Lakshana Granthas – continued

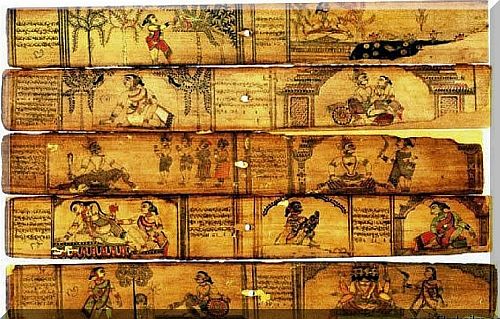

9. Manasollasa / Abhilasita-artha-cintamani of King Somesvara

Manasollasa (मानसोल्लास – that which delights Manas-heart and mind), also called Abhjilashitarta-Chintamani (the wish-fulfilling precious gem) ascribed to the Kalyana Chalukya King Someshwara III (ruled 1126-1138 AD) is an encyclopaedic work, written in Sanskrit, covering wide ranging varieties of subjects.

Someshvara III was the third in the line of the Kings of the Kalyani Chalukyas (also known as Western Chalukyas). He was the son of the renowned King Vikramaditya VI (1076-1126) and Queen Chandaladevi. King Someshvara, celebrated variously as Tribhuvana-malla, Bhuloka-malla and Sarvanjya-bhupa, was a remarkable combination of an enlightened Ruler and an erudite scholar.

Someshvara was a noted historian, scholar and poet; and, his fame as an author, rests on his monumental compilation Manasollasa. He is also said to have attempted to script a biography of his father Vikramaditya VI, narrating his exploits, titled Vikramanka-abhyudaya; but, the work remained incomplete.

King Someshwara was also an accomplished musician and a gifted composer. He is said to have composed in varied song-formats such as: Vrtta, Tripadi, Jayamalika, Swaraartha, Raga Kadambaka, Stava Manjari-, Charya and so on. He composed Varnas, Satpadis and Kandas in Kannada language. In addition, he compiled Kannada folk songs relating to harvest –husking season, love, separation (in Tripadi); marriage-songs (in Dhavala); festival and celebration songs (Mangala); songs for joys dance with brisk movements (Caccari); songs for marching-soldiers (Raahadi); Sheppard-songs (Dandi); and, sombre songs for contemplation (Charya).

Someshvara is said to be the earliest to codify the tradition of allocating the six Ragas to the six seasons:

-

- (1) Sri-raga is the melody of the Winter

- (2) Vasanta of the Spring season

- (3) Bhairava of the Summer season

- (4) Pancama of the Autumn

- (5) Megha of the Rainy season and

- (6) Nata-narayana of the early Winter.

Prince Someswara was regarded by the later authors as an authority on Music and Dance. And, Basavabhupala of Keladi (1684 A.D.-1710 A.D.) composed his Shiva-tattva-ratnakara modelled on Somesvara’s Manasollasa. The noted musicologists Parsvadeva and Sarangadeva quote from Manasollasa quite often. Further. Sarangadeva in his work mentions Someswara along with other past-masters of music theory (Rudrato,Nanya-bhupalo,Bhoja-bhu-vallabhas-tatha, Paramardi ca Someso, Jagadeka-mahipatih).

Someswara describes two schools of music-Karnata and Andhra; and, remarks that Karnata is the older form. This, perhaps, is the earliest work where the name Karnataka Sangita first appears (Musical Musings: Selected Essays – Page 46 )

Manasollasa defines chaste Music as that which educates (Shikshartham), entertains (Vinodartham), delights (Moda-Sadanam) and liberates (Moksha–Sadanam) –

Shikshartham Vinodartham Cha, Moda Sadanam, Moksha Sadanam Cha.

This, I reckon, by any standard, is a great definition of Classical Music. And, this is how the chaste and classical music is defined even today.

Such Music, he says, should be a spontaneous source of pleasure (nirantara rasodaram), presenting varied Bhavas or modes of expressions (nana-bhaava vibhaavitam); and , should be pleasant on the ears (shravyam) .

Someshwara classified the composers (Vak-geya-kara) into three classes: the lowest is the lyricist; the second is one who sets to tune songs of others; and, the highest is one who is a Dhatu Mathu Kriyakari – one who writes the lyrics (Mathu), sets them to music (Dhatu); and, ably presents (Kriyakari) his composition.

Someshvara III was succeeded by his son Jagadeka-malla II (r.1138–1151 CE), also known as Pratapa-Prithvi-Bhuja. He was also a merited scholar, who wrote Sangitha-chudamani, a work on music. He was the patron of the scholar and Grammarian Nagavarma II, the author of famous works, in Kannada, such as: Kavya-avalokana and Karnataka-Bhasha-bhushana.

The Sangita-Cudamani of Jagadeka-malla covers many topics related to music, such as: Alapana and Gamaka; the desired qualities of a singer, of a composer; the voice culture; design of the auditorium, and so on. The later scholar Parsva Deva (12th century), the author of Sangita Samayasara, followed the work of Jagadeka-malla on subjects like Ragas, Prabandhas, etc. Sarangadeva’s Sangita-ratnakara (first half of 13th century) also mentions Jagadeka-malla (Jagadeka-mahipatih) , with respect.

It is said; Someshvara commenced compiling the Manasollasa, while he was a Prince; and completed it during 1129 (1051 Saka Samvatsara), which is about two-three years after he ascended the throne.

The Manasollasa covering a wide variety of subjects ranging from the means of acquiring a kingdom, methods of establishing it, to medicine, magic, veterinary science, valuation of precious stones , fortifications, painting, art, games, amusements , culinary art, dance, music and so on; is a monumental work of encyclopedic nature. The text, in general, provides valuable information on the life of those times. It is also of historical importance as it gives the geographical description of Karnataka of 12th century; as also of the contemporary socio-cultural and economic conditions; and of the varied occupations its people.

The entire work of the Manasollasa extends to about 8000 Granthas or verse-stanzas; and, it is composed in the Anustubh Chhandas (metre), with few prose passages interspersed in between. Its Sanskrit is simple and graceful; making it one among the elegant works of Sanskrit literature that reflect the life and culture of mediaeval India.

The treatment of the subjects is sophisticated, cultured, suiting the elite atmosphere of a King’s court. The style of presentation is lucid; and, is yet concise.

*

The Manasollasa, virtually, is a guide to royal pastimes; and, is divided into five sections, each containing descriptions of twenty types of Vinodas or pastimes. The reason, each section is called a Vimsathi (विंशति), is because; each contains twenty Adhyayas (chapters). The book is thus a tome of 100 Chapters, which are grouped into five Viṁśathis (twenties). But, since the Chapters are of unequal length, the Vimsathis also vary in size.

Each Section (Vimsathi) is dedicated to specific sets of topics. The five Vimsathis are:

Rajya Prakarana; Prapta-Rajya Sthairikarana; Upabhoga; Vinoda and Kreeda

:- The First Vimsathi, the Rajya Prakarana, describes the means of obtaining a kingdom and governing it efficiently; the required qualifications for a king who desires to extend his kingdom; as also the qualifications of the ministers, their duties and code of conduct that enable the King to rule a stable, prosperous kingdom. It recommends delegation of powers to various authorities at different levels, with a limited degree of autonomy, under the overall supervision of the ministers.

:- The Second Vimsathi, the Prapta Rajya Sthairikarana describes the ways of maintaining a king’s position strong and stable; retaining it securely; and, ways of governance of the State, its economics, infrastructure, architecture etc. It also talks about maintenance and training of a standing army, the required capabilities and responsibilities of its commander (Senapathi). This sub-book includes chapters on veterinary care, nourishment and training of animals such as horses and elephants that serve the army.

As regards economy, it mentions about the administration of the Treasury and taxation; of levying and collection of taxes (Shulka).

:- The Third Vimsathi, the Upabhogasya Vimsathi details twenty kinds of Upabhogas or enjoyments; and, describes how a king must enjoy a comfortable life, including cuisine, ornaments, perfumery and love-games.

It also speaks of other pleasures of sumptuous living, such as: living in a beautiful palace; enjoying bathing, body-massage, anointing, gorgeous clothing, attractive flower garlands, stylish footwear, rich ornaments; having elaborate royal seat, trendy chariot, colorful umbrella, luxurious bed, enchanting incense; and , enjoyable company of beautiful and witty women etc.

In this section, two chapters are dedicated to Annabhoga or enjoyment of food, describing how various recipes are to be prepared as well as how they should be served to the king. Manasollasa is a treasure trove of ancient recipes. And Jala or Paniyabhoga, talks about the enjoyment of drinking water and juices (Panakas).

The text mentions that fresh and clean water is Amrita (nectar); else, it cautions, if it is sullied, it would turn to Visha (poison). Someshvara recommends that water collected from rains (autumn), springs (summer), rivers and lakes (winter) for daily use, be first boiled and be treated with Triphala, along with piece of mango, patala or champaka flower or powder of camphor for health, flavour and delight.

:- The Fourth Vimsathi of Manasollasa, the Vinoda Vimsathi, deals with entertainment such as music, dance, songs and competitive sports. It speaks of diversions like: elephant riding, horse riding, archery, fighting, wrestling, athletics, cockfights, quail fights, goat fights, buffalo fights, pigeon fights, dog games, falcon games, fish games and deer hunting etc.

It also mentions the cerebral pleasures such as: rhetoric, scholarly discussions, vocal music, instrumental music, dancing, storytelling and magic art.

The Vinoda-Vimsathi also describes how a king should amuse himself, with painting, music and dance. The subjects of Music and dance are covered under Chapters sixteen to eighteen of the Vinoda Vimsathi. The vocal and instrumental Music is covered in two sections: Geeta Vinoda and Vadya Vinoda; and, dances are covered under Nrtya Vinoda.

: – The Fifth and the last Vimsathi, the Krida-Vimsathi describe various recreations. The last two sections, in particular, are virtually the guides to Royal pastime (Vinoda). These include sports like: garden sports, water sports, hill sports and sporting with women; and, games like gambling and chess.

[Please check here for a detailed article about the significance of Manasollasa]

The text is notable for its extensive discussion of arts, particularly music and dance. A major part of Manasollasa is devoted to music and musical instruments, with about 2500 verses describing various aspects of it. Thus, the two exclusive chapters concerning music and dance have more number of verses than the first two sub-books put together. That might, perhaps, reflect the importance assigned to performance arts during the 12th-century India. And, Someshvara III’s son and successor king Jagadeka-malla II also wrote a famed treatise on music, Sangita-Cudamani.

As regards Dance, the Manasollasa deals with the subject in the Sixteenth chapter, having 457 verses (from 16.04. 949 to 16.04.1406), titled Nrtya-Vinoda, coming under the Fourth Vimsathi of the text – the Vinoda Vimsathi – dealing with various types of amusements.

Manasollasa is the earliest extant work presenting a thorough and sustained discussion on dancing. It not only recapitulates the accumulated knowledge on dancing, inherited from the previous authorities; but also gives a graphic account of the contemporary practices. Someshvara, sums up the views of the earlier writers, which continue to have a bearing on the dance scene of his time (12th century); and, lucidly puts forth his own comments and observations. Here, Someshvara, retained, in his work, only those ancient dance-features (Lakshanas) that were relevant to his time; and, eliminated those Lakshanas which were no longer in practice.

And, another important factor is that Someshvara introduces many terms, concepts and techniques of dancing that were not mentioned by any of the previous dance practitioners and commentators. He mentions new developments and creations that were taking place, as noticed by him.

The Manasollasa is, thus, a valuable treasure house of information on the state of dancing during the ancient times. Another important contribution of Nrtya Vinoda is that it serves as a reliable source material for reconstruction of the dance styles that were prevalent in medieval India.

It is also the earliest work, which laid emphasis on the Desi aspect for which the later writers on this subject are indebted.

The notable features of the Nrtya-Vinoda are: the orderly presentation of topics; concise rendition facilitating easy reference; and, the prominence assigned to current practices that are alive than to the ancient theories.

For these and other reasons, the Nrtya-Vinoda of Manasollasa, occupies a significant place in the body of dance literature.

Someshvara introduces the subject of dancing by saying that dances should be performed at every festive occasion (Utsava), to celebrate conquests (Vijaya), success in competitions and examinations (Pariksha) and in debate (Vivada); as well as on occasions of joy (Harsha), passion (Kama), pleasure or merriment (Vilasa), marriage (Vivaha), birth of an offspring (putra-janma) and renouncement (Thyaga)- Manas.950-51

He then names six varieties of dancing; and, six types of Nartakas. The term Nartaka, here, stands for performers in general; and, includes:

Nartaki (danseuse),Nata(actor),Nartaka(dancer),Vaitalika (bard), Carana (wandering performer) and kollatika (acrobat).

Someshwara uses the term Nartana to denote Dancing, in general, covering six types: Natya (dance with Abhinaya), Lasya (graceful and gentle), Tandava (vigorous), Visama (acrobatic), Vikata (comical) and Laghu (light and graceful).

The other authors, such as Sarangadeva, Pundarika Vittala and others followed the classifications given Manasollasa.

[Someshvara cautions that Kings would do well to avoid performing dance items like Visama (acrobatic) and Vikata (comic); perhaps because, they were rather inappropriate for a King.]

Manasollasa is also significant to the theory of Dance, because it caused classifying the whole of dancing into two major classes: the Marga (that which adheres to codified rules) and Desi (types of unregulated dance forms with their regional variations).

Manasollasa also introduced four-fold categories of dance forms: Nrtya, Lasya, Marga and Desi.

In regard to Dance-movements, Someshwara classifies them into six Angas, eight Upangas and six Pratyanga; with some variations, as compared to the scheme devised by Bharata.

The other important contribution of Someshvara is the introduction of eighteen Desi karanas, (dance poses and movements) that were not mentioned in other texts. However, the Desi aspects are discussed without mention of the word.

*

Somesvara’s exposition of Dance techniques could be, broadly, classified under two groups: (1) body movements relating to Anga, Upanga and Pratyanga; and, (2) the other relating to Sthanas, Caris and Karanas etc.

In regard to the former category, relating to the Angika-Abhinaya, Someshvara, in his Nrtya Vinoda, generally, follows the enumerations and descriptions as detailed in the Natyashastra of Bharata (Marga tradition) , with a few variations and modifications. And, the discussion on Angika Abhinaya occupies a considerable portion of the Nrtya Vinoda.

The Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas enumerated and described by Someshvara under the Nrtya Vinoda were classified by the later scholars as belonging to the Desi tradition. That was because they differed from the ‘Margi’ Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas of Bharata‘s tradition. However, Someshvara had not specifically employed the term ‘Desi’ while describing those dance-phrases. He had merely stated in the Gita-Vinoda section that he will be discarding the Lakshanas, as enunciated by Bharata; and, that he will only deal with the techniques that are developed and are in practice (Lakshya) during the current times. The scholars surmise that might be the reason why he does not specify the Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas described by him as belonging to the Desi Class.

**

Angika Abhinaya

As mentioned earlier; with exception of a some elements, the treatment of the Angika Abhinaya in the Nrtya Vinoda, to a large extent, follows the Natyashastra of Bharata. But, Someshvara made some changes in the arrangement of the limbs, within the three groups of limbs.

For instance; Bharata, under the category Anga had listed the head, the hips, the chest, the sides and the feet. And, under the Pratyanga, he had mentioned: the neck, the belly, the thighs, the shanks and the arms. And, under Upangas, Bharata had included the eyes, the eyebrows, the nose, the lips, the cheeks and the chin.

Someshvara, under the Angas followed the general pattern of classification as laid down by Bharata; but, included shoulders and belly in place of the hands (Hasthas) and feet (Padas). His Pratyanga includes the arms, the wrists, the palms, the knees, the shanks and the feet. And, under the Upanga, Someshvara included teeth and tongue (Bharata had not reckoned either of these under his scheme.)

Almost all writers follow the classification made by Bharata; and, not that of Somesvara. And, that doesn’t seem surprising; because, the hands (Hasthas) and feet (Pada-bedha) are the most essential elements of any dance-form. They surely are indeed one among the major-limbs (Anga) so far as the dance is concerned; and, it may not be right to treat these as minor-limbs (Pratyanga) as Someshvara did.

But, some justify Someshvara’s position, saying that he was mainly concerned with the Desi-Dance form where the emphasis was more on the agile, rhythmic and attractive feet and body movements than on the Abhinaya or expressions put out through eyes, facial expressions and palms.

At the same time; it is said that Someshvara was not wrong in classifying shoulders and belly under the major-limbs (Anga); since, anatomically they indeed are large.

As regards the thighs, they are not included by Someshvara in all the three categories; perhaps because the movements of the shanks also account for that of the thighs.

Bharata had not mentioned either the teeth or the tongue in his classifications; but, these are included by Someshvara under Upangas.

**

The elements covered under Anga, Upanga and Pratyanga in both the texts are as follows:

Angas (major limbs)

Under the Angas (major limbs), Someshvara enumerates the movements of the: Head (13 types); Shoulder (5); Chest (5); Belly (4); Sides (Parshva); and Waist (5).

(1) The Thirteen types of head movements (Shiro-bheda) comprised :

-

- Akampita (slow up and down movement);

- Kampita (quick up and down movement);

- Dhuta (slow side to side movement);

- Vidhuta (quick side to side movement);

- Ayadhuta (bringing the head down once);

- Adhuta (lifting obliquely);

- Ancita (bending sidewise);

- Nyancita (shoulders raised to touch the head);

- Parivahita (circular movement);

- Paravrtta (turned away);

- Utksipta (turned upwards);

- Adhogata (turned downwards); and ,

- Lolita (turned in all directions).

[All the thirteen head movements laid down by Bharata have been included by Somesvara, along with their explanations and uses.]

(2) Five shoulder (Bhuja) movements are:

-

- Ucchrita (raised);

- Srasta (relaxed);

- Ekanta (raising only one shoulder);

- Samlagna (clinging to the ears); and,

- Lola (rotating).

[Bharata had not discussed the shoulder movements.]

(3) Five chest (Urah or Vakṣaḥsthalam) movements are:

-

- Abhugna (sunken);

- Nirbhugna (elevated),

- Vyakampita (shaking);

- Utprasarita (stretched); and,

- Sama (natural).

[It is the same as in Bharata’s text.]

(4) Four belly (Jatara) movements are:

-

- Ksama (sagging);

- Khalla (hollow);

- Purnarikta (bulging and then emaciated); and,

- Purna (bulging).

[Bharata had mentioned only three; the Purnarikta is added by Someshvara.]

(5) Five side (Parshva) movements of sides are:

-

- Nata (bent forwards);

- Samunnata (bent backwards);

- Prasarita (stretched);

- Vivartita (turning aside); and,

- Apasrata (reverting back to the front).

[It is the same as in Bharata’s text; only, the definition of Prasarita is missing.]

(6) Five movements of the waist (Kati) are:

-

- Chinna (turned obliquely);

- Vivrtta (turned aside);

- Recita (moving round quickly);

- Andolita (moving to and fro); and

- Udvahita (raising)

[The names and descriptions of a couple of waist movements are changed.]

**

Upangas (features)

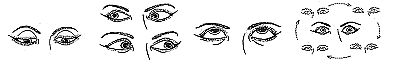

Under the Upangas (features) the following types of movements are listed: Eyebrows (7); Eyes (3); Nose (7); Cheeks (5); Lips (8); Jaws (8); Teeth (5) ; Tongue (5) and facial colours ( 4)

(1) Seven varieties of eyebrow movements (Bhru-lakshanam) :

-

- Utksipta (raised);

- Patita (lowered);

- Bhrukuti (knitted;

- Catura (pleasing);

- Kuncita (bent);

- Sphurita (quivering); and,

- Sahaja (natural).

[They are almost the same as in Natyashastra. The Sphurita, here is the same as Recita of Bharata; and, its description is also slightly different. But the movements of the eyeballs, eyelids, are not mentioned in the Nrtya Vinoda.]

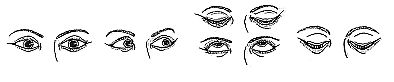

(2) Three groups of eye movements (Dṛṣṭī-lakṣaṇam) are based upon Rasa; Sthayi-bhava and Sancari-bhava.

The first group covers eight Rasas; the second eight Sthayi-bhavas; and the third has twenty Sancari-bhavas. The total number of glances is Thirty-six, the same as in the Natyashastra.

[As regards the use of the glances, Someshvara gives, in addition, the uses of the Sancari-bhava- glances, which were not in the Natyashastra.]

(3) Six kinds of nose (Nasika) movements :

-

- Nata (closed);

- Manda (slightly pressed);

- Vikrata (fully blown);

- Suchavas (breathing out);

- Vaikunita (compressed) and

- Svabhaviki (natural).

[It is the same as in Bharata’s text. Only the description of Suchavas varies slightly. ]

(4) Six types of cheek (Ganda) movements are:

-

- Ksama (diminished);

- Utphulla (blooming);

- Purna (fully blown);

- Kampita(tremulous);

- Kunchitaka (contracted); and,

- Sama (natural).

[It is the same as in Bharata’s text. Only the description of Purna and its uses varies slightly.

The Nrtya Vinoda does not discuss the movements of the neck.]

(5) Ten varieties of lip (Adhara) movements are :

-

- Mukula (bud-like);

- Kunita (compressed);

- Udvrtta (raised);

- Recita (circular);

- Kampita (tremulous);

- Ayata (stretched);

- Samdasta (bitten);

- Vikasi (displaying);

- Prasarita (spread out); and ,

- Vighuna (concealing).

[Of the ten varieties of lip-movements mentioned by Someshvara, only three of them (Kampita, Samdasta and Vighuna) are from the six listed by Bharata. The other seven lip movements described by Somesvara are taken from other texts.]

(6) Eight kinds of chin (Chibukam) movements are:

-

- Vyadhir (opened);

- Sithila (slackened);

- Vakra (crooked);

- Samhata (joined);

- Calasamhata (joined and moving);

- Pracala (opening and closing);

- Prasphura (tremulous); and,

- Lola (to and fro).

[Bharata had mentioned seven kinds of gestures of the chin (Cibukaṃ) ; and, these were combined with the actions of the teeth, lips and the tongue . In the list of Someshvara, except Vyadhir and Samhata, none of the other movements is mentioned by Bharata]

(7) Five types of teeth (Danta) movements are:

-

- Mardana (grinding);

- Khandana (breaking);

- Kartana (cutting);

- Dharana (holding); and,

- Niskarsana (drawing out).

(8) Five varieties of tongue (Jihva) movements are:

-

- Rijvi (straight);

- Vakra (crooked);

- Nata (lowered);

- Lola (swinging); and,

- Pronnata (raised).

[Bharata had not discussed teeth and tongue movements. Instead, he had mentioned six movements of the mouth (Mukha). ]

(9) Lastly, the four facial colors described are: Sahaja (natural), Prasanna (clear), Raktha (red); and, Shyama (dark).

[It is the same as in Bharata’s text.]

**

Pratyangas (minor limbs)

Under the Pratyangas (minor limbs) the following limbs are listed: Arms –Bahau (8); wrists (4); Hands-Hasthas (27 single hand, 13 both hands combined, Nrtta-hasthas 24); Hastha –Karanas (4); Knees (7); Shanks (5); and, feet (9);

Further, under the Nrtta (pure-dance movements), thirty types of Nrtta-hasthas (movements of wrist and fingers) are described.

(1) Eight movements of the arms (Bahu) are:

-

- Sarala (simple);

- Pronnata (raised);

- Nyanca (lowered);

- Kuncita (bent);

- Lalita (graceful);

- Lolita (swinging);

- Calita (shaken); and,

- Paravrtta (turned back).

[Bharata mentioned ten movements of the arms; but had not described them.]

(2) Four movements of the wrists :

-

- Akuncita (moving out);

- Nikuncita (moving in);

- Bhramita (circular); and,

- Sama (natural).

[Bharata had not mentioned wrist positions and movements separately; but had dealt with them under Nrtta-hasthas.]

(3) Three groups of hand (Hastha-bheda) gestures are: twenty seven single hand gestures (Asamyuta-hastas); thirteen gestures of both the hands combined (Samyuta-hastas); and twenty four Nrtta –hasthas. The three together make sixty-four hand gestures.

[The movements of the hands (Hastha) are discussed in detail both in the Natyashastra and in the Nrtya-Vinoda. Bharata had included the hand-gestures under the category of Anga (major limbs); while Someshvara brought them under Pratyanga (minor limbs). The number of hand-gestures and the composition each of the three varieties does vary; but, the total number of hand-gestures, in either of the texts, is sixty four.

However, the names and uses of many Hasthas of Nrtya Vinoda differ from those listed in the Natyashastra.

For instance; Someshvara does not mention the single-hand gestures Lalita and Valita; as also the Nrtta-hastha Arala. He substitutes them by other Hasthas. And, in the case of Musti, he includes an additional type of Musti, where the thumb is beneath the other fingers. And, in certain instances, Somesvara goes further than Bharata, by giving the exact positions of the fingers, while describing a hand-gesture; as in Ardhacandra, Mrgasira and Padmakosa.

Bharata had stated that the hand-gestures and their use, as mentioned by him, are merely indicative; and, it is left to the ingenuity of the performer to improvise, to convey the intended meaning. Such possibilities, he said, are endless. Someshvara also made a similar remark.]

Both the authors – Bharata and Someshvara- describe four categories of the Karanas of the hand: Avestita, Udvestita, Vyavartita and Parivartita.

These gestures also associated with Nrtta-hasthas, in their various movements, when applied either in Dance or Drama, should be followed by Karanas having appropriate expression of the face, the eyebrows and the eyes.

(4) Seven movements of the knees (Janu) are :

-

- Unnata (raised);

- Nata (lowered);

- Kuncita (bent);

- Ardha-kuncita (half bent);

- Samhata (joined);

- Vistrtta (spread out; and

- Sama (natural).

[Natyashastra doesn’t analyze movements of the knee (janu), the anklets (gulpha) and the toes of the feet; as is done by other texts. But, it described the five shank-movements, as arising out of the manipulation of the knees.]

(5) Five movements of the shanks (Jangha) are :

-

- Nihasrta (stretched forward);

- Paravrtta (kept backwards),

- Tirascina (side touching the ground),

- Kampita (tremulous) and

- Bahikranta (moving outwards).

[But these do not resemble any of the shank movements found in the Natyashastra. Someshvara might have taken these movements from some other text. The five movements of the shanks (Jangha) as mentioned in the Natyashastra are: Avartita (turned, left foot turning to the right and the right turning to the left); Nata (knees bent); Ksipta (knees thrown out); Udvahita (raising the shank up); and, Parivrtta (turning back of a shank)]

(6) Nine movements of the feet (Pada-bheda) are:

-

- Ghatita (striking with the heel);

- Ghatitotsedha (striking with the toe and heel);

- Mardita (sole rubbing the ground);

- Tadita (striking with toes);

- Agraga (slipping the foot forward),

- Parsniga (moving backwards on the heels);

- Parsvaga (moving with the sides of the feet);

- Suci (standing on the toes) ; and

- Nija (natural).

Along with the movements of the feet five movements of the toes are described namely :

-

- Avaksipta (lowered);

- Utksipta (raised),

- Kuncita (contracted);

- Prasarita (stretched); and,

- Samlagna (joined).

The Natyashastra does not specifically discuss the toe movements.

[Natyashastra had described five kinds of feet positions: Udghattita; Sama; Agratala-sancara; Ancita; and, Kuncita.

Agraga and Parsvaga, the two feet movements indicated by Someshvara were not mentioned by Bharata.

There is one major difference between these two sets of feet movements. In the Natyashastra the feet movements indicate floor contacts and placing the feet in a particular position. But in the Nrtya-Vinoda, except for Suci and Nija, all other feet movements, consist of actual movements, which arise out of the combinations of the basic feet positions, as mentioned by Bharata.

For example, Ghatita, Ghatitotsedha, Tadita and Parsniga are all combinations of Ancita and Kuncita feet positions. And, Suci and Nija are only static positions. They correspond to the descriptions of Samapada and Sama respectively, as given by Bharata.]

Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas

After an analysis of Angika Abhinaya, the Nrtya Vinoda takes up the discussion of Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas.

The Nrtya Vinoda discusses in all, Twenty one Sthanakas; Twenty six earthly (Bhuma) Caris and Sixteen aerial (Akasaki) Caris; and Eighteen Karanas.

Sthanaka is a motionless posture; a Cari is the movement of the lower limbs, which starts from one Sthanaka position and ends in another. A Karana, on the other hand, relates to the sequence of static postures and dynamic movements. Thus, the Sthanaka and the Karana are associated with the movements of the entire body; and, the two are interrelated.

The Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas were also discussed by Bharata in his Natyashastra. But, the Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas as enumerated by Someshvara differ from those described by Bharata. Those

Since the two sets of Dance-features differed significantly, the later writers, in order to distinguish the two, classified the ones described in Natyashastra under the Marga class; and, those in the Nrtya Vinoda under the Desi class.

But, Somesvara had not qualified such dance features enumerated by him in the Nrtya Vinoda with the suffix ‘Desi’. He had merely stated that he will disregard the features (Lakshanas) as defined by Bharata; and will deal only with those that were developed during the current times and those that are still in practice (Lakshya).

Some scholars opine that the Desi Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas of Someshvara could very well be treated as additions or supplements to the Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas defined by Bharata.

The term Desi, in the context of dance, stands for all those Dance techniques, postures and movements that were not mentioned in the Natyashastra, the seminal work of Bharata. Desi was used in contrast to the Marga or the classic tradition of Bharata.

And, Desi also meant those Dance-forms and movements that were created in various regions of the country for the pleasure and entertainment of the common folks. They even varied from region to region; and, in that sense the Desi could even be called ‘local-styles’. In the post-Bharata times, many other movements were created and were codified as Desi varieties.

Such Desi Dances were, usually, spontaneous and free-flowing, not restricted by the regimen of strict rules of a particular tradition. Further, the rhythmic, agile feet and body movements, innovative gestures; and entertaining dance sequences performed with joy and jubilation characterize the Desi Dance. And, there is not much emphasis on Abhinaya through eyes or facial expressions.

Over a period of time, say by the time of Somehsvara (12th century) the Desi styles gained more ground and popularity. And, that is reflected by the number of works of the medieval times that gave greater prominence to Desi elements. The Nrtya Vinoda of King Someshvara also could be placed in that context.

As mentioned, a Sthanaka is a static posture, in which greater importance is assigned to the position of the legs. Here, the limbs are at a state of rest and harmony. Perfect and balanced disposition of the body is an essential feature of the Sthanaka. In dance, it is employed to precede and succeed any flow of the sequence of movement; as well as to portray an attitude. The dancer starts from one position to make a sequence of movements which end, in the same, position with which the dancer started, or in some other position. When the sequences are many and at a fast pace the postures may however get eclipsed.

The definitions of the Sthanakas as rendered by Someshvara relate exclusively to the position of the lower limbs; and, they do not describe the carriage or the relative disposition of the upper limbs. This signifies that the upper limbs including the hands could be used in any manner that is appropriate. Further, unlike Bharata, Someshvara does not categorize the Sthanakas into Purusha (male) and Stri (female) Sthanakas.

Of the twenty one Sthanakas described in the Nrtya Vinoda, only two bear the same names of two Margi Sthanakas. They are Samapada and Vaisnava Sthanakas.

The Vaisnava Sthanakas in both the traditions are similar. But, the Samapada Sthanaka of the Desi style differs from the Samhata Sthanaka of the Margi tradition.

The Cari constitutes the simultaneous movement of the feet, shanks, thighs and hips. They are classified into two groups: one in which feet do not loose contact with the floor; and, the other in which the feet are taken off the ground.

The Nrtya Vinoda mentions Twenty six earthly (Bhuma) Caris and Sixteen aerial (Akasaki) Caris

The earthly Caris consist of movements of the 1eg as a whole, in which the feet are normally close to the ground. There are however two exceptions to this rule found in the Harinatrasika and the Sanghattita Cari, which replicate the leaping movements of a deer.

The aerial (Akasaki) Caris comprise of the movements of the legs which are lifted or stretched up in the air. Some of the names of the Desi – Akasaki – Caris are to be found in the Margi tradition as well. They are Urdhva-janu (uplifted knees); Suci (pointed); Vidhyut-bhranta, (alarmed by lightning); Alata (square position); and, Danda-pada (as if punishing).

Towards the end, the Nrtya Vinoda describes Eighteen Karanas. Such Desi Karanas, as described by Someshvara, are merely agile movements involving Jumps and leaps. Therefore, the later writers designated such Desi Karanas as Utpluti Karanas.

Since, Someshvara focused on the Dance-forms that were alive and in practice during his time, he made no effort to restore the 108 Karanas, most of which had gone out of use by then. Similar was the case with the Angaharas, Recakas and Margi-Caris, which perhaps were rather distant from the people of his time; and, not in active practice.

The use of these leaping Karanas are said to employed, especially, in the Laghu or Laghava and Visama Nrtya, which involve acrobatics . They range from the simple and ordinary jumps like the Ancita Karanas to very dextrous and nimble foot-movement like the Kapala-sparsana (bringing a foot very close to or touching the cheek)

To sum up

The Nrtya Vinoda soon gained the status of an authoritative text; and, esteemed scholars and commentators – especially Sarangadeva and Jaya Senapathi- quoted from it extensively.

To sum up, the significant features of the Nrtya Vinoda are:

(1) Importance assigned to Desi forms of Dance, which were in active use, and their techniques; and, introducing Desi Sthanakas, Caris and Karanas.

(2) Bringing together various dance forms under the common term Nartana; and, coining the descriptive terms Laghava, Visama and Vikata.

(3) Re-classification of the body-parts: Anga, Upanga and Pratyanga. And , including the descriptions and uses of additional limbs such as shoulders, wrists, knees, teeth and tongue.

(3) The descriptions of certain types of movements that were not mentioned in the Natyashastra. These include,

belly-movements (Riktapurna);

Lip-movements (Mukula, Kunita, Ayata, Recita and Vikasi);

Arm –movements (Sarala, Pronnata, Nyanca, Kuncita, Lalita, Lolita, Calita and Paravrtta);

Leg-movements (Ghattita, Ghatitosedtaa, Tadita, Mardita, Parsniga, Parsvaga, and. Agraga); and,

five movements of the toes.

(4) Coordinating eye-glances with the transitory states (Sanchari-bhavas)

(5) And, suggesting variations in the execution on and uses of Nrtta-hasthas.

**

For these and other reasons, the scholars recommend that the Nrtya Vinoda could be gainfully used as a supplement to the study of Natyashastra and of the Sangita-ratnakara. The Nrtya Vinoda could also serve as a link that bridges the scholarship of the ancients and the practices prevalent among common people of the medieval times. That would help to gain an overall view of the progress and development of the Dance traditions of India, over the centuries.

In the Next Part , we shall move on to another text.

Continued

In

The Next Part

References and Sources

- Movement and Mimesis: The Idea of Dance in the Sanskritic Tradition by Dr Mandakranta Bose

- https://archive.org/details/TxtSkt-mAnasOllAsa-Somesvara-Vol3-1961-0024b/page/n128

- A critical study of nrtya vinoda of manasollasa V,Usha Srinivasan

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/59351/9/09_chapter%203.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/59351/10/10_chapter%204.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/59351/11/11_chapter%205.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/59351/12/12_conclusion.pdf

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/59351/6/06_synopsis.pdf

- https://nartanam.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/vol-xvii-no-iv-final.pdf

- http://www.worldlibrary.org/articles/someshwara_iii

- ALL IMAGES ARE FROM INTERNET

As a part of her preparation, the dancer should offer her respects to the well-shaped dainty (Surupa) little (Sukshma) ankle-bells (Kinkini) made of bronze (Kamsya-racita), giving pleasant sounds (Susvara), with insignia of the presiding star-deities (Nakshatra-devata), and tied together with an indigo string (Nila-sutrena). Before wearing the anklet-bells, the dancer should reverently touch her forehead and eyes with them; and repeat a brief prayer (AD.

As a part of her preparation, the dancer should offer her respects to the well-shaped dainty (Surupa) little (Sukshma) ankle-bells (Kinkini) made of bronze (Kamsya-racita), giving pleasant sounds (Susvara), with insignia of the presiding star-deities (Nakshatra-devata), and tied together with an indigo string (Nila-sutrena). Before wearing the anklet-bells, the dancer should reverently touch her forehead and eyes with them; and repeat a brief prayer (AD.

Abhinavagupta, in his typical style, provides a totally different sort of explanation to the term Tandava. According to him, the term Tāṇḍava is derived from the sounds like ‘Tando; tam-tam’, produced by the accompanying Damaru shaped drums. It follows the manner, in Grammar (vyākaraṇa), of naming an object, based on the sound it produces – śabda-anukṛti.

Abhinavagupta, in his typical style, provides a totally different sort of explanation to the term Tandava. According to him, the term Tāṇḍava is derived from the sounds like ‘Tando; tam-tam’, produced by the accompanying Damaru shaped drums. It follows the manner, in Grammar (vyākaraṇa), of naming an object, based on the sound it produces – śabda-anukṛti.