Continued from Part Six

[I could not arrange the topics in a sequential order (krama). You may take these as random collection of discussions; and, read it for whatever it is worth. Thank you.]

Indian poetics – Kavya Shastra

It is customary to begin the history of Indian poetics with Natyashastra. Out of its thirty six chapters, two chapters deal with Rasa-bhava (Ch 6 & 7) and Alamkara-guna (Ch 16). The other chapters touch upon related topics, such as: plot (Ch 19), genre (Ch 18, 20), meter (Ch 15). By and large, the text relates to dramaturgy in its practical applications. The aspects of Poetics that appear in the text , of course, are not directly related to Kavya. In Natyashastra, the nature of poetry as outlined in it is incidental to the discussions on Drama; and, it does not have an independent status.

[In Chapter sixteen of the Natyashastra, titled as kāvyalakṣaṇo nāma ṣoḍaśo’dhyāyaḥ , Bharata lists thirty-six of Kavya Lakshanas (features)

– ṣaṭtriṃśa-lakṣaṇānyeva kāvya-bandheṣu nirdiśet ॥ 16. 135॥

He calls them as Kavya Vibhushanam, the adornments which enhance the beauty of a Kavya (prabandha śobhākaraṇāni); and, together help in producing the Rasa – samyak prayojyāni rasāyanāni.

Etāni kāvyasya ca lakṣaṇāni/ ṣaṭtriṃśad uddeśa nidarśanāni । prabandha śobhākaraṇāni tajjñaiḥ / samyak prayojyāni rasāyanāni ॥ 16.172॥

But, Bharata neither illustrates these Lakshanas , nor does he specify how these are to be employed in a Kavya. He also does not try to differentiate the Lakshanas from the Alamkaras.

The renowned scholar Dr. V. Raghavan observes: By Lakshanas , Bharata refers to the features of the Kavya in general ; and, not necessarily of Drama alone. He also makes a rather ambiguous statement : Lakshana differs from Alamkara , in the sense that it is more comprehensive ; and, is also not a separate entity like the ornament . Lakshana belongs to the body of the Kavya . It is Aprathaksiddha ; it is the Kavyasarira itself. It is said; the Lakshana gives grace to Kavya; while, Alamkara is added to it for extra beauty. (Let me admit; I do not pretend to have understood this , entirely)

Dr. Raghavan also says; gradually , the Lakshana died in the Alamkara shastra. And , in the later times , some authors assigned the Lakshanas different names. For instance; Raja Bhoja and Saradatanaya call it as Bhushana; and, Jagaddhara calls it Natya-alamkara.

For more on Lakshanas , please click here]

**

The Indian poetics effectively takes off from Kavya-alamkara of Bhamaha (6th century) and Kavyadarsa ( 1, 2 and 3) of Dandin (7th century). There seems to be no trace of Kavya-s during the long centuries between Bharatha and Bhamaha. There are also no texts available on Kavya-shastra belonging to the period between the Natyashastra of Bharata and Bhamaha (6th century). Perhaps they were lost even as early as 6th century. The early phase of Indian Poetics, the Kavya-shastra, is represented by three Scholars Bhamaha, Dandin and Vamana.

The intervening period, perhaps, belonged to Prakrit. Not only was Prakrit used for the Edicts and the Prasastis, but it was also used in writing poetical and prose Kavyas. The inscriptions of Asoka (304–232 BCE) were in simple regional and sub-regional languages; and, not in ornate Kavya style. The inscriptions of Asoka show the existence of at least three dialects, the Eastern dialect of the capital which perhaps was the official lingua franca of the Empire, the North-western and the Western dialects.

By about the sixth or the Seventh century the principles of Poetics that Bharata talked about in his Natyashastra (first or second century BCE) had changed a great deal. Bharata had introduced the concept of Rasa in the context of Drama . He described Rasa by employing the analogy of taste or relish, as that which is relished (Rasayatiti Rasah) ; and , regarded Rasa as an essential aspect of a Dramatic performance. He said that no sense proceeds without Rasa (Na hi rasadrte kaschid- arthah pravartate). He did not, however, put forward any theories about the Rasa concept. He did not also elaborate much on Alamkaras, the figures of speech, which he mentioned as four: Upama, Dipaka, Rupaka and Yamaka. Later writers increased it vastly. Rajanaka Ruyyaka named as many as 82 Alamkaras.

As the concepts of Rasa and Alamkara were transferred to the region of Kavya, several questions were raised: why do we read any poetry? Why do we love to witness a Drama? What is it that we truly enjoy in them? What makes poetry distinctive as a form and what distinguishes good poetry from the bad? , and so on.

Ultimately, the answer could be that we love to read or listen to a poem, or see a Drama because doing so gives us pleasure; and, that pleasure is par excellence, unique in itself and cannot be explicitly defined or expressed in words.

But, unfolding of the Indian poetics or the study of the aesthetics of poetry came about in stages. Generally speaking, the development of Sanskrit literary theory is remarkably tardy, spread over several generation of scholars.

The Organized thinking about Kavya seems to have originated with the aim of providing the rules by which an aspiring writer could produce good Kavya.

***

Kavya–agama, the elements of Poetics

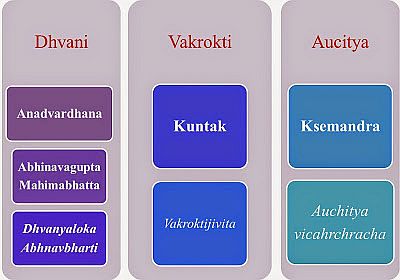

The Indian aesthetics takes a start from Natyashastra, winding its course through the presentations of Bhamaha, Dandin and Vamana; and , later gains vastness in writings of Anandavardhana, Abhinavagupta, Vishwanatha and Jagannatha Pandita.

These scholars are, generally, classified as originators of ideas; compilers and commentators.

Among the scholars , over the centuries, Bharatha, Bhamaha, Dandin ,Vamana , Anandavardhana and Kuntala could be called originators of poetic principles or elements.

The compilers were: Mammata, Vishwanatha and Jagannatha.

And among the commentators; Udbhata, Bhattaloa, Srismukha, Bhattanaya, Bhattatauta and Abhinavagupta are prominent.

Of the three scholars of the older School of Poetics – Bhamaha, Dandin and Vamana – Bhamaha (6th century) son of Rakrilagomin is the oldest ; and, is held in high esteem by the later scholars.

*

Books on Poetics have been written in three forms: in verse, in Sutra-form and in Karika.

Verses: Bharatha, Bhamaha, Dandin, Udbhata, Rudrata, Dhananjaya, Vagbhata I, Jayadeva , Appayya Dikshita and others

Sutra vritti: The principles and concepts are written in concise Sutra form. the explanations are followed in the commentary. Initially, Vamana and Ruyyaka adopted this form. Some others in the later times almost followed it: Vagbhatta II , Bhanumisra , Jagannatha et al.

Karika: In crisp verses or couplets. Anandavardhana, Kuntaka, Mammata, Hemachandra, Vishwanatha and others adopted Karika form. Their basic statements are in Karika , while their explanations are in prose.

Before we talk about the stages in the development of Indian Poetics let me mention, at the outset, the elements of Poetics in a summary form. Later we shall go through each stage or each School in fair detail.

The elements of Poetics or Kavya-agama are said to be ten:

- (1) Kavya-svarupa (nature of poetry); causes of poetry, definition of poetry, various classes of poetry and purpose of poetry;

- (2) Sabda-Shakthi, the significance of words and their power;

- (3) Dhvani-kavya , the poetry suggestive power is supreme ;

- (4) Gunibhuta-Vangmaya-kavya , the poetry where suggested (Dhvani) meaning is secondary to the primary sense;

- (5) Rasa: emotive content;

- (6) Guna: excellence of poetic expression ;

- (7) Riti ; style of poetry or diction;

- (8) Alamkara : figurative beauty of poetic expressions ;

- (9) Dosha ; blemishes in poetic expressions that need to be avoided; and ,

- (10) Natya-vidhana the dramatic effect or dramaturgy.

At times, the Nayaka-nayika-bheda the classification of the types of heroes and heroines is also mentioned; but, it could be clubbed either under Rasa or under Natya-vidhana.

Of these, we have already, earlier in the series, familiarized ourselves with the elements such as the causes, the definition, various classes as also the purposes of Kavya. We have also talked about Sabda (word) and Artha (Meaning) as also the concepts of Dhvani and Rasa. We shall in the following paragraphs talk about the other elements of Kavya such as Alamkara, Guna/ Dosha, Riti, Dhvani , Vakrokti Auchitya, etc.

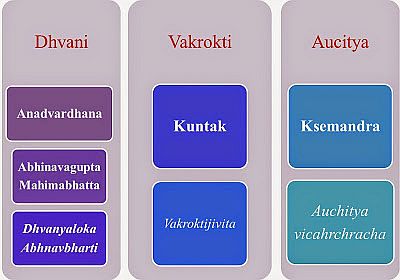

Then again, the whole of Poetics broadly developed into eight Schools: Rasa, Alamkara, Riti, Guna/Dosha, Vakrokti, Svabhavokti, Auchitya and Dhvani.

We shall briefly talk about these elements a little later.

Although the concepts of Rasa and Alamkara could be traced back to more ancient periods, it was Bharata who applied those concepts to the theory and practice of Drama. In a similar manner, the notions of Riti and Guna were adopted into Bharata’s ideas of Guna and Dosha. He implied, although not explicitly, that the style (Vrtti) must be appropriate with the matter presented and with the prevailing mood of a particular situation.

Bharata’s notions of Guna (merit), Dosha (defect), Riti (style) or Vakrokti (oblique poetry or deviations) ,Savabhavokti (natural statements), Auchitya ( propriety) etc. were fully developed by the later scholars such as Bhamaha, Dandin , Vamana and Kuntaka , although each with slightly varied interpretations of the ideas suggested by Bharata.

Over the centuries , though many Schools (sampradaya) developed in the field of Indian poetics , each was not opposed to the others. Each Sampradaya propagated its own pet ways of poetry ; and, at the same time made use of the expressions of other schools as well. For instance; Bharata spoke , in particular , about Rasa; Bhamaha of Alamkara; Vamana of Riti; Anandavardhana of Dhvani; Kuntaka of Vakrokti; and Kshemendra of Auchitya (relevance). The later poets saw all of those as varied expressions of poetry that are not in conflict with each other. But , three things – Rasa , Guna and Alamkara – are accepted universally by poets of all schools.

(Source; Thanks to Sagar G.Ladhva )

But, let me give here an abstract in the words of Prof. Mohit Kumar Ray ( as given in his A Comparative Study of the Indian Poetics and the Western Poetics )

To sum up; all theorists agree that the language of poetry is different from the language of prose. They also agree that sound and sense are the two main elements of poetry; and that poetry is born when they are blended harmoniously together. The varied speculations are about how this blending can be brought about, leading to different schools : Alamkara, Riti, Svabhavokti, Dhvani, Vakrokti etc

But, neither Alamkara nor Riti nor Vakrokti etc by itself, individually, accounts for poesies of a poem. An Alamkara cannot be super-added. It must be integral to the poem. Similarly, a particular style, all by itself, cannot make a Kavya. It must be in keeping with the cultural level of the poet and the reader as also with the nature of the thought-content of the poem. There are various factors that go to determine the style.

Again, a deviation or stating a thing an oblique way cannot make a Kavya. What is stated should be in harmony with the predominant passion or Rasa of the work.

In other words, the production of Rasa demands the use of all or some of the elements of the poetics depending upon the appropriateness or the nature of the idea envisioned in the Kavya; because, a Kavya is an organic unity. We must have suggestion, we may have elegant figures of speech or deviation also ; we may even have an attractive unique style and so on . But all these elements must be integrated into the matrix of the Kavya.

What is poetry if it does not produce Rasa or give the reader an experience of aesthetic delight?

The Indian Poetics

Rasa

Of the various poetic Schools, chronologically, Rasa is taken as the oldest because it is discussed in Natyashastra, where, Rasa meant aesthetic appreciation or joy that the spectator experiences . As Bharata says , Rasa should be relished as an emotional or intellectual experience :

Na rasanāvyāpāra āsvādanam,api tu mānasa eva (NS.6,31) .

The Nāṭyashāstra asserts that the goal of any art form is to invoke such Rasa.

Bharata’s theory of Rasa was crafted mainly in the context of the Drama. He was focused on the dancer’s or actor’s performance ; and , the effort needed to convey her/his own experiences to the spectator , in order to create aesthetic appreciation or enjoyment of the art in the heart and mind of the spectator.

Bharata elaborated the process of producing Rasa in terms of eight Sthayi Bhavas , the principle emotional state expressed with the aid of Vibhava (the cause) and Anubhava (the enactment); thirty-three Vyabhicāri (Sanchari) bhāvās, the transient emotions; and, eight Sattivikbhavas , the involuntary physical reactions.

These various Bhavas involved expressions through words (Vachika), gestures (Angika) and other representations (Aharya), apart from involuntary body-reactions (Sattvika). Such elements employed to convey the psychological state of the character thus , in all , amounted to forty-nine or more .

The famous Rasa-sutra or basic “formula”, in the Nāṭyashāstra, for evoking Rasa, states that the vibhāva, anubhāva, and vyabhicāri bhāvas together produce Rasa :

tatra vibhāvā-anubhāva vyabhicāri saṃyogād rasa niṣpattiḥ ।

Thus, Bharata’s concept and derivation of Rasa was mainly in the context of the Drama. That concept – of the enjoyment by the recipient spectator- as also his views on the Gunas and Dosha that one must bear in mind while scripting and enacting the play , were later enlarged , transported and adopted into Kavya as well.

In the context of the Kavya, though Rasa is all pervasive, it has been enumerated separately, because Rasa, which came to be understood as the ultimate aesthetic delight experienced by the reader/listener/spectator, is regarded as the touch-stone of any creative art. Rasa has, therefore, been discussed in several layers – independently, as also in relation to other aspects of poetic beauty , such as : the number of Rasa, each type of Rasa, nature of aesthetic pleasure of each of type Rasa, importance of Rasa, its association with other Kavya-agamas and so on. Some accepted Rasa as Alamkara (Rasavath), while others regarded it as the soul or the essential spirit of any literary work.

Both in Drama and in Kavya, Rasa is not a mere means; but, it is the desired end or objective that is enjoyed by the Sahrudaya, the cultured spectator or the reader. In the later texts, the process of appreciation of Rasa became far more significant than the creation of Rasa. The poet-scholars like Bhamaha and his follower took to Rasa very enthusiastically. Later, Anandavardhana entwined the concept of Dhvani (suggestion) with Rasa.

Indian Aesthetics considers that among the various poetic theories (Kavya-agama), Rasa is of prime importance in Kavya. And, very involved discussions go into the ways and processes of producing Rasa, the ultimate aesthetic experience that delights the Sahrudaya, the connoisseurs of Kavya.

Again, what is poetry if it does not produce Rasa or give the reader an experience of aesthetic delight?

Rasa is therefore regarded as the cardinal principle of Indian aesthetics. The theory of Rasa (Rasa sutra) or the realization of Rasa (Rasa Siddhi) is discussed in almost all the works on Alamkara Shastra in one way or the other. The importance of the Rasa is highlighted in Alamkara Shastra, by calling it the Atman (the soul), Angin (the principle element), Pradhana-Pratipadya (main substance to be conveyed), Svarupadhyaka (that which makes a Kavya), and Alamkara ( ornamentation) etc.

Alamkara

Although Bharata , in his Natyashastra mentions four components of Alamakara (upamā rūpakaṃ caiva dīpakaṃ yamakaṃ) as related to Drama, he does not elaborate on it.

upamā rūpakaṃ caiva dīpakaṃ yamakaṃ tathā । alaṅkārāstu vijñeyā catvāro nāṭakāśrayāḥ ॥ NS.6. 41॥

The Alamkara School , therefore, is said to take off effectively from the works of Bhamaha and Dandin. It appears , the two scholars were not separated much either in time or in location; and yet, it is hard to ascertain whether they were contemporaries. But, they seemed to have lived during a common period (6th or 7th century) or the time-interval between the two was not much. But, it is difficult to say with certainty who was the elder of the two, although it is assumed that Bhamaha was earlier . Generally, it is believed that Bhamaha lived around the late sixth century while Dandin lived in the early seventh century.

It could be said that the early history of Sanskrit poetics started with the theory of Alamkara that was developed into a system by Bhamaha and later by Dandin. It is however fair to recognize that their elaborations were based in the summary treatment of poetics in the 16th chapter of Natyashastra. The merit of the contributions of Bhamaha and Dandin rests in the fact that they began serious discussion on Poetics as an independent investigation into the virtues of the diction, the language and Alamkara (embellishments) of Kavya; and, in their attempt to separate Kavya from Drama and explore its virtues.

[In their discussions, the term Alamkara stands for both the figurative speech and the Poetic principle (Alamkara), depending on the context. That is to say; in their works, the connotation of Alamkara as a principle of embellishment was rather fluid. Though Alamkara , as a concept, was the general name for Poetics, Alamkara also meant the specific figures of speech like Anuprasa, Upama etc. And, the concepts of Rasa, Guna, Riti were also brought under the umbrella of Alamkara. ]

Bhamaha’s Kavyaalamkara and Dandin’s Kavyadarsha are remarkably similar in their points of view, content and purpose. Both try to define the Mahakavya or the Sargabandha, elaborated in several Cantos. Their methods focus on the qualities of language (Sabda) and the meaning (Artha) of poetic utterances. Again, the format of their works is also similar. They often quote one another or appeal to a common source of reference or tradition. There are similarities as also distinctions between the views held by the two. At many places, it seems as if one is criticizing the other, without however naming. It is as though a dialogue of sorts had developed between the two authors. The major thrust of both the works pursues a discussion on the distinctive qualities (Guna) of Alamkara and debilitating distractions (Dosha) of poetic expressions.

Both the authors discuss the blemish or Dosha – the category that had come to represent the inverse of Alamkara, such as Jati, Kriya, Guna and Dravya. They held the view that just as certain Gunas or merits enhance the poetic effects, so also certain Doshhas, blemishes – both explicit and implied – destroy the poetic elegance and excellence.

But, they also pointedly disagreed on certain issues. For instance; Dandin appears to reject Bhamaha’s views on the differences between the narrative forms of Katha and Akhyayika (1.23.5)

– apādaḥ padasaṃtāno gadyam ākhyāyikā kathā / iti tasya prabhedau dvau tayor ākhyāyikā kila.

And, he also seems to argue against Bhamaha’s views that poetry must have Vakrokti .

Bhamaha , in turn, gives prominence to Alamkara, though he considered Rasa as an important element. According to him, all types of Kavya-s should have Vakrokti (oblique expressions) – as Samanya lakshana, Atishayokti (hyperbole) expressions transcending common usage of the of words (Svabhavokti) . It is only through these, he said, the ordinary is transformed to extraordinary.

Dandin differed from Bhamaha. He did not agree with the idea that there is no Alamkara without Vakrokti and that Savbhavokti, natural expressions, has no importance in Kavya. He argued, the Alamkara, the figurative expressions could be of two kinds – Svabhavokti and Vakrokti; and the former takes the priority (Adya Alamkrith). The Svabhavokti is a clear (sputa) and beautiful (Charu) statement of things as they are –

Svabhavokti raso charu yathavad vastu varnanam.

And, Svabhavokti , also known as Jati (Jatimiva Alamkrtinam) . It has to have a well balanced (Adhika-mrudva samanam) emphasis on the content, emotion and thought; as also on its form and poetic expression.

Svabhavokti cannot be Gramya (rustic), vulgar, insipid or stale ; but, it has to be a clear (sputa, pusta) , well coined, attractive (Charu), statement of things , as they are:

Navosthor Jatir- agramya shlesho klistaha sputo rasaha / vikata-akshara bandasha krutsva-mekatra durlabham // Bana’s harsha-charita//

(For more on Svabhavokti , please click here)

[Vakrokti has no equivalent in the western literary criticism. Vakrokti could be referred to as ‘oblique or indirect’ reference. It could also mean irony / ambiguity/ gesture/paradox / tension or all of them put together.]

Bhamaha did not speak much about the aspect of Guna. He briefly touched upon Madhurya (sweetness) , Ojas (vigor) and Prasada (lucidity) ; and , he did not even name them specifically as Guna-s. Further, he did not see much difference between Madhurya and Prasada :

Madhuryam abhibanchanti prasadam Ca samedhasah/ Samasavanti bhuyansi na padani prajunjate //KA.Ch. Bh_2.1 //

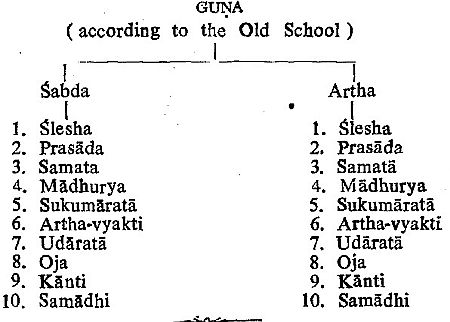

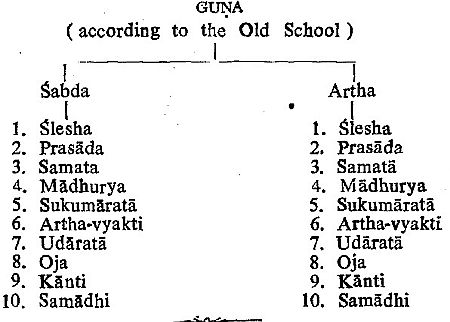

Dandin, on the other hand, devoted almost the entire of the first chapter of his Kavyadarsa to the exposition of two modes of poetic expressions, which ,for some reason, named them as : Vaidarbhi and Gaudi . He seemed to favor the former –Vaidarbhi. According to Dandin, the ten Gunas are the life of the Vaidarbhi mode of expression

– Slesha, Prasada, Samata, Madhurya, Sukumaratva, Arthavyaki, Udaratva, Ojas, Kanti and Samadhi.

Rajasekhara also hails the Vaidarbhi enthusiastically :

Aho hrudyam Vaidarhi Ritihi / Aho Madhuryam paryaptam / Aho nish-pramadaha Prasadaha // (Vidda-salabhanjika Act One)

[Dr. Victor Bartholomew D’avella writes : The two works of Alaṅkāraśāstra (poetics) that deal with the topic of linguistic purity in poetry – Bhāmaha’s Kāvyālaṅkāra and Vāmana’s Kāvyālaṅkārasūtra – address a number of specific grammatical problems ; but, in different ways. These represent different attitudes towards the interpretation of Pāṇini’s grammar. The final chapter of each work bears the title Śabdaśuddhi or Śabdaśodhana (Purification of Language); and, in them , each author gives guidelines for good, i.e., grammatically correct, poetic usage.]

Here, we need to briefly talk about the concept of Vritti, which like many such others that originated in the Natyashastra, later walked into the arena of the Kavya.

Bharata regards the Vrttis or the modes of expression as one among the most important constituent elements of the play. In fact, he considers the Vrttis as the mother of all poetic works

– sarveṣāmeva kāvyānāṃ-mātṛkā vṛttayaḥ smṛtāḥ (NS.18.4).

In a play, the Vrtti stands for the ways of rendering a scene; or, the acting styles and the use of language, diction that different characters adopt in a scene, depending upon the nature or the Bhava that is peculiar to that character– rasochita-artha-sandarbha.

The Vrttis are said to be of four kinds (vrttis caturdha) : Kaisiki; Sattvati; Arabhati; and, Bharati. The explanations provided by Bharata were principally with regard to the theatrical performances.

The Kaisiki-vrtti (graceful style) which characterizes the tender Lasyanga associated with expressions of love, dance, song as also with charming costumes and delicate actions portrayed with care, is most suited to Srngara-rasa

-(tatra kaisiki gita-nrtya-vilasadyair mrduh srngara- cestitaih ).

The Sattvati Vrtti (flamboyant style) is a rather gaudy style of expressing ones emotions with excessive body-movement; exuberant expressions of joy; and, underplaying mellow or sorrow moods. It is a way of expressing ones emotions (mano-vyapara) through too many words.

The Arabhati-vrtti is a loud, rather noisy and energetic style. It is a powerful exhibition of one’s anger, valour, bordering on false-pride, by screaming, shouting, particularly, in tumultuous scenes with overwhelming tension, disturbance and violence. It involves furious physical movements (kaya-vyapara).

And, the Bharati-vrtti is mainly related to a scene where the speech or dialogue delivery is its prominent feature. But, generally, the Bharati-vrtti, related to eloquence, is of importance in all the situations (vrttih sarvatra bharati).

*

And, when you come to the Kavya, the written texts, which are either read or recited (Shravya Kavya), you find that the Vritti which is predominant here is the Bharati Vrtti, the eloquent and free flowing speech or well composed words and sentences. And, there is, of course, the Kaisiki Vrtti, for depicting the scenes of love (Srngara), tenderness (Lavanya) , lovely evenings, moon lit nights, graceful locations and captivating speech etc.

And, the Sattavati – which is used for portraying violent action – is almost absent in the Kavya.

Bharati or the words of the text of the Kavya will be modified, according to the situation, by Kaisiki and Arbhati vrttis. This gives raise to two modes (Marga) or kinds of poetic diction or styles (Riti): Vaidarbhi Riti and Gaudi Riti. The excellence (Guna), like Madhurya (sweetness or lucidity) and Ojas (vigour) form their essence.

According to Dr. V. Raghavan, the Madhurya Guna and Kaisiki Vrtti (sweetness and delicate grace) characterize the Vaidarbhi Riti; while, Ojas Guna and Arbhati Vrtti (vigor and energy) go with the Gaudi Riti.

**

Both – Bhamaha and Dandin- seemed to be concerned with Kavya-sarira or the body of poetry. Both recognized that Kavya is essentially about language; and, that language is caught in a rather small compass. They seemed to argue that Kavya, however extensive, is knit together by its building-blocks – individual verses. Thus, the stanza is the basic unit of composition (Varna-vrtta metrics). And, every stanza has to strive towards perfection. They held that for achieving such perfection, it is essential that there should be a happy confluence of Sabda (word) and Artha (meaning) that produces a beauteous form (body) – Kavya-sarira – Sabda-Artha-sahitau-Kavyam . They also said that Alamkara, the poetic figures of speech, are essential ingredients of such beauteous harmony.

***

During the period of Bhamaha and Dandin, the plot of the Kavya was seen as its body. That, somehow, seemed to suggest that what is said is not as important as how it is said. The artistic expressions – ornate language, polished phrases seemed to be the prime issue. Therefore, the forms of Alamkara such as rhetorical figures of speech, comparisons, rhythms and such others gained more prominence.

In other words, they believed that Kavya is a verbal composition conveying a definite sense. It must be presented in a charming manner, decorated with choosiest rhetorical devices or figures of speech – Sabda-alamkara and Artha-alamkara.

The fundamental idea appeared to be that every notion can be expressed in infinite number of forms. Therefore, gaining mastery over language is a prerequisite for a credible poet. That is because, mastering the language enables one to have access to the largest possible number of variations; and, employ them most appropriately. Kuntaka in his Vakrokti- jivita (Ca. 10th century) says the : the Real word is that which is chosen out of a number of possible synonyms and that which is capable of expressing the desired sense most aptly. And the real sense is that which by its alluring nature , spontaneously delights the mind of the Sahrudaya ( person of taste and culture) –ahladkari sva spanda sundarah

Sabdau vivaksitartha kavachakautheyshu sathvapi I arthah sahrudaya ahladkari sva spanda sundarah // Vjiv_1.9 //

In the process, distinctions are made between figures of sound (Sabda-alamkara) and the figures of sense (Artha-alamkara). In the Sabda-alamkara, many and varied options of paraphrasing are used. Here, the option to express something in an obvious, simple and clear manner i.e. to say exactly what one means, is avoided. Such plain statements are considered Gramya (rustic) in contrast to urbane and refined (Nagarika) expressions. For instance; Bhamaha gives prominence to Alamkara, though he considered Rasa as important element. According to him, all types of Kavya-s should have Vakrokti (oblique expressions), Atishayokti (hyperbole) expressions transcending common usage of the of words (Svabhavokti) .It is only through these that the ordinary is transformed to something that is extraordinary.

The basic idea is : Kavya (poetry) is neither a mere thought nor emotion nor even a matter of style. It is how an alluring idea incarnates itself in beautiful expressions . The function of the Alamkara is to heighten the effect; to aid the poet to present his thought and emotion splendidly and naturally .

Alamkara is that which adorns (Bhusana) or that by which something is adorned – Alankarotiti alankarah; Alankriyate anena iti alankarah. And, Alamkara is ‘the beauty in poetry’ Saundaryam alahkarah – Vamana: K.A.S. 1.2. The function of an Alamkara is to provide a brilliant touch (Camatkara) to the object of description, Camatkrtir-alamkarah.

It is said; the term Alamkara combines within itself the elements of Poetics and of the Aesthetics as well. Alamkara-sastra is therefore the science which suggests and instructs how a Kavya should be; and, also prescribes certain canons of propriety.

As Nilakantha Diksita says: a Poet, who is gifted with the genius of creating extraordinary composition (vinyasa visesa bhavyaih), can turn even the common place situations into very interesting episodes.

Yaneva sabda-nvayam- alapamah / yaneva cartha-nvaya-mullikhamah / Taireva vinyasa visesa bhavyaih / sammohayante kavayo jaganti //

Thus, the concept of Alamkara essentially denotes that which helps to transform ordinary speech into an extraordinary poetic expression (Sabartha sahitya). The term Alamkara stands for the concept of embellishment itself , as well as for the specific means and terms that embellish the verse.

As the Alamkara concept began to develop into a system, there appeared endless divisions and sub-divisions of these Alamkaras. In the later poetics, Alamkara is almost exclusively restricted to its denotation of poetic figures as a means of embellishment.

During the later periods of Indian Poetics, the Alamkara School was subjected to criticism. It was said that the Alamkara School was all about poetic beauty; and, it seemed to have missed the aspect of the inner essence of Kavya. The later Schools, therefore, considered Alamkara as a secondary virtue . They declared that Poetry can exist without Alamkara and still be a good poetry.

Although the concept of Alamkara was played down in the later periods, its utility was always acknowledged as the Vishesha or quality of Sabda and Artha.

[ Please click here to read more on the concept of Alamkara]

Both – Bhamaha and Dandin – agree on the central place accorded, in Kavya, to Alamkara, figurative speech. Both held that the mode of figurative expression (Alamkara), diction (Riti) , grammatical correctness (Auchitya) , and sweetness of the sounds (Madhurya) constitute poetry. Both deal extensively with Artha-alamkara that gives forth striking modes of meaningful expressions.

Dandin also recognized the importance of Alamkaras, as means of adding charm to poetry – Kavya sobhakaran dharmann alamkaran pracasate – K.D. II.1. Dandin, however, gives far more space to the discussion on those figures of speech that are defined as phonetic features (Sabda-alamkara) e.g. rhyme (Yamaka) than does Bhamaha.

This distinction turns into a basic factor in all the subsequent Alamkara related discussions. The differences that cropped up on this point do not lie chiefly in the kind or quality of Alamkara; but, it seems more to do with function of the organization and presentation of the materials.

Let’s take a look at each of their works.

Bhamaha

Bhamaha’s work, called Kavyalankara or Bhamahalankara consists of six Paricchedas or chapters and about 400 verses. They deal mainly with the objectives, definition and classification of Kavya, as also with the Kavya-agama the elements of the Kavya , such as, Riti ( diction), Guna (merits), Dosha (blemishes ), Auchitya (Grammatical correctness of words used in Kavya) ; and , mainly with the Alamkara the figurative expressions .

As an addendum to the text , appearing after the final verse 64 of the last Chapter – Pariccheda (6.64) – there are two verses which summarize the topics covered by Kavyalankara. It says: the subject relating to the body of the poetry (śarīraṃ) was determined (nirṇītaṃ) in sixty verses; in one hundred and sixty verses , the topic of Alamkara was discussed; the defects and blemishes (Dosha) that could occur in a Kavya were mentioned in fifty verses; the logic that determines (nyāya-nirṇayaḥ) the format of a Kavya are stated in seventy verses; and, the criteria that specify the purity of words (śabdasya śuddhiḥ) used in a Kavya are enumerated in sixty verses.

Thus, in all, five subjects (vastu-pañcakam), in that order (krameṇa) , spread over six Paricchedas (ṣaḍbhiḥ paricchedair), comprising four hundred verses, have been dealt with by Bhamaha , for the benefit of the readers.

ṣaṣṭyā śarīraṃ nirṇītaṃ śataṣaṣṭyā tva-alaṅkṛtiḥ / pañcāśatā doṣadṛṣṭiḥ saptatyā nyāyanirṇayaḥ // Bh_6.65 // ṣaṣṭyā śabdasya śuddhiḥ syād ityevaṃ vastupañcakam /

uktaṃ ṣaḍbhiḥ paricchedair bhāmahena krameṇa vaḥ // Bh_6.66 //

Bhamaha’s kavyalankara , was perhaps, meant to facilitate a critical study of the subject of Kavya ; and, to serve as a practical handbook for the benefit of those engaged in the art of poetical composition .

At the end of Kavyalankara (Pariccheda 6. 64), Bhamaha says : after gaining a good understanding of the views of reputed poets; and, having worked out the characteristics of Kavya by ones own effort and intelligence, this work is composed by Bhamaha , the son of Rakrila Gomin, for the benefit of the good people .

avalokya matāni satkavīnām avagamya svadhiyā ca kāvyalakṣma / Bhāmahena grathitaṃ Rakrila-gomi sūnu-nedam // Bh_6.64 //

[The benefit of a Kavya, according to Bhamaha, is chiefly twofold, viz. acquisition of fame on the part of the poet and delight for the reader.]

While defining Kavya, Bhamaha says – sabdarthau sahitau kavyam; word and sense together constitute Kavya – in its both the forms of poetry and prose. The Kavya could be in Sanskrit, Prakrit (regional language) or even in Apabhramsha (folk language)

śabdārthau sahitau kāvyaṃ gadyaṃ padyaṃ ca taddvidhā / saṃskṛtaṃ prākṛtaṃ cānyad apabhraṃśa iti tridhā // Bh_1.16 //

Towards the end of the First Pariccheda, Bhamaha provides the broad guideline for composing a delightful and charming Kavya (śobhāṃ viracitamidaṃ). He instructs that the poet should exercise great caution ; and , use his discretion while selecting the words that are most apt in the given context.

He says: a garland-maker (malakara), while stringing together a garland, selects the sweet-smelling , beautiful looking flowers (surabhi kusumaṃ) ; and, rejects the ordinary ones ; and again , he also knows precisely that of the flowers so selected, which flower of a particular color and shape , placed in its appropriate position, would look pretty when interwoven with other flowers and enhance the beauty of the garland . In a similar manner; just as the garland-maker does (sādhu vijñāya mālāṃ yojyaṃ), the poet , while composing a Kavya, should take abundant care to select the appropriate words and place them in their right position, in order to produce a charming Kavya.

etad grāhyaṃ surabhi kusumaṃ grāmyam etannidheyaṃ dhatte śobhāṃ viracitamidaṃ sthānamasyaitadasya / mālākāro racayati yathā sādhu vijñāya mālāṃ yojyaṃ kāvyeṣvavahitadhiyā tadvadevā-bhidhānam // Bh_1.59 //

At the same time, Bhamaha cautions that mere eloquence is of no avail , if it fails to produce powerful poetic expressions. He exclaims : what is wealth without modesty?! What is night without the bright and soothing moon ? What use is of mere clever eloquence, without the capacity to compose a good poetry (Sat-kavita)?

vinayena vinā kā śrīḥ ; kā niśā śaśinā vinā / rahitā satkavitvena kīdṛśī vāgvidagdhatā // Bh_1.4 //

These definitions and instructions, obviously focus on the external element or the body of Kavya. His explanation implied that word and sense in a Kavya must be free from blemishes (nirdosa) and should be embellished with poetic ornamentation (salankara).

Bhamaha lays great stress on Alamkara, the figurative ornamentation. In his opinion, a literary composition, however laudable, does not become attractive if it is devoid of Alamkara, embellishments (Na kantamapi nirbhusam vibhati vanitamukham). Alamkara, according to him, is indispensable for a composition to merit, the designation of Kavya. Bhamaha is, therefore, regarded as the earliest exponent, if not the founder, of the Alamkara school of Sanskrit Poetics.

Bhamaha regards Alamkara as that principle of beauty which adorns poetry; and, that which distinguishes poetry from Sastra (scriptures) and Varta (ordinary speech) . He says; a poetry devoid of Alamkaras can have no charm – Na kantamapi nirbhusam vibhati vanita mukham – kavyalankara 1.36.

Bhamaha divides (Bh_2.4) Alamkara in four groups that are represented as layers of traditional development (Anyair udartha). They are similar to those four mentioned by Bharata (Upama =comparison; Rupaka = metaphorical identification; Dipaka = illuminating by several parallel phrases being each completed by a single un-repeated word; and, Yamaka = word-play by various cycles of repetition). In addition there is the fifth as alliteration (Anuprasa). Bhamaha in this context mentions one Medhavin (ta eta upamādoṣāḥ sapta medhāvinoditāḥ ) who perhaps was an ancient scholar who wrote on the Alamkara theory. The four groups that Bhamaha mentioned perhaps represent earlier attempts to compile Alamkara Shastra.

anuprāsaḥ sayamako rūpakaṃ dīpakopame / iti vācāmalaṃkārāḥ pañcaivānyairudāhṛtāḥ // Bh_2.4 //

Panini had earlier used the term Upama, in a general sense to denote Sadrasha (similarity) – Upamanani samanya-vacanaih / Upamitam vyaghradibhih samanya prayoge . But, Bhamaha accorded Upama, the element of comparison, much greater importance. Bhamaha discusses , at length (Pariccheda 2.verses 43 to 65), the criteria that should be kept in mind while assessing the degree of similarity and dissimilarities between the two objects that are chosen for comparison. He says; the two objects might resemble ; but they cannot be identical. Therefore, one should select only those qualities that are common to both; and, are appropriate in the context . But, in any case, the Upama should be real; and, should not be pushed to extremes.

Bhamaha recognized Vakrokti, the extra-ordinary turn given to an ordinary speech, as an essential entity underlying all Alamkaras; and, as one of the principal elements of a Kavya.

Saisa sarvaiva vakroktiranay artho vibhavyate / Yatno a’syam kavina karyah kol-amkaro’ naya vina / – kavyalankara 11.85

He also talked about the other elements of Kavya such as Riti, however, without much stress. He did not seem to attach much importance to Riti or mode of composition; because, in his opinion, the distinction between the Vaidarbhi and the Gaudi Riti is of no consequence. He however, introduced the notion of Sausabdya, the grammatical appropriateness in poetry- which relates to the question of style , in general, rather than to any theory of poetics.

tadetadāhuḥ sauśabdyaṃ nārthavyutpattirīdṛśī / śabdābhidheyālaṃkāra- bhedādiṣṭaṃ dvayaṃ tu naḥ // Bh_1.15 //

His rejection of the usefulness of the Riti and the Marga analysis of poetry perhaps accounts for his comparatively lighter treatment of the Gunas of which he mentions only Madhurya, Ojas and Prasada.

Bhamaha, in fact, rejects the Guna approach as being ‘not-trustworthy’. He is a thorough Alamkarika. His concern is with the form of poetry; and, not so much with its variations. He is also believed to have held the view that Gunas are three (and not ten) – guṇānāṃ samatāṃ dṛṣṭvā rūpakaṃ nāma tadviduḥ; and, are nothing but varieties of alliterations.

upamānena yattattvam upameyasya rūpyate / guṇānāṃ samatāṃ dṛṣṭvā rūpakaṃ nāma tadviduḥ // Bh_2.21 /

As regards Rasa, Bhamaha again links it to Alamkara. He treats Rasa as an aspect of Alamkara, Rasavat (lit. that which possesses Rasa). According to him, the suggested sense (vyangyartha), which is at the root of Rasa, is implicit in the vakrokti. Bhamaha did not however elaborate on the concept of Vakrokti. He meant Vakrokti as an expression which is neither simple nor clear-cut; but, as one which has curvature (vakra) – vakroktir anayārtho vibhāvyate. He took it as a fundamental principle of poetic expression .

[Bhamaha regarded Vakrokti as an essential entity underlying Alamkaras; but, is not clear whether or not Bhamaha regarded Vakrokti as an Alamkara per se]

Vakrokti is explained as an expressive power, a capacity of language to suggest indirect meaning along with the literal meaning. This is in contrast to svabhavokti, the matter-of-fact statements. Vakrokti articulates the distinction between conventional language and the poetic language. Vakrokti is regarded as the essential core of all poetic works as also of the evaluation and appreciation of art in general. Thus, vakrokti is a poetic device used to express something extraordinary and has the inherent potential to provide the aesthetic experience of Rasa.

Thus the seeds of Vakrokti, Riti, Rasa and Dhvani which gained greater importance in the later periods can be found in Bhamaha’s work.

However, the critics of Bhamaha point out that Alamkara-s of Bhamaha are nothing but external elements; and that he seemed to have bypassed the innermost element the Atman (soul) of poetry.

[ Please also read Kavalankara of Bhamaha (Edited , with translation into English) by Pandit P.V.Naganatha Sastry ; Motilal Banarsidass, 1970]

[Bhamaha also speaks of a concept called Bhavikatva , which he treats it as an Alamkara which has the virtue (Guna) of adorning not merely a sentence (vakya) but a passage or a composition (Prabandha) as a whole (Bhavikatvamiti prahuh prabandha –vishayam gunam– 3.53).

bhāvikatvam iti prāhuḥ prabandhaviṣayaṃ guṇam / pratyakṣā iva dṛśyante yatrārthā bhūta-bhāvinaḥ // Bh_3.53 //

It is described as Prabandha-guna, by virtue of which – as Dr. V Raghavan explains – the events or the ideas of the past (bhuta) and future (bhavi) narrated by the poet come alive and present themselves so vividly as if they belong to the present. As one reads a Kavya, the beauty and the essence of it should appear (dṛśyante) before one’s eyes; and, the events in the story should unfold in reality as if they are happening right in her/his presence (pratyakshayam-antva). Such a Guna of an Alamkara, the imagination or visualization, creating a mental image (vastu samvada) which instills a sense of virtual-reality (pratyakṣā iva dṛśyante yatrārthā) into the rendering, also goes by the name Bhavana or Udbhavana or Bhavika; the very essence of the Rasa realization (Rasavad). It binds the Kavi and the Sahrudaya together into a shared aesthetic experience.

Dandin also refers to Bhavikatva or Bhavika or Kavi-bhava, as a Prabandha-guna. But, he seems to relate it to Auchitya and Kavi-abhipraya, the attitude and the approach of the poet (Bhavah Kaveh abhiprayah). However, Dandin’s interpretation was not carried forward by the later writers, who preferred to follow Bhamaha.

And, in the later periods, Bhavika, somehow, got mixed up with other concepts (Prasada; Sadharanikarana etc) ; and , lost its focus .

For more on Bhavika , please click here; and here ]

Dandin

Dandin’s Kavyadarsa (7th century) is a very influential text. And , it covers a wide range of subjects concerning the Kavya , such as : the choice of language, and its relation to the subject matter; the components or the elements of Kavya : the story (kathavastu) ; the types of descriptions and narrations that should go into Mahakavya also known as Sarga-bandha (Kavya , spread over several Cantos) – sargabandho mahākavyam ucyate tasya lakṣaṇam; the ways (Marga) of Kavya, regional styles characterized by the presence or absence of the expression-forms (Guna); various features of syntax and semantics; factors of Alamkara- the figurative beauty of expressions; and the Alamkara-s of sound (Sabda) and sense (Artha).

Dandin in his Kavyadarsha said every poem needs a body and Alamkara. By body he meant set of meaningful words in a sentence to bring out the desired intent and effect. Dandin clarified saying ; now, by body (sariram), I mean a string of words (padavali) distinguished by a desired meaning (ista-artha) – sariram tadvad ista-artha vyvachinnapadavali.

taiḥ śarīraṃ ca kāvyānām alaṃkārāś ca darśitāḥ – śarīraṃ tāvad iṣṭārthavyavacchinnā padāvalī // DKd_1.10 //

In the succeeding Karikas, Dandin , under the broad head Sariram discusses such subjects as meter, language, and genres of poetic compositions ( epic poems, drama etc.,) , and the importance of such categories. Such words putting forth the desired meaning could be set either in poem (Padya) , prose (Gadya) or mixture (Misra) form.

padyaṃ gadyaṃ ca miśraṃ ca tat tridhaiva vyavasthitam – padyaṃ catuṣpadī tac ca vṛttaṃ jātir iti dvidhā // DKd_1.11 //

Dandin accepted Alamkara-s as beautifying factors that infuse grace and charm into poetry; and, as an important aspect of which raises far above common-place rustic crudity.

Kamam sarvepya alankaro rasam-arthe nisincatu / Tathapya gramyatai vainam bharam vahati bhuyasa // kavyadarsa. 1.63.

He said; Alamkara-s are the beautifying factors of poetry and they are infinite in number; and, whatever beautifies poetry could be called Alamkara

Kavya sobhakaran dharmann-alahkaran pracaksate – kavyadarsa. II. 1

In his work, Dandin talks mainly about Alamkara-s that lend beauty and glitter to the Kavya- Sabda-alamkara and Artha-alamkara. The first covers natural descriptions, similes (Upama) of 32 kinds, metaphors (Rupaka) , various types of Yamaka (poetic rhymes) that juggle with syllables and consonants . Among the Artha-alamkara is Akshepa that is to say concealed or roguish expressions, such as hyperbole (Atishayokti) , pun or verbal play producing more than one meaning (Slesha) , twisted expressions (Vakrokti). And, he said : whatever that lends beauty to poetry is Alamkara: Kavya-sobhakaran dharman-alankaran pracaksate

Dandin is, generally, accused of attaching more importance to the elegance of the form and to erudition than to creative faculty. I reckon , that is rather unfair. He was attempting to draw a clear distinction between kavyasarira and Alamkara.

Dandin, like Bhamaha, belongs to what came to be known as Alamkara School. But, his emphasis is more on Sabda-alamkara, the ornaments of sound (Sabda), which is not prominent in Bhamaha. The bulk of the third Pariccheda of his Kavyadarsa is devoted to an exhaustive treatment of Chitrakavya ( which later came to be labeled as Adhama – inferior- Kavya) and its elements of rhyming (Yamaka) , visual poetry (matra and Chitra) and puzzles (Prahelika).

With regard to Rasa, Dandin pays more importance to it than did Bhamaha. While dealing with Rasa-vada-alamkara, the theory of Alamkara combined with Rasa, he illustrates each Rasa separately. Dandin pays greater attention to Sabda-almkara than does Bhamaha. Dandin says : thanks to the words alone the affairs of men progress ( Vachanam eva prasadena lokayatra pravartate )

Iha śiṣṭānuśiṣṭānāṃ śiṣṭānām api sarvathā – vācām eva prasādena lokayātrā pravartate // DKd_1.3 //

Dandin also gives importance to alliteration (Anuprasa), which he discusses under Madhurya Guna, the sweetness or the alluring qualities of language. Alliterations and rhyming (Yamaka) were not ignored by Bhamaha (they were, in fact, his first two types of Alamkara); but, treated lightly. In comparison, are accorded full treatment in Dandin‘s work.

Bahamas, as said earlier, mentions just four types of Alamkara-s such as: Upama, Rupaka, Dipaka and, Yamaka. He does not, however, go much into their details. Dandin, on the other hand, while accepting the same figures as Bhamaha, explores the variations provided by each figure internally. He notices thirty-two types of similes (Upama) as also various other forms of Rupaka (Metaphors), etc. This effort to look at Alamkaras in terms of ‘sound-effects’ than as theoretical principles was rejected by subsequent authors.

[Rudrata also classified the Artha-alamkara into four types : Vastava (direct statement of facts) ; Aupamya (simile); Atishaya (exaggeration); and , Slesha (play or twist of words)

Udbhata does not, however, divide Alamkaras into Sabda-alamkaras and Artha-alamkaras; but , he gives six groups of Alamkaras; of which , four are Sabda-alamkaras and the rest are Artha-alamkaras.

He has given much importance to Anuprasa; and, his concept of Kavya-vrtti is based on Anuprasa. Among the Artha-alamkaras, he gives greater importance to Slesa, which he treats as the very secret of the poetic language. Udbhata considers both Gunas and Alamkaras as the beautifying factors of poetry]

*

One of the criticisms leveled against Dandin is that he uses the term Alamkara in the limited sense of embellishment rather than as a broader theory or principle of Poetics. He defines Kavya in terms of its special features: Kavyam grahyam Alamkarat; Saundaryam alamkarah . The Alamkara here is not the principle but Soundaryam, beauty of the expression.

Dandin devotes a section of the first chapter or Pariccheda, to the ten Gunas or qualities mentioned by Bharata.

Slesah prasadah samata samadhir madhuryamojah Padasaukumaryam/ Arthasya Ca vyaktirudarata Ca kantisca kavyasya Gunah dasaite //NS.17.95//

śleṣaḥ prasādaḥ samatā mādhuryaṃ sukumāratā – arthavyaktir udāratvam ojaḥ kānti samādhayaḥ // DKd_1.41 //

But, Bharata had not discussed much on the Guna-doctrine; and nor did he state whether they belonged to Sabda or Artha; nor in what relation they stand in poetry. He merely stated that ten Gunas are the mere negation of Dohsa

Dandin went on and said the Gunas that make beautiful are called Alamkara ; and, he included the Gunas dear to him under Alamkara. (Kavya shobha karan dharman alamkaran pracakshate).

kāvya śobhā kārān dharmān alaṃkārān pracakṣate – te cādyāpi vikalpyante kas tān kārtsnyena vakṣyati // DKd_2.1 //

[But, he does not seem to consider Gunas and Alamkaras as identical; for the Gunas relate to the forms of language – say, sound or its capacity to produce a meaning ; but, not specifically to the categories of Alamkara.]

But Dandin qualified his statement by remarking that Guna is an Alamkara belonging to the Vaidarbhi-Marga exclusively. Thus, it appears, in his view, Guna forms the essence or the essential condition of what he considers to be the best poetic diction. The importance of Gunas lies in their positive features. The contrary of a particular Guna marks another kind of poetry. Thus Ojas vigor (use of long compounds) marks the Gaudiya Marga; and, its absence marks the Vaidarbhi Marga.

It should be mentioned; Dandin elaborates a theory of two modes (Marga) or kinds of poetic diction or styles to which he assigns geographical names Vaidarbhi and Gauda. He mentions that excellences (Guna, like sweetness or lucidity) form their essence.

Iti vaidarbhamargasya prana dasa gunah smrtah/ Esamviparyah prayo drsyate gaudavartmani //KD.1.42//

But, such classification later became a dead issue as it was not logical; and many are not sure if such regional styles did really exist in practice. Only Vamana took it up later; but, diluted it.

Vamana laid more emphasis on Riti; yet, he accords importance to Alamkaras . He clearly states that it is a synonym for Saundarya i.e., beauty; and, because of this beauty, poetry is distinguished from Sastra and Lokavarta.

He further said that although Gunas make a poem charming, the Alamkaras enhance such poetic charm :

Kavya sobhayah kartaro dharmah gunah tad atisayahetu vastvalankarah – kavyalankarasutra – III.l

For Bhamaha , Alamkara is the principle of beauty in poetry; and, for Dandin, Alamkara is Sobha-dharma. Dandin also considers the whole Vanmaya (literature) into two modes of figurative expression.

But, Vamana takes a broader approach than that of Bhamaha and Dandin; and, he recognizes Alamkara as Saundarya itself. Thus, he not only considered Alamkara as an essential element of poetry; but, also identified beauty with it – Saundaryam alamkarah – kavyalankarasutra; 1.2

Vamana , in his Kavyalamkara, stated that , poetry is acceptable from the ornamentation (Alamkara) point of view. But , he is careful to explain Alamkara not in the narrow sense of a figure of speech, but in the broad sense of the principle of beauty. He says : Kavyam grahyam alamkarat; Saundaryam alamkarah // VKal_1,1.1-2 // .

Dandin also mentions Vakrokti; but, he does not treat it as essential to Alamkara.

Chapter five of Kavyadarsa is an inquiry into poetic defects (Dosha) that spring from logical fallacies. It is based in the view that there is a limit to the poet’s power to set aside universal laws of reasonable discourse . The poet does not wish to speak nonsense; his ultimate declaration should be as rational and as reasonable as that of any other person . Poetry does not therefore lie in the poet’s intention as such, but the unusual means he adopts to convey his meaning. This line of argument puts poetry properly on both sides of what is logical and what is illogical.

[ Before going further , let me mention in passing about the Kannada classic Kavi-raja-marga ….

It is said; Kavi-raja-marga (Ca.850 C.E.), the earliest and one of the foundational texts available on rhetoric, poetics and grammar in the Kannada language, was inspired by the Kavyadarsa of Dandin . It is generally accepted that Kavi-raja-marga was co-authored by the famous Rashtrakuta King Amoghavarsha I Nrupathunga (who ruled between 814 A.D. and 878 A.D); and, his court poet Sri Vijaya – ‘Nrupatungadeva-anumatha’ (as approved by Nrupatungadeva).

Though the Kavi-raja-marga generally follows Kavyadarsa, it goes far beyond and tries to forge a meaningful interface between Sanskrit and Kannada.

Kavi-raja- marga, praised as a mirror and guiding light to the poets, was perhaps composed during the formative stages in the growth of Kannada literature. And, it was meant to standardize the writing styles in Kannada, for the benefit of aspiring poets. It was also intended to serve as a guide book to the Kannada Grammar, as it then existed.

The work is composed of 541 stanzas, spread over three Chapters. The First Chapter enumerates errors (Dosha) that one might possibly commit while writing poetry; the Second Chapter deals with Sabda-alamkara; and, the Third Chapter covers Artha-alamkara.

The Book, among other things, dwells on the earlier two styles of composing poetry in Kannada (kavya-prakaras) – the Bedande and the Chattana; and , the way of prose writing – the Gadya-katha. And, it mentions that these styles were recognized by Puratana-kavi (earlier poets) and Pruva-acharyas (past Masters).

In that context, Kavi-raja-marga recalls with reverence many Kannada poets, authors and scholars who preceded its time: Vimalachandra , Udaya, Nagarjuna, Jayabhandu and the 6th century King Durvinita of the Western Ganga Dynasty as the best writers of Kannada prose; and, Srivijaya; Kavisvara, Pandita, Chandra and Lokapala as the best Kannada poets.

But, sadly, the works of all those eminent poets and authors are lost to us.

The Kavi-raja-marga continues to inspire, educate and guide the Kannada scholars, even to this day.]

The older School (Prachina) – of Bhamaha, Dandin, Vamana and others – dealt with natural or human situation idealized by the poet for its own sake. The attention of the Prachina School was focused on ornamented figures of speech (Alamkara) and the beauty (sobha, carutva) of the expression or on the ‘body’ of poetry.

The Navina School represented by Anandavardhana (9th century) and his theory of Dhvani mark the beginning of a new-phase (Navina) in Indian Poetics. It pointed out that the reader should not stop at the expression but should go further into the meaning that is suggested, or hinted, by it. The Navina School laid more importance on the emotional content (Bhava) of the Kavya. But, here, the emotive element was not directly expressed in words (Vachya) ; but , had to be grasped by the reader indirectly (Parokshya ) through suggestions. Yet, through the description of the situation the reader understands the emotion and derives that exalted delight, Rasa.

Raja Bhoja , in his Srngaraprakasha, classified Alamkara into those of Sabda (Bahya – external); those of Artha (Abhyantara – internal) and, those of both Sabda and Artha (Bhaya-abhyantara – internal as well as external). In any case; Alamkara has to aid the realization of the Rasa or to heighten it; and, shall not dominate the vital aspects of the Kavya.

Here, the words (Sabda), explicitly mean (Vakyartha) the body (Sarira) of the Kavya. The subtle, suggested essence of the Kavya that resides within and is extracted with delight by the cultured reader (Sahrudaya) is the Dhavni.

Thus the evolution of the Navina School marks a transition from the ‘outer’ element to the ‘inner’ one, in regard to the method, the content and appreciation of the Kavya. The criteria, here, is not whether the expression sounds beautiful; but, whether its qualities (Guna) are apt (Auchitya) to lead the reader to the inner core of the poetry.

Lets talk about these and other elements of Kavya in the subsequent issues.

Continued in

The Next Part

Sources and References

Glimpses of Indian Poetics by Satya Deva Caudharī

Indian Poetics (Bharathiya Kavya Mimamse) by Dr. T N Sreekantaiyya

Sahityashastra, the Indian Poetics by Dr. Ganesh Tryambak Deshpande

History of Indian Literature by Maurice Winternitz, Moriz Winternitz

A History of Classical Poetry: Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit by Siegfried Lienhard

Literary Cultures in History by Sheldon Pollock

The Philosophy of the Grammarians, Volume 5 By Harold G. Coward

A Comparative Study of the Indian Poetics and the Western Poetics by Mohit Kumar Ray

A history of Indian literature. Vol. 5, Scientific and technical …, Volume 5 by Edwin Gerow

For more on What is Kavya , please click here

Other illustrations are from Internet

Banabhatta, sadly, passed away before he could complete his magnum opus Kadambari woven into complicated, interrelated plots involving two sets of lovers passing through labyrinth of births and re-re-births. It was later completed by his son Bhushanabhatta.

Banabhatta, sadly, passed away before he could complete his magnum opus Kadambari woven into complicated, interrelated plots involving two sets of lovers passing through labyrinth of births and re-re-births. It was later completed by his son Bhushanabhatta.