Continued from Part One – Overview

Part Two (of 22) –

Overview (2) – continued

North – South branches

1.1. The Music of India, today, flourishes in two main forms: the Hindustani or Uttaradi (North Indian music) and the Karnataka or Dakshinadi Samgita (South Indian music). Both the systems have common origins; and spring from the traditional Music of India. But, owing to historical reasons, and intermingling of cultures, the two systems started to diverge around 14th Century, giving rise to two modes of Music.

1.2. In that context, Sarangadeva’s Sangita-ratnakara (first half of 13th century) is of particular importance, because it was written just before influence of the Muslim conquest began to assert itself on Indian culture. The Music discussed in Sangita-ratnakara is free from Persian influence. Sangita-ratnakara therefore marks the stage at which the ‘integrated’ Music of India was before it branched into North-South Music traditions.

It is clear that by the time of Sarangadeva, the Music of India had moved far away from Marga or Gandharva, as also from the system based on Jatis (class of melodies) and two parent scales. By his time, many new conventions had entered into the main stream; and the concept of Ragas that had taken firm roots was wielding considerable authority. Sarangadeva mentions names of about 267 Ragas.

1.3. In regard to the Music in South India, the Persian influence, if any, came in rather late. Written in 1550, the Svara-mela-kalanidhi of Ramamatya, a minister in the court of Rama Raja of Vijayanagar, makes it evident that the Music of India of that time was yet to be influenced by the Persian music. Somanatha (1609) in his Raga-vibodha confirms this view, although he himself seemed to be getting familiar with Persian music.

The Persian influence

2.1. The Muslim Sultanat began to get foothold in India by about 1200 A.D, when all major Hindu powers of Northern India had lost their independence,

Conquering Muslims came in contact with a system of Music that was highly developed and, in some ways, similar to their own. The poet Amir Khsru an expert in Music in the court of Allauddin Khilji, Sultan of Delhi (1290-1316) was full of praise for the traditional Music of India. And, at the same time, Khsru was involved with the Sufi movement within Islam which practiced music with the faith that Music was a means to the realization of God.

2.2. But, that didn’t seem to be the general attitude among most of the later Muslim rulers. India in the sixteenth century was politically and geographically fragmented. There were also conflicting cultural practices and prejudices. Though the Mughal era, in general, witnessed musical development, Musicians and Music, as such, did suffer much.

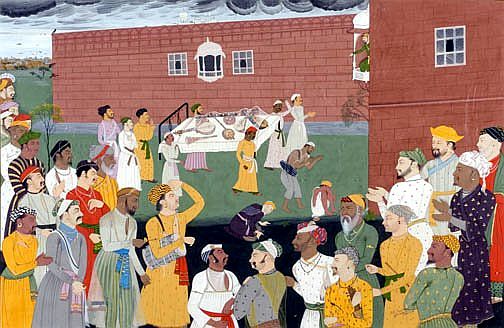

For instance; Aurangzeb (1658-1707) threw the whole lot of musicians out of his court. The grieving , hapless musicians , wailing and lamenting carry the ‘bier’ of music and symbolically bury ‘music’ in Aurangzeb’s presence. Aurangzeb,undaunted, retorted “Bury it so deep that no sound or echo of it may rise again” (Muntakhab-al Lubab, p.213)

The unfortunate artists , no longer able to support themselves, were scattered and had to seek their livelihood in humbler provincial courts. In the process, the accumulated musical knowledge and musical theories developed over the years were lost. The priority of the professional musicians, at that juncture, was to make living by practicing music that pleased their new-found patrons.

2.3. Yet; Music and its traditions did manage to survive and flourish in India despite the Muslim rule and its harsh attitudes towards Music in general and the Indian in particular. Persian Music along with Indian Music was commonly heard in Indian courts; and, the two systems of Music did interact. Amir Khsru, who served in courts of many patrons and assimilated diverse musical influences, is credited with introducing Persian and Arabic elements into Indian Music.

These included new vocal forms as well as new Ragas (Sarfarda, Zilaph), Taalas; and, new musical instruments such as Sitar and Tablas (by modifying Been and Mridamgam). Another modification of Been is said to be Tanpura (or Tambura, Tanpuri) that provides and maintains Sruti. (Till then, it is said, flute – Venu – provided Sruti).

Of the vocal forms that were developed, two are particularly important: Qaul, the forerunner of Qawwali, a form of Muslim religious music; and, Tarana a rhythmic song composed of meaningless syllables.

[As regards Sitar, Pandit Ravi Shankar points out that documentation of the history of Sitar between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries is lacking; and, suggests that Khsru ‘adapted’ probably a ‘Tritantri Veena’, already known to Indians along with its many variations. Khsru gave it the name ‘Sehtar’; reversing the order of the strings in the instrument; and placing them in present form i.e. ‘the main playing string on outside, and the bass strings closer to the player’s body’. This order is opposite to what we find on Been. But, strangely, the Persian treatise on music written in Gujarat in 1374-75 A.D. Viz. Ghunyat-ul Munya does not mention Sitar or Tabla, though it mentions a number of Tat, Vitat, and Sushira and Ghana instruments.– Bhartiya Sangeet ka Itihaas, Ghunyat ul- Munya, pp. 52-62, Dr. Pranjpay]

2.4. Even during the Muslim rule, Music did enjoy some patronage. It appears Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq (1325-1351) had in his court as many as 1200 musicians. Many other Muslim rulers were also patrons of Music. And, some of them were themselves musicians.

For instance; Husyan Shah Sharqi (1458-1528) Sultan of Jaunpur*, a musician in his own right, is credited with introducing a new form of song–rendering, Khyal (Khayal) lending greater scope for improvisation and technical virtuosity than did the ancient Dhrupad.

And, Ibrahim Adil shah (1582-1636) of Bijapur (Karnataka), a poet and musician, in his Kitab-i-Nauras (Nava Rasa) compiled his poems set to music. He is also credited with bringing to fore the Raga-mala paintings, depicting pictorial representations to Ragas, their moods and seasons.

Similarly, it is said, the. Khyal singing came into its own due largely to the efforts of Sadarang and Adarang during the reign of Mohammad Shah Rangeela (1719-1748).

[* Swami Prajnanananda in his A History of Indian Music (Volume One- Ancient Period) under the Chapter ‘Evolution of the Gitis and the Prabandhas’ writes:

During Raja Mansingh‘s time Dhrupads were performed in different Ragas’ and Raginis. Khayal form is purely imaginative and colorful. There are different opinions about its evolutions (1) Some say Khayal evolved from Kaivada-prabandha, (2) it originated from Rasak or Ektali-prabandha, (3) it evolved from Rupaka-prabandha, (4) it was created on the image of Sadharani-giti.

In the opinion of Thakur Jaideva Singh, Khayal form is a natural development of ‘Sadharani-Giti’. So Khayal form was neither invented by Indo-Persian poet Amir Khusro nor by Sultan of Jaunpur Hussain Sharqui. The Khayal of slow tempo was designed and made popular by a noted Dhrupadist and Veenkar Niyamat Khan who was in the Court of Sultan Muhammed Shah in 18th Century A.D. Khayal already existed in some form at the time of Akbar in 16th-17th century and it was practiced by Hindu and Muslim musicians like Chand Khan, Suraj Khan and Baj Bahadur. There are lighter forms like Thumri, Dadra and Gazal etc.

[Sadharani –Giti was a style of rendering Dhrupad combining in itself the virtues of four other Gitis or modes of singing that were in vogue during the early Mughal times : Shuddha–Giti (pure, simple, straight contemplative); Bhinna Giti (innovative, articulated, fast and charming Gamaka phrases); Gaudi Giti (sonorous, soft, unbroken mellow stream of singing in all the three tempos); Vesara or Vegasvara Giti (fastness in rendering the Svaras).]

2.5. Even among the Hindu Kings there were Musicians of repute, such as Raja Mansingh of Tomar, Gwalior (1486-1516). He was a generous patron of the arts. Both Hindu and Muslim musicians were employed in his court. He brought back the traditional form of Dhrupad music (Skt. Dhruvapada). He edited a treatise Man Kautuhal, put together by the scholars in his court, incorporating many of the innovations that had entered traditional Indian music since the time of Amir Ahusraw. Raja Mansingh is also credited with compiling/editing three volumes of songs: Vishnupadas (songs in praise of lord Vishnu); Dhrupads; as also, Hori and Dhamar songs associated with the festival of Holi. It is said; later during 1665-66 Fakirullah Saifkhan, a musician in the court of Jahangir (1605-27) partially translated Raja Mansingh’s Man Kautuhal into Persian.

[Please do read the article about the state of Dhrupad Music in the Mughal reign during seventeenth-century, written by Katherine Butler Schofield Professor in Music at King’s College London; and, brought out by the Royal Asiatic Society and the British Library.

Please do not miss to see the colourful illustrations of folios of the Dhrupad songs during the Mughal period.

She says; of all the arts and sciences cultivated in Mughal India, outside poetry, it is the music that is by far the best documented. She also tells us about the role and power of music at the Mughal court at the empire’s height, before everything began to unravel

Hundreds of substantial works on music from the Mughal period are said to be still extant, in Sanskrit, Persian, and North Indian vernaculars. The following is a brief extract from her talk.

The first known writings in Persian on Indian music date from the thirteenth century CE; and, in vernacular languages from the early sixteenth. These often were translated directly from the Sanskrit theoretical texts.

A particularly authoritative model was Sarngadeva’s Saṅgīta-ratnākara, the Ocean of Music, written c. 1210–47 for the Yadava ruler of Devagiri (Daulatabad) in the Deccan. This was initially translated into Persian and Dakhni.

Later, the text also came out in vernacular languages, in rather interesting ways. These versions included large additional sections presenting contemporary material chosen from the region in which they were written.

Among such improvised versions, Katherine Butler Schofield mentions, Ghunyat al-Munya or Richness of Desire, the earliest known Persian treatise on Hindustani music, composed in 1375 for the Delhi-sultanate governor of Gujarat.

And the other being, Shaikh Abd al-Karim’s Javāhir al-Mūsīqāt-i Muḥammadī or Jewels of Music, a unique Persian and vernacular manuscript produced at the Adil Shahi court of Bijapur (Karnataka).

Though the Javāhir has its core the Dakhni translation of Sarangadeva’s Sangita ratnakara, it deviates from the main text in number of ways. The Javāhir sidesteps the traditional discussions on Ragas, their concepts, framework and varied forms, which perhaps was getting rather stale by then. Instead, it introduced the new and vibrant concept of Ragamala (garland of Rāgas).

Katherine Butler Schofield mentions that the Sanskrit authors, in the Mughal domains, continued to write a variety of musical texts. But, what was more notable, during the seventeenth century, was the effort to re-codify and systematise Hindustani music, in new ways; and, in more accessible regional languages, especially suited to the Mughal era.

From there, the translations or the re-rendering of the older texts Hindustani music seem to have moved from Persian into Hindi, Brajbhasha and other vernaculars , during the reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan. For instance; the well-known Sahasras or Thousand Sentiments, a compilation of 1004 Dhrupad songs created by the early sixteenth-century master-musician Nayak Bakhshu, was re-rendered into Brajbhasha, with an introduction in Persian.

The other instance of re-codifying the principles of Hindustani music was the rendering of Damodara’s Sanskrit text, Saṅgīta-darpaṇa or Mirror of Music, of early seventeenth century, into Brajbhasha by Harivallabha during the mid seventeenth-century. Later, in eighteenth-century, it was followed by a gloss in modern Hindi by a hereditary musician, Jivan Khan

Another example is an eighteenth-century interlinear copy of the premier Sanskrit treatise of the early seventeenth century, Damodara’s Saṅgīta-darpaṇa or Mirror of Music. Here, alongside the Sanskrit text, we have Harivallabha’s hugely popular mid seventeenth-century Brajbhasha translation, combined with an eighteenth-century gloss in modern Hindi by a hereditary (khandani) musician, Jivan Khan.

**

The first major piece of Mughal theoretical writing in Persian on Hindustani were the chapters on music and musicians written by Akbar’s great ideologue Abu’l Fazl in his Ā’īn-i Akbarī (1593).

But, the process really took off during the reign of Aurangzeb. The translations during his reign were predominantly in Persian. The more prominent among such translated texts, which occupied the canonical position for the next two hundred years, were:

1) The Miftāḥ al-Sarūd or Key to Music: a translation of a lost Sanskrit work called Bhārata-saṅgīta by Mughal official Qazi Hasan, written in 1664, at Daulatabad

2) The Rāg Darpan or Mirror of Rāga, a work written in 1666 by Saif Khan Faqirullah, completed when he was governor of Kashmir. Faqirullah cites extensively verbatim from the Mānakutūhala, an early sixteenth-century Hindavi work traditionally attributed to Raja Man Singh of Gwalior.

3) The Tarjuma-i Kitāb-i Pārījātak: the 1666 Translation of Ahobala Pandit’s Sanskrit masterpiece Saṅgītapārijāta by Mirza Raushan Zamir.

4) The fifth chapter of the Tuḥfat al-Hind or Gift of India: 1675 Mirza Khan’s famous work drawn , mainly, from Damodara’s Mirror of Music and from Faqirullah’s Mirror of Rāga. The text which was exhaustive became hugely influential in later centuries.

5) The Shams al-Aṣwāt or Sun of Songs, written in 1698, by Ras Baras Khan kalāwant, son of Khushhal Khan and the great-great-grandson of Tansen. This work is primarily another Persian translation of Damodara’s Sangitadarpana or Mirror of Music. The text is enriched with invaluable insights from the orall tradition of Ras Baras’s esteemed musical lineage.

6) The Nishāṯ-ārā or Ornament of Pleasure, was prepared , most likely late seventeenth-century prior to1722 , by the hereditary Sufi musician Mir Salih qawwāl Dehlavi (of Delhi).

These and other treatises written during the time of Aurangzeb cover, in significant depth, a wide range of musical terrain. Their overriding concern and unifying theme, was about the nature of the Rāga, their derivatives and structures.]

2.6. The Persian influence brought in a changed perspective in the style of rendering the classical Indian music as it then existed in North India. The devotional Dhruvapad transformed into the Dhrupad form of singing. And, the Khayal developed as a new form of singing art-music, in the 17th century.

Taking positions

3.1. The periods of 16-18th centuries were rather confusing. While the songs of the Indian music were either in Sanskrit or in a regional language, the Muslim singers found it difficult either to pronounce the words or to grasp the emotional appeal.

Similarly, Hindu musicians found it difficult to render songs in Persian, some of which elaborated Muslim religious themes.

As a result, in either case, in the Music of North India, the words of the songs lost their importance or were of little significance to the singers, while all the attention was focused on voice culture, melodic improvisation and style of rendering the music.

Further, an increasing number of Music-scholars of the North discussed Hindustani Art Music and wrote their works in Persian, Urdu, Hindi and other regional languages, instead of in Sanskrit. Such an admixture of Indian-Persian-Muslim influences over a period of four centuries from the sixteenth resulted in the Hindustani music of today.

3.2. Thus, while in the Music of South India the texts were written mainly in Sanskrit ; and while its Music continued to be based in structured formats (such as Kriti) and lyrics (Sahitya); the Hindustani music focused on experimenting with the possibilities of improvising the musical elements of a song. While Karnataka music retained the traditional octave (sapta svara), the Hindustani music adopted a scale of Shudha Svara saptaka (octave of natural notes). And at the same time, both the systems exhibited great assimilative power, absorbing folk tunes and regional tilts; and elevating many of the regional tunes to the status of Ragas.

North- South interaction

4.1. The North and South regions of India had been aware of the developments in each other’s system of Music, art etc; and, there were also attempts to exchange.

For instance; Mahendra Varma Pallava (CE 600-630), who ruled from Kanchipuram in the seventh century, published some compositions of the North by having them engraved on the rocks on the hill at kudumiyanmalai, in Sanskrit (in Pallava-Grantha characters) with footnote in Tamil. The inscription is actually an extract of Music lesson (Abhyasa gayana) for developing four types of finger–techniques (Chatush-prahara-Svaragama) for playing on the Veena. The type of the Veena is mentioned as Parivardhini.

The inscription which is in seven sections mentions Ragas such as: Madhyamagrama, Shadjagrama, Shadava, Shadharita, Panchama, Kaisikamadhyama and Kaisiki. It is said in the inscription that these lessons were ‘made for the benefit of the pupils by the King who is the devotee of Maheshwara the Supreme Lord and the disciple of Rudracharya’.

The King Nanyadeva (11th century) who established the Rastrakuta dynasty of Karnataka in Mithila (Nepal) in his commentary on Natyashastra refers to Karnata-pata Taanas and to many other elements of the music of the South.

Sarangadeva in his Sangita Ratnakara (Chapter: Ragadhyaya; Section : Ragangadi Nirnaya Prakarana ), while enumerating ten vibhasha Ragas, mentions a Raga with a Kannada name Devara-vardhini.

Every author of the South based his theory of Karnataka Samgita on the texts of Bharatha, Dattila, Matanga and Sarangadeva.

The two systems have continued to influence each other even after Muslim rule . And, that increased since about the 14th century, in a number of ways. For instance; Gopala Nayaka traveled all the way from the South to become the court musician of Allauddin Khilji (1295-1315) in the North. He cultivated the friendship of the Persian musicologist, Amir Khusrau. Their discussion led to the development of new Ragas. These were incorporated in the treatise on music by the 16th century scholar Pundarika Vittala.

4.2. Till about the late 16th century both the South and North traditions followed the same set of texts.

[Justice Sri T L Venkatarama Aiyar , in his biography of Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar (National Biography Series, National Book Trust, 1968) , observes that during the days of Venkatamakhin , the differences between the Karnataka and Hindustani systems were not much pronounced. And, Venkatamakhin was well versed in both the systems of Music; and, he composed Lakshana-Gitas on Ragas that were known to be derived from the Outhareya -Ragas.

Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar followed Venkatamakhin’s system; he was also well versed in the Dhrupad of the Hindustani system.. He created numerous musical gems, assimilating the the beauties of the either melodic systems. ]

Pundarika Vittala (1583 approx) a musician-scholar from Karnataka (from around Shivaganga Hills about 50 KMs from Bangalore), who settled down in the North under the patronage of Muslim King Burhan Khan, wrote a series of books concerning Music of North India: Vitthalya; Raga-mala; Nartana-nirnaya; and his famous Sad-raga-chandodaya.

Later he moved to the court of the prince Madhavasimha and Manasimha, feudatory of Akbar. Here he wrote Raga-narayana and Raga-manjari.

In his writings, Pundarika Vittala carried forward the work of Gopala Nayaka (14th century) of grafting Karnataka music on to the newly evolving North Indian music. In his work Raga-manjari, Pundarika Vittala adopted the parent scale (Mela) classification of Ragas as was devised by Ramamatya (Ca. 1550) in his Swaramela-Kalanidhi. (Ramamatya, in turn, is said to have taken the term Mela meaning ‘group’ and its concept from Sage Vidyaranya’s (1320-1380) Samgita Sara.) Pundarika listed 20 contemporary Ragas of North into Melas, which were not identical with their South Indian examples.

4.3. Somanatha (1609 A.D) a musician scholar hailing from Andhra Desha, largely followed the theories of Pundarika Vittala. Somanatha in his Raga-vibodha mentions 51 Ragas, of which 29 are used in the Music of the present-day: 17 in Karnataka Music, 8 in Hindustani and 4 in both the systems. Some scholars surmise Somanatha’s Ragas mostly correspond to modern Hindustani Ragas; and, though the names of some his Ragas resemble those in Karnataka system it is likely they developed along different lines.

Somanatha is also said to have brought into vogue the practice of writing notations (Raga-sanchara). Raga-vibodha is perhaps the only example before the modern times of any Indian Music using Notations. But, sadly, this valuable text did not receive the level of attention that it deserved.

He is also credited with outlining the rules regarding the time of performance, their special characters (Raga-lakshana) or the atmosphere of some of the Ragas. Some of his concepts are still relevant in Hindustani Music, but have not found place in Karnataka Samgita. For instance; Somanatha in chapter four of his Raga-vibodha describes Raga Abhiri (equivalent to Abheri as it is known now) as a woman (Abhira), dark in complexion, wearing a black dress adorned with a garland of fresh flowers around her neck, attractive ear ornaments. She has a soft and a tender voice; and, wears her hair in beautiful strands.

[Abira is surmised to be a pretty looking Gopi of the Abhira tribe of Mathura region. She is an attractive looking dark complexioned tribal girl. In the traditional Indian Music, dark complexion of the Ragini and her dark clothes correspond to the predominant note (Amsa) Pa]

4.4. The other significant work that attempted to introduce the elements of South Indian music in the North was Pandita Ahobala (early 17th century) who described himself as a ‘Dravida Brahmana, the son of Samskrita Vidwamsa Sri Krishna Pandita’.

Pandita Ahobala’s Samgita Parijata pravashika describing 68 types of Alamkaras or Vadana-bedha is said to be an improvement over Somanatha’s Raga-vibodha. And, it is regarded by some as the earliest text of the North Indian Music. Following Ramamatya and Pundarika Vittala, Ahobala classified 122 Ragas under six Mela categories. Instead of using specific names for his scales, Ahobala used phrases like vikrta svara, komal, tivra, tivratara, and so on. His scale of Shuddha notes, it is said, corresponds to the current Kafi Thath of the Hindustani system.

Pandita Ahobala’s famous Sangita Parijata was translated into Persian by Mirza Raushan Zamir (1666) as Tarjoma -yi- parijatak, with his own comments.

4.5. There were some other works that classified Ragas (including those of the North) according to Melas, such as: Rasa Kaumudi by Srikantha (Ca. 1575) a South Indian musicologist who migrated North; Raga Tarangini by Locana Kavi (?) recognizing 12 Mela Ragas and 86 Janya (derivative) Ragas which included some Ragas attributed to Amir Kushro; and, Hrdaya kautuka and Hrdaya Prakasha by Hrdaya Narayana Deva (Ca.1660).

South coming close to North

5.1. By the end of 17th century the classical styles of the two strands of Music had stabilized in their own manners. Seeing that music of North and South were drifting apart in technical aspects, many scholars did make efforts to harmonize the two systems.

5,2, For instance, in the South, Venkatamakhin (1660), author of the monumental Chaturdandi Prakashika which re-structured the Karnataka Samgita, in his list of Desi Ragas included Bhibhas, Hammir, Bilaval, Dhanashri and Malhar which are primarily Ragas of the North.

5.3. And, Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar, who followed Vekatamakhin’s classification of Mela Ragas, in his youth, lived in Varanasi for about seven years and learnt Dhrupad singing. He brought in the shades of Uttaradi-samgita in some of his Kritis, in his own unique and original manner without compromising pristine Music [e.g. Hamir Kalyani (Kedar), Hindolam (Malkauns), Dvijavanti (Jaijaivanti), Yamuna-kalyani (Yaman) and Brindavana Saranga.]

Gharana-s

6.1. As regards the North Indian music, it was, at that stage, had almost parted with the traditional theories of Music. And, it had come to be regarded more as collection of individual entities than as an organized system of Ragas. Their Ragas were known by the times and seasons they should be performed; their character; magical properties, etc.

6.2. Further, after the disintegration of the Muslim empire the political structure of North India fragmented into numerous small states ruled by Nawabs and Maharajas. Each ruler competed with his rival in studding his court with famed musicians. It is said, rulers of some states borrowed heavily to get hold of top-notch performers. Each ruler was keen to establish the superiority of the Music of his court over that of others. Each would goad his musicians to come up with different styles and techniques of singing, such as: Taans, Murkis, Layakaari, Tayaari, and so on.

The Music across North India, thus, came to be stratified into styles of various court-music. Each was known as a Gharana (‘family’ or ‘house’), named after its patron (such as: Gwalior Gharana, Patiala Gharana, Jaipur Gharana and so on) . Each ruler desired to have his very own personalized Gharana of music. And if no particular geographical region could be identified then a Gharana would take the name of the founder; as for instance: Imdadkhani Gharānā named after the great Imdad Khan (1848 -1920) who served in the Royal Courts of Mysore and Indore.

A Gharana, in due course, turned into a symbol of social standing, affluence and power among the rulers .

6.3. The proliferation of Gharanas gave raise to bewildering styles of singing. Further, there was no exchange of ideas among the Gharanas, because of the element of competition among their patrons. Each Gharana guarded its technique as a secret; and each turned into an island. Performing to please the patron had taken priority; and, the theoretical aspects were left far behind. Music had become a practical craft. Attempts at standardization did not begin until the twentieth century when Pandit V. N. Bhatkhande worked out a system of classification.

Pandit Bhatkhande’s efforts

7.1. Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860-1936), a scholar and a musicologist, in his colossal work ‘Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati’ reorganized the Uttaradi or North Indian Music, mainly, by adopting the concept of Mela (grouping derived Ragas under a principal Raga) system as expanded by Venkatamakhin (1660) in the Appendix to his Chatur-dandi-prakashika.

[Venkatamakhin classified the Ragas according to the system of 72 basic scales (Mela)].

Bhatkhande also adopted the idea of Lakshana-geetas that Venkatamakhin employed to describe the characteristics of a Raga. Bhatkhande arranged all the Ragas of the Uttaradi Samgita into ten basic groups called ‘Thaat’, based on their musical scales. The Thaat arrangement, which is an important contribution to Indian musical theory, broadly corresponds with the Mela-karta system of Dakshinadi samgita.

Rapprochement

8.1. Thus, after the early parts of the 20th century, there began a growing realisation that though the two systems differ from each other in their peculiar and characteristic treatment of Ragas, their fundamental principles are similar. At the same time, the differences in their style of presentation were recognized and given due credit.

Karnataka Music generally begins in Madhyama-kaala (medium tempo) while the Hindustani begins in Vilamba-kaala (slow tempo). The techniques of Alamkara (ornamentation), Gamaka-s and Jaaru (slides) also differ.

The classification of Ragas in the two systems under the Melakartas (the major category) does indeed differ. And yet; certain Ragas of one system correspond to a certain Raga of the other system, though their names differ. For instance; Shubha Pantuvarali, Hindola, Abheri and Mohana of Karnataka Music correspond to Thodi, Malkaunss, Bhimplas and Bhupali of the Hindustani music.

There are plenty more such Ragas that are common to both the systems. Further, there also pairs of Ragas that have the same/similar set of notes (svara-sthana) but slightly differ from one another.

[ Raga Pravaham is a monumental work; and reference source of immense value, is an Index of about 5,000 Karnataka Ragas compiled by Dr. Dhandapani and D. Pattammal. The list of ragas is given both alphabetically and Mela karta wise. The different kramas for the same Ragas and same scales with different names are also listed.

The Mela-karta Ragas, Janya ragas, Vrja and Vakra Ragas and their derivatives , together with their structures, have been Indexed.

In addition, the Raga Pravaham also lists about 140 Hindustani Ragas allied or equivalent to Karnataka Ragas (pages 277-280 )

A Mela-karta-raga is a Sampurna-Raga (with all seven Svaras) where the ascent (arohana) and descent (avarohana) are in the same (reverse) order e.g. Sankarabharana

The Varja-Ragas are formed by leaving out either in arohana or avarohana or both, one or more Svaras; but keeping the other Svaras unchanged e.g. Hindola, Arabhi, Saramati.

The Vakra–Ragas are formed when the order (Krama) of the Svaras are changed; e.g. Ritigoula ( in addition one or more Svaras may be left out.]

![]()

Coming close again

9.1. Some distinguished Rāgas (Kāpi, Deś etc.,) of the Karnataka Samgita seem to have come from other regions during Maratha rule; and, are hence referred to as Deśīya.

The Ragas having similar structure, which developed independently in the Karnatak and Hindustani music traditions, have now been coming closer , tending to influence each other .

Thus, the majestic Darbāri Kāṇaḍa — associated with Tansen in Akbar’s court—has influenced the Southern rendering (the Dhaivata note) of the moving Kāṇaḍa. With the Carnatic composers and Hindustani musicians popularizing once exclusive Rāgas across the North-South divide, the homogenizing process received a huge boost.

9.2 In the latter half of the 20th century the music of the North and the South did come closer, with the musicians of either branch trying to understand the approach and the idioms of the other.

On the performance stage, Ustads , Pandits and Vidwans began singing and playing together (Jugalbandi) the Ragas common to both; Tabla virtuoso played alongside Mridanga artistes. Now, ragas such as Hamsadhvani, Abhogi and Kiravani became as much Hindustani as they were Karnataka.

9.3. The barriers are thus breaking down and there is a greater awareness among the musicians of today that the music of India is one; and, that two branches that originated from a common stock are indeed the two facets or modes of expressions of an integrated, fundamental Music tradition of India. And, that the Hindustani and Karnataka systems are but the two classical styles based on a common grammar but with different approaches and modes of expression. It is just their approach, techniques and Mano-dharma that have branched out.

9.4. It is good that the two styles have not attempted to merge into one; because, each enjoys its unique flavour, charm and brilliance. And, it is good that there is a growing mutual respect and appreciation of each other’s genius. The two are indeed variations of the same system and not two different systems altogether.

Continued in Part Three

…. Overview (3) – continued

Sources and References

The Rāgs of North Indian Music: Their Structure and Evolution by Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy

Indian Music: History and Structure by Emmie Te Nijenhuis’

The Music of India by Reginald Massey, Jamila Massey

History of Hindustani Classical Music WWW.itcsra.org

Origins of Indian Music – The medieval period http://carnatica.net/origin.htm’

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC

http://kushanmusic.blogspot.in/2012/02/brief-history-of-indian-music.html

All IMAGES ARE FROM INTERNET

Bhagvatiprasad Gandharva

August 1, 2019 at 7:33 am

Thanks for sharing. Do visit my site for more forms of classical music.

sreenivasaraos

August 2, 2019 at 1:39 am

Dear Shri Bhagvatiprasad

Thanks for the visit; and, for the invitation

Regards

sreenivasaraos

September 9, 2020 at 1:31 pm

Dear Shri Bhagvatiprasad Sir

I shall be thankful if you can kindly go through the following two articles related to Dhrupad;

and, let me know.

Thank you again Sir

goleshivani

April 8, 2021 at 1:24 pm

Aiyoooo! This is such beauty. I stumbled across this blog today and so blessed that I have since I’m finding sources to read on ICM. Great work and maybe market more so that people will easily know about this. 🙂

sreenivasaraos

April 21, 2021 at 1:59 am

Dear Shivani

You are welcome

I am glad you read this

Keep reading

Cheers and Regards