[I could not arrange the topics in a sequential order (krama). You may take these as random collection of discussions; and, read it for whatever it is worth. Thank you.]

Kavyasya Atma – the Soul of Poetry

Another line of speculation that is unique to Indian Poetics is to muse about the soul (Atman) of Poetry. Every literary endeavour was regarded a relentless quest to grasp or realize the enigmatic essence that inhabits the Kavya body.

As Prof Vinayak Krishna Gokak explains in his An Integral View of Poetry: an India Perspective: Poetry in its manifestation resembles the series of descending arches in a cave. It is dim lit, leaving behind the garish light of the day, as we walk into it. And as we begin to feel our way, we detect another passage, leading to yet another. But, we do know that there is light at the other end. And, when we have passed through the archways, we stand face-to-face with the ultimate mystery itself. This seems to the inner core, the essence and the fulfillment of poetry. It is the Darshana, perception, of Reality

Then he goes on to say: When we say the poet is inspired, we mean that he had a glimpse of Reality, its luminous perception. It is this perception that elevated him into a state of creative excitement. … Such vision is the intuitive perception. It reveals the many-splendored reality that is clouded by the apparent. It is the integral experience in which the intuitive and instinctive responses are in harmony.

But, this intuitive perception in poetry is rarely experienced in its pristine purity. It is colored, to an extent, by the attitudes, the experiences and the expressions of the poet. The attitude seeps into the structure of words, phrases, rhythms that give form to poetry. The attitude forms the general framework of the poetic experience.

The soul of the Kavya is truly the poet’s vision (Darshana) without which its other constituents cannot come together.

Thus, the inquiry into the appeal of the Poetry was meant to suggest a sort of a probe delving deep into the depths of Kavya to seize its essence. It was an exploration to reach into the innermost core of the Kavya. The term used to denote that core or the fundamental element or the principle which defines the very essence of Kavya was Atma, the soul.

In the context of Kavya, the concept of Atma, inspired by Indian Philosophy, was adopted to characterize it as the in-dweller (Antaryamin), its life-breath (Prana), its life (Jivita) , consciousness (Chetana) ; and to differentiate it from the exterior or the body (Sarira) formed out of the words. That is to say; while structure provided by the words is the physical aspect of Kavya, at its heart is the aesthetic sensitivity that is very subtle and indeterminate.

In the Indian Poetics, the term Atma stands for that most elusive factor which is the highly essential, extensive factor illumining the internal beauty of Kavya. Though one can talk about it endlessly, one cannot precisely define it. One could even say, it is like a child trying to clasp the moonbeams with its little palms. It is akin to consciousness that energizes all living beings (Chaitanya-atma). Its presence can be felt and experienced; but one cannot see its form; and, one cannot also define it in technical terms

^*^*^

In the Kavya-shastra, generally, two types of texts are recognized: Lakhshya grantha and Lakshana grantha.

The texts that describe the characteristics of good poetry and define the technical terms of Kavvya shastra are the Lakshana granthas. These outline and define the concepts ;and, illustrate them with the aid of citations from recognized and time-honored works of poetry or drama, composed by poets of great repute. Sometimes, the author of a Lakshana grantha would himself compose illustrative model pieces, as examples.

Lakshya Grantha is a creative work of art , the Kavya , in the form of a poem or a drama , generally, following the prescriptions of the Lashana granthas.

Various thinkers and writers of the Lakshana granthas, over a long period, have put forward several theories based on their concept of the essential core , the heart or the soul of the Kavya (kavyasya Atma). While the authors like Bhamaha, Dandin, Udbhata and Rudrata focused on Alamkara; Vamana emphasized the concept of Riti. However, it was Anandavardhana who changed the entire course of discussion by introducing the concept of Dhvani. But, , Dhananjaya the author of Dasharupaka and its commentator Dhanika , as also Mahimabhatta the author of Vyaktiviveka , firmly opposed the concept of Dhvani.

Let’s see some of these in a summary form before we get into a discussion:

| Author | Lakshana Grantha | Atma |

| Bharata | Natyashastra | Rasa |

| Bhamaha | Kaavya-alamkara | Alamkara |

| Dhandi | Kaavya-adarsha | Dasha (ten ) Gunas |

| Vamana | Kaavya-alankara-sutra | Reeti |

| Anandavardhana | Dhvanya-loka | Dhvani |

| Kshemendra | Auchitya-vicharachara | Auchitya |

| Mammata | Kavya-prakasha | Dhvani |

| Kuntaka | Vakrokti Jivitam | Vakrokti |

Traditionally, the Kavya was defined by Bhamaha as Sabda-Artha sahitau Kavyam (KA.1.15) – the combination or a complex of words and their meanings. His explanation also implied that word and sense in a Kavya must be free from blemishes (nirdosa) . Bhamaha then extended his explanation to bring in the element of Alamkara; and, said: Kavya is the happy fusion of Sabda and Artha which expresses Alamkaras relating to them

– Sabda-abhideya-alamkara-bhedadhistam dvayam tu nah I Sabda-Artha sahitau Kavyam (KA.1.15).

Dandin also said the body of Kavya is a group of sounds which indicates the desired effect or the desired import of the poet

– Sariram tavad ista-artha vyvachinna padavali (KA 1.10b).

But, the later Schools pointed out that Bhamaha and Dandin seemed to be talking about the body of Kavya, but not about the Kavya itself. And, their definition of Kavya is centred on the external element or the body of Kavya; but, it misses the spirit or the soul of the Kavya. The basic idea of the critics, here, was that Kavya is much more than a collection of words; it is about the vision of the poet and the aesthetic delight it presents to the reader.

It was argued that if the structure of words (Pada-rachana or Padavali) could be taken as the body (Sarira) of the Kavya, then it is separate or different from its soul (Atma) which is its inner–being. Further, Padavali – the group of words – by itself and not accompanied by sense is not of great merit.

Thus, a clear distinction was sought to be made between the body of the Kavya and the spirit or the soul which resides within it. And from here, began a quest for the soul of Kavya (Kavyasya Atma).

As regards the meaning (Artha) conveyed by words in the Poetry, it was also examined in terms of its external and internal forms. It was said :

the language and its structural form lead us to meaning in its dual forms. Thought in poetry manifests itself in two ways: as the outer and the inner meaning. The Outer meaning dominates poetry through its narration. Yet, it permits inner meaning to come into its own seeping through its narrative patterns or poetic excellence. The Outer meaning plays a somewhat semi transparent role in poetry. It achieves its fulfillment when it becomes fully transparent revealing what lies beneath it.

The inner meaning of poetry is embodied in it’s suggestive, figurative or expressions evoking Visions. It reveals the moods, the attitudes and the vision of the poet expressed with the aid of imagery and rhythm. “Such vision is the intuitive perception. It reveals the many-splendored reality that is clouded by the apparent”.

^*^*^

It was perhaps Vamana the author of Kavyalankara-sutra-vritti who initiated the speculation about the Atman or the soul of poetry. He declared – Ritir Atma kavyasya – // VKal_1,2.6 // (Riti is the soul of Poetry). Vamana’s pithy epithet soon became trendy ; and, ignited the imagination of the champions of other Schools of poetics. Each one re-coined Vamana’s phrase by inserting into it (in place of Riti) that Kavya-guna (poetic virtue) which in his view was the fundamental virtue or the soul of poetry.

For instance; Anandavardhana idealized Dhvani as the Atma of Kavya; Visvanatha said Rasa is the Atma of Kavya; while Kuntaka asserted that Vakrokti as the Jivita – the life of Kavya. Besides, Rajasekhara (9th century) who visualized literature, as a whole, in a symbolic human form (Kavya Purusha) treated Rasa as its soul (Atma).

**

Although Vamana was the first to use the term Atma explicitly, the notions of the spirit or the inner-being of Kavya were mentioned by the earlier scholars too, though rather vaguely. They generally talked in terms Prana (life-breath) or Chetana (consciousness) and such other vital factors in the absence of which the body ceases to function or ceases to live. But, such concepts were not crystallized.

[Nevertheless, those epithets, somehow, seemed to suggest something that is essential, but not quite inevitable.]

For instance; Dandin had earlier used the term Prana (life-breath) of the body of poetry which he said was the Padavali (string of words or phrases) – Sariram tavad istartha vyavachhina padavali (KA-1.10). He also used Prana in the sense of vital force or vital factor (say for instance: iti vadarbhi –margasya pranah).

Udbhata who generally followed Dandin, in his Alamkara-samgraha, a synopsis of Alamkara, stated that Rasa was the essence or the soul of Kavya.

While Dandin and his followers focused on Sabda Alamkara, Vamana (Ca.8th century) raised questions about the true nature of Kavya; and said Ritiratma Kavyasya – the soul of the poetry abides in its style – excellence of diction.

Anandavardhana said: all good poetry has two modes of expression – one that is expressed by words embellished by Alamkara; and the other that is implied or concealed – what is inferred by the listener or the reader. And , this implied one or the suggested sense, designated as Dhvani (resonance or tone or suggestion) , is indeed the soul of Kavya: Kavyasya Atma Dhvanih.

A little later than Anandavardhana, Kuntaka (early tenth century) said that indirect or deflected speech (Vakrokti) – figurative speech depending upon wit, turns , twists and word-play is the soul of Kavya. He said that such poetry showcases the inventive genius of the poet at work (Kavi-karman).

[The complex web of words (Sabda) and meanings (Artha) capable of being transformed into aesthetic experience (Rasa) is said to have certain characteristic features. These are said to be Gunas and Alamkara-s. These – words and meanings; Alamkara; Gunas; and, Rasa – though seem separable are, in fact , fused into the structure of the poetry. The Poetics, thus, accounts for the nature of these features and their inter-relations

All theories, one way or the other, are interrelated; and, illumine each other. The various aspects of Kavya starting from making of poetry (kavya-kriya-dharma) up to the critique of poetry (kavya-mimamsa) and how human mind perceives and reacts to it, was the main concern for each theory. ]

^*^*^

Alamkara

Alamkara denotes an extraordinary turn given to an ordinary expression; which makes ordinary speech into poetic speech (Sabartha sahitya) ; and , which indicates the entire range of rhetorical ornaments as a means of poetic expression. In other words, Alamkara connotes the underlying principle of embellishment itself as also the means for embellishment.

According to Bhamaha, Dandin and Udbhata the essential element of Kavya was in Alamkara. The Alamkara School did not say explicitly that Alamkara is the soul of Poetry. Yet, they regarded Alamkara as the very important element of Kavya. They said just as the ornaments enhance the charm of a beautiful woman so do the Alamkaras to Kavya: shobha-karan dharman alamkaran prakshate (KA -2.1). The Alamkara School, in general, regarded all those elements that contribute towards or that enhance the beauty and brilliance of Kavya as Alamkaras. Accordingly, the merits of Guna, Rasa, and Dhvani as also the various figures of speech were all clubbed under the general principle of Alamkara.

Though Vamana advocates Riti, he also states that Alamkara (Soundarya-alamkara) enhances the beauty of Kavya. Vamana said Kavya is the union of sound and sense which is free from poetic flaws (Dosha) and is adorned with Gunas (excellence) and Alamkaras (ornamentation or figures of speech).

According to Mammata, Alamkara though is a very important aspect of Kavya , is not absolutely essential. He said; Kavya is that which is constructed by word and sentence which are (a) faultless (A-doshau) (b) possessed of excellence (Sugunau) , and, (c) in which rarely a distinct figure of speech (Alamkriti) may be absent.

Riti

Vamana called the first section (Adhikarana) of his work as Sarira-adhikaranam – reflexions on the body of Kavya. After discussing the components of the Kavya-body, Vamana looks into those aspects that cannot be reduced to physical elements. For Vamana, that formless, indeterminate essence of Kavya is Riti.

Then, Vamana said; the essence of Kavya is Riti (Ritir Atma Kavyasya – VKal_1,2.6 ); just as every body has Atma, so does every Kavya has its Riti. And, Riti is the very mode or the act of being Kavya. Thus for Vamana, while Riti is the essence of Kavya, the Gunas are the essential elements of the Riti. The explanation offered by Vamana meant that the verbal structure having certain Gunas is the body of Kavya, while its essence (soul) is, Riti.

Riti represents for Vamana the particular structure of sounds (Vishista-pada-rachana Ritihi) combined with poetic excellence (Vishesho Gunatma) . According to Vamana, Riti is the going or the flowing together of the elements of a poem

– Rinati gacchati asyam guna iti riyate ksaraty asyam vanmaddhu-dhareti va ritih (Vamana KSS).

The language and its structural form lead us to the inner core of poetry. And, when that language becomes style (Riti), it absorbs into itself all the other constituent elements of poetry. It allows them, as also the poetic vision, to shine through it.

Vamana, therefore, accorded Riti a very high position by designating Riti as the Soul of Kavya – rītirnāmeyam ātmā kāvyasya / śarīrasyeveti vākyaśeṣaḥ (I.2.6) – Riti is to the Kavya what Atman is to the Sarira (body). Here, it is explained that in his definition of Riti, Pada-rachana represents the structure or the body while Riti is its inner essence. Through this medium of Visista Pada-rachana (viśiṣṭā padaracanā rītiḥ viśeṣo guṇātmā – 1,2.7) the Gunas become manifest and reveal the presence of Riti, the Atman.

Auchitya

Kshemendra – wrote a critical work Auchitya-alamkara or Auchitya-vichara-charcha (discussions or the critical research on proprieties in poetry), and a practical handbook for poets Kavi-katnta-abharana (ornamental necklace for poets) – calls Auchitya the appropriateness or that which makes right sense in the given context as the very life-breath of Rasa – Rasajivi-bhootasya.

He said Auchitya is the very life of Kavya (Kavyasya jivitam) that is endowed with Rasa (Aucityam rasa siddhasya sthiram kavyasya jivitam).

Abhinavagupta avers that the life principle (jivitatvam) of Kavya could said to be the harmony that exists among the three : Rasa, Dhvani and Auchitya – Uchita-sabdena Rasa-vishaya-auchityam bhavatithi darshayan Rasa-Dhvane jivitatvam suchayati. Thus, Auchitya is entwined with Rasa and Dhvani.

He asserts that Auchitya implies , presupposes and stands for ‘suggestion of Rasa’ – Rasa-dhvani – the principles of Rasa and Dhvani.

The most essential element of Rasa , he said, is Auchitya. The test of Auchitya is the harmony between the expressed sounds and the suggested Rasa. And , he described Auchitya as that laudable virtue (Guna) which embalms the poetry with delight (aucityaṃ stutyānāṃ guṇa rāgaś ca andanādi lepānām – 10.31)

According to Kshemendra, all components of Kavya perform their function ideally only when they are applied appropriately and treated properly. “When one thing befits another or matches perfectly, it is said to be appropriate, Auchitya”:

(Aucityam prahuracarya sadrasham kila; Aucitasya ka vo bhava stadaucityam pracaksate).

The concept of Auchitya could , perhaps, be understood as the sense of proportion between the whole (Angin) and the part (Anga) and harmony on one side; and, appropriateness and adaptation on the other.

It said; be it Alamkara or Guna, it will be beautiful and relishing if it is appropriate (Uchita) from the point of view of Rasa; and, they would be rejected if they are in- appropriate . And, what is normally considered a Dosha (flaw) might well turn into Guna (virtue) when it is appropriate to the Rasa

But, many are hesitant to accept Auchitya as the Atma of the Kavya. They point out that Auchitya by its very nature is something that attempts to bring refinement into to text; but, it is not an independent factor. And, it does not also form the essence of Kavya. Auchitya is also not a recognized School of Poetics.

[Please click here for a detailed discussion on Auchitya. Please also read the research paper : ‘A critical survey of the poetic concept Aucitya in theory and practice’ produced by Dr. Mahesh M Adkoli

Please also read Dr.V. Raghavan’s article: The History of Auchitya in Sanskrit Literature ]

Vakrokti

Kuntaka defined Kavya on the basis of Vakrokti, a concept which he developed over the idea earlier mentioned by Bhamaha and others. According to him, Kavya is the union of sound, sense and arranged in a composition which consists Vakrokti (oblique expressions of the poet), delighting its sensible reader or listener –

(Sabda-Artha sahitau vakra Kavi vakya vyapara shalini I bandhe vyavasthitau Kavya tat ahlada karini: VJ 1.7).

Kuntaka also said that the word and sense, blended like two friends, pleasing each other, make Kavya delightful –

Sama-sarva gunau santau sahhrudaveva sangathi I parasparasya shobhayai sabdartau bhavato thatha II 1.18.II

Kuntaka, declared Vakrokti as jivitam or soul of poetry. By Vakrokti, he meant the artistic turn of speech (vaidagdhyam bhangi) or the deviated from or distinct from the common mode of speech.

abhāvetāv alaṅkāryau tayoḥ punar alaṅkṛtiḥ / vakroktir eva vaidagdhya bhaṅgī bhaṇitir ucyate – Vjiv_1.10

Vakratva is primarily used in the sense of poetic beauty. It is striking, and is marked by the peculiar turn imparted by the creative imagination of the poet. It stands for charming, attractive and suggestive utterances that characterize poetry. The notion of Vakrata (deviation) covers both the word (Sabda) and meaning (Artha). The ways of Vakrokti are, indeed, countless.

Vakrokti is the index of a poet’s virtuosity–kavi kaushala. Kuntaka describes the creativity of a poet as Vakra-kavi–vyapara or Kavi–vyapara–vakratva (art in the poetic process). This according to Kuntaka , is the primary source of poetry; and, has the potential to create aesthetic elegance that brings joy to the cultured reader with refined taste (Sahrudaya).

According to Kuntaka, Vakrokti is the essence of poetic speech (Kavyokti); the very life (Jivita) of poetry; the title of his work itself indicates this.

Rasa

Rasa (the poetic delight) though it is generally regarded as the object of Kavya providing joy to the reader rather than as the means or an element of Kavya , is treated by some as the very essence of Kavya.

Yet; Indian Aesthetics considers that among the various poetic theories (Kavya-agama), Rasa is of prime importance in Kavya. And, very involved discussions go into ways and processes of producing Rasa, the ultimate aesthetic experience that delights the Sahrudya, the connoisseurs of Kavya.

The Rasa was described as the state that arises out of the emotion evoked by a poem through suggestive means, through the depiction of appropriate characters and situations and through rhetorical devices. The production of Rasa or aesthetic delight was therefore regarded the highest mark of poetry. It was said – The life breath (Prana) of Kavya is Rasa.

Further, Poetry itself came to be understood as an extraordinary kind of delightful experience called Rasa. It was exclaimed: Again, what is poetry if it does not produce Rasa or give the reader an experience of aesthetic delight?

Rasa is thus regarded as the cardinal principle of Indian aesthetics. The theory of Rasa (Rasa Siddhanta) and its importance is discussed in almost all the works on Alamkara Shastra in one way or the other. The importance of the Rasa is highlighted by calling it the Atman (the soul), Angin (the principle element), Pradhana-Pratipadya (main substance to be conveyed), Svarupadhyaka (that which makes a Kavya), and Alamkara (ornamentation) etc.

Mammata carrying forward the argument that Rasa is the principle substance and the object of poetry, stated ‘vakyatha rasatmakarth kavyam’, establishing the correlation between Rasa and poetry.

Vishwanatha defined Kavya as Vakyam rasathmakam Kavyam – Kavya is sentences whose essence is Rasa.

Jagannatha Pandita defined Kavya as: Ramaniya-artha prathipadakah sabdam kavyam ; poetry is the combination of words that provides delight (Rasa) . Here, Ramaniyata denotes not only poetic delight Rasa, pertaining to the main variety of Dhvani-kavya, but also to all the ingredients of Kavya like Vastu-Dhvani Kavya; Alamkara-Dhvani –Kavya, Guni-bhutha –vyangmaya-kavya; Riti; Guna, Alamkara, Vakrokti etc.

**

[While talking about Rasa, we may take a look at the discussions on Bhakthi Rasa.

Natyashastra mentions four main Rasas and their four derivatives, thus in all eight Rasas (not nine). These Rasas were basically related to dramatic performance; and Bhakthi was not one of those. Thereafter, Udbhata (9th century) introduced Shantha Rasa. After prolonged debates spread over several texts across two centuries Shantha was accepted as an addition to the original eight.

But, it was Abhinavagupta (11th century) who established Shantha as the Sthayi-bhava the basic and the abiding or the enduring Bhava form which all Rasas emerge and into which they all recede. His stand was: one cannot be perpetually angry or ferocious or sad or exited or erotic, at all the time. These eight other Rasas are the passing waves of emotions, the colors of life. But, Shantha, tranquility, is the essential nature of man; and it is its disturbance or its variations that give rise to shades of other emotions. And, when each of that passes over, it again subsides in the Shantha that ever prevails.

During the times of by Abhinavagupta and Dhanajaya, Bhakthi and Priti were referred to as Bhavas (dispositions or attitudes); but, not as Rasas. Even the later scholars like Dandin, Bhanudatta and Jagannatha Pandita continued to treat Bhakthi as a Bhava.

[Later, each system of Philosophy or of Poetics (Kavya-shastra) applied its own norms to interpret the Rasa-doctrine (Rasa Siddantha) ; and in due course several Rasa theories came up. Many other sentiments, such as Sneha, Vatsalya; or states of mind (say even Karpanya – wretchedness) were reckoned as Rasa. With that, Rasas were as many as you one could identify or craft (not just nine).]

It was however the Gaudiya School of Vaishnavas that treated Bhakthi as a Rasa. Rupa Goswami in his Bhakthi-Rasa-amrita–Sindhu; and the Advatin Madhusudana Sarasvathi in his Bhagavad-Bhakthi Rasayana asserted that Bhakthi is indeed the very fundamental Rasa. Just as Abhinavagupta treated Shantha as the Sthayi Bhava, the Vaishnava Scholars treated Bhakthi as the Sthayi, the most important , enduring or the abiding Bhava that gives rise to Bhakthi Rasa.

Their texts described twelve forms of Bhakthi Rasas – nine of the original and three new ones. Instead of calling each Rasa by its original name, they inserted Bhakthi element into each, such as: Shantha-Bhakthi-Rasa, Vira-Bhakthi-Rasa, Karuna-Bhakthi-Rasa and so on. They tried to establish that Bhakthi was not one among the many Rasas; but, it was the fundamental Rasa, the other Rasa being only the varied forms of it. The devotee may assume any attitude of devotion like a child, mother, master, Guru or even an intimate fiend. It was said “Bhakthi encompasses all the Nava-rasas”.

Bhakthi, they said, is the Sthayi (abiding) Bhava; and it is the original form of Parama-Prema (highest form of Love) as described in Narada Bhakthi Sutra. What constitutes this Love is its essence of Maduhrya (sweetness) and Ujjvalata (radiance).

Although, an element of individualized love is involved in Bhakthi, it is not confined to worship of a chosen deity (ista Devatha). The Vedanta Schools treat Bhakthi as a companion of Jnana in pursuit of the Brahman. They hold that Bhakthi guides both the Nirguna and the Saguna traditions. Just as Ananda is the ultimate bliss transcending the subject-object limitation, Bhakthi in its pristine form is free from the limitations of ‘ego centric predicament’ of mind. And, both are not to be treated as mere Rasas.

Bhakthi is that total pure unconditional love, accepting everything in absolute faith (Prapatthi).

Now, all Schools generally agree that Bhakthi should not be confined to theistic pursuits alone; as it pervades and motivates all aspects human persuasions including studies, arts and literature. In the field of art, it would be better if the plethora of Rasa-theories is set aside; because, the purpose of Art, the practice of Bhakthi and the goal of Moksha are intertwined.

Therefore, it is said, it is not appropriate (an-auchitya) to narrow down Bhakthi to a mere Rasa which is only a partial aspect. Bhakthi is much larger; and it is prime mover of all meaningful pursuits in life.]

Dhvani and Rasa-Dhvani

With the rise of the Dhvani School, the elements of Rasa and Dhvani gained prominence; and, superseded the earlier notions of poetry. And, all poetry was defined and classified in terms of these two elements.

Anandavardhana said: all good poetry has two modes of expression – one that is expressed by words embellished by Alamkara; and the other, that is implied or concealed – what is inferred by the listener or the reader.

The suggested or the implied sense of the word designated as Dhvani (resonance or tone or suggestion) through its suggestive power brings forth proper Rasa. Abhinavagupta qualified it by saying: Dhvani is not any and every sort of suggestion, but only that sort which yields Rasa or the characteristic aesthetics delight.

For Anandavardhana, Dhvani (lit. The sounding-resonance) is the enigmatic alterity (otherness) of the Kavya-body- Sarirasye va Atma ….Kavyatmeti vyavasthitah (as the body has Atma, so does Dhvani resides as Atma in the Kavya)

yo ‘rthaḥ sahṛdaya-ślāghyaḥ kāvyātmeti vyavasthitaḥ / vācya-pratīyamānākhyau tasya bhedāv ubhau smṛtau –DhvK. 1.2

Anandavardhana regarded Dhvani – the suggestive power of the Kavya, as its highest virtue. The Alamkara, figurative ornamental language, according to him, came next. In both these types of Kavya-agama, there is a close association between the word and its sound, and between speech (vak) and meaning (artha). The word is that which , when articulated, gives out meaning; and,the meaning is what a word gives us to understand. Therefore, in these two types of Kavya there is a unity or composition (sahitya) of word (sabda-lankara) and its meaning (artha-lankara).

Anandavardhana‘s definition of Kavya involves two statements: Sabda-Artha sariram tavath vakyam; and, Dhvanir Atma Kavyasa – the body of poetry is the combination of words and sounds; and; Dhavni, the suggestive power is the soul of the poetry. Here, Anandavardhana talks about poetry in terms of the body (Sabda–artha sariram tavath vakyam) and soul of the Kavya (Dhvanir atma Kavyasa). And he also refers to the internal beauty of a meaningful construction of words in the Kavya. And, he declares Dhvani as the Atma, the soul of poetry.

kāvyasyātmā dhvanir iti budhair yaḥ samāmnāta-pūrvas tasyābhāvaṃ jagadur apare bhāktam āhus tam anye / kecid vācām sthitam aviṣaye tattvam ūcus tadīyaṃ tena brūmaḥ sahṛdaya-manaḥ-prītaye tat-svarūpam // DhvK_1.1 //

The Dhvani theory introduced a new wave of thought into the Indian Poetics. According to this school, the Kavya that suggests Rasa is excellent. In Kavya, it said, neither Alamkara nor Rasa , but Dhvani which suggest Rasa, the poetic sentiment, is the essence, the soul (Kavyasya-atma sa eva arthaa Dhv.1.5). He cites the instance of the of the sorrow (Soka) separation (viyoga) of two birds (krauñca-dvandva) that gave rise to poetry (Sloka) of great eminence.

kāvyasyātmā sa evārthas tathā cādikaveḥ purā / krauñca-dvandva-viyogotthaḥ śokaḥ ślokatvam āgataḥ – DhvK_1.5

Anandavardhana maintained that experience of Rasa comes through the unravelling of the suggested sense (Dhvani). It is through Dhvani that Rasa arises (Rasa-dhavani). The experience of the poetic beauty (Rasa) though elusive, by which the reader is delighted, comes through the understanding heart.

Then, Anandavardhana expanded on the object (phala) of poetry and on the means of its achievement (vyapara). The Rasa which is the object of poetry, he said, is not made; but, it is revealed. And, that is why words and meanings must be transformed to suggestions of Rasa (Rasa Dhvani).

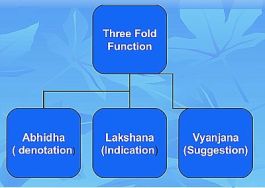

The Rasa Dhvani, the most important type of Dhvani, consists in suggesting Bhava, the feelings or sentiments. In Rasa Dhvani, emotion is conveyed through Vyanjaka, suggestion. Rasa is the subject of Vyanjaka, as differentiated from Abhidha and Lakshana.

Anandavardhana, in some instances, considers Rasa as the Angi (soul) of poetry. Its Anga-s (elements) such as Alamkara, Guna and Riti seem to be dependent on this Angi.

Thus, the principle of Rasa Dhvani is the most significant aspect of the Kavya dharma, understanding Kavya. And, the Rasa experience derived from its inner essence is the ultimate aim of Kavya. Hence, the epithet Kavyasya Atma Dhvani resonates with Kavyasya Atma Rasah.

Anandavardhana regarded Rasa-Dhvani as the principal or the ideal concept in appreciation of poetry. He said that such suggested sense is not apprehended (na vidyate) by mere knowledge of Grammar (Sabda-artha-shasana-jnana) and dictionary. It is apprehended only (Vidyate, kevalam) by those who know how to recognize the essence of poetic meaning (Kavya-artha-tattva-jnana) – Dhv.1.7

śabdārtha-śāsana-jñāna-mātreṇaiva na vedyate / vedyate sa tu kāvyārtha-tattvajñair eva kevalam – Dhv.1.7

The confusion and chaos that prevailed in the literary circles at that time prompted Mammata to write Kavyaprakasa , to defend and to establish the Dhvani theory on a firm footing ; and, also to refute the arguments of its opponents.

Abhinavagupta accepted Rasa-Dhvani ; and expanded on the concept by adding an explanation to it. He said, the pratīyamānā or implied sense which is two-fold: one is Laukika or the one that we use in ordinary life; and the other is Kavya vyapara gocara or one which is used only in poetry – pratipādyasya ca viṣayasya liṅgitve tad-viṣayāṇāṃ vipratipattīnāṃ laukikair eva kriyamāṇānām abhāvaḥ prasajyeteti.

He also termed the latter type of Rasa-Dhvani as Aloukika, the out-of–the world experience. It is an experience that is shared by the poet and the reader (Sahrudaya). In that, the reader, somehow, touches the very core of his being. And, that Aloukika is subjective ultimate aesthetic experience (ananda); and, it is not a logical construct. As Abhinavagupta says, it is a wondrous flower; and, its mystery cannot really be unraveled.

As regards the Drama , Abhinavagupta and Dhananjaya both agree that Rasa is always pleasurable (Ananadatmaka); and Bhattanayaka compares such Rasa – Anubhava (experience of Rasa) to Brahma-svada, the relish of the sublime Brahman.

[However, the scholars , Ramachandra and Gunachandra , the authors of Natya Darpana (12th century), sharply disagreed and argued against such ‘impractical’ suppositions. They pointed out that Rasa, in a drama, is after-all Laukika (worldly, day-to-day experience); it is a mixture of pain and pleasure (sukha-dukka-atmaka); and , it is NOT always pleasurable (Ananadatmaka) . They argued, such every-day experience cannot in any manner be Chamatkara or A-laukika (out of the world) ecstasy comparable to Brahmananda etc., But, their views did not find favor with the scholars of the Alamkara School ; and, it was eventually, overshadowed by the writings of the stalwarts like Abhinavagupta, Anandavardhana, Mammata, Hemachandra , Visvanatha and Jagannatha Pandita.]

In any case, one can hardly disagree with Abhinavagupta. The concept of Kavyasya-Atma, the soul of Poetry is indeed a sublime concept; and, one can take delight is exploring layers and layers of its variations. Yet, it seems, one can, at best, only become aware of its presence, amorphously; but, not pin point it. Kavyasya-Atma, is perhaps best enjoyed when it is left undefined.

Happiness is such a fragile thing!! Very thought of it disturbs it.

Continued

in the

Next Part

Sources and References

An Integral View of Poetry: an India Perspective by Prof Vinayak Krishna Gokak

Glimpses of Indian Poetics by Dr. Satya Deva Caudharī