Artha-Tatparya-Shakthi

A. Artha

As mentioned at the commencement of Part One – The most common Sanskrit term for ‘meaning’ is Artha. Various expressions in English language, such as ‘sense’, ‘reference’, ‘denotation’, ‘connotation’, ‘designatum’ and ‘intention’, have been used to render that Sanskrit term. However, each of those English terms carries its own connotation; and, no single term adequately and comprehensively conveys the various shades of meanings associated with the idea of Artha.

Apart from ‘meaning’, there are at least twenty other connotations to the word Artha; such as : thing; object; purpose; target; extent; interest; property; wealth; polity; privacy; referent; and so on.

*

The term Artha figures in Vedic texts too. But, there, it is used in the sense of: aim; purpose; objective; enterprise; or, work. Here, Artha does not explicitly denote ‘meaning’. But, that basic idea is carried into the later texts where the term ‘Vakya-artha’ generally stands for: ’ the purpose of the sentence or the action denoted by the sentence’.

Yaska, the etymologist of the very ancient India, derives the term Artha from two roots (chakarita): Artho’rtem and Aranastha va – (artho.arter.araṇastho.vā -1,18) ‘ to go, to move towards, reach etc’ and Arna+shta ‘to stay apart ‘. The Artha is, thus, derived from roots conveying mutually opposite sense. It is said; Artha, according to this derivation, at once, denotes something that people are moving towards (Arteh) or something from which they desire to move away (Aranastha).

Some other scholars point out that in Sanskrit, the term ‘Artha’ has no clear derivation from the verb. But, the term itself gives rise to another verb ‘Arthayate’, which means ‘to request, to beg; to strive or to obtain’.

In any event, Artha has been in use as an all-embracing term having a verity of hues and shades of meanings. Almost everything that is understood from a word on the basis of some kind of ‘significance’ is covered by ‘Artha’.

It brings into its fold various other terms and expressions such as: ‘Tatparya’ (the true intent or gist); Abhi-praya (to intend or to approach); ‘Abhi-daha’ (to express or to denote); or,’Uddishya’ (to point out or to signify or to refer); ‘Vivaksa’ (intention or what one wishes to express); ‘Sakthi’ (power of expression); ‘Vakyartha’ (the import of the sentence); ‘Vachya’ and ‘Abhideya’ (both meaning : what is intended to be expressed); ’Padartha’ (the object of the expression); ‘Vishaya’ (subject matter);’Abidha’ (direct or literal meaning of a term) which is in contrast to lakshana the symbolic sign or metaphoric meaning; and, ‘Vyanjana’ (suggested meaning ) and so on .

But, in the common usage, Artha, basically, refers to the notion of ‘meaning’ in its widest sense. But, Artha is also used to denote an object or an object signified by a word.

The scope of the term Artha in Sanskrit is not limited to its linguistic sense or to what is usually understood by the word employed. It can be the meaning of the words, sentences and scriptures as well as of the non-linguistic signs and gestures. Its meaning ranges from a real object in the external world referred to by a word to a mere concept of an object which may or may not correspond to anything in the external world.

It could also mean Artha (money), the source of all Anartha (troubles); and Anartha could also be nonsense. Artha is one of the pursuits of life – wealth or well being. Artha could also signify economic power and polity. It is said that a virtuous person gives up Svartha (self-interest) for Parartha (for the sake of others). And, finally, Paramartha is the ultimate objective or the innermost truth.

Padartha

The communication of meaning is the main function of words (Pada); and in that sense, Artha is used in various places. In numerous contexts, Artha denotes the aim, purpose, goal or the object of the spoken word (pada). But, at the same time, it also involves other meanings such as –‘the object’ and/or to signify a certain tangible ’object’, ‘purpose or goal’ which could be attained. It is said; Padāt (lit., from word) suggests that every word has the capability to represent a certain object or multiple objects or purposes.

Thus, Padartha (pada+artha) stands for the meaning of the word; for a tangible object (Vastumatra); as also for the meaning (padartha) that is intended to be signified by the word (Abhideya). It is difficult to find an exact English equivalent to Padartha; perhaps category could be its nearest term.

It is argued that each word (Pada) has countless objects; and therefore, Padartha too is countless. It is said; the whole range of Padartha-s could be categorized into two: Bhava-padartha and Abhava-padartha. For instance; the whole of universe is categorized into Sat (existent) and A-sat (nonexistent); Purusha and Prakrti as in Samkhya

Nyaya Darshana (metaphysics) recognizes and categorizes as many as sixteen Padartha-s, elements:

- Pramāṇa (valid means of knowledge);

- Prameya (objects of valid knowledge);

- Saṁśaya (doubt);

- Prayojana (objective or the aim);

- Dṛṣṭānta (instances or examples);

- Siddhānta (conclusion);

- Avayava (members or elements of syllogism);

- Tarka (hypothetical reasoning):

- Nirṇaya (derivation or settlement);

- Vāda (discussion)

- Jalpa (wrangling);

- Vitaṇḍā (quibbling);

- Hetvābhāsa (fallacy);

- Chala (hair-splitting);

- jāti (sophisticated refutation) ;and

- Nigrahasthāna (getting close to defeat).

For a detailed discussion on these elements – please click here

*

According to one interpretation, the word itself is also a part of the meaning it signifies. Such a concept of ‘meaning’ is not found in the western semantics. For instance; the Grammarian Patanjali says: ’when a word is pronounced, an Artha ‘object’ is understood. For example; ‘bring a bull’, ‘eat yogurt’ etc. It is the Artha that is brought in; and it is also Artha that is eaten.

[Sabdeno-uccharitena-artha gamyate gam anya dadhya asana iti / Artha anyate Arthas cha Bhujyate]

Here, the term Artha stands for a tangible object which could be brought in or eaten; and, it is not just a notion. A similar connotation of Artha (as object) is also employed by Nyaya and Mimamsa schools. According to these Schools, the qualities, relations etc associated with the objects are as real as the objects themselves.

Bhartrhari also says that word is an indicator; even when a word expresses reality; it is not expressed in its own form. Often, what is expressed by a word is its properties rather than its form.

There are elaborate discussions on the issues closely related to the concept of understanding. It is argued; no matter whether the things are real or otherwise, people do have ideas and concepts of many things in life. In all such cases, it is essential that people understand those things and be aware of their meaning. Such meanings or the content of a person’s understanding are invariably derived from the language employed by each one.

That gives raise to arguments on questions such as: whether the meaning (Artha) of a word is derived from its function to signify (Vrtti); or through inference derived by the listener (Anumana) from the words he listned ; or through his presumption (Arthapatti) or imagination.

Grammarians assert that Artha (meaning) as cognized from a word is only a conceptual entity (bauddha-artha). The word might suggest a real object; but, its meaning is only what is projected by the mind (buddhi-prathibhasha) and how it is grasped.

Pundit Gadadharabhatta of the Navya (new) Nyaya School, in his Vyutpattivada, argues that a word is closely linked to the function associated with it. According to him, the term Artha stands for object or content of a verbal cognition (Sabda-bodha-vishaya) which results from understanding of a word (sabda-jnana) as derived from the significance of the function (vrtti) pertaining to that word (pada-nists-vritti-jnana) – Vritya-pada-pratipadya evartha ity abhidayate.

[According to him:

:- If a word is understood through its primary function (shakthi or aphids-vrtti or mukhya -vrtti) then such derived primary meaning is called sakyarta or vachyartha or abhidheya.

:- If a word is understood on the basis of its secondary function (lakshana-vrtti or guna-vrtti) then such derived secondary meaning is called lakshyartha

:- If a word is understood on the basis of its suggestive function (vyanjana-vrtti) then such derived suggested meaning is called vyanjanartha or dhvani-artha.

:- And, if a word is understood on the basis of its intellectual significance (tatparya-artha) then such derived intended meaning is called tatparyartha.

However, Prof. M M Deshpande adds a word of caution: Not all the Schools of Indian Philosophy of Grammar accept the above classification , although these seem to be the general explanations ]

**

Punyaraja, a commentator of Vakyapadiya of Bhartrhari, detailing the technical and non-technical aspects of the term Artha offers as many as eighteen explanations.

[ Artho asta-dashaad / tatra vastu-matram abhideyash cha / abhidheyo api dvidha shastriya laukika cha /.. ]

According to Punyaraja, Artha stands for an external real object (Vastu-matra) as also for the meaning intended to be signified by a word (Abhideya). The latter – meaning in linguistic sense – could be technical (Shastriya) of special reference or it could be the meaning as commonly grasped by people in a conversation (laukika). In either case, there are further differences. The meaning of a word might or might not be literary; and, it could also stand for an expression or a figure of speech (Abhideya). It could also be used to denote something that is not really intended (Nantariyaka) when something else is actually intended.

Bhartrhari also talks of two kinds of meanings – apoddhara-padartha and sthitha-lakshana-padartha. The latter refers to the meaning as it is actually understood in a conversation. Its meaning is fixed; and, Grammarians cannot alter it abruptly. Bhartrhari also said: here, meaning does not leave the word. Meaning is comprehended by the word itself. The word is eternal and resides within us.

[There was much discussion in the olden days whether a word has a fixed meaning or a floating one. For instance; the Grammarian Patanjali asserted that a word is spoken; and when spoken it brings about the understanding of its meaning. The spoken word is the manifestation of the fixed (dhruva, kutastha) meaning of the word. And, the word (sabda) and its meaning (artha) and their inter-relations (sambandha) are eternal (nitya) – Siddhe sabda-artha-sambandhe–Patanjali Mbh.1.27. ]

The former, apoddhara-padartha mentioned by Bhartrhari, tries to bring out the abstract or hidden meaning that is extracted from the peculiar use of the word in a given context. In many cases, such abstracted meaning might not denote the actual (linguistic) meaning of the term as it is usually understood. But, such usage does not represent the real nature of the language. The apoddhara-padartha is of some relevance only in technical or theoretical (Shastriya) sense, serving a particular or special purpose. That again, depends on the context in which the term in question is employed.

[In many of these discussions, it is difficult to draw a clear distinction between the literal meaning and the concept it represents (Pratyaya).

In the Sanskrit texts, the terms such as ‘Sabda’ (word); ‘Artha’ (object); ‘Pratyaya’ (concept) are horribly mixed up and are used interchangeably.]

*

There is also a line of discussion on whether Artha is universal or the particular? The Grammarian Vyadi says that the words refer to Dravya (substance) , that is , the particular. Another Grammarian Vajapyayana on the other hand argues that words, including proper names, refer to Jati or class or universal.

Panini seems to leave the question open-ended.

But, Kumarilabhatta of the Mimamsa School argues when we utter a word we are at once referring to at least seven characteristics (Vastuni) associated with it. Let’s say when one utter ‘Bull’ (Gauh) , that expression points to : Jati the whole class ; Vyakti – individual or particular; Sambandha– the relation between the two; Samudha– the collection of such elements; Linga-gender; Karaka- the relation that the term has with the verb (kriya-pada) or activity associated with it; and Samkhya– number , singular or plural.

With regard to the nature of the meaning of a word, Bhartrhari speaks in terms of its general or universal (jati) and its relative or specific (vyakti) connotations. Bhartrhari says that every word first of all means the class (jati) of that word. For instance; the word ‘cow’ initially refers to the general class of all that is in the form of cow. Later, it is implied to refer to its particular form (vyakti) . Thus, what is universal is then diversified into relative or a particular form. Bhartrhari then extends his hypothesis to the field of philosophy- Advaita. He says; the universal (Brahman) appears as relative or specific limited. It is ultimately the Brahman (Sabdatattva) that is at the root of all the words and their meaning (Artha) .

The Problem of Multiple Meanings

Generally, the notion of meaning is stratified into three or four types. The first is the primary meaning. If this is inappropriate in the given context, then one moves to a secondary meaning. Beyond this is the suggested meaning, which may or may not be the same as the meaning intended by the speaker. Specific conditions under which these different varieties are understood are discussed by the Schools of Grammar.

Bhartrhari points out that a word can carry multiple meanings; and that the Grammarian should explain, in some way, how only one of those meanings is conveyed at a time or is apt in a given context.

According to him, the process of understanding the particular meaning of a word has three aspects: first, a word has an intrinsic power to convey one or more meanings (abhidha); second, it is the intention of the speaker which determines the particular meaning to be conveyed (abhisamdhana) in a given context; and third, the actual application (viniyoga) of the word and its utterance.

In the case of words carrying multiple meanings, the meaning which is in common usage (prasiddhi) is considered by Bhartrhari as its primary meaning. The secondary meaning of a word normally requires a context for its understanding. Usually, the secondary meaning of a word is implied when the word is used for an object other than it normally denotes, as for example, the metaphorical use of the word.

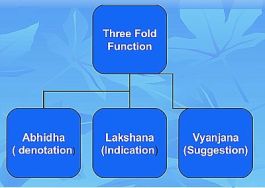

Now, according to Indian Poetics, a word has three functions: it signifies or denotes (abhida); it indicates (lakshana); and it suggests (vyanjana).

The meaning that is comprehended immediately after the word is uttered is its primary meaning (mukhya-artha). The meaning thus conveyed and its relation to the next word and its own meaning is a mutual relation of the signifier and the signified (vachya-vachaka). The power that creates the relation among words is Abhida-vyapara, the power of denotation or sense. The suggestive power of the word is through Vyanjana-artha.

The meaning of a word or a sentence that is directly grasped in the usual manner is Vakyartha (denotation or literal sense); and, the power of the language which conveys such meaning is called Abidha-vritti (designating function). It is the principal function of the word .The primary sense Vakyartha is the natural (Svabhavokti) and is the easily comprehended sense of the word.

In certain cases where a particular word is not capable of conveying the desired sense, another power which modifies that word to produce the fitting or suitable meaning is called Lakshana-vritti (indicative function). Such secondary sense (lakshana) could even be called an unnatural meaning (Vakrokti) of the word.

**

There are certain other peculiar situations:

There is the complicated question of words having similar spelling; but having different pronunciations and conveying different meanings (homograph). Such words have been the concern of Grammarian from ancient times onwards. Some argue such cases should, technically, be treated as different words with similar pronunciation and similar meaning. But, some Grammarians point out that there are, in fact, no true Homonyms. They do differ, at least slightly, either in the way they are pronounced or their usage or relevance.

[If someone says saindhavam anaya, it might mean the ‘bringing of a horse’ or ‘bringing salt’. The exact meaning of the term saindhava is to be determined according to the intention of the speaker uttered in a given context,]

There is also the issue of Dyotya-artha (co-signified) as when two entities are jointly referred by using the conjunctive term such as ‘and’ or ‘or’ (cha; Va). It is said; the particles such as ‘and’, ‘or’ do not, by themselves, carry any sense if they are used independently. They acquire some context and significance only when they are able to combine (samuchchaya) two or more entities of the similar character or of dissimilar characters.

Artha in art

The concept of Artha also appears in the theories of Art-appreciation. There, the understanding of art is said to be through two distinctive processes – Sakshartha, the direct visual appreciation of the art-work; and, Paroksharta, delving into its inner or hidden meanings or realms (guhyeshu-varteshu). The one concerns the appreciation of the appealing form (rupa) of the art object (vastu); and, the other the enjoyment of the emotion or the essence (rasa) of its aesthetic principle (guna vishesha). Artha, in the context of art, is, thus, essentially the objective and property of art-work; as also the proper, deep subjective aesthetic art-experience.

In the traditions of Indian art, the artist uses artistic forms and techniques to embody an idea, a vision; and, it is the cultured viewer with an understanding heart (sah-hrudaya), the aesthete (rasika) that partakes that vision.

It is said; an artistic creation is not a mere inert object, but it is truly rich in meaning (Artha). And, it is capable of evoking manifold emotions , transforming the aesthete. As for a connoisseur , it is not only a source of beauty; but is also an invitation to explore and enjoy the reason (Artha) of that beauty. Thus, Artha, understood in its wider sense as experience, is the dynamic process of art-enjoyment that bridges the art-object and the connoisseur.

Artha in Arthashastra

In the Arthashastra ascribed to Kautilya, the term Artha means more than ‘wealth’ or ‘material well being’ that follows the Dharma. There are numerous interpretations of Artha in the context of Kautilya’s work.

Here, Artha is an all-embracing term having a verity of meanings. It includes many shades and hues of the term : material well-being of the people and the State (AS:15.1.1); economy and livelihood of the people ; economic efficiency of the State in all fields of activity including agriculture and commerce(AS:1.4.3) . It also includes Rajanithi; the ‘politics’; and the management of the State. Artha, here, is the art of governance in its widest sense.

But, all those varied meanings aim at a common goal; have faith in the same doctrine; and, their authority is equal or well balanced. The purpose of life was believed to be, four-fold, viz. the pursuit of prosperity, of pleasure and attainment of liberation (Artha, Kama, Moksha); all in accordance with the Dharma prescribed for each stage of life.

That is because; there is a fear that the immoderate pursuit of material advantage would lead to undesirable and ruinous excesses. And therefore, Artha must always be regulated by the superior aim of Dharma, or righteousness.

*

To start with, Artha is interpreted as sustenance, employment or livelihood (Vrtti) of earth-inhabitants. It also is said to refer to means of acquisition and protection of earth.

[manuṣyāṇāṃ vṛttir arthaḥ, manuṣyavatī bhūmir ity arthaḥ //–KAZ15.1.01]

Artha is also taken to mean material well-being or wealth. It is one of the goals in human life. Here, it is with reference to the individual, his well being and his prosperity in life. That perhaps is the reason Artha, in the text, is taken as Vrtti or sustenance or occupation or means of livelihood of people (Manushyanam Vrtti).

It is said; such Vrtti was primarily related to the three-fold means of livelihood – agriculture; animal husbandry and trade – through which men generally earn a living.

*

Arthashatra is also concerned with the general well-being of the earth and its inhabitants. And, since the State is directly charged with the responsibility of acquiring, protecting and managing the territory and its subjects, the Arthashastra necessarily deals with statecraft, economy and defence of the land and its people.

In the older references, Arthashastra is described as the science of politics and administration. But, in the later times, it came to be referred to as Danda– Nitishastra or Rajaniti -shastra / Raja -dharma.

But Arthashastra is more comprehensive. It includes all those aspects and more.

In the concluding section of his work, Kautilya says ‘the source of livelihood of the people is wealth’. Here, the wealth of the nation is both the territory of the Sate and its inhabitants who follow a variety of occupations (AS: 15.1.1). The State or the Government has a crucial responsibility in ensuring the stability and the material wellbeing of the nation as a whole as also of its individual citizens. Therefore, an important aspect of Arthashastra is the ‘science of economics’, which includes starting of productive ventures, taxation, revenue collection and distribution, budgets and accounts.

The ruler’s responsibilities in the internal administration of the State are threefold: raksha, protection of the Sate from external aggression; Palana, maintenance of law and order within the State; and, Yogakshema, safeguarding the welfare of the people and their future generations – tasyāḥ pṛthivyā lābha.pālana.upāyaḥ śāstram artha.śāstram iti /.

Kautilya cautions that a judicious balance has to be maintained between the welfare and comfort of the people on one hand and augmenting the resources of the State on the other through taxes, levies , cess etc. The arrangement for ensuring this objective presupposes – maintenance of law and order and adequate, capable , transparent administrative machinery.

It is also said that the statecraft, which maintains the general social order should take adequate measures to prevent anarchy.

Apart from ensuring collection of revenue there have also laws to avoid losses to the State and to prevent abuse of power and embezzlement by the employees of the State. These measures call for enforcement of laws (Dandanithi) by means of fines, punishments etc. The Tax payers as also the employees of the state machinery are subject to Dandanithi.

The king was believed to be responsible as much for the correct conduct (achara) of his subjects, and their performing the prescribed rites of expiation (prayaschitta) as for punishing them, when they violated the right of property or committed a crime. The achara and prayaschitta sections of the smrti cannot accordingly be put outside the “secular ” law.

Arthashatra prescribes how the ruler should protect his territory. This aspect of protection (Palana) covers principally, acquisition of territory, its defence, relationship with similar other/rival rulers (foreign-policy), and management of state-economy and administration of state machinery.

Since the safety of the State and its people from aggression by rival states or enemies is of great importance, the King will also have to know how to deal with other Kings using all the four methods (Sama, Dana, Bedha and Danda) ; that is, by friendly negotiations; by strategies ; as also by war-like deterrents. Thus, to maintain an army and be in preparedness becomes an integral part of ‘science of economics’, the Arthashastra.

**

[Prof. Hermann Kulke and Prof. Dietmar Rothermund in their A History of India (Rutledge, London, Third Edition 1998-Page61) write:

The central idea of Kautalya’s precept (shastra) was the prosperity (Artha) of king and country. The king who strove for victory (vijigishu) was at the centre of a circle of states (Mandala) in which the neighbor was the natural enemy (Ari) and the more distant neighbor of this neighbor (enemy of the enemy) was the natural friend (Mitra). ..

The main aim of the Arthashastra was to instruct the king on how to improve the qualities of these power factors; and, to weaken those of his enemy even before an open confrontation took place. He was told to strengthen his fortifications, extend facilities for irrigation, encourage trade, cultivate wasteland, open mines, look after the forest and build enclosures for elephants and, of course, try to prevent the enemy from doing likewise. For this purpose he was to send spies and secret agents into his enemy’s kingdom. The very detailed instructions for such spies and agents, which Kautalya gives with great psychological insight into the weakness of human nature, have earned him the doubtful reputation of having even surpassed Machiavelli’s cunning advice in Il Principe.

But actually Kautalya paid less attention to clandestine activities in the enemy’s territory than to the elimination of ‘thorns’ in the king’s own country.

Since Kautalya believed that political power was a direct function of economic prosperity, his treatise contained detailed information on the improvement of the economy by state intervention in all spheres of activity, including mining, trade, crafts and agriculture. He also outlined the structure of royal administration and set a salary scale starting with 48,000 Panas for the royal high priest, down to 60 Panas for a petty inspector.

All this gives the impression of a very efficiently administered centralized state which appropriated as much of the surplus produced in the country as possible. There were no moral limits to this exploitation but there were limits of political feasibility. It was recognized that high taxes and forced labour would drive the population into the arms of the enemy and, therefore, the king had to consider the welfare and contentment of his people as a necessary political requirement for his own success. ]

B.Tatparya or intention

Tatparya [lit. the about which; Tat (that) +Para (object of intension)] is described as the intention or the desire of the speaker (vak-turiccha); and also as the gist, the substance or the purport of the meaning intended to be conveyed by the speaker. The context plays a very important role in gathering the apt or the correct Tatparya of an utterance (sabdabodha) or a sentence in a text. The contextual factors become particularly relevant when interpreting words or sentences that are ambiguous or carry more than one meaning.

It is said; in the case of metaphors or the figures-of- speech, the intended meaning (Tatparya) is gathered not by taking the literal meaning of each of its individual words but by grasping the overall intention of the expression in the given context (sabda-bodha).

The Mimamamsa and Nyaya Schools which take the sentence to be a sequence of words, relay on Tatparya to explain how the relevant meaning is obtained from a collection of words having mutual relation. Each word in a sentence carries its own meaning; but a string of unconnected isolated words cannot produce a unified meaning. Tatparya, broadly, is the underlying idea or the intention of a homogeneously knit sentence, in a particular context, that is required to be understood.

The Mimamsa lays down a framework for understanding the correct meaning of a sentence: denotation (Abhida) – purport (Tatparya) – indication (Lakshana), where by the power of denotation one comprehends the general idea of the sentence; by the power of purport one understands its special or apt sense; and, by the power of indication one grasps the suggested meaning (Dhvani) of the sentence.

According to The Encyclopaedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 5: The Philosophy of the Grammarians edited by Harold G. Coward and K. Kunjunni Raja ; the meaning of a sentence can be considered from two standpoints: from that of the speaker and from that of the listener. The general approach of the West has been from the speaker’s point of view. The Indian approach has been mainly from the listener’s point of view.

In a normal speech situation there can be five different aspects of the meaning of an utterance: (1) what is in the mind of the speaker when he makes the utterance; (2) what the speaker wants the listener to understand; (3) what the utterance actually conveys ;(3) what the listener understands as the meaning of the utterance; and (5) what is in the mind of the listener on hearing the utterance.

In a perfect linguistic communication, all the five factors must correspond. But, due to various causes there are bound to be differences that might disturb a perfect communication.

Let’s say that when the speaker is uttering a lie, he clearly intends to misdirect the listener. Here, what is in the mind of the speaker is different from what is conveyed to the listener. Even otherwise, quite often what the listener understands as the meaning of the utterance might be different from what the speaker intends to convey. The problem could be caused either by the lack of expressive power of the speaker or the inability of the listener to understand; or it could be both.

Here, what is in the mind of the speaker before he speaks and what is in the mind of the listener after he hears are both intangible. They cannot be objectively ascertained with certainty. It is only what is said explicitly that can be objectively analyzed into components of syllables, words and sentences. It however does not mean that the other aspects or components of the entire body of communication are less important.

C. Shakthi (power of expression)

The power of word (sabda-shakthi) is that through which it expresses, indicates or suggests its intended meaning. The term Shakthi is also understood as the relation that exists between word (Sabda) and its meaning (Artha) – (sabda-artha-sambandha). This relation is considered to be permanent and stable.

The understanding of the relationship between word and its meaning is called vyutpatti. Salikanatha (Ca.8th century) , a Mimamsa philosopher belonging to the Prabhakra School , in his Prakarana-pancika lists eight means for such comprehension of the meaning of the words. They are:

- (i) grammar;

- (ii) comparison;

- (iii) dictionary;

- (iv) words of a trustworthy person;

- (v) action;

- (vi) connotation of the sentence;

- (vii) explanation; and,

- (viii) proximity of a word, the meaning of which is already established.

*

Shakthi is the primary relationship between a word and its meaning. Unless the listener recognizes or remembers their continuing relationship he cannot understand the purport (Tatparya) of a statement. Shakthi is therefore described as a Vrtti, a function which binds the word and meaning together in order to bring out a particular intended sense – (Vrtti-jnanadhina –pada-jnana-janya –smrti-vishaya)

It would have been ideal if every word had a single meaning; and every meaning had only one word. That would have helped to avoid plausible confusion and ambiguities. But, in all natural languages that are alive and growing, the words, often, do carry more than one meaning; and, a meaning can be put out in verity of words. Even the borders of the meanings are not always fixed. The meanings or various shades of meaning are context sensitive, depending on the context and usage.

There would be no problems if the meaning and intent of a sentence is direct and clear. But, if there are ambiguities, the direct–meaning of the sentence would become inconsistent with its true intent. It is here that the power of Shakthi comes into play.

The term Shakthi is often used for Vrtti or the function. Grammarians recognize various types of such Vrtti-s. Among those, the main Vrtti-s employed to explain the various types of meaning conveyed by speech are: Abhidana; Lakshana ; Gauni ; Tatparya ; Vyanjana ; Bhavakatva; and Bhojakatva.

Of these Vrtti-s or Shakthi-s, Lakshana which has the power of suggestion is considered most important. Three conditions for Lakshana are generally accepted by all schools. The first is the incompatibility or inconsistency of the primary meaning in the given context. Such inconsistency produced by the uncommon usage of the word will force a break in the flow of thought, compelling the listener to ponder over in his attempt to understand what the speaker meant; and, why he has used the word in an irregular way. Such inconsistency can either be because of the impossibility or of the unsuitability of associating the normal meaning of the word to context at hand.

The second condition is some kind of relation that exists between the primary (normal) meaning of the term and its meaning actually intended in the context. This relation can be one of proximity with the contrary or one of similarity or of common quality. The latter type is called Gauni Lakshana which the Mimamsakas treat as an independent function called Gauni. According to Mimamsakas, the real Lakshana is only of the first type, a relation of proximity with contrariety (oppositeness) .

The third condition is either acceptance by common usage or a special purpose intended for introducing the Lakshana. All faded metaphors (nirudha lakshana) fall into the former category; and , the metaphorical usages , especially by the poets , fall into the latter.

[Panini, however, did not accept Lakshana as a separate function in language. He did not consider the incompatibility etc on which the Lakshana was based by the Grammarians as quite relevant from the point of view of Grammar. The sentences such as: ‘he is an ass’ and ‘He is a boy ‘are both grammatically correct. His Grammar accounts for some of the popular examples of Lakshana; like ‘the village on the river’ (gangayam ghosah) by considering proximity as one of the meanings of the locative case. Similarly, Panini does not mention or provide for the condition of yogyata or consistency, which is considered by the later Grammarians as essential for unity of sentence. The expression Agnina sinchati (He sprinkles with fire) is grammatically correct, though from the semantic point of view it may not be quite proper, because sprinkling can be done only with liquid and not with fire.]

In the next part let’s look at the discussions on the relationship between the word (sabda) and meaning (Artha) are carried out by the Scholars of Indian Poetics (Kavya-shastra).

Continued in Part Three

Sources and References

- The Philosophy of the Grammarians, Volume 5; edited by Harold G. Coward, Karl H. Potter, K. Kunjunni Raja

- Tatparya and its role in verbal understanding by Raghunath Ghosh; University of North Bengal

- The Birth of Meaning in Hindu Thought by David B. Zilberman

- The Meaning of Nouns: Semantic Theory in Classical and Medieval India by M.M. Deshpande

- Routledge Encyclopaedia of Philosophy: Index edited by Edward Craig

- Hermeneutical Essays on Vedāntic Topics by John Geeverghese Arapura

- the Emergence of Semantics in Four Linguistic Traditions: Hebrew, Sanskrit…edited by Wout Jac. Van Bekkum

- 8 A Comparative History of World Philosophy: From the Upanishads to Kant by Ben-Ami Scharfstein

- Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Soundby Guy L. Beck

- Indian Philosophy: A Very ShortIntroduction by Sue Hamilton

- Culture and Consciousness: Literature Regainedby William S. Haney

- The Sphota Theory of Language: A Philosophical Analysisby Harold G. Coward

- Bhartr̥hari, Philosopher and Grammarian: Proceedings of the First International conference on Bharthari held at Pune in 1992 edited by Saroja Bhate, Johannes Bronkhorst

- Being and Meaning: Reality and Language in Bhartṛhari and Heideggerby Sebastian Alackapally

- Bhartṛhari, the Grammarianby Mulakaluri Srimannarayana Murti

- Word and Sentence, Two Perspectives: Bhartrhari and Wittgensteinedited by Sibajiban Bhattacharyya

- Kautilya’s Arthashastra by RP Kangale

- PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET