lowContinued from Part Seven – Music in Natyashastra

Part Eight (of 22) – Dhruva Gana in Natya

Dhruva Gana

1.1. Drama in the ancient context was said to be a blend of four components: speech; gesture; song (or music); and emotion. Each of these was believed to correspond with a Veda: the spoken word or speech the vehicle of elemental power with Rig-Veda; acting, gestures and expressions with ritual action of Yajur Veda; songs rooted in tradition with the musical style of rendering the Sama Veda verses; and emotional elements communicated to spectators through the combination of all such means with Atharva Veda.

1.2. A play was described as a Poem (Kavya) that is to be seen and heard (Drshya-Kavya). Song and Music, therefore, did play a vital role in the enactment of a play. The songs in the play were of Dhruva Gana class.

2.1. Dhruva Gana initially meant versified stage-songs that are essential to a play. They were the type of songs that were sung by the actors on the stage as also by the singers in the wings, to the accompaniment of musical instruments, during the course of the play. These songs formed an essential ingredient of the play.

And, Natyashastra says: without songs the Drama is incapable of providing joy (NS. 32. 482). It says : Just as a well-built dwelling house (citraṃ niveśanaṃ) does not become beautiful and provide a pleasant ambiance without any colour; so also a Drama without any songs does not provide much joy.

Again , the importance of songs in dramatic performances is highlighted by stating that, just as a picture without color does not produce any beauty, a play without songs cannot become delightful.

yathà varnàd rahite citram na shobhotpàdanam bhavet| evam eva vinà gànam nàtyam ràgam na gacchati|| NS. 32. 425|

Therefore, much importance is assigned to Dhruva Gana. Natyashastra devotes one entire and a lengthy chapter (Chapter 32) for discussing the Dhruva songs.

2.2. Abhinavagupta explains that the type of these songs were called Dhruva ( = standpoint; locus of reference) because in it, the Vakya (sentence), Varna (syllables) , Alamkara (grace notes), Yatis (succession of rhythm patterns) , Panyah (use or non-use of drums) and Laya (beats) were harmoniously fixed ( Dhruva) in relation to each other – (anyonya sambandha) .

Vakya –Varna–Alamkara yatyaha -panayo-layah I Dhruvam-anyonya sambandha yasmath smada Dhruva smrutah II

He further says, the composition (pada samuha) structured as per a rule (niyatah) and that which supports (adhara) singing could be called Dhruva (Dhruvah- Gitya-adhara niyatah pada –samuha).

At another place, Abhinavagupta explains Dhruva as the basis or the support (adhara) on which the song rests. Abhinavagupta says: just as the painting is supported by wall, the Dhruva song is supported by Pada (word). And, Pada in turn is supported by, the Chhandas (meter) – (Abhinavagupta: NS.32.8).

Thus in the Dhruva Gana the words of the song are regulated by Chhandas. And , the words are then set to appropriate tunes and Taala-s.

Abhinavagupta explains that the Dhruva songs help to enhance the artistic sense of the important themes that occur in various situations in a play.

Earlier, Natyashastra (NS: 32.32) had also explained Dhruva Gana as well composed songs that are steadfast (Dhruva) in the principles of Pada (words), Varna (syllables) and Chhandas (meter) .

When to sing and what to sing

3.1. During the play, the Dhruva–Gana songs were sung at various situations in the drama including entry or exit of a character; or for heightening the emotions; or for dance movements or steps. The type and mood of Dhruva songs varied depending upon the demands of the dramatic situation. That would also take into consideration the theme, the context in performance, the age and the nature of the character as also the moods , the seasons , the place , time (day or night) and conditions (bright sun , moonlight , cloudy or raining) and so on.

3.2. Natyashastra says that events and emotions that either cannot be expressed or remain to be expressed in speech should be presented through songs. That is because; the songs have the tender power, flexibility and ripeness to bring out the inner content (aantharya) of the situation succulently. And in songs, the words seem to acquire greater depth of meaning.

For instance; the Avakrsta songs having long drawn out syllables were used in pathos and when the character was in misery or nearing death. Dhruva-s of Sthitha in slow tempo were sung in the case of separation, longing for the beloved, anxiety, exhaustion or dejection. Prasdiki Dhruva-s in medium tempo is for love scenes, recalling a pleasant memory, sweet speech and wonder. And, the Druta type of Dhruva-s having short or rapid notes were employed in situations where there was furious heroism, , wonder, excitement , excessive joy or anger .

3.3. At the same time, the Natyashastra also tried to maintain a sense of balance between speech and song. It therefore said: The first round of Dhruva should be without drums, because it is important for the spectators to get to know the theme of the song. And, too much music should not be used in Dhruva because the substance of the song is important to outline the context of the scene. The words (Pada) of the Dhruva are important and should be heard clearly.

And, when a character enters crying in excitement, in wonder or announcing a statement, then Dhruva songs were not to be used.

Particularly when female actors sing , the music should not be so loud as to hamper the intricacies of singing. Generally women have sweet and soft voice; and , they could be allowed more number of songs with mellow instrumentation. The men who have vigorous voice could use louder and intricate instrumental music.

Five types of Dhruva

4.1. Five types of Dhruva are mentioned in the context of Natya according to the situation and the desired mood to be evoked:

Pravesiki Dhruva;

Naiskramiki Dhruva;

Aksepiki Dhruva;

Prasadiki Dhruva; and

Antara Dhruva.

Some of the Dhruva songs were sung by the musicians behind the curtain. And when it was removed the character would enter and join the singing and gesturing the mood etc indicated by the song. All those songs were played to the accompaniment of the instruments.

Thus, the different types of Dhruva-s indicate the varied functions they perform during the course of the play. They were used to suggest either the entry or the exit of a character or other events. The accompanying instrumental music did , of course, enhance the theatrical effect of the scene; and, made it more enjoyable.

4.2. Pravesiki Dhruva: – these were songs heralding the entrance of a main character on to the stage for the first time. The singing of the Dhruva was generally from behind the screen (Nepathye); and when the screen was removed the character entered on to the stage. And, the actor too would join the singing. This appears to be the forerunner of the Paatra-pravesha Daru of Bhagavata Mela, Yakshagana and Kuravanji Nataka. Rajashekara (Balabharata 1-14) says: the Dhruva that announces and introduces a character, delights the hearts of the spectators; and, helps to forge a relation between the two.

4.3. Naiskramiki Dhruva: – songs rendered during the exit of a character either at end or the middle of an act.

4.4. Aksepiki Dhruva: – songs rendered, between the acts, after a tense scene or to indicate change of mood. The change, sometimes, occurs in the character after listening to Nepathya-vakya – the speech behind the curtain. Along with the change in the mood, a change in tempo also takes place – from slow to quick or the other way. Abhinavagupta illustrates the use of Aksepiki sung in fast tempo (Druta) to indicate the change of mood of Sri Rama from that of sadness (Shoka) to that of heroics (Vira) after listening to Ravana.

4.5. Prasadiki Dhruva: – Prasadiki is described as that which gives rise to colourful delight (ranga-raga) and happiness (Prasada). This type of songs sung in Madhyama Kaala are used to express Srinagar Rasa, as in love-scenes, the first meeting of the lovers, recalling a pleasent memory sweet speech, joy and wonder. It is also meant to clam the spectators after a stressful scene as in Aksepiki.

4.6. Antara Dhruva – is a sort of ‘filler’ that could be used to rescue the performance. It could cover up a gap due to delay or due to a mishap during the play. It could also be sung to offer relief after a disturbing scene such as violence, anger, intense grief swooning, poisoning etc. All such songs were played to the accompaniment of the instruments

Antara was always being sung from behind the curtain, while the other four types being sung on the stage and some of that the leading characters.

It is said; Antara Dhruva songs were sung even to divert audience’s attention. For instance; in the middle of one of his plays, Bharatha introduces a song and dance sequence that apparently had no relevance to the narration of the story. The learned among the audiences are promptly confused. They inquire Bharatha “We can understand about acting which conveys definite meaning. But, this dance and this music you have brought in seem to have no meaning. What use are they?” – na gītakā-artha-sambandhaṃ na cāpy-arthasya bhāvakam ॥ 4.262॥

Bharatha agrees that there is no meaning attached to those dances and songs; and goes on to explain calmly “yes, but it adds to the beauty of the presentation and common people naturally like it. And, as these are happy and auspicious songs people love it more; and they even perform these dances and sing these songs at their homes on marriage and other happy occasions”(Natyashastra : 4.267-268)

[ Such ‘relief’ Antara Dhruva was perhaps the forerunners of the Item-songs of the Bollywood.]

vinodakāraṇaṃ ceti nṛttam etat pravartitam । ataścaiva pratikṣepā adbhūtasaṅghaiḥ pravartitāḥ॥ 266॥

ye gītakādau yujyante samyaṅnṛttavibhāgakāḥ। devena cāpi samproktastaṇḍus tāṇḍava pūrvakam ॥ 267॥

gīta prayogam āśritya nṛttam etat pravartyatām । prāyeṇa tāṇḍava vidhir deva stutyāśrayo bhavet ॥268॥

Chhandas (Meter)

5.1. Bharatha says that just as the Vedic chants, the Dhruva cannot be without Chhandas (meter) _ (NS: 32.432). In the Natyashastra, Chhandas are discussed as an essential part of vācika abhinaya. And, Vac is said to be the soul of this Abhinaya (expressions with gesticulation). Bharatha considers that the words in Dhruva and Chhandas go together; they are mutually dependent.

(Chandohīno na śabdoˊsti na chandaḥ śabdavarjitam, evam tūbhayasa¿yogo nāṭyasyoddyotakaḥ smṛtaḥ ).

5.2. Bharatha combines the discussion on Chhandas with that on dramatic-plot with script (Pathya). The Chhandas, he says, gives a structure to the words of the Dhruva song (Chhandamsi pāṭhya nibaddha).

Bharata mentioned Pathya in the Natyasastra (17. 102); and, said: “pathyam prayunjitam sad-alamkara-samyuktam” – the Sahitya of a song is called the Pathya, when it is embellished by six Alamkaras. Abhinavagupta in his Abhinava- bharati explains that when any composition (sahitya) possesses six Alamkaras and sweet tones, it is known as a Pathya. These six Alamkaras are: Svara, Sthana, Varna, Kaku, Alamkara and Anga. (Note: kakus are the variations of the vocal sound for expressing different ideas)

Bharata considered Pathya under two heads: Sanskrita and Prakrit. Abhinavagupta followed Bharata in this respect

5.3. The Chapter 16 of the Natyashastra discusses the practical aspects of Chhandas in Dhruva Gana and gives about 116 illustrations of Dhruva-s set in various Vedic meters such as: Gayatri, Anustub, Tristub, Brihati, Jagati, Panaki etc

Laya (Tempo)

Laya literally means ‘to be one with’ and binds the emotion of the song with the Tempo. Laya signifies the speed or the Tempo of a song or dance. Chapter 29 of the Natyashastra discusses how the emotional content (Rasa) or the mood of a Dhruva song could be best presented in a certain Laya.

The measurement of time is usually in terms of the time- interval between two events. Time (that is the duration) appears as a chain that links events separated from one another by periods of rest (absence of events) . That is to say the duration between two events which becomes the basic unit of measure is known as Kaala .

The Kaala is measured in terms of the time-units called Matra. And, one Matra is the time taken to utter five short syllables (e.g. Ka-Cha-Ta-Pa). It is, of course, not precise ; because, the time taken to utter five short syllable might vary from person to person. But, it is taken as the approximate time that most, normal, persons would take. Therefore, in the Gandharva Music, Matra is not rigid.

Kaala is the basic unit in terms of which the duration of the Taala is measured (Abhinavagupta: NS: 31.06). A Taala segment is identified as a structure of so many number of Kaala-s. (Thus, Kaala, Matra, Laya and taala are all inter related terms).

The three kinds of units of measure (Kaala) that were employed in the Gandharva Music were: Laghu (short), Guru (long) and Pluta (extended). Laghu is equal to one Matra; Guru to two Matra-s; and Pluta to three Matra-s.

Laya is understood as the time-interval between two Matra-s ( or the pause between two strokes). If the intervals are of short duration then the beats must be fast; and the Tempo would be fast. If the intervals are twice the duration of the fast tempo, the beats become slower; and the Tempo would be middle. And similarly, if the intervals are four times the duration, the beats would get slower ; and the tempo would be slow.

The text speaks of three kinds of Laya: Vilambita (slow); Madhyama (middle); and Dhruta (fast). Vilambita is the basic speed; Madhyama is double the speed of Vilambita Laya; and, Dhruta, the fast, is double the speed of Madhyama Laya.

In Druta Laya, the time lag between two Kaala-s is brief; each following the other in quick succession. Thus, when the Laya is short, the tempo of the Taala would be fast. In Madhya Laya, the tempo would be medium ; and in Vilamba the tempo would be slow. The change from Druta to Madhyama is spoken as ‘doubling of Laya’.

There are also other ways of classifying Laya: Sama, Srotogata and Gopuccha. This is spoken in terms of Yati which is a sort of method to indicate Laya.

In the Sama there is a uniformity of Laya in the beginning, in the middle and in the end. In the Srotagata (like the flow of the river that expands in breadth) Vilambita is used in the beginning, Madhyama in the middle and Druta in the end. The Goputccha (tapering like a cow’s tail) is the reverse order of Srotagata.

Laya is an integral part of music, while Taala is its physical expression through a precise time-cycle. Laya is thus said to be Prana (vital force) of Taala. And the two terms are sometimes used alternatively. Therefore, the Taala-s of Dhruva songs sometimes are referred to as Laya-s or Laya-taala.

Bharatha elaborated on Taala in the 29th chapter of the Natyashastra, as it performed a large role in coordinating different activities of music, drums and dance. The function of the Taala is measuring the rhythm of the song and regulating the flow of the rhythm and the melody in the song.

He explained Taala saying as a definite measure of time upon which Dhruva Gana rests: ganam talena dharyathe. Matra is the smallest unit of the Taala. A Taala does not have a fixed tempo (Laya); and, can be played at different speeds. The Taala-s used in Dhruva songs were simpler – say , like Tryasra and Chturasra. ; and , were regulated by the meter (Chhandas) of the song text (Pathya) (Abhinavagupta :NS: 32.352) .

In the Tryasra Dhruva the steps should follow three Kaalas. And, in Chatusra they should follow four Kaalas (Kaala = Matra that is the time required to utter five short syllables)

Natyashastra recommends songs exuding Karuna Rasa (sorrow) should in Vilamba Laya; Sringara (erotic) in Madhyama Laya; and, Veera (heroics) and Raudra (anger) in Druta Laya.

And, in relation to Dhruva Gana, in particular, Natyashastra provides number of illustrations.

:- Dhruva compositions of Avakrsta type , full of long syllables (Avakrsta) expressing pathos (Karuna) , separation (Viraha) ; or when the character on the stage is fettered , fallen , disabled, fainted and nearing death – should be rendered in Vilamba Kaala (slow tempo).

– When the movement is slow (with wide steps) as during the entry of an elephant; and when songs with long syllables are sung

– Dhruva-s of Sthitha type in slow tempo depicting separation, longing for the beloved, anxiety, restlessness, exhaustion or dejection, should be rendered in Vilamba Kaala (slow tempo).

– With regard to Sthitha Dhruva songs, its twofold aspects (sthana) are described as Parastha and Atma-samsrita . Abhinavagupta explains these terms as referring to songs that help to clearly bring out the pathos the situation. For instance; the character of Sri Rama sings a Dhruva song in anguish pining for his separated beloved Sita it would be Atma-samsrita ( concerned with the character proper); and , the Dhruva song that Lakshmana sings empathising with his brother and sharing his pain that would be Parastha ( concerned with others’ sorrow).

:- Madhyama Kaala is the normal or the standard (middle) Tempo. And, it is particularly recommended for Prasadiki type of Dhruva songs sung in love scenes (Sringara), first meeting of lovers (prathama samagama), recalling a pleasent memory (priya varthalapa) , sweet speech (madhouse bhashi), joy (harsha) and wonder (Adbhutam, Vismaya)).

: – Dhruta the fast Tempo is employed in varieties of occasions:

– When the character is in confusion, wonder, sudden joy or anger.

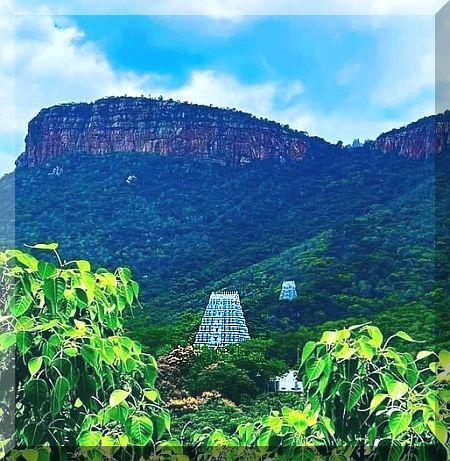

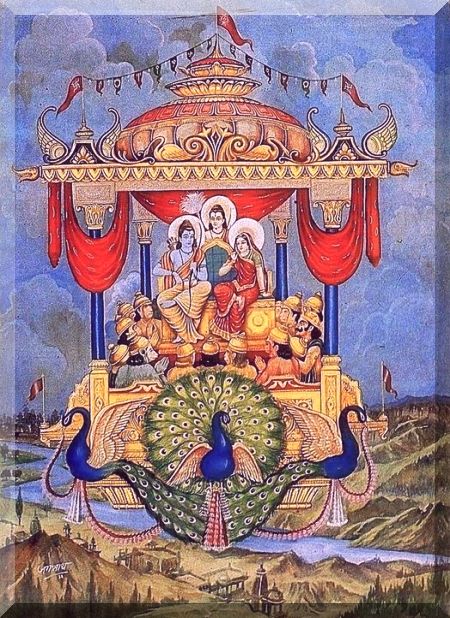

– For Dhruva of short syllables; for quick movement during scenes that depict entry of chariots, aerial-cars (Vimana).

– For Druta type of Dhruva-s having short or rapid notes, employed in situations where there was furious heroism, wonder, excitement, excessive joy or anger.

[A word of caution the concepts of Kaala, Matra , Laya etc as mentioned in the ancient Gandharva and Gana Music are NOT the same as they are understood in the present time.]

[Natyashastra provided rules not merely for singing but also for speech delivery (Vachika) . It mentions that in order to bring out the right effects the speech should be well articulated and should respect the virtues (Dharma) of: Svara (notes), Sthana (voice registers), Varna (pitch of the vowel), Kaku (intonation), and Laya (tempo) – NS.19.43-59.

It specifies that the scenes involving humor (Hasya) and erotic or love (Srungara) the speech should be modulated by Madhyama and Panchama Svaras (notes); acute pitch (Udatta and Svarita); and , medium tempo (Madhya Laya). Where as in the scenes depicting heroics (Vira) and wonder (Adbhuta ) the speech should be in Shadja and Rishabha Svaras; acute and trembling pitch (Udatta and Kampita) ; and , quick tempo (Druta Laya). And, in the scenes of pathos (Karuna) the speech should in slow tempo (vilamba).

As regards the voice registers (Sthana), they vary according to the space (distance) on the stage between the characters. It is said: to call a character that is at a distance, the voice should proceed from the top register (Siras); to call one who is a short distance the voice register should emanate from chest (Uras); and, to speak to one who is standing next the voice register should be from the throat (Kanta). ]

Symbolisms

9.1. Theater in the Natyashastra is a huge symbolism; and , it is projected beyond the natural world. Apart from that , Theater in the sense of Drama functions on many levels of symbolism – through speech (Vachika-abhinaya), costume , make-up (Aharya) gestures (Mudra), exhibiting emotions (sattvika abhinaya) and in music (Gana).

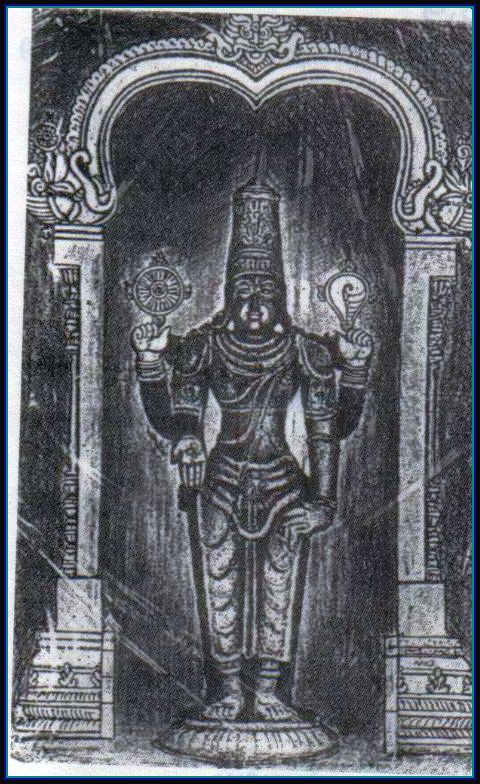

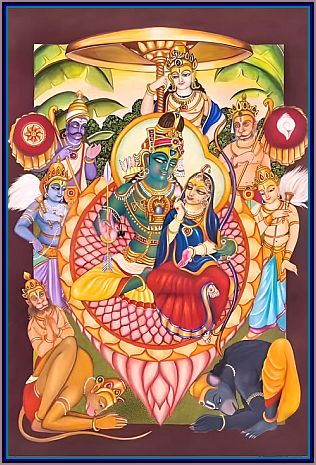

9.2. Dhruva symbolisms are dealt with great detail. Symbols representing the moon, the fire, the sun and the wind; and these are to be used in the case of gods and kings; The night , the moon light, lotus plants, she elephants , rivers and night in the case of queens; The clouds, mountains and oceans are used in the case of demons; The elephants in the rut and royal-swans in the case of superior beings; Peacocks and lotuses in the case of middling’s; Cuckoos , bees in the case of others; Creepers and swans in the case of other women and courtesans; The female bee and female cuckoo in the case other women.

9.3. The entrance song (Pravesiki) is to be sung to indicate anything happening in the fore-noon; and, the exit song (Naiskramiki) to indicate anything happening by day and night. Gentle Dhruva-s are to be sung to indicate the forenoon; and, the songs with excitement to indicate the noon . And, the pathetic Dhruva-s are to be sung in case of afternoon and evenings.

The symbolisms of the Dhruva-s with their evocative suggestions, enriched by melodious music, helped to enhance the aesthetic quality of the theatrical presentation.

Languages of Dhruva Gana

10.1.Bharata states, in general, the languages to be used in a play (pathya) as of four types: Atibhasha (to be used by gods and demi-gods); Aryabhasha (for people of princely and higher classes); Jatibhasha (for common folks, including the Mleccha , the foreigners) and, Yonyantari ( for the rest , unclassified and the tribal)

Bharata in Chapter 17 (verse 48) mentions seven types of Upa-basha (desha-basha) the dialects then in use . And he also mentions the tribal dialects

māgadhy avantijā prācyā śauraseny ardhamāgadhī । bāhlīkā dakṣiṇātyā ca sapta bhāṣāḥ prakīrtitāḥ ॥ 7. 48॥

śakārā abhīra caṇḍāla śa varadramilodrajāḥ । hīnā vanecarāṇāṃ ca vibhāṣā nāṭake smṛtā ॥ 7. 49॥

As for the language of the Dhruva songs, which were sung either by the actors or by the musicians behind the curtain, it was, usually, not Sanskrit (in contrast to Gandharva songs in Sanskrit that were sung during the Purvanga, the preliminaries), but was Prakrit, the regional languages. Natyashastra discusses the features of the Dhruva songs composed in regional dialects ; and , in that context mentions seven known dialects (Desha-bhasha) of its time : Māgadhī, Āvantī, Prācyā, Śaurasenī, Ardhamāgadhī, Bāhlikā and Dākṣiṇātyā (NŚ . 17-48). However, most of the Dhruva-s were composed in Suraseni or Magadhi; and some in Ardha-Samskrita (mixture of Sanskrit and the regional language). The songs addressing to heavenly beings were however in Sanskrit (NS.32.441).

10.2. As regards Śaurasenī, it was the language spoken around the region of Surasena (Mathura area). And, in the play the female characters, Vidūṣaka (jester), children, astrologers and others around the Queens court spoke in Śaurasenī. It was assigned a comparatively higher position among the Prakrita dialects.

prācyā vidūṣakādīnāṃ dhūrtānāmapyavantijā । nāyikānāṃ sakhīnāṃ ca śūrasenyavirodhinī ॥ 7. 51॥

10.3. In comparison, Magadhi , the dialect of the Magadha region in the East as also Ardha-Magadhi and Prachya , also of the East, were spoken in the play by lesser characters such as servants, washer -men, fishermen, , barbers , doorkeepers, black-smiths, hunters and by the duṣṭa (wicked) . Even otherwise, the people of Magadha as such were not regarded highly and were projected in poor light.

māgadhī tu narendrāṇām antaḥpura samāśrayā । ceṭānāṃ rājaputrāṇāṃ śreṣṭhināṃ cārdhamāgadhī ॥ 50॥

10.4. In some versions, there is a mention of Mahārāṣṭrī also. It was a language spoken around the river Godavari and according to linguists; it is an older form of Marāṭhī. In some plays, the leading-lady and her friends speak in Śaurasenī, but sing in Mahārāṣṭrī.

The security guards and doorkeepers were said to speak Dakshinatya (Southern) or Bahliki (Northwest – Ancient Bactria; modern Balkh region) , considered as outsiders.

yaudha nāgarakādīnāṃ dakṣiṇātyātha dīvyatām । bāhlīka bhāṣodīcyānāṃ khasānāṃ ca svadeśajā ॥ 52॥

10.5. Natyashastra (NS.32.56-354) presents more than 116 examples of Dhruva-s in Prakrit in various meters including Vedic meters such as Gayatri, Anustubh, and Tristubh etc.

10.6. The language of the Suraseni or Magadhi (specially the Narukta Dhruva) dialects was usually be simple. And, the songs talked about the things that one sees in nature during the different seasons (Rtu) , such as : the bright sun, the soothing moon, the sparking stars in a cloudless dark night sky , the passing dark clouds laden with water bringing cheer to the hearts of lovers , the thunderous lightning that drives the Lady love into the arms of the lover etc.

10.7. The language of the Dhruva songs sung by women was generally Prakrit. Bharatha says the vocal music should be generally the province of the women as their voice is naturally sweet.

In the next Part let’s talk about Musical instruments mentioned in Natyashastra.

Please click on the picture below

Continued in Next Part

Musical Instruments in Natyashastra

Sources and References

Studies in the Nāṭyaśāstra: With Special Reference to the Sanskrit Drama…

By Ganesh Hari Tarlekar

Sonic Liturgy: Ritual and Music in Hindu Tradition

By Guy L. Beck

Poetics of performance by TM Krishna

Language of Sanskrit Drama Language of Sanskrit Drama by Saroja Bhate

http://www.sanskrit.nic.in/svimarsha/v6/c10.pdf

ALL PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET

Mahamahopadyaya Dr. R. Satyanarayana , who has rendered immense service to various field of study such as Music, Dance, Literature and Sri Vidya, explains that the Dhruva Prabandha after which Suladi was patterned employed nine different types of Taalas, while they were sung as a series of separate songs. Thereafter, there came into vogue a practice of treating each song as a stanza or Dhatu (or charana as it is now called) of one lengthy song. And, it was sung as one Prabandha called Suladi. Thus, the Suladi was a Taala-malika, the garland of Taalas or a multi-taala structure.

Mahamahopadyaya Dr. R. Satyanarayana , who has rendered immense service to various field of study such as Music, Dance, Literature and Sri Vidya, explains that the Dhruva Prabandha after which Suladi was patterned employed nine different types of Taalas, while they were sung as a series of separate songs. Thereafter, there came into vogue a practice of treating each song as a stanza or Dhatu (or charana as it is now called) of one lengthy song. And, it was sung as one Prabandha called Suladi. Thus, the Suladi was a Taala-malika, the garland of Taalas or a multi-taala structure.

iphone 4S kopen

September 18, 2012 at 6:48 am

I’ve found youre article on my iPhone 4 Kopen and i wanna say thanks for it! It’s a nice www you have over here! I’ll visit it more in the future! Thanks, Frank

sreenivasaraos

September 18, 2012 at 4:05 pm

Dear kopen ,thank you for the appreciation.The post , because of its very nature, has many Sanskrit terms . I trust you did not have much difficulty in following the subject. Please check other blogs too. Regards

sreenivasaraos

September 18, 2012 at 4:07 pm

thank you.Regards

sreenivasaraos

September 22, 2012 at 6:49 pm

Dear libreria online , Thank you for the visit . As I mentioned , I am not very familiar with the technical aspects. I welcome help and guidence. Regards

Saddha

November 27, 2013 at 1:33 am

Thank you for quite a detailed article in the Brahmanical Sama Veda. However, Krishna in The Bhagwad Gita was not talking about the Brahmanical Sama Veda when he said, “amongst Vedas I am The Sama Veda”.

The Bhagwad Gita clearly does not mean that the tunes/melodies of the Sama are the most important!

As the Gita says in chapter 2 “Buddhau Saranam Anvicche!”

There is another Sama Vedas — aka Dhamma Vedas, this was revealed by Lord Buddha! This is known as the Nikayas or Tripitika — unfortunately preserved by every nation except India.

Krishna when he said he was the Sama Veda meant “to be in tune”– to be in tune with what? The Dharma!

Who tune themselves with the Dharma? Buddhists since only they have the Dharma Chakra! Lord Buddha uses the word “Sama” several times in various Suttas to describe tuning in accordance with The Dharma,

Thanissaro Bhikku states:

Dissonant and harmonious (visama and sama): Throughout ancient cultures, the terminology of music was used to describe the moral quality of people and acts. Discordant intervals or poorly-tuned musical instruments were metaphors for evil; harmonious intervals and well-tuned instruments were metaphors for good. In Pali, the term sama — “even” — describes an instrument tuned on-pitch. AN 6.55 contains a famous passage where the Buddha reminds Sona Kolivisa — who had been over-exerting himself in the practice — that a lute sounds appealing only if the strings are neither too taut nor too lax, but “evenly” tuned.

Lord Buddha describes this tuning to the Dharma process in MN 41 PTS: M i 285 MLS ii 379 Saleyyaka Sutta: (Brahmans) of Sala translated from the Pali byThanissaro Bhikkhu

“Householders, it’s by reason of un-Dhamma conduct, dissonant [1] (visama) conduct that some beings here, with the break-up of the body, after death, reappear in the plane of deprivation, the bad destination, the lower realms, in hell. It’s by reason of Dhamma conduct, harmonious [1] (Sama) conduct that some beings here, with the break-up of the body, after death, reappear in the good destinations, in the heavenly world.”

The true Sama Vedas is not knowledge of musical notes, it is knowledge and living in tune with the universe through the Dharma Chakra.

sreenivasaraos

November 27, 2013 at 2:50 am

Thank you Dear Saddha for your detailed explanation.

I am grateful.

Regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:28 am

sreenivas: thanks to you . now i know what is sama veda. i belong to yajur(yajus shakha) but my wife was born a sama vedi. so the first time i heard chants in musical form was during my wedding, and after 45 years i read your blog to understand the origin of sama veda

rgds, girdhar

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:28 am

dear shri gopal,

thank you for the comments. i am glad you could relate to it.

the later portion of the blog, i fear, became rather technical.

regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:29 am

that was a wonderful blog. i have to read it again & assimilate a lot of things. just loved it. pranaams to you. you are great !

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:29 am

sir, i posted a short blog on colors and music. may see if time permits.

http://dmrsekhar.sulekha.com/blog/post/2008/09/svetomusica.htm

dmr sekhar

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:30 am

dear shri sekhar,

thank you for your detailed response. i greatly appreciate the gesture.

i understand, in sound → color synesthesia, individuals experience colors in response to tones or other aspects of sounds. a lot of that subject is highly technical, and i do not pretend i understand all of that. i am posting a few words from the little i know and from what i read.

the theory of synchronizing music with colors is highly interesting. there have been theories in that regard even from the time of pythagoras. in the subsequent centuries others too followed it . there has, of course, been plenty of debate around the issue. edwin d. babbitt, scientist who has done work in that field confirms (in his the principles of light and color) the correspondence of the color and musical scales:

“as c is at the bottom of the musical scale and made with the coarsest waves of air, so is red at the bottom of the chromatic scale and made with the coarsest waves of luminous ether. as the musical note b [the seventh note of the scale] requires 45 vibrations of air every time the note c at the lower end of the scale requires 24, or but little over half as many, so does extreme violet require about 300 trillions of vibrations of ether in a second, while extreme red requires only about 450 trillions, which also are but little more than half as many. when one musical octave is finished another one commences and progresses with just twice as many vibrations as were used in the first octave, and so the same notes are repeated on a finer scale. in the same way when the scale of colors visible to the ordinary eye is completed in the violet, another octave of finer invisible colors, with just twice as many vibrations, will commence and progress on precisely the same law.”

the theosophists too, especially madam blavatsky, putforward theories relating colors to the seven types of constitution of man and the seven states of matter. (please check- it is in the same page).she was primarily trying to relate the aura in and around the human body to their colors.

you made a mention, also, of ragas and colors. the indian music made attempts to translate the emotional appeal of a raga into visual representations. that gave rise to schools of paintings called ragamala, in which each raga was personified by color, mood, a verse describing a story of a hero and heroine (nayaka and nayika). the colors, substance and the mood of the ragamala paintings were determined not by the individual notes that go to construct the scale of a raga, but by the overall mood , bhava and context of the raga.

in the traditional indian morphology, the colors of the deities represent and convey their attributes. for instance, the highest divinities with sublime attributes (gunas) are sky blue signifying their true infinite nature; shiva, the ascetic the supreme yogi is gauranga the colorless- without any attributes; hanuman and ganesh are red like the blood full of energy, vitality and life; and kali’s black does not signify absence of color but is the sum and culmination of all colors and energies in the universe.

coming back to your subject, you might be interested to check the site that talks of people who “see” music, or sounds. the article says it is another common form of synesthesia, to have colors associated with specific tones, so that listening to music becomes a more intense and complex experience. with your scientific training and background, i am sure you would be in a better position to appreciate it.

i am told there are musicians in hollywood who find that letters and numbers represent colours, rainbows of textures, rainbows of moods and feelings too.

there have been attempts in the other direction too,of translating individual colours into music with the aid of compute r graphics.

i understand there are schools that help the aspirants’ to hone their synesthesia condition.

much study needed to understand this phenomenon.

thank you for introducing me to a fascinating subject.

regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:32 am

whether by intent, or by research or by serendipity, the twelve basic swaras have been discovered time and again by civilisations across the world. Some however have discovered additional quarter tones, and have developed different forms of scales- with upto 31 tones in a scale. The Vedic form of M G R S D- S N D P G (Nidhana or diminishing order- also a convergent order) was converted to the more flexible ascending sequence leading to progressive flexibility as decadence set in…

some civilisations have 5 tonal octaves, some have more. all have to go through till the chromatic notes are (re-)discovered, independently. civilisation has been here longer, and degraded and then revamped. music has always been on the ascendancy!

I liked reading your post- will be keeping note of this!

regards

PP

Plasticpoet

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:32 am

Your article is mind blowing for person like me.

Hats off to you

Do you know me? Or my music?

Am I in your city? What is you phone number and address?

Sablu

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:33 am

Dear Shri Sablu, Yes, as you said, it might very likely be by chance you bumped into this old blog while you were lost in the ‘Recent Comments’ page. Thank you. Since you consider it ‘mindboggling’ for a person like you, I reckon you would be interested in a few other articles I wrote on music. The ones that quickly come to my mind are: The state of music in the Ramayana; Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar and Hindustani music; the Music of Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar; and the music of Shri SRajam (a great musician scholar and a creative artist; he was the uncle of our Shri VS Gopal who writes and sings delightfully on Sulekha).You may like to click on the links.

As regards the several things you mentioned in your comment as also in your note, well… I usally live in Cincinnati –OH; and Bangalore is the location with reference to which I check news updates etc. I am now visiting India; may be here for another couple of months.

I am truly not surprised if you have not noticed me on Sulekha during all these four years. The reasons are many and they are quite simple: I am not very active on Sulekha; I did not participate in any of the tag –games; I have also not contested in the ongoing EYC series; most of the friends who kept in touch with me have since migrated out of Sulekha; now, I do not know many; I have not written or commented much; not many read what I write and, what I have posted is truly not readable (many have groaned about the length). A bright star on the Sulekha horizon once referred to me as ‘the guy who writes about the dead who do not contradict’. I consider that sums me up pretty well and almost aptly. The reasons for not knowing me, you see, are quite many. They are all valid; and without prejudice. It’s OK.

Sablu…Yes, I have, of course, seen the name many times spoken with affection, warmth and regard. I am aware; Sablu is popular and is among the elite here. That is great. And, about why I have not checked into Sablu music: I usually log into Sulekha late in the night when most have done with the computer and gone to bed. I said ‘most’ because, the one who keeps company with me is a little boy of just over three; and he delights in running round the house, up and down the stairs, jumping and turning somersaults when no one disturbs him. During those silent hours I prefer to just read or write than turning on music. I normally spend no more than ninety minutes a day on Sulekha.

Now that I will be here where I am surrounded by sound all the time, I will surely check into your link with pleasure and listen to that with delight.

Thank you for the comment and the Note.

Warm Regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:33 am

Thank you so much Sir,

I’m highly honored by your kind words and great response. I will love to read thousands blogs of yours in music which made me so glad today to go through your precious blog. Boss such thing is gold and silver even I invest lakhs I will not get such relevant info.

Does not matter you listen to my music as per your convenience and leisure.So you are actually in OH. Oh I’m so sorry I thought you are Bangalore based. Please do welcome here.

And please do write more music blogs like you wrote on samveda. i will go through one by one as you also mentioned some links in your comment.

Kudos to your great knowledge and I touch your feet.

regards

SM

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:34 am

Hi,Thank you for posting. If you dont mind can I make a suggestion. The equivalent names for shadja, Rishabha, Gandhara etc are not C , Db, D , Eb etc.. its == Pi, m2, M2, m3(A2), M3, P4, A4(Dim5), P5, m6(A5), M6, m7, M7 ,8ve( Higher Shadja)P = PerfectA = AugmentedDim= DiminishedM = Majorm = MinorWhen sung:Ascending and DescendingDo, Di, Re , Ri, Ma, Fa, Fi, Sol, Si, La, Li , Ti, Do — Do, Ti, Te, La, Le, So, Se, Fa, Mi,Me, Re, Ra, Do

GODWIN

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 8:34 am

Dear Godwin, Thank you for breathing fresh life into an old and a forgotten blog. Thank you also for the corrections suggested. I shall try to edit the blog. But, the problem is that in the present state of Sulekha editing a blog is a risky proposition. I shall wait for a while // Para// Btw, I noticed in the scholarly essay “Samaveda und Gandharva” included in the book “Ritual, State, and History in South Asia: Essays in Honour of J.C. Heesterman “(page 146) it is mentioned that “Madhyama = F28; Gandhara = E; Rsabha = D; Sadja= C; Dhaivata = A; Nishadha = H; and, Panchama = G” . Please let me have your views before I try to edit the blog-post.// Para// Here is the link to the article “Samaveda und Gandharva”http://books.google.com/books?

Priya

February 19, 2018 at 11:34 am

I am trying to learn how to sing samaveda.I have read your blog. I did not understand how to chant as per the numbers. what is the sound of ka and ra appearing on the letters. I know KY and RV chanting.can you help me with SV chanting

sreenivasaraos

February 19, 2018 at 4:01 pm

Dear Priya,

Wow… It is great to see you trying to chant.

But, Maa, it is not easy; and, definitely you cannot get it right unless you are trained and guided by a teacher. It has to be a face-to-face exercise; and has to be practiced diligently, over a period.

By the way, the indications on the top of the letters are numerals (from one to seven) to suggest their note-delineations (Sama vikara).

[According to Samvidhana Brahmana and Arsheya Brahmana, Sama-Gana employed seven Swaras (notes): 1. Prathama; 2. Dvitiya; 3. Tritiya; 4. Chaturtha; 5. Panchama or Mandra (low); 6. Shasta or Krusts (high); and, Antya or Atiswara (very high)]

For instance; please follow the text along with the chanting of the verse 594 of Sama Veda Samhita- (Listen to pundits chanting in streaming audio.)

at https://sanskrit.safire.com/SamaVeda.html

The numbers on top are note delineations. and , where it is written within brackets as Dve or Tri , it means that the words have to repeated two or three times .

Follow the text as you listen carefully.

*

You may also enjoy listening to some passages from Sama Veda Samhita kauthuma shakha at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TBNEizCsor0

Some parts the chanting are taken from the text at

https://sanskritdocuments.org/doc_veda/sv-kauthuma.html?lang=iast

You may be able to recognize the following verses ; as also Gayatri mantra at 6.44of the tape

text at 1:42 indraya soma suShutaH pari sravApAmIvA bhavatu rakShasA saha . mA te rasasya matsata dvayAvino draviNasvanta iha santvindavaH .. 561

2:14 saM te payA.Nsi samu yantu vAjAH saM vR^iShNyAnyabhimAtiShAhaH . ApyAyamAno amR^itAya soma divi shravA.NsyuttamAni dhiShva .. 603

3:57 yasho mA dyAvApR^ithivI yasho mendrabR^ihaspatI . yasho bhagasya vindatu yasho mA pratimuchyatAm . yashasvyA3syAH sa.N sado.ahaM pravaditA syAm .. 611

R^itasya jihvA pavate madhu priyaM vaktA patirdhiyo asyA adAbhyaH . dadhAti putraH pitrorapIchyA3M nAma tR^itIyamadhi rochanaM divaH mA tvA mUrA aviShyavo mopahasvAna A dabhan . mA kIM brahmadviShaM vanaH .. 732

pavamAna ruchAruchA devo devebhyaH sutaH . vishvA vasUnyA visha .. 905 ubhayataH pavamAnasya rashmayo dhruvasya sataH pari yanti ketavaH . adI pavitre adhi mR^ijyate hariH sattA ni yonau kalasheShu sIdati ..

If you are seriously interested , please secure the guidance of a learned teacher.

Please keep talking

Cheers