Grammar

Grammar (Vyakarana) was recognized in India, even from the earliest times, as a distinct science; a field of study with its own parameters, which distinguished it from other branches of learning / persuasions. That was because, it was beleived, Grammar helps to safeguard the correct transmission of the scriptural knowledge; and , to assist the aspirant in comprehending the true message of the revealed texts (Sruti). And, therefore Vyakarana was regarded as the means to secure release from the bondage of ignorance, cluttered or muddled thinking.

The term Vyakarana is defined as vyakriyate anena iti vyakarana: Grammar is that which enables us to form and examine words and sentences.

Prof. Rama Nath Sharma summarizes the traditional view of Grammar

: – Grammar is a set of rules formulated based upon generalizations abstracted from usage.

: – The Astadhyayi accepts the language of the Sista as the norm for usage.

: – The function of Grammar is to account for the utterances of a language in such a way that fewer rules are employed to characterize the infinite number of utterances.

: – The Astadhyayi accounts for the utterances of the language by first abstracting sentences and then by conceptualizing the components of these sentences as consisting of bases and affixes.

**

In the linguistic traditions of ancient India, Vyakarana, also known as Vag-yoga; Sabda-yoga; or Sabdapurva-yoga; Pada-Shastra (the science of words) which treats the word as the basic unit (Shabda-anushasanam) occupied a preeminent position. It was/is regarded as one of the most important Vedanga (disciplines or branches of knowledge, which are designed to preserve the Vedas in their purity) – pradanam cha satsva agreshu Vyakaranam.

[But, at the same time, there existed a parallel system of linguistic analysis- Nighatu, Nirvachana shastra or Nirukta and Pratishakyas (considered to be the earliest formulations of Sanskrit grammar) – which served a different purpose.]

The primary object of Vyakarana, in that context, was to study the structure of the Vedic language in order to preserve its purity; its correct usage (sadhutva); and, to ensure its longevity (nitya). Panini asserted that the Grammar should be studied in order to preserve the Vedas in their pristine form (rakshatam Vedanam adhyeyam vyakaranam).

Later, Bhartrhari (Ca. 450-510 C.E) also asserted that the role of Vyakarana (Grammar) is very important; in safeguarding the correct transmission of the scriptural knowledge, and in assisting the aspirant in grasping the truth of the revealed knowledge (Sruti).

Bhartrhari compared Grammar to the medical science; and, said that just as the medicines remove the impurities of the body, so does Grammar removes the impurities of speech (chikitsitam van-malaanam) and of the mind. Bhartrhari who inherited the traditional attitude towards Grammar, regarded it as the holiest branch of learning; and, elevated Grammar to the status of Agama and Sruti, leading the way to liberation (dvāram apavargasya). He believed the use of correct forms of language enables one to think clearly; and, makes it possible to gain philosophic wisdom or to pursue other branches of valid knowledge.

Tad dvāram apavargasya vāṅmalānāṃ cikitsitam / pavitraṃ sarva-vidyānām adhividyaṃ prakāśate – BVaky. 1.14

Prajñā- vivekaṃ labhate-bhinnair-āgama-darśanaiḥ / kiyad vā śakyam unnetuṃ svatarkam anudhāvatā- BVaky. 2.489

Sādhutva jñāna viṭayā seyaṃ vyākaraṇa-smṛtiḥ / avicchedena śiṣṭānām idaṃ smṛti –nibandhanam – BVaky. 1.158

*

Thus, the study of Grammar, which facilitates our understanding of the nature of words, meanings and the relationship between them and their variances, enables us to construct correct sentences by use of appropriate words in order to precisely convey the intended meaning.

Therefore, the philosophy of language, in varied traditions, have always taken an important position in Indian thought. It was said: “the foremost among the learned are the Grammarians, because Grammar lies at the root of all learning” (prathame hi vidvamso vaiyyakarabah, vyakarana mulatvat sarva vidyanam – Anandavardhana)

Schools of Grammar prior to Panini

The origin of Grammar cannot, of course, be pinpointed. Yaska and Panini are the two known great writers of the earliest times whose works have come down to us. They were perhaps before fifth century BCE; and, Yaska is generally considered to be earlier to Panini. Yaska’s work Nirukta is classified as etymology; and Panini’s work Astadhyayi as Grammar (Vyakarana).

Though Panini is recognized as the earliest known Grammarian, it is evident that he was preceded by a long line of distinguished Grammarians. There, surely, were many treatises on Grammar and Etymology; but now, all of those are lost forever. And, Panini refers to a number of Grammarians previous to his time. But, very little is known about those ancient Masters.

It is reasonable to acknowledge that Panini inherited a rich and vibrant tradition of Sanskrit Grammar. And, it was on the basis of the works of his predecessors that Panini could develop a grand system that is now universally accepted; and, hailed as the perfect and profound exposition of linguistic science. But, one cannot say, with certainty, to what extent Panini was indebted to each of his predecessors.

Regardless of how much or how little Panini derived his work from earlier sources, his Astadhyayi is indeed a remarkable work.

*

Hartmut Scharfe, in his Grammatical Literature (Otto Harrassowitz, 1977), writing about Panini, says (at page 108):

Panini, and with him, the later Grammarians, who contributed to the science of Grammar before him, owe their greatness to a combination of fundamental discoveries:

- The insight that the proper object of Grammar is the spoken language; not its written presentation

- The theory of substitution

- The analysis in root and suffix

- The recognition of ablaut correspondence

- The formal description of language as against a ‘logical’ characterization; and

- The concise formulation through the use of a metalanguage

**

It is often said: the transparent nature of Sanskrit made the analysis possible. But, we can argue as well that it was first Panini’s (and his predecessors’) analysis , which made the structure so transparent : was the relationship of Dohmi and Adhuksat , or Majjati and Madgu really obvious ?

The history of Sanskrit grammar is generally classified into three broad segments: the Grammars that were in use prior to the time of Panini (Pre-Panian) – Pracheena-vyakarana; the Grammars that follow the system devised by Panini (Panian); and, those Grammars whose systems and methods vary from that of Panini (Non- Panian) or Navya-vyakarana – post Panini.

Later age Grammarians recognize the eight Grammarians of merit, Vyakarana-shastra-pravartakas:

Indra (इन्द्रः), Chandra (चन्द्रः), Kasha (काशः), Krtsnapishali (कृत्स्नापिशली), Shakatayana (शाकटायनः), Panini (पाणिनिः), Amarajainendra (अमरजैनेन्द्रः), Jayanti (जयन्तिः) are the eight Masters of Shabda (word) or Grammar

इन्द्रश्चन्द्रः काशकृत्स्नापिशली शाकटायनः । पाणिन्यमरजैनेन्द्राः जयन्त्यष्टौ च शाब्दिकाः

*

Among all the traditional systems of Grammar (compiled by Indra, Chandra, Kasakritsna, Kumara, Sakatayana, Sarasvati Anubhuti Svarupa acharya, Apisali and Panini), it is only the system of Panini that is acknowledged as being complete, comprehensive and thoroughly logical; and, that which has survived to this day, in its entirety.

And, therefore, whatever be the type or the School of Sanskrit Grammar that is discussed, it, invariably, is carried out with reference to the classic tradition promulgated by Panini; and, enriched by three celebrated works : Astadhyayi (of Panini); Vrttikas (of Katyayana) ; and, Mahabhashya (of Patanjali). The three authors, the Trinity (Muni traya), are revered as the Sages of Sanskrit Grammar.

The system devised by Panini is, therefore, looked upon as a Great Science (Paniniyam-Mahashastram) concerning words : Paniniyam-mahashastram-pada-sadhu-yukta – lakshanam) ; and, is always at the centre of vast and varied traditions of Sanskrit Grammar.

The term Vyakarana, literally means analysis; and, it broadly stands for linguistic analysis, in general. But, in practice, when one refers to Sanskrit Grammar, it very often signifies Panini’s Grammar.

The Aṣṭādhyāyī of Panini is indeed a seminal work in the whole of linguistic sciences across all the regions of the world. And, it holds an unrivalled position in the history of Sanskrit Grammar. Because of its overwhelming importance, all the earlier works of different Grammatical Schools gradually disappeared. Panini’s Astadhyayi, in its turn, became the most influential school of Sanskrit grammar; and, has been the focal point of much critical and descriptive work over the last two millennia.

The arrival of the Aṣṭādhyāyī was nodoubt a significant event within the already-rich tradition of Indian linguistics. But , it had to wait a couple of centuries or more to gain any sort of recognition.

Pundit Harprasad Sastri mentions that the author of Arthashastra (350-275 BCE) was not aware of Panini’s Grammar, although it was written much before the time of Chanakya. There are many expressions in Arthashastra that are not in conformity with the rules of the Astadhyayi. It obviously means that even by the time of Chanakya, Panini’s work had not acquired recognition; and, was not in common use, even among the well-read.

And, it was only after Patanjali (about 150 BCE); Panini’s work gained universal recognition.

The Aṣṭādhyāyī consists of almost about 4,000 Sutras (Sūtrāṇi) or rules, distributed among eight (Asta) chapters (Adhyäyäh). Hence, the text, the Sūtrapāṭha of Pāṇini, is titled as Astädhyäyi. Each of its eight Chapters is subdivided into four sections or Padas (pādāḥ) – a total of 32 subsections.

Starting with about 1700 basic elements like nouns, verbs, vowels, consonants Panini puts them into classes. The construction of sentences, compound nouns etc. is explained as ordered rules operating on stated principles.

Panini , the student of Varsha, gained fame as a Great Grammarian based on his work Astadhyayi (the eight chapters) , which comprises about four thousand concise rules or Sutras, preceded by a list of sounds divided into fourteen groups. The Sutra Patha, the basic text of Astadhyayi has come down to us in the oral traditions; and has remained remarkably intact except for a few variant readings and plausible interpolations.

*

The Astadhyayi of Panini- also called Pāṇinīya-sūtra-patha; Astaka; Sabda-anushasana; and, Vritti-sutra – is not a Grammar in its strict sense. Astadhyayi was not composed for teaching Sanskrit, though it is a foundational text that can be used for understanding the language, speaking it correctly and using it precisely. It is a system of rules (Sūtrāṇi), which generates and regulates all the right forms of Sanskrit. Hence, Patanjali calls it Siṣṭa-jñānārthā Aṣṭādhyāyī. (M. Bh. VI. 3.109).

Panini aimed (lakshya) to ensure the correct usage of the words in order to discipline and to regulate the behaviour of the language of his time (Bhasha)- the literary and spoken (vaidika- laukika) – by purifying (Samskruta) both the forms, so that the inner meaning of the expressed words could shine forth unhindered.

*

For Panini, Grammar is a way of synthesis. His Grammar does not divide the words into stems and suffixes (as in the Nirukta of Yaska). On the contrary, it combines the constituent elements with a view to form words. Therefore, the Grammar here, is understood as ‘the word formation ‘or as an ‘instrument by which forms are created in various ways’ (vividhena prakarena akrtayah kriyante yena).

Panini’s Grammar, as per its working-scheme, attempts to build up Sanskrit words (pada) from their root forms (dhatu-prakara), suffixes (pratyaya), verbal roots; pre-verbs (upasarga); primary and secondary suffixes; nominal and verbal terminations; and , define their function (karya) in a sentence. These constituent elements are invested with meaning. Derived from these elements, in their various combinations, words and sentences are formed to cogently express collection of meanings as held by these elements.

Towards this end , Panini formulated different sets of rules , such as : the rules regulating a grammatical operation {vidhi-sütra); the rules defining a technical term {samjnä-sütra); and, the set of Meta-rules, guiding the interpretation and application of the other rules (paribhäsä-sütra), and headings (adhikära-süträ). The underlying principle of Panini’s work is that nouns are derived from verbs.

Thus, Astadhyayi could said to be a precise and logical system to form declinations, conjugations, composed words and derivatives, which enable one to understand the precise meaning of the words.

*

Thus, Panini defined the terms (samjna) employed in the grammar, set the rules for interpretation (paribhasha), and outlined, as guideline, the convention he followed.

Patanjali explains that Panini did not attempt to list out all the terms and words in the Sanskrit language (pratipada-pāṭha); because, such a method would surely have been futile and endless. Instead, he created a set of general (sāmānya) and particular (viśeṣa) rules that encapsulate all the salient features of the language, in a concise form, in a manner that one can understand and memorize with little effort (tat yathā ekena goṣpadapreṇa). Thus, Panini could capture a vast and mighty ocean (Varidhi) within the mark of a cow’s foot (गोष्पद) Goshpadi kruta vaareesham.

In other words, Panini created a system having finite number of rules that can be used to regulate a potentially infinite number of arrangements of utterances (sentences, vakya). He transformed the infinite into finite. His was indeed a pioneering task in any language. With his system it became possible to say whether or not a sequence of sounds represented a correct utterance in the Bhasha (Sanskrit).

Panini was also interested in the synthetic problems involved in formation of compound words; and the relationship of the nouns in a sentence with the action (kriya) indicated by the verb. With this, he sought to systematically analyze the correct sentences (vakya).

Panini’s grammar is distinguished above all similar works of other countries, partly by its thoroughly exhaustive investigation of the roots of the language and the formation of words; partly by its sharp precision of expression, which indicates with brevity whether forms come under the same or different rules.

According to Abhik Ghosh and Paul Kiparsk; the Astadhyayi provided comprehensive rules governing other aspects of the Sanskrit language, such as the phonological patterning of Sanskrit sounds. One could use these rules to generate new words as well as novel expressions and sentences.

Panini’s Astadhyayi has thus served, over the centuries, as the basic means (upaya) to analyze and understand Sanskrit sentences.

**

Dr. Victor Bartholomew D’avella writes in his well researched very scholarly Doctoral Thesis : Creating the perfect language : Sanskrit grammarians, poetry, and the exegetical tradition

The aim of Panini’s grammar, as Patañjali points out, is to give a series of general rules in the very condensed sūtra-style, with exceptions as appropriate. That is to say, Pāṇini tells the reader what to do in order to generate a correct word in a specific syntactic environment; he does not give, for the most part, the correct words themselves.

What one is instructed to do is to assign technical terms, add suffixes and augments to nominal and verbal bases (prātipadika and dhātus, respectively); and, make further modifications and substitutions as required. The entire process is termed prakriyā ,“derivation.”

His text , the Aṣṭādhyāyī , in substance, defines and uses a meta-language that must be mastered before the rules themselves can be understood or appliedin any meaningful way.

The meta-language includes, inter alia , unique functions for the cases,metarules (rules for interpreting and ordering other rules), and it s or anubandha s, “indicatory letters,” that indicate the application or prohibition of other rules, etc.

And, brevity is one of the famed aspirations of Sanskrit grammarians—including anuvṛtti , “rolling along,” i.e., the continuation of a word from one sūtra into what follows when no other word in the same syntactic position blocks it; and, pratyāhāras, “abbreviated list,” i.e., the equation of a longer series of letters with a shorter (usually mono-syllabic) combination of letters

The Aṣṭādhyāyī is , thus, a set of rules, with which the user can generate correct Sanskrit words out of nominal or verbal bases and suffixes. The interpretation of these highly condensed sūtras gave way to an extensive commentarial tradition, the study of which formed into a highly regarded and complex discipline unto itself.

Vyāghramukhī gauḥ, a tiger-faced cow

One of the difficulties in studying and writing about Sanskrit grammar is that the primary texts are extremely technical and foreign to most people who have not already familiarized themselves with Pāṇini’s methods and the type of argumentation that is employed throughout the tradition

Having said that; Astadhyayi is by no means an easy text. It presents many difficulties. It takes much effort, patience and time to wade through its tight-knit structure and its unique terminology. Every student finds it difficult to surmount Panini’s varied types of rules and exceptions. Apart from its overriding concern for economy , its every Sutra is affected by its neighbours. And, therefore, each time, one has to keep going back and forth; and, keep checking.

Despite its elegant structure, the Astadhyayi is hard to understand. Some called it Vyāghramukhī gauḥ, a tiger-faced cow.

*

Panini’s Ashtadhyayi is composed in Sutra form – terse and tightly knit; rather highly abbreviated. The text, therefore, does need a companion volume to explain it. And, over a period of time several commentaries were produced explaining and interpreting the Ashtadhyayi.

The earliest known explanatory note on the text was provided by Katyayana who wrote a Vartika, a brief explanation of Ashtadhyayi. Katyayana is assigned to third century BCE. Because of the considerable time-gap between Panini and Katyayana, their language and mode of expressions vary considerably.

About a hundred years later, Katyayana’s Vartika was followed by Vyakarana- Mahabhashya of Patanjali (Ca. Second century BCE), a detailed commentary on Panini’s work; together with his observations of the Vartika of Katyayana.

[Peter M Scharf says : The Astadhyayi consisting of nearly 4,000 rules is known to have undergone modifications at different stages.

To start with , Katyayana (4th-3rd BCE) suggested modifications to 1,245 of Panini’s rules ; generally, in the form of additions (Upa-sankhyana). Next, Patanjali (mid 2nd century BCE) , in his Mahabhashya, rejects many additions suggested by by Katyayana. Patanjali , in turn, brings in other modifications (Isti) ; and, articulates principles as pre-supposed in the Grammar.

Later, many modifications – as suggested by Katyayana and Patanjali – were adopted in the text of Jayaditya and Vamana’s Kaisika (7th century BCE)

That was followed by the tradition of Prakriya .]

*

For a very considerable length of time, the Grammar, as composed by Pāṇini, of the language of the Vedas and the spoken high-standard language pushed other grammatical works into oblivion.

In the course of the centuries, several additions and adaptations were proposed and variously accepted in the rules and in the lists of roots and other lexical norms. This gave rise to Prakriya-texts, in different forms and interpretations of Pāṇini’s grammar; and also to grammars that appeared under a new title; even if they are largely derived from and inspired by Pāṇini’s grammar.

Thereafter, the tradition of Prakriya texts took over. Such Prakriya or applied texts focused more on derivations and rule-applications; and, claimed to be relatively easier to comprehend. That was brought about by rearranging the rules of the Aṣṭādhyāyī; limiting their corpus to varying lengths with placement of blocks of rules following a certain functional hierarchy, conducive to practical-grammar.

The Prakriya texts were more interested in facilitating rule-application; than in providing theoretical concepts for guidance in interpretation. Many a times, these texts ended up compromising the precise interpretation of Panini’s rules

Dharmakīrti began the tradition of prakriyā or derivation texts, which do not follow the Aṣṭādhyāyī’s sequence of Sūtras; but rearranges them thematically around various grammatical topics, with suitable well considered comments (sāṃśodhya pariṣkr̥tya ca prakāśitaḥ).

The other more notable of such Prakriya texts are , the Prakriyā-kaumudi of Rāmacandra and the Vyakarana-Siddhānta-kaumudi of Bhațţoji Dīkşhita. And, Bhattoji Dikshita’s work, in turn, was followed by Sāra-siddhānta-kaumudī; a middle-length Madhya-siddhānta-kaumudī; and, shorter version Laghu-kaumudī all by Varadarāja a student of Bhattoji Dikshita.

*

Dharmakīrti (Eleventh Century), was the first to produce a Prakriya text titled the Rūpāvatāraḥ (rūpāņām avatāraḥ rūpāvatāraḥ -Upacārād rūpā-avatāram-adhikstya krto granthopi), which rearranged Pāṇini’s Sūtras in functional blocks as per the theoretical concepts and accepted practices of Grammar.

Rūpāvatāraḥ discusses only 2,664 rules (out of about 4,000 of Panini), where its focus shifts from details of interpretation to rule-application and types of derivation. The notion of Prakaraṇa (context) which Pāṇini developed, and which guided him in placement of his rules their application and interpretation, especially as it related to context sharing (ekavākyatā), in the Aṣṭādhyāyī, was modified.

As Prof. Rama Nath Sharma explains in his Indian Tradition of Linguistics and Pāṇini, the Rūpāvatāraḥ consists of two parts. The First part divided into ten Avatāras (manifestations): Saṃjñā (technical terms); Saṃhitā (close proximity between sounds); Vibhakti (inflectional endings); Avyaya (indeclinable); Strīpratyaya (feminine affixes) Kāraka, Samāsa (compounds); and , Taddhita (secondary suffixes).

The second part of Rūpāvatāraḥ has three major divisions (Paricchedas): Sārvadhātuka; Ardhadhātuka; and, Kṛt. Each division is further classified into sections (Prakaraṇas). The entire second part is presented under the general title of Dhātu-pratyaya-pañcikā.

*

Ramachandra (Ca. 14th Century) in his Prakriyā-kaumudī, just as Dharmakīrti, focused primarily on Sūtras dealing with the classical language. And, he also re-arranged the Sutras. But, he was more influenced by Kāśikā-vṛtti, the other School of Grammar. He did not discuss Panini’s Sutras in detail; but only gave a summary treatment; making it easier for the learners (ānantyāt sarvaśabdā hi na śakyante’ nuśāsitum / bālavyutpattaye’ smābhiḥ saṃkṣipyoktā yathāmatiḥ)

*

Bhaṭṭoji Dīkṣita, Kauṇḍa Bhaṭṭa and Nāgeśa Bhatta are three important authors in the development of the Siddhānta literature. The Siddhānta texts focused more on topics of theoretical interest and presented them in such an in-depth analytical manner that set standards of grammar in the tradition of Pāṇini.

Prof. Rama Nath Sharma describes the Vaiyākaraṇa Siddhānta Kaumudi written by Bhaṭṭoji Dīkṣita during the 17th century CE. as ‘a theoretical marvel’ that rooted out all competition and brought the Pāṇinian tradition to a full circle. His text re-arranges the Sūtras of Pāṇini under appropriate heads; and, renders it easier to follow. His treatment of the Sūtras is very brief, but very insightful, precise and thorough and comprehensive.

Bhaṭṭoji Dīkṣkita cites the opinion of the three sages (Muni-traya) of grammar (Pāṇini, Kātyāyana, and Patañjali) ; but, treats the Mahābhāṣya of Patanjali as an ultimate authority. Anything that contradicts the opinion of Patañjali is rejected.

Bhattoji Diksita’s work was later edited into three (Madhya, Laghu and Sara) abridged versions (Laghu-kaumudi) by his student Varadarāja, reducing the number of rules to 723 (from 3,959 of Pāṇini). This is said to be very useful to students of Sanskrit grammar who are not capable of studying the Ashtadhyayi or Siddhanta Kaumudi with its Sanskrit commentaries.

**

Prakriyā-sarvasva by the brilliant and versatile author Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭa of Melputtūr (17th century) is at least as comprehensive as the well-known Pāṇinian grammar of Bhaṭṭoji Dīkṣita, the Siddhānta-kaumudī.

But it significantly differs from it in both method and substance; even if both remain within the framework of Pāṇini’s system.

The Prakriyā-Sarvasva provides many novel perspectives on theoretical issues in Pāṇinian grammar and represents a much-neglected pragmatic approach (in contrast to the exegetic approach of Bhaṭṭoji Dīkṣita). Since its object is Sanskrit as used and accepted not only by the three sages – Pāṇini, Kātyāyana and Patañjali – but also by later authors of the Sanskrit tradition, it can be justly regarded as a Pāṇinian grammar of living Sanskrit. Three different dimensions of the Prakriyā-Sarvasva confirm this. The features of the grammar, which, like the Siddhānta-Kaumudī, is a re-ordered version of Pāṇini’s grammar; the principles of the grammar as explained and illustrated in a special section of the grammar; the defense, in a brief treatise, of the basic principles against other grammarians.

[For more this; please read ‘ Pāṇinian grammar of living Sanskrit: features and principles of the Prakriyā-Sarvasva of Nārāyaṇa-Bhaṭṭa of Melputtūr’ by Jan E.M. Houben]

Panini and Yaska

Both the scholars – Yaska and Panini – composed their works at the time, when certain Vedic words had become obsolete ; and, a number of new forms were coming into usage.

While Yaska’s focus was mainly on the etymology and the interpretation of certain obsolete Vedic terms and words; Panini had in view both Vedic and the spoken language at the time.

The main object of Panini’s Sutras is to deal with the Bhasha, living speech of the day. He had the advantage of consulting many earlier treatises on Grammar composed by his predecessors. He developed a system of Grammar, which bears the stamp of accuracy and thoroughness.

Though Panini distinguishes between the language of sacred texts and the usual language of communication , he covers both the forms of language.

Panini’s general rules , which generates all correct forms of Sanskrit, are applicable to both of the domains of Sanskrit – the language of his time (Bhasha); and, the archaic language of the Vedic hymns (Chhandas).

But, those rules which applied only to the language of the Vedic texts are treated separately by stating the specific Vedic sub-domains.

And, the domain of the contemporary spoken standard Sanskrit was also then sub-divided into as those of scholastic usage and regional dialects.

Thus, unlike the Nirukta of Yaska and the Pratisakhya texts, Panini gave importance to the language in use among the well-educated (Sista) of his time; as also to the language of the Vedas (Chhandas).

The Aṣṭādhyāyi marks the beginning of what is sometimes called ‘Classical Sanskrit’ – in contrast with Chhandas, the language of the Vedic texts – and the Sanskrit of the Kavyas of the medeival periods.

Panini’s contribution to Sanskrit language

Regarding Panini’s contribution to Sanskrit language, Prof. A L Basham writes (The Wonder That Was India):

After the composition of the Rig Veda, Sanskrit developed considerably. New words, mostly borrowed from non Aryan sources, were introduced, while old words were forgotten, or lost their original meanings. In these circumstances doubts arose as to the true pronunciation and meaning of the older Vedic texts, though it was generally thought that unless they were recited with complete accuracy they would have no magical effectiveness, but bring ruin on the reciter. Out of the need to preserve the purity of the Vedas India developed the sciences of phonetics and grammar. The oldest Indian linguistic text, Yaska’s Nirukta, explaining obsolete Vedic words, dates from the 5th century B.C., and followed much earlier works in the linguistic field.

Panini’s great grammar, the Astadhyayi (Eight Chapters) was probably composed towards the end of the 5-th century BCE (?). With Panini, the language had virtually reached its classical form, and it developed little thenceforward, except in its vocabulary.

By this time, the sounds of Sanskrit had been analysed with an accuracy never again reached in linguistic study until the 19th Century. One of ancient India’s greatest achievements is her remarkable alphabet, commencing with the vowels and followed by the consonants, all classified very scientifically according to their mode of production, in sharp contrast to the haphazard and inadequate Roman alphabet, which has developed organically for three millennia. It was only on the discovery of Sanskrit by the West that a science of phonetics arose in Europe.

The great grammar of Panini, which effectively stabilized the Sanskrit language, presupposes the work of many earlier grammarians. These had succeeded in recognizing the root as the basic element of a word, and had classified some 2,000 monosyllabic roots which, with the addition of prefixes, suffixes and inflexions, were thought to provide all the words of the language. Though the early etymologists were correct in principle, they made many errors and false derivations, and started a precedent which produced interesting results in many branches of Indian thought

There is no doubt that Panini’s grammar is one of the greatest intellectual achievements of any ancient civilization, and the most detailed and scientific grammar composed before the 19th century in any part of the world. The work consists of over 4000 grammatical rules, couched in a sort of shorthand, which employs single letters or syllables for the names of the cases, moods, persons, tenses, etc. In which linguistic phenomena arc classified.

Some later grammarians disagreed with Panini on minor points, but his grammar was so widely accepted that no writer or speaker of Sanskrit in courtly circles dared seriously infringe it. With Panini the language was fixed, and could only develop within the framework of his rules. It was from the time of Panini onwards that the language began to be called Samskruta, “perfected” or “refined”, as opposed to the Prakrta (unrefined), the popular dialects which had developed naturally.

Paninian Sanskrit, though simpler than Vedic, is still a very complicated language. Every beginner finds great difficulty in surmounting Panini’s rules of euphonic combination (Sandhi), the elaboration of tendencies present in the language even in Vedic times. Every word of a sentence is affected by its neighbours. Thus na- avadat (he did not say) becomes navadat. But, na-uvaca (with the same meaning) becomes novaca. There are many rules of this kind, which were even artificially imposed on the Rig Veda, so that the reader must often disentangle the original words to find the correct meter.

Panini, in standardizing Sanskrit, probably based his work on the language as it was spoken in the North-West. Already the lingua franca of the priestly class, it gradually became that of the governing class also. The Mauryas, and most Indian dynasties until the Guptas, used Prakrit for their official pronouncements.

As long as it is spoken and written a language tends to develop, and its development is generally in the direction of simplicity. Owing to the authority of Panini, Sanskrit could not develop freely in this way. Some of his minor rules, such as those relating to the use of tenses indicating past time, were quietly ignored, and writers took to using imperfect, perfect and aorist indiscriminately; but Panini’s rules of inflexion had to be maintained. The only way in which Sanskrit could develop away from inflexion was by building up compound nouns to take the place of the clauses of the sentence.

With the growth of long compounds Sanskrit also developed a taste for long sentences. The prose works of Bana and Subandhu, written in the 7th century, and the writings of many of their successors, contain single sentences covering two or three pages of type. To add to these difficulties writers adopted every conceivable verbal trick, until Sanskrit literature became one of the most ornate and artificial in the world.

Indian interest in language spread to philosophy, and there was considerable speculation about the relations of a word and the thing it represented. The Mimamsa School, reviving the verbal mysticism of the later Vedic period, maintained that every word was the reflexion of an eternal prototype, and that its meaning was eternal and inherent in it. Its opponents, especially the logical school of Nyaya , supported the view that the relation of word and meaning was purely conventional. Thus the controversy was similar to that between the Realists and Nominalists in medieval Europe.

Classical Sanskrit was probably never spoken by the masses, but it was never wholly a dead language. It served as a lingua franca for the whole of India, and even today learned Brahmans from the opposite ends of the land, meeting at a place of pilgrimage, will converse in Sanskrit and understands each other perfectly.

The Astadhyayi in modern times

As mentioned earlier; the Astadhyayi of Panini is one of the most remarkable works that the world has ever seen. It is primarily a much trusted reference-source concerning Sanskrit Grammar. As for Pāṇini, he came to be regarded as the ideal or the icon for scholarship in classical India.

But, what is amazing is the type and extent of attention that Astadhyayi attracted in the Nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from the scholars of linguistic sciences in the West; the community of scientists; and, the developers of the computer virtual languages.

*

Brevity

Panini’s Astadhyayi is composed in Sutra form – terse and tightly knit; rather highly abbreviated. Brevity was one of his main concerns. Panini used a concise logical system of notations that allowed him to describe Sanskrit in as little space or in as fewer words as possible.

It is generally agreed that the Panini’s system is based on a principle of economy. This makes its structure of special interest to cognitive scientists.

In that, the modern linguistic analysts recognized what they called as the minimum description length principle. That principle states that the best model is that which efficiently achieves the best compression of grammatical rules. It is designed to express the set of rules in briefest possible manner.

As the Indologist Johan Frederik (Frits) Staal pointed out; “Panini’s linguistic rules can live on in daughter languages even after historical changes have disrupted their phonetic basis”.

According to the legendary linguist Noam Chomsky, of Massachusetts Institute of Technology : the Aṣṭādhyāyī provided the first ‘generative grammar’ in the modern sense of the word; meaning a complete set of rules for combining morphemes, (the smallest meaningful units of language, such as word roots and stems, prefixes and suffixes), into grammatical sentences.

*

A Sutra has to be comprehensive, objective, brief and precise. Panini chose the technique of context-sharing (eka-vakyata). Panini’s rules are interdependent. It is because of two reasons – physical nearness; and, the other is because of Anuvrtti, which is now termed as ‘recurrence’. The Anuvrtti controls the reading of a Sutra in conjunction with its preceding and subsequent Sutra .The higher-level rules within the domain are brought close or within the context of the lower-level rule. This helps to reconstruct the shared-context of a given rule, within a domain; and, better interpretation of the lower-level rule.

Thus, a Sutra, when fully equipped with all the information required for its application , becomes a statement.

**

Converting letters based on its position in alphabet to numbers

Some scholars believe that Panini was the first to come up with the idea of using letters of the alphabet to represent numbers. And, that the Brahmi numerals were developed by using letters or syllables as numerals.

*

Astadhyayi and western linguistics

Pāṇini’s work became known in 19th century Europe, where it influenced the linguistics of that period.

The Historian Prof. A. L. Basham opined that It was only on the discovery of Sanskrit by the West that a science of phonetics arose in Europe

It is said; Pāṇini’s work was of much help in the development of modern linguistics through the efforts of scholars such as Franz Bopp, Ferdinand de Saussure, Leonard Bloomfield, and Roman Jakobson. Bopp was a pioneering scholar of the comparative grammars of Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages.

During 1839-40, Otto Böhtlingk published Pânini’s acht Bücher grammatischer Regein, a two-volume translation of the Aṣṭadhyāyī. And again, towards the end of the Nineteenth Century, he brought out Pânini’s Grammatik, a commentary on Panini’s work.

Ferdinand de Saussure, in his most influential work, Course in General Linguistics (Cours de linguistique générale) that was published posthumously (1916), took the idea of the use of formal rules of Sanskrit grammar and applied them to general linguistic phenomena.

Modern linguists like Ferdinand de Saussure and Noam Chomsky said Panini’s style of notation is similar to Backus-Naur form, which is used to define both human languages and programming languages.

Ferdinand de Saussure cited Indian Grammar as an influence on some of his ideas. In his De l’emploi du genitif absolu en sanscrit (On the Use of the Genitive Absolute in Sanskrit) published in 1881, a monograph on the genitive absolute, he specifically mentions Panini as an influence on the work.

In Noam Chomsky’s Optimality Theory, the hypothesis about the relation between specific and general constraints is known as “Panini’s Theorem on Constraint Ranking”.

Earlier, the founding father of American structuralism, Leonard Bloomfield, had also written a paper ‘ On some rules of Panini’.

Prem Singh, in his foreword to the reprint edition of the German translation of Pāṇini’s Grammar in 1998, concluded that the “effect Panini’s work had on Indo-European linguistics shows itself in various studies” and that a “number of seminal works come to mind,” including Saussure’s works and the analysis that “gave rise to the laryngeal theory,” further stating: “This type of structural analysis suggests influence from Panini’s analytical teaching.”

Panini’s grammar has been evaluated from various points of view. After all these different evaluations, I think , his grammar merits assertion as being one of the greatest monuments of human intelligence.

: J J O’Connor and E F Robertson

*

Astadhyayi and Mendeleev’s periodic tables

According to Professor Paul Kiparsky of Stanford University, there are striking similarities between the Periodic Tables of Mendeleev; and, the introductory Śhiva-Sūtras (Maheshvara-Sutra) in Panini’s Grammar.

It is said; Mendeleev gained familiarity with the Grammar of Panini through his friend, the Sanskrit scholar , Böhtlingk, who was preparing the second edition of his book on Panini (Acht Bücher grammatischer Regein ), at about this time

And, Mendeleev was much impressed by Panini’s logic; and, wished to honour Pānini with his nomenclature.

Mendeleev, presumably, saw Panini’s approach as analogous to his own quest for a Grammar of nature. One of the most iconic symbols of modern science, as it arose in the latter part of the 19th century in Europe, may thus owe a significant debt to an ancient Eastern language and culture.

The noted scholar Subhash Kak in his paper How Sanskrit Led To The Creation Of Mendeleev’s Periodic Table ; observes:

Convinced that the analogy was fundamental, Mendeleev theorized that the gaps that lay in his table must correspond to undiscovered elements. For his predicted eight elements, he used the prefixes of eka, dvi, and tri (Sanskrit one, two, three) in their naming.

Mendeleev’s use of the Sanskrit numerals eka, dvi-, and tri – in naming the as yet undiscovered elements are indeed homage to Pāṇini.

Professor Paul Kiparsky of Stanford University writes:

The analogies between the two systems are striking. Just as Panini found that the phonological patterning of sounds in the language is a function of their articulatory properties, so Mendeleev found that the chemical properties of elements are a function of their atomic weights.

Like Panini, Mendeleev arrived at his discovery through a search for the “grammar” of the elements (using what he called the principle of isomorphism, and looking for general formulas to generate the possible chemical compounds).

Just as Panini arranged the sounds in order of increasing phonetic complexity (e.g. with the simple stops k,p… preceding the other stops, and representing all of them in expressions like kU, pU) so Mendeleev arranged the elements in order of increasing atomic weights, and called the first row (oxygen, nitrogen, carbon etc.) “Typical (or representative) elements”.

Just as Panini broke the phonetic parallelism of sounds when the simplicity of the system required it, e.g. putting the velar to the right of the labial in the nasal row, so Mendeleev gave priority to isomorphism over atomic weights when they conflicted, e.g. putting beryllium in the magnesium family because it patterns with it even though by atomic weight it seemed to belong with nitrogen and phosphorus. In both cases, the periodicities they discovered would later be explained by a theory of the internal structure of the elements.

*

According to Abhik Ghosh and Paul Kiparsk; the Astadhyayi also provided comprehensive rules governing other aspects of the Sanskrit language, such as the phonological patterning of Sanskrit sounds. One could use these rules to generate new words as well as novel expressions and sentences. In our view, what Pāṇini did for Sanskrit, Mendeleev tried to do for chemistry.

The Astadhyayi and Computer language

Much has been written and discussed about the plausible relation between the Computer Science and the concepts, rules of Panini’s Astadhyayi. Needleless to say, it is very fascinating.

The Western scholars describe Ashtadhyayi as a generative as well as descriptive text. With its complex use of Meta-rules, transformations, and recursions, the grammar in Ashtadhyayi is compared to the Turing machine, an idealized mathematical model that reduces the logical structure of any computing device to its essentials.

In fact, Panini’s work is context-sensitive; it addresses only Sanskrit; and, is not a ‘universal Grammar’. But, a most amazing thing happened in the twentieth century with the development of computer languages. The writers of these virtual languages discovered that Panini’s rules can be used for describing perhaps all human languages; and, it can be used for programming the first high level programming language, such as ALGOL60. It is said; by applying Panini’s rules it is possible to check whether or not a given sequence of statement forms a correct expression in a particular programming language.

The Backus-Normal-Form-(BNF), a meta-linguistic-formula, was discovered independently by John Backus in 1959; but , Panini’s notation is beleived to be equivalent in its power to that of Backus; and, has many similar properties. Interestingly, at one time, the name Pāṇini Backus Form was also suggested, in view of the fact that Pāṇini had also independently developed a similar notation earlier.

The structure of Pāṇini‘s work contains a meta-language, meta-rules, and other technical devices that make this system effectively equivalent to the computing machine. Although it didn’t directly contribute to the development of computer languages, it influenced linguistics and mathematical logic, which, in turn, had earlier given birth to computer science.

*

The specific feature of the Astadhyayi that is of interest to the computer science is the system that is based on the principle of economy. The striking feature of the Sutra format which is employed in Astadhyayi is the use of abbreviated expressions by way of several algebraic devices.

The other is the arrangement of the rules and the logic that governs it. The Sutras are arranged, topic wise, in such a manner that a given rule borrows an item from the preceding context. That ensures continuity and economy of expression to a large extent

Panini employs a device called Anubandha, a coded-letter, which indicates a grammatical function, comparable to elision and reduplication. Panini made use of almost all vowels and consonants as symbols for various functions. And, Anubandhas are added to various grammatical units such as suffix, an augment and a root.

Another aspect of Panini’s descriptive technique is the law of Utsarga (general rules) and Apavada (exceptions) that relates exceptions and individual rules. Here, the exception (Apavada) is more powerful that the general-rule (Utsarga). Therefore, before applying the Utsarga one has to check for its Apavada(s). Further, once an Utsarga is barred from entering in to the area of its exception, it can never enter the area again.

Panini did not use all Padas in each Sutra to complete the meaning of the each Sutra; instead, he took some Padas from previous Sutras to achieve completeness. And, this process is analogous to Recursion.

It is said; the shades of some of the modern-day theories of programming languages can be found in Panini’s work; for instance: Recursion; Inheritance; and, Polymorphism. For more on that, please check here ; and here.

There are also dissenting views which say: while Sanskrit may be a good language for knowledge representation, It certainly is not the best language for programming

**

The research paper by Gerald Penn and Paul Kipraski ‘Panini and the Generative Capacity of Contextualized Replacement Systems’ concludes :

The underlying formalism to Painian grammar, while our knowledge of it is incomplete, presents enough evidence to conclusively demonstrate that it is far greater in its expressive power than either RL or CFL.

Panini has nevertheless anticipated modern generative syntactic practice in defining for himself a very versatile tool which he then applies very thriftily to advance his own objectives of grammatical brevity and elegance.

As a result, his Astadhyayı may even be amenable to an RL-style analysis, as Hyman (2007) has claimed. But in light of this investigation, the result of this analysis certainly could not be a grammar in Panini’s own style, but rather Panini’s grammar recast into someone else’s style.

No proof is presented here, however, that the Paninian framework is complete in the sense that it can generate any context-sensitive language. This remains an open question.

***

Please also read a very scholarly research paper: Panini’s Grammar and Computer Science by Saroja Bhate and Subhash Kak

This paper concludes with the statement:

One great virtue of the Paninian system is that it operates at the level of roots and suffixes defining a deeper level of analysis than afforded by recent approaches like generalized phrase structure grammars that have been inspired by development of computer parsing techniques. This allows for one to include parts of the lexicon in the definition of the grammatical structure. Closeness between languages that share a great deal of a lexicon will thus be represented better using a Paninian structure.

These fundamental investigations that have bearing on linguistics, knowledge representation, and natural language processing by computer require collaboration between computer scientists and Sanskrit scholars. Computer oriented studies on Astadhyayi would also help to introduce AI (artificial intelligence), logic, and cognitive science as additional areas of study in the Sanskrit departments of universities. This would allow the Sanskrit departments to complement the programme of the computer science departments. With the incorporation of these additional areas, a graduate of Sanskrit could hope to make useful contributions to the computer software industry as well, particularly in the fields of natural language processing and artificial intelligence.

****

Prof. John Kadvany in his paper ‘Panini’s Grammar and Modern Computation’ writes :

In conclusion, we note the modern idea that computation can be expressed in any media you like, with software an abstraction independent of any hardware implementation. Panini is almost an historical example of just that media freedom, as his grammar is formulated for orally expressed, spoken Sanskrit.

But according to the phonemic hypothesis that oral formulation must have relied on lost inscriptional aids. A similar dependence of segmentation skills on the duality principles grounding alphabetic writing then must also be true of modern symbolic calculi, whether formal logics or computing languages. Modern computing languages, like structured grammars, require the tiered, hierarchical structures of symbolic forms found first in Panini.

That power requires a systematic approach to duality of patterning, like that of alphabets, which then can be applied to written language and formal systems too. The modern notion of a formal metalanguage requires the inherently metalinguistic tools of an alphabet or its equivalent to get started at all.

This basis is taken for granted in Frege’s 1879 Begriffsschrift, or ‘concept-script’32; in the classic computing Q4 paradigms of Post and Turing with their explicit inscriptional metaphors; and in computing languages and modern formal systems generally. Such a basis was almost surely used by Panini, his grammar’s formalism being the earliest historical example of the kind ubiquitous today in computer science and mathematical logic.

Nonetheless, Panini showed, by constructing a whole formal language through the affixing resources of the Sanskrit object language itself, that the differences between natural and artificial computing languages are smaller than often thought. Not because natural languages are, or are close to being, computing languages, but because the development of computing languages, whether ancient or modern, is a continuation of natural language constructions by their own means.

****

Mr. Anand Mishra, Ruprecht Karls University, Heidelberg, Germany, has attempted a model for computer representation of the Panini’s system of Sanskrit grammar. Based on this model, he has rendered the grammatical data and simulated the rules of Astadhyayi on computer. Thereafter, he employed these rules for generation of morpho-syntactical components of the language. He says, these generated components are used develop a lexicon based on the principles of Panini.

Please check: Simulating the Paninian System of Sanskrit Grammar

****

Prof. Tiziana Pontillo, University of Cagliari, Philology, Literature and Linguistics, in her paper : Pāṇini’s zero morphs as allomorphs in the complexity of linguistic context, writes about Zero (lopa, luk, slu and lup) of morphs) :

Pāṇini generally singles out a prototypic morph (the placeholder – sthānin), possibly by selecting it on the basis of the productivity parameter, and uses it as a sort of morpheme, proceeding with cataloguing all its allomorphs, zero morph included, as its substitutes. Therefore, though, on the one hand, he avoids the purely abstract level of language and concentrates – as much as possible – on actual linguistic material, on the other hand, he postulates 7 different vi morphemes, which have an only overt phonological realization, i.e., a zero form

Panini’s zero-postulation is almost entailed in his general model of replacive grammar, which even though founded on a biplanar definition of morpheme, does not include a veritable replacive morphology. In fact, some otherwise typically synchronic morphological relationships, such as the vowel gradation in the derivation- or inflection-patterns, are unrelated to the aim of conveying sets of distinct grammatical functions or meanings. As we have seen, vr̥ddhi- or guṇa-replacements are merely conditioned by the phono-morphological right context

Just as the whole substitution-schema adopted by Pāṇini, the zero replacement is not based on supposed paradigmatic-relations between the analysed forms, such as cz. žena ‘woman’ (nom. sing.) / ženy ‘women’ (nom. pl.) / žen ‘of women’ (gen. pl.) focused on by Saussure. Pāṇini rather – as highlighted by Al-George (1967: 121) – postulates a zero by analogical assimilation in the very place where European linguists could postulate a zero by significant opposition.

Furthermore, the allomorphs in use in the Aṣṭādhyāyī is not restricted to the mere description of the phenomenon of some morphs alternating with each other but is involved in a broader schema which aims at jointly accounting for the different linguistic levels. Each zero (allo)morph is postulated within a sort of morphologic syntagma, of which a component does not have an overt form but is understood to be present, thanks to an association with other syntagmas where this same unit has its phonic counterpart. The zero morph has thus to be analysed as a placeholder which plays the crucial role of mustering all the relevant morphological, semantic and syntactic features conveyed in absentia of the word form which commonly convey them, practically working as the recipient target of the allowed extension of the relevant rules.

A set of papers presented at the the 4th Inter-national Sanskrit Computational Linguistics Symposium (4i-SCLS), New Delhi, India, December 10-12, 2010 ; as edited by Sri Girish Nath Jha

The papers variously cover such topics as : 1. Phonology and speech technology; 2. Morphology and shallow parsing; 3. Syntax, semantics and parsing; 4. Lexical resources, annotation and search; 5. Machine translation and ambiguity resolution; and, 6. Computer simulation of Astadhyayi.

The papers relating to the computer simulation of Astadhyayi cover topics relating to : (1) the Asiddhatva principle corresponding to the concept of ‘filter’ – mainly to prevent the application of a Sutra on the substitute (pages 231 to 238) ; and, (2) the proximity of the structure and operational methodological enquiry of the Vedanga (four of which deal with language), to the working principles of the Astadhyayi; putting together a generalized model to cover various aspects (pages 239 to 258) .

[https://www.academia.edu/8123710/Building_a_Prototype_Text_to_Speech_for_Sanskrit email_work_card=view-paper]

Discovering the Algorithm for Rule Conflict Resolution in the Aṣṭādhyāyī

According to a research paper published in Apollo—University of Cambridge Repository (2022). DOI: 10.17863/cam.80099

Indian PhD student Rishi Rajpopat, 27, decoded a rule taught by Panini, master of the ancient Sanskrit language who lived around two-and-a-half-thousand years ago, the report said, adding that Panini’s grammar, known as the Astadhyayi, relied on a system that functioned like an algorithm to turn the base and suffix of a word into grammatically correct words and sentences.

However, two or more of Panini’s rules often apply simultaneously; resulting in rule conflicts. Panini taught a “metarule”, traditionally interpreted by scholars as meaning “in the event of a conflict between two rules of equal strength, the rule that comes later in the grammar’s serial order wins”.

However, this often led to grammatically incorrect results. Rishi Rajpopat rejected the traditional interpretation of the metarule and argued that Panini meant that between rules applicable to the left and right sides of a word respectively, Panini wanted us to choose the rule applicable to the right side. And, using this reasoning, Rajpopat discovered that Panini’s algorithms can really generate words and phrases that are flawlessly grammatically perfect.

For instance; take the words “Mantra” and “Guru” as examples.

In the sentence “Devāḥ prasannāḥ mantraiḥ” (“The Gods [Devāḥ] are pleased [prasannāḥ] by the Mantras [mantraiḥ]”) we encounter “rule conflict” when deriving mantraiḥ “by the mantras.” The derivation starts with “mantra + bhis.” One rule is applicable to left part, “mantra’,”; and the other to right part, “bhis.” We must pick the rule applicable to the right part, “bhis,” which gives us the correct form, “mantraiḥ.”

And, while trying to create the word Guru in the sentence “Jñānaṁ dīyate guruṇā” (“Knowledge [jñānaṁ] is imparted [dīyate] by the Guru [Guruṇā]”). It is a well-known phrase that meaning “by the guru.”

The word’s basic elements are the Guruna; and, there are two rules that apply if one follows Panini’s instructions to produce the term that would imply “by the Guru” — one for the word “Guru” and one for “ā.”

We encounter rule conflict when deriving Guruṇā “by the Guru.” One rule is applicable to left part, “Guru”; and the other to right part. “ā“. We must pick the rule applicable to the right part, “ā,” which gives us the correct form, “Guruṇā.”

***

A major implication of Dr. Rajpopat’s interpretation is said to be that we now have the algorithm that runs Panini’s grammar; and, we could potentially teach this grammar to computers.

Dr. Rajpopat said, “Computer scientists working on natural language processing gave up on rule-based approaches over 50 years ago… So, teaching computers how to combine the speaker’s intention with Panini’s rule-based grammar to produce human speech would be a major milestone in the history of human interaction with machines, as well as in India’s intellectual history.”

A page from an 18th-century copy of the Dhātupāṭha of Pāṇini (MS Add.2351) held by Cambridge University Library. Credit: Cambridge University Library

[ For more on this, please check: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/332654 ]

If two rules are simultaneously applicable at a given step in a Pāṇinian derivation, which of the two should be applied? Put differently, in the event of a ‘conflict’ between the two rules, which rule wins? In the Aṣṭādhyāyī, Pāṇini has taught only one metarule, namely, 1.4.2 vipratiṣedhe paraṁ kāryam, to address this problem.

Traditional scholars interpret it as follows: ‘in the event of a conflict between two rules of equal strength, the rule that comes later in the serial order of the Aṣṭādhyāyī, wins.’ Pāṇinīyas claim that if one rule is nitya, and its simultaneously applicable counterpart is anitya, or if one is antaraṅga and the other bahiraṅga, or if one is an apavāda (exception) and the other the utsarga (general rule), then the two rules are not equally strong and consequently, we cannot use 1.4.2 to resolve the conflict between them. The nitya, antaraṅga and apavāda rules are stronger than their respective counterparts and thus win against them.

But this system of conflict resolution is far from perfect: the tradition has had to write numerous additional metarules to account for umpteen exceptions. In this thesis, I propose my own solution to the problem of rule conflict which I have developed by relying exclusively on Pāṇini’s Aṣṭādhyāyī.

I replace the aforementioned traditional categories of rule conflict with a new classification, based on whether the two rules are applicable to the same operand (Same Operand Interaction, SOI), or to two different operands (Different Operand Interaction, DOI). I argue that, in case of SOI, the more specific i.e., the ‘exception’ rule, wins.

Additionally, I develop a systematic method for the identification of the ‘more specific’ rule – based on Pāṇini’s style of rule composition. I also argue that, in order to deal with DOI, Pāṇini has composed 1.4.2, which I interpret as follows: ‘in case of DOI (vipratiṣedha), the right-hand side (para) operation (kārya) prevails.’

I support my conclusions with both textual and derivational evidence. I also discuss my interpretation of certain metarules teaching substitution and augmentation, the concept of aṅga, and the asiddha and asiddhavat rules and expound on not only their interaction with 1.4.2 but also their influence on the overall functioning of the Pāṇinian machine.

In the next part

Let us get to know of Panini as a person

Sources and References

- The Ashtadhyayi of Panini. Translated into English by Srisa Chandra Vasu

Published by Sindhu Charan Bose at The Panini Office, Benares – 1897 - Panini

- Panini –His place in Sanskrit Literature by Theodor Goldstucker, A.Trubner & Co., London – 1861

- Simulating the Paninian System of Sanskrit Grammar by Anand Mishra

- India as Known to Pānini by V. S. Agrawala, Lucknow University of Lucknow, 1953

- Computing Science in Ancient India by Professor T.R.N. Rao and Professor Subhash Kak

- Panini’s Grammar and Computer Science by Saroja Bhate and Subhash Kak

- How Sanskrit Led To The Creation Of Mendeleev’s Periodic Table

- Indian Tradition of Linguistics and Pānini by Prof. Rama Nath Sharma

- Pāṇini: Catching the Ocean in a Cow’s Hoofprint by Vikram Chandra

- Panini: His Work and Its Traditions by George Cardona

- A Brief History of Sanskrit Grammar by James Rang

- Introductionto Prakrit by Alfr ed C . Woolner

- Chandah Sutra of Pingala Acharya, Edited by Pandita Visvanatha Sastri , Printed at the Ganesha Press, Calcutta – 1874

- ALL IMAGES ARE FROM INTERNET

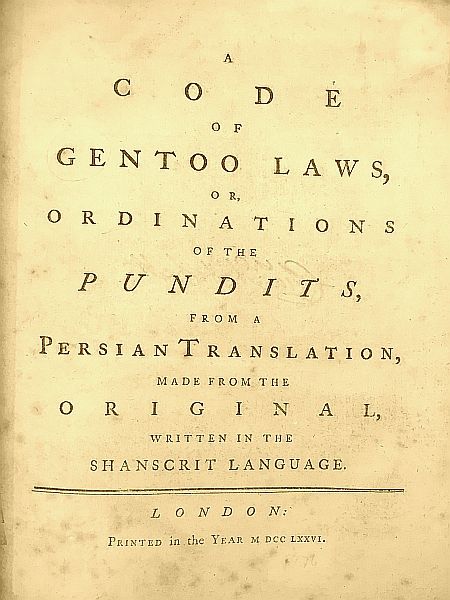

Accordingly, Warren Hastings who was appointed as Governor General of Bengal in April, 1772 was asked to execute the Company’s decision; and, interalia come up with a ‘Judicial Plan’. His immediate object thereafter was to devise an arrangement to dispense law/justice to the Indian litigants in ways that are as close as possible to their own customs, in matters of person and property; and, particularly, on matters considered as religious. But, the dispensation of justice had to be according to the British norms and by British Judges; and it was made explicitly clear that employing the Indian scholars or pundits as judges was totally out of question.

Accordingly, Warren Hastings who was appointed as Governor General of Bengal in April, 1772 was asked to execute the Company’s decision; and, interalia come up with a ‘Judicial Plan’. His immediate object thereafter was to devise an arrangement to dispense law/justice to the Indian litigants in ways that are as close as possible to their own customs, in matters of person and property; and, particularly, on matters considered as religious. But, the dispensation of justice had to be according to the British norms and by British Judges; and it was made explicitly clear that employing the Indian scholars or pundits as judges was totally out of question.