Continued from Part Eighteen – Lakshana Granthas– Continued

Part Nineteen (of 22 ) – Lakshana Granthas – Continued

14. Venkatamakhin – Chatur-dandi-prakashika – Mela and Melakarta

Venkatamakhin also referred to as Venkateshwara Dikshita and Venkatadhvari was the son of Govinda Dikshita, the author of Sangita Sudha and the minister of the Nayak Kings at Thanjavuru.

Venkatamakhin was said to be a distinguished Mimamsa scholar; and, is credited with Karmāntha Mimamsa, a work on the Mimamsa and Vrittikabharana, a commentary on Kumarila Bhatta’s work. Venkatamakhin is also said to have composed twenty four Ashtapadis on Lord Tyagaraja, the presiding deity at Tiruvarur temple.

Venkatamakhin shows enormous respect towards his father Govinda Dikshita, mother Nagamba and his elder brother Yajnanarayana Dikshita. He mentions that his elder brother Yajnanarayana Dikshita taught him Tarka (Logic), Vyakarana (Grammar) and Mimamsa Shastra, as also Music. Yajnanarayana Dikshita, who also was in the service of Raghunatha Nayaka, was a renowned scholar of his times. He is said to have written a play Raghunatha-Vilasa and a Champu-kavya Raghunatha Bhupa Vijaya in honor of the King. Apart from that, Yajnanarayana Dikshita is credited with Shitya-Ratnakara a treatise on Sanskrit literature and Grammar.

Neelakantha Dikshita a minister in the Court of Nayak Kings was a disciple of Venkatamakhin. Neelakantha Dikshita was also a well known poet of his times; and is said to have written a Kavya Siva Leelarnava, which describes the Leelas of Lord Sri Meenakshi Sundareswara of Madura.

[The picture at the top of this post is taken from a painting made by Sri S Rajam. There is an interesting anecdote connected with it. When Sri Rajam intended to provide an illustration of Venkatamakhin as an introductory painting for the Apr 2008-March 2009 calendar brought out by L&T, he had no earlier pictures of Venkatamakhin to guide him. His research into the archives of Sri Kanci Mutt led him to an interesting detail showing that Venkatamakhin who was also a skillful vainika wore his long hair in a coil such that it did not touch his body; he coiled it atop his head. Shri S Rajam then pictured Venkatamakhin with coiled locks of hair, rudraksha-mala; and surrounded by musical instruments such as Veena, Tambura etc. as also scrolls of ancient manuscripts, lending the picture an air scholarship and a spiritual aura.]

Chatur-dandi-prakashika

Venkatamakhin fame rests mainly on his work Chatur-dandi-prakashika, which he wrote (perhaps around the year 1650) under the patronage of the Fourth Nayaka King Vijaya Raghava who succeeded Raghunatha Nayaka and ruled up to 1672.

Chatur-dandi-prakashika is a treatise on Music that illumines four forms of song-formats: Gita, Prabandha, Thaya and Aalapa (Gita-prabandha-sthaya-alapa-rupa-chatur –dandi) which seemed to have formed the pattern (or profile) for concert performances during 14-15th centuries. In that context, he makes frequent references to Gopala Nayaka (1205-1315) and to Tanappa-charya whom he calls Parama-guru ( Guru’s Guru) . Both of these were, perhaps, renowned performers of Charurdandi.

Along with the text, Venkatamakhin is said to have composed Lakshana-gitas on a large number of Ragas.

The text of the Chatur-dandi-prakashika was said to contain ten Chapters (Prakarana), each dealing with: Veena, Sruti, Svara, Mela, Raga, Alapa, Thaya, Gita, Prabandha and Taala. Among these, portions of Prabandha-prakarana and the entire Taala-prakarana are lost. But, interestingly, it is the Appendix (Anubandha) to the main text that brought focus on Venkatamakhin.

The Veena-prakarana generally follows the concepts and techniques described in Somanatha’s Raga-vibodha and Ramamatya’s Svara-mela-kalanidhi ; and, discusses about two kinds of fret-arrangements and tuning of the Veena-strings. Venkatamakhin mentions three types of Veena: Shuddha-mela-veena; Madhyama-mela-veena; and, Raghunathendra-mela-veena.

While describing the arrangement of the frets on each of the three types of Veena, Venkatamakhin follows the illustrations provided by Ahobala Pandita. According to that, arrangement of frets could be done in two ways: One with fixed frets on which all Ragas could be played (Sarva-raga-mela-veena); and the other with frets specially placed to suit playing of a particular Raga (Eka-raga-mela-veena) .

Venkatamakhin informs that during those days, besides the common Shuddha and Madhya-mela Veena described by Ramamatya, there was also a Veena with a higher tuning, i.e. in this tuning the first three strings are ignored and the fourth one tuned to Shadja has frets for three Sthanas. It was named by Govinda Dikshita as Raghunathendra-mela-veena, in honour of the King.

In the Second Chapter dealing with Srutis, Venkatamakhin ,in the traditional manner, talks about 22 Srutis and their distribution over Seven Svaras. He explains that the 22 Srutis are not placed at equal intervals, but are placed at specific intervals depending upon the Svara structure in the Raga. For instance, he says, the Shadja and Shuddha Rishabha on the Veena should be divided equally into three parts ; and two frets be introduced and thus three Srutis of `ri’ are seen (Sa – – ri).

The third Chapter on Svaras explains the nature of Shuddha and Vikrita Svaras. He explains the Shuddha Svaras with the illustration of Mukhari Raga having Sa, Ma and Pa having 4 Srutis; Ga and Ni having 2 Srutis; and, Ri and Dha having 3 Srutis.

As regards Vikrita Svaras, Venkatamakhin asserts that in practice there are only five in number and not 7 or 12 as mentioned in the texts of Ramamatya and Sarangadeva. The five Vikrita Svaras according to him are: Sadharana Gandhara; Antara Gandhara; Varali Madhyama; Kaishiki Nishadha; and, Kakili Nishadha.

Dr. N. Ramanathan explains: the one interesting feature of Venkatamakhin’s descriptions of Shuddha and Vikrita Svaras is that he considers the same Svara to be different if its interval from its previous Svara is altered.

Then, Venkatamakhin goes back to the ancient Gramas – Shadja, Madhyama and Gandhara; as also to the Murchana and the Tana. He also talks about Alamkara, Gamaka and Vadi-Samvadi Svaras. In all these, he refers to the descriptions as given in the older texts. As regards Vadi-Samvadi, he applies the ancient system to his contemporary practices and gives illustrations.

The Fourth Chapter is about his exposition of Mela scheme. He tried forming as many number of Melas as possible by permuting Shuddha and Vikrita Svaras. With this, he comes up with 72 Melas. Venkatamakhin asserts that his scheme of 72 Melas comprehends all the Melas that may have existed in the past and those that might be created in future. Out of the 72 Melas, Venkatamakhin was able to identify the Ragas of only 19 Melas. Therefore, he could name only 19 Melas; the rest were not assigned any names. These (53) he considered as theoretical possibilities, but (then, at that time) non-functional since no known Ragas could fit in to his scheme of these Melas.

[According to Emmie Te Nijenhuis: Venkatamakhin’s system of nineteen Melas closely resembles the Ramamatya’s Mela system: fifteen of Venkatamakhin’s Melas are almost identicle with Ramatya’s Melas. For instance; the Mela Bhairavi of Venkatamakhin corresponds to Hindola of Ramamatya. Similarly, Venkatamakhin’s Shankarabharanam corresponds to Ramatya’s Kedaragaula and Saranganata Melas. However, Venkatamakhin’s Bhupala, Pantuvarali, Simharava and Kalyani are not found in Ramamatya’s system.]

While describing the 19 Melas, he also gives the Svaras and the 22 Srutis in each case. And , while naming the 19 Melas he also indicates each one’s position (number) in his Grand scheme of 72 Melas.

-

- 1.He starts with Mukhari which is his first Mela and also the first among the 72;

- 2. Samavarali (3);

- 3.Bhupala (8);

- 4.Hejjuli (13);

- 5.Vasanthabhiravi (14);

- 6. Gaula (15);

- 7. Bhiravi Raga (20);

- 8.Ahiri (21);

- 9.Sri Raga (22);

- 10. Kambhoji (28);

- 11. Shankarabharanam (29);

- 12. Somantha (30);

- 13. Desaki (35);

- 14. Naata (36);

- 15. Shuddha Varali (39);

- 16. Pantuvarali (45);

- 17. Shuddha Ramakriya (51);

- 18. Simharava Raga (58) – an invention of Venkatamakhin; and,

- 19. Kalyani (65).

[The numbers mentioned in the brackets indicate the number assigned to the Mela in the overall scheme of 72 Melas.]

Venkatamakhin went by recognizing a Mela Raga if all the seven Svaras occurred in it, either in the Aroha or in the Avaroha. He did not insist that a Mela Raga should be a Sampurna Raga, with all the seven Svaras in both the Aroha and Avaroha. Further, during the time of Venkatamakhin the concept of Mela-karta had not yet evolved. All his discussions are in terms of the Melas.

While talking about his scheme of 72 Melas, Venkatamakhin makes very interesting remarks :

I have no doubt worked out the 72 Melas , but it might be said that this permutation is a waste , since, of these 72, only a few are known and found in practice; my reply is that I have devised a scheme which would comprehend all Ragas of all times and of all countries , Ragas now known and Ragas which might be created in future, Ragas which we do not know at all and Ragas which are only in text books , Ragas that are Desiya Ragas and the already generally accepted Melas of those Desi Ragas , such Ragas like Pantuvarali and Kalyani and their generally accepted Melas – it is to comprehended all these that I have devised this scheme of 72 Melas . Wherefore should one fear that it will be futile?

[Source: Collected writings on Indian Music .Vol 2 .p.264-5 by Dr. V. Raghavan]

Yes, indeed; it was not a futile exercise at all , but a path breaking pioneering work that led to improvements and refinements of the entire theory and scheme of the Melas and their derivatives.

[Venkatamakhin’s Mela scheme was thoroughly revised later. (We shall talk about these in a little while). The concept of Mela-karta (Janaka) from which other ragas may be derived and of Raganga Ragas also came about after Venkatamakhin’s time. Following that, the rest 53 Melas which Venkatamakhin could not name were duly recognized and assigned names. And, finally 72 Mela-karta Ragas were identified and named. Along with coining names, a system of hashing (Ka-ta-pa-yadi) for identifying the Raga-number with the aid of the first two syllables of its name was also introduced.]

In the Fifth Chapter – Raga prakarana – Venkatamakhin recalls the ancient system of identifying a Ragas with ten characteristics (Lakshanas) – Graha, Amsa, Tara, Mandra, Sadava, Audavita, Aplatva, Bahutva, Apa-Nyasa and Nyasa. He again talks of the earlier classification of Ragas as Grama raga, Bhasha Raga etc. He describes 55 Ragas picked on the basis Graha Svaras (the initial note – Adi-Svara). He starts with Ragas having Shadja as Graha Svara, then the Ragas with Rishabha as Graha Svara and so on. In case of each Raga, he mentions the Mela to which it belongs as also their Lakshana and Lakshya.

He gives a classified list (according to Graha, Nyasa etc) of 54 Ragas with their descriptions, their Svara structure and their Mela.

The Sixth Chapter, Alapa-prakarana talks of various stages in developing a Raga Aalapa.

The Seventh Chapter Thaya-prakarana is the briefest with only seven verses. Venkatamakhin describes Thaya (Sthaya) as a melodic phase with rich musical potential that forms the main ingredient in Raga elaboration. AS Dr. Ramanathan explains : In the Raga-alapana , Thaya is that in which a particular Svara is taken as the stationary point from which phrases are built up encompassing four Svaras in the ascending direction and later in the descending direction and finally conclude on mandra -sa.

The Eighth Chapter Gita-prakarana is about the Gita (the song); and also about the Shuddha Suda and Salaga Suda class of Prabandha. The latter, the Salaga Suda, in particular is treated a Gita. Venkatamakhin describes seven forms of Prabandhas under Salaga Suda: Dhruva, Mattha, Pratimattha, Nisharuka, Attatala, Rasa, and Ekatali

The Ninth Chapter Prabandha–prakarana is the extension of its previous Chapter; but , it is incomplete. Here, Venkatamakhin describes Prabandha in terms of Six Angas (limbs or elements): Svara, Birudu, Pada, Tena, Paata, and Taala; and Four Dhatus (sections in a song): Udgraha, Melapaka, Dhruva and Abogha. Then, he goes into to the classification of Prabandha depending upon the (a) number of Angas and (b) number Dhatus of which they are composed. He also provides number of illustrations.

The Tenth and the Last Chapter on Taala is lost.

When you look back you find that Chatur-dandi prakashika, basically, recalls the Music practise as they existed during 14th to 17th centuries. It throws light on the history of those times and clarifies some issues. But, by the time Venkatamakhin wrote this text, many of the subjects he discussed, particularly the Prabandha, were fading away giving place to newer forms of song-formats and improvised ways of rendering the Raga and the song.

Venkatamakhin was criticized for making uncalled for remarks such as: Ramamatya could not even understand what a Sheppard could easily understand; and, that not even Lord Shiva can improve upon his Mela scheme. (He, of course, was proved wrong as his Mela scheme was revised and improved upon). During the early 20th century controversies raged over the Melas of Venkatamakhin. Some critics argued that the Kanakambari -Phenadyuti nomenclatures – the Mela names – found in the Appendix to Chatur-dandi – prakashika though ascribed to Venkatamakhin are not actually his own** . It was also pointed out that Venkatamakhin’s Mela was already marked with Ka-ta-pa-yadi prefixes. And they said, it is not known who invented this ingenious system ; but, it could not be Venkatamakhin. Most of such controversies have now been put to rest.

[**Prof N Ramanathan in his article The Post-Sangitaratnakara Svara System (included under The Traditional Indian Theory and Practice of Music and Dance – Edited by Jonathan Katz) observes: It is unlikely that the Appendix was written by Venkatamakhin himself. One cannot sure that Venkatamakhin himself is the author of the names of the seventy-two Melas, Kanakambari, Phena- dyuti etc.,; their Janyas and their Lakshanas in Slokas.

In the Text proper, the Svaras of the Ragas Mukhari are mentioned as being all Shudddha; and, Mukhari is placed as the First Mela. However, in the Appendix, the names of the Melas are different; and, the First Mela, here, is Kanakambari. And, Mukhari Raga is listed under the Twentieth Mela. Further, under the First Mela, another different Raga (that is – Shuddha Mukhari) is given. This seems to suggest that Shuddha Mukhari comprises only the Shuddha Svaras.

The conclusion that follows is: that in the intervening period between the writing of the Text and the writing of the Appendix, certain changes had taken place in the Svara system. To illustrate: in the old system Ga was five Srutis away from Sa; and, in the new system, Ga was four Srutis away from Sa. Similarly, in the old system, Shuddha –rsabha was three Srutis, while in the new system it was two Srutis. Hence, the old scale of Shuddha Svaras was different from the new one. ]

Chatur-dandi-prakashika is known and recognized today mainly because of the 72 Mela Scheme that he introduced. And, this exercised great influence in reorganizing the Ragas and the Music structure in Karnataka Sangita. In that regard, Chatur-dandi-prakashika is a very important text.

Mela

Mela is a Kannada word that is still in use; and, it signifies ‘group’ or ‘gathering’. There have been many attempts, at various stages in the history of Karnataka Sangita, to organize the then known Ragas by groping them into categories. The earliest known such attempt was by the sage Sri Vidyaranya (1320-1380) who in his Sangita-sara grouped about 50 Ragas into 15 Melas.

Following Sri Vidyaranya, Ramamatya in the Fourth Chapter – Mela-Prakarana– of his Svara-mela-kalanidhi (1550 AD) introduced the theoretical framework for classifying then known Ragas into 20 Melas, the notes and names of which were taken from the prominent Ragas of that time. This was an improvement over the system initiated by Sri Vidyaranya.

Ramamatya lists 20 Melas: 1.Mukhari; 2.SriRaga; 3. Malavagaula; 4. Saranganata; 5. Hindola ; 6. Shuddha-ramakriya; 7. Desaki; 8.Kannadagaula; 9. Shuddanti; 10.Ahari; 11.Nada-ramakriya; 12.Shuddhavarjati; 13. Ritigaula; 14. Vasantha-bhairavi; 15.Kedaragaula; 16.Hejujji; 17.Samavarali; 18.Revagupti; 19. Samantha; and 20. Kambhoji.

Ramamatya gives details of Shuddha-Svaras and Vikŗta-Svara-s occurring in each of the Mela, a list of sixty-four Janya Raga-s classified under each Mela, and the Sruti positions of Svaras in the Melas. Mukhari is established as the Shuddha-Svara Saptaka in this treatise

Later scholars, that is after Ramamatya, started computing the maximum number of seven Svara combinations they could derive (melaprasthara) based on the number of Svara positions. Here, each author computed a different number of Melas based on the number of Svarasthanas he had theorised.

For example, during the second half of the 16th century Pundarika Vittala (in his Raga-manjari) introduced Ramamatya’s 19-Mela system in North India. But, he changed the names and scales of several Melas. He wrote two treatises. One was Sadraga Chandrodaya, and the other was Ragamanjari. In Sadraga Chandrodaya Pundarika Vittala gives 19 Melas with 66 janya ragas ; but, in Ragamanjari he gives 20 Melas and 66 janya ragas. (It is explained; in Ragamanjari Pundarika Vittala gives one extra Mela, because of the chatusruti Ri and kaisiki Ni combination). But, in his Sad-Raga-chandrodaya Pundarika Vittala mentions the possibility of 90 Melas.

Another South Indian musicologist who migrated to North was Srikantha who wrote his Rasa-kaumudi at about the same time. In classifying 37 important Ragas, he reduced Ramamatya’s 19 Melas to 11 or in fact to 10 as his scales of Malhara and Saranga were actually the same. His system resembled the contemporary Arabic system of 12 predominant modes (Maqam).

Then, following Ramamatya and Pundarika Vittala, Ahobala Pandita classified 122 Ragas under six Mela categories and three subdivisions:

Audava(pentatonic), Shadava(hexa-tonic) and Sampurna (hepta-tonic).

Hridayanarayana Deva who followed Ahobala Pandita, arrived at 12 Melas composed of two sets of six Melas depending on the number of Vikrita Svaras.

Lochana Kavi also came up with 12 Melas.

And, in Somantha’s Raga Vibhodha there are 960 possible Melas.

Even though they all came up with this computation they found that only a limited number of these were actually used in the form of a Raga. Therefore, Somanatha felt that 23 Melas would suffice to classify the 67 Ragas then in practice.

Thus, right from 14th century, Musician-scholars have been classifying and re-classifying Ragas into different sets of Melas, each according to his pet theory.

When you look back you will find that over a long period there had been a tendency to evolve as many numbers of Melas as possible.

The proliferation of Melas seemed to have come about because that instead of abstracting Melas from out of the Ragas in vogue, attempts were made to arrive at as many number of Svara-structures as possible out of the known Shuddha ( pure) and Vikrta ( modified) Svaras. This practice came to known as Mela –prastara (elaboration or spreading of the Melas). For instance; a Mela is basically a collection of seven Svaras. By permutation of these Svaras in varying ways one could arrive at a number of plausible Melas. Somanatha , as mentioned earlier, claimed that he could devise as many as 960 plausible Melas; but then , he found it reasonable to restrict the numbers to 23 abstracted from the then known Ragas.

This process of Mela-prastara went on till the number of Melas (or Mela-karta) settled down at 72.

[For a detailed and scholarly discussion on ‘The Mela Classification of Ragas ‘ with particular reference to Pundarika Vittala , please refer to Chapter 8 Mela system – of Dr.Padma Rajagopals’s thesis.]

*

One of the most important texts in that context was Chatur-dandi-prakashika of Venkatamakhin (1650), which brought the Mela system on a rational basis. It classified the Ragas according to the system of 72 basic scales (Mela). The basics of system still prevail, though with modifications.

In 1620, Venkatamakhin also corrected Ramamatya’s system by reducing it to 19 from the original 20 Melas, because he found that the notes of the two Melas were similar.

But, in the Appendix (Anubandha) to his Chatur-dandi-prakashika, Venkatamakhin mentions the possibility of classifying Ragas (Kanakangi to Rasikapriya) built on 12 Svara-Sthanas under a 72 Mela-scheme made into two groups of 36 each (Shuddha Madhyama and Prathi Madhyama). It was, at this time, only a theoretical possibility, since all those 72 Melas were yet unknown. Out of such 72 Melas, Venkatamakhin was able to identify the Ragas of only 19 Melas. The rest (53) he considered as mere theoretical possibilities; and, non-functional since no known Ragas could fit in to his scheme of these Melas. Therefore, he could name only 19 Melas; the rest (53) were not assigned any names.

[The scheme of 72 Melas devised by Venkatamakhin , during his time, was almost unknown outside the scholarly circles. Maharaja Tulaja of Tanjavur, in his work –Sangita saramritam (1735) – remarked that the Melas of Venkatamakhin had not attained publicity; and, for practical purposes, the Ragas covered under Twenty-one Melas would be sufficient.]

*

[There is some interesting discussion on Todi, presently, a prominent Raga in Karnataka Sangita. Venkatamakhin calls Todi an ‘outhara’ raga. He does not include Todi in the 19 Melas called as ‘praak-prasiddha melas. According to his scheme of Asampurna paddhati, Todi is the eighth raganga raga known was Janatodi.

Some scholars do not however agree with Venkatamakhin’s treatment of Todi. They point out that Todi is not a ‘northern’ Raga; and, its traces can be found in the Southern music – say in the Divya Prabandhams as Mudirnda Kurinji – though it was fully developed in the period of the Trinities.

Prof. Sambamurthy also did not agree that Todi was an outhara raga; and, he described Todi as a ‘naya ragam’- the one that offers ample scope for alapana, niraval and swaraprasthara. He said Todi was a sarvaswara gamaka varika rakti raga. Dr. S.A.K. Durga called Todi as one of the ragas having most samvaaditva (consonance) or arguably the most consonant raga.

Todi which is sung often with shadja varja and panchama varja, seems to have been among the favourites of Sri Dikshitar’s family. For instance; Ramaswamy Dikshitar composed a padam in Todi; Muthuswami Dikshitar’s dhyana kriti in his Navarana group is in Todi; Chinnaswamy Dikshitar’s popular pallavi ‘Gaanalola Karunaala vaala’ is in Todi; and, Baluswami Dikshitar’s chittaswarams for ‘Gajavadana,’ give the essence of Todi.

Todi – formally titled as Hanumatodi is the 2nd rāga in the 2nd chakra – Netra. It is the 8th Melakarta rāga (parent scale) in the 72 Melakarta rāga system – Sampurna paddhati.

Sri Tygaraja who followed Sampurna paddhati, has composed about 32 kritis in Todi, with each composition starting at every single note of the three octaves. It is a very popular raga, very often sung in the concerts. Yet; Todi is known to be a difficult raga, because of the complexity in its Prayoga (execution). That, perhaps, is the reason why beginners are not taught Todi and Saveri. ]

It is said that it was Venkatamakhin’s grandson Muddu Venkatamakhin, who gave the nomenclature for the Mela Ragas, (Kanakambari, and Phenadhyuti etc) in his Gitam called Raganga Raga Anukramanika Gitam (numbered as 15.14.1 in Sri Subbarama Dikshitar’s Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (1904). Please check page 250 /664 of the web-page / page 207 of the Book .

In Muddu Venkatamakhin’s Ragalakshana a drastic shift takes place in the Mela-concept. He synthetically creates Janya Ragas for the remaining 53 Melas that were earlier considered non-functional. Here for the first time the Raga-description is based purely on its Svara-sthanas. It is also at this stage that the Raga Grammar or its characteristic is described in terms of its Aroha and Avaroha Svaras.

(Please check here for Muddu Venkatamakhin’s Appendix (Anubandha) to Chaturdandi Prakashika )

Some say, it is likely that Muddu Venkatamakhin’s scheme grew in two stages. In the second stage the Katapayadi prefixes were added to suit the Raga-names; or the other way. The Gitas in the Raganga (Mela-kartha) Ragas bear the names with their Katapayadi prefixes.

Shri TM Krishna observes: ‘The Muddu Venkatamakhin tradition, which uses the terms Raganga Raga (equivalent term to Mela-kartha) and Janya Raga, adopts the opinion that the Raganga Raga needs to be Sampurna in either Aroha or Avaroha but non-linear (A-sampurna). It is believed that Muddu Venkatamakhin wrote Lakshanas for the Raganga (Mela) ragas and their Janyas.

Sri Muthusvami Dikshitar gave form to most of these Ragas through his compositions. As regards the A-sampura (not-sampurna) Ragas, Sri Muthusvami Dikshitar chose to change their structure in order to mitigate the ill-effects of direct Vivadi Svaras in their scale.

[Sri Subbarama Dikshitar while writing about the life of Sri Ramaswamy Dikshitar (father of Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar) says he learnt Mela system from Venkata Vaidyanatha Dikshitulu, who was the maternal-grandson of Venkatamakhin (Vaggeyakara Caritramu, pg.25, SSP English Translation Vol.1). This Venkata Vaidyanatha Dikshitulu is identified by some as Muddu Venkatamakhi.

However, Dr. R. Sathyanarayana differs. According to the dates given by Dr. Sathyanarayana (Rāgalakṣaṇam of Śrī Muddu Venkatamakhin; Introduction, pg.9) Muddu Venkatamakhin may have been born around 1650 A.D and Venkata Vaidyanatha was a younger contemporary who taught Ramaswamy Dīkṣhitar at around 1750 A.D.]

Again, during late 17th – early 18th century, a person called Govindacharya the author of Samgraha-chudamani changed the names of some Melas of Venkatamakhin.

[Sri T R Srinivasa Ayyangar , in his introduction to Sangraha Chudamani of Govinda , edited by Pandit Sri Subrahmanya Sastry (Published by The Adyar Library, 1938) writes : The author of this work Govinda , popularly known as Govindacharya, to distinguish him from his famous namesake , does not seem to have been known otherwise to fame. Neither his place of nativity , nor his antecedents , nor the time when he flourished can be traced with any accuracy.

Further , Sri Ayyangar mentions : a manuscript copy of Sangraha Chudamani was in possession of Manabuccavadi Venkata Subba Ayyar , an immediate disciple of Sri Thyagaraja; and, it had been copied by Maha vadidyanatha Sivan and Pattanam Subrahmanya Ayyar..

It is , therefore, very likely that Sri Thyagaraja was familiar with the text and its Mela classifications.]

Govindacharya expanded on Venkatamakhin’s Mela concept by introducing the Sampoorna Meladhikara (equivalent term to Melakarta) scheme which has a complete (sampoorna) Saptaka : both in the Arohana and the Avaroha structure; and importantly the Svaras are to be in linear order. In this scheme, the Mela-kartas arise out of systematic permutation of the seven Svaras into the twelve Svara-sthanas.

Govindacharya is also said to written lakshana-gitas and lakshana-slokas (numbering in all 366) covering 294 Janya Ragas. And, it is believed, he refined the Katyapadi prefixes by linking the Mela Ragas to their first two syllables of their names. This system of 72 Mela is the Karnataka Mela system of the present day.

Some say; while devising the system of 72 Meladhikara-s, based on 22 Srutis, Govindacharya adopted the nomenclatures and characteristics that were used by the musicologist Akalanka (later than Venkatamakhin?) in his Telugu work Sangita sara sangrahamu. Akalanka had developed his system on the basis of the Sruti positions in a Rudra-veena ; and, had employed the Katapayadi mode of computation. In the system devised by Akalanka, the Melakartas were complete both in the Aroha and the Avaroha. Sri Subrahmanya Sastry beleives that Sri Tyagaraja was the first Vakgeyakara to introduce Akalanka’s Melakartas ; and to compose Kritis , illustrative of their principles.

[Please refer to the Sangraha Chudamani of Govinda, edited by the renowned scholar, Pandit Sri S . Subrahmanya Sastry; and, published by Adyar Library, 1938. Please do read the highly educative introduction written by Sri T R Srinivasa Ayyangar.

But , there is a dispute about the very name Akalanka. Dr. V Raghavan, in the introduction to Sangita Sara Sangrahamu Tiruvenga Dakavi” edited by Dr. Narendra Sharma, remarks that the name Akalanka is ‘absolutely unreal’; and, Sri Srinivasa Ayyangar might have misunderstood the opening verse of the manuscript. He surmises that its author might have been one Tiruvenkata , who wrote it for a Lady named Kuntalamba (page ix).

Further , Dr. Raghavan states : there is hardly any ground for asserting that this Telugu text, in rather untidy Telugu, is the source for Govinda. ‘ – Page xi]

In any case :

Govindacharya’s insistence on a Sampurna Arohana–Avarohana profile lent the Mela-karta a sort of elegance. And, seen from another view, the Mela-karta scheme appears as a product of mathematical abstraction. And, naming of the Mela, the ragas, the Svaras (and introduction of Vivadi Svaras) seem rather incidental to its technical process.

Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar followed Venkatamahin’s scheme (Kanakambari-Phenadyuti); while, Sri Tyagaraja gave forms to most of the Ragas in the other scheme (Kanakangi-Rantnangi). The subtle but main difference between the two schemes appears to be the importance given to the linearity and non-linearity of the Svaras in Arohana and Avarohana.

*

Prof. Ramanathan explains : The difference between Mela-karta and Raganga-raga is that while the former (Mela-karta) had to have all the seven Svaras in both the Aroha (ascent) and in the Avaroha (descent); but, for the latter (Raganga-raga) it was sufficient if the seven Svaras were present either in Aroha or in Avaroha. Further , in Mela-karta , the Aroha and Avaroha the seven Svaras have to occur in their regular (krama) sequence ; while in the Raganga-raga , the sequence of Svaras in Aroha and Avaroha could be irregular (vakra) .

In other words; the Melakarta Ragas are all Sampurna Ragas, but the converse is not true, i.e., all Sampurna Ragas are not Melakarta Ragas

With these stipulations, the sequence of the Svaras in Aroha and Avaroha became the defining characteristic of a Raga. And , in about a century following the Chaturdandi-prakashika , the eminent composers , mainly the Trinity, composed Kritis in the Ragas classified under all the 72 Melas.

But , in the later period , the distinction between the Mela and the Raganga-Raga gradually faded away; and, the two concepts merged into one.

Thus, the formulation of the 72 Mela-prastara and the later auxiliaries greatly influenced the course of the South Indian classical music of the later period.

As per Shri TM Krishna: ‘Mela started out as a way to organize existing Ragas but moved to creating scales as Ragas using the Mela structure. Probably for the first time in musical history theory influenced practice. This is probably why many Ragas in performance even today are only Svara structures sans features that give a Raga an organic form’.

![]()

Raga Pravaham a monumental work and a reference source of immense value to learners, teachers, musician and musicologists alike, is an Index of about 5,000 Karnataka Ragas, compiled by Dr. Dhandapani and D. Pattammal. The list of Ragas is given both alphabetically and Mela karta wise. The different kramas for the same Ragas and same scales with different names are also listed.

Apart from indexing Mela-karta Ragas, Janya ragas, Vrja and Vakra Ragas and their derivatives; the Raga Pravaham lists about 140 Hindustani Ragas, which are allied or equivalent to Karnataka Ragas.

In his introduction to Raga Pravaham, the renowned musicologist and scholar Prof .Dr. S. Ramanathan (1917-1988)-(Wesleyan University, U.S.A), wrote :

The Raga system in Carnatic music has a long and interesting history from the time of Matanga’s Brihaddesi, where you come across the definition of Raga. The system has evolved through the centuries. Ragas like Gaula, Takka etc. are mentioned in the Brihaddesi.

By the 13th century, the Sangita Ratnakara of Sarangadeva lists as many as 264 Ragas. Here, you come across Ragas like Sankarabharana, Sri Raga, Todi, Malavagaula (which is referred to as Taurushka), and Kedaragaula etc.

In the 14th Century Vidyaranya, in his musical treatise Sangeetha Saram gives a list of fifteen Mela Ragas ; and , by the year 1550, Ramamatya in his Swara Mela kalanidhi speaks of 19 Melas and several derivatives from each of them.

In the beginning of 17th Century, Somanatha’s Raga Vibhoda; and Govinda Dikshitar’s Sangita Sudha are two important works which deal with Ragas current at that time.

In the latter half of 17th Century, Venkatamakhi, son of Govinda Dikshitar appeared on the scene; and, in his monumental work Chatur-Dandi-Prakasika expounded the 72 Mela-karta schemes, which brought the Mela Janya system on a rational basis.

In this work, he only showed the possibility of 72 Mela kartas. But, in his scheme, a Raga could be a Mela only in case it had all the seven Svaras either in the ascent (arohana) or In the descent (avarohana). Kedara-Gaula which is Audava Sampurna was a Mela in his scheme.

It is believed that it was Venkatamakhi’s grandson Muddu Venkatamakhi, who gave the nomenclature for the Mela Ragas, (Kanakambari and Phenadhyuti etc) in his Gitam called Raganga-Raga-Anukramanika-Gitam (found in Subbarama Dikshitar’s Sangitha Sampradaya Pradarsini, 1904).

Later, Govindacharya, the author of Sangraha Chudamani gave the nomenclature Kanakangi, Ratnangi etc. to the 72 Mela karta Ragas. These Melas had all the seven notes in the ascent (arohana) and in the descent (avarohana) as well. He has also given Lakshana-gitas and lakshana-slokas for many Janya Ragas.

Though the arohana and avarohana krama of a Raga does not tell us everything about the Raga, it provides the frame work on which it is built. Ragas like Sahana, Ahiri, Neelambari, Devagandhari and Yadhukula Kambhoji defy definition. But for the majority of the Ragas, the Krama helps.

![]()

When you look back the long and interesting history of Raga in Karnataka Sangita stretching from Matanga to the present-day, you find that the system has evolved through several stages. If Matanga defined the Raga and lent it a sense of identity, it was Ramamatya that activated the process of binding the Ragas into structured groups. This was improved upon by Venkatamahin; and later perfected by Muddu Venkatamahin and Govindacharya. These series of concepts and their refinements have provided Karnataka Sangita a unique and a thorough theoretical foundation.

*

The voluminous Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini by Sri Subbarama Dikshitar (1839-1906) , the grandson of Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar , running into about 1700 pages is a source-book on Music of India , tracing the history of Music from Sarangadeva to the 20th century through a series of biographies of noteworthy musicians and music-scholars . It also provides exhaustive details on 72 Melas as also tables of Ragas, Ragangas, Upanga-s, Bhashangas with their Murcchanas, Gamakas, in addition to details of the Taalas.

The Mela system also travelled North. Pandit Shri Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860-1936), a scholar and a musicologist, in his colossal work ‘Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati’ reorganized the Uttaradi or North Indian Music, mainly, by adopting the concept of Mela system as expanded by Venkatamakhin (1660) and others .

Bhatkhande also adopted the idea of Lakshana-geetas that Venkatamakhin and other scholars employed to describe the characteristics of a Raga. Bhatkhande arranged all the Ragas of the Uttaradi Sangita into ten basic groups called ‘Thaat’, based on their musical scales. The Thaat arrangement, which is an important contribution to Indian musical theory, broadly corresponds with the Mela-karta system of Karnataka Sangita.

- Bilawal – Dheerasankarabharanam

- Kafi – Kharaharapriya

- Bhairavi–Hanumatodi

- Kalyan–Kalyani

- Khamaj– Harikambhoji

- Asavari— Natabhairavi

- Bhairav –Mayamalavagowla

- Marva: –Gamanashrama

- Purvi: –Pantuvarali

- Todi: – Shubhapantuvarali

The ten basic Thaats (or musical scales or frameworks) according to the System evolved by Pandit VN Bhatkhande are (From Wikipedia):

[ It is said;Pundit Bhatkhande composed a Dhrupad (in Raga Purvi ; set to jhap tala) in praise of Venkatamakhin and his Chaturdandi Prakasika.

ab chatura dandi mata venkata sunave ||

dvadasa suran ke khata chakra banave || (ab chatura)

ra ga ra gi ra gu ri gi ri gu ru gu rachave ||

dha na dhi ni dha nu dhi ni dhi nu dhu nu manave || (ab chatura)

dva saptati mela prati madhyama so janita

raganga saba janaka ade kahave ||

aroha avaroha ke bheda ko sadha

bhashanga rupanga chatura upa jave || (ab chatura)

Pundit Bhatkhande states in this composition that Venkatamakhin authored the work Chaturdandi Prakasika; and, that he modelled 12 chakras with the 12 tonal scale. He then goes on to state that Venkatamakhin conceived of the different flavours of each of these positions (to constitute 16 swaras); he specifies three varieties of ‘ri’, ‘ga’, ‘dha’ and ‘ni’ and calls them out by name (ra, ri, ru, ga, gi, gu, dha, dhi, dhu, na, ni and nu). Bhatkhande then states that Venkatamakhin also explains the various combinatorial possibilities of ‘ra ga’, ‘ra gi’, ‘ra gu’, ‘ri gi’, ‘dha na’, ‘dha ni’, ‘dha nu’, ‘dhi ni’, ‘dhi nu’, ‘dhu nu’. In the sanchari, he states that Venkatamakhi conceived of the mathematical possibility of 72 families (melas) of ragangas (the janaka) raga-s taking into account the two madhyama possibilities (and the invariant Sa and Pa – not mentioned in the composition). Bhatkhande then states that Venkatamakhi spelled out (with authority and clarity) the murchanas (aroha-s and avaroha-s) of the various bhashanga-s and upanga-s that belonged to each family (raganga). The first and the last phrases of the composition contain the composer’s mudra (chapa) ‘chatura’. Bhatkhande adopted the pseudonym ‘Chatura pandit’ and all his compositions have the mudra ‘chatura’ built into them. This composition thus features two occurrences of the chapa. The dhatu and the matu of the composition blend extremely well and this dhrupad makes a powerful musical tribute to Venkatamakhin.

(Source acknowledged with thanks : http://srutimag.blogspot.in/2013/07/the-chaturdandi-prakasika-and-chatura.html)

[Please check here for a comparative study of Mela-kartas and Thaats -https://bioinfopublication.org/files/articles/2_1_7_IJNN.pdf ]

The 72 Mela-kartas

Emmie Te Nijenhuis in her Indian Music: History and Structure explains the 72 Mela-kartas.

The 72 Mela-kartas are arranged in 12 series (Chakras) each having 6 Ragas. All are having the same tonic (Shuddha Sa) and fifth (Shuddha Pa). All the Mela-kartas in the Chakras from 1 to 6 have a perfect fourth (Shuddha Madhyama; abbreviated as Ma). And, the Mela-kartas in the Chakras numbering 7 to 12 have augmented fourth (Prati Madhyama; abbreviated as Mi). With respect to the other notes in the scale Chakras 7 to 12 duplicate Chakras 1 to 6 respectively.

For a list of the seventy-two Melakarta Ragas , classified under two broad categories (Shudda Madhyama and Prati Madhyama Ragas) ; and, enumerated under twelve Chakras , from Indu (1) to Aditya (12) , please click here .

The name of each of the 12 chakra suggests its ordinal number as well.

:- Indu stands for the moon, of which we have only one – hence it is the first chakra.(Eka Indu)

:-Nētra means eyes, of which we have two – hence it is the second (Dve Neta)

:-Agni is the third chakra as it denotes the three divyagnis (fire, lightning and Sun).They could be the three Agnis viz. Aahavaneeyam, Anvwaaharyam & Gaarhapathyam. (Tri Agni)

:-Vēda denoting four Vedas is the name of the fourth chakra (Chatus Chakra)

:-Bāṇa comes fifth as it stands for the five bāṇaa of Manmatha (Pancha bana)

:-Rutu is the sixth chakra standing for the 6 seasons of Hindu calendar(Shad Riru)

:-Rishi, meaning sage, is the seventh chakra representing the seven sages (Sapta Rishi

:-Vasu stands for the eight vasus of Hinduism (Asta Vasu)

:-Brahma comes next of which there are 9 (Nava Brahma)

:-Dishi The 10 directions, including akasha (sky) and patala (nether region), are represented by the tenth chakra, Dishi. (Dasha Dishi)

:- Rudra Eleventh chakra is Rudra of which there are eleven (Ekadash Rudra)

:- Aditya Twelfth comes Aditya of which there are twelve (Dwadasha Aditya)

[Please do read Sri S Rajam’s most wonderful illustrations of the 12 Chakras and their 72 Melakarta-s.

http://www.carnaticindia.com/images/downloads/Rasi_Pocket_new.pdf]

Each Chakra is determined by the lowest, middle or highest variety of the second (abr, Ra, Ri Ru) and third note (abr. Ga, Gi, Gu).

The six Ragas of each series are individually determined according to the lowest , middle and the highest variety of the sixth (abr. Dha, Dhi, Dhu) and seventh note (abr. Na, Ni, Nu).

In order to make a clear diction between the three varieties of notes –Ga, Dha and Ni, the vowels of these tone syllables are changed, a- indicating the lowest; –i indicating the middle; and –u indicating the highest variety.

In short, the structure of the first (that is lower) tetrachord (purvanga) of a Raga is determined by its serial (chakra) number, while the structure of the second (the higher) tetrachord (uttaranga) is determined by the number of scale within the particular series (chakra) . Multiplying the serial (chakra) number (after having subtracted 1) by the number 6 and adding the number of the scale within the series, one arrives at the exact Mela (karta) number.

( Source : Raga Pravaham by Dr. Dhandapani and D. Pattammal)

**

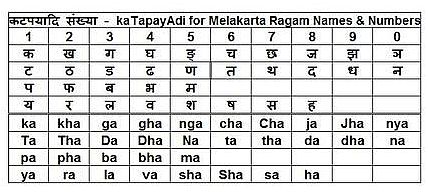

Katapayadi

The schemes of 72 Mela and Mela-karta employed a system of deriving the Mela-number by referring to the first two syllables of its name. This helped in easy tracking of a Mela from among the 72. The system of assigning a prefix number to each Mela was adopted from the ancient Katapayadi formula which classifies the letters of the Sanskrit alphabets in a specified manner.

Some scholars believe that the Great Grammarian Panini (5th century BCE) was the first to come up with the idea of using letters of the alphabet to represent numbers. And, that the Brahmi numerals were developed by using letters or syllables as numerals.

But, it is not clear who introduced the practice of numbering the Melas by means of the Katapayadi prefixes. In the earlier references to Mela system (either by Sri Vidyaranya or Ramamatya or Pundarika Vittala) the prefixes were not mentioned. But, in the Appendix (Anubandha) to the Chatur-dandi-prakashika the Melas were already marked by Katapayadi prefixes.

According to the scheme, the consonants have numerals assigned as per the above table. All stand-alone vowels like a (अ) and ṛ (ऋ) are assigned to zero. In case of a conjunct, consonants attached to a non-vowel will not be valueless. The only consonant standing with a vowel is ya (य). So the corresponding numeral for kya (क्या) will be 1. There is no way of representing Decimal separator in the system.

Under this naming scheme, the number of a Mela-karta (Janaka) Raga is obtained by decoding the first two letters using the Katapaya scheme; and reversing it. For instance; For Divyamani – Di=8; and Va=4, giving 84. And reversing that you get 48, which is its Mela number. Once you get the Mela number you get its notes too

[ For more on that please check : http://rksanka.tripod.com/music/katapaya.html]

Melakarta File by courtesy of Sri Basavarjtalwar at https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0e/Melakarta.katapayadi.sankhya.72.png ]

Please click on the figure for an enlarged view.

Please do read the scholarly work A Karnatik Music Primer by Dr. Parthasarathy Sriram at

http://www.ae.iitm.ac.in/~sriram/karpri.html

References and Sources:

I gratefully acknowledge

- Caturdandiprakasika of Venkatamakhi by Dr. N.Ramanathan

- The Anukramaṇikā Gīta in the SSP by Sumithra Vasudev http://musicacademymadras.in/webjournal/sumithra.pdf

- Indian Music: History and Structure by Emmie Te Nijenhuis

- The “ka-Ta-pa-ya” scheme http://rksanka.tripod.com/music/katapaya.html

- A Brief Overview of the Evolution of Indian Music

https://sites.google.com/site/chitrakoota/Home/carnatic-music

6. Collected writings on Indian Music .Vol 2 by Dr. V. Raghavan

ALL PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET

priyoshmontua

October 16, 2015 at 3:55 pm

Great resource — thanks for this synopsis!

sreenivasaraos

October 16, 2015 at 5:49 pm

Dear priyoshmontua , Thank you for the appreciation.

I am glad you found these useful.

Please do read the other articles as well.

Regards

Cris Forster

March 9, 2016 at 2:13 pm

Ramakrishna Sanka,

On your webpage:

http://rksanka.tripod.com/music/katapaya.html

all the numeric subscripts (R1=Db, R2=D, D3=D#), etc.,

which I invented to streamline the notation

Venkatamakhi’s 72 Melakartas, come directly from

my book: “Musical Mathematics,” published by

Chronicle Books, 2010, San Francisco, pp. 578-579.

******************************

1. shaDjamam S Doh C

2. Suddha rishabham R1 C# or Db

(read as C-sharp or D-flat)

3. chatuSruti rishabham R2

Suddha gAndhAram G1 Re D

4. shaTSruti rishabham R3

sAdhAraNa gAndhAram G2 D# or Eb

5. antara gAndhAram G3 Me E

6. Suddha madhyamam M1 Fa F

7. prati madhyamam M2 F# or Gb

8. pancamam P Sol G

9. Suddha dhaivatam D1 G# or Ab

10. chatuSruti dhaivatam D2

Suddha nishaadam N1 La A

11. shaTSruti dhaivatam D3

kaiSika nishaadam N2 A# or Bb

12. kAkali nishaadam N3 Ti B

******************************

These numeric subscripts also appear in the last

Graphic of Sreenivasarao’s blog “Part Nineteen”:

Please explain why you did not acknowledge

“Musical Mathematics” as your scholarly source.

Thank you.

Cris Forster, Music Director

The Chrysalis Foundation

http://www.chrysalis-foundation.org

sreenivasaraos

March 9, 2016 at 4:31 pm

Dear Shri Sanka

Thank you for the vist

Yes Sir, I do acknowledge your source ; and have done it too

I have given a reference to the web-page just below the figure

And, in the list of sources and References ( at Sl . no .4)

I have gratefully acknowledged your site

Kindly check again

Thank you

Regards

Cris Forster

March 14, 2016 at 8:25 pm

Dear Sreenivasaraos,

In response to my comment above, why did you

reply to Shri Sanka?

My name is Cris Forster, and I am the author of a

book entitled “Music Mathematics: On the Art and

Science of Acoustic Instruments,” published by

Chronicle Books, San Francisco, California, 2010.

I invented all the numeric subscripts in your

‘mandala’ graphic above to accurately simplify the

notation of Venkatamakhi’s 72 Melakartas. These

numeric subscripts were taken directly from

“Musical Mathematics,” pp. 578–579.

I tried to contact Shri Sanka, but was unable to do

so because his email address at the above-

mentioned link (at Sl, no. 4) does not work.

Cris Forster, Music Director

The Chrysalis Foundation

http://www.chrysalis-foundation.org

Cris Forster

March 14, 2016 at 9:25 pm

Dear Sreenivasaraos,

I stand corrected.

Regarding Venkatamakhi’s 72 Melakartas, I found

a system of numbers that is equivalent to my

numeric subscripts in the following text: “A

Confluence of Art and Music,” by Sangita Kala

Acarya S. Rajam & Kallidaikurici Veenai S.

Venkatesan.

Thank you for your patients.

Cris Forster, Music Director

The Chrysalis Foundation

http://www.chrysalis-foundation.org

sreenivasaraos

March 15, 2016 at 7:55 am

Dear Mr. Forester

You are welcome

Thank you very much for your very gracious reply

Regards

Cris Forster

March 15, 2016 at 1:12 pm

Dear Sreenivasaraos

Regarding the illustration above of Venkatamakhi’s

72 Melakartas, the following webpage

cites Basavarajtalwar as the author of this graphic (2009).

Sincerely,

Cris

sreenivasaraos

May 11, 2016 at 3:15 pm

Dear priyoshmontua

Thanks for the visit and the appreciation

Regards

sreenivasaraos

January 27, 2019 at 3:11 pm

From Sidhakam Bhattacharyya

January 27, 2019 at 2:56 pm

I am not a research scholar in music and I am simply a student who is learning Indian classical music of basic level. I am trying to find out the reason behind the selection of ten thaats by Pandit Bhatkhande out of thirty two number of available thaats. One of the probable reasons is that the thaats have been designed to match with the ragas collected by him, as such, it is alternatively known as “Dashamel Paddhati”. The synchronization of different ragas with the developed thaats is entirely based on his personal wisdom and, therefore, many of the researchers do not agree with him regarding his selection. There are numerous literature on thaats but I do not find any satisfactory answer. You are an author who has tremendous knowledgeable in the subject of music and I hope that you will be able to throw some light on this particular issue.

I convey my sincere regards to you.

sreenivasaraos

January 27, 2019 at 3:11 pm

Dear Shri Bhattacharya

Thank you for the visit and for the comment

It is generally beleived that Bhatkhande adopted the idea of Lakshana-geetas that Venkatamakhin and other scholars employed to describe the characteristics of a Raga. Bhatkhande arranged all the Ragas of the Uttaradi Sangita into ten basic groups called ‘Thaat’, based on their musical scales

For more on that kindly see Part Nineteen of the series at

Kindly keep in touch

Regards

sreenivasaraos

September 16, 2019 at 5:16 pm

Sandhya

September 9, 2019 at 4:48 am

Happy Day Sir,

I was going through the text Chaturdandi Prakashan.

Can you please let know where does this line appear in the text.

Gita-prabandha-sthaya-alapa-rupa-chatur –dandi

tried finding it.

not able to trace this line which mentions the core fundamental of the text.

if you could help me with the shloka number it will be really useful sir.

regards

Sandhya Sankar

sreenivasaraos

September 16, 2019 at 5:17 pm

Dear Sandhya

Pardon me for the delay in responding to your very interesting observation. I was not keeping well for some time.

*

The Chaturdandi-Prakashika of Venkatamakhin is essentially a compilation of the past theories (Lakshana) and practices (Lakshya); and, many of those were age-old. By the time of Venkatamakhin (perhaps around the year 1650), some of the musical formats (say, like, Prabandha) were almost fading away; and, were no longer in common use.

Though the Chaturdandi-Prakashika is not altogether an original composition, it serves a very useful purpose as a digest or a repository of the traditions and practices of the bygone era. But for this encyclopedic work, some of the significant developments that took place in the history of Karnataka Samgita might have been lost to us. The Chaturdandi-Prakashika thus forms a bridge between the ancient and what might perhaps be called as the modern periods.

And you , as a research scholar, know very well, the importance of the Chaturdandi-Prakashika in the present-day system of Indian music, is that it provides a basis for classifying the Ragas , arranged under the cluster of seventy-two primary Ragas (Mela) , with a large number of derivative (Janya) Ragas springing from each of such main (parent –Janaka) Ragas.

*

In his work, Venkatamakhin talks, in detail, about the melodic forms or musical formats that were prominent before his time. He fondly recalls and pays tributes to the Maestros of the earlier days like Gopala Nayaka (1205-1315) and Tanappa-charya whom he calls Parama-guru (Guru’s Guru), who , he says, were renowned exponents and performers of Charurdandi – four forms of song-formats comprising Gita, Prabandha, Thaya and Aalapa (Gita-Prabandha-Sthaya-Aalapa-rupa) – (Page 79 Prabandha Prakaranam ; Verses 4-6)

Gita-Prabandhyorevam Bhedo yadi Na kalpayate / Kutah siddhyo Chaturdandi krutho Gopala Nayakah // 5//

Pratyuktam tu Chaturdandi-tyato Gita Prabandhyoh / Bhedath pruth Prakaranam Prabandartha pravartate //6//

Here, just as the Gita and Prabandha are considered separate and distinct, the Aalapa and Thaya were also treated as distinct forms; though all the four, together, constituted the composite Chaturdandi .

Venkatamakhin, therefore, recognizes these four types of song-formats as “the illuminating four pillars”. It alludes to a system of four divisions of composition, namely Aalāpa (free flowing exposition of a Raga); Thāya (melodic inflection); Gīta (vocal composition set to a Raga); and, Prabandha (a structured composition). The Chaturdandi–Prakashika of Venkatamakhin is mainly a treatise on Music that illumines these four forms of song-formats. But, within a century all these forms were superseded; and, were replaced by the Kriti, the song format par excellence, which emerged as the dominant component of the concert repertoire.

*

The earliest mention of the four types of melodic forms (Gita-Prabandha-Sthaya-Aalapa), in a sequence, occurs in Svara-mela Kalanidhi of Ramamatya (1550 CE)

.

Gita-Prabandhaka-Alapa –Thaya yogya bhavanti hi Ity uttama ragah (Raga-prakaranam – sloka 5 on page 30)

While classifying the Desi Ragas of his time, Ramamatya considers about twenty Ragas which are not mixed with the shades of other Ragas (Asankirnatya), as the best among all the forms (Uttamottama) ; and, as most suitable for rendering the Gita, Prabandha, Aalapa and Thaya . He mentions that the other two class of Ragas – middling (Madhyamā) and inferior (Adhama) – are unfit for rendering all these four formats.

Following Ramamatya, Venkatamakhin also mentions that the Gita, Thaya and Prabandha of Tanappa and others are available for most of the Ragas. But some Desi Ragas like Kalyani and Pantuvarali are unfit for using the format of Chaturdandi (Raga-prakaranam – Slokas 107-108 page 65 )

Kalyani ragah sampurna Aarohe Mani varjitah / Gita Prabandha yogyo api turuskaranamati priyah // 107//

Ragah Pantuvaralyakhya sampurna pamara priyah / Gita Thaya Prabandhanam duraad duratarah smruthah // 108//

Another text of the Vijayanagara period (Ca.1525) Sangita-sµryodaya, names: Sthayi, Arohi, Avarohi, and Sanchari varnas, as the components of the Chaturdandi (III. Svarådhyåya)

Further, Tulaja Maharaja I (who ruled Thanjavur from 1729-35 CE) in his Sangita-Saramruta explains the term Chaturdandi and its concept by illustrating through application (prayoga) of various musical formats, such as: Gita, Aalapa, Thaya, Prabandha, Suladi, Sloka, Varna, Daru, and Pada. He tries to illustrate the Rupa (form) that a Raga takes in each of those song-formats, revealing its varied aspects in each type of composition. He explains; of all those formats only the four – Gita, Thaya, Aalapa and Prabandha – which are well grounded in tradition, together appear to be the classical modes of Raga presentation. In other words; considering the importance assigned to these four types of musical forms, it could be said that they formed the regular and principal materials for the music performances of those times.

It is said; the structure of a Raga, its melodic content is interrelated and complicated. And, one has also to take into consideration the aesthetic factors for creating a musical flavor (Rasa) and significance that is unique to each Raga.

*

Thus, the concept of Chaturdandi had been running through all along, as four channels, for illustrating and giving expression to classical (Uttama) Raga forms. And, this mode of presentation appears to have been the mainstay of the performances of instrumental and vocal music during the times prior to that of Venkatamakhin.

Just as Raja Tulaja did, Venkatamakhin also regarded that only the four – Gita, Thaya, Aalapa and Prabandha – which are well grounded in tradition, together are capable of classical (Uttamottama) Raga presentation. He was, of course, influenced by the rich musical tradition of the past, largely shaped by these four forms of presentation. The title assigned by Venkatamakhin to his work, namely Chaturdandi Prakashika, therefore, seems to have come about as a consequence of those influences. Venkatamakhin in his work dealt with each of these four channels of Raga expressions, exclusively, in each chapter, which form the core content of his treatise, consisting a total of ten chapters.

*

Yes Maa, as you rightly observed, the line Gita-prabandha-sthaya-alapa-rupa-chatur –dandi, in sequence, per se, does not seem to specifically appear in the text of the Chaturdandi Prakashika. Yet; the concept of Chaturdandi had been consistently appearing, like a phrase that repeats at the end of a verse of song or like a thread that runs through all along, in the texts of the Karnataka Samgita tradition, since the time of Ramamatya.

Venkatamakhin, perhaps, considered Chaturdandi, the standard types of melodic forms, as a very significant phase in the unfolding of the Music tradition of India. Hence, he accorded greater importance to the system of four divisions of composition; and, named his text as Chaturdandi-Prakashika, the four illuminating pillars of Music.

*

I am not sure if I have been any help to you at all. But, I hope this spurs you along your research project with Godspeed.

Please keep in touch; and, let me know how well you are progressing

Cheers and regards

Rsr Swamy

October 3, 2019 at 10:42 am

Very nice post, Sir. Thank you.

Venkatamakin was the grandfather , Govindacharya the son and muthu-venkatamakin the grandson. The Thyagaraja school follows Govindacharya nomencvlature and Dikshithat school follows Muthu Venkatamakin school, though both have 72 parent scales.

I know the parent ragam scales for the Thyagaraja/ShyamaSastry schools.

https://sites.google.com/site/cmhm4me/home/melakartha-keyboard

But what are the names of the same 72 meLakartha ragams in Dikshitar school? Where can I find that information?

sreenivasaraos

October 4, 2019 at 3:12 am

Dear Shri Swami

As mentioned earlier, Sri Tyagaraja gave form to most of the Ragas in the Sampūrṇa-Raga-paddhati system, where each Mela-karta has all the seven Svaras in their Aroha (ascending) and Avaroha (descending) scales. Here, the 72 Melakarta Ragas (from Kanakangi to Rasikapriya) are grouped under Twelve Chakras.

Sri Mutthusvami Dikshitar followed the other system – Venkatamakhin’s classification of Melas – termed as Raganga Raga (equivalent term to Mela-kartha) ,which adopts the principle that the Raganga Raga needs to be Sampurna in either Aroha or Avaroha but non-linear (A-sampurna , not-sampurna). Here, under Venkatamahin’s scheme (Kanakambari to Rasamanjari) , Sri Mutthusvami Dikshitar gave form to most of those Ragas through his compositions. (But, at the same time, he was quite aware of the classifications under the other system as well).

Prof. Ramanathan explains: The difference between Mela-karta and Raganga-raga is that while the former (Mela-karta) had to have all the seven Svaras in both the Aroha (ascent) and in the Avaroha (descent); but, for the latter (Raganga-raga) it was sufficient if the seven Svaras were present either in Aroha or in Avaroha.

Further , in Mela-karta , the Aroha and Avaroha the seven Svaras have to occur in their regular (krama) sequence ; while in the Raganga –raga , the sequence of Svaras in Aroha aand Avaroha could be irregular (vakra) .

In other words; the Melakarta Ragas are all Sampurna Ragas, but the converse is not true, i.e., all Sampurna Ragas are not Melakarta Ragas.

Sri Subbarama Dikshitar in his Sangita –Sampradaya-Pradarshini, explains, describes and illustrates in great detail the 72 Raganga Ragas spread over three volumes: Volume I (1-24); Volume II(25-36); and Volume III(37-72).

in Volume One , pages xix to xxv , Sri Subbarama Dikshitar provides the names and other details of the 72 Raganga and Janya Ragas , in a tabular from under the title “ Ragangopanga Bhashanga –Raga Murchana Table’.

Please check http://www.ibiblio.org/guruguha/ssp_cakram1-4.pdf ; and go to page xix

Kindly refer to my article on Sri Subbarama Dikshitar at

I trust this helps

Regards

Rsr Swamy

October 23, 2019 at 9:11 am

Thank you Sir.

I think I made a blunder. Govindacharya , who wrote sangraha chudamani was not the father of muddu Venkatamahin, grandson of Venkatamahin.

The present MK system ( folowed by Thyagaraja ) is the creation of a later Govindacharya.

Kindly enlighten me.

I am mostly following your blog posts in my new attempt to give a gist of CM composers, in historical perspective.

https://sites.google.com/site/4carnaticmusic/composers-quick-reference

Best Regards.

RSR

sreenivasaraos

October 24, 2019 at 12:59 pm

Dear Shri Swamy’

It is OK. It is understandable. Not much is known about Govindacharya, the author of Sangraha Chudamani. Because of that, he was often mistaken for the more famous Govinda Dikshita of the Tanjavur Court. It is said; the Lakshna Gitas of Govindacharya were, initially, published as being the works of Govinda Dikshita.

For more about Govindacharya , please check my blog (Part Nineteen)

*

So far as I understand …

In the latter half of 17th Century, Venkatamakhin, son of Govinda Dikshitar , in the Appendix to his work Chatur Dandi Prakasika expounded the 72 Mela-karta scheme, which brought the Mela-Janya-system on a rational basis. But, in this scheme, he only pointed out the possibility of 72 Mela-kartas. According to Venkatamakhin’s scheme, a Raga could be a Mela if it had all the seven Svaras – either in the ascent (Aroha) or in the descent (Avaroha).

It is believed that it was Venkatamakhin’s grandson Muddu Venkatamakhi, who gave the nomenclature for the Mela- ragas, (Kanakambari , Phenadhyuti etc.,) in his Gitam called ‘Raganga Raga Anukramanika Gitam’ (found in Sri Subbarama Dikshitar’s ‘Sangitha Sampradaya Pradarsini’, 1904.

Please check here page 250 /664 web-page (which is the page 207 of the book) at

http://www.ibiblio.org/guruguha/ssp_cakram1-4.pdf

*

Later , during late 17th – early 18th century , a person named Govindacharya, the author of Sangraha Chudamani changed the names of some Melas as in the original scheme of Venkatamakhin; and, assigned them new nomenclatures , such as ‘Kanakangi’, ‘Ratnangi’ etc. to the 72 Mela-karta-ragas. A very noticeable feature of all these Melas was that they had all the seven notes (Svaras) in both the ascent (Aroha) as also in the descent (Avaroha). He also composed Lakshana-gitas and Lakshana- slokas for many Janya (derived) ragas.

As is well known, Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar followed Venkatamahin’s scheme (Kanakambari-Phenadyuti); while, Sri Thyagaraja gave forms to most of the Ragas in the other scheme (Kanakangi-Rantnangi).

Please check my post (Part Nineteen); and also read the very well written Introduction by Sri T R Srinivasa Ayyangar to Sangraha Chudamani of Govinda<a href=“https://archive.org/details/SangrahaChudamaniOfGovinda” rel=”nofollow”>, edited by the renowned scholar, Pandit Sri S . Subrahmanya Sastry; and, published by Adyar Library, 1938.

*

As regards your commendable effort in constructing an easy-to-refer Directory of the Carnatik Music Composers, may I suggest that you may treat the Vaggeyakara Caritam , a segment of the Sangita sampradaya Pradarshini of Sri Subbarama Dikshitar , as the primary source.

May the Great Mother Bless you with success and all the good things in life.

Regards

Rsr Swamy

October 28, 2019 at 6:48 am

Respected Sir,

Thank you for your guidance. I think, the following summary is useful to beginners.

asampoorNa tradition

===================

1) Govindha Dheekshithar ( propounds the MeLa system)

2) Venkatamakhin ( son of Govinda ) ( arrives at 72 parent scales as a possibility)

3) Muddu Venkatamakhin -grandson of Govinda)

( Final form of 72 parent scales of AsampoorNa tradition)

( followed by Muthuswami Dikshitar)

=====================================

SampoorNa meLa tradition ( followed by Thyagaraja )

———————————–

4) Govindacharya ( not much is known about him!)

The final form which has come to stay for the last 200 years.

====================================

It is a bit ironic that the standardizer of the MeLakartha scheme is so little appreciated!

—————–

Modern students understand even MD ragas only when stated with near equivalent in the sampoorNa paddhathi!

————————————————————————-

https://sites.google.com/site/4carnaticmusic/home/13-muthuswami-dikshithar/dikshita-kritis-list

Thank you Sir.

I am preparing a list of links to your invaluable blog posts on music system

—————-

Pardon my impudence, but , may I suggest that , in each of your blog posts, it will be better to give a link to an index page, so that the readers will have a quick guidance, .

I am trying that method for my trivial posts.

Rsr Swamy

October 28, 2019 at 2:37 pm

muddu venkatamakhin was grandson of Venkatamakhin ( not of Govind Dikshitar). A slip. Regretted.