Continued from Part Eight

Vac and Sarasvathi

A. Vac

The Rig-Veda, in its several hymns, contains glorious references to the power of speech. An entire Sukta (RV. 10. 7l) – commencing with the words bṛhaspate prathamaṃ vāco agraṃ yat prairata nāmadheyaṃ dadhānāḥ – is devoted to the subject of speech; its various kinds ranging from the articulated to the in-articulate sounds in nature and to the gestures (ingita).

For the Vedic seers who herd and spoke about their experiences, speech was the most wonderful gift from the divine. The splendor and beauty of Vac, the personification of wisdom and eloquence, is sung in several hymns. It is said; the Rishis secured the power of divine speech through Yajna; studied it; and, revealed it for the benefit of the common people.

Yajnena vaeah padavlyan ayan tam anv avladan rslsa praviatam i tam abhnya vy adadhnh pnrutra tarn sapta rebha abhi sain navante (RV_10,071.03)

Vac is the inexplicable creative power of speech, which gives form to the formless; gives birth to existence ; and, lends identity to objects by naming them. It is the faculty which gives expression to ideas; calms the agitated minds; and, enables one to hear, see, grasp, and then describe in words or by other means the true nature of things. Vac is intimately associated with the Rishis and the riks (verses) that articulate or capture the truths of their visions. Vac, the navel of energy, the mysterious presence in nature, was, therefore, held in great reverence. Many of the later philosophical theories on this unique human faculty, the language, have their roots in Vedas.

[ While the Rishis of the early Vedas were overwhelmed by the power of speech, the philosophers of the Upanishads asked such questions as: who is the speaker? Who inspires one to speak? Can the speech truly know the source of its inspiration? They doubted; though the speech is the nearest embodiment of the in-dweller (Antaryamin) it might not truly know its source (just as the body cannot know its life-principle). Because, they observed, at the very beginning, the Word was un-uttered and hidden (avyahriam); it was silence. Ultimately, all those speculations led to the Self. But, again they said that Self is beyond mind and words (Avachyam; yato vacho nivartante, aprapya manasaa saha) ]

**

In the Rig-Veda, Vac, generally, denotes speech which gives an intelligent expression to ideas, by use of words; and it is the medium of exchange of knowledge. Vac is the vision, as also, the ability to turn that perceived vision into words. In the later periods, the terms such as Vani, Gira and such others were treated as its synonyms.

Yaska (Ca. 5th-6th BCE), the great Etymologist of the ancient India, describes speech (Vac) as the divine gift to humans to clearly express their thoughts (devim vacam ajanayanta- Nir. 11.29); and, calls the purified articulate speech as Paviravi – sharp as the resonance (tanyatu) of the thunderbolt which originates from an invisible power.

(Tad devata vak paviravi. paviravi cha divya Vac tanyatus tanitri vaco’nyasyah – Nir. 12.30).

Vac, the speech-principle (Vac-tattva), has numerous attributes and varied connotations in the Rig-Veda. Vac is not mere speech. It is something more sacred than ordinary speech; and , carries with it a far wider significance. Vac is the truth (ninya vachasmi); and, is the index of the integrity of one’s inner being. A true-speech (Satya-vac) honestly reflects the vision of the Rishi, the seer. It is through such sublime Vac that the true nature of objects, as revealed to the Rishis (kavyani kavaye nivacana), is expressed in pristine poetry. Their superb ability to grasp multiple dimensions of human life, ideals and aspirations is truly remarkable. Vac is , thus, a medium of expression of the spiritual experience of the Rig Vedic intellectuals who were highly dexterous users of the words. Being free from falsehood, Vac is described in the Rig-Veda as illuminating or inspiring noble thoughts (cetanti sumatlnam).

Chandogya Upanishad (7.2.1) asserts that Vac (speech) is deeper than its name (worldly knowledge) – Vag-vava namno bhuyasi – because speech is what communicates (Vac vai vijnapayati) all outer worldly knowledge as well as what is right and what is wrong (dharmam ca adharmam) ; what is true and what is false (satyam ca anrtam ca); what is good and what is bad (sadhu ca asadhu ca); and, what is pleasant and what is unpleasant (hrdayajnam ca ahrdayajnam ca). Speech alone makes it possible to understand all this (vag-eva etat sarvam vijnapayati). Worship Vac (vacam upassveti).

dharmam ca adharmam ca satyam ca anrtam ca sadhu casadhu ca hrdayajnam ca ahrdayajnam ca; yad-vai van nabhavisyat na dharmo nadharmo vyajnapayisyat, na satyam nanrtam na sadhu na’sadhu na hrdayajno na’hrdayajna vag-eva etat sarvam vijnapayati, vacam upassveti.

[Vac when translated into English is generally rendered as Word. That, however, is not a very satisfactory translation. Vac might, among many other things, also mean speech, voice, utterance, language, sound or word; but, it is essentially the creative force that brings forth all forms expressions into existence. It is an emanation from out of silence which is the Absolute. Vac is also the river and the embodied or god-personified as word, as well. It may not, therefore, be appropriate to translate Vac as Word in all events. One, therefore, always needs to take into account the context of its usage.]

There are four kinds of references to Vac in Rig Veda :

- Vac is speech in general;

- Vac also symbolizes cows that provide nourishment;

- Vac is also primal waters prior to creation; and,

- Vac is personified as the goddess revealing the word.

And, at a later stage, commencing with the Brahmanas, Vac gets identified with Sarasvathi the life-giving river, as also with the goddess of learning and wisdom.

According to Sri Sayana, Sarasvathi – Vac is depicted as a goddess of learning (gadya-padya rupena–prasaranmasyamtiti–Sarasvathi- Vagdevata).

Vac as Speech

As speech, the term Vāk or Vāc (वाक्), grammatically, is a feminine noun. Vac is variously referred to as – Syllable (akshara or Varna), word (Sabda), sentence (vakya), speech (Vachya), voice (Nada or Dhvani), language (bhasha) and literature (Sahitya).

While in the Rig-Veda, the Yajnas are a means for the propitiation of the gods, in the Brahmanas Yagnas become very purpose of human existence ; they are the ends in themselves. Many of the Brahmana texts are devoted to the exposition of the mystic significance of the various elements of the ritual (Yajna-kriya). The priests who were the adepts in explaining the objectives, the significance, the symbolisms and the procedural details of the Yajnas came into prominence. The all-knowing priest who presides over , and directs the course and conduct of the Soma sacrifice is designated as Brahma; while the three other sets of priests who chant the mantras are named as hotar, adhvaryu, and udgatru

Here, Brahman is the definitive voice (final-word); while the chanting of the mantras by the other three priests is taken to be Vac. Brahma (word) and Vac (speech) are said to be partners working closely towards the good (shreya) and for the fulfilment of the performer or the patron’s (Yajamana) aspirations (kamya). And, Brahma the one who presides and controls the course of the Yajna is accorded a higher position over the chanters of the mantras. It was said; Vac (chanting) extends so far as the Brahma allows (yaávad bráhma taávatii vaák– RV_10,114.08).

It was said; if word is flower, speech is the garland. And, if Vac is the weapons, it is Brahma that sharpens them –

codáyaami ta aáyudhaa vácobhih sám te shíshaami bráhmanaa váyaamsi. (RV 10.120.5 and 9.97.34)

According to Sri Sayana (Ca.14th century of Vijayanagara period and the brother of the celebrated saint Sri Vidyaranya), the seven-metres (Chhandas) revered for their perfection and resonance (Gayatrl, Usnih, Anustubh, Brihati, Pankti, Tristubh, and the Jagati) are to be identified with Vac.

Dandin (6th century), the poet-scholar, the renowned author of prose romance and an expounder on poetics, describes Vac as the light called Sabda (s’abdahvyam jyotih); and, states that “the three worlds would have been thrown into darkness had there been no light called Sabda”

- yadi śabdāhvayaṃ jyotir āsaṃsāraṃ na dīpyate // 1.4 //.

Bhartṛhari also asserted that, all knowledge is illumined through words, and it is quite not possible to have cognition that is free from words (tasmād arthavidhāḥ sarvāḥ śabdamātrāsu niśritāḥ – Vakyapadiya: 1.123); ‘no thought is possible without language’; and ’there is no cognition without the process of words’.

And, Bhartrhari declares- ‘It is Vac which has created all the worlds’-

- vageva viswa bhuvanani jajne (Vakyapadiya. 1.112)

The concept of Vac was extended to cover oral and aural forms such as : expression , saying , phrase , utterance sentence, and also the languages of all sorts including gesture (ingita).

Yaska says that all kinds of creatures and objects created by God speak a language of their own, either articulate or in-articulate

- (devastam sarvarupah pasavo vadanti, vyakta vac-ascha- avyakta- vacacha – Nir. 11.29).

He says that the Vac of humans is intelligible, articulate (vyakta vaco manushyadayah) and distinct (Niruktam); while the speech of the cows (animals) is indistinct (avyakta vaco gavayah).

Thus , Vac includes even the sounds of animals and birds; mewing of cows, crackle of the frogs, twitter of the birds, sway of the trees and the breeze of hills; and also the sounds emanated by inanimate objects such as : the cracking noise of the fissures in the stones due to friction ; as also the beats of drum , the sound of an instrument.

Even the rumbling of the clouds, the thunder of the lightening and the rippling sounds of the streams are said to be the forms of Vac

(praite vadantu pravayam vadama gravabhyo vacam vadata vadadbhyah – RV. 10.94.1)

It was said; the extant of Vac is as wide as the earth and fire. Vac is even extolled as having penetrated earth and heaven, holding together all existence. As Yaska remarks: Vac is omnipresent and eterna1 (vyaptimattvat tu Sabdasya – Nir.I.2)

Vac (word) belongs to both the worlds – the created and un-created. It is both the subject of speech and the object of speech.

The Tantra ideology identified Vac with the vibrations of the primordial throb (adya-spanda) that set the Universe in motion; and , said that all objects of the Universe are created by that sound –artha-srsteh puram sabda-srstih.

Thus, Vac broadly represents the spoken word or speech; its varied personified forms; and also the oral and aural non-literary sounds forms emanating from all animal and plant life as also the objects in nature. Vac is, verily, the very principle underlying every kind of sound, speech and language in nature.

And, Vac goes beyond speech. Vac is indeed both speech and consciousness (chetana), as all actions and powers are grounded in Vac. It is the primordial energy out of which all existence originates and subsists. Vac is also the expression of truth.

Yajnavalkya in the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad explaining the relation between Vac and consciousness says that Vac (speech) is a form of expression of consciousness. And, he argues, there could be no speech without consciousness. However, Consciousness does not directly act upon the principle of speech; but , it operates through intermediary organs and breath to deliver speech.

*

Rishi Dīrghatamas goes far beyond; and, exclaims: Vac is at the peak of the Universe (Agre paramam) ; She is the Supreme Reality (Ekam Sat; Tad Ekam) ; She resides on the top of the yonder sky ; She knows all ; but, does not enter all”-

- Mantrayante divo amuṣya pṛṣṭhe viśvavidaṃ vācam aviśvaminvām – RV.1.164.10)

Vac , he says, is the ruler of the creative syllable Ra (Akshara) ; it is with the Akshara the chaotic material world is organized meaningfully ; “what will he , who does not know Ra will accomplish anything .. ! “.

ṛco akṣare parame vyoman yasmin devā adhi viśve niṣeduḥ | yas tan na veda kim ṛcā kariṣyati ya it tad vidus ta ime sam āsate |RV.1.164.39|

That is because, Dirghatamas explains, the whole of existence depends on Akshara which flowed forth from the Supreme Mother principle Vac –

- tataḥ kṣaraty akṣaraṃ tad viśvam upa jīvati |RV.1.164.42 |

According to Dirghatamas: “When I partake a portion of this Vac, I get the first part of truth, immediately-

- (maagan-prathamaja-bhagam-aadith-asya-Vac)”-(RV. I.164.37.)

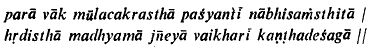

But, he also says: “Vac has four quarters; only the wise that are well trained, endowed with intelligence and understanding know them all. For the rest; the three levels remain concealed and motionless. Mortals speak only with the fourth (RV. 1.164.45).”

Chatvaari vaak parimitaa padaani / taani vidur braahmaanaa ye manishinaah. Guhaa trini nihitaa neaengayanti / turiyam vaacho manushyaa vadanti. (Rigveda Samhita – 1.164.45)

Vac as goddess

Vac is also Vac Devi the divinity personified. Vac is called the supreme goddess established in Brahman Iyam ya paramesthini Vac Devi Brahma-samsthita (Rig-Veda.19.9.3).

She gives intelligence to those who love her. She is elegant, golden hued and embellished in gold (Hiranya prakara). She is the mother, who gave birth to things by naming them. She is the power of the Rishis. She enters into the inspired poets and visionaries, gives expression and vitality to those she blesses; and, enables them to turn precious knowledge into words. She is also said to have entered into the sap (Rasa) of plants and trees, pervading and enlivening all vegetation (Satapatha-brahmana 4.6.9.16).

vāk-tasyā eṣa raso yadoṣadhayo yad vanaspataya-stametena sāmnāpnuvanti sa enānāpto ‘bhyāvartate tasmād asyām ūrdhvā oṣadhayo jāyanta ūrdhvā vanaspatayaḥ

It is said; Vac is the first offspring of the Rta, the cosmic order or principle or the Truth (Satya). And that Truth (Rta) is not static or a mere question of morality; but, it is the dynamic order of the entire reality out of which the whole of existence comes into being . Vac is proclaimed as the mother of the Vedas and as immortal. Again, it is said that Prajapati produced goddess Vac so that she may be omnipresent and propel all activities. She is Prakrti. In the later Vedic traditions, Vac is hailed as the very reflection of the greatness of the creator – vagva asya svo mahima (SB., 2.2.4.4.); and, in the Nighantu (3.3), Vac occurs as a synonym of the terms describing greatness, vastness etc – mahat, brhat.

And, at one place, Vac is identified with Yajna itself unto whom offerings are made – Vac vai yajanam (Gopatha Br. 2.1.12). Further, Vac is also the life-supporting Soma; and , for that reason Vac is called Amsumathi, rich with Soma.

The idea of personifying Vac as a goddess in a series of imagery associating her with creation, Yajna and waters etc., and her depiction as Shakthi richly developed in the later texts, is said to have been inspired by the most celebrated Vak Suktha or Devi Suktha or Vagambhari Sukta (Rig Veda: 10.125) . Here, the daughter of Ambhrna, declares herself as Vac the Queen of the gods (Aham rastri), the highest principle that supports all gods, controls all beings and manifests universally in all things.

Aham rastri samgamani vasunam cikitusi prathama yajniyanam / Tam ma deva vy adadhuh purutra Bhunisthatram bhury avesayantim // 3

She declares: It is I who blow like the wind, reaching all beings (creatures). Beyond heaven and beyond the earth I have come-to-be by this greatness.

Ahameva vata iva pra vamyarabhamana bhuvanani visva / paro diva para ena prthivyaitavat mahina sarri babhuva // 8

Vac, the primal energy the Great Mother Goddess, is thus described in various ways.

Vac is identified with all creation which she pervades and at the same time she spreads herself far beyond it. She is the divine energy that controls all and is manifest in all beings:

- ‘tam ma deva vyadadhuh purutra / bhuristhatram bhurya vesayantim’.

Whatever the gods do they do so for her; and, all activities of living beings such as thinking, eating, seeing, breathing, hearing etc., are because of her grace.

[At another level, it is said; there are three variations of Vac the goddess – Gauri Vac, Gauh Vac and Vac.

Of these, the first two goddesses are said to be personifications of the sound of thunder, whereas the goddess Vac is a deity of speech or sounds uttered or produced by earthly beings.

Gauri Vac, described as having a number of abodes (adhisthana-s) in various objects and places like the clouds, the sun, the mid-region, the different directions so on , is said to be associated with sending forth rains to the earth, so that life may come into being, flourish and prosper on it perpetually.

Gauh Vac on the other hand is described in a highly symbolical language portrayed as cow. In the traditional texts, Vac, which expresses the wonder and mysteries of speech, was compared to the wish-fulfilling divine cow (dhenur vagasman, upasustutaitu –RV. 8.100.11).

And, in the much discussed Asya Vamiya Sukta ascribed to Rishi Dirghatamas, Vac again is compared to a cow of infinite form which reveals to us in various forms – Rig Veda 1.164.

gaurīr mimāya salilāni takṣaty ekapadī dvipadī sā catuṣpadī | aṣṭāpadī navapadī babhūvuṣī sahasrākṣarā parame vyoman | RV_1,164.41|

Gauh Vac is symbolically depicted as a milch-cow that provides nourishment; and one which is accompanied by her calf (please see note below *). She constantly cuddles her calf with great love, and lows with affection for her infant

– gauh ramī-medanu vatsaṃ miṣantaṃ mūrdhānaṃ hiṃ akṛṇean mātavā u (1.164.55) .

It is explained: the rains are her milk, the lowing sound made by her is the sound of thunder ;and, the calf is the earth. Gauh Vac is hailed in the Rig-Veda (8.101.15) as the mother principle, the source of nourishment (pusti) of all existence; and bestowing immortality (amrutatva).

tasyāḥ samudrā adhi vi kṣaranti tena jīvanti pradiśaś catasraḥ | tataḥ kṣaraty akṣaraṃ tad viśvam upa jīvati |1.164.42|

And Vac is the goddess of speech; and, her origins too are in the mid-regions (atmosphere). Just as Gauh Vac, she also is compared to a milch cow that provides food, drink and nourishment to humans.

And again, the goddess Vac and goddess Sarasvathi are both described as having their origin or their abodes in the mid-region (Antariksha). Both are associated with showering the life-giving rains on the parched earth. And, Sarasvathi is also said to shower milk, ghee, butter, honey and water to nourish the student (adhyéti) reciting the Pavamani (purification) verses which hold the essence of life (Rasa) , as gathered by the Rishis (ŕ̥ṣibhiḥ sámbhr̥taṃ) – (Rig-Veda. 9.67.32).

Pāvamānī́r yo adhyéti ŕ̥ṣibhiḥ sámbhr̥taṃ rásam | tásmai sárasvatī duhe kṣīráṃ sarpír mádhūdakám // 9.67.32| ]

[* Note on cow

It is said; the nature speaks through its created objects. It is its own language; the language of symbols (Nidana-vidya). The language of symbols is elastic; suggesting multiple interpretations. We all strive to retrieve their meaning closeted at the core of such symbols, shrouded in mystery (Bhuteshu -Bhuteshu vichitya dhirah – KU.2.5).

Our ancients, recognized the infinite tolerence and the loving quality of the Motherhood in the Earth, which supports and sustains the whole of this existence. They again related the generative potency of the Mother Nature to the Cow, which feeds and nurtures all of us, with patience. The Cow, in turn, was seen as the symbol of the language, giving forth to limitless forms, sounds, words and meanings (Dhenur Vac asman upa sushtutaitu – RV. 8.100.11).

The Universal-Cow-principle (Gauh-tattva) was,thus, seen as a symbol of the Thousand-syllabled speech (Vag va idam Nidanena yat sahasri gauh; tasya-etat sahasram vachah prajatam – SB.4.5.8.4).

Similarly, the fleeting quality of the Gayatri Meter (Chhandas) was said to reflect the flaming glow of Agni, the fire-principle (Yo va atragnir Gayatri sa nidanena – SB.1.8.2.15).

And, even here, the words are mere symbols of the ideas; trying to manifest the un-manifest subtle thoughts and feelings. The words belong to the physical world; but, they radiate from a much deeper transcendental, inspirational source that is ever innovative (Pratibha).

*

Following the concept of Nidana-vidya, in the early texts, the cow is compared to Earth as an exemplary symbol of Motherhood. She is the life-giving, nourishing Mother par excellence , who cares for all beings and nature with selfless love and boundless patience. The Mother goddesses such as Aditi, Prithvi, Prsni (mother of Maruts), Vac, Ushas and Ila all are represented by the cow-symbolism.

Further, the nourishing and life-supporting rivers too are compared to cows (e.g. RV. 7.95.2; 8.21.18). For instance; the Vipasa and the Sutudri the two gentle flowing rivers are said to be like two loving mothers who slowly lick their young-lings with care and love (RV . 3,033.01) – gāveva śubhre mātarā rihāṇe vipāṭ chutudrī payasā javete

The cow in her universal aspect is lauded in RV.1.164.17 and RV. 1.164.27-29. She manifests herself together with her calf; she is sacrosanct (aghanya), radiant, the guardian mother of Vasus. She created the whole of existence by her will.

Sri Aurobindo explains: in many of these hymns, milk (literally, that which nourishes) represents the pure white light of knowledge and clarified butter the resultant state of a clear mind or luminous perception, with bliss, symbolized by the honey (or Soma), as the essence of both. ]

Vac as Water (Apah)

Vac is sometimes identified with waters, the primeval principle for the creation of the Universe.

In the Vak Suktha or Devi Suktha of Rig Veda (RV.10. 10.125), Apah, the waters, is conceived as the birth place of Vac. And, Vac who springs forth from waters touches all the worlds with her flowering body and gives birth to all existence. She indeed is Prakrti. Vac is the creator, sustainer and destroyer. In an intense and highly charged superb piece of inspired poetry Vac declares “I sprang from waters there from I permeate the infinite expanse with a flowering body. I move with Rudras and Vasus. I walk with the Sun and other Gods. It is I who blows like the wind creating all the worlds”.

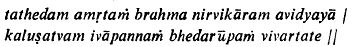

Vac as Brahman

Ultimately, Vac is identified with Brahman, the Absolute.

:- According to Sri Sayana, the Vak Suktha or Devi Suktha is a philosophical composition in which Vac the Brahmavidushi daughter of seer Ambhrna, after having realised her identity with Brahman – the ultimate cause of all, has lauded her own self. As such , she is both the seer and Vac the deity of this hymn. And Vac, he asserts, is verily the Brahman.

saccit sukhatmakah sarvagatah paramatma devata / tena hyesa tadatmyam anubhavanti sarva- jagadrupena , sarvasyadhistanatvena sarvam bhavamti svatmanam stauti – (Sri Sayana on 10.125.1)

:- In the fourth chapter of the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, Yajnavalkya speaking about the nature of Vac, equated it with the Brahman (vāg vai brahmeti)

: – The Jaimimya Upanishad Brahmana (2.8.6) also states that Vac indeed is the Brahman – Vagiti Brahma

: Similarly the Aittariya Brahmana (4.211) declares: Brahma vai vak

: – Bhartrhari commences his work of great genius, the Vakyapadia, with the verse (Shastra-arambha):

Anādinidhana Brahma śabdatattvaṃ yadakṣaram / vivartate arthabhāvena prakriyā jagato yataḥ– VP.1.1.

[The ultimate reality, Brahman, is the imperishable principle of language, without beginning and end, and the evolution of the entire world occurs from this language-reality in the form of its meaning.]

It is explained; the Sabda, mentioned here is just not the pronounced or uttered word; it is indeed the Vac existing before creation of the worlds. It is the Vac that brings the world into existence. Bhartrhari, thus, places the word-principle – Vac – at the very core (Bija) of existence That Vac, – according to Bhartrhari is not merely the creator and sustainer of the universe but is also the sum and substance of it.

And, Vac as Sabda-Brahman is the creative force that brings forth all existence. Vac is also the consciousness (chit, samvid), vital energy (prana shakthi) that vibrates (spanda). It is an emanation from out of silence, which is the Absolute.

That Sabda-tattva (Sabdasya tattvam or Sabda eva tattvam) of Bhartrhari is of the nature of the Absolute; and, there is no distinction between Sabda Brahman and Para Brahman the Supreme Principle (Para tattva).

: – Vac was considered manifestation of all-pervading Brahman; and, Pranava (Aum) was regarded the primordial speech-sound from which all forms of speech emanated

B. Sarasvathi

In the Rig-Veda, Sarasvathi is the name of the celestial river par excellence (deviyā́m), as also its personification as a goddess (Devi) Sarasvathi, filled with love and bliss (bhadram, mayas).

And Sarasvathi is not only one among the seven sister-rivers (saptásvasā), but also is the dearest among the gods (priyā́ deveṣu).

Again, it is said, the Sarasvathi as the divine stream has filled the earthly regions as also the wide realm of the mid-world (antárikṣam) –

- āpaprúṣī pā́ rthivāni urú rájo antárikṣam | sárasvatī nidás pātu | RV_6,061.11)

Sarasvathi as the River

Invoked in three full hymns (R V.6.6.61; 7.95; and 7.96) and numerous other passages, the Sarasvathi, no doubt, is the most celebrated among the rivers.

It is said; the word Sarasvathi is derived from the root ‘Sarah’, meaning water (as in Sarasi-ja, lotus – the one born in water). In the Nighantu (1.12), Sarah is one of the synonyms for water. That list of synonyms for water, in the Nighantu, comes immediately next to that of the synonyms for speech (Vac). Yaska also confirms that the term Sarasvathi primarily denotes the river (Sarasvathi Sarah iti- udakanama sartes tad vati –Nirukta.9.26). Thus, the word Sarasvathi derived from the word Sarah stands for Vagvathi (Sabdavathi) and also for Udakavathi.

The mighty Sarasvathi , the ever flowing river, is also adored as Sindhu-mata, which term is explained by Sri Sayana as ‘apam matrubhuta’ the mother-principle of all waters; and also as ‘Sindhunam Jalam va mata’ – the Mother of the rivers , a perennial source of number of other rivers .

The Sarasvathi (Sarasvathi Saptathi sindhu-mata) of the early Vedic age must have been a truly grand opulent river full of vigour and vitality (Sarasvathi sindhubhih pinvamana- RV.6.52.6) on which the lives of generations upon generations prospered (hiranyavartnih).

[The geo-physical studies and satellite imagery seems to suggest that the dried up riverbed of the Ghaggar-Hakra might be the legendary Vedic Saraswati River with Drishadvati and Apaya as its tributaries. For more ; please check Vedic river and Hindu civilization edited by Dr. S. Kalyanaraman.

It is said in the Rig-Veda; on the banks of Sarasvathi the sages (Rishayo) performed yajnas (Satram asata) – Rishayo vai Sarasvathyam satram asata). The Rig-Veda again mentions that on the most auspicious days; on the most auspicious spot on earth; on the banks of the Drishadvati, Apaya and Sarasvathi Yajnas (Ahanam) were conducted.

ni tva dadhe vara a prthivya ilayspade sudinatve ahnam; Drsadvaty am manuse apayayam sarasvatyamrevad agne didhi – RV_3,023.04 ]

There are abundant hymns in the Rig-Veda, singing the glory and the majesty of the magnificent Sarasvathi that surpasses all other waters in greatness , with her mighty (mahimnā́, mahó mahī́ ) waves (ūrmíbhir) tearing away the heights of the mountains as she roars along her way towards the ocean (ā́ samudrā́t).

Riṣhi Gṛtsamada adores Sarasvathi as the divine (Nadinam-asurya), the best of the mothers, the mightiest of the rivers and the supreme among the goddesses (ambitame nadltame devitame Sarasvati). And, he prays to her: Oh Mother Saraswati, even though we are not worthy, please grant us merit.

Ámbitame nádītame dévitame sárasvati apraśastā ivasmasi praśastim amba naskṛdhi – (RV_2,041.16)

Sarasvathi is the most sacred and purest among rivers (nadinam shuci). Prayers are submitted to the most dear (priyatame) seeking refuge (śárman) in her – as under a sheltering tree (śaraṇáṃ vr̥kṣám). She is our best defence; she supports us (dharuṇam); and, protects us like a fort of iron (ā́yasī pū́ḥ).

The Sarasvathi , the river that outshines all other waters in greatness and majesty is celebrated with love and reverence; and, is repeatedly lauded with choicest epithets, in countless ways:

:- uttara sakhibhyah (most liberal to her friends);

:- vegavatinam vegavattama (swiftest among the most speedy);

:- pra ya mahimna mahinasu cekite dyumnebhiranya apasamapastama – the one whose powerful limitless (yásyā anantó) , unbroken (áhrutas) swiftly flowing (cariṣṇúr arṇaváḥ) impetuous resounding current and roaring (róruvat) floods, moving with rapid force , like a chariot (rathíyeva yāti), rushes onward towards the ocean (samudrā́t) with tempestuous roar;

:- bursting the ridges of the hills (paravataghni) with mighty waves .. and so on.

yásyā anantó áhrutas tveṣáś cariṣṇúr arṇaváḥ | ámaś cárati róruvat | (RV_6,061.08)

The Sarasvathi, most beloved among the beloved (priyā́ priyā́ su) is the ever-flowing bountiful (subhaga; vā́jebhir vājínīvatī) energetic (balavati) stream of abounding beauty and grace (citragamana citranna va) which purifies and brings fruitfulness to earth, yielding rich harvest and prosperity (Sumrdlka).

She is the source of vigor and strength.

Her waters which are sweet (madhurah payah) have the life-extending (ayur-vardhaka) healing (roga-nashaka) medicinal (bhesajam) powers – (aps-vantarapsu bhesaja-mapamuta prasastaye – RV_1,023.19).

She is indeed the life (Jivita) and also the nectar (amrtam) that grants immortality. Sarasvathi, our mother (Amba! yo yanthu) the life giving maternal divinity, is dearly loved as the benevolent (Dhiyavasuh) protector of the Yajna – Pavaka nah Sarasvathi yagnam vashtu dhiyavasuh (RV_3,003.02).

She personifies purity (Pavaka);

Sarasvathi is depicted as a purifier (pavaka nah sarasvathi) – internal and external. She purifies the body, heart and mind of men and women- viśvaṃ hi ripraṃ pravahanti devi-rudi-dābhyaḥ śucirāpūta emi | (10.17.20); and inspires in them pure, noble and pious thoughts (1.10.12). Sarasvathi also cleanses poison from men, from their environment and from all nature –

uta kṣitibhyo, avanīr avindo viṣam ebhyo asravo vājinīvati (RV_6,061.03).

Prayers are submitted to Mother Sarasvathi, beseeching her: please cleanse me and remove whatever sin or evil that has entered into me. Pardon me for whatever evils I might have committed, the lies I have uttered, and the false oaths I might have sworn.

Idamapah pravahata yat kimca duritam mayi, yad vaaham abhi dudroha, yad va sepe utanrtam (RV.1.23.22)

The beauty of Sarasvathi is praised through several attributes, such as: Shubra (clean and pure); Suyanam, Supesha, Surupa (all terms suggesting a sense of beauty and elegance); Su-vigraha (endowed with a beauteous form) and Saumya (pleasant and easily accessible). Sri Sayana describes the beauteous form of Sarasvathi: “yamyate niyamytata iti yamo vigrahah, suvigraha…”

Sarasvathi is described by a term that is not often used : ’ Vais’ambhalya’ , the one who brings up, nurtures and protects the whole of human existence – visvam prajanam bharanam, poshanam – with abundant patience and infinite love. Sri Sayana, in his Bhashya (on Taittiriya-Brahmana, 2. 5.4.6) explains the term as: Vlsvam prajanam bharanam poshanam Vais’ambham tatkartum kshama vaisambhalya tidrsi.

Thus, the term Vais’ambhalya, pithily captures the nature of the nourishing, honey-like sweet (madhu madharyam) waters of the divine Sarasvathi who sustains life (vijinivathi) ; enriching the soil ; providing abundant food (anna-samrddhi-yukte; annavathi) and nourishment (pusti) to all beings; causing overfull milk in cows (kshiram samicinam); as Vajinivathi enhancing vigour and strength in horses ( vahana-samarthyam) ; and , blessing all of existence with happiness (sarvena me sukham ) – (Sri Sayana’s Bhashya on Taittiriya-Brahmana).

Sarasvathi as goddess

Yaska mentions that Sarasvathi is worshipped both as the river (Nadi) and as the goddess (Devata) –

vāc.kasmād, vaceh / tatra. sarasvatī. ity. etasya. nadīvad. devatāvat . ca . nigamā. bhavanti. tad. yad. devatāvad. uparistāt. tad .vyākhyāsyāmah / atha . etat. nadīvat/ /– Nirukta.2.23

Yaska (at Nir. 2,24) , in his support, cites Verses from Rig-Veda (6.61.2-4) – (it’s Pada Patha is given under)

iyam | śuṣmebhiḥ | bisakhāḥ-iva | arujat | sānu | girīṇām | taviṣebhiḥ | ūrmi-bhiḥ | pārāvata-ghnīm | avase | suvṛkti-bhiḥ | sarasvatīm | ā | vivāsema | dhīti-bhiḥ // RV_6,61.2 / // sarasvati | deva-nidaḥ | ni | barhaya | pra-jām | viśvasya | bṛsayasya | māyinaḥ | uta | kṣiti-bhyaḥ | avanīḥ | avindaḥ | viṣam | ebhyaḥ | asravaḥ | vājinī-vati // RV_6,61.3 // pra | naḥ | devī | sarasvatī | vājebhiḥ | vājinī-vatī | dhīnām | avitrī | avatu // RV_6,61.4 //

Yaska categorizes Sarasvathi as the goddess of mid-region – Madhya-sthana striyah.

Sri Sayana commenting on RV. 1.3.12, also mentions that Sarasvathi was celebrated both as river and as a deity –

- Dvi-vidha hi Sarasvathi vigrahavad-devata nadi rupa-cha.

Following Yaska, Sri Sayana also regarded Sarasvathi as a divinity of the mid-region- ‘madhyama-sthana hi vak Sarasvathi’; and as a personification of the sound of thunder.

Thus, Sarasvathi, a deity of the atmosphere is associated with clouds, thunder, lightening, rains and water. As Sri Aurobindo said; the radiant one has expressed herself in the forming of the flowing Waters.

[Sri Aurobindo explaining the symbolism of thunder and lightning, says: the thunder is sound of the out-crashing of the word (Sabda) of Truth (Satya-vac); and, the lightning as the out-flashing of its sense (Artha) ]

John Muir (Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India) remarks: It seems that Vedic seers were not satisfied with the river-form of Sarasvati; and, in order to make the river a living and active entity that alone could hear them, they regarded it as a river-goddess.

Thus, Sarasvati is a river at first; and, later conceived as a goddess

Sarasvathi, the best of the goddesses (Devi-tame) and the dearest among the gods (priyā́ deveṣu) is associated with Prtri-s (departed forefathers – svadhā́ bhir Devi pitŕ̥bhir; sárasvatīṁ yā́m pitáro hávante) as also with many other deities and with the Yajna. She is frequently invited to take seat in the Yajnas along with other goddesses such as: Ila, Bharathi, Mahi, Hotra, Varutri, Dishana Sinivali, Indrani etc.

She is also part of the trinity (Tridevi) of Sarasvathi, Lakshmi and Parvati.

Sarasavathi as Devata, the Goddess is also said to be one of the three aspects of Gayatri (Tri-rupa – Gayatri): Gayatri, Savitri and Sarasvathi. Here, while Gayatri is the protector of life principles; Savitri of Satya (Truth and integrity of all Life); Sarasvathi is the guardian of the wisdom and virtues of life. And, again, Gayatri , herself, is said to manifest in three forms: as Gayatri the morning (pratah-savana) as Brahma svarupini; Savitri in the midday (madyanh savana) as Rudra svarupini; and, as Sarasvathi in the evening (saayam savana) as Vishnu svarupini.

[ Sri Aurobindo interprets the divine Sarasvathi, the goddess of the Word, the stream of inspiration as: an ever flowing great flood (mahó árṇaḥ) of consciousness; the awakener (cétantī, prá cetayati) to right-thinking (sumatīnām); as inspirer (codayitrī) who illumines (vi rājati) all (víśvā) our thoughts (dhíyo); and, as truth-audition, śruti, which gives the inspired perception (ketúnā) – mahó árṇaḥ sárasvatī prá cetayati ketúnā | dhíyo víśvā ví rājati – RV_1,003.12]

Prayers are also submitted to Sarasvathi to grant great wealth (abhí no neṣi vásyo), highly nourishing food (póṣaṁ, páyasā) and more progeny (prajā́ṁ devi didiḍḍhi naḥ); to treat us as her friends (juṣásva naḥ sakhiyā́ veśíyā); and, not let us stray into inhospitable fields (mā́ tvát kṣétrāṇi áraṇāni gamma) – RV. 6-61-14. Sarasvathi, thus, is also Sri.

The goddess Sarasvathi is also the destroyer of Vrta and other demons that stand for darkness (Utasya nah Sarasvati ghora Hiranyavartanih / Vrtraghni vasti sustuition).

In the Rig-Veda, the goddess Sarasvathi is associated, in particular with two other goddesses: Ila and Bharathi.

The Apri Sukta hymns (the invocation hymns recited just prior to offering the oblations into Agni) mention a group of three great goddesses (Tisro Devih) – Ila, Bharathi and Sarasvathi – who are invoked to take their places and grace the . They bring delight and well-being to their devotees.

ā no yajñaṁ bhāratī tῡyam etu, iḷā manuṣvad iha cetayantī; tisro devīr barhir edaṁ syonaṁ, sarasvatī svapasaḥ sadantu- RV_10,110.08

The three -Ida, Bharathi and Sarasvathi – who are said to be manifestations of the Agni (Yajnuagni), are also called tri-Sarasvathi.

[In some renderings, Mahi (ṛtaṁ bṛhat , the vast or great) is mentioned in place of Bharathi: Ila, Sarasvathi, Mahi tisro devir mayobhuvah; barhih sIdantvasridah. And Mahi, the rich, delightful and radiant (bṛhat jyotiḥ) goddess of blissful truth (ṛtaṁ jyotiḥ; codayitrī sῡnṛtānām), covering vast regions (varῡtrī dhiṣaṇā) is requested to bring happiness to the performer of the Yajna, for whom she is like a branch richly laden with ripe fruits (evā hyasya sῡnṛtā, virapśī gomatī mahī; pakvā śākhā na dāśuṣe – RV_1,008.08).

And, Ila is sometimes mentioned as Ida. ]

Among these Tisro Devih, Sarasvathi, the mighty, illumines with her brilliance and brightness, inspires all pious thoughts – cetantī sumatīnām (RV.1.3.12 ;). Her aspects of wisdom and eloquence , which enlighten all this world (dhiyo viśvā vi rājati) , are praised, sung in several hymns. She evokes pleasant songs, brings to mind gracious thoughts; and she is requested to accept our offerings (RV.1.3.11)

codayitrī sūnṛtānāṃ cetantī sumatīnām | yajñaṃ dadhe sarasvatī ||maho arṇaḥ sarasvatī pra cetayati ketunā | dhiyo viśvā vi rājati ||RV.1.3.11-12

Bharathi is hailed as speech comprising all subjects (sarva-visaya-gata vak) and as that which energizes all beings (Visvaturith)

Ila is a gracious goddess (sudanuh, mrlayanti devi). She is personified as the divine cow, mother of all realms (yuthasya matha), granting (sudanu) bounteous gifts of nourishments. She has epithets, such as: Prajavathi and Dhenumati (RV. 8.31. 4). She is also the personification of flowing libation (Grita). She is the presiding deity of Yajna, in general (RV.3.7.25)

iḷām agne purudaṃsaṃ saniṃ goḥ śaśvattamaṃ havamānāya sādha | syān naḥ sūnus tanayo vijāvāgne sā te sumatir bhūtv asme ||RV_3,007.11

According to Sri Sayana, Ila – as nourishment, (RV.7.16.8) is the personification of the oblation (Havya) offered in the Yajna (annarupa havir-laksana devi). Such offerings of milk and butter are derivatives of the cow. And Ila, in the Brahmana texts, is related to the cow. And, in the Nighantu (2.11), Ila is one of the synonyms of the cow. Because of the nature of the offering, Ila is called butter-handed –

- ghṛta-hastā (RV. 7.16.15) and butter-footed – devī ghṛta padī juṣanta (RV. 10,070.08).

…

The three goddesses (Tisro Devih) are interpreted as: three goddesses representing three regions: Ida the earth; Sarasvathi the mid-region; and Bharathl, the heaven. And again, these three goddesses are also said to be three types of speech.

Sri Sayana commenting on the verse tisro vāca īrayati pra vahnirtasya dhītiṃ brahmaṇo manīṣām |… (RV.9.97.67), mentions Ida (Ila), Sarasvathi and Bharathi as the levels of speech or languages spoken in three regions (Tripada, Tridasatha – earth, firmaments and heaven).

Among these goddesses, he names Bharathi as Dyusthana Vac (upper regions); Sarasvathi as Madhyamika Vac (mid-region); and Ida as the speech spoken by humans (Manushi) on the earth (prthivi praisadirupa). Another interpretation assigns Bharathi, Sarasvathi and Ila the names of three levels of speech: Pashyanti, Madhyama and Vaikhari..

According to Sri Aurobindo, Ida, Sarasvathi and Bharathi represent Drsti (vision), Sruti (hearing) and Satya the integrity of the truth-consciousness.

C. Vac identified with Sarasvathi

Rig-Veda does not, of course, equates Vac with Sarasvathi. But, it is in the Brahmana texts, the Nighantu, the Nirukta and the commentaries of the traditional scholars that Vac is identified with Sarasvathi, the Madhyamika Vac. The later Atharva-veda also speaks of Vac and Sarasvathi as one

It is particularly in the Brahmana that the identity of Vac with Sarasvathi begins – ‘vag vai Sarasvathi’ (Aitareya Brahmana 3.37). The notions such as – the one who worships Sarasvathi pleases Vac, because Vac is Sarasvathi – take root in the Brahmanas (yat sarasvatlm yajati vag vai sarasvatl; vacam eva tat prlnati atha – SB. 5.2).

And, Gopatha Brahmana (2.20) in an almost an identical statement says that worship of Sarasvathi pleases Vac, because Vac is Sarasvathi (atha yat sarasvatim yajati, vag vai Sarasvathi, vacham eva tena prinati).

Also, in the ancient Dictionary, the Nighantu (1.11), the term Sarasvathi is listed among the synonym s of Vac.

Such identification of Vac with Sarasvathi carries several connotations, extending over to the Speech; to the sacred river; and, to the delightful goddess inspiring true speech and sharp intellect, showering wisdom and wealth upon one who worships her devotedly.

As speech

As speech, Sarasvathi as Vac is adored as the power of truth, free from blemishes; inspiring and illuminating noble thoughts (chetanti sumatim). In the Taittariya Brahmana, the auspicious (subhage), the rich and plentiful (vajinivati) Vac is identified with Sarasvathi adored as the truth speech ‘Satya-vac’.

Sarasvathi subhage vajinlvati satyavachase bhare matim. idam te havyam ghrtavat sarasvati. Satyavachase prabharema havimsi- TB. II. 5.4.

The Vac-Sarasvathi, the power of speech, is hailed as the mother of Vedas – Veda Mata. She is the abode of all knowledge; the vast flood of truth (Maho arnah); the power of truth (Satya vacs); the guardian of sublime thoughts (dhinam avitri); the inspirer of good acts and thoughts; the mother of sweet but truthful words; the awakener of consciousness (chodayitri sunrtanam, chetanti sumatinam); the purifier (Pavaka); the bountiful blessing with vast riches (vajebhir vajinivati); and the protector of the Yajna (yajnam dadhe).

Pavaka nah Sarasvathi, vajebhir vajinivati; yajnam vastu dhiyavasuh. Chodayitri sunrtanam, cetanti sumatinam; yajnam dadhe Sarasvathi. Maho arnah Sarasvathi, pra cetayati ketuna; dhiyo visva vi rajati. (Rig-Veda. 4.58.1)

[Sri Aurobindo’s translation: “May purifying Sarasvathi with all the plenitude of her forms of plenty, rich in substance by the thought, desire our sacrifice.”She, the impeller to happy truths, the awakener in consciousness to right metalizing, Sarasvathi, upholds the sacrifice.” “Sarasvathi by the perception awakens in consciousness the great flood (the vast movement of the ritam) and illumines entirely all the thought.]

Vac- Sarasvathi is regarded the very personification of pure (pavaka) thoughts, rich in knowledge or intelligence (Prajna or Dhi) – (vag vai dhiyavasuh)

Pavaka nah sarasvatl yajnam vastu dhiyavasur iti vag vai dhiyavasuh – AB. 1.14.

In the Shata-patha-Brahmana (5. 2.2.13-14) , Vac as Sarasvathi is first taken to be her controlling power, the mind (manas), the abode of all thoughts and knowledge, before they are expressed through speech.

sarasvatyai vāco yanturyantriye dadhāmīti vāgvai sarasvatī tadenaṃ vāca eva yanturyantriye dadhāti – 5. 2.2.13

Again, the Shata-patha-Brahmana (I.4.4.1; 3.2.4.11) mentions the inter-relations among mind (manas), breath (prana) and Speech (Vac). The speech is evolved from mind; and put out through the help of breath. The speech (Vac) is called jlhva Sarasvati i.e., tongue, spoken word. Vac-Sarasvathi is also addressed as Gira, one who is capable to assume a human voice.

Taittirlya Brahmana refers to Sarasvathi as speech manifested through the help of the vital breath Prana; and, indeed even superior to Prana –

- (vag vai sarasvatl tasmat prananam vag uttamam – Talttirlya Brahmana, 1.3.4.5).

The Tandya Brahmana identifies Sarasvathi with Vac, the speech in the form of sound (sabda or dhvani). Here, Sarasvathi is taken to be sabdatmika Vac, displaying the various form of speech (rupam) as also the object denoted by speech (vairupam): vag vai sarasvati, vag vairupam eva’smai taya yunakti – TB. 16. 5.16.

As said earlier; Sarasvathi along with Ila and Bharathi is identified with levels of speech (Vac). In these varied forms of identifications, Sarasvathi is the speech of the mid-position.

For instance; Sarasvathi is Madhyamika Vac (while Bharathi is Dyusthana Vac and Ila is Manushi Vac. Similarly, Sarasvathi is Madhyama Vac (while Bharathi is Pashyanti and Ila is Vaikhari). And again, Sarasvathi is said to represent the mid-region (while Ida the earth and Bharathi, the heaven).

By the time of the later Vedic texts, the identity of Vac with Sarasvathi becomes very well established. The terms such as ‘Sarasvathi –Vacham’, ‘Vac- Sarasvathi’ etc come into use in the Aharva-Veda. Even the ordinary speech was elevated to the status of Vac.

As the River

In the Aitareya Brahmana (3.37) Vac is directly identified with the life giving Sarasvathi (vag vai Sarasvathi). Even its location is mentioned. Vac is said to reside in the midst of Kuru-Panchalas – tasmad atro ‘ttari hi vag vadati kuru-panchalatra vvag dhy esa – SB. 3. 2.3.15.

The Vac-Sarasvathi in the form of river (Sarasvathi nadi rupe) is the generous (samrudhika) loving and life-giving auspicious (subhage) splendid Mother (Mataram sriyah), the purifying (pavaka) source of great delight (aahladakari) and happiness (sukhasya bhavayitri) which causes all the good things of life to flourish.

D. Sarasvathi as goddess in the later texts and traditions

Sarasvathi, in the post-Vedic period, was personified as the goddess of speech, learning and eloquence.

As the might of the river Sarasvathi tended to decline, its importance also lessened during the latter parts of the Vedas. Its virtues of glory, purity and importance gradually shifted to the next most important thing in their life – speech, excellence in use of words and its purity.

Then, the emphasis moved from the river to the Goddess. With the passage of time, Sarasvathi’s association with the river gradually diminished. The virtues of Vac and the Sarasvathi (the river) merged into the divinity – Sarasvathi; and, she was recognized and worshipped as goddess of purity, speech, learning, wisdom, culture, art, music and intellect.

Vac which was prominent in the Rig Veda, as also Sarasvathi the mighty river of the early Vedic times had almost completely disappeared from common references in the later periods.

Vac merged into Sarasvathi and became one of her synonyms as a goddess of speech or intellect or learning – as Vac, Vagdevi, and Vageshwari. And the other epithets of Vac, such as: Vachi (flow of speech), Veda-mata (mother of the Vedas), Vidya (the mother of all learning), Bhava (emotions) and Gandharva (guardian deity of musicians) – were all transferred to goddess Sarasvathi.

Similarly , the other Vedic goddesses – Ila, Bharathi, Gira, Vani , Girvani, Pusti, Brahmi – all merged into Sarasvathi, the personified goddess of speech ( vācaḥ sāma and vāco vratam) who enters into the inspired poets , musicians, artists and visionaries; and , gives expression and energy to those she loves (Kavi-jihva-gravasini)

Such epithets as Vagdevl (goddess of speech), Jihva-agravasini (dwelling in the front of the tongue), Kavi-jihvagra-vasini (she who dwells on the tongues of poets), Sabda-vasini (she who dwells in sound), Vagisa (presiding deity of speech), and Mahavani (possessing great speech)” often came to be used for Saraswati.

Amarakosha describes Sarasvathi the goddess of speech as

(1.6.352) brāhmī tu bhāratī bhāṣā gīrvāgvāṇī sarasvatī

(1.6.353) vyāhāra uktirlapitaṃ bhāṣitaṃ vacanaṃ vacaḥ

The Bhagavadgita (10.34) declares : Among the women , I am Fame, Fortune, Speech, Memory , Intelligence with Forbearance and Forgiveness : kīrtiḥ śrīr vāk ca nārīṇāḿ smṛtir medhā dhṛtiḥ kṣhamā

Sarsavathi also acquired other epithets based on the iconography related to her form: Sharada (the fair one); Veena-pani (holding the veena); Pusthaka-pani (holding a book); japa or akshamala-dharini (wearing rosary) etc.

E. Iconography

The iconography of goddess Sarasvathi that we are familiar with, of course, came into being during the later times; and, it was developed over a long period. There are varying iconographic accounts of the goddess Sarasvathi. The Puranas (e.g. Vishnudharmottara-purana, Agni-purana, Vayu-purana and Matsya-purana) ; the various texts of the Shilpa- shastra (e.g. Amshumadbedha, Shilpa-ratna, Rupamandana, Purva-karana, and Vastu-vidya-diparnava) and Tantric texts ( Sri Vidyavarana Tantra and Jayamata) each came up with their own variation of Sarasvathi , while retaining her most uniformly accepted features.

The variations were mainly with regard to the disposition, attributes and the Ayudhas (objects held) of the deity. The objects she holds, which are meant to delineate her nature and disposition, are truly numerous. These include : Veena; Tambura; book (pustaka); rosary (akshamala); water pot (kamandalu) ; pot fille with nectar (amrutha-maya-ghata); lotus flowers (padma); mirror (darpana); parrot (Shuka); bow ( dhanus); arrow ( bana ); spear (shula), mace (gadha), noose( pasha); discus (chakra); conch (shankha); goad (ankusha); bell (ghanta) and so on. Each of these Ayudhas carries its own symbolism; and, tries to bring forth an aspect of the deity. In a way of speaking, they are the symbols of a symbolism

In the case of Sarasvathi the book she holds in her hands symbolize the Vedas and learning; the Kamandalu (a water jug) symbolizes smruthi, vedanga and shastras; rosary symbolizes the cyclical nature of time; the musical instrument veena symbolizes music and her benevolent nature; the mirror signifies a clear mind and awareness; the Ankusha (goad) signifies exercising control over senses and baser instincts; and, the sceptre signifies her authority. The Shilpa-shastra employs these as symbols to expand, to depict and to interpret the nature of the idol, as also the values and virtues it represents.

There were also variations in the depictions of Sarasvathi:

- Complexion (white (sweta), red (raktha-varna) , blue (nila) – as Tantric deity and form of Tara);

- Number of eyes (two, three);

- Number of arms (four, six, eight);

- Posture (seated –Asana, standing – sthanaka; but never in reclining posture– shayana);

- Seated upon (white lotus, red lotus or throne)

- Wearing (white or red or other coloured garments);

- Ornaments (rich or modest) and so on.

Interestingly, the early texts do not mention her Vahana (mount). But the latter texts provide her with swan or peacock as her Vahana or as symbolic attributes (lanchana).

The Shilpa text Vastu-vidya-diparnava lists twelve forms of Sarasvathi ( Vac sarasvathi, Vidya sarasvathi, Kamala, Jaya, Vijaya, Sarangi, Tamburi, Naradi, Sarvamangala, Vidya-dhari, Sarva-vidya and Sharada) all having four arms , but without the Vahana. They all are looking bright, radiant (su-tejasa) and happy (suprasanna).

Another Shilpa text Jayamata enumerates a different set of twelve forms of Sarasvathi (Maha-vidya, Maha-vani, Bharathi, Sarasvathi, Aarya, Brahmi, Maha-dhenu, Veda-darbha, Isvari, Maha-Lakshmi, Maha-Kali, and Maha-sarasvathi).

The tantric text, Sri Vidyarnava-tantra, mentions at least three Tantric forms of Sarasvathi: Ghata-sarasvathi, Kini-Sarasvathi and Nila–sarasvathi (blue-complexion; three eyes; four arms, holding spear, sword, chopper and a bell).

And, there is also Matangi who is also called Tantric-Sarasvati; and, she is of tamasic nature and is related to magical powers. Her complexion too varies from white, black, brown, blue or to green depending on the context, She also has many variations, such as: Ucchista Matangini, Ucchista-Chandalini, Raja Matangini, Sumukhi Matangini, Vasya Matangini or Karna Matangini.

Bhuvanesvari, one of the ten Mahavidyas, is also linked to speech (vak); and, therefore, she is said to correspond to Sarasvathi, Vagesvari.

Tara, in Buddhism, of blue complexion, associated with the speaking prowess, and seated on a lotus is called Nila (blue) Sarasvathi

The Vajrayana Buddhism too has its own set of Tantric Sarsavathi-s, like the six armed Vajra-Sarasvathi; the Vajra-sharada holding a book and a lotus in her two hands; and, Vajra-veena-sarasvathi playing on a veena. The other deities like Prajna-paramita and Manjushree have in them some aspects of the Sarasvathi.

TheJain tradition has Sarasvathi in the form of Shruta-devata; Prajnapti; Manasi and Maha-Manasi. The Shrutadevata is the personified knowledge embodied in of sacred Jain scriptures preached by the Jinas and the Kevalins (Vyakhya-Prajnapti-11.11.430 and Paumachariya-3.59). Sarasvati is invoked for dispelling the darkness of ignorance, for removing the infatuation caused by the jnanavarniya karma (i.e. the karma matter enveloping right knowledge) ; and, also for destroying miseries.

The early Jain works conceive Sarasvati only with two hands and as holding either a book and a lotus or a water-vessel and a rosary, and riding a swan. The Sarasvati-yantra-puja of Shubhachandra, however describes the two armed mayura-vahini with three eyes,holding a rosary and a book.

The four armed Sarasvati appears to have enjoyed the highest veneration among both the Svetambara and the Digambara sects. The four-armed goddess in both the sects bears almost identical attributes, except for the vahana. The vahana of Sarasvati in the Svetambara tradition is swan, while in Digambara tradition she rides a peacock.

[ Dr. Maruti Nandan Pd. Tiwari, Emeritus Professor History of Art, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, writes :

The popularity of worship of Sarasvati in Jainism is established on the testimony of literary references in the Vyakhya-prajnapti (c. 2nd-3rd century A.D.), the Paksika-sutra of Shivasharma (c. 5th century A.D.), the Dvadasharanya-chakravritti of Simha suri Kshamashramana (c. CE 675), the Panchashaka of Haribhardra suri (c. CE 775), the Samsaradavanala-stotra (also of Haribhadra suri), the Mahanishitha-sutra ( c. 9th century A.D.) and the Sharada-stotra of Bhappabhatti suri (c. 3rd quarter of the 8th century A.D.) and also by the archaeological evidence of the famous image of Sarasvati from Mathura belonging to the Kushana period (CE 132)

The popularity of her worship can also be understood from the large number of Sarasvati figures placed at different parts of Jain temples particularly in western India. A special festival held in the honor of Sarasvati is called Jnana-panchami in the Svetambara tradition and Shruta-panchami in the Digambara tradition.5 Besides this festival, special penance like the Shrutadevata-tapas and Shruta-skandha and Shrutajnana-vratas are also observed by the Jains.]

Sarasvathi, as Vagdevi, is depicted as gesturing scriptural knowledge with her right hand in Vyakahana-mudra; and, gesturing protection and assurance with her left hand in Abhaya-mudra. At times, she is shown with three eyes. She is decorated by a crown (makuta) with a crescent moon; and with a sacred thread across her chest (yajnopavitha).

The Vishnudharmottara (Ch.3. 64. 1-3) states that the images of Goddess Sarasvathi should be adorned with all ornaments. She should be depicted as standing; and should be made four-armed, holding in her right hands a book and a rosary (Aksha-mala) ; and, in the left hands Vina or Vaishnavi-shakthi and Kamandalu.

The four Vedas are her arms; all powerful weapons are in the book she holds; the Kamandalu she holds is the elixir, the essence of all the Shastras; the Aksha-mala is the cycle of time.

Her face should be radiant as the moon in full glory. Her eyes beautiful like the fresh lotus , represent the sun and the moon.

And, when he is depicted as standing, she should assume sama-paada position; and, her face should be pleasing and radiant, like the moon of Sharad-ritu (Sarat-chandra-vadana).

***

Devi Sarasvathi Karyo Sarva-abhara-bhushita / Chatur-bhuja sa karthavya tatthaiva cha samusthita /3.64.1/

Pusthakam Aksha -malam cha tasya dakshina-hastha yoh/ Vamayos cha tattha karya Vaishanavi cha kamandaluh /3.64.2/

Sama=pada-prathista cha karya Soma-mukhi tattha / Vedas-tasya Bhuja jneyah sarva-shastrani pusthakam /3/ 64.3/

Sarva -shastra-amrutha -raso devya jneyah kamandaluh / Aksha-mala kare tasya kalo bhavathi parthiva /3.61.4/

Siddha -murthi-mathi jneya Vaishnavi na tre samshayah / Savitri-vadanam tasyah sarvadya pari-keertita /3.64.5/

Chandra-arka-lochana jneya sa cha Rajiva-lochana /3.64.6/

Sarasvatham te kathitam maye tad-rupam pavitram paramam Moksham / Dhyeyam cha karyam cha Mahipa-mukhya , Sarvartha -siddhim sama -beepsa-manyai /3.64.7/

*

The Sarasvathi that is commonly depicted is an extraordinarily beautiful, graceful and benevolent deity of white complexion, wearing white garments, seated upon a white lotus (sweta-padmasina) , adorned with pearl ornaments ; and holding in her four hands a book, rosary , water-pot and lotus .

Her Dhyana –sloka reads:

Yaa Kundendu tushaara haara dhavalaa, Yaa shubhra vastranvita.

Yaa veena vara dandamanditakara, Yaa shwetha padmaasana

Yaa brahma achyutha shankara prabhutibhir Devaisadaa Vanditha

Saa Maam Paatu Saraswatee Bhagavatee Nihshesha jaadyaapahaa

Salutations to Bhagavathi Sarasvathi, the one who is fair like garland of fresh Kunda flowers and snowflakes; who is adorned with white attire; whose hand is placed on the stem of the Veena; who sits on white lotus; one who has always been worshiped by gods like Brahma, Vishnu and Shankar; May that goddess Sarasvathi bless us, protect us, and completely remove from us all stains of lethargy, sluggishness, and ignorance.

Continued in the Next Part

Sources and References

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/57870/2/02_abstract.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/69217/7/07_chapter%201.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/57870/7/07_chapter%202.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/66674/10/10_chapter%203.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/57870/10/10_chapter%205.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/116523/13/13_chapter%205.pdf

- http://www.svabhinava.org/hinducivilization/AlfredCollins/RigVedaCulture_ch07.pdf

- http://www.vedavid.org/diss/dissnew4.html#168

- http://www.vedavid.org/diss/dissnew5.html#246

- Ritam “The Word in the Rig-Veda and in Sri Aurobindo’s epic poem Savitri

- http://incarnateword.in/sabcl/10/saraswati-and-her-consorts#p17-p18

- 12. Vedic river and Hindu civilization; edited by Dr. S. Kalyanaraman

- Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India… Edited by John Muir

- Devata Rupa-Mala (Part Two) by Prof. SK Ramachandra Rao

- http://www.ancientvedas.com/

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/40874433?reanow=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A728e60fe40da00b76f29f7525a60268a&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

ALL IMAGES ARE TAKEN FROM INTERNET