Continued from Part One

[I could not arrange the topics in a sequential order (krama) . You may take these as random collection of discussions; and, read it for whatever it is worth. Thank you.]

Kavya – Rise and Decline

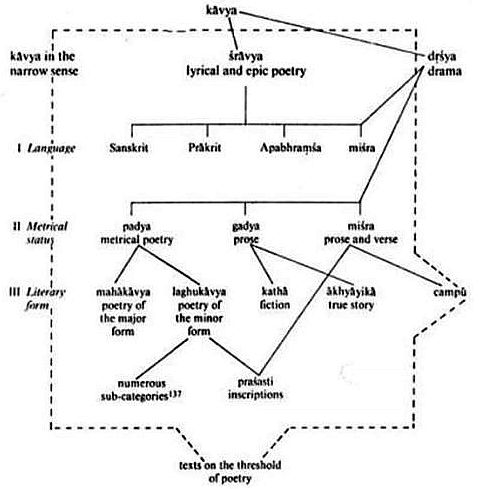

Kavya

Kavya literally means the creation of a Kavi, which term derived from ‘kru-varne’ denotes one who describes; and, it is generally taken to mean a poet. The term Kavi in the Vedic context, however, meant a Rishi, a Drastara (seer) who through his intuition envisions (Darshana) the true nature of entities and their varied states of being (vicitra-bhava-dharmamsa-tattva-prakhya).

Later, according to Yaska, the great Etymologist, the term Kavi came to denote, comprehensively, all those who express themselves through their intuitional (artistic) creations . The creative expression could be through words, color, sculpture, sound, or any other form, so long it flows out of intuition (prathibha) and manifests in an enjoyable form, to the benefit of all beings. Kavitva (poetry) thus , basically , encompasses in itself all forms of art expressions.

sarvāṇi prajñānāni pratimuñcate medhāvī / kaviḥ krānta darśano bhavati vyacikhyapan nākam savitā varanīyah /Nir.12,13/

A hymn in Rig Veda (RV.10.129.4) remarks : it is the Kavi who discovered in his heart, through contemplation, the bond between the Eternal and the transitory . He is the seer krāntadarshi , one who has insight ; can see and grasp the inner significance of things.

sato bandhum asati nir avindan hṛdi pratīṣyā kavayo manīṣā – RV_10,129.04

It was said; a Kavi can even visualize the depths of the ocean (samudre antaḥ kavayo vi cakṣate – RV.10,177.01)

The entire universe is said to mirror in the mind of the Kavi (Mathi-darpane kavinam vishwam prathi-phalathi)

In the world of Kavya (Kavya samasara), the Kavi alone is the King. He can mold it in any manner he wishes.

Apare kavya-samsare kavireva prajapathihi / yathasmai rochate vishvam tathedam parivartate //

[In fact , the concept of Kavi was raised to sublime heights. The Isha Upanishad addresses the Creator of the Universe as the Supreme Poet (kavir manishi paribhuh swayambhuh – Ish Up verse 8) who conceives the grand design and expresses himself spontaneously through his creation. He is the seer, the thinker who expands his consciousness to encompass the entire Universe (viśvā rūpāṇi prati muñcate kaviḥ- RV.5.81.2). The creator, the Kavi, through his all-pervasive consciousness becomes one with his creation.]

In the later times, the scope of the term Kavi was narrowed down to mean an author who creates Kavya. Here also , it was said that one cannot be a Kavi unless one is a seer having the faculty to envision (Darshana) and to see that which is beyond the obvious, lifting the veil of the apparent (Drasta) – Nan rishir kurute kavyam.

Kavya in the sense of poetry during the time of Natyashastra (first or second century BCE) was just an ingredient of Drama.

During the time of Natyashastra, Drama enjoyed the preeminent position; and was respected as being the highest form of art expression. All faculties, right from architecture, stage craft, painting, costumes, makeup and even poetry, music, dance etc were treated as the elements that contribute to a credible dramatic performance. It was only much later that each of these arts developed into independent disciplines gaining more depth and spread.

In the later times, a complete turnaround came about; and, Drama was classified as one of the forms of Kavya. Yet; Drama continued to be the most popular form of entertainment. Kalidasa remarked : ‘Drama, verily, is a feast that is greatly enjoyed by a variety of people of different tastes

– Natyam bhinna-ruchir janasya bahuda-apekshym samaradhanam.

And, for some period of time, Drama was treated as the most delightful form of Kavya – Kavyeshu Natakam ramyam.

Perhaps , the elevation of Drama to the most delightful form of Kavya followed a sort of gradation of poetic experience. It was said; that to include Prose under Kavya might sound good as a rhetorical principle. But, the restrictions of Chhandas, rhyme etc do limit the scope as also the appeal of the prose-Kavyas. And, for similar reasons , just as the metrical Kavya has advantage over prose, so the ‘recited poem’ and Drama have an advantage over metrical Kavya , as they both enjoy the benefit of the musical effects of the sounds that enhance the beauty of presentation, and hence the pleasure of the listener . The Drama scores over the ‘recited poem’ because it has the additional power to bring in the embellishment of spectacular the visual effects; hence, Kavyeshu Natakam ramyam.

But, with the decline of Drama, the Dramaturgy became stagnant after Bharata till about 13th or 14th century, that is until scholars such as Dhanajaya, Sagaranandi, Ramachandra-Gunachadra and Simhabhupa came to its rescue by writing treaties. Among these, Dhananjaya’s Dasa Rupaka is an outstanding work. Dhananjaya condensed Bharata’s vast work; and, treated the whole subject under four broad heads or elements: Vastu (plot); Neta (main character/s); Dasa-rupaka (ten classes or types of plays); and, Rasa (aesthetic enjoyment)

[We have inherited a rich collection of Dramas as also the literature on dramaturgy. More than about five hundred Sanskrit plays, meant for staging, are available. In addition, there are many fragments on palm leaves yet to be edited and published.

Natyashastra (Ca.200 BCE) is of course the most well known text on dramaturgy; and, it is a monumental encyclopedia on all aspects related to drama, dance , music and even Kavya. The varied versions of Natyashastra were followed in different parts of the country.

It appears there were texts on Drama even much prior to Natyashastra. Panini (Ca.500 BCE) the great Grammarian, in his Astadhyayi (4.3.110-11), mentions two ancient Schools – of Krsava and Silalin- that were in existence during his time

– Parasarya Silalibhyam bhikshu nata-sutreyoh (4.3.110); karmanda krushas shvadinihi (4.3.111).

It appears that Parasara , Silalin , karmanda and Krsava were the authors of Bhikshu Sutras and Nata Sutras. Of these , Silalin and Krsava were said to have prepared the Sutras (codes ) for the Nata ( actors or dancers). At times, Natyashastra refers to the performers (Nata) as Sailalaka -s .

The assumption is that the Silalin-school , at one time, might have been a prominent theatrical tradition, particulaly in Mathura of Surasena region. Some scholars opine that the Nata-sutras of Silalin (coming under the Amnaya tradition) might have influenced the preliminary part (Purvanga) of Natyashastra , with its elements of worship (Puja).

Natyashastra itself cites many previous sources, without, of course, specifically naming them.

Between the time of Natyashastra (Ca. 200 BCE) and the Abhinavabharati of Abhinavagupta (10-11th century) there were several authors and commentators on the subject of Drama and related subjects. Some of such ancient authorities mentioned are: Kohala, Shandilya, Kirtidhara, Matrigupta, Udbhata, Sri Sanuka, Lottata, Bhattanayaka and others. But, sadly the works of those savants are lost to us; but, they survive in fragments as cited by the later authors.

However, these texts do point out and confirm that Drama, theater indeed formed a vital and engaging aspect of the Indian society.

But, this thriving performing-art tradition declined over a period and almost faded away by about the twelfth century.

The tradition, though tapering out, did continue in some forms as minor or one-act plays – Uparupakas- mainly in regional languages, with a major input of dance and songs; but, with just a little stress on Abhinaya (acting) and Sahitya (script).]

*

Mammaṭācārya (11th century) explained that Kavya meant poetry, prose , drama, music as also dance i.e. all those forms of art which delight and touch the inner most chord of human sensitivity . That was before; dance and music again branched out.

Kavya is very often translated as poetry. This is rather imprecise, because in Kavya both poetry (Padya) and prose (Gadya) are employed. The two – Padya and Gadya – are also used in Drama , Champu Kavya , as also in technical texts and treatises.

Ideally, Kavya has no restriction of languages or its forms . Kavya need not always have to be in Sanskrit (Marga). It could as well be in Prakrit covering group of regional languages (Desi), including Sinhalese, Javanese. As the scholar Sheldon Pollock says , the languages of the Kavya termed such as Sanskrit, Prakrit, Apabhramsa or whatever , all refer to social and linguistic characteristics and not to particular people or places; and , least of all the structure and internsic merit of the work.

[ While on the question of languages, let me digress here for a while :

There is an interesting contrast between the Western and Indian concepts on the question of language. In the West, one language is used for all purposes. That is in sharp contrast to the Indian practice. A different language for different purposes is the Indian way. That brings in a greater depth and diversity into the cultural milieu of Indian life.

[For instance; say, in America or England, English is the language that almost everyone speaks at home, on the street, in office; and even in the Church. But, let’s say in Karnataka, one may speak Kannada /Telugu / Tulu/ Konkani etc at home as ‘mother-tongue’; use Kannada in the street; speak and submit application to Government and public offices in Kannada the ‘official language’; transact in English at workplace and with outside world; bargain with the meat vendor in Urdu and with the vegetable vendor in Tamil; sing Hindi movie songs; and, recite mantras and prayers in Sanskrit. ]

In ancient India, while Sanskrit was used for learning traditional texts; for intellectual discourses; and, for reciting mantras, it was the Prakrit that was used for popular music, poetry, dance, informal day-to-day conversations, and for simpler instructions. There was also a practice of composing songs with mix of Sanskrit and Prakrit words. Such compositions were named as Mani-pravala (a mix of gems and coral beads)

The Sanskrit drama too, in an attempt to reflect the everyday social behaviour, adopted a multi-lingual approach. The different characters in the play spoke different languages and dialects depending upon their standing in the court hierarchy or their cultural/ regional background.

The Arthashastra does not anywhere specify a particular language as suited to statecraft or as the ‘official language’. The Edicts by the Kings were issued both in Sanskrit and in many other popular languages. There was no concept of National language or National literature.

Buddhism and Jainism which arose in the Eastern parts of India adopted primarily the regional languages of Pali and Magadhi for their texts. In fact, Vac as speech or any language was considered sacred, if it conveys noble thoughts or sacred knowledge.

Coming to the present-day India, with formation of states on the basis of language, we have the three language formula of the Regional language, the official language and the link language. While the Regional languages got bitterly involved in rebelling against the domination of Hindi , the English language gained greater acceptance in almost every field of activity. Now , English has marginalized all the Indian languages – including Hindi – not only as the bureaucratic language, but also as the medium of business, administration, judiciary, scientific studies, medicine, higher education and every other intellectual writing , speech and media.

An unfortunate collateral damage of this mêlée of Hindi Vs Regional languages has been in the decline in the quality, growth and status of every language of India. In the pre-independence era , literary works in Indian languages and even in the dialects had been rich in quality and reached great heights . But, sadly, in the period after Independence , the quality of writing in Indian languages has gone down visibly . In contrast, the English wiring by Indian authors has excelled and gained larger readership across the continents.]

Prakrit

In fact, the early phase of the Kavya was dominated by Prakrit which was spread across many regions of India. It was only towards the end of the first century or the beginning of the second century that the Sanskrit Kavya began to flower in earnestness.

To say a few word about Prakrit; the term is said to be derived from Prakrut, meaning natural (or the original as opposed to Vikrti, the modified) . Another explanation says that Prakrit is the common name given various dialects which sprang up in the early times in India from the corruption of Sanskrit –

(Prakritih , tatra –bhavam tata agatam va Prakritam– Hemachandra 13th century).

The first complete edition of the original text of Prákrita-Prakása – The Prákrit grammar of Vararuchi, with the commentary (Manoramá) of Bhámaha, along with various readings from a collation of six manuscripts, which were stored in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, and in the libraries of the Royal Asiatic Society and the East India House, as prepared by Prof. Edward Byles Cowell, the Professor of Sanskrit in the Oxford University, was published by Stephen Austin, Hertford – 1854.

Prof. E B Cowell, in the preface to his The Prakrit Prakasha (Prakrit Grammar of Vararuchi ) , Turner & Co, London , 1868 says :

Prakrit almost always uses the Sanskrit roots; its influence being chiefly restricted to alterations and elisions of certain letters in the original word. It everywhere substitutes a slurred or a indistinct pronunciation for the clear and definite utterance of the older tongue; and, continually affects a concurrence of vowels, such as is utterly repugnant to the genius of the Sanskrit.

*

An important commentary on Prakrita-Prakasha , the Grammar of Vararuchi ,is that by Bhamaha (10-11th century). He cites two verses in Paisachi from the Brahatkatha, now lost:

Under Sutra 4 : ivasya pi vah / Kamalam piva mukham/

Sutra I4 : hrdayasya hitaakam / Hitaakam barasi me taluni /

Another important Prakrit Grammar is that of Hemachandra of Gujarat (1088-1172)

.

In any case, Prakrit was the language of the common people ; spoken by the social and cultural groups, other than the elite. The earliest known Prakrit Grammar is Prakrita Prakasa ascribed to Vararuchi (first century).

Prakrit is a comprehensive term covering a group of regional languages and dialects. In Vararuchi’s Grammar, only four varieties of Prakrit are mentioned: Maharastri, Paisachi, Magadhi and Suraseni. The later Grammarians expanded the list. Prakrit, thus, would include what is now known as Pali (language of the Tripitakas); Magadhi (language of Magadha) and Ardha-Magadhi (language of the Jain texts); Sauraseni (language of the Matura region) ; Lati( language of Lata the southern region of Gujarat); Gaudi ( language of Eastern India and Bengal) and Maharstri (earlier form Marathi) etc.

According to Prof. Alfred C . Woolner (Introduction to Prakrit , published by the University of the Punjab, Lahore, 1917): The non-canonical texts of the Svetambaras were written in a form of Maharastri , which is termed as Jaina-Maharastri. And, the language of the Digambara cannon, in some respects, resembles Suraseni; and, is termed as Jaina-Suraseni.

*

Because of the lack of strict rules governing these languages they were more relaxed in their nature; and, rather experimental in their usage.

[The Buddhist scholar A. Thitzana in his book Kaccayana Pali Vyakaranam (a translation along with notes and explanations, of the ancient Pali Vyakarana composed by Kaccayana (Snkt. Kathyayana) said to be a close disciple of the Buddha ; and , one who was honored with an an exalted position in the Sangha – Etadagga ), writes : The Sanskrit, Pali and Prakrit are the languages interwoven and intertwined with the ancient Indian society as the linguistic threads in the matter of daily communications and in learning , among diverse communities. It is no wonder, therefore, the Grammar of each language have certain things in common , despite having some distinctive features of their own in many respects.

The Pali Vyakarana (Grammar) written by the grammarian Kaccayana , though to an extent , is based upon and related to the Grammar -tradition of Panini ,is for all purposes an independent work , which has its own style and character . Thus , there are significant differences and independent ways of presentation of its Grammar and its rules.]

Prakrit was also the language employed in the early centuries of literacy (c. 250 BCE – 250 AD.) for public inscriptions and Prashasti (praise-poems), until it was displaced, rather dramatically and permanently, by Sanskrit.

Then there were Paisachi and Apabhramsa two other forms of Prakrit. Paisachi, as Prof. A K Warder explains, was a dialect which appears to have been current, say between fourth century BCE and first century AD, in the region lying between Avanti (Ujjain) and the Godavari basin. Besides that two other explanations are offered to indicate the sources of Prakrit : one mentions the sub-Himalayan region, from Kashmir valley to Nepal/ Tibet; and, the other mentions Kekeya, the region on the east banks of the Indus River.

According to A K Warder; linguistically and historically, Paisachi, Pali and the language of the Magadha-inscriptions form a closely related group representing what may be called early Prakrit that was current between 4th century BCE and second century BCE; early Magadhi also belonged to this group.

[ However, George Abraham Grierson, in his research paper The Pisaca languages of north-western India – Published by the Royal Asiatic Society, London, 1906 , holds a different view:

We are therefore driven to the conclusion that the Modern Paisaca languages are neither of Indian nor of Eranian origin, hut form a third branch of the Aryan stock, which separated from the parent stem after the branching forth of the original of the Indian languages, but before the Eranian languages had developed all their peculiar characteristics. ]

The nouns and verbs in Prakrit forms ( Suraseni, Apabramsa, Magadhi, Ardha-Magadhi and Maharastri) follow that of Sanskrit , with local variations. For instance ; see the various forms of Sanskrit Putra ( son ) and Prakrit Putta :

(Source: :Prakrit / by George Abraham Grierson (1911)

http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen036.htm )

**

[Émilie Aussant , Univ. Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France, writes in her Linguistics in Premodern India:

The most ancient grammar of a Middle Indo-Aryan language known to us is the Prakrata-prakasha, of Vararuci, which was probably written between the 3rd and the 5th centuries. This work deeply influenced later Prakrit Grammarians, those of the Eastern school, that is to say, Purushottama , Ramasarman and Markandeya, who are his direct successors; as also those of the Western (or Southern) School, with Hemacandra at the forefront.

Prakrit grammars mainly differentiate themselves : 1) by the dialect (s) they describe (Vararuci’s Prakrata-prakasha primarily describes the Maharastri- the Prakrit -par excellence; and, devotes a very few Sutras to Paisachi, Magadi and Suraseni) ; Hemancandra’s Sabdanusasana describes Sanskrit, Maharastri, Suraseni, Magadhi , Paisaci, Chulika-Paisachi and Apabramsa. And, 2) by their classification and enumeration .

The Eastern school of Prakrit grammarians is characterized by the following features:

1) the study of the same languages, which are classified as Basha (language mainly used in stage- plays by high-ranking characters); Vibasha (dialects used in stage-plays by low-ranking characters); Apabramsa (dialects spoken by cultured persons and/or used by poets) ; and, Paisahika (dialects used in tales);

2) A large part of these grammars is devoted to Mahrastri, the description of which is the basis for the description of the other Prakrits;

3) Vararuci’s description of Maharastri is strictly followed.

*

The vast majority of Prakrit grammars are written in Sanskrit and are conceived as appendices to Sanskrit grammars, allowing for Prakrit units—which are considered to be modified forms (Vikrti) of Sanskrit—to be formed from Sanskrit .

The Pali grammars, though subject to the influence of Sanskrit grammars—Panini’s Astadyayi, Sarvavarman’s Katantara; Candragomin’s Candra-vyakarana — do not teach Pali-units as modifications of Sanskrit forms, probably because Sanskrit is less important than Pali for the Buddhist communities of the Theravda tradition.

***

From the fragments of Paisachi of the Brhadkatha and those from works of Vararuchi the Grammarian (Ca.1st century) that have survived, it appears, Paisachi resembled what came to be known as Pali, though distinct in minor details. It is said; the Paisachi went into decline mainly because the Shatavahana emperor (around first century BCE and first century AD) totally despised it, calling it low or vulgar Prakrit.

By about the first century, the Prakrit – the intermediate or unclassified – was replaced in speech by a sort of vernacular (Desi) called Apabhramsa (falling away), a vernacular of Western India which achieved literary form in the Middle Ages ; and, was used by Jaina writers in Gujarat and Rajasthan for the composition of poetry. Its chief characteristic is the further reduction of inflexions, which are in part replaced by prefixes, as in modern Indian vernaculars.

Historically , Apabhramsa is treated as the later form of Prakrit; but, rather as a corrupted form of Prakrit. And again, there were several forms of Apabhramsa; and, the major form of it was the one spoken in the Sindhu region, hence known as Saindhava. Some regard Apabhramsa as the early phase of modern Indo-Aryan languages.

According to Prof. Alfred C . Woolner (Introduction to Prakrit , published by the University of the Punjab, Lahore, 1917): The only text of Grammar which describes the literary Apabramsa is the Nagara-Apabramsa, which perhaps belonged to Gujarat. This again, is said to to be related to Varcada Apabramsa of Sindh. Some other forms , such as Dakkani and other dialects of Prakrit are also sometimes styled as Apabramsa.

Most of the texts in Apabramsa belonging to the first millennium (say, up to 1000 AD) are lost. But some fragments or illustrations of Apabramsa lyrics have survived , for instance , in the anthology ( muktaka or kosa) of the Prakrit lyrics of Satavahana ; in the act Four of Kalidasa’s drama Vikramorvasiya ( early fourth century) ; in Puspadanta’s Mahapurana (mid tenth century) ; in Raja Bhoja’s Srñgaraprakasa (eleventh century); and in Chalukya King Someswara’s Manasollasa (twelfth century) . Many of these citations are , in fact , erotic stanzas of a sort familiar to the Prakrit tradition. And they strive to create a rural , homely and amorous ambiance.

Some isolated verses in Apabramsa occur in Jain works; in the tales like Betala Panca-vimshati ; and, also in Prakrita –pingalam , an anthology of about the fourteenth century.

*

As Prakrit gained strength, it branched into independent languages; and, accumulated greater expressive power. At the same time, Sanskrit began to decline steadily and losing its fluidity.

[In fact, Bhartrhari (Ca.450 CE) laments that the social influence of Prakrit was extremely great and was a threat to the historical tradition of Sanskrit Grammar. The schools of Sanskrit Grammar had fallen into disarray; and , in addition study of Prakrit was also flourishing.]

The period spanning between Bharata ‘s Natyashastra (say second century BCE) and the fourth century AD, could be said to be the period of Prakrit, in all its forms. Not only was Prakrit used for the Edicts and the Prasastis (praise-poems), but it was also used in writing poetical and prose Kavyas. The inscriptions of Asoka (304–232 BCE) were in simple regional and sub-regional languages; and, not in ornate Kavya style. The inscriptions of Asoka show the existence of at least three dialects: the Eastern dialect of the capital which perhaps was the official lingua franca of the Empire; the North-western; and , the Western dialects. And much before Asoka, the Buddhist cannon (Tripitaka) and the Jataka tales were written in Prakrit forms, the then spoken language of the people.

The edicts of Asoka employ two types of scripts. The most important, used everywhere in India , except the North-West, was Brahmi; which is normally read from left to right. Local variations of the Brahmi script are evident even at the time of Asoka. In the following centuries these differences developed further, until distinct alphabets evolved. The tendency to ornamentation increased with the centuries, until in the late medieval period the serifs at the tops of letters were joined together in an almost continuous line, to form the Nagari alphabets.

The other script used in the edicts of Asoka was called Kharosthi; which was derived from the Aramaic alphabet, which was widely used in Achaemenid Persia and in the North-West India. The Kharosthi is read from right to left. Kharosthi was adapted to the sounds of Indian languages by the invention of new letters and the use of vowel marks, which were lacking in Aramaic. Kharosthi was little used in India proper after the 3rd century A.D.; but, it survived some centuries longer in Central Asia, where many Prakrit documents in Kharosthi script have been discovered. Later, Kharosthi was replaced in Central Asia by a form of the Gupta alphabet, from which the present-day script of Tibet is derived.

[It is said; the rock inscription of Asoka at Brahmagiri (in Chitradurga District of Karnataka) , though it is etched in the Brahmi script, it is composed in Prakrit language (inscribed from left to right). The person who etched the inscription (Lipikara) , conveying the message of the Emperor Asoka, was Chapada , who hailed from the Gandhara region. At the foot the Edict, Chapada singed his name in Kharosthi language (from right to left) – as Chapadena Likitham Lipikarena .

-

- से हेवं देवानंपिये

- आहा | मातापितीसु सुसूसितविये | हेवमेव गरुत्वं प्राणेसु द्रहीयतवयं | सचं

- वतवियं | से इमे धंमगुणा पवतितवया | हेवमेव अंतेवससिना

- आचारिये अपचायितविये ज्ञातिकेसु च कु य(था) – रहं पवतितये

- पोराणा पकिती दिघावुसे च एसं हेवं एत कटविये |

The practice of etching the message composed in Prakrit language , using the Brahmi script, continued for a considerable period of time. For instance; the kings of the Shatavahana , the Vakataka and the Pallavala dynasties , up to about the end of Fourth Century, followed the same method.]

In the period after Asoka, a number of Prakrit forms came to fore. Here, we find the old Ardha-magadhi, old Sauraseni and the Magadhi, besides Paisachi which perhaps was the language of the Vindhya region. There is an abundance of poetic works composed in Prakrit during the period of Satavahanas (say from 230 BCE to 220 AD). It seems that even during the period between Second century BCE and the First century AD, Prakrit was the language of the Royal Courts. The poetry of this period is represented by the Anthology Saptasataka OR Gatha-sattasai (the seven hundred songs) attributed to King Haala of the Satavahana dynasty (c. third century) ; and by the Brhad-katha of Gunadya (in Paisachi).

The most important literary work in Prakrit is the Saptasataka of the Satavahana King Haala, who ruled in the Deccan in the 1st century A.D. It is a large collection of self-contained stanzas of great charm and beauty, in the Arya metre (Chhandas). Its great economy of words and masterly use of suggestion (Dhvani) would indicate that the verses were written for a highly educated literary audience; but , they contain simple and natural descriptions and references to the lives of peasants and common people , which point to popular influence. The treatment of the love affairs of country folk suggests that Haala may have adopted from widely diffused source in South Indian folk-song traditions.

Further, during the earlier centuries up to 300 A. D., some kings like the Satavahanas, the Ikshwakus and the Pallavas had championed the cause of Prakrit and directed that local languages alone be used in the official and public documents.

Karpura-Manjari by Rajashekhara (Ca.9th century), esteemed for his proficiency in the Prakrit, is a unique play, which is entirely in Prakrit; and, even the King the hero, speaks and sings in Sauraseni Prakrit. In the preliminary to the Drama per se, the Sutradhara (stage-manager) muses aloud : Why has this poet totally abandoned Sanskrit ; and, used only the Prakrit in the play? His assistant , who is by his side, replies in Maharastri : Sanskrit poems are harsh ; but, a Prakrit poem is smooth and easy to sing. The difference between the two is as that between a mirthless man and a pleasant woman.

The Karpura-Manjari, in its four Acts (Javanikantara), narrates how king Candapala eventually succeeds in marrying the beautiful Karpura-Manjari, the daughter of the Kuntala King ; and, thus becomes a paramount sovereign.

The fame of Rajashekhara rests firmly on his play Karpūra-Mañjarī, which, it is said, to please his wife, Avantisundari, a woman of taste and accomplishment.

*

However, as the period advanced , the Prakrits ceased to be used for public documents; and, even the Buddhists and the Jains disregarded the advice of the founders of their religions and began to compose works in Sanskrit. There were also not many Prakrit plays in the latter periods.

**

Rise of Kavya

The Arthashastra ( dated somewhere between 150 BCE – 120 CE) which reflects the conditions obtaining in the Royal Courts of its time mentions a host of Court employees such as : Sutas, Puranikas, Magadhas ( those who herald ) and Kusilavas (chroniclers , bards and singers) . There is even the mention of monthly honorariums granted to teachers and pupils (Acharyah Vidyavantas cha). But, strangely, there is no mention of a court poet. And, among the literary works mentioned in Arthashastra there is no mention, anywhere, of Kavya. Further, no Kavya of note belonging to the period between the 2nd century B.C. and the early 2nd century A.D. has come down to us.

It was perhaps towards the end of this period that the Kavyas seemed to develop. The Buddhacharita, the Kavya of Asvaghosa (Ca. First century); the plays of Bhasa (First or Second century) belong to what could be called as the pre-classic period of early ornate Kavya period. These are perhaps the earliest known Kavya-poets of eminence. And, Kavya as ornate court poetry perhaps blossomed in the courts of Western Ksatrapas (35–405) who ruled over the western and central part of India; and, during the reign of Kushanas, particularly in the second century AD. But, the dates of the works of this period cannot be ascertained with any certainty.

The later Sanskrit writers tried to bring in the informal flavor of Prakrit into their works. (And, another reason could be that the Sanskrit authors too had to come to terms with the changes taking place within the society they lived.) Some major writers such as, Kalidasa, Bhavabhuthi, Dandin, Vishakhadutta and Banabhatta made some of their local characters speak in Prakrit, just to usher a sense of reality into their dialogues. Dandin went a step further by grafting a theory of Riti, by legitimizing the Prakrit influence on Sanskrit. Writers like Rajashekara, Hemachandra, and Jayadeva, though scholars of Sanskrit coined fresh Prakrit terms and phrases for expressing new ideas. Thus, whatever may have been their original regional specificity, by the time of Bhamaha and Dandin ( 6-7th century) both the literary Prakrit and Apabhramsa were no longer treated as tied to a particular place; but , were regarded as varieties of languages in their own right.

Therefore, Anandavardhana (Ca. 850) while drafting a new theory of Kavya made use of materials that had not been previously subjected to critical scrutiny. And, among such material were the Prakrit songs (gatha) from perhaps the second or third century. It is said; the informal and sensitive Prakrit lyrics helped Anandavardhana to appreciate how the meaning of the work as a whole resides in an emotional content (Rasa); and, how that can be effectively communicated only through suggestion (Dhvani).

And, Kshemendra (mid eleventh century), also from Kashmir, advises the aspiring poets of talent to “listen to the songs and lyrics and rasa-laden poems in local languages . . . to go to popular gatherings and learn local languages,”

For a short period, there was a practice among the writers to compose Kavyas both in Sanskrit and in Prakrit. For instance:

:- the lexicographer and poet Dhanapala, son of Sarvadeva, who lived at Dhara , the capital of Malava, was the author of the Paiyalacchi, a Prakrit vocabulary, completed in 972-973 A.D, and after his conversion to Jainism, he composed Rsabha-pancasika, fifty verses in Prakrit, in honor of Rsabha Deva, the first Thirthankara ;

:- Rajasekhara (who lived about the year 900 A. D) , the author of Kavyamimsa, composed a play called Sattaka, same as a Natika or minor comedy , wholly in Prakrit;

:- Dhanika son of Visnu, (last quarter of the tenth century), who prepared a commentary on the Dasarupa not only wrote poetry in Sanskrit but also in Prakrit;

:- Visvanatha (first half of the fourteenth century), a literary theorist, wrote one Prakrit Kavya besides his Sanskrit works; and

:- Anandavardhana, in addition to a courtly epic in Sanskrit, wrote a text in Prakrit “for the education of poets” , most likely a textbook on aesthetic suggestion.

Muñja, king of the Paramaras who was Raja Bhoja’s uncle (Ca. 996), appears to be the only Sanskrit poet who produced a serious body of verse in Apabhramsa as well as in Sanskrit (both preserved only in fragments).

Although the number of Prakrit Kavyas tapered out, popular tales, songs and verses set in simple, natural and delightful styles continued to be composed in good numbers. For instance; Kouhala (Ca.800), in his delightful Maharastri romance Lilavali, pictures a conversation between a youth and his Love. She goads her lover to narrate a tale. The helpless young man pleads his ignorance: “Ah, my love, you will make me look ridiculous for my lack of learning in the arts of language. Far from telling a great tale, I should in fact keep silent.” She does not give up , but cajoles him : “Oh , come my beloved , tell me any story in clear Prakrit that I can understand. Why do we need to care for rules and heavy words? So tell me a delightful tale in Prakrit, easy to understand which simple women love to hear. .”

In the biography of Yasovarman of Kanyakubja (Ca. 725) the poet defends the virtues of Prakrit, saying: “From time immemorial in Prakrit alone, that one could combine new content and mellow form. . . . All words enter into Prakrit and emerge out of it, as all waters enter and emerge from the sea”. And, he laments “…. many men no longer understand [Prakrit’s] different virtues; great poets [in Prakrit] should just scorn or mock or pity them, but feel no pain themselves.”

The golden age of Kavya

The golden age of ornate court Kavya was the stretch of about 125 years (from 330-455) during the reign of the Gupta dynasty (approximately between 350 and 550 AD). This was also the age of Kalidasa (say, between 375 and 413 AD) – acknowledged as the greatest of poets. The other great poets and scholars said to belong to this golden age of the Gupta Era were : Matrgupta; Mentha or Hastipaka; Amaru. They were later followed by other distinguished poet–scholars like Bhartrihari (450-510); Varahamihira (505-587); Bhatti (about 600 AD); and, Bharavi (Ca.6th century) .

Then there was the Emperor Harsavardhana of Thanesar and Kanauj who ruled from 606 to 647 AD. And, Banabhatta his Court poet immortalized his patron in his historical romance Harshacharita. And, Magha (Ca. 7th century) a poet in the Court of King Varmalata of Sharmila (Gujarat/Rajasthan) created undoubtedly one of the most complex and beautiful poetic works, the Shishupala-vadha. He was followed by Bhavabuthi the playwright and poet in the court of the King Yashovarman of Kanauj (Ca.750 AD).

Around the seventh century , the convention was invented (and quickly adopted everywhere) of prefacing a literary work with a eulogy of poets past (kaviprasamsa). Bana, author of the Harsacarita (c. 640), the first Sanskrit literary biography that takes a contemporary as its subject, seems to have been the first to use it. This is not to say that earlier writers never refer or allude to predecessors. In a well-known passage in the prologue to Kalidasa’s drama Malavikagnimitra, an actor complains to the director, “How can you ignore the work of the great poets—men like Dhavaka, Saumilla, Kaviratna— and present the work of a contemporary poet like Kalidasa?” to which the director famously replies, “Not every work of literature is good just because it is old, or bad just because it is new.”

(The Old is not necessarily admirable; and the New always not despicable; the wise discriminate and decide; fools let others decide for them. – Kalidasa, Act-I, Malavikagnimitra)

Such kaviprasamsa-s, apart from paying homage and expressing one’s appreciation of the past-poets , served other purposes as well. To start with, it was a way of educating the present generation about the past Masters, even those who have faded out of peoples’ memory.

It was also indicative of the author’s affiliation to a linage (parampara) of his predecessors. For instance; Bana’s praise-poems or Eulogy (kaviprasamsa) offers a broad view of the main varieties of Kavya that were current during his time; the foremost representations among each of those varieties that the author he appreciated most. Bana’s tributes to his elders include : in the class of the tale (katha) in Sanskrit prose (or Prakrit or Apabhramsa verse) was the Sanskrit work Vasavadatta of Subandhu (c. 600); in the prose biography (akhyayika) , it was the lost Prakrit work of Adhyaraja; in the Sanskrit court-epic (mahakavya) , it was , of course, Kalidasa ; and, in the class of Prakrit court-epic (skandhaka) , it was Pravarasena ; in the Sanskrit, Prakrit, or Apabhramsa lyric or anthology of lyrics (muktaka and rosa), it was the Prakrit collection of Satavahana; and , in the drama (nataka) it was indeed the match-less Bhasa .

And, amidst the conspicuous absence of any sort of Literary Criticism in the early periods of Kavya, such kaviprasamsa-s , as of Bana , provide a glimpse or a window-view into the standards that the authors adopted to form literary judgment over their predecessors works. It was also indicative of the values and merits that the writer himself cherished to look for in a Kavya. And, yet the criteria for selection the work were not clearly stated. Some of those virtues could perhaps be : the beauty , elegance , charm of the language; command over the language that splendidly brought out just the right meaning that author intended ; lucid and sparkling expressions and phrases; the emotive content; vivid descriptions that graphically captured the locale as also the mood of the situation; the delight(Rasa) that it provides to the reader; and, the ways that the Kavya benefits the reader (Kavya-prayojana).

Having said that let me also mention that such kaviprasamsa served only a limited purpose. It was, at best , an appreciation; not an appraisal of the literary merits of a Kavya or its elements such as the plot, characterization, or voice (Dhvani ) etc. It did not also give even a clue to the chronology of the authors or the works.

[ A practice of Prarochana , sequenced right after the Naandi (seeking the blessings of the Devatas for successful completion of the play and to bring joy (nanda) to the audience and to the gods : Nandati devata asyam iti Naandi) ; but, before the Prastavana , the prelude to the commencement of the play proper, became a common feature of Sanskrit plays , particularly after the time Bhasa ( 3rd or 4th century). In the Prarochana , the Sutradhara would praise the literary merit and scholarship of the playwright and laud the high quality of his play that the audience is about to watch .

The Prarochana was , of course , just a manner of introducing the play and playwright while welcoming the audience . You could call it a ‘ promotion’ of the play; and, it did not mention the past luminaries.]

With the passing of those wonderfully well gifted, creative, brilliant poet-scholars, the golden age or the classical age of Kavya may be considered to have come to an end.

Rise of Sanskrit

The rise of Sanskrit as a medium of Kavya and other forms of literary works, and the fall of Prakrit are in some way related.

With the establishment of mighty Empires that stretched from Afghanistan in the West to the far ends of the East, the power and influence of Indian Empire, its culture, art, philosophy and literature spread across to the lands beyond the Himalayas and across the seas.

The religious scholars, particularly the Buddhists from China, Tibet and Far East traveled across many regions of India to study and to gather texts to be later translated into their own languages. Their medium of study was invariably Sanskrit, which was written and spoken by most Indian scholars, in almost the same manner. One could say that Sanskrit was India’s language up to about the tenth century. It was in Sanskrit that Indian scholars discussed with the visiting scholars; and, it was also the language of its international diplomacy.

From the second century, and increasingly thereafter, Sanskrit came to be used for public texts, including the quite remarkable Kavya-like poems in praise of kingly lineages (Vamshavali). Prior to that , for about four centuries , say from 250 BCE it was only the Prakrit that was used for inscriptions, whether for issuing a royal proclamation, glorifying martial deeds, commemorating a Vedic sacrifice, or granting land to Brahman communities.

Similarly, the early Buddhist Canon containing the discourses delivered by the Buddha and other Buddhist texts say up to first or second century of the Common Era were in Pali, a form of Prakrit. Likewise, the religious texts of the Jains were composed mostly in Ardha –Magadhi, also a form of Prakrit. These and others, in general, began to adopt Sanskrit for both scriptural and literary purposes.

Later, after the second century AD, large number Buddhist scriptures came to be written in Sanskrit (although the Buddha had insisted that his teachings be in the language spoken the common people). And, thereafter it became a practice to compose texts in Sanskrit. By about the Middle Ages, considerable numbers of eminent Buddhist scholars , who wrote their religious or secular texts in Sanskrit, had gained renown across all Buddhist countries . Just to name a few: Dharmakirti (c. 650); Ratnasrijñana (900); Dharmadasa (1000?), Jñananasrimitra (1000) and Vidyakara (1100).

The Jains who earlier composed their texts in a form of Prakrit also switched over to Sanskrit. For instance, take the case of Jains in Karnataka who created great Sanskrit poetic works like Adipurana of Jinasena , the Champu Kavyas ( mix of poetry and prose) of Somadevasuri and Prince Yasotilaka. At the same time , they wrote new work in Kannada (Pampa’s courtly epics of the mid-ninth century) and Apabhramsa (Puspadanta’s Mahapurana of 970).

The reasons that prompted the writers, even those writers on philosophy and religion, were many ; but, mostly , they were related to the changed circumstances and the eminent position that Sanskrit had secured, by then, not only in India’s neighboring countries but also in the far off lands. Sanskrit had extended far beyond the Sub Continent, into Central Asia and as far as the islands of Southeast Asia.

At the same time, neither Prakrit nor Apabhramsa, nor any of the regional-language literature, could command such wide readership or audience. They were in no position to compete with Sanskrit, internationally. Although works of great merit were produced in these languages, they could not reach the readers beyond the limits of their vernacular world. They were hardly known in the outside world.

[ In a way of speaking, in terms of the literary and spoken means of communication in the present-day India – internally and internationally , English could be said to have replaced Sanskrit. And, in the visual media , Bollywood movies enjoy a wider reach and greater appeal than the regional films (however well they might be made)]

The Sanskrit works, on the other hand, enjoyed readership even outside India. For instance; the works of the great Buddhist Sanskrit poets, such as, Asvaghosa (second century) and Matrceta (not later than 300), were read not only in Northern India but also in much of Central Asia. In Qizil and Sorcuq (in today’s Xinjiang region of China), manuscript fragments were found bearing portions of Asvaghosa’s dramas and his two courtly epics, Saundarananda and Buddhacarita.

Such wide range of circulation was possible not merely because of the influence that Buddhism commanded in those countries, but also because of the universal acceptance of Sanskrit language and recognition of its aesthetic power and beauty.

The non-religious Sanskrit poetry spread as far as up to Southeast Asia, where by the ninth or tenth century at the latest, literati in Khmer country were studying masterpieces such as the Raghuvamsa of Kalidasa; the Harsacarita , the early-seventh-century prose of the great writer Bana; and , the Suryasataka of the latter’s contemporary, Mayura.

Therefore, any writer of merit – whether religious or secular – aspiring for wider readership, more serious attention and greater fame, naturally opted to write in Sanskrit. And, his Sanskrit work had a better chance of acquiring an almost global readership and following among erudite, aesthetic Sahrudaya –s.

Therefore, the desire to reach out to a larger audience and to acquire recognition from the worthy peers , seems to have prompted aspiring writers to compose in Sanskrit . Such works covered a wide range of subjects – from Grammar, Chhandas, Alamkara, and poetic conventions to study of character, narratives, plots, and the organization of elements that create the emotional impact of a work – such as Rasa etc.

*

Dr. Victor Bartholomew D’avella writes in his astonishingly well researched very scholarly Doctoral Thesis : Creating the perfect language : Sanskrit grammarians, poetry, and the exegetical tradition

It is often routinely said that the Sanskrit was codified by Pāṇini and Patañjali . Although this might be true to a certain extent; this was hardly the case throughout much of Sanskrit’s long history.

There is a very complex network of scholars , in each generation, striving to determine what correct Sanskrit is. The intricacy of these debates increases rapidly ; because, almost every step along the way is another interpretative choice that requires further justification. It is not only necessary to decide what the constituent elements of a word are; but also , how to understand the sūtras that could potentially account for it.

For many Sanskrit grammarians, the status of Sanskrit had a number of parallels — other modes of speech were comprehensible ; but, correct grammar played an important role in the admittance to, and admiration from, certain communities — yet also differences in so far as we find statements about acquiring dharma , “merit,” through the use of śuddha , “purified,” or sādhu , “correct,” speech beginning in the Mahābhāṣya .

This added dimension incorporates grammar and the linguistic purity ; and, it regulates into the larger system of dharma -oriented activities . Several of the texts provide further testament to these assertions.

**

Prof. A.S. Altekar in his Education in Ancient India ; Published by Nand Kishor & Brothers, Benaras – 1944; talks about the neglect, of Vernaculars following the ascendancy of Sanskrit

The revival of Sanskrit that took place early in the first millennium was undoubtedly productive of much good; it immensely enriched the different branches of Sanskrit literature which began to reflect the ideals and ideas of the individual and the race. But owing to the deep fascination for Sanskrit, society began to identify the educated man with the classical scholar.

But when the best minds became engaged in expressing their thoughts in Sanskrit, Prakrits were naturally neglected. As long as Sanskrit was intelligible to the ordinary individual, this was not productive of much harm. But from about the 8th century A.D. Prakrits and vernaculars became widely differentiated from Sanskrit, and those who were using them began to find it difficult to understand the latter language. Hindu educationalists did not realize the importance of developing vernacular literature in the interest of the man in the Street.

Hence, the Hindu educational system was unable to promote the education of the masses probably because of its concentration on Sanskrit and the neglect of the vernaculars.

*

Decline of Kavya

Though Sanskrit in some form or other lingers on in today’s India, what is undeniable is that it’s vital signs have grown very weak.

The reasons for the rapid decline of Kavya are many; and, some of them complement each other. Perhaps the most telling blow was the political instability and virtual anarchy in North India following the invasion of Muslim forces starting from the tenth or the eleventh century. The Royal Courts and the systems that supported the growth of Kavya were totally destroyed; and were never revived. The Kavya and its creators were truly orphaned.

And, even when the Sanskrit poets secured patronage in some Royal Courts, their Kavya became inward looking and dispirited, having lost connection with the society at large. Virtually all the Court poetry was about caritas (poetic chronicles) , vijayas (battles fought and won ) , or abhyudayas (accounts of success), detailing this campaign and that military victory. The poets, as paid employees of the Court, were duty bound to praise their Masters.

Sheldon Pollock in his very well researched and presented scholarly work Sanskrit Literary Culture from the Inside Out , examines the state of Kavya in the later times with particular reference to the Courts at Kashmir , Vijayanagar and Varanasi. I will try to summarize his views, briefly.

Sanskrit literary culture in Kashmir, commenced by about the sixth century; and by the middle of the twelfth century it reached its zenith, with more innovative literature being written than perhaps anywhere else in the region. By the end of the twelfth century , the orderly life in urban Kashmir suffered near total dissolution. And, after the establishment of Turkic rule in Kashmir, around 1420, the literary culture was totally shattered. No Kashmiri Sanskrit literature was ever again created or was it circulated outside the valley, as it used to do. Many of its important literary works survived only through recopying in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; but, virtually all of those originated from the twelfth century or earlier.

As regards Vijayanagar (1340–1565) in Karnataka, though the Literature, in general, did enjoy Royal patronage, the energy of Sanskrit Kavya slowly depleted. In Vijayanagara, Sanskrit was not dying rapidly as it did in Kashmir. Sanskrit learning in fact continued during the long existence of the empire, and after. But, the spirit of the Kavya was somehow lost. Vijayanagara’s Sanskrit literature, as Sheldon Pollock says, presented a picture of an exhausted literary culture. It seemed as though the Court culture insulated the poets from the simple pleasure and pains of the ordinary day-to-day life of common people. Their poetry was mostly about singing the glory of their Royal patrons. Such Sanskrit poetry was socially irrelevant; but was supported by Court as sort of state enterprise.

Of the Sanskrit literary works of the Vijayanagara times, with rare exception, not a single one is recognized as great, and continued to be read after it was written. Most of its Kavyas were did not circulate to any extent beyond its region; nor did they attract serious commentaries, nor included in a credible anthology.

In contrast, the literature in regional languages – Kannada and Telugu- flourished during these times. For instance; . Kumaravyasa’s Kannada Bharata (c. 1450) not only circulated widely in manuscript form but also continues to be recited all over the Kannada-speaking world, as the Sanskrit Mahabharata itself had been recited all over India a thousand years earlier.

The Maratha court of Tanjavuru in the early eighteenth century was an active cultural centre in the South. Its Sanskrit scholarship as also that in regional languages was indeed of a high order. But, the Sanskrit literary production, while prominent, appeared to have remained wholly internal to the palace. Not a single Sanskrit literary work of the period transcended its moment in time.

In the south as in the north, Sanskrit writers had ceased to make literature that made history. The Kavya of these later times seemed have been drained of vitality. There seemed to be neither enterprise nor enthusiasm. What was strange was that the authors of Court-epics did not show much zeal to invent fresh themes. Most found it adequate to re-narrate the familiar myths and legends in their own characteristic styles.

As Sheldon Pollack puts it : Sanskrit literature ended when it became a practice of repetition and not renewal, when the writers themselves no longer evinced commitment to a central value of the tradition and a feature that defined literature itself: the ability to make literary newness, “the capacity,” as a great Kashmiri writer put it, “to continually re-imagine the world.”

**

Dr. Buddhadeva Bose (1908-1974) , regarded as one of the five poets who moved to introduce modernity into Bengali poetry, in his Modern Poetry and Sanskrit Kavya, writing about Kalidasa says though he admires Sanskrit greatly , ‘ the truth is , no real connection has been established between our way of life today and Sanskrit literature…. The Sanskrit poetry is comprehensively artificial; and, no longer represents or speaks to, the intimate concerns of the modern reader.’ He asks : ‘how do we read Sanskrit poetry as poetry , if it fails to provoke the intellectual and emotional response that draws us to poetic language; in other words, if it fails to fulfill our expectations about poetry’. Further he says : ’ In the whole world , only Sanskrit has been turned into a huge and much respected corpse , which cannot be approached without our first having mastered the technique of dissection. This is the main reason for our alienation from Sanskrit poetry’.

*

Prof. Bhupendra Yadav in his article Decline of Sanskrit – writes:

The blame for Sanskrit’s decline lies not in the manner the new curricula framework has been drafted, but in its very “complexity” that for long made it inaccessible to a majority of the population

It is wrong to argue that Sanskrit has lost importance because the new NCF does not give it “it’s due”. The decline of Sanskrit had set in much earlier. The intricacies of Sanskrit language have made it difficult to comprehend of most Indian languages though the rich literature in Sanskrit is the fount of our cultural heritage. Hindu religious ceremonies are impossible without the recitation of mantras in Sanskrit. Yet, Sanskrit is not our link language. It is, however, listed as one of our 18 “national languages” in the Constitution’s Eighth Schedule. Sanskrit acquired a grammar even before classical literature (like the works of Kalidasa) ; and, epics (like Ramayana and Mahabharata) were written in Sanskrit. Ancient Sanskritists made Sanskrit obscure more than two thousand years ago. Consequently, Sanskrit failed to be the mother tongue of any significant section of society with less than 50,000 people owning it as their mother tongue in 1991.

Calling Sanskrit a Deva-basha caused it more harm than good . And, Sanskrit has been turned into a “heritage site” ; and, like all such items, Sanskrit has everyone’s respect but no one’s support on crucial occasions, like when the lingua-franca was decided in the Constituent Assembly of India in 1949.

*

However , Dr. Kunhan Raja feels all is not lost ; and, it is not as bad as it is made to look.

Kunhan Raja (1961:2-3) writes that among the languages that started developing a literature in the pre-Christian era, Sanskrit is the only one that continues as a living language. The languages of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Syria and Carthage are only historical names now. The Chinese and Greek of those early days have changed and hence, in – comprehensible. But; Sanskrit has continued substantially the same throughout these millennia. Vedic texts are intelligible to those who know modern Sanskrit

[Please check here for a collection of articles concerning the studies of Sanskrit undertaken in various parts of the world, in countries outside India, covering a vast range of texts and topics pertaining to the Vedic lore, Buddhism, Jainism, Indian philosophy, art, archaeology, epics , classics, literature and literary criticism.]

*

Literary criticism

The practical literary criticism of the type that we are familiar with today, discussing and analyzing issues such as the plot, catheterization, style of presentation, poetic content, its freshness , arrangement of chapters, the validity of the work etc did not for some reason develop in the Kavya tradition. The references to to earlier works would either to praise them very highly (Kavai-prashamsa) or to condemn it outright. The sense of balance in their approach somehow seemed to be lacking.

Prof. Sriramamurti of Andhra University , in his paper ‘Critic and criticism in Sanskrit‘ observed that even in the present period : The utter lack of practical criticism is a sad omission on the part of Sanskrit writers. This has led to the recent tradition of studying only portions of Maha kavyas and never looking at them as single artistic pieces. Hence we were unable to get at the spirit of the poem, much less to receive the message intended to be conveyed by the immortal poets of our literature.

Question of the sense of History

Then there is the question of the sense of History. It is not that the ancient Indian authors did not have taste for history; but, they did not seem to cultivate taste to chronicle the historical events and facts objectively. Although Bhamaha (early seventh century) drew a distinction between historical and fictional genres (akhyayika and katha), such distinction was hardly ever maintained. In the Indian tradition, the historical writing was usually a branch of Kavya. For instance, the Rajatarangini by Kalhana (Ca.1150) which chronicles the Royal linage of Kashmir is regarded by some as History. But Kalhana himself explicitly identifies his work as a Kavya; and , he affiliates it with literature by frequently citing earlier poems that had achieved the synthesis of literature with History. Moreover, the work was regarded as literature by his contemporaries.

What was surprising was that Anandavardhana (Ca. 850) counseled poets to alter any received historical account that conflicted with the emotional impact they sought to achieve. Thus, according to him, one can and should change fact to suit the dominant Rasa of the work.

The problem appeared to be that Chronology was malleable and was horribly mixed up. And, the events were not sequenced in the order they occurred. The other was the woeful lack of the critical approach. The ancient authors did not seem to cultivate taste for criticism of the historical truths.

The reason for such flexible approach could be that the author would invariably be serving as an employee of the King as his Court poet, who was asked to write the about the glory of his King’s ( patron’s) predecessors. In the circumstances, the Poet would not go into analysis of the circumstances, critically examine historical facts; but, was duty bound to praise his patron and his ancestors. And, while writing the ‘History ’ (itivritta of heroes of the Nayaka), the poet would also try to exhibit his poetical skills in extolling his subjects by treating them as heroes (Nayaka) investing them with unbelievable virtues . And, in the narration , he would also try make room to entertain and to instruct as a Poet, to teach morals and to generalize the course of human destiny.

Some examples of the works of this genre are Banabhatta’s Harshacharita (7th century) about the life and times of King Harshavadhana ; Vakpathi’s Prakrit work Gavdavaha ( 8th century) about King Yashovardhana of Kanauj; and, Bilhana’s Vikramankadevacharita (12th century) woven around the dynasty of Chalukya kings , and specially about his patron Vikramaditya VI.

Bilhana, in particular, rewarded his patron by mixing mythology with the chronicles of the Chalukya dynasty. He makes an epic out of a historical theme. He commences with the allusion to gods who out of benevolence create the Chalukya dynasty in order to ensure and maintain safety of the world.

[ The efforts to eulogies, singing the praise of the patrons to the skies, extended even to inscriptions etched on rocks and pillars . The earliest and the most elaborate example of such laudatory inscriptions is the one scripted by Kubja Kavi (Kubjasva kavyam idam shamtale lilekha). The inscription carved vertically on the shaft of the pillar, dated around the fifth century, is located in the Talagunda village of Shivamogga district, Karnataka. It was set up in the time of the Kadamba king Śāntivarma (c. 455-60)

The efforts to eulogies, singing the praise of the patrons to the skies, extended even to inscriptions etched on rocks and pillars . The earliest and the most elaborate example of such laudatory inscriptions is the one scripted by Kubja Kavi (Kubjasva kavyam idam shamtale lilekha). The inscription carved vertically on the shaft of the pillar, dated around the fifth century, is located in the Talagunda village of Shivamogga district, Karnataka. It was set up in the time of the Kadamba king Śāntivarma (c. 455-60)

In a very scholarly, beautifully crafted meticulous inscription, running into thirty five stanzas, composed in chaste and refined Sanskrit, employing nine types of Chhandas (meters) , the poet Kubja sings the glory and eminence of the ancestors of his patron Santivarma; particularly that of the founder of the Kadamba dynasty, King Mayura Varma (r.345–365 C.E.) , elevating them to the level of gods and demigods. He also spins a fanciful tale vividly describing and extolling the valor and generosity of the youthful King Mayura Varma.]

Continued in Part Three ->

Sources and References

I gratefully acknowledge these and other wonderfully well researched works of great merit

Glimpses of Indian Poetics by Satya Deva Caudharī

Indian Poetics (Bharathiya Kavya Mimamse) by Dr. T N Sreekantaiyya

Sahityashastra, the Indian Poetics by Dr. Ganesh Tryambak Deshpande

History of Indian Literature by Maurice Winternitz, Moriz Winternitz

A History of Classical Poetry: Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit by Siegfried Lienhard

Literary Cultures in History by Sheldon Pollock’

what is kavya

The efforts to

The efforts to

Sri Ambi Dikshitar initiated and guided Smt. D. K. Pattammal in singing Dikshitar’s Kritis. He was also the teacher of the renowned musician – Artist Shri S. Rajam who popularized rendering of Dikshitar’s Kritis over All India radio Madras. Shri Rajam also presented pictorial representations of many of Dikshitar’s Kritis.

Sri Ambi Dikshitar initiated and guided Smt. D. K. Pattammal in singing Dikshitar’s Kritis. He was also the teacher of the renowned musician – Artist Shri S. Rajam who popularized rendering of Dikshitar’s Kritis over All India radio Madras. Shri Rajam also presented pictorial representations of many of Dikshitar’s Kritis.

Thanks to the continued patronage of the Rajah, the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini was completed in the middle of 1904, after four years of hard work. Its types for Telugu and for the Gamaka-signs were ordered and specially made. The credit for having printed this very difficult material at a time when printing in this country was in its infancy goes to Sri T. Ramachandra Iyengar and the Vidya Vilasini Press at Ettayapuram. The book was published under the authority of Rao Bahadur K. Jagannathan Chettiar, Secretary of the Ettayapuram Samsthanam. It was doubtless one of the most authentic documenters of Indian music and musicology.

Thanks to the continued patronage of the Rajah, the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini was completed in the middle of 1904, after four years of hard work. Its types for Telugu and for the Gamaka-signs were ordered and specially made. The credit for having printed this very difficult material at a time when printing in this country was in its infancy goes to Sri T. Ramachandra Iyengar and the Vidya Vilasini Press at Ettayapuram. The book was published under the authority of Rao Bahadur K. Jagannathan Chettiar, Secretary of the Ettayapuram Samsthanam. It was doubtless one of the most authentic documenters of Indian music and musicology.