I recently read some posts which presented in ingenious ways their take on irrational and rational faiths and beliefs. The term rational–faith seemed rather confronting, with the two contradictions placed face to face, as if one was challenging the other. In that context, the fate and its inevitable part in human life were also mulled over. And, I found the posts interesting. I reckon there is a bit more to fate and its related issue: the human endeavor; hence this post.

What is fate?

1.1. It is common experience that most of the things that happen in one’s life result from one’s efforts or in the process of trying to do something. One is naturally gratified to see ones endeavors crowned with success, either immediately or after a passage of time. And, the persons who succeed,deservedly, congratulate themselves over their efforts.

However, there are also occasions, though seldom, when things seem to just happen, almost on their own accord. And at times , things seem to happen despite oneself. Such a rare happening could either be a delightful surprise or be a cause for agonizing distress.

1.2. When a person is happy; when life is easy and pleasant; when things are flowing like milk and honey; or, when one is overwhelmed in joy from a windfall, then it is the good-fortune or Luck that smiles on him/her. When you or your dear one is suddenly cured of an ailment, it is then a miracle. When you just escaped an accident that could have grievously injured you or could even have killed you, it is then providence or divine intervention. You thank god profusely for his mercy. You also come to accept providence as the divine will, the super-natural entity or will that governs all events in the universe.

1.3. There also comes a time when ones effort does not bring forth fruits as expected; or, the things that started well begin to show signs of going weary. And it is worse when your project slides into an abject wreck, for no fault of yours. Nothing seems to reasonably explain your failures. The disappointments, sufferings and sorrow that follow are then blamed on fate.

2.1. Thus, a windfall or bright fortune is good luck. But, Fate has come to be understood as one that is inseparably linked to prolonged or acute suffering, undeserved punishment , reverses in life, unexpected losses , humiliation, poverty, disease , loss , death of near and dear ones etc. It is especially agonizing when the suffering is undeserved and unjust.

What should one conclude when such acute loss or sorrow is brought about by no apparent fault of hers/ his; and, when failures are not rationally linked to any agent or any action? It is his Fate, he laments.

2.2. Fate serves as a gap-filler to fill the vacuum in his understanding of the world around him when other visible or rational explanations fail. The concept is reinforced further, in a negative way, at the sight of an evil person enjoying happiness and good things in life, while a righteous one suffers eking out a miserable existence. Since neither the comfort nor the misery – undeserved in either case – can be explained in a rational way, they are routinely blamed on the inevitable play of the fate.

3.1. Having said that, what one calls Fate is not an objective reality. It cannot be perceived by human senses. Some call it a creation of human imagination ; or, at best, is a default-inference. One could even say that man invented fate by re-ordering his moral world , so that he could ascribe to it whatever that did not fit into its paradigm. It may also have been born of man’s refusal to accept the idea that life is wholly irrational; and, out of his pet-belief that there is an unknown area beyond all that is known, which would explain life and its mystique.

In a way of speaking, it might not be wrong to call fate a projection of man’s fears and helplessness in the face of strange, untoward, unexpected, undeserved occurrences for which he is wholly not-responsible and is unprepared; and, for which he has no explanation. It is something towards which he feels is driven, going by his hard experiences in the world.

3. 2. Fate, by its very concept, is thus, irrational. One could lament that Fate is blind. It gives solace but not light; and, never guidance. Yet, one cannot entirely deny the unknown and the unpredictable elements of life. Man, therefore, calls fate : a capricious phantom. And yet, a brave person manfully challenges this caprice, unwilling to surrender to its whims, to deflect its moves through precaution, valor, and various other brave and crafty ways. That is the crux of life.

[Please do read :Why do the children have to suffer so horribly?]

Fate in Indian ethos

4.1. Surprisingly, the concept and the belief in fate is a late entry into the Indian ethos. None of the four Samhitas, the Aranyakas, the Brahmanas or the Upanishads speaks of fate. In Rig Veda, particularly, prayers are addressed to benevolent gods who are gently or fervently persuaded to grant fertility in crops and cattle, to bless with plenty of sons and wealth. There is a joyous optimism looking forward with hope to be truly alive over a ‘span-of hundred – sharad ritus’, the best of the seasons. These texts do not have trace of fatalism.

But, the concept of fate and fatalism gained prominence much later in the Epics and the Puranas. We shall talk a bit more of that in the paragraphs to follow.

4.2. The first philosopher to formally propound the theory of fatalism (Niyati-vada) was Makkhali Gosala, an early contemporary of the Buddha. Some say; he was called Gosala because he was born in a cow-shed. Panini the Grammarian (around 5th century BCE) described him as Maskarin (maskara-maskariṇau veṇu-parivrājakayoḥ – PS_6,1.154 – a mendicant who carries a bamboo staff).

Makkhali Gosala was a follower of Parsvanatha, the twenty-third Tirthankara, in the Nigantha Nataputta Order of Jainism. Gosala too was a naked ascetic. Due to differences with the main Jaina Sangha, Makkhali Gosala left the Order; and , founded his own sect: the Ajivika.

[ Dr. Benimadhab Barua (A History of pre-Buddhistic Indian Philosophy) says, Ajivikas cannot be entirely identified with naked recluse/ascetics. They were, in general, independent and self-respecting individuals who had following among the Jains as also Buddhists. The Ajivika thesis, in main, according to him, is that the universe is a purposive order where everything is assigned its place and function (niyati).The law of change is universal and all beings are capable of transformation; and most attain perfection in due time. The man’s life has to pass through eight stages of development at each of which physical growth proceeds along with the development of senses, moral and spiritual faculties. And, finally leading to purity of mind; purging it of all impurities that have stained it.

Thus Dr. Barua’s rendition varies from the popular versions of the Ajivika-beliefs.

Dr. Barua gives some biographic details of Gosala that are not mentioned by others: The Jain sources mention his name as Maskarin – one who carries a staff; also known as Ekadandin. Maskarin preceded Mahavira by sixteen years. His actual name was Gosala Mankhaliputta – son of Mankhali and Bhaddha; and was born at Saravana near Savastthi. His father Mankhali derived his name from the profession he followed – a dealer in pictures. Gosala followed his father’s profession until he turned a monk.]

4.3. Prof A L Basham writes (The Wonder that was India):

No scriptures of the Ajivikas have come down to us, and the little we know about them has to be reconstructed from the polemic literature of Buddhism and Jainism. The sect was certainly atheistic; and its main feature was strict determinism.

The usual doctrine of karma taught that though a man’s present condition was determined by his past actions he could influence his destiny, in this life and the future, by choosing the right course of conduct.

This the Ajivikas denied. They asserted that the whole universe was conditioned and determined to the smallest detail by an impersonal cosmic principle, Niyati, or destiny. It was impossible to influence the course of transmigration in any way.

“All that have breath, all that are born, all that have life, are without power, strength or virtue, but are developed by destiny, chance and nature, and experience joy and sorrow in the six classes £of existence There are … 8,400,000 great aeons (Maha-kappa), through which fool and wise alike must take their course and make an end of sorrow. There is no question of bringing unripe karma to fruition, nor of exhausting karma already ripened, by virtuous conduct, by vows, by penance, or by chastity. That cannot be done. Samsara is measured as with a bushel, with its joy and sorrow and its appointed end. It can neither be lessened nor increased, nor is there any excess or deficiency of it. Just as a ball of string will, when thrown, unwind to its full length, so fool and wise alike will take their course, and make an end of sorrow.”

*

4.4. Ajivika sect was perhaps the first to put forward fatalism as being absolute and final. It embraced the concept of fate rather too tightly ; and, affirmed fate as the ultimate reality in human life. It believed: ‘there is no such thing as human endeavor, human strength or determination; all things are pre-determined’.

His parent body, the Jainas , did not however quite approve of Gosala’s theory; and , promptly labelled it ‘ajnana-vada’, the doctrine of ignorance.

4.5. Gosala seems to say you are free to take the first step; but as soon as you take it, you are bound by the outcome of your act and have lost your freedom of choice.

For instance; let’s say you are about to plant a sapling. As long as you have not done it, almost all options are open to you. But, once you decide on your choice, its outcome is also determined. If you plant a mango tree, then you reap only mangos; and , no other fruit. In other words, you can act, but its outcome is predestined.

[This sounds very similar to Prof. Cassius .J. Keyser’s concept of Logical Fate which essentially means that from premises consequences follow. Choices differ . . . and when we have made it, we are at once bound by a destiny of consequences beyond our will to control or to modify (See his Mathematical Philosophy). ]

5.1. Makkhali Gosala had declared :

“There is neither cause nor basis for sins of human beings (ahetukavada). None of the deeds of man can affect his future births. All beings, all that have breath, all that are born, all that have life, are without power, strength, or virtue; but, are developed by destiny, chance and nature. All existence is unalterably fixed (niyata). Suffering and happiness, therefore, do not depend on any cause or effect; but, are pre-determined by niyati (fate). And, niyati being adrsta is unseen and preordained . Suffering and happiness, therefore, do not depend on any cause or effect ”.

5.2. The Buddha totally disliked the fatalistic theory ; called its promoter Gosala as the most dangerous of the heretic teachers; and, remarked :

“Just as the hair blanket is the meanest of all woven garments , even so, of all the teachings of nagga-samanas (naked recluse) that of Makkhali is the meanest” (Majjhima Nikaya :1:513).

5.3. The reason that the Buddha summarily dismissed the fatalism of Gosala was perhaps because, it rendered human life utterly irresponsible; robbing it of accountability for man’s evil or even good deeds. Gosala had said , man was not responsible for his deeds, as he was under the control of fate. Further, Gosala had discounted the role of Karman in life as also in life-after-life of all beings; but , had asked all men and women to put faith in fate. Gosala had thus attacked the very foundation of the Buddha’s fundamental theory of the chain of cause-and- effect, where the effect is produced by a cause through modifications. The Buddhist law of causation – Pratītyasamutpāda – was the basis of every other doctrine in Buddhism including rebirth, karma, samsara, dukkha etc.

[But , the later forms of Buddhism could not keep out the element of fate. For instance, a Jataka tale (No.257 Gamanichanda) makes out that chance predominates and takes over the course of human life as the agent of fate. And in another Jataka (No.538 Mugapakka) a king chased by ill-luck for long period says “I know not where I go, the fate watching never sleeps”.]

Karman and rebirth

6.1. But what is Karman? Simply put, it is action, any action, good, bad or indifferent which involves a moral decision. But, occasionally, unwitting action – good or bad – also counts for Karman. It is the belief that ‘as a man decides, he acts; and, as he acts , he reaps the fruits of action ‘.

6.2. It was much later that rebirth came to be associated with Karman: a man was born and lived according to what he did in his life on earth. This association had many facets.

Initially, the rebirth had reference only to the future. But, with Karman , it became a two-ended proposition: a man’s past Karman determines his present station; and, his present station determines how he will fare in the future. It also meant that Karman took time to mature and to yield its results. This time gap (karma-pari-paka) was compared to the interval between sowing and harvesting; or between administering medicine and regaining health.

6.3. Karman in association with rebirth was , largely , an assumption (just as many of these concepts) ; and , was not proved by any of the valid means of knowledge or the methods of cognition (Pramana). But, Karman seemed to offer an explanation to the illogical inequalities and relative-injustices that one comes across in the world. That made it easy to explain the fact that certain persons , though thoroughly undeserving, occupy higher positions in the social hierarchy, enjoy the power and all the benefits that come with their status because of their Karman in their past births.

7. 1. But, these elucidations seemed to have a limited range, as they did not adequately explain all events in human life. It was pointed out that similar actions do not always produce similar results. And, it did not explain the vast range of variations that occur even among the fortunate ones, who are better placed in life.

Further, it was argued, how could an individuals’ Karman explain a natural calamity like famine, epidemic, accidents, disasters etc involving mass-deaths. Does it mean that all those victims had identical Karman which matured at precisely the same instant?

7.2. It was then put forward that there had to be another factor which influenced human life , in tandem with Karman and rebirth. That unknown factor came to be accepted as the Fate. It was brought in as a powerful agent to reinforce ; and, to strengthen the Karman-theory. The apparent injustices were ascribed to fate, whose mystique could neither be remedied, nor unveiled.

Thus, along with Karman and rebirth, fate became the third factor in controlling human existence, life and destiny.

Fate and religion

8.1. All religions, cultures and sects have element of fatalism, in some form or other. A faith in an unknown force which controls human destiny is at the base of most religions and mythologies. Elaborate tales are spun to drive home the conviction that a mystery surrounds human existence; and, it will never be fully revealed.

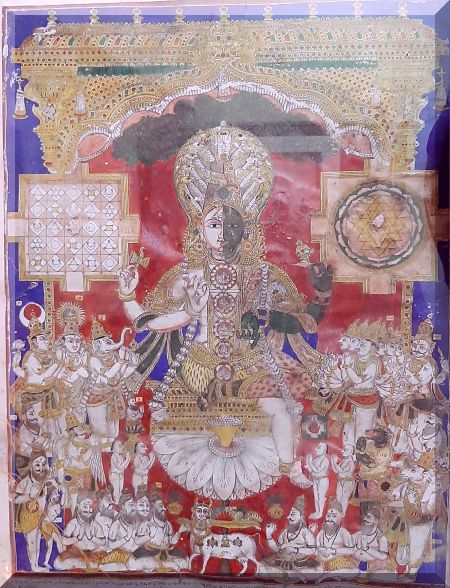

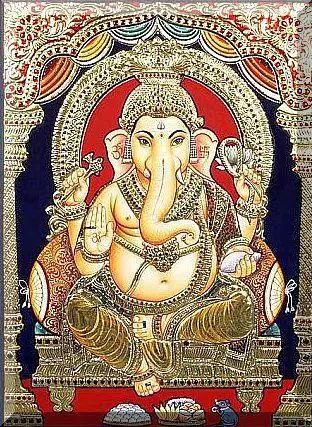

8.2. Most systems seek to see the God or gods and fate as distinct powers. In some theologies, the God is seen playing (Daiva Leela)with the fate , the grief and joys of his creatures; in some others , gods are subservient to fate; and , in few others, the gods and fate together exercise power over human destiny. In some cases, the fate , in one or other names, occupies a key position in the pantheon.

For instance; Fate is also equated with Time, kaala: ‘if kaala is adverse and angry, how, then, shall we escape? ..!’. Time , in human life , runs along a single direction; and , it rushes towards death. Hence , Time becomes synonymous with death. And, death becomes an essential constituent of fate, which terminates the course of life.

8.3. In the Vedic religion, which has a fluid pantheon, where new gods come and old gods fade away , rather quietly, Karman, rebirth and fate continued to play a role. The fate, here, is both dependent and independent of Karman, as it was deemed possible for an individual to exercise his free-will in order to correct himself ; and , to improve his future prospects.

8.4. In monotheism where nothing can happen without the will of God, the God will necessarily have to assume the role of fate too. Otherwise, if its follower believes in destiny as determined by fate, then there would be no room left for God, as the dispenser of destiny. Conversely, the fate , in effect, will necessarily have to be deemed as the will of god.

9.1. The things get bit more complicated when you put together the fate, the Karman, the grace of god and the human effort.

If one strongly believes in fate and its role in determining human destiny, then Karman becomes redundant. If ,on the other hand, one subscribes to the faith and belief that it is the Law of Karman , which governs human life and its future , then fate has no place in such a scheme of things. And, if one has immense faith in God , who in his infinite grace, over rides Karman and fate; then they together are rendered ineffective. In which case, total submission to god’s grace is the ultimate panacea for all worldly ills.

The diversity of the views regarding the relative merits of Karman, fate, divine favor and personal effort represent or depend upon the different anchors of human faith. Most theologies seek to reconcile these factors.

[Unfortunately, the theory of Karman got horribly tangled with ‘fate’; and , got confused for fatality; particularly when one grew feeble and was disinclined to do ones best. It became an excuse for inertia and timidity; and, it turned into a cry of despair, lacking hope.]

9.2. As regards human endeavor, one can never discount its efficacy in life. It is after all the man who decides the attitudes to adopt at varying times as he battles with life. It is also his decision to discard all or any of those approaches, or to relay on his own effort and judgment. Life has no meaning and is not worth living when human endeavor is not valued. Therefore, in day-to-day life, human endowed runs alongside some sort of faith.

Fate in Epics and Puranas

10.1. It is in the Epics and the Puranas that fate seems to take the center stage.

In the Ramayana and Mahabharata Epics, several situations are so crafted as if to bring human endeavor face-to-face with fate. In the many incidents narrated in the epics, fate does not act directly; but it takes subtler methods of clouding the victim’s wits. Sometimes, fate acts as a living human enemy, hurting the unsuspecting victims.

10.2. There are homilies that acknowledge the supremacy of fate as that which cannot be grasped by thought; and, as that which is not destroyed in creatures”(Ram: 2.20:20).

There are also remarkably brave statements which applaud human effort (purusakara or purusha-prayatna) ; and , decry dependence on fate as ‘false-games that people play and delude themselves ‘ : “when he cleaves to fate without conducting himself like a man, he labours in vain like a woman with an impotent husband (Mbh: 8:6:20)”; and, that “Low men given to indulgence of the passions blame the fate for their own evil deeds ” (Mbh: 8:67:1).

11.1. The principle characters of the Epics – Sri Rama and Yudhistira – lament and blame their miseries on fate: Who can fight against fate?”(Ram – 4:22:20); ”The man to whom fate allots defeat, it robs him of his intellect first and then he begins to see things in a reverse order. Fate robs him of vision, falling like an eye of fire on him” (Mbh: 2.73:8; 3:295:1).

But what is more important here is that the heroes of the Epics, despite their miseries and delusions, do not give up; but , keep on fighting resolutely till the end.

11.2. But, it is the relatively minor characters that stand up for human endeavour ; and, refuse to accept the verdict of fate. For instance; Lakshmana argues with his dejected brother : “why an able bodied man with his faculties intact should accept unjust verdicts of fate without protest?”.

His argument has a subtle point : when success is achieved by ones brave efforts, people tend to ascribe it to fate and destiny. That is unfair, according Lakshmana, as it robs the brave man of his well deserved glory. To Lakshmana, it is cowardly to submit to fate, to suffer injustice without protest, while it is possible to do so, and then blame the fate for his misery (Ram: Kishkinda Kanda).

11.3. Karna the tragic hero of Mahabharata though a Kshatriya by birth was not aware of his origin, because he grew up as a charioteer’s son. When others jeered him of his low extract, Karna retorted : “A charioteer or a charioteer’s son, whoever I may be, my birth was decreed by fate; but, I am the master of my valour”. Here was an instance of a proud self-confident person , who undertakes tasks and performs with faith in Purushakara.

11.4. The great battle of Mahabharata was, in one sense, a battle between fate and human effort. The warriors on either side knew well that victory was essentially uncertain; and, their own life was highly threatened . Yet, heroic men fought with great courage. Every warrior, mighty and small, had realized that meek acceptance of fate meant negating the glory of his manhood. Yet, each one was also prepared to conditionally accept his fate as a venture into an unknown zone riddled with startling events. And, regardless of the outcome, each fighter , even the ordinary one, was determined to battle courageously, more manfully and to fight against the mightier odds, if only to redeem his pride and that of his clan.

11.5. Mahabharata has some great statements on fate and human endeavour :

“Whatever the enterprising man ever does, he must do it fearlessly; and , the success however depends on fate (yasmād abhāvī bhāvī vā bhaved artho naraṃ prati aprāptau tasya vā prāptau na kaś cid vyathate budhaḥ – Mbh: 8:1.47)” ;

“as a lamp grows weak as the oil runs out, so the fate grows weak when the fruits of action are exhausted” (tasyādya karmaṇaḥ karṇaḥ phalaṃ prāpsyati dāruṇam – Mbh: 8:5:32).

12.1. Puranas were written mainly to glorify the powers, the splendor and supremacy of their principal gods or goddesses. They urge the devotee to surrender to the will and mercy of gods and goddesses. But, at the same time, they call upon men not to give up their efforts: “Some wise men call fate as the false hope that feeble cling to. For the powerful men, no fate is ever noticed. The heroic and the feeble take recourse to effort and fate respectively “(Devi Bhagavata: 5:12:28-30); and, “the wise hold that prowess is the best. Even an adverse fate can be overcome by the prowess of those of good conduct who are ever active and dedicated” (Matsya Purana).

Here, the emphasis is laid on human effort, without which even fate is powerless to achieve anything. Here , cleaving of fate is not condemned; but, doing so and abandoning personal effort is.

12.2. The Puranas tried to reconcile fate and human effort. There are several statements that emphasize that one should always be active in ones prescribed field of activity. And , that only the people without prowess talk of fate; many alas do not realize that it is primarily their effort (purusha-prayatna) that paves way for their salvation. They emphasize the importance of self-initiative. The Puranas and its legends assured that human effort (purushakara) blessed by fate would surely bear fruit, in due time.

**

Stoics – Fatalism –Freewill

13.1. Some of the Stoics believed in fatalism; but, none believed in complete Freewill. Throughout the history of philosophy, there has been a long debate; and, that, perhaps, will never be settled.

Freedom, they said, is relative and not an absolute. They argued; in a material universe, in which everything is subject to the laws of cause and effect, how could we possibly have free will?

Surely, if everything is governed by cause and effect, we are too. Everything we do — and our future ahead of us — is governed by causes that are out of our control. In fact, do we even have control over anything?

The Stoics believed that God was in all of nature. If God is in all of nature, then nature must be determined, there can be no room for “free will” in a universe that is all God ; because God is perfection.

The universe may seem flawed to us, but we have only a partial understanding of it; because, we are but a fragment of the whole. As a fragment of the whole, we simply could not stand apart from the universe to be free of the causal connections that make it up.

The problem with free will is that it is logically incoherent. To have full control of your destiny, you would have to be the cause of yourself.

*

The basis of Stoicism is to not take things for granted; but, to contemplate the very nature of our being

The ultimate lesson of Stoicism is this: to live a fulfilling life is to ask yourself difficult questions about what it is to be a human being. The Stoics prized reason above everything else; and, reason requires discipline.

According to Stoicism , knowing yourself and your place in the world will enable you to live up to the values that you set for yourself.

*

13.2. Chrysippus of Soli, head of the Athenian Stoic school in around 230 B.C. E, was probably the most famous Stoic in the distant past. All his writings are lost. All that we know of his work is through the later writers like Cicero.

Chrysippus is credited with creating a philosophical system of Stoicism, as we understand it. And, it had three equally important parts: logic, ethics and physics.

Further, there are three broad positions in regard to the human agency in a universe of causes and effects:

Fate or Determinism: is the belief that free will is impossible. The hardest determinists would argue that your life — every action and thought — has been mapped out since the beginning of time.

Free will: is the idea that we have free will. We can make choices in our lives that are influenced by, but not determined by, the external universe. Such Libertarianism would hold that we are wholly responsible for our actions.

Compatibility: takes for granted the idea that we live in a deterministic universe of cause and effect. However, it tries to reconcile an idea of human free will with the acceptance of determinism (Fate). Compatibility can be thought of as “soft determinism”.

*

The renowned philosopher Marcus Aurelius eminently summed up the basic tenets of Stoic philosophy

All things are linked with one another, and this oneness is sacred

Everything that happens happens as it should, and if you observe carefully, you will find this to be so.

[The Stoics believed that all events are predetermined; and , that you have either no control or very little control over circumstances. Everything is fated.]

You have power over your mind — not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.

[You may not be able to change the course of events, but you do, however, have control over your own thoughts and emotions.

The difference between the Stoic and the common man is in this example; the common man prays that he is spared of misfortune; the Stoic prays that he can find the strength to accept misfortune.]

The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.

[Since everything, according to the Stoics, is determined — “everything that happens happens as it should” — you could not do anything about the obstacles you may face. Instead the mind can only find an opportunity in the obstacle because the mind is all that we truly have control over.]

Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. Everything we see is a perspective, not the truth.

[The universe is perfect and true, but we are but one fragment of the whole so therefore cannot fully know that perfection and truth. ]

…the infallible man does not exist.

[Since there are only perspectives that are more or less true (and never fully true), there can be no definitive judgment.]

Waste no more time arguing what a good man should be. Be one.

[ Good conduct emanates from good character.]

The things you think about determine the quality of your mind. Your soul takes on the color of your thoughts.

[Since ethics lie in virtuous character, ones conduct depends on ones thought and reason.]

What we do in life ripples in eternity.

[We are a part of the universe and what we do in our lives is part of that eternity.]

The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts

***

Chrysippus, the philosopher, made a distinction between internal (mental) and external (physical) causes. To illustrate his point, he used the visual metaphor of the cylinder. If we push a cylinder on a flat surface it will roll forward. Our push was one necessary cause to get the cylinder rolling.

However, the cylinder’s shape — an intrinsic property — is what was sufficient to make it roll. If you pushed a cube, it would not roll, because it’s not in a cube’s nature to roll.

*

He then offered a complicated human situation. Let’s say I offer a bribe to a prison guard to get a friend out of jail.

My wad of cash is necessary for the guard taking the bribe — it is an external cause — but it is not a sufficient cause for the bribe to happen. What is sufficient for the successful bribe is the prison guard’s lax moral judgement.

Like the shape of the cylinder allows it to roll, the guard has to have an internal cause to take that decision. Chrysippus describes such decisions as “primary” causes for our actions.

Whether or not the guard takes the bribe is “up to him”’; but, it’s not a free choice. The guard’s choice is determined by his own internal make-up.

His “character”, which creates his dispositions, is again determined by a combination of his complex internal and external causes .

Because of the involvement of both the internal and external factors, the Stoics hold that our actions primarily belong to us, who are, in essence, the combination of both .

Thus, our actions are determined by a complex set of external and internal causes.

*

The Stoics avoid using the word “free-will” in the context of fate.

Chrysippus’ idea of “will” or “character” is determined by various degrees of “freedom; but it is more or less determined. We are more or less responsible for our actions; but, never entirely responsible.

The degree of freedom we have (and therefore responsibility) in a given situation depends upon two things: how narrow the choice permitted to us is; and , how cultivated our faculty for judgement is. The Stoics paid a lot of attention to the latter.

*

13.3. Freedom, they said, is rational self-sufficiency. The desire for material wealth, sex, fame and luxury is impinged upon us by extraneous causes – we are, by necessity ,dissatisfied when we desire.

Desire can be hard to fight. It is a “passion” that will inevitably rise up within us, but always remember that you have control over your emotions. Marcus Aurelius wrote in his Meditations:

“You have power over your mind — not outside events. Realise this and you will find strength.”

*

13.4. In effect, the Stoics argue that the more rational you are, the freer you are. The rational choice is easy; because, there is only one choice: the necessary choice.

Freedom is, therefore, a double-bind: freedom is choice; but, to be truly free , we should avoid choice. Our reason would dismiss desire as unnecessary to live in virtue and as freely as possible.

There’s not much choice in not wanting; but, wanting is not something that a rational person would choose.

But, the lesser you want; freer you are. This must seem absurd. Being free is surely about choice, after all. But there are different senses of freedom.

It is a paradox.

**

Fate and Human endeavor

14.1. It can be seen that absolute dependence on fate and the absolute reliance on human endeavor are projected as two extreme positions. It would however be prudent to recognize the limits of both; which is to say, one is powerless without the other or that where the one ends the other begins. Human endeavour, for instance, is the very act of living ; and, life has no meaning when human endeavor is not valued. Therefore, in day-to-day life, human endower runs alongside some sort of faith. But, one has also to recognize that even the most sophisticated of all human endeavors – let’s say launching of a space shuttle – involves and is subject to an element of unknown and unpredictable. You might assign that unpredictability in life whatever name you choose.

14.2. Shri DSamapath , elsewhere, remarked that in situations where one is faced with extremes there always are other possibilities open for resolving the conflicts. Those options might range from the middle path to the simultaneity of all possibilities. These, he calls as the metaphors of thought. Such multi-pointed approach would, naturally, take into account not merely the whole of a ‘metaphor’ but also its specific variations. It is in that context that the Vedic religion re-worked on the theory of Karman; and, rendered it more dynamic , by providing for the freedom of individual will, enabling him to correct the errors and to improve upon his good-performance. That was meant to convince that the outcome of one’s past action is not always beyond control or beyond modification, provided there is a strong will to so.

14.3. Shri D Sampath’s observation also implies that there could be as many approaches or attitudes to life as there are individuals. I agree with him. It appears to me that amidst all those options, what is important is to retain a sense of balance in life recognizing the limits of each of the factors that play an effective role in the different contexts of the varied spheres of human life.

As Uddalaka Aruni counsels his son, one has to understand life through reason grasped in faith: ‘śraddhatsva somyeti; Have faith, my dear’ (Ch. Up. 6.12.2). … What that faith is at the very core of each being.

To sum up:

Haman initiative and endeavor is highly essential in life; without that, life would collapse on itself. But, that does not say everything. At almost all levels , even at its most sophisticated and highest level , human effort involves and is subject to elements of unknown and unpredictable; you may assign them any name/s . Which suggests that human freedom is just operational; but, it is not absolute freedom.

Roger Sperry (1913-1994) a psycho biologist (neuro-psychologist and neuro-biologist) who won the Nobel Prize for his split-brain research) explained free will as follows

What one wants of free will is not to be totally freed from causation, but rather, to have the kind of control that allows one to determine one’s own actions according to one’s own wishes, one’s own judgment, perspective, cognitive aims, emotional desires and other mental inclinations.

We are free to select our assumptions. But to exercise this freedom, man must first realize that he is thus free. There could be as many assumptions and beliefs as there are individuals. Fate, god or such others could also be one of those beliefs. If one has firm conviction in ones belief and strives towards that, then ‘That’ would become the reality for him , in due time. And that is his faith, the very core of his being.

Leaving aside remarkable sages and saints, it appears to me, for the men and women of the world, it is important to retain a sense of balance ; and, to understand life through reason grasped in faith, as said.

]

]

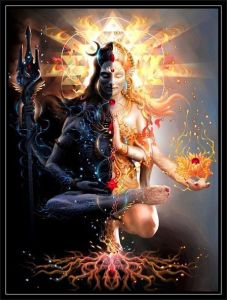

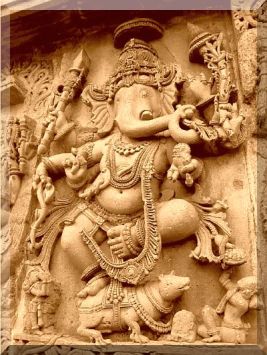

Buddhist Yama of Tibet

Buddhist Yama of Tibet

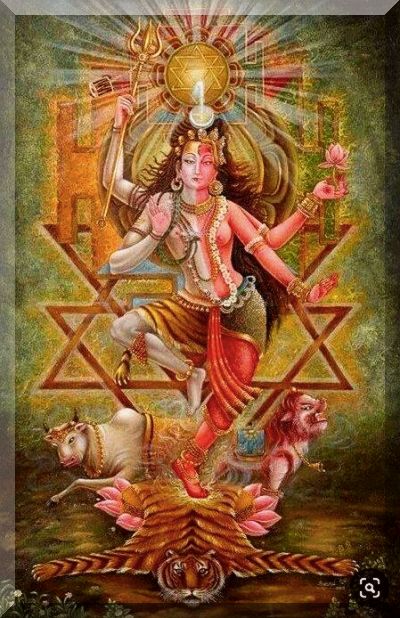

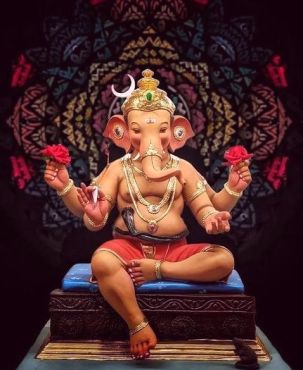

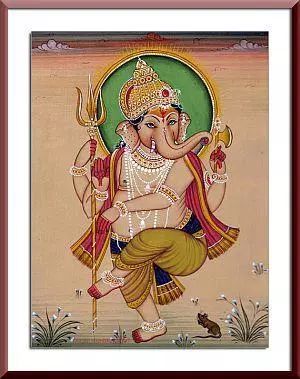

(Devi as Ardha-purusha)

(Devi as Ardha-purusha)