Continued from Part Twenty one – Dhrupad Part One

Part Twenty two (of 22) – Dhrupad – Part Two

Bani

Dhrupad flourished as the principal music format during the 16th century in the Mughal Courts. During its affluent times, Dhrupad developed into four distinct melodic forms known as Vani or Bani. It might be rather incorrect to label or call them as ‘styles’.

Because, apart from the ways of rendering the songs many other complex elements were associated with each Bani, such as : the ideology (spiritual or otherwise) , the intent, devotion, melodic types, nature of compositions, repertory , ways of transmitting orally from generation to generation, how they viewed their own Music and how they liked the world to view their Music and so on

And, above all there was the question of tradition; because, for a Dhrupad performer Tradition is of prime importance. According to their traditions, Dhrupad is a body of spiritual and mystical knowledge to be practiced with devotion (Bhakthi) and dedication (Shraddha). It is primarily an act of submission to ones indweller; not a tool for entertainment.

During the time of Akbar, four classes of Bani-s seem to have gained prominence. Though they might have been distinct in their initial stages, later each assimilated some aspects of the other Bani-s. Therefore, by about the 17-18th century , they almost had merged into one ancient tradition.

A Dhrupad singer of Akbar’s time was addressed as Kalawant. The Kalawants identified themselves with a Bani, which they came to regard as their tradition.

The four Bani-s of Akbar’s time were: Govarhar, Khandahar, Nauhar and Daguar; and, each was named after the place of its origin or its originator.

[ Giti-Bani

Before going further, lets talk a bit about Gitis.

Giti is a familiar concept in the ancient Indian music; and, is associated with Alamkara and Gamaka. The very ancient scholars such as Kashyapa, Yastika, Shardula, Durga Shakthi, Bharata and Matanga; and, later Sarangadeva, all have discussed about Gitis.

These Gitis were not Ragas or similar forms. Here, in these texts, Giti was understood as the methods or styles of producing a song; as various modes of rendering Grama Ragas and regional tunes ; singing the songs composed in deśa-bhāṣā; also rendering the songs coming from various regions and people.

In general, Giti could be taken to have meant charming song-forms; or as modes of singing a piece of music combining poetry, melody and rhythm.

:- Kashyapa mentions two Gitis – (Bhasha and Vibhasha);

:- according to Bharata , Yashtika spoke of three Gitis – (bhasha, vibhasha, and, antar bhasha);

:- but, Matanga says that Yashika mentioed five Gitis – (Shuddham, Bhinna, Vesara, Gaudi and Sadharita) ;

:- Shardula recognized only one Giti (bhasha);

:- Durgashakti accepted five Gitis – (shuddha, bhinna, gaudi, raga (vesara/ vegasvara), sadharana);

:- and, Bharata talked of four (pada) Gitis – (magadhi, ardha magadhi, sambhavita, prithula).

Matanga, in his Brihaddeshi (302-308), discusses, in fair detail, the seven kinds of Gitis: (1) Shuddha; (2) Bhinnaka; (3) Gaudika; (4) Raga-giti; (5) Sadharani; (6) Bhasha-giti; and, (7) Vibhasha—gitis.

Of the seven classes of Gitis, it is said; the Shuddha and the Bhinnaka have each five varieties; Gauda has three varieties; Ragas are of eight varieties; Sadharani is of seven varieties; Bhasha is of sixteen kinds; and, Vibhasha as of twelve kinds.

He also relates the various Gitis to the Shadja grama and Madhyama grama Ragas,current in his time; and, explains the Ragas with reference to these seven classes of Gitis.

Matanga talks about the Gitis in association with Alamkaras and Gamakas. For in instance; while discussing about Raga-giti, one of the seven charming Gitis; the fourth in his enumeration (Raga-gitis-caturthika); and, with attractive ” svara compositions, with beautiful and illuminating graces”, he mentions:

:- Raga-giti , adorned with (shobhane bhavath) delightful Svara articulations of lucid, powerful (raurasau), of even quality (sama), should be rendered with varied delicate Gamakas (lalithau–Gamakau-vichitrau); and, should be ornamented with delightful Svara articulations in all the four melodic movements (chaturnamapi varnanam ) that are lucid (prasanna) , powerful (raura) and even (sama) (300-301);

:- Shuddha Giti is that which is full of Svaras and Srutis that are straight (samaihi) , delicate (lalita) and steady (ruju) in the mandra, madhya (lit. not mandra) and Tara ranges (shruthibhi purna), (291-2)

:- Bhinna Giti is that which consists subtle, quick moving, turning, swinging, scattered, (sukshmashca prachalai vakra sullasita prasaritau ) delicate (lalitha) Svaras, high (Tara) and low (Mandra)- ( 292-293)

:- The three Gauda (melodies) are beautiful (shobhanah) with Svaras rendered with delicate Ohala (a type of shakes) , made up of sounds like ‘haa-s’ (ha-kara) and ‘ooh-s’ (U-kara). The Õhali gives expression to mandra tones, with the chin resting on the chest (chibukam hrudaye –nyasya).

The delicate Ohali should be rendered by expert singers (geyo-vidhuhu) in quicker and quicker tempo ( druta-drta-taro), full of shake (saha kampane pidita), rendered both by distinct and barely visible hand movements ( drusta-drustena panina) (on the Veena?) with karanas over the three octaves (tristhana) and full of movement over the entire octave range (svara-sthana-chalanakula). (293-299)

:- Sadharana Giti, according to experts on Giti (Gitignau) , should be made up of a judicious combination (su–yogitau) of straight and delicate, a little subtle (sukshma-sukshmaischa), a little plain, pleasant (su-shravya), slightly quick paced (irsha-druta), soft (mrudu) and gentle (lalita) , movements and Svaras, that are smooth, with subtle variations in tone (kaku misrau) . Thus, Sadharana Giti is understood (jneyo) as resting on all the Gitis (sarva-giti-samashrayah). (302-303)

:- Bhasha Giti is defined by the experts on the Giti ( Giti-vichakshnau) , as being characterized by movements that spring from the throat (gatrajau), smoothly (lakshanau), drenched with expression (kakurakthau), well-structured (suyogitau), shaken delicately ( kampitai) and powerfully, imbued with Prakrit intonations coming from Malva region (Malavi ) (Malavi kaku nanchitau), and expressed in gentle, soft ovements (lalitha sukumarascha) in a controlled manner (samyate)-( 304-306).

:- Vibasha Giti should be rendered blending in the Gamakas that are pleasant on the ears (Gamakau–srotra-sukhadai-lalithairasthu), following public taste (rajyate lokah) , with delicate as well as bright (lalitau bhrahubhi diptau), strong shakes (kampitai) and plain (samaihi) movements , shooting up to the Tara and Atitara ranges, and softened as well as flaming ones in the middle range (madhyama diptau) , incorporating gamakas that are pleasant to the ear and delicate (srotra–sukhadai lalitai astu), according to the singer’s will (yadrucchaya samyojya) , and to the delight of the people (lokan ranjate) – (306-308).

But , Sarngadeva accepted just five out of the seven Gitis: shuddha, bhinna, gaudi, rag (vesara/ vegasvara), and sadharani. His time was just before the period that came under Persian influence.

Perhaps , because of that reason, during the early Mughal times too, these five types of Gitis continued to be recognized; and, each type of Giti was associated with a group of Ragas.

*

Now, Giti meant the way of singing (Gita); thus , giving a form to the Ragas.

During the Mughal times, it is said,

:- Shuddha Giti (the pure) used straight and soft notes;

:- Giti (innovative) with articulated, fast and charming Gamaka phrases (Alamkara);

:- Giti (Eastern) sonorous with soft , unbroken mellow stream of singing in all the three tempos (Kaala) Mandara (slow), Madhya (middle) and Tara (upper) with appropriate Gamaka Alamkaras;

:- or Vegasvara Giti (fast notes) suited for speed or fastness in rendering the notes (Svaras) ; and,

:- the Sadharani or Sadharan Giti (General) combined in itself the virtues and merits of the other four Gitis.

[Matanga also describes Sadharana Giti (302-303) as the universal form of Giti ; combining in itself the merits the other four other Gitis. He described Sadharana Giti as that which is sung with svaras that are smooth and fine (Lalita); is gentle, pleasant to the ear, slightly quick, and soft. And, when rightly produced, it is related with all types of Gitis. It is therefore universal or Sadharana. And, in this way, it is considered to be connected to all the Gitis.

Rujubhir lalitah kinchit suksmasuksmais cha susravaih / isaddrutais cha kartavya mrdubhir lalitais tatha / / prayogair masrnaih suksmaih kaku misraih suyojitaih / svaraih sadharana Gitir gitijanaih samudahrta / evem sadharana jneya sarva giti samasraya // 302-303// ]

[ King Nanyabhupala (who reigned in Mithila between 1097 and 1133 A.D) in his Bharatabhashya, connects each type of Giti to specific hours (yamas) of the day. For instance; the two Gitis, shuddha and bhinna, are assigned to the first yama or prahara (a three-hour period) of the day. The Giti, gaudi, is placed at mid-day; vesara is in the first part of the day; and sadharana is said to be common to all hours of the day.

Nanyadeva was referring to Gitis in association with the Ragas with the time of singing. He extended the concept to the relations between the seasons and the Ragas. For instance, Nanyadeva , in his Sarasvati-hrdaya-alamkara hara, while discussing seasonal Grama ragas, quotes Matanga thus – yadah matanga –

sarve raga mahadeve samyak santoshkarakaha |hemant-greeshma-varshasu kaleshu gan-shasimiha | shadja-madhyam-gandhargrama geya yathakramam ||3

All Ragas are dear to Lord Mahadeva. Yet; it would be proper to sing the songs of shadja; madhyama; and, gandhara gramas during winter, summer and rainy seasons.

At another place ,Narada, in the third khanda of the chapter Sangeetadhyaya of his Sangeet Makranda, had categorized ragas according to the suryansh (solar) and chandransh (lunar) groups, i.e. sun- and moon-based ragas. He further said–

evam kalavidhin gyatva gayedhyaha sa sukhi bhavet || ragavelapraganen raganan hinsako bhavet | yaha shrinoti sa daridri ayurnashyati sarvada

One who sings the raga-s according to their designated times, attains peace and prosperity. The raga-s themselves shall become violent and lose their attraction if sung off their times. Such (singers) become poor and live a short life

Nanyadeva recommends : Hindola raga is best in spring; Pancama in summer; Sadjagrama and Takka during the monsoons; Bhinnasadja (Bhairava) is best in early winter; and, Kaisika in late winter

Somesvara (Manasollasa 1131 CE) is said to be the earliest to codify the tradition of allocating the six Ragas to the six seasons:

(1) Sri-raga is the melody of the Winter (2) Vasanta of the Spring season (3) Bhairava of the Summer season (4) Pancama of the Autumn (5) Megha of the Rainy season and (6) Nata-narayana of the early Winter.

Following that tradition, Sarangdeva (12th century) in his Sangeet Ratnakara, emphasized the importance of the performance of the ragas in their proper season and time.

In the chapter Raga-viveka-adhyaya, Sarangdeva laid special emphasis on the specific times and seasons for the performance of ragas. He also makes mention of the allotted times and seasons for the rendition of the ancient Gram-ragas. For e.g. he says

Shadjagrama raga is to be performed in Varsha ritu; Bhinna Kaishik in Shishira ritu; Gaud Pancham in Grishma ritu; Bhinna Shadja in Hemanta ritu, Hindol in Vasanta ritu,;and , Raganti in Sharad ritu

Sarngadeva also mentions the hour of the day against every Raga that he describes, using phrases like geyo’hnah prathame-yame (to be sung during the first yama or prahara of the day); and, madhyama’hnogeyo (to be sung during mid-day).

He associated pure and simple ragas to early morning; mixed and more complex ragas to late morning; skillful ragas to noon; love-themed and passionate ragas to evening; and , common (sadharani) ragas to night. Sarngadeva also connects the Ragas to seasons.

In the later times, the idea of linking the ethos or character of a Raga with the hour of the day was carried on by many writers.

This concept was explained and systematized by Pandit VN Bathkhande by establishing the relation between the pattern of Svaras and hour of the day/night; and, its impact on the singer and the listener. He also put forth a system of forging a relation between Vadi Svaras, Tivra Madhyama and Purvanga–Uttaranga Ragas with the time of the day/night. For more please click here ]

Source :The Dictionary of Hindustani Classical Music by Bimalakanta Roychaudhuri ]

During the Mughal period, each type of Giti came to be associated with a particular Dhrupad Bani (akin to the different gayakis of present-day), in its rendering of Alaap. In that process, Shuddha Giti corresponded with Daagar Bani; Binna Giti with Khandar Bani; Gaudi Giti with Gaudhara or Gobarahara Bani; and Sadharani Giti with Nauhar Bani. As regards the Vesara Giti, it corresponded with songs of any type of Bani that need to be rendered with speed. ]

*

Govarhar or Shuddha Bani:

Tansen is said to be the originator of this Bani. It is said; he was originally a Gauda Brahmin (Ramtanu Pandey). And therefore, his style came to be known as Gaudiya or Govarhari Bani. This Bani was characterized by its smooth glides, almost linier in character. Its gait was slow and contemplative; spreading a feeling of repose and peace.

Gauhar Bani was described as Shuddha Bani that is chaste and pure. Its rendering was straight and simple with the gaps between the words and between the stanzas , bridged by aans or meands. It was ideally suited for compositions in slow tempo (Vilamba kala) portraying Shantha, Gambhira and Bhakthi Rasas.

Khandahar Bani:

Raja Samokhan Singh was a famous Beenkar. He , perhaps , belonged to Kandahar region (?). Thus, his style of singing came to be known as Kandahar Bani.

[It is said; the traditional weapon of Samokhan Singh‘s family was Khanda, after which the Bani of Dhrupad is named i.e., Khandar Bani. This family was also called as Khandara Beenkar, after their family weapon Khanda , a double-edge straight sword (Sanskrit khaḍga).

There is an alternate explanation; according to which , Maharaja Samokhan Singh, the famous Beenkar, belonged to the region of Khandar. Its dialect was Kandari. Now; Kandar is a Village in Jalore Tehsil of Jalore District, Jodhpur Division of the Rajasthan State. It is located 34 KM towards South from District headquarters Jalore. ]

The Khandar Bani was rich in its variety. Its gait was majestic and robust, using heavy and vigorous Gamakas, expressive of valor. In contrast to Gaudiya or Govarhari Bani , it usually was not sung in slow tempo.

Khandar Bani was prominent in Jor, Alaap of the Rudra Bina. Along with bewildering pattern of vigorous Gamakas, it could also bring out soft and delicate notes. The Dhrupad compositions of this Bani were set mostly in Madhya and Dhrut laya, with the singer innovating series of Bol-tans in rhythmic patterns along with the Pakhawaj. The Bani was best suited for expressing the fast and furious Vira Rasa.

Nauhar Bani:

Its founder was Rajput Shri Chand who belonged to Nauhar. It style was characterized by quick, jerky passages employing a variety of Gamakas. It usually moved in quick successions, moving as it were in slow deliberate curves from the first to its third or fourth note, and then changing course . Thus, the Nauhar Bani with its jumpy chhoots (short, quick musical run) surprised the listeners at each of its movements.

Nauhar Bani was technically called Chhoot style with predominance of Madhya laya , spacious Dhrupad compositions .It was ideally suited for depicting the joy and wonder of Adbhuta Rasa of songs set to smaller beats. This style of rendering is very popular with wandering minstrels singing songs of love and war.

Daguar Bani:

It said to have been founded by Braj Chand who belonged to a place called Daguar. Hence his style came to be known as Daguar Bani. It was characterized by its delicately executed meends (glides) with sliding Gamakas. It was marked by correct intonation, purity of design, simplicity of execution and a massive structure. It adopted the contemplative elaboration of Govarhar.

The rendering of the songs and Dhrupad in Daagar Bani was mostly in Vilambit and Madhya laya, providing greater scope for portraying various Rasas in different Taalas .It was well suited for Dhamar songs. And, in its medium tempo it judiciously blended in the Kandahar Bani to add color to its performance.

(Source : Bimal Mukherjee in his Indian Classical Music – Changing Profiles outlining the characteristics of the Banis )

The following stanza pithily captures the salient features of each of the four Bani-s.

Jor Jor se Kandhar gave; Madhu bole se Nauhar leve; Saans badi hai gauhar ki; Alaapchari hai Dagur ki.

The poem indicates that

Kandahar Bani became famous due to its voice culture; broad and high pitched tones , forceful expression and the smoothness of its style.

The Nauhar Bani was famous for its sweet and delicate expression. Its attention was on the bol-bant. The Bol-banav must have developed , here , in Layakari.

The Govarhar Bani was known for its deep and sustained breath control.

And, the Daguar Bani developed great expertise in Alapchari, with much attention on the treatment of the Svaras.

During the later centuries when the Gharanas came into being, each Gharana adopted into its own style one or more features from among the four Bani-s. The Bani-s gradually lost their distinctive qualities.

For instance;

:- the Gayaki of Ustad Alladiya Khan of Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana was influenced by Govarhar Bani through its contemplative elaboration , deep breath and smooth glides;

:- the Agra Gharana derived from Nauhar Gharana adopted most of its features, specially the sweetness in its essence;

:- And, the family of Daguar singers and the Beenkars, of course, adopted the Daguar Bani with its insistence on purity and delicately executed meends;

:- The Kirana Gharana seems to be influenced by Daguar Bani.

:- The voice culture of the Kandahar Bani is , of course , a desired virtue of all Gharanas.

Thus, in Dhrupad , the concept of Gharanas seemed to operate as crystallization of ideas about the ways of combining musical styles and features of the bygone Bani-s.

Gharanas

With the disintegration of the Mughal Empire, the political structure of North India fragmented into numbers of small states ruled by Nawabs and Maharajas. With that, the historical tradition of Music of India was rudely disrupted, as the Musicians denied of patronage had to move from Court to Court in search of a livelihood. And, the Musicians were forced to leave behind the theoretical aspects of their Music, but to practice Music as a craft to please their new–found patrons.

An interesting fallout of the political re-arrangement was that each ruler of a small state competed with his rival in studding his court with famed musicians. It is said, rulers of some states borrowed heavily to get hold of top-notch performers. Each ruler was keen to establish the superiority of the Music of his court over that of others. Each would goad his musicians to come up with specialized styles and techniques of singing.

The Music across North India, thus, came to be stratified into styles of various court-music. Each was known as a Gharana (‘family’ or ‘house’), named after its patron-state (such as: Gwalior Gharana, Patiala Gharana, Jaipur Gharana and so on). Each ruler desired to have his very own personalized Gharana of music. And if no particular geographical region can be identified then a Gharana would take the name of the founder; as for instance: Imdadkhani Gharānā named after the great Imdad Khan (1848 -1920) who served in the Royal Courts of Mysore and Indore.

A Gharana, in due course, turned into a symbol of social standing, affluence and power among the rulers.

[A noted musician Ustad Hameed khan explained that, ‘In order for a Gharānā to come into existence, the same style of musical esthetic ideology and collection of musical knowledge should be maintained by a family of musicians at least for three generations. The musical knowledge passed to members of the family and blood relatives under strict manners’. The necessary criteria to recognize a Gharānā is that, the musical knowledge should preserve and only transformed to family members. But it is also accepted that in such cases where the continuity of generations lacks, in that cases Gharānās were continued through the lineage of prime disciples who has complete knowledge particular Gharānā.

The Musicians who suffered most under the changed circumstances were the Dhrupad singers. All along their history they were sheltered by the patronage of Royal Courts. And, their Classic Music of contemplative devotional nature was not favored by the new breed of Nawabs who were looking for entertainment.

And, Dhrupad, rigid and somber as it was, they said, surely was not entertainment. Dhrupad was hard put to survive in a Music world that was dominated by the attractive Khyal, Thumri, Tappa and such other popular styles. The Been and Pakhawaj which were closely associated with the Dhrupad also found it hard to secure patronage.

In the colonial period it was the Nautch-gana that took the central stage in the court entertainment. The Nautch was a popular court dance performed by Nautch-girls in India. The culture of the performing art of the Nautch rose to prominence during the later period of Mughal Empire, and the British East India Company Rule. It spread to the palaces of the Nawabs and of the Princely states; to the pleasure resorts of the senior officials of the British Raj; and , even to the places of smaller Zamindars.

If Dhrupad as a class of pristine pure Music has survived to this day it is primarily due to the dedication, faith , steadfastness and sacrifices of certain families who selflessly dedicated their lives , generation after generation, in protecting , preserving and propagating the ancient Music they inherited from their ancestors in its pure and traditional form. We all owe these families a deep debt of gratitude.

The Classical Dhrupad is today represented by descendants of five major families, each preserving its stylistic music tradition. These have come to be known as the Gharanas of Dhrupad.

Daguar Gharana

The most well known among the Dhrupad traditions or Gharanas is the Daguar Gharana , which is said to have been initiated by the sixteenth century musician Nayak Haridasa Daguar. And , it was preserved and continued since the eighteenth century by a Pandeya Brahmin from Rajasthan, who converted to Islam under the influence of the Sufi Saints.

The Dhrupad of the Daguars’ is said to represent the Daguar Bani of the 16th century. Its performance is characterized by very restrained, contemplative Raga elaboration. It pays much attention to the purity of its music and voice production. The primary emphasis is on accurate, exhaustive and meditative exploration of Raga in the Alap. The composition (Bandish) is often given a lesser amount of time. The overall ambiance of Daguars’ Dhrupad is contemplation, grandeur and a deep sense of devotion.

The singers of the Daguar Gharana are renowned for their high standard of voice culture and purity of vocal delivery. Their presentation is governed by theoretical rules and norms. Most of its singers are well acquainted with music-theories (Shastra).

In the modern times , the Dhrupad of Daguar Gharana is represented the four senior exponents : Ustad Nasir Aminuddin Daguar of Calcutta, Ustad Rahim Fahimuddin Daguar of Delhi, Ustad Zia Fariduddin Daguar of Bhopal and Ustad Hussein Sayeeduddin Daguar of Pune.

Dharbhanga Gharana

The Dharbhanga Gharana is said to have been founded by two brothers Radhakrsna and Kartarama, Gauda Brahmins from Vraja, who later found patronage in the Court of Dharbhanga, in North Bihar.

Dharbhanga Gharana is said to have adopted the Gaurahara Bani as its basic style. But , it also combines in its tradition the robust voice culture of Kandahar Vani and the swiftness of the Nauhar Bani. The distinctive feature of the Dharbhanga Gharana is, therefore, powerful and expressive vocal delivery, combined with very lively, joyful style of performance, skilful Layakari improvisation. There is not much emphasis on restrained, meditative slow movements or on voice culture and such other technical aspects.

The senior musician of the Dharbhanga tradition is Pandit Vidur Mallik of Vrindaban who succeeded the legendry Pandit Ram Chatur Mallik (1906-1990).

Talvandi Gharana

Talvandi Gharana from North-West India is purely a Muslim tradition founded by Chanda Khan and Suraja Khan from Punjab; and, it appears, it is continued in Pakistan.

Since the Talvandi Gharana descended from Muslim tradition, the conventional designations of the various stages of the Alap elaboration and the names denoting Dhrupada performance are in Urdu terms. The entire performance is regarded as an offering to Allah. Yet, the repertoire includes some Hindu devotional songs along with the majority Muslim religious themes. In the Talvandi Gharana, there is full-length Raga Alap ;but , the improvisation in the rendering of the pre-composed Bandish is rather restricted.

Its leading exponent is Ustad Hafiz Khan Talvandivale of Lahore.

Betiya Gharana

The Betiya Gharana of Dhrupad is from Eastern India ; and , it is associated with Royal Court of Betiya in Bihar. It flourished mainly during the nineteenth century, after it was founded by Kathakas (story-tells or bards) from Varanasi (Banaras). A Muslim teacher from Kapi, a disciple of Ustad Haidar Khan of Lucknow, is also associated with the Betiya Gharana.

The Betiya Gharana gathered strength in Eastern India because of its association with the Vishnupur Gharana, a tradition of Dhrupad and Khyal that emerged from the Court at Vishnupur in West Bengal. The Dhrupada of Betiya and Vishnupur Gharana influenced the devotional music that developed in Bengal during 19th century (e.g. Brahma-samgit).

Because of the congregational nature of its rendering, the emphasis of the Dhrupad of the Betiya Gharana is on the composition and the clarity in its presentation. The Alap is kept to a minimum, while the improvisation (Layakari, Bola-bamta) is hardly attempted.

Mathura Gharana

The Mathura Gharana originates from the Dhrupad music of the Vaishnava temples in the Vraja region. The originators of this branch of Dhrupad are said to be Chaturvedi Brahmins from Mathura who having been trained in the temple-music lore and tradition entered the mainstream of classical music.

The Mathura Gharana, similar to the Dharbhanga Gharana, focuses on the composition and on its presentation in powerful, vigorous manner. And, just as in Betiya Gharana, here too the Alap is very short. But, it allows for improvisation though in a limited, straightforward manner. Because of its primary association with temple-rituals, there is a strong emphasis on the clarity in the presentation of the text; the words take preference over musical features.

Over the centuries, the ancient Dhrupad as a musical genre and a structural model has inspired generations of traditions as a classic art -Music and also as a sublime devotional over pouring.

If Dhrupad has survived its misfortunes and re-emerged as a form of chaste Music despite the encircling callousness and neglect verging on destitution, it is mainly because of three factors.

One; it is the intrinsic merit, power, the purity of form and intent of the pristine Dhrupad.

The other is commitment, dedication and sacrifice of generations of families that have protected preserved Dhrupad in its purity; and ensured its propagation as a living tradition.

The parallel, Vaishnava temple – rituals have also helped Dhrupad to continue as a strong tradition.

Rendering of Dhrupad

The musical objects in singing Dhrupad are the exposition and development of Raga; the expressive rendering of the composed text with its melody; and , the demonstration of the melodic sensitivity, rhythmic dexterity and the vocal technique of the singer.

Dhrupad is therefore normally performed by a soloist or by two singers who improvise alternately and combine in performance of the composed song. A solo melodic instrument (traditionally Veena, but now a Sarangi or harmonium may also accompany, in a subdued manner.

The essential accompaniment is the Tanpura or Tambura which provides the Sruti drone throughout the performance. Then there is the Pakhawaj which plays a very significant role in performance

The rendering of Dhrupad which is bound by tradition follows a certain prescribed format in its performance– sequence.

The broad pattern of Dhrupad performance consists two phases. The opening and the major phase is Alap which elaborately explores the chosen Raga in great detail, developing each note with purity and clarity and unfolding the Raga in slow, medium, and fast tempos. Alap usually occupies over two-thirds of the entire performance. In the second phase, a Dhrupad composition is sung to the accompaniment of the Pakhawaj.

The Raga development begins in slow (Vilambit) contemplative elaboration of the Svaras (notes) of the Raga in meditative tones, leading to expansion in the medium (Madhyama) tempo and finally cascading in fast (Dhrut) role of notes. The Alap is the soul and substance of a Dhrupad performance. Alap is performed in stages, with each stage developing the notes in progressively higher notes; but, it is difficult to demarcate the stages.

Ragalapti According to Sarangadeva

Sarangadeva (13th century) in the Third Chapter (Prakirnaka Adhyaya) of his Sangita Ratnakara describes two forms of Raga elaborations: Ragalapti which is Anibaddha – unstructured , not bound either by meaningful words (pada) or by Taala (time units) – free-flowing improvised development and exploration of the Raga (similar to Alap of the present-day) ; and , the other being, Rupakalapti , which is Nibaddha , where melodic improvisation is done with the aid of the words of the song and the Taala ( similar to Bandish of Dhrupad).

Sangitaratnakara (3.189-196) gives the earliest known descriptions of the formal structure of Alap (Ragalapti). According to Sarangadeva, Ragalapti or Ragalapana is the demonstration of the Raga , with emphasis on the important notes and ornamentation of the Raga. And, it has to be developed in four stages. Then he goes on to provide the technical details of Ragalapti. Here, some of the terms he employs have either since gone out of use or have acquired different meanings or connotations.

He says, the Svara (note) on which the Raga is established is known as Sthayi (yatro-praveshyate ragah Svare). This note functions as the initial (Adi-Svara), sectional final (Apa-nyasa, note with which a section of the song ends –Vidari); and final (Nyasa)- (SSR 3.191).

[Here, the term Sthayi term should not be confused with modern Sthayi or the first section of the Dhrupad composition.]

Then he says, the fourth note from this (Sthayi) should be called Dvayardha. There should be a phrase (chalanam – movement) called the opening phase (mukha-chala) about a note lower than the fourth. This is the first section. (SSR.3. 192)

Having made the movement (chalanam) about the fourth (Dvayardha) , there should be an increase in tempo (gati) . This is the second section. The eighth note from the Sthayi is called the Dvi-guna (octave) – (SSR.3.1.193).

The Svaras (notes) occurring between the fourth (Dvayardha) and the eighth (Dvi-guna) are called Ardha-sthita (intervening notes). After having made movements (Chalanam) about the Ardha-sthita, there should be an increase in the tempo (gati). This is the third section. (SSR.3. 194)

Progressing further, there should be an another increase in the tempo . This is the fourth section. Thus, Ragalapti is held by the learned as having these four sections- (SSR.1.195).

Thus, the establishment of the Raga should be made by means of very gradual, clear, circuitous ornamentation (Gamaka or Sthaya) ; and should be pervaded by the vital notes (jivasvara) of the Raga- (SSR.1.196).

In the four sections of Ragalapti as described by Sarangadeva, the Raga development takes place through Sthayi, i.e. from below the fourth (Dvayardha) , around the fourth in the Purvanga and proceeds on to Dvi-guna the eighth note in the Uttaranga.

It is clear from Sarangadeva’s descriptions that the gradual extension of the range from the region of Sthayi the initial note to the eighth note (Dvi-guna) , in a number of stages , with increase in tempo at stage [ moving from the slow tempo (Vilambit) of Sthayi to the fast tempo (Druta) of Dvi-guna] , was the most prominent feature of Ragalapti .

This was, perhaps, the format over which the Alap of the Dhrupad was developed in later times.

Present Practice

The Classical Dhrupad of the present times is usually rendered in three segments : Alap. nom-tom and Bandish (composition).

Alap

Alap is often the most extended part of the Dhrupad performance. Because, it is here that the performer enjoys full freedom to develop and improvise the various facets of the musical elements of the Raga. Alaap is developed in three stages, in three tempos (Laya) : Vilambit (slow), Madhya (medium) and Drut (brisk) .

The Alap in Vilambit Laya (slow tempo) begins in contemplative, meditative elaboration of the notes (Svara) from the lower octave (Purvanga).

The basis of the North Indian Raga is the scale of five or more notes of which Shadja (Sa) is the Adhara Svara (ground note). The melodic expression of the Raga depends on it. Since the Alap is the exposition of the characteristics of the Raga, Shadja is sustained throughout the performance as a drone (together with the fourth or the fifth note). The singer begins each stage by first singing the note Shadja from the middle octave and then proceeds to establish the mood of the Raga by singing the various notes forming that particular Raga. Thus, the development of the Raga proceeds in several phrases each of which returns to the Shadja. Therefore Shadja plays an important part in the structure of the Alap.

The absorbing resonant peaceful musical sounds suggest to the listener the essential nature of the Raga; and then gradually the complete picture is uncovered. The Alap is a free floating pure rendition of the Raga, not fettered by words or time-units. The performer, however, takes the aid of meaning-less musical sounding syllables (om, num, re, ri, na, ta, tom) as a prop to support his elaboration of the Raga and to lend it a personality.

The second stage of Alap would be in Madhya Laya (medium tempo) . Its melodic span and structure are similar to the Vilambit Alap. The singer , here, embarks on the notes of the middle octave. And, the melody will now acquire a faster tempo- Dugun (twice)

The third stage of Alap would be in Drut Laya (brisk tempo).

This is called the Drut Alap. Its melodic structure can be similar to the Alap in medium tempo. but the melody is rendered to a distinct fast tempo- Tigun (thrice) and Chaugun ( four times).; and it escalates into a crescendo as it nears the conclusion.

In the second and third stage the singer may not , however , use the notes of the lower octave ,but keep to the middle and higher octaves. But, this would depend on the nature of the Raga whether it is Uttaranga or Purvanga Pradhana (oriented) Raga.

To sum up ; in the Dhrupad performance, the tempo changes a number of times. As said earlier; initially, the singer begins in slow tempo, which is then quickened as the performance progresses. This is done in stages. The initial tempo is called Thah-Laya; and it is increased in multiples. That tempo, when it escalates is known as Dugun (twice) , Tigun (thrice) and Chaugun ( four times). Sometimes this increase can also be in fractions such as ½ (Adi) or even 1/1-4 (Khud).

[ Please do read a scholarly article on the structure and rendering of the Alap written by Acharya Dr Chintamani Rath .]

Nom tom

The Alap then slides into the more rhythmic nom-tom section, where the Raga develops with a steady pulse , employing meaningless syllables such as nom tom dir tana etc; but, without the binding of the Taala.

Nom tom of Dhrupad is derived from Tena, which is mentioned as one of the Six Angas (limbs or elements) of Prabandha : Svara, Birudu, Pada, Tena, Paata, and Taala.

Tena or Tenaka was described as vocal syllables, meaningless and musical in sound with many repetitions of the syllables or sounds like tenna-tena-tom, conveying a sense of auspiciousness (mangala-artha-prakashaka). It was sung after Ragalapti; but, before the main section of the Prabandha i.e. the Dhruva , which was set in meaningful words (pada) and meter (Chhandas) with appropriate Taala cycles. A similar practice of singing nom tom after rendering the Alap , but before the Bandish came into vogue in Dhrupad.

In the instrumental music, Tena was meant to be played on the Veena in the Nanda type of songs of the Viprakirna class of Prabandha. It gained prominence as Tana or Taanam (played soon after the latter part of the Alapana) in the Veena play of the Karnataka Sangita. The equivalent of Tena in Hindustani instrumental music (particularly Sitar) is the Jor.

The Jor in instrumental music and the Nom tom of Dhrupad both have a simple pulse; but , with no well-defined rhythmic cycle.

The melodic outline of non tom usually echoes the rising and falling arches of the Alap although less attention is paid to development of individual notes. The individuality of nom tom rests mainly on style and vocal technique , rather on form.

Bandish

Prabandha is defined by Matanga as a type of composition that is well structured (Prabhadyate iti Prabandhah). The term Bandish is the re-formed name for Bandha of the Prabandha Music. Bandish in Dhrupad refers to a well structured composition where the words (Pada), music (Raga) and rhythm (Taala) are fixed (Dhruva or Sthayi) in relation to each other, with an even stress on all the three components.

The ancient Salaga Suda class of Prabandha compositions usually had four divisions or sections (Dhatu): Udgraha, Melapaka, Dhruva and Abhoga. And Antara was an additional optional section.

Udgraha is the commencing section of the song. Here the song is first grasped (udgrahyate), hence the name Udgraha; Dhruva is the main body of the song and that which is repeated. Dhruva is so called because it is rendered again and again (refrain); Melapaka is the bridge, the uniting link between the two Udgraha and Dhruva; and, Abhoga is the conclusion of the song. Abhoga gets its name because it completes (Abhoga) the Dhruva. Once the Abhoga has been sung, Dhruva should be repeated.

Since the Dhruva-Prabandha originated from the Salaga Suda class of Prabandha, the two have similar structure. The Dhruva-Prabandha was cyclic song with the formal structure of Udgraha, Dhruva and Abhoga and an additional section Antara, if needed. Here, Antara was in a high register; the first phase of Dhruva served as refrain, repeated at the end of the song and also at the end of the first and the second sections. In all these aspects, the Dhruva Prabandha somewhat resembles the modern Dhrupad.

The Dhrupad (Dhruva-pada) which evolved from the Dhruva Prabandha of the Salaga Suda Prabandha split Abhoga, which was quite lengthy, into two sub parts the Sanchari and the Abhoga. The opening Udgraha and Melapaka were combined into one section called as Sthayi. Thus, the present-day Dhrupad composition usually consists four sections (Dhatu): Sthayi, Antara, Sanchari and Abhoga.

Sarangadeva’s descriptions of Dhruva Prabandha illustrate the remarkable continuity in the musical form over a period of six to seven hundred years, a period during which many changes took place in North Indian Music.

The four Dhatus (sections) of a Dhrupad composition are, briefly:

: – Sthayi – The initial or the opening section of the composition; and, that which establishes the Raga in Madhya and Mandra octaves (Saptaka). Sthayi is often repeated during the performance.

: – Antara–follows immediately after the Sthayi and explores the Raga more extensively, especially accentuating the upper half of the Madhyama ( middle octave) and in the upper half of the octave (Uttaranga) , which is then repeated

: – Sanchari- Allows free movement to explore the Raga fully.

: – Abhoga – Gives a sense of completion to the elaboration ; and rounds off the development stage of the composition.

The percussion accompaniment, the Pakhawaj joins the performance at the commencement of the composition-rendering. Dhrupad compositions are usually set in Chautaal (12 beats cycle) generally performed in slow or medium tempo; those set to Sultaal (10 beats cycle) are performed at a lively brisk tempo ; Tivrataal (7 beats cycle) ; Dhamar (14 beats cycle) or Aditaal (16 beats cycle). A composition in Dhamar-Taal is called Dhamar; and , the one set also set in Dhamar-Taal, performed in medium tempo, describe the Krishna-Gopis enactment of Holi festival is known as Holi-Dhamar. And, the composition set to Jhap-Taal is known as Sadra

After going through the structured sequential rendering of the composition, the performer delves into series of variations and rhythmic improvisations. this section of the performance is marked by a lively interplay between the vocalist and the Pakhawaj player, weaving out patterns of rhythmic improvisations. The playful rivalry or lively dialogue (sawal-javab) between the singer and the instrument player, one kindling and inspiring the other to do one better, is a very entertaining part of the performance.

Improvisations are executed mainly through playing on the words of the text by breaking it up , but keeping intact the group of words so formed . This division of words that synchronize with the beats and cross rhythms is called Bol- Bant. In addition, melodic ornamentations, such as meend and Gamaka are also employed for improvisation and adornment .

Both non tom and Bamt have counterparts in Karnataka Sangita. Nom tom which is derived from the jor and Jhala style of plucked string instruments and from the use of meaningless nom-tom syllables, is analogous to Tanam , a delightful idiom of the Veena which features prominently in the performance of the Ragam-tanam-pallavi and in the instrumental (veena in particular) rendering of Kriti ( but not often in vocal music).

The strict diminution of Laya-bamt has its counterpart in the South Indian Anuloma which may also involve augmentation. The Neraval technique, in which the melody is varied while the rhythm and words of the song remain intact, perhaps bears some resemblance to Bol-bamt of Dhrupad.

The sonorous Pakhawaj contributes brilliantly to the final effect. But, all variations and improvisations must end and come together at the Mukhda, the initial melodic phase ends on the sum.

The Dhrupad concert concludes with auspicious sonorous long drawn out Hari Omkara in a prayerful mood of submission and fulfillment.

Generally, the Classic Dhrupad is distinguished by strict adherence to a performing sequence.

[But in the present times the formats are adopted depending on the performance – duration, class of audience and for other reasons. Following are some of the format options:

(a) A 3-tier Alap, followed by a Chautala composition.

(b) A 3-tier Alap, followed by a Chautala composition, and then by a Dhamara composition in the same Raga.

(c) A 3-tier, or even a single-tier (Tier 1) Alap, followed by a Dhamara composition.

(d) A 3-tier or a single-tier (Tier 1) Alap, followed by a Dhamar composition, and then by a Sula Taal composition in the same Raga.

(e) A 3-tier Alap, followed by a Chautala composition, and then a Sula Taal composition in the same Raga. ]

Gharanas of Instrumental Music

The instrumental music of Sarod, Sitar and Surbahar developed their own system of Gharanas. And, almost all of them flowed from the line of Tansen, his sons and daughter. The more well known of such instrumental-music Gharanas were :

(i) Gulam Ali Sarod Gharānā founded by Gulam Ali (1775?-1850) – disciple of Pyar Khan of Tansen’s son line;

(ii) Jaipur sitar Gharānā of Amrit Sen (1813-1893) , great grandson of Masid Khan of Tansen’s son line;

(iii) Indore Beenkār Gharānā of Bande Ali Khan (1826-1890) , disciple of Nirmal Shah of Tansen’s daughter line;

(iv) Vishnupur Gharānā of Gadhadar Chakravarti (18-19th century ), disciple of Bahadur Khan of Tansen’s son line;

(v) Imdadkhani sitar, surbahār Gharana of Imdad Khan (1848-1920) , disciple of Amrit Sen of Tansen’s son line;

and (vi) the Senia Maihar Gharānā of Ustad Allauddin Khan(1881-1972), disciple of Wazir Khan of Tansen’s daughter’s line (Chapter iii.pdf – Shodhganga)

However during the later times ( say from late 19th century) the separating walls have melted down. The playing of each instrument searched for and adopted the best possible techniques suited to that instrument. And, across instruments each has influenced other instruments. Senia musicians, in particular, spread all over India encouraged inter-mingled experiments with other musicians- Indian and Western. They were more open to various aspects of rendering music as well as new musical instruments and their performance methods.

Beenkars

I cannot resist talking about Beenkars despite the length of this post. Let me put it briefly.

Though Dhrupad is basically a vocal tradition, many musical instruments, particularly the Veena, are closely associated with its music. The Rudra Veena players, generally called as Beenkar Kalawant, made the Dhrupad way of rendering as completely their own style of playing. They took up to elaborate expansion of Raga-Alap – in slow, resonant, long drawn out pure (Shuddha) notes in a grand manner. The Jor-Jhala on Been was developed wonderfully well with improvised and exhilarating rhythmic patterns. The rendering of the structured composition was systematically executed with enterprising variations to synch with contrasting Taala-s to the accompaniment of Pakhawaj.

The Been was associated with the Gwalior singers who came to Akbar’s court. Tansen (1520-1589), the most celebrated of them all, was initially in the service of Raja Man Sing Tomar of Gwalior. Along with the Dhrupad-singing, Tansen had learnt to play on Veena from his Guru Swami Haridas of Vrindaban. Dhrupad was said to be at its peak while Tansen was in the Court of Akbar. It is said; the Dhrupad performers of those times sang as they played on the Veena.

It is said; Tansen’s daughter Saraswathi became a leading player of the Veena, which was her father’s favourite instrument. Her husband, Prince Misri Singh of Rajasthan, a pupil of Swami Haridas, was also an eminent Veena player.

Their descendants were Beenkars as well as Dhrupadiyas. And, they carried forward and developed the traditions of instrumental music (particularly of Veena and Sitar) as well as Dhrupad singing. They came to be known as Seniya Beenkars; and, established what is now known as Seni Beenkar Gharana, the most important musical family in North Indian Classical Music.

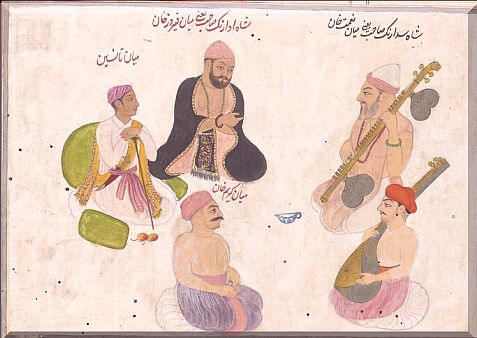

Top row, left to right: Tansen, Firoz Khan ‘Adarang’, Ni’mat Khan ‘Sadarang’ (playing the Been). Bottom row, left to right: Karim Khan (Adarang’s disciple who went to the court of Hyderabad), and Karim Khan’s son, Khushhal Khan ‘Anup’, a celebrity musician at the Nizam’s court. [ Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania, Lawrence J Schoenberg Collection/Wikimedia]

[ Peter Weismiller in his ‘The Been and Beenkars: An Historical Perspective ‘, while writing about Sadarang ((1670–1748)– (Tansen’s great-great-great-grandson) ,mentions

After the reign of Aurangzeb, who ‘destroyed and abolished what little music was left in his court’, better times returned with the reigns of Bahadur Shah (1708- 1719) and (especially) of Mohammad Shah Rangile (1719 –1748), a great patron of music and the last of the Mughals to wield considerable temporal power.

His reign marked a most important turning-point in the history of North Indian music, for his chief instrumentalist, the Beenkar Sadarang (born Nyamet Khan, Tansen’s great-great-great-grandson), initiated a change in performance practice and, ultimately, musical taste. Paradoxically, this change both elevated the Been and its players to new heights of prestige and set forces in motion that would eventually eclipse the Been tradition.

Sadarang did this by refining the Khyal style to a new elegance, teaching new Khyal compositions to his disciples (particularly those outside his family) and having them perform this newly ennobled art before the gratified Mohammed Shah Rangile and his court. Sadarang was rewarded for his innovations by being allowed to perform the Been as a solo instrument, apparently a rare occurrence before this time.

Sadarang bequeathed to his descendants a paramount legitimacy as Beenkars and guardians of a special knowledge. To be sure, much of Sadarang’s knowledge ultimately derived from Haridas Swami and Tansen, and must equally have been a part of their heritage of his Rababiya and vocalist cousins; logically, only those techniques proper to the Been might not have been.

However, it is possible that certain compositions and Ragas, especially newer ones, may have been “hoarded” by particular lineages within Tansen’s descendants. For example; while the raga Bilaskhani Todi -said to have been composed by Tansen’s son, Bilas Khan, on the occasion of his father’s death -is widely known, some among Tansen’s descendants may well have reserved for their own family members rarely-heard (“achop”) Ragas as well as Ragas and compositions they themselves had developed.

A period of chaos followed the reign of Muhammad Shah Rangile. Harold Powers [ The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London, 1980)] informs us: “…many of the Delhi musicians dispersed to regional centres of independent power… The most important patronage outside Delhi was at Lucknow, the court of the Nawabs of Oudh, but other princely states and the newly rich tax-farmers and businessmen in Calcutta also patronized musicians.

*

As regards Khyal; it is said: by the seventeenth century, khayal was established as a form of court entertainment that drew upon both the religious qawwali and the secular cutkula. The form, continued to evolve over the eighteenth century with musicians incorporating features of the dhrupad style within it. It is in this period that khayal performance assumed a structure that bears resemblance to its presentation style today.

During this period, terminology in khayal was rooted in concepts such as Swar, Rag and Taal. The concepts were (and are still) common to music genres across North and South India, e.g. dhrupad and Carnatic music .]

The descendants of Bilas Khan (Tansen’s son) were Rababiyas (players of Rabab) and also Dhrupadiyas. The Sarod tradition originated from the Rababiyas.

These two branches, together, constitute the Seni Gharana. All their members are Beenkars (Veena Player) and Dhrupadiyas.

Apart from Seniyas and their disciples, there were other streams of the Been tradition in different courts of North India. The prominent among them were the Courts at Lucknow, Gwalior and Jaipur. But, all that ended abruptly in 1856 when the British deposed the princely rulers and annexed their states. By the end of the 19th century, Rampur was the only state that supported Musicians; and, was considered – the most important seat of Hindustani classical music.

Miyan Himmat Khan kalāwant (d.c.1845), chief hereditary musician to the last Mughal emperors Akbar Shah (r. 1806–37) and Bahadur Shah Zafar (r. 1837–58). He was the direct descendent of Sadarang, the creator of the khayal.

*

[Been and Rabāb , playing Dhrupad music, were the prime instruments in Indian music about two centuries after Tansen ; and that lasted until 18 century,. But with the change s in the socio-cultural scenery, Been and Rabab which were based in serious and difficult Dhrupad music lost their position to Sitar and Sarod which were amenable to experimentation.

Sarod seems to have appeared in mid-eighteenth century, which is later than Sitar. But, it quickly it acquired the place of the traditional Rabāb which had many limitations for performing khayāl based music.]

With the loss of patronage, change in life-styles and tastes in music, the Beenkars and their art lost their relevance. Been was considered cumbersome, and its music ‘old-fashioned and unattractive’. Its Music had no ‘demand’. The agony was exacerbated with the Beenkars, coming from traditional background, were hopelessly ill-equipped to adapt to the strange new world outside of the Royal Courts.

In modern times, only a few of the most dedicated Beenkars have been able to survive and preserve their traditions.

Given the long and rigorous training required to gain mastery over the instrument; and, bleak prospects of making a living as a Dhrupad singer or Beenkar, few would venture to take a leap into the unknown.

Even though there has been a revival of sorts in listening to Dhrupad and Dhammars over the past few years, the appreciation for this music remains rather tepid. Many therefore feel the future of the Been does not seem particularly bright, unless a Chamatkar occurs.

[For more on Beenkars , please check Peter Weismiller’s very informative article at:

http://www.rudraveena.org/peter_weismiller.html ]

References and Sources

- Singing the praises of the Divine by Selina Thielemann

- Music and Tradition: Essays on Asian and Other Musicsby D. R. Widdess, R. F. Wolpert

- Tradition of Hindustani Music by Manorma Sharma

- Social Mobilisation And Modern Society by Jayanti Barua

- Music Contexts: A Concise Dictionary of Hindustani Musicby Ashok Damodar Ranade

- Saṅgītaśiromaṇi: A Medieval Handbook of Indian Musicedited by Emmie Te Nijenhuis

- Sangitaratnakara :Vol I; Vol II ; Vol III and Vol IV

- Sangitaratnakara : Sanskrit text of the Nartana-adhyaya

- ALL PICTURES ARE FROM INTERNET

ravi panwar

July 26, 2015 at 11:31 am

what an excellent post. well researched and highly informative, please keep up the good work. if you can touch upon khyal and thumri and certain other sections it would be wonderful. thank you

sreenivasaraos

July 26, 2015 at 2:02 pm

Thank you Dear Ravi for reading and for the appreciation.

I trust you read Part One as well . That outlines the the roots of Dhrupad in the Prabandha tradition and in the ancient texts , going back by abot a thousand years.

As regards the Khyal and other innovative types of Music , I may write about it a little later. But, here , I have to find out if there is a way to bind its various forms into a theoritical framework. Most of the times they are spoken in terms of Gharanas. But, that has no theoritical basis.

Let me see. I may have to speak to some one knowledgeble about the roots of those traditions.

Please do read other articles also.

Cheers

kamlesm

October 16, 2015 at 11:28 am

Nice and informative post… pl keep writing I am trying to follow….thanx

sreenivasaraos

October 22, 2015 at 4:10 am

Thank you

You are welcome

Please do read other articles as well

Regards

kamlesm

October 16, 2015 at 11:30 am

I am in search of a small piece of dhrupad (or dhruvpad?) on which I can dance (kathak)

sreenivasaraos

October 16, 2015 at 5:48 pm

Dear kamlesm, You are welcome.

I trust you read both the Parts of the article on Dhrupad.

As regards the Dhrupad songs for Kathak, there are a large number, because Dhrupad has been associated with dance even from the times of Raja Mansingh Tomar (1486-1518). And since then , Kathak has been using those songs for expressional numbers, especially the Rasalila songs. The Damar and Hori songs that are related to Dhrupad are indeed very popular.

As said in the article, Dhrupad was derived from the older song format known as Prabandha. And, Jayadevakavi’s Gita Govinda is the most sublime form of Prabandha. Kathak has adopted many Astapadi-s from Gita Govinda.

Since you asked; the famous dancer Vidyagauri Adkar has posted on the net some of her performances of Kathak dance to the Dhrupad songs. Please check the following links. I trust you will find them enjoyable and educative.

http://www.mp3tunes.mobi/download?v=V1RFenNZZkl5Vms=

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Lzs13fVTRA

Regards

kamlesm

October 30, 2015 at 7:00 am

Thank you very much, indeed i was surprised on recieving a reply…thnx once again

kamlesm

October 30, 2015 at 7:04 am

now days i am not hearing anything related to these rich music traditions on TV anymore, This is a very sad affair in our country. Also not much update is available about Darbhanga gharana?? It was a great seat on music few decades ago?

sreenivasaraos

November 1, 2015 at 11:42 pm

Dear Kamlesm Thanks ; you are welcome

Please do read the other articles as well

Regards

DKM Kartha

March 25, 2017 at 5:55 pm

Thank you for this elaborate article! Very informative. I saw a minor typo, which you might want to correct: “Dhrupad flourished as the principle music format ….” I think that the 5th word should be “principal” in the sense of “main” or “chief.” All the best,

DKM Kartha

sreenivasaraos

March 25, 2017 at 6:13 pm

Dear Kartha

Thanks for reading; and, reading it closely.

Yes ; I agree. Kind of you to point it out.

I shall correct the error . Thanks again

Please do read the other articles as well ; and kindly let me know

Regards

tmchoudhary1

May 13, 2020 at 7:00 pm

Just discovered this site. It is a minefield of material , history and analysis of Indian arts. Above all it was very inspiring and motivated me to dig deep into south Asian sensibilities. Thanks

sreenivasaraos

May 14, 2020 at 1:25 am

Dear Shri Choudhary

Thank you for the visit; and for the appreciation

Please read the other articles as well ; and let me know

Regards

Shailaja Khanna

June 24, 2021 at 4:58 am

Very interesting post but i must correct a point – Raja misri chand was a beenkar of the kandhar bani, considered of superior musical lineage to even Mian Tansen which is why his beenkar line, linked with Saraswati, Tansen’s daughter, were the seniors at court, senior to the rabbabiya male line of Mian Bilas khan. The beenkar line included Sadarang and Adarang . Mian Himmat Khan whose photo you used was the direct descendent of Sadarang, the creator of the khayal.

sreenivasaraos

June 24, 2021 at 10:09 am

Dear Shailaja Khanna

Thank you for the visit; and for the observations

Since you mentioned Sadarang, I have included a short note about Sadarang.

As regards the husband of Saraswathi (I.e.. the son-in-law of Tansen), his name is usually mentioned as Misri Singh (grandson of Raja Samokhan Singh of Kishangarh)

I have accordingly mentioned his name as Misri Singh

*

He is said to be the originator of the instrumental tradition that came to be known as the Senia Gharana

As said earlier ; Misri Singh was the grandson of Raja Samokhan Singh.

And, Raja Samokhan Singh was a famous Beenkar. He belonged to Kandahar region. Thus, his style of singing came to be known as Kandahar Bani. This Bani was rich in its variety. Its gait was majestic and robust, using heavy and vigorous Gamakas, expressive of valor. In contrast to Gaudiya or Govarhari Bani , it usually was not sung in slow tempo.

As I understand, Senia relates to a style of playing instrumental music; while Kandhar bani known for its rich voice culture; broad and high pitched tones , forceful expression and the smoothness of its style relates to vocal rendering of one of the Dhrupad schools.

Thank you again

Please keep talking

Regards

Shailaja Khanna

December 13, 2021 at 2:50 am

No, senia refers to the tradition of music descended from Tan SEN. Yes it was an instrumental tradition but Tansen himself was a danger. The khandar vani tradition was not only vocal, as you see the main representatives were instrumentalists.