I would greatly appreciate it, if could help me in understanding some aspects of Karna’s life.

I have, during my research, not really been able to find out the antecedents of Adhiratha, Vasusena’s adoptive father. And as you are well aware, a lot of the issues confronting the adolescent, and later, the adult Karna hinge on him being addressed as Sootaputra. I thought you could shed some light on this. Technically, Adhiratha’s mother should be a Brahmin/Rishi’s daughter, while his father would be a Kshatriya warrior King/ Prince, if he is a Soota.

Also, is it possible that Adhiratha, and Vidura (Also called Daasi-Suta {not Soota}) could have had some connection? Wasn’t Vidura’s wife Aruni (also a Soota, the daughter of King Devaka by a Shudra handmaid) also called Radha, as was Adhiratha’s wife (From whom Karna got the Metronymic Radheya)? Although, strictly going by definitions, Vidura is not really a Soota at all- he was born of a Shudra maid and Rishi Vyasa…

I would love to hear more from you on this… Blessings, Deepam

A nameless, aimless waif on earth.

Relentless Fate swoop’d thee to serve Her aim.

And veer’d thy steps into a nest of plots

And feuds: A Royal house of power-drunk sots,

Perdue to Pity, Chivalry, e’en shame!

Beguil’d with bribe of crown to battle in cause

Of king, who match’d thee ‘gainst thy very kin,

Thy valor, bounty, innocence of sin

Avail’d thee naught ‘gainst unjust death. Alas!

Befooled babe ‘gainst Fate’s bewildering odds!

Bejeweled bauble of the jeering Gods!

—T.P. Kailasam

Welcome

1.1. Dear Shri Deepamjee, You are welcome. Thank you for asking the questions. I find the subject of your research quite interesting; and more interesting is your background. You say that after being an Officer in the Army and quitting it about a dozen years ago you have taken up research; and have authored a book on ‘The Timeless Faith: Dialogues on Hinduism’.

1.2. You mentioned that you registered on Sulekha only in order to talk to me. That’s ok. May I suggest you stay here and look around; you will find a number of wonderfully gifted persons who write with great skill and enterprise on diverse subjects . Your interactions could be mutually beneficial.

1.3. You have raised a number of issues and my response might be lengthy. I therefore prefer to post it as blog, rather than as a comment or send it to you by E-mail .I reckon that if posted on the net it might also help those looking for similar answers.

1.4. I suggest you read my earlier posts on Draupadi, Kunti and Satyavathi, the three most remarkable women of Mahabharata who wielded enormous influence and power with skill and sagacity over the lives of those around them; and more importantly they knew precisely when not to exhibit their power. You might also read my post on the concept of Dharma as it was employed and demonstrated in Mahabharata. This article briefly discusses some of the issues related to your research; it might be of use, modestly.

The Question of Caste

2.1. Since your questions touch upon caste and other social issues, it is important to understand the matrix of the then prevailing system.

The question of caste and the systems of its classifications and sub- classifications played a crucial role in the story of Mahabharata; and particularly in the lives of those disadvantaged ones. The caste spread its tentacles deep into every aspect of the Mahabharata society; and had a vise- like stranglehold over matters concerning ones position and rights in the society, as also the matters related to property –rights, inheritance etc.

2.2. The Mahabharata society functioned, I reckon, not as a collection of free individuals enjoying equal rights; or as a cohesive society bound together by a set of equitable –common civil laws. Its society was viewed as a community made up of distinct caste groups. Its specific position in social hierarchy, its economic and social functions, rights and responsibilities of each group were well recognized and articulated.

The Bhagavad-Gita tried to mollify a bad situation that was getting worse by clarifying that the four-way classification was indeed based on ones merit or excellence (guna) and functions (karma).But that sadly remained an academic placation.

2.3. A person in the Mahabharata society derived his position and rights by virtue of being a member of a given caste-group rather than as an individual on the strength of his merits. The questions of his status, his inheritance as also those of his offspring were decided in the context of his sub caste-group. The matter would usually be fairly simple and well laid out when both the husband and wife belonged to the same caste-group. But, it would get rather complicated when man and woman came from different caste-groups.

The then Law-givers went into great lengths to classify and sub-classify the offspring of such inter-caste marriages, in order to determine their status and rights. There were, of course, supplementary questions that begged for answers. Such uncomfortable questions arose in the context of those born out of the wedlock or of those born to a re-married woman and such other complications.

Towards the end of the epic, in the Shanthi-parva, Yudhistira the newly anointed king queries, among other things, the wise old Bhishma strung on a bed of arrows: “We hear of many disputes that arise out of the question of the sons. Do thou solve the doubt for us, who are bewildered “. Bhishma then initially lists out nine types or categories of sons who then are classified as those: (i) sons who belong to the family and have also the right to inherit; (ii) and as those sons who only belong to the family, but have not the right to inherit. Bhishma then goes on to list twelve other types of sons who are born out of man and woman who belong to different castes.

Of these the first six are termed apadh-vamsaja (three types born of a Brahman with Kshatriya, Vaishya or Sudra woman; two types born of a Kshatriya with Vaishya or Sudra woman; and one type born of a Vaishya with a Sudra woman); and six other types termed apasada (three types born of Sudra with Brahman, Kshatriya or Vaishya woman; two types born of a Vaishya with Brahman or Kshatriya woman; and, one type born of a Kshatriya with Brahman woman). Apart from these there are also other categories born outside –wedlock with or the without the express approval of the husband; sons of re-married woman; sons born to widows, sons born to virgins; as also those sons adopted, sons gifted, adopted from other parents; those abandoned infants picked up from the street and whose parentage is not known; and, sons bought for price etc. The rights of inheritance or otherwise, the caste and the social status of each category are also listed.

2.4. The later text the Arthasastra (dated around the third century BCE) fairly well enumerated the classifications based on the distinction whether the male was of a superior caste (anuloma) or whether the female was of a superior caste (pratiloma). Those were again sub-classified depending on how far a spouse ranked below the other.

For instance, the son begotten by a Brahman from a Kshatriya woman was a murddhabhishikta (an anantaráputráha or savarna marriage); a son begotten by a Brahman from a Vaishya woman was ambastha; and a son begotten by a Brahman from a Sudra woman was a Nisháda or Párasava. Similar classifications were provided for Kshatriyas and Vaishyas who married below their caste-rank .The rights of those offsprings diminished progressively.

[Chapter VII : “Distinction between Sons” in the section of “Division of Inheritance” in Book III, “Concerning law” of the Arthasástra of Kautilya.]

KAZ03.7.20/ brāhmaṇa.kṣatriyayor anantarā.putrāḥ savarṇāḥ, eka.antarā asavarṇāḥ //

KAZ03.7.21/ brāhmaṇasya vaiśyāyām ambaṣṭhaḥ, śūdrāyāṃ niṣādaḥ pāraśavo vā //

KAZ03.7.22/ kṣatriyasya śūdrāyām ugraḥ //

KAZ03.7.23/ śūdra eva vaiśyasya //

KAZ03.7.24/ savarṇāsu ca^eṣām acarita.vratebhyo jātā vrātyāḥ //

KAZ03.7.25/ ity anulomāḥ //

KAZ03.7.26/ śūdrād āyogava.kṣatta.caṇḍālāḥ //

KAZ03.7.27/ vaiśyān māgadha.vaidehakau //

KAZ03.7.28/ kṣatriyāt sūtaḥ //

2.5. Under a similar classification, the offspring begotten by a Brahman woman from a Kshatriya male was called Suta; her offspring from a Vaishya male was Videha; and her offspring from a Sudra was a Sudra. Similar sub-classifications were provided for Kashatriya and Vaishya women marring below their caste-rank. The Artha-sastra said, the sons begotten by a Súdra on women of higher castes were Ayogava, Kshatta, and Chandála. The term Kshatta, however, had earlier had a totally different connotation in the Mahabharata times, as we shall see in the next paragraph.

2.6. The sub-classifications briefly outlined above might look rather pedantic and obtuse. But, they had the bite to inject pain and humiliation into the lives of many virtuous but underprivileged persons in the Mahabharata tale.

The caste issue was a tragedy that not merely marred the lives of some its characters but it also turned into a bane and curse on the countless generations that followed.

[On the question of caste determining ones position in the Mahabharata society, there is an alternate view. It points out that Krishna , a Yadava was revered as a divine person; Satyavathi , a fisher-woman, could become a Queen; Vyasa , a half-breed, was the most respected Sage; and , Karna the son of a Suta , was appointed a King. Thus , it was not merely the caste; but it was ones merit that truly mattered.]

**

The Sutas

3.1. The offspring born of a Brahman woman from her Kshatriya husband was labeled a Suta. You come across a number of Sutas in the Mahabharata story; and most of them played crucial but thankless roles; and endured humiliation and pain.

The terms Suta and Suti or Sauti (son of suta) appear to have gained currency at a later time. For instance Yadu the ancestor of the Yadavas in which linage Krishna and Balarama descended was the son of the legendry King Yayathi (Kshatriya) and Devayani (daughter of the Brahman Guru Shukracharya) . Yadu was technically a Suta – as per the norms that later came into use ; but, Yadu was never addressed as a Suta , nor his descendents were termed Sauti.

3.2. The Sutas of Mahabharata traditionally served the kings and functioned as their charioteers (Rathakára); and as those who reported events, narrated stories, read out massages and took out messages from the king. They were also the repositories of the lore and genealogies of the Royal dynasties. The Sutas in general, were confidants of the king, at times his advisers; and moved closely with the king while he was in his living quarters (anthahpura).

But Sutas were never treated as friends of the king; nor were they provided living quarters in the palace per se .There are hardly any instances of Sutas being offered Brahman or Kshatriya brides, in marriage. The Sutas married among themselves; and followed the customs and avocations their ancestors.

3.3. To mention some of the Sutas, Sanjaya (the son of Gavalgana who also was in the service of the kings of Hasthinapur) the charioteer who was temporarily bestowed long-distance-vision of the happenings on the battle fields of Kurukshetra; and who narrated the war events to his blind king Dhritarashtra was a Suta.

Ugrashrava (meaning one blessed with high or loud voice) was often addressed as Sauti(the son of a Suta). He was the son of a Suta Lomaharsha or Lomaharshana or Romaharshana(because of his delightful and thrilling manner of narration). Lomaharshana Suta is the one who narrated the Srimad Bhagavata purana to the sage Saunaka and other at Naimsaranya – a forest named after the king of the yore Nimi. His son Ugrashrava recited in verse the entire epic story of Mahabharata, also to the sages in Naimsaranya.Ugrashrava was revered as one well versed in all puranas.

While Ramayana is sublime poetry, Mahabharata is the vigor of the spoken language studded with extensive use of similes, metaphors and symbolic allegories. It portrays the living language of the times with blessings, curses, oaths, sane advise, humour, ranting , heart wrenching shrieks , sagely preaching etc conveying every shade of human emotions.

The beauty of its language is in its oral rendering. Even today, groups of devote listeners love to gather around a narrator to listen in divine fervor to the ancient tales the glory of their heroes and heroines, rather than read the epic.

[Incidentally, another explanation for Naimsaranya is the time-less zone of peace: nimisha = unit of time; naimisha = timeless; aranya = a zone free from conflicts (ranya) or a zone of peace]

3.4. Kichaka, the half-brother of Sudeshna the queen of the Matsya king Virata, was also a Suta. In the entire sordid story of Mahabharata, Kichaka perhaps was the only Suta who had his way and who enjoyed his style of life. But, he lost his head, overreached himself and eventually met a rather an ignoble end.

Karna was a Suta-putra, the son of a Suta, which meant he was inferior to a Suta.

.…And the others

4.1. There were others of a similar class; such as Vaitalikas who called out aloud the hour of the day or night, and also keep track of genealogy (vamsavali-kirtaka); and, the Vandi –Magadhas who recite the glory , the titles and aceivements of the kings ; herald their arrival into the Royal Court and recite blessings. Most of them, just as the Sutas, were men of virtue, wisdom and valor; and they served their masters with devotion. They were, however, denied the recognition they deserved, mainly because of their birth antecedents. The ponderous Mahabharata hides in its bosom countless stories of unspoken pain, sorrow and humiliation. That is one of the tragedies of its sordid tale.

4.2. For instance; the blind king Dhritarashtra fathered a son named Yuyutsu, from his servant maid, a Vaishya woman. Yuyutsu was thus technically a mahishya (the son of a Kshatriya father and a vaishya mother); and, he was acknowledged as such in public. He was younger to Duryodhana and elder to Dushyasana; but was snubbed and neglected because he was a mahishyaand not a full-blooded prince. Yuyutsu was the only one, in the crowded court-hall, that had the courage and sanity to disapprove Duryodhana’s heinous behavior and the humiliation meted out to Draupadi, the kula-vadha. And later when the war looked imminent, he pleaded in vain withDuryodhana to make peace with the Pandavas; and to avoid needless bloodshed. When the war did eventually happen, Yuyutsu chose to fight along with the Pandavas against his step brothers. Yuyutsu was the only Kaurava that survived the internecine bloodbath. Yet, Yuyutsu the mahishya could not succeed to the Kaurava throne ; while Arjuna’s grandson Parikshit was made the king of Hasthinapur; and Krishna’s grandson Vajra was made the king of the other remaining half of the kingdom , Indraprastha . Yuyutsu was made only a prime minister of Indraprastha on the eve of Pandava’s departure from the earthly world.

4.3. You mentioned Vidura. He was not a Suta. He was repeatedly addressed by all as Kshatta; perhaps meaning a kshetraja a son born to a woman from a man (other than the husband) appointed to impregnate her. Vidura’s mother was a servant maid to the queen while his father was Vyasa, a sage. The term Kshatta, centuries later, acquired a totally different meaning in the Artha Sastra, where Kshatta meant a son begotten by a Súdra male from a women of higher caste.

Among the three de-jure sons of Vichitravirya, only Vidura was wise, and sound both in body and mind. He could not however be treated as equal to Pandu and Dhritarashtra born of Kshatriya mothers. Bhishma, the grand-old-man, brought brides from Kshatriya families for Pandu and Dhritarashtra. But for Vidura he got the daughter of king Devaka ‘begotten upon a Sudra wife’. Her name was Parshavya. She was technically an ugra (begotten by a Kshatriya on a Súdra woman). It is said ‘Vidura begot upon her many children like unto himself in accomplishments’. His no other family details are easily available.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m01/m01115.htm

Dhritarashtra seemed to have affection towards Vidura, but he ordered him about, and often dismissed him rudely. Vidura was for all purposes a half-brother of the king but could claim neither right nor respect.

Vidura was a person of great wisdom, he often advised the King even on matters relating to the State. But none of the Kauravas, including the blind king, cared to listen to him or follow his counsel. His role was unenviable and frustrating. He knew the right way; but had to watch a helpless onlooker when everything was going wrong hurling down towards death and destruction.

When all his attempts to avoid the war (including the sane advice from the boy genius saint Sanathkumara) ended in failure, Vidura withdrew from all state affairs, stayed aloof and did not participate in the war .

After the end of the ruinous war Vidura out of loyalty and love for his step brother retreated into the forests along with Dhritarashtra, Gandhari and Kunti; and eventually gave up his coils in forest fire.

4.5. Karna was a suta-putra, the son of a Suta, which meant he was below the rank of Suta. Because, Suta was born to a Kashatriya and a Brahman; and the Suta-putra was the offspring of Suta parents. Karna, all his life endured taunts, insults and humiliation for being a Suta-putra. That hurt him grievously.

But it was the rejection and insult thrown in his face by Draupadi, at her swayamvara that hurt him most. Draupadi, yajnaseni the flashing one born out of fire, insisted on being declared a Veeryashulka, a bride to be won by the worthiest and the very best; and she vehemently protested against the lowborn Suta-putra entering the contest.That pain and humiliation burned deep into his soul searing his self esteem. It was like a raw wound that never would heal. Karna later in his life did not let go a slightest opportunity to hurt and humiliate Draupadi. He shamefacedly participated in the outrage mounted on her modesty. That sowed the seeds of destruction of the Kaurava clan.

Duryodhana treated Karna as a bosom friend. He provided him an identity, recognition and esteem by making him the King of Anga. But, he would not offer him a Kshatriya princess in marriage. Karna was a good friend but he fell short of being a Kinsman.

As the war began, Bhishma the commander-in-chief of the kaurava armies ranked Karna as an Ardha-rathi which was inferior to the ranks of Maha-rathi, Ati-rathi and Rathi.

[A warrior capable of fighting 60,000 warriors simultaneously; having mastery over all forms of weapons and combat skills was termed Maharathi. while a warrior capable of contending with 10,000 warriors simultaneously was an Atirathi].

Though Karna by then was universally recognized as a Maha-rathin, Bhishma degraded him to half of a capable warrior, perhaps just to spite the Sutaja. Karna understandably was deeply hurt and insulted; and he withdrew from the battle till Bhishma fell

Towards the end of the war, Shalya the king of Madra (the maternal uncle of Nakula and Sahadeva) a skilled horseman was tricked by Duryodhana into being Karna’s charioteer. Shalya suppressed his anger at being cheated to act as a charioteer to a Suta-putra; but did upset Karna and dampen his fighting spirit, in order to ensure Karna’s defeat.

The Karna – Shalya rancorous repartee is not in high flowing language and in rather bad taste; it also refers to slang and abusive oaths and cusses of the women of Madra region (Punjab – Sialkot area)-malaṃ pṛthivyā bāhlīkāḥ strīṇāṃ madrastriyo malam – 08,030.068

All those heaps of insults, treachery and conspiracy of fate did eventually burnt a deep hole in his heart; and he lost the will to live.

Adhiratha

5.1. Adhiratha, the foster father of karna, was a Suta. His father was a Kshatriya king and his mother a Brahman. Adhiratha was born of Satyakarma (satkarma) the king of Anga (a region around the present-day Bhagalpur in Bihar) from his Brahman wife.

Who was this Satyakarman or Satyakarma or Satkarma?

5.2. Satyakarma of Chandravamsha (Lunar dynasty) was the son of Dhrtavrata; who was the son of Druthi who in turn was the son of Vijaya. And, Vijaya was the son of Bruhanmana from his second wife Satya. Bruhanmana was the son of Jayadratha by his wife Sambhuti.

The Ninth Canto, Twenty-third Chapter, of the Srimad-Bhagavata, entitled “The Dynasties of the Sons of Yayati” provides a very long list of names tracing Satkarma to Yayathi. http://bvml.org/books/SB/09/23.html

5.2. “The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Puranas” by Parmeshwaranand Swami, in a relatively brief form traces the genealogy of Sathyakarman to the ancient King Yayathi:

Yayathi – Anudruhya –Sabhanara – Kalanara – Srnjaya – Titiksha – Kasadhrta – Homa – Sutapas.

From Sutapas and his wife Sateshna was born Bali who had seven sons: Anga, Kalinga, Sushma, Kandra, Vanga, Adrupa and Anasbhu.

Anga was the progenitor of a linage. To Anga were born several sons including the following: Dadhivrata, Raviratha, Dharmaratha, Chitraratha, Sathyaratha, Lomapada, Chaturanga, Pruthu, Haryanga and Bhadraratha.

Bhadraratha had following sons: Jayadratha, Bhadramanas, Vijaya, Dhruthi, Dhartavrata and Satyakarman.

Satyakarman was the father of Adhiratha who was the foster father of Karna; and Karna was the father of Vrasasena.

5.3. It appears that Satyakarma had sons by his Kshatriya wife; and they succeeded him as kings of Anga. His other son Adhiratha begotten from his Brahman wife was a Suta who, as per the tradition, became a charioteer. It is likely that Adhiratha was at one time in the employ of king Dhritharastra of Hasthinapur, as his charioteer.

5.4. Adhiratha (at times called Surasena) was married to Radha, another Suta offspring. At the time Adhiratha and Radha found the baby- Karna in a box set adrift on the Ganga, they had no children, yet. But, after he and Radha adopted Karna as their son, they were blessed with four sons: Shatruntapa, Dhruma, Vrtharatha and Vipata.

In the later years, Shatruntapa died at the hands of Arjuna during the Uttrara-go-grahana misadventure on the outskirts of the Viratanagara the capital of Matsya Desha. The other three died in the Kurukshetra war during the days when Acharya Drona was commanding the Kaurava forces. Dhruma and Vrtharatha were killed by Bhima; and Vipata was killed by Arjuna.

[I did not come across a connection between Vidura and his wife with Adhiratha and his wife Radha.

Vidura’s wife was Parasavya; and Adhiratha’s wife as you said was Radha.

Adhiratha was a Suta while Vidura was a kshatta born of Sudra woman from Vyasa. Vidura was also said to be a kshetraja one born of a male appointed to impregnate the female.

The name Adhiratha is not to be mistaken for the term Ati-rathin a classification of warriors based on their supposed capabilities and valour. ]

*

6. Biographic details of Karna

6.1. The biographic details of karna are interspersed in bits and pieces at four different places in the Mahabharata : in Adi-Parva – SECTION CXI (Sambhava Parva); in Vana Parva from SECTION CCCI to SECTION CCCVIII ;in Udyoga Parva SECTION CXLI ; and , in :SANTI PARVA – SECTION I through to SECTION VI.[The references relate to sections in Shri Kesari Mohan Ganguli’s monumental translation The Mahabharata of Krishna-dwaipayana Vyasa]

6.2. The first reference briefly mentions the birth antecedents and infancy of Karna. The second one in Vana Parva which follows Karna’s dream-conversation with Surya, his parent, warning against hoax requests exploiting his generosity is fairly detailed .It covers the early story of Kunti (Prutha) too: about her maidenhood in the household of Kuntibhoja her foster parent; serving the irascible sage Durvasa; helpless encounter with the Sun god; begetting out-of-wedlock a most wonderful looking adorable bright son, and out of sheer shame and fear of sullying the fair-name of her family, tearfully abandoning her firstborn setting him adrift the Aswa River. The narration continues along with the casket carrying the new born floating along the Aswa River then on to the Charmanvati (Chambal), the Yamuna and finally joining the River Ganga where Adhiratha and his wife Radha find the baby, joyously bring the little boy home, name him as Vasusena and bring him up most lovingly. Kunti, all the time, through her spies keeps track of her son growing up in the Sutha family. In this section, it is said, Adhiratha the foster father later sends Karna to Hastnapur for education under the famous teacher Drona. The story in this section concludes with Karna gifting away his invincible Kavacha (shield) and Kundala (earrings) to Indra in disguise, despite Surya‘s warning and sane counsel…

the election of Karn by Mukesh singh

6.3. The third narration which occurs in Udyoga Parva is a brief one , wherein Karna in conversation with Krishna , who tried to entice him, reminiscences his early childhood lovingly enveloped in the care and affection of the Suta family and particularly of his mother Radha. He fondly recalls his early upbringing and education provided by his foster family: “When also I attained to youth, I married wives according to his selections. Through them have been born my sons and grandsons, O Janardana. My heart also, O Krishna, and all the bonds of affection and love, are fixed on them. From joy or fear. O Govinda. I cannot venture to destroy those bonds even for the sake of the whole earth or heaps of gold. “

It was a very mature, restrained and almost a sagely reply. He speaks with a great sense of responsibility and commitment to his values in life, hiding his deep sense of sorrow and betrayal behind calm courage that almost borders on suicidal detachment.

6.4. The fourth narration in Shanthi Parva occurs after the death of Karna. This occurs at the commencement of Shanthi Parva soon after the conclusion of the internecine bloodbath at the Kurukshetra war. Yudhistira on learning from Kunti, Karna’s identity is distraught and heartbroken. He laments over the cruelty and irony of fate that conspired forcing him to kill his elder brother Karna for the sake of reclaiming the lost kingdom. “I desire to hear everything from thee, O holy one!’ he cried out in anguish. At the request of Yudhistira, Sage Narada recounts the tale of Karna from his birth, childhood, education and his deeds and misdeeds in company of his friend and benefactor Duryodhana. This narration covers a little more ground than the earlier two; and also speaks of Karna’s adult life in service of Duryodhana. Narada explains the wrongs that Karna committed were prompted by his sense of abandonment, loneliness, bitterness and envy of the Pandavas particularly of his rival and challenger Arjuna.

It is this section which mentions that Karna in his early tutelage with Drona approaches the teacher (Drona), in private, requesting to be taught the secret of “the Brahma weapon, with all its mantras and the power of withdrawing it”, for he desired to fight Arjuna. Drona of course promptly refuses saying ‘None but a Brahmana, who has duly observed all vows, should be acquainted with the Brahma weapon, or a Kshatriya that has practiced austere penances, and no other.’ Thereafter Karna promptly takes leave of Drona and proceeded without delay to Parasurama then residing on the Mahendra mountains introducing himself as ‘I am a Brahmana of Bhrigu’s race.’ Karna thereafter spent perhaps the happiest days of his life acquiring all the knowledge, skills and all the weapons; becoming a great favorite of his teacher, the gods, the Gandharvas, and the Rakshasas. That happiness was short-lived. Soon two tragedies and two curses struck him. Please check for details the links provided above.

[The Karna – Parasurama episode could obviously have occurred between the period of Karna’s early education with Drona (at the instance of Adhiratha the foster parent of Karna) and the game-show at Hastinapura at which the bright and belligerent Karna was anointed the King of the Anga province. Towards the end of the game-show Adiratha enters the arena and blesses his son Karna; and the whole world thereafter comes to recognize Karna as the son of Adhiratha the Suta.

Karna’s education with Parasurama was apparently before he was appointed the King of Anga-Desha and not later. Because, after that happening there was no way that Karna famed as the friend and confidant of the prince of Hastinapura could have gone to Parasurama in undercover calling himself as ‘I am a Brahmana of Bhrigu’s race.’]

Karna – your questions

7.1. The childless couple Adhiratha and Radha found the enchanting baby Karna in a box filled with gold-jewels, drifting on the waves of the Ganga. They were overwhelmed with joy and adopted the new found baby as their son.

Adhiratha took away the box from the water-side, and opened it by means of instruments. And then he beheld a boy resembling the morning Sun. And the infant was furnished with golden mail, and looked exceedingly beautiful with a face decked in ear-rings. And thereupon the charioteer, together with his wife, was struck with such astonishment that their eyes expanded in wonder. And taking the infant on his lap, Adhiratha said unto his wife, ‘Ever since I was born, O timid lady, I had never seen such a wonder. This child that hath come to us must be of celestial birth. Surely, sonless as I am, it is the gods that have sent him unto me!’

And after Karna’s adoption, Adhiratha had other sons begotten by himself. And seeing the child furnished with bright mail and golden ear-rings, the twice-born ones named him Vasusena. And thus did that child endued with great splendour and immeasurable prowess became the son of the charioteer, and came to be known as Vasusena and Vrisha.

[ http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m03/m03307.htm ]

7.2. Karna recounts to Krishna (in Udyoga-parva) his early child hood. He speaks with great warmth about his foster parents; fondly recalling the love they showered on him narrates how they doted on him, how they brought him up in the Suta tradition and how they got him married to a Suta bride.

As soon as he beheld me, took me to his home, and from her affection for me, Radha’s breasts were filled with milk that very day, and she cleansed my urine and evacuations.

So also Adhiratha of the Suta class regardeth me as a son, and I too, from affection, always regard him as (my) father.

Adhiratha from paternal affection caused all the rites of infancy to be performed on my person, according to the rules prescribed in the scriptures. It is that Adhiratha, again, who caused the name Vasusena to be bestowed upon me by the Brahmanas.

When I attained to youth, I married wives according to his selections.

All my family rites and marriage rites have been performed with the Sutas.

[ http://www.harekrsna.com/sun/editorials/mahabharata/udyoga/mahabharata142.htm ]

Karna retained loyalty and loving relationship with his foster parents till his death.

7.3. He was initially named Vasusena as he was found with ornaments of gold. He was Karna because he was adorned with most precious and glowing ear-ornaments. His other names were: Radheya (the son of Radha, his foster mother); Vrisha; Vrikartana (the Sun); Bhanuja (Sun’s son); Goputra; Vaikarttana (because he gave away the kavacha and earrings he was born with); Angaraja (the king of Anga); Champadhipa (king of Champa, a region along the banks of the Ganga). And of course he was also called Sutaputra,; Sutaja; Kanina( one born to a Kanya an unmarried girl); and Bhishma deliberately insulted Karna by labeling him an Ardha-rathi , one who has only half the fighting capacity of a valiant warrior. That was the unkindest cut of all.

7.4. Karna’s wife is named as Vrushali, a Suta (The names such as Prabhavathi and Supriya are also mentioned as the other wives of Karna, But, Kesari Mohan Ganguli’s monumental translation “The Mahabharata of Krishna-dwaipayana Vyasa” does not seem to mention those names).It is very likely that Karna had more than one wife. Karna mentioned to Krishna: “When I attained to youth, I married wives according to his (Adhiratha) selections”.

7.5. As regards his sons, Karna had several sons and the names of nine of his sons are mentioned. Of the nine, only one survived the Kurukshetra war.

Vrasasena; Sudhama; Shatrunjaya; Dvipata; Sushena; Satyasea; Chitrasena; Susharma(Banasena); and Vrishakethu .

Sudhama died in the melee that followed Draupadi’s swayamvara. Shatrunjaya and Dvipata died in the Kurukshetra war at the hands of Arjuna during the days when Drona commanded the Kaurava forces. Sushena was killed in the war by Bhima. Satyasena, Chitrasena and Susharma died in the hands of Nakula. Karna’s eldest son Vrasasena died during the last days of the war when Karna was the commanded the battle forces. Vrasasena was killed by Arjuna.

Vrushasena’s death is described in all its gruesome detail:

Arjuna rubbed the string of his bow and took aim at Vrishasena in that battle, and sped, O king, a number of shafts for the slaughter of Karna’s son. The diadem-decked Arjuna then, fearlessly and with great force, pierced Vrishasena with ten shafts in all his vital limbs. With four fierce razor-headed arrows he cut off Vrishasena’s bow and two arms and head. Struck with Partha’s shafts, the son of Karna, deprived of arms and head, fell down on the earth from his car, like a gigantic shala adorned with flowers falling down from a mountain summit. Beholding his son, thus struck with arrows, fall down from his vehicle, the Suta’s son Karna, endued with great activity and scorched with grief on account of the death of his son, quickly proceeded on his car, inspired with wrath, against the car of the diadem-decked Partha.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m08/m08085.htm

Some versions mention that a son of Karna died in the battle with Abhimanyu. But, his name is not given.

Vrishakethu was the only son of Karna that survived the horrific slaughter called Kurukshetra war. He later came under the patronage of the Pandavas. During the campaign that preceded the Ashvamedha –yaga, Vrishakethu accompanied Arjuna and participated in the battles with Sudhava and Babruvahana. During that campaign Vrishakethu married the daughter of king Yavanatha (perhaps a king of the western regions). It is said, Arjuna developed great affection for Vrishakethu, his nephew.

*

76. As regards Karna’s tragic end, so much has been written about those heart wrenching scenes; one can hardly say any more. To put it simply:

The seventeenth day of the war began fairly well for Karna. In the early part of the day, Karna defeated Bhima and Yudhisthira, but spared their lives. Later in the day Karna resumed his duel with Arjuna. During their duel, Karna’s chariot wheel got struck in the mud and Karna asked for a pause. Krishna reminded Arjuna about Karna’s ruthlessness unto Abhimanyu while he was similarly stranded without chariot and weapons. Hearing his son’s fate, the enraged Arjuna shot his arrow and decapitated Karna.

7.7. All his life, Karna carried in his heart the searing raw wound of unrecognized greatness. The many insults and humiliations he had to endure were because of his supposedly low birth. That led him to a quest for recognition and respect from his fellow beings as the mightiest Kshatriya of his times. His feats of great heroism, his bitter rivalry with Arjuna were fueled mainly by that ambition. “I was born for valour; I was born to achieve glory” (43.6). Karna was the blazing but the sinking Sun among the dark clouds of the Kauravas.

Vyasa mourns Karna: “The arrow raved Karna-Sun, after scorching its enemies, was forced to set by valiant Arjuna –kala” (91.62)

Kunti praises her first-born, her dead son as “A hero, ear-ringed, armored, and splendid like the Sun”; ”He was all dazzle like molten gold , like fire , like the Sun”; “ To whoever asked he gave, he never said no..Always the giver” (09,004.034)

a śūrāṇām āryavṛttānāṃ saṃgrāmeṣv anivartinām / dhīmatāṃ satyasaṃdhānāṃ sarveṣāṃ kratuyājinām //09,004.034 //

7.8. The lives of the Sutas and of the similar other ones are filled with unspoken pain and neglect. When you come to think of it, you realize that none of the major characters – men and women even of royal blood – had a happy and peaceful life. Their lives too were filled with struggle, sorrow and frustration. Each one – virtuous or otherwise- was disillusioned, in the end.

7.9. Vyasa concludes the epic imploring all humans to adhere to Dharma and to practice Dharma. And, for some reason, the Great Vyasa in desperation pours out his frustration, screaming aloud:

“With raised hands, I shout at the top of my voice; but alas, no one hears my words which can give them Supreme Peace, Joy and Eternal Bliss. One can attain wealth and all objects of desire through Dharma (righteousness). Why do not people practice Dharma? One should not abandon Dharma at any cost, even at the risk of his life. One should not relinquish Dharma out of passion or fear or covetousness or for the sake of preserving one’s life….”

ūrdhvabāhur viraumy eṣa na ca kaś cic chṛṇoti me / dharmād arthaś ca kāmaś ca sa kimarthaṃ na sevyate / na jātu kāmān na bhayān na lobhād; dharmaṃ tyajej jīvitasyāpi hetoḥ/ nityo dharmaḥ sukhaduḥkhe tv anitye; jīvo nityo hetur asya tv anityaḥ – MBh. 8,005.049-50

***

Trust this helps. .Please let me know. Regards

References and sources:

The Mahabharata of Krishna-dwaipayana Vyasa by Shri Kesari Mohan Ganguli

Purana Bharata Kosha by shri Yagnanarayana Udupa

The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Puranas by Parmeshwaranand Swami

The Mahabharata of Vyasa By Prof. P. Lal

Pictures are from internet

http://bvml.org/books/SB/09/23.html

http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m05/m05141.htm

http://www.dharmakshetra.com/literature/puranas/garuda.html

http://www.swaveda.com/elibrary.php?id=85&action=show&type=etext

]

]

Buddhist Yama of Tibet

Buddhist Yama of Tibet

.

.

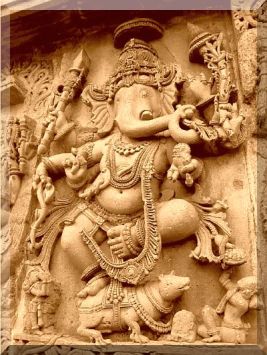

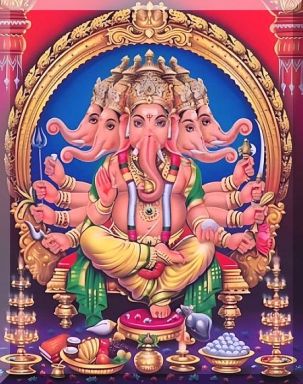

Kshetrapalas are basically the folk guardian deities who are very popular in village cults. They are entrusted with the task of safe guarding a Kshetra (a village, a field or a temple) against dangers coming from all the eight spatial directions. In the villages of South India Kshetrapalas are placed in small temples or in open spaces outside of the village..Sometimes in the village open- courtyards blocks of stone are designated and worshipped as Kshetrapala. They are offered worship on occasions of important community celebrations.

Kshetrapalas are basically the folk guardian deities who are very popular in village cults. They are entrusted with the task of safe guarding a Kshetra (a village, a field or a temple) against dangers coming from all the eight spatial directions. In the villages of South India Kshetrapalas are placed in small temples or in open spaces outside of the village..Sometimes in the village open- courtyards blocks of stone are designated and worshipped as Kshetrapala. They are offered worship on occasions of important community celebrations.