Sri Shyama Shastry – Life

Name

The person who is celebrated as Sri Shyama Shastry was named, on his birth, as Venkatasubrahmanya; and, was fondly called Shyama Krishna by his parents Visvanatha Iyer (Visvanathayya, Viswanatha Sastry) and Venkalekshmi (Vengu-Lakshmi). The ‘Venkata’ in his name referred to his grandfather Venkatadri Iyer; and, ‘Subrahmanya’ was because he was born under Krittika Nakshatra, presided over by Lord Kartikeya (Subrahmanya). Since the baby was dark in complexion; but, lovely to look at , like Krishna, he was affectionately called Shyama Krishna.

And, later in his life, after he gained fame as an Uttama Vaggeyakara, composer par excellence, he came to be recognized and addressed as Sri Shyama Shastry. And, Shyama Krishna was his Ankita-Mudra (signature) built into the concluding lines (Birudu) of the Charana of his Kritis and other compositions, either by himself or by his disciples, at a later stage, perhaps to conform to the practice that had then into vogue, as Sri S Raja, his descendant remarked.

Birth

In most of the books and the other forms of writing, the date of birth of Sri Shyama Shastry is mentioned as 26 April 1762 C E. In terms of the Panchanga for that date, it works out to Salivahana-Shaka-Chitrabhanu-Samvathsara-1684, Vaishakha-masa, Shukla-paksha, Dwitiya/Akshaya-Tritiya, Indu-vara (Monday), with Krittika Nakshatra up to 11.06 A.M.

However, Sri Subbarama Dikshitar, in his monumental work Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini, under the segment Vaggeyakara Caritam (pages 14/15) mentions that Sri Shyama Shastry was born in the year 1763 C E, in the Saka-Savathsara Chitrabanu, under Krittika Nakshatra, Mesha Rasi on Ravi-vara (Sunday). This almost corresponds to 20 February 1763 – Saka-Savathsara-1684-Chitrabanu; Phalguna-masa, Shukla-paksha-Sapthami- Krittika Nakshatra up to 5.30 A.M. next day-Mesha Rasi – Sunday.

Prof. Sambamoorthy has also accepted and adopted 1763 as the year of birth of Sri Shyama Shastry.

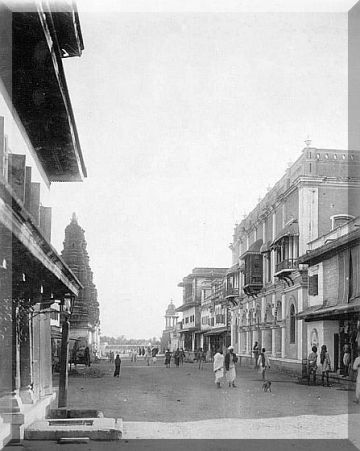

Sri Shyama Shastry’s birth took place at the sacred town of Tiruvarur, also known as Sripuram and Kamalaalaya-khsetra (the abode of the Goddess kamalamba), in the Kaveri delta through which the Odambokki River flows.

Tiruvarur has the unique distinction and honor of being the birthplace of Sri Thyagaraja, Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar and of Sri Shyama Shastry – the Grand Trinity – the Samgita Trimurthi of Karnataka music tradition.

The forefathers

The forefathers of Sri Shyama Shastry were described as Auttara-Vada –Deshastha-Vadamal (Northern) Smartha Brahmins. They belonged to Gautama Gotra; Bodhayana-Sutra.

It is said; they originally belonged to a place called Cumbam (Kambham) in the Karnool District of Andhra Pradesh; and, were hence called Cumbattar, the priests (Bhattar) from Cumbam. Later, they migrated to Kâñchipuram, located on the Vegavathy River, in Chingleput District. Here, they were appointed as the priests (Archakas) at the Sri Kamakshi temple; wherein was placed the most precious idol, Bangaru Kamakshi (Svarna Kamakshi), made largely out of gold.

*

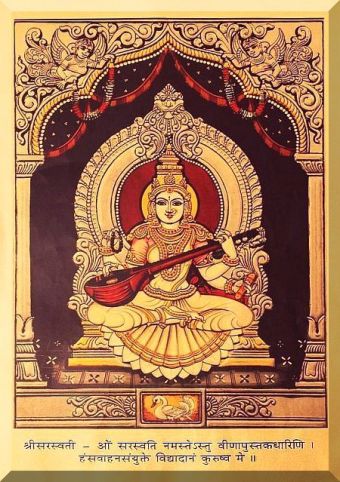

Bangaru Kamakshi

This most pleasing and lovely looking Bangaru Kamakshi , the golden Utsava–Vigraha of Kanchi Kamakshi, very dear to the devotees, was praised with many epithets, such as: Svarnangi, swarnambika Shukahastha, Suthlinga-vallabha and Dharma-Devi, etc.

The Devi is depicted as holding a parrot in her right hand (Shukahastha), while her left hand is slightly over her hip, is standing (Sthanaka) gracefully assuming a Tri-bhanga posture with her right leg turned slightly inward.

But, with the fall of the Vijayanagar Empire in 1565, Kanchipuram suffered severe unrest, political turmoil and anarchy for a period of over two decades. By about 1640, the town fell to the Muslim sultanate of Golconda; but, three years later, they lost it to the Shaws of Bijapur. The Golconda Sultanate regained Kanchipuram in 1676, mainly due to the intervention of Shivaji Maharaj. And again, with the conquest of the Mughals led by Aurangzeb in October 1687, the Golconda rulers were driven out. And, anarchy prevailed , pestering the region for a long time; causing considerable damage to the city of Kanchipuram.

Fearing rampage , damage and destruction to the temple and to the idols by the Muslim hordes, the Archakas buried the temple-treasures, concealed in the temple Drums (Udal) ; and, left Kanchipuram, in the year 1566, along with their families , in groups, carrying with them the most valuable and sacred image of Bangaru Kamakshi and the Chaturbhuja Utsava-vigraha..

*

It seems the idol of Bangaru Kamakshi was virtually smuggled out of the Kanchi-temple by a set of priests. The image was wrapped in layers of cloth; and the shiny surface of the image was smeared with Punugu (Civet-oil-cream), an aromatic substance, which is black in colour. And, the image, rendered dark; made to look like a sick child affected with small pox, was placed in a covered palanquin; and, was taken out , as if for medical treatment.

[Even to this day, the idol is regularly smeared with Punugu paste; and made to appear dark.]

After the Bangaru Kamakshi was shifted out, a replica of her feet (Paduka) was symbolically installed at the temple.

Migration and wandering

Over the next several decades spread over a couple of centuries, the generations after generations of the Kanchi–Archaka-families wandered, almost like nomads, fleeing from forest to forest, from town to town protecting, safeguarding and worshiping Bangaru Kamakshi, with great devotion and care.

After leaving Kanchipuram, the Archaka-families for some time stayed hidden in the forests , out of sheer fear; and, wandered through several forests thereafter, over a period of twenty-eight years, before they reached and settled down at the Gingee Fort (Chenge-Kota), in 1594, at the invitation of its ruler Santana Maharajah.

After a stay of fifteen years at the Gingee fortress, the Archaka-families moved southwards (1609); and, stayed in the nearby forests for another fifteen years (1624).

Thereafter, in 1624, the Archaka-families settled in Wodeyara-palya, situated in the heart of the forest adjoining Gingee. The area was then under the rule of Thanjavur Maharaja Sri Pratapah Simha.

Here, at Wodeyara-palya (Udiyar-Pallayam), the community of the Archakas stayed for as long a period as seventy years, till 1694.

And, after staying in Anakkudy (near Kumbakonam) for a period of 15 years (1709), they moved along with Bangaru Kamakshi to the town of Vijayapuram, where they spent another fifteen years (1724). From Vijayapuram they passed through Nagore, Madapuram and Sikkil, staying in each place for a period of five years (till about 1739).

Their primary objective was to safeguard Bangaru Kamakshi; and, ultimately, somehow, to take her back to her original abode in Kanchipuram, safely; and establish her there.

At Tiruvarur

Thereafter, the then generation of Kanchi-Archakas moved in to Tiruvarur, where they stayed for a long period of forty-five years (till about 1784). And, at Tiruvarur, the idol of Bangaru Kamakshi was kept in a specially arranged Mantapa, within the complex of Sri Thyagaraja-swami temple.

It was here while in Tiruvarur, Sri Visvanatha Shastry, the then head of the Archaka-family, and his wife Venkalekshmi (Vengu-Lakshmi), were blessed with a son in about the year 1763. They were at that time, 25 years and 20 years of age. And, the boy born at Tiruvavur later gained great fame as Sri Shyama Shastry. Sri Visvanatha Shastri couple later got a daughter; and, named her as Meenakshi.

By about the year 1781, the Kaveri delta again came under the threat of impending invasion; and, this time by Hyder Ali and his allies. Sensing danger that might harm Bangaru Kamakshi, Sri Visvanatha Shastry approached Tulaja Raja II Saheb Bhosle (1765-1787) the then ruler of Thanjavur, with a request to provide safety and protection to Bangaru Kamakshi within the walls of his fortress. Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati Swamigal – V (1746-1783 AD) also approved the request.

[Those were stressful times. Because of the uncertain political conditions and the impending threat of invasion by the Muslims, Kanchipuram was not deemed safe. Hence, the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham had moved out of Kancipuram. And, after prolonged camps at several places, by about 1760, it moved to Thanjavur at the invitation of its ruler Raja Pratapa Simha. But, shortly thereafter, the Acharya Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati-V decided to relocate the Peetham at Kumbhakonam , far down South, on the banks of the Kaveri.

By about 1781, Kanchipuram was again under the threat of invasion. During that time, Thanjavur under the Maratha rule was relatively a safer place. Hence, many scholars, musicians, artists and others who felt threatened by persecution migrated to Thanjavur from Mysore, Andhra, Maharashtra and other regions of South India.]

At Thanjavur

After the King acceded to Sri Visvanatha Shastry’s request, the family shifted from Tiruvarur to Thanjavur in about the year 1783/84. By then, Shyama Shastry (born 1763) had grown into a bright young man of about twenty years; and, was on the threshold of his life. And, his Upanayanam had earlier been conducted in Tiruvarur while he was a boy of seven years of age.

At Thanjavur, the idol of Bangaru Kamakshi was initially housed in the Nataraja Mantapa of Konkanisvara-Svami Temple. And, later for about three years it was kept in the Pratapa-Veera-Hanumar temple (Moolai Hanumar Kovil).

During the time of Raja Tulaja II a new temple for Bangaru Kamakshi was built in about 1786/7. Later, a Raja-gopura was caused to be constructed by his successor Serfoji II in 1788.

On the occasion of the Kumbha-abhishekam of the newly built temple, the Raja honoured Sri Visvanatha Shastry; and gifted him with a Jahgir (free leasehold over a large extent of land) including an Agraharam and cultivable lands He also granted the temple an endowment of thirty-two Velis (acres) of land as Sarvamanyam.

*

Thus, Bangaru Kamakshi, the Uthsava-Vigraha of Kanchi Kamakshi, after having moved out of Kanchipuram in the year 1566, wandered over hills, dales, forests, towns and villages for nearly over two hundred and twenty years , before she could have a permanent temple of her own at Thanjavur in 1786 . But, even after a very long and hazardous journey, she could not get back to her original home in Kanchipuram.

Nevertheless, the devotion, dedication and the sacrifices made by several generations of Kanchi Archakas in safeguarding their Dearest Goddess is truly admirable and astounding. I doubt if there is a parallel anywhere and at any time in this world.

Early Years

Sri Shyama Shastry had his initial training in Telugu and Sanskrit from his father. His Upanayana was performed at the age of seven. He got his preliminary lessons in music from his maternal uncle; and, starting from Sarali-svaras he gained familiarity with Svaras (Svara-jnana). He was a bright young lad; quick to grasp; and good at retaining what he had learnt. He was also gifted with a sonorous voice. Though he did not come a family of musicians; his parents did not discourage his study and practice of music.

Sri Shyama Shastry, even in his boyhood, was of pious nature. At home, he and his sister Meenakshi together decorated and rendered Puja to a Pancha-loha image of Krishna. It appears the siblings, who grew up together, were very close and affectionate to each other. The sister died rather early in her life. Sri Shyama Shastry often recalls her lovingly, tagging her along with his Ankita–Mudra Shyama-Krishna, with expressions such as ‘Shyama-Krishna-sodari’ and ‘Shyama-Krishna-sahodari’.

*

Sri Shyama Shastry, later in his life, gained fame as an eminent musician, scholar and Sri Vidya Upasaka; but, his formal training in these fields began rather late.

It was only after his family moved to Thanjavur (in about 1783-84) that the life and career of Sri Shyama Shastry began to blossom and flower. It all started after he was about twenty years of age.

As his father was the Archaka at the Bangaru Kamakshi temple, he began to associate himself with the Devi Puja and other temple-rituals. And, he also did develop a sort of a bond with the Goddess, regarding her as his Ista-devatha and his Mother. Sometimes he used to sing to her in sheer joy with his impromptu songs of playfulness and attractive Laya patterns.

Sangita Swamin

The momentous turning point in Sri Shyama Shastry’s life came about with the very fortunate and blessed entry of Sangita Swamin .This Swamin was an adept in Samgita-shastra and Bharatha-shastra. He was also an ardent Sri Vidya Upasaka.

Sangita Swamin, who came from the Northern regions, was said to be a Telugu speaking Brahmin itinerant (Parivrajaka) Sanyasin. During the year 1784, for the purpose of his annual Chaturmasya-Deeksha period of retreat, he had camped in Thanjavur. And, it was here that he came upon the bright looking youth – Shyama Shastry; and, was instantly impressed with his demeanour, his pious nature, guileless devotion to the Mother Goddess, and his innate musical talent of a very rare kind. He took upon himself the task of training and guiding the young Shyama Shastry.

[Sri Subbarama Dikshitar mentions that the training period lasted for three years. However, according to Prof. Sambamoorthy, Sangita Swamin was with his pupil only for four months of Chaturmasya period.]

According to Sri Subbarama Dikshitar, Sri Shyama Shastry was under the tutelage of Sangita Swamin for a period of about three years. During this intense, invigorating and highly charged phase of his life, Sri Shyama Shastry was initiated by Sangita Swamin into the mysteries of Sri Vidya and the worship of Sri Chakra.

Sangita Swamin also taught his disciple all the intricacies of the Lakshana (theoretical principles) and in-depth understanding of the elements of the Lakshya (practice) of the Samgita-shastra, such as the prastara-krama, the appropriate manners of rendering of Sahitya, Raga and Taala.

At the conclusion of the teaching-period; and, before departing for Varanasi, Sangita Swamin, highly pleased with his disciple, while gifting him some very valuable Lakshana-granthas – the texts concerning music (Gandharva-vidya) – blessed him; and, predicted that he was destined to become a very illustrious noble person, blessed by Sri Kamakshi Devi.

Pachchi-mirium Adi-Appaiah

Further, Sangita Swamin also advised his pupil saying: that you have learnt enough of the Lakshanas as per the Samgita-shastra (theoretical aspects of Music); and, it is now the right time to listen to as many of the fine musicians of the area as possible. And, the Swamin suggested that he might cultivate the friendship of the musician (Asthana-Vidwan) of the Thanjavur Royal Court (Samsthanam), Sri Pachchi-mirium Adi-Appaiah; and, carefully listen to his scholarly music as often as possible.

[Sri Pachchi Mirium Adi Appaiah (1740-1833), a Kannada Madhwa Brahmin, was a scholar and composer of great repute. He was consulted on various aspects of musicology by none other than Sri Thyagaraja himself. Sri Adi Appaiah followed the great musician Melathur Veerabhadriah; and composed several Kritis in many Rakthi-ragas. His Aknita-Mudra was ‘Sri Venkataramana’.

It is said; the Raga-alapana and Madhyama-kala-Pallavi rendering (paddhati) were standardized and gained greater importance mainly because of him. He was also well versed in Taala-prakaranam and in analyzing complicated Gamaka patterns. His Bhairavi Ata-taala Varnam Viriboni is, of course, a classic.

Though Sri Shyama Shastry did not directly study under Sri Adi Appaiah, some point out that he analysed the compositions of Adi Appaiah; and this greatly influenced his style, as could be seen in his famous Svarajati in the Raga Bhairavi, ‘Kamakshi-amba’.]

[It is said; Sri Shyama Shastry learnt playing on the Veena and the elements of Bharata-shastra from Mahadeva Annavi, a reputed Natyacharya in the Royal Court of King Tulaja II of Thanjavur. This Mahadeva Annavi was, in fact, none other than Subbarayan, the father of the famed Tanjore-Quartet – Chinnaya; Ponnayya; Sivanandam; and, Vadivelu. The four brothers, later, became the ardent disciples of Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar. ]

*

As instructed by his Guru, Sri Shyama Shastry did meet Sri Adi Appaiah. And the two became great friends, despite the difference in their age, their standing in the society; and, in the field of Music.

In the year 1784, Sri Adi Appaiah was about 45 years of age; and, Sri Shastry was a young man of about 20 years. And, at that stage, Sri Adi Appaiah was a highly acclaimed scholar and an authority on Lakshana aspects of Music; and, was also a well-known composer. While, at that time, Sri Shastry was a young person with hardly any background of music; and, who was just then gingerly stepping into the main arena of Music. And yet, there was a great mutual respect and admiration between the two.

Sri Shyama Shastry also made friendship with Vina Krishnayya, the son of Sri Adi Appaiah. And, the two used to spend a lot of time together singing and analyzing music. Vina Krishnayya was also a famous composer and an accomplished Veena player. Sri Shyama Shastry appreciated a composition of Krishnayya, which was set in 30 Avartas of Dhruva-taala, but could be rendered in six other Taalas.

In that regard Sri Subbarama Dikshitar mentions that Vina Krishnayya had composed three Prabandhas of the type Saptalesvarm. The unique feature of this composition was that though it was set in Dhruva-taala, it was in conformity with the six other Taalas. And, when the commencing part of the Prabandha is sung, the fist beat (Matra) of all the Taalas coincide.

As Archaka and musician

In due course, Sri Shyama Shastry succeeded his father as the principal (Pradhana) Archaka of the Bangaru Kamakshi temple; and, was quite successful in managing the temple affairs.

By then, he was fairly well settled in life; and, had a steady income from the large tracts of lands endowed to his family by the Kings of Thanjavur. He seems to have enjoyed a contented peaceful life with his family. Sri Shyama Shastry’s wife was a very caring and a devoted person. She was also a Devi-Upasaki; and observed the same discipline and principles that her husband followed.

He had a house of his own. And also had enough income to take care of his family and other needs; and, was not caught up in the mesh of financial and such other problems. That might perhaps be one of the reasons why he did not go after seeking patronage, honors and gifts etc. He was also not in need of using his expertise in Music as a means for earning a living. He was also rather reluctant to accept many disciples, for other reasons.

Over the years, Sri Shyama Shastry became a well-known and a highly appreciated musician, scholar and a composer. He was admired and respected by the King as also by his worthy contemporaries like Sri Thyagaraja and Sri Dikshitar. He did maintain contacts with the other two of the Trinity; and often discussed about their latest compositions.

Intense devotion

At the same time, with the growing association with the deity, Sri Shyama Shastry developed a uniquely profound mystical bond with his Ista-devata, the Bangaru Kamakshi, treating her like a person, a living goddess (Pratyaksha-devata) in whom he could confide as a child does with its loving Mother. He was charged with intense devotion and a poignant longing for the Mother

It is said; he would spend much time with the deity, talking to her; pouring his heart out in guileless love through songs, spontaneously; imploring (karuna-bhava) her repeatedly to protect him – Kamakshi Bangaru Kamakshi nannu brovave, O Kamakshi Bangaru Kamakshi.

At times he would, oblivious to the outside world, converse with his Divine Mother, pleading with her, and cajoling her with sweet-sounding songs.

He called out to Her in ecstasy through countless other epithets, as :

Amba; Jagadamba; Talli, Katyayani; Kaumari; Kalyani; Himadrisute; Akilandeswari ; Lokasakshini ; Brihannayaki; Indumukhi; Kunda-mukundaradana; Bangaru-bomma; Bimbadhara; Niradaveni; Saroja-dala-netri; Meenanetri;Meena-lochana; Sarasija-bhava-hari-hara-nuta; Mavani-sevita; Dharma-samvardhini; and, Ahi-bhushana-pannaga-bhushana ; and so on.

*

Sastrigal was as great a Bhakta ; and, his Vairagya was firm as that of Sri Dikshitar. In piece after piece, Sastrigal affirms faith in the Goddess and her compassion.

In a Todi piece Vegamevacchi, he echoes Sri Tyagaraja’s Dhyaname Varamaina ; and, says that beyond the Mother’s Dhyanam, he knows no mantra or tantra.

But one supreme quality that Sri Syama Sastri achieved by the simplicity of his Sahitya is the directness of appeal. You see in his songs one directly speaking to Mother.

In songs like Brovavamma (Manji) or Marivere (Anandabhairavi), one cannot help being placed in the very presence of the Goddess. The simple repetitive addresses Janani, Talli, Amma, Ninnuvina Gati, Namminanu ; and, sometimes repetitions of words like Nammiti Nammiti twice and even thrice, and the not infrequent use, in effective places, of the address – syllable “O” singly or in repetition, will not fail to transport one to the very ineffable presence of the Mother.

Such poignant expression of simple feeling more readily opens that inner well of the tears of bliss than the thought-laden composition, which takes you through long cerebral prakara-s.

*

On Fridays and on other occasions specially associated with the Mother Goddess, he would sit in front on the Deity, immersed in Sri Vidya Upasana, meditating on her sublime and supreme Divine form, with tears rolling down his cheeks. During those intense moments of transcendental experience, he sang many melodious songs in sheer ecstasy. Thus, over a period, Sri Shyama Shastry was transformed almost into a spiritual personage.

Person

Sri Shyama Shastry was a dark, tall, well-built, handsome, serious looking person, rather absorbed in himself. And, he had a slight rotund around his waist. He was indeed a very impressive personality. His very presence commanded respect.

Sri Shyama Shastry was a Devi Upasaka; and was a deeply religious person who adhered to the prescriptions of the scriptures. He always had a dash of vermilion (Devi-prasada) right between his eye brows and stripes of Vibhuthi across his broad forehead. He sported a tuft (Kudumi); and, appeared with stubble on his chin, because he shaved only once in a fortnight, just as an orthodox Brahmin would do.

He was always dressed in a gold-laced (zari) white dhoti; and, a bright red shawl as the upper garment (uttariya). He habitually wore sparkling diamond karna-kundalas on his ear lobes; gold studded Rudraksha-mala around his neck; and, wore rings on his fingers. He carried a cane with a silver handle.

He was fond of chewing betel leaf (paan); and, his lips were dark red. He, therefore, is usually shown in his portraits along with a paan petti, a small box to hold leaves and nuts, by his side

Sri Shyama Shastry’s Tambura had a yali-mukham; not usually found in other Tambura depictions.

The portraits of the Karnataka Samgita Trinity created by Shri S Rajam, a celebrated Musicologist and painter, are universally acclaimed archetype iconic figures; and, are even worshiped. He studied and researched into his subjects thoroughly; and, grasped the essence of their character and achievements. His portraits therefore bring out not mere the physical resemblance of the subjects, but more importantly the essence of their very inner being.

His portrait of Sri Shyama Shastry was based upon an old sketch that had almost worn-out. Shri Rajam’s portrayal is the best among its genre. It brings out the colorful personality of Sri Shastry brilliantly. His portrait of Sri Shyama Shastry eventually turned into an Indian postal stamp.

Sri S Raja, a descendent of Sri Shyama Shastry, narrates, about the old and original portrait of Sri Shyama Shastry that was in his family.

There is the story of the portrait of Shyama Sastri. Its original portrait is in my possession; and, it is the only original from which all published portraits have been derived.

On the 7th February, 1827, seven days after his wife had dies, he knew through his knowledge of Astrology that he had reached the last day of his life. This prompted him earlier that day to send for a friend of his who was a good painter, and asked him to draw a portrait of himself.

His friend agreed and commenced the portrait. But after drawing Shyama Shastri’s face, his friend decided to complete the portrait another day.

Little did he realize that this was not to be, as Shyama Shastry would pass away later that day, and the picture would have to be completed from memory later.

The original portrait so completed is reproduced here, and has suffered fading and erasure in parts in the centuries that have since gone by.

But what is of interest here is that the small original drawing of the face has been stuck on a larger sheet on which the rest of the detail has been added. The original drawing can be seen clearly demarcated as a rectangle on the portrait so completed.

Association with his contemporaries

Sri Shyama Shastry maintained close contact with Sri Thyagaraja as also with Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar.

He often used to call on Sri Thyagaraja at his home in Tiruvaruru; and, spend much time with him, discussing about Music and related issues.

Sri Thyagaraja was also familiar with the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry. It is said; some disciples of Sri Shyama Shastry while on a visit to Tiruvarur rendered the compositions of their teacher before Sri Thyagaraja.

Sri Subbaraya Shastry, the second son of Sri Shyama Shastry also used to meet Sri Thygaraja; and sang before him one of his newly composed kritis – Ninnu-vinagatigana (Kalyani). Sri Thyagaraja appreciated the young man’s talent.

Then, for some time, Sri Subbaraya Shastry was a student of Sri Thyagaraja; before he associated with Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar.

Sri Shyama Shastry and Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar had much in common. They were both Sri-Vidya-Upaskas; and, by nature, both were rather recluse and reserved. Most of their compositions were in praise of the Devi, the Mother Goddess.

Sri Shyama Shastry was familiar with the compositions of Sri Dikshitar; and, admired them for their structural elegance, beauty of the Sahitya and their intensely close association with Sri Vidya.

And, Sri Shyama Shastry liked the compositions of Sri Dikshitar so much, as he put his son Subbaraya Shastry under him for training in Music.

Thus, Subbaraya Shastry gained fame as a composer of superb Kritis that reflect the rhythmic beauties of Sri Shyama Shastry as also the Raga richness of Sri Dikshitar.

***

Justice T L Venkatarama Aiyar mentions that Chinnaswami and Baluswami often used to visit their elder brother Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar at Thanjavur. And, and on such occasions all of them and Sri Shyama Shastry used to associate themselves in Music recitals.

He mentions that on one such occasion, all of them combined to restructure and complete a Chowka-varnam – Sami Ninne Kori – in Raga Sriranjani, that was earlier composed by Sri Ramaswami Dikshitar.

[The Chowka-varnams are usually set in slower tempo (Chowka-kalam); and, have longer lines and pauses, enabling apt portrayal of the Bhava of the Varnam . All its Svaras are accompanied by Sahitya (lyrics) and Sollukattus which are made up of rhythmic syllables.]

The Carana of that Chowka-varnam had only one Svara passage as composed by Sri Ramaswami Dikshitar; while its others Caranas seemed to have been lost. Sri Shyama Shastry felt that as good piece as that should not be allowed to die merely because it is incomplete. And, therefore, he himself composed the second passage of Svaras; and, then called upon Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar and his brother Chinnaswami to duly complete the Varna. Thereafter, Chinnaswami composed the third passage; while Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar composed the fourth and the last passage; and, perfected the composition that was initially created by his father.

This association of Sri Shyama Shastry and Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar in Thanjavur is one of the most fascinating episodes in the history of South Indian Music.

Anecdotes

There are numerous anecdotes associated with Sri Shyama Shastry. And, just to recount a few, in brief:

Once, Kesavayya, a famous musician from Bobbili (who had arrogated to himself the pompous title – Bhoolaka-chapa-chutti – the one who rolled the world into a common mat) challenged the Thanjavur Court musicians in the handling intricate Taalas. He was known to be an expert in that field.

Sri Shyama Shastry was requested by the King to face Kesavayya and to defeat him; saving the prestige and honour of the Thanjavur Court.

Before facing him, on the night previous to the contest, Sri Shyama Shastry shut himself in the temple, meditated, prayed devotedly to Bangaru Kamakshi pleading with the Mother come to his rescue; and, sang the now-famous “Devi-brova-samayamide’ (Chintamani Raga, Adi Taala), “Devi ! Now it is the time for you to protect me”.

The contest ended with Sri Shyama Shastry winning it handsomely, when he outclassed the challenger by displaying his virtuosity and creativity in rendering varied types of rare Tanas with great ease and delight.

*

And again at Nagapattinam, Sri Shyama Shastry is said to have defeated the challenger Appukutti Nattuvanar who was proficient in Music and Dance.

*

While on a Visit to Pudukottai, an unknown person suggested to Sri Shyama Shastry to have a Darshan of Devi Meenakshi of Madurai; compose and sing songs celebrating her glory and splendour.

Accordingly, Sri Shastry went to Madurai, sat in front of Meenakshi Amman and composed a garland of gem-like nine splendid Kritis – the Nava-ratna-malika, exuding Bhakthi-rasa, composed mostly in Rakthi-ragas , set to alluring rhythmic structures and adorned with ornamental Angas like Gamaka, Chittasvara, Svara-sahitya and rhetorical beauties like Yati, Prasa etc.

These include most delightful Kritis dedicated to Devi Meenakshi, such as:

-

- Saroja-dala-netri (Shankarabharanam),

- Mariveregati (Anandabhairavi),

- Devi-Meenanetri (Shankarabharanam),

- Nannu-brovu-Lalita (Lalita),

- Devi-ni-pada-sarasa (Kambhoji),

- Mayamma (Natakuranji),

- Mayamma (Ahiri) ,

- Meena lochana-brova (Dhanyasi) , and

- Karuna-chupavamma (Sri).

*

Descendents

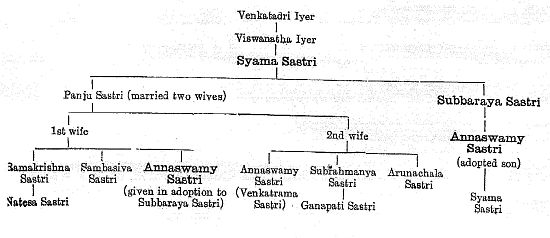

Sri Shyama Shastri had two sons: Panju Shastri and Subbaraya Shastri. Each, in a way, continued the legacy of Sri Shyama Shastri.

After the demise his father, Panju Shastri was appointed as the Archaka of the Bangaru Kamakshi Temple; while Subbaraya Shastri pursued Musical career on the lines of his father.

**

***

Panju Shastri had two wives and six sons. By the first wife, he had three sons: Ramakrishana Shastri, Sambasiva Shastri and Annaswami Shastri.

Ramakrishna Shastri’s son Natesha Shastri succeeded his father as the Archaka of the Bangaru Kamakshi temple. Natesha Shastri is said to have safeguarded several valuable and rare manuscripts prepared by Sri Shyama Shastri on the theory and practice of Karnataka Samgita. These related particularly to Taala-prastara, illustrated with the help of diagrams, the sixteen elements (Shodasanga) of the Prastara Krama.

The second son Sambasiva Shastri was a reputed scholar, well versed in Vedanta.

The third son, Annaswami Shastri., was given in adoption to Subbaraya Shastri, since he was childless.

*

As regards the sons from the second wife of Panju Shastri, they also were three in number. The eldest Annaswami Shastry and the youngest Arunachala Shastri died rather young and childless. And, the middle-son, Subrahmanya Shastri and his son Ganapathi Shastri lived in Thanjavur.

Subbaraya Shastri

Subbaraya Shastri (1803-1862), the second son of Sri Shyama Shastri, followed the footsteps of his father; and, developed into a renowned composer and scholar.

He indeed had the great fortunate and unique distinction of having been trained in Samgita-Shastra by all three Grand Masters of the Karnataka Samgita: his father Sri Shyama Shastri, Sri Thyagaraja and Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar. His compositions are often described as the Tri-veni-sangama, the confluence of the unique features of the Kritis his three Gurus, the Trinity. ‘Kumara’ was his Ankita-Mudra.

Subbaraya Shastri has composed more than 40 Krtis. But only a few Krtis are available now. And, most of those Krtis are in praise of the Mother Goddess.

His krtis are also adorned with decorative Angas like Svara-sahitya, Madhyamakala Sahitya etc,; and with literary devices like Dvitlyakshara and Antyakshara Prasa.

[For a short life-sketch of Subbaraya Shastri, please click here. And, for a detailed analysis of his Kritis , please click here.]

It is said; in his two Kritis – Venkata-saila-vihara (Hamirkalyani) and Ninnu-sevinchina (Yadukulakambhoji) – in the long drawn out Vilamba-kala – Sri Subbaraya Shastry combined the styles of his father (Svara-sahitya and Svarakshara) and of his Guru Sri Thyagaraja (Sangathis).

And his Janani Ninnuvina (Reethigowla) and Sankari-Neeve (Begada) are highly acclaimed for the delightful harmony of Raga-bhava and Sahitya.

He was versatile in other forms of Music as well. He learnt to play violin from a musician at the East India Company; and, is said to have become quite proficient in it.

He also gained familiarity with the Hindustani Music from the Maratha musicians Kokilakanta Meruswami and Ramadasa Swami, who were then the Vidvans at the Thanjavur Samsthanam. The traces of its influence can be seen in his Kritis Venkata-Shaila-Vihara (Hamir Kalyani) and Kamalamba (Desiya-Todi).

Since Subbaraya Shastri-couple had no children, they adopted Annaswami Shastri, the third son of Panju Shastri, as their own son.

After the demise of his father, by about 1834, Subbaraya Shastri along with his wife and son moved to Kanchipuram, where he stayed for about ten years or more. And, thereafter, they shifted to Triplicane in Madras; and, stayed there for only one year. It was while he was in Triplicane; Subbaraya Shastri composed the Kriti Ninnu-sevinchina (Yadukula-kambhoji), in praise of Sri Parthasarathy, the presiding Deity of the temple there.

He visited Madurai several times; and performed in the Meenakshi Amman temple.

Subbaraya Shastry taught violin to his son Annaswami Shastri; the two often used to gave duet performances.

It appears, Subbaraya Shastri also taught vocal music to Thanjavur Kamakshi Amma (c. 1810–90), the grandmother of Veena Dhanammal; and, Kanchi Kachiappa Sastri, the guru of Dhanakoti Ammal.

Among his other disciples were : Chandragiri Rangacharulu, also known as fiddle Rangacharulu; and,Tachur Singarcharulu – the cousin of Fiddle Rangacharulu

Then, Subbaraya Shastry was appointed as the Samasthana Vidwan in the Udayar-palayam Zamin; where he was till his death in 1862.

Just as Shyama Shastri did, Subbaraya Shastri could foresee his end. After performing the morning Sandhya-vandanam, he poured water on the floor saying ‘Dattam’; and, said that he would live only for two more hours. The Zamin and other pleaded with him; but, failed to persuade him to change his decision.

When asked about his last wish, Sri Subbaraya Shastri said:’ I have nothing to ask. The Ambal-anugraham has always been there on me; what more can I ask? ‘

A few minutes after that, he breathed his last at 8.00 AM on Dashami of Krishna-paksha of Chapa (Magha) masa of the Durmathi-nama-samvathsara 1783 (which nearly works out to 23 February 1862).

[ For a detailed study of Sri Subbaraya Shastri’s compositions, please do read ‘An analytical study of the Kritis of Sri Subbaraya Sastri, a Doctoral thesis by Dr. Smt. V. Veena Lakshmi]

[ Please also see ” The gem of the Trinity” about Sri Subbaraya Shastri by Vishnu Vasudev ]

***

Sri Annaswami Shastri (1827-1900)

Annaswami Shastri, the son of Panju Shastri was born just a couple of months after the demise of his grandfather Sri Shyama Shastry. He was initially named as Shyama Krishna, in memory of his grandfather. But, later he came to be known as Annaswami Shastri.

He was given in adoption to his uncle Subbaraya Shastri, who educated him in Kavya, Vyakarana, Alamkara and in Samgita (Music). He was also taught to sing and also to play on violin. At times, he and Subbaraya Shastri used to perform violin duets.

Annaswami Shastri began to compose Tana-varnas right from his youth. Among his compositions, the Daru Varna ‘Kaminchi-yunnadira’ (Kedaragaula, Rupaka-taala); and the Kriti ‘Inkevaru’ (Sahana) are well known.

He is said to have composed 10 Kritis and 2 Varnams. He structured his songs following the lines of Sri Shyama Sastry.

The Svara-sahitya for the Kriti ‘Palinchu-Kamakshi Pavani’ (Madhyamavathi); and, ‘Pahi Girija-sute’ (Anandabhairavi) are said to be his contributions.

Annaswami Shastri used to sing the Svara-Sahitya of the Kriti in the manner of a duo, where one sings the Svaras and the other the Sahitya, in succession.

After the demise of his father, Annaswami Shastri was appointed as the Asthana Vidwan of the Udayar-layam Zamin.

As a teacher; he taught violin and vocal to his son Shyama Shastri II, Sundârambâl, mother of Veena Dhanammâl; and Tacchur Chinna Singaracharulu.

Annaswami Shastri passed away in 1900, leaving his son Venkatasubramanya Sastri, known generally as Shyama Shastri II . Dr. V Raghavan mentions that he was a school teacher; and , was good in drawing. After retirement, he stayed in Madras; and, was a member of the Experts Committee of the Music Academy .

Disciples

Sri Shyama Shastry, comparatively, had a lesser number of disciples.

His principal disciple was his son – Subbaraya Shastri . Besides, he had three other disciples: Alasur Krishnayya; Sangita Swamy; Dasari, Tarangampadi Panchanada Iyer; and, Porambur Krishnayya.

Alasur Krishna Iyer:

Alasur Krishna Iyer was for some time the Samasthana Vidvan of Royal Court of Mysore. He was an expert in presenting intricate Pallavis. He had the privilege of being with Sri Shyama Shastry while he was at Madurai. He named his son as Subbaraya Shastri, in honour of his Guru. This boy, in turn, also grew up to become an accomplished musician.

*

Sangita Swamy

Sangita Swamy was a Sanyasin and a brilliant musician.

It is said; one day while Sri Shyama Shastry was walking along the street, he came upon a Sanyasin; and, as per the custom, greeted him with respect. But, to his surprise, the Sanyasin fell at the feet of Sri Shyama Shastry ; and, burst into a song ‘ O Jagadamba’.

Then, Sri Shyama Shastry could recognize him as his earliest student (Prathama-sishya), who had vanished mysteriously. It was only to this student that Sri Shyama Shastry had taught his Kriti ‘O Jagadamba’ in Anandabhairavi. With the sudden disappearance of his first student, Sri Shyama Shastry had grown rather cautious or even reluctant to accept any student.

On accidentally meeting his long-lost student, Sri Shyama Shastry burst into tears. The Sanyasin, in turn, contributed a Svara-sahitya to that Kriti, as his Guru-dakshina.

A little later, Sri Shyama Shastry sat before Bangaru Kamakshi and sang the Kriti ‘Adinamunci pogadi -pogadi’ in Anandabhairavi (Triputa-Taala); meaning: since that day, I have been praying to you praising you repeatedly in myriad ways; O my Mother do assure me and protect me.

*

Dasari

He was an expert Nagasvaram player. It is said; on a festival occasion in the Tiruvaruru temple, Dasari rendered on his instrument a delightful Alapana of the Shudda-Saveri-Raga; and followed it up by the Pallavi, improvised with several attractive Sangathis. Sri Thyagaraja, who was raptly listening to the music from his house, which was close by, was greatly pleased with Dasri’s elaboration of the Raga and the artistic rendering of his Kriti ’Daarini telusukonti’ rushed up to the temple and heartily congratulated Dasari on his splendid performance.

*

Porambur Krishnayya was another disciple of Shri Shyama Shastri; but, not much is known about him.

*

Tharangampadi Panchanada Iyer, a composer of high merit, was also said to be a student of Sri Shyama Shastri. His Kriti ‘Birana brova idi manchi samayamu’ (Kalyani) was quite popular. His Raga-malika, composed in 16 Ragas; and, beginning with the words ‘Arabhimanam‘ is a beautiful composition, which is widely sung in concerts. (? – I need to verify again whether he was he disciple of Shyama Shastri )

The Last week

Sri Shyama Shastri, just as Sri Thyagaraja and Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar, could foresee the day and time of his death. When his wife, a very pious lady, came to know of this prediction, she was thoroughly shaken; and, she prayed to Devi Kamakshi to take her away before that very sad day would come to pass. The merciful Mother Goddess granted her request; and, she peacefully passed away on February 1st 1827.

On the passing away of his wife, Sri Shyama Shastry is said to have remarked: “sAga anjunAL, seththu ArunAL”, which perhaps was meant to say: “five days to go (for me) to die; six days would have passed (since her death)’.

Just six days after his wife’s death, on February 7th, 1827, Sri Shyama Shastri decided to give up his earthly coils. He was at that time about sixty-four years of age. It was at Thanjavur, the Dashami, Tuesday (Cevvai), Shukla-paksha Makara (Magha) Masa, Shishira Ritu, Uttarayana, Vyaya-Samvatsara 1748. Kaliyugam 4927.

On that auspicious morning, Sri Shyama Shastri meditated upon his Ista-devata, the Mother Goddess Kamakshi for one last time. He laid his head on the laps of his son Subbaraya Shastri; and, asked him to softly recite the Karna-mantra into his ears. He was fully conscious till the very last moment. He peacefully, serenely journeyed to Sripuram, the heavenly abode, to join his Mother Devi Kamakshi.

Thus, passed away an immortal composer of the Karnataka Samgita.

In the Next part we shall take a brief at the structure and other details of the compositions of Sri Shyama Shastry.

Sources and References

- Indian Culture, Art and Heritage by Dr. P. K. Agrawal

- Shodhganga chapter Six

- Shodhganga Chapter Seven

- Shodhganga Chapter VI

- Shodhganga Chapter VII

- Shodhganga handle

- A Voyage through Dēśa and Kāla

- Compositions of Shyama Shastri (1762-1827)

- Origin and development of Indian music

- https://archive.org/stream/composers00ragh/composers00ragh_djvu.txt

- https://archive.org/details/composers00ragh/page/46/mode/1up

- Prof. P. Sambamoorthy

- https://ebooks.tirumala.org/downloads/syamasasthri.pdf

- https://www.sangeethapriya.org/tributes/shyamakrishna/dl_krithis.html

- http://www.medieval.org/music/world/carnatic/shyama.html

- http://carnatica.net/special/shyama.pdf

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/173579/11/11_chapter%204.pdf

All images are taken from Internet