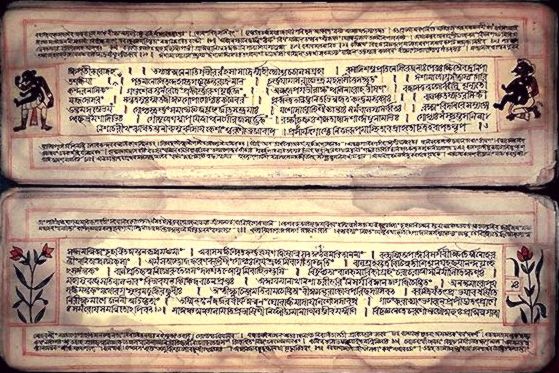

ASTADHYAYI – STRUCTURE

As its very name indicates, the Astadhyayi comprises Eight (Asta) Chapters (Adhyaya); and each Adhyaya is divided into four quarters (Paada-s). Thus, there are in all thirty- two Paadas. Each Paada consists of a series of grammatical statements, called Sutras, related to each other. The number of Sutras in each Paada varies according to the topics, functions and organizational constraints.

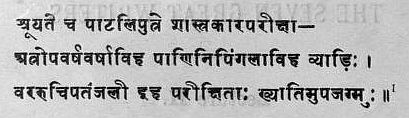

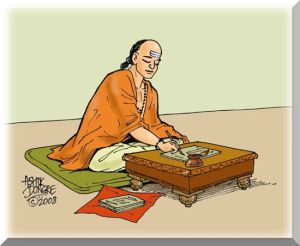

The Sutra-patha of the Astadhyayi has come down to us through oral tradition. It is remarkable that the text, except for few variations and interpolations, has remained virtually intact. That is mainly because of the enormous amount of work that has gone into its study. And, also because of the three major texts, namely the Vyākaraṇa-mahābhāṣya of Patañjali, the Kāśikā-vṛtti of Vāmana-Jayāditya and the Vaiyākaraṇa-siddhānta-kaumudī of Bhaṭṭoji Dīkṣita, which have thoroughly vetted Panini’s text. And, therefore, the text of the Aṣṭādhāyī which is available today can be taken as fairly established.

The total number of Sutras in the Astadhyayi is said to be about 4,000. But, there is a slight variation across the different editions.

As per the text edited by the noted scholar Srisa Chandra Vasu (1891), based on the statement made by Jinendrabuddhi , the total number of Sutras in Astadhyayi is 3,996

(trini sutra sahasrani tatha nava-satani va sannavatim ca sutranam Paninh krtavan svayam).

However, as per Kaisika of Jayaditya and Vamana (7th century), which is said to have addressed the full text of the Astadhyayi, the number of Sutras is 3,981.

It is explained that the difference of fifteen Sutras between the two Editions, is because of accepting the initial statement of the Astadhyayi (Atha Sabdanusasanam); and, the fourteen Sutras of Shiva-sutra (Maheshvara-sutra) as being the part of the text per se.

As per Bhattoji Diksita (Siddantha kaumudi- 17th century CE) the total number of Astadhyayi-Sutras is 3,976.

The difference of five from the Kaisika is said to be due to the omission of four Sutras from the fourth quarter (Paada) of the fourth Chapter; and, one Sutra from the fourth quarter of the Sixth chapter.

Therefore, the exact number of Sutras varies between 3,976 and 3,996.

The number of Sutras in each Paada of each of the eight Adhyayas of Astadhyayi, as per Kaisika is as under

**

Auxiliary texts

As mentioned earlier, the Astadhyayi consists of about 4000 sutras arranged in eight Chapters (Adhyaya) each made of four quarters (Paada).

In addition there are three associated texts, which, at times, are treated as separate from the main text. These are: Shiva-sutra (Maheshvara-sutra); Dhatu-patha; Gana-patha;

Shiva-sutra

The Shiva-sutras are a set of fourteen Sutras; brief, but highly well organized list of phonemes (Varna-s). It precedes the Astadhyayi, proper. It enumerates fourteen sound segments (Varna-samamnaya) of the Sanskrit language, in the order that is most conducive for forming the abbreviated terms (Pratyahara) used in the Grammar.

Panini’s grammar opens with an arrangement of the alphabhets not in their natural order known to us. The simple vowels are given first; then the combination of two vowels in a single syllable; then the semi-vowels; then the nasals ; then the consonants proper- where the Alpa-prana and the Maha-prana are kept distinct. And then the Samvara, Nada and Ghosha are given , followed by the Vivara,shavsha and Ghosha (these being the first two letters of each varga and Sha, Sa, Ha.

Here, in the table given above the Sutras 1 to 4 are vowels; and 5 to 14 are consonants. The order of elements listed in the Śhiva-sutra is as follows:

(1) Vowels (1-4):

(a) Simple (1-2); (b) complex (3-4)

*

(2) Consonants (5-14)

(a) Semivowels (5-6); (b) Nasals (7)

(c) stops (8-12)-(i) voiced aspirates (8-9); (ii) voiced non-aspirates (Śs 10); (iii) voiceless aspirates (Śs 11); (iv) voiceless non-aspirates (12)

(d) Spirants (13-14)

*

The Shiva-sutra is termed by the western scholars as phonology (notational system for phonemes specified in 14 lines). This notational system introduces different clusters of phonemes that serve special roles in the structure of Sanskrit language; and, are referred to throughout the text. It is said; each cluster, called a Pratyāhara, ends with a dummy sound called an Anubandha, which acts as a symbolic referent for the list. Within the main text, these clusters, referred through the Anubandhas, are related to various grammatical functions.

[Prof. Gerald Penn of Toronto University , in his comments , observes :

The Shiva Sutras seemed to have been designed not so much as a phonological inventory (it appears twice, for example); but, as a tabulation of variable names that are then used to refer to sets of Aksharas within the formal rule system, so as to minimize the overall size of the table.]

Please click here for Sivasutra (with Vartika)

**

Other Rules

As it has often been said, Astadhyayi is not Grammar per se; but, is a system of rules which generates all correct forms of Sanskrit. The the body of rules is accompanied by lists of linguistic basic elements. These are: the Dhätupätha and the Ganapatha.

Dhātupāṭha

The texts which enumerate roots of the Sanskrit language are generally referred to as Dhātupāṭha. It is not clearly known who its original authors were. Scholars generally agree that Pāṇini used the Dhatupatha in formulating his Aṣṭādhyāyī. The Dhatupatha is the list of 1,943 verb roots (Dhātu) arranged into ten classes, according to stem-formations, which determine conjugation (Samdhi). The roots are grouped by the form of their stem in the present tense; and, are provided with a short meaning.

Although the Dhātupāṭha is, in principle, a list of the roots to which suffixes can be added, it provides much more information on account of the appended anubandhas, “indicatory letters,” accompanying meaning entries; and , the ten verbal classes into which the roots are divided. They are an integral part in the application of Pāṇini’s rules,

[Please click here for : Paniniya-Dhatu Patha , without pronunciation marks; and for the version with pronunciation marks click here.

Please click here for Paniniya-Shiksha ; and here for the meaning ]

Ganapatha

The Ganapatha lists nominal stems grouped by common properties, each of which comes under a particular rule of Sutra-patha. The Ganapatha listing is said to be of two kinds: the closed-list; and the open-ended list. The authorship of the Ganapatha is again debatable. Pāṇini makes frequent references in his Aṣṭādhyāyi to the lists of Ganapatha.

Other auxiliary rules

In addition, three other auxiliary texts are associated with the Astadhyayi. The authorship of these texts is much debated. Panini does, however, refer to the rules of these texts in his work.

Uṇādi-sūtras

The Uṇādi-sūtras are affixes used to derive nominal stems. Pāṇini mentions the Uṇādi in two of his rules: uṇādayo bahulam (3.3.1); and, tābhyām anyatroṇādayaḥ (3.4.75). The first rule introduces the Uṇādi affixes after verbal roots variously (bahulam).And, the second rule states that the Uṇādi affixes can also be introduced to denote a Kāraka (case), other than Sampradāna (dative) and Apādāna (ablative).

Phiṭsūtras

The Phiṭsūtras is a small treatise that deals with accentuation of linguistic forms not developed through any process of derivation. This treatise gets its name from its first Sūtra, phiṣaḥ which assigns a final high pitch accent.

Liṅgānuśāsana

The Liṅgānuśāsana is a treatise, which deals with assignment of gender, based on structure and meaning of nominals. The text of this treatise consists of nearly 200 Sutras enumerating items under the headings of feminine (Strīliṅga); masculine (Puṃliṅga); neuter (Napuṃsaka); feminine-masculine (strīpuṃsaka); and variable (aviśiṣṭaliṅga). Finally, there is also a set of nominals which can be used in all three genders.

[ Please click here for the Linganusasanam on genders]

The structure of Astadhyayi, its organization and functions

The noted scholar Sumitra M. Katre observes: The Astadhyayi, for all its brevity, follows a well-defined format. Panini’s rules though enumerated in a definite order (purva-parya); are classified into segments and Chapters, according to the topics and their functions (Adhikarana).

The following is the broad indicators of the topics discussed in the Astadhyayi :

Book One:

(i) Major rules for definitions and interpretations – Samjnas (technical terms); Paribashas (grammatical conventions);

(ii) Rules dealing with extensions

(iii) Rules dealing with Atmaneyapada-parasmaipada

(iv) Rules dealing with Karakas

Book Two

(i) Rules dealing with compounds (Upapada)

(ii) Rules dealing with nominal functions

(iii) Rules dealing with number and gender of compounds

(iv) Rules dealing with replacements and relative to roots (Anubandhas)

(v) Rules dealing with deletion by LUK , with reference to compostion derivation, etc

Book Three

(i) Rules dealing with the derivation of roots ending in affixes saN etc.,

(ii) Rules dealing with derivation of items ending in a Kri

(iii) Rules dealing with derivation of items ending in a tiN

Books Four and Five

(i) Rules dealing with derivation of a pada Samasanta-pratyayas ending in a sUP

(ii) Rules dealing with feminine affixes – Strlpratyayas – Krt

(iii) Rules dealing with derivation of nominal stems ending in an affix named Taddhita

(iv) Rules regarding loss, addition, alteration, and constancy of the letters (Samsmra)

Books Six and Seven

(i) Rules dealing with doubling

(ii) Rules dealing with Sam-prasanna

(Iii) Rules dealing with Samhita

(iv) Rules dealing with augment (Agama)

(v) Rules dealing with accents; processes in the Purvapada

(vi) Rules dealing with phonological operations relative to pre-suffixes (Anga)

(vii) Rules dealing with operations relative to affixes, augments etc.

Book Eight

(i) Rules dealing with doubling (Dvitva) relative to Paada

(ii) Rules dealing with accents relative to Paada ; Samhita processes

(Iii) Rules dealing with phonological operations relative to Paada

(iv) Rules dealing with miscellaneous operations relative to Non-Paada

**

There is also another way of classifying the Astadhyayi into organizational units. The first is Saptadasapt-adhyayi (the first seven books and one quarter); and, the second is Tripadi (the last three quarters). It is said; the rules in the Tripadi stand suspended (A-siddha) by the rules of the preceding (Purva) first seven books and one quarter.

And, again, Tripadi is also constrained within itself (Atra). Its subsequent rules are, in turn, treated as suspended in view of its earlier rules.

The rules of the Asṭādhyāyī

The Aṣṭādhyāyī is a system (śāstra) of rules. Since its rules are structured with utmost brevity and clarity, Pāṇini chose to present them within the frame-work of a set of meta-rules conducive to interpretation and to application. Grammar, here, is a system (śāstra) of rules (lakṣaṇa) whose goal is to fully understand correct usage (lakṣya) of the words in a given context.

*

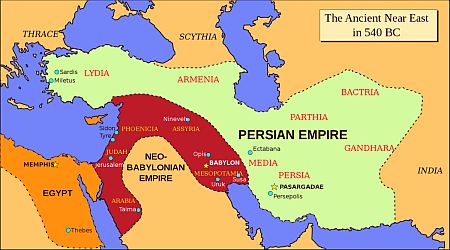

The general rules of Panini are applicable to both of the two major domains of Sanskrit usage- contemporary standard language; and,the language of the Vedic texts.

Panini primarily deals with the rules of the Sanskrit which were accepted by the social and linguistic elites of his time as being Sadhu-bhasha (correct) usages.

Those rules which applied only to the language of the Vedic texts were accordingly specified by stating the specific Vedic sub-domains.

The domain of the contemporary spoken standard Sanskrit was also then sub-divided into domains of regional and scholastic dialects.

Panini attempts to describe the known facts of Sanskrit in all their forms.

He describes the colloquial dialectal usages of Sanskrit; the Sanskrit of the Vedic texts (Chhandas); as also the preferred use of the standard Sanskrit by the well-informed persons (Sadhu-Bhasha) . The patterns of the usages of these forms are markedly different from each other .

*

The rules of the Asṭādhyāyī are of various types.

Starting with about 1700 basic elements like nouns, verbs, vowels, consonants, Panini puts them into classes. The construction of sentences, compound nouns etc. is explained as ordered rules, operating on a fundamental structures, in a manner similar to that of a modern theory.

As MacDonell explained: This arrangement of rules is not, however, stringently adhered to; Panini inserts unrelated rules which typically do follow a related train of thought, or which can be more effectively explained outside the context of the book to which they truly belong.

: – Samñjā, technical rules; rules which assign a particular term to a given entity. These form basic rules. Pāṇini assigns nearly one hundred technical terms (Saṃjñā), either to a linguistic form (śabda-rūpa), its meaning (artha), or to a sound quality (dhvani-guṇa).

: – Paribhāṣā, interpretive rules or meta-rules; rules which regulate proper interpretation of a given rule or its application. This sort of rule doesn’t address other rules: it addresses the person reading them. Such a rule tells us how we should read and understand the other rules in the Ashtadhyayi.

: – Adhikāra, heading rules; rules which introduce a domain of rules sharing a common topic, operation, input, physical arrangement, etc. This sort of rule specifies an idea that extends to the rules that follow it. Such a rule sometimes specifies how far it extends; but, usually its extension is clear from context. The range of rules over which an adhikāra rule applies is called its anuvṛtti.

: – Vidhi, operational rules; rules which directs how a given operation is to be performed on a given input. This sort of rule describes the way that Sanskrit actually behaves. It can describe such things as word formation, the application of sandhi, and so on. Most rules are like this.

: – Niyama, conditioning or restriction rules; rules which restrict the scope of a given rule. This sort of rule contradicts an earlier vidhi rule. Essentially, it contains an exception (Apavada)to an earlier rule.

: – Atideśa, extension rules; rules which expand the scope of a given rule, usually by allowing the transfer of certain properties which were otherwise not available. An Atideśa rule specifies that some feature has the properties of another. An Atideśa rule generally widens the scope of application of the definition or the operation of a rule. This is useful because the Ashtadhyayi contains complex rules that act on very specific terms. This rule changes the properties of ī within the system.

: – Pratisedha, negation rules; rules which counter an otherwise positive provision of a given rule. There are two kinds of negations: prasajya-pratiṣedha, where the negative is construed with the verb, yielding absolute negation; and, paryudāsa where the negative is construed with the noun, yielding a negation with the meaning of similar to but different from (tadbhinna-tatsaṛdśa).

: – Vibhāsā, A rule which offers options is termed Vibhāṣā ‘option’ (Na veti vibhāṣā). Three kinds of options are mentioned: Prāpta ‘that which is made available; Aprāpta ‘that which is not made available; and, Prāptā-prāpta that which is made available, and not made available, both.

: – Nipātana, Ad hoc rules; rules which provide forms to be treated as derived, even though the derivational details are missing – svarādi-nipātam avyayam. The Nipātana rules are said to accomplish three goals: Aprāptiprāpaṇa – providing something not made available by any other rule; Prāpti-vāraṇa – blocking something which is made available; and, Adhikārtha-vivakṣā, indicating something additional.

[Source: Indian Tradition Of Linguistics And Pāṇini by Prof. Rama Nath Sharma]

Among the rules of the Astädhyäyi, one may distinguish rules prescribing a grammatical operation (vidhi-sütra); rules defining a technical term (samjnä-sütra); meta-rules guiding the interpretation and application of the other rules (paribhäsä-sütra); and, headings (adhikära-süträ).

[Panini’s rules of grammar rely on two simple concepts: that all nouns are derived from verbs and that all word derivation takes place through suffixes. However, Panini does depart from these guidelines in some instances.]

The paribhāṣā or meta-rules aid in the interpretation of Sūtras, while the Adhikāra rules define the boundaries of domains. The Vidhi Vūtras or operational rules – aided by the conditioning rules and the extension rules – transform linguistic units and grammatical entities through affixation, augmentation, modification, and replacement (including deletion, because replacement by Lopa or zero-element is possible). Some rules are universal; while others are context sensitive; the sequence of rule application is clearly defined. Some specific rules can override other more general ones.

The scholar Katre observes: ” Panini has attempted to arrange his Sutras under two major headings: the first; a general rule, which encompasses the largest number of linguistic items; and, the second, an exception (Apavada), which covers a smaller group not subject to the general rule. These organizational systems, presumably intended to ease memorization. ” The later editors of the Astadhyayi did try to reorganize Panini’s arrangements.

Prof. Rama Nath Sharma writes, “Since Pāṇini formulated his rules based on his efforts to capture certain generalizations reflected in usage, he framed some rules with a general (sāmānya) scope of application. These rules are termed general (utsarga). These rules are generally operational (Vidhi) in nature.

He also formulated other rules, relative to utsarga rules (vikalpa); and, these commonly are termed specific (Viśeşa). There are also the relevant negative (niṣedha), restrictive (niyama) or extensional (atideśa) provisions. These rules define their scope within the scope of a general rule and often are treated as exceptions (Apavāda) to that rule.

Other types of specific rules in relation to sāmānya are negations (pratisedha) and options (Vibhāşā), etc. This clearly establishes a hierarchical relationship among rules.

From the point of view of the various strategies employed in the application of rules, one may also find rule types such as Nitya ‘obligatory’ , Para ‘ subsequent’ , Antaranga ‘ internally conditioned’ and Bahirahga ‘externally conditioned’.

These sets of rules (lakshana) with their application to a network of utterances lead to the derivation of correct words (lakṣya).

Dr.Émilie Aussant , in her scholarly paper -‘Sanskrit Grammarians and the ’Speaking Subjectivity’, writes :

The earliest extensive discussion of Panini’s rules which has come down to us is contained in the Vārttikas of Kātyāyana (3rd cent. B.C.); which themselves are known only as quoted and commented on in Patanjali’s Mahābhāṣya (2nd cent. B.C.).

Kātyāyana and Patanjali discuss the validity of various rules, their formulation and their relation to other rules. Discussing the Pāṇinian-sūtras is the occasion, for both grammarians, to develop some thoughts about different language facts. Human manifestations in language are one of them. Here, two points may be highlighted.

First, human subjectivity is sometimes referred to indicate language arbitrariness, either individual (such as word order), or collective (such as the word-meaning/object relation).

The second point concerns the importance of the authoritativeness of the speaker: in a context where linguistic, religious and social otherness is becoming stronger and stronger (as it probably was by Patanjali’s time), the identification of the norm and of its sharers is crucial.

After the Mahābhāṣya of Patanjali, the glossary of the subjectivity in language can be considered as definitely established. Very few new terms will appear with the later grammarians.

The various examples quoted above show that the linguistic levels where this subjectivity — either embodied in the individual speaker or in the speakers’ community — intervenes are syntax, morphology, gender and semantics.

Sutra

Majority of the Sūtras deal with a well ordered procedure, in order to derive word forms from the postulated root and a suffix; and, new roots from the old ones. These procedures are all modular, creating one or more sub-procedures to perform specific tasks.

Panini formulates his rules in three classes: General (Samanya); Particular (Visesha); and, the residual (Sesha). The basic purpose of Grammar, as Patanjali says, is to govern the words in a language; not by listing them out, but by formulating a set of General (Samanya) and Particular (Viseha) rules with their related exceptions (Apavada).

*

A Sutra is brief in form and precise in its function. Here, for the proper understanding of the Sutra, its context is a key-factor.

Almost every Sūtra in the Aṣṭādhyāyī is an elliptical sentence, which borrows meaning from the Sūtra or Sūtras before it. And, Pānini does not repeat a word common to several successive Sūtras; after using it once (this first mention is called Adhikāra, the beginning), he will omit the word thereafter. The implicit presence of the word is known as Anuvṛtti, recurrence.

A Sutra has to be comprehensive, objective, brief and precise. Panini chose the technique of context-sharing (eka-vakyata). Panini’s rules are interdependent. It is because of two reasons – physical nearness or the placement in a particular place; and, the other is functional through the criteria of Anuvrtti, which is now termed as ‘recurrence’.

The Anuvrtti controls the reading of a Sutra in conjunction with its preceding and subsequent Sutra. While a Sutra is governed by the General rule; it is also controlled by the exceptions (Apavada). The exceptions are more powerful that the General-rules.

And, within a domain, a prior rule is less powerful than its subsequent one (Vipratisedhe param karyam). Further, an exception (Apavada) is more powerful than its subsequent rule. And, the Residual rule (Sesha) covers whatever that was not covered by the General rule (Samanya) and the exceptions (Apavada) .

Prof. Rama Nath observes: The higher-level rules within the domain are brought close or within the context of the lower-level rule. This helps to reconstruct the shared-context of a given rule, within a domain; and, better interpretation of the lower-level rule.

The purpose of every rule is its application.

Thus, a Sutra, when fully equipped with all the information required for its application, becomes a statement; and, serves as a means (Upaya) towards the proper understanding of a sentence.

Discovering the Algorithm for Rule Conflict Resolution in the Aṣṭādhyāyī

According to a research paper published in Apollo—University of Cambridge Repository (2022). DOI: 10.17863/cam.80099

Indian PhD student Rishi Rajpopat, 27, decoded a rule taught by Panini, master of the ancient Sanskrit language who lived around two-and-a-half-thousand years ago, the report said, adding that Panini’s grammar, known as the Astadhyayi, relied on a system that functioned like an algorithm to turn the base and suffix of a word into grammatically correct words and sentences.

However, two or more of Panini’s rules often apply simultaneously; resulting in rule conflicts. Panini taught a “metarule”, traditionally interpreted by scholars as meaning “in the event of a conflict between two rules of equal strength, the rule that comes later in the grammar’s serial order wins”.

However, this often led to grammatically incorrect results. Rishi Rajpopat rejected the traditional interpretation of the metarule and argued that Panini meant that between rules applicable to the left and right sides of a word respectively, Panini wanted us to choose the rule applicable to the right side. And, using this reasoning, Rajpopat discovered that Panini’s algorithms can really generate words and phrases that are flawlessly grammatically perfect.

For instance; take the words “Mantra” and “Guru” as examples.

In the sentence “Devāḥ prasannāḥ mantraiḥ” (“The Gods [Devāḥ] are pleased [prasannāḥ] by the Mantras [mantraiḥ]”) we encounter “rule conflict” when deriving mantraiḥ “by the mantras.” The derivation starts with “mantra + bhis.” One rule is applicable to left part, “mantra’,”; and the other to right part, “bhis.” We must pick the rule applicable to the right part, “bhis,” which gives us the correct form, “mantraiḥ.”

And, while trying to create the word Guru in the sentence “Jñānaṁ dīyate guruṇā” (“Knowledge [jñānaṁ] is imparted [dīyate] by the Guru [Guruṇā]”). It is a well-known phrase that meaning “by the guru.”

The word’s basic elements are the Guruna; and, there are two rules that apply if one follows Panini’s instructions to produce the term that would imply “by the Guru” — one for the word “Guru” and one for “ā.”

We encounter rule conflict when deriving Guruṇā “by the Guru.” One rule is applicable to left part, “Guru”; and the other to right part. “ā“. We must pick the rule applicable to the right part, “ā,” which gives us the correct form, “Guruṇā.”

***

A major implication of Dr. Rajpopat’s interpretation is said to be that we now have the algorithm that runs Panini’s grammar; and, we could potentially teach this grammar to computers.

Dr. Rajpopat said, “Computer scientists working on natural language processing gave up on rule-based approaches over 50 years ago… So, teaching computers how to combine the speaker’s intention with Panini’s rule-based grammar to produce human speech would be a major milestone in the history of human interaction with machines, as well as in India’s intellectual history.”

****

[ For more on this, please check: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/332654 ]

If two rules are simultaneously applicable at a given step in a Pāṇinian derivation, which of the two should be applied? Put differently, in the event of a ‘conflict’ between the two rules, which rule wins? In the Aṣṭādhyāyī, Pāṇini has taught only one metarule, namely, 1.4.2 vipratiṣedhe paraṁ kāryam, to address this problem.

Traditional scholars interpret it as follows: ‘in the event of a conflict between two rules of equal strength, the rule that comes later in the serial order of the Aṣṭādhyāyī, wins.’ Pāṇinīyas claim that if one rule is nitya, and its simultaneously applicable counterpart is anitya, or if one is antaraṅga and the other bahiraṅga, or if one is an apavāda (exception) and the other the utsarga (general rule), then the two rules are not equally strong and consequently, we cannot use 1.4.2 to resolve the conflict between them. The nitya, antaraṅga and apavāda rules are stronger than their respective counterparts and thus win against them.

But this system of conflict resolution is far from perfect: the tradition has had to write numerous additional metarules to account for umpteen exceptions. In this thesis, I propose my own solution to the problem of rule conflict which I have developed by relying exclusively on Pāṇini’s Aṣṭādhyāyī.

I replace the aforementioned traditional categories of rule conflict with a new classification, based on whether the two rules are applicable to the same operand (Same Operand Interaction, SOI), or to two different operands (Different Operand Interaction, DOI). I argue that, in case of SOI, the more specific i.e., the ‘exception’ rule, wins.

Additionally, I develop a systematic method for the identification of the ‘more specific’ rule – based on Pāṇini’s style of rule composition. I also argue that, in order to deal with DOI, Pāṇini has composed 1.4.2, which I interpret as follows: ‘in case of DOI (vipratiṣedha), the right-hand side (para) operation (kārya) prevails.’

I support my conclusions with both textual and derivational evidence. I also discuss my interpretation of certain metarules teaching substitution and augmentation, the concept of aṅga, and the asiddha and asiddhavat rules and expound on not only their interaction with 1.4.2 but also their influence on the overall functioning of the Pāṇinian machine.

We must understand , the Ashtadhyayi is basically a list of rules. But these rules, too, are lists: of verbs, of suffixes, and so on. These lists have different headings, and these headings describe the behaviour of the items they contain. But the Ashtadhyayi is more complicated than this: ideas in one rule can carry over to the next, or to the next twenty; basic words have specialized meanings; and rules in one chapter may control rules in another. In this way, Panini created a brief and immensely dense work. Thus, we have a large arrangement of different rules that we must try to understand.

Panini ‘s work , obviously, is difficult. His work is not something you can read through from beginning to end. Rather, it essentially assumes that you’ve read it critically and cyclically, checking the Sutras back and forth with caution. By doing so, we’ll stand to gain the true understanding of Panini’s system; and , the abstract framework that supports it.

*

To the extent that the Astadhyayi addresses word meanings, Panini also chooses to accept the dictates of common usage over those of strict derivation. It is said; that in Grammar ” the authority of the popular usage of words … must supersede the authority of the meaning dependent on derivation. The meanings of words (the relations between word and meaning) are also to be established by popular usage.”

One of the aims of Grammar is to formulate rules having a well defined scope of application, so that they can capture usage in its reality.

Accordingly, Panini gives preference to the language as it was actually spoken by the educated ; instead of adhering completely to the intellectually defined rules. This exemplifies the innovative feature of his work.

*

Unlike the Nirukta and Mimämsä, Panini is not overtly interested in the language of the Vedic texts; but, he also gives importance to the language in use among the well-educated (Sista) of his time. He gives preference to common usage over those of strict derivation (etymology)

The Astadhyayi is the first major work on grammar in any language; and , has been the guiding principle for generations of Indian grammarians; and, it is still studied by both Eastern and Western linguists today. Incidentally, it also enhanced Sanskrit’s potential for its scientific use.

As Katre observed, “In a work of such magnitude which covers every aspect of the author’s speech community … there is indeed much scope to find some overstatements as well as understatements. But none of this takes away from the credit which is due to Panini who, in this astounding work, has set up a model which is fully adequate to cover every aspect of the language described.”

The preeminence of the Astadhyayi in the development of not only Sanskrit, but of the grammar of all languages, cannot be denied. Predating even the early Greek’s examination of language, Panini’s work continues to exert influence in the realm of linguistics even 2,000 years after its composition.

**

Hartmut Scharfe in his Grammatical Literature (Otto Harrassowitz, 1977), writing about Panini, concludes, saying :

The last decades have seen a revival of Paninian studies, both in India and the West (notably in the USA) . This stretches from antiquarian interest to studies on his Grammatical theory and method of description.

The problem in studying Panini’s method has often been a premature identification with one’s own theories. We have to first find out what Panini’s conceptions are before we can use them to support our own.

The attempt of the Indian scholars to improve our understanding of the Rigveda has not yielded the hoped results; while the comparison of Panini’s language with the Middle- Indo-Aryan language has not been pursued vigorously.

Sources and References

- The Ashtadhyayi of Panini. Translated into English by Srisa Chandra Vasu

Published by Sindhu Charan Bose at The Panini Office, Benares – 1897 - Panini

- Panini –His place in Sanskrit Literature by Theodor Goldstucker, A.Trubner & Co., London – 1861

- Simulating the Paninian System of Sanskrit Grammar by Anand Mishra

- India as Known to Pānini by V. S. Agrawala, Lucknow University of Lucknow, 1953

- Computing Science in Ancient India by Professor T.R.N. Rao and Professor Subhash Kak

- Panini’s Grammar and Computer Science by Saroja Bhate and Subhash Kak

- How Sanskrit Led To The Creation Of Mendeleev’s Periodic Table

- Indian Tradition of Linguistics and Pānini by Prof. Rama Nath Sharma

- Pāṇini: Catching the Ocean in a Cow’s Hoofprint by Vikram Chandra

- Panini: His Work and Its Traditions by George Cardona

- A Brief History of Sanskrit Grammar by James Rang

- Introductionto Prakrit by Alfr ed C . Woolner

- Chandah Sutra of Pingala Acharya, Edited by Pandita Visvanatha Sastri , Printed at the Ganesha Press, Calcutta – 1874

- ALL IMAGES ARE FROM INTERNET