This may be treated as a sequel to my earlier blog Abhinavagupta wherein I presented a brief life sketch of the great scholar and mystic. I made, therein, a passing reference to his monumental work Abhinavabharati (a commentary on Bharata’s Natyasastra) but could not discuss its salient features as the blog was already getting lengthy. I propose to talk here about a few aspects of Abhinavabharati. It would not be a review or a commentary on the great work, because such a task is beyond my capabilities. I shall try to avoid as many technical terms as possible.

1. Abhinavagupta (11th century) was a visionary endowed with incisive intellectual powers of a philosopher who combined in himself the experiences of a mystic and a tantric. He was equipped with extraordinary skills of a commentator and an art critic. His work Abhinavabharati though famed as a commentary on Bharata’s Natyasastra is, for all purposes, an independent treatise on aesthetics in Indian dance, poetry, music and art. Abhinavabharati along with his other two works Isvara pratyabhijna Vimarshini and Dhvanyaloka Lochana are important works in the field of Indian aesthetics. They help in understanding Bharata and also a number of other scholars and the concepts they put forth.

2. There are only a handful of commentaries that are as celebrated, if not more, as the texts on which they commented upon. Abhinavabharati is one such rare commentary. Abhinavagupta illumines and interprets the text of the Bharata at many levels: conceptual, structural and technical. He comments, practically, on its every aspect; and his commentary is a companion volume to Bharata’s text.

3. There are a number of reasons why Abhinavabharati is considered a landmark work and why it is regarded important for the study of Natyasastra. Just to name a few, briefly:

(i).The Natyasastra is dated around second century BCE. The scholars surmise that the text was reduced to writing several centuries after it was articulated. Until then, the text was preserved and transmitted in oral form. The written text facilitated reaching it to different parts of the country and to the neighbouring states as well. But, that development of turning a highly systematized oral text in to a written tome, strangely, gave rise to some complex issues, including the one of determining the authenticity of the written texts. Because, each part of the country, where the text became popular, produced its own version of Natyasastra and in its own script.

For instance, Natyasastra spread to Nepal, Almora to Ujjain, Darbhanga, Maharashtra, Andhra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The earliest known manuscripts which come from Nepal are in Newari script. The text also became available in many other scripts – Devanagari, Grantha, Tamil, Kannada, Telugu and Malayalam. There were some regional variations as well. It became rather difficult for the later-day scholars, to evolve criteria for determining the authenticity and purity of the text particularly with the grammatical mistakes and scribes errors that crept in during the protracted process of transliterations. Therefore, written texts as they have comedown to us through manuscripts merely represent the residual record or an approximation to the original; but not the exact communication of the oral tradition that originated from Bharata.

[Similar situation obtains in most other Indian texts/traditions.]

His commentary Abhinavabharati dated around tenth or the eleventh century predates all the known manuscripts of the Natyasastra, which number about fifty-two; and all belong to the period between twelfth and eighteenth century. The text of Natyasastra that Abhinavagupta followed and commented upon thus gained a sort of benchmark status.

(ii). Because Natyasastra was, originally, transmitted in oral form, it was in cryptic aphoristic verses –sutras that might have served as “memory-aid” to the teachers and pupils, with each Sutra acting as pointer to an elaborate discussion on a theme. The Sutras, by their very nature, are terse, crisp and often inscrutable. Abhinavabharati, on the other, hand is a monumental work largely in prose; and it illumines and interprets the text of the Bharata at many levels, and comments on practically every aspect of Natyasastra. Abhinava’s commentary is therefore an invaluable guide and a companion volume to Bharata’s text.

(iii). Abhinavabharati is the oldest commentary available on Natyasastra. All the other previous commentaries are now totally lost. And , therefore , the importance of Abhinavagupta’s work can hardly be overstated. The fact such commentaries once existed came to light only because Abhinavagupta referred to them in his work and discussed their views.

Abhinava is the only source for discerning the nature of debate of his predecessors such as Utpaladeva , Bhatta Lollata, Srisankuka, Bhatta Nayaka and his Guru Bhatta Tauta. It is through Abhinavagupta’s quotations from Kohala , whose work is occasionally referred to in the Natyashastra, that we can reconstruct some of the changes that took place in the intervening period between his time and Bharata’s. Among other authorities cited by Abhinavagupta are : Nandi, Rahula, Dattila, Narada, Matanga, Visakhila, Kirtidhara, Udbhata, Bhattayantra and Rudrata, all of whom wrote on music and dance.

The works of all those masters can only be partially reconstructed through references to them in Abhinavabhrati. Further, Abhinavagupta also brought to light and breathed life into ancient and forgotten scholarship of fine rhetoricians Bhamaha, Dandin and Rajashekhara.

Abhinava also drew upon the later authors to explain the application of the rules and principles of Natya. For instance; he quotes from Ratnavali of Sri Harsh (7th century); Venisamhara of Bhatta Narayana (8th century); as also cites examples from Tapaas-vatsa-rajam of Ananga Harsa Amataraja (8th century) and Krtyaravanam (?).

[ But, it is rather surprising that Abhinava does not mention or discuss the works of renowned dramatists such as Bhasa, Sudraka, Visakadatta and Bhavabhuti, though he regards Valmiki and Kalidasa as the greatest of the writers.]

What was interesting was that each of those scholars was evaluating Bharata’s exposition of the concepts of rasa and Sthayibhava against the background of the tacit assumptions of their particular school of thought such as Samkhya, yoga and others. Abhinavagupta presented the views of his predecessors and then went on to expound and improve upon Bharata’s cryptic statements and concepts in the light of his own school –Kashmiri Shaivism.

As Prof. Mandakranta Bose observes :

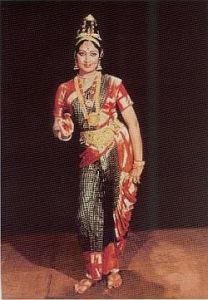

One of the most illuminating features of Abhinav Gupta’s work is his practice of citing and drawing upon the older authorities critically , presenting their views to elucidate Bharata’s views ; and , often rejecting their views , putting forth his own observations to provide evidence to the contrary . For instance, while explaining the ardhanikuttaka karana which employs ancita of the hands, Sankuka’s description, which is different from Bharata’s, is included. Abhinav Gupta’s citation of the two authorities thus shows us that this karana was performed in two different ways.

It is apparent that Abhinava’s grasp of the subject was not only extraordinarily thorough but was also based on direct experience of the art as it was practiced in his time. From his experience , he explains the Natyashastra according to the concepts current in his own time. And, many times , therefore, he differed from Bharata. And, often he introduced concepts and practices that were not present during Bharata’s time. For instance, Abhinavagupta speaks of minor categories of drama, such as nrttakavya and ragakavya – the plays based mainly in dance or in music. The concept of such minor dramas was , however, not there in the time of Natyashastra .

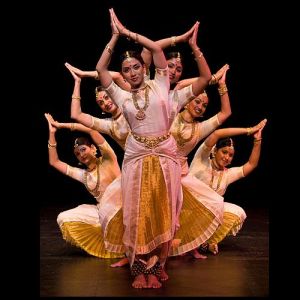

Abhinavagupta provides the details of several dance forms that are mentioned but not described in the Natyasastra. For instance, he describes bhadrasana, one of the group dances termed pindlbandha by Bharata but not described by him .

His commentary on the fifth Chapter of Natyashastra expands on Bharata’s description of the preliminaries of a dramatic performance ; and , covers such topics as the use of Tala, vocal and instrumental music, and the arousal of the sringara and raudra rasas in course of depictions of gods and goddesses.

Abhinavagupta , thus, not only expands on Bharata but also interprets him in the light of his own experience and knowledge . His commentary , therefore, presents the dynamic , and evolving state of the art of his time, rather than a description of Natya as was frozen in Bharata’s time .

(iv).Abhinavaguta’s influence has been profound and pervasive. Succeeding generations of writers on Natya have been guided by his concepts and theories of rasa, bhava, aesthetics and dramaturgy. No succeeding writer or commentator could ignore Abhinavaguta’s commentary and the discussions on two crucial chapters of the Natyasastra namely VI and VII on Rasa and Bhava.

His work came to be accorded the highest authority and was regarded as the standard work , not only on music and dance but on poetics (almkara shastra) as well. Hemacandra in his Kavyanusasana, Ramacandra and Gunacandra in their Natyadarpana, and Kallinatha in his commentary on the Sangitaratnakara often refer to Abhinavagupta. The chapter on dance in Sarangadeva’s Sangitaratnakara is almost entirely based on Abhinava’s work.

Abhinavabharati is thus a bridge between the world of the ancient and forgotten wisdom and the scholarship of the succeeding generations.

(v). Abhinavagupta turned the attention away from the linguistic and related abstractions; instead, brought focus on the human mind, specifically the mind of the reader or viewer or the spectator. He tried to understand the way people respond to a work of art or a play. He called it Rasa-dhvani. According to which the spectator is central to the active appreciation (anuvyavasāya) of a play.

He placed the spectator at the centre of the aesthetic experience. He said the object of any work of art is Ananda . He emphasized that the Sahrudaya, the initiated spectator/audience/receptor, the one of attuned heart, is central to that experience. Without his hearty participation the expressions of all art forms are rendered pointless. An educated appreciation is vital to the manifestation and development of art forms. And, an artistic expression finds its fulfillment in the heart of the recipient.

The aim of a play might be to provide pleasure; that pleasure must not, however, bind but must liberate the spectator.

4. Abhinavabharati just as Natyasastra is also a bridge between the realms of philosophy and aesthetics, and between aesthetic and mysticism. Abhinava did not consider aesthetics and philosophy as mutually exclusive. On the other hand, his concepts of aesthetics grew out of the philosophies he admired and practiced – the Shiva siddantha.

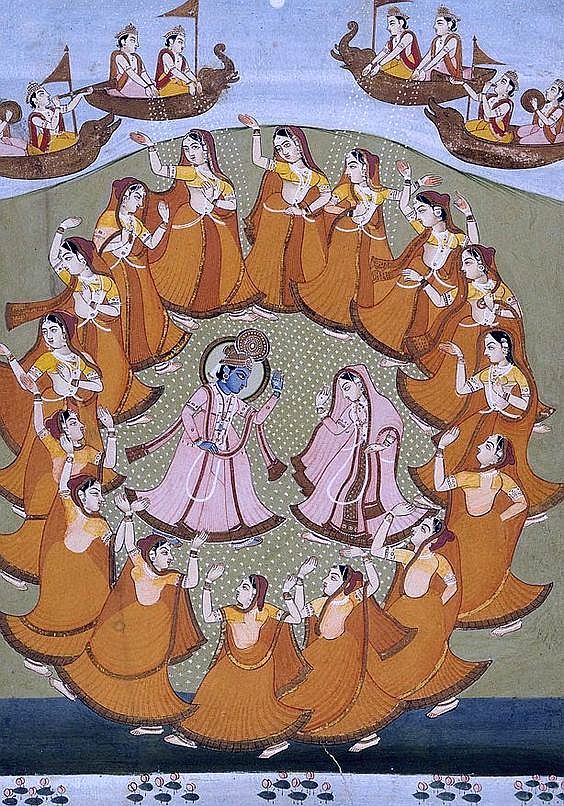

Interestingly, while Abhinavagupta extended and applied philosophical schools of thought to understand and to explain concepts such as rasa, bhava etc, the latter-day exponents of aesthetics such as the Gaudiya Vaishnavas, reversed the process. They strove to derive a school of philosophy by lending interpretations to poetic compositions and to the characters portrayed in them. For instance. The Vaishnavas interpreted poet Jayadeva’s most adorable poetry Gita_Govinda; and its characters of Krishna and Radha in their own light; and derived from that, a new and a vibrant philosophy of divine love based in Bhakthi rasa.

The two approaches have become so closely intertwined that it is now rather difficult to view them separately. In any case, they enrich and deepen the understanding of each other.

6. The aesthetics and philosophy, in his view, both aim to attain supreme bliss and freedom from the mundane. Along their journey towards that common goal, the two, at times, confluence as in a pilgrimage; interact or even interchange their positions.

Abhinava’s view, in a way, explains the thin and almost invisible dividing line between the sacred and profane art; religious and secular art; or between religion and art in the Indian context.

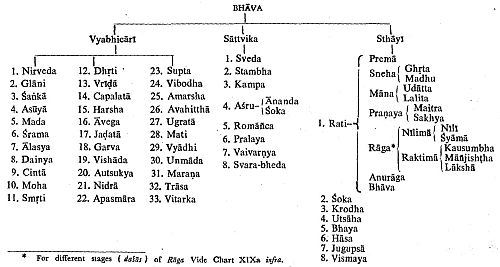

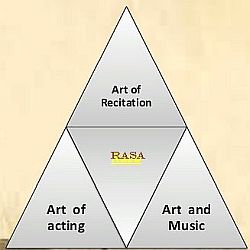

8. The famous Rasa sutra or basic formula to invoke Rasa, as stated in the Nāṭyasāstra, is :

– vibhāva anubhāva vyabbhicāri samyogāt rasa nispattih.

Vibhāva represents the causes, while Anubhāva is the manifestation or the performance of its effect communicated through the abhinaya.

The more important vibhāva and anubhāva are those that invoke the sthāyi bhāva, or the principle emotion at the moment of the performance. The Sthayibhava combines and transforms all other Bhavas ; and , make them one with it.

Thus, the Rasa sutra states that the Vibhāva, Anubhāva, and Sanchari or the Vyabhicāri bhāvas together (samyogād) produce Rasa (rasa nispattih).

[ Mammata says that vibhavas, anubhavas and vyabhicchari-bhavas are called so only in case of a drama or a poem. In the practical world , they are known simply as causes, effects and auxiliary causes respectively.

Karananyatha karyani sahakarini yani ca/ Ratyadeh sthayino loke tani cen natya-kavyayoh/ Vibhava anubhavasca kathyante vyabhiicarinah/ Vyakah sa tair vibhavadyaih sthayibhavo smrtah // (Kayaprakasha .4.27-28 ) ]

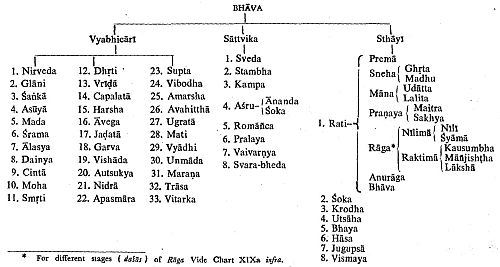

[ In the context of the Drama and Poetry , the terms Vibhava, Anubhava, Sanchari, Sattvika and Sthayi are explained thus:

Vibhava, Vibhavah, Nimittam, and Hetu all are synonyms; they provide a cause through words, gestures and representations to manifest the intent (vibhava-yante); and the term Vibhavitam also stands for Vijnatam – to know vividly. The Vibhavas are said to be of two kinds : Alambana, the primary cause (kaarana) or the stimulant for the dominant emotion ; and , Uddipana that which inflames and enhances the emotion caused by that stimulant.

‘Anu’ is that which follows; and, Anubhava is the manifestation or giving expression the internal state caused by the Vibhava. It is Anubhava because it makes the spectators feel (anubhavyate) or experience the effect of the acting (Abhinaya) by means of words, gestures and the sattva. Thus, the psychological states (Bhavas) combined with Vibhavas (cause) and Anubhavas (portrayal or manifestations) have been stated.

Vybhichari bhava or Sanchari Bhavas are complimentary or transitory psychological states. Bharata mentions as many as thirty-three transitory psychological states that accompany the Sthayi Bhava, the dominant Bhava that causes Rasa.

The Sattvika Bhavas are reflex actions or involuntary bodily reactions to strong feelings or agitations that take place in ones mind. Sattvas are of eight kinds : Stambha (stunned and immobile); (Svedah sweating); Romanchaka (thrilled, hair-standing-on-end); Svara bedha (change in voice); Vipathuh (trembling); Vivarnyam (pale or colorless); Asru ( breaking into tears); and, Pralaya ( fainting). These do help to enhance the effect of the intended expression or state of mind (Bhava).

The Sthayi Bhavas , the dominant Bhavas, which are most commonly found in all humans are said eight : Rati (love); Hasya (mirth); Sokha (sorrow); Krodha (anger); Utsahah (energy); Bhayam (fear); Jigupsa (disgust); andl Vismaya ( wonder).

Thus, the eight Sthāyi bhavās, thirty-three Vyabhicāri bhāvās together with eight Sātvika bhāvas, amount to forty-nine psychological states, excluding Vibhava and Anubhava.

Bharata lists the eight Sthayibhavas as:

-

-

- Rati (love);

- Hasaa (mirth);

- Shoka (grief);

- Krodha(anger);

- Utsaha (enthusiasm or exuberance) ;

- Bhaya (fear) ;

- Jigupsa (disgust) ; and

- Vismaya (astonishment).

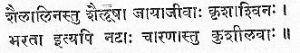

rati-hāsaśca śokaśca krodho-utsāhau bhayaṃ tathā । jugupsā vismayaśceti sthāyibhāvāḥ prakīrtitāḥ ॥ 6. 17॥

And , each of these Sthayibhavas gives rise to a Rasa.

Rati to Srngara Rasa; Haasa – Hasya; Shokha – Karuna; Krodha – Raudra ; Utsaha – Veera; Bhaya- Bhayajaka; Jigupsa – Bhibhatsa; and, Vismaya – Adbhuta.

śṛṅgāra-hāsya-karuṇā-raudra-vīra-bhayānakāḥ।bībhatsā-adbhuta saṃjñau cetyaṣṭau nāṭye rasāḥ smṛtāḥ ॥ 6.15॥

The Eight Sattivikbhavas are;

-

-

- Stambhana (stunned into inaction);

- Sveda (sweating);

- Romancha (hair-standing on end in excitement);

- Svara-bheda (change of the voice or breaking of the voice);

- Vepathu (trembling);

- Vairarnya (change of color, pallor);

- Ashru (shedding tears); and,

- Pralaya (fainting) .

stambhaḥ svedo’tha romāñcaḥ svarabhedo’tha vepathuḥ । vaivarṇyam-aśru pralaya ityaṣṭau sātvikāḥ smṛtāḥ ॥ 6.22॥

The Sanchari-bhavas or Vybhichari-bhavas are enumerated as thirty in numbers; but, there is scope a few more. They are :

-

-

- Nirveda (indifference);

- Glani (weakness or confusion);

- Shanka (apprehension or doubt);

- Asuya (envy or jealousy);

- Mada (haughtiness, pride),

- Shrama (fatigue);

- Alasya (tiredness or indolence),

- Dainya (meek, submissive),

- Chinta (worry,anxiety);

- Moha (excessive attachment,delusion),

- Smriti (awareness,recollection),

- Dhrti (steadfast);

- Vrida (shame);

- Chapalata (greed ,inconsistency);

- Harsa (joy);

- Avega (thoughtless response, flurry);

- Garva (arrogance, haughtiness);

- jadata (stupor, inaction );

- Vishada (sorrow, despair);

- Autsuka (longing);

- Nidra (sleepiness);

- Apsamra (Epilepsy);

- Supta (dreaming),

- Vibodha (awakening);

- Amasara (indignation);

- Avahitta (dissimulation);

- Ugrata (ferocity),

- Mati (resolve);

- Vyadhi (sickness);

- Unmada (insanity);

- Marana (death);

- Trasa (terror); and,

- Vitarka (trepidation).

Source : Laws practice Sanskrit drama by Prof. S N Shastri

Dhanika explains these Bhavas as follows-:

Vibhāva indicates the cause, while Anubhāva is the performance of the bhāva as communicated through the Abhinaya. The more important Vibhāva and Anubhāva are those that invoke the Sthāyi bhāva, or the principle emotion at the moment. Thus, the Rasa-sutra states that the Vibhāva, Anubhāva, and Vyabhicāri bhāvas together produce Rasa.

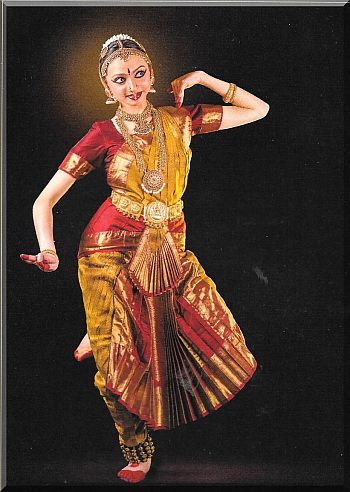

These Bhavas are expressed by the performer with the help of speech (Vachika); gestures and actions (Angika) , and costumes etc., (Aharya).

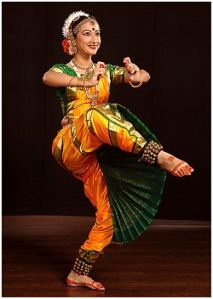

The Āngika-abhinaya (fascial expressions, gestures/movement of the limbs) are of great importance, particularly in the dance. There are two types of basic Abhinayas: Padārtha-abhinaya (when the artist delineates each word of the lyrics with gestures and expressions); and, or Vākyārtha-abhinaya (where the dancer acts out an entire stanza or sentence). In either case, though the hands (hastha) play an important part, the Āngika-abhinaya involves other body-parts , as well, to express meaning of the lyrics , in full .

Here, the body is divided into three major parts – the Anga, Pratyanga and Upānga

1) The six Angās -:

-

-

- Siras (head);

- Hasta (hand);

- Vakshas (chest);

- Pārshva (sides);

- Kati-tata (hips); and,

- Pāda ( foot ).

Some consider Grivā (neck) to be the seventh

2) The six Pratyangās -:

-

-

- Skandha (shoulders);

- Bāhu (arms);

- Prusta (back);

- Udara (stomatch);

- Uru (thighs);

- Janghā (shanks).

Some consider Manibandha (wrist); Kurpara (elbows) and Jānu (knees) also as Pratyanga

3) The twelve Upāngās or minor parts of the head or face which are important for facial expression.-:

-

-

- Druṣṭi (eyes)

- Bhrū (eye-brows);

- Puta (pupil);

- Kapota (cheek);

- Nāsikā (nose);

- Adhara (lower lip)

- Ostya (upper lip);

- Danta (teeth)

- Jihva ( tongue) etc,. ]

****

It is explained; they are called Bhavas because they happen (Bhavanti), they cause or bring about (Bhavitam); and, are felt (bhava-vanti). Bhava is the cause bhavitam, vasitam, krtam are synonyms. It means to cause or to pervade. These Bhavas help to bring about (Bhavayanti) the Rasas to the state of enjoyment. That is to say : the Bhavas manifest or give expression to the states of emotions – such as pain or pleasure- being experienced by the character

– Sukha duhkha dikair bhavalr bhavas tad bhava bhavanam//4.5//

Bharata explains they are called Bhavas because they effectively bring out the dominant sentiment of the play – that is the Sthāyibhāvā – with the aid of various supporting expressions , such as words (Vachika), gestures (Angika), costumes (Aharya) and bodily reflexes (Sattva) – for the enjoyment of the good-hearted spectator (sumanasaḥ prekṣakāḥ) . Then it is called the Rasa of the scene (tasmān nāṭya rasā ity abhivyākhyātāḥ).

Nānā bhāvā abhinaya vyañjitān vāg aṅga sattopetān / Sthāyibhāvān āsvādayanti sumanasaḥ prekṣakāḥ / harṣādīṃś cā adhigacchanti । tasmān nāṭya rasā ity abhivyākhyātāḥ //6.31//

The terms Samyoga and Nispatti are at the center of all discussions concerning Rasa.

Bharata used the term Samyogad in his Rasa sutra (tatra vibhāvā-anubhāva vyabhicāri saṃyogād rasa niṣpattiḥ ), to indicate the need to combine these Bhavas properly. It is explained; what is meant here is not the combination of the Bhavas among themselves; but, it is their alignment with the Sthayibhava the dominant emotion at that juncture.

It is only when the Vibhava (cause or Hetu), Anubhava (manifestation or expression) and sancharibhava (transitory moods ) as also the Sattvas ( reflexes) meaningfully unite with the Sthayibhava, that the right , pleasurable , Rasa is projected (Rasapurna).

The Sthayi bhava and Sanchari bhava cannot be realized without a credible cause i.e., Vibhava , and its due representations i.e., Anubhava. The Vibhavas and Anubhavas as also Sattva, on their own, have no relevance unless they are properly combined with the dominant Sthayibhava and the transient Sanchari bhava.

That is to say; it is only when the Sthayi bhava combines all these through Sanchari bhava , and transforms them eventually Rasa could be produced ; else, the Vibhava and Anubhava etc., on their own are of no value.

Bharata uses the term Nispatthi (rendering) for realization of the Rasa in the heart and mind of the Sahardya.

[Bharata made a distinction between Rasa and Sthayin. He discussed eight Rasas and eight Sthayins separately in his text.

He also omitted to mention Sthayin in his Rasa-sutra. But, he asserted that only Sthayins attain the state of Rasa. And in the discussion on the Sthayins , Bharata elaborated how these durable mental states attain Rasatva .]

Dhananjaya also explains that such desired Rasa results only when the Sthayin produces a pleasurable sensation by combining the Vibhavas, Anubhavas and the Sattvikas; as also the Sanchari Bhavas

vibhavair anubhavais ca sattvikair vyabhicaribhih aniyamanah svadyatvam sthayi bhavo rasah smrtah//

Bharatha explains: when the nature of the world possessing pleasure and pain both is depicted by means of representations through speech, songs, gestures , music and other (such as, costume, makeup, ornaments etc ) it is called Natya. (NS 1.119)

yo’yaṃ svabhāvo lokasya sukha duḥkha samanvitaḥ । som gādya abhinaya ityopeto nātyam ity abhidhīyate ॥ 1.119॥

Dr. Natalia R Lidova writes in her learned paper – Rasa in the Natyashastra -Aesthetic and the Ritual

The Nāṭyaśāstra presents the concept of rasa as a three-level hierarchy. The first level, initial in a sense, materializes in the vibhāvas (causes) and anubhāvas (manifestations , which condition the choice of scenic representational means, termed abhinayas by the author. Man’s actions and responses, and as surrounding best suited to his feelings are represented on stage with the help of a range of devices, which help to disclose the message and content of the drama. In this, the vibhāvas concern the scenic props, make-up, costumes and mise-en-scènes while the anubhāvas determine the choice of acting device

So, why is it called vibhāva ? It is said that the vibhāva is an instrument of knowledge.Vibhāva is [the same as] ‘cause’, ‘motive’, ‘impulse’ –[all these words are synonyms]. It determines such means of representation as speech, movements of the body and manifestations of thenature. That is why it is called vibhāva . Just as ‘defined’ and ‘comprehended’ are words close in their meaning”

[atha vibhāva iti kasmāt | ucyate vibhavo vijñānārthaḥ |vibhāvaḥ kāraṇaṁ nimittaṁ hetur-iti paryāyāḥ |vibhāvyate’nena vāg-aṅga-sattva-abhinayā ity-ato vibhāvaḥ |yathā vibhāvitaṁ vijñātam-ity-anartha-antaram NŚ, p. 92].

Also: It is called vibhāva, because it defines many meanings of the drama resting on such means of representation as speech and movements of the body”

[bahavo’rthā vibhāvyante vāg-aṅga-abhinaya-āśritāḥ | anenayasmāt-tena-ayaṁ vibhāva iti saṁjñitaḥ NŚ 7.4]

As for the anubhāva, “the means of representation produced by speech , movements of the body and manifestations of nature is perceived with this (anubhāvyate’nena vāg-aṅga-sattvaiḥ-kṛto’bhinaya iti NŚ, p.92).

The same idea is expressed in verse a bit later in greater detail: “As the message of the drama is perceived with the help of such means of representation as speech and movements of the body, when combined with speech and the movements of the principal and auxiliary parts of the body, it is known as anubhāva

[vāg-aṅga-abhinayena-iha yatas-tv-artho’nubhāvyate | vāg-aṅga-upāṅga-saṁyuktas-tv-anubhāvas-tataḥ smṛtaḥ NŚ 7.5 ]

The treatise demands the vibhāvas and anubhāvas be related to natural human conduct in particular practical situations andthere are so many that define all of them is simply impossible:“ vibhāvas and anubhāvas are well known in the world. For the reason of their closeness to the nature of the world, their traits are not specified in order to prevent excessive liking for specification.

[vibhāva-anubhāvau loka-prasiddhāv-eva | loka-svabhāva-upagatatvāc-ca-eṣāṁ lakṣaṇaṁ na-ucyate | ati- prasaṅga-nivṛty-arthañ-ca NŚ, p. 92[

And further on: The wise know the vibhāvas and anubhāvas, as well as the means of representation that fully reflect the essense of the world and follow the ways of the world.

[loka-sva-bhāva-saṁsiddhā loka-yātrā-anugāminaḥ | anubhāva-vibhāvāś-ca jñeyās-tv-abhinayair budhaiḥ NŚ 7.6]

As the theatre merely imitates reality, the combination of vibhāvas and anubhāvas causes the emergence of a purely theatrical image, the bhava , which imitates natural human conduct and, at the same time, essentially differs from it.

Unlike the number of vibhāvas and anubhāvas , which is practically unlimited, as is the number of actual situations in real life and spontaneous human reactions to them, the bhāvas are limited innumber. The treatise indicates it as: “eight stable bhāvas, thirty three transitory and eight essential ones – such are the three varieties”

[aṣṭau bhāvāḥ sthāyinaḥ | trayas-triṁśad-vyabhicāriṇaḥ | aṣṭau sātvikā iti bhedāḥ NŚ, p. 92]

*

The treatise offers two types ofrasa description.

The first sees rasa as a dramatic structural link and presents the technicalities of its achievement. In this, rasa emerges as natural result of the various production elements interacting, and really does come close to bhāva

The second kind of description characterizes the impact of rasa on the audience and defines the essential features of this phenomenon.

To the definitions of the essence of rasa which, as I see it, the author of the treatise borrowed from the older tradition , belong all that concern the interpretation of the term rasa , based on its comparison with the pleasure experienced by the eater of an excellently cooked dish. I sought to see in this context the number of protecting gods and color associations, the emergence of rasa from sthāyibhāva , and its impact on the audience, i.e., the description of rasa in its receptive aspect – as a kind of savouring.

The concept of rasa in the Nāṭyaśāstra is a conglomeration of information, more or less devoid of inner contradictions – information coming from various eras when theoretical substantiation was being sought for the theatre. The treatise retains an echo of the past when the rasa emerged as sacral idea and the bhava as an aesthetic emotion that promotes it. At the same time, it contains a concept of the rasa as an element of the artistic structure close to the bhava typologically and by the nature of its manifestation.

The many layers of which the idea of the rasa consists in the treatise account for the heterogeneity of its content and bred the various interpretations that occurred in the mediaeval tradition of the theory of drama.

Characteristically, mediaeval theoreticians were concerned about the same several fundamental questions: whether the rasa and the bhāva belonged to phenomena of the same nature; or whether the rasa was something entirely different; whether all rasas could produce the most sublime form of bliss (ānanda-rūpa) or whether some rasas produced pleasant sensations (sukha) and the others disagreeable ones (duḥkha); and, last but not least, whether the rasa was transcendental, supernatural and other-worldly (alaukika) or it entirely belonged to the earthly world (laukika).

*

Abhinavagupta finally put the matter to rest in some of these questions . His main merit was that he brought back to the rasa its original status of the sublime goal , or, to use Indian theoreticians’ vocabulary, of “the soul of poetry”. It was repeatedly suggested that in the Abhinavabharātī.

Abhinavagupta not so much interpreted the theory of rasa presented in the Nāṭyaśāstra as brought forth an original aesthetic concept. As it really is, it becomes evident in attentive reading that Abhinavagupta proceeded from the Nāṭyaśāstra and, possibly, also relied on oral and other traditions to revive the original concept of rasa.

As he saw it, though the sthāyi-bhāva was generating (siddha), while the rasa generated (sādhya); the former was an earthly sensation ordinary and common by nature (sādhāraṇa); while the rasa was extraordinary (asādhāraṇa ), unique and transcendental , while its perception (rasāsvāda) brought special pleasure (camatkāra) and the utmost bliss (ānanda -rūpa ), comparable to the yogi’s religious ecstasy in the contemplation and cognition of Brahman.

In the years that followed, Abhinavagupta’s interpretation of rasa became dominant and was supported by almost all theoreticians of the 11th-14th centuries CE. It had an impact on the 15th century doctrine of bhaktī-rasa in Gaudiya Viṣṇavism

*

As I see it, three stages can be singled out in the evolution of the concept of rasa :

first, its emergence as a symbolic expression of a ritualistic content;

second, close in time to the Nāṭyaśāstra , when rasa evolved into a theoretical term and acquired a specific aesthetic content, which gradually ousted its sacral essence;

and the third, when the aesthetic aspect became dominant, but the transcendental (alaukika) element of rasa was also singled out and emphasized in the late philosophical and mystical tradition.

As the result, the sacral aspect of the analyzed category was the reason for the unique popularity and broad dissemination of the concept of rasa.

Dhanajaya explains Natya as an art form that is based in Rasa – Natyam rasam-ashrayam (DR.I. 9). It gives expressions to the inner or true meaning of the lyrics through dance gestures – vakyartha-abhinayatmaka

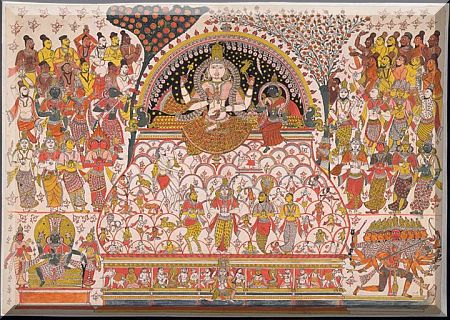

Natyashastra (6.10) provides a comprehensive framework of the Natya, in a pellet form, as the harmonious combination (saṅgraha) of the various essential components that contribute towards the successful production of a play.

Rasā bhāvā hya abhinayāḥ dharmī vṛtti pravṛttayaḥ । siddhiḥ svarās tathā atodyaṃ gānaṃ raṅgaśca saṅgrahaḥ ॥ 6.10॥

The successful production (Siddhi) of a play enacted on the stage (Ranga) with the object of arousing joy (Rasa) in the hearts of the spectators involves various elements of the components of the actors’ gestures, actions (bhava) and speech ; bringing forth (abhinaya) their intent, through the medium of theatrical ( natya dharmi) and common (Loka dharmi) practices; in four styles of representations (Vritti-s) in their four regional variations (pravrttis) ; with the aid of melodious songs accompanied by instrumental music (svara-gana-adyota).

The Naṭyashastra asserts that the goal of any art form is to invoke Rasa, the aesthetic enjoyment of the cultured spectator (sumanasaḥ prekṣakāḥ or Sahrudaya) . And, such enjoyment has got to be an emotional or an intellectual experience : Na rasanāvyāpāra āsvādanam,api tu mānasa eva ( N.S ,6.33)

Abhinava begins by explaining his view of aesthetics and its nature. Then goes on to state how that aesthetic experience is created. During the process, he comments on Bharata’s concepts and categories of Rasa and Sthayibhava, the dominant emotive states , and of Sattvika , the involuntary bodily reflexes .

He also examines Bharata’s other concepts of Vibhava, Anubhava and vyabhichari (Sanchari) bhavas and their subcategories Uddipana (stimulant) and Aalambana (ancillaries).

Abhinava examines these concepts in the light of Shaiva philosophy; and explains the process of One becoming many and returning to the state of repose (vishranthi). [I would not be discussing here most of those concepts.]

For Abhinavagupta, soaked in sublime principles of Shaiva Siddantha, the aesthetic experience is Ananda the unique bliss.He regards such aesthetic experience as different from any ordinary experience; and, as a subjective realization. It is Alukika (out of the ordinary world), he said, and is akin to mystic experience. That experience occurs in a flash as of a lightening; it is a Chamatkara. It is free from earthly limitations and is self luminous (svaprakasha). It is Ananda.

Abhinavagupta and Dhananjaya agree that Rasa is always pleasurable (Ananadatmaka); and Bhattanayaka compares such Rasanubhava (experience of Rasa) to Brahma-svada, the relish of the sublime Brahman.

[The scholars , Ramachandra and Gunachandra , the authors of Natyadarpana (12th century), argued against such ‘impractical’ suppositions. They pointed out that Rasa, in a drama, is after-all Laukika ( worldly , day-to-day experience); it is a mixture of pain and pleasure (sukha-dukka-atmako-rasah) ; and , it is NOT always pleasurable (Ananadatmaka) . They argued , such every-day experience cannot in any manner be Chamatkara or A-laukika (out of the world) ecstasy comparable to Brahmananda etc.

They pointed out that the reader or the spectator enjoys reading poetry or witnessing a Drama not because he relishes pain or horror; but, because he appreciates the art and skill of the poet or the actors in portraying varied emotions so effectively. One should not take a simplistic view ; and, be deceived by unrealistic suppositions; pain is ever a pain

But, their views did not find favor with the scholars of the Alamkara School ; and, it was eventually, overshadowed by the writings of the stalwarts like Abhinavagupta, Anandavardhana, Mammata, Hemachandra , Visvanatha and Jagannatha Pandita.]

Let’s talk a little more about rasa.

9. Rasa–roughly translated as artistic enjoyment or emotive aesthetics –is one of the most important concepts in classical Indian aesthetics, having pervasive influence in theories of painting, sculpture, dance, poetry and drama. It is hard to find a corresponding term in the English language. In its aesthetic employment, the word rasa has been translated as mood, emotional tone, or sentiment or more literally, as flavour, taste, or juice.

The chapters VI and VII in Bharata’s Natyasastra have been the mainstay of the Rasa concept in all traditional literature, dance and theater arts in India. Bharata says that which can be relished (āsvādana, rasanā) – like the taste of food – is Rasa –Rasyate anena iti rasaha (asvadayatva) .Though the term is associated with palate, it is equally well applicable to the delight afforded by all forms of art; and the pleasure that people derive from their art experience. It is literally the activity of savoring an emotion in its full flavor. The term might also be taken to mean the essence of human feelings.

If Rasa is that which can be tasted or enjoyed; then Rasika is the connoisseur.

The Chitrasutra of the Vishnudharmottara purana says,” Anything be it beautiful or ugly, dignified or despicable, dreadful or of a pleasing appearance, deep or deformed, object or non-object, whatever it be, could be transformed in to rasa by poets’ imagination and skill ”

10. Bharata, initially, names four Rasas (Srngara, Raudra, Vira and Bhibhatsa) as primary; and, the other four as being dependent upon them . That is to say that the primary Rasas, which represent the dominant mental states of humans, are the cause or the source for the production of the other four Rasas.

Bharata pairs each of these principal Rasas with a specific subsidiary: Sṛṅgāra with Hāsya; Raudra with Karuṇa (pathos); Vīra with Adbhuta (wonder); and, Bībhatsa with Bhayānaka (terror).

Bharata explains that Hasya (mirth) arises from Srngara (delightful) ; Karuna (pathos) from Raudra (furious); Adbhuta (wonder or marvel) from the Vira (heroic); and, Bhayanaka (fearsome or terrible) from Bhibhatsa (odious).

śṛṅgārādhi bhaved hāsyo raudrā cca karuṇo rasaḥ vīrā ccaivā adbhuto utpattir bībhatsā cca bhayānakaḥ ॥ 6.39॥

It is explained; each of these pairs exemplifies a different mode of ‘causation’ that may, in reality, be generalized to all our emotions.

Hāsya would be the natural result of the ‘semblance’ (ābhāsa) of any emotion; Karuṇa exemplifies those evoked by the real-life consequences of the same actions that evoke the principal emotion (destructive anger); Adbhuta typifies the class of those directly evoked in onlookers by the very actions that evoke the primary Rasa (admiring the exemplary feats accomplished against all odds, instead of simply identifying ourselves with the hero); and Bhayānaka the possibility of two different emotions being occasioned by the same cause.

***

The publication of Abhinavabharati brought in to focus and opened up a whole new debate on Bharata’s theories on Rasa the aesthetic experience.

But, Abhinavagupta in his Abhinavadharati does not entirely agree with Bharata. He accepts that each Rasa , in its own manner provides pleasure to the spectators. But, he wonders , how could the basic four Rasas give raise to the other four. The Rasa that mimics (anukrti) the original could, at best, might be a semblance; but, it cannot be the same as the original. Further, he remarks, it is hard to believe that Raudra (ferocious) would cause a sense of Karuna (pity or compassion) in the heart of the spectator. Actually, he says, when the spectator is witnessing Raudra, he is enjoying the fury and ferocious aspect of the action.

Abhinava did however accept the eight Rasas identified Bharata as corresponding to fundamental human feelings, such as : delight, laughter, sorrow, anger, energy, fear, disgust, heroism, and astonishment. These Rasas comprise the components of aesthetic experience. A Rasa , thus , denotes an essential mental state or the primary feeling that is evoked in the person who reads or listens or views a work of art.

srungāra hāsya karuna–raudra vīra bhayānakah Bibhatsā adbhuta sangjñaucetyastau nātye rasāh smrutāh //NS.6.15//

Abhinavagupta interpreted Rasa as a “stream of consciousness”. He then went on to expand the scope and content of the Rasa spectrum by adding the ninth Rasa: and, establishing the Shantha rasa, the Rasa of tranquility and peace.

[ It needs to be mentioned, here, that Abhinavagupta was not the first to speculate on the Shantha-rasa. For instance; much earlier to his time, Udbhata (8th-9th century), another scholar from Kashmir, in his Kavya-alankara-vivrti was said to have introduced Shantha Rasa. After prolonged debates, spread over several texts across two centuries, Shantha was accepted as an addition to the original eight Rasas.

There is an interesting sidelight:

According to Dr. VM Kulkarni (Some Unconventional Views on Rasa), the Anu-yoga-dvara-sutra (Ca.3rd century), one of the sacred texts of the Svetambara Jains ( as also one of the oldest canonical literature on mathematics) , lists nine types of Kavya-rasas, as : Vira, Srngara, Adbhuta, Raudra, Vridanaka, Bhibhatsa, Hasya, Karuna and Prashantha .

The enumeration of the Rasas, as also the explanations offered thereon by the Anu-yoga-dvara-sutra, in many ways, differ from those in Bharata’s Natyashastra. Here, not only the sequence in listing of Rasas is altered; but also, it excludes the Bhayanaka-rasa, which is replaced by Vridanaka –rasa. Further it, extends Bharata’s list by adding Prashantha (same as Shantha) as the ninth Rasa.

Hemachandra Suri (late 11th century) , another Jain scholar and author of Kavya-anushasana, a work on poetics, explains that Vira , here, is the first , the best and the noblest of all Rasas , as it stands for Tyga-vira ( magnanimity in renunciation ) and Tapo-vira ( excellence in austerities) , which are much superior to Yuddha-vira ( heroics in a battle), which basically is cruelty , causing injury to others (paropaghata).

The Vridanaka rasa (modesty) whose Sthayi-bhava is Vrida or Lajja ( shyness, bashfulness ) is illustrated by the love and reverence that aged parents show towards the newly wedded bride who steps into their home , which causes a sense of shyness and gratefulness in the heart of the bride.

The Anu-yoga-dvara-sutra (3rd century or earlier), which pre-dates Abhinavaguta (11th century) by several centuries, is perhaps the earliest text that recognizes Prashantha (Shantha) as a Rasa ; and , lists it as the ninth Rasa. Prashantha is described , here, as a Rasa characterized by Sama (tranquility) which arises from composure of the mind divested of all Vikaras (aberrations or passions) . As an illustration of Prashantha , it cites the lotus-like glowing face of a Jina , adorned with calm eyes, gentle smile, unaffected by passions like anger, attachment, fear etc.

It is very unlikely that either Udbhata or Abhinavagupta had come across the third century Jaina-text Anu-yoga-dvara-sutra ; and its explanations of Shantha-rasa .]

*

Abhinava explained that Shantha Rasa underlies all the other mundane Rasas as their common denominator (Sthayin). Shantha Rasa is a state where the mind is at rest, in a state of tranquility. The other Bhavas are more transitory (sancharin) in character than is Shanta rasa. For instance ; one cannot be either angry , amorous, fearsome or humorous all the time . Those are the moods or the responses to varying situations (Sanchari ). The mental states, Rati etc., do change. But, Shanta , the undisturbed tranquility is your basic state; and , it is a permanent state – Nitya Prakrti. It is from Shanta all the other Rasas emanate ; and , it is into Shanta they all resolve back. Shanta Rasa is the ultimate Rasa , the summum bonum.

Abhinava considered Shantha Rasa (peace, tranquility) – where there is no duality of sorrow or happiness; or of hatred or envy; and, where there is equanimity towards all beings – as being not merely an additional Rasa; but, as the highest virtue of all Rasas. It is one attribute, he said, that permeates all else; and, in to which everything else moves back to reside (hridaya_vishranthi).

na yatra duḥkhaṃ na sukhaṃ na dveṣo nāpi matsaraḥ । samaḥ sarveṣu bhūteṣu sa śāntaḥ prathito rasaḥ ॥

Following Abhinavagupta, the theory of Nine-Rasas, the Navarasa, became universally acceptable in all branches of Indian aesthetics. And, shantha rasa has come to be regarded as the Rasa of Rasas. Even Ramachandra and Gunachandra (authors of Natya-Darpana) accepted Shantha as the ninth Rasa; but, remarked that there could be more number of Rasas than mere nine . They pointed out that emotional states such as Sukha, Dukkha, Sneha , Laulya etc., could also be treated as Rasas. Likewise; Rudrata added Preyas (with Sneha as the dominant state) ; Raja Bhoja added Vatsalya; others added Bhakthi; and, Visvesvara added Maya (with mithya-jnana as the dominant state). Thus, in a way of speaking, Rasas are virtually countless.

However, the question whether Shanta Rasa is fit for stage; and, whether a Sthayi-bhava, Anubhava, Sanchari and Sattvika can be aligned to Shanta Rasa is a subject of endless debate since the eighth century. Some , particularly Dhananjaya (DR.4.35) and Dhanika, argued that Shanta Rasa can occur in kavya ; but , it cannot occur in Nataka, as it is not possible to enact it on stage. They even crticized inclusion of Sama among the Sthayibhavas . It was pointed out that it is impossible to enact Shama which is complete stoppage of all action; and, in fact ,it has no connection with acting . They , therefore, claimed that Shanta Rasa is not fit to be depicted in drama.

As against that, Abhinavagupta and others of his School argued strongly and rejected such objections.

They pointed out that if other Sthayins can be presented as Rasa, then Sama ( equanimity) and desire for tattva-jnana (philosophical knowledge) can also be turned into Rasa.

And, as if to rebut the objections raised by Dhananjaya and others , Mammata ( 12thcentury), a follower of Abhinavagupta, in his Kavyaprakasha , describing the characteristics of the Shanta Rasa , states : Shantha-rasa is to be known from that which arises from the desire to attain liberation, which leads to the knowledge of the Truth ; and Truth is just another name for knowledge of the ever blissful Self (Atma-jnana), the highest happiness. The realization that Truth alone is the means to attain liberation (mokṣha-pravartakaḥa) is the Sthayi-bhava of Shantha. Its nature is different from that of other Sthayi-bhavas, like Rati etc., which are transitory, as they arise and disappear from time to time.

The virtues such as Nirveda (dispassion), Tattva-jnana (philosophical knowledge) and Vairagya (renunciation) are its Vibhavas. Its Anubhavas (manifestations) are the practices of Yama (self-control), Niyama (self-regulation), Adyathma (spiritual outlook), Dhyana (meditation), and Dharana (rooted in the self). And , its Sanchari Bhavas (passing moods) are Nirveda (world-weariness), Smrti (awareness), Dhriti (steadfast), unperturbed ( no romancha) ; and, Sthamba (unwavering mind).

[ Nirveda can be both sthayi-bhava and vyabhichari-bhava. When it is born of tatvajnana, it is permanent; and , is the sthayibhava of Shanta-rasa. Otherwise, it is only a vyabhichari-bhava.]

Further, they pointed out and argued, if Shanta can be portrayed in poetry, why not in Drama , which is also a form of poetry (Drishya Kavya). A virtuoso, an expert actor, can create any Sthayi and present any delectable Rasa. And, therefore, the Shanta rasa can also be enjoyed as an aesthetic experience by the spectators in a drama. If it is said that Shanta cannot be enjoyed by all, then the other Rasa such a Roudra , Bhibathsa and Bhayanaka cannot also be enjoyed by all. We cannot deny Shanta just because it is not portrayed more often. In the plays depicting the lives of saints who try to attain self-realization or liberation (Moksha) as also the lives of other noble persons ( say, like the hero in the play Nagananda), the Shanta Rasa should be the dominant Rasa. The other instance of such successful presentation is the role of Buddha in the dramas. Similar is the case with the Natakas like Prabodhachandrodaya and Sankalpasuryodaya .

Abinavagupta also said that the philosophical outlook and knowledge (Tattva-jnana) and the desire or liberation (mumukshatva) is the means to liberation (Mokska). When such intense desire for Atma-jnana (realization of the self) is presented as the hero’s object of attainment (phala-yoga) ), the Shanta has to be most suitable Rasa.

Further, Abhinavagupta mentioned Bhakti as an important component of the Shantha Rasa. Following which, the later poetic traditions reckoned Bhakthi (devotion) and Vathsalya (affection) as being among the Navarasa. The magnificent Epic Srimad Bhagavatha was hailed as the classic example of portrayal of Bhakthi, Vathsalya, and Shantha rasas. The poets and the divine inspired singers, notably after 11th century, provided a tremendous impetus to the Bhakthi movement.

11. Rasa is conveyed to the enjoyer– the Rasika or Sahrudaya – through words, music, colors, forms, bodily expressions, gestures etc. These modes of expressions are called Bhavas. For example, in order for the audience to experience Srngara (the erotic rasa), the playwright, actors and musician work together employing appropriate words, music, gestures and props to produce the Bhava called Rati (love).

The term Bhava means both existence and a mental state; and, in aesthetic contexts it has been variously translated as feelings, psychological states, and emotions. In the context of the drama, they are the emotions represented in the performance.

According to Bharata, the playwright experiences a certain emotion, which then is expressed on the stage by the performers through words, music, gestures and actions. The portrayal of emotions is termed bhavas. Rasa, in contrast, is the emotional response that is inspired in the spectator. Rasa , thus, is an aesthetically transformed emotional state experienced, with enjoyment, by the spectator.

Bharata accepted Rasa as the essence of a dramatic production; and it is the ultimate test of its success. And, in the Sixth Chapter of Natyashastra, he states that While the Rasas are created by Bhavas, the Bhavas by themselves carry no meaning in the absence of Rasa . It is from the combinations of Bhavas that the Rasa emerges; and, not the other way. In the prose-passage following the verse thirty-one of Chapter six , Bharata commences his exposition of Rasa , saying : I shall first explain Rasa; and, no sense or meaning proceeds without Rasa (Na hi rasa-adrate kaschid-arthah pravartate). The forms and manifestations of the Bhavas are defined by the Rasa.

12. Abhinavagupta argues that a play could be a judicious mix of several rasas, but should be dominated by one single rasa that defines the tone and texture of the play. He cites Nagananda of Sri Harsha and explains though the play had to deal with the horrific killing of the hapless Nagas; it underplays scenes of violence, and radiates the message of peaceful coexistence and compassion. It is that aesthetic experience of peace and compassion towards the fellow beings that the spectator carries home.

Similarly, Abhinava explains, a character in the play might display several Bhavas ; but, its inner core or essence is meant to convey a single dominant Rasa. He also says there is one main Rasa (Maha rasa) in which other Rasas appear as shades.

[Dhananjaya , in his Dasarupaka said : A Nataka should comprise one Rasa-either Srngara or Vira; and in conclusion the Adbhuta becomes prominent

Eko rasa – angi -kartavyo virah srigara eva va / angamanye rasah sarve kuryannivahane -adbhutam

But, Abhinava , does not mention any such restrictions.]

The varying Anubhavas – the modes of expressions, the facial and bodily gestures; the passing moods (Sancharin), as also involuntary reflexes ( sattvika) – would be colored or delineated by the enduring Bhava (Sthayin) relating to the intended dominant the Rasa that is meant to be conveyed to the spectator (prekshaka) .

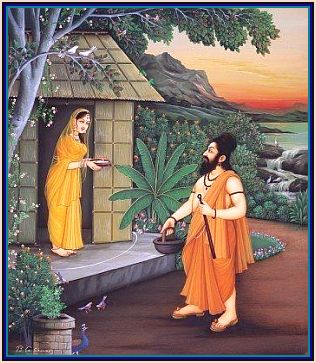

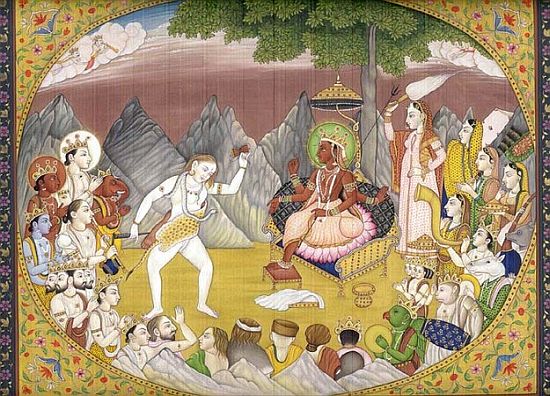

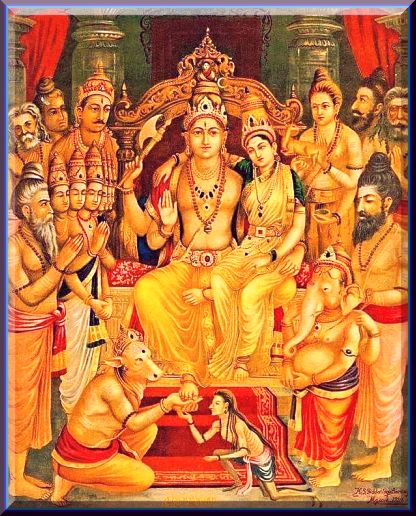

For instance, Rama is regarded the personification of grace, dignity, courage and valor. He projects a sense of peace and nobility . That does not mean Rama should perpetually be looking dull and stiff like a starched scarf. He too has his moments of humor, anger, frustration, rage, helplessness, sorrow, dejection and even boredom. The modes of expression of those emotions (Anubhava and sanchari bhavas) through his gesture and words are meant to contribute to the overall Sthayi-bhava that Rama conveys , leading to the Shantha Rasa. Therefore , his smile is gentle and beatific, his laugh is like peels of temple bells, his love is graceful , he does not lose composure while in sorrow , his anger is like a white-hot flame with no smoke of haltered, and his treatment of the enemy is dignified and has an undercurrent of compassion.

While in the portrayal of Ravana, the smile is sardonic, the laughter is bellowing and thunderous , the expressions of love are heavily tinted with greed and passion, his anger is grotesque and full of hate, his treatment of his followers is laced with contempt , he is intolerant of any dissent and shows no mercy to the vanquished. Raudra, the fearsome aspect is conveyed through the combination of the Anubhavas , the sanchari bhavas and the sattvika , that are appropriate to his character

The gestures ( Anubhavas and Sanchari Bhavas, as also Sattvika ) – smile, laughter, love, anger and other reflex action etc., – in either case are the similar; but, the manner they are enacted, the personality they radiate and the character they help to portray are different. But all such bhavas , combining into a Sthayi Bhava, contribute to conveying the intended Rasa.

[ In this context , he talks about the relation between the Bhava and the Rasa. He says : when Rati (love) is expressed towards god , then the suggested mood (Bhava) is called Bhakthi . Similar is the case with regard to love shown towards muni (sage) , guru (teacher), nrupa (king), putra (son) etc. When that love is suggested or expressed towards a beloved (kantha), it is termed as Srngara- rasa –

(Rati-devadi vishaya vyabhichari tathanjitha Bhavah proktaha / yadi sabdan muni-Guru-nrupa-putradi vishayaha , kantha vishayasthu vyakta Srungaraha )

Then he talks about misplaced or inappropriate (anauchitya) expressions such the Bhavas leading to aberration or their improper manifestations : Rasa-Abhaasa or Bhava Abhaasa .

For instance ; Rati or Srngara towards another man’s wife (upanayika) – Ravana; Hasya , humor or fun or ridicule directed against a Guru ; Raudra or Vira , anger, against one’s own parents ; and, projecting Bhayanaka or horror in a noble hero like Rama – are all considered as Abhaasa , aberrations..

Tad abhasa anuchitya pravarthitaha / tadbhasa rasa-abhasa, bhava-abhasa uctyate/ ]

Dhanajaya , therefore , says that when Sthayin is brought out by means of authentic Vibhava, Anubhava, Sattvika and Vyabhicharin ; the resultant produce is enjoyed by the spectator; and, it is then Rasa.

It is therefore said, Bhava is that which becomes (bhoo, bhav, i.e., to become); and Bhava becomes Rasa. And, it is not the other way. Rasa is the essence of art that is conveyed.

13. Abhinava makes a distinction between the world of drama (Nātyadharmī) and the real but ordinary life (Lokadharmī). In the artistic process, where presentations are made with the aid of various kinds of dramatic features such as Abhinayas and synthetic creations , we are moving from the gross and un-stylized movements of daily life to more subtle forms of expressions and experiences; we move from individualized experiences to general representations (sadharani-karana); and from multiplicity to unity (aneka-eka).

Among the primary emotions, anger (krodha), sorrow (śhoka), disgust (jigupsā), and fear (bhaya) are painful; whereas , love (rati), enthusiasm (utsāha), surprise (vismaya), and laughter (hāsa) are pleasant.

Abhinava analyzes each in turn to demonstrate how the pleasurable emotions necessarily contain elements of pain and vice-versa

He says that the feeling that might cause pain in real life is capable of providing pleasure in an art form. He explains, while viewing a performance on stage one might appreciate and enjoy the display of sorrow, separation, cruelty, violence and even the grotesque; and one may even relish it as aesthetic experience. But, in real life no one would like to be associated with such experiences.

[ Natyadarpana of the Jain scholars Ramachandra and Gunachandra (12th century), however, refute Abhinavagupta’s position that all Rasas are always pleasurable (Ananadatmaka). They, instead, point out that each Rasa, in its wake, brings its own pleasure and pain as well (sukha-dukkha-atmaka). They call attention to the fact that the four Rasas –Karuna, Raudra, Bhayanaka and Bhibhatsa – do cause indescribable pain to the Sahrudayas; and, those gentlefolk simply shudder when they are made to watch horrific scenes, such as the abduction of Sita or the disrobing of Draupadi in an open court.

Similar views were expressed by Siddhichandra in his Kavya-prakasha-khandana.]

According to Abhinavagupta, a true connoisseur of arts has to learn to detach the work of art from its surroundings and happenings; and view it independently (svātantrya) .

He asserts, the “willful suspension of disbelief” (Artha-kriyākāritva) is a pre-requisite for a receptive spectator to enjoy any art expression. The moment one starts questioning it or doubting it and looking at it objectively; the experience loses its aesthetic charm; and, it becomes same as a mundane object.

One enjoys a play only when one can identify the character as character from the drama and not as ones friend or associate. The spectator should also learn to disassociate the actor from the character he portrays.

The Hero and Heroine in a play are just portraying the roles assigned to them, as best as they can. In other words; they are trying to convey certain states of emotions and the sate of being of the character-roles they are playing . They are like a pot (patra) or receptacle, which carries the emotional state of primary (real) role to the spectator. The actor merely serves as a vessel or a receptacle or a means of serving relish (Asvadana) ; and, that is the reason, a role is called a Patra.

The characters on the stage represent the real role ; but , are not the real ones; and, they do not completely identify themselves with the original. Hence, the Vibhava is like a cause; but, not an exact cause. The performance, the acting by the hero, heroine and other characters in a play is Anubhava, one of the several ways of bringing out the emotional states of the characters they are playing out on the stage. Such Anubhava could be called as ensuing responses.

The hero or heroines in a play don’t become the lover and beloved in real life. They understand and accept here, what their their roles are; and, try to show what might be the emotional experiences of the character , and its reactions to the given situation . The actors try to resemble the character , for few hours of the play ; and, act on the stage accordingly, through which the spectators understand , grasp and enjoy the emotional states in the play. The act of the lovers on stage is essentially a ‘third person’ experience

While our hearts resonate (hṛdaya-spanda) with the presentations of the dramatis personae, our focus is centered on understanding (tanmayī-bhavana) the interactions going on the stage . Abhinavagupta observes that the theatrical experience is quite unlike the experience in the mundane and the real world; it is Alaukika – out of the world.

In summary; he draws a theory that the artistic creation is the expression of a feeling that is freed from localized distinctions; it is the generalization (sadharanikarana) of a particular feeling. It comes into being through the creative genius (prathibha) of the artist. It finally bears fruit in the spectator who derives Ananda, the joy of aesthetic experience. That, he says, is Rasa – the ultimate emotional experience created in the heart of the Sahrudaya.

He illustrates his position through the analogy of a tree and its fruit. Here, the play is the tree; performance is the flower; and spectator’s experience .

Rasa, the relish (Asvada) by the spectator, is the ultimate product (phala) of a dramatic performance, as that of a fruit borne by a tree : “the play is born in the heart of the poet; it flowers as it were in the actor; and, it bears fruit in the delight (ananda) experienced by the spectator.” .. ”And, if the artist or poet has inner force of creative intuition (prathibha)…that should elevate the spectator to blissful state of pure joy Ananda.”

According to Abhinavagupta, the object of the entire exercise is to provide pure joy to the spectator. Without his participation all art expressions are pointless.

Thus, he brought the spectator from the edge of the stage into the very heart of the dramatic performance and its experience.

14. There is a very interesting discussion about the progression in the development of a character, from the playwright’s desk (or even prior) to the theatrical stage. . Abhinava discusses the arguments, in this regard, of his predecessors (such as Sankuka, Lollota, and Bhattanayaka) and then puts forth his own views.

Let’s, for instance, take a character from history or mythology (say, Rama). No one, really, was privy to the mental process of that person. Yet, the playwright tries to grasp the essence of the character; and, strives to give a concrete form to the abstract idea of Rama, in his own way. The director, the sutradara, tries to interpret the spirit and substance of the play, and the intentions of the playwright, as he understands it. The actor in turn absorbs the inputs provided by both the playwright and the director. In addition, the actor brings in his own creative genius, skill, his experience on the stage, and his own understanding of the character in order to recreate the “idea” of Rama. All the while, the actor is also aware that he is just an actor on stage trying to portray a character.

The actor’s emotional experience while enacting the character might possibly be similar to what the playwright and /or the director had visualized; but it certainly would not be identical.

The actor as a true connoisseur and a skilled performer has an identity of his own; he does not merely imitate (anukarana) the character as if he were its mold (paratikrirti); but, he projects the possible responses of the character (anukirtana) to the situations depicted in the play-text (paatya), in his own way, through the portals of the character’s stated disposition (bhava) and its essential nature (svabhava) , as he has understands it (aropita-svarupa).

What is presented on stage is the amalgam, in varying proportions, of experiences and impressions derived from diverse sources. The actor’s inspiration finds its roots in several soils. His performance on stage, thus, resembles the mythical inverted tree, with its roots in the sky and its branches spreading down towards the earth. Its roots are invisible. But, its branches and leaves spreading down in vivid forms are very alive; and, the fruits they bear are within our experience.

We see the actors on the stage; and applaud their performance. But, the whole of the dramatic production and display is the fruit (siddhi, phala) of the collective participation of all those involved with it; and, bringing it to us alive. They are like the extensions of the roots, branches, and leaves. The actors on the stage are like the, flowers and fruits, ever green, tender and fresh, inviting us to partake and enjoy. What is witnessed is the fulfillment or the fruits of the dedication and efforts of many – seen and unseen.

In so far as the spectator is concerned, he, of course, would not be aware of the contributions of either the playwright or the director or the supporting technicians; or even of the mental process of the actor in producing the artistic creation. His experience is derived, entirely, from the performance presented on the stage.

Further, there is absolutely no way an actor or a spectator could feel and experience in exactly the same way as the “original “- on whom the character was modeled. The spectator does not obviously receive the original; instead he infers from the forms of created artistic-imitations of the original presented on the stage, sieved through the combined efforts and experiences of the playwright, the director and the actor.

Abhinava remarks, the question whether the idea of the character as received by the spectator through the performance on the stage , was identical to its “original “ historical personage, is not quite relevant. What matters, he says, is the emotional experience (rasa) inspired in the shahrudaya the goodhearted – cultured spectator. How did it impact him? That, in fact, is the essence and fulfilment of any art.

Another illustration discussed in this context is that of Chitra_turaga, a pictorial horse. Abhinava said he got it from his predecessor Sri Sankuka . He had said: about a painted horse we can say that it is a horse and it is not a horse; and, from the aesthetic point of view, it is real and unreal. Thus , a painting of a horse is not a horse; but, it is an idea or the representation of a horse. One doesn’t mistake the painting for the horse. The artistic creation though not real can arouse in the mind of the spectator, the experience of the original object. Art cannot reproduce all the qualities of the original subject. The process of artistic creation is, therefore, inferential and indirect; rather than direct perception.

Mammata, a eleventh century Kashmiri aesthete, endorsed Abhinava’s views by stressing that the object in art is a virtual and not physical.

Bhattauta, another scholar from Kashmir, in his treatise called Kavya Kautuka, alo says that a dramatic presentation is not a mere physical occurrence. In witnessing a play we forget the actual perpetual experience of the individuals on the stage. The past impressions, memories, associations etc. become connected with the present experience. As a result, a new experience is created and this provides new types of pleasure and pains. This is technically known as ‘Aesthetic rapture’ (camatkāra) – rasvadana, camatkara, carvana.

Anandvardhan extended the scope of Rasa to literature. He combines Rasa with his Dhvani theory. According to him, Dhvani is the technique of expression; and, Rasa stands for the ultimate enjoyment of poetry or drama. Suggestion (Dhvani) in abstraction does not have any relevance in an art. The suggested meaning has to be charming and it is the Rasa element which is the ultimate source of charm in drama and poetry.

A very attractive form of ‘suggestion’ (Dhvani) is said to be when the poem is dramatized (Nāṭyāyita) by the creative imagination (bhāvakatva) so that all the signifying elements of sound, syntax, rhythm, rhyme, intonation, context and composite sense come alive and converge on the evocation of Rasa as the primary meaning (Mukhyā-artha).

According to Abhinavagupta a real work of art, in addition to possessing emotive charge carries a strong sense of suggestion and the potential to produce various meanings. It can communicate through suggestions and evoke layers of meanings and emotions.

Mammaṭa says the simple statement “the sun sets,” can, in real life, suggest a virtually unlimited number of meanings to different listeners.

*

Abhinavgupta talks about Sadharanikarana, the generalization. He points out that while enjoying the aesthetic experience, the mind of the spectator is liberated from the obstacles caused by the ego and other disturbances. Thus transported from the limited to the realm of the general and universal, we are capable of experiencing Nirvada, or blissfulness. In such aesthetic process, we are transported to a trans-personal level. This is a process of de-individual or universalization – the Sadharanikarana.

[Anandavardhana says, the sorrow (soka) of the First Poet, which arose out of the separation of the couple of the krauncha birds, took the form of a verse (sloka).

Kavyasyatma sa evarthas tatha cadikaveh pura/ Kraunca dvandva viyogottha sokah slokatvamagatah (Dhyanyaloka.1.5)

Abhinavgupta explains; the soka which took the form of sloka is the sthayibhava of karunarasa that was experienced by the Adi Kavi Valmiki. And, that sorrow is not to be taken merely as the personal sorrow of the sage-poet (na tu muneh soka iti mantavyam ); but , it belongs to the muni and the bird alike; and, indeed, it is also the generalized (sadharinikarana) or the universal form of sorrow that is experienced and relished by the aesthetes (sahrudaya) of all the generations.]

A true aesthetic object, Abhinava declares, not merely stimulates the senses but also ignites the imagination of the viewer. With that, the spectator is transported to a world of his own creation. That experience sets the individual free from the confines of place, time and ego (self); and elevates him to the level of universal experience. It is liberating experience. Thus art is not mundane; it is Alaukika in its nature.

Please also read Bharata’s Natyasastra -some reflections

References:

Bharata: The Natyasastra by Kapila Vatsayan

Introduction to Bharata’s Natyasastra by Adya Rangacharya

A glimpse into Abhinavagupta’s ideas on aesthetics by Geetika Kaw Kher

https://www.academia.edu/24993006/Abhinavagupta?email_work_card=interaction_paper

ALL PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET

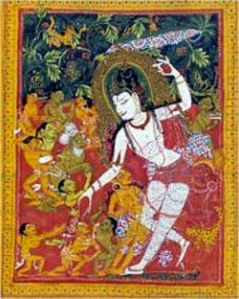

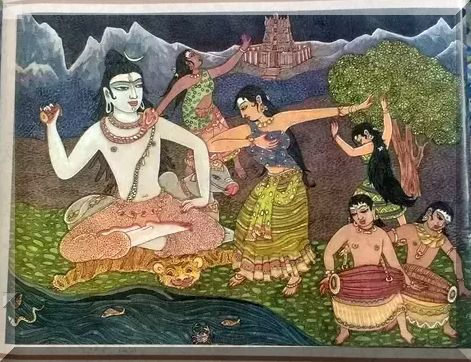

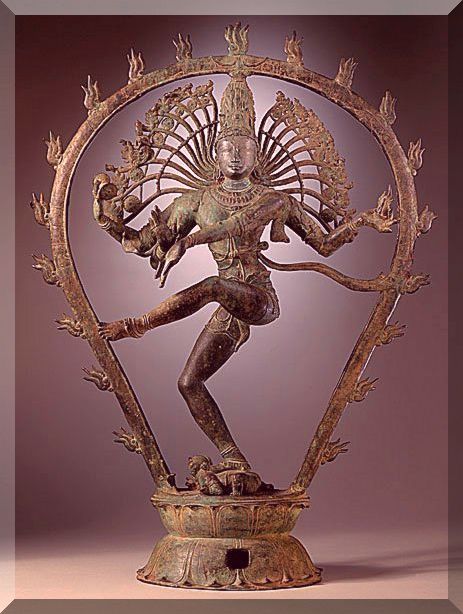

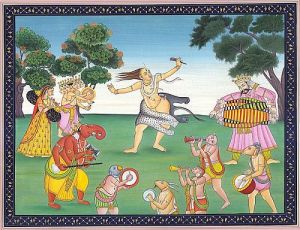

Abhinavagupta, in his typical style, provides a totally different sort of explanation to the term Tandava. According to him, the term Tāṇḍava is derived from the sounds like ‘Tando; tam-tam’, produced by the accompanying Damaru shaped drums. It follows the manner, in Grammar (vyākaraṇa), of naming an object, based on the sound it produces – śabda-anukṛti.

Abhinavagupta, in his typical style, provides a totally different sort of explanation to the term Tandava. According to him, the term Tāṇḍava is derived from the sounds like ‘Tando; tam-tam’, produced by the accompanying Damaru shaped drums. It follows the manner, in Grammar (vyākaraṇa), of naming an object, based on the sound it produces – śabda-anukṛti.