As mentioned earlier, Bhāskararāya Makhin was essentially a Shakta; and was also an ardent Sri Vidya Upasaka. He adopted the Tantra approach in his spiritual pursuit. And, in his Guptavati, he reveres Devi Mahatmya as a mantra of the Devi, embodying her divine presence.

The Tantra School recognizes Vac as the embodiment of the Shakthi. It is the bridge between the physical and the formless Reality. Bhāskararāya approaches the text of the Devi Mahatmya as “the mantra whose form is a multitude of verses (ślokas), consisting of three episodes (caritas), each one describing the glory of one of the three different aspects of the Supreme Goddess – Maha-Kali, Mahālakṣhmī and Maha-Sarasvathi.

[The term Mantra is explained as mananat trayate mantrah; the contemplation of which liberates. It is the harmonious and powerful union of mind (Manas) and word (Vac). It is the living sound, transcending beyond the mental plane. , its relevance is in its inherent Shakthi. Its subtle sounds attempt to visualize the un-differentiated divine principle. Mantra is beyond intellect. Its inner essence has to be grasped in humility, earnestness and faith.

Mantra is said to connect, in a very special way, the objective and subjective aspects of reality. The Mantra, in its sublime form, is rooted in pure consciousness. The Shaiva text Shiva Sutra describes Mantras as the unity of Vac and consciousness:

Vac-chittam (ārādhakasya cittaṃ ca mantras tad dharma yogataḥ– Shiva Sutra: 2.1).

It is the living sound, transcending beyond the mental plane; the indistinct or undefined speech (anirukta) having immense potential. In its next stage, it unites harmoniously with the mind. Here, it is union of mind (Manas) and word (Vac). That is followed by the Mantra repeated in the silence of one’s heart (tushnim). The silent form of mantra is said to be superior to the whispered (upamasu) utterance.

If an idol or a Yantra is the material (Sthula) form of the Goddess, the Mantra is her subtle form (Sukshma-rupa). And, beyond that is the Para, the contemplation, absorption into the very essence of the Devi. And, that leads to the realization (Anubhava) of the bliss (Ananda) of one’s identity with her (Pratyabhijna).

It is said; when one utters a deity’s Mantra, one is not naming the deity, but is evoking its power as a means to open oneself to it. It is said; mantra gives expression to the identity of the name (abhidana) with the object of contemplation (abhideya). Therefore, some describe mantra as a catalyst that’ allows the potential to become a reality’. It is both the means (upaya) and the end (upeya).

The reverse is said to be the process of Japa (reciting or muttering the mantra). It moves from Vaikhari through Madhyamā towards Pashyanti ‘ and , ideally, and in very rare cases, to Para vac.

Ordinarily, Japa starts in Vaikhari form (vocal, muttering). The efficacy of the Japa does depend on the will, the dedication and the attentiveness of the person performing the Japa. After long years of constant practice, done with devotion and commitment, an extraordinary thing happens. Now, the Japa no longer depends on the will or the state of activity of the practitioner. It seeps into his consciousness; and, it goes on automatically, ceaselessly and inwardly without any effort of the person, whether he is awake or asleep. Such instinctive and continuous recitation is called Ajapa-japa. When this proceeds for a long-time, it is said; the consciousness moves upward (uccharana) and becomes one with the object of her or his devotion.

The term Ajapa-japa is also explained in another manner. A person exhales with the sound ‘Sa’; and, she/he inhales with the sound ‘Ha’. This virtually becomes Ham-sa mantra (I am He; I am Shiva). A person is said to inhale and exhale 21,600 times during a day and night. Thus, the Hamsa mantra is repeated (Japa) by everyone, each day, continuously, spontaneously without any effort, with every round of breathing in and out. And, this also is called Ajapa-japa.]

Bhāskararāya asserts that the Goddess is present in every word and every sound of the Devi Mahatmya; and, the recitations of these words can reveal her. Thus, he reveres the Devi Mahatmya as a great Mantra-maya scripture, as also an esoteric text on Yoga Shastra and Sri Vidya.

The Devi Mahatmya or Durga Saptashati is treated like a Vedic hymn, rik or a mantra. Each of its episodes (charita) is associated with a Rishi (the sage who visualised it), a Chhandas (its meter), a presiding deity (pradhna-devata), and viniyoga (for japa). For instance; for the first episode (Prathama-charita), the Rishi is Brahma; the Devata is Mahakali; the Chhandas is Garyatri; its Shakthi is Nanda; its Bija is Raktha-dantika; and its Viniyoga is securing the grace of Sri Mahalakshmi. The first Chapter is compared to Rig-Veda.

asya śrī prathama caritrasya । brahmā ṛṣiḥ । mahākālī devatā । gāyatrī chandaḥ । nandā śaktiḥ । raktadantikā bījam । agnis tattvam । ṛgvedaḥ svarūpam । śrī mahā kālī prītyarthe prathama caritra jape viniyogaḥ ।

Further, it is said that every sloka of the Devi-Mahatmya is a Mantra by itself. And, the whole text is treated like one Maha mantra.

For instance; the opening sloka of the Devi Mahatmya: “Savarnih suryatanayo yo manuh Kathyate-shtamah” is ordinarily taken to mean “Listen to the story of the king who is the eighth Manu”. But, Sri Swami Krishnananda explains, it is in fact a mantra; and its Tantric interpretation is: “Now, I shall describe to you the glory of Hreem“. The Swami explains; Ha is the eighth letter from among: Ya, Ra, La, Va, Sya, Sha, Sa, and Ha. And add to that ‘Ram’ the Bija of Agni and one hook to make ‘Hreem’. Here, Hreem is the Bija-mantra of Devi; and, is equivalent to Pranava mantra Om

[It is said; the first three Slokas of Saptashati give out in code, the Navarna Mantra: oṃ namaścaṇḍikāyai || oṃ aiṃ mārkaṇḍeya uvāca ॥]

Bhaskararaya concludes just as there is no difference between the cause (karana) and the effect (karya); between the object signified (Vachya) and the word which signifies (Vachaka); and between Brahman and the universe ((Brahmani jagat ithyartha, abedho iti seshaha), similarly this Vidya (Devi Mahatmya) of the Devi is identical with her.

The narration of the Devi Mahatmya is interwoven with four sublime Stutis, hymns. While the majority of the verses in the text are in the simpler Anushtup Chhandas, the Stutis are composed in more elegant Chhandas such as Gayatri, Vasantatilaka and Upajati, creating graceful, complex, supple rhythmic patterns when sung with fervour, gusto and reverence.

These four Stutis celebrate the glory and splendour of the auspicious Devi in all her aspects. These sweet, powerful and uplifting hymns are not only devotional and poetic, but are also philosophical and sublime. Bhaskararaya Makhin regards these hymns as Sruti-s (revealed wisdom), the exalted revealed (Drsta) knowledge, equalling the Vedas (apauruṣeya), rather than as constructed, the Krta by humans.

Bhaskararaya, in his Guptavati, offers comments on 224 out of the 579 verses of the Devi Mahatmya. The most commented Chapters of the Devi Mahatmya are: 5, 4, 12, 11 and 1, in that order. These are the Chapters that contain the four celebrated hymns and also the instructions for reciting the Devi Mahatmya.

The four hymns are:

(1) Brahma-stuti (DM. 1.73-87) starting with tvaṃ svāhā tvaṃ svadhā tvaṃ hi vaṣaṭkāraḥ svarātmikā;

(2) the Sakaradi-stuti (DM.4.2-27) starting with śakrādayaḥ suragaṇā nihate’tivīrye;

(3) the Aparajita-stuti (DM.5.9-82) starting with namo devyai mahādevyai śivāyai satataṃ namaḥ ; and,

(4) the Narayani-stuti (DM.11. 3-35) starting with Devi prapannārtihare prasīda.

[The Brahma-stuti (DM.1.73-87) also known as the Tantrika Ratri Suktam, establishes the Divine Mother’s ultimate transcendence and her identity as the creator and sustainer and the dissolver of the Universe. She is the all compassing source of the good and the evil, alike; both radiant splendour and terrifying darkness. And yet, she ultimately is the ineffable bliss beyond all duality.

In the longest and most eloquent of the Devi Mahatmya’s four hymns, richly detailed Sakaradi-stuti (DM.4.3-27) Indra and other gods praise Durga’s supremacy and transcendence. Her purpose is to preserve the moral order, and to that end she appears as ‘good fortune in the dwelling of the virtuous; and, misfortune in the house of the wicked’, granting abundant blessings and subduing misconduct (DM.4.5). ‘Every intent on benevolence towards all’ (sarvo-upakāra-karaṇāya sadārdracittā DM.4.17), she reveals even her vast destructive power as ultimately compassionate, for in slaying those enemies of the world who ‘may have committed enough evil to keep them long in torment’ (kurvantu nāma narakāya cirāya pāpam – DM.4.18) , she redeems them with the purifying touch of her weapons so that they ‘may attain the higher worlds’ (lokānprayāntu ripavo’pi hi śastrapūtā/ itthaṃ matirbhavati teṣvahiteṣu sādhvī –DM.4.19).

The Devas, distressed that the Asuras have re-grouped and once again overturned the world-order, invoke the Devi in a magnificent hymn, the Aparajita-stuti or Tantrika Devi Suktam, the twenty slokas beginning with ‘ya devi sarva bhuteshu , praise to the invincible Goddess , which celebrates her immanent presence in the Universe as the consciousness that manifests in all beings (yā devī sarvabhūteṣu cetanetya abhidhīyate) . In these forceful 24 stanzas ( 19 to 42 of the Fifth Adhyaya ), the Devi is described as present in all forms of life , sensations and matter as : Maya, Consciousness, Intelligence, Sleep, Hunger, Shadow, Power, Thirst, Patience; Birth, Modesty, Peace, Charm, Fortune, Firmness, Activity, Memory, Compassion, Memory, Satisfaction, Mother, Error, Inheritance, Thinking . Thereupon the Devi appears on the banks of the Ganga. Her radiant manifestation emerging from the body of Parvathi embodies the Guna of Sattva, the pure energy of light and peace. Later, She takes on multiple and varied forms in the course of the battle with the Asuras.

The final hymn, the Narayani-stuti (DM.11.3-35) lauds the Devi in her universal, omnipresent aspect and also in the diverse expressions of her powers .Thereupon, the Devi assures to protect all existence and to intervene whenever evil arises.]

These hymns describe the nature and character of the Goddess in spiritual terms:

Bhāskararāya identifies Chaṇḍikā-Mahālakṣhmī with the hymn of the fifth chapter Aparajita-stuti; and, her three forms (Mahākālī, Mahālakṣhmī, and Mahāsarasvatī ) with one of the other three hymns each.

In his introduction to the Guptavati, Bhāskararāya emphasises the role of mantras that produce power when properly employed. Therefore, he focuses, particularly, on the Navarna mantra, apart from the Devi Mahatmya, which itself is regarded as a Maha Mantra.

The Navarna Mantra or Navakshari mantra, also known as Chamunda Mantra or Chandi Mantra is the basic mantra of the Sri Durga Saptashati recitation. It is also one of the principal (mula) mantras in Shakthi worship, apart from the Shodasi mantra of the Sri Vidya. There is the faith that one who practices the Navakshari mantra with great devotion will attain liberation and the state of highest bliss -(Vicche Navārnak’ornah syān-mahad’ānanda-dāyakah)

According to the Navakshari mantra nivechanam (p24) : Its Rishi is Markandeya; Its Chhandas is Jagati; Durga, Lakshmi and Sarasvathi are its Devathas; Hram is its Bija ; Hrim is its Shakthi; Hrum is its Kilaka; and, securing the grace (prasada siddhi) of Durga, Lakshmi and Sarasvathi is its Viniyoga.

Asya Sri Navakshari Maha-mantrasya / Markandeya Rishihi / Jagati Chhandah / Durga Lakshmi Sarasvathi Devata // Hram Beejam / Hrim Shakthihi / Hrum Kilakam // Durga Lakshmi Sarasvathi Prasada Sidhyarthe Jape Viniyogaha //

And, Navarna or Navakshari mantra is chanted as an integral part (Anga) of Chandi–parayanam, which is performed while reciting (Purashcharana) the Devi Mahatmya. There is also a practice of the reciting of Durga Saptashati as a part of Navarna Purashcharana. Thus, the Saptashati and the Navarna are mutually related (angangi nyaya).

In the Sri Vidya tradition, the Panchadasi (Pancha-dasakshari) and the Shodasi are the cardinal and exclusive (rahasya) Mantras. The Panchadasi mantra of very potent fifteen letters or syllables (Bijakshara) composed of three segments (kūṭa) is indeed the very heart of the Sri Vidya Upasana.

Its three kūṭas are:

- Vāgbhava kūṭa of five bīja-s (ka – e – ī – la- hrīṁ, क ए ई ल ह्रीं);

- Madhya or kamaraja kūṭa of six bīja-s (ha – sa – ka – ha – la – hrīṁ, ह स क ह ल ह्रीं ) ; and,

- the śhakti kūṭa of four bīja-s (sa – ka – la – hrīṁ, स क ल ह्रीं ).

The mantra is composed of a series of individual Bija-akshara (syllables), each having its own identify and association; and, each representing a certain aspect of the Goddess. But, when these Bija-aksharas are taken together, they manifest the subtle form (Sukshmarupa) of the Mother Goddess.

This fifteen lettered Pancha-dasakshari mantra is revered as the verbal form of the Mother Goddess. By adding to it the secret syllable śrīṁ (श्रीं) it is transformed into the sixteen lettered Shodasi mantra. The Bijakshara śrīṁ (श्रीं) is regarded as the original form of the Mother Goddess Sri.

The mantra which till then was dormant becomes explicit by adding śrīṁ (श्रीं); and, the knowledge of her is celebrated as Sri Vidya. It is with this Vidya of Shodasi mantra that the Mother Goddess is worshiped through the Sri Chakra. It is said; this mantra is known as Ṣhoḍaśī or Shodasa-kala-vidya, because each of its sixteen Bījas represents a phase (kalā) of the moon. It is also said; the verbal expression of her Vidya is the Shodasi mantra; and, its visual expression is the Sri Yantra (Sri Chakra). And, the two are essentially the same.

The Navarna (also known as Navakshari and Chandi Gayatri) mantra of nine syllables is closely related to the extended Maha-shodasi mantra of twenty eight bīja-s of Sri Lalitha tradition. Both are Navarna; as they are worshiped in nine levels (Nava–avarana), where the Devi is worshipped in her nine forms. It is described as a mantra that grants the highest bliss – mahad-ananda dayakah.

[The Mahāṣoḍaśī mantra is actually not sixteen; but , it is a set of six kutas ( sections) :(1) srim, hrim, klim , aim sauh ; (2) aum hrim srim ; (3) ka e i la hrim ; (4) ha sa ka ha la hrim ; (5) sa ka la hrim ; and, (6) sauh aim klim hrim srim . Thus Mahāṣoḍaśī has twenty eight bīja-s.]

While Sri is the presiding deity of the Sri Vidya; Chandi is the Goddess of the Chandi Vidya. There is also a view which asserts that the Chandi Vidya is the older tradition and, the Sri Vidya is its refined form. In some places (for instance, in Kanchi), both Chandi Navarna and Sri Vidya worship procedures are followed.

Bhāskararāya, a dedicated Sri Vidya Upasaka, in his Guptavati equates Chandi with the Supreme Goddess Devi who indeed is the Brahman, the Supreme non-dual reality. He regards the Chandi Vidya as the Navarna Vidya, which corresponds to the Vidya of Sri Lalitha.

![]()

The Navārna-mantra (Śrī Chaṇḍi Navākṣharī Mantraḥ) is composed of the following syllables: Om aiṁ hrīṁ klīṁ cāmuṇḍāyai vicce – ॐ ऐं ह्रीं क्लीं चामुण्डायै विच्चे ॥

The syllables of the Navārna mantra are taken from the first line of the Mahāṣoḍaśī mantra — śrīṁ – hrīṁ – klīṁ – aiṁ – sauḥ (ॐ श्रीं ह्रीं क्लीं ऐं सौः)

The Shakthas have an immense faith that Navarna mantra has the power to bestow liberation (Mukti).

Bhaskararaya mentions that this mantra has been explained in one of the Shaktha Upanishads the Devī-Atharva-Śirṣa-Upaniṣhad (Devi Upanishad) from which he quotes the first verse “I am of the very same form (Svarupini) of the Brahman’. I am an aspect of Brahma. From me this Universe, in form of Prakriti and Purusha, is generated; which is both void and non-void.

sābravīt- ahaṃ brahma–svarūpiṇī । mattaḥ prakṛti –puruṣātmakaṃ jagat । śūnyaṃ cāśūnyam ca

I am both bliss and non-bliss. I am knowledge and non-knowledge. I am Brahma and non-Brahma (the non-manifest state called A-Brahma). I am the five primordial principles and non-principles. I am the whole perceived Universe.

aham ānandā qnānandau । ahaṃ vijñānāvijñāne । ahaṃ brahmā brahmaṇī veditavye । ahaṃ pañcabhūtānyapañcabhūtāni । ahamakhilaṃ jagat ॥3॥

The Devi Upanishad or Devi Atharvashirsha Upanishad explains the Navarna mantra Om aiṁ hrīṁ klīṁ cāmuṇḍāyai vicce:

- 1. Om – the Pranava Mantra represents the Nirguna Brahman;

- 2. Aim – is the Vakbija the seed sound of Mahasarasvathi—the knowledge that is consciousness. – Chit;

- 3. Hreem –the Maya Bija the sound of Mahalakshmi – the all pervasive existence. —Sat;

- 4. Kleem – is the Kamabeeja the seed sound of Mahakali – the all consuming delight – Ananda;

- 5. Chamunda – the slayer of the demons Chanda and Munda, representing passion and anger ;

- 6. Yai– the one who grants boons;

- 7. Vicce– in the body of knowledge, in the perception of consciousness.

The Chit, Sat and Ananda are involved in the creation in physical, vital, and mental aspects – as Anna, Prana and Manas. They all are integrated into Chamunda Devi.

[The meaning of the Navarna mantra is said to be : ‘O the Supreme Spirit Mahasarasvathi, O the purest and most propitious Mahalakshmi, O embodiment of joy Mahakali, to achieve the highest state of knowledge we constantly meditate upon You. O Goddess Chandika who embodies the three formed Mahasarasvathi-Mahalakshmi-Mahakali, obeisance to you! Please break open the tightened knot of ignorance and liberate us’]

vāṅmāyā brahmasūstasmāt ṣaṣṭhaṃ vaktrasamanvitam / suryo ̕vāma śrotra bindu saṃyukta ṣṭāttṛtīyakaḥ । nārāyaṇena saṃmiśro vāyuścādharayuk tataḥ / vicce navārṇako ̕rṇaḥ syānmahadānandadāyakaḥ ॥20॥

The Siddha Kunjika Stotra is a well known Tanric stotra, which occurs in the Gauri Tantra (section) of Rudra-yamala Tantra. It is in the traditional format of a Samvada, a discourse that takes place between an enlightened Guru and an ardent disciple- śrīrudrayāmale gaurī-tantre śiva-pārvatī-saṃvāde kuñjikā-stotraṃ.

The Kunjika Stotra, per se, is short, running into just eight verses. And, it is submitted to the most glorious Devi Chamunda, in all her varied forms.

Here, Lord Shiva, the Adi Guru, imparts instructions to his consort Parvathi; and, extols the virtues of the Kunjika Stotra.

Shiva mentions that the mere chanting of the most sublime (uttamam) and exclusive (ati guhyataraṃ) Kunjika Stotra, confers on the devotee the benefits that would accrue by the recital of the Durga Paatha (Durga Sapta Shathi) – kuñjikā-pāṭha-mātreṇa durgā-pāṭha-phalaṃ labheth.

Right at the at the outset, Shiva clarifies that the Kunjika Stotra is simple, direct and very effective. Its recital need not be prefaced with the usual citing, such as the Kavacha, Argala, Keelaka, Rahasyaka, Sukta, Dhya, Nyasa etc.

na kavacaṃ nārgalāstotraṃ kīlakaṃ na rahasyakam । na sūktaṃ nāpi dhyānaṃ ca na nyāso na ca vārcanam ॥ 2॥

And yet, it is powerful; it protects the devotee (pāṭhamātreṇa saṃsiddhyet); and, drives away all sorts of evil or negative influences that might hinder the devotee’s progress.

It is also said; the Kunjika Stotra encapsulates the essence of the Chandi paatha; as also that of the Navarna Mantra. In fact, the mantra segment of the Kunjika Stotra commences with the chanting of the Navarna Mantra: Om̃ aiṃ hrīṃ klīṃ cāmuṇḍāyai viccey.

Therefore, the Kunjika Stotra is chanted both at the commencement of the recital of the Durga Saptashati (प्रथम चरित्र); as also towards its conclusion.

It is said; the term Kunjika suggests the meaning of the Key that unlocks the powers of the Chandi Paatha. The prefix ‘Siddha’ implies that the stotra leads to the attainment of the ideal state.

It is also said; Kunjika, here, is in form of the Devi Chamunda, the Supreme Goddess; and, there is nothing beyond Her (Anuttara).

While invoking the Devi Chamunda, the Kunjika Stotra also explains the meaning of the syllables (Bija mantras) in the Navarna Mantra – Om̃ aiṃ hrīṃ klīṃ cāmuṇḍāyai viccey.

Accordingly, the Bija mantra Aim stands for the power and the creative aspect of the Devi (aiṅkārī sṛṣṭ–irūpāyai); the Bija Hrim is the form of the Devi , who protects and sustains all this existence (hrīṅkārī pratipālikā); the Bija Klim, symbolizes her all pervasive existence embodying and energizing every being and every aspect of the universe (klīṅkārī kāmarūpiṇyai bījarūpe); Chamunda is the mighty Devi who destroys the evil forces; and , confers grace and blessings on all (cāmuṇḍā caṇḍaghātī ca yaikārī varadāyinī); and, Vicchey is the merciful aspect of the Devi Chamunda who liberates from darkness and delusions.

aiṅkārī sṛṣṭirūpāyai hrīṅkārī pratipālikā । klīṅkārī kāmarūpiṇyai bījarūpe namo’stu te ॥ 8॥ cāmuṇḍā caṇḍaghātī ca yaikārī varadāyinī । vicce cābhayadā nityaṃ namaste mantrarūpiṇi ॥ 9॥

*

[According to the learned Animesh Nagar , there are different versions of the Kunjika Tantra; depending upon the Sampradaya (tradition) and/ or Guru-parampara (master-pupil lineage) that is followed.

The known versions of the Kunjika Stotra are said to be: Gauri-tantrokta; Damara – tantrokta; Kali- tantrokta: Bagla-tantrokta; and , the Siddha- SarasvatI – tantrokta .

For instance; it is said, the Kali-tantrokta version is highly tantric ; and, is embedded (garbhasta) with Matrika mantras. And, the Damara version focuses on the Siddhi aspect; and, aims to unlock the secrets of the Durga Saptashati.

Bhaskararaya explains: Even Brahma and the other Devas do not know Her real form; and, therefore, she is called Ajñeya. We do not find its limit, so she is called Ananta. We cannot find the meaning, so she is called Alakshya. Her birth is not known, so she is called Aja. She is found everywhere, so she is called Eka, the One. She has taken up all the various forms, so she is called Naika. Because of this she is called these various names.

yasyāḥ svarūpaṃ brahmādayo na jānanti tasmāducyate ajñeyā ।

yasyā anto na labhyate tasmāducyate anantā । yasyā lakṣyaṃ nopalakṣyate tasmāducyate alakṣyā ।

yasyā jananaṃ nopalabhyate tasmāducyate ajā । ekaiva sarvatra vartate tasmāducyate ekā ।

ekaiva viśvarūpiṇī tasmāducyate naikā । ata evocyate ajñeyānantālakṣyājaikā naiketi ॥23॥

As regards the Mantra aspect of the text, Bhaskararaya, following the Sri Vidya tradition, regards the Navarna mantra as the subtle form (sukshmarupa) of the Goddess. For Bhaskararaya, the Bijaksharas of the mantra are the more accessible forms of the Goddess’s ultimate form as Brahman.

Bhaskararaya analyses the Navarna-mantra, dedicated to the Great Goddess Chamunda, syllable-by-syllable, beginning with Chamundayai. He explains that the power of the mantra is particularly associated with the recitation of the name Chamunda.

In his introduction to the Guptavati, Bhaskararaya explains the etymology of the name Chamunda. Here, he differs from the explanation provided in chapter seven of the Devi Mahatmya.

According to the text of the Devi Mahatmya, Kali is celebrated as Chamunda after she overpowers and beheads Chanda and Munda.

śiraścaṇḍasya kālī ca gṛhītvā muṇḍameva ca । prāha pracaṇḍā aṭṭahāsa miśra mabhyetya caṇḍikām ॥ 7.23॥

The Devi, then, declares that since Kali presented her with the heads of these two demons, she would henceforth be renowned in the world as Chamunda – cāmuṇḍeti tato loke khyātā Devī bhaviṣyasi .Thereafter in the text, Kali and Chamunda become synonyms.

Yasmāc-Caṇḍaṃ ca Muṇḍaṃ ca gṛhītvā tvamupāgatā । Cāmuṇḍeti tato loke khyātā Devī bhaviṣyasi ॥ 7.27॥

Bhaskararaya Makhin, however, interprets the term Chamunda, differently, as: ‘chamum, ‘army’ and lati, ‘eats’; meaning that Chamunda is literally ‘she who eats armies’—a reference to Kali as Chamunda who drinks the blood of the army of the demon Raktabija.

jaghāna raktabījaṃ taṃ cāmuṇḍā apītaśoṇitam । sa papāta mahīpṛṣṭhe śastra saṅghasam āhataḥ ॥ 8.61॥

He then proceeds in his comments on the mantra by elaborating on the first three syllables (Bijakshara): Aim, Hrim, and Klim, by resolving the complex expressions into simpler or more basic ones: marked by analytical reasoning. He brings into the discussion the concepts and the symbolisms of the Sri Vidya traditions.

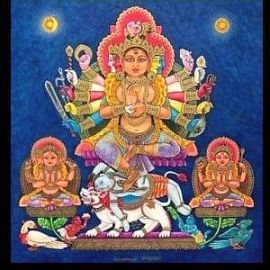

Here, he explains; the Mahadevi Chamunda, in her integrated form (Samasti) is of the nature of the Brahman- Brahma-svarupini. And, the three Bijaksharas in the Navarna-mantra symbolize the diversified (Vyasti) form of the Devi: as Aim (ऐं) for Mahalakshmi; and, Hrim (ह्रीं) and Kilm (क्लीं) for Mahasarasvathi and Mahakali, respectively. And again, the essential nature of the Devi as Sat-Chit-Ananda (being, consciousness, and bliss) is associated with each of her forms: Mahalakshmi (Sat); Mahasarasvathi (Chit); and Mahakali (Ananda).

Again, it is said, these three goddesses are the presiding deities of the three Episodes of the Devi Mahatmya, while the text itself is the body of the Devi Chamunda, the Mahadevi. Thus, the divisions and the Chapters of the Devi Mahatmya are but visible (Sakara) the constituents (anga) of the Devi Chamunda, who herself is beyond attributes (Brahma-svarupini).

Thus, Bhaskararaya relates the Vyasti goddess, their corresponding Bija–mantras, their symbolisms and sounds, to the most subtle, secretive aspect of the Supreme Goddess. As regards the Vyasti goddess, he follows the explanations given in the Devi Upanishad. But, as said earlier, he differs on its explanation of the term Chamunda.

Here, the Mahadevi Chamunda, in her integrated form (Samasti) is of the nature of the Brahman- Brahma-svarupini. She combines in herself her other diversified (Vyasti) forms of Mahalakshmi (Aim); Mahasarasvathi (Hrim); and, Mahakali (Kilm).

Bhaskararaya, however, offers a rather lengthy explanation on the final term of the Navarna mantra:’ vicce’.

He points out that the term vicce , at first instance, might look as though it is untranslatable. But, one would appreciate its significance when its etymology is correctly understood.

Bhaskararaya begins his explanation of vicce, by equating it with the Sanskrit word ‘manch’—meaning ‘to grow’ or ‘to move’. He remarks; though the term vicce is rather unusual, yet it has been in use in the Shakta tantric tradition. For instance, he says, the mantra of Bhagamalini, the second of the sixteen Nityas, reads ‘Amogham chaiva vichcham cha tatheshim klinna devatam’. The import of the mantra is said to be: the goddess symbolized by the Bija-akshara Klim is resplendent and unfailingly liberates (vichcham) the devotee.

[In the Sri Vidya tradition, the sixteen guardian deities, named as Nityas, who form the entourage, of the Devi, are identified with the phases of the moon (Chandra-kalaa); and each Nitya corresponds to a day (tithi) or the aspect of the moon during the fortnight. The sixteen Nityas are: Kameshvari, Bhagamalini, Nityaklinna, Bherunda, Vahnivasini, Mahavajeshvari, Dooti, Tvarita, Kulasundari, Nitya, Nilapataka, Vijaya, Sarvamangala, Jwalamalinika and Chitra]

Regarding the etymology of the term vicce, Bhaskararaya explains that it originated within the Dravidian language group; and, was later adopted into the Sanskrit vocabulary. He also mentions that importing terms from other languages (bhasha-mishrana) is not unusual; and, has been in practice since the ancient times. He explains that many of the terms that are used in Navarna and Bhagamalini mantras are well recognised in Southern languages like Kannada (karnatabhasha), Tamil (Dravidabhasha) and Telugu (Andhrabhasha).

The scholars surmise that Bhaskararaya might have related the term vicce with the Tamil word vichchu/i or vittu/i, meaning ‘to sow’ or ‘to spread’, which has the same connotation as his Sanskrit gloss manch, meaning ‘to grow’ or ‘to move’. They cite another obscure word ‘Puruchi’, which occurs only two times in the Rig-Veda . The term ‘Puruchi’, here, suggests the meaning of ‘Foremost or abundant‘, which carries a similar meaning in the Tamil language.

[śataṃ jīvantu śaradaḥ purūcīr antar mṛtyuṃ dadhatām parvatena || RV_10,018.04c|| and aśvinā pari vām iṣaḥ purūcīr īyur gīrbhir yatamānā amṛdhrāḥ | RV_3,058.08a||]

Bhaskararaya, then concludes that in the context of the Navarna mantra, vicce signifies ‘liberation’; and, could be taken as a synonym for the Sanskrit term mochayati – ‘to cause to be liberated’. And, when the term vicce, in the Navarna mantra, is combined with Goddess Chamunda (Chamunda-visheshanam), it gives forth the meaning that Chamunda is, indeed, the resplendent Goddess who ‘causes her devotee to be liberated.

He says that through the Navarna Mantra we invoke the Supreme Goddess and her varied powers; and, pray to her to come into our lives to fulfil our material and spiritual desires with ease (Sri Sundari sevana tatparanam / Bhogascha mokshascha karastaeva).

Thus, for Bhaskararaya, the Navarna is not only a powerful mantra that protects the devotee; but, is also a means to attain liberation (moksha-sadhana).

The learned scholar Caleb Simmons, in his article, observes:

Bhaskararaya, in the Guptavati, provides a remarkable explanation of the mantra, ritual value of sounds and syllables, and etymology that elucidates our understanding of the relationship between mantra and meaning in which the secret and semantic are coterminous

According to Bhaskararaya, to understand meaning in mantra we must expand our understanding of ‘meaning’ as a category to include not only normative, semantic, and discursive meaning, but to include the hidden meaning of a mantra that contains a truth only perceivable through the direct insight of the initiated practitioner….

Through his introduction to the Guptavati, Bhaskararaya incorporates the Sri Vidya perspective of corresponding realities into a theory of meaning and mantra in which discursive (rational) meaning and the hidden meaning are simultaneously individual but ultimately the same.

Salutation to you, O Devi Nārāyaṇī, who abides as intelligence in the hearts of all beings; and, who grants happiness and liberation, with what words, however excellent, can I praise you?

sarvasya buddhi rūpeṇa janasya hṛdi saṃsthite । svargāpavargade devi nārāyaṇi namo’stu te ॥ 11.8॥

sarvabhūtā yadā devī bhuktimukti pradāyinī । tvaṃ stutā stutaye kā vā bhavantu paramoktayaḥ ॥ 11.7॥

Please listen to the Mantra – Om Hrim Parashakthai Namaha -chanted by Smt. Padma

Sources and References

http://www.advaitaashrama.org/Content/pb/2016/012016.pdf

http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/69521/13/13_chapter%205.pdf

http://yigalbronner.huji.ac.il/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/South-Meets-North.pdf

http://www.vedicastrologer.org/mantras/chandi/chandi_inner_meaning.pdf

https://www.kamakotimandali.com/srividya/bhaskara.html

http://studerende.au.dk/fileadmin/_migrated/content_uploads/Fri_Opgave.pdf

http://navratri.sahajayogaonline.com/images/devi-atharvashirsha.pdf

http://www.aghori.it/devi_atharvashirsha_eng.htm

http://www.kamakotimandali.com/blog/index.php?s=guptavati&advm=&advy=&cat=

http://www.aghori.it/devi_atharvashirsha_eng.htm

https://archive.org/details/DurgaSaptashati_20180206/page/n185

The secret of the three cities by Douglas R Brooks

ALL PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET

Bhāskararāya was a firm believer in the doctrine of Advaita (Advaita siddantha); and, was also proficient in all branches of learning. But, his religious philosophy was based in the Ratna-traya-prakshika of Sri Appayya Dikshita (1520–1593), which upheld the Shiva-Shakthi combine as the Absolute. Bhāskararāya, however, was essentially a Shakta following the Kaula-sampradaya. And yet, he frequently quoted from the works of Sri Sankara; and, revered him as the very incarnation of Sri Dakshinamurti, the Universal Teacher.

Bhāskararāya was a firm believer in the doctrine of Advaita (Advaita siddantha); and, was also proficient in all branches of learning. But, his religious philosophy was based in the Ratna-traya-prakshika of Sri Appayya Dikshita (1520–1593), which upheld the Shiva-Shakthi combine as the Absolute. Bhāskararāya, however, was essentially a Shakta following the Kaula-sampradaya. And yet, he frequently quoted from the works of Sri Sankara; and, revered him as the very incarnation of Sri Dakshinamurti, the Universal Teacher.