For my learned friend Prof. Dr. DMR Sekhar

As observed by the Supreme Court of India while dealing with the case of ‘Bramchari Sidheswar Shai and others Versus State of West Bengal’ (1995) the word ‘Hindu’ derived from the name of the river Sindhu originally referred to the region along the river Sindhu (now called the Indus) as also the people residing in the Sindhu region.

It is explained that Persia, in the ancient times, was the vital link between India and the Greeks of Asia Minor. In the Avesta of Zoroaster, what we today call as India is named as Hapta Hendu, the Avesthan for the Vedic Sapta Sindhavah – the Land of Seven Rivers, that is, the five rivers of the Punjab along with the Sarasvati (a river which has since disappeared) and the Indus. The word ‘Sindhu’ not only referred to the river system but to the adjoining areas as well.

And again, by about 516 B.C.E, Darius son of Hystaspes annexed the Indus valley and formed the twentieth satrapy of the Persian Empire. The twentieth Satrapy was the richest and the most populous Satrapy of the Persian Empire. The inscription at Nakshi–e-Rustam (486.BCE) refers to the tributes paid to Darius by Hidush and other vassals; such as Ionians, Spartans, Bactrians, Parthians, and Medes.

The name of Sindhu reached the Greeks in its Persian form Hindu (because of the Persian etymology wherein every initial ‘S’ is represented by ‘Ha’).The Persian term Hindu became the Greek Indos / (plural indoi) since the Greeks could not pronounce ‘Ha’ and had no proper ’U’. The Indos, in due course, acquired its Latin form – India. Had the Sanskrit word Sindhu reached the Greeks directly, they might perhaps have pronounced it as Sindus or Sindia.

All this was to explain that the word ‘Hindu’ originally referred to the river system; and to the adjoining areas; as also to the people residing in that region. The term was employed to denote regional and cultural affiliation; but, not a religious identity.

**

In the ancient times the concept of a distinct ‘religion’ as opposed to other ‘religions’ did not seem to exist. The Rig-Veda or the Upanishads or even the Buddha do not refer to a ‘religion’ or speak in ‘religious terms’. Even the later texts such as the Arthashatra of Kautilya or the Indica Megasthanese do not mention a religion per se that existed in India of their times.

[ It is said; in the whole of Sanskrit lexicon there is no term equivalent to what we now call as ‘religion’]

Even otherwise, what has now come to be categorized as ‘Hinduism ‘does not satisfy or fall within the accepted definition of a ‘religion’?

For instance; it has no Prophet or a Originator; its origin cannot be pinpointed to a time or place; it has no single source-text or the Holy Book; it is not identified with a particular symbol or an emblem; it does not prescribe (injunctions or list of Do-s – thou shalt) or proscribe (prohibitions or list of don’t-s- Thou shalt not) a set of beliefs or rules of conduct; it does not lay down a particular system of faith , dogma or worship ; there is no single Authority to issue mandates or edicts (Fatwa) for regulating or governing religious faith of its people; one cannot be excommunicated from its fold ; and by the same token one cannot m strictly speaking , converted to its faith; in fact it has no global ambition, intending to conquer the world; those within it have the absolute freedom to accept/reject/ abuse any or all of the gods ; any or all of the texts; one can accept or reject a superhuman controlling power according ones will; one can observe the time-honoured accepted customs , ceremonies and rituals or reject any or all of it with impunity and still profess to be a ‘Hindu’; and so on…

Further; what is now called Hinduism was not made; but, it has grown over the centuries. And during its long and circuitous route, in its metamorphosis, it has imbibed within it several tribal cultures by absorbing, transforming and reforming various cult and tribal beliefs and practices, many of which were vague and amorphous, ranging from sublime to grotesque . The Hinduism, as practiced today, is a continuing amalgam of hundreds of tribal cultures. The Hindu culture, philosophy and rituals are greatly enriched by such countless tribal cultures. But, all the while it did retain the ancient concept of an all-pervading, Universal entity from which everything emanates and into which everything eventually returns. Some describe Hinduism as an inverted tree or a jungle; but not a strictly planned structural building.

Thus what has come to be regarded as Hinduism is a peculiar, open-ended system that rejects all sorts of restrictions and defies a specific definition. That perhaps is the reason why the Supreme Court observed: ‘Hindu religion not being tied-down to any definite set of philosophic concepts, as such’.

The ‘Hindu’ view of life accepts – rather celebrates the pluralistic nature Truth or Reality, which cannot be , dogmatically, restricted or diminished to a particular single position. The ‘Hindu’ traditions have always tried to adopt the concept of Anekāntavāda which, essentially, is a principle that encourages acceptance of multiple or plural views on a given subject. It believes that merely judging the issue from individual (separate) stand points of view would lead to wrong conclusions; and, it would be prudent to approach each issue from more than one point of view (aneka-amsika). It also marks the tendency to harmonize opposing views as distinct parts of a larger whole whose fullness lies well beyond the reach of mere perception or reason.

Then the Question is: how did such an open concept that vaguely meant a geographical or a cultural association was brought down and restricted to mean a particular religious group as distinct from other such rival groups or sects.

***

Catherine A. Robinson, a Professor on the Study of Religions at the Bath Spa University in the introduction to her celebrated Book Interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gita and images of the Hindu tradition investigates and discusses , in fair detail , the course of ‘the changing meaning of ‘Hindu’ whereby an original ethnic and cultural meaning was much later superseded by a religious meaning’. Much of what follows hereunder is based on her work.

The very notion of religion (dian definiri religio), commonly translated as ‘a feeling of absolute dependence’,’ to tie or bind’, is primarily a Western concern. It is the product of the dominant Western religious mode; the theistic inheritance from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The basic structure of such theism is essentially a distinction between a transcendent deity and all else; between the creator and his creation; between God and man.

[On October 25, 2016, a Seven-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court of India headed by Chief Justice T S Thakur which had taken up a review of the judgement handed down by its Three-judge Bench in 1995, among other things , observed:

“It is difficult to define religion. There will be no end to this”. ]

***

According to Ms. Robinson: ‘Hindu’ did not, originally, designate religious significance or affiliation; nor did it distinguish among affiliations to what are now regarded as different ‘religions’. ‘Hinduism’, she says, is to be understood as a modern Western concept adopted and adapted by ‘Hindus’. And, it is , therefore, important to differentiate between ‘Hinduism’ as a contemporary phenomenon with ideological power and practical implications and the historical process that produced it, imbuing it with an appropriate past and aura of antiquity.

The change in the meaning of ‘Hindu’ from the ethnic and cultural to the religious occurred in two important phases during which ‘Hindu’ was defined negatively through the exclusion of Muslims ; and, then during the Western period , positively through the association of those identified as ‘Hindu’ with a single unified ‘religion’.

In the medieval period, in Islamic usage, ‘Hindu’ tended to denote an Indian who was not a Muslim. It was a negative criterion – non-adherence to Islam; as also a demarcation of the indigenous inhabitants from the foreign or invading populace in terms of ethnic, cultural or even religious distinctions. And later, a ’Hindu’ came to mean one who was not affiliated to any of the identifiable cults, beliefs and practices prevalent among the indigenous population.

In the modern period, as per the Western usage, initially, and in general, ‘Hindu’ signified an ethnic and cultural identity associated with the indigenous civilization of India. Later, ‘Hindu’, in particular, tended to denote an Indian who was neither a Muslim nor a member of another sect recognized as a ‘religion’

Let’s look at these phases in a little more detail.

***

Dr. Dileep Karanth, in his article ‘The Unity of India’ (Journal of the Indian History and Culture Society; 2006-7) explains:

According to Dr. D.P. Singhal (India and World Civilization, Rupa & Co., 1993), the earliest mention of India in Chinese chronicles occurs in the report of an envoy from the Chinese court to Bactriana. Here, India was referred to as Shen-tu. Dr. Singhal explains that the term Shen-tu can be philologically related to the word Sindhu (Indus).’

He says; the old Chinese name for India Shên-tu had been replaced by Yin-tu by the time Yuan-Chwang (602-664 CE), a Chinese Buddhist monk and traveler who traveled across India for 17 years, was visiting; and, it has remained that ever since.

In Chinese , ‘Hs’ pronounced ‘sh’, often represent foreign H. That is, the word ‘Shen-tu’ in Chinese may just be ‘Hindu’ transcribed.

And when Yuan-Chwang came looking for ‘Shen-tu’, he heard a word ‘Indu/Yin-tu’, which had become current in the borderlands of India; and, he began to make a note of it. Yuan-Chwang proposed an etymology for the name ‘Yin-tu’. India, he said, is named ‘Yin-tu, because, like the moon, its wise and holy men shed light even after the sun of the Buddha had set. (Incidentally, Indu, in Sanskrit means moon; and that might be reason why the Chinese chronicles explicitly use the pictogram for the moon to represent India.)

It is interesting to note that ‘Indu’ in Sanskrit could well be changed to ‘Hindu’ in Old Persian. The term ‘Hindu’ has been current among Greeks, Persians, and Chinese quite independently of the Arabs or the Muslims. It is widely believed that the term itself is the creation of foreign peoples (even if the idea is not).

*

Yuan-Chwang used the term Yin-tu to apply to the whole of the Indian subcontinent, inclusive of the Indo-Gangetic plain, Magadha or Kashmir and the southern peninsula. Yuan-Chwang also spoke of ‘Indian’ lands which were then under Persian rule. That is, Yuan Chwang could tell that a province was ‘Indian’ even if it happened to be under foreign rule. Yin-tu did not mean a religion.

The idea of an India has existed since classical times – since time immemorial, some would say. It has been celebrated in the classical literature of India, even though the name ‘India’ was not used. The civilizations that came in contact with classical India did perceive the very diverse peoples of the land as somehow ‘One’. And the term Hindu was not used to signify a religion.

The notion of an India thus has deep roots; and yet, its expressions at the surface may have changed with the times. The concept of India and Indian subcontinent is now broad enough to embrace all peoples whose homelands are contiguous to India, and who choose to celebrate the notion of an India.

***

Al-Biruni (973-1048) a Muslim scholar of Iranian descent is regarded as one of the greatest scholars of the medieval Islamic era, who distinguished himself as a historian and versatile linguist,. He arrived in India during 1017; and spent here number of years learning the local history, culture and languages. He also collected books on Indian philosophies, mathematics, medicine, astronomy and art, as practiced in 11th century India. During his stay, it is said, he learnt Sanskrit, befriended number of Indian scholars, and had discussions on verities of subjects.

Al-Biruni in his book Tarikh Al-Hind (History of India) , wrote about his impressions on almost every aspect of life in the India of his times (early 11th -century) as also about its history, geography, geology, science, and mathematics.

He observed: ‘the Hindus entirely differ from us in every respect’ they totally differ from us in religion; alongside in general cultural practices, language and custom’. The Hindu, in his work, generally denoted non-Muslims. And his description of the ‘Hindu’ was not particularly in terms of ‘religion’. It was meant to highlight the differences in the culture; rather than in religious beliefs and practices.

And within the hierarchy of ‘religions, as derived from the criteria that were close to Islam, those religious groups without a revealed book or fixed laws were ranked lowest.

The later medieval Muslim scholars adopted a similar approach. They too referred to the whole of the non-Muslim population as the Hindu; and, they did not seem to be aware of the diverse sects and cults within it or outside of it.

Accordingly, the medieval Islamic view of ‘Hindu’ was primarily to designate indigenous non-Muslim population and their way of life.

**

Medieval Church

It is said; according to medieval Christian belief, the entire population of the world was classified into four major religious groups: ‘lexchristiana, lexiudaica, lexmahometana and lexgentilium’; that is, Christians, Jews, Muslims and the rest ‘Heathens’. The ‘idolaters’- of any sort -, who were said to form roughly nearly two-thirds of the world’s population, were also grouped under ‘heathens’ (gentilium). It is explained; the concept of ‘heathen’ was derived from such Christian-world view; and its fourfold classification.

By about the sixteenth century, the native population of India (other than Jews and Muslims) were categorized by the Church and by the Europeans, in general, under lexgentilium- heathens and idolaters. And, till about the Eighteenth Century, the term Gentile, Gentio or heathen was applied to identify the Hindus and to distinguish them from the Moors (Muslims) of India.

Gentoo

The Portuguese (who perhaps were the earliest to colonize India) after they landed on the West coast found that the native inhabitants of India also included Jews and the Moors (Muslims). They did not quite know what those other indigenous pagan religious groups were called. But, the Portuguese named them as Gentoos – the native heathens. It is said; the Portuguese word ‘Gentoo’ is a corruption of the Gentio, meaning a gentile, a heathen, or native.

Thus, as early as in the sixteenth century, Gentoo was a term commonly employed, basically, to distinguish local religious groups in India from the Indian Jews and Muslims. The Oxford English Dictionary defines Gentoo as ‘a pagan inhabitant of Hindustan, a heathen, as distinguished from Mohammedan’.

[ Please also see India under British rule from the foundation of the East India Company by By James Talboys Wheeler (1824-1897),Published by Macmillan and Co., London – 1886

The administration of the East India Company – A history of Indian progress– by Sir John William Kaye (1814-1876) -Published by Richard Bentley, London – 1853

The Good Old Days of Honorable John Company- Being curious reminiscences during the rule of the East India Company from 1600-1858, complied from newspapers and other publications – by W.H.Carey -1882 ]

East India Company and the Code of the Gentoos Law

The English East India Company was founded in 1600 as a private joint-stock corporation under a royal charter granted by Queen Elizabeth I 31.12.1600. And, that gave the Company a monopoly over trade with India, Southeast Asia, and East Asia.

It was originally known as Governor And Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies .The first Governor was Thomas Smith; and, the Groups were known as ”Merchant Adventurers‟.

Hawkins was given 400 Manasabs by the Mughal Emperor Jahangir. In 1615, James I sent his Ambassador Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of Jahangir.

Initially , they started factory at Surat; in 1633 at Musulipattam . Later, they got Madras in 1639 from Raja of Chandragiri ; Fort St George was constructed in 1640 ; and, a factory was opened at Bangalore in 1642.

In 1661, the port region of Bombay was received as royal dowry from Portuguese for marrying their Princess Catherine Braganza with Charles II. The Company got it from the King in 1668 for an annual rent of 10 pounds.

In 1715, three villages Sutanati, Kalikota and Govindpur got by Hamilton gained firman in 1717, called magna-carta of the company

The company was governed in London by 24 directors, elected by its shareholders (known collectively as the Court of Proprietors). Profits from its trade were distributed in an annual dividend that varied during 1711–55 at between 8 and 10 percent.

The company’s trading business was carried on overseas by its covenanted “servants,” young boys nominated by the directors usually at the age of 15. Servant salaries were low (in the mid-18th century a company writer made £5 per year), and it was understood they would support themselves by private trade.

Between 1773 and 1833 a series of charter revisions increased parliamentary supervision over company affairs and weakened the company’s monopoly over Asian trade. In the Act of 1833 the East India Company lost its monopoly over trade entirely, ceasing to exist as a commercial agent and remaining only as an administrative shell through which Parliament governed Indian territories.

[Source : Modern India history modern India history at a glance general studies for prelims advent of the Europeans by Kritarth Srivatsava.]

The Coat of Arms of the British East India Company, with their slogan “Auspicio Regis Et Senatus Anglia,” Latin for “By the authority of the King and Parliament of England.”

In 1785 the East India Company directors sent Charles Cornwallis(1738–1805) to India as governor-general, an appointment Cornwallis held until 1793. Lord Cornwallis, who had just returned from America, where he presided over the surrender of British forces at Yorktown (1781), had a reputation for uncompromising rectitude. He was sent to India to reform the company’s India operations. His wide-ranging reforms were later collected into the Code of Forty-eight Regulations (the Cornwallis Code).

Cornwallis barred Indian civilians from company employment at the higher ranks . And, he also restricted the Sepoys (Indian soldiers) from rising to commissioned status in the British army. He replaced regional Indian judges with provincial courts run by British judges. Beginning with Cornwallis, the “Collector” became the company official in charge of revenue assessments, tax collection, and (after 1817) judicial functions at the district level.

Cornwallis’s most dramatic reform, however, was the “permanent settlement” of Bengal, which gave landownership to Bengali zamindars in perpetuity—or for as long as they were able to pay the company (later the Crown) the yearly taxes due on their estates. The settlement’s disadvantages became clear almost immediately, as several years of bad crops forced new zamindars to transfer their rights to Calcutta moneylenders. The Bengal model was abandoned in most 19th-century land settlements, in part because by then the government’s greater dependence on land revenues made officials unwilling to fix them in perpetuity. (Source)

Old Government House

Richard Colley Wellesley (1760–1842) , sent to India in 1798, ensured uncontested British dominance in India; and, augmented the imperial grandeur of Company rule by building, at great cost, a new Government House in Calcutta. He is reported to have remarked: “I wish India to be ruled from a palace, not from a counting house; with the ideas of a Prince, not with those of a retail-dealer in muslins and indigo”

[The East India Company directors in London only learned about the building (and its enormous cost), only in 1804. The building’s architect was Charles Wyatt (1759–1819); and, the design was modelled on a Derbyshire English manor, Kedleston Hall, built in the 1760s.

This drawing – a view of Government House, from the Eastward- is by James Baillie Fraser, ca. 1819. (courtesy of Judith E. Walsh)]

*

With the rapid spread of the British colonial environment and the rise of the East India Company, the British courts in India had to adjudicate on increasing number of legal disputes among the locals. The Court of Directors of the East India Company decided to take over the administration of civil justice ; and, felt that it would help its business interests if it could involve in what they termed as ‘Hindu learning’ to decide on civil matters.

Accordingly, Warren Hastings who was appointed as Governor General of Bengal in April, 1772 was asked to execute the Company’s decision; and, interalia come up with a ‘Judicial Plan’. His immediate object thereafter was to devise an arrangement to dispense law/justice to the Indian litigants in ways that are as close as possible to their own customs, in matters of person and property; and, particularly, on matters considered as religious. But, the dispensation of justice had to be according to the British norms and by British Judges; and it was made explicitly clear that employing the Indian scholars or pundits as judges was totally out of question.

Accordingly, Warren Hastings who was appointed as Governor General of Bengal in April, 1772 was asked to execute the Company’s decision; and, interalia come up with a ‘Judicial Plan’. His immediate object thereafter was to devise an arrangement to dispense law/justice to the Indian litigants in ways that are as close as possible to their own customs, in matters of person and property; and, particularly, on matters considered as religious. But, the dispensation of justice had to be according to the British norms and by British Judges; and it was made explicitly clear that employing the Indian scholars or pundits as judges was totally out of question.

By August 1772, Warren Hastings submitted his ‘Judicial Plan of 1772’. It declared that ‘in all suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste, and other religious usages, or institutions, the laws…of the Shaster with respect to Gentoos shall be invariably adhered to’.

[Pitt’s India Act 1784 or the East India Company Act 1784 was passed in the British Parliament to rectify the defects of the Regulating Act 1773. It resulted in dual control or joint government in India by Crown in Great Britain and the British East India Company, with crown having ultimate authority. The relationship between company and crown established by this act kept changing with time until the Government of India Act 1858 provided for liquidation of the British East India Company; and the transference of its functions to the British Crown.

Sir John R. Seeley, the 19th-century British historian, famously remarked that “the British Empire was acquired in a fit of absence of mind.”

The greatest single force in the expansion of that empire was the East India Company. Although in theory dedicated to trading by sea, the company gradually acquired vast areas of territory in Asia and found itself the ruler of a sixth of humanity.

After its somewhat inglorious demise following the Indian Mutiny, the Company was abolished in 1858. Its grandiose headquarters at East India House in the City of London were later demolished in 1863

The formal ceremony of handing over the British Crown from the East India Company to Her Majesty Queen Victoria was held at Calcutta

On November 1, 1858, at a grand Durbar held at Allahabad, Lord Canning released the royal proclamation which announced that the Queen had assumed the governance of India.

When, by the blessing of Providence, internal tranquillity shall be restored, it is our earnest desire to stimulate the peaceful industry of India, to promote works of public utility and improvement, and to administer its government for the benefit of all our subjects resident therein. In their prosperity will be our strength, in their contentment our security, and in their gratitude our best reward – Proclamation of Queen Victoria of Great Britain, 1858

Under the provisions of the Royal Titles Act 1876 , Queen Victoria assumed the title “Empress of India” , effective from 1 May 1876.. The new title was proclaimed at the Delhi Durbar of 1 January 1877 ]

Till about the eighteenth century, the native population of India (other than Jews and Muslims) were labelled by the British as Gentoos. That is the reason why the first digest of the Indian legislation drafted by the British in 1776 for the purpose of administering justice and to adjudicate over civil disputes among the people of India belonging to local religious groups was titled as A Code of Gentoo Law.

[The Gentoo Code is a legal code or a digest of Hindu law on contracts and successions, compiled by a set of by Brahmin scholars headed by Pandit Jagannath Tarkapanchanan . In its Sanskrit version , it was titled as Vivādārṇavasetu. It was first translated into Persian, which was official language of that time. And, later it was translated from Persian into English by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, a British grammarian working for the East India Company, for the use in courts of the East India Company as ‘A code of Gentoo laws’.

The translation was funded and encouraged by Warren Hastings as a method of increasing colonial hold over the Indies. It was printed privately by the East India Company in London in 1776 under the title A Code of Gentoo Laws, or, Ordinations of the Pundits. Copies were not put on sale; but, the Company did distribute them. In 1777 a pirate edition was printed; and, in 1781 a second edition appeared. Translations into French and German were published in 1778.]

The English version A Code of Gentoo Laws or Ordinations of the Pundits was published in 1776 to serve as a source for ’legal accomplishment of a new system of government in Bengal, where, it was said : ‘the British laws might , in some degree, be softened and tempered by a moderate attention to the peculiar and national prejudices of the Hindoo ; some of whose Institutes, however fanciful and injudicious, may perhaps be preferable to any which could be substituted in their room’.

In the introduction to the Code of the Gentoo Laws, (pages xxi-xxii) it was explained that the terms ‘Hindustan’ and ‘Hindoo’ are not the terms by which the inhabitants originally called themselves or their religion. In fact, in very distant past when their books were created, the religious distinctions as we know did not yet exist. And, their land was originally called as Bharatha-khanda or Jamboodweepa, in Sanskrit. Hindustan is a Persian word unknown to the original inhabitants of the land. It was only since the era of Tartars (Muslims) the name Hindoos came into use to distinguish them from the Mussalman conquerors. Thus, the term ‘Hindoo’ was employed mainly to demarcate some class of natives from some other class of natives. The translators, therefore, decided to reject the term Hindoo; but to retain Gentoos which term was then in common use among the Europeans.

It was only later when the British realized that the Indian Gentoos had numerous religious groups and sub-groups among them, the term ‘Hindoo’ came to be used in place of the Gentoo. Accordingly, in the British official records, ‘the religion of the Hindoos’ gradually displaced ‘the religion of the Gentoos’. The word Gentoo later became archaic and obsolete,

Until then, what is now called as Hinduism was officially referred to by the Europeans as the religion of the Gentoos. In the early years after that change, which is till end of early nineteenth century, the word ‘Hinduism’ was in common currency; and, it largely meant ‘the primal and ancient religion of the subcontinent’. But in the later years, the scope of the term Hindu as a religion was restricted to cover non-Muslims and non-Christians.

It was only later that ‘Hinduism’ came to acquire specific religious connotations and characteristics; and, having an assortment of beliefs.

**

Administration of Temples and religious institutions

The intervention and supervision by the British over the implementation of the Hindu Personal Law led to their gaining direct and indirect control over administration of religious institutions, deciding on religious matters ; as also to officially categorize issues and classify them as ‘religious’ or secular.

[With the advent of the British and their judicial system, an increasing number of litigations were brought before the Courts on all sorts of secular and religious matters, including petty ones. The better known among the religious issue, though a petty one, was Vadakalai Vs Thenkalai namam dispute of 1776 concerning the shape of the namam to be placed on the elephant at the Kanchipuram temple; and, the appeal filed thereafter in 1795. Baron Robert Hobart, 4th Earl of Buckinghamshire, who was then the Governor of Madras (1794- 1798), advised the warring Sivaishnavas:

“The Board of Directors of the Company do not think it is advisable to interfere in the religious disputes of the natives, lest by giving a decision on grounds of which they are not certain, it might become the cause of dissentions serious in their consequences to the peace of the inhabitants”.

Despite Governor Hobart’s sensible advice, disputes on the namam issues continued to be brought before the Courts. (Source: Madras, Chennai: A 400-year Record of the First City of Modern India, Volume 1; edited by S. Muthiah; pages 100 – 101)]

As the British began defeating the local Kings and gaining control over their territories, they naturally stepped into the shoes of the erstwhile rulers; and inherited the special privileges they were entitled to.

In the olden days, the King as the ruler of the state exercised authority and also assumed responsibility of protecting temples. He was accorded special regard and honors at the temples. The East India Company, as the rulers, too had to maintain such relations with the temples. In the process, the British gained control over the management and administration of the temples.

But some modifications in the relations between the ruler and the temple became inevitable under the Company rule.

In that context, the Madras Endowments and Escheats* Act of 1817 (particularly Regulation VII) came into force. Under this Regulation, the Madras government enabled itself to administer all the religious institutions in the Presidency. Apart from overseeing the temple administration, maintenance of its buildings and management of its finances, the British also had a say in ritual and worship activities.

[*Escheats – Where a person dies intestate , without leaving a will, and without leaving legal heirs, all his property shall be escheat ; and, shall belong to the Government.]

The involvement of the East India Company in temple activities was viewed by the British public opinion, back at Home, as supporting native heathen religion. The Anti-Idolatry Connection League (AICL) protested against such anti-Christian activities. East Indian Company came under heavy criticism for adopting and supporting a non-Christian creed.

The connections between of the Company with religious institutions in India also became a matter of dispute between politicians and the high officials of the Company in England on the one side; and administrators of the East India Company in India on the other side. Whereas the latter justified the support of the religious institutions like the temples with pragmatic political arguments…the former strongly opposed these links with moral and Christian missionary arguments and condemned it as state sanction of idolatry.

On August 8, 1838, the Court of Directors transmitted the following instruction:

We more particularly desire that the management of all temples and other places of religious resort, together with the revenues derived therefrom, be resigned into the hands of the natives; and that the interference of the public authorities in the religious ceremonies of the people be regulated by the instructions conveyed in the 62nd paragraph of our dispatch of 20th February, 1833.

The Board of Control, Sir John Hobhouse had to give an undertaking to the House of Commons, in early August 1838, that the Government would take urgent action.

The new policy statement also included a declaration of “withdrawal” from the management of Hindu religious institutions:

In all matters relating to their temples, their worship, their festivals, their religious practices, their ceremonial observances, our native subjects [shall] be left entirely to themselves.

Thereafter, in 1843`, the Madras Government of the East India Company finally bowed to the pressure from the British at home ; and ended its participation in the ritual activities of the temples , while retaining its control of the religious endowments. And, again in 1863, the power over endowments was also given up.

[The case on the point was that of the celebrated temple atop the Tirumala Hills.

Prof. S. K. Ramachandra Rao in his very well researched work The Hill Shrine Of Tirupati (Surama Prakashana – 2011) while chronicling the history and traditions of the Tirupathi-Tirumala Temple , spread over long centuries, makes a mention of the involvement of the East India Company in its management and administration.

The East India Company was in direct control of the Tirumala temple , its management, administration and its finances for about forty long years, from 1801 to 1841.

After the defeat of Tippu Sultan (1799) almost the entire South India came under British control. As regards the Arcot region which fell within the Madras presidency, the British gained control over the territory in a rather contrived manner.

After the death Chand Sahib, the then Nawab of Arcot, the British installed Md. Ali Khan Wallajah (1717 –1795) as the next Nawab of Arcot, during 1760. But, they demanded a price: Wallajah and his successors should serve the British as vassals; and that British would be paid certain amount of money for their efforts- ( for services earned with blood and presence, and that at the risk of losing our trade on the Coromandel coast).

Later, again, in 1780, the Nawab had to seek help from the British in defending his territory from attacks carried out by Hyder Ali of Mysore. The British East India Company agreed to provide the Nawab, for his safety, ten battalions of its Army stationed at Madras. For its services and also as the Royalty, the Company demanded, as its price, 400,000 pagodas (about £160,000) per annum.

Since Nawab Wallajah was unable to come up with the money demanded, he ran into enormous debts to the British. The Nawab had to borrow very heavily from the East India Company as also from financiers in England

Thereafter, an arrangement was devised through which the British would be able to recover their dues. Under that arrangement, Nawabs of Arcot assigned to the East India Company the revenues of the temples in their territory, including that of the temple at Tirupathi, to enable the Company to recoup the expenditure it incurred in safeguarding the territory of the Nawabs of Arcot, and also to recover the amounts that were promised to them, earlier, by Md. Ali Khan Wallajah for installing him as the Nawab.

The first Collector of Chengalpattu, Lionel Place, noted in his Report of 1799 that, soon after he became the Collector, he took over the ‘management of the funds of all the celebrated pagodas’ into his own hands and allotted the expanses of the temples for their festivals and maintenance.

And, by 1801, the British East India Company deposed the Nawabs of Arcot and annexed their territory. Thus, in 1801, the East India Company stepped into the shoes of the Nawab of Arcot as the De Jure ruler of the territory; and took direct control of the Tirupathi-Tirumala temple for the sake of garnering income of the temple. The object of the Company in taking over Tirupati temples was to generate fixed revenue, by organising its working, through systematic administration, and by preventing misappropriation and pilferage of temple funds.

In 1803, the then Collector of the Chittoor Mr. Sutton, sent a report to the Board of Revenues of the Company detailing the full account of the Temple, together with the schedules, pujas, expenses, and extent of lands held by the temple etc., This report came to be known as Statton’s Report on the Tirupati Pagoda; and, formed the basis on which the Company controlled the temple till 1821.

(According to the Report , the temple owned 187 villages of which 40 belonged to the various temple functionaries and 124 were under the management of palayakkarars )

***

In the meantime:

The East India Company , soon after its conquest of the Mysore region had appointed two experienced and well reputed Surveyors: Francis Buchanan for the Mysore region; and, Colin Mackenzie for the Southern India. They worked together briefly during the survey of Mysore in the early 1800s. Both men were recognized and highly well regarded for their professional approach, prolific and authentic output.

Colin Mackenzie, who arrived in India in 1783, began his career in the Madras Engineers; and by 1816, he was appointed India’s First Surveyor General. As soon as he took charge of the Southern India, he began collecting , collating data from major survey investigations and also the related drawings.

The earliest Mackenzie drawings were by himself. and, a majority of the other drawings created during his four-decade career were by trained military surveyors, who were mostly European. However, Mackenzie also collected paintings by Indian artists.

Mackenzie’s survey work also extended into areas that were not under East India Company control, but were considered potentially valuable to the Company. One such area was Tirupati. Company’s interest was prompted by a report compiled , during 1803, by the British Collector Mr. Sutton at Chittoor, on the Sri Ventakeshvara Temple, a heavily endowed pilgrimage site , with a considerable amount of revenue.

Since Tirupati was a Brahmin controlled area, Mackenzie thought it prudent not to visit the area or to send a survey team. He, therefore, asked one of his Brahmin assistants, Subha Rao, to visit the Sri Venkatesvara Temple in 1804; and, to produce a report, along with accounts of the hills, roads and buildings at the site etc.

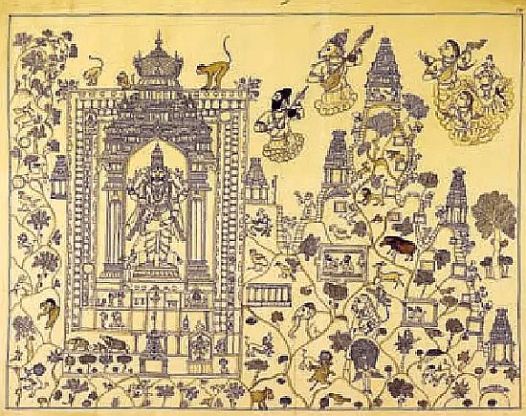

Perhaps to supplement this account, Mackenzie collected a drawing of the Sri Venkatesvara Temple, and the surrounding area, as made by a local Tamil or Telugu artist.

The picture that was produced , in 1804, is in a typical South Indian, Company School style, showing the artist’s use of multiple point perspective, so that all the important factors of the temple and its surrounding landscape, as they would be viewed by a pilgrim visiting the site, were taken into account, including the steep stairs that the pilgrims traveled along, and the forests surrounding the site, teeming with wild animals.

This picture, it is said, might have been the closest Mackenzie could get to survey the site. Mackenzie presented the Tirupati drawings, in around 1815, to his colleague, Sir Thomas Strange, the Chief Justice at Madras from 1801 to 1817. It is now housed in the British Library , London.

[ I acknowledge with thanks , the source : Indian ‘Company School’ Art from 1780 to 1820: Collecting Versus Documenting’ by Jennifer Howes ]

***

Between 1805-16, many instances of misappropriation and misuse of temple-funds were brought to the notice of the Company. Thereafter, the British East India Company passed the Regulation VII of 1817 to check such abuses. That paved way for the Company to interfere in almost every aspect of the Temple administration.

And again during 1821, Col. Bruce the then Commissioner of the Chittoor District came up with a code of rules for guidance and conduct in the management and administration of the Tirumala Temple. His code which came to known as ‘Bruce Code’ , was said to be in use till the Tirumala-Tirupati Devasthanams Act of 1932 came into force.

The Bruce’s Code of 1821, formed in terms of regulation seven of the Madras Regulation Act 1817, was essentially a set of rules for the management and administration of temples at Tirupathi and Tirumala. These were well-defined rules formulated as a code having Forty-two provisions to guide the administration of temples of Tirumala and Tirupati on the basis of customs and previous usages , (including payment of salaries to staff ) without , however, interfering in its day-to-day affairs. It also prescribed a Questioner (Saval-Javab- Patti) and time-table and regimen for conduct worship and other services for each day of the year.

Under the recommendations of the Bruce Code, a District level official working under the Revenue Board of the Company was appointed to look after the income, expenditure, administration and management of the temple on behalf of the Company. He was assisted by a Tahsildar, Siristedar and four clerks. It is said; the annual income from the Tirumala temple which in 1749 was Rs.2.50 lakhs was increased to more than Rs.3.50 lakhs in 1822; and the the expenses in 1822 amounted to about Rs.0.30 lakhs.

The protocol for the entry of the pilgrims as also for collection of offerings and accounting was also laid down :

Passing through the Bagalu vakili or silver porch the pilgrims are admitted into a rather confined part and are introduced to the God in front of whom are two vessels, one called the Gangalam or vase, the other Kopra or large cup and into these things the votaries drop their respective offerings and making their obeisance pass through another door. At the close of the day, the guards, both peons and sepoys round these vessels are searched. Without examination of any sort offerings are thrown into bags and are sealed…after which the bag is sent down to the cutcherry below the hill Govindarauz pettai. At the end of the month, these bags are transmitted to our cutcherry… and there they are opened, sorted, valued and finally sold at auction. However during the Brahmotsavam either the collector or a subordinate must be on the spot due to the value of the offerings…

The East India Company was in direct charge of the Tirumala Temple until 1841, when its Court of Directors in England strongly resented “the participation of the Company’s officers and men in the idolatry conducted in Hindu temples by reason of its management of these religious institutions and ordered its relinquishment of their administration of religious endowments”.

Thereafter, in 1843, the East India Company decided to move away from direct involvement in temple administration; but, to ‘outsource’ the Temple –administration by introducing the system of appointing a Mahant. Under that system, the Mahant would administer the Temple on behalf of the Company; and would remit to the Company a certain specified amount, regularly each year.

The first of such Agent appointed in 1843 was a Mutt named Hathiramjee Mutt, belonging to the Vaishnava Ghosai tradition of North India. The first Mahant so appointed by Hathiramjee Mutt was Seva Das (1839-1860). He was succeeded by Mahant Dharma Das (1860-1870). During their tenure, many temples atop the Hill affiliated to the main temple of Tirumala were renovated; and the restoration and improvement of the temple-tank was also undertaken (1846).

The Mahant system was in existence until the Tirumala-Tirupati Devasthanams Act of 1932 was enacted. That Act was replaced by the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act of 1951.]

But, withdrawal of the Company from the direct involvement in the administration of the temples did not seem to matter much, because by 1863 all the ‘Hindu’ religious institutions had been brought under the control of the East India Company. And the Government had to continue to be involved in litigations concerning the temple properties, which by- the-way, produced body of case laws based. And, the Government had to bring into force additional legislative provisions to govern the temples more effectively.

Such legislative measures were intended to take care of varieties of issues and problems not only in the day-to-day administration but also on matters impinging upon the control and ownership of the temples. For instance; the rules specified the conditions under which the Government could take control over the temple; the extent of such control; measures to combat pressure-groups that posed threats to the temple; as also the tactics of the vested interests to influence the direction of the Government policy etc.

It was during the course of such measures and steps taken by the British in the administration of ‘Hindu religious institutions’, the concept and identity of ‘Hinduism’ as a legal entity and a public cause took concrete shape. Thus, ‘Hinduism’ which till then was rather amorphous, began to gain a structure as litigation after litigation were brought before the courts. The events that followed advanced the process.

***

The Census of 1871

But, it was the Census of the 1871 that formally, officially and legally categorized Hinduism as a religion.

The 1871 census, the first comprehensive census to be conducted on All-India basis, set out to gather data on religion in order to analyze and interpret data categorized under various heads. Apart from supplying factual information to the government, the Census helped in objectifying the concepts used to compile the data collected. As a result, these concepts – one of which was the religion – acquired a new reality and relevance beyond the census figures and bureaucratic reports.

Not only did the Census reports accord increasing importance to ‘religion’ both as a subject in its own right and in relation to other subjects, but also as a conceptualization of ‘religion’ in terms of community, membership of which could be established by reference to certain criteria , and conduct ; and , hence compared with membership of such other communities .

The inclusion of religion and the role assigned to it posed a problem to the enumerators and analysts when it came to identifying ‘Hindus’ and hence ‘Hinduism’. In order to avoid complicated tabulations, the enumerators adopted a short method or a thumb rule. They went by the rule that anyone who was unable to identify himself with a known sect was to be classified as a ‘Hindu’. This was also the method adopted for tabulating most of the tribal people, nomads and low caste

And that brought focus on the contentious question of determining who was a ‘Hindu. It also went into exercise of classifying religious movements as “Hindu’ or; non-Hindu’.

While enumerating ‘Hindus’ , the Census made judgements about the limits of ‘Hinduism’ that in turn became focus of controversy , thereby establishing how official use of certain categories to classify ‘religion’ promoted the reification of ‘Hinduism’, which is rendering the complex idea of Hinduism into something recognizable and easier to identify.

Thus, the British imperialism played a key role in the concretisation of ‘Hinduism’ as an identifiable religion. This led to transformation of an abstract idea into a practical ‘religion’ distinct from other religions.

**

Divide and Rule

At times, the cultural and linguistic differences among the local populations were exploited by the British to accentuate the ‘Hindu’ divide.

For instance; the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh was a large and heterogeneous territorial unit of British India. The rural areas, in general, were dominated by Hindu folk traditions. The fairly large Muslim minority of the United Provinces (about 17 per cent of the population) was mostly settled in the towns (about 44 per cent of the urban population).

The differences between the two were reflected in their language and literature: Urdu, the lingua franca of the Mughal empire, was associated with urban Muslim culture; while, Hindi and its many dialects was the idiom of the rural Hindus.

Movements such as that for the recognition of Hindi in Devanagari script (i.e. the Sanskrit alphabet) as an official language in the Urdu-dominated courts of law (where proceedings were recorded in Persian characters), as well as campaigns for the protection of the sacred cow from the Muslim butcher, merged into a general stream of Hindu nationalism in the late nineteenth century.

The British decision to replace the use of Persian in 1842 for government employment and as the language of Courts of Law caused deep anxiety among Muslims of the sub-continent. This development greatly alarmed the Muslims and gave rise to communal conflicts.

The British had certainly not created these conflicts, but they took advantage of them in line with the old maxim ‘divide and rule’. The British seemed to favour the minority Muslims who looked to them for the protection of its interests against the Hindu majority.

The British established a Muslim college at Aligarh, near Agra, which was designed to impart Western education to Muslims while at the same time emphasising their Islamic identity. This college, later called Aligarh Muslim University, became an ideological centre whose influence radiated far beyond the province in which it was established.

Challenged by the foundation of a Muslim university, the Hindus soon made a move to start a Hindu university which was eventually established at Benares (Varanasi) and became a major center of Western education.

The establishment of two sectarian universities in the United Provinces was characteristic of the political and cultural situation in that part of India, also clearly demarcated the ‘Hindu’ from the rest.

[There is an interesting side-light , which is often cited. Some claim it is true; and, others deny it.

Pundit Madan Mohan Malaviya, in his efforts to set up the Benares Hindu University at Varanasi, went around many parts of the country, collecting funds to finance its building-constructions.

During the year 1911, as a part of his roundabout roving around the country, a sort of tour de France or a big loop, Malaviya called upon the Nizam of Hyderabad (then reputedly the richest man in the world), soliciting funds for setting up a Hindu University. To say the least, the Nizam was not amused; and, is said to have hurled one of his shoes at the visitor.

Malaviya, it is said, picked up the shoe; and went directly to the market place for auctioning it. As it was Nizam’s footwear, many, naturally, came forward to buy it. The bids kept going up.

When Nizam learnt of this unseemly incident at the market place, causing needless disturbance and much amusement among the crowds, he was annoyed; and, asked his officials to put an end to what he deemed as a charade or mockery. One of his attendants was instructed to ‘Buy back that footwear, no matter whatever its price be!’

Needless to say, the shoe fetched considerable amount, given the context of its times. . The money, it is said, was used to build a teacher’s colony in BHU called Hyderabad colony.

In any case, it could be said that Malaviya either convinced or persuaded the Nizam to support his cause.]

***

Role of the Missionaries

If the British imperialism played a leading role in the construction of ‘Hinduism’, the role of the Christian Missionaries was no less important.

Because of the effort of the group of Evangelicals led by William Wilberforce, the British Parliament resolved that Christianisation of India was the solemn duty of the British Government. This led to the unrestricted ‘opening’ up of India to missionaries with full freedom to condemn and malign Hindu religious practices and institutions. It also led to the setting up of the Ecclesiastic Department as a part of the Government of India.

The Christian Missionaries, thereafter , enjoyed a special and a privileged relationship with the British Government. Britain was seen the ‘Mother Country’ of Empire whose official religion was Christianity. The British rulers in India viewed themselves as the servants and protectors of the Mother country as also of its religion. The Missionaries could preach and propagate Christianity under the protective canopy of the British Raj.

The Missionary activity earnestly picked up strength since 1813 under the aegis of the East India Company. Even later under the protective canopy of the British Raj, the Missionaries could preach and propagate Christianity as the ‘true religion’; and denounce Hinduism as a ‘compound of error, c corruption and exaggeration’ and as a false religion.

With such propaganda, a clear line was drawn between Hindu and non-Hindu religions.

Oriental Scholars of the West

The oriental scholars were also influenced by the British government and by the Church.

There were the Oriental scholars, funded by wealthy private patrons, who carried forward the Missionary agenda. Lt. Col. Boden of the Bombay Native Infantry endowed a Chair in the Oxford University for propagating Christianity in India through Sanskrit.

In 1832, Horace Hayman Wilson became the first to be appointed to the newly founded Boden chair of Sanskrit. His view was that Christianity should replace the Vedic culture. And, he believed that full knowledge of Indian traditions would help effect that conversion. Aware that the Indians would be reluctant to give up their culture and religion, Wilson made the following remark:

A learned Brahman trusts solely to his learning; he never ventures upon independent thought; he appeals to memory; he quotes texts without measure and in unquestioning trust. It will be difficult to persuade him that the Vedas are human and very ordinary writings, that the Puranas are modern and unauthentic, or even that the Tantras are not entitled to respect. As long as he opposes authority to reason, and stifles the workings of conviction by the dicta of a reputed sage, little impression can be made upon his understanding. Certain it is, therefore, that he will have recourse to his authorities, and it is therefore important to show that his authorities are worthless.”

With the death of Horace Hayman Wilson in 1860, the Boden Chair fell vacant. Monier Williams was the hot contender to the Chair; competing against Max Muller, who was known for his philosophical speculations based on his reading of Vedic literature. Monier Williams, in contrast, was seen as a less brilliant scholar; but , he had the advantage of being familiar with the religious practices in modern Hinduism.

As a part of his submission to the members of Convocation of the University of Oxford, 1860, Monier Williams had assured:

Having commenced my career as a Scholar on the foundation of Colonel Boden, I owe a deep debt of gratitude to the munificent benefactor, who provided for the perpetual study of Sanskrit in the University of Oxford; and, if I am elected to the Boden Professorship, my utmost energies shall be devoted to the one object which its Founder had in view; namely “The promotion of a more general and critical knowledge of the Sanskrit language, as a means of enabling Englishmen to proceed in the conversion of the natives of India to the Christian religion”.

Sir Monier Williams did succeed in becoming the second-Boden Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University, England. He studied, documented and taught Asian languages, especially Sanskrit, Persian and Hindustani.

He made it clear that his interest in preparing dictionaries was primarily to translate the Bible into other languages. He said that he would initially fulfill the wish of Col. Boden to translate the Bible into Sanskrit ‘in order to enable his countrymen to proceed in the conversion of the natives of India to the Christian religion’. Monier Williams, eventually, compiled a Sanskrit-English dictionary based on the earlier Peters-burg Sanskrit Dictionary which was published in 1872. A later revised edition was published in 1899 with collaboration by Ernst Leumann and Carl Cappel.

In his writings on Hinduism, Monier Williams argued that Hinduism is a complex ‘huge polygon or irregular multilateral figure’ that was unified by Sanskrit literature. He stated that ‘no description of Hinduism can be exhaustive which does not touch on almost every religious and philosophical idea that the world has ever known’.

Monier Williams taught Asian languages, at the East India Company College from 1844 until 1858, when the rule of the East India Company in India ended, after the 1857 rebellion. He came to national prominence during the 1860 election campaign for the Boden Chair of Sanskrit at Oxford University, in which he stood against Max Müller.

After his appointment to the professorship, Williams had declared, from the outset, that the conversion of India to the Christian religion should be one of the aims of all types of orientalist scholarship.

*

Max Müller (1823 –1900) considered that Hinduism which was characterized by superstition and idolatry needed to be reformed just in the manner of Christian Reformation. In his letters to the Dean of St. Paul’s (Dr. Milman) of February 26, 1867, Max Muller wrote: I have myself the strongest belief in the growth of Christianity in India. There is no country so ripe for Christianity as India, and yet the difficulties seem enormous.

In a letter to his wife, Max Muller wrote: “It (The Rig-Veda) is the root of their religion and to show them what the root is, I feel sure, is the only way of uprooting all that has sprung from it during the last three thousand years.”

In one of the letters, he says, “Ah! We have found the key to Christianize India.” And the key, according to him, was the Brahmo Samaj, in which the missionaries reposed great hope as the intermediate station for the Hindus of Bengal to become Christians. They had their hopes, in particular, on Keshav Chandra Sen, who was heading the Brahmo Samaj then.

Later he also wrote to the Duke of Argyle, the then acting Secretary of State for India: “The ancient religion of India is doomed. And if Christianity does not take its place, whose fault will it be?”

In his 60s through 70s, Max Müller gave a series of lectures, which depicted his view of Hinduism. That somehow was followed by others of his time.

*

Many have argued: “The term ‘ism’ refers to an ideology that is to be propagated and by any method imposed on others for e.g. Marxism, socialism, communism, imperialism and capitalism but the Hindus have no such ‘ism’. Hindus follow the continuum process of evolution; for the Hindus do not have any unidirectional ideology, therefore, in Hindu Dharma there is no place for any ‘ism’.

They point out that ‘Hinduism’ that the western world perceived was essentially the construction of the British imperialism, the nineteenth century western scholars and the Missionaries. Such constructions were made to suit their own agenda.

***

‘Hindus’ and ‘Hinduism’

As we saw, the concept of Hindu and Hinduism that emerged during the Nineteenth century was mainly in terms of the notions imposed by imperialism, missionary impulse and western scholarship.

Many educated Indians of the nineteenth century, therefore, mounted a counter attack on the Christian Missionary propaganda against Hinduism, adopting their own (missionary) methods and style.

There were also those who sought to remedy the flaws through which others tried to expose and exploit Hinduism, by revaluing the ancient texts, by reforming the Hindu practices and such other radical explanations.

In addition, there were the Indian elite who somehow seemed to be apologetic about Hindu beliefs and practices; and brought in social and cultural reforms. A Bengali Renaissance tried to usher in a new type of philosophical Hinduism tinged with a romantic nostalgia for some of the nobler forms of Vedic traditions.

At the same time, many cast doubts upon the conclusions of the oriental scholars, pointing out the flaws in their sectarian stance and arguments and dogmatic approach .

There was another set of Indians trying to make use of the religious enactments passed by the Government and take control of the religious institutions; while at the same time protesting against threats and encroachment on Hindu interests.

The construction of Hinduism thus arose out of encounter and interaction with the West. And it owed much to the Indian elite.

Such assortment of ’ Hinduism’, thus, was mostly the creation of the nineteenth century Indians as a response to or in confrontation with the Western interpretations. Their reaction also to an extent contributed to the shaping of Western perception of ‘Hinduism’.

Some of the influences that shaped and re-shaped the concept of ‘Hinduism’, during the nineteenth century, were obviously religious; and, in addition there were also social, cultural and political organizations that projected their concept of ‘Hinduism’.

Raja Ram Mohun Roy and Brahmo Samaj looked down upon the current practices as corrupt and degenerate. The Brahmo Samaj harked back to the ancient and pure ways of the Upanishads, formulating an enlightened creed of ‘Hinduism’.

Swami Dayananda Saraswathi also aspired to bring back the principles and practices of the Vedic times. He called upon all Indians to study Vedas.

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, a mystic seer, through his own experiences declared the oneness of all religious paths ‘and took a ‘universal’ view of all religions and varied paths leading to same goal.

Jatiya Mela and Jatiya Sabha of Bengal came together, (renamed as Hindu Mela, in 1867), in order to promote a distinct identity of the ‘Hindu’ and a sense of pride in being a ’Hindu’

There were also movements of emerging popular ‘Hinduism’ floating their own pet brand of ‘Hinduism’.

*

In the political terms, the concepts of ‘Hindu’ and ‘Hinduism’ got entwined with nationalistic ambitions of several organizations.

Some of those nationalists portrayed the land Hindustan as the holy Motherland of the people of India. For instance; Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (Chatterjee) (1838-1894) raised Nationalism to the level of religion by identifying the Motherland with the Mother-Goddess. The tremendous impact and thrilling upsurge that Anandamath and Vandemataram had on the Indian National Movement is indeed legendary. He came to believe that there was “No serious hope of progress in India except in Hinduism-reformed, regenerated and purified”. With that in view, Bankim Chandra tried to reinterpret ancient Indian religious ideals by cleansing them of the accumulated floss of myths and legends.

Aurobindo Ghosh and other revolutionaries acknowledged Bankim Chandra as their political Guru and followed his ideals of India and ‘Hinduism’.

The Hindu Mahasabha founded in 1909 by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was based in the idea of Hindutva. It called upon Hindus to fight for the freedom of Motherland and to consolidate the Hindu nation.

That movement fell into decline rather soon. And, its place was taken by Rastriya Svayamsevak Sangh (RSS) inspired by the ideals of the Anushilan Samiti , was established by Dr. Hedgewar (1889 –1940) in 1925 with the ideal to ‘unite and rejuvenate our nation on the sound foundation of Dharma’.

Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) the political offshoot of RSS carried a similar ideal.

The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) a cultural organization with undertone of Hindu religion vowed to protect Hindu religion from encroachment by other religions.

These movements also contributed towards identification and demarcation of ‘Hinduism’ where “Hinduism’ was broadly associated with nationhood.

**

Hinduism variously conceived

Variously conceived, ‘Hinduism’ was generally regarded as the ‘essential religion of India’. And yet; the views on the quintessence of Hinduism varied greatly. The question got complicated by the presence and practices of immense varieties of beliefs and plurality of perspectives. But, yet there have also been efforts to equate ‘Hinduism’ with a particular version of it. There are also those who wish to treat Hinduism as a group of ‘religions’ or a socio-cultural unit or civilization which consist a plurality of distinct religions

There are also different versions of ‘Hinduism’. Sri Sankara’s non-dualistic Advaita philosophy takes a broad view and reconciles the apparently conflicting beliefs within the ‘Hinduism’ as a system. Then there is the Vaishnava theology centred on devotion on a personified God. There are also affiliate home-grown religions such as Jainism, Buddhism and Sikh-religion. There is also the juxtaposition of foreign faiths such as Zoroastrianism, Christianity and Islam.

*

The acceptance of the Vedas and their authority has been cited by the Supreme Court as one of the characteristics of Hinduism.

It is no doubt that Vedas are the roots of Indian ethos, thought and philosophy. They are of high authority, greatly revered and very often invoked. But, their roots are lost in the distant antiquity. The language or the clear intent of those texts is not easily understood; its gods and its rites are almost relics of the past. They no longer form active part of our day-to-day living experiences. The worship practices followed by the common Indians of the present day differ vastly from the rites prescribed in the Vedic texts. The gods worshipped by the present generations too vary greatly from the Vedic gods . In today’s world, it is the popular gods, modes of worship as in the duality of Tantra that has greater impact on socio religious cultural practices than the Vedas. The living religion of ‘Hindus’, as practiced today, is almost entirely in the nature or the version of what appeals to each sect, or to each individual .

[Most of the Western Scholars consistently draw a distinction between the Vedic tradition and the ‘Hinduism’.]

*

There is also a claim to adhere to Sanatana Dharma (eternal law), an equivalent of perennial philosophy of the West, where all ‘religions’ are unified. This is despite the fact that the meaning and scope of the term Dharma is far wider than ‘religion’; and is not restricted to religion or sect.

[ The term Sanatana is , often , explained thus : ‘Puratana‘ is that which belongs to the past; ‘Nutana‘ is that which has come into existence now ; and “Sanatana‘ is that which has been in the past, existing in present, and continuing in the future. It is present at all times. It is eternal.]

But, the term Sanatana Dharma is perhaps used to signify orthodoxy as opposed to reformed ‘Hinduism’. That is based in the belief that ‘Sanatana Dharma’ though of great antiquity is indeed an ongoing process that changes while retaining continuity. Yet, it is rooted the aspiration of attaining liberation (Mukti) from all sorts of confines and limitation. It is all-inclusive in nature and not shutting out new ideas and concepts; it is also not regimented by fixed set of rules or commandments.

The proponents of Sanatana Dharma concept assert that ’Hinduism’ is a recent construct, which was introduced into the English language in the 19th century to denote the religious, philosophical, and cultural traditions native to India. Despite that rather newly coined epithet, they point out, it essentially refers to a rich cumulative tradition of texts and practices that date back to a very distant past. And, they quote The Supreme Court which said that Hindu does not signify a religion but a way of life; and represents the culture of India, and of all people of India, whether Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, etc.

.

***

At the End

Thus, though the word Hindu (not originally Indian) might have, in the past, referred to a geographical region (Hindu-stan), a cultural association, or language (Hindu-stani) or to a common religion of the land etc, yet, it has, over a period, come to acquire specific religious connotations and characteristics. Consequently, the concept of the ‘Hindu religion’, that is ‘an Indian religion with a coherent system of beliefs and practices that could be compared with other religious systems’ got established.

Now, generally, one is understood to be a Hindu by being born into a Hindu family and practicing the faith, or by declaring oneself a Hindu. It has been used as a geographical, cultural, or religious identifier for people indigenous to South Asia. In any case, Hinduism is now a nomenclature for the religious tradition of India and the suffix ism is hardly noticed. Not many have qualms in accepting ‘Hinduism’ or being a ‘Hindu’.

***

A Hindu is a Hindu not because he wanted to be distinct and created a room and put a door around him. But, because others started constructing walls everywhere, and at some point of time, the Hindu found that the walls other constructed somehow became his boundaries as well.

– Julia Roberts

Sources and References

- Interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gita and images of the Hindu tradition by Catherine A. Robinson

- A History of India by Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund ; Fourth Edition; Routledge ; 2004

- The Hill Shrine Of Tirupati by Prof. S. K. Ramachandra Rao (Surama Prakashana – 2011)

- https://selfstudyhistory.com/2015/09/30/al-birunis-india/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruce%27s_Code

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Census_of_India_prior_to_independence

- https://tamilbrahmins.wordpress.com/2015/09/13/temples-and-the-state-in-india-a-historical-overview/