Intro

1.1. Upavarsha is one of the remarkable sage-scholars who come through the mists of ancient Indian traditions. And, again, not much is known about him.

We come to know him through references to his views by Sri Shankara and others. Upavarsha was an intellectual giant of his times. He is recognized as one of the earliest and most authoritative thinkers of the Vedanta and Mimamsa Schools of thought. He is credited with being the first to divide the Vedic lore Mimamsa into Karma-kanda (ritualistic section) and Jnana-kanda (knowledge section).He advocated the six means of knowledge (cognition) that were adopted later by the Advaita school. He began the discussion on self-validation (svathah pramanya) that became a part of the Vedanta terminology. He is also, said to have, pioneered the method of logic called Adhyaropa-Apavada which consists in initially assuming a position and later withdrawing the assumption, after a discussion.

1.2. Upavarsha is placed next only to Badarayana the author of the Brahma sutra. The earliest Acharya to have commented upon Badarayana’s Brahma Sutra is believed to be Upavarsha. Among the many commentaries on Brahma sutra, the sub-commentary (Vritti) by Upavarsha – titled ” Sariraka Mimamsa Vritti”, (now lost ) – was most highly regarded.

1.3. Upavarsha was looked upon as an authority by all branches of Vedanta Schools; and is respected in the Mimamsa School also. Both Sabaraswamin and Bhaskara treat the ancient Vrttikara as an authority; and, quote his opinions as derived from ‘the tradition of Upavarsha ‘(Upavarsha-agama). Bhaskara calls Upavarsha as ‘shastra-sampradaya- pravarttaka’. Sri Shankara’s disciples who made frequent references to the works of Vrittikara-s on the Brahma Sutra often referred to Sariraka-mimamsa-vritti of sage Upavarsha.

2.1. Sri Shankara, in particular, had great reverence for Upavarsha and addressed him as Bhagavan, as he does Badarayana; while he addressed Jaimini and Sabara, the other Mimasakas, only as Teachers (Acharya).

2.2. It is believed that the words of Sri Shankara explain the correct account of Upavarsha’s doctrines. He is quoted twice by Sri Sankara in his Brahma-sutra-bhashya (3.3.53).

Before we get to Upavarsha and his views, let’s talk of few other things that surround him.

****

Out of Takshashila

3.1. Maha Mahopadyaya Shri Harprasad Sastri in his ‘Magadhan Literature’ (a series of six lectures he delivered at the Patna University during December 1920 and April 1921) talks about Upavarsha, in passing.

[In his First lecture the Pandit talks about Takshashila and its association with the Vedic literature. And, in the second lecture, he talks about the seven great scholars who hailed from the region of Takshashila : Upavarsha, Varaha, Panini, Pingala, Vyadi, Vararuch and Patanjali.]

3.2. According to the Maha Mahopadyaya, Takshashila a prominent city of Gandhara, a part of the ancient Indian polity included under the Greater Uttara-patha in the North-west, was for long centuries the centre of Vedic civilization. It was also at the entrances to the splendor that was India. The city gained fame in the later periods, stretching up to the time of the Buddha, as the centre of trade, art, literature and politics. Takshashila was also a renowned Center for learning to where scholar and students from various parts of India , even from Varanasi at a distance of more than 1,500 KM, came to pursue higher studies in medicine , art , literature , grammar , philosophy etc .

3.3. Pandit Harprasad Sastri says: “It was at Takshashila the city named after Taksha the son of Bharatha of Ramayana, and the capital of Taksha Khanda, that the King Janamejaya performed the sarpa-satra. It was here that Mahabharata was first recited by Vaishampayana. A beginning was made here of the classical literature as also of the Indian sciences. Jivaka, the famed medical man, the personal physician of the Buddha, studied at Takshashila for long years. The earliest grammarian known belonged to that city. The earliest writer of Mimamsa too, belongs to that city. The earliest writer on Veterinary science on horse belongs to its vicinity. In fact, all works in classical Sanskrit seem to have their origin in Takshashila. Further, at Takshashila, Indian learning moved on, very nearly shaking off the narrow groove in which the Vedic schools were trapped”.

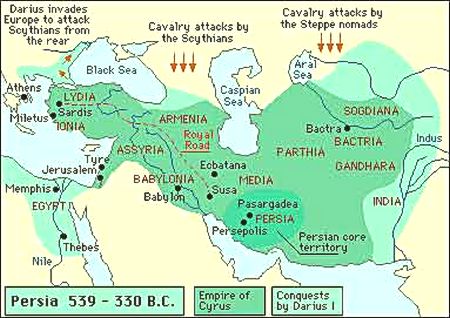

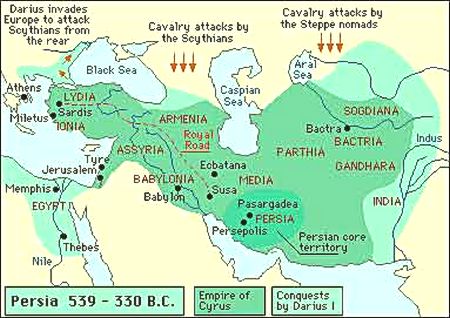

4.1. But, the glory of Takshashila came to an abrupt end when Darius (518 BCE) the Persian monarch who destroyed the dynasty founded by Cyrus, overpowered the North-West region of India and annexed it into the Achaemenid Empire. And, thereafter, Alexander the Great (326 BCE) subdued Ambhi the King of Taxila and overran the region. Alexander’s conquest and withdrawal was followed by prolonged quarrels among his Generals for control over North-west India.

4.2. The long periods of lawlessness, anarchy and chaos totally destroyed the cultural and commercial life of Taxila. By about the time of the Buddha, Taxila was losing its high position as a centre of learning. And, that compelled its eminent scholars like Panini the Great Grammarian, and scholars like Varsha and Upavarsha to leave Taxila to seek their fortune and patronage, elsewhere. They were, perhaps, among the early wave of migrant intellectuals to move out of the Northwest.

On to Pataliputra

5.1. By then, Pataliputra, situated amidst fertile plains on the banks of the river Sona at its confluence with the Ganga, was fast rising into fame as the capital of the most powerful kingdom in the East. The scholars drifting from Taxila all reached Pataliputra; and there they were honoured by the king in his assemblies ‘in a manner befitting their learning and their position’. And, thus began the literature of Magadha.

That also marked the birth of a new tradition.

5.2. Rajasekhara (10th century) a distinguished poet, dramatist, and scholar who wrote extensively on poetics – Alamkara shastra (the literary or philosophical study of the basic principles, forms, and techniques of Sanskrit poetry; treatise on the nature or principles of poetry); and who adorned the court of King Mahipala (913-944 AD) of the Gurjara-Prathihara dynasty, refers to a tradition (sruyate) that was followed by the Kings of Pataliputra (Kavya Mimamsa – chapter 10).

5.3. According to that tradition, the King , occasionally , used to call for assemblies where men of learning; poets ; scholars ; founders and exponents of various systems; and , Sutrakaras hailing from different parts of the country, participated enthusiastically ; and , willingly let themselves be examined. The eminent Sutrakaras too during their examinations (Sastrakara-Pariksha) exhibited the range of their knowledge as also of their creative genius. Thereafter, the King honoured the participants with gifts, rewards and suitable titles.

5.4. In that context, Rajasekhara mentions: in Pataliputra such famous Shastrakāras as Upavarsha; Varsha; Panini; Pingala ; Vyadī; Vararuci; and Patañjali; were examined ; and were properly honoured :—

Here Upavarsha and Varsha; here Panini and Pingala; here Vyadi and Vararuci; and Patanjali , having been examined rose to fame. (Kavya Mimamsa – chapter 10). “

“Sruyate cha Pataliputre shastra-kara-parikshasa I atro Upavarsha, Varshao iha Panini Pingalav iha Vyadih I Vararuchi, Patanjali iha parikshita kyathim upajagmuh II “

Group of Seven

6.1. It is highly unlikely that all the seven eminent scholars cited by Rajasekhara arrived at the King’s Court at Pataliputra at the same. The last two particularly (Vararuchi and Patanjali) were separated from the first five scholars by a couple of centuries or more. And, perhaps only the first five among the seven originated from the Takshashila region; while Katyayana and Patanjali came from the East. Katyayana, according to Katha Sarit Sagara, was born at Kaushambi which was about 30 miles to the west of the confluence of the Ganga and the Yamuna (According to another version, he was from South India). His time is estimated to be around third century BCE.

As regards Patanjali, it is said, that he was the son of Gonika; and, he belonged to the country of Gonarda in the region of Chedi (said to be a country that lay near the Yamuna; identified with the present-day Bundelkhand).His time is estimated to be about 150 BCE. It is said; Patanjali participated in a great Yajna performed at Pataliputra by the King Pushyamitra Sunga (185 BCE – 149 BCE). [This Patanjali may not be the same as the one who put together in a Sutra – text the then available knowledge on the system of Yoga.]

6.2. The Maha Mahopadyaya, however, asserts that the seven names cited by Rajasekhara are mentioned in their chronological order, with Upavarsha being the senior most and the foremost of them all.

6.3. Further, all the seven learned men were related to each other, in one way or the other. Upavarsha the scholar was the brother of Varsha a teacher of great repute. Both perhaps resided in Takshashila or near about. Panini the Grammarian was an inhabitant of Salatura – a suburb of Takshashila; and Pingala was his younger brother. And, both the brothers were students of Varsha. Vyadi also called Dakshayana, the fifth in the list, was the maternal uncle (mother’s brother) of Panini. It is said; Vyadi, the Dakshayana, was also a student of Varsha. He was called Dakshayana because: Panini’s mother was Dakshi, the daughter of Daksha. And, Daksha’s son was Dakshaputra or Dakshayana, the descendent of Daksha. [According to another version, Dakshayana might have been the great-grandson of Panini’s maternal uncle].

Then, Vararuchi also called as Katyayana was one of the earliest commentators of Panini. He was some generations away from Panini. And, the seventh and the last in this group was Patanjali who came about two centuries after Panini; and, he wrote an elaborate commentary on Panini’s work with reference to its earlier commentary by Katyayana.

7.1. Details of Upavarsa’s life or his nature etc are completely unknown. However, an ancient collection of legends – Katha-sarit-sagara (II.54; IV.4) narrates stories concerning Upavarsha, his daughter Upakosa, his brother Varsa and Vararuchi who, according to some, is identified with Vrittikara Katyayana, a famed commentator. They all figure in the story; and, were all contemporaries.

You can enjoy the delightful story of Vararuchi at :

http://www.wollamshram.ca/1001/Ocean/oosChapter002.pdf

7.2. Now, this Katha-sarit-sagara, a vast collection of stories, fables, folk- tales and legends, is said to be a re-rendering undertaken by Somadeva (Ca.11th century) . It is believed that Katha-sarit-sagara is based upon an older collection of stories titled Brihad-Katha said to have been written in Paishachi (a dialect that was lost even before the 10th century) by one Gunadya (Ca.200 BCE?). All the names that figure in that legend relate to eminent scholars that perhaps did exist.

But, since the stories narrated in Katha-sarit-sagara are highly fanciful the scholars tend to view the details of Upavarsha (as also of other scholars) as historical fiction; and, are chary of accepting them as history.

7.3. But, in any case, all agree that Upavarsha – a revered scholar well established in grammar; an authoritative Master among the Mimamsikas, Vedantins and Yoga teachers – did exist in the centuries prior to Sri Shankara.

Galaxy of Scholars

8.1. By any standards, the seven sages (saptha munih) formed a most eminent group of extraordinarily brilliant scholars. Each was an absolute Master in his chosen field of study.

8.2. Among the seven, Upavarsha was regarded the eldest and the most venerable: Abhijarhita. Upavarsha was a revered teacher; a scholar of great repute well established in grammar; and an authoritative commentator on Mimamsa (a system of investigation, inquiry into or discussion on the proper interpretation of the Vedic texts). And Upavarsha’s brother was Varsha who also was a renowned teacher. Both perhaps resided in Takshashila or near about.

We shall discuss about Upavarsha, with reference to citations of his views by other scholars, in Part Two of this Post. Let’s, now, talk in brief about the other famous-five.

Panini

9.1 In ancient India, Grammar, Vyakarana the foremost among the six Vedangas (ancillary parts of Vedas) was considered the purest paradigm science (pradanam cha satsva agreshu Vyakaranam). And , it was said : “ the foremost among the learned are the Grammarians , because Grammar lies at the root of all learning” ( prathame hi vidvamso vaiyyakarabah , vyakarana mulatvat sarva vidyanam – Anandavardhana ) . Panini, without doubt, is the foremost among all Grammarians.

[ protracted debates were carried out to assign a date to Panini. An important hint for the dating of Pāṇini is the occurrence of the words Yava-Yavana (यवनानी) (in 4.1.49), which might mean either a Greek or a foreigner or Greek script.

Indra-varuṇa-bhava-śarva-rudra-mṛḍa-hima-araṇya-yava-yavana-mātula-ācāryāṇāmānuk || PS_4, 1.49 ||

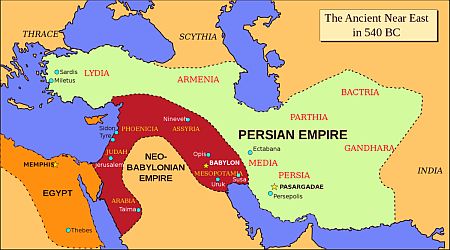

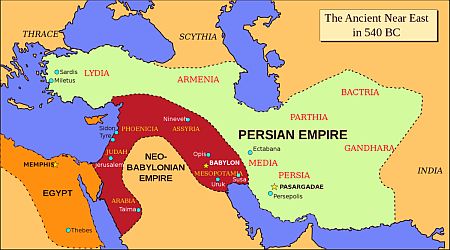

It needs to be mentioned here…

King Cyrus, the founder of Persian Empire and of the Achaemenid dynasty (559-530 B.C.), added to his territories the region of Gandhara, located mainly in the vale of Peshawar.

By about 516 B.C., Darius, the son of Hystaspes, annexed the Indus valley and formed the twentieth Satrapy of the Persian Empire. The annexed areas included parts of the present-day Punjab.

Many Greeks served as officials or mercenaries in the various Achaemenid provinces. And, Indian troops too formed a contingent of the Persian army that invaded Greece in 480 B.C. The Greeks and Indians were together thrown into the vast Persian machinery. Thus, Persia, in the ancient times, was the vital link between India and the Greeks of Asia Minor.

The first Greeks to set foot in India were probably servants of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (550-330 B.C.E) – that vast polity which touched upon Greek city-states at its Western extremity and India on the East. The first Greek who is supposed to have actually visited India and to have written an account of it was Skylax of Karyanda in Karia. He lived before Herodotus, who tells that Darius Hystargus (512–486) led a naval expedition to prove the feasibility of a sea passage from the mouth of Indus to Persia. Under the command of Skylax, a fleet sailed from Punjab in the Gandhara country to the Ocean.

Thus, even long before the conquest of Alexander the Great in the 330 BCE, there were cultural contacts between the Indians and the Greeks, through the median of Persia.

The term Yavana, is, essentially, an Achaemenian (Old-Persian) term. And, it occurs in the Achaemenian inscriptions (545 BCE) as Yauna and Ia-ma-nu, referring to the Ionian Greeks of Asia Minor.

The word was probably adopted by the Indians of the North-Western provinces from the administrative languages of the Persian Empire – Elamite or Aramaic. And, its earliest attested use in India was said to be by the Grammarian Pāṇini in the form Yavanānī (यवनानी), which is taken by the commentators to mean Greek script.

At that date (say 519 BCE, i.e. the time of Darius the Great’s Behistun inscription), the name Yavana probably referred to communities of Greeks settled in the Eastern Achaemenian provinces, which included the Gandhara region in North-West India. All this goes to show that Panini cannot be placed later than 500 BCE.]

*

[The fact that Greeks (Yonas or Yavanas) were familiar figures in the Noth-west – India even as early as in Ca.6th century BCE , is suupported by a reference in the Assalayana Sutta of Majjima Nikaya.

The Majjhima Nikaya is a Buddhist scripture, the second of the five Nikayas or collections, in the Sutta Pitaka, which is one of the Tipitakas (three baskets) of Pali Sthavira-vada (Theravada) Buddhism. The Pali Cannon is considered to be the earliest collection of the original teachings of the Buddha; and, it is said to have been composed following the resolution taken at the First Council , which took place at Rajagrha, soon after the Parinirvana of the Buddha. It was transmitted orally for many centuries , before it was reduced to writing in Asoka-vihara , Ceylon during the reign of Vattagamani (first century BCE).

In the Assalayana Sutta (93.5-7 at page 766/1420) , the discussion that took place between an young Brahmana named Assvalayana (Skt. Ashvalayana) and the Buddha , refers to countries of Yona and Kambhoja , which did not follow the four-fold caste division; but, recognized only two classes – viz., slaves and free men. And, in these countries, a master could become a slave; and, likewise , a slave could become a master.

The Buddha says : “ What do you think about this, Assalayana ? Have you heard in the countries of Yona (Yonarattam; Skt. Yona-rastram) and Kambhoja (Kambhojarattam; Skt. Kambhoja-rastram) and other adjacent districts, there are only two castes : the master and the slave ? And, having been a master , one becomes a slave; having been a slave , one becomes the master?” Assalayana agrees ; and replies : “ Yes Master , so have I heard this, in Yona and Kambhoja … having been a slave , one becomes a master.”.

Here, Yona is probably the Pali equivalent of Ionia; the reference being to the Bactrian (Skt. Bahlika) Greeks. And, Kambhoja refers to a district in the Gandhara region of Uttara-patha, to the North of the Madhya-desha (Middle Country) .]

9.2. Panini who gained fame as a Great Grammarian was the student of Varsha. His fame rests on his work Astadhyayi (the eight chapters) – also called Astaka , Shabda-anushasana and Vritti Sutraa- which sought to ensure correct usage of words by purifying (Samskrita) the language (bhasha) – literary and spoken ( vaidika – laukika) – that was in use during his days. The Eight Chapters comprises about four thousand concise rules or Sutras, preceded by a list of sounds divided into fourteen groups. The Sutra Patha, the basic text of Astadhyayi has come down to us in the oral traditions; and has remained remarkably intact except for a few variant readings and plausible interpolations.

[Panini’s Ashtadhyayi is composed in Sutra form – terse and tightly knit; rather highly abbreviated. The text does need a companion volume to explain it. That utility was provided by Katyayana who wrote a Vartika, a brief explanation of Ashtadhyayi. Considerable time must have elapsed between Panini and Katyayana, for their language and mode of expressions vary considerably. Similarly, a fairly long period of gap is assumed between Katyayana and Patanjali the author of Mahabhashya, a detailed commentary on Panini’s work; as also his observations of the Vartika of Katyayana. Katyayana is assigned to third century BCE; and Patanjali followed him about a hundred years later (second century BCE), perhaps 150 BCE.]

9.3. Astadhyayi was not composed for teaching Sanskrit, though it is a foundational text that can be used for understanding the language, speaking it correctly and using it correctly. Panini’s work is also not a text of Grammar, as it is commonly understood. It is closer to Etymology.

In way, Panini is dealing with a system having finite number of rules that can be used to describe a potentially infinite number of arrangements of utterances (sentences, vakya). His was indeed a pioneering task in any language. With his system it became possible to say whether or not a sequence of sounds represented a correct utterance in the bhasha (Sanskrit).

In fact, Panini’s work is context-sensitive; it addresses only Sanskrit; and, is not a ‘universal Grammar’. But, a most amazing thing happened in the twentieth century with the development of computer languages. The writers of these virtual languages discovered that Panini’s rules can be used for describing perhaps all human languages; and, it can be used for programming the first high level programming language, such as ALGOL60. It is said; by applying Panini’s rules it is possible to check whether or not a given sequence of statement forms a correct expression in a particular programming language.

9.4. Panini did not seem to lay down rigid rules for the correct sequence of words in a sentence. He left it open. But, his system allows for a rule to invoke itself (recursion). By repeatedly applying the same set of rules, one could make a long sentence or extended it as long as one wanted.

9.5. But , Panini’s primary concern or goal (lakshya) was building up of Sanskrit words (pada) from their root forms (dhatu, prakara), affixes (pratyaya), verbal roots; pre-verbs (upasarga); primary and secondary suffixes; nominal and verbal terminations ; and , their function (karya) in a sentence. The underlying principle of Panini’s work is that nouns are derived from verbs.

9.6. Panini was also interested in the synthetic problems involved in formation of compound words; and the relationship of the nouns in a sentence with the action (kriya) indicated by the verb. With this, he sought to systematically analyze the correct sentences (vakya).

Panini also defined the terms (samjna) employed in the grammar, set the rules for interpretation (paribhasha), and outlined, as guideline, the convention he followed.

[Panini did not neglect meaning; but, he was aware the meanings of the words were bound to change with the passage of time as also in varying contexts. He recognized the fact the people who spoke the language and used it day-to-day lives were better judges in deriving, meaning from the words.]

Panini’s Astadhyayi has thus served, over the centuries, as the basic means (upaya) to analyze and understand Sanskrit sentences.

*

[Regarding Panini’s contribution to Sanskrit language , Prof. A L Basham writes (The Wonder That Was India):

After the composition of the Rig Veda, Sanskrit developed considerably. New words, mostly borrowed from non Aryan sources, were introduced, while old words were forgotten, or lost their original meanings. In these circumstances doubts arose as to the true pronunciation and meaning of the older Vedic texts, though it was generally thought that unless they were recited with complete accuracy they would have no magical effectiveness, but bring ruin on the reciter. Out of the need to preserve the purity of the Vedas India developed the sciences of phonetics and grammar. The oldest Indian linguistic text, Yaska’s Nirukta, explaining obsolete Vedic words, dates from the 5th century B.C., and followed much earlier works in the linguistic field.

Panini’s great grammar, the Astadhyayi (Eight Chapters) was probably composed towards the end of the 4-th century BCE . With Panini , the language had virtually reached its classical form, and it developed little thenceforward, except in its vocabulary.

By this time the sounds of Sanskrit had been analysed with an accuracy never again reached in linguistic study until the 19thcentury. One of ancient India’s greatest achievements is her remarkable alphabet, commencing with the vowels and followed by the consonants, all classified very scientifically according to their mode of production, in sharp contrast to the haphazard and inadequate Roman alphabet, which has developed organically for three millennia. It was only on the discovery of Sanskrit by the West that a science of phonetics arose in Europe.

The great grammar of Panini, which effectively stabilized the Sanskrit language, presupposes the work of many earlier grammarians. These had succeeded in recognizing the root as the basic element of a word, and had classified some 2,000 monosyllabic roots which, with the addition of prefixes, suffixes and inflexions, were thought to provide all the words of the language. Though the early etymologists were correct in principle, they made many errors and false derivations, and started a precedent which produced interesting results in many branches of Indian thought

There is no doubt that Panini’s grammar is one of the greatest intellectual achievements of any ancient civilization, and the most detailed and scientific grammar composed before the 19th century in any part of the world. The work consists of over 4000 grammatical rules, couched in a sort of shorthand, which employs single letters or syllables for the names of the cases, moods, persons, tenses, etc. In which linguistic phenomena arc classified.

Some later grammarians disagreed with Panini on minor points, but his grammar was so widely accepted that no writer or speaker of Sanskrit in courtly circles dared seriously infringe it. With Panini the language was fixed, and could only develop within the framework of his rules. It was from the time of Panini onwards that the language began to be called Samskrta, “perfected” or “refined”, as opposed to the Prakrta (unrefined), the popular dialects which had developed naturally.

Paninian Sanskrit, though simpler than Vedic, is still a very complicated language. Every beginner finds great difficulty in surmounting Panini’s rules of euphonic combination (sandhi), the elaboration of tendencies present in the language even in Vedic times. Every word of a sentence is affected by its neighbors. Thus na- avadat (he did not say) becomes navadat. But, na-uvaca (with the same meaning) becomes novaca. There are many rules of this kind, which were even artificially imposed on the Rg Veda, so that the reader must often disentangle the original words to find the correct meter.

Panini, in standardizing Sanskrit, probably based his work on the language as it was spoken in the North-West. Already the lingua franca of the priestly class, it gradually became that of the governing class also. The Mauryas, and most Indian dynasties until the Guptas, used Prakrit for their official pronouncements.

As long as it is spoken and written a language tends to develop, and its development is generally in the direction of simplicity. Owing to the authority of Panini, Sanskrit could not develop freely in this way. Some of his minor rules, such as those relating to the use of tenses indicating past time, were quietly ignored, and writers took to using imperfect, perfect and aorist indiscriminately; but Panini’s rules of inflexion had to be maintained. The only way in which Sanskrit could develop away from inflexion was by building up compound nouns to take the place of the clauses of the sentence.

With the growth of long compounds Sanskrit also developed a taste for long sentences. The prose works of Bana and Subandhu, written in the 7th century, and the writings of many of their successors, contain single sentences covering two or three pages of type. To add to these difficulties writers adopted every conceivable verbal trick, until Sanskrit literature became one of the most ornate and artificial in the world.

Indian interest in language spread to philosophy, and there was considerable speculation about the relations of a word and the thing it represented. The Mimamsa School , reviving the verbal mysticism of the later Vedic period, maintained that every word was the reflexion of an eternal prototype, and that its meaning was eternal and inherent in it. Its opponents, especially the logical school of Nyaya , supported the view that the relation of word and meaning was purely conventional. Thus the controversy was similar to that between the Realists and Nominalists in medieval Europe.

Classical Sanskrit was probably never spoken by the masses, but it was never wholly a dead language. It served as a lingua franca for the whole of India, and even today learned Brahmans from the opposite ends of the land, meeting at a place of pilgrimage, will converse in Sanskrit and understands each other perfectly.]

Pingala

10.1. Pingala was the younger brother of Panini. He is celebrated as the author of Chhanda-sastra an authoritative text on the rules governing the structure of various Vedic meters adopted by different Vedic shakhas (schools); enumeration of meters (chhandas) with fixed patterns of long (Guru) and short (Laghu) syllables.

10.2. In the Indian context Chhandas Shastra (roughly, the Prosody) is not merely about construction of verses or about rhythm – patterns (praasa). It is, on the other hand, a complete technology of poetry. It attempts to build a systematic relation (or patterns of relations) between meter (Chhandas) and syllables (akshara) ; syllables and articulated sound (varna) ; the pronunciation of sounds with its vibrations (spanda) ; the vibrations with desired effects (viniyoga) ; and , the usefulness of such effects in mans’ life.

10.3. Pingala explains the disciplines and forms of seven basic meters : Gayatri (24 syllables) ; Ushnik (28 syllables ) ; Anustup (32 syllables); Brihati (36 syllables); Pankti (40 syllables) ; Tristup (44 syllables) ; and, Jagati ( 48 syllables); their characteristics ; and , the variations permissible under each meter. He also provides a recursive algorithm for determining how many of these form have a specified number of short syllables (Laghu).

10.4. Pingala, in this context, is credited with the first known description of the binary numerical system as also with a sequence of numbers called mātrāmeru now recognized as Fibonacci numbers. The Computer theorists of the present-day say: “A remarkable example of the mathematical spirit of Piṅgala’s work is his computation of the powers of 2. He provides an efficient recursive algorithm based on what computer scientists now call the divide-and-conquer strategy”.

[In the field of music, it is said, Piṅgala’s algorithms were generalized by Sārṅgadeva to rhythms which use four kinds of beats – druta, laghu, guru and pluta of durations 1, 2, 4 and 6 respectively (Saṅgītaratnākara, c. 1225 C.E.). In Mathematics, Āryabhata (5th Century) further developed on Piṅgala’s use of recursion Algorithms.]

For more on Pingala’s Chandaḥśāstra and Pingala’s Algorithms, please check the following links:

https://sites.google.com/site/mathematicsmiscellany/mathematics-in-sanskrit-poetry

http://www.northeastern.edu/shah/papers/Pingala.pdf

**

Vyadi Dakshayana

11.1. Vyadi Dakshayana was related to Panini. Some say, Vyadi was the maternal uncle of Panini, while some others say he was the grandson of Panini’s maternal uncle. Vyadi also wrote about Grammar in his Samgraha (meaning, compendium) or Samgraha Sutra. In his text, Vyadi went further than Panini. Unlike Panini who strictly kept out of his Sutra all matters foreign to Grammar (etymology), Vyadi Dakshayana included in his Samgraha the topics that were not directly related to Grammar that was used as a tool (upaya) for day-to-day transactions.

11.2. Vyadi – Dakshayana’s Samgraha or Samgraha Sutra, basically, is a work of grammar (Vyakarana shastra). Yet; it dealt on the philosophical aspects of grammar as well. It speculated, at length, on the question whether the language sounds (including words) is fixed (nitya) or is it of a passing nature (karya). He said; the meaning of a description (word) consists entirely in its being related to an individual object (dravya). He seems to have said; it would be ideal if a word carries a single meaning that can be uniformly applied in all situations. But now, the meaning of a word is largely context sensitive; and, therefore, a word need not have a fixed or a single meaning. Vyadi did not neglect meaning; but was aware that the meanings of the words were bound to change with the passage of time, as also in varying contexts. He recognized the fact the people who spoke the language and used it in their day-to-day lives were better judges in deriving, meaning from the words.

11.2. But, he said, in any case, one must study grammar diligently. Patanjali who came later seemed to love Vyadi’s Samgraha; and, held it in great esteem: “beautiful is Dakshayana’s Grand work, the Samgraha – Shobhana khalu astu Dakshayanena Samgrahasya kruthihi” (Mbh. 1.468.11).

[The Samgraha Sutra is now lost. We know of it through references to its verses in later texts. Samgraha is said to have been a grand work (sobhana) running into 100,000 verses, discussing about 14,000 subjects. But, by the time of Bhartrhari (seventh century A. D) the work was already lost. Vyadi is also credited with Paribhasha or rules of interpreting Panini; and also with Utpalini a sort of dictionary. These works are also lost. ]

*

Vararuchi Katyayana

12.1. Vararuchi also called Katyayana (also as Punarvasu and Medhajita) is one of the earliest commentators of Panini that are known to us. It is likely there were other commentators before his time. Katyayana offered his comments on selected Sutras of Panini, by way of explanatory Notes or annotations titled as Vrittika-s. Out of about 4,000 Sutras of Panini, Katyayana selected about 1,245 Sutras for comments; and, on these he offered about 4,300 or more sets of explanatory Notes, Vrittika-s. These Vrittikas (Varttika-patha or text in original form) of Katyayana have not come down to us directly. They all have been picked up from Patanjali’s Mahabhashya, where they are quoted and preserved.

12.2. In his Vrittikas, Katyayana aims to provide a new dimension to Astadhyayi. Katyayana takes up a sutra of Panini and annotates it; supplements it with additional information; modifies, at places, the views of Panini; and, generally offers explanations according to his own understanding. He even rectifies those Sutras where, according to him, something remained unsaid (anukta) or was badly-said (durukta).

12.3. Some wonder why Katyayana had to offer critical comments on such large number of Sutras. One explanation is that Katyayana came several generations after Panini; and in the meantime the language had changed with new forms of expressions coming into vogue. The other is; the fact that Panini originated from North West while Katyayana came from the East may also have something to do with difference in their perceptions. Considering these factors, Katyayana’s criticisms seem fair.

Katyayana showed no disregard towards the revered Master Panini. Katyayana, on the other hand, shows great respect for Panini. He closes his Notes on each Chapter of Astadhyayi with the auspicious word Siddham – This is correct; well proved. At the end of his work, Katyayana offers respectful submission to the venerable sage (Muni) saying: Bhavatah Panineh Siddham, what Bhagavan Panini has said is absolutely correct.

[Note: there have been other Vararuchi-s and other Katyayana-s in various fields and in different times.]

*

Patanjali

13.1. Patanjali’s Mahabhashya fulfilled a long felt need. Till its appearance, the learners had to depend on Vritti or Varttika to study Astadhyayi. But, just as the Astadhyayi, the Vrittis too were in the inscrutable Sutra format.

Mahamahopadyaya says that it was only after the advent of Mahabhashya that Panini’s work Astadhayi gained universal acceptance. Till then, he says, Astadhayi had a rather limited circulation; perhaps confined to closed group of scholars. For instance, though Arthashastra came to written, say, about a hundred years after Panini, its author Kautilya (second or third century BCE) did not seem to be aware of Panini’s rules of grammar. [Incidentally, Kautilya too just as Panini migrated from Takshashila region to Pataliputra.] It is said; there are many expressions in Kautilya’s work that do not meet the approved standards set by Panini. Kautilya still seemed to be using parts of speech and such other grammatical terms that were set by grammarians of much earlier times.

13.2 Patañjali’s Mahābhāṣya is reckoned as one of the most learned and difficult texts among human literary production. As per a popular saying about this text : mahābhāṣyaṃ vā pāṭhanīyaṃ mahārājyaṃ vā pālanīyam –“One can either study the Mahābhāṣya or rule a great realm’. Both tasks, should they be carried out successfully, require tremendous training, dedication, and occupy a person throughout the entirety of his/her life. What makes this text so difficult is not, as one might at first expect, the complexity of its language, but rather the assumption that the reader has a mastery not only of the Aṣṭādhyāyī ; but also of the various problems involved in its interpretation as would arise during a moreelementary study of Pāṇini’s grammar.

As for the content of the work, the Mahābhāṣya is not a direct commentary on the Astadhyayi but, above all, a “discussion” (bhāṣya) of the vārtikas, “critical comments,”(vārtika) by Kātyāyana as well as a number of other grammatical arguments presented in metrical form (kārikā). All of this takes place in the form of a lively debate between what later commentators identify as an Acārya , “teacher,” and one or more Acāryadeśīyas, “almost-teachers.

In some places Kātyāyana and Patañjali accept Pāṇini’s rules as they are formulated; but, in others, both commentators come to the conclusion that certain sūtras require either modification in their basic formulation or additions (upasaṃkhyāna iṣṭi ). Sometimes, entirely new rules are formulated; but, sometimes sutras are rejected as superfluous.

13.3. Patanjali’s Mahabhashya is composed in a conversational style employing a series of lively dialogues that takes place among three persons: Purvapakshin (who raises doubts); the Siddanthikadeshin (who argues against objections, but only provides partial answers); and Siddhantin (the wise one who concludes providing the right answers) . Its method is engaging, dotted with questions like “What?” and “How?” posed and resolved; introducing current proverbs and references to daily social life. In addition, Patanjali builds into his commentary about seven hundred interesting quotations from Vedic texts, Epics, and from the works of earlier authors.

13.4. Mahabhashya is an extensive discussion on Panini’s Astadhyayi spread over 85 Chapters. Yet; Mahabhashya is not a full (sutra to Sutra) commentary on Astadhyayi. Patanjali offers comments on about 1,228 select Sutras out of about 4,000 Sutras of Panini’s text. It draws upon Katyayana’s Vrittika, Vyadi’s Samgraha as also on the Karikas and Vrittis of other commentators. It analyzes the rules into components, adding elements necessary to understand the rules, giving supporting examples to illustrate how the rule operates.

14.1. Patanjali, in a way, takes off from Panini who focused on words. The Mahabhashya begins with the words ‘atho sabda-anu-shasanam’: here begins the instruction on words. The three important subjects that Patanjali deals with are also concerned with words: formation of words, determination of meaning, and the relation between a word (speech sounds – Shabda) and its meaning. He also talks about the need to learn Grammar and to use correct words; nature of words; whether or not the words have fixed or floating meanings and so on.

14.2. In general, Panini manipulates word derivation as a tool to derive sentence. The basic purpose of a grammar, according to Patanjali, is to account for the words of a grammar; not by enumerating them; but, by writing a set of general (samanya) rules (lakshana) that govern them and by pointing out to exceptions (visesha).These general rules, according to him, must be derived from the usage, for which the language of the ‘learned’ (shista) is taken as the norm.

14.3. At times, Patanjali finds fault with Katyayana’s criticism; defends Panini against unfounded criticism; but, again criticizes and re-states certain other rules enunciated by Panini. Then he takes up those Sutras that were not discussed by Katyayana. He also revises or supplements certain rules of Panini in order to ensure they are in tune with the contemporary (Patanjali’s time) usage. But, in his philosophical approach to grammar, Patanjali seems to have been influenced by Samgraha of Vyadi.

The time of Upavarsha

15.1. The time of Upavarsha is not known exactly. But it is surmised to be before 400 BCE. This estimate is based on certain circumstantial events the dates of which are generally accepted.

15.2. The unrest in the North-West commenced with the conquest of Darius (550–486 BCE) and it later worsened with the annexation of a considerable portion of the North- Western India into the Persian Empire. It is said; Darius marched into the Taxila Satrapy during the winter of 516-515 BCE; and thereafter set about conquering the Indus Valley in 515 BCE.

15.3. The next significant date in the context of Upavarsha is the founding of the city of Pataliputra to where Upavarsha and others migrated. Pāṭaliputra (पाटलिपुत्र) of ancient India (Patna of modern-day), it is said, was originally built by Ajatashatru (son of King Bimbisara of Magadha – 599 BCE to 491 BCE) in or about 490 BCE. Later, King Shishuka the founder of the Shishunaga dynasty, who established his Magadha Empire in 413 BCE, shifted his Capital from Rajgriha to a more prosperous and a more secure city: Pataliputra. The Shishunagas in their time were the rulers of one of the largest empires of the Indian subcontinent. The city of Pataliputra thus came into prominence, naturally. And, the eminent scholars from many parts of India gathered at Pataliputra seeking King’s patronage. Thereafter, Pataliputra gained greater fame and prosperity during the time of Mahapadma Nanda who succeeded the Shishunagas and founded the Nanda dynasty. Mahapadma Nanda (C. 400-329 BCE) who declared himself the most powerful Samrat and Chakravartin ruled from Pataliputra.

15.4. The scholars who have studied Panini (a contemporary of Upavarsha) in greater detail have suggested 4th century BCE or earlier as the time of Panini. Some say; a 5th or even late 6th century BC date cannot be ruled out with certainty. But, generally, scholars accept that Panini’s time was, in any case, not later than C.400 BCE.

15.5. The group of scholars – Upavarsha, Varsha, Panini, and Pingala – seem to have migrated from Takshashila region to Pataliputra during the reign of the Shishunaga kings or the reign of Mahapadma Nanda.

15.6. Following these events/dates the time of Upavarsha is reckoned to be not later than fourth century BCE.

*

Birth of a new tradition

16.1. With the crossover of the core group of scholars from the North West towards the East, the intellectual capital of the then ancient India shifted from Takshashila to Pataliputra. And, that was also significant in another way. The transition, somehow, marked the end of the Sutra period and the beginning of the period of Shastras , Vrittis, Vrittikas and such other , comparative , descriptive texts. The Sutra texts which were in a highly condensed format, by their very nature, were difficult to comprehend. Attempts were made by the scholars at Pataliputra to elaborate upon, comment upon and explain the Sutra texts (Sutra Patha) in a manner that could be read and understood by other seekers and students.

16.2. This phenomenon of giving up the highly condensed inscrutable Sutra format and taking up to writing more expansive Notes (Vrittikas), critiques (Vrittis), elaborate commentaries (Bhashyas) etc was not confined to traditional texts – Darshanas- alone. It even spread to various branches of secular knowledge, such as: economics, polity, medicine, and theatrical arts etc; and, spilled over to exotic and erotic subjects. A fresh wave of writers began composing expansive works in poetic forms that could be enjoyed at readers’ leisure. Such comprehensive works (Shastras) did render even tough subjects attractive, easier to commit to memory and, of course, easier to put it to use in day-to-day life. With that, the Sutra period met its end in Magadha.

Perhaps the increasing practice of writing books to impart knowledge instead of depending on oral transmissions also contributed towards this development.

16.3. Some explanation about the terms mentioned above appears necessary here. Let me digress for a short while.

Sutra

17.1. Generally a subject or a body of study dealt in ancient Indian texts was expounded through a series of works and traditions (sampradaya) that were followed and kept alive by its adherents, over a period of time. Since the subject matter was scattered over several texts and diverse oral renderings, attempts were made by some diligent scholars to put in one place , for the benefit of students and learners of coming generations, the salient arguments and important references bearing on the subject. Such compilation or collation was made in the briefest possible manner, so that it could by learnt by – heart , retained in memory and passed on to the next generation of learners. Such highly condensed text-references came to be known as Sutra-s.

17.2. Sutra literally means a thread as also the one over which gems are strewn (sutre mani gane eva). But, technically, in the context of ancient Indian works, Sutra meant an aphoristic style of condensing the spectrum of all the essential aspects, thoughts of a doctrine into terse, crisp, pithy pellets of compressed information ( at times rather disjointed ) that could be easily committed to memory. They are analogous to synoptic notes on a lecture; and by tapping on a note, one hopes to recall the relevant expanded form of the lecture. Perhaps the Sutras were meant to serve a similar purpose. A Sutra is therefore not merely an aphorism but a key to an entire discourse on a subject. Traditionally, each Sutra is regarded as a discourse rather than as a statement.

17.3. Each school of thought had its Sutra collated by a learned Sutrakara, the Compiler of that School. For instance, the Nyaya School had its Sutra by Gautama; Vaisheshika School by Kanada; Yoga School by Patanjali; Mimamsa School by Jaimini ; and , Vedanta School by Badarayana. Besides, there are a number of Sutras on various other subjects. [Of all the Schools, the Samkhya did not seem to have a Sutra of its own. ]

Badarayana is of course the most celebrated of them all. He is the compiler, Sutrakara, of the Brahma Sutras (an exposition on Brahman) also called Vedanta Sutra, Sariraka Mimamsa Sutra and Uttara Mimamsa Sutra. The style of presentation adopted by Badarayana set a model for Sutras that followed.

17.4. The method adopted by a Sutrakara was to refer to a specific passage in a text, say an Upanishad, by a key word, or a context (prakarana) or a hint to the topic for discussion. He would also hint his reasoning in a word or two. The Sutrakara would follow it by Purva-paksha (prima facie view or opponents view), Uttara-paksha (his own explanation/rebuttal) and Siddantha (his conclusion). The Sutra–text (Sutra patha) was so terse that it would need a commentator to make sense out of the Sutra. The genius of the commentator on the Sutra ( Vrittikara or Bashyakara ) was in his ingenuity to pinpoint the Vishesha Vakya the exact statement in the Vedic text referred to by the Sutra; to maintain consistency in the treatment – in the context (prakarana), and the spirit of the original text; and, in bringing out the true intent and meaning of the Sutrakara’s reasoning and conclusions.

17.5. But, to dismay of all, the concept of Sutra was often carried to its extremes. Brevity became its most essential character. It is said a Sutrakara would rather give up a child than expend a word. The Sutras often became so terse as to be inscrutable. And, one could read into it any meaning one wanted to. It was said, each according to his merit finds his rewards.

*

Vritti

18.1. Sutra by itself is unintelligible, unless it is read with the aid of a commentary. The function of bringing some clarity into Sutra-patha was the task of Vritti. The Vritti , simply put , is a gloss, which expands on the Sutra; seeks to point out the derivation of forms that figure in the Sutra (prakriya); offers explanations on what is unsaid (anukta) in the Sutra and also clarifies on what is misunderstood or imperfectly stated (durukta) in the Sutra.

*

Vrittika

19.1. Then, Vrittika is a Note or an annotation in between the level of the Sutra and the Vritti. It attempts to focus on what has not been said by a Sutra or is poorly expressed. And, it is shorter than Vritti.

*

Bhashya

20.1. The Vritti is followed by Bhashya , a detailed , full blown , exposition on the subjects dealt with by the Sutra ; and it is primarily based on the Sutra , its Vrittis , Vrittikas , as also on several other authoritative texts and traditions. Bhashya includes in itself the elements of : explanations based on discussion (vyakhyana); links to other texts that are missed or left unsaid in the Sutra (vyadhikarana) ; illustrations using examples (udaharana) and counter-examples (pratyudhaharana) ; rebuttal or condemnation of the opposing views of rival schools (khandana) ; putting forth its own arguments (vada) and counter arguments (prati-vada) ; and , finally establishing its own theory and conclusions (siddantha).

20.2. Let’s, for instance, take the Sutra, Vritti-s and Bhashya-s in the field of grammar (vyakarana). Here, Panini’s Astadhyayi is the principal text in Sutra format, referred to as Astaka (collection of eight) or as Sutra-patha (recitation of the Sutra). It is the basic and the accepted text. But, its Sutra form is terse and tightly knit; rather highly abbreviated. The text does need a companion volume to explain it. That utility was provided by Vararuchi-Katyayana who wrote a Vartika, Notes or brief explanations on selected Sutras of Astadhyayi. And, Patanjali who followed Katyayana, much later, wrote Maha-bhashya, a detailed commentary on Panini’s Astadhyayi, making use of Katyayana’s Vritti and several other texts and references on the subject. He presented the basic theoretical issues of Panini’s grammar; he expanded on the previous authors; supported their views and even criticized them in the light of his own explanations.

20.3. The trio (Trimurti) of Panini, Katyayana and Patanjali are regarded the three sages (Muni traya) of Vyakarana Shastra. Here, in their reverse order, the later ones enjoy greater authority (yato uttaram muninaam pramaanyam); making Patanjali the best authority on Panini.

21.1. Upavarsha, regarded the most venerable (Abhijarhita), revered as Bhagavan and as ‘shastra-sampradaya- pravarttaka’ is described both as Shastrakara and Vrittikara. However, in the later centuries, his name gathered fame as that of a Vrittikara, the commentator par excellence on the Mimamsa. We shall talk of Upavarsha the Vrittikara in the next part of this post.

Click here for Part Two

Continued in

Part Two

Sources and References:

1. Magadhan Literature by Mahamahopadyaya Haraprasad Sastri; Patna University (1923)

2. Astadhayi of Panini ( Volume One ) by Pundit Rama Natha Sharma

3. A History Of Sanskrit Literature Classical Period Vol I by Prof.SN Dasgupta; Calcutta University (1947)

4. The Philosophy of the Grammarians, Volume 5; edited by Harold G. Coward, Karl H. Potter, K. Kunjunni Raja; Princeton University Press (1990)

5. Grammatical Literature, Part 2, by Hartmut Scharfe ; Otto Harrassowitz (1977)

6. A New History of the Humanities: The Search for Principles and Patterns… By Rens Bod; Oxford University press

7. An account of ancient Indian grammatical studies down to Patanjali’s Mahabhasya: by E. De Guzman 0rara