According to Abhinavagupta

As mentioned in the previous Part, it is explained that the process of manifestation of speech, like that of the Universe, takes place in four stages.

First, in the undifferentiated substratum of thought an intention appears. This first impulse, the self-radiant consciousness (Sva-prakasha-chaitanya) is Para-vac (the voice beyond).

Thereafter, this intention takes a shape. We can visualize the idea (Pashyanthi-vac) though it is yet to acquire a verbal form. It is the first sprout of an invisible seed; but, yet searching for words to give expression to the intention. This is the second stage in the manifestation of the idea.

Then, the potential sound, the vehicle of the thought, materializes, finding words suitable to express the idea. This transformation of an idea into words, in the silence of the mind, is the third stage. It is the intermediary stage (Madhyama-vac) between un-manifest and manifest.

The fourth stage being manifestation of the till then non-vocal verbalized ideas into perceptible sounds. It is the stage where the ideas are transmitted to others through articulated audible syllables (Vaikhari-vak).

These four stages are the four forms of the word.

**

In this part, let’s talk about the theories expounded and the explanations offered by two of the great thinkers – Abhinavagupta and Bhartrhari – on the subject of different levels of speech or awareness.

While Bhartrhari regards levels of speech as three (Pashyanti, Madhyama and Vaikhari), Abhinavagupta discusses on four levels (Para, Pashyanti, Madhyama and Vaikhari).

Some scholars have tried to reconcile that seeming difference between the stance of the two eminent personalities by explaining that Bhartrhari’s concept of the speech-principle Sabda-tattva or Sabda-brahman the fundamental basis of the all existence, virtually equates to Para Vac , the Supreme Consciousness adored by Abhinavagupta. In this connection, they remind of a passage in Bhartrhari’s Vritti on his Vakyapadiya where the description of Paśyantī Vac is followed by a subtle hint at a paraṃ paśyantī – rūpam, which they take it as pointing towards Abhinavagupta ‘s Parā Vāc.

**

Let’s briefly take a look at the theories expounded by Abhinavagupta on various stages of language, speech and consciousness.

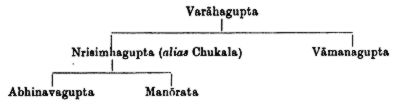

Abhinavagupta Acharya (Ca. 950 to 1020 C.E) the great philosopher, mystic and a true sadhaka, was the intellectual and a spiritual descendant of Somananda the founder of the Pratyabhijna School of Kashmiri Shaiva monism. He was a many sided genius; a visionary endowed with incisive intellectual powers of a philosopher who combined in himself the experiences of a spiritualist and a Tantric. He was a prolific writer on Philosophy, Tantra, Aesthetics, Natya, Music and a variety of other subjects. His work Tantraloka in which he expounds Anuttara Trika, the ‘most excellent’ form of Trika Shaivism (Nara- Shakthi- Shivatmakam Trikam) is regarded as his magnum opus. It is a sort of an encyclopedia on Tantra – its philosophy, symbolism and practices etc.

Abhinavagupta was also a scholar-commentator par excellence, equipped with extraordinary skills of an art critic. The noted scholar Bettina Baumer describes Abhinavagupta as one of the most remarkable , extraordinary thinkers of India – perhaps the most exceptional one by the breadth of his interests and talents ,his acumen and profoundness . He was a master of Sanskrit in all its forms and subtilties. There is hardly any scholar who can be compared to Abhinavagupta, who while rooted in tradition (Sampradaya-vit) , is endowed with the genius to combine an enormous range of subjects and fields of studies with the depths of mystical experience and philosophical insights.

His South Indian ascetic disciple Madhuraja , in his eulogy on his Guru (Guru-natha-paramarsa) mentions that Abhinavagupta (Abhinavaguptah Sriman-Acharya-pada) was a Master in various traditions of Tantra-Vidya ; such as : Siddantha , Vama Bhairava, Yamal-Kaula -Trika-Ekavira.

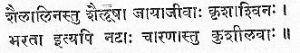

Siddantha-Vama-Bhairava-Yamala-Kaula-Trika-Ekaviratantram / Abhinavaguptah Sriman-Acharya-pade sthito jayathi//

Among his notable commentaries are: the Īśvarapratyabhijñā-vimarśini and its detailed version Isvara-pratyabhijña-vivrti-vimarsini, both being commentaries on Isvara-Pratyabhijña – kārikā and vṛtti (Recognition of Shiva as self) by Utpaladeva or Utpalācārya (early 10th century), an earlier philosopher of the Pratyabhijñā Darśhana School. And, Abhinavagupta’s Paratrisika-Laghuvritti (also known as the Anuttara-tattva-vimarsini) and its expanded form Parātrīśikā–vivarana a commentary on Parātrīśikā also known as the Trikasūtra (a seminal text on Kashmiri Shaivism) – which is based in the concluding portion of the Rudra-yamala-tantra – is held in very high esteem.

[ The title Parātrīśikā–vivarana is ordinarily translated to mean ‘the thirty-six verses in praise of the Supreme’. But, Abhinavagupta did not seem to accept such a commonplace explanation. This Tantra or Sutra or the revealed Text (in the form a dialogue between the Devi and Bhairava) ; the essence of the Rudra-yamala-Tantra ; according to him, brings to light the manifold Truths; and, can be understood in a variety of ways. It , among other things, ably illustrates the eternal principle – Sarvam Sarvatmakam – everything is related to everything else.

He, therefore, preferred to interpret the term Parātrīśikā to refer to ‘the Supreme Goddess who transcends; and, represents the Trika (Trinity)’.

The Three , here, could variously refer to: the Shakthis , Iccha , Jnana and Kriya ; Or, three states of Reality : Para, Parapara and Apara; Or, the three states of existence: Sristi, Sthithi and Samhara; Or, the three levels of Shiva, Shakthi and Nara; Or, as that which speaks out (Kyathi) the three (Tri) Shakthis (Sa) of the Supreme (Para).

The text Parātrīśikā has also been called Anuttara-prakriya, the essence of ultimate knowledge, signifying the great importance accorded to this text in the Kashmir Shaiva tradition. It is often said there is no knowledge higher than Prakriya (Na Prakriya-param jnanam). It is revered as a sacred text , which indeed is a ocean or a treasure of Shiva-knowledge (Tat-sarvam kathitam Devi Shiva-jnana-maha-dadhau) .That is because; here, Lord Bhairava answers the questions of Devi, which are related to ‘the great secret’ (Etad guhyam, maha guhyam).

The text, therefore, is also referred to as Trika-shastra- rahasya –upadesha (the teaching of the Trika doctrine); primarily addressed to the advanced disciples or to the enlightened ones (Nija-shihya-vibodhaya-prabuddha-samaranaya). Abhinavagupta, in fact, interprets the term Anuttara in as many as sixteen ways.

Abhinavagupta concludes by stating : The Yogi who directs all things, beings ,elements, states, worlds etc., to be in unity with his own consciousness , implicitly, he himself is Bhairava , the Supreme Lord-Parameshvara.

- Samvide-ekatmata-anita-bnuta-bhava-puradhikah/

- avyava-avicchinna-samvittir- Bhairava Parameshvarah //]

And, his work Abhinavabharati though famed as a commentary on Bharata’s Natyasastra is, for all purposes, an independent treatise on aesthetics in Indian dance, poetry, music and art; and , it helps in understanding Bharata and also a number of other scholars and the concepts they had put forth. The Abhinavabharati along with his other two works – Isvara pratyabhijna Vimarshini and Dhvanyaloka Lochana – are highly significant works in the field of Indian aesthetics.

[For more on Abhinavagupta, please click here]

Generally speaking, the Tantra-s of all tendencies deal with the nature of Vac and its manifestations. But, the tradition to which Abhinavagupta belonged – namely the Bhairava Tantra, and in particular to the Kula and Trika Tantras – differs from the others in that it bestows greater importance to the nature and to the role of Vac. It views Vac (language) at its highest level as identical with the Supreme Reality.

Abhinavagupta’s ideas and concepts with regard to language are based in the scriptures of his School and in his philosophy of language. Abhinavagupta’s speculations on the nature, on the levels of Vāc and its manifestations are, therefore, some of the important aspects of all his works. They run like a thread that ties together the diverse aspects of Abhinavagupta’s vast body of works. The speculations on Vac also interweave his views on the religious and philosophical traditions that he expounds.

According to the Pratyabhijna School, Shiva is the Ultimate Reality; and, the individual and Shiva are essentially one. The concept of Pratyabhijna refers to self-awareness (parämarsa); to the way of recognition and realization of that identity. It firmly asserts that the state of Shiva-consciousness is already there; you have to realize that; and, nothing else. As Abhinavagupta puts it: Moksha or liberation is nothing but the awareness of one’s own true nature – Moksho hi nama naivathyah sva-rupa-pratanam hi tat.

Abhinavagupta, while explaining this school of recognition, says, man is not a mere speck of dust; but is an immense force, embodying a comprehensive consciousness; and, is capable of manifesting , through his mind and body, limitless powers of knowledge and action (Jnana Shakthi and Kriya Shakthi).

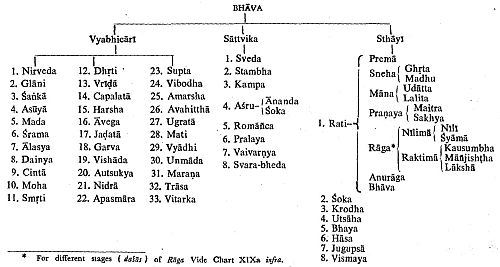

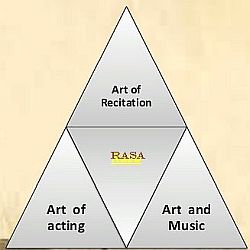

According to the Tantras of Kashmir Shaiva tradition, which recapture the ancient doctrine of Sphota, the manifestation of all existence is viewed as the expression of Shiva (visarga-shakthi) occurring on four levels. These represent the process of Srsti or outward movement or descending or proceeding from the most sublime to the ordinary. It is said; such four levels of evolution correspond with the four levels of consciousness or the four levels in the unfolding (unmesa) of speech (Vac).

Just as a Samkalpa (a pure thought or will) has to pass through several stages before it actually manifests as a concrete creative force, so also the Vac has to pass through several stages before it is finally audible at the gross level as Sabda (sound). Each level of Vac corresponds to a different level of existence. Our experience of Vac depends upon the refinement of our consciousness.

Abhinavagupta , a master of the Pratyabhijna School of philosophy, accepted four different stages in the evolution of Sabda Brahman , originating from Para.

The latent, un-spoken, un-manifest, silent thought (Para) unfolds itself in the next three stages as pashyanti (thought visualized), Madhyamā (intermediate) and Vaikhari (explicit) speech).

Though the speech (Vac) is seen to manifest in varied levels and forms, it essentially is said to be the transformation (Vivarta) of Para Vac, the Supreme consciousness (Cit), which is harboured within Shiva in an undifferentiated (abheda) unlimited form (Swatrantya).

*

Abhinavagupta describes Parā vāk as a luminous vibration (sphurattā) of pure consciousness in an undifferentiated state (paramam vyomam). While Shiva is pure consciousness (Prakasha); Devi is the awareness of this pure light (Vimarsha).

It is highly idealized; and, is akin to a most fabulous diamond that is also aware of its own lustre and beauty.

The two – Prakasha and Vimarsha – are never apart. The two together are manifest in the wonder and joy (Chamatkara) of Para vac. And, there is no knowledge, no awareness, which is not connected with a form of Para vac.

The Devi, as Parā Vāc, the vital energy (prana shakthi) that vibrates (spanda) is regarded as the foundation of all languages, thoughts, feelings, and perceptions; and, is, therefore, the seat of consciousness (cit, samvid). Consciousness, thus, is inseparable from the Word, because it is alive.

Vac (speech), he says, is a form of expression of consciousness. And, he argues, there could be no speech without consciousness. However, Consciousness does not directly act upon the principle of speech; but, it operates through intermediary stages as also upon organs and breath to deliver speech.

Thus, Vac is indeed both speech and consciousness (chetana), as all actions and powers are grounded in Vac. Abhinavagupta says: Someone may hear another person speak, but if his awareness is obscured, he is unable to understand what has been said. He might hear the sounds made by the speaker (outer layer of speech); but, he would not be able to grasp its meaning (the inner essence – antar-abhiläpa)).

**

Abhinavagupta explains the process of evolution (Vimarsa) of speech in terms of consciousness, mind and cognitive activity (such as knowing, perceiving, reasoning, understanding and expressing).

In his Īśvara-pratyabhijñā-viṛti-vimarśinī Abhinavagupta says: the group of sounds (Sabda-rasi) is the Supreme Lord himself; and, Devi as the array of alphabets (Matraka) is his power (Shakthi) .

iha tāvat parameśvaraḥ śabdarāśiḥ, śaktir asya bhinnābhinnarūpā mātṛkādevī, vargāṣṭakaṃ rudraśaktyaṣṭakaṃ pañcāśad varṇāḥ pañcāśad rudraśaktayaḥ

Abhinavagupta says: “When She (Parā vāc) is differentiating then she is known in three terms as Pašhyantī, Madhyamā, and Vaikharī.”

The Kashmir Shaiva tradition, thus, identifies the Supreme Word, the Para Vac with the power of the supreme consciousness, Cit of Shiva – that is Devi the Shakthi.

According to Abhinavagupta, the Vac proceeds from the creative consciousness pulsations (spanda) of the Devi as Para-Vac, the most subtle and silent form of speech-consciousness. And then, it moves on, in stages, to more cognizable forms:

Pashyanti (Vak-shakthi , going forth as seeing , ready to create in which there is no difference between Vachya– object and Vachaka – word); Madhyamā (the sabda in its subtle form as existing in the anthahkarana or antarbhittï prior to manifestation); and , Vaikhari (articulated as gross physical speech).

This is a process of Srsti or outward movement or descending proceeds from the most sublime to the mundane.

It is said; the gross aspect (sthūlaṃ) of nāda is called ‘sound’; while the subtle (sūkṣmaṃ) aspect is made of thought (cintāmayaṃ bhavet); and, the aspect that is devoid of thought (cintayā rahitaṃ) is called Para, the one beyond

Sthūlam śabda iti proktaṃ sūkṣmaṃ cintāmayaṃ bhavet | cintayā rahitaṃ yat tu tat paraṃ parikīrtitam |

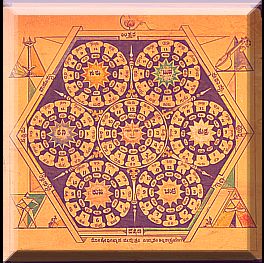

[This is similar to the structure and the principle of Sri Chakra where the consciousness or the energy proceeds from the Bindu at its centre to the outward material forms.

The Bindu or dot in the innermost triangle of the Sri Chakra represents the potential of the non-dual Shiva-Shakti. When this potential separates into Prakasha and Vimarsha it is materializes into Nada, the sound principle.]

There are also other interpretations of the four stages in the evolution of Vac.

It is also said; the stages of Para,Pashyanti, Madhyamā and Vaikhari correspond to our four states of consciousness – Turiya ( the transcendental state); Sushupti (dreamless state); Swapna (dreaming state), and Jagrut (wakeful state).

-

-

- Thus, Para represents the transcendental consciousness,

- Pashyanti represents the intellectual consciousness,

- Madhyamā represents the mental consciousness, and

- Vaikhari represents the physical consciousness.

-

Our ability to experience different levels depends upon the elevation of our consciousness.

The three lower forms of speech viz. Pashyanthi, Madhyama and Vaikhari which correspond to intention, formulation and expression are said to represent iccha-shakthi (power of intent or will), jnana-shakthi (power of knowledge) and kriya-shakthi (power of action) of the Devi .

These three are construed as the three sides of the triangle at the centre of which is the dot-point (bindu) representing the undifferentiated notion Para-vac. The triangle with the Bindu at its centre suggests the idea of Isvara the divinity conceived as Sabda-Brahman.

Rāmakantha (aka Rājānaka Rāma; Ca. 950 CE) in his commentary (Vritti) on Spandakārikā, explains, “The speech is indeed an action, the mediating part of the Word is made of knowledge, the will is its visionary part, which is subtle and is common essence in all [of them].”

Vaikharikā nāma kriyā jñānamayī bhavati madhyamā vāk/ Icchā punaḥ pašyant ī sūkṣmā sarvāsāṃ samarasā vṛttiḥ/ /

:-According to the Yoga School, the Para stage manifests in the Karanabindu in Muladhara chakra; and then it passes through Manipura and Anahata chakras that denote Pashyanti and Madhyama states of sound. And, its final expression or Vaikhari takes place in Vishudhi chakra.

:-According to the Yoga School, the Para stage manifests in the Karanabindu in Muladhara chakra; and then it passes through Manipura and Anahata chakras that denote Pashyanti and Madhyama states of sound. And, its final expression or Vaikhari takes place in Vishudhi chakra.

The Yoga Kundalini Upanishad explains thus: “The Vac which sprouts in Para gives forth leaves in Pashyanti; buds forth in Madhyamā, and blossoms in Vaikhari.”

:-The Tantra worships Devi as Parā Vāc who creates, sustains and dissolves the universe. She is the Kuṇḍalinī Śkakthi – the serpent power residing in the human body in the subtle form coiling around the Mūladhāra Chakra

According to Abhinavagupta, the Para Vac is always present and pervades all the levels of speech; and, is indeed present on all the levels from the highest to the lowest. By its projection, it creates the flash of pašyantī vāc, the intellectual form; and finally the articulate form, the Vaikhari. He also says that without Her (parā vāk), darkness and unconsciousness, would prevail.

pašyantyādi dašasv api vastuto vyavasthitā tayā vinā / pašyantyādiṣu aprakāšatāpattyā jaJaṭā-prasaṅgāt /

“Everything (sarvasarvātmaiva); stones, trees, birds, human beings, gods, demons and so on, is but the Para Vac present in everything and is, identical with the Supreme Lord.”

ata eva sarve pāšāṇa-taru-tiryaṅ-manuṣya-deva-rudra-kevali -mantratadīša- tanmahešādikā ekaiva parābhaṭṭārikā-bhūmiḥ sarva-sarvātmanaiva paramešvara- rūpeṇāste

Thus, the entire process of evolution of Vac is a series of movements from the centre of Reality to the periphery, in successive forms of Para-Vani.

Abhinavagupta states: Shiva as Para is manifested in all the stages, from the highest to the lowest, right up to the gross sound through his Shakthi; and, he remains undivided (avibhaga vedanatmaka bindu rupataya).

To put the entire discussion in a summary form:

:- According to the explanations provided here: Para is the highest manifestation of Vac. Para and Pashyanti are inaudible; they are beyond the range of the physical ear; and so is Madhyama which is an internal dialogue.

Thus, it is said, there are three stages in the manifestation of Vac: Para (highest); Sukshma (subtle – Pashyanti and Madhyama); and, Sthula (gross – Vaikhari)

Para, the transcendent sound, is beyond the perception of the senses; and, it is all pervading and all encompassing. Para is pure intention. It is un-manifest. One could say, it is the sound of one’s soul, a state of soundless sound. It exists within all of us. All mantras, infinite syllables, words, and sentences exist within Para in the form of vibration (Spanda) in a potential form.

Para-Vani or Para Vac, the Supreme Word, which is non-dual (abeda) and identified with Supreme consciousness, often referred to as Sabda Brahma, is present in all the subsequent stages; in all the states of experiences and expressions as Pashyanti, Madhyamā and Vaikhari.

*

:- Pashyanti , which also means the visual image of the word, is the first stage of Speech. It is the intuitive and initial vision; the stage preceding mental and verbal expression.

Paśyantī is prior to sprouting of the language or ‘verbalization’, still potent and yet to unfold. Pasyanti, says Abhinavagupta, is the first moment of cognition, the moment where one is still wishing to know rather than truly knowing.

In Pashyanti (Vak-shakthi, going forth as seeing, ready to create) there is no difference between Vachya – object and Vachaka – word. The duality of subject-object relation does not exist here. Pashyanti is indivisible and without inner-sequence; meaning that the origin and destination of speech are one, without the intervention of mental constructs (Vikalpa). Paśyantī is the state of Nirvikalpa.

It is the power of intent or will (Icchāśakti) that acts in Paśhyantī state. And yet, it carries within itself the potentials of the power of cognition, jñāna šhakthi, and the power of action, kriyā šhakthi.

*

:- Madhyama is an intellectual process, during which the speaker becomes aware of the word as it arises and takes form within him; and, grasps it. Madhyama vac is a sequenced but a pre-vocal thought, Here, the sound is nada; and, is in a wave or a vibratory (spandana) form.

Madhyamā is the intermediate stage (madhyabhūmi) of thinking. It is the stage at which the sabda in its subtle form exists in the anthahkarana (the internal faculty or the psychological process, including mind and emotions) – prior to manifestation) as thought process or deliberation (chintana) which acts as the arena for sorting out various options or forms of discursive thought (vikalpa) and choosing the appropriate form of expression to be put out.

The seat of Madhyamā, according to Abhinavagupta, is intellect, buddhi. Madhyamā represents conception and internal articulation of the word- content. Madhyamā is the stage of Jñānaśakti where knowledge (bodha) or the intellect is dominant. It is the stage in which the word and its meaning are grasped in a subject-object relationship; and, where it gains silent expressions in an internal-dialogue.

*

:- And, finally, Vaikhari Vac is sequenced and verbalized speech, set in motion according to the will of the person who speaks. For this purpose, he employs sentences comprising words uttered in a sequence. The word itself comprises letters or syllables (varnas) that follow one after the other.

Vaikhari is the articulated speech, which in a waveform reaches the ears and the intellect of the listener. Vaikhari is the physical form of nada that is heard and apprehended by the listener. It gives expression to subtler forms of vac.

The Vaikhari (which is related to the body) is the manifestation of Vac as gross physical speech of the ordinary tangible world of names and forms. Vaikharī represents the power of action Kriyāśakti. This is the plane at which the Vac gains a bodily- form and expression. Until this final stage, the word is still a mental or an intellectual event. Now, the articulated word comes out in succession; and, gives substance and forms to ones thoughts. Vaikharī is the final stage of communication, where the word is externalized and rendered into audible sounds (prākṛta dhvani).

There are further differences, on this plane, between a clear and loud pronunciation (Saghosha) and a one whispered in low voice (aghosha), almost a sotto voce. Both are fully articulated; what distinguishes them is that the former can be heard by others and the latter is not.

*

That is to say; Vac originates in consciousness; and, then, it moves on, in stages, to more cognizable forms : as Pashyanti, the vision of what is to follow; then as Madhyama the intermediate stage between the vision and the actual; and , finally as Vaikhari the articulated , fragmented, conventional level of everyday vocal expressions.

Thus, the urge to communicate or the spontaneous evolution of Para, Pashyanti into Vaikhari epitomizes, in miniature, the act of One becoming Many; and the subtle energy transforming into a less- subtle matter. Thus, the speech, each time, is an enactment in miniature of the progression of the One into Many; and the absorption of the Many into One as it merges into the intellect of the listener.

While on Abhinavagupta, we may speak briefly about the ways he illustrates the relation that exists between Shiva, Devi and the human individual, by employing the Sanskrit Grammar as a prop.

In the alphabetical chart of the Sanskrit language, A (अ) is the first letter and Ha (ह) is the last letter. These two, between them, encompass the collection of all the other letters of the alphabets (Matrka).

Here, the vowels (Bija – the seed) are identified with Shiva; and, the consonants are wombs (yoni), identified with Shakthi. The intertwined vowels and consonants (Malini) in a language are the union of Shiva and Shakthi.

[ In the Traika tradition, the letters are arranged as per two schemes: Matrka and Malini.

Here, Matrka is the mother principle, the phonetic creative energy. Malini is Devi who wears the garland (mala) of fifty letters of the alphabet.

The main difference between the Matrka and Malini is in the arrangement of letters.

In Matrka , the letters are arranged in regular order ; that is , the vowels come first followed by consonants in a serial order.

In Malini, the arrangement of letters is irregular. Here, the vowels and consonants are mixed and irregular; there is no definite order in their arrangement.

While Matrkas are compared to individual flowers, the Malini is the garland skillfully woven from those colorful flowers.]

According to Abhinavagupta, word is a symbol (sanketa). The four stages of Vac: Para, Pashyanti, Madhyamā and Vaikhari represent the four stages of evolution and also of absorption ascent or descent from the undifferentiated to the gross.

Abhinavagupta then takes up the word AHAM (meaning ‘I’ or I-consciousness or Aham-bhava) for discussion. He interprets AHAM (अहं) as representing the four stages of evolution from the undifferentiated to the gross (Sristi); and, also of absorption (Samhara) back into the primordial source. In a way, these also correspond to the four stages of Vac: Para, Pashyanti, Madhyama – and Vaikhari.

*

He explains that the first letter of that word – A (अ) – represents the pure consciousness Prakasha or Shiva or Anuttara, the absolute, the primal source of all existence. It also symbolizes the initial emergence of all the other letters; the development of the languages.

And, Ha (ह) is the final letter of the alphabet-chart; and, it represents the point of completion when all the letters have emerged. Ha symbolizes Vimarsha or Shakthi, the Devi. The nasal sound (anusvāra) which is produced by placing a dot or Bindu on ‘Ha’ (हं) symbolises the union of Shiva and Shakthi in their potent state.

The Bindu (◦) or the dimension-less point is also said to represent the subtle vibration (spanda) of the life-force (Jiva-kala) in the process of creation. Bindu symbolizes the union of Shiva and Shakthi in their potent state (Shiva-Shakthi-mithuna-pinda). It stands at the threshold of creation or the stream of emanation held within Shiva. It is the pivot around which the cycle of energies from A to Ha rotate. Bindu also is also said to symbolize in the infinite nature (aparimitha-bhava) of AHAM.

*

As regards and the final letter M (ह्म) of the sound AHAM ( written as a dot placed above the letter which precedes) , providing the final nasal sound, it comes at the end of the vowel series, but before the consonants. It is therefore called Anusvara – that which follows the Svaras (vowels). And, it represents the individual soul (Purusha).

*

Abhinavagupta interprets AHAM as composed of Shiva; the Shakthi; and the Purusha – as the natural innate mantra the Para vac.

In the process of expansion (Sristi), Shiva, representing the eternal Anuttara, which is the natural, primal sound A (अ) , the life of the entire range of letter-energies (sakala-kala-jaala-jivana –bhutah) , assumes the form of Ha’ (हं) the symbol of Shakthi; and, then he expands into Bindu (◦) symbolizing phenomenal world (Nara rupena).

Thus, AHAM is the combine of Shiva-Shakthi that manifests as the world we experience. Here, Shakthi is the creative power of Shiva; and it is through Shakthi that Shiva emerges as the material world of human experience. AHAM , therefore, represents the state in which all the elements of experience, in the inner and the outer worlds, are fully displayed. Thus, Shakthi is the creative medium that bridges Nara (human) with Shiva.

**

At another level, Abhinavagupta explains: The emergence (Visarga) of Shakthi takes place within Aham. She proceeds from A which symbolizes unity or non-dual state (Abedha). Shakthi as symbolized by Ha represents duality or diversity (bedha); and, the dot (anusvara or bindu) on Ha symbolizes bedha-abeda – that is, unity transforming into diversity. The Anusvara indicates the manifestation of Shiva through Shakthi ; yet he remains perfect (undivided) – Avi-bhaga-vedanatmaka bindu rupataya.

These three stages of expansion are known as :

- Para visarga;

- Apara visarga; and

- Para-apara visarga.

Here, Para is the Supreme state, the Absolute (Shiva) ; Para-apara is the intermediate stage of Shakthi, who is identical with Shiva and also different; she is duality emerging out of the undifferentiated; and, Apara is the duality that is commonly experienced in the world.

Aham (अहं), in short, according to Abhinavagupta, encapsulates the process of evolution from the undifferentiated Absolute (Shiva) to the duality of the world, passing through the intermediate stage of Bheda- abeda, the threshold of creation, the Shakthi. All through such stages of seeming duality , Shiva remains undivided (avibhaga vedanatmaka bindu rupataya).

The same principle underlines the transformation, in stages, of the supreme word Para Vac the Supreme Word, which is non-dual and identified with Supreme consciousness, into the articulate gross sound Vaikhari.

**

[ Abhinavagupta in his Paratrisika Vivarana says : In all the dealings , whatever happens , whether it is a matter of knowledge (jnana) or action (kriya) – all of that arises in the fourth state (turyabhuvi) , that is in the Para-vac in an undifferentiated (gatabhedam ) way. In Pashyanti which is the initial field in the order of succession (kramabhujisu) there is only a germ of difference. In Madhyamā, the distinction between jneya (the object of knowledge) and karya (action) appears inwardly, for a clear-cut succession or order is not possible at this stage (sphuta-kramayoge).

Moreover , Pashyanti and Madhyamā fully relying on Para which is ever present and from which there is no distinct distinction of these (bhrsam param abhedato adhyasa) (later ) regards that stage as if past like a mad man or one who has got up from sleep.

*

Abhinavagupta in his Para-trisika Varnana explains and illustrates the Tantric idiom ‘sarvam sarvatmakam’: everything is related to everything else. The saying implies that the universe is not chaotic ; but , is an inter-related system. The highest principle is related to the lowest (Shiva to the gross material object) .

Abhinavagupta illustrates this relation by resorting to play on the letters in the Sanskrit alphabets, and the tattvas or the principles of reality.

He says “ the first is the state of Pasu , the bound individual; the second is the state of jivanmukta or of the Pathi , the Lord himself for : khechari –samata is the highest state of Shiva both in life and in liberation”- tad evaṃ khecarī sāmyam eva mokṣaḥ . Khechari is the Shakthi moving in free space (kha) , which is an image of consciousness. Khechari-samaya is described as the state of harmony and identity with the Divine I-consciousness-

Akritrima-aham-vimarsha — yena jñātamātreṇa khecarīsāmyam uktanayena]

**

[Again , on a play of letters , Abhinavagupta states the three pronouns I (aham ) , you (tvam ) and he/she/it (sah) are a part of the triadic structure of the Reality (sarvam traika-rupam eva ) and they are to be related to nara (he or it ) , Shakthi (you) and Shiva (I). The three again are related to three levels of Apara, Parapara and Para (the lowest or the objective; the intermediate; and, the transcendent level). But, since the trinity is neither rigid nor static; but , is a fluid system of relations where one can be transformed into another, the lower can be assumed to be the higher . And, all types of interaction among the tree levels is possible.

For instance, the third person, which may even be a life-less object, if it is addressed personally might become ‘you’ and thus assume the Shakthi-nature of the second person you,’ Mountain’. Similarly, the same object in third person can be transformed into first person ‘I’. Take for instance when Krishna declares in the Bhagavad-Gita ‘Among the mountains, I am Meru’.

And, a person or ‘I’ addressing another person or ‘you’ experiences a kind of fusion with the ‘I’ of his self with the ‘I’ of the listener. That common or the shared feeling of ‘I’ binds the two together in delight (chamatkara) and release (svatantra) from the isolation of limited self. Here, communication brings about close association or union in the same Ahambhava.

The pure, unbound ‘I’ is Shiva who is self-luminous consciousness. The notion of ‘you’, the second person, though indicative of ‘separateness’, is actually similar to that of ‘I’. Therefore, both ‘you’ and ‘I’ are described as genderless.

Abhinavagupta presents several examples to show how the three grammatical ‘persons’ are interrelated and merge into each other. This he does in order to explain how everything, even the inert object, is related to the absolute –“I’ consciousness of Shiva.

Even the ‘numbers’ – singular, dual and plural – are related to the three principles of Traika : singular being Shiva; the dual being Shakthi ; and, nara , the multiplicity of the objective world. The merging of the many (anekam – plurality) into unity (eka) of Shiva signifies release from bondage (anekam ekadha krtva ko no muchtyata bandhat : Ksts )

This is how Abhinavagupta analyzes grammatical structures to explain the relatedness as also the essential unity in creation. As he says: the rules of Grammar reflect consciousness; and , there is no speech which does not reach the heart directly (Ksts).

**

In another play on words, Abhinavagupta turns Aham backwards into Maha; and, interprets it to mean the withdrawal (Samhara) or absorption of the material existence into the primordial state. Here again, in MAHA, the letter Ma stands for individual; Ha for Shakthi; and, A for Shiva (Anuttara the ultimate source).

In the reverse movement (Parivartya – turning back or returning to the origin), Ma the individual (Nara) is absorbed into Shakthi (Ha) which enters back into the Anuttara the primal source the Shiva (A). That is; in the process of withdrawal, all external objects come to rest or finally repose in the ultimate Anuttata aspect (Aham-bhava) of Shiva.

Thus the two states of expansion (sristi) and withdrawal (samhara) are pictured by two mantras Aham and Maha.

In both the cases, Shakthi is the medium. In Aham, it is through Shakthi that Shiva manifests as multiplicity. And, in Maha, Shakthi, again, is the medium through which the manifestation is absorbed back into Shiva.

She, like the breath, brings out the inner into the outer; and again, draws back the outside into within. That is the reason Shakthi is often called the entrance to Shiva philosophy (Shaivi mukham ihocyate).

**

In short :

In the process of expansion, the eternal Anuttara, Shiva is the form of ‘A’ which is the natural, primal sound, the life of the entire range of letter-energies (sakala-kala-jaala-jivana –bhutah) . He, in the process of expansion ,assumes ‘ha’ form (the symbol of Shakthi) , for expansion (visarga) is the form of ‘ha’ , the kundalini-shakti ; and then he expands into a dot symbolizing objective phenomenon (nara rupena) and indicative of the entire expansion of Shakthi ( entire manifestation) with Bhairava .

Thus , the expansion is in the form of Aham or I , The return or the withdrawal is in the form of Maha.

This the great secret , this is the source of the emergence of the universe. And , also by the delight emanating from the union of the two Shiva and Shakthi .

**

Abhinavagupta remarks: this is the great secret (Etad Guhyam Mahaguhyam); this is the source of the emergence of the universe; and, this is the withdrawal of the mundane into the sublime Absolute. And, this also celebrates the wonder and delight (Chamatkara) emanating from the union of the two Shiva and Shakthi.

[Abhinavagupta’s system is named Visesha-shastra the secret knowledge as compared to Samanya –shastra , the basic teachings of Shaiva siddantha.]

***

[In all the voluminous and complex writings of Abhinavagupta, the symbolism of Heart (Hrudaya) plays an important role. He perhaps meant it to denote ‘the central point or the essence’.

His religious vision is explained through the symbol of heart, at three levels – the ultimate reality, the method and the experience. The first; the Heart, that is, the ultimate nature (anuttara – there is nothing beyond) of all reality, is Shiva. The second is the methods and techniques employed (Sambhavopaya) to realize that ultimate reality. And, the third is to bring that ideal into ones experience. The Heart here refers, in his words ‘to an experience that moves the heart (hrudaya-angami-bhuta). He calls the third, the state of realization as Bhairavatva, the state of the Bhairava.

He explains through the symbolism of Heart to denote the ecstatic light of consciousness as ‘Bhaira-agni-viliptam’, engulfed by the light of Bhairava that blazes and flames continuously. Sometimes, he uses the term ‘nigalita’ melted or dissolved in the purifying fire-pit the yajna–vedi of Bhairava. He presents the essential nurture (svabhava) of Bhairava as the self-illuminating (svaprakasha) light of consciousness (Prakasha). And, Bhairava is the core phenomenon (Heart – Hrudaya) and the ultimate goal of all spiritual Sadhanas.

When we use the term ‘understanding’, we also need to keep in view the sense in which Abhinavagupta used the term. He makes a distinction between the understanding that is purely intellectual and the one that is truly experienced. The latter is the Heart of one’s Sadhana.

The Heart of Abhinavagupta is that a spiritual vision is not merely intellectual, emotional or imagined. But, it is an experience that is at once pulsating, powerful and transforming our very existence.

– The Triadic Heart of Siva by Paul Eduardo Muller-Ortega]

In the next part let’s see the explanations and the discussions provided by Bhartrhari on the various levels of the language (Vac).

Continued

In the

Next Part

Sources and References

- Abhinavagupta and the word: some thoughts By Raffaele Torella

- Sanskrit terms for Language and Speech

- http://www.universityofhumanunity.org/biblios/Terms%20of%20Word%20and%20Language.pdf

- The Four levels of Speech in Tantra

- Bettina Baeumer -Second Lecture – Some Fundamental Conceptions of Tantra http://www.utpaladeva.in/fileadmin/bettina.baeumer/docs/Bir_2011/Second_Lecture.pdf

- Sphota theory of Bhartrhari

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/31822/8/08_chapter%202.pdf

- The Philosophy of the Grammarians, Volume 5 edited by Harold G. Coward, K. Kunjunni Raja, Karl H Potter

- Culture and Consciousness: Literature Regained by William S. Haney

ALL PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET