Continued from Part Two

Uddalaka Aruni – Teachings

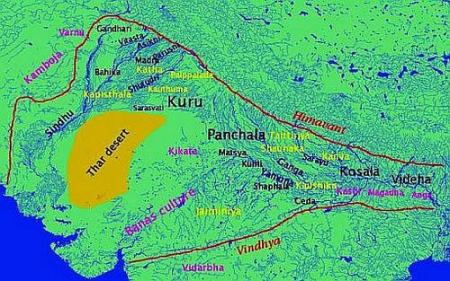

22. 1. It is said; the great Yajnavalkya (Brh.Up.6.3.15) as also the sage Kausitaki (Sat Brh.11.4.12) to whose family the portions of the Kausitaki Brahmana are attributed, Proti Kausurubindi of Kausambi (Sat Brh. 12.2.213), and Sumna-yu (Sahkhayana Aranyaka -15.1) were at onetime the students of Uddalaka Aruni.

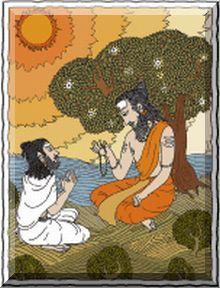

But Uddalaka’s fame as a teacher and a philosopher rests mainly on the discourses he imparted to his son Svetaketu (formally: Svetaketu Auddalaki Gautama). It contains the essential teaching of all the Upanishads.

22.2. In the Chandogya Upanishad, Uddalaka is portrayed as a caring father who sent his son, at his age of twelve, to a residential school (ante – vasin). And, on his return home, after twelve years of education, Uddalaka questions Svetaketu, now a bright looking well grown young man, to find out whether he had learned anything of importance. He questions his son whether he has learnt ‘that by which one can : hear that which is beyond hearing (Ashrutam); think that which is unthinkable (amatam); and know that which is beyond knowledge (avijnatam)’.

Tam ādeśam aprākṣyaḥ yenā-aśrutaṃ śrutaṃ bhavaty; amataṃ matam; avijñātaṃ vijñātam iti || ChUp_6,1.3 ||

Of course, he had not. Uddalaka then proceeds to teach his son, with great diligence, on what the school could not instruct: ‘knowing which everything becomes known (avijnatam vijnatam iti)’ – the real meaning of life.

Broad outline

Before entering into discussion on the teachings of Uddalaka let me outline, in broad strokes, the main aspects of his teaching.

23.1. In his exposition, in the form of a dialogue with his son Svetaketu, detailed in Part Six of the Chandogya Upanishad , spread over sixteen sections, Uddalaka covers a wide range of subjects touching upon the theories of the Absolute Being, theory of creation , the living-principle (spirit) , the nature of matter and its multiple forms, oneness of man with nature , relation between food , body and mind etc.

He bases some of his explanations on ideas that were current in his time (such as, the man being composed of sixteen parts; dependence of mind’s working on nutrition; or, the senses merging into mind and mind into Prana).

At the same time, he sets aside certain earlier notions concerning the origin of the universe (such as the universe originated from void or non-being).

In addition, he breaks away from the earlier texts and covers some fresh ground.

23.2. He questions, how anything could come out of nothing; and argues that there must have been an original being, in a very subtle but a very powerful form, giving rise to everything in the Universe. Sat the primal Being exists solely and completely by the virtue of its own power of existence. It is not abstract. It is real and alive.

23.3. He demonstrates through skillful teaching exercises – involving a pattern of activities designed to rouse the young man’s mind – that the unseen need not be understood as ‘void’; it could well be the most wonderful subtlest essence of existence which is too fine to be perceived by senses, and from which everything springs forth (as a tree growing out of the invisible core of a tiny seed), and it permeates , unseen, everything in the universe (as a lump of salt dissolved in a jug of water) as energy and vitality in all forms of life (as in a person , animal or in plants).And, finally It is into That, all existence subsides. It does not mean the universe that once was, is reduced to nothingness; for, ‘something does not become nothing, just as nothing does not become something’- Na-asti satah sambhavah; na sata atmahanam

[ After Svetaketu breaks open the seed, he reports ‘it is broken Sir’ (binna Bhagavah iti). Uddalaka asks the boy ‘what do you see in it (Kim atra pashyati iti). Svetaketu replies ‘nothing Sir’ (kinchana Bhagavah iti).

Uddalaka explains to his son that finest part in the seed which one does not see (yam na nibhalayase) is indeed the essence (animnah). In it is hidden the big banyan tree (esah mahanya-nagrodhah). Have faith, dear one (sraddhatsva somya iti).

“Just as that subtlest unseen essence pervades the tree, Similarly, Sat, subtle and invisible, pervades all existence. That subtle essence Sat is the truth, the Atman (Ch.Up.6.12.3). Everything comes from That and everything merges back into That. It is in all beings. You like the tree and the world, is made of that essence. The evidence of that can be grasped by reasoning and faith. Svetaketu, you are That (tat tvam asi śvetaketo iti).

That ‘nothingness’ need not be understood as void; that nothingness, however subtle, is never non-existent

The essence of the tree is in that seeming nothingness. The manifest emerges from the un-manifest. The cause, that nothingness, however subtle, is never non-existent. For, nothing can come out of nothing, and nothing can altogether vanish out of existence. Na-asti satah sambhavah; na sata atmahanam. This, in short, is premise of Uddalaka.

This, in essence, is the principle of Satkaryavada.

The Samkhya notions of Prakrti and the emergence of the world from the Being (Sat) and its theory of causation – Satkaryavada have their seeds in Ch Up 6.2.3&4.

Bhagavad-Gita follows this principle saying ‘there is no existence from what does not exist; there is no non-existence from what exists’ (BG; 2.16): Na-sata vidyate bhavo; na-bhavo vidyate Satah

(The later Buddhists put forward the theory of prior-non-existence (pragabhava). It asserts that something can exist now though it was not in existence before (abhutva bhavati, abhutva bhavah). This is the A-satkaryavada) ]

24.1. As regards the process of evolution, Uddalaka tries to establish, methodically, in a series of natural stages how the Reality entered into matter giving rise to multiple forms.

According to Uddalaka, all matter in the world, including human beings, is composed of three fundamental elements, each of which is a power. These are: heat-Teja (as also light or energy), water –Apah (all aspects of liquidity and fluency), and food –Anna (solids, plants and earth).

These three dominant elements, in sequence, are inspired and animated in varied degrees by the primal being (Sat or Prana). The element of fire principle has its root in Sat; that of water in fire; and that of earth in the water principle . Each one of these elements carries within it some traces of the other two elements. Therefore, there is nothing in this world that is unmixed.

24.2. All these elements are charged with the will to become many (bahau –bhavitam-iccha) and to manifest as objects; each object having a different degree of fineness; each having its own inner nature (nama) and an outward form (rupa).

25.1. Uddalaka asserts; understanding the material of which any given object is made yields an understanding of everything else made of the same material.

According to Uddalaka, every material object is composed of infinite number of extremely small particles (anu), so tightly packed they appear as a continuous whole leaving no scope for void. Each of these particles, according to him, is qualitatively different from the other; and is infinitely divisible. The minute particles (anu) ceaselessly separate and re-combine giving rise to newer forms. Each minute particle (anu) is in a churning motion within itself, by virtue of which it spontaneously unfolds or evolves; each according to its quality or nature. Each of these minute particles is charged or animated by one and the same pure and invisible energy (Sat).

25.2. Each living body or an organism is an animated whole, all parts of which being pervaded by one and the same living principle. That invisible power, the potent energy or vitality is present in the core of all beings. And, when that life-force leaves the body, the body withers and dies. But the living principle (jiva or atman) never dies.

25.3. He teaches that all objects and all living things are inter-related. The essence of everything is One, though the forms are many and the individuals are many. The whole world arises and continues to exist by virtue of that invisible essence – Sat. According to Uddalaka, in the ultimate analysis, man is nothing but an evolution of That essence. He tells his son, each time, there is nothing that does not come from that essence, “verily, you are that essence”. “O Svetaketu, do you understand what I am telling you? This great but most subtle essence of all the worlds is the Truth, the Atman, the Supreme Reality within you, and you are That (tat tvam asi)”.

26.1. Uddalaka observes that eventually, at the end, everything in existence is absorbed back into That from which everything emerged. It is the same In the case of an individual too. At his death, man reverses in successive steps towards that being from which he originated. The speech merges into mind, the mind into prana, the prana into heat and the heat, the last to depart, into the Pure Being. This process occurs in every case, as in nature, no matter whether one is aware of it or not. The process of going back is natural and does not depend on the striving of the individual. But one who is fully conscious and understands the Reality at each stage of the process gains freedom. Such knowing or not-knowing is perhaps the difference between knowledge and ignorance.

27.1. He asks his son to exercise the mind which is endowed with fabulous capacity to observe, to reason and infer, in order to gain insight into the Reality. He advises that when both his intellect and his senses do not help in leading him on the right path, he should seek guidance from a proper teacher (acharya) who knows. An ardent seeker who finds an illumined teacher attains freedom. And, in the end it is truth that protects.

27.2. But , Uddalaka cautions his son , the proof of the existence of One subtle –force (Sat) which gives birth to and sustains all life is beyond the realm of subjective sense -cognition. It is possible to understand That only through reasoning, grasped in faith. Uddalaka urges Svetaketu: ‘śraddhatsva somyeti; have faith, my dear’ (Ch. Up. 6.12.2).

27.3. Uddalaka, in his teaching, does not refer to a God or any other Supernatural Being as creator. According to him, the process of evolution, sustenance and eventual withdrawal into the source follows its own natural laws, at each stage.

Universe and its beginning

28.1. The question of the origin of the Universe and the process of evolution comes up for discussion on several occasions in the Samhitas, as also in the Upanishads. Many seers offered their explanations; and, there are, therefore, numerous theories on the subject. For instance, one theory in Rig Veda (RV 10.72) states that originally there was nothing (a-sat) and out of it being (sat) evolved. Similarly Taittiriya Upanishad (Tai.Up.2.7) mentions “Non-being, indeed, was here in the beginning (asad vaa idam agra aasiit) “. Another theory in Rig Veda (RV.10.129) speculates that in the beginning there was neither being nor non- being, but (somehow) the One , a living being, came into existence; and , it expresses a philosophical doubt as to how the universe may have evolved.

28.2. Uddalaka rejects the earlier notions of evolution of the universe. He asks how something could come out of nothing. And, he asserts that there must have been an original being from which everything in the Universe has come forth (Ch.Up.6:2:1, 2).It is not abstract; and, it is alive. He proposes and tries to establish, methodically, a series of stages of development, explaining how all reality has emanated out of the Being.

[Even at the very early stages of Indian thought, two groups had clearly emerged: the one that asserted the hypotheses of the Being, and the other of non-Being . Both left strong impressions on the later Indian speculations. In a way of speaking, the history subsequent Indian philosophy is mostly about the unfolding and expansion, a wider application, continued modifications of these two ancient postulates, or departure from either.]

28.3. Uddalaka puts forward a hypothesis: “In the beginning, my dear, this universe was Being (Sat); alone, one and only without a second (Sat tu eva, saumya, idam agra asid). Some say that in the beginning this was non-being (asat); and from that non—being, the Being was born (Kutas tu khalu, saumya, evam syat, iti hovaca, asatah saj jayeteti).” How is it possible for a Being to emerge out of Non-Being? (Katham, asatah saj jayeteti). Has anyone seen such a phenomenon? I agree, something might produce something; but, how can nothing produce something? … Listen to me my dear, In the beginning only being was here, one alone, without a second – ekam eva advaitam (Ch. Up. 6.2.2),by virtue of which everything evolved.

Kutas tu khalu, saumya, evam syat, iti hovaca, katham, asatah saj jayeteti, sat tu eva, saumya, idam agra asid ekam evadvitiyam.

[The term Sat (extended into Satyam) had several meanings depending on the context. Sri Sayanacharya has written a gloss explaining several meanings that could be ascribed to the term. For our limited purpose, Sat signifies a single (without a second) Reality existing in the beginning. A-sat is the opposite of Sat; it was non-existent at the beginning. Sat is the enduring ground; while a-sat, as opposed, is the transient variation. While sat is the substance (as in satva), a-sat relates to appearances as forms and names.

In the context of creation theories, Sat perhaps meant “this which is here and now”, and a-sat meant “that which has not yet come to be”. The Creation is understood as the transformation of the un-manifest into manifest; it is a process of becoming from Being.]

The Reality that pervades all existence

29.1. Sat, according to Uddalaka, is the origin of all things, all beings. There is nothing that does not come from Sat. It is the subtle essence that pervades all existence at all times. Of everything, Sat is its inmost Self. It is infinitely subtle and practically invisible; and one may even mistake it for non-existent.

29.2. Uddalaka demonstrates how the apparent nothingness at the innermost core of a seed holds within its womb the essence and the existence of a huge tree.” O soumya, the gentle one, in that finest part of the seed, in the core of its invisible essence resides, hidden and unperceived, the huge banyan tree (nagrodha). Is that not a wonder? Have faith in what I say” (Ch.Up.6.12.1-4). The whole varied world arises and continues to exist like a banyan tree, born and animated by virtue of That invisible essence.

Tam hovacha yam vai, saumya, etam animanam na nibhalayase, etasya vai, saumya, esho’nimna evam mahan nyagrodhas-tishthati srddhatsva, saumya iti.

“Just as that subtlest unseen essence pervades the tree, Similarly, Sat, subtle and invisible, pervades all existence. It is like a lump of salt dissolved in a jug of water, which you wouldn’t see; yet, it is there all the time. That subtle essence Sat is the truth, the Atman (Ch.Up.6.12.6). Everything comes from That and everything merges back into That. It is in all beings. You like the tree and the world, is made of that essence. The evidence of that can be grasped by reasoning and faith. Svetaketu, you are That (tat tvam asi).

Sa ya esho’nima aitad atmyam idam sarvam, tat satyam, sa atma, tat-tvam-asi, svetaketo, iti;

[This often repeated great epithet, sad-vidya or maha –vakya, at a much later time was adopted by the Vedanta School to assert oneness of Atman with Brahman.

However, Uddālaka Āruṇi does not use the term “Brahman”— either in his instruction to his son Śvetaketu, or on any other of his many appearances in the Upanishads.

As regards the question of identity of Atman with Brahman, the concept , it seems , grew in stages over long periods. Although Śāṇḍilya’s teaching of atman and Brahman is often considered the central doctrine of the Upanishads, it is important to remember that this is not the only characterization either of the self or of ultimate reality. While some teachers, such as Yājñavalkya, also equate atman with Brahman (BU 4.4.5), others, such as Uddālaka Āruṇi, do not make this identification.

Moreover, it is often unclear, even in Śāṇḍilya’s teaching, whether linking atman with Brahman refers to the complete identity of the self and ultimate reality, or if atman is considered an aspect or quality of Brahman. Such debates about how to interpret the teachings of the Upanishads have continued throughout the Indian philosophical tradition, and are particularly characteristic of the Vedanta Darshana.

Uddālaka’s famous phrase tat tvam asi was later taken by Sri Śankara to be a statement of the identity of atman and Brahman]

29.3. In order to explain his views, Uddalaka makes use of number of metaphors from the natural world. For instance, he compares Atman that exists in all beings to the nectar, despite originating from different plants, when gathered together forms a homogeneous whole. In the same way, he talks of the rivers flowing down from all directions merging into the ocean and losing their identities (Ch. Up. 6.9.1, 6.10.1–2).A wave or a bubble arising out of the vast waters of the sea loses its form and identity on merger with the sea .

Uddalaka argues, all living beings merge into existence – “whatever they are in this world a tiger, a lion, a wolf, a boar, a wolf, a worm , a gnat or a mosquito they all become That (Ch.Up.6.9.3; 6.10.2.). The process of returning to the source is a natural process and it does not depend on the striving of the individual to attain a certain ‘state’.

As bees suck nectar from many a flower / And make their honey one, so that no drop / Can say, “I am from this flower or that,” / All creatures, though one, know not they are that One.

Yatha, saumya, madhu madhukrto nistishthanti, nanatyayanam vrkshanam rasan samavaharam katam rasam gamaynti.

Te yatha tatra na vivekam labhante, amushyaham vrkshasya raso’smi, amushyaham vrkshasya rasosmiti, evam eva khalu, saumya, imah sarvah

prajah sati sampadya na viduh, sati sampadyamaha iti

As the rivers flowing east and west/Merge in the sea and become one with it / Forgetting they were ever separate streams, / So do all creatures lose their separateness/ When they merge at last into pure Being.

Imah, saumya, nadyah purastat pracyah syandante, pascat praticyah tah samudrat samudram evapiyanti, sa samudra eva bhavati, ta yatha yatra na viduh, iyam aham asmi, iyam aham asmiti.

30.1. Then he points to a tree and says it is entirely pervaded with the living self. The tree stands alive, rejoicing moisture and fresh air, drinking in and taking in all that is good: ‘If one were to strike at the bottom of this big tree, it would bleed; but it will continue to live. If one were to strike at the middle, it would bleed, but live. And, if one were to strike at the top, it would bleed, but live. Pervaded by the living self, the tree continues to live happily, drinking in its nourishment. That is to say, if life (jiva) leaves one of its branches then that branch withers, but, the tree continues to live. But in case the life were to leave the whole tree, then, the tree withers and dies’. In exactly the same manner, “That which loses life dies; but life (jiva) itself does not die (Ch. Up. 6:11:1-3)”.

1. Asya, saumya mahato vrkshasya yo mule’bhyahanyat, jivan sravet; yo

madhye’bhyahanyat, jivan sravet yo’gre ‘bhyahanyat, jivan sravet, sa esha

jivenatmana’nuprabhutah pepiyamano modamanastishthati.

3. Jivapetam vava kiledam mriyate, na jivo mriyata iti, sa ya esho’nima etad-atmyam idam sarvam, tat satyam, sa atma, tat-tvam-asi, svetaketo, iti;

Life is more than that which meets the eye. And life as life shall never die. The conditional existence (nama-rupa) of the world might vanish, but not the Sat, its underlying Reality.

30.2. Here, Uddalaka is pointing to the difference between a living organism that can survive injury, take nourishment, recover and flourish; and a dead limb, disconnected from the vitalizing principle (jiva), the source of life of the whole tree. That jiva is later identified by Uddalaka with the Atman.

30.3. Through these exercises Svetaketu learns that the Universe we live in – macro and micro – can be studied and understood. The Universe in all its aspects is infinite, complete and conserved. He learns that Self is not mere ‘me’, but is the knower.

“When a person is absorbed in dreamless sleep (swapiti) he is one with the Self, though he knows it not. We say he sleeps, but he sleeps in the Self. As a tethered bird grows tired of flying about in vain to find a place of rest and settles down at last on its own perch, so the mind, tired of wandering about hither and thither, settles down at last In the Self, dear one, to whom it is bound. All creatures, dear one, have their source in That. That is their home; That is their strength. There is nothing that does not come from That. Of everything That is the inmost Self. That is the truth; the Self supreme. You are That, Svetaketu; you are That.” (Ch.Up.6.8.1-2)

1. Uddalako harunih svetaketum putram uvaca, svapnantam me, saumya, vijanihiti, yatraitat purushah svapiti nama, sata, saumya, tada sampanno bhavati svam apito bhavati, tasmadenam

svapitity-acakshate svam he apito bhavati

2. Sa yatha sakunih sutrena prabaddho disam disam patit-vanyatrayatanam-alabdhva bandhanam evopasrayate, evam eva khalu, saumya tan mano disam disam patit-vanyatrayatanam-alabdhva pranam evopasrayate prana bandhanam hi, saumya, mana iti.

Matter

31.1. Uddalaka conceived matter as one continuous whole in which all things are mixed up. All matter, according to him, is derived from the three basic elements (dhatu: fire, water and earth principles), which, are qualitatively different from one another; and each of it has something of the other two. These elements are infinitely divisible. According to Uddalaka, there is nothing in the world that is unmixed.

31.2. Uddalaka expands on this idea in his ‘doctrine of mantha’. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (Brh.Up.3.7.1) refers to the doctrine of Mantha (a super-fine mix of ingredients) in fair detail. The term mantha denotes: to churn, to blend or to a churning –rod (say, as in the verse: Krishnam vande mantha – pasa dharm, describing the boy Krishna holding a churning – rod). The concept is derived from pounding, fine mixing and blending of various ingredients into a smooth paste (Dravadravye prakshiptâ mathitâh saktavah).

Uddalaka visualizes matter as a super-fine paste, an extremely fine mixture of infinitely small particles or atoms (anu) which are qualitatively dissimilar. The atoms incredibly minute, abundant in number are fantastically durable. The long-lived atoms really go round. They unite, separate and reunite forming incredible numbers of varieties of forms.

All matter is composed of infinite number of infinitely small seeds of things (bijani) or minds (manas), so mixed together and so tightly packed they appear as a continuous whole leaving no scope for void. These particles, according to Uddalaka, are qualitatively different from each other and are divisible. Each of those small particles is in a churning motion within itself. With the aid of the churning motion within, they spontaneously unfold or evolve, each according to its quality or nurture.

31.3. But, all matter composed of such infinite number of minute particles is animated by one and the same pure and invisible energy (Sat). Therefore, every instance of matter, beings or organisms is an animated throbbing whole, all parts of which being enlivened by one and the same living principle, in varying degrees of vitality.

31.4. Uddalaka is talking about the essential unity of the divisible and the un-divisible; of the particular and the universal; of the Being and the non-being; of the Atman and That primordial subtle essence.

Evolution

32.1. Uddalaka puts forth his hypothesis of evolution. According to him the Reality, the Sat, the pure Being desired to become many (bahusyam). First, it entered into fire or heat / light principle (tat teja aiksata); then, heat, by the same desire, produced water principle (tat apah asrajata); and water, having the same desire, in turn produced earth principle – matter or food (tat annam asrajanta).

[In the language of these texts, the term Annam has multiple meanings. Here, Annam refers not merely to food but also to the earth, the plants and all matter. Following that, anything that is external to consciousness is Annam, food. Again, that which proceeds from condensation of water is food. An object of thought is also food. Further, the terms fire, water, earth stand for all the subtle elements of that nature. ]

32.2. Resorting to the metaphor of a tree (Ch.Up.6.8, 4-6), Uddalaka explains that Sat is the root (mula), of which tejas (fire) is the sprout (srunga).Tejas in its turn is the root, of which apah (water) is the sprout. And, apah in its turn becomes the root, of which anna (food) is the sprout. Every successive effect was already present in the original cause or deity (Devatha).

[Uddalaka’s use of the term Devatha (deity) is rather ambiguous. He employs the term in metaphysical sense and also to refer to the three dominant elements. His metaphysical Devatha could be construed as pure and unmixed, one and indivisible, universal and un-manifested. His reference to the elements (tejas – fire, apah -water and anna – earth) as Devatha might be because they all are highly concentrated form of matter; charged, inspired and enlivened by the one and the same living-principle (prana).Generally, Devatha appears to denote the physical power of existence that is in motion within itself. Devatha, here, more often refers to matter than to the spirit (prana).]

The subtlest condition of fire is ether, the material basis of sound. The subtlest condition of water is air, the material basis of vital breath. The subtlest condition of earth is food, the material basis for mind or its functions.

32.3. Then, each of the three elements combined in itself something of the other two elements. Following that everything else in the universe came forth including man, mind, and matter.

Organisms

33.1. Uddalaka then moves on to creation of organisms born out of heat and moisture of earth. The birth-types are classified according to the origin and mode of development. He says; all physical bodies (animals, plants and humans) come into the world in one of three ways: by an egg (andajam), by the womb (jaraujam), or through a seed (udhbijam). Each of these Jivas becomes three-fold, due to the three elements entering in them. They all are enlivened by consciousness in varying degrees

[Tesam khalv esam bhutanam triny eva bijani bhavanti, andajam, jivajam, udbhijjam iti – Ch.Up.6.3.2.]

[Some versions mention a fourth classification: svedaja, coming out of dirt, dust, sweat, etc.]

Scheme of things

34 .1. In Uddalaka’s scheme of things, evolution follows its own natural laws. There is no role envisaged for a Creator. What is discussed here is mainly the process.

Uddalaka conceives the original being (Sat) as alive and capable of forming a wish (sankalpa). It wished to become many (bahau – bhavitam-iccha); and therefore, Sat entered into each of the three primal elements as its life, its essence and its own living self. The three subtle elements heat, water and anna (food or matter) are also conceived as living; and, are indeed referred to as divinities (Devatha) .The three elements too wished to produce multiplicity of objects having certain inward nature (nama) and outward appearance or form (rupa) , having visible shape with colours. Everything in the world is therefore alive from the beginning. Thus, the matter of the Universe is alive having desires to grow. And, it is by the power of this urge that evolution takes place.

34.2. Here, the Sat did not ‘create ‘anything. Sat entered into the elements; extended into matter.

Another important feature of Uddalaka’s hypothesis is that, the Original Being, as it enters into the elements, is not divided in the process of emanation; but it remains the Absolute.

One in many and many into one

35.1. Uddalaka builds a systematic relation between the cause (mula or root) and its effect (shoot or shrunga). He believes the effect resides in its cause; in other words, things are contained in one another. Uddalaka provides an illustration:” My dear, when the curds are churned, its minute essence rises upward to the surface and forms butter. That does not mean, the curd transformed itself to butter. It is merely that the seeds of butter concealed in the curds were extracted by the aid of churning action. And so it is with everything else” (Ch.Up.6.6.1)

[Incidentally, the Buddha, too, following the general principle ‘Being follows from Being’ put forward his concept of continual ‘coming –to-be and passing –away’ as in a series of changes each rooted in its preceding one. This process of ever changing or becoming was neither capricious nor pre-ordained but went on by way of natural causation. He too, just as Uddalaka, did not talk in terms of an agent that causes/ brings about changes, but he brought focus on the order of things itself.

When faced with questions such as ‘who desires’.’ who creates’, ‘who controls’ etc he replied the questions were wrongly framed and were not ‘sound questions’. The proper form of questions should be, he said, ‘through what conditions do desire or becoming etc occur’ (Samyutta Nikaya-2.13).In other words, there is no person or agent or soul whatever who does things. But there is only the process or the series of events which occur under certain conditions.

The Buddha also rejected the idea of the universe (loka) as an entity which had a definite beginning or an end; or as a changeless eternal substance. He, on the other hand, held universe as a process (samsara) which had no definite origin (Samyutta Nikaya-2.178). Universe, according to him, is of natural and impersonal forces and processes driven by conditions ; and is not an enduring substance. In other words, universe is a system governed by its own sets of conditions and laws.

“Leave aside the questions of the beginning and the end. I will instruct you in the Dhamma: ‘If that is, this comes to be; on springing of that, these springs up. If that is not, this does not come to be; on cession of that, this ceases’. (Majjhima-nikaya, II. 32)

The Buddha employed Uddalaka’s simile and extended it further : “ Just as from milk comes curds , from curds butter , from butter ghee , from ghee junket; but, when it is milk it is not called curds, or butter , or ghee or junket; and, when it is curds it is not called by any of the other names; and so on”.

Here, He was not only putting forward his concept of the law of causation but was also pointing to the principle of identity at each stage. Each state in the chain of changes is real in its own context and when it is ‘present’; and it is not real when it was past as ‘something that it was’; and also not real when in future ‘it will be something’.]

35.2. Having established that heat (taapa) emanated out of Sat, Uddalaka proceeds from heat to water and from there to matter. Among the later derivatives of the elements are the components of human body (flesh, blood, bone, breath etc) including mind (manas). He explains that food (or earth) is dependent on water; and, food, in turn, is the cause of man or his mind. These two-mind and matter- are indeed two aspects of the same element or power (Devatha).

“ So these three compose the world, first heat which is to say warmth in all its forms; the waters the liquidity, the fluency in all matter, and all moistures the elixirs of life in multiple forms , in our frames, plants and clouds, And food, that is solids , due sometime for one to eat but in turn be eaten by another for that is the way of all existence.

Although the substances are compounds of the elements; the elements themselves are real. They beget one another; and the Being enters them ‘with this living self’ and dwelling in them makes out their names and forms”.

35.3. Uddalaka asserts, repeatedly, everything in existence is produced by the three-fold (tri – vrit – karana) combination of these original elements (tanmatra) in varying proportions. Therefore, all the objects in the world; the nama – rupa, their name and form; are the result of the various combinations of the three elements (tanmatra). That is to say, all the variety in this world, whatever is their numbers and whatever be their forms, they all are the expressions of these three elements.

35.4. Again, each of the three elements has in itself certain properties of the other two elements. Fire, for instance, Uddalaka says, contains within itself not merely heat but something of the other two, its visibility and its colour (red). Similarly where there is water, there is food.

Generally, he says, the redness one sees in the objects is due to the fire principle in them; the whiteness that dazzles is due to the water principle; and, the darkness is due to the earth principle. These powers (the elements) are present in an object as its intrinsic or essential property; and they are not separate from that object. If the threefold presence of the elements -fire, water and earth- is withdrawn from the object, then nothing will be left of that object. Uddalaka says, therefore, whoever knows the three fundamental elements, understand the visible world. He seems to be saying that in order to understand something, it is essential to understand the elements with which it is composed.

36.1. Uddalaka explains that in order to bring forth multiplicity into existence; to develop names – and – forms in order to facilitate distinguishing one from the other; or , to set them in order, Sat entered into all elements as their living principle (jiva). That living principle is identical in almost every respect with the universal spirit (Sat or Prana). It animates in varying degrees all kinds of matter. Therefore, what is really extant in matter is the living principle.

36.2. The various distinct natures as also their names and forms (nama-rupa) are conceptions of the mind to distinguish one object from the other in this world of conditional existence. But the proof of the existence of subtle –force is beyond sense-cognition which is subjective. It is possible understand That only through reasoning, grasped in faith.

Nama –rupa

37.1. In order to introduce his doctrine of ultimate elements out of which the whole universe is constituted and of the still more ultimate being , Uddalaka points out how things superficially different may essentially be the same . “‘My child, as by knowing one lump of clay, all things made of clay are known; the difference being only in form and name arising from speech; and the truth being that all are clay. Similarly, by knowing a nugget of gold, all things made of gold are known; from one copper ornament everything made of copper are known; and, by one pair of nail scissors all that are made of iron are known; they differ only in name and form and as a matter of verbal classification, while in reality it is all iron . The different names used for different objects made from the same substance are mere conventions of speech for easy identification; but ,in fact ,the nature of all objects made of same substance is one “(Ch. Up. 6:1:4-6).

yathā somyaikena mṛtpiṇḍena sarvaṃ mṛnmayaṃ vijñātaṃ syāt | vācārambhaṇaṃ vikāro nāmadheyaṃ mṛttikety eva satyam || ChUp_6,1.4 ||

yathā somyaikena lohamaṇinā sarvaṃ lohamayaṃ vijñātaṃ syāt | vācārambhaṇaṃ vikāro nāmadheyaṃ loham ity eva satyam || ChUp_6,1.5 ||

yathā somyaikena nakhanikṛntanena sarvaṃ kārṣṇāyasaṃ vijñātaṃ syāt vācārambhaṇaṃ vikāro nāmadheyaṃ kṛṣṇāyasam ity eva satyam | evaṃ somya sa ādeśo bhavatīti || ChUp_6,1.6

37.2. Uddalaka is delineating the relation that exists between a particular material and all the objects made of that material (material causality). He is not suggesting that by knowing one material, the nature of all objects in the world made of other materials would become known. Nor is he suggesting that all objects in the world are made of the same material. Uddalaka’s claim is that, an understanding of the material of which any given object is made, yields an understanding of all other objects made of that material. Therefore, every object can be reduced to its constituents; and there is nothing in the object except its constituents.

37.3. At the same time, Uddalaka recognizes the distinctions we make amongst the different objects, made of the same substance, based on their form, structure and verbal identifications. Such object –form- distinctions are the concepts of the mind; and not intrinsic or not directly related to their cause which is uniform. He explains, the cause and effect, the root (mula) and the shoot (shrunga) might look dissimilar having different attributes (lakshana), but their essential identity is the same. This perhaps is Uddalaka’s understanding of Nama – Rupa (name and form) – conditioned existence- which becomes relevant when one becomes many; and when there are multiplicities of objects.

38.1. Uddalaka extends his argument and suggests that since all things in the world are made by the combination of the three fundamental elements (dhatus) – fire, water, and matter, the world is nothing but the nama-rupa of these elements. Therefore, we can understand the nature of the world if we understand the nature of these three elements. Uddalaka extends this line of argument further, and says: since the three fundamental elements which make the world are mere emanations of That (Sat), the entire creation is ultimately nothing but the nama – rupa of That One single Reality. Uddalaka asserts; If you take away names and forms from this existence, what remains is That (sat).

Colours

39.1. Uddalaka extends the argument from forms to colours; and says that the colours we perceive are again the expressions of the three elements: heat, water and Anna or earth. Red (rohita) is the form of heat (tejas); white (shukla) the form of waters (apah); and black (tama) the form of food (anna) or earth principle. And, that which is ‘un-understood ‘is the combination of the three divinities (Devatha). (Ch.Up.6.4.6)

yad u rohitam ivābhūd iti tejasas tad rūpam iti tad vidāṃ cakruḥ | yad u śuklam ivābhūd ity apāṃ rūpam iti tad vidāṃ cakruḥ | yad u kṛṣṇam ivābhūd ity annasya rūpam iti tad vidāṃ cakruḥ || ChUp_6,4.6 ||

39.2. He then offers illustrations from nature. “Observe how these elemental forms present themselves, each in its own disguise, in these: Fire, sun, moon, and lightening, the powers – the four that shine”.

“First watch the fire advancing in the woods. It kindles as ‘red’; it is heat we see. It then glows as ‘white’; it is the fluidity in fire that allows it to flow and to spread like streams of water. When it is lowering back into ground as char, it is earth the solid that is presented to our eyes. (Ch.Up.6.4.1)

Next , watch the sun. As it rises, it is red- the color of heat. As it moves up the sky it is white and more white, a brilliant pool of brightness that seethes’ to its brim. It is then in the nature of water, spreading out fluently and relentlessly. And, descending down from its height, it sinks into black on to the solid earth.

Therefore, red, white or black are just putting names to forms of one and the same thing that does not change. The truth is; these are appearances of the three elements that constitute the world, which are born of One reality.” (Ch.Up.6.4.2)

“The moon perchance raises red. Then it slowly turns white and shines; and wanes thereafter. The waters are teeming in, filling it up and passing out again. When these have gone out, we see black. Then it is nature of earth.

Therefore, red, white or black are just putting names to forms of one and the same thing that does not change”. (Ch.Up.6.4.3)

“When lighting breaks all of a sudden it is red, the heat. Next we see the flashes of white that run across the sky as rivers of dazzling light streaming down the mountain rocks in jets of white. It is then the waters. And as it strikes a tree and subsides into its trunk, it turns black.

Here again , the ‘red’ ,’white’ or ‘black’ are mere names we give to the forms we see. But the reality is one which is made of heat, water and earth, the three constituents that make the world; and these three again are enlivened by That Reality.” (Ch.Up.6.4.4)

yad vidyuto rohitaṃ rūpaṃ tejasas tad rūpam |yac chuklaṃ tad apām |yat kṛṣṇaṃ tad annasya | apāgād vidyuto vidyuttvam | vācārambhaṇaṃ vikāro nāmadheyaṃ trīṇi rūpāṇīty eva satyam || ChUp_6,4.4 ||

“Understand then, recognizing by colours and calling by names is similar to assigning names to objects formed, say, of clay, iron or gold etc. The colours too are the visible forms of the three dominant elements, the aspects of That”.

39.3. Thus, Uddalaka suggests that whenever we see an object, we usually see only those aspects which the eyes can see or the senses can grasp; and not its fundamental nature. The colours that we see in objects are really the threefold presence of the elements. No object in the world is independent of the three elements.

39.4. The contrast between the name assigned to a thing and its intrinsic property serves as an introduction to Uddalaka’s teaching on his classification of matter according to degrees of fineness of its essence: coarse, medium and fine.

Food – Body – Mind

40.1. Uddalaka maintains that man consists sixteen parts or fractions (shodasha kala); each equivalent to a day. And, if a person fasts for fifteen days , at the end of the fifteenth day he is exhausted , his psychic functions almost fade away ; and he is left with only one part (prana). It is as if a great fire has burnt out; and is like the dying coal leaving behind just the firefly-sized embers.

[Breath arises from water, according to Uddalaka; and therefore remains despite the fast. On taking food again, the mind is nourished, and its faculties flare up once more like the spark that finds fuel.]

40.2. In order to demonstrate dependence of mind’s working on food or nutrition, Uddalaka proposed an experiment which his son carried out (Ch. Up. 6. 7). Accordingly, Svetaketu abstained from food for fifteen days, but taking only water. At the end of fifteenth day he was unable to recall and recite the hymns he had learnt earlier. On taking food again, his mind was revitalized and his memory returned. This exercise was meant to show the dependence of mind and its working on food and nutrition; and more particularly to demonstrate the unity of body and mind, with life as their common support. In another context, It strengthened the argument that the mind originates from food (anna); and, that mind and matter are indeed the two aspects of the same element.

Assimilation of food in body-parts

41.1. Uddalaka Aruni explains to his son that human beings too are composed of the elements of heat, water and food (solids); and, each of the elements have three different degrees of fineness: the gross, the medium and the subtle. He then elucidates how the food intake contributes to the development of various organs of the body and influences their functions: ‘the foods we consume produce our flesh, blood, mind, life energy (prana), and the rest’. According to him, the highest human functions are composed of the finest degrees of these elements: the organ of thought is composed of the finest degree of food, the life-breath of the finest degree of water; and the speech of the finest degree of heat.

41.2. All that we eat and drink is not absorbed by the body. When the food (including solid, watery and hot substances) is churned and processed in the stomach, its ingredients are separated according to the degree of their fineness, in three ways : gross, medium and fine (Ch.Up.6.5.1).

annam aśitaṃ tredhā vidhīyate | tasya yaḥ sthaviṣṭho dhātus tat purīṣaṃ bhavati |

yo madhyamas tan māṃsam | yo ‘ṇiṣṭhas tan manaḥ || ChUp_6,5.1 ||

As regards the gross: some part of the solids and liquids (food, water and fire principles) are thrown out as ‘ excrement ‘ and so too is ‘ the noisome thing and so set in the bilge for riddance’ ; while some parts of the gross fiery food (ghee, oils etc) are absorbed into bones.

In regard to that which is medium: the medium of food (solids) is absorbed into the flesh ‘the tender wrap that clothes the bones’; the medium of water into the blood ‘ the tide of warming crimson that surges the heart within’; and the medium of the fiery substance goes into the bone marrow.

But, the most subtle and vibratory part which is the essence of all that we consume rises up (just as butter emerges when milk is churned); and goes into the mind and its functions. “ So my dear , the passage from coarse to fine , from dense to subtle , just as with the coagulated milk when churned all its essence rises up above the thickened curd , a crown of shining smooth butter fit to pour upon leaping yajna flames reaching up to the gods” (Ch.Up.6.6.1-2).

The subtlest portion of the solids goes to the mind; the subtlest portion of the watery substances becomes prana (life force) and virility; and the subtlest portion of the hot substances to the speech (Ch.Up.6.6.2-4).

tejasaḥ somyāśyamānasya yo ‘ṇimā sa ūrdhvaḥ samudīṣati | sā vāg bhavati || ChUp_6,6.4 ||

41.3. The thinking faculty of a person is thus influenced by the most subtle essence of what he consumes, comprising the three elements: The mind is made of the finest degree of food (anna) element; the life-breath (prana) and virility are influenced by the finest degree of water elements (apah); and speech (vac) by the finest degree of fiery elements (teja).

42.1. Thus, the three subtle elements (tanmatra) —fire, water and earth—enter into, sustain and become a part of our system. Our senses, our prana, our mind and our speech, are all influenced by the foods and drinks we consume: “The mind is the essence of food; prana of water; and speech of heat. You are made up of these elements”. (Ch.Up.6.5.4)

annamayaṃ hi somya manaḥ |āpomayaḥ prāṇaḥ |tejomayī vāg iti |bhūya eva mā bhagavān vijñāpayatv iti | tathā somyeti hovāca || ChUp_6,5.4 ||

42.2. Uddalaka explains, what we call hunger (ashana) is nothing but the dissolution of the physical food by the element of water and the absorption of it into the system. What you call thirst (pipasa) is similarly the absorption of the water element in the system by the fire principle within us. In short, at each stage, the effect is consumed by the cause and is absorbed into its own self (e.g. food into water; and water into heat) . This process continues until all effects are absorbed into the final cause of all things, where they abide absolutely and completely.

Asana-pipase me, saumya, vijanihiti yatraitat puruso asishati nama, apa eva tad asitam nayante: tad yatha gonayo svanayah purushanaya iti, evam tad apa acakshate asanayeti, tatraitacchungam utpatitam, saumya, vija nihi, nedam amulam bhavishyatiti.

The withdrawal

43.1. Uddalaka asserts; everything comes from That; and, eventually everything is absorbed back into That (Sat). At the time of dissolution, everything reverses in time; the three elements collapse back into the original being. That does not mean the universe that once was, is reduced to nothingness; for, ‘something does not become nothing, just as nothing does not become something’. Uddalaka charts an inward course back to the very sources from which all existence originated. Speech recedes into breath, breath into mind, mind into prana; and prana back to Sat.

43.2. In the case of the individual too this process occurs, no matter whether one is aware of it or not. The process of going back to the source is natural and does not depend on the striving of the individual. But, one who is fully conscious and understands the Reality at each stage of the process gains freedom. It is that such knowing or not-knowing which perhaps makes the difference between knowledge and ignorance

[These ancient texts hold a view, among others, that our universe goes through eternal cycles of expansion followed by withdrawal or collapsing on itself. The process of expansion from the very core of the Universe is analogues to what has come to be called the Big-bang. However, it is preferable not to imagine the initial expansion as a thunderous explosion. It is rather understood as a sudden and a vast expansion on a truly enormous scale; but rather quietly. The theories of creation that are put forth are not merely about the initial outburst, but are more about what happened thereafter.

Here, the expansion or evolution takes place in stages, proceeding from the most subtle to the most gross; and the effect in each stage resides in its cause. And, therefore, it is said,’ it is not possible to get something out of nothing’. Eventually, all matter in existence retrace their steps, each effect collapsing into its cause, and finally into the original cause. That is, until the next cycle of expansion occurs.

The expanding universe is not conceived as a flat surface; but is visualized as curvilinear, bending on itself (Brahmanda – the Great Orb). It is therefore endless (anantha) or infinite. Everything in the universe is curvaceous, one stage leading into another. The sun’s rays too travel in a curved way as snakes do (bhujangana- mita). Even man’s life too is not a flat journey starting at a point and ending at a point-of-no-return; it is a cycle. The course of human life is spherical; just as the capacious globe on which he lives.]

Death of a person

44.1. Coming back to the individual, Death of a person too is a process of withdrawal of prana; which, in effect, is retracing the steps over which the universe came into existence. It is the eventual way back into the ultimate source (Ch.Up.6.15). Thus at the time of death, man reverses, in inward steps, to that being from which he originated. The speech merges into mind, the mind into prana, the prana into heat; and heat, the last to depart, into the Pure Being. In other words, each death is a re-enactment of the eventual withdrawal of universe into its original source. The process of withdrawal and expansion are, as explained, cyclical.

44.2. Uddalaka explains; when a person is fatally ill and facing death, his family gathers around and asks ‘do you know me? Do you recognize the one sitting next?’So long as his senses are awake he is aware of his surroundings and tries answering questions. But, when the senses are withdrawn into mind, the faculty of speech too subsides into the mind (Vang-manasi sampadyate). He might be aware; and might be able to think and to see, but he would not be able to speak. Next, is the absorption of mind into Prana (manah prane), wherein the breathing process continues, life exists, but there is neither thinking nor sensation. Then, the breath (Prana) is withdrawn into fire principle (heat in the system)-(pranah tejasi). When Life (prana) is withdrawn there is neither consciousness nor bodily life. The body thereafter becomes chill. That is to say, the fire element or heat too departs. But, heat is the last to leave the body. It is withdrawn into the Supreme Being – tejah parasyam devatayam – (Ch.Up.6.15.1).

Purusam, saumya, utopatapinam jnatayah paryupasate, janasi mam, janasi mam iti; tasya yavan na van manasi sampadyate, manah prane,

pranah tejasi, tejah parasyam devatayam tavajjanati

Atha yada’sya vanmanasi sampadyate, manah prane, pranastejasi, tejah parasyam devatayam, atha na janati.

Sa ya eso’nima aitad atmyam idam sarvam, tat satyam, sa atma tat-tvam-asi, svetaketo, iti; bhuya eva ma bhagavan vijnapayatv iti; tatha, saumya, iti hovaca

Teaching methods

45.1. Uddalaka’s teaching method is skilful. Throughout his instructions, Uddalaka points to observable phenomena in life and in the surrounding nature. He sets up experiments, one after another, with a view to leading Svetaketu to proper understanding of the subject. He involves Svetaketu in a pattern of activity designed to raise questions in the young man’s mind.

For instance, he does not merely talk about the banyan seed; he gets Svetaketu to look at the fruit, to open it up, to extract the seed and then to break it open. Svetaketu after breaking open the seed reports ‘it is broken Sir’ (binna Bhagavah iti).At that point, when his son’s attention is on the broken seed Uddalaka asks the boy ‘what do you see in it (Kim atra pashyati iti). Svetaketu replies ‘nothing Sir’ (kinchana Bhagavah iti).

Uddalaka explains to his son that finest part in the seed , the subtle essence within the seed which one does not see (yam na nibhalayase) is indeed the true essence (animnah). In it is hidden the big banyan tree (esah mahanya-nagrodhah). Have faith, dear one (sraddhatsva somya iti).

Uddalaka then names and identifies that subtle essence, presenting it as that from which the whole banyan tree grows. He then identifies that subtle unseen essence with Atman, with the Real, and, as that which Svetaketu himself truly is.

“Just as that subtlest unseen essence pervades the tree, Similarly, Sat, subtle and invisible, pervades all existence. That subtle essence Sat is the truth, the Atman (Ch.Up.6.12.3). Everything comes from That and everything merges back into That. It is in all beings. You like the tree and the world, is made of that essence. The evidence of that can be grasped by reasoning and faith. Svetaketu, you are That (tat tvam asi).

sa ya eṣo ‘ṇimaitad ātmyam idaṃ sarvam | tat satyam | sa ātmā | tat tvam asi śvetaketo iti |

That ‘nothingness’ need not be understood as void; that nothingness, however subtle, is never non-existent

The essence of the tree is in that seeming nothingness. The manifest emerges from the un-manifest. The cause, that nothingness, however subtle, is never non-existent. For, nothing can come out of nothing, and nothing can altogether vanish out of existence. Na-asti satah sambhavah; na sata atmahanam.

[Bhagavad-Gita follows this principle saying ‘there is no existence from what does not exist; there is no non-existence from what exists’ (BG; 2.16): Na-sata vidyate bhavo; na-bhavo vidyate Satah]

Uddalaka succeeds in imparting the teaching not through argument but by the force of the experience of Svetaketu as he peers at the ‘nothingness’ at the core of the split banyan seed , and understands it as an image of the nothing, which is the true-Self-of-all.

Similarly, In order to show Atman pervades everything but cannot be seen, he asks Svetaketu to add a chunk of salt into a jug of water. A day later, Svetaketu cannot locate the chunk of salt in the jug of water. However, he learns that even though he cannot see the salt he can taste it in every part of water in the jug. Through this experiment Svetaketu understands that like salt in water, Atman permeates his entire body though it is not directly observable by the senses.

In other examples, Uddalaka instructs his son about Atman by means of comparison with natural processes such as bees making honey, rivers running into ocean; and, sap flowing out of a tree.

45.2. Similarly, Uddalaka teaches his son Svetaketu the dependence of mental faculties on nutrition, by getting him to abstain from all food for fifteen days, save pure water. [Ch. Up. 6. 7]. At the end of fifteen days of fasting, Svetaketu is unable to recall any of the verses he had learnt earlier. Then Uddalaka compares Svetaketu’s temporary loss of memory to the sacrificial fire that has run out of fuel. Uddalaka then asks ‘eat, then you will remember’ (Ch. Up. 6.7.3). Uddalaka explains the connection between nourishment and mental faculties. Svetaketu understands the teaching well because he just had the experience of it.

Shodasa-kalah saumya purusah pancadaoahani masih kamam apah piba, apomayah prano na pibato vicchetsyata iti.

Sa ha pancadacahani na’sa atha hainam upasasada, kim bravimi bho iti, roah, saumya yajumsi samaniti; sa hovaca, na vai ma pratibhanti bho iti.

Tam hovaca, yatha saumya mahato’bhyahitasyaiko’ ngarah khadyota-mantrah parisishtah syat, tena tato’ pi na bahu dahet, evam saumya, te sodasanam kalanam eka kala’tisista syat tayaitarhi vedan nahubhavasi, asana atha me vijnasyasiti.

45.3. All these may be simple teaching methods; yet, they do convey the lessons effectively well. Uddalaka is a good teacher. He comes down to the level of the student and provides illustrative examples, allegories, and images taken from life and nature that are easy to comprehend. The language used too is rich adorned with picturesque descriptions.

46.1. Thus, in the philosophical texts, Uddalaka Aruni was perhaps the first to apply a form of experimental verification . His method of investigation was based in observation of facts (drstanta) and drawing inference by way of induction. Which, in other words, was reasoning and generalization based on observation (than on speculation). The process of his inference moves from the particular to the general, from species to the genus or from appearances to reality.

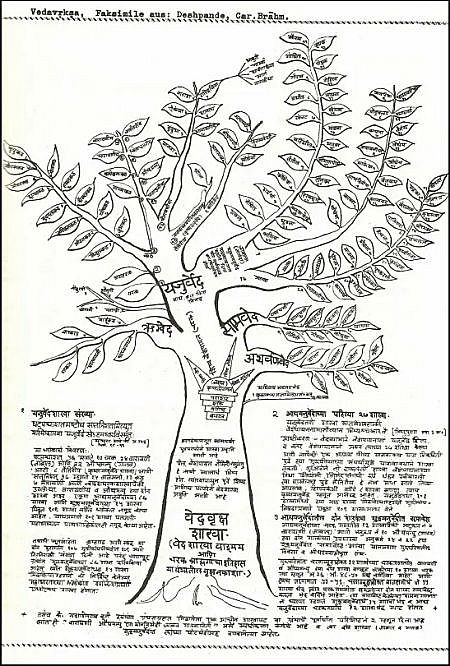

It is said; a prominent landmark in the philosophy of his period was reached in the teachings of Uddalaka Aruni. According to Dr. Benimadhab Barua “ Indian philosophy took a systematic turn in the teachings of Uddalaka; for , it is here that we find different lines of thought branched off to give rise in later times to the fundamental conceptions of Vedanta, Bauddha, Sankhya, Yoga , Nyaya and Vaisesika systems.”

[Uddalaka is credited with initiating a systematic way of investigating into nature. And, he is recognized as a rational thinker who attempted advancing logical proof for the reality of the Being. Yet, it would be incorrect to regard him as a rationalist through and through. Because, he also implicitly pre-supposed the Being as bringing forth primal elements and entering into them, in order to multiply. His approach could perhaps be called ‘rational mysticism’, if such a term exists.

His teachings would become more clear if they are read with passages on similar issues in other Upanishads, particularly the Katha, Mundaka and Svetasvatara Upanishads. ]

47.1. As regards the cognition, Uddalaka neither trusts nor distrusts the sense-perceptions. According to him, the senses provide information from which the knowing mind infers the nature as also the inter- relation of things among themselves. Uddalaka raises the question what can we perceive of objects from the senses? His answer to that is: nothing but sensations and impressions. According to him, power of human cognition is limited, as the knowledge gained through senses is subjective. The senses do not give us the knowledge of the absolute; one has to grasp that in reason and faith. Uddalaka urges Svetaketu: ‘śraddhatsva somyeti; have faith, my dear’ (Ch. Up. 6.12.2).

taṃ hovāca yaṃ vai somyaitam aṇimānaṃ na nibhālayasa etasya vai somyaiṣo ‘ṇimna evaṃ mahānyagrodhas tiṣṭhati | śraddhatsva somyeti || ChUp_6,12.2 ||

48.1. Uddalaka asks his son to exercise the mind which is endowed with fabulous capacity to observe, to reason and infer, in order to gain insight into the Reality. The sum of his assertion is that Self of the world, of him who knows, and of each being around us is one and the same; and it alone is real.

48.2. He advises that when both his intellect and his senses do not help in leading him on the right path, he should then seek guidance from a proper teacher (acharya) who knows. An ardent seeker who finds an illumined teacher attains freedom. And, in the end it is truth that protects.

Sources and References

Life in the Upanishads by Dr. Shubhra Sharma; Abhinav Publications, 1985

The History of Pre-Bhuddhistic Indian Philosophy by Dr .Benimadhab Barua; Motilal Banarsidass, 1921

The Upanishads by Ekanath Easwaran and Michael N Nagler; Nilgiri Press, 2007.

A Course in Indian Philosophy by AK Warder, Motilal Banarsidass, 2009

Indian Philosophy before the Greeks by David J Melling

Atman in pre-upanisadic Vedic literature By H G. Narahari; published by Adyar Library 1944.

http://www.archive.org/details/atmaninpreupanis032070mbp

http://www.rationalvedanta.net/node/126

What the Upanishads teach

http://www.suhotraswami.net/library/What_the_Upanisads_Teach.pdf

The Chandogya Upanishad by Swami Krishnananada

http://www.suhotraswami.net/library/What_the_Upanisads_Teach.pdf

Vedanta Philosophy in the Light of Modern Science by S.K. Dey

http://satenupriedas.110mb.com/Vedanta.pdf

Svetaketu

http://atmajyoti.org/up_chandogya_upanishad_9.asp

The Secret Lore of India and the One Perfect Life for All, By W. M. Teape, B.D. (Cambridge: 1932

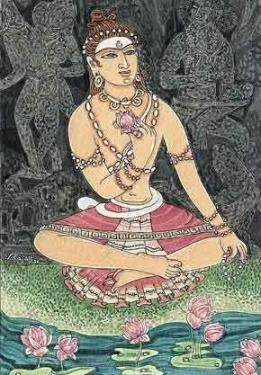

PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET

(Tantric Lakshmi)

(Tantric Lakshmi)

According to the story, on one rainy night the teacher Ayoda-Dhaumya asked Aruni to supervise water flowing through a certain field. When Aruni went there, he found the dyke had breached and the water was seeping out. Aruni tried to plug the breach and to stop the leak, but was not successful. Aruni then lay down on the breach; stopping the water flow with his body. He lay there the entire night. The next morning, the teacher Dhaumya along with other students came in search of Aruni; and found the boy stretched out along the dyke trying to stop the outflow of water. Dhaumya was deeply impressed with the dedication and sincerity of Aruni. On seeing his teacher, Aruni stood up. And, as he did so, the water began to flow out.

According to the story, on one rainy night the teacher Ayoda-Dhaumya asked Aruni to supervise water flowing through a certain field. When Aruni went there, he found the dyke had breached and the water was seeping out. Aruni tried to plug the breach and to stop the leak, but was not successful. Aruni then lay down on the breach; stopping the water flow with his body. He lay there the entire night. The next morning, the teacher Dhaumya along with other students came in search of Aruni; and found the boy stretched out along the dyke trying to stop the outflow of water. Dhaumya was deeply impressed with the dedication and sincerity of Aruni. On seeing his teacher, Aruni stood up. And, as he did so, the water began to flow out.