Dance forms of India

Uparupakas

Bharata, in his Natyashastra, discussed, in main, the Rupakas, the major forms of the Drama; and, the two genre of Dance formats – Tandava and Sukumara. His concern seemed to be, primarily, with the forms and styles that were dominant in the art-tradition of his time; and, particularly those that had the potential to display various modes of representations and to evoke Rasas. For him, the aspect of Rasa was central to the Drama.

Of the eleven essential elements of the Drama that he names, Rasa is of paramount importance; and deriving that Rasa is the objective of a theatrical performance. The other ten elements – from Bhava to Ranga – are the contributing factors for the production of the Rasa

rasā bhāvā hy abhinayāḥ dharmī vṛtti pravṛttayaḥ / siddhiḥ svarā astathātodyaṃ gānaṃ raṅgaś ca saṅgrahaḥ // BhN_6.10 //

Bharata, similarly, even in regard to Dance, described only those dance forms that he considered to be artistically well cultivated; leaving out the regional and popular varieties. In the process, Bharata did not deal with the many peripheral styles.

The Drama, a Drshya-Kavya, was formally known as Rupaka. Abhinavagupta explains Rupam as that which is seen; and, therefore, the works containing such matter is Rupani or Rupaka-s. And, Dhananjaya in his Dasa-rupaka (ten forms of Drama) explains : it is called a Rupaka or a representation, because of the acts put on by the actors (abhinaya) by assuming (rupakam tat samaropad) the forms of various characters such as gods or kings and men and women. And, it is called a show, because of the fact it is seen (rupam drsyatayocyate).

Thus, Drama is the reproduction of a situation (Avastha-anikrtir natyam), in a visible form (rupa), in the person of the actors. Dhanika , in his commentary , explains that the terms Natyam, Rupam and Rupakam can be treated as synonymous.

The Drama was classified into two types : Major (Rupaka) and Minor (Upa-Rupaka).

Under the Rupakas (major types of Drama) , Bharata mentioned ten of its forms (Dasadhaiva). Of the ten, he discussed, in fair detail, only two forms –Nataka and Prakarana. Because, he considered that these two alone fulfilled all those requirements that were necessary for a Rupaka (major type). According to Bharata, these two major forms alone depict varieties of situations, made up of all the four modes or styles (Vrttis) and representations. And, they alone could lend enough scope for display of Rasas (Rasapradhana or Rasabhinaya or vakya-artha-abhinaya). In contrast, the other eight forms of Rupakas deal with limited themes and rather narrow subjects; and, are also incapable of presenting a spectrum of Rasas.

In the process, Bharata did not also discuss about the minor forms of the drama, the Uparupakas or Natyabhedas. These were a minor class of dramatic works, distinct from the major works; and, did not satisfy all the classic, dramatic requirements prescribed for a Rupaka or Nataka proper. Such minor class of plays (Uparupakas) handled only a segment of a theme or story (Vastu); and, not its full extent. It did not also, perhaps, employ all the four Abhinayas, in their entirety.

*

By the time of Abhinavagupta (Ca.11th century), the Dance had diversified into many more forms than were known during the time of Bharata. However, he mentions that even those innovative forms, indeed, continued to be rooted in the basic concepts laid down in the Natyashastra. And, in fact, he often cites idioms of dancing from such new categories, in order to illustrate Bharata’s concepts.

For instance; Abhinavagupta explains the nature of the delicate Sukumara Prayoga and of the gentle Kaisiki Vrtti, with reference to examples taken from Nrtta-kavya or Nrtya-prabandhas or Ragakavyas – musical compositions or narrative plays (classified under Uparupakas) beautified with the elements of dance and music; and, which could be presented through expressive Abhinaya.

Abhinavagupta remarks; though the concept of minor dramas is absent in the Natyashastra, it is those minor classes of plays – Uparupakas, par excellence – in their varied forms, adorned with rich, melodious music, as also with graceful and delicate dance movements, which grew into becoming the main stay of the contemporary dance- scene.

Thus, Abhinavagupta, in his commentary, did mention the Upa-rupakas; but, he did neither define its essentials nor did he explain its features. He merely called them as Nrtta-kavya and Raga-kavya; meaning, the type of plays that are rendered through song, dance and interpreted through Abhinaya. In that context, Abhinavagupta mentions some plays of Uparupaka variety. He names them as: Dombika, Bhana, Prasthana, Sidgaka, Bhinika, Ramakrida, Hallisaka, Sattaka and Rasaka. These minor dramatic works were of the nature of dance-drama, where the elements of music and dance were dominant. But, Abhinavagupta had not discussed about those musical varieties.

[Though the Natyashastra had not specified the varieties of Uparupakas, in the later times their numbers varied according to the whim of each author. For instance; Abhinavagupta refers to nine types of Uparupakas; Dhanika mentions seven types as being Natya-bheda (varieties of dance forms) ; Sahityadarpana mentions eighteen types; Natyadarpana recognizes only thirteen of these eighteen types, because they were said to be the only ones that were mentioned by the Vruddhas (the elders) or Chirantanas (ancient ones) ; Raja Bhoja refers to twelve types; but, the largest number seems to have been listed in Bhavaprakasana , which mentions as many as twenty Uparupakas , including Natika, Prakaranika, Sattaka, Trotaka etc., which are almost as good as the Nataka .

The fact that there was no unanimity among various authors either in the numbers or in the definition of the Uparupakas, merely suggests that this from of Rupaka was evolving all the time; improving; and, continuously undergoing changes and modifications in their nature and form, aiming to attain a near-perfect musical dance format.

It is explained the prefix ‘Upa’ should not be taken to mean ‘minor’ ; but, it should be understood as referring to the types that are ‘very near’ to the Rupakas, but, having a preponderance of dance and music.]

Perhaps, the earliest reference to Uparupaka occurs in the Kama-sutras of Vatsyayana (earlier to second century BCE), which presents a guide to a virtuous and gracious living. Here, Vatsyayana mentions Uparupaka type of plays, such as Hallisaka, Natyarasaka and Preksanaka, which were watched by men and women of taste.

Rajashekara (8th-9th century) calls his Prakrit play Karpuramanjari, as a Sattaka type of Uparupaka. He explains that the play in question was not a Nataka, but resembled a Natika (a minor form of Drama). It was a single-Act play (ekankika or Javanika); and, it did not contain the usual theatrical scenes such as: the pravesakas (entry-scenes) and viskambhakas (intermediary or connecting scenes). Here, in the Sattaka type of Uparupaka, music and dance were the principal mediums of expression. It is composed in the graceful Kaisiki Vrtti; and, has an abundance of Adbhuta Rasa (wonder and amazement). Even a major part of its spoken dialogues (Vachika) was rendered in musical form. And, the story of the play was composed by stringing together series narrative songs.

Bharata had also mentioned that in a well rendered play, the song, dance, action and. word follow one another in an unbroken flow; presenting a seamless spectacle as if there is neither an end nor a beginning , just as wheel of fire (Alata chakra).

evaṃ gānaṃ ca vādyaṃ ca nāṭyaṃ ca vividhā aśrayam / alāta-cakra pratimaṃ kartavyaṃ nāṭyayoktṛbhiḥ // BhN_28.7 //

That, in a way, sums up the characteristic nature of the dance-drama type of Uparupakas. Here, the stylized Natya-dharmi mode of depiction is dominant. And, even when Vachikabinaya is used, the emphasis is more on the Abhinaya rendered through gestures to the accompaniment of song and music; than on speech.

Such Uparupakas, while narrating an episode or a story, did use the elements of the Nrtta (abstract dance movements) along with the Abhinaya of the Nrtya. They were, thus, a specific form of Natya– (Natyabheda) . They also provided ample scope for display of Bhavas and for evoking Rasa.

[ As Dr. Sunil Kothari observes in his research paper :

The technical distinction which Natyashastra makes between Rupakas and Uparupakas is that while the former presents a full profile of a Rasa with other Rasas as its accessories. Further, in the Rupaka a full story was presented through all the dramatic requirements and resources fully employed. But in the Uparupaka only a fragment was depicted. And, even when a full theme was handled all the complements of the stage were not present; the Uparupaka lacked one or the other or more of the four Abhinayas; thus, minimizing the scope for naturalistic features Lokadharmi and resorting increasingly to the resources of Natyadharmi.

Whereas this is true of several other forms of Uparupakas, it is not true of the dance-drama forms. They used all the elements of the Abhinayas; and,also provided scope for display of Bhavas and for evoking Rasa.]

Coming together of the Marga and Desi traditions

By about the twelfth century, the classic Sanskrit Drama, in its major format, the Nataka, began to gradually decline. And, over a period, it almost faded away.

Though the Sanskrit theatrical tradition was tapering out, it did continue in the forms of minor or one-act plays – Uparupakas – mainly in regional languages, with a major input of dance and songs; but, with just an adequate stress on Abhinaya (acting) and Sahitya (script). These forms of dance-dramas were gaining ground.

The texts of the later period commenting on Natya and Alankara-shastra (poetics) could hardly afford to ignore the Uparupakas which were steadily gaining popularity. And, many scholars did formally recognize the Uparupaka class of dramatic works; codified their features; and assigned them a place within the framework of theory , as Nrtya-prabandhas.

By about the twelfth century, the differences as also the relationship between the Nrtta (pure dance) and Nrtya (Nrtta with Abhinaya) were clearly established. And, those dance formats, in combination with music, were suitably applied and integrated into the performance of the dance dramas.

Among the authors of the later period, Raja Bhoja ((10-11th century), Saradatanaya (12-13th century) and Vishvanatha (14-15th century) dealt at length with the Uparupakas. Raja Bhoja in his Srngaraprakasa discusses twelve types of Uparupakas; Saradatanaya in his Bhavaprakasa describes twenty-one forms of Uparupakas and also provides a gist of several definitions as given by the previous authorities ; and, Vishvanatha in his Sahityadarpana discusses in detail eighteen types of Uparupakas, with examples

For a detailed discussion on the types of Uparupakas: please click here. And, go to pages 189 and onward for descriptions of those forms.

Such staged dramatic texts (Nrtta-kavya or Raga-kavya), narrating a story, composed of songs, set to music with instrumental accompaniment; and, choreographed with dance movements, came to be known by different names such as: Natyabheda (in Avaloka of Dhanika); Geyarupaka (in Kavyanusasana of Hemacandra): Nrtyarupakas or, simply as the ‘other plays’ anyani rupakani (as by Ramacandra and Gunacandra), in which music and dance dominate.

The period between the eleventh and the fifteenth centuries was a very highly significant phase in the evolution and development of Art in its varied dimensions. It was during this period that Dance, as Nrtya, gained recognition as an independent Art-form. And, Dance was no longer treated as a mere adjunct to drama. Similarly, vocal (Gita) and instrumental (Vadya) also began to flourish on their own.

The Dancing in India evolved by assimilating new forms and techniques; and, by moving away from its early dependence on Drama. In the process, it also widened its aesthetic scope beyond decorative grace; and, enlarged its content or repertoire to encompass depiction of emotional narrative themes. Now, the beauty of form walked hand-in-hand with the richness of the lyrics and, with the depth of its emotional content; resulting in the growth of a complex art form.

During the period , which spans the eleventh to the sixteenth century, many excellent works on Dance and music were written; and, new trends in Dancing were set. Now, many texts, exclusively devoted to Dance came into being (Say, Sangitaratnakara of Sarangadeva – Chapter seven; the Nrtya-ratna-kosa of Maharana Kumbha ; the Nrttaratnavali of Jaya Senapati; Nartananirnaya of Pundarika Vittala).

The texts of this period , though rooted in the principles of Natyashastra, did recognize and discuss Dance-forms and styles whose technique and structure differed from the Marga class described by Bharata- During this period, the emphasis of the texts shifted away from Natyashastra’s Marga tradition ; and, moved towards the styles known , generically, as Desi , regional or improvised.

It was during this period that Uparupakas developed into a common ground where the classical Natya of the Shastra (Marga) met the regional (Desi) forms of Dance of easy movements; allowing more freedom and greater degree of improvisation, within the given framework. It was here that the sophisticated fused with the folk forms.

The noted scholar Dr. Raghavan, therefore, described the Uparupaka as the golden link (svarna-setu) or common ground where the classical met the popular; and, where the sophisticated took the folk forms. It was also here that the folk forms sublimated into classical form.

This period was also marked by the efforts to codify the less acknowledged, but popular forms; and, assign them a place within the framework of theory.

In the process, the theories of Dance adopted the terms and principles that were prevalent in the Kavya, poetics. Those dance forms which adhered to the established regulations and conventions; and, which had a definite structure were termed and classified as Nibaddha. And, those free-flowing dance forms, which were spontaneous, unregulated, unstructured and not bound by any rules, were treated as Anibaddha. Such unfettered dance-forms were not restricted by the requirements of Taala and such other disciplines; and, it did not also need the support of compositions woven with meaningful words (Pada or Sahitya). Sarangadeva defines Anibaddha as that which is not bound or as that which lacks rules (bandha-hinatva).

The Anibaddha also meant allowing the dancer considerable latitude in devising body movements that best suited the aesthetic and emotional content of the theme.; And , it also made room for enterprise to come up with fresh idioms of expressions.

At the same time, the texts, such as the Sangita-samayasara, the Sangitaratnakara and the Nartananirnaya, suggested body movements as that of simulating the quiver of a drop of water on a lotus leaf, or the trembling of a flame etc.

Such process of reorganization and innovation covered not only the well regulated dance forms ; but, it also extended even to the individual and the group dances like Daṇḍaras, Raslīlā and other folk dances of similar nature, some of which have survived as dramatic group presentations.

Dr. Mandakranta Bose in her ‘Movement and Mimesis’ concludes : Our study of technique also shows that present day classical dancing in India is grounded more directly in the tradition recorded in the later dance manuals, especially the Nartananirnaya , than in the older tradition of the Natyashastra. This suggests that those styles which had marginal existence in Bharata’s time not only came to be admitted into the mainstream of dancing, but eventually became the dominant current. The evolutionary process is therefore one of dynamic growth rather than a static survival. Through the comparative analysis of the concepts and technique of dancing the present study attempts to mark the milestones of that process

As Dr. Sunil Kothari also observes in Part One of his research Paper : the minor forms that were not specifically described by Bharata came into fore during the later periods. And, they have contributed greatly in the evolution of the dance concepts; and, in shaping and enriching the various dance forms, in their distinct regional milieu; as we see in contemporary India.

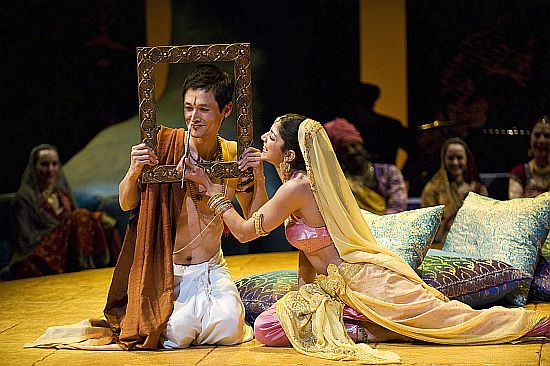

Dance-dramas

Dance and music have always formed an integral part of Sanskrit drama. But, it was the Uparupakas – minor class of drama- based in music and dance movements that eventually gave rise to the now living traditions such as Kuchipudi, Bhagavata-Mela-Natakas, Yaksha-gana and Kuravanji dance dramas. Such forms of Uparupakas are very attractive formats, with the elements of the music and dance being predominant. And, most of them are based in dances accompanied by soulful songs, interpreting the emotional contents of the song through Abhinaya or gestures.

The Uparupakas also marked the emergence of dance-drama along with the solo exposition as a credible format of Dancing. Since then, dance-drama has come to stay and flourish side by side with the solo dance forms.

*

The key element of the musical dramas was delighting in the spectacle of presentation and the emotions displayed by the characters on display. Their themes were crafted around Raga and Kavya elements, which dealt with the characters, themes, plots, emotional situations rooted mainly in Srngara (lovely and graceful) and Bhakthi (devotion) Rasas. The Uparupakas were, therefore, said to be Bhavatmaka or dependent on emotions.

The Uparupakas were broadly classified according to the dance-situations that were involved and the Rasas, the emotions, they projected. Among the Uparupakas, the Rasaka, Hallisaka, Narttanaka, Chalika and Samyalasya gave importance to Nrtta, the pure dance movements, in their performance. And, Natika, Sattaka, Prakaranika and Trotaka (Totaka) gave prominence to emotional aspects and to Abhinaya.

Gita-Govinda

The most celebrated of the Raga-kavyas, Chitra-kavyas or Nrtya-prabandhas is the Gita-Govinda composed by Sri Jayadeva Goswami (about 1150 A.D), who was a court poet of the King Lakshmana of the Bengal region (12th century). It is the most renowned and the best loved among all the Raga-kavyas of the Prabandha class. Gita-Govinda occupies a preeminent position in the history of both the Indian music and dance.

The Gita-Govinda is a Khanda-Kavya, confined to description of some episodes. It comes under the Prabandha class of Kavyas. Jayadeva at the commencement of his Khanda-kavya states that he is composing a Prabandha Kavya (Etam karoti Jayadeva kavih prabandham). The Ashtapadi (eight footed) is a Dvi-dhatu Prabandha, i.e. consisting two sections (Dhatu): Udgraha and Dhruva.

This sublime Sringara-mahakavya, lovingly describes the emotive sports of Sri Radha, the Mahabhava – highly idealized personification Love and Beauty; and, Krishna the eternal lover (Sri Radha-Krishna-Lila).

Gita Govinda is the most enchanting collection of twelve chapters (Sarga). And, each Sarga commences with soulful a Sloka followed by one or two songs arranged in couplets. These songs are known as Giti, Prabandha or Ashtapadi, since twenty-four of such (but not all) employ eight couplets. Sri Jayadeva himself calls them as sweet and delicate Padavali-s (Madhura komala padavalim).

The Gita Govinda, permeated with intensely devotional and delicate Madhura Bhakthi, was one of the inspirations of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprbhu who was steeped in Krishna-bhakthi; and, it is now the primary text of the Gaudiya Vaishnava School of Bengal.

The popularity enjoyed by Gita Govinda is amazing. Each region and each language of India embraced it to its heart, with love and devotion; adopted it as its own; sang in its own chosen Raga; and, interpreted it in its own dance form.

The Gita Govinda also served as an inspiration or as a model for creation of dance-dramas, elaborating on parallel themes, in different parts of the country, in different languages. For instance; the dance sequences composed in the traditions of Kuchipudi of Andhra; the compositions of Sri Sankaradeva of Assam; Umapati of Bihar; Bhagavata Mela Natakas of the South; Yaksaganas of Karnataka ; and, Krsnattam and Kathakali of the Malayalam areas – were all inspired by the Gita-Govinda.

Nauka Charitam

And, Sri Thyagaraja (1767- 1847) is said to have composed three musical dramas (Geya-Nataka). Of these, only two namely: Prahlada-Bhakti-Vijayam and Nauka Charitam are available. But, the third – Sita Rama Vijayam – is sadly lost.

Nauka Charitam, mostly a product of Sri Thyagaraja’s imagination, improvising on an incident briefly mentioned in Srimad Bhagavatam, comprises twenty-one Daru songs set in thirteen Ragas (some of which follow folk tunes) . Its theme extols the virtue of absolute surrender to the Lord with Love and devotion. Nauka Charitam lends itself beautifully well for production of a Dance-drama.

Regional Dance forms

By about the sixteenth century, the Nrtya-prabandhas, set free from the confines of the Drama, began to flourish and to evolve further, by assimilating new forms, more creative modes of expression and techniques. In the process, their aesthetic scope grew beyond mere decorative postures. They refined their skills to communicate the emotive content of the lyrics, more effectively. Beauty of form was blended with meaningful expressions (Abhinaya). The Uparupakas having developed into a complex Dance-form came to occupy a central position within the contemporary world of Art.

Even in this format, the dance element continued to be divided into Nrtta and Natya on the one hand; and, into Tandava and Lasya on the other. Another significant factor was that even though the Dance was mainly based in the theoretical principles of the Natyashastra; yet, in practice, it inculcated styles and techniques that were peculiar to each region. In each of those regions, the Dance practitioners also developed their own local vocabulary. These gave rise to distinctive dance forms and technical terms.

Each of such derivative forms formulated a tradition of its own; such as Kathak, Odissi, Manipuri, and Kuchipudi and so on. And, each of those eminent dance forms rooted in its own regional and cultural background; anchored in its own philosophy and outlook, developed its own idioms of expressions.

There are also certain factors that are common to all those diverse types of dance forms. These, in brief, are :

:- the prominence accorded to the narration of the theme;

:- the dominance of Natya-dharmi;

:- performing to the appropriate music, Laya (tempo) and Taala (time-units, beats) ;

:- employment of all the four Abhinayas in varying degrees, in an appropriate manner ;

:- in making a distinction between the Nrtta and the Nrtya, and maintaining their distinctive features while executing the respective elements in the performance;

:- taking care to see that the Nrtta aspect, particularly the individual dance movements and postures, are governed by the special techniques developed by each school of Dance; and,

:- recognition of both the Ekaharya (solo – where a single dancer enacts the role of several characters) and Anekaharya (where several actors participate to enact their respective role) modes of presentation.

Yet, these Dance-forms have successfully retained their identity; and, have carried it forward to the present time.

Kathak

As regards Kathak, its history as a performing art has to be viewed in the larger context of the history of the Dance forms of the North India. Kathak, in its earlier form had a long association with temple-dance. But, with the advent of Mughal rule; and with the influence it exerted on Indian life and culture, Kathak dance was remodeled into a different form.

For instance; it is said, by the time of Akbar (16th century), the Persian art and music had vastly influenced the cultural life of India, particularly the milieu surrounding the Mughal court. According to Pundarika Vitthala (Nartana-nirnaya), who had the opportunity to watch, appreciate and enjoy excellent presentations of the Persian oriented dance and music, the restructured Dance form of Kathak, was born out of the fusion of classical Natya with the dance of the Yavanas, (meaning, the Persians), which took place in the context of the cultural life of the Mughal inner court, during the time of Akbar.

Kathak, in its early period, had not only a special, unique manner of dancing, with its own phrases of Nrtta and Abhinaya; but it also had its own distinct structure of performance and philosophy. But, During the Mughal period, it became a source of recreation for those seeking escape from the day-to-day annoyances. Its purpose, then, was to provide sheer pleasure, entertainment and amusement. Thus with the advent of the Mughal rule there was a definite shift in its content as also in its emphasis. And, the elements of devotion, worship etc., that were there in its traditional form went into background. It acquired the epithet of Nautch.

Thereafter, with the fall of the Mughals, Kathak, somehow, managed to survive by shaping itself into a fine expression of a dance form aiming to please its newly acquired patrons, the rulers of small native states. It then branched into Gharanas named after the court that supported it ; like Lucknow Gharana , Jaipur Gharana, Rampur Gharana etc. (For more, please do refer to Kathak, Indian Classical Dance Art by Sunil Kothari )

*

Kathak , which follows Nartanasarvasva , has a unique feature of taal-prastuti (a systematic elaboration of a time-cycle of a chosen number of beats) that is not found in any other classical Indian dance-forms. It has also a distinct way of presenting the syllables and Bols used in the text of the songs. The variations of these Dance-forms are also recognized by their nature, even in case their style is classical, folk, or modern.

And since the post-Independence days, happily, the classical Kathak is rediscovering itself. It is liberated from the confines of the past feudalistic court associations. The framework and outlook of the present-day classical Kathak is chaste – aesthetically and spiritually.

**

Katarzyna Skiba (Jagiellonian University, Kraków) in her paper: Cultural Geography of Kathak Dance, writes, among other things:

Kathak is commonly described as elegant, graceful, rhythmical and relatively naturalistic dance, associated with Vaishnavism, but also impacted by Mughal Court. The two leading Kathak Gharānās seem to represent the modalities of the showcased national features: Rajput’s’ valor and Mughal’s finesse.

Artists and critics tend to talk about Nazākat (Ur. “delicacy”) and khūbsūratī (Ur. “beauty”) as essential characteristic of Kathak, emerging from Lakhnavi culture and Mughal court etiquette.

Jaipur style is considered as more vigorous, fast and focused on technical excellence: its exponents are praised for their speed, agility, or ability to render a series of multiple fast turns (Chakkars). Mythological stories are provided mainly through the medium of Kavitts and Tukṛās—short compositions consisting of semi-abstract, rhythmical melo-recitation.

Here, Kathak is primarily associated with the Braj region; hence the traditional repertoire is dominated by Krishna-Lila themes (set in Braj-Bhoomi); and, often illustrated through the songs, or melo-recitations in Braj-bhāṣā

In comparison, Lucknow masters pay more attention to the depiction of feelings (bhāv) through gestures and mime. The dance is often slower, subtle, sensual, limited in demonstration of footwork and focused on presenting a story. The dancers primarily elaborate lyrical compositions (Thumris and Gazals), improvising on their content and filling their performance with emotional depth

*

As Kathak expands on global stages and in schools, its exposure causes the influx of Western ideas and practices into the tradition, that together with performers overflow into the Indian market. Therefore, the young generation of Kathak dancers transgress the borders of tradition in various ways and redefine its parameters, in an attempt to find their own place in the increasingly transcultural community of dance professionals

The author considers the impact of regional culture, economic conditions as important factors in reshaping Kathak art and influencing practice and systems of knowledge transmission. ]

***

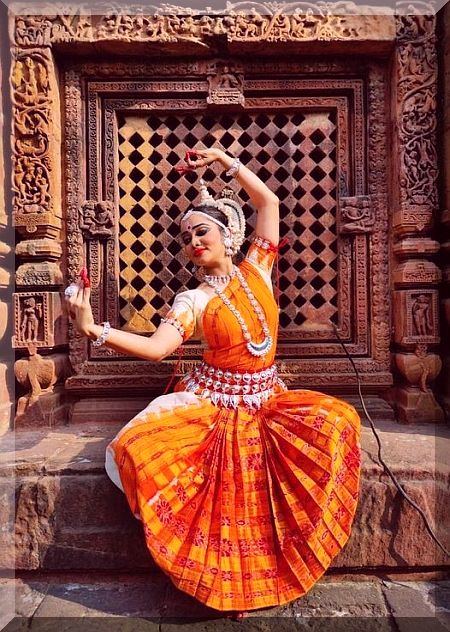

Odissi

In contrast; the classic Odissi was, essentially, a temple-dance, enacting a devotional poem. It is steeped in devotion; and, in the concepts of spirituality of the Vaishnava tradition. It is performed as a way of submitting ones service (seva) to Lord Jagannath. Odissi is a lyrical form of dance with subtlety as its keynote. It is known for its fluidity and grace. Its sculpture-like poses are executed with harmony of line and movement. Odissi has developed its own vocabulary of foot positions, head movements, eye movements, body positions, hand gestures, rhythmic footwork, turns and spins.

Odissi, again, is based in the principles of the Natyashastra. It also follows other texts such as Abhinaya Chandrika of Mahesvara Mahapatra and Abhinaya Darpana of Nandlkesvara. Dr. Mandakranta Bose opines that the techniques of Odissi are also derived from the Nartananirnaya of Pundarika Vittala.

The Odissi also observes the traditional formats of Nrtta, Nrtya and Natya, in their distinct forms.

The initial items, following soon after the invocation , the Mangalacharana, and Pushpanjali, are in the fast-paced, rhythmic pure dance movements of Nrtta class, known as Battu or Battu Nrtta. That is followed by Pallavi rendering in varied tempos.

The Nrtya segment of the Odissi is more elaborate. It consists narration of a theme; the interpretation of the words and sentences of the lyrics of the song; illustrating with grace Abhinaya articulated through elegant Bhavas, gestures and facial and eye expressions. Odissi is renowned for fluid, eloquent and gracefully charming movements and postures. The songs of Nrtya are, generally, in adoration of Vishnu, as Lord Jagannath. Apart from that, the Astapadis selected from Jayadeva Kavi’s Gita Govinda are the most popular numbers in it’s Nrtya repertoire. These soulful dance recitals celebrate the divine Love of Sri Radha and the eternal Lover Sri Krishna.

The Natya segment of a Odissi performance relates narration of a theme selected from the mythology, epic or a celebrated Kavya.

Kuchipudi

Similarly, Kuchipudi, the dance-drama of the coastal Andhra Pradesh, is regarded as a religious art of the Vaishnava tradition, devoted to Lord Krishna (Bhama kalapam), where the dancer-actor narrates a story, conveying a spiritual message through expressive gestures, graceful body-movements and rhythmic footwork. In fact, a Kuchipudi performance commences with the recitation of the auspicious slokas extracted from Vedic texts; consecration of the stage with sprinkling of holy water (punyavachana); and , offering Puja to the Ranga Adidevata , the chief deity on the stage. That is followed by dance-offering to Ganapathi; prayers submitted to Goddess Tripurasundari, and to the Guru; and Naandi-stotra by the Sutradhara, the stage manager. The Kuchipudi Natyam is usually performed by a group or in some cases by a solo dancer who enacts, through dance movements, the roles of several characters. The performance concludes with Mangalam, the benedictory verses; and, offering Aarati to gods.

The repertoire of Kuchipudi also follows three performance categories of dance forms; namely, Nrtta (Nrutham), Nrtya (Nruthiyam) and Natya (Natyam). Here, ‘Nrtta’ is a technical performance where the dancer presents pure dance movements with stress on speed, form, pattern, range and rhythmic aspects without interpretive aspects. In ‘Nrtya’ the dancer-actor communicates a story, spiritual themes particularly on Lord Krishna through expressive gestures and slower body movements harmonized with musical notes thus engrossing the audience with the emotions and themes of the act. ‘Natyam’ is usually performed by a group or in some cases by a solo dancer who maintains certain body movements for specific characters of the play which is communicated through dance-acting.

(For more, please check Indian Classical Dances : Kuchipudi Dance)

Manipuri

Manipuri , of Eastern India, is a classical dance form narrating themes rooted in the Vaishnava Bhakthi tradition, depicting the Love between Sri Radha and Lord Krishna , mainly through the re-enactment of the sublime ‘Raas Lila’. It is also fused with the pre-Vaishnava tradition of Lai Haraoba and Thang-ta, which add variety and vibrancy to its repertoire of movements. Here, again, dance and music are interwoven with rituals and religious practices.

It is said; the repertoire and basic play of this dance form revolves around different seasons. The traditional style of this art form incorporates graceful, gentle and lyrical movements. The fundamental dance movement of Raas dances of Manipur is Chari or Chali.

Manipuri dances are performed thrice in autumn from August to November; and, once in spring sometime around March-April, all on full moon nights. While Vasanta Raas is scheduled in spring when Holi, the festival of colours is celebrated, the other dances are scheduled around post-harvest festivals like Diwali.

The themes of the songs and plays comprise of Love and association of Radha and Krishna in company of the Gopis namely, Sudevi, Rangadevi, Lalita, Indurekha, Tungavidya, Vishakha, Champaklata and Chitra. One composition and dance sequence is dedicated for each of the Gopis; while the longest sequence is devoted to Radha and Krishna.

The dance drama is performed through excellent display of expressions, hand gestures and body language. Acrobatic and vigorous dance movements are also displayed by Manipuri dancers in certain plays.

Mohiniattam

The Mohiniattam, a classical dance form that evolved in Kerala, is said to have been derived from the dance performed by Mohini, a female Avatar of Vishnu. It, again, is a temple-dance; but, with a predominance of graceful and gentle Lasya movements. The Mohiniattam dancers follow- among other manuals – the Balarama -bharatam as their guidebook.

Mohiniattam also comprises all the three elements of Nrtta (pure dance movements); Nrtya (narrating a theme with Abhinaya); and, Natya (enacting a play, usually by a group).

A performance of a Mohiniattam includes sequences commencing with invocation or Cholkettu; and then on to Jatisvaram, Varnam, Padam, Tillana, Shlokam and Saptam. Thus, Mohiniattam is aligned to what came to be known as Bharatanatya.

Its songs are composed with mixture (Manipravala) of Sanskrit and Malayalam words.

Traditionally, Mohiniattam is performed by a single dancer who enacts the roles of the other characters that feature in the lyrics of the song (Ekaharya Abhinaya). Of late, Mohiniattam is also performed as group dance.

Dance forms

All these dance-forms, including Kathak, though they are basically individual performances, they are also enacted as group dances.

What is common to all these classical dances is that their roots are in religion, mythology and devotional stories. Central to these dances is the Nayika, the gentle heroine, who symbolizes the soul of the devotee. The spirit of Bhakthi permeates these dance forms. And, their traditions have been carried forward under the Guru-shishya –parampara, with each generation passing on to the next, with earnestness, the knowledge, skill and the philosophy of its School.

*

The Dance forms, such as, Kathak, Odissi or Kuchipudi narrate a story or an episode chosen from an Epic or mythology. Etymologically, the term Kathak is related to Katha, the art of storytelling. The Western ballet also tells a story. But there are some significant differences between these Dance forms, with regard to their nature and the manners in which they are danced. For example; classical Ballet is performed as a group dance , where different dancers play different roles or characters to build a story. This story is performed as a dance-drama, where various scenes unfold one after the other.

And, another is that unlike in the western dance, the Indian Dances are not set to leaps and gliding movements in the air. It strives to achieve a perfect pose that can be frozen in time. Its technique depends on the skillful management of time (Taala), in order to achieve a series of perfect poses.

In contrast to ballet; the Kathak and other classical dance forms are, traditionally, solo dance-performances. Its dancer enacts all the roles or characters involved in the story (Ekaharya). Here, the story is presented mainly with the help of Abhinaya that involves facial expressions and meaningful hand-gestures. Apart from telling a story, the dancer will have to meticulously follow the rhythmic patterns (Taal) as required by the lyrics and also the sol-fa and other dance syllables rendered in varying speeds (Laya).

Similarly, the Varnams and Padams in the Bharata Natyam are, usually, presented as solo performances. While presenting the theme of the song that is to be interpreted, the dancer skillfully assumes (Natyadharmi) the role of several characters (ekaharya) that figure in the lyrics, with appropriate Sancari- bhavas; say, the roles of the Nayika (heroine), her friend/assistant (Sakhi) or of the Nayaka (hero)’. This is achieved through a series of variations of Angikabhinaya, in which each word of the poetry is interpreted in as many different innovative ways as possible.

*

Another significant point is that the present-day dance forms like Kathak, Odissi etc., are more related to medieval texts like Nartananirnaya than to the ancient manuals. This, in another way, could be taken to mean that certain dance-forms, which were marginalized in the Natyashastra, found a new life and due recognition as one among classical Dances of India. This again emphasizes the dynamic nature of Art, which rejuvenates and re-invents itself all the time.

*

Influence of Nartana-nirnaya

Now, as regards the historical significance of Nartana-nirnaya; many scholars, after a deep study of the text, have observed that there is enough evidence to conclude that the text marks the origin of two major styles of India today, namely, Kathak and Odissi. Dr. Mandakranta Bose, the much respected scholar and authority on the principles and practices of the performing arts of India, also concurs that such connection seems highly plausible. The text was part of the same cultural world of the Mughal court that nurtured Kathak.

Dr. Bose, in her work, Movement and Mimesis: the Idea of Dance in the Sanskritic Tradition , points out that several technical terms used in Nartana-nirnaya match those used in Kathak today. And she goes on to say:

When we look closely at the technique of the dance described under the Anibandha category, we begin to see certain striking similarities with the technique of Kathak. One cannot say that the style described in the Nartana-nirnaya matches Kathak in every detail. But one may certainly view that style as the precursor to Kathak; but the descriptions and the similarities in their techniques clearly show it to be the same as what we know today as Kathak.

The Nartana-nirnaya seems, thus, to be the proper textual source for Kathak. This claim becomes stronger still on examining points of technique.

*

As regards Odissi, Dr. Bose observes :

The Bandha-nrtta as practiced in the Odissi style is very similar to the descriptions given in the Nartana-nirnaya.And, the basic standing postures prescribed in the Odissi style: Chauka and Tribhangi are the two main basic stances in Odissi. Chauka is a stable-wide stance, with weight of the body distributed equally on both the sides; and, the heels facing the centre. It is said to be a masculine posture. Tribanghi, is a graceful feminine posture, with the body bent in three-ways). These are comparable to vaisakha-sthana and Agra-tala-sanchara-pada of the Nartana-nirnaya. Further, some acrobatic postures still in use are: danda-paksam, lalata-tilakam and nisumbhitam (the foot raised up to the level of forehead), and several others are found both in Odissi and in Chau dance of Mayurbhanj region of Orissa. Further, there is in the Nartana-nirnaya, the description of a dance called Batu involving difficult poses; and it is very similar to the Batunrtta, a particularly difficult dance in the repertory of Odissi.

Bharatanatya

The School of Nrtya that is prevalent in South India is Bharata-natya. It has gained ground through the efforts of some dedicated stalwarts.

During the period of national movement for attaining India’s independence, there was a revival and resurgence of Dance forms; and re-assertion of its values.

With the advent of the Maestro Uday Shankar; and with the efforts of the aesthetes like Rabindranath Tagore, Poet Vallathol of Kerala ; as also Rukmini Devi and E. Krishna lyer of Kalakshetra at Adyar, the ancient form of dance (Marga), as in Bharata’s Natyashastra, was re-established, by renaming it as Bharata-Natyam.

Along with that, the other classical dance forms like, Kathak, Odissi, Mohiniattam and Manipuri were also revived.

Dance – Today and Tomorrow

Till about the 18th Century, the temple; its architecture; and, the Dance were closely related. Up till that period, the association between architecture and dance culture was quite explicit. But, during the present-day, particularly in the modern temple architecture, the link between temple-layout and Dance has virtually snapped. The temples designed and constructed during the recent times hardly provide for a Ranga-mantapa; perhaps because , it is deemed either needless or out-of-place.

Unfortunately, this resulted in a break in the continuity and, in the evolution of dance and its requisite architecture.

Now, the Classical Dance-forms, including Bharatanatyam, have since transformed into symbols of Art-Culture; and, are no longer meaningfully associated with either the temple or its architecture. In this aspect, the tradition and modernity have drifted apart.

Moving from temple to theater was a huge, a gigantic leap. During the last seventy-five years there have been tremendous changes in the arena of Dance, in terms of structure, content, theme, presentation techniques, teaching methods and so on. As it stepped into the open society and reached out to larger numbers of spectators, the well equipped huge auditoriums and theaters having excellent lighting and sound facilities and other means of technical support etc., also came up. With this, the reach of the Art expanded significantly. Now, not merely the well informed connoisseurs, but also the uninitiated audience began to have access to witness and enjoy Art performances. This has been a very healthy and a robust development.

Up to the early 20th century, the songs to which dances were composed were exclusively those rich in Srngara bhava. In the post-independence India, the dance themes were diversified to depict subjects other than the usual mythological and religious themes and of a heroine pining for her hero.

This shift played an important role in prompting the dancers to re-think and seek new directions in Indian dance and its thematic content. The Dancers with imagination and with the ability to reflect upon the present-day issues, began to experiment; to innovate dance-expressions; to create new movements using space, different levels; and, to develop an impressive array of dance vocabulary.

In India, Dance has always been an activity associated with socially, culturally and ritually sanctioned practices. And, the present period is the age of resurgence of the Indian classical dancing, freed from its past associations. The youth who pursue classical dance are the educated middle class, both in India and elsewhere. Today, Indian dances have crossed national borders; and, the exponents of Dancing in the Indian Diaspora have been extending their dance horizons, wherever they are.

In today’s world, the classical dance is an icon of high-art. It is also the representation of India’s preserved history, tradition and culture. It is a part of understanding our cultural heritage. The classical Dance as a specialized performing art draws fewer males than females. It, somehow, is essentially the domain of the females . It is, therefore, the women who, mostly, have carried forward this form of traditional art.

*

Dr. Kavitha Jaya Krishnan in her Doctoral Thesis “Dancing Architecture: The parallel evolution of Bharatanatyam and South Indian Architecture” (2011)– writes :

The shift from Gurukulas, to sampradaya patronage, to today’s global accessibility of the dance leaves the dance without an overseeing central body or alternatively with numerous institutions claiming authenticity. While this fragmentation affords the dance the opportunity for stylistic versatility and innovation, it also needs to address issues of artistic continuity and quality of teaching and performance.

The selectivity of 19th and 20th century artists revived a floundering dance tradition, but in the process, created a significant break in the narrative of the dance. Its alignment with a western notion of ‘neo-classicism’ aesthetic bears heavily on choreography and design, challenging Indian artists to maintain an important cultural identity across artistic, religious, political and geographic boundaries.

Bharatanatyam has developed into an iconographic representation of ‘Indian-ness’, linking and rooting communities and families back to a homeland overseas or back to a local ancestral village. There is an un-questionable interest in the dance as seen through its public popularity and financial investment. Middle-class Indian families happily send their daughters (and sons!) to dance class, considering it an important ‘cultural education’.

There are those however, financially and artistically inclined, who further their dance career professionally and/or academically. Unfortunately, this number remains small. The rich historical context of the dance is easily overlooked in a ‘pay-per-class environment and overly simplifies many controversial issues surrounding affected communities

The result is that now a dancer performs in a cultural void, isolated from the philosophical and religious context that gave her definition as a cultural nexus. The implication however, is not to force every dance student to an in-depth history les-son but a broader vehicle for ‘cultural education’ should be employed .

There is a dichotomy here. Fueled by the cross-currents of theory , practice and the ongoing innovations in the other contemporary fields of art , the artist in a zeal to create one’s own meaning, restructures and extends her/his little world , in order to evoke, to fathom, and to effectively represent varied human emotions and experiences. So long as the power of such created-language of art is rooted in the basic principles and is within the structure of the classic-tradition, the Indian dance forms such as, the Bharatanatya etc., retain their identity and authenticity. What is important in such shared aesthetic sensibilities, is retaining a sense of balance between the old and the new, which is continuity while still being rooted in one’s own tradition.

These are interesting and vibrant days for Indian classical Dance in its varied forms. With that, it has to face new challenges; and, has to address itself to new questions. It has to look within to review the techniques, the structural principles and to reassess the internal strength of its traditional forms. And, it has also to look forward and project its future path; to explore new horizons. It has to gain power and strength to carry forward the various Dance forms; and, at the same time have the tenacity to preserve the purity of the essential principles of the classical Dance. It has to find resilient ways to reflect the contemporary progressive values; and, continue to be relevant to the society and the world we live in. And, at the same time, it has to devise safeguards to protect the Art against the dangers of the rampant commercialization, which might affect the standards and the quality of the classical dance forms. It is the shared responsibility of the Gurus, the learners and the art connoisseurs.

And, that , indeed, is a very tall order.

Commencing from the next part, we shall briefly discuss each of the significant texts that defined the nature and practice of Dancing in India. We may, as always, start with Natyashastra; and, thereafter go to other texts, following their chronological order.

Smt. Sharada Srinivasan , in her research paper “Shiva as cosmic dancer” , writes : The Nataraja bronze in the sanctum at Chidambaram temple, depicting Shiva’s Ananda-Tandava or cosmic dance of creation and destruction, which is also the dance of bliss after annihilating the ego-was a Pallava innovation (seventh to mid-ninth century), rather than of tenth-century Chola period , as widely believed.

In this form, the four-armed Nataraja exhibits five primordial acts or Pancha-kritya: creation-symbolized by the drum in the rear right hand; protection- by the front right arm; dispelling of ignorance and ego – by trampling the demon Apasmara with his right foot; granting of solace- by the crossed left arm; destruction-by the fire in the rear left arm; while the encircling ring of fire symbolizes perpetual cosmic cycles

Continued

In

Part Six

References and sources

- 1.Natya Nrtta and Nrtya – their meaning and relations by Prof.KM Varma

- 2.http://www.svabhinava.org/abhinava/PadmaSubrahmanyam/PadmaSub.pdf

- 3.https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file%3Faccession%3Dosu1079459926%26disposition%3Dinline

- 4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3250274?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- 5. http://www.shreelina.com/odissi/alankara/The-Mirror-of-Gestures.pdf

- 6.http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/71949/8/08_chapter%203.pdf

- 7.The Evolution of Classical Indian Dance Literature: A Study of the Sanskritic Tradition by Dr. Mandakranta Bose

- 8.http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/164285

- 9 http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/164285/8/07_chapter%202.pdf

- 10. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/141247/8/08_chapter%203.pdf

- 11. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/106901

- Uparupakas and Nrtya-prabhandas by Dr. V Raghavan

All images are from the Internet