deal with the subject of dance in some detail; exclusively or along with music, drama and poetics.

When you take an over view, you will notice that three texts stand out as landmarks, defining the nature and treatment of dance in the corresponding period. These three are: Natyashastra of Bharata (Ca. 200 BCE); Abhinavabharati of Abhinavagupta (10-11th century) and Sangita-ratnakara of Sarangadeva (13th century).

Natyashastra is, of course, the seminal text that not only enunciated the principles of Dancing, but also brought them into practice. Though the emphasis of Natyashastra was on the production and presentation of the play, it successfully brought together the arts of poetry, music, dance and other decorative elements, all of which contributed to the elegance of the theater.

The Dance that Bharata specifically refers to is Nrtta, pure dance, which was primarily performed before the commencement of the play proper (Purvaranga) as a prayer offered to gods. The elements of the Nrtta were also brought into Drama by fusing it with Abhinnaya. Though the resultant art-form was not assigned a name by Bharata, its essence was very much a part of the theatrical performance. And, this delightful art form came to be celebrated as Nrtya, during the later periods. And, in its early stages, Dance was not considered as an independent Art-form.

Several commentaries on the Natyashastra that were produced between the period of Bharata and Abhinavagupta are lost. And, the Abhinavabhatarati is the earliest available commentary on the Natyashastra; and, is, therefore, highly valuable. Abhinavagupta followed Bharata, in general; and, adhered to his terminologies. For instance, while discussing on Dance, Abhinava consistently uses the term Nrtta; and, avoids the term Nrtya (perhaps because it does not appear in Natyashastra). During his time, dance, music and dramatics were continued to be treated as integral to each other, as in the times of Natyashastra.

Yet; Abhinavagupta, brought in fresh perspective to the Natyashastra; and, interpreted it in the light of his own experience and knowledge. His commentary, therefore, presents the dynamic and evolving state of the art of his time, rather than a description of Dancing as was frozen in Bharata’s time. As it has often been said; Abhinavabharati is a bridge between the world of the ancient and forgotten wisdom and the scholarship of the succeeding generations.

Abhinavagupta’s influence has been profound and pervasive. Succeeding generations of writers on Natya were guided by his concepts and theories of Rasa, Bhava, aesthetics and dramaturgy. No writer or commentator of a later period could afford to ignore Abhinavagupta.

The commentaries written during the period following that of Abhinavagupta continued to employ the terminologies of the Natyashastra. But, the treatment of its basic terms such as, Nrtta, Natya, Tandava and Lasya was highly inconsistent. These terms were interpreted variously, in any number of ways, depending upon the understanding and disposition of the author; as also according to contemporary usage of those terms and the application of their concepts. Standardisation was conspicuous by its absence.

A significant development during this period was assigning greater importance to the regional types of Dances. Though based on the Natyashastra, these texts recognized and paid greater attention to the dance forms that were popular among the people of different geographic regions and of different cultural groups. In the process, the concepts of Marga, which signified the chaste, traditional form of Dance as per the rules of Natyashastra, came to be distinguished from the regional, popular, free flowing types of Dance, termed as Desi.

By about the 13th century, dance came into its own; and, was no longer an ancillary to drama, as was the case during the time of Natyashastra. Yet; the Dance, in this period, continued to be discussed along with the main subjects such as Music and Drama.

The concept of Nrtta continued to exist and Nritya was established; each with its own individual identity. The term Natya which signified the combination of Nrtta (pure dance) and Abhinaya (meaningful expressions) had come into wide use.

The Sangita-ratnakara of Sarangadeva marks the beginning of the period when Dance began to be discussed in its own right, rather than as an adjunct to Drama. It was during this period, the Desi types of Dance along with its individual forms were discussed in detail. And, the other significant development was the fusing of the special techniques of Angikabhinayas of both the Nrtta and the Desi types into the graceful Natya form. And, new trends in Dance were recognized.

Though the ancient terms Nrtta, Tandava, Lasya and Natya continued to be interpreted in various ways, the term Nartana came to be accepted as the general class name of Dance, comprising its three sub-divisions: Natya, Nrtya and Nrtta.

In the period beginning with the sixteenth century, Pundarika Vittala introduced the new concept of classifying dance forms into two separate classes, as the Bhaddha (structured) and Anibhaddha (neither bound nor structured). The later texts, while discussing Dance, apart from following Marga and Desi classification, also took into consideration Nartana-nirnaya’s classification of Bhaddha and Anibaddha, as a part of their conceptual framework.

It was during this period, the Persian influence, through the Mughal Court , entered into Indian dancing, giving rise to a new style of Dance form, the Kathak. This period was also marked by the emergence of the Dance forms that were not specifically mentioned in the Natyashastra – the Uparupakas. This genre of musical dance dramas not only came to be admitted into the mainstream of dancing, but eventually became the dominant type of performing art, giving rise dance forms such as Odissi, Kuchipudi etc.

The emphasis of the later texts shifted away from the Marga of the Natyashastra; but, leaned towards the newer forms of Desi Dances with their improvised techniques and structural principles. Apart from increase in the varieties of regional dance forms, a number of manuals in regional languages began to appear. These regional texts provide a glimpse of the state of Dance as was practiced in different regions.

Dr. Mandakranta Bose observes:

Bharata’s account represented only a small part of the total body of dance styles of the time. When new styles became prominent in the medieval period they had to be included in the descriptions of dancing. Such a widening of frontiers meant a great increment of technical description in the texts.

The distinction between the Natyashastra and the later texts is not merely one of detail. Of greater significance is the fact that unlike the Natyashastra, the later texts recognize different styles. These are distinct from the one described by Bharata, the main path or Marga tradition of dancing. The later texts concern themselves more and more with other styles, known, generically, as Desi, whose technique and structural principles are sufficiently different from the style described by Bharata..

Further, the principle of Anibaddha allowed the dancer a considerable degree of freedom, encouraging her to search far and to create, through her ingenuity, novel aesthetic expressions. This was a major departure from the regimen that required the dancer to rigorously follow the prescriptions of the texts. The opportunities to come up with artistic innovations, within the framework of the tradition, helped to infuse enterprise and vitality into dance performances. The dance became more alive.

At the same time, the Natyashastra continues to be the authoritative source book, which lays down the basic principles of the performing arts; and, identifies the range of body movements that constitute dancing.

The Bharatanatya of today represents such a dynamic phase of the traditional Indian Dancing. It does not, specifically, have a text of its own; its roots are in the principles, practices and techniques that are detailed in Natyashastra, Abhinava Darpana and such other ancient texts. Though it is basically ingrained in the principles of Natyashastra, it delightfully combines in itself the Angikabhinaya of the Nrtta; the four Abhinayas of the Natya (Angika, Vachika, Aharya and Sattvika); the interpretative musical narrative element of the Uparupakas, for enacting a theme; and the improved techniques of the later times.

Besides, the Bharatanatya developed its own Grammar through Dance idioms such as: Adavus (combination of postures – Sthana, foot movement – Chari, and hand gestures-Hasta); Jati (feet movement in tune with the Sollakattu syllables); Tirmanam (brilliant bursts of complicated dance rhythms towards the ‘end’ section of the dance). Besides, the Bharatanatya, in the context of its time, enriched its repertoire of the Nrtta by items such as Alaripu, Jatiswara and Tillana.

Thus, the evolution of Indian Dance system is a dynamic process that absorbed new elements and techniques without compromising its basic tenets. It, thus, demonstrates the time-honored Indian principle of growth: continuity along with change.

Before we discuss Dance and its forms, let’s take a look at the Art and Art-forms, in general.

Continued

In

Part Two

References and sources

1.Movements and Mimesis: The Idea of Dance in the Sanskritic Tradition by Dr.Mandakranta Bose

2 . Literature used in Dance/ Dance Sahitva

3. Natyashastra

4.https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file%3Faccession%3Dosu1079459926%26disposition%3Dinline

The images are from Internet

![]()

Bharata, under the Pratyanga, had mentioned six parts as: the neck, the belly, the thighs, the shanks and the arms.

Bharata, under the Pratyanga, had mentioned six parts as: the neck, the belly, the thighs, the shanks and the arms. Sarangadeva, in addition to the nine Upangas in the head, as mentioned by Bharata, brought in the elements of the breath, the teeth and the tongue. However, Bharata had not considered these three as Upangas.

Sarangadeva, in addition to the nine Upangas in the head, as mentioned by Bharata, brought in the elements of the breath, the teeth and the tongue. However, Bharata had not considered these three as Upangas.