Nrtta, Natya and Nrtya

Intro.

As it has very often been said ; the Natyashastra is the earliest available text of Indian Dancing traditions. It combines in itself the fundamentals of the principles, practices and techniques of Dance. it thus serves as the principal text of the Dance. And, therefore, the influence exerted by it on the growth and development of all Dance-forms, has been deep and vast. The Natyashastra, an authoritative text to which the Masters and learners alike turn to , seeking instructions, guidance, and inspiration , is central to any discussion on classical Dance. And, therefore, no discussion on classical Dance is complete without referring to the concepts of the Natyashastra.

[Having said that; let me also mention that in the context of Dance , as it is practiced in the present day, besides Natyashastra , several other texts are followed. The Natyashastra provides the earliest theoretical framework; but, the practice of Dance and the techniques of dancing were molded and improved upon by many texts of the later periods. What we have today is the culmination of several textual traditions, their recommended practices, and some innovative features. We shall come to those aspects later in the series.]

Because of the position that Natyashastra occupies in the evolution of the Arts and its forms, it would help to try to understand the early concepts and their relationships to Dance. And, thereafter, we may follow the unfolding and transformation of those concepts acquiring different meanings and applications; as also the emergence of new terms and art-forms, during the later times.

In that context, we may, in particular, discuss the three terms; their derivation; their manifestation and transformation; as also the mutual relations among the three. In the process, we may also look at the related concepts; and their evolution over the centuries. The three terms that I am referring to are the Nrtta, Natya and Nrtya, which are fundamental to most of the Dance formats.

*

As regards the other texts that discuss the theories, practices and techniques of Dancing, there are no significant works between the period of Bharata and that of Abhinavagupta and Dhananjaya (eleventh century). Even if any were there, none has come down to us. But during this period, the dance and its concepts had changed significantly. And, the manuscript editions of the Natyashastra had also undergone alterations.

Over the different periods, the concepts of Natyashastra, along with that of its basic terms such as Nrtta, Natya etc., came to be interpreted in number of amazingly different ways, depending, largely, upon the attitudes and the approach of the authors coming from diverse backgrounds and following varied regional cultural practices. It is a labyrinth, a virtual maze, in which one can easily get lost.

It would, therefore, hopefully, make sense if we try to understand these terms in the context of each period that spans the course of the long history of Dancing in India, instead of trying to take an overall or summary view.

In the following pages, let us try to understand these terms and their applications in relation to the concepts and the techniques of dancing, as it emerged in various stages, during the three phases of Indian Art history: the period of the Natyashastra of Bharata; the theories and commentaries by the authors of the medieval period; and, dance as practiced in the present-day.

Before we get into the specifics, let’s briefly talk about Dance in general, within the context of Natyashastra.

Bharata’s Natyashastra represents the first known stage of Indian Art-history where the diverse elements of arts, literature, music, dance, stage management and cosmetics etc., combined harmoniously, to fruitfully produce an enjoyable play.

It is quite possible that the authors prior to the time of Bharata did speak of Dance; its forms and practices. But, it was, primarily, Bharata who recognized the communicative power of Dance; and, laid down its concepts.

Bharata described what he considered to be the most cultivated dance styles, which formed the core of the dominant art-practice (prayoga) in his time, the Drama.

The framework within which Bharata describes Dance is, largely, related to Drama. And, his primary interest seemed to be to explore the ways to enhance the beauty of a dramatic presentation. Thus, Dance in association with music was treated as an ornamental overlay upon Drama.

As Nandikesvara said; the Dance should have songs (gitam). And, the song must be sung, displaying (pradarshayet) the meaning (Artha) and emotions (Bhavam) of the lyrics through the gestures of the hands (hastenatha); shown through the eyes (chakshuryo darshaved); and, in tune with rhythm and corresponding foot-work (padabhyam talam-achareth).

Asyena alambaved gitam, hastena artha pradarshayet/chakshuryo darshaved bhavam, padabhyam talam-achareth (Ab.Da.36)

Dance, at that stage, was an ancillary part (Anga) or one of the ingredients that lent elegance and grace to theatrical performance; and, it was not yet an independent art-form, by itself. Bharata , at that stage, is credited with devising a more creative Dance-form , which was adorned with elegant, evocative and graceful body-movements; performed in unison with attractive rhythm and enthralling music; in order to effectively interpret and illustrate the lyrics of a song; and, also to depict the emotional content of a dramatic sequence.But, he had not assigned it a name.

It was only in the later times, when the concepts and descriptions provided by Bharata were adopted and improved upon, that Dance gained the status of a self-regulating, independent specialized form of art, as Nrtya.

*

The scholars opine that in the evolution of Dance, first comes Nrtta; then Natya; and, later Nrtya appeared. Here, Nrtta is said to be pure dance; while Nrtya emerged when Abhinayas of four types (Angika; Vachika; Sattvika; and Aharya) were combined with Nrtta. And, Natya included both these (Nrtta and Nrtya), even while the speech and the songs remained prominent. Thus, Natya comprises all the three features – Dance, music and speech (song) – which are very essential for the production and enactment of Drama.

To put the entire series of developments, in the context of Natyashastra, in a summary form:

Nrtta, as described in Natyashastra, had been in practice even during the very ancient times. The Nrtta, according to Bharata, was a dance form created by Shiva; and, which, he taught to his disciple Tandu. It seems to have been older than Natya

Natya too goes back to the very distant past. Even by the time of Bharata, say by about the fourth to second century BCE, Natya was already a highly developed and accomplished Art. It was regarded as the best; and, also as the culmination of all Art forms (Gitam, Vadyam, Nrttam trayam natya dharmica).

Though Nrtta was older, Natya was not derived from it. Both the Nrtta and the Natya had independent origins; and, developed independent of each other. And, in the later times too, the two have been distinct; and, run on parallel lines.

It was during Bharata’s time that Nrtta was integrated into Natya. Even though the two came together, they never merged into each other. And, up to the present-day they have retained their identity; and, run parallel in ways peculiar to them. (Even in a Bharatanatya performance the treatment and presentation of the Nrtta is different from that of the rest.)

By combining Nrtta, the pure Dance, with the Abhinaya of Natya, a new form of Dance viz., the Nrtya came into being. Bharata is credited with this creative, innovative act of bringing together two of the most enjoyable Art forms (Bhartopajanaka). But, it developed to its full extant only after the time of Bharata.

But, at the time of Bharata, that resultant new-art was not assigned a separate name; nor was it then classified into Tandava and Lasya types. In fact, the terms Nrtya and Lasya do not appear either in the Natyashastra or in its early commentaries. It was only during the later times that Nrtya gained an independent recognition as an expressive, eloquent representational Art, which projects human experiences, with amazing fluidity and grace.

Nrtya, a blend of two well studied, well developed and well codified Art forms – the dance of Nrtta and Abhinayas of Natya – over a period, advanced vibrantly, imbibing on its way numerous novel features; and, soon became hugely popular among all classes of the society. It gained recognition as the most delightful Art-form; and in particular, as the most admired phrase or form of Dance.

With this general backdrop, let’s go further.

A. Nrtta in Natyasahastra

Nrtta

Initially, Bharata, in the fourth Chapter of the Natyashastra, titled Tandava Lakshanam, deals with the Dance. The term that he used to denote Dance was Nrtta (pure dancing or limb movements, not associated with any particular emotion, Bhava).

The Nrtta comprised two varieties of Dances (Nrtta-prayoga) : The Tandava and Sukumara. The Tandava was not necessarily aggressive; nor danced only by men. And, the gentler, graceful form of dance was Sukumara-prayoga.

And, in the context of Drama, both of these were said to refer to the physical structure of dance movements. And, both were performed during the preliminaries ,i.e., before the commencement of the play – Purvaranga – while offering prayers to the deities, Deva-stuti ; and, not in the drama per se.

Mayāpīdam smṛtaṃ nṛttaṃ sandhyākāleṣu Nṛtttā । nānā karaṇa saṃyuktai raṅga hārair vibhūṣitam ॥ 4.13॥

Pūrva-raṅga-vidhā avasmiṃstvayā samyak prayojyatām । vardhamāna kayogeṣu gīteṣvāsāriteṣu ca ॥ 4.14॥

The Dance performed during the Purvaranga was accompanied by vocal and instrumental music. It is said; the songs that were sung during the Purvaranga were of the Marga class- sacred, somber and well regulated (Niyata). Such Marga songs were in praise of Shiva (Shiva-stuti). Bharata explains Marga or Gandharva as the Music dear to gods (atyartham iṣṭaṃ devānāṃ), giving great pleasure to Gandharvas; and, therefore it is called Gandharva.

Atyartham iṣṭaṃ devānāṃ tathā prīti-karaṃ punaḥ | gandharvāṇāṃ ca yasmād dhi tasmād gāndharvam ucyate – NS Ch. 28, 9

Almost the entire Chapter Four of Natyashastra is devoted to Nrtta. That is because, the term that Bharata generally used to symbolize Dance, was Nrtta. And, the Nrtta, Bharata said, was created to give expression to beauty and grace

– śobhāṃ prajanayediti Nṛttaṃ pravartitam (NS.4.264).

The Nrtta is visual art. The term Nrtta, in the context of the Natyashastra, is explained by Abhinavagupta as (Angavikshepa), the graceful composition of the limbs – gatram vilasena kshepaha.

The Nrtta stands for pure, abstract and beautiful dance, performed in tune with the rhythm and tempo, to the accompaniment of vocal and instrumental music.

The Nrtta performed during the Purvaranga was not as an auxiliary to Natya. And, therefore, Nrtta was considered to be independent and complete by itself.

Nrtta is described in terms of the motion of the limbs; the beauty of its form; the balanced geometrical structure; creative use of space; and rhythm (time). It gives form to the formless. Here, the body speaks its own language; an expression of the self. It delights the eye with its posture, rhythm and synchronized movements of the dancer’s body.

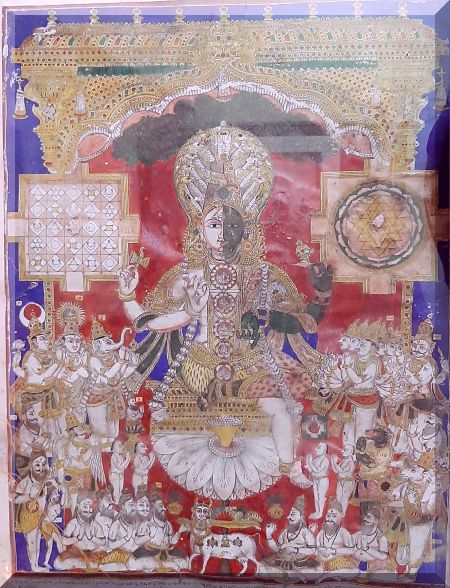

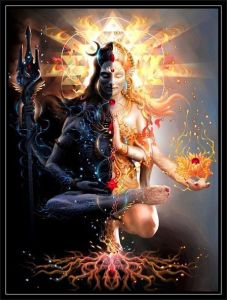

Nrtta is the spontaneous rhythmic movement of different parts of the body (Angas, Upangas and Pratyangas). Nrtta is also associated with the surrounding nature and its beauty. For instance; Shiva does his Nrtta in the evening, before sun set, (Sandhyayam nrtyaha Shamboh) surrounded by the salubrious shining snow peaks of the Himalayas, while he is in the company of Devi Parvathi and his Ganas.

It is said; the sense of Nrtta is ingrained in the nature. For instance; the peacocks burst into simple rhythmic movements at the sight of rain-bearing clouds; and, the waves in the sea swing in ebb and flow as the full moon rises up in a clear cloudless night.

Nrtta is a kind of architecture. It is an Art-form whose life is the beauty of its form. But, Nrtta was not meant for giving forth meaningful expressions. It did not look for a purpose; not even of narrating a theme.

Thus, Nrtta could be understood as a metaphor of Dance made of coordinated movement of hands and feet (Cari and Karana or dance units or postures), in a single graceful flow. Nrtta is useful for its beautiful visual appeal; as that which pleases the eye (Shobha hetuvena).

...

Tandava

And, Tandava is said to be the Nrtta that Shiva taught to his disciple Tandu (Tando rayam Tandavah). It was composed by combining the circular movement of a limb (Recaka) and the sequence of dance movements (Karanas, Angaharas) . It is not clear how these movements were utilized.

The term Tandava could also be understood as Bharata’s term for Nrtta , the Dance (Nrtta-prayoga)

– Nrtta-prayogaḥ sṛṣṭo yaḥ sa Tāṇḍava iti smṛtaḥ. NS.4.261.

And, Tandava is often used as a synonym for Nrtta.

[ Abhinavagupta, in his typical style, provides a totally different sort of explanation to the term Tandava. According to him, the term Tāṇḍava is derived from the sounds like ‘Tando; tam-tam’, produced by the accompanying Damaru shaped drums. It follows the manner, in Grammar (vyākaraṇa), of naming an object, based on the sound it produces – śabda-anukṛti.

Abhinavagupta, in his typical style, provides a totally different sort of explanation to the term Tandava. According to him, the term Tāṇḍava is derived from the sounds like ‘Tando; tam-tam’, produced by the accompanying Damaru shaped drums. It follows the manner, in Grammar (vyākaraṇa), of naming an object, based on the sound it produces – śabda-anukṛti.

For instance; Yaska, in his Nirukta (3. 18) had mentioned that a kaka- काक- (crow) is so called, because of the sound it makes – kāka, iti Śabda, anukṛtis, tad idam, śakunisu bahulam; and the battle-drum which makes loud Dun-Dun sounds is named Dundubhi (दुन्दुभि)

–dundubhir.iti.śabda.anukaraṇam (Nir.9.12)

And, Panini following the principle of avyaktā-anukaraṇa-syāta itau pata (PS. 6.1.98) derives certain words like Phata-phata, Khata-khata and Mara-mara etc., by imitation of indistinct sounds they are associated with.

Abhinavagupta also mentions that the Bhaṇḍam (percussion instruments), which produce sounds like ‘Bhan, Than’ etc., are important for the performance of the Nṛtta.]

And, in regard to the Drama, the Tandava, a form of Nrtta, is performed before the commencement of the play, as a prayer-offering to gods (Deva stuti). It is a dance that creates beauty of form; and, is submitted to gods, just as one offers flowers (pushpanjali).

The Fourth Chapter of the Natyashastra is termed as “The Definition of the Vigorous Dance” (Tāṇḍava-lakṣaṇam)

The Tandava, at this stage, did not necessarily mean a violent dance; nor was it performed only by men.

According to Bharata, the Tandava Nrtta, during Purvaranga, is performed to accompaniment of appropriate songs and drums. And, it is composed of Recakas, Angaharas and the Pindibandhas; (NS. 4. 259-61).

Recakā Aṅgahārāśca Piṇḍībandhā tasthaiva ca॥ 4.259॥ sṛṣṭvā bhagavatā dattās Taṇḍave munaye tadā। tenāpi hi tataḥ samyag-gāna-bhāṇḍa-samanvitaḥ ॥ 4.260॥ Nṛtta-prayogaḥ sṛṣṭo yaḥ sa Tāṇḍava iti smṛtaḥ ॥ 4.261॥

[Please also check this link

http://www.tarrdaniel.com/documents/Yoga-Yogacara/nata_yoga.html ]

**

Sukumara

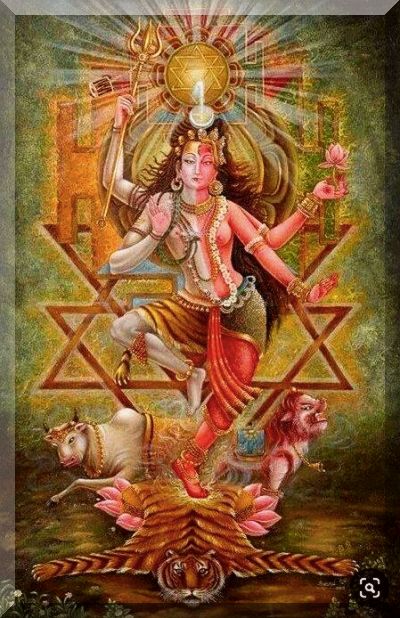

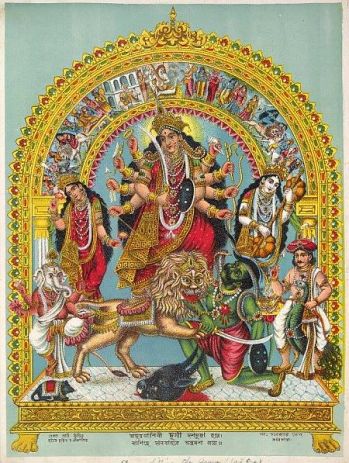

And , Sukumara Prayoga is the tender and graceful type of dance performed by the Devi Parvathi.

It is said; Shiva’s Tandava dance comprising Angaharas and Recakas inspired Devi Parvathi to perform her own type of dance, adorned with graceful and delicate movements (sukumara-prayoga) – (Sukumāra-prayogeṇa Nṛttam caiva Pārvatīm –NS.4.250).

Recakair-aṅgahāraiś ca Nṛtyantaṃ vīkṣya Saṅkaram ॥ 249॥ Sukumāra-prayogeṇa Nṛtyantīṃ caiva Pārvatīm । (NS. 4. 249-50)

Parvathi ‘s dance was also adorned with graceful gestures – Recakas and Angaharas. But, her dance cannot be construed as s counterpart to Tandava. It was her own form of Dance.

*

Abhinavagupta explains; the Angaharas of Parvathi’s Dance was rich in loveliness and subtle beauty (Lalitha Angahara); celebrating the erotic sentiment, Sṛṅgāra, the love that binds male and female – (Sukumāra-prayogaśca śṛṅgāra-rasa-sambhavaḥ – NS.4.269). Her Dance was bedecked with emotion; and, was full of meaning (Abhinaya prāptyartham arthānāṃ tajjñair abhinayaḥ kṛtaḥ – NS.4. 261).

Yattu śṛṅgāra saṃbaddhaṃ gānaṃ strī puruṣā aśrayam । Devī kṛtair aṅgahārair lalitais tat prayojayet ॥ NS.4. 312॥

Abhinavagupta says; the fruit (phala) of the gentle dance is that it pleases the Goddess (Devī); and that of Tāṇḍava is that it pleases Shiva who is with Soma. He also mentions that while performing the dance-gestures (abhinaya) for Puṣhpāñjali, the dancer’s looks must not be diverted towards the audience. That is because; that dance-offering is not addressed to the spectators. Therefore, it must be performed looking into one’s own soul.

[ We need to remember that the Tandava and the Sukumara, the pure types of Dances, were discussed by Bharata in the context of the purvaranga, not in that of drama proper (yaścāyaṃ pūrva-raṅgastu tvayā śuddhaḥ prayojitaḥ – NS.4. 15). And, such a Purvaranga was called Chitra (Citro nāma bhaviṣyati); Chitra meant diagrams/formations. These dances , at that stage , were not associated with expression of emotions.

However, Abhinavagupta, in his commentary, at many places, interprets Natyashastra in the light of contemporary concepts and practices. He also introduces certain ideas and terms that were not present during the time of Bharata.

For instance; during the time of Bharata, there was no clear theoretical division of Dance into Tandava and Sukumara. And, the term Lasya, which in the later period meant gentle, delicate and graceful, does not also appear in Natyashastra. But, the concept of the element of grace and beauty did exist; and, was named as Sukumara-prayoga.

The Tandava as described in the Natyashastra was Nrtta (pure dance); and, it was not necessarily aggressive; though Abhinavagupta interpreted Tandava as Uddhata (vigorous). But, in the Natyashastra, Tandava does not convey the sense of Uddhata.

Similarly, though Tandava is mentioned as Nrtta; it, in no way, refers to, or is related to furious dance, which in the present-day goes by the name Tandava-nrtta

Abhinavagupta states that Lasya (which term he uses to substitute Sukumara-prayoga), the graceful dance with delicate, graceful movements , performed by Devi Parvathi was in contrast to Shiva’s forceful (Uddhata Angaharas) and fast paced Tandava Nrtta. But, nether term Lasya, nor such distinctions or contrasts are mentioned in the Natyashastra.

Both Tandava and Sukumara come under Nrtta – the pure Dance, devoid of meaning and emotion. But, Abhinavagupta describes the Sukumara of Devi as being ‘bedecked with emotion and full of meaning’.

Abhinavagupta also brings in the notion of relating Tandava and Sukumara to male (Purusha) and female (Stri) dances. But, such gender-based associations were not mentioned in the Natyashastra.]

Recaka, Karana and Angahara

As mentioned earlier, according to Bharata, the Tandava Nrtta, performed to the accompaniment of appropriate songs and drum-beats, is composed of Recakas, Angaharas and the Pindibandhas – (Recakā Aṅgahārāśca Piṇḍībandhā tasthaiva ca – NS. 4. 259-61). The Tandava, at this stage, as said earlier, did not necessarily mean a violent dance; nor was it performed only by men.

Recaka

Here, Recaka (derived from Recita, relating to limbs) is understood as the extending movements of the feet (pāda), waist (kaṭi), hands (hasta) and neck (grīva or kanta): pāda-recaka ekaḥ syat dvitīya kaṭi-recaka kararecakas tritīyas tu caturtaḥ kaṇṭha-recakaḥ (NS.4. 248). The Recakas are said to be separate movements; and, are not parts of Karanas or Cari.

Movement of the feet from one side to the other with faltering or unsteady gaits as also of other types of feet movement is called Pada-recaka. Rising up, stretching up and turning round the waist as well as drawing it back characterize the Kati-recaka. Throwing up,putting forward, throwing sideways, swinging round and drawing back of the hands are called Hasta-recaka. Raising up, lowering, and bending the neck sideways to left and right or such other movements form the Kanta-recaka.

In each of the four varieties of major joint movements, the limb is moved or turned from one position to another. These four basic oscillating movements, which lend grace and elegance to the postures, are regarded as fundamental to dancing.

Abhinavagupta also says; it is through the Recakas that the Karanas and the Angaharas derive their beauty and grace. He gives some guidelines to be observed while performing a Recaka of the foot (Pada-recaka) , neck (Griva-recaka) and the hands (Hastha-recaka) .

According to him; while performing the Recaka of the foot one should pay attention to the movements of the big toe; in the Recaka of the hands one should perform Hamsa-paksha Hastha in quick circular movements; and, in the Recaka of the neck one should execute it with slow graceful movements.

Padayoreva chalanam na cha parnir bhutayor antar bahisha sannatam namanonna manavyamsitam gamanam Angustasya cha /Hasthareva chalanam Hamsapakshayo paryayena dhruta bramanam/ Grivayastu Recitatvam vidhuta brantata//

It is said; on entering the stage, with flowers in her hands (puṣpāñjali-dharā bhūtvā praviśed raṅga-maṇtapam), the female dancer should be in vaisakha sthana (posture) – (वैशाख): the two feet three Tālas and a half apart; and, the thighs without motion; besides this, the two feet to be obliquely placed pointing sideways ; and , perform all the four Recakas (those of feet, waist, hands and neck) – vaiśākha-sthāna-keneha sarva-recaka-cāriṇī ॥ 274॥

And, only then , she should go round the stage scattering flowers , in submission to gods. After bowing to gods, she should perform her Abhinaya .

puṣpāñjaliṃ visṛjyātha raṅgapīṭhaṃ parītya ca ॥ 275॥ praṇamya devatābhyaś ca tato abhinayam-ācaret ॥ 276॥

[As mentioned earlier, Abhinavagupta instructs that while performing the dance-gestures (abhinaya) for Puṣhpāñjali, the dancer’s looks must not be diverted towards the audience. That is because; that dance-offering is not addressed to the spectators. Therefore, it must be performed looking into one’s own soul.]

Abhinavagupta also says, the Recakas are basically related to tender graceful movements, where music is prominent (Sukumara-Samgita-Vadya pradanene cha prayoga esham)

*

Somehow, there is not much discussion about Recaka in the major texts. Kallinātha, the commentator, merely states that Recakas form part of the Aṅgahāras; and, is useful in adjusting the Taala (time units).

Karanas

According to the Natyashastra, the Nrtta is Angahara, which is made of Karanas – Nānā Karaṇa saṃyuktair Aṅgahārair vibhūṣitam (NS.4.13)

And, Karana is defined by Bharata as the perfect combination of the hands and feet – Hasta-pada samyoga Nrttasya Karanam bhavet (NS.4.30). The Karanas are classified under Nrtta.

And, the Karanas are themselves made up of Sthanas (static postures), Caris and Nrtta-hastas (movement of the feet and the hands). It involves both the aspects: movement and position.

Abhinavagupta also explains; Karana is indeed the harmonious combination (sam-militam) of Gati (movement of feet), Sthanaka (stance), Cari (foot position) and Nrtta-hastha (hand-gestures)

Gatau tu Caryah / purvakaye tu Gatau Nrttahastha drusta-yashcha / sthithau pathakadyaha tena Gati-Sthithi – sam-militam Karanam

According to him, the Sthanaka, Cari and Nrtta-hastha can be compared to subject (kartru-pada), object (Karma-pada) and verb (Kriya-pada) in a meaningful sentence.

*

Thus, Karaṇa is not a mere pose, a stance or a posture that is isolated and frozen in time. Karaṇa is the stylized synthesis of Sthiti (a fixed position-static) and Gati (motion-dynamic). That is to say; a Karana made of Sthanas, Caris and Nrtttahastas is a dynamic process. It is an aesthetically appealing, well coordinated movement of the hands and feet, capturing an image of beauty and grace .

A Karana functions as a fundamental unit of dance. It is a technical component, which helps to provide a structural framework, on which dance movements and formations are built and developed,

Bharata enumerates 108 types of Karanas in the Fourth Chapter of the Natyashastra. He devotes a two-line verse (Karika) to each of the Karanas, mentioning the associated hand gestures (hastas), foot movements (Caris), and body positions (Mandalas).

Abhinavagupta explains Karaṇa as action (Kriyā Karaṇam); and, as the very life (jivitam) of Nṛtta. It is a Kriya, an act which starts from a given place and terminates after reaching the proper one. It involves both the static and dynamic aspects: pose (Sthiti) and movement (Gati). And that is why, he says, Karaṇa is called as ‘Nṛtta Karaṇa’.

In the Karanas, the balance, equipoise, the ease, is the key. The movement of each limb must be in relation with that of the other, which is either following it in the same direction or is playing as the counterpart in the other direction. The flow must be fluid and harmonious. Every Karana is well thought out; and, is complete by itself.

Nrtta is the art that solely depends on the form. Its purpose is to achieve beauty in forms. That is the reason; Karana is defined as the perfect composition of the entire body. Unless each and every Karana is individually illustrated, it might not be possible to point out whether it is perfect; and whether all the elements that are required for that Karana are present.

Abhinavagupta explains; Karana is different from the actions of normal life (Lokadharmi). And, it is not a mere placement, replacement or displacement. Such throws (kṣepa) of the limbs must be guided by a sense of beauty and grace (vilasa-ksepasya). Hence, Karana is a free movement of limbs in a pleasing, unbroken flow (ekā kriyā). That is why, though the Karaṇa is defined ‘kriyā karaṇam’, Abhinavagupta says: a Karana has to be intellectually and spiritually satisfying. The word nṛttasya in Bharata’s definition is meant to emphasize this aspect of dance.

Pūrva-kṣetre saṁyoga-tyāgena samucita kṣetrāntara-prapti-paryantatayā ekā kriyā tattaranmityamartha

*

As said earlier; Karaṇa was defined by Bharata as ‘hasta-pāda-saṁyogaḥ nṛttasya karaṇaṁ bhavet’ (BhN_4.30); meaning that the combination of hand and foot movements in dance (Nṛtta) are called Karaṇa.

Abhinavagupta explains that ‘hasta’ and ‘pāda’, here, do not denote merely the hand and foot. But, hasta implies all actions pertaining to the upper part (Purva-kaya) of the body (Anga); and, it’s Shākhā-aṅga (branches, the various movements of the hands – Kara varhana), and Upāṅga (subsidiaries like the eyebrows, the nose, the lower lip, the cheeks and the chin etc).

Similarly, pāda stands for all actions of the lower limbs of the body (Apara-kaya); such as sides, waist, thighs, trunk and feet.

Thus, Karana involves the movement of the feet (pada karmani); shifting of a single foot (Cari) and postures of the legs (Sthana), along with hand gestures (hastas– single as also combined Nrtta gestures).

And, all the actions of the hands and feet must be suitably and coherently combined with those of the waist, sides, thighs, chest and back – Hasta, pada samyogaha Nrtta Karanam bhavet.

That is to say; when the Anga moves, the Pratyanga and Upanga also move accordingly. The flow of the movement (gatravikshepa) should be such that the entire body is involved in the curves and bends.

hastau śiras-sannataṃ ca gaṅgāvataraṇaṃ tviti / yāni sthānāni yāścāryo vyāyāme kathitāni tu // BhN_4.169 // ādapracārastveṣāṃ tu karaṇānāmayaṃ bhavet / ye cāpi nṛtta hastāstu gaditā nṛttakarmaṇi // BhN_4.170 //

*

There is an elaborate discussion on two important features of a Karana execution:

(1) Sausthava (keeping different limbs in their proper position) – about which Bharata says that the whole beauty of Nrtta rests on the Sausthava , so the performer never shines unless he pays attention to this – Shobha sarvaiva nityam hi Sausthavam; and,

(2) Chaturasrya (square composition of the body, mainly in relation to the chest) – about which Abhinavagupta remarks that the very vital principle (jivitam) of the body, in dance, is based on its square position (Chaturasrya-mulam Nrttena angasya jivitam), and adds that the very object of Sausthava is to attain a perfect Chaturasrya ,

This again emphasizes that Nrtta rests on the notion of formal-beauty, which is achieved through the perfect composition of the whole body. This involves not merely the geometrical values, but also the balance and harmony among the body parts.

While commenting on the Karaṇas, Abhinavagupta says that such static elements within the dynamics of the Karaṇas are useful in dance, not only as factors that beautify the presentation , but also as mediums of expression for communicating the meaning of the lyrics through vākyā-arthā-abhinaya (actions interpreting the meanings of its sentences). According to him, the Karanas are not mere physical actions; they can give form to ideas and thoughts. He opines that Nrtta can produce Bhavas. And, Nrtta, in reality, is Art par excellence.

While commenting on the fifteenth Karaṇa (the Svastika), Abhinavagupta asserts that every Karaṇa is capable of conveying a certain idea (Artha) or a thought, at least in a very subtle way. (But, such notions of associating Karanas with representation are not found in the Natyashastra.)

Sarangadeva in his Sangitaratnakara (Chapter 7, Nrttakarana, verses 548-49) also defines the Nrtta Karana as a beautiful (vilasena) combination of the actions (kriya) of the hands (Kara), feet (pada) etc., appropriate to the Rasa it intends to evoke.

Thus, while many of the 108-karanas are primarily associated with stylized movements, some Nṛtta Karaṇas are used, also, to express various emotions; going beyond the conventional Nrtta format. And, the depiction of such Karanas is a dynamic process. There is scope for innovation and experimentation.

For instance; while explaining the 10th Karana – the Ardha-nikuttaka karana (placing one hand on the shoulder; striking it with outstretched fingers; and then striking the ground with one of the heels) – which employs ancita (curve) of the hands, Abhinavagupta mentions that Sankuka’s description was different from that of Bharata; and, cannot be accepted. Further, he says; this Karana can be performed in two or more different ways; and, therefore, concludes that the performer has some degree of freedom in interpreting a Karana.

He mentions that a Karana can be performed both in the sitting posture and by moving about on a stage by employing Nrtta-hastas (hand postures) and Drsti (glances)

– Tatravastane karakayopayogi sthanakam. Gatau tu caryah; purvakaye to gatanau Nrtta-hasta Drstaya ca

And, again, along with his explanation of the 66th Karaṇa (Atikranta – moving forward with each foot treading alternatively with a flourish and swing), he states that wherever the use of the Karaṇa is not specifically stated, it is left to the imagination of the performer.

[In the later times, Karanas came to be described as the means to convey a meaning (Artha) or a pattern, such as: svastikarcita or mandala-svastika. But, in the Natyashastra, the Nrtta or the Karanas are not associated with such representations.]

And, in the later times, the idioms and phrases (Karanas and Angahara) of these dances, as also the ways of expressing the intent and meaning (Abhinaya) of a situation or of a lyric, were adopted into the play-proper, as also into various Dance forms; thus , enhancing the quality of those art-forms.

It is said; even during the course of the play , one should adopt the physical movements – Uddhata Angaharas of Tandava, created by Shiva, while depicting action in fighting scenes. And, for rendering love-scenes, one should adopt the Sukumara Angaharas created by the Devi.

Since the Karanas epitomize the beauty of form; and, symbolize the concept of aesthetics, they served as models for the artist; and, inspired them to create sculptures of lasting beauty. The sculptors (Shilpis) regarded the Karanas as the vital breath (Prana) of their Art. The much admired Indian sculptures are, indeed, the frozen forms of Karanas. The linear measurements or the deviation from the vertical median (Brahma Sutra); the stances; and, iconometry of the Indian sculptures are all rooted in the Karanas of the Nrtta, the idiom of visual delight. These wondrous sculptures, poems in stone, continue to fascinate and do evoke admiration and pleasure (Rasa) in the hearts of the viewers.

[Please do not fail to read the Doctoral thesis on the Dance imagery in south Indian temples : study of the 108-karana sculptures, prepared by Dr. Bindu S. Shankar]

And, in the present-day dance curriculum, the Karanas are used as the phrases or the basic units of the dance structure. Nrtta is taught as a combination of basic dance motions called Adavus for which there is a corresponding pattern of phonetic syllables. The Adavus of Bharatanatya are based in limb movements, postures, hand gestures and geometry as in the Karanas; though the Adavus might differ from Karanas, in their execution.

Adavus are regarded as the building blocks of Bharatanatya. Different combinations of Adavus create varieties of body movements.

[The Adavus (smallest units of dance patterns) are composed as dance-modulations (Nrtta), where all the movements relate to the vertical median (Brahma-sutra) on the one hand; and to the stable equipoise, fixed position of one-half of the dancer’s body, on the other. The Adavus are, thus, primary units of movements, where the position of the feet (Sthana), posture of our standing (Mandala), walking movements (Cari), gestures of the hands (Nrtta hasthas) and other limbs of the body together form a precise dance pattern. It is said; there are about ten or more basic types of Adavus (Dasha-vidha); and, more number of variations could be formed de pending on the School of Dancing (Bani).]

Aṅgahāra

Nrtta in Natyashastra is of Angaharas, which are made of Karanas – Nānā Karaṇa saṃyuktair Aṅgahārair vibhūṣitam (NS.4.13)

Abhinavagupta explains Aṅgahāra as the process of ‘sending the limbs of the body from a given position to the other proper one (Angavikshepa). It could also be taken to mean, twisting and bending of the limbs in a graceful manner.

And, such Angavikshepa is said to be a dominant feature of the Nrtta. And, as mentioned earlier, that term stands for graceful composition of limbs (gatram vilasena kshepaha). Thus, the Angaharas, basically, are Nrtta movements, the Angika-abhinaya, involving six Angas or segments of the body.

*

Dr . Padma Subrahmanyam explains :

Āṅgika-abhinaya or physical expression is threefold, namely Shākhā, Aṅkura and Nṛtta.

Shākhā literally means branch. It is the term used for the various movements of the hands (kara-varhana). All the gestures and movements of the hands are Shākhā.

Aṅkura, which literally means a sprout, is the movement of the hand that supplements an idea just represented.

The third element of Aṅgika-abhinaya is Nṛtta, which is made up of Karaṇas and Aṅgahāras. The Nṛtta employs all the Aṅgas and Upāṅgas.

Aṅgas are the major limbs of the body which include the head, chest, sides, waist, hands and feet. Upāṅgas are the minor limbs, which include the neck, elbows, knees, toes and heels. The Upāṅgas of the face include eyes, eyebrows, nose, lower lip and chin.

Therefore, according to Abhinavagupta, the terms Hasta and Pāda imply practically all the Aṅgas and Upāṅgas of the body.

Therefore, the performance of the Karaṇa demands a mastery over all the exercises prescribed for the major and minor limbs. Bharata says that all the exercises of the feet prescribed for the Shānas and Cārīs apply to the karaṇas. He also states that the use of the actions of the hands and feet must be suitably and coherently combined with those of the waist, sides, thighs, chest and back. It thus, signifies that the flow of the movement should be such that the entire body is involved in the curves and bends. It is not the isolated action of the specified limb alone. All actions are harmoniously interrelated.

*

Abhinavagupta relates Angavikshepa to the Angaharas; and says, they could be taken, almost, as synonyms . But, they are not the same.

The Angaharas along with Recakas and Karanas constitute the essential aspects of the Nrtta; especially in the in the Purvaranga, and at times on the stage, as a part of the prelude (Naandi), by female dancers dressed as goddesses – niṣkrāntāsu ca sarvāsu nartakīsu tataḥ param – 5. 156. Bharata lists 32 Angaharas in verses 19 to 26 of Chapter Four.

Abhinavagupta observes that the Angaharas could perhaps be as many as 108 or more. But, of these, only 64 are important in providing rhythm and graceful movements (Gati). But, he lists only 32 Angaharas.

[Towards the end of his comments on the 32 Angaharas, Abhinavagupta mentions that these could be produced in separate two sets of 16 each. One set of sixteen could be performed as a part of the Purvanga; and, the other set of sixteen after lifting the curtain, in full view of the spectators. While on the stage, four female dancers could perform four Angaharas each. Eight of them could be in Trisra Taala and the other eight in Chatursra Taala (Trysratalakah sodasa Esam; caturasra sryastav avantaratah).]

A Karana, as said earlier, is a basic unit of dance, constructed of well coordinated static postures and dynamic movements. The Nrtta technique consists in constructing a series of short compositions, by using the Karanas.

The Natyashastra mentions that a unit of two Karanas makes one Matrka; three Karanas makes one Kalapaka; four Karanas make a Sandaka; and, five Karanas make one Samghataka. Thus, it says, The Angaharas consist of six, seven, eight or nine Karanas. The Matrkas and Angaharas are used in the Pindibandhas (Group-dances).

A meaningful combination of six to nine Karanas is said to constitute an Angahara, which could be called as a basic dance sequence –

(ṣaḍbhirvā saptabhirvāpi aṣṭabhir navabhis tathā। karaṇairiha saṃyuktā aṅgahārāḥ prakīrtāḥ – NS.4.33).

It is said; the Angahara is like a garland where the selected Karanas (like flowers) are strung together, weaving a delightful pattern. It is basically a visual delight (prekshaniya).

Angahara is, thus, a dance sequence composed of uninterrupted series of Karanas. Such combination of Karanas cannot be done randomly; but, it should follow a method. That is because; the nature of an Angahāra is defined by the appropriate arrangement (yojana) or the order of the occurrence of its constituent Karaṇas. Out of the 108, say, six to nine suitable Karanas are, therefore, selected and strung together in various permutations to form a meaningful Angahara sequences or a Dance segment. Chapter Four (verses 31 to 55) of the Natyashastra describes 32 selected Angaharas, to choose from.

[Pundarika Vittala, the author of Nartana -nirnaya , mentions that by his time, the sixteenth century, the 108 Karanas had , in effect , been reduced to sixteen.]

Abhinavagupta, while explaining the fourth Angahara (the Apaviddha) remarks that even the best of the theoreticians (Lakshnakaro) cannot rationally and adequately explain the sequence of Karanas that should occur in an Angahara. Hence, whatever sequence is given by authorities should not be taken as final. The performers should go by their experience and intuition. The choreographer / performer, therefore, enjoys a certain degree of freedom in composing an Angahara sequence.

Nahi susiksitopi lakshnakaro vakyanam pratipadam laksanam keutum saknoti / Asya pascadidam prayojyamiti jnapitena kincid atmaano yojana ca samhita karya / Niyeimanamagre vak ityuktam /

Though Angaharas and Karanas have much in common, the two are not said to be the same. The Angaharas are not merely the sum or totality of Karanas. Each possesses a distinctive character of its own. The Angaharas are distinct from Karanas. That is the reason, Bharata says: Nana karaṇa saṃyuktān vyākhyāsyāmi sarecakān (NS.4.19)

The Angaharas, though mainly made up of Karanas, also need Recakas, which are the stylized movements of four limbs: neck (griva), hands (hasta), waist (kati) and feet (carana). The Recakas fulfill two purposes. One, it provides beauty and grace to the presentation; and, two, it ensures a smooth and seamless movement in such a way as to adjust the entire Angahara to the given Tala.

*

Thus, in short, the Dance choreography of Nrtta is the series of body-movements, composed of Angaharas. The Angaharas in turn, are made of appropriate Karanas. And, the Karanas are themselves made up of Caris, Nrtta-hastas and Sthanas.

Nrtta, as articulated by Bharata, is of the Marga class. And, according to Abhinavagupta, it is capable of evoking Rasa, although it is non-representational.

Which is the basic unit of Nrtta..?

Now, we have in sequence Caris; Nrtta–hastas; Sthanas; Karanas and Angaharas.

And, Abhinavagupta questions, which of these should be considered as the basic unit of Nrtta. He says the combination of two karanas, called Nrtta-matrka (Nrtta alphabet) is the basic unit of Nrtta; because, until the two Karanas are performed, you will not get the sense that you are dancing (Nrttyati).

But, that view was disputed by the later scholars. They counter questioned why only two Karanas; why not three or four or more.

They point out that the components of a Karana; like Caris; Nrtta-hastas; Sthanas, by themselves, individually cannot convey the sense of the Nrtta. They argued that Karana is, indeed, the factor, that characterizes Nrtta, which is built up by the clever arrangement of its patterns, just as in architecture. That form of beauty is achieved through the perfect geometrical qualities and harmonious composition of various body-parts. The sense of balance, ease and poise is the key. Therefore, a well thought out Karana, which is complete by itself, is regarded as the basic unit of Nrtta.

Bharatanatya

Eventually, the Karanas, Angaharas and Nrtta, all, form part of Nrtya, the expressive dance. And, a Dance form like Bharatanatya is not complete without adaptation of the Nrtta techniques.

Bharatanatya is a composite Dance form, which brings together Nrtta, Nrtya and Natya formats. It draws its references (apart from Natyashastra) from various other texts of regional nature. Besides, it has developed its own specialized forms.

The Indian classical dance of today (Bharatanatya) has, over a period, evolved its own Grammar; and, has constructed its own devices. Its Nrtta element too has changed greatly from what it meant during the days of Bharata. Its structure and style is based in different units of movements, postures, and hand gestures such as Adavus etc., which are the combination of steps and gestures artistically woven into Nrtta sequences.

The basic Nrtta items in the Bharatanatya repertoire are the Alarippu (invocation); Jatiswaram (perhaps a successor of Yati Nrtta, where the Jati patterns are interspersed with appropriate Svara); and , Tillana (brisk, short rhythmic passages presented towards the close of the performance

Such Nrtta items in a Bharatanatya performance are dominated by the technique of the Angikabhinaya, which is defined as acting by means of body movements.

[ Alarippu

Alarippu is a dance invocation, which , at the same time, executes a series of pure Dance movements (Nrtta) following rhythmic patterns. It is an ideal introduction or prologue to a Dance performance. It commences with perfect repose, a well balanced poise (Sama-bhanga). Then, the individual movements of the neck, the shoulders, and the arms follow. And, next is the Ardha-mandali (the flexed position of the knees) and the full Mandali. Thus, the Alarippu introduces the movements of the major limbs (Anga) and the minor limbs (Upanga) , in their simple formations. The dancer, thus, is able to check on her limb-movements; attaining positions of perfect balance; and, the ease of her performance. The Alarippu sets the Dancer and the Dance performance to take off with eloquence and composure.

Jatisvaram

The Jatisvaram, which follows the Alarippu, is also a dance form of the Nrtta class. It properly introduces the music element into the dance. The Jatisvaram follows the rules of the Svara-jati , in its musical structure. And, it consists three movements: the Pallavi, the Anu-pallavi and the Charanam. The music of the Jatisvaram is distinguished from the musical composition called Gita (song) ; as also from the Varnam , which is a complex composition. In the Jatisvaram, the music is not composed of meaningful words. But, here, the series of sol-fa passages (Svaras) are very highly important. A Jatisvaram composition is set to five Jatis (time-units) of metrical – cyclic patterns (Taala) – say, of 3,4,5,7,9. The basic Taala cycle guides the dancer; and she weaves different types of rhythmic patterns, in terms of the primary units of the dance (the Adavus).

The execution of Jatisvaram is based on the principle of repetition of the musical notes (Svara) of the melody, set to a given Taala. Following that principle, the dancer weaves a variety of dance-patterns.

Thus, what is pure Svara in music becomes pure dance (Nrtta) modulation in the Jatisvaram. The dancer and the musician may begin together on the first note of the melody; and, synchronize to return to the first beat of the Taala cycle; or, the dancer may begin the dance-pattern on the third beat, and yet may synchronize at the end of the phrase of the melodic line. But, the variety of punctuations and combinations within the Jatisvaram format are truly countless. It is up to the ingenuity, the skill and imagination of the dancer to weave as many complex patterns as she is capable of.

Tillana

Tillana is a rhythmic dance that is generally performed towards the end of a concert. A Tillana uses Taala-like phrases in the Pallavi and Anupallavi, and lyrics in the Charanam. It is predominantly a rhythmic composition.

**

Varnam

The Varnam is a highly interesting and complex composition in the Karnataka Samgita. And, when adopted into Dance-form, Varnam is transformed into the richest composition in Bharatanatya. The Varnam, either in music or dance, is a finely crafted exquisite works of art; and, it gives full scope to the musician and also to the dancer to display ones knowledge, skill and expertise.

And , in Dance , its alternating passages of Sahitya (lyrics) and Svaras (notes of the melody) gives scope to the dancer to perform both the Nrtya (dance with Abhinaya) and Nrtta (pure dance movements) aspects. In its performance, a Varnam employs all the three tempos. The movement of a Varnam, which is crisp and tightly knit, is strictly controlled; and, it’s rendering demands discipline and skill. It also calls for complete understanding between the singer and the dancer; and also for the dancer’s ability to interpret not only the words (Sahitya) but also the musical notes (Svaras) as per the requisite time units (Taala). The dancer presents, in varied ways, through Angika-abhinaya the dance elements, which the singer brings forth through the rendering of the Svaras.

A typical concert repertoire follows:

-

- Allāripu: devotion to Lord Nataraja, God of dance

- Ranga puja: (worship of the stage)

- Pushpānjali: (offering of flowers)

- Jatisvaram: : rhythmic pattern exploration

- Shabdam: literal miming of lyrical musical content

- Varnam: evoking abhinaya; Sthāyibhava (dominant state) ; Sanchāribhava (transitory state)

- Padam: interpretation of lyrical passage set to music- content usually that of a woman in a state of expectancy or separation/union with a lover- allegorical content of union with divinity/ lover

- Tillāna: introduction of technical floor choreography – movement along lines, triangles, diagonals, circles

- Slokā: invocation of God in a peaceful mood ; and

- Mangala: concluding with prayer for the wellbeing and happiness of all in the three worlds ]

The Abhinaya Darpana of Nandikeshvara is widely used by the teachers and learners of Bharatanatya. The text is concerned mainly with the descriptions and applications of Angikabhinaya in dance. These are body movements composed by combining the movements of body parts; such as: Angas (major limbs); Upangas (minor limbs), and Pratayangas (smaller parts like fingers, etc).

[The Abhinaya Darpana (Chapter 8, Angika Abhinaya Pages: 47 to71) lists, in great detail, the following kinds of body movements under Angika-abhinaya. And, these are followed by the students and the teachers of Bharatanatya.

- Shirobheda (movements of the head);

- Dristibheda (movements of the eyes);

- Grivabheda (movements of the neck);

- Asamyukta-hasta (gestures of one hand);

- Samyukta-hasta (gestures by both hands together);

- Padabheda (standing postures with Hasta);

- Sthanaka (Simple standing posture);

- Utplavana (jumps);

- Chari-s (different ways of walking, or moving of feet/soles); and,

- Gati-s (different ways of walking)

In addition, there are other kinds of movements and activities of various parts of the body that are important to Nrtta.]

[The following well known verses said to be of the Abhinaya Darpana are very often quoted

Khantaanyat Lambayat Geetam; Hastena Artha Pradakshayat; Chakshubhyam Darshayat Bhavom; Padabhyam Tala Acherait

Keep your throat full of song; Let your hands bring out the meaning; May your glance be full of expression, While your feet maintain the rhythm

Yato Hasta tato Drushti; Yato Drushti tato Manaha; Yato Manaha tato Bhavaha; Yato Bhava tato Rasaha

Where the hand goes, there the eyes should follow; Where the eyes are, there the mind should follow; Where the mind is, there the expression should be brought out; Where there is expression , there the Rasa will manifest.]

Pindlbandhas

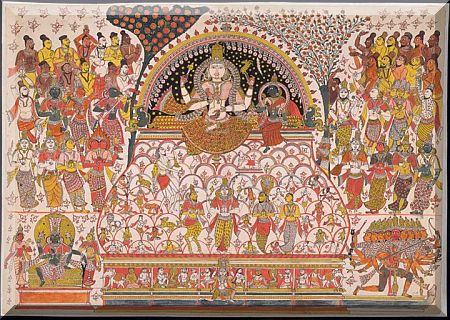

Pindlbandhas (Pindi = cluster or lump) are basically group dances that constitute a distinct phase of the preliminaries (purvaranga) to a play. According to Bharata, the Pindlbandhas were patterned after the dance performed by Shiva along with his Ganas and disciples such as Nandi and Bhadramukha. The purpose of performing the Pindlbandhas, before the commencement of the play proper, was to please the gods; and, to invoke their blessings.

After the exit of the dancer who performed the Pushpanjali (flower offering to gods), The Pindis are danced , by another set of women, to the accompaniment of songs and instrumental music

– anyāścā anukrameṇātha piṇḍīṃ badhnanti yāḥ striyaḥ- ॥ 279॥

***

While describing the physical structure and composition of the Pindibandhas; and the various types of clusters and patterns formed by its dancers, Bharata mentions four types of Pindibandhas that were performed during his time: Pindi (Gulma-lump-like formation); Latha (entwined creeper or net like formation, where dancers put their arms around each other); Srinkhalika (chain like formation by holding each other’s hands); and, Bhedyaka (where the dancers break away from the group and perform individual numbers).

piṇḍī śṛṅkhalikā caiva latābandho’tha bhedyakaḥ । piṇḍībandhastu piṇḍatvādgulmaḥ śṛṅkhalikā bhavet ॥ 288॥

In short; the Pindibandha is the technique of group formations; and, weaving patterns. Abhinavagupta describes it as ‘piṇḍī ādhāra aṅgādi saṅghātaḥ,’- a collection of all those basic elements which make a composite whole. It is called Pindibandha, because it draws in all other aspects; and, ties them together. He also states that Aṅgahāras form the core of the Pindibandhas.

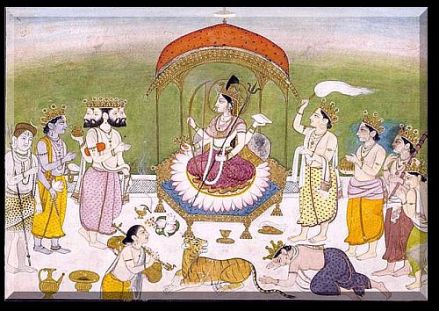

It is said; each variation of a cluster-formation (Pindi) was dedicated to and named after a god or a goddess, who was denoted by the weapons, vehicles, insignia or emblems associated with that deity; and, her/his glory was celebrated through the formation created by the dancers.

Abhinavagupta also explains Pindibandha as the term which refers to the insignia or weapon etc; and, which reminds one of the divinity or concept associated with it.

Pindi adhara-angadi sanghatah; taya badhyate buddhau pravesyate tanu-bhavena sakalaya va vyoma-adaviti pindibandha akrti-visesah

(For instance: Īśvara piṇḍī for Īśvara; Siṁhavāhinī for Caṇḍikā; Śikhī piṇḍī for Kumar and so on).

Īśvara piṇḍī for Īśvara Pattasi, i.e. Suelam piṇḍī for Nandi Siṁhavāhinī for Caṇḍikā Tarkṣya (Garuḍa) for Viṣṇu Padma piṇḍī for Brahmā Airāvati for Indra Jaṣa (Fish) piṇḍī for Manmatha Śikhī piṇḍī (Peacock) for Kumāra) Padma for Śrī (Lakṣmī) Dhara (drops of water) for Jāhnavyā (Gaṅgā) Pāśa piṇḍī for Yama Nadī (River) for Varuṇa Yakṣī for Kubera Hala (Plough) for Balarāma Sarpa for Bhogīs (Nāgas) Mahāpiṇḍi for Gaṇeśvarī, for breaking Dakṣa’s sacrifice Triśūlakṛti for Rudra who annihilated Andhakāsura.

chakruste naama pind’eenaam bandhamaasaam salakshanam/ eeshvarasyeshvaree pind’ee nandinashchaapi pat’t’asee/253..

chand’ikaayaa bhavetpind’ee tathaa vai simhavaahinee / taarkshyapind’ee bhavedvishnoh’ padmapind’ee svayambhuvah/254..

shakrasyairaavatee pind’ee jhashapind’ee tu maanmathee /shikhipind’ee kumaarasya roopapind’ee bhavechchhriyah’ /255..

dhaaraapind’ee cha jaahnavyaah’ paashapind’ee yamasya cha /vaarunee cha nadeepind’ee yaakshee syaaddhanadasya tu 256..

halapind’ee balasyaapi sarpapind’ee tu bhoginaam / gaaneshvaree mahaapind’ee dakshayajnyavimardinee/257

trishoolaakri’tisamsthaanaa raudree syaadandhakadvishah’/evamanyaasvapi tathaa devataasu yathaakramam /258

dhvajabhootaah’ prayoktavyaah’ pind’eebandhaah’suchihnitaah/rechakaa angahaaraashcha pind’eebandhaatasthaiva cha259

Abhinavagupta explains that in the Pindibandha, the dancers coming together, can combine in two ways : as Sajatiya , in which the two dancers would appear as two lotuses from a common stalk; or as Vijatiya, in which one dancer will remain in one pose like the swan and the other will be in a different pose to give the effect of lotus with stalk, held by the swan-lady. And, in the gulma-srnkhalika formation, three women would combine; and in the Latha, creeper like formation, four women would combine.

Bharata provides a list of such Pindis in verses 253-258 of Chapter Four. Bharata states that in order to be able to create such auspicious diagrams/formations (citra), in an appropriate manner, the dancers need to undergo systematic training (śikṣāyogas tathā caiva prayoktavyaḥ prayoktṛbhiḥ – NS.4.291)

The presentation of the preliminaries seemed to be quite an elaborate affair, with the participation of singers, drummers, and groups of dancers.

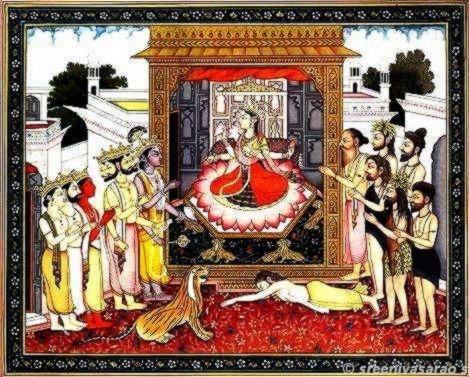

The most celebrated type of the Pindibandha Nrtta is, of course, is the Rasalila that Sri Krishna performed with the Goips amidst the mango and Kadamba groves along the banks of the gentle flowing Yamuna under resplendent full moon of the Sharad-ritu.

Srimamad Bhagavatha sings the glory and joy of Rasa-Lila with love and divine ecstasy, in five Chapters from 29 to 33 of the Tenth Canto (Dashama-skanda) titled as ‘Rasa-panca-adhyayi’. (Harivamsa also describes this dance; but, calls it as Hallisaka)

“That night beautified by the autumnal moon (sharad indu), the almighty Lord having seen the night rendered delightful with the blooming of autumnal jasmines sported with the Gopis, while he played on his flute melodious tunes and songs captivating the hearts of the Gopis.

Then having stationed himself between every two of these damsels the Lord of all Yoga, commenced in that circle of the Gopis the festive dance known as Rasa-Lila. Then that ring of dancers was filled with the sounds of bracelets, bangles and the kinkinis of the damsels. While they sang sweet and melodious songs filled with love, the Gopis gesticulated with their hands to express various Bhavas of the Srngara-rasa.

With their measured steps, with the movements of their hands, with their smiles, with the graceful and amorous contraction of their eyebrows, with their dancing bodies, their moving locks of hair covering their foreheads with drops of perspiration trickling down tneir gentle cheeks and with the knots of their hair loosened, Gopis began to sing. The music of their song filled the Universe.”

The Raasa Dance of today is the re-enactment of Krishna’s celestial Rasa-Lila. It is a Pindibandha type of dance performed by a well coordinated group of eight, sixteen or thirty two men and women , alternatively positioned, holding each other’s hands; forming a circle (Mandala); going round in rhythmic steps , singing songs of love made of soft and sweet sounding words; clapping each other’s hands rhythmically; and, throwing gentle looks at each other (bhrubhanga vikasita). Laya and Taala in combination with vocal and instrumental music play an important role in the Rasa dance.

*

The direct descendants of the Rasa-Lila Pindibandhas described in the Puranas are the many types of folk and other types of group in many parts of India : Raslīlā, Daṇḍaras, Kummi, Perani, Kolāṭṭam and similar other dances.

The most famous of them all is the Maha-Rasa of Manipur, performed with the singing of the verses of Srimad Bhagavata.

****

[When you take an overview, you can see that during the time of Bharata, Nrtta meant a Marga class of dance. And, Tandava and Sukumara were also of the Nrtta type. Though the connotation of those terms has since changed vastly, their underlying principles are relevant even to this day.

In the textual tradition, the framework devised by Bharata continued to be followed by the later authors, in principle, for classification and descriptions of several of dance forms – (even though Nrtta and Nrtya were no longer confined to Drama –Natya). The norms laid down by Bharata were treated as the standard or the criterion (Marga, Nibaddha), in comparison with regional (Desi) other types of improvised (Anibaddha) dance forms, in their discussions. The regional dance-forms , despite their specialized formats, were primarily based in the basic principles of Natyashastra.

This amazing continuity in the tradition of the Natyashastra is preserved in all the Indian classical Dance forms.]

In the next Part we will talk about Nrtta, Natya and Nritya as they were understood, interpreted and commented upon in the Post-Bharata period, i.e., the medieval times and in the present-day .

References and sources

- 1.Natya Nrtta and Nrtya – their meaning and relations by Prof.KM Varma

- 2.http://www.svabhinava.org/abhinava/PadmaSubrahmanyam/PadmaSub.pdf

- 3.https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file%3Faccession%3Dosu1079459926%26disposition%3Dinline

- 4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3250274?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- 5. http://www.shreelina.com/odissi/alankara/The-Mirror-of-Gestures.pdf

- 6.http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/71949/8/08_chapter%203.pdf

- 7.The Evolution of Classical Indian Dance Literature: A Study of the Sanskritic Tradition by Dr. Mandakranta Bose

- 8.http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/164285

- 9 http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/164285/8/07_chapter%202.pdf

All images are from the Internet

(Devi as Ardha-purusha)

(Devi as Ardha-purusha)