1.1. Crazy wisdom is a way of teaching; and it is prevalent in almost all traditions. It has been there for a very long-time. Crazy wisdom says: we all are, in truth, interconnected. The separations in the physical world such as human bodies, houses, communities are mere appearances. Crazy Wisdom seeks to unearth and heal the false beliefs that people have about themselves and of the world around them. It is a means for expressing and maintaining the difference between the conventional point of view and the transcendental point of view.

1.2. The teaching might have gained that name – crazy – because, its teachers were eccentrics who used their eccentricity to bring forth an alternate vision, the one that was different from the pedestrian and dogma-riddled view of existence. They were the masters of inversion, proficient breakers of taboos and lovers of surprises. They relished the delight in contradictions and ambiguity. Sometimes they overdid and went overboard; and were mistaken for tricksters and clowns.

1.3. Crazy wisdom or holy-madness, as it came to be called, does indeed seem crazy to rational mind and commonsense. That is because it is designed, deliberately, to confront, to shock and to confuse an otherwise rational mind. The crazy teacher’s behavior and his teachings turn the ordinary view of life upside down; and, project life in a different perspective. His approach is what one might call “no-holds-bar”. The crazy teacher is willing to employ a wide range of tactics and applications including , but not limited to , provocation, insult, physical and mental abuse, humour, and credulity; and in extreme cases, it might stray in to use of alcohol, drugs and sex. All those unconventional and socially unacceptable ways of behaviour were pressed into service in order to drag the student out of the cocoon, strip him naked and bring him face to face with reality.

1.4. Predictably, such behavioural patterns create scare and conflict in the minds of even the committed followers of the path. It also brings into question, the issues of trust; and abuse of position and power. But a serous seeker will have to face those challenges and resolve the contradictions, all by himself.

1.5. The crazy wisdom or foolish wisdom is thus a two-edged sword, to be handled with extreme caution. The dividing line between wisdom and foolishness is very thin; and it is not possible to say with certainty when a fool is just a fool, or a fool graced by wisdom, or a wise person touched by foolishness.

1.6. In all such traditions, it is said, a genuine crazy –wisdom- teacher will act only in response to the needs of his student, regardless of his own discomfort and personal preferences. His main concern is the awakening of his student .But, it is the responsibility of the student to understand and learn; and the teacher is not obliged to make it easy for the student.

1.7. It is explained, the teacher, to put it crudely, is like a dispensing machine. The student will have to come up with right questions to get the benefit of the teacher. It is the questions the student frames – internally or explicitly- and the demands he makes in seeking the answers that truly matter. He can challenge himself to formulate a question that accurately captures the real need; and follow it with intensity. After a period of time, as he begins to endure the heat (tapa), generated by the genuine unanswered questions, the answers start appearing unexpectedly in the most unlikely places or in the most obvious places right under his nose.

That is the basis of the learning process under an Avadhuta or a Siddha or a Zen teacher or the saintly – madman (lama myonpa) of Tibetan Buddhism.

[ By the way, Aryadeva (14th century?), a Buddhist scholar, in his Chatuhsataka (four hundred verses) narrates a story to illustrate (a) madness is a relative concept; and (b) just because one is in a minority he cannot be dismissed as being wrong.

According to his story, a wandering astrologer warned a king that in a week’s time, very heavy rain would pour down on his country; and whoever drinks that rainwater would go insane. The king took the astrologer’s warning quite seriously and ordered to get his well of drinking water tightly covered. His subjects, however, either lacking means or laughing at the astrologer, took no action to secure their sources of drinking water. It did rain a week hence, as predicted; and the whole of the kingdom’s populace drank the rain water which found its way into their well and tanks. They all, promptly, went mad. The king , who had protected his well, was the only sane person in the whole of his kingdom.

But, the king’s subjects gathered together and laughed and jeered at the king calling him insane. After such repeated heckling, the king – the only sane person in the whole of the kingdom – could no longer endure the irritating jibes. In order to put an end to his agony, the king, at last, decides to drink the rain water. And, he promptly goes mad just, as his subjects. Now, all are alike ; and all are happy in their madness.

Therefore, if one is the sole, single sane person, then he does not get to call the rest as insane. But, at the same time, he would not be wrong if he calls the rest as insane. Then, again, who will listen to him or pay heed to his words …!!

The story also illustrates how ‘madness’ is a relative concept, depending upon each one’s perspective. In the broader view, what defines madness is the social, cultural and other ways of understanding human behavior at different times; and, in different regions. Madness is thus a highly context-sensitive issue.]

****

2.1. Avadhuta, the one who has cast off all concerns and obligations, like the Shiva himself, is the typical teacher of wisdom. He does that in a highly unconventional manner. He has no use for social etiquette; he has risen above worldly concerns. He is not bound by sanyasi dharma either. He roams the earth freely like a child, like an intoxicated or like one possessed. He is the embodiment of detachment and spiritual wisdom..

Avadhuta Gita describes him as :

Having renounced all, he moves about naked./ He perceives the Absolute, the All, within himself.

ātmaiva kevalaṃ sarvaṃ bhedābhedo na vidyate । asti nāsti kathaṃ brūyāṃ vismayaḥ pratibhāti me ॥ 4॥

The Avadhuta never knows any mantra in Vedic meter or any Tantra.

Ashtavakra Gita describes him in a similar manner:

17.15

The sage sees no difference/ Between happiness and misery,/ Man and woman, / Adversity and success./ Everything is seen to be the same.

sukhe duḥkhe nare nāryāṃ sampatsu ca vipatsu ca । viśeṣo naiva dhīrasya sarvatra samadarśinaḥ ॥ 17-15॥

17.16

In the sage there is neither/ Violence nor mercy,/ Arrogance nor humility,/ Anxiety nor wonder./ His worldly life is exhausted./ He has transcended his role as a person.

na hiṃsā naiva kāruṇyaṃ nauddhatyaṃ na ca dīnatā । nāścaryaṃ naiva ca kṣobhaḥ kṣīṇasaṃsaraṇe nare ॥ 17-16॥

17.18

The sage is not conflicted/ By states of stillness and thought./ His mind is empty./ His home is the Absolute.

samādhāna samādhāna hitāhita vikalpanāḥ । śūnyacitto na jānāti kaivalyamiva saṃsthitaḥ ॥ 17-18॥

18.9

Knowing for certain that all is Self,/ The sage has no trace of thoughts/ Such as “I am this” or “I am not that.”

ayaṃ so’hamayaṃ nāhaṃ iti kṣīṇā vikalpanā । sarvamātmeti niścitya tūṣṇīmbhūtasya yoginaḥ ॥ 18-9॥

18.10

The yogi who finds stillness/ is neither distracted nor focused./ He knows neither pleasure nor pain./ Ignorance dispelled,/ He is free of knowing.

na vikṣepo na caikāgryaṃ nātibodho na mūḍhatā । na sukhaṃ na ca vā duḥkhaṃ upaśāntasya yoginaḥ ॥ 18-10॥

**

2.2. Among the classical texts that describe the nature of the Avadhuta, the prominent ones are the Avadhuta Gita , the culminating text of the Dattatreya tradition; the Ashtavakra Gita , a text of the highest order, addressed to advanced learners and dealing with the means of realizing the Self (atmanu-bhuti) and the mystic experience in the embodied state. The third and a comparatively a recent text is the Atma-vidya-vilasa of Sri Sadashiva Brahmendra , an Avadhuta who lived during the eighteenth century.

2.3. The other major sect is the Siddha tradition of South India. The Siddha is one who has attained flawless identity with reality.

Jainism too recognizes Siddha as an enlightened teacher. In the Tibetan Buddhism, Siddha is a yogi who has attained magical powers and the ability to work miracles.

2.4. In so far as the folk tradition is concerned, there are a number of regional groups and subgroups. The better known of them are the Bauls of Bengal; the word meaning mad or confused. They are a religious sect of eccentrics. The Baul synthesis is characterized by four elements: there is no written text and therefore all teachings are through song and dance; God is to be found in and through the body and therefore the emphasis on kaya (body) sadhana, the use of sexual or breathe energy; and, absolute obedience and reverence to Guru.

3.1. Avadhuta Gita the ‘Song of the Ever Free’ does not indulge in debates to prove the non-dual nor does it ask you to control your senses; it sees no distinction between sense perception and spiritual realization. It makes some amazing statements:

The mind indeed is of the form of space. The mind indeed is Omni faced. The mind is the past. The mind is present and future and all phenomena. But in absolute reality, there is no mind.

All your senses are like clouds; all they show is an endless mirage. The Radiant One is neither bound nor free.I am the Bliss, I am the Truth, I am the Boundless Sky

There is neither knowledge nor ignorance nor knowledge combined with ignorance. He who has always such knowledge is himself Knowledge. It is never otherwise.

How shall I salute the formless being, indivisible, auspicious and immutable, who fills all this with its self and also fills the self with its self?

Know it firmly, freely, independently. And maintain it at all times, all conditions. That is all. Be Avadhuta Dattatreya yourself; because, you are yourself that.

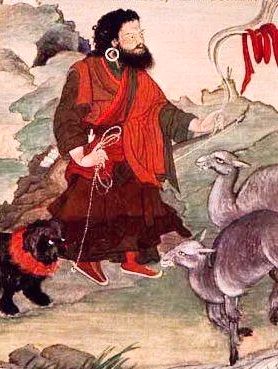

Dattatreya by Shilpi Arun Yogiraj

3.2. In the Ashtavakra Gita, sage Ashtavakra maintains that all prayers, mantras, rituals, meditation, actions, devotion, breathing practices, etc are secondary. These distract the aspirant from self-knowledge. Knowledge/awareness is all that is required. Ignorance does not exist in itself; it is just the absence of knowledge or the lack of awareness. The light of knowledge or consciousness will dispel ignorance revealing the Self. The Self is merely forgotten, not lost.

This is not a belief system or a school of thought. This is simply ‘What Is’ and the recognition of ‘What is’.

Attachment and aversion/ Are attributes of the mind./ You are not the mind. You are Consciousness itself–Changeless, undivided, free./ Go in happiness

rāgadveṣau manodharmau na manaste kadācana । nirvikalpo’si bodhātmā nirvikāraḥ sukhaṃ cara ॥ 15-5॥

You can recite and discuss scripture / All you want,/ But until you drop everything / You will never know Truth.

ācakṣva śṛṇu vā tāta nānā śāstrā aṇyanekaśaḥ । tathāpi na tava svāsthyaṃ sarva vismaraṇād ṛte ॥ 16-1॥

Ashtavakra then attacks the futility of effort and knowing.

Being pure consciousness, / Do not disturb your mind with thoughts of for and against./ Be at peace and remain happily’ In yourself, the essence of joy. 15.19

mā saṅkalpavikalpābhyāṃ cittaṃ kṣobhaya cinmaya । upaśāmya sukhaṃ tiṣṭha svātmanyānandavigrahe ॥ 15-19॥

Give up meditation completely/ But don’t let the mind hold on to anything./ You are free by nature,/ So what will you achieve by forcing the mind? 15.20

tyajaiva dhyānaṃ sarvatra mā kiṃcid hṛdi dhāraya । ātmā tvaṃ mukta evāsi kiṃ vimṛśya kariṣyasi ॥ 15-20॥

kva māyā kva ca saṃsāraḥ kva prītirviratiḥ kva vā । kva jīvaḥ kva ca tadbrahma sarvadā vimalasya me ॥ 20-11॥

kva pravṛttirnirvṛttirvā kva muktiḥ kva ca bandhanam । kūṭasthanirvibhāgasya svasthasya mama sarvadā ॥ 20-12॥

**

3.3.  Atma_vidya_vilasa is written in simple, lucid Sanskrit. Its subject is renunciation. It also describes the ways of the Avadhuta, as one who is beyond the pale of social norms , beyond Dharma , beyond good and evil; as one who has discarded scriptures, shastras , rituals or even the disciplines prescribed for sannyasins;one who has gone beyond the bodily awareness , one who realized the Self and one immersed in the bliss of self-realization. He is absolutely free and liberated in every sense – one who “passed away from” or “shaken off” all worldly attachments and cares, and realized his identity with God. The text describes the characteristics of an Avadhuta, his state of mind, his attitude and behavior. The text undoubtedly is a product of Sadashiva Brahmendra’s own experience. It is a highly revered book among the Yogis and Sadhakas.

Atma_vidya_vilasa is written in simple, lucid Sanskrit. Its subject is renunciation. It also describes the ways of the Avadhuta, as one who is beyond the pale of social norms , beyond Dharma , beyond good and evil; as one who has discarded scriptures, shastras , rituals or even the disciplines prescribed for sannyasins;one who has gone beyond the bodily awareness , one who realized the Self and one immersed in the bliss of self-realization. He is absolutely free and liberated in every sense – one who “passed away from” or “shaken off” all worldly attachments and cares, and realized his identity with God. The text describes the characteristics of an Avadhuta, his state of mind, his attitude and behavior. The text undoubtedly is a product of Sadashiva Brahmendra’s own experience. It is a highly revered book among the Yogis and Sadhakas.

One of such Sadhakas who really emulated Sadashiva Brahmendra and evolved into an Avadhuta was the 34th Acharya , the Jagad-guru of Sri Sringeri Mutt, Sri Chandrasekhar Bharathi Swamiji. He studied Atma_vidya_vilasa intensely, imbibed its principles and truly lived according to that in word and deed. Unmindful of the external world, he roamed wildly in the hills of Sringeri like a child, an intoxicated, and an insane; and as one possessed, singing aloud the verses from Atma_vidya_vilasa:

Discard the bondages of karma. Wander in the hills immersed in the bliss of the Self -unmindful of the world like a deaf and a blind (AVV-15)

avadhūtakarmajālo jaḍabadhirāndhopamaḥ ko’pi । ātmārāmo yatir āḍaṭavīkoṇeśvaṭannāste ॥ 15॥

Rooted in the Brahman absorbed in the bliss within, he for a while meditates, for a while sings and dances in ecstasy. (AVV-21)

tiṣṭhanparatra dhāmni svīyasukhāsvādaparavaśaḥ kaścit । kvāpi dhyāyati kuhacidgāyati kutrāpi nṛtyati svaram ॥ 21॥

He sees nothing, hears nothing, and says nothing. He is immersed in Brahman and in that intoxication is motionless.(AVV-44)

paśyati kimapi na rūpaṃ na vadati na śṛṇoti kiñcidapi vacanam । tiṣṭhati nirupamabhūmani niṣṭhāmavalambya kāṣṭhavadyogī ॥ 44॥

4. 1.![]() The Lankavatara Sutra of the Mahayana Buddhism is another text of the “crazy wisdom” tradition. It was the text that Bodhidharma followed all his life and bequeathed it to his disciple and successor Hui K’o . Its basic thrust is on “inner enlightenment that does away with all duality.” One of the recurrent themes in the Lankavatara Sutra is, not to rely on words to express reality. It holds the view that objects do not owe their existence to words that indicate them. The words themselves are artificial creations. Ideas, it says, can as well be expressed by looking steadily, by gestures, by a frown, by the movement of the eyes, by laughing, by yawning, or by the clearing of the throat, or by recollection, or by trembling.

The Lankavatara Sutra of the Mahayana Buddhism is another text of the “crazy wisdom” tradition. It was the text that Bodhidharma followed all his life and bequeathed it to his disciple and successor Hui K’o . Its basic thrust is on “inner enlightenment that does away with all duality.” One of the recurrent themes in the Lankavatara Sutra is, not to rely on words to express reality. It holds the view that objects do not owe their existence to words that indicate them. The words themselves are artificial creations. Ideas, it says, can as well be expressed by looking steadily, by gestures, by a frown, by the movement of the eyes, by laughing, by yawning, or by the clearing of the throat, or by recollection, or by trembling.

Bodhidharma instructed his disciples to: “Leave behind the false, return to the true; make no discrimination between self and others. In contemplation, one’s mind should be stable, alert and clear like the wall; illuminating with compassion. “

4.2. In Zen too, the “holy madness” is widely used by the roshi (teacher). The adepts of Zen make use of shock techniques such as sudden shouting, abuses, physical violence, handclapping, paradoxical verbal responses, koans and riddles in order to induce satori or enlightenment.

4.3. Tibetan Buddhism also has its share of eccentric Lamas who use unconventional methods to initiate their disciples into enlightenment. Crazy wisdom in Tibetan is yeshe cholwa, where craziness and wisdom walk hand in hand. It is craziness gone wise rather than wisdom gone crazy. Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) and Karma Pakshi the second Karmapa are the celebrated crazy-wisdom – teachers in Tibetan Buddhism. They both were regarded as being able to overpower the phenomenal world. They demonstrated that what we call crazy is only crazy from the viewpoint of ego, custom and habit. Crazy wisdom is natural and effortless; not driven by the hope and fear.

There is also another set of “mad lamas (smyon‑pa) who reject monastic tradition, ecclesiastical hierarchy, societal conventions, and book learning.

4.4. Crazy wisdom is also practiced in Sufism, where it is known as “the path of blame.” Some Sufi mystics –majzubs – are known for their strange behaviour as well as for their heretical doctrine of their identification with the divine. The Sufi practitioners of “crazy wisdom” pursue freedom and humility without concern for worldly consequences.

5.1. The crazy teachers were found not just in the East. Socrates was an archetypal wise fool who claimed that his wisdom was derived from his awareness of his ignorance. His distinctive teaching method consisted in exposing the foolishness of the wise.

5.2. Even in the Christian tradition, the absurd notion that the fool may be wise and that the wise may be foolish—has long been in existence. It is often expressed as the “fool in Christ” or the “fool for Christ’s sake”. Here, foolish wisdom, the “holy folly”, is akin to “holy simplicity” or “learned ignorance”, which is an alternate way to rekindle the love of wisdom in the hearts of men and women. It is singular and sudden; and, is in contrast with the laborious common wisdom of the learned.

5.3. Europe in the sixth century seemed to be a great period for Crazy Adepts. For instance, there was St. Simeon who liked to pretend insanity for effect. Once he found a dead dog on a dung heap. He tied the animal to his belt and dragged the corpse through town. People of the town were outraged. But, he was trying to demonstrate the uselessness of excess emotional “dead weight” that people drag through their lives.

The very next day, St. Simeon entered a church and just as the liturgy began, he threw nuts at the congregation. St Simeon revealed on his deathbed that his life’s mission was to denounce hypocrisy and hubris.

5.4. Another example of the sixth-century spiritual silliness was Mark the Mad, a desert monk who was thought insane when he came into town to atone for his sins. Only Abba Daniel saw the method in the monk’s madness, and declared the monk the only reasonable man in the city.

5.5. Saint Francis of Assisi was another example of foolish wisdom. He regarded himself as a fool deserving nothing but contempt and dishonour. He is celebrated for his tender love for God and for God’s creatures, big and small.

6.1. The paradoxical idea that the fool may be wise is perhaps as old as humanity itself. It is a common experience that the untutored and innocent, including children, somehow seem to grasp profound truths, while the lettered and the learned just walk past it. Jesus alluded to it when he thanked and praised God for having hidden from the learned and the clever what he revealed to the merest children (Mt 11:25).

6.2. Without love, foolishness is just foolishness; and wisdom a mere collection of inflated bits of information. Ultimately, the foolish wisdom is a gift, a revelation received in humility of mind and simplicity of heart; an un-bounded, luminous, loving energy. It attains the power to convince and transform, more effectively than the sword and rhetoric.

That is possible only when it is graced by tender love for the fellow beings and for the fellow seekers.

Sources and References:

http://www.spiritual-endeavors.org/basic/crazy.htm

Crazy Spirituality

http://eapi.admu.edu.ph/eapr002/wisdom.htm

Wisdom of the Holy Fools

http://www.onelittleangel.com/wisdom/quotes/book.asp?mc=319

Avadhuta

http://www.shambhala.org/teachings/view.php?id=131

Crazy Wisdom

Zen Stories by Sylvan Incao