Sharo

Dear Sir,

What you have to say about ‘naga’ (snake god) worship in Hinduism. Which scriptures mentioned about ‘naga’? Please provide some detailed explanation. Any books to read to get more details?

***

The serpent lore

In the ancient Indian symbolisms, the tree and the serpent are twin spirits. And, the two have close association with the mountains*. The big trees that populate the hills are the natural abode of the serpents that move around freely amidst the branches and the foliage of the giant trees. The seals of the Indus valley excavated from the sites in Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro also depict close association of trees with the serpents.

[*The Sanskrit expression ‘Naga’ has a dual connotation as: serpent and mountain. Naga is also a term that is often used in Indian literature to denote a distinguished person (nagadhipati); a city (nagara); a precious stone (nagamani); a flower (nagamalli); and, Indra’s elephant (nagendra).]

Apart from the trees and mountains, the domain of the serpents is also said to be the enchanted underworld, the realm of the Naga-loka or Patala-loka, ruled by King Vasuki, the Nagaraja. It is described as an immense province , with its Capital at Bhogavati, crowded with palaces and mansions; and, filled with precious gems (nagamani), jewels, gold, other treasures and with various other types of riches.

Srimad Bhagavata Purana (5.24.31) describes the nether land known as Pātāla or Nāgaloka, where there are many demoniac serpents, the masters of Nāgaloka, such as Śankha, Kulika, Mahāśańkha, Sveta, Dhanañjaya, Dhritarashtra, Śańkhacūda, Kambala, Aśvatara and Devadatta. The chief among them is Vāsuki. They are all extremely angry, and they have many, many hoods —some snakes five hoods, some seven, some ten, others a hundred and others a thousand. These hoods are bedecked with valuable gems; and ,with the light emanating from the gems.

Tato’ adhastat patale naga loka patayo vasuki-pramukhah; sankha-kulika mahasankha-sveta-dhananjaya-dhrtarastra-sankhacuda-kambalaasvatara devadatta -adayo maha bhogino mahamarsa nivasanti yesam u ha vai panca sapta sata sahasra sirsanam phanasu viracita maha-manayo rocisnavah patala vivara timira nikaram sva rocisa vidhamanti

Srimad Bhagavatha Purana (11th Chapter, 12th Skanda) mentions the names of the Nagas associated with each of the months in a year.

The serpents are also often associated with bodies of waters — including rivers, lakes, seas, and wells — and are also regarded as the guardians of treasures. However, the favorite place of dwelling of the serpents is said to be the ocean, which is described as the ‘the abode of the Nagas ‘(Naganam aalayam).

They are embodiments as also the custodians of terrestrial waters. The Nagas are creatures of abundant power who defend the underworld; confer fertility and prosperity upon those who are associated with them ; be it a meadow, a shrine, a temple, a person , or even a kingdom.

Thus, the Nagas are, virtually, almost everywhere – below the ground; under the sea; in the lakes and springs; on the mountains; on the trees; in the borrows; and, even in the skies.

Ancient Indians both feared and revered the snakes, as they were seen to be associated with power, fear and deference. The Snakes are always looked upon , in every culture over the generations, as mysterious, dangerous, unseen and unacceptable within human habitats. And yet, there has always been a strange kind of fascination towards those meandering coldblooded reptiles.

[India, somehow, has since acquired the dubious distinction of being the ‘snake-bite-capital’. Please check here. It is said; an international team, comprising several Indian researchers has since reported high-quality sequencing of Indian Cobra genome, unlocking the secret code of its ‘venome-ome’ that carries 139 genes, out of which 19 are linked to venom-specific toxins> It is believed; the finding may help save thousands of lives in future as it opens up the doors to create better quality anti-venoms in the laboratory using recombinant DNA technology. ]

Apart from being symbols of fertility, the serpents have deep religious significance. The serpent lore in India is not only vast and varied, but is also very old and persisting. After the cow, the snake was perhaps the most revered animal of ancient India. Legendary serpents, such as Sesha and Vasuki , lent the snake a certain prestige,

Even as early as in the first century, Huvishka , the Scythian (Kushan) emperor , had erected a stone sculpture of a hooded serpent, with the inscription “propitiation to the worshipful Naga” (Priyatti Bhagava Naga). That was to mark the consecration of a tank and a garden dedicated to Bhagavat Bhumi Naga.

The practice of erecting such Naga-slabs, for worship, must have been in vogue even during much earlier periods. There was also the practice of erecting Naga-kastha (a pole with a snake shaped logo at the top), to mark the occasion. There are, of course, plenty of references to snake-worship in the Hindu and the Buddhist mythologies.

That tradition still continues. Hindus worship snakes in temples as well as in their natural habitats; offering them milk, incense, and prayers.

The Snakes seemed to have secured a powerful hold upon the imagination of people, prompted by the several characteristics associated with this creature. There was a great allure towards snakes; the mysteries they hold; and the symbolisms the project.

The snake, undoubtedly, is a unique creature. It is decidedly un-human (a-manusha); yet, exhibiting a bewildering blends of human and serpentine uncanny powers. It is also unlike any other animal; because of its peculiar shape and its distinctive ability to move swiftly, in mysterious gliding motion, without the aid of limbs or wings. Further, it is the power of their unblinking mesmerizing eyes that holds one spellbound.

The other characteristic features of snake are its forked tongue; and, the periodical casting of its skin, rejuvenating itself, each time. The practice of shedding its skin, from time to time, suggested longevity or even immortality of the snakes. It also suggested a sense of freeing oneself from the evil of ignorance and progressing towards attaining freedom from mundane existence.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (4.4.7) remarks : ‘Like a Snake’s skin, dead and cast off, lies upon an ant-hill, likewise lies his body; but that which is body-less, immortal and life, is pure Brahmana, is pure light. ’

yadā sarve pramucyante kāmā ye ‘sya hṛdi śritāḥ | atha martyo ‘mṛto bhavaty atra brahma samaśnuta iti | tad yathāhinirlvayanī valmīke mṛtā pratyastā śayīta | evam evedaṃ śarīraṃ śete | athāyam aśarīro ‘mṛtaḥ prāṇo brahmaiva teja eva | so ‘haṃ bhagavate sahasraṃ dadāmīti hovāca janako vaidehaḥ || BrhUp_4,4.7 ||

These fabulous beings are also believed to have the power of speech. Therefore, the serpents came to be invested with divine wisdom.

Thus, the serpent, by all accounts, is indeed, the uncanniest of all creatures. Above all, it is the deadly venom they hold and inject that causes the whole species to be looked upon as dreaded beings that are to be feared, respected and worshiped. There is always an aura of mystery surrounding the snakes.

Patrick Russell (6 February 1726, Edinburgh – 2 July 1805, London) was a Scottish surgeon and naturalist who worked in India.

As a physician, as well as a naturalist to the East India Company in the South India, he was concerned with the problem of snakebite; and , he made it his aim to find a way for people to identify venomous snakes. Russell, therefore, attempted to classify the snakes using the nature of scales; and, studying their characteristics. With this, he hoped to find an easy way to separate the venomous snakes from the non-venomous ones. Apart from that; he conducted experiments on dogs and chicken and described the symptoms. He tested remedies claimed for snakebite.

Because of the detailed studies he undertook on the snakes of South India, Patrick Russell is considered the ‘Father of Indian Ophiology’ (the branch of zoology that deals with snakes). Russell’s viper, Daboia russelii, (a species of venomous snake) is named after him.

Some of his papers were collected and published as : An Account of Indian Serpents – Collected on the coast of Coromandel : containing descriptions and drawings of each species, together with experiments and remarks on their several poisons; Illustrated By Patrick Russell (1727-1805), East India Company; Printed by W. Bulmer & Co., London – 1796

This volume features the details of 42 poisonous and non-poisonous snakes found in Southern India; their biological and native names; their physical features; eyes, fangs, teeth; average lengths, sizes; color ; scales; their habitats; their characteristics. In addition, Patrick Russell provides his own observations on the selected species along with their drawings.

The allure of the silent creeping creatures is so great that the Amarakosha (1,8; 6-8), the Indian lexicon – dated around 400 AD – has as many as thirty-three synonyms for a serpent; and, in addition it names varieties of snakes .

## Snake or serpent (33) ##

(1.8.497) sarpaḥ pṛdākurbhujago bhujaṅgo ‘hirbhujaṅgamaḥ

(1.8.498) āśīviṣo viṣadharaścakrī vyālaḥ sarīsṛpaḥ

(1.8.499) kuṇḍalī gūḍhapāccakṣuḥśravāḥ kākodaraḥ phaṇī

(1.8.500) darvīkaro dīrghapṛṣṭho dandaśūko bileśayaḥ

(1.8.501) uragaḥ pannago bhogī jihmagaḥ pavanāśanaḥ

(1.8.502) lelihāno dvirasano gokarṇaḥ kañcukī tathā

(1.8.503) kumbhīnasaḥ phaṇadharo harirbhogadharastathā

King of snakes and types of snakes

(1.8.493) śeṣo ananto vāsukistu sarparājo ‘tha gonase

(1.8.494) tilitsaḥ syādajagare śayurvāhasa ityubhau

Water snakes and non-poisonous snakes

1.8.495) alagardo jalavyālaḥ samau rājilaḍuṇḍumau

(1.8.496) māludhāno mātulāhirnirmukto muktakañcukaḥ

## Body of a snake (1), Fang (2), Pertaining to a snake (1), Hood of a snake(2) ##

(1.8.504) aheḥ śarīraṃ bhogaḥ syādāśīrapyahidaṃṣṭrikā

(1.8.505) triṣvāheyaṃ viṣāsthyādi sphaṭāyāṃ tu phaṇā dvayoḥ

These include terms such as: Bhujaga; Bhujanga; Bhujamgama; Bhogin; Pannaga; Uraga; and, Jihamaga, all of which refer to the animal’s peculiar way of moving , creeping on their chests. There is also a belief that a snake has hidden legs (guptapada).

The curious way in which the snake protrudes its tongue, as if licking or tasting the air , earned it names such as : Lehiha , Lelihana (licker); Dvi-jihva, Dvi-rasana (Double-tongue); and, Vayu-bhakshaka, Vatasin,Pavanasin, Pavanabhuj, Anilasana, Svanasana, marutasana (all suggesting that snakes feed on the wind – the wind-eater).

According to the Nāṭyaśāstra 3.40-44 gods and demigods should be worshiped before the commencement of the play. In that context, the prayer submitted to the Nagas avers: “I bow to all the Pannagas of the nether region, who are devourers of wind, grant me success in the drama we are about to produce.” ‘

Rasātala-gatebhyaśca pannagebhyo namo namaḥ | diśantu siddhiṃ nāṭyasya pūjitāḥ pāpanāśanāḥ ||

There was a belief that while it inhales, it also sucks in the poisonous elements in the air; and, thus the snakes are said to aid in purifying the atmosphere.

They also protect the environment and the crops from the menace of the rodents. An indiscriminate killing of snakes, will surely lead to severe ecological imbalance.

The snake has acquired some curious names, inspired by its shape, such as: Dantavati rajju (toothed-rope); Putirajju (putrid-rope); Dhirga-Jathika (the long one) and Nikkamaitva (biting-rope).

Apart from the synonyms which have reference to its peculiar shape, the snakes have some others, which are obliquely related to its qualities – either observed or merely ascribed to it by popular belief or by false notion.

For instance, the absence of external organs of hearing led to the strange belief that the snake can hear through its eyes. And, hence it was called Chakshu-sravas (hearing-by-sight).

There is also a belief that the snakes enjoy listening to music, though they have no external ears; particularly the music played by the snake-charmer on the Been, a folk wind-instrument.

They are said to be greatly attracted by the strong fragrance of the Champaka flowers (Michelia champaca).

The hood of a snake is variously denoted by words such as Phana, Phata, Sphata, Phuta and Dravi (like a ladle or a spoon). Following that; a snake is often referred to Phani or Dravi. The Naga, the hooded cobra, is regarded as the king of snakes (Phanindra).

The Nagas are said to be adorned with half-Swastika (auspicious mystic cross). It is explained that the marks on the back of the hood resembling spectacles may possibly be such Svastika-ardha (half-Swastika).

There is also a belief that serpents grow to such huge size as to be able to devour goats ; and, hence are called Ajagara.

As the guardians of hidden treasures, they are also said to posses various priceless magical gems (Naga Mani) and other objects of wealth. Thus the possession of treasures, magical gems and spells has come to be regarded as a trait of the Nagas.

The Nagas are said to be endowed with the magical powers of assuming various forms (iccha-dhari Naga). Because of its such powers, the snake is regarded with awe and veneration.

The Nagas are also said to know magical spells, which they impart to the devoted worthy recipients.

The mythical cosmology of ancient India believes that the Earth, on which we live, is held and supported by the enormous thousand-headed serpent, Sesha. He is described as ‘one whose thousand hoods are the base of the world , carrying the load of the orb of the earth ; and, spreading good qualities

(sakala –jagan-mulo-vichakra –mahabhara –vahana-guna-vamana –phana –sahasra).

There is also a close connection between the sacred Naga and the ant-hill. It is looked upon not only as holy abode of the Naga; but, also as the entrance to the mysterious world of snakes (Naga-loka; or Patala), far below the world of humans.

Some mention of a connection between rainbow (Indra-danush) and the anthills (Valmika) where the Nagas reside. Varahamihira, the mathematician (505–587 CE), and Kalidasa (Meghaduta stanza 15) the great poet – Ca. 4th–5th century CE – speak of rainbows that issue forth from the top of the anthill – valmīkāgrāt prabhavati dhanuḥkhaṇḍam ākhaṇḍalasya .

Some have tried to explain saying that such phenomenon could possibly occur when the evening sunrays fall on crest jewel atop the hood of the great Nagas, emerging out of the anthill.

There is a rampant belief that snakes drink milk. The cobras are therefore worshiped with milk-offerings, specially on Nag Panchami day . But, in fact, the snakes , which are reptiles, have no mammary glands; and, therefore, cannot digest milk. Some have expressed the fear that consuming milk is harmful to the snakes; and, might even cause death.

There is a belief that snakes use their tails as a whip; and, the green snakes aim at the eyes of humans.

There are myths that assert that a cobra nurtures a grudge against an injustice meted out to it ; and, might even wait up to twelve years to take its revenge .

The snakes are symbolically related with Astrological formations. The planet Rahu is identified with the head of the snake; while , Kethu is identified with the snake’s tail. And, when the other planets in the horoscope fall in between these two, then it is said to give rise to the inauspicious Kaala Sarp Dosha; which , it is feared , can wreak havoc in one’s life . A set of special prayers and rituals are recommended to get rid of the ill effects of this Dosha.

While the animal is dreaded on one side, it is admired on another side.

Since there is a faith that the snakes are associated with gods, ancestors (Pitris) and other super-beings, they are even called Deva-jana (god-people). They are mentioned along with other celestial beings, such as: Devas, Gandharva, Apsaras, Yakshas and Pitras (manes).

On the other hand, the most dreadful and awesome attribute of certain varieties of snakes is their lethal power to inflict sudden death . by injecting deadly poison.

The Amarakosa lists nine types of snake venoms (viṣabhedāni nava) :

(1.8.506) samau kañcukanirmokau kṣveḍastu garalaṃ viṣam

(1.8.507) puṃsi klībe ca kākolakāla-kūṭa-halāhalāḥ

(1.8.508) saurāṣṭrikaḥ śauklikeyo brahmaputraḥ pradīpanaḥ

(1.8.509) dārado vatsanābhaśca viṣabhedā amī nava

This has given rise to many superstitions. And, its destructive power is compared to that of the all-devouring fire, the Agni or Tejas. There is also a belief that through the mere fiery blast of his nostrils (Nasavata, Nasikavata) an angry Naga can cause destruction. Such ill-wind could also pollute the air and bring about diseases (Ahi vataka roga).

There is also a fear that a snake could kill merely through the power of its poisoned sight (Visha drsti).

At the same time, it is believed that, by nature, the serpents are benevolent; but, they can turn out to be destructive and vengeful, if disrespected or not treated well

Despite the array of its horrific attributes, what is remarkable is that the snake, a deadly reptile, has come to be looked upon with great awe as the titular deity of the house (Vastu sarpa) ; and, as a harbinger of good luck and prosperity.

Having said that; it is not the snake, in general, that is offered worship. But; it is the Naga, the cobra – raised to the rank of a divine being – in particular that is worshiped in large parts of India.

Even today, the Indian women desirous of begetting offspring do worship Naga or its replica, in hope and reverence. Killing or even harming a Naga (cobra) is dreaded as the deadliest of the sins. It is feared that the wrath of the serpents would haunt generation after generation. The remedial rituals are quite elaborate.

It could be said ; while the Major gods and the Devi are worshiped in order to attain salvation (Moksha), release from ignorance and freedom from the attachments of earthly coils ; the Nagas are propitiated for practical purposes, such as to avoid their malevolent actions; to seek their blessings either to beget progeny or to secure health and wealth ; to ward off evil effects; and, also for protection against drought and such other disasters.

[For a study on the practice of worship of snakes in Southern India – please click here]

Symbolisms

The Nagas enjoy a prominent place in Indian legends and folklore. A range of symbolisms are associated with serpents.

For instance; Anantha or the Adi-Sesha represents both the timelessness and the primal energy (mula-prakriti), reposing, at rest, prior to the manifestation of the created world.

A snake (sarpa) coiling around the drum held by Sri Dakshinamurti is said to symbolize Tantric knowledge.

In the Yoga tradition, the Kundalini Shakthi, the energy at the base chakra (the Muladhara) is represented as a coiled serpent, just about to uncoil. As the Kundalini gets awakened; and as it begins to move up, the serpent gradually ascends through the higher chakras, until it reaches the highest chakra, the Sahasrara.

The Kundalini Shakhty, human energy, in its latent state, is pictured as a resting coiled serpent. And, when it is awakened and when it actively moves up , it is said to take the form of spirals resembling Naga-bandha, the intertwining of two vibrant cobras . Later, the Naga-bandha also came to be viewed upon as the symbol of dynamic movement of the ethereal or cosmic forces; and, also as the male and the female energies representing the transmission of the positive and negative charges in the universe; thus enlivening all existence.

The Kundalini Shakhty, human energy, in its latent state, is pictured as a resting coiled serpent. And, when it is awakened and when it actively moves up , it is said to take the form of spirals resembling Naga-bandha, the intertwining of two vibrant cobras . Later, the Naga-bandha also came to be viewed upon as the symbol of dynamic movement of the ethereal or cosmic forces; and, also as the male and the female energies representing the transmission of the positive and negative charges in the universe; thus enlivening all existence.

*

The caduceus is the traditional symbol of Hermes; and, it features two snakes winding around an often-winged staff. It is often used as a symbol of medicine; and, of life.

**

And, in the Yoga-practices, the Bhujanga-asana, the posture resembling a cobra with its hood raised and bent back, represents the dual serpentine energy emanating from Bhuja its circular coils; and , Anga, the limb-like, linear form it assumes when extended .

As the Yogi straightens the arms, lifts the upper body and throws back the head while performing the Bhujanga-asana, her/his spinal curve is believed to stimulate the movement of Prana (life force) within the body ; her/his chest expands and fills the lungs with vitality ; and, the heart throbs evenly , energizing the whole of the body-mind complex.

The serpents, strangely, symbolize both Life and Death. Prana, the vital breath, that keeps the body alive is compared to a serpent. Just as a snake moves in the passages below the earth, the Apana, the outward breath, moves through various channels and exits through the holes in the body. It is the Apana that ensures distribution of vital energy to every segment of the organs in the body.

And, when the Apana (the Prana-vayu) departs from the body, the body dies. That is death, the Kala – the end of one’s time on earth. The serpent as Kala, the Time, devours everything (sarva-bakshaka); all this existence is its food.

The Snake primarily represents rebirth, death and immortality. And, due to its ability to cast off its skin from-time-to-time, it is said to be being symbolically ‘reborn’, each time.

The serpents also represent Kama, the desires and cravings, which drive the beings in this world. It is the motive forces that propel life.

The serpents , thus, summarily represent all aspects and processes that occur in one’s life cycle: creation; good fortune; misfortune; destruction; and death. The serpents also stand for the mysteries, the allures, the dangers as also the rewards in life.

Worship of the Nagas as per ancient texts

You mentioned about the practice of worshiping the Nagas; and, the related ancient scriptures.

Snake worship is a manifestation of one’s devotion towards the serpent deities. The tradition is present in several ancient cultures, religions and mythologies, where the snakes are regarded as entities of strength and rejuvenation. Worship of the Naga goes back to thousands of years.

As regards the Vedic texts, there is no direct reference to snake worship in Rig-Veda, the earliest of the four Vedas. Naga, the name by which the serpent-god became famous in the later texts does not appear in the early Vedic literature. Even when the term appears in Satapatha Brahmana (mahā-nāga-mivābhi-saṃsāraṃ –11.2.7.12), it is not clear whether it refers to a snake or to an elephant. Yet; the serpent as a symbol of life-energy appears at many places.

Here, in the Vedic lore, the serpent Vrtra or Ahi appears as a powerful rival to Indra, the King of the Devas. He lies around or under water. And, he seemed to have control over the waters in the havens and on the earth, alike. Later in the text, there is a reference to Ahi Budhnya, meaning – the serpent of the deep – ahir budhnyaḥ (RV_10,066.11c). Ahir-Budhnya , described as a deity of the mid-regions (Antarikshya), is variously associated with Visvedevas, Apam -Napat, Samudra, Aja-Eka-pada, and Savitri

.

.

And, Ahi Budhnya came to be particularly associated with Aja-Eka-pada, ‘the supporter of the sky, streams and the oceans’; and, with the thundering flood. And, Aja-Eka-pada was described as a kind of Agni, Apam Napatu, the raging fire in the ocean-waters. Aja-Eka-pada, in turn was associated with Rudra. That, it is surmised, might have laid the foundation for linking the Naga cult with Shiva.

śaṃ no aja ekapād devo astu śaṃ no ‘hir budhnyaḥ śaṃ samudraḥ | śaṃ no apāṃ napāt perur astu śaṃ naḥ pṛśnir bhavatu devagopā |RV_7,035.13a |

[The Zend Avesta mentions Azi, as the serpent chief.]

Amaravathi stupa

But, it is in the Yajur Veda; and, more particularly in the Atharvana Veda, you find several passages relating to serpent-worship.

In the Maitrayani Samhita (2.7.15) of the Yajur Veda, prayers are addressed to the snakes (Sarpa), which move along the earth, the sky and the heavens; and, which have made their abode in the waters. And, to the snakes which are the tree spirits; as also, to the snakes which are as bright as the rays of the sun – rocane divo ye vā sūryasya raśmiṣu.

namo astu sarpebhyo ye keca pṛthivīm anu / ye antarikṣe ye divi tebhyaḥ sarpebhyo namaḥ// ya iṣavo yātudhānānāṃ ye vanaspatīnām / ye ‘vaṭeṣu śerate tebhyaḥ sarpebhyo namaḥ // ye amī rocane divo ye vā sūryasya raśmiṣu / ye apsu ṣadāṃsi cakrire tebhyaḥ sarpebhyo namaḥ /

There are, of course, numerous interesting references in the Atharva Veda to the mysteries, powers, poisons and the healing remedies of the snakes. There are also several magical spells and charms to avert the dangers caused by the snakes. There are prayers that are submitted to the snakes, in order to solicit their protection against demons, as also against their own tribe. At the same time, there are charms to counteract the powers of the wicked snakes.

The Prayers seeking protection mention: Let not the snakes, Oh gods, slay our offspring, our people. What is shut together may it not open. What is open may it not shut together. Homage to the Devas. (It is interpreted; here, the terms ‘open’ and ‘shut’ refer to the jaws of the snakes.)

mā no devā ahir vadhīt satokānt sahapuruṣān | samyataṃ na vi ṣparad vyāttaṃ na saṃ yaman namo devajanebhyaḥ ||1|| namo ‘stv asitāya namas tiraścirājaye |(AVŚ_6,56.2c) svajāya babhrave namo namo devajanebhyaḥ ||2||saṃ te hanmi datā dataḥ sam u te hanvā hanū | saṃ te jihvayā jihvāṃ sam v āsnāha āsyam ||3|| (AVŚ_6,56.1)

In the Atharva Veda Samhita (7. 56.1) homage is submitted, in particular, to four types of serpents named: Tiraschiraji (cross-lined); Asita (black); Pridaku or Svaja (adder); and Babhru (brown) or Kanakaparvan.

These four are associated with the guardian deities (Adhipathi) of the four quarters of the space. Asita is associated with Agni as the warden (rakshitar) of the East; Tiraschiraji, with Indra, as the regent of the South; Pridaku with Varuna. as warden of the West; and, Kanakaparvan with Kubera, as the warden of the North.

tiraścirājer asitāt pṛdākoḥ pari saṃbhṛtam | tat kaṅkaparvaṇo viṣam iyaṃ vīrud anīnaśat ||AVŚ_7,56. |

The main remedies employed against snake-bite are herbs and charms; the secret of which is supposed to be held by the seers. But, in Atharva Veda (8.7.23) it is said that the snakes themselves have knowledge of the cure or a remedy for their poisonous bites. There is also a belief that the snakes themselves produce an antidote against their own poisons, perhaps on the principle that like-cures-like.

(AVŚ_8,7.23a) varāho veda vīrudhaṃ nakulo veda bheṣajīm | (AVŚ_8,7.23c) sarpā gandharvā yā vidus tā asmā avase huve ||23|

There are certain passages in the Taittiriya Brahmana (Kanda 3, Part 1, Anu 1, and Sloka 5) where the offering (havis) within the course of a Yajna are submitted to the divine serpents:

Idam sarpebhyo havirastu-justa / Asresa yesa manuyanti chetah //

Again, as per the passages in the Taittiriya Brahmana (Kanda 3, Part 1, Anu 4, and Sloka 7), during the course of the Asvamedha Yajna, offerings of ghee and barley are submitted to the serpents (Sarphebyam svaha) by the Devas , praying for their help (ashrebhyah) in subduing (upanayati) the Asuras.

Te Devah sarpebhyo ashreshabyo ajyo karmbham nirevapanna/ tanetabhireva devata abhirupanyan/ yetabhirha vai devata abhirudpatham brathruvyam upanayati/ ya yetena havisha yajate/ ya u chainadevam vede /strotra juhoti/ Sarphebyah svahai ashrebhyah svahai / dandasukebhyaha svaheti //7//

The Grihya-sutras also contain accounts of the Sarpa-bali, the annual rites (Yajus) conducted during the full moon of the first month of the rainy season and the full moon of Sravana the first month of winter (Sravana-nakshatrena-yukta pournamasi-sravani) , with the twofold purpose of honoring or gratifying the Nagas; and , the other for , warding off the evils caused by the snakes.

Baudhayana Grihya Sutra (3.10.6) mentions several serpentine deities that are to be propitiated on the occasion of the Sarpa-bali; and, these include Naga deities such as Dhrtarastra, Taksaka, Vaisalaki, Tarksya, Ahira and Sanda

It is in the Asvalayana Grihya Sutra, that the divine serpents have been for the first time termed as “Naga’. The Sarpa-Bali ritual or the offerings to the serpents are described

Here, in the Asvalayana Grihya Sutra(2.1.9), the divine snakes that dwell in different directions are divided into three groups – as those pertaining to the earth (Prithvi), the sky (Antariksha) and the heaven (Divya Desha) –

Ye sarpah Prithivyam , ye Antariksha , ye Divya Deshasthebhyam , imam bali , maharshebya imam bali upakaromiti.

In addition to the classification of the serpents chiefly based upon their habitation, there is also a classification made with reference to their color and to the celestial deities to whom they belong.

In the Paraskara Grihya Sutra, the Sarpa-devajna or the divine serpents are invoked and offered Payasa (sweet-syrup) ; and, are worshiped with flower garlands. Here, the Payasa is offered to gods and Nagas, alike : Indra, Aja-Eka-pada, and Ahir-Budhnya.

Payasam-Indra-Sarpayitva-a-pupanscha-a-pupah;stirtva-a-aajaya bhaga-vistva-a-a-jya-huti; juhoti-Indrayena-a-Ajapada-Ahir Budhnya-yaya-proustha-pada-abhyascheti–(Paraskara Grihya Sutra-Kanda 2; Ka,15; Sloka 2)

The Paraskara Grihya Sutra (2.14.9-10), while offering oblations onto the Yajna kunda, states: To the lord of the serpents belonging to Agni, of the yellowish, terrestrial ones; to the lord of the white serpents belonging to Vayu, of the aerial ones; to the lord of the over powering serpents belonging to Surya, of the celestial ones; and, to the firm one, the son of the Earth.

Among these, the white serpents (Sveta Naga), the sons of Vidarva, were regarded as the most powerful; and, capable of restraining the other serpents from causing needless harm .

*

A domestic ritual called Vastu-samana is prescribed by the Ghobila Grirhya Sutra in order to please the regents of the ten regions (Dasa Disha); to be performed at the time of entering a newly built house (Griha-pravesha). Among the ten regents to whom the Bali is offered, Vasuki is the regent of the downward region (Adho loka – Patala) – Vasukaya ity adhastad – (Gobhilya – 4.7.41)

References in Mahabharata

But, it is truly, in Mahabharata that the history of the Naga race initially gets elaborated. In the first major Canto of the Epic – Adiparva – the Slokas 657 to 2197 are devoted the history of the origin of the Nagas and of their progeny. It starts with the marriage of the sage Kashyapa with Kadru. She becomes the mother of as many as one thousand Nagas, who are the progenitors of the Naga race. The names of some of their principal descendents are mentioned as: Sesha, Vasuki, Airavata, Takshaka, Karkota, Kaliya, Aila, Elapatra, Nila, Anila and Nahusha; and so on.

The story of the Nagas (MB. 1-16,122) is intertwined with that of the sons of the sister of Kadru – that is, Vinata (who also was married to Sage Kashyapa) – the Garuda, the eagle, Suparna, race.

As per Mahabharata, the Suparna-s headed by Garuda were formerly servants of the Nagas. With the help of the Devas, Garuda succeeded in ending the slavery of his brothers and their tribe. And later, Suparnas became enemies of the Nagas (MB.1.3.159); and vowed to bring death and destruction on the snake-race (sarpa-kula). Thus, the sons of the two sisters, followed by their descendents grew into bitter enemies, recklessly determined to destroy each other.

Some scholars opine that a tribe called Suparna (to which Garuda belonged) was the archrival of the Nagas. The Suparna-s were probably falcon rising or falcon worshipping tribes

Later, in the Epic, there are more references to the Nagas. And, they are more closely associated with the Pandavas than with their cousins, the Kauravas.

It seems that when the Khandava forest near Hastinapur (near the present Delhi) was burnt down to make place for the new capital, the Naga race was rudely dislodged (Adi parva). Despite that, the Pandava branch of the Lunar race (Chandra vamsa) and the Nagas seemed to have had friendly relations. Later, Arjuna marries Ulupi, daughter of the Naga King, belonging to the race of Airavata. And, shortly thereafter he marries Chitrangada, daughter of another Naga King at Manipur.

But, the enmity between the Pandava and Naga races erupted into serious trouble when Parikshit, the grandson of Arjuna, was cursed by a sage to die of snakebite. Thereafter, Parikshit was bitten by Takshaka, a Naga said to be from the region of Takshashila. It was a city named after Naga King Takshaka Vaisaleya (Taxila, near Peshawar of the present-day), to the west of the river Vitasta (Jhelum); which, was said to be his abode.

In order to avenge his father’s death, Janamejaya, went on a killing spree slaughtering thousands of snakes. Naga race was almost exterminated by Janamejaya, the Kuru king, It is said; that massacre was halted by the intervention of Astika, a nephew of Vasuki, the serpent king of the Eastern Nagas.

.. In the Puranas

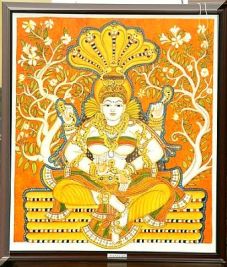

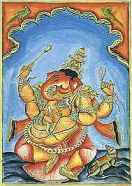

And, it was in the Puranas – mythological and often fanciful narrations – that the serpents came to be associated with numerous gods and goddesses, such as: Shiva; Vishnu; Ganapathi; Subrahmanya; Devi and others. In many of these cases, the serpent is an ornament, a weapon or a symbol of power or knowledge.

And, boy Krishna’s encounter with the river-snake Kalinga sarpa is , of course, depicted in countless manners through sculptures, paintings, Dance-dramas , songs etc.

The Puranas also mention several large serpentine deities like Kadru, Manasa, Vinata and Asitka. And, Vasuki the king of snakes played a vital role in the churning of the oceans. Several myths, beliefs, legends and scriptures are associated with snakes. And, the Snakes were used in warfare; and, snake poison was often used in palace intrigues.

You will find references to snake deities in both Hindu texts as also in the folklore. Even in Buddhism and Jainism there are abundant references to the practice of the worship of Trees and Serpents. Perhaps, the new religions absorbed the accumulated mass of the Naga-mythologies.

But, it is in the Vaishnava tradition that the serpent occupies a position of far greater significance. The Agamas mention eight lords of the Nagas; the chief of these being Ananta, Sesha or Adi-sesha. It is the Ananta, representing timelessness, on which the Lord Vishnu reposes, contemplating the creation of the world yet to come into existence. It was with the assistance of Vāsuki the King of Serpents that the ocean was churned; and, Amrita, the elixir, was produced, bestowing immortality to the gods (Deva). The other seven Nagas mentioned in the Agamas are: Vasuki; Takshaka; Karkotaka; Abja (Padma); Maha-bhuja; Maha-padma; Shankadhara; and, Kulika.

’Tree & Serpent Worship

Fergusson J, in his ’Tree & Serpent Worship, Or Illustrations of Mythology & Art in India’ (India Museum 1868), a remarkable work of research, studies the serpent-worship practices in several regions, under their varied the cultural and religious faiths. The study, apart from the Eastern countries like India, China, Ceylon and Cambodia; also covers parts of the western world such as : Egypt, Greece , Germany, France , and Scandinavian countries; as also Africa and Americas. Fergusson, in his Introductory Essay, writes:

The worship of the Serpent is not so strange as it might at first sight appear. As was well remarked by an ancient author (Sanchoniathon quoting Taatus ap Eusebium):

The serpent alone of all animals without legs or arms, or any of the “usual appliances for locomotion, still moves with singular celerity;” and he might have added — grace, for no one who has watched a serpent slowly progressing over the ground, with his head erect, and his body following apparently without exertion, can fail to be struck with the peculiar beauty of the motion. There is no jerk, no reflex motion, as in all other animals, even fishes, hut a continuous progression in the most graceful curves. Their general form, too, is full of elegance, and their colours varied and sometimes very beautiful, and their eyes bright and piercing. Then, too, a serpent can exist for an indefinite time without food or apparent hunger. He periodically casts his skin, and, as the ancients fabled, by that process renewed his youth. Add to this his longevity, which, though not so great as was often supposed, is still sufficient to make the superstitious forget how long an individual may have been reverenced in order that they may ascribe to him immortality.

Though these qualities, and others that will be noted in the sequel, may have sufficed to excite curiosity and obtain respect, it is probable that the serpent never would have become a god but for his exceptional power.

The poison fang of the serpent is something so exceptional, and so deadly in its action, as to excite dread, and when we find to how few of the serpent tribe it is given, its presence is only more mysterious. Even more terrible, however, than the poison of the Cobra is the flash-like spring of the Boa — the instantaneous embrace and the crushed-out life — all accomplished faster almost than the eye can follow.

It is hardly to he wondered at that such power should impress people in an early stage of civilization with feelings of awe; and with savages it is probably true that most religions sprung from a desire to propitiate by worship those powers from whom they fear that injury may be done to themselves or their property.

Although, therefore, fear might seem to suffice to account for the prevalence of the worship, on looking closely at it we are struck with phenomena of a totally different character.

“When we first meet Serpent Worship, either in the Wilderness of Sinaa, the Groves of Epidaurus, or in the Sarmatian huts, the Serpent is always the Agathodaemon, the bringer of health and good fortune.

He is the teacher of wisdom, the oracle of future events. His worship may have originated in fear, but long before we become practically acquainted with it, it had passed to the opposite extreme among its votaries. Any evil that ever was spoken of the serpent, came from those who were outside the pale, and were trying to depreciate what they considered as an accursed superstition.

If fear were the only or even the principal characteristic of Serpent Worship, it might he sufficient, in order to account for its prevalence, to say, that like causes produce like effects all the world over; and that the serpent is so terrible and so unlike the rest of creation that these characteristics are sufficient to explain everything.

When more narrowly examined, however, this seems hardly to be the case. Love and admiration, more than fear or dread, seem to be the main features of the faith, and there are so many unexpected features which are at the same time common to it all the world over, that it seems more reasonable to suspect a common origin.

In the present state of our knowledge, however, we are not in a position to indicate the locality where it first may have appeared, or the time when it first became established among mankind.

I would feel inclined to say that it came from the mud of the Lower Euphrates, among a people of Turonian origin, and spread thence as from a center to every country or land of the Old World in which a Turonian people settled. Apparently no Semitic, or no people of Aryan race, ever adopted it as a form of faith. It is true we find it in Judea, but almost certainly it was there an outcrop from the older under- lying strata of the population. We find it also in Greece, and in Scandinavia, among people whom we know principally as Aryan, but there too it is like the tares of a previous crop springing up among the stems of a badly-cultivated field of wheat.

The essence of Serpent Worship is as diametrically opposed to the spirit of the Veda or of the Bible as is possible to conceive two faiths to be; and with varying degrees of dilution the spirit of these two works pervades in a greater or less extent all the forms of the religions of the Aryan or Semitic races. On the other hand, any form of animal worship is perfectly consistent with the lower intellectual status of the Turonian races, and all history tells us that it is among them, and essentially among them only, that Serpent Worship is really found to prevail.

Snake Worship is general throughout peninsular India, both of the sculptured form and of the living creature. The sculpture is invariably of the form of the Nag or Cobra, and almost every hamlet has its Serpent deity. Sometimes this is a single snake, the hood of the Cobra being spread open. Occasionally the sculptured figures are nine in number, and this form is called the “Nao-nag,” and is intended to represent a parent snake and eight of its young, but the prevailing form is that of two snakes twining in the manner of the Esculapian rod.]

Worship practices in Indian traditions

The worship of the Nagas has taken a deep root in many of the Indian religions, for a variety of reasons. It could be either for fertility, protection, and eradication of poisons, securing or protecting hidden treasure or in repentance of past sins or to avert the anger of the snakes (Naga-dosha) or for whatever other reasons. Apart from the snakes, the goddesses such as Manasa Devi are worshiped with fear, hope and devotion. In South India, it is a common practice that women desiring to bear children set up Naga-stone-images (Naga shila).

As said, the Nagas, the cobras, have enjoyed a high status in Indian mythology and religious traditions. You will find numerous temples in South India dedicated to Snake-gods (Naga-devata). There are also special forest reserves for the Nagas (Naga-vana or Sarpa Kavu).

[Some say that the Nairs of Kerala were Nagavamshis or warriors following the serpent cult. The Naga worship among Nairs is widespread. Each Nair Tharavad or household had a separate place for Sarpa Kavu or a sacred grove dedicated to Nagas. Nair women also wore Naga-pada-thali or necklace with amulets in the shape of a cobra hood; and, also tied their hair into the front as a bun symbolizing the hood of a cobra. This is believed to be due to their affinity with the Naga serpent cult of the Nagavamshis.]

[ Shri Ajay Shetty, in his comments observes: In Tulu-nadu ( comprising Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts of of Karnataka and the Kasargodu region of Kerala) there is a special place for Naga worship. Before the commencement of any auspicious program, we first offer Pooja to the Naga; and, then to other deities. Even Bunts of Tulu-nadu belong to Nagavanshi clan. In each Bunt-tharavad, there is a Naga-bana. For the Tuluvas, Naga worship is most important. Naga is indeed the patron deity of Tuluvas. Many rituals like Ashlesha Bali, Dakke Bali, Sarpa Samskara, and Nagamandala are practiced even now. The process of worshipping Naga is called Nagaradhane .]

Here, in the South, the Naga is identified with Skanda or Subrahmanya; often depicted in serpentine shape, either entirely or is half-human. And, the sixth day of the lunar-month Shasti is regarded particularly sacred for worship of Subrahmanya. There are countless temples of Lord Subrahmanya in South India. Further, in the temples of other deities too, there would normally be snake-stones (Naga-shila) having images of snakes carved on them, placed on specially prepared platforms under the shade of a papal tree conjoined with a Margosa tree. And, in almost every part of India there are carved representations of cobras or Nagas.

[ For the purpose of offering worship to the Nagas , several Stotras and Namavalis have been composed . A few of the well known among those are :

Sri Subrahmanya Ashtottara Sata Namavali; Sri Naga Devata Ashtottara Shata Namavali ; Sri Naga Namavali (citing names of 78 revered Nagas) ]

On Naga Panchami, the fifth day of the bright half of Shravana (July-August), many Hindus visit temples specially dedicated to snakes and worship the snake, or Naga idols or the anthills. It is also the auspicious day on which the sisters affectionately greet their brothers and pray for their welfare .

In the Bengal region, the worship of the serpent-goddess Manasa Devi is widespread. Further, on the last day of the Bengali month of Shravana the Naga worship is celebrated as a religious festival.

[In the classical version, according to a Shilpa text Pratista-lakshana-Sara-samucchaya, ascribed to Vairochana (Ca.11th century) the Devi is known as Svangai or Sungai-bhattarika. It is said; it is in the Brahmavaivarta Purana, the deity came to be known as Manasa-Devi. The iconography (Prathima-lakshana) of Manasa-Devi describes her as a deity with two arms; seated in Lalita-asana; her right leg hanging down; and, the bent left leg resting on a huge lotus. She holds a fruit in the right hand; and, either a child or a snake in the left hand. A huge seven-hooded serpent serves as a canopy over her head. To the right of Manasa Devi , is sage Jaratkaru (husband of the goddess), who is shown as an ascetic with matted hair; and, to her left, is her brother Vasuki,under a snake-canopy. Manasa Devi’s son Astika sits on her lap.

]

There is a similar sculpture of the goddess Devi Svangai, Svangi, or Sungi-devi (Rangpur Museum) – shown here to your right. But, there are some variations. Here, to the right of the goddess, a male figure rides a donkey; holding a sword in the right hand and wearing high boots. He is identified as Nairutta; the guardian of the South-west . This figure is rather an unusual companion to the Snake-goddess. And, to the left of the goddess, another male figure is shown riding an antelope and holding a piece of cloth, indicating the movement of wind over his head. He is, identified as Vayu, the guardian of North-west .]

In the coastal regions of Karnataka, Naga Mandala, a unique, an elaborate and a complex ritual tribal dance-worship (Nagaradhane) sequences is performed with great pomp and fervour. The Mandala is the depiction of colourful design of a huge serpent coiled into numerous knots (pavitra). At the centre of the design is painted a small raised mound and a seven-hooded serpent. The ritual dance is performed, around the Mandala, by the priest possessed by the serpent-spirit (Naga-patri) to the accompaniment of music played by two musicians (Vaidya).The inspired Naga-patri dances with abandon mimicking the steps of an excited serpent. The ritual concludes with the possessed Naga-patri uttering oracle-like predictions; and, offering solutions to the problems and prayers submitted by the assembled devotees.

Iconography

The mythological serpent race that took form as cobras often can be found in Indian iconography. The Nāgas are described as the powerful, splendid, wonderful and proud semi divine race that can assume their physical form either as human, partial human-serpent or the whole serpent.

Therefore, the Nagas are invested with great importance; and, the Naga cult is depicted both in the Vedic and Buddhist texts as also in art, in myriad ways – as divine beings, humans and animals; and also as a blend of all these. A number or of Naga (male) and Nagi (female) deities are described in various texts; and, represented in images. Many of these form a part of the Hindu, Buddhist and Jaina pantheon, representing power, wisdom and fertility. For instance; you find abundant representations of the adoration of snake-deities on the Buddhist Stupas of Sanchi and Amravati. The Tibetan paintings depict the Buddha with the Naga coiled round him, seven times.

And,at the Wang Boran and Parsat Mai temple at Pattaya , Thailand there is a beautiful depiction of a Naga with his consorts. There is also a well sculpted image of Nagaraja at the Jetavana Buddhist vihara .

*

The serpent stones installed under the tree depict two serpents interlocked in an embrace. Sometimes, the serpents are shown as seated in the form of a Linga.

The simplest form in which the Naga appears in Indian art is the serpent form.

The mythical Adi-Sesha is celebrated with as many as one thousand hoods.

The female counterparts of the Nagas, the amorous and charming Nagini, are usually depicted with a crest consisting of a single serpent hood.

The iconography of the Nagas broadly fall into three types : as many headed serpents; as human or divine being characterized by five or seven serpent-hoods , each having two tongues; coiled into diverse kinds of knots.

And, there is also as the combination of the two with the upper part of human/divine being combined with the lower half of a snake’s coil (say , like mermaids).

A Dhyana Sloka (word-picture) of a belligerent serpent (kopakutilam) , in aggressive posture ; with its upper part in human form adorned with multiple hoods , each with two tongues ; its lower part in snake form – reads:

Dhyayeth Nagarupam hinapherudam, narakruthim / sarpakaram adhobhagam , mastake goghimandalam / phanatraye , parijagirda , navagirda, saptadhihi / jihvam , kopakutilam , khadgacharma-dharam tatha //

The texts of the Shilpa-shastra, such as Amsumadbheda-agama, Shilparatna and Maya-mata mention that the image of Nagadeva should have three eyes; four arms; a beautiful countenance of red complexion. The Shilparatna adds that the image should be half human and half serpentine; and must carry a sword and shield in his hand. And, Maya-mata gives a description of seven great Nagas: Vasuki, Takshaka, Karkotaka, Padma, Mahapadma, Sankhapala and kulika; providing descriptions of their colour, attributes and their Ayudhas.

The Visnudharmottara-Purana (Ca.6th century) makes a special mention of the Great Serpent Ananta. Here, Ananta is not regarded merely as the serpent on which Vishnu reclines; but, is revered as the very incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Thus, Ananta is Vishnu himself.

The Text describes the iconography of such divine Ananta, endowed with countless virtues , powers (ananta-shakthi) and countless forms (ananta-rupastu) . The Ananta-puruṣha, here, is said to be matchless (anantāy-āprameyāya); and, resplendent with: four faces; and, twelve arms. In the hands on his right side, Ananta holds Ayudhas such as: Gada (mace), Chakra (disc), Khadga (sword), Vajra (thunderbolt), and Ankusha (goad); and, he also displays Varada-mudra (assurance and protection). And, in the hands on his left side, Ananta holds the Ayudhas such as: Dhanus (bow), Padma (lotus), Khetaka (shield), Shankha (conch), Danda (rod) and Pasha (Noose).

Ananto-ananta-rupastu, hastau dwadasasa–abhiryutah / ananta-shakthi samvito garudastha chatur-mukhah / gadha-krupanu-chakradyau vajra-ankusha-varnvitah/ shanka khetam dhanuh padmam dandam pasau ca vamatah // Vdha.3,350.[6]

The Nagas also find place in the iconography of the other deities. Vishnu is portrayed as reclining on the Sesha; and, at other times the hooded serpents forms a canopy over his head. Vāsuki serpent became the churning rope for churning of the Ocean of Milk. And, Shiva is adorned with King Cobra as garland round his neck; as coiled on his arms as armlets; and on his head. Ganesha uses a serpent as a belt tied around his sumptuous waist; and, as a sacred thread (yajñyopavīta). The Devi as Bhairavi is adorned and served by Shakthi-Naga. The s images of the sages like Sri Dakshinamurthy; the Buddha and Parsvanatha are all depicted as seated under hooded serpents.

Nagarjuna, the champion of the Madhyamika Buddhist philosophy is traditionally portrayed with a halo formed by a multi-headed serpent.

Further, Balarama , the elder brother of Sri Krishna; Lakshmana , the younger brother of Sri Rama; and, the Sage Patanjali who composed the remarkable Yoga Sutra – are all revered as the incarnations of Sesha Naga.

Suggested Reading

You asked; any books to read to get more details?

Yes; there are plenty. There are some comprehensive works on all aspects related to Nagas. You may follow some of these that are available on the net:

Indian Serpent-lore: Or, The Nāgas in Hindu Legend and Art By Jean Philippe Vogel

Tree and serpent Worship, or illustrations of mythology and art in India… By James Fergusson

Encyclopaedia of Oriental Philosophy and Religion: Hinduism – Serpent worship: Pages 774 to 791

http://creative.sulekha.com/the-mythical-naag-devata-the-mythical-snake-god_426933_blog

You may also follow the links mentioned under ‘Sources and references’.

Nagas in history and anthropology

What was said so far was concerned with the Naga worship.

But, the term Naga has multitude of connotations.

The term , depending upon the context, might refer to the oldest tribal communities in the world; to snake worshiping Aryan tribes; to the Naga royal lines of the Kings of Magadha , viz., Shishunaga dynasty (c. 413 – 395 BCE), believed to have been the second ruling dynasty of Magadha Empire of ancient India (after the Haryanka dynasty) ; to the Bharasiva Nava Naga dynasty who ruled from 150-170 AD; to the linage of Naga kings dating back to the Gupta period (from approximately 240 to 590 CE); and to the various Naga communities settled in different parts of India during the early and medieval periods, such as : the Nagas of Vidisha, Padmavathi, Kantipur and Mathura; the Nagas of Erikina (Madhya Pradesh); the Nagas of Bastar; the Nagas of Kawardha; the Nagas of Bhatgaon ; the Nagas of Eastern India ; and so on .

It is said; Ananatnag city in Kashmir was founded by the Naga named Ananta. In Rajtarangini , which chronicles the history of Kashmir kings, there is mention of a brave handsome king of Kashmir, son of a Karkotaka Naga and a Kashmiri Brahmin girl. Their dynasty came to be known as Karkotaka Dynasty. His son became the most powerful king; and, brought peace and prosperity in Kashmir. This Karkotaka was said to be of very kind and helping nature. He helped the Nishada king Nala in regaining his lost kingdom.

It’s also said that Naga dynasty ruled near Ravi in Punjab, from North West of part of Punjab which now is in Pakistan up-to Kazakhstan; Vitasta or Jhelum in Kashmir; River Saraswati’s basin; banks of River Gomati; Kurukshetra, parts of Uttrakhand etc. The Pannagas and the Urgas were said to be the sub-sects of the Naga dynasty. The people who went by the surname Pannaga or Urgas were said to be the either supporters or the descendants of that dynasty.

The Śivadharmaśāstra (a Shaiva text dated prior to seventh century) is in the form of Samvada, a dialogue that takes between the divine sage Sanatkumāra and Śhiva’s foremost Gaṇa Nandi-keśvara. At the request of Sanatkumāra, Nandikeśvara instructs Sanat-kumāra and the other sages dwelling on Mount Meru in the worship of Śhiva.

The Śāntyadhyāya, the longest Chapter of the Śivadharmaśāstra, recounts ,with devotion, the eight serpent lords Naga-rajas (Asta-Nagas) as:

Ananta; Vāsuki; Takṣaka; Karkoṭaka; Padma; Mahāpadma; Śaṅkhapāla; and Kulika

Each Nāgarāja is invoked in elaborate detail, with much attention paid to their individual iconography.

Ananta

With a red body, elongated eyes that are red at the edges, swelling with pride with his great hood, marked by a conch and a lotus—may Ananta, king of the Nāga lords, delighting in the praise of Śiva’s feet, destroy the poison of great evil and quickly bestow peace on me!(166–167)

āraktena śarīreṇa raktāntāyata-locanāḥ| mahā-bhogāḥkṛtāṭopāḥ śaṅkhā-abjāḥkṛta lanchaṇāḥ || Ananto-nāgarājendra Shiva parartane rataḥ| mahā pāpaviṣaṃ hatvā śāntim āśu karotu me||166-167||

Vāsuki

With a very white body, with a crown of very white lotuses, swelling with pride with a handsome hood, adorned with a charming necklace—may Vāsuki, king of the Nāga lords, the great one, intent upon the worship of Rudra, destroy the poison of great evil and quickly bestow peace on me!(168–169)

Suśvetena tu dehena suśvetot palaśekharaḥ|cārubhogakṛtāṭopo hāra cāru vibhūṣaṇaḥ|| vāsukir nāgarājendraḥ rudra pūjāparo mahān| mahā pāpaviṣaṃ hatvā śāntim āśu karotu me|| 168-169||

Takṣaka

With a very yellow body, rich in quivering coils, and with a very luminous splendour, marked by the Swastika — may Takṣaka, the illustrious Nāga lord, accompanied by a crore of Nāgas, bestow peace on me, destroying the poison of all crimes! (170–171)

Atipītena dehena visphurad bhogasampadā|tejasā cātidīptena kṛtasvastika lāñchanaḥ||nāgarāṭ takṣakaḥ śrīmān nāgakoṭyā samanvitaḥ|karotu me mahāśāntiṃ sarva doṣa viṣāpahām|| 170-171||

Karkoṭaka

With a very black color, an expanding hood over his head, provided with three lines on his neck, furnished with terrible fangs as weapons —may the great Nāga Karkoṭaka, possessed of poisonous pride and power, destroy the pain of poison, weapon and fire, and bestow peace on me! (172–173)

Ati-kṛṣṇena varṇena sphaṭā-vikaṭa mastakaḥ| kaṇṭhe rekhā trayopeto ghora daṃṣṭrā -yudhodyataḥ||karkoṭako mahānāgo viṣadarpabalānvitaḥ| viṣa śastrā agnisaṃtāpaṃ hatvā śāntiṃ karotu me|| 172-173||

Padma

With a lotus-colored body, his elongated eyes like handsome lotus petals, illuminated with five spots — may the great Nāga called Padma, delighting in the praise of Hara’s feet, bestow peace on me, destroying the poison of great evil! (174–175)

Padma-varṇena dehena cāru padmāyate-kṣaṇaḥ| pañca bindu kṛtābhāso grīvāyāṃ śubha lakṣaṇaḥ||khyāta padmo mahānāgo hara pādārcane rataḥ|karotu me mahā śāntiṃ mahā pāpaviṣakṣayam||174-175||

Mahāpadma

And with a body like a white lotus, of immeasurable splendour, always adorned on his head with the marks of a brilliant conch, trident and lotus—may the great Nāga Mahāpadma, constantly bowing to Paśupati, destroy the terrible poison and quickly bestow peace on me! (176–177)

Puṇḍarīka-nibhenāpi dehenā amitatejasā|śaṅkhaśūlā abjarucirair bhūṣito mūrdhni sarvadā||mahāpadmo mahānāgo nityaṃ paśupater nataḥ| vinikṛtya viṣaṃ ghoraṃ śāntim āśu karotu me|| 176-177||

Śaṅkhapāla

With a dark body-mass, his eyes like beautiful lotuses, intoxicated with poisonous pride and power, with a single line on his neck—may Śaṅkhapāla, bright with luster, worshiping the lotus-feet of Śiva, destroy great evil, the great poison, and bestow peace on me! (178–179)

śyāmena deha-bhāreṇa śrīmat-kamala-locanaḥ| viṣa darpa balonmatto grīvāyām eka rekhayā|| śaṅkhapālaḥ śriyā dīptaḥ śiva pādābja pūjakaḥ|mahāviṣaṃ mahāpāpaṃ hatvā śāntiṃ karotu me|| 178-179|

Kulika

With a very terrifying body, his head furnished with the sickle of themoon, swelling with pride with a shining hood, marked with an auspicious mark—may Kulika, the best of the Nāga kings, always intent upon Hara, remove the terrible poison and bestow peace on me! (180–181)

Ati ghoreṇa dehena candrārdhakṛta mastakaḥ|dīpta bhoga kṛtāṭopaḥ śubha lakṣaṇa lakṣitaḥ|| kuliko nāgarājendro nityaṃ hara parāyaṇaḥ|apahṛtya viṣaṃ ghoraṃ karotu mama śāntikam|| 180-181||

Prayers are also submitted to other Nagas in the sky; the Nāgas abiding in heaven, on earth, on mountains, in caves and in forts; as also the Nāgas present in the nether region .

And to Nāginīs; Nāgakanyās; and, Nāgakumārās -the Nāgas’ wives; daughters; and the Nāgas’ sons— may all of them, assembled here, dedicated to the praise of Rudra’s feet, bestow peace on me!

nāginyo nāgakanyāś ca tathā nāgakumārāḥ|śiva bhaktāḥ sumanasaḥ śāntiṃ kurvantu me sadā|| 184||

[I acknowledge with deep gratitude, the source: Universal Śaivism: The Appeasement of All Gods and Powers in the Śāntyadhyāya by Peter Bisschop.

The translations of the verses are by the author.]

There is also a tradition winch recounts Nava–Nagas. The Nava-Naga Stotra mentions the Nine Nagas as:

(1) Ananta; (2) Vasuki; ( 3) Shesha; (4) Padmanabha; (5) Kambala;(6) Shankhapala; (7) Dhritarashtra; (8) Takshaka; and, (9) Kaliyan.

Prayers are submitted to these Nagas seeking protection from the dangers of poison; and, to grant success at all times in one’s life (Vishabhayam Naasti ; Sarvatra Vijayi Bhaveth)

Anantam Vasukim Shesham / Padmanabham cha Kambalam / Shankhapalam Dhartarashtram / Takshakam Kaliyam Tatha

Etani Nava Namani Naganam cha Mahatmanah / Sayankale Patten-nityam Pratahkale Visheshatah / Tasya Vishabhayam Nasti ; Sarvatra Vijayi Bhaveth

अनन्तं वासुकिं शेषं पद्मनाभं च कम्बलं / शन्खपालं ध्रूतराष्ट्रं च तक्षकं कालियं तथा / एतानि नव नामानि नागानाम च महात्मनं / सायमकाले पठेन्नीत्यं प्रातक्काले विशेषतः / तस्य विषभयं नास्ति सर्वत्र विजयी भवेत //

[ According to the Nava Naga tradition, the Naga King Ananta was the founder of the Naga dynasty; and, was a very saintly person. He preferred to reside at Gandhmadana Parvata (in the Himalayan region). And, at times, he stayed deep inside the ‘Great lake’ (perhaps the Manasa lake).

It is said; the Naga King Vasuki saved his community from the assault of the Suparna tribes; and, rehabilitated them in a city called Bhogawati, which later became his capital. It is said; Vasuki’s nephew, the wise and bright looking Astika saved the beleaguered Nagas by causing to stop the massacre or genocide of Nagas undertaken the avenging Kuru King Parikshit.

Following Vasuki, the good-looking, powerful Naga King Airavata, further developed the Capital Bhogawati into a splendid affluent city. He is also said to have founded a place, later named as Nag-Tirtha, which still exists in Uttarakhand region.

The handsome and rich Naga King Takshaka was the son of Airavata. He, in turn, founded the famous city Takshashila (Taxila – now in Pakistan) . The Takshashila later developed in a famous center of learning, to where the students from all parts of India came seeking higher education.

The famous King Pururava hailing from a Deva-Kshatriya clan had a son called Ayu. And, one of Ayu’s son was Nahusha. According to the myth Nahusha was a Naga King. His son was the famous king Yayati of the lunar dynasty (Chandra-vamsha), who tried to reconcile the differences between the followers of the rival sages Brighu (Asuras) and Angirasa (Devas).

The descendants of Yayathi – Puru, Kuru, Yadava and Bharatas – ruled as the celebrated kings of ancient India. It is said; the clans of Sawhanis, Seuna Yadavas, Bhattis, Chandelas and the Jats of Bharatpur and Mathura have descended from the Chandra-vamsha

The Naga King Aryaka was said to the great grandfather of Kunti, the mother of the mighty Pandavas. Aryaka saved the young Bhima’s life when he was food-poisoned by his embittered cousin Duryodhana.

The cultured and wise Naga King Padmanabha is said to have extended his kingdom; and, established a new capital adjacent to the forest Naimisharayna, near the river Gomati (in the present day Uttar Pradesh) .]

Apart from these, the literary traditions too mention of the royal dynasties of ancient India, which claimed a Naga or a Nagini as their progenitor. Such instances include those of King Udayana who married a Naga princess, giving rise to Sakya dynasty. The dynasty of Kashmir, which included the famous King Lalitaditya (Ca.8th century), is said to have descended from Naga Karkotaka. The neighboring Kings of Bhadarwah claimed descent from the serpent king Vasuki. And, the Rajas of Chota Nagpur derive their origin from Naga Pundarika. And, in the South, the Shalivahana of Pratistana as also the Pallavas claimed descent from Ananta Naga. And, so on…

The tradition recorded by Hiuen Tsang suggests that the city of Nalanda got its name from a Naga named Nalanda, which was believed to be the guardian deity of the city.

Countless ancient Naga images have been discovered at the various regions of India, as in areas around Mathura; Rajagriha (Modern Rajgir in Patna, Bihar), the ancient capital of Magadha, and its neighborhood; and many other places.

The history of the Naga cult is one of the most interesting chapters in Indian history. And, that, by itself, is a vast subject; and, has been dealt with in great detail by several historians, anthropologists and scholars of social studies.

In case you are interested in such studies, I suggest, you may start with Chapter Seven: Naga, the evolution of tribal culture (from pages 177 to 234) by Dr. Shiv Kumar Tiwari – (Published by Sarup &Sons; New Delhi; 2002-3). It comprehensively deals with numerous legends, traditions, histories and cultures related to the Nagas. The full view of the book is available on the net. Please also check the bibliography given therein for further study.

You may, may also follow the sources and references listed under; at the end of this post.

As regards the Naga Identities: Changing Local Cultures in the Northeast of India, please read the scholarly study made by Alban von Stockhausen, Michael Oppitz, Thomas Kaiser and Marion Wettstein.

Please also see the very well researched paper The Nagas; an introduction ; covering their Social Identity, Cultural Identity, Nagaland etc. by Alban von Stockhausen and Marion Wettstein.

Sources and references

Indian Temple traditions by Dr.SK Ramachandra Rao

Indian Serpent-lore: Or, The Nāgas in Hindu Legend and Art By Jean Philippe Vogel

Tree and serpent Worship, or illustrations of mythology and art in India… By James Fergusson

Encyclopaedia of Oriental Philosophy and Religion: Hinduism – Serpent worship: Pages 774 to 791

Naga, the evolution of tribal culture by Dr. Shiv Kumar Tiwari

The Nāgas and the Naga cult in ancient Indian history by Karunakana Gupta (Proceedings of the Indian History Congress – Vol. 3 (1939), pp. 214-229) – http://www.jstor.org/stable/44252377

A Study of Naga Beings as a Global Phenomenon and their relation with Kailash / Manosarovar region by Susan M. Griffith-Jones

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44140714?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents byU N Mukherjee

http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/35963/3/ch%203%20naga%20cult%20in%20india.pdf

http://farbound.net/behind-the-myth-of-the-serpent-people/

https://tamilandvedas.com/tag/naga-worship/

https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/84162

Serpents in Angkor by Adalbert J. Gail

All images are from Internet.