[This article and its companion posts may be treated as an extension of the series I posted on the Art of Painting in Ancient India .

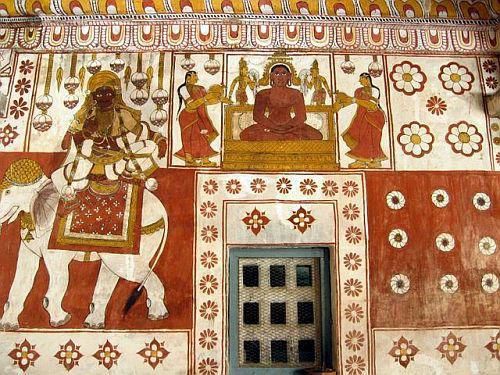

This is the concluding part of a series that attempted to trace the influence of Chitrasutra, the ancient text and its recommended practices, from the days of the Ajanta to the present period.

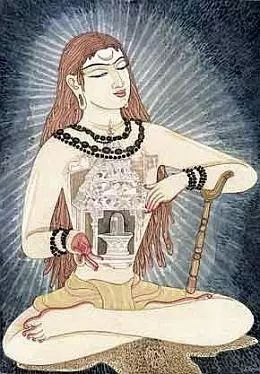

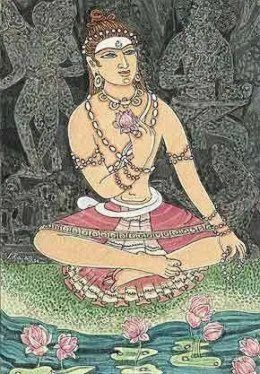

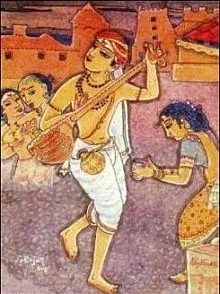

In the concluding part of this series we admire the sublime paintings of Shri S Rajam, perhaps the sole votary of Chitrasutra tradition in the modern times.

The part – One of this article briefly outlined Shri S Rajam’s achievements in the field of music and in the music related arts.

In this concluding article part let’s look at a few of the general principles of the Chitrasutra and Shri Rajam as an artist who brought to life the traditional art style of India.]

Continued from S Rajam Part One

1.1. The Chitrasutra of Vishnudharmottara, an ancient text dated around sixth century AD, states that one needs to understand music to be a good painter. That might be because the rhythm, fluidity and grace of music have to be transported to painting, in order to make the painting come alive and open its heart to the viewer (sah-hrudaya). That ideal requirement found its fulfilment in Shri S Rajam an eminent musician who is also blessed with a unique gift of creating sublime art works. He practiced both the arts with devotion and dedication over long years of his fruitful life.

1.2. I mentioned earlier that Shri S Rajam has been a true exponent of the Chitrasutra tradition in the modern era. Let’s get to know a bit more about Shri S Rajam’s art, mostly through his own words and pictures; and about his inspiration and guidance..

2. The Early years

2.1. Rajam took to art quite early in his life. By the time he was about fifteen years of age (when he was in Eighth grade) he was sketching fairly well. His father, Sundaram Ayyar as also his friends and relatives who too were artists, encouraged Rajam to hone his skills. He thereafter discontinued formal schooling in his senior year in High school to join the Government School of Arts and Crafts in Madras (1935). He appears to have had a great time in the Art School. He not only had a brilliant academic career but also enjoyed the friendship and support of his friends and teachers. The Principal was so impressed by Rajam’s talent, that he allowed the boy to complete the six-year course in just four years

Later in his life, when he was in his eighties, Shri Rajam while talking about his technique of water-wash said, “I learnt it all from my teacher Shri V. Doraisamy Achari”. Rajam’s Art – school-mates included KCS Panicker, Dhanapal and Kodur Ramamurthy who also flowered into great artists.

3. The quest

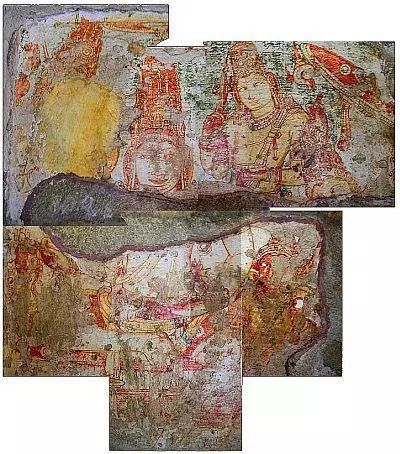

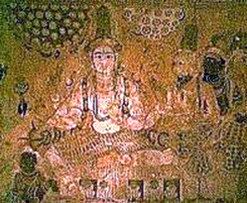

3.1. The young Rajam’s visit to the caves of Ajanta was a turning point in his life; it had a profound effect on him; and changed his life and artistic career forever. The ancient art of Ajanta brought about a sea change in Rajam’s outlook of art; his style of depiction in painting; and his attitude to life in general. He realized, painting was not just a technique of putting paint over a surface; it was a way of understanding and expressing your emotions about the life around you; it was a way of looking beyond the forms and appearances that meet the eye; and above all, it was about giving expression to a deeply spiritual experience that springs from the artists very inner being. The practice of art, he said, was a Sadhana, to be pursued with dedication and reverence.

3.2. The traditional style of the ancient murals at Ajanta so overwhelmed S Rajam that he suspended his painting activity for a while and got immersed in search of a style of his own that would at once be creative, traditional and soulful. He did eventually, after years of practice, succeed in his search and came up with a unique style that answered his quest and prayer.

Mr. Lewis Thompson (1909-1949) of England — a poet turned philosopher and Sanyasin – was also instrumental in Rajam adopting the Oriental school approach in his painting techniques. “I owe it to Lewis Thompson who came to Sri Ramana Ashram, where I used to sing occasionally. He was an English poet, deeply interested in Indian philosophy, ten years my senior. He used to write his verses in tiny books. He was responsible for my development and growth in Indian art. He moulded me. He would say, “Art must represent nature, not reproduce it. That’s why you see that Akbar is bigger than the horse in the miniatures. Learn perspective but ignore it once you have mastered it.. The size of the figures depends on their relative importance. “

The following is a brief note on Mr. Thompson.

[ Lewis Levien Thompson was born on January 13, 1909 in Fulham, England. He received a good conventional education in private schools, despite the modest circumstances of his family. He was a good singer and accomplished pianist. In his teens, Lewis developed a fascination for the scriptures of the East. He taught himself the Eastern classics, in translations. He also read extensively in anthropology and psychoanalysis. He was greatly influenced by the French poet of the symbolist school Rimbaud (1854-1891) and his wish to discover the soul and the truth.

Like many western intellectuals of the early twentieth century who travelled East in search of spiritual wisdom, Lewis Thompson too abandoned his attachments and allegiances; and plunged into the depths of Eastern philosophy and spirituality. He departed from England when he was 23 years young (July 26, 1932) and lived in India for the remaining seventeen years of his short life. While in India, he wandered the country living off of what others would give him in the form of food and lodging. Thompson was not interested in finding a guru; but he came into close contact with various luminaries, including Sri Ramana Maharishi, Anandamayi Ma, Aurobindo, and Krisha Prem.

During his wandering years in India, Thompson practiced severe self-discipline of an iterant monk and produced some hundred-odd poems; an endless stream of aphorisms; maintained journals over his life in India as a marga, a spiritual discipline; wrote a large number of letters, and various miscellanea.

On June 19, 1949, Lewis Thompson was found wandering dazed and penniless by the River Ganges. Taken to a small room, he languished for two days, writing the last entry in his journal and his last poem, Black Flower, before lapsing into a coma. He died alone in Benares on June 21, 1949.

His journal and a collection of his poems Black Sun were published posthumously during 2001, with an introduction by Richard Lannoy. Lewis Thompson’s work is deeply spiritual, lush with Hindu imagery; and is sensitive, mystical and erotic. He was later described as ‘one of the most original, brave, brilliant and prescient of the pioneers of our contemporary mystical Renaissance’; and,’ as one of the century’s most intrepid spiritual explorers and a ravishing mystical poet’

http://www.richardstodart.com/Lewis%20Thompson.html ]

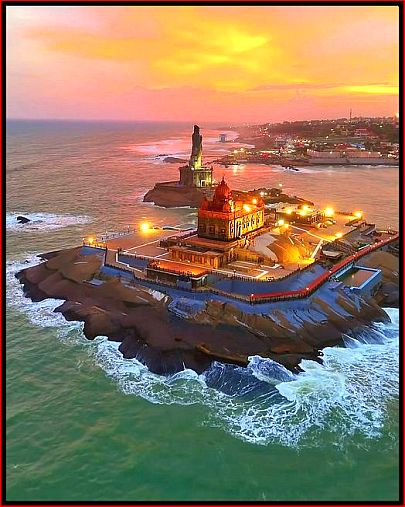

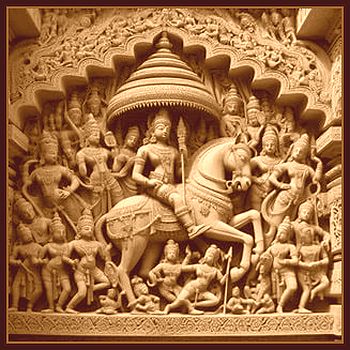

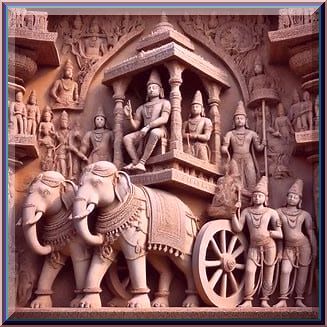

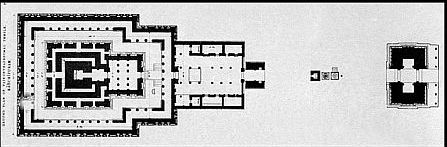

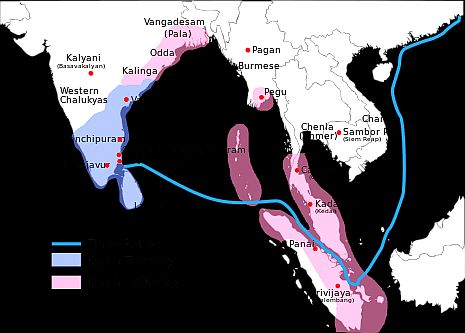

3.3. It is said; the curious scratch the surface, and, it is only the resolute that overcome the obstacles and delve deeper into learning of enduring value. The quest is always more challenging than curiosity but it surely is rewarding. Shri Rajam’s quest for a unique idiom and a style of expression took him far and wide into ancient caves and temples spread across the country and into the study of varied forms of ancient art-creations, such as the murals, frescos, miniatures, Chola bronzes etc. He spent week after week in the caves of Ajanta, Ellora, Amaravathi, Sittannavasal and Sigiriya (Sri Lanka); as also in the ancient temples of South India and Orissa.

3.4. He took thousands of photographs of the sculptures and the bronzes. He was particularly fascinated by the three-dimensional comeliness and grace of the bronzes. He poured over his photographs and turned them into countless sketches and drawings, learning the art and skill of translating his observation into visual poetry; and coining fresh idioms, phrases and similes of art-expressions to stamp his individuality.

3.5. He learnt to visualize his design clearly before giving it a form. “I contemplate on the photograph for many days,” he says, “and form a clear picture in my mind. Then, much later, I transfer the image to the surface of the painting”.Thus, imagination, observation and the expressive force of rhythm became the essential features of his paintings. Through sustained practice,he learnt to make his pictures come alive with rhythm and expression.

In addition , he also studied the ancient texts on painting and sculpture such as the Chitrasutra of Vishnudharmottara, the Kashyapa shilpa sutra etc, along with the epics, puranans and countless dhyana-shlokas which describe precisely the form , appearance , countenance , proportions and the nature of each deity. These texts became his guiding influence; and helped to enhance the authenticity to his depictions.

He also read extensively on the contemporary art-historians and scholars such as Ananada Coomaraswamy, Stella Kramrisch, Gopinatha Rao and others. These helped Rajam as an artist to gain a broader perspective of Indian art.

In 1939, Rajam met Sri K.V.Jagannathan – the editor of “Kalaimagal”. Rajam’s first published work depicting a Guru and his disciple appeared in Kalaimagal the same year. It was the first of the many that would follow.

His illustrations on the themes based on literature, mythology and philosophy became a regular feature in Kalaimagal and other published works of Sri K.V. Jagannathan. It was a matter of time that his works were sought by other publications such as Dinamani, Kalki etc. The special issues like Deepavali Malar gave him ample space to explore his subjects in depth.

4. An unusual Maverick

4.1. The initial years of Shri S Rajam’s art-career were stressful; and acceptance did not come easy. He was branded a maverick, perhaps in the sense that he painted like no one else did. And, not many shared his philosophical perspective on art. He was criticized, mostly, for not belonging to a school of painting. But, that did not deter him in the least. He did not succumb to the trend of the day just for the whim of it. He was convinced that his style was authentic, creative and rooted in the tradition of our culture. He asserted he was not a ‘copier’, but one who painted in his own way. He said, “My art is in representing nature and not in reproducing it”. It is our fortune Shri Rajam stood his ground. Since then, he has been composing his own one-of-a-kind masterpieces for more than six decades. And, today his classical genius is not merely well accepted but revered as an icon of creativity and grace rich in tradition.

4.2. Even so, Shri Rajam is disappointed with the drift of the times. “Hindu heritage and tradition is ancient and priceless,” he laments, “but devotional art is dying in India and almost extinct. Unfortunately, we Indians ape the Westerners. This attitude wounds me a lot. In tradition, only good things should remain; the bad should be ignored and not continued. This is tradition. The art schools in India have failed to bring forward tradition…., Artistic creation is lacking in arts schools. The training imparted is purely technique oriented, and this by itself is not of much use.”

4.3. His message to the young and budding artists of India is this: “Study scriptures to improve your knowledge. Be modern; there is no problem with that. But know the beauty and elegance of your culture.”

5. Shri Rajam’s art and the Chitrasutra

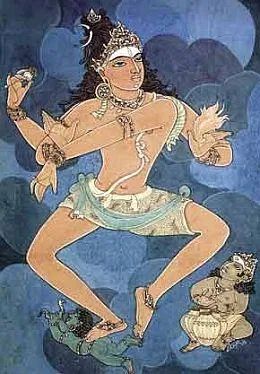

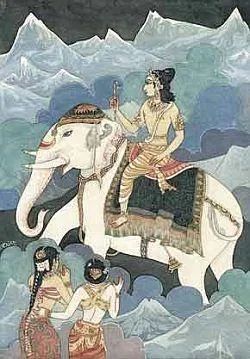

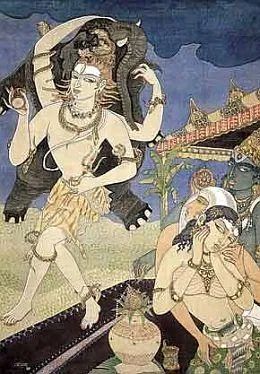

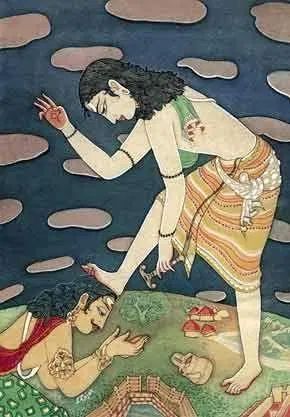

5.1. Outlook

(i ). While talking about his approach to art, Shri Rajam said,” my art is not, nor was it ever meant to be, realistic or photo-like replicas of life, but rather intuitive perception of life”. He asserts that in his paintings and line drawings, he attempts to imprison the important moments of the subject’s life to help the contemplative spirit of the observer.His pictures might depict the resemblance but, more importantly, as he said, they aim to bring out the essence or the soul of the subject.

(ii ) . When Shri Rajam said that, he was not merely making a statement but also was echoing the prescriptions of the Chitrasutra which stressed that the concern of the artist should not be to just faithfully reproduce the forms around him. The artist should try to look beyond the tangible world; and beyond the beauty of form that meets the eye. He should lift that veil and look within. The Chitrasutra suggested, the artist should look beyond “The phenomenal world of separated beings and objects that blind s the vision of the reality”.

(iii ). The Chitrasutra emphasizes that art expression is not about how the world appears to one and all, but how the artist would experience and visualize it. Art is an expression of his unique creative genius, imagination, enterprise and individuality as an artist. Its purpose is to present that which is within us; and to evoke an emotional response (the rasa) in the viewer’s heart.

(iv). Shri Rajam’s art creations are excellent illustrations of these principles of the Chitrasutra in the modern times. In his mission, Shri Rajam followed the approach of the classical Indian Art rather that of the west where art directly reproduces the nature and its physical form as it appears to one and all.

5.2. Abstract & Symbolism

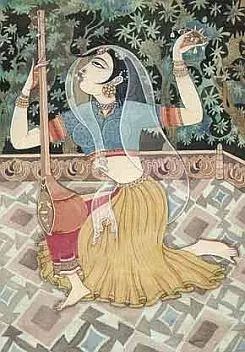

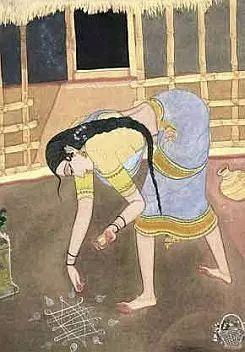

(i ). While explaining the special features of traditional Indian art, Shri Rajam in his interviews and articles stresses the point that the traditional Indian art relies more on symbolism than on realism. He says, an artist’s power arises from observation translated into visual poetry through similes and suggestions. The eloquent expression of a painting, that is, its Bhava, according to him, consists in drawing out the inner world of the subject. It takes a combination of many factors to articulate the Bhava of a painting; say , through eyes, facial expression, stance , gestures by hands and limbs, surrounding nature, animals , birds and other human figures. Even the rocks, water places and plants (dead or dying or blooming or laden) can be employed to bring out the Bhava. These aspects gain greater importance in narrative paintings, which demand special skills to depict the dramatic effects and reactions of the characters, in its progression from frame to frame.

(ii ). The concept of the abstract and with it a whole set of symbols and symbolisms, that Shri Rajam was discussing, were also the concern of the Chitrasutra. The text suggested the means to render the absolute and the undefined into tangible visual forms. It said, the objects in nature could be visualized or personified endowing each with a distinct personality in order to illustrate the essence of their character. Accordingly, in the traditional Indian art, the elements of natures like rivers, sun, moon etc were personified, bringing out their virtues and powers through eloquent symbolisms. Birds and flowers, trees and creepers too were depicted with a loving grace and tenderness. In certain cases, idyllic nature scenes were created just to convey a sense of joy and wonder.

Shri Rajam’s art abounds in such symbolisms.

5.3. The preparation

(i). Shri Rajam talks about the way he prepares before commencing on a painting. It is highly interesting. His approach is methodical, thorough and a classic example for others to follow. He studies every available material about the subject, such as the epics, scriptures, the legends; and, archived documents, earlier paintings and photographs in case of personalities. He visualizes his design, contemplates on it and lets it sink into him. He explains “The subject should be visualized with absolutely clarity in the mind’s eye, before setting pencil to paper. I let the preliminary sketch ‘sit’ for a few days, then review, making corrections and changes. Initially I color the background using a soft wash technique originating from the Santhiniketan School, a special feature in all my paintings. Then I define the main figure through light and shade, with highlights in white. I aim to bring out the grace of the human form and poses, for example tribhanga, with the drapery serving to accentuate form as exemplified in Buddhist sculpture.”

(ii ) . Even to this day, after nearly seventy years of painting, Shri Rajam visualizes his design after careful study and research into the subject; and only then attempts to draw. He says, “I form a clear picture in my mind. Then, much later, I transfer the image to the surface of the painting.”

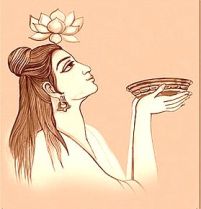

5.4. Rekhas, the lines

(i) . The Chitrasutra regards the lines – Rekhas – that articulate the form of the figures as the real strength and virtue of a painting; and the ornamentation and colouring as its decorative aspects. Chitrasutra favours employing graceful, steady, smooth and free flowing lines. The Chitrasutra does not favour straight or harsh or angular or uneven lines. Its masters valued the effects best captured by least number of lines. The economy of lines and simplicity of expression were regarded as the sign of the artist’s maturity.

(ii) . These too are the characteristics of Shri Rajam’s paintings. The first thing you notice in his works is the strength of the lines that defines precisely the form of the figure. He says, “The line is the life of a painting. I developed my own style, taking from the model of our ancient culture.” He explains that in the oriental traditions, the lines – the Rekhas- are of prime importance unlike in an oil painting. It is the lines that define the substance and form of an oriental painting. He describes his style as closest to Shantiniketan style, emphasizing the lasya – lyrical – aspects.

[The Shantiniketan School of art, sphere headed by the renowned artist Abanindranath Tagore, was a revivalist movement that was started by around 1905. It strived to revive the traditional Indian techniques of art and art styles, deriving inspiration, mainly, from the murals of Ajanta. Its style was, basically, a refined and harmonious blending of simple beauty of expression brought to life by graceful lines and an essential Indianness. The Shantiniketan art done mostly in watercolours depicted Indian religious, mythological, historical and literary subjects. Its style, endowed with the beauty and vigour of its lines, sense of proportion, grace and charm soon became an authentic idiom of Indian art expression.

Shri S Rajam derived inspiration from this tradition too. ]

(iii). The lasya – the lyrical – aspect which Shri Rajam was talking about refers to delineating beautiful figures and their delicate inner feelings through graceful, steady, smooth and free flowing lines that capture their essence. His line-drawings are full of grace and vitality. The delicate touches and intimate details that he deftly adds enliven his figures.

(iii) Following the tradition of the Chitrasutra , Shri Rajam has depicted nature as in summer; Rainy season; Autumn ; early winter ; and, winter :

(iv) Shri Rajam has also sketched some rather ‘non-traditional’paintings :

5.5. Simplicity which is natural and pleasing

(i). Shri Rajam says, he aims to infuse into his paintings a simplicity which is natural and pleasing. He stresses the economy of lines and simplicity of form as central to his approach. It is upon this background, he says, he is able to introduce “personal innovations” into his works. That is the reason; his paintings are a rare blend of traditional styles with his unique touch.

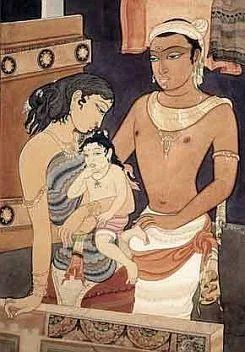

(ii). It is because of that approach you find a natural quality and grace in Shri Rajam’s paintings; they almost seem effortless. The vigor, the strength and the power of a heroic figure are brought to life by the vitality of its lines; not by his fat muscles or his sheer size. With use of shading different parts of the body, it produces three dimensional effects in the images. Even the demons in his paintings are never muscular or excessively fat. The outlines are strong and very sure; and there is an easy and natural depiction of volume, evidencing a good understanding of the rhythm and the structure of the human body.

(iii). His figures are never rigid and static. Their stances are always suggestive of flowing movements of languid grace and charming rhythm. Their distinctive display of smooth motion and the sense of balance are lovely. The painted figures of the “heroes” present a profound sense of peace and joy even while placed amidst activities and contradictions of life.

Shri Rajam’s works are excellent illustrations of the principles and aspirations of Chitrasutra.

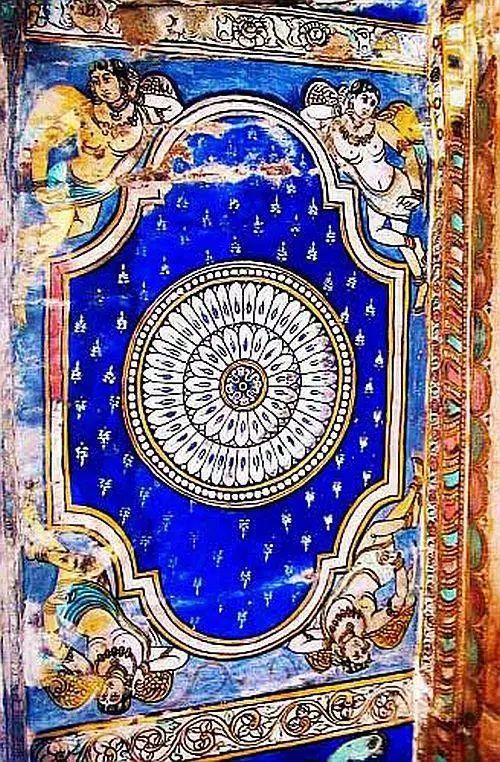

5.6. Colours

(i). Another distinctive feature of Shri Rajam’s works is the use of soft color schemes, uniquely decorated costumes; and delicate, deft cultural “touches” that lend authenticity to the context, period and the status / nature of the subject. He often lets elements drift partially off the canvas. But above all else, there is a flow of curve in all of his designs that projects a certain distinctive grace of smooth motion even in stillness.

(ii). The other is the use of proper colours: soft and subdued, the lines firm and sinuous and the expressions true to life. The colours, at times contrasting and at times matching are artistically employed to create magical effects. That effect is enhanced by skilful shading of the body-parts; giving them a three dimensional appearance; and providing depth to the picture. These were precisely the principles that Chitrasutra too recommended.

(iii). The Chitrasutra aptly remarks, when a learned and skilled artist paints with golden colour, with articulate and yet very soft lines with distinct and well arranged garments; and graced with beauty, proportion, rhythm and inspiration, then the painting would truly be beautiful.

How very true that is in the case of Shri Rajam..!

5.6. Eyes

The Chitrasutra tradition regarded the eyes as the windows to the soul. And, it said, it is through their expressive eyes the figures in the painting open up their heart and speak eloquently to the viewer. It therefore accorded enormous importance to the delicate painting of the soulful and expressive eyes that pour out the essence of the subject. The lively sets of lustrous pools of eyes continue to influence generations of Indian artists; those eyes are, in fact, a hall mark of Indian art works.

One finds a vindication of these principles in Shri Rajam’s paintings.

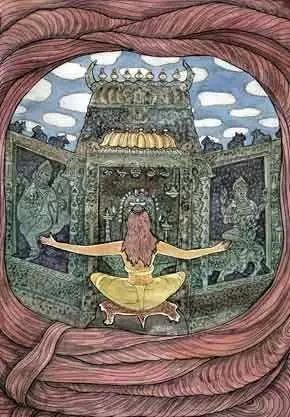

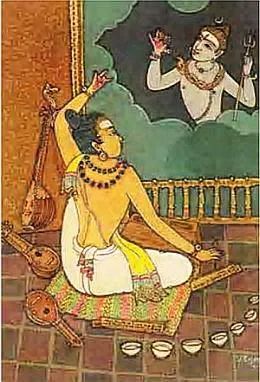

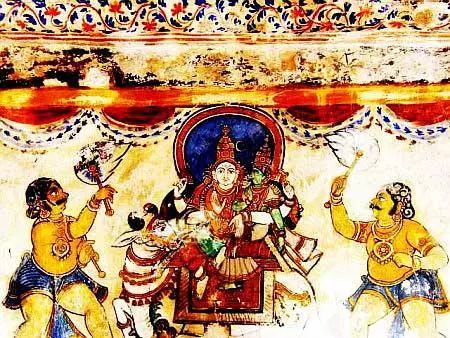

5.7. Gods & Goddesses

(i). A lot of figures depicted by Shri S Rajam are of gods, goddesses, sages and demons; as also of the kings, queens and the composers of the bygone eras. His involvement in their creation was total; he not merely researched into their every available detail but also tried to get into their spirit. “Practically speaking, to paint the Gods and Goddesses, you must imagine them aggressively,” says Rajam “There are rigid rules of grammar regarding proportions. Yet, the artist has to assume the freedom to compose his picture according to his aesthetic sense. There may not be a physical resemblance to the subject; but one should surely try to bring out the essential nature of its character.”

(ii). You will, therefore, find in Shri Rajam’s paintings the virtues and powers of the gods and demons made explicit by employing varieties of forms, symbols and abstract visualizations. That artistic liberty, freedom and felicity of expression is a characteristic of classical Indian art, as also of Shri Rajam’s art. He quotes the text (Chitrasutra) and says, “Rules do not make the painting; it is the artist with a soul and vision who creates the art expressions”.

(iii). Many of his creations have now turned into objects of worship; and adorn the walls of the temples and puja-rooms. That might be because, Shri Rajam’s art awakens the divine presence within us; and we respond to the sublime images brought to us in his art. When that happens, we are filled by grace and there is no space left for base desires and pain: we have become that deity.

Shri Rajam’s art has that magical quality, which brings out the essence of life and the grace that permeate the whole of existence.

5.8. Secular art

Even his secular art is rich in expressive realism, reminiscent of the paintings at Ajanta, Bagh and Sittannavasal. They testify to his love of naturalism – in the depiction of the human form and in the depiction of nature. Yet, his pictures always seem to suggest to something beyond the obvious, stimulating the senses and igniting the imagination of the viewer.

6. The technique

(i). Shri Rajam says, he first paints the outlines , then colours and goes on to finish with lines.

His themes often required meticulous research. After research, he created the entire painting with the all details in his mind. He started off the paintings with a pencil outline depicting the central figure. The actual painting is done around this central figure thereby creating the required depth.

(ii). The medium used by Shri Rajam is watercolor on cured plywood, veneer, handmade paper and silk (not the mulberry silk but the tussar silk, the non- violent silk, at the suggestion of The Paramacharya of Kanchi). It is said that in his earlier days Shri Rajam made the paper himself. As regards silk, he says one has to be very careful while painting on silk, because mistakes and wrong lines cannot be corrected or erased easily.

(iii).He used layers of transparent colors. Each color is applied only to be washed away with water using a brush. Upon drying the next layer is applied and washed away. It is this series of washes and the combination of the colors that eventually gave the desired color scheming that was originally envisioned. After the application of the transparent colors, the opaque colors are applied over it. Finally, his characteristic ink outlines (rekhas) were done using a Fine liner pen.

Each painting of his will have about 25 layers of colour; and will be washed ten to twelve times before it is completed. His technique involves washing the paper by dipping the brush in plain water and dabbing it all over the painting. This he does every time after applying a couple of layers of colour. “Do you know why I do it,” he asks. “It is to remove the excess colours from the painting. Only the subtle brush strokes and effects remain and all that is garish is washed away. Do you know I lose more than 30 per cent of the paints this way? It is a loss. But my painting will survive without problems and its life will be as long as the medium on which I do it”.

(iv) . Shri Rajam calls this process “water-wash”, which according to him is an oriental technique, unique to Indian and Chinese painting. The Chinese method, he says, is also the same but the number of washes is not as many as in the Indian method. He explains, “A wonderful quality of this oriental wash technique is that the painting can be washed in water and no colours will come off except the final touches of tempura colours “.

(v) . He says, such repeated washing –treatment helps the colour stay on the surface and last longer, because through the process, all the colours are absorbed by the handmade paper on which the pictures are painted. Luckily, the handmade, rag paper etc. that he uses can withstand his water-wash treatment. Not only that, strangely the paintings do not smudge and they emerge all the more beautiful after being subjected to water- wash.

(vi). He uses transparent watercolor while building the layers, and applies opaque colours in the final stages of highlighting and finishing. As colours are applied from light to dark, it enables the undertones of previous colours to be visible. This gives, according to him, a misty and toned effect suitable to portray the imaginative subjects.

(vii). The process is laborious and takes nearly ten washes and about a week to ten days to finish a painting. But, he says, it worth doing it because the method ensures that colours last longer and stay bright. And, even in case the painting gets wet, the colours remain unaffected.

Clearly, this technique requires immense patience and (depending on the size) each painting can take from a few weeks to a few months for completion. It was Rajam’s disciplined approach and incredible ability to multitask that allowed him to simultaneously work on several paintings. It was his capacity to quickly mentally switch from one theme to the other, as the paintings were drying, was the main reason for the volume of work he could produce.

(viii). Shri Rajam recommends that the watercolors be preserved behind glass and ensured that no fungus develops between the painting and the glass.

7. Phenomenal output

(i). Considering the volume of study, research and work involved; and the time taken to complete a painting, the prodigious output of Shri Rajam is totally amazing. For this scholarly-painter phenomenon who has entered his nineties, his work is his worship. His zest for work is enormous; and says he is “just beginning”. Even at his age, he is as inspired and enthusiastic about his work as he was in 1940 when he took to painting seriously; and he is no less prolific. Shri Rajam now in his nineties paints for about three to four hours every day. Art and music are his passions and they keep him young.

(ii). His art work has adorned several books .The paintings produced by him over the years, I reckon, run into a few thousands. I am not sure whether either Shri Rajam or anyone else has kept a count of his artistic output. Some of his works have also been compiled as books. Notable ones are the Chitra Periya Purana – depicting the legends of the 63 Nayanmars and the Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam – depicting the 64 divine plays of Shiva. Another book titled “Dancing with Shiva” published by the Himalayan Academy, Hawaii , USA has over 300 hundred works of Rajam reproduced with exemplary production value .

Pl see: –

http://www.lntecc.com/homepage/resources/brochures/Sustainabiltiy/ArtHeritageBook.pdf

http://www.lntecc.com/homepage/documents/panchangam/2008_09.pdf

http://www.lntecc.com/homepage/documents/panchangam/2007_08.pdf

http://www.lntecc.com/homepage/documents/panchangam/2006_07.pdf

Pocket Booklet of 72 Melakarta Ragas

‘A Confluence of Art and Music’ – http://www.carnaticdarbar.com/news/201102/20110714.asp

http://www.carnaticdarbar.com/news/201102/20110713-Melakartha-Raga-Booklet.pdf

(Please see www.HimalayanAcademy.com)

It is said , the Himalayan Academy Publications has scanned 923 of Shri Rajam’s creations. Please click here for the web-page:

https://www.himalayanacademy.com/hamsa/index.html?artist=S.%20Rajam&view=Collection

Apart from that, as I understand, there have not been serious attempts to put together a sizable number of his paintings. There have not been many formal exhibition of Sri. S. Rajam’s works either, except perhaps the one held in Los Alamos, NM, USA in 1981.

(iii). The arrays of subjects chosen by him are vast and diverse. They range from the gods, goddesses, demons, Vedic sages, characters from puranas, literature, history, planetary deities, music composers, Nayanmars , Thirthankaras and Acharyas of various periods and inclinations ; festivals , fine arts folk arts and so on and on.

(iv). His works are distributed over book- covers, countless magazines published in various languages, book illustrations, compilations, chronicles, life histories etc. Yet, he feels he has not done quite enough and could have done more; “There is so much more I can do” he rues even at ninety.

(v). Anyone, even vaguely familiar with his paintings cannot help but wonder how a person, amidst his various interests , pursuits and preoccupations in life, could achieve so much in various other fields of his activities and yet produce countless sublime and soulful precious works of art .. And, all that in one life time…!

(vi). That was the genius called Acharya Shri S Rajam, the very incarnation of the Vedic seers he admired and adored.

Resources & References

Chitrasutra

http://ssubbanna.sulekha.com/blog/post/2008/12/the-legacy-of-chitrasutra-one.htm

S Rajam

http://www.carnatica.net/mmmela2001/srajam.html

http://www.vidvan.com/painters/rajam/index.htm

An afternoon with S Rajam

http://archives.chennaionline.com/musicnew/carnaticmusic/2004/319th.asp

http://archives.chennaionline.com/musicnew/carnaticmusic/2004/324th.asp

Aesthetic and faithful depiction of character

http://www.hindu.com/fr/2004/05/21/stories/2004052101920700.htm

Visual poetry

http://www.hindu.com/fr/2008/05/16/stories/2008051651090100.htm

Ajanta Cave Paintings

http://www.indian-heritage.org/ajindex.html

https://carnaticmusicreview.wordpress.com/2018/09/17/s-rajam-the-painter/

All the pictures of Shri Rajam are from internet

S Rajam’s favourite composer is Koteeswara Iyer (January 1870 – October 21, 1936) popularly known as Kavi Kunjara Dasan. “I am deeply interested in Koteeswara Iyer’s compositions” S Rajam said, ” I do not compare any other composer with him, I find great pleasure in singing his compositions”. Koteeswara Iyer was the first composer, after Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar, who composed krithis in all 72 Melakartha-ragas. His monumental work, “kanda ganamudam” has songs, in praise of Lord Muruga, composed in all the 72 Melas. The songs are in chaste Tamil .

S Rajam’s favourite composer is Koteeswara Iyer (January 1870 – October 21, 1936) popularly known as Kavi Kunjara Dasan. “I am deeply interested in Koteeswara Iyer’s compositions” S Rajam said, ” I do not compare any other composer with him, I find great pleasure in singing his compositions”. Koteeswara Iyer was the first composer, after Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar, who composed krithis in all 72 Melakartha-ragas. His monumental work, “kanda ganamudam” has songs, in praise of Lord Muruga, composed in all the 72 Melas. The songs are in chaste Tamil .

![10[1]](https://sreenivasaraos.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/1012.jpg?w=645)

![14[1]](https://sreenivasaraos.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/1412.jpg?w=645)

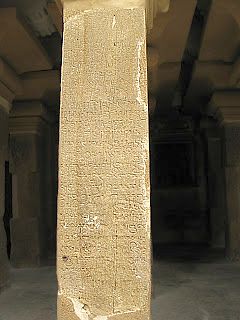

Hail Vikramaditya –sathyashraya, the favourite of Fortune and of earth, Maha-rajadhiraja Parameshwara Bhattara having captured Kanchi and after having inspected the riches of the temple, submitted them again to god of Rajasimheshwaram.

Hail Vikramaditya –sathyashraya, the favourite of Fortune and of earth, Maha-rajadhiraja Parameshwara Bhattara having captured Kanchi and after having inspected the riches of the temple, submitted them again to god of Rajasimheshwaram.