[I could not arrange the topics in a sequential order (krama). You may take these as random collection of discussions; and, read it for whatever it is worth. Thank you.]

The Court Poet

So far in the series we have talked about Poetry (Kavya) and the Poetics (Kavya Shastra), let us round up the discussion with a few words about the Poet (Kavi) himself.

Poetry in India, of course, is very ancient; and has been in vogue even from the Vedic times. In the context of Rig Veda, Kavi refers to one who through his intuitional perception (prathibha), sees the unseen (kavihi-krantha-darshano- bhavathi) and gives expression to his vision (Darshana), spontaneously, through words. He is the wise Seer. It was said: one cannot be a Kavi unless one is a Rishi (naan rishir kuruthe kavyam). However, not all Rishis are Kavi-s. A Kavi is a class by himself.

But, the Kavi, the Poet, we are referring to in the series and here is not the Vedic Kavi. He is far different from the Vedic Kavi in almost every aspect; and, is vastly removed from him in space, time, environment, attitude, objective etc. And, his poetry is neither a Rik nor a mantra; but, is a cultivated art , ornate with brilliance and flashing elegance.

The Sanskrit poet who creates Kavya is neither a Rishi nor a seer; but, he is very much a person of the world who has taken up writing as a profession to earn his living. He usually sprang from a class that possessed considerable cultural refinement. And, Sanskrit being the language of the academia and the medium of his work, he was well versed in handling it.

He is urbane, educated and is usually employed in the service of a King. Apart from writing classy poetry, his other main concern is to please and entertain his patron. He is very much a part of the inner circle of the Court; and, is surrounded by other poets and scholars who invariable are his close rivals in grabbing the King’s attention and favors.

During those times, a Great King would usually have in his service a number of poet-scholars who vied with each other to keep the King happy and pleased. Their main task was to entertain the King. Apart from such Court poets, there were a large number of wandering bards who sang for the common people. They walked through towns and villages singing songs of love and war. Of course, their recitations were not classy or of the standard of the court poet-singers.

As Vatsayana (in his Kama sutra) describes, the Court poet, generally: is an educated suave gentleman of leisure having refined taste and versatility; fairly well-off; lives in urban surroundings (Naagara or Nagarika); loves to dress well (bit of a dandy, indeed- smearing himself with sandal paste, fragranting his dress with Agaru smoke fumes, and wearing flowers); appreciates art, music and good food; and, loves his occasional drink in the company of friends and courtesans.

A Court poet, sometimes, is also portrayed as rather vain, nursing a king-sized ego; and, desperately yearning to be recognized and honored as the best, over and above all the poets in the Royal Court.

Thus, his attitudes find expressions in various ways – outwardly or otherwise. The dress, polished manners and cosmetics all seemed to matter. But, more importantly, it seemed necessary to have a sound educational foundation, idioms of social etiquette , and a devotion to classical literature (Sahitya) , music (Samgita) and other fine arts (lalita kala). Though his Poetry was developed in the court, its background was in the society at large.

The Poet

Rajasekhara an eminent scholar, critic and poet, was the Court poet of the Gurjara – Prathihara King Mahendrapala (Ca.880 to 920 AD) who ruled over Magadha. In his Kavyamimamsa, which is virtually an Handbook guiding aspiring poets, Rajasekhara outlines the desirable or the recommended environment, life-style, daily routine, dispositions etc for a poet, as also the training and preparations that go to make a good poet.

Sanskrit Kavya, in middle and the later periods, grew under the patronage of Royal courts. And, sometime the King himself would be an accomplished scholar or a renowned poet.

According to Rajasekhara, many of the poets depended on the patronage of local rulers and kings. Among them, the more eminent ones were honored as Court-poets (Asthana Kavi). Those who performed brilliantly endeared themselves to the king; and, were richly rewarded.There was, therefore, a fierce rivalry among the poets in the King’s court to perform better than the next poet; and , somehow, be the king’s favorite.

A successful poet would usually be a good speaker with a clear voice; would understand the language of gestures and movements of the body; and would be familiar with other languages , arts as well.

An archetypical picture of a poet that Rajasekhara presents is very interesting. The Kavi, here, usually, lives in upper middle class society that is culturally sensitive. His house is kept clean and comfortable for living. He moves from places – changing his residence – about three times in an year, according to the seasons. His country residence has private resting places, surrounded by antelopes, peacocks and birds such as doves, Chakora, Krauncha and such other. The poet usually has a lover (apart from his wedded wife) to whom he addresses his love lyrics.

As regards the daily life of the poet, Rajasekhara mentions the Kavi would usually be a householder following a regulated way of life such as worshipping at the beginning of each day, followed by study of works on poetics or other subjects or works of other poets. All these activities are, however, preparatory; they stimulate his innate power of creativity and imagination (prathibha). His creative work proper (Kavya-kriya) takes part in the second part of the day.

Towards the afternoon, after lunch, he joins his other poet-friends,seated comfortably (tatra yathāsukhamāsīnaḥ kāvyagoṣṭīṃ pravarttayed) where they indulge in verse-riddle games structured around question-answers (Prashna-uttata). Sometimes, the poet discusses with close friends the work he is presently engaged with – antarāntarā ca kāvyagoṣṭhīṃ śāstra-vādā-nanujānīyāt.

In the evening, the poet spends time socializing with women and other friends, listening to music or going to the theater. The second and the third parts of the night are for relaxation, pleasure and sleep.

Of course, not all poets followed a similar routine; each had his own priorities. Yet; they all seemed to be hard-working; valuing peace, quiet and the right working conditions. They were of four kinds:

catur-vidhaś-cāsau/asūryampaśyo,niṣaṇṇo, dattāvasaraḥ, prāyojanikaśca /

There were also those who chose to write when moved or inspired or during their leisure . They were, as Rajasekhara calls them, occasional poets (data-vasara). Among them was a class who wrote only on occasions (prayojanika) to celebrate certain events – dattāvasaraḥ, prāyojanikaśca.

Rajasekhara also mentions of those poets who were totally devoted to their poetic work. They invariably shut themselves from daylight (asūryampaśyo), dwelling in caves or remote private homes away from sundry noises and other disturbances

As regards the poet’s writing materials and other tools, Rajasekhara mentions that the writing materials are almost always within the reach of the poet; and, are contained in a box. The contents of the box were generally: a slate and chalk; a stand for brushes and ink-wells; dried palm leaves (tāḍipatrāṇi) or birch bark (bhūrjatvaco); and an iron stylus (kaṇṭakāni). The common writing materials were palm leaves on which letters were sketched with metal stylus. The alternate writing surface was the birch bark cut into broad strips. The slate and chalk was for preparatory or draft work.

tasya sampuṭikā saphalakakhaṭikā, samudgakaḥ, salekhanīkamaṣībhājanāni tāḍipatrāṇi bhūrjatvaco vā, salohakaṇṭakāni tāladalāni susabhmṛṣṭā bhittayaḥ, satatasannihitāḥ syuḥ /

What does it take to make one a ‘good’ poet

There is an extended debate interspersed across the theories of Indian Poetics speculating on what does it take to make one a good poet.

Dandin mentions the requisites of a good poet as: Naisargika Prathibha natural or inborn genius; Nirmala-shastra – jnana clear understanding of the Shastras; Amanda Abhiyoga ceaseless application and honing ones faculties.

Bhatta-tauta explained Prathibha as the genius of the intellect which creates new and innovative modes of expressions in art poetry – Nava-navonvesha –shalini prajna prathibha mathah

Rudrata and Kuntaka add to that Utpatti, the accomplished knowledge of the texts and literary works; and, Abhyasa, constant practice of composing poetic works.

According to Vamana, Utpatti includes in itself awareness of worldly matters (Loka-jnana); study of various disciplines (Vidya) ; and , miscellaneous information (Prakirna).

Vamana also mentions: Vrddha seva – instructions from the learned experienced persons; Avekshana– the use of appropriate words avoiding blemishes by through study of Grammar; and ; Avadhana – concentration or single pointed devotion to learning and composing as other the other areas of study and learning.

Thus, to sum up, most seem to agree that the natural inborn genius is the seed out of which poetry sprouts (Kavitva-bijam prathibhanam – Vamana. K.S.13.6); and that talent needs to be nurtured and developed through training Utpatti (detailed study of Grammar, the literarily works and scriptures as also of knowledge of worldly matters) ; and Abhyasa , Abhiyoga, Prayatna (constant practice of composing poetry) .

An aspiring poet gifted with natural talent would do well to sincerely follow the prescribed regimen either on his own or , better still, under the guidance of a well-informed teacher who himself is a poet or a learned scholar.

**

The great scholar Abhinavagupta (Ca.950-1020 AD) in his Lochana (a commentary on Anandavardhana’s Dhvanyaloka) says that Prathibha the intuition might be essential for creation of good poetry. But, that flash of flourish alone is not sufficient. Abhinavagupta explains that Prathibha is inspirational in nature; and, it does not last long; and it also, by itself or automatically, does not transform into a work of art or poetry. There definitely is a need of a medium that obeys objective laws (which he calls unmeelana –shakthi) ; and, which sustains, harnesses and gives form and substance to those fleeting moments of inspiration. Apart from that, the aspiring poet has to study hard, broaden his intellect, hone his skills and practice his craft diligently. It is only then, he says, a poetic work can bring forth refined, lively and forceful expressions that delight all.

**

Kavi-shiksha

Rajasekhara, just prior to Abhinavagupta, had also emphasized the importance of training and preparation in the making of a poet. He treats the subject in a little more detail.

He mentions that the cultivator of Sanskrit poetry, variously known as Kavi, Budha or Vidwan, is not born as poet; nor is he self taught. Anyone gifted with talent (Prathibha) to create poetry and determined to become a poet should be prepared for detailed education (Utpatti) spread over long years of hard work (abhiyoga, prayatna), study (Abhyasa) with ceaseless dedication (Shraddha) . He should have the strength of mind not to be enticed away from his chosen path; and should pursue the study of Kavya in all its forms and layers with single-pointed (Ekagra) devotion.

Rajasekhara remarks there is no merit in becoming a half-baked poet. If one is truly sincere to his intention, then one should strive to become a professional poet of true class . He should make that as his life-ambition, the ultimate goal in his life; and, should be prepared to make whatever sacrifices it demands.

The ardent learner is advised to seek guidance from a professional, learned teacher (Upadhyaya) and study under him the basic subjects of phonetics such as Vyakarana (Grammar) , Nirukta (Etymology) , Kosha (lexicon) , Alamkara (ornamentation) and Chhandas ( poetic meters) along with standard works on Kavya Shastra (Poetics). Apart from studying these subjects individually, they should be studied with special reference to classic works of Kavya that have been written according to the formats and disciplines prescribed in texts of Kavya Shastra.

The study of the works of the Master would help the student to gain wholesome appreciation of the poetic process, the techniques of various forms of poetry and their components, such as meter (Chhandas), grammar (Vyakarana) , embellishments (Alamkara) etc. He should try out the principles he learnt by applying them to practice-poems (Abhyasa kriti) to be crafted as a part of his learning process.

The training included exercises to improve the student’s literary and the non-literary vocabulary, use of right words, picking the apt terms among the various synonyms; developing metrical skill; finding the most appropriate expression for each attribute, the most suitable simile, etc; and, creating verbal structure according to syntax within the rhythmic framework.

The preparation and the training would also include gaining familiarity with various branches of learning, such as: art (Kala), music (samgita), erotic’s (kamasastra), logic (nyaya), state craft (arthasastra) as also of the natural world of mountains, oceans, trees , birds and animals etc . He could also gain an understanding of sciences, astronomy, gemology etc. And, of course, familiarity with such important sources of literary material as the Epics Ramayana and Mahabharata as well as with the Puranas was also essential

The object of such elaborate training was to ensure that the student learnt to work at his text in a deliberate manner respecting the host of rules and norms that govern Kavya; and also to ensure that his poetic compositions grow out of a clear thought process based on a free but carefully made choice of all the elements. Far more important was the organization and co-ordination of these elements to give the composition the quality of a work of art.

Thus, at the end, very little would separate the connoisseur and critic from the writer of kavya.

Banabhatta

While on the subject of ‘The Poet’, I cannot resist talking about the redoubtable Banabhatta. Let’s dwell on him for a while.

The Sanskrit poets are generally reticent when it comes to their personal details. Some might perhaps give out frugal particulars such as the names of their parents, their Gotra and the village they came from. Beyond that, hardly any information that might throw light on the cultural and social life of their period is given out. Sometimes, even the simple task of ascertaining their period, by itself, becomes a minor exercise.

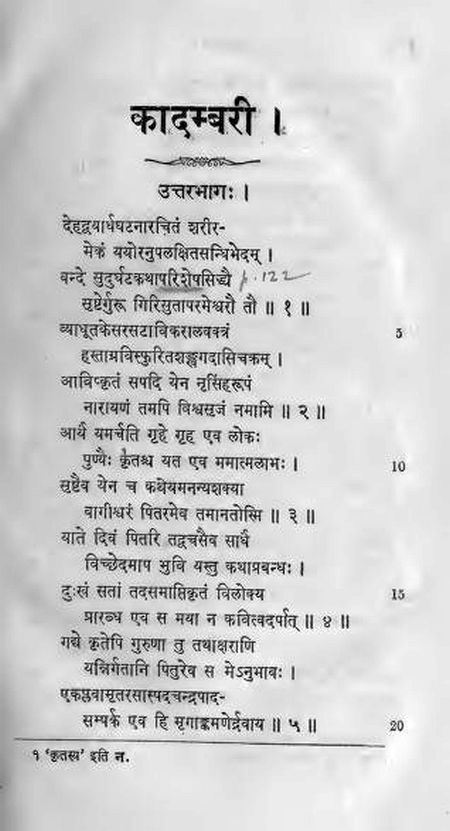

A notable exception to such general practice was Banabhatta, a versatile scholar and poet, a contemporary and a close associate of King Harsha Vardhana of Thaneshvar and Kanuj, who ruled over North India from 606 to 647 A D. Banabhatta’s fame rests on his remarkable romantic prose work Kadambari, perhaps the world’s first Novel; and on Harshacharita a glorified biography of his friend and patron King Harsha Vardhana.

[Banabhatta is also credited with some other, lesser known, works. It is said; Banabhatta composed a devotional poem Candisataka, of one hundred and two stanzas, in praise of goddess Chandi. Further, Parvathi-parinaya, a drama in five acts describing the marriage o f Siva and Pravathi; and, another drama, Mukutataditakam concerning the conflict between Bhima and Duryodhana, are also ascribed to Banabhatta. But, nothing much is known about these works.]

Banabhatta, sadly, passed away before he could complete his magnum opus Kadambari woven into complicated, interrelated plots involving two sets of lovers passing through labyrinth of births and re-re-births. It was later completed by his son Bhushanabhatta.

Banabhatta, sadly, passed away before he could complete his magnum opus Kadambari woven into complicated, interrelated plots involving two sets of lovers passing through labyrinth of births and re-re-births. It was later completed by his son Bhushanabhatta.

In this marvelous complex texture, men and demigods; the earth and the regions beyond; the natural and the supernatural; love and curses, are all blended naturally. There are also amazing transformations of gods into demigods; demigods into men; men into animals and birds. Their relations persist and continue over successive births. They create unusual situations that make the author to construct intriguing devices to advance the development of the plot.

There is a well-known, interesting adage with a play on words: Kādambari rasajnānām āhāropi na rochate- while savouring ‘Kādambari‘ – the book, readers lose interest in (eating) food (Kādambari)”.

Bana, especially, in his Kadamabari, was celebrated for his rich figurative speech; his command over language; his clever use of words; and, his deep understanding of human nature. His descriptions are amazing; his similes and metaphors are matchless; and, even his critics could not help admire, exclaim Bana’s brilliance. He had a unique manner of describing even the most familiar things in life. For instance; look at the ingenuity in scripting the love-message that Princess Kadambari sent to her lover:

“What message can I send to you? If I say: ‘You are very dear to me’, that would be a needless repetition; If I say: ‘I am yours’ , that would be a childish prattle; In case I say: ‘I have deep affection for you’, that would be improper for a Queen; I cannot say: ‘Without you I cannot live’, because that would be rather untrue; If I cry out: ‘I am overtaken by Cupid’, that would sound silly ; I cannot, of course, say : ‘I have been forcibly abducted’, that would be sheer helplessness of a captive girl; ‘ If I insist : You must come at once ‘, that might be construed as arrogance ; If , on the other hand, I offer myself and say : ‘I will come to you of my own accord’, then I could be mistaken to be a horny , fickle minded woman; If I submit , imploring : ‘This slave is not devoted to anybody else, but to you alone’, then that would amount to demeaning myself , a Queen; If I make a pretext : ‘I do not send messages for fear of refusal’, that would be a rather senseless excuse lacking trust in you; If I beseech you wailing : ‘I shall suffer terrible pains in case I lead an undesired life’, that would suggest that I am weak and lacking conviction in myself; and, If I finally declare : ‘You will come to know of my love through my death’, that would be pointless”. [History of Indian Literature by Moriz Winternitz (page 409)]

[ Please click here for Kadambari, with a scholarly introduction and translation, as rendered by by Prof. C M Ridding, formerly scholar of Griton College, Cambridge; published by the Royal Asiatic Society, London , 1896

Please click here for Banabhatta’s Kadambari , translated with an Introduction by Gwendolyn Layne; Garland Publishing, NY & London;1991 ]

Banabhatta gives glimpses of his early life and youth in the introductory verses of his Kadambari and in the first two Ucchavasas of the Harshacharita. And, in the third Ucchavasa of Harshacharita he describes how he came to write that work.

His story is truly amazing.

Banabhatta mentions that he was born to Chitrabhanu and Rajadevi of Bhojaka Brahmin family, which was rich in wealth and in learning, belonging to Vatsyayana Gotra. Chandrasena and Matrsena were his half-brothers. And, Ganapathi, Adipathi, Tarapathi and Shyamala were his parental cousins..

They lived in the village of Pritikuta on the banks of Hiranyabahu (the Sona River) which raises in the Vindhya hills and flows through the Dandaka forest. The scholars opine that the ancestral home of Banabhatta might have been in the region of Madhya Pradesh from where the Sona river rises . From here , Banabhatta, later , went to the court of King Harshavardhana in Kanyakubja (Kanuj) in Uttar Pradesh.

Bana lost his mother Rajyadevi at a tender age. He was brought up by his father Chitrabhanu who was learned in scriptures and in literature. Chitrabhanu played a large part in molding his interests ; and, remained a great influence even in the later years .

Bana’s teacher was said to be one, Bhravu . Banabhatta, at the commencement of his Kadambari, submits his salutations to his teacher Bhravu, who was also respected by the kings of the Mukharin dynasty – (namami bharvos-carana-ambuja-dvayam sasekharair moukharibhih krtarcanani). The commentator, Bhanuchandra, however, mentions that Banabhatta’s teacher was known as Bhatusa or Bhartsu.

Sadly, Bana lost his father while he was just about fourteen years of age. He felt his father’s absence very deeply and missed him sorely. The death of his father left the clueless young Bana , just stepping into adolescence, rather rudderless. He came into wealth and money with none to guide him. After recovering from anguish and sorrow, he found life rather hollow and boring; grew more and more impatient by each day; and got into irregular life of nasty habits. Bana went totally astray indulging in carefree, reckless, restless life in the company of a most weird bunch of friends.

His motley crowd of friends, medley of varied talents, came from an amazing assortment of backgrounds , various classes of life and professions. Bana, in fact, names about forty-four of his friends, some them of dubious character. His friends circle included poets, singers, actors, story tellers, physicians, jugglers, goldsmiths, potters, Jain monks, Buddhist nuns, shampooers, gamblers, snake doctors and so on. There were also many women in the group.

For instance , he mentions that among his friends , Candasena and Matrsena were born out of a Brahmin father and a Sudra mother; Rudra, Venibhadra and Narayana were poets; Isana was song writer in Prakrit; Bharata was a composer of songs set to music ; Govinda was a writer; Sudrsti was a reader of letters; Susivana was a panegyrist (an orator who delivers eulogies or panegyrics); Mayuraka was a snake-charmer ; Viravarman was a painter; Kumaradatta was a varnisher; Damodara was, a potter ; Kumaraan was a manufacturer of dolls; Carmkara and Sindhusena were goldsmiths; Jimuta was a drummer; Somila , Grahaditya were singers; Jayasena was a story teller; Madhukara and Paravata were pipers; Darduraka and Tandavika were dance teachers; Sikkhadaka was an actor; Mandaraka was a physician; Akhandalaka and Bhlmaka were dice players (gamblers); Vihamgama was an alchemist; Lohitaksa was a treasure-seeker ; Tamracuda was a shaiva ascetic; Viradeva was a Jain monk; Cakoraka was a juggler ; Karalakesa was a magician ; and Vakaragoha was a snake doctor (Visha vaidya) so on.

There were also many women among his friends. Among them : Mayuraka was the daughter of a forest-man; Anangavana and Suchivana were born in family of Prakrit poets; Chandaka was the seller of betel leaves; Harinika was a dancer; Sudrati was an artist; another Chandaka was a physician ; Karangika was an independent artisan; Keralika was massage girl; Karangika, the maid of honor ; and, Sumati and Cakravakika ( the elderly) were Buddhist nuns.

After the excitement the of a fling at wild and reckless living wore off, Bana set out to take a look at the world; and took along with him a colorful bunch of his friends and his two half brothers. He aimlessly wandered across many countries, in an irresponsible manner.

The good outcome of his travels was that during the sojourn , he studiously attended a number of assemblies (gosthl) of poets and connoisseurs; and, other scholarly circles (mandala). As he said: he paid visits to Royal courts; submitted his respects to ‘the Schools of the wise’; attended ‘assemblies of able men deep in priceless discussions’; and, ‘plunged into circles of clever men endowed with profound natural wisdom’.

Bana gained a great deal of experience during these febrile years of wandering. That gave him a direct experience of life outside of his closed circle. That helped him to gain an insight into life, its nature and an understanding of the many-sided world filled with men and women of various manners of behavior. His travel experiences widened his horizons; enabled him to depict in his works the pictures of varied characters in real life; and, it also ignited the poetic genius latent in him. Bana returned home a much more mature, wiser and determined.

On his return, he was surprised to see his home taken over by host of his relatives; most whom sporting long brown hair like wisps of fire had their forehead besmeared with ashes. Worse still, the house choked with smoke emanating from Homa kunda (fire-altar), was echoing with Vedic chants. The smoke of the clarified butter had darkened the foliage of trees. The backyard of the house marked by hoofs of cows was filled with remains of Kusa grass; and , was littered with pieces of wood and cow dung. The whole ground was rendered brown by the sacrificial offerings.

Inside the house, the floor was littered with puffed rice; nivara paddy rice cakes; mats made of dark deer skins;and, the branches of fig leaves were hanging by the pegs on the wall. At many places, the soma-juice was oozing out of the hollows in the wood. The children with little tufts were running around the house; and, some sat on different sides of the altar watching , curiously, what was going on.

That was rather too much for Bana to take in. He, definitely, was very uncomfortable with the scene as also with the persons who filled it.

Bana, then, promptly went back to his country house in the mango grove outside of the village. His friends were overjoyed with his return, clasped him to their hearts; and, celebrated the joyous reunion by drinking, dancing and singing all night. As Bana said, the reunion with his long last childhood friends was like the joy of the highest release (moksha).

Bana, thereafter, spent some of the most enjoyable days of his life amidst his friends.

One summer afternoon while Bana was lazing under the shadow of a mango tree, a messenger, called Mekhalaka, delivered him a letter from Krishna the brother of King Harshavardhana. In that, Krishna urged Bana to posthaste call on the King who was camping at Manitara. Accordingly, Bana promptly set out meet the mighty ruler. He traveled two days and one night and reached Manitara on the third day; and sought audience with the King. And, that meeting with the King changed the course of Bana’s life, in a very healthy way.

The King, who had heard of the wayward ways of the spoilt youth, was rather reluctant to talk to him. He even tried to reproach the young Brahman for wasting his wealth, heath and youth; and, smearing the fair name of his family.

But, as they conversed, the atmosphere cleared ; the two came to like each other and, became sort of friends. And, in time Banabhatta won the regard of the Emperor who became his patron.

It seems, Bana spent some considerable time with King Harshavardhana.

When Bana later revisited his Prithikuta one autumn, he was besieged by his friends who lustily cheering , demanded accounts of King Harsha, his stay in the Capital and other interesting experiences he had.

To comply with their wishes, Bana tells us, he began writing the great biography of Emperor Harshavardhana. That was how Harshacharita came to be written. Harshacharita narrates Harsha’s rise to power and glory; and ends with his conquest of the world. The work is a sophisticated, erudite display of Banabhatta’s descriptive and poetic genius.

[ Please click here for The Harsa-Carita of Bana; Translated by Edward Byles Cowell and F.W. Thomas; Published under the patronage of The Royal Asiatic Society, London – 1897]

Later on, Banabhatta married and led a happy married life. He settled down in the Court of King Harshavardhana as his poet and confidant,

What rescued Bana from the abyss of depravation were his poetic genius and the moderating influence of his patron King.

Banabhatta’s regret was that he could not complete his Kadambari an intricate work spread over a large canvas. His son , variously called Bhushanabhatta or Pulinda, who by then had grown up, did complete the third and the last part of Kadambari’s elaborate structure .

Bhushnabhatta wrote:

I bow in reverence to my father,

Master of speech.

This story was his creation,

A task beyond other men’s reaches.

The world honoured his noble spirit in every home.

Through him I, propelled by

Merit, gained this life.

When my father ascended to heaven

The flow of his story

Along with his voice

Was checked on earth.

I , considering the unfinished work to be

A sorrow to the good,

Again set it in motion-

But out of no pride in my poetic skill.

(Translation of Prof. Gwendolyn Layne, University of Chicago)

Sources and References

A history of Sanskrit literature – Classical period – Vol. I – by Prof. S. N. Dasgupta

A History of Classical Poetry: Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit by Siegfried Lienhard

Glimpses of Indian Poetics by Prof. Satya Deva Caudharī

Indian Kāvya Literature: The bold style (Śaktibhadra to Dhanapāla) By Anthony Kennedy Warder

Kadambari – translated by Prof. Gwendolyn Layne

http://members.aceweb.com/gwenlayne/Kadambari.intro.pdf

Banabhatta – His Life and Literature by S V Dixit

ALL IMAGES ARE FROM INTERNET