Vaikhanasa

43.1. Among the Vaishnava Agamas that glorify Vishnu as the Supreme Principle, and as the Ultimate Reality, to the exclusion of other deities, the Vaikhanasa and Pancharatra are prominent. Some say, Vaikhanasa is the older tradition that is rooted in the orthodoxy of the Vedic knowledge. The Pancharatra, in contrast, is regarded relatively less conservative, a bit more liberal and closer to the Tantra ideology.

There are several explanations to the term Vaikhanasa.

Vanaprastha

44.1. According to one interpretation, Vaikhanasa is the ancient word for Vanaprastha (life of a forest dweller or hermit). Vanaprastha, according to the scheme of man’s lifespan as developed during the later Vedic age*, is the third stage (ashrama) in a man’s life. It is the stage prior to and in preparation for Sanyasa the last stage of total withdrawal from the world.

Although Vaikhanasa-s are not directly mentioned in the Rig-Veda, there are references to them in the Anukramani Index to RV hymn at 9.66 , which is addressed to ‘Indra, Pavamana and one hundred Vaikhanasa’ ( RV_9,066.23.2 indur atyo vicakṣaṇaḥ). And, the RV hymn 10. 99 is addressed by Indra to ‘Vamra Vaikhanasa.

There are also reference to Vamra Vaikhanasa in Jaiminiya Brahmana at 3.99 and 3.215, which say that : Puruhanma Angirasa , Rishi of Hymn 8.1 of the Rigveda, ( पुरुहन्मा आङ्गिरसः) Vaikhanasas loved animals , underwent austerity . He Visualized the Jagata saman (hymn)

– (Vaikhanasam bhavathi jagatam sama) ; and , (Vaikhanasa va etani samany apasyan)

Here , Vaikhanasa hermits are said to be dear to Indra – indrasya priyā āsaṃ. Vaikhanasa quote extensively from Rig-Veda, in which Indra is the principal deity. In the later times, Indra merged with Vishnu.

There are several references to Vaikhanasa-s in the Ramayana. At end of the Ayodhya-kanda , -while they were departing to the forest clad in bark–garments , it is said, the brothers Rama and Lakshmana adopted the ways of the hermits and vow of ascetic life (Vaikhanasam margam)

– Rama –rakshamanau tato Vaikhanasam margam asthitah saha Lakshmanah –R. 2.57-58.

Later in the Ayodhya-kanda, the ways of living of the Vikhanasa hermits are described in detail. And again, in the Khishkinda–kanda there is a reference to the ascetic groups of Vaikhanasa-s and the Valakhilya-s

-Tatra Vaikhanasa Nama Valakhilya maha-rishayah-R.4.40.60

In all these references, the Vaikhanasa-s are described as forest-dwellers, ascetics following a pristine way of life dedicated to Indra/Vishnu/

The Varnashrama system expanded by Dharmashastras, mentions that after fulfilling his family responsibilities and social obligations, say at the age of sixty or thereafter; and at the end of his well-lived family-life , a man retires into forest , along with his wife (sa-pathnika), to lead a peaceful and contemplative life of a recluse , away from the worldly conflicts and its snares. The two live like trusted old friends; and, lead a happy, contented and tranquil life. It is the fulfillment of the long journey they travelled together. As his sense of detachment ripens, the man finally accepts sanyasa; and, the wife returns home, to the family of her sons.

44.2. Vanaprastha, in its concept, is not an end by itself; but is deemed as a step to reach man’s highest aspiration, the liberation. The characteristic of its ascetic mode of life is detachment and contemplation. Yet; it is the stage of life marked by selfless friendship, open-heartedness, mellow glowing wisdom and compassion towards all, including strangers , animals and plants. It is the maturity of life when positive attitudes and social virtues ripen.

Vanaprastha is not distracted by motives of personal gain (artha) or desire for pleasures (Kama). But, he does not lead a harsh and an arid life of self-mortification. That is because; he views the body and spirit as equal expressions of the divine. Vanaprastha stage is conceived as a well balanced rounding off to a worthy life.

[* Prof. PV Kane in his monumental History of Dharmashastras (pages 417– 419) explains the concept of ashramas (in the sense of different stages in man’s life) is not found either in the Samhitas or in the Brahmanas. According to him, a germ of the idea occurs in an obscure form in Aittereya Brahmana (Ait. Br. 33. 11), which decries a person who moves away from life and the world:

‘what (use is there) of dirt (malam) , what use of antelope skin (ajinam), what use of (growing) the beard (imasruni), what is the use of tapas? O! Brahmanas ! Desire a son; he is a world that is to be highly praised.’

nu malam kin ajinam kimu imaśrüni kim tapah/ putram brahmāna icchadhvam sa vai loko vadāvadah

The idea appears again in Chhandogya Upanishad (Ch. Up. 2. 23. 1), where it is characterized by the practice of asceticism (Tapas). A Vanaparasta is regarded as a Tapasvin.

And it comes out a little more clearly in Jabalopanisad and in Svetasvataropanisad (VI. 21) which speaks of those ‘who had risen above the mere observances of asramas’; by virtue of whose Tapas are blessed by gods ; and, attained the most sacred stage in man’s life – atyā-śramibhyaḥ paramaṃ pavitraṃ .

tapaḥ-prabhāvād devaprasādācca / brahma ha śvetāśvataro’tha vidvān।atyāśramibhyaḥ paramaṃ pavitraṃ / provāca samyagṛṣisaṅghajuṣṭam ॥ śvetāśvataropaniṣat–21॥

The concept of man’s life span spread over a well-knit scheme of four stages (ashramas) was fully developed in Dharmashastras of Manu (Manu 6. 1-2; 33 etc). And, Manu remarks that a Vanaprasta should continually increase the rigor of his Tapas.

The theory of Ashramas was truly an idealist concept. However, owing to the exigencies of the times; the conflicts of interests ; and, the distractions of life, the scheme could not, even in ancient times, be carried out fully by most individuals. And , it surely has failed in modern times, though the fault does not lie either with the concept or with its originators . ]

44.3. The later texts and Puranas elaborated on the scheme and devised sub-classifications under each stage (ashrama). For instance, Srimad Bhagavata (15.4) classifies the third stage – Vanaprastha – into four types Vaikhanasa; Valakhilya; Audumbara; and Phena.

Vaikhanasa valakhilyau-dumbarah phenapa vane Nyase kuticakah purvam bahvodo hamsa-niskriyau II

44.4. Following that sub classification, the Gaudiya-Kanthahara, a twentieth century text ascribed to Atulakrsna Datta of Gaudiya Vaishnavas tradition explains Vaikhanasas as those hermits (Vanaprastha) who retire from active life and live on half-boiled food (ardha-pakva-vratya).

Similarly :

Valakhilya is one who discards the stock of food he has with him (purva ancita anna tyagah) the moment he gets a fresh stock of food (nave pane labdhya);

Audumbara is one who lives on what he gets from the direction towards which he walks (prathamam disam pasyanti) after sunrise (prathar uttha); and,

Phenapa lives on fruits (phaladbhir jivantah) that drop from the trees on their own accord (svayam patitaih).

44.5. However, what is interesting is that Vaikhanasa-smarta-sutra, a division of the primary text of Vaikhanasas (Vaikhanasa Kalpa Sutra) does not mention a category of hermits called as Vaikhanasa.

Apparently, the perceptions on the stages of man’s life had undergone a huge change between the period of Kalpa Sutras and the period of the later Puranas.

[Incidentally, Vaikhanasa is also the name of mythical group of saintly hermits who were slain at Muni-marana (death of sages) by one Rahasyu Deva-malimlud (Panchvimshathi Brahmana: 14.4.7).

vaikhānasā vā ṛṣaya indrasya priyā āsaṃs tān rahasyur devamalimluḍ munimaraṇe ‘mārayat taṃ devā abruvan kva tarṣayo (?) ‘bhūvānn iti tān praiṣam aicchat tān nāvindat sa imān lokān ekadhāreṇāpunāt tān munimaraṇe ‘vindat tān etena sāmnā samairayat tad vāva sa tarhy akāmayata kāmasani sāma vaikhānasaṃ kāmam evaitenāvarundhe stomaḥ- P.Br.14.4.6]

**

45.1. As regards the question of equating Vaikhanasa directly with Vanaprastha stage of life, Professor PV Kane clarifies; there is nothing in the Vedic literature expressly corresponding to the Vanaprastha. And the germ of the idea of equating Vanaprastha with Vaikhanasa might have arisen at a later stage in the Sutras.

45.2. Max Muller in his commentary on the Laws of Manu mentions that Manu (4.21) refers to the Sutra of Gautama which talks of the hermit in the forest who ‘may subsist on flowers, roots, and fruits alone’. Max Muller, however, asserts that it may not be correct to simply straightaway translate hermit as Vaikhanasa, because the term Vaikhanasa doesn’t merely mean a hermit.

Vaikhanasa here has to be understood, he says, as referring to only those hermits who are ‘abiding by the Vaikhanasa opinion’ (vaikhanasamate sthithah).

And he explains: ‘here the term Vaikhanasa denotes a shastra or a sutra promulgated by Vaikhanasa, in which the duties of hermits are described in detail’. He reminds: Manu’s discussion on Vanaprastha also mentions a Vaikhanasa –rule (Manava Dharmashastra: 6.21).

45.3. In support of his argument, Max Muller cites Haradatta the commentator of Apastambha and Gautama (3.2) who opines: ‘the Vanaprastha is called Vaikhanasa because he lives according to rules (sutra) formed and taught by Vaikhanasa’.

He also mentions of Kullaka Bhatta (6.21), another commentator of Manu, who says that Vaikhanasa were a distinct group who were rooted in their own doctrine-

– Vaikhanaso vanaprasthah taddarma – pratipadaka –shastra – darshane – sthitah

Tandya Mahabrahmana (14. 4. 7) says: ‘Vaikhanasa sages were the favorites of Indra (vaikhanasa vaa rushyah Indrasya priya aasan).

45.4. Max Muller states that Baudayana does refer to a Vaikhanasa sutra and gives a short summary of its content in the third chapter of the third prashna of his Dharmashastra. He describes Vaikhanasas as a group that abides Vedic authority –

– śāstra.parigrahaḥ sarveṣāṃ brahma.vaikhānasānām: Baudayana Dharmasutra: 3.3.17-18

Baudayana also describes the forest dwelling hermits as those who devotedly tend sramanakagni –

–vaikhānaso vane mūla.phala.āśī tapaḥ.śīlaḥ savaneṣu udakamupaspṛśan śrāmaṇakena agnim ādhāya^agrāmya – Baudh 2.6.11.15

Sramana

46.1. It needs to be mentioned ; a distinguishing feature of Vaikhanasa, as given in the early texts , is their pre-occupation with tending a sacrificial fire known as sramanaka-agni (instead of tretagni which is usually tended by householders). It appears, sramanaka-agni was no ordinary fire. But, it was the fire born out of Vedic rituals; and was one with the worshipper (Agnim apy atma-sat krtva).

46.2. The term Sramana, in the ancient context, referred to a mendicant who leads a life of restraint and discipline (tapo-yoga); but continues to be in Vedic fold tending sacrificial fires with a sense of duty and not by desire to gain material rewards. And, the terms Sramana and Sramanaka came to be equated with Vaikhanasa and their scriptures.

46.3. Haradatta, the ancient commentator also talks about kindling the sramanaka-agni (sramanakena agnim adhya); and says it followed the doctrine of the Vaikhanasas (vaikhanasam shastram sramanakam ).

The Sramanaka method of invoking sramanaka-agni perhaps involved icon – worship along with the usual fire rituals. That perhaps distinguished the Vaikhanasas from the other hermit (Vanaprastha) groups.

[Some say; the Vaikhanasa (Sramanaka) prescription of the abstract worship of one fire (ekagni) perhaps led to the doctrine of ekayana; and to the formation of ekantinah group (or Bhagavatas).]

Disciples of Sage Vaikhana

47.1. It is said; Vaikhanasa is the name of a community as also the name of the philosophy they follow. It is also said; Vaikhanasa community derived its name from its founder (a manifestation of Brahma or Vishnu): sage Vaikhanasa of Angirasa gotra, affiliated to Krishna-Yajurveda -shakha. He is credited with organizing worship of Vishnu in image form (samurtha-archana), which, in effect , was the transformation of the Vedic mode of worship through ‘shapeless’(amurtha) ritual-fire .

The feature of his teaching, while it is rooted in the pristine Vedic tradition, is that it extolled a strong devotion towards Vishnu and worship of Vishnu icon.

Vaikhanasa, perhaps, was amongst the earliest Vaishnavas mentioned in the Narayaniya section of Mahabharata. They are described as peaceful, benign (soumya), self possessed, (bhavitathmanam), highly evolved (utcchyante) and satttvic in their food- habits (Mbh. Shanthi parva).

[An interesting interpretation of the term Vaikhanasa is derived from the root khanana meaning ‘digging into’. According to Ananda –samhita ( ascribed to Marichi ) the task of : ’digging into or deeply inquiring into the meaning of the Vedas and related texts , for the benefit of all mankind ‘ was accomplished by the founder sage of this spiritual heritage (parampara ); and , therefore he was aptly addressed as Vaikhana:

-Khananam –tattva -mimamsa – nigama-arthanam khananad iti nah srutam.]

47.2. Thus, the term Vaikhanasa includes in itself several shades of meaning: the forest-dwelling hermit in the third stage of his life; a great sage who was the founder of Vaikhanasa tradition, an incarnate Brahma or Vishnu; and, the set of the sutras named after him. Perhaps the earliest hermits following this tradition were all of these.

But, in the later stages, the followers of the tradition identified and distinguished themselves as disciples of Vaikhana the adept in Vishnu-worship (Vishnu-puja-visharada) and those guided by the instructions of Vaikhanasa-kalpa- sutra, which in all its aspects is devoted to Vishnu.

Principles of Vaikhanasa tradition

48.1. The Vaikhanasas are distinguished by their uncompromising devotion to Vishnu as the Vedic God par excellence; and, are rooted in the faith that Vishnu who pervades all existence (vyapanath Vishnuh) alone is worthy of worship. The early Vaikhanasas retained Vishnu in his pristine Vedic context; and preferred the expression ‘Vishnu’ over ‘Narayana’ or ‘Vasudeva’ (although they are synonyms), because Vishnu is the one that occurs in the Vedas. They steadfastly held on to the Vedic image of Vishnu; and, also clung to the Vedic orthodoxy. They remained faithful to Vedic principles and traditions. And, proudly asserted that they are the surviving school of Vedic ritual propagated by the sage Vaikhana; and above all, they are the children of Vishnu.

48.2. The Vaikhanasa tradition asserts that it is the most ancient; and traces its origin to Vedas. Vishnu, they declare, who is the Supreme god adored by the Vaikhanasas is not only a Vedic god, but is also the very personification of Yajna (Yajna-purusha). Their principal text calls upon its followers:

that after the customary offerings made to Agni, Vishnu must be worshipped morning and evening, for that means the worship of all gods (Girhya – smarta- sutra: parshna 4, khanda 10).

That is because; all gods reside in Vishnu.

49.1. The teachings of sage Vaikhana provide for worship of the Supreme Being having attributes (sa-kala) and also for worship of the one without attributes (nis-kala); with form (samurtha) and without form (amurtha).

The Yajna, the worship of the divine through fire, is a-murta; while the worship offered to an icon is sa-murta. According to Vaikhanasas, though yajna might be more awe-inspiring; however, Archa (worship or puja) the direct communion with your chosen deity is more appealing to ones heart, is more colorful and is aesthetically more satisfying. Further, in the Yagna one participates as a member of group of Ritviks; it is virtually a team effort. But, Archa is the intimate relation that the devotee tries to bind with love and devotion towards her/his most revered and dearest deity.

As regards the term formless (nis-kala), it is explained, suggests a state of pure-blissful- existence (satchidananda rupi), beyond the intellect (achintya) and wondrously lustrous (tejomaya) that abides in one’s heart lotus (hrudaya pundarika).

Sakala, on the other hand, is when the Godhead is visualized as an icon, a human form with distinct features, seated in a solar orb (arka-mandala) or in sacred- water pot (jala-kumbha) or as worship worthy icon (archa-bera).

The Vishnu’s Sakala form for contemplation (dhyana) and worship (pranamet) is four-armed (chaturbhuja) holding four ayudhas : conch, disc, mace and lotus (shanka, chakra, gadha and padma); beaming with blissful countenance dear to look at (saumyat –priya – darshanh) ; having rosy pink complexion (shyamala) ; and, wearing yellow silk garments (pitambara).

Along with icon form of Vishnu, the text suggests techniques for visualizing contemplating and worshipping the most adorable form of Vishnu. It also elaborates on four aspects of Vishnu as: Purusha, Satya, Acchuyta, and Aniruddha.

49.2. Vaikhanasa view point is that icon-worship was an integral part of Vedic culture; and it was not a later innovation. It says; Godhead is described by the performers of Vedic Yajnas as Yajna-Purusha; and as Vishnu by those who know the final import of the Vedas (Vedantins). Vaikhanasa regard themselves as those who moved from the first stage of Vedas to its final import (Vedanta); and therefore are the Vedantins. The ancient smriti- kara Bahudayana (Dharma – sutra: 3.3.17) calls Vaikhanasas as a group that abides Vedic authority (shastra parigrahas sarvesham vaikhanasam).

49.3. Vaikhanasas assert, their method of worship is indeed truly Vedic. It was explained; when Bhagavata-purana (11.27.7) speaks of three varieties of worship (tri-vidho-makhahah) : vaidika, tantrika and misra (mixed), the vaidika refers to the Vaikhanasa mode of worship.

49.4. Further, the Agamas are regarded as Vaidika, because they accept the ultimate authority of the Vedas and employ Vedic mantras in all types of rituals. The worship practices at home as described by the Vaikhanasa –Grihya-sutra closely follow the vidhi-s prescribed in Bodhayana–Grihya–sutra, Apastamba sutra, and Atharvaveda- parishistha. They are also said to resemble mantra prashnas of Taittariyakas and Brahmana of Sama-vedins. And, these perhaps represented the earliest surviving textual references on icon-worship.

50.1. The householder was required to perform regularly a group of five sacrifices (pancha-maha-yajna). These were the sacrifices rendered to gods (deva); the ancestors (pitr); animals, birds and elements (bhuta); fellow beings (manushya); and, Veda- study (Brahma). These were, however, not Yajnas proper, But, were meant as means for developing the sense of detachment and compassion towards all .

50.2. Sage Vaikhana observed that ‘Vishnu is the very essence of existence (sat), consciousness (chit) and bliss (ananda); and, he can be attained either by Yajnas or by icon-worship. If one does not perform Yajnas then one must contemplate on Vishnu who is the very personification of Yajna. And, one must worship Vishnu, the Supreme god, constantly with devotion, in his home or in a temple. That will surely lead to the highest realm of Vishnu’ (Vaikhanasa – grihya –sutra: 4.12.8-11).

50.3. Following that, the concept of Yajna was re-defined. The Yajnas and icon worship were regarded as complimentary; and the icon worship was not viewed as distinct from or contrary to Vedic rituals. It was explained that Yajna which involves offering through Agni is, in fact, the worship of formless God (amurtha-archana). But, Yajna is by itself Vishnu (yajno vai Visnhuh).

In converse, it meant that worship of Vishnu icon was also a Yajna (samurtha-bhagavad-yajna), which in turn was the worship of all gods (sangathi deva- pujanam yajnah).

The two forms of worship are not essentially different. Therefore, the rewards of the Yajna are also obtained by worshipping and meditating upon the icon of Vishnu (murtha-archana).

It was also explained that worship of Vishnu is in effect the worship of all gods as the whole existence resides in him –

vishnau-nitya-archa sarva deva-archa bhavathi: Vaikhanasa – grihya –sutra: 4.10.1.’

( It would be interesting to glance here at the Four Verses of the Sri Bhagavata Purana

चतु:श्लोकी भगवतम् – (श्रीमद भागवत महापुराण २। ९। ३२–३५ )

अहमेवासमेवाग्रे नान्यद् यत् सदसत् परम्। पश्चादहं यदेतच्च योऽवशिष्येत सोऽस्म्यहम् ॥(१)

ऋतेऽर्थं यत् प्रतीयेत न प्रतीयेत चात्मनि। तद्विद्यादात्मनो मायां यथाऽऽभासो यथा तमः ॥(२)

यथा महान्ति भूतानि भूतेषूच्चावचेष्वनु। प्रविष्टान्यप्रविष्टानि तथा तेषु न तेष्वहम्॥(३)

एतावदेव जिज्ञास्यं तत्त्वजिज्ञासुनाऽऽत्मनः। अन्वयव्यतिरेकाभ्यां यत् स्यात् सर्वत्र सर्वदा॥(४)

**

Ahamēvāsamēvāgrē nān’yadyatsadasatparam. Paścādahaṁ yadētacca yō̕vaśiṣyēta sō̕smyaham.

R̥tē̕rthaṁ yatpratīyēta na pratīyēta cātmani. Tadvidyādātmanō māyāṁ yathā̕bhāsō yathātama

Yathāmahānti bhūtāni bhūtēṣūccāvacēṣṇu. Praviṣṭyapraviṣṭāni tēṣu na tēṣvaham

Ētāvadēva jijñāsyaṁ tattvajijñāsunātmana. Anvayatirēkabhyāṁ yatstsarvatra sarvadā

*

- O Brahma! I was existing before creation, when there was nothing but Myself. There was no material nature, the cause of this creation. That which you see now is also I; and , after annihilation what remains will also be I.

- O Brahma! That which appears to be of value, but has no relation to Me, has no reality. Know that it is My energy, a reflection, which appears in darkness.

- O Brahma! Please know that the universal elements enter into the cosmos; similarly, I Myself exist within everything created, and at the same time I am outside of everything.

- A person searching after the Supreme Absolute Truth, must certainly search in all circumstances, in all space and time; directly and indirectly; internally and externally.

***

All these four verses are collectively called as Chatur Slokas, the four verses that summarize the entire teachings of Bhagavata Purana. They are said to be the most sublime teachings leading the way towards The Supreme.

**

एतन्मतं समातिष्ठ परमेण समाधिना । भवान् कल्पविकल्पेषु न विमुज्झति कर्हिचित् ।।।

ज्ञानं परमगुहां मे यद्विज्ञानसमन्वितम् । सरहस्यं तदंगं च ग्रहाण गदितं मया ।।1।। यावानहं यथाभावो यद्रूपगुणकर्मक: । तथैव तत्त्वविज्ञानमस्तु ते मदनुग्रहात् ।।2।।

50.4. The Vaikhanasa teachings provide both for worship of the form-less (amurtha-archana) through performance of yajnas and for worship of Vishnu through his image, with equal dedication and devotion. This dual spiritual heritage, blended harmoniously, underline the twofold character of Vaikhanasa worship -tradition (archana- sampradaya).

51.1. The characteristic of Vaikhanasa view point is that the path way to final emancipation is not devotion alone, but worship of icon (samurtha-archana) performed with devotion (bhakthi) and sense of absolute surrender (prapatthi). It says, devotion may at times be a passing mood, but worship-sequences (kriya-yoga, upasana) rendered with utmost diligence when combined with devotion leads to fulfilment of human aspirations.

A sense of devotion envelops the mind and heart when the icon that is properly installed and consecrated is worshipped with love and reverence. By constant attention to the icon, by seeing it again and again and by offering it various services of devotional worship, the icon is invested with divine presence and its worship ensures our good here (aihika) and also our ultimate good or emancipation (amusmika).

And therefore, ‘archa with devotion is the best form of worship, because the icon that is beautiful will engage the mind and delight the heart of the worshipper’. That would easily evoke feeling of loving devotion (bhakthi) in the heart of the worshipper. The icon is no longer just a symbol; the icon is a true divine manifestation enliven by loving worship, devotion, and absolute surrender (parathion). And, Vishnu is best approached by this means.

The very act of worship (archa) is deemed dear to Vishnu. It points out that such upanasa is the same as Vedic Yajna; nay but is superior to Yajna Worship (bhavad-samutha-archana) is indeed more effective and purposeful than mere knowing scriptures.

The major thrust of Vaikhanasa texts is to provide clear, comprehensive and detailed guidelines for Vishnu worship. The Vaikhanasa texts are characterized by their attention to details of worship-sequences. It is not therefore surprising that Vaikhanasas describe their text as ‘Bhagava archa-shastra’.

51.2. The icon worship (archana) is held by Vaikhanasas as being superior to all other modes of worship because it includes in itself the special attitude of devotion (bhakthi), the offerings (huta) to god, recitation of mantras, repetitions of the sacred mantra (japa) and meditation upon the glory of god (dhyana).

The Vaikhanasa texts hold the view that icon-worship is best suited for the present age of Kali. The well made icon of Vishnu pleases the eyes; delights the heart; engages the mind; fills the worshiper with loving devotion; and, blesses with a great sense of joy and fulfillment.

That is the reason the texts advise that icon worship must be resorted to by all, especially by those involved in the transactional world. In these texts, the Nishkala aspect continues to be projected as the ultimate, even as they emphasize the relevance and importance of the sakala aspect. The devotee must progressively move from gross sthula to the subtle sukshma.

51.3. Yes; Vaikhanasas valued icon worship very highly; but, at the same time they did not give up performance of Yajnas altogether. They learnt to combine the two streams of worship harmoniously. The Vaikhanasa tradition represents the passing stage of transformation from pure Vedic Yajna-Yagas to their combination with icon-worship.

[To Sum up : Though the Vaikhanasa Agamas give primary importance to Arca or Murti-puja; i.e., offering worship to the images of gods, their consorts and attendant deities; their outlook is, in essence, idealistic. It is rooted in the faith that Godhead is Sarvadhara (support of all of this existence); Sanatana (timeless and eternal); Aprameya (without a comparison); Acintya (indefinable); Nirguna (without attributes) ; and, Niskala (without parts). It is all-pervading; even as butter in milk; oil in oil-seeds or fire in firewood. However, even as fire blazes forth by friction of the Arani sticks, Vishnu appears in the heart of the devotee by dhyana-mathana (churning due to meditation) or constant meditation.

This is the ‘Sakala‘ form; the Absolute materializing itself due to the devotion and visualization of the devotee. Even then, worshiping an icon, properly prepared; and, as per the rules (Vidhi) prescribed in the Vaikhanasa Agama treatises, is extremely important. That itself can, ultimately, lead to salvation (Moksha). This seems to be the sine qua non of the Vaikhanasa Agamas.]

Antiquity

52.1. The Vaikhanasas as a group of religious practitioners are of great antiquity. It is likely they were a separate forest dweller community that existed some time before the beginning of the Common Era. According to Max Muller, ‘the ancient Vaikhanasa Sutra which is an important portion of the sacred law preceded Manu Smriti’.

52.2. Max Muller opines that the work of Vaikhanasa must be extremely ancient. And, it is not advisable to assume that it had any connection with Vaikhanasa sutrakarana a sub division of the Taittiriyas which is one of the youngest schools adhering to Krishna Yajur Veda.

52.3. Dr. Nagendra Kumar Singh in his Encyclopaedia of oriental philosophy and religion (page 891) observes: it is likely that the Vaikhanasa literature documents the community’s transition from a Vedic School of ritual observance to a School of those engaged in religious performances; and particularly in devotional worship of Vishnu-icon (archana).

53.1. The scholars cite many internal evidences that go to suggest the antiquity of the Vaikhanasa tradition. It is said; the Vaikhanasa worship practices carried out within the inner and surrounding shrines mention only five avatars of Vishnu: Kapila, Varaha, Nrsimha, Vamana/Trivikrama and Hayashirsha (Hayatmaka).

There is no mention of the ten Avatars (dashavatara-s) in the core Vaikhanasa texts. Perhaps, the concept of dashavataras was then yet to be developed, evolved and elaborated.

53.2. Atma Sukta hymn is unique to the Vaikhanasa mode of worship. It seeks to evoke in the worshipper his identity with Vishnu in his cosmic form as Purusha. It’s composition having a typical mix of Vedic and classic features suggest that it dates back to the late Vedic era; and, is definitely older than the Puranas.

This hymn mentions only three Avatars explicitly: Varaha, Kapila and Hayashirsha.

It identifies the Varaha the boar that blesses (varado) with the upward breath (udana); Sage Kapila the personification of penance (tapasam ch murthim) with the spreading breath (vyana); and the horse-headed Hayashirsha with the downward breath (apana).

53.3. Similarly, there is no mention of Vibhavas or Avatars such as Vasudeva and his Vyuha (group) of Vrishni clan of Sankarshana, Pradyumna, Aniruddha et al, as in the Pancharatra tradition .This again suggests that Vaikhanasa is older than the Pancharatra, perhaps on account of its Vedic associations.

54.1. Further, the association of Kumara and Kaumara – mantra with Vaikhanasa tradition is also interesting.

The Kaumara – mantra: Om aghoraya mahaghoraya nejameshaya namo namah (as provided in Vaikhanasa –samhita, mantra –prashna: 5.49) is said to represent the earliest form of the tantric school Kaula –vidya.

It is also said; Vaikhanasa were the earliest to adopt the tantra technique of worshipping Vishnu icons.

54.2. We find that the later Vaikhanasa Grihya sutra include practices of praying to Guha or Kumara while conducting certain life-cycle–rituals (samskaras) of the child .

For instance; the Vaikhanasas invoke ‘Guha’ , Kumara for blessing the infant during its namakarana ceremony (naming the infant) – bhushane–-Shanmukham Aavahayami. The newborn is blessed with mantra: ‘be invincible (sarvatra-jayo bhava) like Kumara, son of Shankara’

(Shankarir iva sarvatra-jayo bhava: Vaikhanasa smarta sutra 3.19.20).

Invocations are also made to protect the child from Kumara-grahas, the spirits that seize the children below the age of five.

Kumara is also invoked while the Vaikhanasa – child is taken to Kumara temple for its first outing – Pravasagamana. The father takes the prasada, the flowers that adorned Kumara, and places it on the child’s head saying: ‘I give you the flowers with which the Gurus worshiped Kumara (sesham gurubhih supujitam pushpam); may you be protected-

-Guhasya sesham gurubhih supujitam pushpam dadami-sya Shammukham.

After the above Samskaram; it is indicated that a ritual food sharing is arranged; where, the Vaikhanasas will partake the meal along with other Vaikhanasas . Such ‘kumara bhojanam‘ is also performed during Upanayanam of the boy.

54.3. Interestingly, the ashtottara-shata-namavali of Sri Venkateshvara, calls the Lord: ‘karttikeya-vapudharine namah’. Correspondingly, Markandeya one of the oldest Puanas names Kumara as ‘Vasudeva-priya’, the one who is dear to Vasudeva. Kumaraswamy is a member of the parivaram (entourage) of Vishnu. Further, Vishnu and Kumara are said to have an ‘understanding’ and recognition of each others might.

54.4. The Vaikhanasa association with Kumara (unlike in other Vaishnava tradition), even to this day, suggest the faint memory of its origin in the tantric traditions of the distant past. Some say; the Vaikhanasa practice of reciting Vedic mantras along with Tantra-related rituals suggests its emanation from the oldest phase of worship in the Chaitya-s , the earliest form of temples. Although the Vaikhanasa mode of worship may have evolved and changed over the long periods, its core is indeed very ancient; and is much older than other temple-traditions.

Vaikhanasa Literature

Vaikhanasa -Kalpa –sutra

55.1. Each of the four divisions of the Vedas has its own special Kalpa sutra. They are meant to guide the daily life and conduct of those affiliated to its division. Generally, the set of Kalpa sutra texts include: Grihya-sutra (relating to domestic rituals); Srauta-sutra (relating to formal yajnas); Dharma-sutra (relating to code of conduct and ethics); and Sulba-sutra (relating to mathematical calculations involved in construction of Yajna altars (vedi, chiti) and platforms); and specification of the implements used in Yajna (yajna-ayudha).

Thus, Kalpa sutras by their nature are supplementary texts affiliated to the main division of a Veda.

55.2. Vaikhanasas belonging to Taittiriya division of Krishna–Yajur Veda are perhaps the only group that rely heavily on their Kalpa sutra. Vaikhanasa -Kalpa –sutra is the primary text; the basic and authoritative scripture of the Vaikhanasa tradition. And, all other definitive texts, manuals, traditions, beliefs and practices are derived from this source. It, in essence, provides the necessary framework, code of conduct for a Vaikhanasa in his spiritual, personal, family and social life. The text is intended to guide him in all spheres of life.

55.3. Vaikhanasa-Kalpa-sutra is ascribed to the ancient Sage Valkanas who is said to have received it from Brahma or Vishnu. It has come down to us in oral traditions; and its age is rather uncertain. But surely, its origins are in the very distant past. Some scholars date it around the third century of the Common Era.

56.1. The Vaikhanasa-kalpa-sutra is indeed a group of four texts. The whole set of texts is spread over thirty two prasnas (chapters). Its three main segments include: Vaikhanasa-srauta-sutra (21 chapters); Vaikhanasa-grihya-sutra or smarta-sutra (7 chapters); and, Vaikhanasa-dharma-sutra (3 chapters). And, in addition there is a chapter named Vaikhanasa-Pravara-sutra.

56.2. As may be seen, the Vaikhanasa-kalpa-sutras (page 29) consist of 32 chapters. Among them are 7 Grihya sutras; 3 Dharma sutras; 21 Srouta sutras ; and , 1 Pravara sutra .

But, it does not contain a Sulba-sutra of their own. That might be because of the secondary position assigned in this tradition for performing Yajnas. Instead , they have Pravara-sutra that deals with genealogy of the seers who initiated families (vamsha) into Vaikhanasa tradition. However, the matters relating to Sulba –sutras are covered under its two other sections (srauta and grihya).

Please also see An Introduction to Vaikhanasa Kalpa Sutra by Sri Animeshnagar

Vaikhanasa – srauta – sutra

57.1.The Srautasutras, a well-marked group of works, forming the major part of the Vedanga , the Kalpa, deal with the Vedic ritual in a systematic and concise manner. They differ from Veda to Veda; and in case of a given Veda , from one Sakha to another. The Vedic affiliation of a Srautasutra determines its main interest in the Yajna, namely the duties of the officiating priest belonging to that Veda, while the differences in the Sakhas pertain to minor variations in the performance of the ritual.

The Srautasutras , belonging to the Yajurveda, naturally deal with the performance of Yajnas from the view-point of the Adhvaryu ; and, the prominent role played by that priest in the ritual. It is only in late works called the Prayogas that we get complete view of the Vedic ritual as a whole. Among the Srautasutras of the Yajurveda, two appear to be the fullest namely those of Apastamba and Katyayana, and the later one is more systematic and possesses a good commentarial tradition in comparison with the former

57.2. The Vaikhanasa- srauta-sutra deals with all types of ritual-actions which need to be carried out daily (nitya) and occasionally (naimittika), in addition to several types of yajnas (yaga-yajna). There is also a section on purification rituals (prayaschitta) to take care of minor or major lapses in conduct of rites or in personal behavior. The srauta – texts are not however held in highest regard because the rituals are motivated by desire (kamya) to acquire something or the other.

Vaikhanasa – grihya – sutra or smarta sutra

58.1. In order to preserve the Vedic affiliation, a Grihya-sutra was essential. The Vaikhanasa –grihya –sutra or smarta sutra emphasizes devotion to Vishnu or Narayana. It provides the main framework for Vishnu –worship ; prescribes rules governing life in household and also the rules for installation (prathista) and worship of Vishnu’s image at home (grharchana bimba prathista archana), in a shrine or in the yajna mantapa pavilion; and, for introduction of divine power (shakthi) into the image before its worship.

The icon which is divinely auspicious (divya-mangala– vigraha) should be sculpted according to the prescriptions of Shilpa-shastra (shilpa-shastrokta-vidanena). The text prescribes that the icon of Vishnu must be duly installed at home (tasmad grihe param Vishnum prathistya) and should be worshipped daily – morning and evening- (saayam-prathya) after performing the customary homas. It also discusses, in detail, about other religious observances.

58.2. The text includes invocation of four aspects of Vishnu: Purusha, Satya, Achhuta and Aniruddha. The invocations prescribed here involve two mantras: one of eight syllables – ashtakshari mantra- (Om namo Narayanaya) and the other of twelve syllables – dwadashakshari mantra – (Om namo Bhagavate Vasudevaya).

These mantras are of great importance and of sacredness in Vaishnava traditions ; and are regarded as divine sacraments (daivika).

According to the Vaikhanasa; these five states of Vishnu are represented by the five Vedic fires: Garhapatya; Ahavaniya; Dakshinagni; Anvaharya; and, Sabhya.

58.3. Vaikhanasa – smarta – sutra is perhaps the only text of its kind to prescribe a ceremony for entering into the hermit stage of life (Vanaprastha). It describes ways of the hermits devoted to Vishnu and practicing Yoga involving ten external observances, niyama (bathing, cleanliness, study, ascesis, generosity etc) ; and ten internal observances , yaama ( truthfulness, kindness, sincerity etc) .

58.4. Vaikhanasa-smarta-sutra also teaches yogic paths leading to Brahman without qualities* (nishkala). It contrasts actions with desire (sa-kama) seeking fruits of action in this world and in the next, with actions without desire (nis-kama) performance of prescribed actions with a sense of duty and without expectations. The desire-less action (nis-kama) is of two kinds: activity (prvrtti) and disengagement (nivrtti) .

Here, ‘activity’ signifies yogic practices which procure yogic-powers, but not leading to release from samsara the series of births. Disengagement (nivrtti), in contrast, relates to the way of yogis who are solely intent upon realizing Supreme Self and to attain union (yoga) of the individual self with the Supreme Self.

[*This view point as the primacy of Brahman without attributes (nir-guna) and with attributes (sa-guna) differs significantly from the position taken by the later Vaishnava Vedanta School of Vishistadaita. ]

Samskaras

59.1. Vaikhanasa – grihya – sutra deals in particular with eighteen life-cycle-rites (samskaras) which are meant to cleanse the body and mind of one born in the Vaikhanasa lineage ; and attune him to be fit for rendering service to Vishnu . The rituals range from niseka (ritu –san – gamana first mating in the proper season) and garbhadana (impregnation) to samavarthana (return from study) and pani-grahana (marriage). In effect, it prescribes rites ranging from before-birth and ending with death and cremation (jatakaadi – smasananta).

[It is said; there was another text (Vaikhanasa-grihya- parishistya-sutra) which supplemented the main Grihya-sutra text. Its passages are quoted in other Valkanas texts. But, it is not available at present.]

59.2. Grihya-sutra emphasizes the significance of pre-natal samskaras. These are directly linked to the marriage and birth in a Vaikhanasa family. The related samskaras are meant to define and lend specific identity to a Vaikhanasa. The inherited identity is beyond the scope of discretion. One has to be a born-Vaikhanasa (janmathah). Initiation or conversion into Vikhanasa sect is ruled out. Pre-natal -life-cycle –rituals (garbha-samskara), thus, become one of the distinguishing features of the Vaikhanasa community. This and the rituals of Vishnu-Bali are important for their identity.

Vishnu–Bali

60.1. Of the five parental samskaras, the one symbolic ceremony, in particular, has developed into an essential characteristic of the Vaikhanasas; and up to the present day, it plays an important role in defining their specific identity. This is a samskara performed in the eighth month of pregnancy following Pumsavana and Seemantha (parting of the hair) meant for the benefit of the pregnant woman and the foetus growing within her. And, this is known as Vishnu–Bali (or garbha-chakra samskara) prescribed to be performed during the bright-half of the eighth of pregnancy (garbhaadhady-astame masyeva shukla pakshe).

60.2. The significance of the offering (Bali) to Vishnu is that, while even as the un-born is inside the mother’s womb , as fetus, it acquires the status of a Vaishnava (garbha-vaishnavesti), a Vishnu devotee (garbha vaishnavatava siddyarthyam) .

The ceremony involves offering the pregnant woman a cup of payasam in which the insignia of Vishnu- chakra is dipped. The infant the moment it is born is deemed a Vaishnava by birth (garbha-Vaishnava -janmanam), not needing any initiatory rites (diksha) or branding.

In the case of such male offspring, he automatically becomes eligible to render temple worship-rituals. As it is often said;’ they indeed are Vihṣṇu’s children, protected by Vishnu and preordained for temple service even before birth’.

Vishnu-Bali and the significances attached to it illustrate the concern of the Vaikhanasa community to distinguish themselves as Vaidikas who are different from other Vaishnava sects, particularly the Pancharatras, and also to assert their premier position as born-priests not needing any other sort of vaishnava-diksha.

Vaikhanasa – dharma – sutra

61.1. A Vaikhanasa, a born-priest (janmathah-archaka) is guided by Vaikhanasa- Grihya sutra and Dharma-sutra , which are within the orthodox Vedic culture. The Vaikhanasa – dharma –sutra also deals with religious life; and the conduct, duties and responsibilities in different stages of life (asramas).

They also detail the eight-fold system of yoga (ashtanga-yoga) and related spiritual practices.

Works of the four sages: Vaikhanasa Shastra – Agama – Samhita

62.1. Sage Vaikhanasa is said to have taught his doctrine to his nine disciples: Kashyapa; Atri; Marichi; Vashista; Angira; Bhrgu; Pulasthya; Pulaha; and Kratu. Among these, four rishis viz. Atri, Bhrgu, Kashyapa, and Marichi composed a set of texts, based on the philosophy expounded by Sage Vaikhanasa, detailing various aspects of worship, conduct in personal life and several other disciplines. The collection of these texts along with Vaikhanasa’s original instructions constitutes the core of the Vaikhanasa literature.

62.2. Vimanarchana –kalpa (1001.1) a prose work which elaborates on worship of Vishnu–icon , ascribed to Marichi talks about the doctrine taught by Sage Vaikhanasa to his four chief disciples: Bhrgu, Kashyapa, Atri and Marichi .The disciples who received the knowledge from their Master expanded upon his philosophy and teachings.

And, they produced four classes of texts: Bhrgu (Tantras); Kashyapa (Adhikaras); Atri (Kandas); and Marichi (Samhitas). The four sets of texts together ran into four lakh granthas; each grantha being 32 letters composed in anustubh chhandas (metrical form).

62.3. Vimānārcakakalpa of Marichi mentions thirteen works attributed to Bhrgu:

-

- Khilatantra;

- Puratantra;

- Vasadhikara ;

- Chitradhikara ;

- Manadhikara ;

- Kriyadhikara ;

- Archanadhikara ;

- Yajnadhikara ;

- Varnadhikara ;

- Prakirnadhikara ;

- Pratigrihyadhikara ;

- Niruktadhikara ; and ,

- Khiladhikara.

Kashyapa is said to have composed three Samhitas consisting 64,000 verses: Satyakanda; Tarkakanda; and, Jnanakanda.

Atri is credited with four works spread over 88,000 verses composed in anustuph chhandas: Purvatantra; Atreyatantra ; Vishnutantra; and, Uttaratantra.

The set of eight Samhitas (1, 84, 000 granthas) composed by Sage Marichi form the Vaikhanasa Samhita (samhita-ashtaka).The titles of the eight Samhitas are said to be : Jaya ; Ananada; Samjnana ; Vira ; Vijaya; Vijita; Vimala ; and Jnana Samhita.

[Having said this, let me also mention that there also alternate lists of the texts attributed to these four Rishis.]

62.4. The collection of four lakh granthas, spread over 128 books, came to be known as Vaikhanasa Shastra (chatur-laksha grantham pradadur etad Vaikhanasam shastram ). They are also collectively known as Vaikhanasa Agama.

62.5. All these four classes of texts acknowledge that the Vaikhanasa- kalpa – sutra handed down by their Master Sage Vaikhana is their primary source; and it is the Authority for the Vaikhanasa sampradaya.

63.1. Although the Kalpa –sutras of Vaikhanas provided the inspiration and the substance for the later Vaikhanasa writings, a distinction is drawn between the Sutra (of Valkanas) and the Shastra (by his disciples).

Kalpa-sutra is different in its approach from its Shastra or Agama texts. There is a marked difference between the environment of Kalpa-sutra period and that of the Agama shastra. The Kalpa-sutra belongs to a period when Yajnas and related rituals as prescribed in Yajur Veda , the Brahmanas etc were still being performed fairly regularly .

But, by the time of the Agamas, the age of the Yajnas was fading out; and the prescriptions of the srauta section of Kalpa –sutra were also losing the focus of attention. However, the Grihya –sutra section (which deals with domestic rituals) based on the Smritis and which is also known as Samarta –sutra was still relevant, and it was gaining greater importance.

Transition: Veda – Kalpa –Agama

64.1. We see here a transition from Vedas to Kalpa and then on to the Agama. The worship of Agni (homa-puja) which was the focus of attention in the Vedic period was translated by the Kalpa into the worship of Vishnu in the iconic form (bera-puja). Vishnu was a prominent Vedic god; and in the Brahmanas Vishnu came to be regarded as the very personification of Yajna (yagno vai Vishnuh)

Following that, the Kalpa Sutra said, the worship of Vishnu is indeed equivalent to the performance of Yajna.The kalpa- sutra therefore prescribed worship of Vishnu in the household along with the customary ritual-fires. The Agamas thereafter not only transformed the Vedic Yajna ideology (amutha-archana) into worship of Vishnu, but also extended it into worship of icons installed in temples (samurtha-archana). Though the Vedic rituals gradually gave place to worship of Vishnu-icon, the Agama did not entirely give up Vedic rituals.

64.2. The archana (service to the images) detailed in the Vaikhanasa Agama represents the community’s transition from a Vedic School of ritual observance to a Bhagavata tradition emphasising bhakthi towards Narayana and worship of Vishnu/Narayana idol installed at the temples. The Kalpa-sutra always addressed their Supreme deity only as Vishnu; and, Vaishnava ideology was evident. The use of the term Narayana was not yet prominent. But, by the time of the Agamas, the names Vishnu and Narayana came to be used alternatively.

64.3. And, when Vaikhanasa Agama was composed it had to comment on details which the Kalpa sutra did not contain; or elaborate on details which were only suggested by Sage Vaikhanasa. The requirements of Agama appear to have necessitated the composition of Shastra-texts by the four sages, to compliment the Kalpa-sutra handed down by their master.

64.4. Together with the Kalpa Sutras, the Vaikhanasa-samhita are traditionally taken to be the cannon of the Vaikhanasas (Vaikhanasa-shastra or Vaikhanasa-Bhagavad-shastra).

65.1. Vaikhanasa-Bhagavad-shastra or Vaikhanasa-Agama, in many ways, compliment the Vaikhanasa-kalpa-sutra. It also elaborates on certain issues that the Kalpa –sutra did not touch upon.It is said; the Kalpa-sutra of Vaikhanadid not deal with temple-worship at all; and, even the worship at home was discussed rather briefly. But, his disciples realizing the importance of worshipping Vishnu in temples and having in view the greater good of all mankind, elaborated on this aspect following the broad principles for worship at home as mentioned in the Kalpa –sutra. And, that, it is said, resulted in Vaikhanasa- Agama.

65.2. The Vaikhanasa tradition frequently avers to its Vedic affiliation and Vedic authority. But, in its living practices it is mostly about temple-rituals. The texts now classed under Vaikhanasa Agama are primarily ritual texts (prayoga shastra); and they contain elaborate discussions on various aspects concerning temples as also instructions on practical aspects of worship-procedures. The jnana-paadas of Vaikhanasa Agama texts are brief as compared to discussion on rituals.

[It is said; initially, the Vaikhanasa texts did not generally employ the term Agama to describe themselves. They were known as ‘Vaikhanasa– Bhagavad-shastra’ or as ‘Daivika-sutra’. However, the term Vaikhanasa-Agama came into use in later times in order to distinguish them from other Agama traditions.]

Subjects dealt by the four classes of texts

66.1. The four classes of texts produced by the four disciples of Sage Vaikhanasa may be considered as different streams of the same tradition or School handing down the same ritual doctrine and practices, but with slight variations when it comes to the details of ritual – sequences, circumstantial descriptions of the same set of procedures or ceremonies. But, the texts attributed to the four sages, in the main, are in agreement as regards their content and the disposition of the topics dealt with. They even tend to quote each other.

66.2. The main tantras pertaining to the installation and worship of idols are in Bhrgu, Atri, Kashyapa and Marichi Samhitas. They deal with building a shrine to Vishnu (karayathi mandiram); making a worship-worthy beautiful idol (pratima lakshana vatincha kritim); and worshiping everyday (ahanyahani yogena yajato yan maha-phalam).

The texts primarily refer to ordering one’s life in the light of values of icon worship (Bhagavadarcha), to usher in a sense of duty, commitment and responsibility.

The Bhrgu, Atri and Marichi Samhitas in particular go into different aspects of architecture of Vaikhanasa Vishnu temples, while other fragments cover Chitra karma or painting of pictures of deities.

66.3. The Vaikhanasa-tantra texts (ascribed to Bhrgu) broadly deal with :

-

- (i) karshana (construction of shrines);

- (ii) prathishtha (installation of idols of gods);

- (iii) puja (worship of the idols);

- (iv) snapana (the abhisheka or bathing of idols);

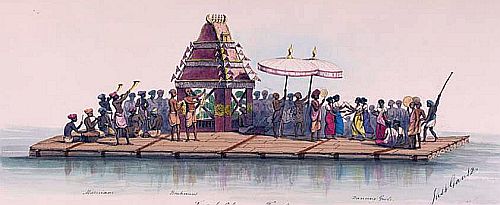

- (v) utsava (festivals and processions); and ,

- (vi) prayashchitta (expiatory rites relating to errors in rituals).

66.4. Atri’s Kandas also cover these topics at great depth in addition to the design of temples. Adhikaras are mainly in the form of sutras. The basic plan of a temple is termed the Vimana. The Atri samhita enumerates 96 different plans of Vimanas, which are described as belong to the several basic classes termed Brahma, Vishnu, Rudra, Indra, Soma and those of various Rishis.

Apart from these; the Kashyapa gives a description of the world; a classification of the good (auspicious) and evil elements; the appeasement of the ominous, causes of welfare and defeat; directions for construction of houses; the donations of village; plans for towns and villages; etc

67.1. The Agamas combine two types of instructions: one providing the visualization of the icon form; and the other giving details of preparation of icon for worship. This is supplemented by prescriptions for worship of the image and the philosophy that underlies it.

When the four classes of texts are put together, in regard to the subjects relating to construction of temples, mainly, the following are discussed:

-

- the types of shrines; inspection of temple-site;

- preparatory ploughing on that site;

- the deposit of the temple-embryo;

- the construction of a provisional miniature temple (bala-alaya) for Vishnu and his attendant deities during the time when the main sanctum is under construction or when an evil omen or a damage has occurred; temple architecture;

- collection of materials (stone and wood);

- construction of the temple proper;

- iconography of Vishnu images and of other deities;

- preparation of the clay for modelling the image;

- the measures of the image , ornaments etc;

- sculpting of the images; the measure and other characteristics of the frames and their construction; consecration and installation of of the icon;

- the oblation into five fires;

- the sequence of daily worship in the temple;

- occasional festivals, celebrations (uthsava) ; etc.

As regards the topics related to worship at the temple, the following stages are described:

-

- entering the temple;

- duties of the assistants (such as the water fetcher and others);

- meditation and personal preparation of the priest; bathing of the image ;

- preparations and worship of the minor deities ;

- invocation of Vishnu; worship of Vishnu;

- various details about the flowers to be offered or to be avoided ;

- details about the elements of daily worship; various details about the consecration and worship of Avatars;

- extensive bathing on special occasions or to regenerate the divinity of the image;

- the festival;

- the atonement or correction of errors (pryaschitta) etc

67.2. In the next part let’s continue with the Vaikhanasa literature and then go on to Vaikhanasa philosophy and its preoccupation with temple –worship.

Vaikhanasa Continued in Part Four

References and Sources

1. A Companion to Tantra by S C Banerji ; Abhinav Publications (2007)

2. Tantra: its mystic and scientific basis by Lalan Prasad Singh ;Concept Publishing Company (1976)

3. Tribal roots of Hinduism by SK Tiwari ; Sarup & Sons (2002)

4. The Tantric way by Ajit Mukherjee and Madhu Khanna ; Thames & Hudson (1977)

5. Agama Kosha by Prof. SK Ramachandra Rao ; Kalpataru Research Academy (1994)

6. The Perspective of the Tantras By K. Guru Dutt

http://yabaluri.org/TRIVENI/CDWEB/theperspectiveofthetantrassept45.htm

7. Tantra Shastra and Veda by Sir John Woodroffe

http://www.sacred-texts.com/tantra/sas/sas04.htm

8. The Tantras: An Overview by Swami Samarpanananda

9. Evolution of Tantra by Nitin Sridhar

http://www.esamskriti.com/essay-chapters/Evolution-of-Tantra-1.aspx