Sri Shyama Shastry – Music-Continued

Kshetra Kritis

The collection (Samucchaya) or the series of compositions that are dedicated to a common theme or to a particular Deity or Deities are known as Kriti-Samucchaya-Srinkhala.

And, the group of the Kritis (Kriti-Samucchaya) that relate to Kshetras (places sanctified by the presence of renowned temples or sacred rivers) are termed as Kshetra Kritis.

It was a tradition in those days for the musical composers of merit to compose and sing songs in honor of the presiding deities, whenever they visited a prominent temple-town. Such compositions were classified as Kshetra Kritis. Sri Thyagaraja as also Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar followed that time-honored tradition –Sampradaya . So did Sri Shyama Shastry.

Such Kritis that primarily sing the glory, splendor and the adorable nature of the god or the goddess presiding over the Kshetra; have also built into their Caranas few details concerning the temple, its architecture etc., as also references to the Parivara-Devathas surrounding the principal Deity; the greatness (Mahima) of the sacred (Punya) Kshetra; and, the magnificence of the god residing there.

Sometimes, the name of the place/ temple-town (Sthala- Kshetra) where the musical-work was actually composed is built into it. The indications to that effect are called Sthala-mudra or Kshetra Mudra.

The Kshetra-Kritis are musical gems; remarkable for their soulful music, inspired rich lyrics and complex structure. Each of the compositions here is remarkable for the beauty of expression, devotional fervor and literary excellence.

*

There are numerous instances of such series or group of compositions , as : the Pancha-ratna Kritis composed by Sri Thyagaraja at each of the pilgrimage centers he visited, in submission to the gods and goddesses residing in the temples there , like : Varadaraja Swamy (Sri Rangam); Kamakshi (Kanchipuram); Venkateshwara (Tirupathi); Sundareshwara (Kovur); and, Saptha-risheeswara and Devi Srimathi (Lalgudi ).

The series of Kritis such as: Panchalinga Kshetra Kritis; Tiruvaruru Pancalinga Kritis; Navagraha-Kritis; Abhayamba–vibhakti-Kritis; Madhuramba–vibhakti-Kritis and similar others composed by Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar are well known. And, his Kamalamba-navavarna and Nilotpalamba-vibhakti Kritis are indeed marvelous and matchless.

*

The only time that Sri Thyagaraja went out of Thiruvarur was at his age of seventy-two in order to honour an invitation extended by his Guru-samana Sri Upanishad Brahmendra of Kanchipuram. He hesitated much; and, set out of his home only after he was assured and promised by his family and disciples that they would unfailingly offer worship (Rama-panchayatana) to his beloved deity Sri Rama, regularly at all the three times of the day. During that fairly long sojourn, lasting for about six months or a little more (from April to October 1839), he visited several places and temples. The farthest place that Sri Thyagaraja visited was Tirumala, the abode of Sri Venkatesvara, atop the Tirupathi hills.

Among the Trinity, Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar was the foremost in this regard. He was a pilgrim virtually all his life. He visited a large number of shrines and sang about them and the deities enshrined there.

Dri Dikshitar composed soulful songs in praise of a number of gods and goddesses. About 74 of such temples are featured in his Kritis; and there are references to about 150 gods and goddesses. The most number of his Kritis (176) were in praise of Devi the Mother principle, followed by (131) Kritis on Shiva. Dikshitar was the only major composer who sang in praise of Chaturmukha Brahma.

In addition to submitting his prayers and praising (Stuti) the Devi or Devatha, Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar artistically built into his Kritis the details such as: the brief references to the temple; its architecture; its rituals; and, its deity. Amidst all these details he skillfully wove the name of the Raga (Raga-mudra) and his own Vaggeyakara–Mudra, signature. All these were structured into well-knit short Kritis composed in grand music, glowing with tranquil joy, embodied in delightfully chaste Sanskrit.

*

Sri Shyama Shastry, unlike Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar, did not travel much; nor did he visit many temples. He was a rather reclusive person by nature; and, was greatly devoted to his own Mother Goddess – Bangaru Kamakshi, whom he regarded as if she were a living Goddess (Sakshat-pratyaksha-Devata) ; and, whom he worshiped, without fail, each morning, noon and evening (Tri-kaala-puja). He would scarcely be away from his Mother; and, hardly took out time to travel to other places

Apart from the place at which he was born (Thiruvarur) and Kanchipuram, a place of special significance to him, as being the home of his beloved deity Devi Kamakshi, Sri Shyama Shastry is said to have visited only four other places: Thiruvanaikal/ Jambukeswaram, Pudukottai, Nagapattinam and Madurai.

Of these places, Kanchipuram was the farthest from Thanjavur (say 190 miles).And; the next distant places were Madurai (120 miles); Nagapattinam (60 miles); and, Pudukkottai (60 miles).

He did not seem to have undertaken temple-tour (Thirtha-yatra) to visit these towns. He might have gone there as and when needed, perhaps, on invitation, to participate in certain occasions.

*

While on the visit to those places, outside of Thanjavur, Sri Shyama Shastry prayed at some temples; and composed a few Kritis praising the presiding deity of those temples.

About twenty-two of his Kritis are addressed to Devi Kamakshi of Kanchi. Although he did visit the temple of Sri Kamakshi, situated in the city of Kanchipuram, all of those Kritis in praise of Kamakshi were surely not composed while he was at Kanchipuram.

His Kshetra-Kritis, apart from, at times, mentioning the name of the deity, do not give out much details of the temple, Deity or the Kshetra.

Perhaps, the few instances of Kshetra Mudra / Sthala-mudra that appear in his Kritis pertain to two or three Kritis out of the Nine he composed in praise of Devi Meenakshi of Madurai, while he visited her temple there.

In the Kriti ‘Devi nee Pada-sarasa’ (28-Kambhoji, Adi) the Sthala-mudra appears in the Anu-Pallavi, as: Sri Velayu Madhura nelakonna Chidrupini

In the Kriti Mariveregati (20-Anaandabhairavi, Misra Chapu) the Sthala-mudra appears in the first Carana as: Madhurapura-nilaya Vani.

Kadamba-kanana or Kadamba-vana usually refers to Madurai. The phrase Kadamba-kanana-mayuri appears in the opening line of the Pallavi in the Kriti Devi nee-paada-sarasamule (Khambhoji, Adi), which was sung by Sri Shyama Shastry at the Meenakshi temple in Madurai.

Apart from the Varnam ‘Samini rammanave’ (Ananadabhairavi-Ata Taala), a Sandesha, where the Nayika sends a message, through her maid (Sakhi) to her beloved Lord Varadaraja; and, the Kriti ‘Sami nine nammiti’ (Begada Adi Taala) praying to Muthukumaraswami of Vaitheeswaran-koil, all the other songs of Sri Shyama Shastry are dedicated to the Mother Goddess in her various forms and names; as:

Kanchi-Kamakshi; Bangaru-Kamakshi; Brihannayaki; Akhilandeshwari; Brihadamba ; Meenakshi; Dharma-samvardhini; and Nilayatakshi – enshrined in various Kshetras (temple-towns).

As many as of his 35 compositions are dedicated the Goddess Kamakshi – either as Kanchi-Kamakshi (16 Kritis); Kamakshi (8 Kritis); Kamakoti (6 Kritis); or as Bangaru Kamakshi (5 Kritis).

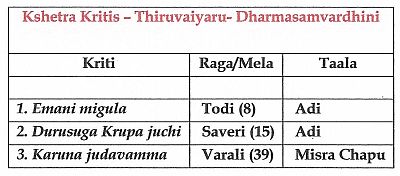

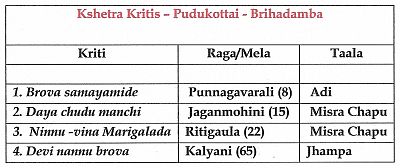

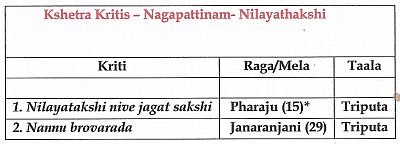

There are also Kritis addressed to the other forms (Rupa) and names (Nama or Abhidana) of the Mother Goddess as: Madura Meenakshi (8 +1 Kritis); Akhilandeshvari (5 Kritis); Brihannayaki (5 Kritis) ; Brihadamba (4 Kritis); Dharma-samvardhini (3 Kritis); and, Nilayathakshi ( 2 Kritis)

Thanjavur

Sri Shyama Shastry was entirely devoted to the Mother Goddess in her various forms. Even while he lived in Thanjavur for about 44 years, he did not seem to have composed any songs in praise of the presiding deity of the Great Temple of Brhadishvara.

He did, of course, compose five Kritis calling out to the Goddess of that temple – Devi Brhannayaki. Perhaps, if one so chooses, the group of these Kritis might be called ‘Brhannayaki-pancha-ratna-Kritis’.

Thiruvarur

Sri Shyama Shastry did of course visit Thiruvarur the place where he was born; and where he spent about twenty years of his early life during his childhood and adolescence. The holy Kshetra of Thiruvarur is the home of Lord Pancha-nadi-shvara and Goddess Dharmasamvardhini. Sri Shyama Shastry has composed three Kritis praising the Devi Dharmasamvardhini, specifically.

This, he did, of course, after he, along with his family, had moved out of Thiruvarur in order to settle at Thanjavur during the year 1783-84. In fact, the musical career of Sri Shyama Shastry commenced only after he left Thiruvarur.

Kanchipuram

Kanchipuram had a special significance to Sri Shyama Shastry. It is the seat of Kanchi Kamakshi, his Ishta Devatha; and, was the original abode of Bangaru Kamakshi, the deity he worshipped every day with utmost devotion.

However, most of his compositions dedicated to Kamakshi were composed by him while he was at Thanjavur. The scholarly opinion is that perhaps the Varna in Ananadabhairavi ‘Samini rammanave’ was dedicated to Lord Varadaraja of Kanchipuram. This Varnam is unique in another way too. Almost all of the compositions of Sri Shyama Shastry exude Bhakthi and Karuna Rasa. The Varnam ‘Samini rammanave’ is a rare instance of Madhura Bhakthi, where the Nayaki sends out a message (Sandesha) through her maid to her beloved Nayaka Lord Varadaraja of Kanchipuram beseeching him to come to her.

Other Kshetras

A few other places that Sri Shyama Shastry visited and composed songs in praise of the presiding deities of the temples there are said to be: Vaitheeswarankoil (Muthukumaraswami); Thiruvanaikal (Akhilandeshvari); Pudukottai (Brihadamba) ; Nagapattinam (Nilayatakshi); and Madurai (Meenakshi).

*

Thiruvanaikal / Jambukeswaram

In Thiruvanaikal / Jambukeswaram (near Tiruchirapalli) is the famous temple dedicated to Shiva where he manifests as Appu-Linga, the principle of the water-element (Appu or Jala). The Goddess of this Kshetra is Devi Akhilandeshvari, who is adorned with Sri Chakra inscribed in her earrings.

Sri Shyama Shastry composed five Kritis praising the glory of Devi Akhilandeshvari. The set of these five Kritis could perhaps be regarded as the Akhilandeshvari -Pancha-ratna of Sri Shyama Shastry.

Of these, the Kriti dedicated to Devi Akhilandeshvari– ‘Shankari Shamkuru-Chandra mukhi- Akhilandeshvar-Shambhavi- Sarasijabhava vandite- Gauri-Amba’(15- Saveri , Adi-Tisra-gati)- is indeed a masterpiece, a magnificent work of Art, which is very often sung in the Musical concerts.

The Kriti composed in highly lyrical Sanskrit is adorned with most delightful phrases for describing the beauty, virtues and splendor of the loveliest Devi; and, for addressing her with a range of suggestive names: Kalyani; Hara-nayike; Jagaj-janani; Bhavani; Bale; and Sundari etc.

The Kriti also praises the Devi through her countless virtues and powers, as: Sankata-harini; Ripu-vidarini; Sada-nata-phaladayike; Jagad-avanollasini; Angaja-ripu-toshini; Akhila-bhuvana-poshini; Mangala prade; Mardani; Marala-sannibha gamani; Sama-gana-lole; and, Sadarti- bhanjana-shile

It is a simple prayer followed by many phrases, invoking the blessings of the Goddess. There is joy, compassion, eagerness (Uthsukatha) and a sense of fulfilment (Dhanyata-bhava) in the Sahitya and in the Music as well. Unlike in some other Kritis, there is here neither sadness; nor pleading to the Mother to protect and rescue him from the miseries of life. He is requesting the Devi to grant happiness and wellbeing to all (Shamkuru).

Anupallavi

Sankata-harini; Ripu-vidarini; kalyani / Sada-nata-phala-dayike; Hara-nayike; Jagaj-janani

Carana (1, 2 and 3)

Jambu-pati-vilasini; Jagad-avanollasini; Kambu kandhare; Bhavani; Kapala-dharini; Shulini

Angaja-ripu-toshini; Akhila-bhuvana-poshini; Mangala prade; Mardani; Marala-sannibha gamani

Syamakrshra sodari; Shyamale; Satodari; Sama-gana-lole; Bale; Sadarti- bhanjana-shile

(Please check here for a rendering of the Kriti)

Pudukottai

The Seventh Century rock-cut cave temple of the Goddess Brihadamba is located near Pudukottai. Four compositions of Sri Shyama Shastry, all in Telugu, are said to be in praise of Brihadamba of Pudukottai. In all these Kritis, Sri Shyama Shastry prays to the Mother to protect him (Devi-nannu-brovavamma); to rid him of all sins (papamella pariharinci); and to show him love, compassion and mercy (Daya-chudu, Dayachesi varamiyamma Mayamma).

*

Nagapattinam

The ancient (6th century) shrine of Shiva as Kaya-rohana-swami and his consort Nilayathakshi is located in Nagapattinam, a coastal town. Sri Shyama Shastry two Kritis, in Telugu, in tribute to Devi Nilayathakshi.

* In some versions the Raga of this Kriti is indicated as Mayamalavagaula

Here, Sri Shyama Shastry again praises the Mother by an array of names: Adishakthi; Maheshvari; Kumari; Nilayathaksi-Jagathsaksi; Palita-sruta-sreni; Sama-gana-lole; Komala-mrudu-vani; Kalyani; Omkari; Shambhavi; and, Dhrama-Artha-Kama-Moksha micchedi . And, he requests the Mother to please protect him (nannu brovarada O Jagadamba dayaceyave) .

The epithet ‘Nada-rupini’ appearing in the last lime of the Third Carana of the Kriti Nannu-brovarada (Janaranjani) – Shambhavi O Janani Nada-rupini Nilayathakshi, reflects the term Nada-rupini (299) and Nada-rupa (901) of Lalita-sahasra-nama .

It is said; the Kriti Nannu-brovarada (Janaranjani) when it is rendered in Triputa-Tisra, its Chittasvaras and Svarasahitya are rendered in Madhyama-kala (?). The general practice appears to be sing Chittasvaras and Svarasahitya in Vilamba-kala.

Nava-ratna-malika

While on a Visit to Pudukottai, an unknown person is said to have suggested to Sri Shyama Shastry to have a Darshan of Devi Meenakshi of Madurai; to compose and sing songs celebrating her matchless (Aprathima) glory (Mahima) and splendour (Vaibhava).

Accordingly, Sri Shastry went to Madurai; sat in front of Meenakshi Amman ; and , is said to have composed a garland (malika) of gem-like (ratna-samana) nine excellent (Bhavya, Divya) Kritis exuding Bhakthi-rasa, mostly in Rakthi-ragas, set to attractive rhythmic structures; and, adorned with ornamental Angas like Gamaka, Chittasvara, Svara-sahitya and rhetorical beauties like Yati, Prasa etc.

Although this set of Kritis is titled as Nava-ratna-malika; meaning that it comprises nine splendid Kritis, there is much debate about composition of the group. Nevertheless, it has, customarily come to be celebrated as Nava-ratna-malika, the garland of nine gems.

In the early references, only the first seven Kritis were included under the series. And, the remaining two slots were left undecided. But, it was surmised that the other two Kritis might be in the Ragas Nattakuranji and Sri; without, however, specifying the lyrics of the Kritis.

Since, the only two Kritis composed by Sri Shyama Shastry in those two Ragas were ‘Mayamma nannu brova’ and ‘Karuna-judavamma’, they have been provisionally included in the list, despite the fact their lyrics do not mention either the name of the deity as Meenakshi or its Sthala-mudra as Madhura.

[In some of the versions, the Kriti ‘Rave Parvatha-raja-kumari’ in the Raga Kalyani is reckoned as the eighth Kriti in the series.]

[Please click here for the Text of the Nava-ratna-Malika Kritis in Sanskrit.]

The Raga Ahiri, an ancient melodic type, a Janya of Hanuma-todi, is said to be a difficult Raga; but, highly rewarding. It is a Raga with Sampurna Svaras, both in the Arohana and the Avarohana, with Vakra-Sanchara.

Ahiri is very well suited for portraying Karuna Rasa, seeking for compassion. It is an early morning Raga, giving out a sense of devotion and pathos; and, is deeply meditative.

The nature of the Raga Ahiri (Raga-bhava) is very apt for the Sahitya of this Kriti.

The Kriti, starts with an emotionally charged call to the Mother , pleading with her ‘ Oh Amba, why do you not respond and talk to me even when I call out to you several time as My Mother’ (Mayamma Yeni pilichte, nato matadarada , Amba).

Sri Shyama Shastry, the devotee, who calls himself a child (Bidda, Biddayani), affirms his unflinching faith in his Mother Goddess. The Raga, the emotive content and the lyrics set in simple, childlike, innocent appeals to the Mother, are all in harmony.

The Kriti follows the Tri-Dhatu format; and, has Pallavi-Anupallavi followed by three Caranas. The first two Caranas have six lines (Paada) each; and the Third Carana has seven lines.

The Pallavi is in Vilamba-kala; but, the First Carana – Sarasija bhava Kari Hara-nuta Su-Lalita- commences as if in Madhya-gati.

*

Normally his Kritis set in Adi-Taala commence in Vilamba-kala; and, all its Angas (Pallavi, Anupallavi and Carana) will be set in the same tempo.

But, in the case of this Kriti (Mayamma Yani), because of the increase in the number of words used in the Carana, the tempo of the Carana is made to pick up. And, the Carana commences as if it is in Madhyama-kala

That goes along with the Mano-bhava of the Sahitya. The Pallavi commences with the pleading in Vilamba-kala, imploring the Mother to talk to him. ’ Is it fair on your part Meenakshamma not to respond even when I call you as my Mother? You are my only resort; who else is there for me?(Ninnuvina vere gati yavarunnaaru)

Then, after a while, he seems to get impatient; and, starts to protest, as a child does. The tempo of the music in the Carana quickens with the line ‘Sarasija-bhava-Hari-Hara- nuta-su-lalita’; and, moves up to Madhyama-gati. And, pelts the Goddess with questions: Are you not generous (nera datavu gada)? Don’t have compassion for your child (bidda-pai goppa-ga daya-rada)?

A remarkable feature of the compositions of Sri Shyama Shastri is the coordinated movement of its Mathu and Dhatu along with emotional content (Bhava) of the Sahitya and its corresponding Svara structure.

2 .Meenalochana -brova (8-Dhanyasi, Misra Chapu)

The Raga Dhanyasi is again a Janya of Hanuma-Todi. It again is a Raga apt for making an emotional appeal.

Sri Shastry pleads with the Devi Meenakshi (Meenalochana): why are you hesitating to protect me? And, he cajoles her by praising her in many ways, saying: Oh Devi, the one who rejoices in music, there is no one who is equal to you in this world.

And, he pleases the Mother by describing and admiring her beauty and splendour through many evocative phrases and epithets such as Gana-vinodinI, Minalochana, Kundaradana, and Niradaveni etc.

The Carana with lyrical rhythmic (Prasa-baddha) words describes the beauty of Devi Meenakshi: Kunda-mukunda-radana; Himagiri-Kumari; kaumari-Parameshvari; Kama paalini; Bhavani; Chandra-kala-dharini; neerada-veni.

The Kriti has Pallavi and Anupallavi of equal length/ duration having 8 Avartas each; followed by three Caranas, having uniform Dhatu (Music). The Carana is of 16 Avaratas duration.

[Normally, the duration of Avartas in the Adi-Taala Kritis is 2-2-4 for the Pallavi, Anupallavi and Carana, respectively. But, in the case of the Kritis set to Misra-Chapu-Taala, they follow the pattern of 8+8+16 for the Pallavi, Anupallavi and the Carana, respectively. And, if Svarasahitya is appended to the Carana, it would then mean another eight Avartas, by taking the Svara and Sahitya parts together as a single unit.]

The Kriti is sung either with the Misra Chapu or the Viloma Chapu. The application of the complicated rhythmic cycle of Viloma Chapu would seem lend greater clarity to the Raga-svarupa of the Dhanyasi.

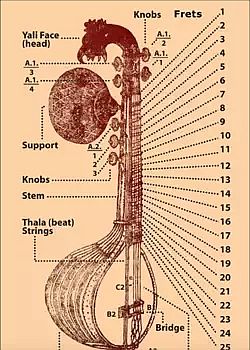

[It is said; after Sri Shyama Shastri rendered this song sitting in presence of Devi Madura Meenakshi, the temple authorities awarded him the highest honour that the temple could confer on any devotee. He was presented the Pattu-saree worn by the Goddess as Devi-prasadam. He was also gifted with a Tambura, with the figure of Yali ( a mythical beast) facing upright- Yali mukha.]

The Raga Lalita is a Janya of the 15th Melakarta – Maya-malava-gaula; and, shares many characteristic Prayogas with Raga Vasantha, having similar scales. It suits the import of the Kriti which pulsates with emotions imploring Devi, Bhakta Kalpalata (the legendary wish-fulfilling creeper) to protect him quickly (vegame). As the Kriti progresses, the pitch of the notes also ascend, implying the increasing eagerness (Utsukatha) or anxiety (Cinta) of the devotee.

The Kriti is structured in Pallavi, Anupallavi and Four Caranas. The Caranas are sung to the same Dhathu.

This is one of the four Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry (among the sixty) that has Four Caranas.

Vilōma Chāpu (4+3) can be seen in the Pallavi, where the Kṛiti starts in viṣhama graha

The Raga-mudra is in the opening line ‘Nannu brova Lalita‘.

The phrase ‘ Nannu brovu , Ninnu vina‘ is an instance of Sharaba prasa.

In the second Caraṇa, the Devi is addressed with prāsa or rhyming words like ‘purāni vāni indrāni rāni‘.

The second Carana has a string of phrases of literary beauty, praising the Mother Goddess Lalita, the Queen (Rani): Purani-Vani-Indrani- Vandita Rani- Ahibhushana – nuni Rani.

One of the terms used in the Fourth Carana, like – ‘Sumhendra-madhya-nilaye ‘and ‘Maha-rajni’ – resemble the phrase occurring in the Lalita-sahasra-nama as ‘ Sumeru-madhya-shrungastha’.

There are several such instances in his other Kritis as well; such as: Maha-Tripurasundari; Kadamba-vanavasini; Kadamba-kanana-mayuri; Kadamba-kusuma-priya; Nadarupini; Raja-Rajeshvari; Samagana-priya (Vinodini); and, Vishalakshi so on.

This Kriti, again, is sung with Misra Chapu or with Viloma-chapu Taala

Raga Anandabhairavi, a Janya of the 20th Melakarta Nata-Bhairavi, is a traditional Raga, which evokes Karuna Rasa. Sri Shyama Shastry is particularly associated with the Raga Anandabhairavi; and, two of his compositions in this Raga – Marivere and O Jagadamba – which are adorned with Chittasvara-Sahitya , are often sung in the Musical concerts.

Here again, in this Kriti, Sri Shyama Shastry pleads and appeals to the mercy of the dark hued-like-a rain-bearing-cloud (Ghana-shyamala)- the infinitely compassionate (Apara-krupa-nidhi) Mother Goddess : Oh Mother, who else is there in this world to protect me, but for you? You are my sole redeemer; I trust you implicitly; do rescue me (rakshimpa) – Marivere gati evvaramma mahilo nannu brochutaku.

*

The Kṛiti ‘Marivēre-gati’, set to Chapu-Taaḷa with a Viḷamba-Laya, is another splendid example for Sri Shyama Shastry’s genius. It explores the Raga Anandabhairavi in depth.

The Kriti is adorned with many Jaru-Gamakas, like ‘Sa-Sa/Sa’ and ‘Sa/Ma’ for the Sahitya- phrase ‘Saranagatha’ and ‘Rakshaki’. The Svarakshara pattern ‘Pa-Dha-Pa-Ma’ for the word ‘Padayuga’ in the Chittasvara-Sahitya in Vilamba-kala provides much depth to the emotional content of the Kriti.

The phrase ‘Nammiti’ occurring twice over in succession shows the depth of trust he has in the Mother Goddess.

And, a slow ‘Janta’ phrase ‘Ni-Ni—Sa-Sa—Ga -Ga—Ma-Ma’ for the Sahitya ‘Niratamu ninnu’ in the Chittasvara is another feature highlighting the Mano-Dharma of the Anandabhairavi Raga.

In the phrase ‘Pa-Ma-Ga3-Ga3-Ma’, the Anya-Svara Ga3 is well demonstrated.

The Gamaka for the phrase ‘Ma—Ma-Ga-Pa-Ma—Ga-Ri’ blending very well with the words Shyamala’ is another instance of a good coordination between Svara and Sahitya.

The phrase ‘ R—Sa-Ni-Dha-Pa—Dha-Pa-Ma-Ga-Ri—Ga—Ma’ in the Chittasvara is graced by the flavour of the Raga Anandabhairavi.

*

This Kriti described as a Chowka-kala-Kriti has, in its structure, Pallavi, Anupallavi, Chittasvara, Svarasahitya and Three Caranas.

Normally, in the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry, the Music setting (Dhatu) of the three Angas are separate. And, all the Caranas are sung in the Dhatu that is set for them.

But, here, in this Kriti, the last two lines of the Carana are sung to the Dhatu that was set for the Anupallavi.

The Kriti Marivere in Anandabhairavi Raga in Misra-Chapu Taala is found with 8-8-16 Avartas; and, also with a Chittasvara for another eight Avartas

Most of the Kritis in Misra-Laghu or Misra-Chapu are found with the pattern 8+8+16; and, only in some Kritis , the additional element Svarasahitya is found for another eight Avartas , taking into consideration the Svara part and Sahitya part as a single unit.

The music settings of the three Angas are separate and all the Caranas are sung to the same Dhatu in the compositions of Shyama Shastri. Only in rare cases, for example, in the Kriti ‘Marivere’ in Ânandabhairavi and ‘Brôvavamma’ in Manji Raga, the last two lines of the Carana are sung to the same Dhatu as that of the Anupallavi.

*

There are some Kritis in which pauses occur in different places i.e. at the end of the Pallavi; at the end of the first Avarta; and so on. There are Kritis which do not have pauses in between the Avartas; but, pause occurs only after finishing the Pallavi at the end of the second Avarta.

For example, in the Kriti ‘Durusuga’ in Saveri Raga, we find pause only at the end of the Pallavi, whereas In the Kriti ‘Marivere’ in Ânandabhairavi Raga, we find a pause at the end of the first Avarta itself in both the lines as : Marive ……| ……re | ga ti ye vva | ram … ma ||Mahilo ……| …….I. | mahilo ….. | brocu taku ||

**

The Kriti is set in Misra Chapu Taala

**

The Kriti abounds in rhythmic beauties like Chittasvaras, Samvadi Svaras flowing in succession; and, often linked by the Jaru-Gamakas. Four to five Sangatis are also sung to the Pallavi.

According to Smt. Sharadambal: The Svarasahitya here starts in Shuddha Svarakshara as: P; ; ; D P M | Pa da yu ga … There are many Svaraksharas here and there, throughout the Svarasahitya

Regarding the tempo of the Svarasahitya, Sri Shyama Shastri has not introduced Madhyama-kala through this element.

In the Kriti’ Marivere’ in Anandabhairvai, there is an appearance of an increase in the tempo. In the Pallavi, Anupallavi or Carana of this Kriti, we find the numbers of Sahitya syllables are four or five in one Avarta while they are six or seven in an Avarta in the Svarasahitya passage. For example; here the number of Sahitya letters are as follows:

Pallavi – Marivere || . . . . . re || gati Evva || ram ma ||

*

Smt. Sharadambal explains: In the Svarasahityas of the two Kritis ‘Durusuga’ and ‘Marivere’ of Sri Shyama Shastri, we also find patterns in the organisation of the Svaras.

In the Svarasahitya in Saveri Raga Kriti Durusuga, the Svaras are formed in Tisra (npd- srs) and Khaòda patterns (mpmdp- sndrs).

In the Ânandabhairavi Kriti ‘Marivere’, the Janta-svaras and the Dhatu-svaras figure (nnssggmm- janta) (psnd, pndp, dpd – datu).

In both these Svarasahityas we find a pattern of svara at the end.

- Durusuga – g R s n d – r S n d P – g r n; para kusalu – parâdiyani – vipudu

- Marivere – n s n r S – n d p P – m g r G m; dharalonata – vanakutu – htaïa…..ni vega

*

The Svarasahitya of this Kriti is said to be an example for Gaja-tana, where the grouping of the Svaras resemble the gait of a majestically slow moving elephant. The text of the Svarasahitya, which follows the Third Carana, in fact, compares the leisurely walk of the Devi to that of an elephant in Musth (mada gaja gamana)

paada yugamu madilo dalaci koriti vinumu mada gaja gamana / parula nutimpaganE varam(o)sagu satatamu ninu madi maravakane / madana ripu sati ninu hRdayamulo gati(y)ani dalaci stuti salipite / mudamuto phalam(o)sagutaku dharalo nat(A)vana kutUhala nIvEga (mari)

Kambhoji, an ancient and a popular Raga, is a Janya of the 28th Melakarta Harikambhoji. It is classified as a Ragini (female); and is said to be suitable for conveying the sentiments of Srngara (romantic), Hasya (humorous) and Karuna (pathos).

Here, again, Sri Shyama Shastry surrenders at the feet of the Devi who embodies the supreme consciousness (Chidrupini) who resides in Madhura; and, entreats her saying that there is nowhere else he can go. You are my one and the only shelter;

Devi-nidu-paada-sarasmule-dikku.Vere-gati-evaramma-Madhuralo-nelakonna Chidrupini Sri Meenaksha-amma?

The epithet Chidrupini here, resembles the term Chidakarasa rupini in the Lalita-sahasra-nama

This is a fairly lengthy Kriti having Pallavi, Anupallavi and Three Caranas; each Carana having seven lines (Paada). The Pallavi and Anupallavi have two Avartas each. And, each Carana, having eight Avartas each, is almost four times the length of the Pallavi.

The Kriti is set in slow moving Chowka-kala. The Music (Dhatu) of the Caranas is uniform.

The Taala is Adi Taala.

*

Prasa is a type of Sabda-alamkara, a literary embellishment. It mainly involves rhyming, where the first letter or the second letter is repeated between the Avartas. The Antya-prasa is the repetition of a letter or group of letters at the end of the Avarta.

It is said; with regard to the occurrence of the Prasa-aksharas in the compositions of Sri Shyama Shastry, they can be divided into four categories,.

- Dhirgha (long) syllables preceding the Prasa-akshara in the Carana alone.

- Dhirgha (long) syllable precedes in the all the three Angas.

- Hrasva (short) letter is found throughout the composition.

- Dhirgha (long) syllable is found in Pallavi and Anupallavi; and, the Hrasva (short) syllable is used in the Carana.

This Kriti ‘Devi nee paada sarasamule’ (Khambhoji) is cited as an instance where the both the long and the short syllable are used in the Kriti.

*

[The Kriti in Shankarabharanam (Devi Mina netri) and the Kriti in Kambhoji (Devi nee pada) commence with similar Sahitya and Svara (Pa, ma magagagaa; De-vee). But, the manner in which the Svaras are treated and rendered brings out the difference in the Raga-svarupa of the two Ragas. Only the deft handling of such Ragas can ensure maintaining their individual characteristics.]

6..Devi Mina netri (29- Shankarabharanam, Adi)

Dhīra-śankarābharaṇaṃ, commonly known as Śankarābharaṇaṃ, is the 29th Melakarta. Since this Raga has many Gamakas (ornamentations), it is also called as Sarva-Gamaka Maṇika-Rakthi-Raga.

The nature of this Raga is mellifluous and smooth; spreading a feeling of joy and exhilaration.

In this Kriti- Devi Meena-netri brovarave dayacheyave, brovaravamma; Sevinchevari-kellanu Cintamaniyaiy-unna ra – Sri Shyama Shastry again requests the Mother Goddess to protect him. He praises her as Chintamani, the most precious magical gem that spreads joy and dispels darkness and sorrow. She indeed is the Chintamani (the wish-fulfilling gem) for all those who seek her protection.

The Kriti Devi-meena-netri consists of Pallavi, Anupallavi, Chittasvara and three Caranas, which are lengthy and are adorned with literary beauties like Varna-alamkara, Prasas etc.

This is a Chowka- kala composition with two Avartas for the Pallavi and Anupallavi; and, with eight Avartas for the Carana. The Chittasvara is sung in two degrees of speed. [His other Kriti in Shankarabharanam is in the Madhyama-kaala]

*

The Prasa prayoga can be seen in the array of words : Baala-Chaala-meeḷa-kaalasheela-leela

Chittasvara here is very attractive .

The Kriti is set to Adi Taala.

*

Vidushi Smt. Vidya Shankar explains in her article Tala-anubhava of the Music Trinity

It is said; In an Avarta or elongation of the last syllable creates a pause for a few seconds. This silence itself is music. This enriches and enhances the atmosphere of melody by giving emphasis on the phrase that follows, with the expressions through Bhava and Raga.

The Carana of the Vilambita- Kriti, ‘Devi Meena-netri ‘(Shankarabharanam), is often cited as an illustration of this aspect.

The Raga-svarupa is captured in the very commencement of the composition, within the first half-Avarta, crowning with Arudi on the dot of the Druta.

The other Kriti of Sri Shyama Shastry ‘Devi-nee-paada-sarasa’(Kambhoji) , which starts with similar Mathu (Sahitya) and Dhatu (Svaras) , in a similar manner, with its Svarakasharas ‘pa da saa’ establish the Raga-lakshana.

*

Smt. Sharadambal offers expert comments as: The kriti Devi-meena-netri centres round Madhya-sthâyi, with occasional touches of Mandra-sthâyi and Tara-sthâyi. The Graha-svaras of the various Angns are: Ma, Ga, Ma (Pallavi); Sa, Pa, Ma, Pa (Anupallavi); and Ga, Ma, Pa (Carana).

Though the words are relatively less in this Kriti, use of Dhirgha- Svaras is limited; and , the Tara- pulse is filled with more ‘Aaa-karas’.

This Kriti is again in Raga Shankarabharanam. This, along with the Kriti Devi Meena-netri, is considered as twin Yugala-Kritis. Both are in Raga Shankara- bharanam; and, have similar notations (Svara-sthana).And, both are in Telugu.

The Kriti, commencing with asvarakṣara sāhitya in the PallaviSaroja-dala-netri-Himagiripurti-nee-padambuja-mulane-sadaa-nammi-nanamma-shubhamimma-Sree Meenakshamma – is a highly popular Kriti; and, is very often sung in the Musical concerts.

In this Kriti, Sri Shyama Shastry sings of the beauty, glory and the noble virtues; and, of the boundless compassion and generosity of the most enchanting Goddess Devi Meenakshi. He calls her as the treasure-house of all the noble virtues (Gunadhama); and as one who delights in Music of Sama (Sama-gana-vinodini). And, requests her to bless him and wish him well (Shubha).

Sri Shastry compares the enchanting beauty of her eyes to the lotus petals (Saroja-dala) ; and her face to the radiant moon (Indu-mukhi) .

The Kriti consists of Pallavi, Anupallavi and three Caranas. All the segments of the Kriti are set to the same Music (Dhatu).

*

The Sabda-alamkaras are introduced in the Anupallavi through a string of lyrical phrases (Sahitya) – Purani-Shukapani-Madhukaraveni-Sadashivuniki-Rani.

*

The Kriti is set to Adi Taala.

*

Smt. Sharadambal observes regarding the tempo or Kala-pramana of the Compositions:

Though, most of the songs of Shyama Shastri are in slow medium tempo in Adi-Taala, here are some songs in fast medium tempo.

The songs in Misra-Chapu and Triputa-Taalas also are mostly sung in slow medium tempo. The long drawn out rhythm with many pauses is seen in Chapu-Taala compositions with less number of words; and, with pauses here and there are found in these Kritis.

Some of his compositions in Adi-Taala have a tight knit relation between the Taala–Aksharas and the Sahitya letters. Almost all the Svara-letters have Sahitya-letters; and , Hrasva letters found in profusion.

For example, songs like’ Sarojadala-netri’ in Shankarabharana Raga; and in ‘Devi Brova’ in Chintamani Raga, though are set in Adi-Taala, the tempo seems to be increased and gives the impression that the song is set in Madhyama-kala. We do not find extensive pauses in these songs. The pauses are limited ;and, words are many and this appears that the tempo is increased.

The songs set in Adi-Taala, Rupaka and other Taalas are set in fast medium tempo. ‘Parvati-ninnu’ in Kalkada, ‘BiranaVaralicci’ in Kalyani can be cited as examples. Thus we find three different tempos such as slow, slow medium and fast medium tempos among the compositions of Shyama Shastri.

*

The Kriti ‘Saroja-dala-netri’ starts from Tara Sa ; and , comes down to Madhyasthâyi in the Pallavi , ending with a Prayoga in the descending order as ‘s-n-d-p-m-g-r-s’. Both Anupallavi and Carana centre round Tara-sthâyi, after starting from the note as ‘s-Ss’ and ‘P- pppm’, respectively. The upper limit is only Tara ‘Ga’. The ‘Sn-P’ and ’sd-P ‘are the visesha –prayogas found in this kriti. The Jaru prayogas are found in the Anupallavi as ‘s-Ss/Sss’ and ‘mP/sdP’.

*

The Sangathi, the melodic variations that are improvised while rendering the Pallavi or Anupallavi (rarely in Carana), without, however, altering the Sahitya is a much used Anga in the Kritis of Sri Thyagaraja. But, Sangathi is not a major issue in the Kritis of Sri Shyama Shastry.

But, now while singing the Kriti Saroja-dala-netri’ (Shankarabharanam) the Sangathis are developed by the performers and extended over the whole Avarta in the second line of the Pallavi. The First Sangati is developed from the place ‘Sri Meenaksamma’; while the second is developed from the beginning with slight changes occurring here and there.

Nattakuranji is described as an Audava Janya Raga of 28th Melakarta Harikambhoji. It is an asymmetric Raga, having three types of ascending (Arohana) and descending scales (Avarohana).All the three types, as well as other Prayogas are in use.

In this Kriti commencing with the Pallavi – Mayamma nannu brovavamma Mahamaya Uma – Sri Shyama Shastry pleads with the Mother; and, questions her ‘ O Mother of Shyamakrishna (Shyamakrishna–Janani) why (ela) are you delaying (tamasamela) , please come and protect me (Nannu brovu).

This is a relatively short Kriti; having Pallavi and Anupallavi of one Paada (line) each; and, a Carana of two lines. The Carana is followed by Svarasahitya structured in two lines (Paadas).

With a series of vowel extensions, the Kriti is better suited for Vilamba-laya rendering

The Pallavi starts on Madhya-sthayi-madhyama (M;) – the Jiva-svara of the Raga with Svarakshara (Ma-yam-Ma).

The Anupallavi, with a series of lyrical sounding terms ending with the vowel Aa (अ) Satyananda-Sananda-Nitya-Ananda-Ananda-Amba, describes the cosmic nature of the Mother as being the very embodiment of eternal (Nitya) bliss (Ananda). This line is extended by a series of Svaras.

The Svarasahitya is appended to the Carana addressing the Mother in a series of beautiful names as: Sarasijakshi; Kanchi Kamakshi; Himachalasute; Suphale; Marakatangi; and, Maha-Tripura-Sundari

mAdhavAdi vinuta sarasijAkSi Kanci-KAmAkSi tAmasamu sEyakarammA / marakatAngi mahA tripurasundari ninnE hrdayamupaTTukoni

*

The Kriti is set to Adi Taala

The ancient Raga Sri is described as the A-sampurna-Melakarta equivalent of the 22nd Melakarta Kharaharapriya. It is one of the Ghana-Ragas of the Karnataka Samgita; and, is regarded as a very auspicious Raga.

And, it is apt to conclude the splendid series of Nava-ratna-malika with this Mangala-kara Raga submitted to Devi Brhannayaki.

The kriti is structured into Pallavi, Anupallavi and three Caranas. And, the Carana ends with the line: Tamasambu itu-seyaka naa paritapa-mulanu pariharinchi-nanivu; please, without any further delay, relieve me (pariharincu) of my miseries (paritapa-mulanu).

As regards the Taala, there are two practices; either to sing in Viloma Chapu Taala; or in the Adi Taala. Both seem acceptable.

Technically, this composition could be said to be set in Telugu. But, except for the verbs and the appeals made to the Mother all the other terms either describing the beauty of the Goddess or addressing her through a a string of melodious names are in chaste Sanskrit

The most graceful Devi, who delights in Music (Gana-vinodini) is lovely to look at, having a beautiful face (Sunda-radana); her complexion glowing like gold (Hemangi); her hair dark as the rain-clouds (Ghana-nibha-veni); and, her stately walk, as the gait of an elephant (Samaj-gamana).

Sri Shyama Shastry with great Love and admiration calls his Mother with a variety of names: Sarasija-asana; Madhava-sannuta, Brhannayaki; Lalita; Hima-giri-putri; Maheshvari; Girisha-ramani; and , Shulini.

In some of the versions, the Kriti ‘Rave Parvatha-raja-kumari’ in the Raga Kalyani is reckoned as the eighth Kriti in the series.

The Kriti ‘Rave Parvata Rajakumari’, is set in the familiar Raga Kalyani; and, in Taala Jhampa.( This, somehow, is labelled as a ‘rare-kriti’)

This Kriti is dedicated to Devi Meenakshi. It has the Pallavi, Anupallavi and Two Caranas.

In the Pallavi and Anupallavi, Sri Shyama Shastry again requests the Mother to listen to him; to protect him; and to come quickly to him- Rave Parvata Rajakumari, Devi nannu brochutaku vegame. He pleads: O Mother have I not been trusting you; have I not regarded you as my sole refuge- Neeve gatiyeni nammiyunti-gada; Neeve gatiyani nammiyunti Amma.

The two Caranas sing the greatness of the beautiful (Nirada-veni) Mother of all the three worlds (Tri-Loka-janani) , who is worshipped by all the gods; whose glory , auspicious legends and victories are sung and extolled by many sages; and, who protects (rakshaki) and brings delight (toshini)to the virtuous world of gods.

O Mother Meena-locani, the princess, the daughter of Parvatha-raja (Parvata-Rajakumari) the benevolent (Udaara-gunavati) ancient Goddess (Purani), kindly (krupu-judu) rid us of all fears (Abhaya) and protect us all (brovu).

In all the nine compositions, the Sri Shyama Shastry seeks Devi’s help and protection, praising her glory, splendour and her countless virtues. The beauty and loveliness of the Devi is depicted in every Kriti . There is a child-like innocence, admiration and Love for his Mother (Mayamma), pleading with her repeatedly, with an open-hearted affection, to protect him and rescue him from the surrounding mundane existence. These Kritis exude a sense of tenderness, optimism and immense faith in the Mother.

Overall in these Kritis, the verbs and the appeals made to or the conversation with the Mother is in the day-to-day commonly spoken Telugu, with informal colloquial expressions. Though they do not possess philosophical ideas in profusion, they do express the natural filial affection and tenderness of the child trying to reach the Mother.

But, the descriptions of Devi’s beauty , splendour and her infinite powers and virtues; as also her varied names are all recited in graceful, refined, lyrical Sanskrit. These passages are pure poetry; they are simple and elegant. There are many passages with a string of adorable phrases with prosodic beauties in harmony with the Music.

The Kriti mainly appeals to the beautiful Goddess of lotus-petal-like radiant eyes (Pankaja-dala netri) by addressing her through a variety of sweet-sounding names; Shankari; Karunakari; Raja-rajeshvari; Sundari; Paratpari; Gauri; Giri-raja-kumari; Parama-pavani; Bhavani; Katyayani and Kalyani so on.

Both the familiar major Ragas and the minor Ragas like Ahiri and Lalita have been skilfully employed. The introduction of brilliantly crafted Chittasvaras, Svarasahitya etc, excelling in poetic beauty, have added sparkle and lustre to these Kritis.

Similarly, the application of the Misra Chapu Taala and Viloma Chapu Taala ; as also the Gamaka Prayogas of tender oscillations and glide, have lent depth as also amazing agility to the movement of the Musical phrases in the progression of the latter parts (Carana) of the Kritis. This comes out vividly in contrast to the Vilamba-kala elaboration of the Pallavi and Anupallavi passages.

For instance; in the Kriti Mayamma (28-Nattakuranji, Adi) the Pallavi commences in Vilamba-kala, with straight notes pleading for affection and understanding. Later, with the Kampita (Oscillations) of the Gamaka-prayoga, the same set of Svaras gathers momentum to express the urgency of his pleas. A sense of loveliness, joy and abundant faith in the Love of the Mother permeates this Kriti.

At the conclusion of the Nava-ratna-malika it is customary to sing the most pleasing and lovely Mangala-Kriti (Shankari-Shankari, Kalyani, Adi) , a benediction (Svasthi-vachana)-a prayer entreating for divine blessings , the good- hearted Vidwan, the child (Shishu) of Shankari, humbly appeals to his Mother, the Supreme Goddess Raja-Rajeshvari , who is the very embodiment of all the spiritual knowledge (Tattva-jnana-rupini) and one who enlightens all (Sarva-chitta-bohini ) to bless and grant (Disa) all of this existence (Sarva-Lokaya) happiness , prosperity (Jaya) and wellbeing (Shubha)

– Mangalam– Jaya Mangalam – Shubha Mangalam

पल्लवि

शङ्करि शङ्करि करुणा-करि राज

राजेश्वरि सुन्दरि परात्परि गौरि

अनुपल्लवि

पङ्कज दळ नेत्रि गिरि राज कुमारि

परम पावनि भवानि सदा-शिव कुटुम्बिनि (शङ्करि)

चरणम्

श्याम कृष्ण सोदरि शिशुं मां परिपालय शङ्करि

करि मुख कुमार जननि कात्यायनि कल्याणि

सर्व चित्त बोधिनि तत्त्व ज्ञान रूपिणि

सर्व लोकाय दिश मङ्गळं जय मङ्गळं

शुभ मङ्गळं (शङ्करि

In the next Part we shall discuss about the structure, the language and other elements of the Kritis composed by Sri Shyama Shastry

Continued

In the

Next Part

Sources and References

- Indian Culture, Art and Heritage by Dr. P. K. Agrawal

- Shodhganga chapter Six

- Shodhganga Chapter Seven

- Shodhganga Chapter VI

- Shodhganga Chapter VII

- Shodhganga handle

- A Voyage through Dēśa and Kāla

- Compositions of Shyama Shastri (1762-1827)

- Origin and development of Indian music

- https://archive.org/stream/composers00ragh/composers00ragh_djvu.txt

- https://archive.org/details/composers00ragh/page/46/mode/1up

- Prof. P. Sambamoorthy

- https://ebooks.tirumala.org/downloads/syamasasthri.pdf

- https://www.sangeethapriya.org/tributes/shyamakrishna/dl_krithis.html

- http://www.medieval.org/music/world/carnatic/shyama.html

- http://carnatica.net/special/shyama.pdf

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/173579/11/11_chapter%204.pdf

All images are taken from Internet

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

]

]