1. Natya-Shastra is a detailed compendium of technical instructions about the performing arts. It was meant as a practical manual for production of successful theatrical performances, which included music and dance as well as acting. It was also intended as a guide to the poet and to the performer, alike.

As Prof. Adya Rangacharya stated in his The Natyasastra: English Translation with Critical Notes

The eminence of the Natyasastra lies not merely in the fact that it was the first book on the subject on theatrical art; but that, it was the first comprehensive treatise on Dance, Drama and Music; and , it marks the origin of our dramatic tradition. It laid down the essentials of the Drama as a representation of the ways of the world; the nature and attitudes of the people; their ways of behavior and manners of speech. It also provided a framework for the Drama by highlighting its essential ingredients:

(1) a playwright who has vision to the grasp of things and has the capacity to articulate that in an interesting way, through speech and action;

(2) the story that holds the attention of the audience;

(3) a virtuoso director who can transform a script into a dramatic performance;

(4) the set of skilled artists with clarity of speech and endowed with talent to give form and substance to the dream of the playwright and the vision of the director; and , not the least ,

(5) the perceptive , intelligent and cultured spectators who appreciate and enjoy a good performance.

1.1. The text is in the form of elaborate dialogues between the author and a group of Munis , sages , who wished to know about Natya-Veda, the knowledge of the performing arts such as dance, music and drama. The author, in response, presents a detailed inquiry in to the various facets of drama including its nature; its origin; its theories; techniques of the theater with all its components of speech, body-language, gestures, costumes, décor and the state of mind of the performers, apart from rituals, architecture of theater etc.

Written in archaic form of Sanskrit, the text consists about six thousand (5,569 – to be exact) sutras or verse-stanzas spread over thirty-six chapters. Some passages are in prose.

Because the Natyasastra has about 6,000 verses, the text is also known as Sat-sahasri. The later authors and commentators (Dhanika, Abhinavagupta and Sarada-tanaya) refer to the text as Sat-sahari; and, its author as Sat-sahasri-kara.

But, the text having 6,000 verses is said to be a condensed version of an earlier and a larger text having about 12,000 verses (dwadasha_sahasri). It is said; the larger version was known as Natya- agama and the shorter as Natya-shastra.

[ Please click here for The Natyasatra – A treatise on Hindu Dramaturgy and Histrionics Ascribed to Bharata Muni; Translated into English by Manmohan Ghosh; Published by Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta – 1951]

2. Though the Natya-Shastra speaks of theater (natya), it actually encompasses all forms of art expressions. The text, in fact, claims that there is no knowledge, no craft, no lore, no art, no technique and no activity that is not found in Natya-Shastra (1.116).

न तज्ज्ञानं न तच्छिल्पं न सा विद्या न सा कला । नासौ योगो न तत्कर्म नाट्येऽस्मिन् यन्न दृश्यते ॥ ११६॥

The reason that theater-arts were discussed specifically, is that, in the ancient Indian context, drama was considered the most comprehensive form of art-expressions. Further, at the time the Nataya Shastra was compiled, the arts of poetry, dance, music and drama; and even painting, sculpture and architecture were not viewed as separate and individualized streams of art forms. Natyashastra presented an integral vision of art, which blossomed in multiplicity.

It was only during the later periods these art-forms developed into independent art-expressions. Similarly, even the other minor forms of Drama , such as: Opera, Poetic-drama, realistic plays and so on, later evolved and grew apart, assuming independent identities.

[Vishnudharmottara (Ca. sixth century) asserted that painting and sculpture without the knowledge of the Drama and the Dance would not have much depth; and, that Drama and Dance, in turn, do require a knowledge of music and of the songs, which again is dependent on mastery over languages – both Sanskrit and Prakrit – with a thorough understanding of the elements of prose, poetry, grammar, meter, prosody etc. It thus underlines the interdependence of the arts.]

All art expressions were viewed as vehicles of beauty, providing both pleasure and education, through refinement of senses and sense perceptions. The object of the drama was to show men and women the proper way to live, a way in which one could live and behave, so that one might be a still better person.

“A play shows your actions and emotions. Neither gods nor demons are depicted as always good or always evil. Actually, the ways of the world as represented here are not only of the gods but also of yours. It gives you good advice; it gives you enlightenment and also entertainment. It provides peace of mind to those who afflicted with miseries, sorrow, grief or fatigue. There is no art, no knowledge, no yoga, and no action that is not found in Natya .”- (Natya-Shastra 1: 106=07; 112-16)

na taj jñānaṃ na tacchilpaṃ na sā vidyā na sā kalā । nāsau yogo na tatkarma nāṭye’smin yanna dṛśyate ॥ 116॥

[ Kalidasa remarked : ‘Drama, verily, is a feast that is greatly enjoyed by a variety of people of different tastes

– Natyam bhinnaruchir janasya bahuda-apekshym samaradhanam. ]

Bharatha explains: when the nature of the world possessing pleasure and pain both is depicted by means of representations through speech, songs, gestures , music and other (such as, costume, makeup, ornaments etc ) it is called Natya. (NS 1.119)

yo’yaṃ svabhāvo lokasya sukha duḥkha samanvitaḥ । som gādya abhinaya ityopeto nātyam ity abhidhīyate ॥ 119॥

Thus, according to Bharata, the Drama is but a reflection or a representation of the actions of Men and women of various natures (Prakrti) – avastha-anikrtir natyam . That is to say; the Drama, in its various forms of art, poetry etc , strives to depict the infinite variety of human characters .

That is the reason; Bharata says, one should study the various human habits and natures (Prakrti) on which the art of Drama is based. And, for which the world, the society we live in is the most authoritative source of knowledge (Pramana) . All those involved with the Drama should realize this truth – (NS: 25.123)

Nana-sheelah prakutyah sheele natyam pratihitam / tasma-loka-pramane hi vigneyam natya yo krubhihi // (NS: 25.123)

Having said that; the theater was conventional; yet, imaginative. The costumes and make up were stylized and symbolic; and, not what is commonly seen on the city-streets. In any case, Natyashastra requires a performer to present much more than an external representation of the character, such as correct speech, gesture etc. His/ her stage performance will have to go far beyond technical skill, in order to be believable and accepted by the spectators.

There is, however, not much discussion about scenery; perhaps because scenery was used sparingly.

Theater had a sacred significance. Prayers and rituals were conducted and the stage was consecrated before the commencement of the play ( Purvanga) .

*

Natyashastra (6.10) provides a comprehensive framework of the Natya-veda, in a pellet form, as the harmonious combination (saṅgraha) of the various essential components that contribute towards the successful production of a play.

Rasā bhāvāhya abhinayāḥ dharmī vṛtti pravṛttayaḥ । siddhiḥ svarās tathā atodyaṃ gānaṃ raṅgaśca saṅgrahaḥ ॥ 6.10॥

Bharata also mentions the five elements of the plot (artha-prakrti) of the Drama as :

- the seed (Bija);

- the expansion or the intermediate point which links to the next (Bindu);

- the episode (Pataka);

- the incident in the episode (Prakari) and

- the dramatic outcome (Karya).

These are to be used according to the main Rasa of the play and the prescriptions of the Shastra.(NS: 19.21)

Bijah Bindu Pataka cha Prakari karyameva cha / Artha-prakrutyah pancha tatva yojya tata vidihi // (NS:19.21)

As regards the success of the play (Siddhi), it is said, the successful production (Siddhi) of a play enacted on the stage (Ranga) with the object of arousing joy (Rasa) in the hearts of the spectators involves various elements of the components of the actors’ gestures, actions (Anubhava) and speech (vachika); bringing forth (abhinaya) their intent, through the medium of theatrical (natya-dharmi) and common (Loka-dharmi) practices; in four styles of representations (Vritti-s) in their four regional variations (pravrttis) ; with the aid of melodious songs accompanied by instrumental music (svara-gana-adyota).

The assembly of spectators with different tastes and levels of appreciation should all be able to enjoy the play. Therefore, Bharata instructs that a play should be such that it caters to the interests and dispositions of varied class of men and women; the young and the old, with each class looking for its own favorite type of entertainment . And, it is upon such versatile ability that the success of a play depends. The play-production, thus, was aimed to satisfy the happy, responsive spectators and enthuse them to visit the theater more often.

Bharata, in a way, sums up the virtues and merits of Nataka , a dramatic work, that captivates the hearts of the spectators and brings glory to its playwright , producer and the actors .

The work of art that satisfies all classes of spectators ; and is a happy and enjoyable composition, which is graceful on account of being adorned with sweet and elegant words; free from obsolete and obscure meaningless verbose ; easily grasped and understood by the common people ; skillfully arranged ; interspersed with delightful songs and dances; and, systematically displaying varied types of sentiments in its plot devised into Acts, scenes, junctures etc.

mṛdu-lalita-padārthaṃ gūḍha-śabdārtha-hīnaṃ ; budha jana sukha bhogyaṃ, yuktiman – nṛtta-yogyam । bahu rasa kṛta mārgaṃ , sandhi-sandhāna-yuktaṃ bhavati jagati yogyaṃ nāṭakaṃ prekṣakāṇām ॥ 16.130॥

***

Bharata elaborates (NS.27.57-61) :

The young are keen on the portrayal of love; and, those after money relish scenes depicting acquisition of wealth. And, the ones who love adventure delight in the terrible and odious acts of battle and combats; whereas the old and pious always praise the enactment of well known tales and legends from the Puranas (epics) lauding the virtues and good deeds ; the devout look for philosophical and religious aspects ; and, those disinterested in the mundane seek liberation (moksha) . The common folks, the women, children and the dimwitted lap up with relish comic situations evoking laughter and fun, attractive costumes and make up.

Apart from these types, Bharata also mentions an elite class of appreciative spectators with refined tastes and deep interest in the technical aspects of production. Such connoisseurs were also aware of the theatrical traditions and conventions of performance on the stage. These were the well-informed class who cared more about the aptness of the techniques of performance, critically evaluated the merits (guna) , the defects (dosha) and the success of the theatrical performance as a whole.

Then, there were also the artists specialized in different branches of music and dance; the scholars who relished subtle nuances in the rendering of speech and the lyrics of the songs; and, there were the accomplished courtesans who were experts in presenting alluring and delectable performances .

All such elite class were the cream of spectators, for whose approval and appreciation the whole of theatrical group collectively and individually looked forward with great hope and fear.

The producer of the Drama had also the onus to please the patron who sponsored and financed the play –production and display.

Nānāśīlāḥ prakṛtayaḥ śīle nāṭyaṃ vinirmitam । uttamā-adhama madhyānāṃ vṛddha bāliśayo ṣitām ॥ 57॥

Tuṣyanti taruṇāḥ kāme vidagdhāḥ samayātvite । artheṣvarthaparā ścaiva mokṣe cātha virāgiṇaḥ ॥ 58॥

Śūrāstu vīra raudreṣu niyuddheṣvāhaveṣu ca । dharmā akhyāne purāṇeṣu vṛddhā stuṣyanti nityaśaḥ ॥ 59॥

Na śakyamadhamairjñātumuttamānāṃ viceṣṭitam । tattva bhāveṣu sarveṣu tuṣyanti satataṃ budhāḥ ॥ 60॥

Bālā mūrkhāḥ striyaścaiva hāsyanaipathyayoḥ sadā । yastuṣṭo tuṣṭimāyāti śoke śokamupaiti ca ॥ 61॥

Abhinavagupta observes Drishta-phala [visible fruits] like banners (pataka) or material rewards do not indicate success of a play production. Real success is achieved when the play is performed with skilled precision, devoted faith and pure concentration. To succeed, the artist must immerse the spectator with pure joy of Rasa experience. The spectator’s concentrated absorption appreciation and enjoyment is indeed the success.

Dhananjaya in his Dasarupaka remarks that responsive spectators, fired by enthusiasm and imagination, contribute to the success of the play in the manner of ‘children playing with clay elephants ‘. ” When children play with clay-elephants, etc., the source of their joy is their own utsaha (enthusiasm). The same is true of spectators watching and almost sharing the heroic deeds of characters , say like, Arjuna and other heroes on the stage.”……

Kridatam mrnrnayair yadvad balanam dviradadibhih / svotsahah svadate tadvac chrotrnam Arjunadibhih.

**

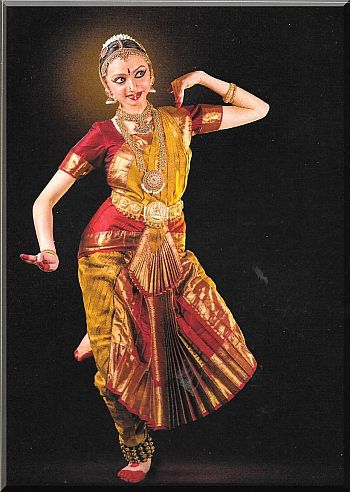

2.1. The text employs Natya as a generic term, which broadly covers drama, dance and music. It does not treat dance as a separate category of art form. Bharata while dealing with Angika-abhinaya (body-language) speaks of nrtta, pure movements that carry no meaning- as compared to Abhinaya (literally meaning that which carries the meaning forward towards the audience) i. e. gestures that convey specific meaning. Nrtta was, in fact, meant to provide beauty, grace and a certain luster to the performance. The postures of the nrtta (called karanas) were classified by Bharata as tandava and sukumara, to convey vigor and grace.

[ Nandikeshwara (perhaps a later author who, for some reason, assumed the name of an ancient figure/person ?), author of Abhinaya_darpana, is believed to be the first to recognize dance as an independent art. He called it natanam; and classified it into nrtta (Pure dance), nrtya (abhinaya – expression- aspect) and natya (combination of nritta and nrtya with a dramatic element to it).

Dhananjaya in his Dasarupa, while drawing a distinction between nrtta and nrtya , explains the term nrtta as that which depends on rhythm and tempo – nrttam tala-layam ashrayam (DR. 1. 13) ; and, nrtya as that which is dependent on emotion – Bhava-ashrayam nrtyam (DR. 1. 12).

As mentioned earlier, Nandikeshwara explained Natya as the combination of nrtta and nrtya .]

3.1. It is said that the text which we know as Natya-Shastra was based on an earlier text that was much larger. And, many views presented in Natya-Shastra are believed to be based on the works of other scholars. There are frequent references to other writers and other views; there are repetitions; there are contradictory passages; there are technical terms, which are not supported by the tradition.

[ It appears there were texts on Drama even much prior to Natyashastra. Panini (Ca.500 BCE) the great Grammarian, in his Astadhyayi (4.3.110-11), mentions two ancient Schools – of Krsava and Silalin – that were in existence during his time –

Parasarya Silalibhyam bhikshu nata-sutreyoh (4.3.110); karmanda krushas shvadinihi (4.3.111).

It appears that Parasara , Silalin , karmanda and Krsava were the authors of Bhikshu Sutras and Nata Sutras. Of these , Silalin and Krsava were said to have prepared the Sutras (codes) for the Nata (actors or dancers). At times, Natyashastra refers to the performers (Nata) as Sailalaka -s . The assumption is that the Silalin-school , at one time, might have been a prominent theatrical tradition. Some scholars opine that the Nata-sutras of Silalin (coming under the Amnaya tradition) might have influenced the preliminary part (Purvanga) of Natyashastra , with its elements of worship (Puja).

However, in the preface to his great work Natya-shastra of Bharatamuni (Volume I, Second Edition , 1956) Pundit M. Ramakrishna Kavi mentions that in the Natyavarga of Amara-kosha (2.10.12) there is reference to three schools of Nata-sutra-kara : Silalin ; Krasava; and, Bharata .

It appears that in the later times, the former two Schools (Silali and Krasava) , which flourished earlier to Bharata , went out of existence or merged with the School of Bharata; and, nothing much has come down to us about these older Schools. And, it is also said, the Bharata himself was preceded by Adi-Bharata, the originator and Vriddha (senior) Bharata. And, all the actors of whatever earlier Schools, later came to be known as Bharata-s. ]

3.2. These factors lend support to the view that Natya-Shastra might have been the work of not one single author but of several authors, spread over a long period of time.

Ms. Kapila Vatsyayan, a well known scholar, however, observes that the text projects an integrated vision and a unity of purpose. She points out many instances of reference to later chapters in the text, and says they are indicative of the coherent and well knit organic nature of the work.

For those reasons, she concludes, Natya-Shastra might well be considered as the work of a single author or of a single tradition.

4.1. Rasa, as discussed in Natyashastra, meant aesthetic appreciation or the joy that the spectator experiences. As Bharata says , Rasa should be relished as an emotional or intellectual experience : na rasanāvyāpāra āsvādanam,api tu mānasa eva (NS.6,31) .

The Nāṭyashāstra states that the goal of any art form is to invoke such Rasa.

[Bharata explains Rasa as an experience that can be relished – like the taste of food – Rasyate anena iti rasaha (asvadayatva), which is associated with palate (ability to distinguish between and appreciate different flavors) . Yet ; the aesthetic senses that are primarily engaged with a theatrical presentation are only the eye and the ear. The senses of taste, touch and smell are not , generally, associated with the type of ones experience that Bharta talks about while witnessing a Drama. These are personal or individual experiences. But, Rasa, the aesthetic experience enjoyed by all the spectators , in a play, in common, is mainly through two senses : the eye and the ear. That , perhaps , is the reason why Bharata says that the Rasa in a play should be relished only as an emotional or intellectual experience.]

Bharata’s theory of Rasa was crafted mainly in the context of the Drama. After naming the eight Rasas, he says ‘these are the Rasas recognized in Drama’ – nāṭye rasāḥ smṛtāḥ – (N.S 6.15).

śṛṅgāra-hāsy-akaruṇā raudra-vīra-bhayānakāḥ । bībhatsa-ādbhuta-saṃjñau cetyaṣṭau nāṭye rasāḥ smṛtāḥ ॥ 15॥

In the prose-passage following the verse thirty-one of Chapter six, Bharata commences his exposition of Rasa, saying: I shall first explain Rasa; and, no sense or meaning proceeds without Rasa (Na hi rasa-adrate kaschid-arthah pravartate).

tatra rasāneva tāvadādāvabhivyākhyāsyāmaḥ । na hi rasādṛte kaścid arthaḥ pravartate

He , then focused on the dancer’s or actor’s performance and effort to convey the psychological state , which the character is experiencing , to the spectator, in order to create Rasa – the aesthetic appreciation or enjoyment of the art – in the heart and mind of the spectator.

The famous Rasa-sutra or basic “formula”, in the Nāṭyashāstra, for evoking Rasa, states that the vibhāva, anubhāva, and vyabhicāri bhāvas together produce Rasa: tatra vibhāvā-anubhāva vyabhicāri saṃyogād rasa niṣpattiḥ ।

Bharata elaborated the process of producing Rasa in terms of eight Sthayi Bhavas – the principle emotional state of the character expressed by the performer with the aid of Vibhava (the cause) and Anubhava (the enactment) ; thirty-three Vyabhicāri (Sanchari) bhāvās – the transient emotions; and, eight Sattivika-bhavas – the involuntary physical reactions.

Among these Bhavas, the more important ones are said to be vibhāva and anubhāva , which invoke the Sthāyi bhāva, or the principle emotion at the moment. Such elements that are employed to convey the psychological state of the character, thus, in all, amounted to forty-nine or more.

[The Sattvika , the involuntary–reflexes (such as being stunned, going pale , stammering, shedding tears etc.,) were perhaps meant to introduce a realistic style of acting – suited to the situation as also to the nature, psychological state and the social standing of the character , as compared to the purely conventional style .]

It is explained; they are called Bhavas because they happen (Bhavanti); they cause or bring about (Bhavitam); and, are felt (bhava-vanti). Bharata explains that Bhavas effectively bring out the dominant sentiment of the play – that is the Sthāyibhāvā – with the aid of various Bhavas , such as words (Vachika), gestures Angika), costumes ( Aharya) and bodily reflexes (Sattva) – for the enjoyment of the good-hearted spectator (sumanasaḥ prekṣakāḥ) . Then it is called the Rasa of the scene (tasmān nāṭya rasā ity abhivyākhyātāḥ).

Nānā bhāvā abhinaya vyañjitān vāg aṅga sattopetān / Sthāyibhāvān āsvādayanti sumanasaḥ prekṣakāḥ / harṣādīṃś cā adhigacchanti । tasmān nāṭya rasā ity abhivyākhyātāḥ //6.31//

In brief; Abhinaya is the art of communicating bhāva (emotion) to produce Rasa (aesthetic enjoyment). In other words, it is the Bhavas that produce Rasa; and, it is not the other way.

The Rasa theory of the Nāṭyashāstra is considered one of its most important contributions, with several scholars over the centuries , until today, discussing and analyzing it extensively.

Thus, Bharata’s concept and derivation of Rasa was mainly in the context of the Drama. They all are related to concrete and tangible emotions, based upon human experiences. There is no mysticism whatsoever here. That concept-of the enjoyment by the recipient spectator – as also his views on the Gunas and Dosha, relating to the scripting and enacting the play, were later enlarged , transported and adopted into Kavya as well. In either case, the human element was never lost sight of ; and, the spectator or the avid reader remained at the center of art-experience.

*

Bharata, initially, names four Rasas (Srngara, Raudra, Vira and Bhibhatsa) as primary; and, the other four as being dependent upon them . That is to say ; the primary Rasas, which represent the dominant mental states of humans, are the cause or the source for the production of the other four Rasas.

Bharata explains that Hasya (mirth) arises from Srngara (delightful); Karuna (pathos) from Raudra (furious); Adbhuta (wonder or marvel) from the Vira (heroic); and, Bhayanaka (fearsome or terrible) from Bhibhatsa ( odious).

śṛṅgārāddhi bhavedd-hāsyo raudrācca karuṇo rasaḥ vīrāccaiv-ādbhuto-utpattir-bībhatsācca bhayānakaḥ ॥ 6.39॥

But, effectively, the eight Rasas listed in Nāṭyashāstra are well accepted. Some scholars remark that the distinction of four basic Rasas ; and , their associate four Rasas is a mere technical detail that the spectators may not be interested in.

śṛṅgāra hāsya karuṇā raudra vīra bhayānakāḥ । bībhatsā adbhutasaṃjñau cetyaṣṭau nāṭye rasāḥ smṛtāḥ ॥ 6.15॥

Later, by the time of Abinavagupta Shanta rasa came into discussion; and, eventually was recognized . Thus , concept of Navarasasa was accepted. (for more on discussion about Shantha Rasa , please click here). Later on Vatsalya , Bhakthi and such others were also named as Rasas. Thus the number of Rasas is not mere nine or eleven , it could be more.

**

4.2. Bharata gave a definite structure to the drama; and said every play must portray and convey a dominant Rasa; and , each of the eight rasas providing enjoyment to the audience. A Rasa depends on the type of the story and sort of the hero. According to Dhananjaya, hero (neta), story (vastu) and rasa (artistic enjoyment) constitute the essential ingredients of a drama – Vastu neta rasas tesam bhedako .

Natya-Shastra strives with a single pointed devotion to bestow an artistic form and content to what was still then a vulgar source of entertainment. Bharata could say with pride “parents could watch a dramatic performance in company of their sons and daughters-in-law.”(Natya-Shastra– 24.297)

5.1. That leads us to the question who was this author? Was Bharata his name ? Was Bharata the name of his tribe? Or, was it a clever acronym?

There are, of course, no clear answers to these questions. The author made no attempt to reveal his identity. The book, as I mentioned earlier, is in the form of dialogue between Bharata and the sages. The author was explaining the broad parameters, the basic principles and techniques of theatrical art as they then existed. He was not expounding the text as if it were his discovery or as his personal position. He was lucidly and systematically explaining a tradition that was alive and vibrant. These factors lead us to believe that Bharata, whoever he was, might have been a practicing- well informed-leading performer of his time, belonging to a certain tradition . Bharata perhaps belonged to a community of artists, actors, dancers, poets, musicians who shared a common heritage and common aspirations.

5.2. From the prologue, couched in mythological language and imagery, it appears, Bharata was also a teacher and a preceptor of a school or an academy. He had a number (100?) of sons and pupils each of them being an accomplished performer or a learned theoretician. He produced plays with their assistance; by assigning each one a specific role.

It is very unlikely there were ‘theatrical Companies’, as such . Perhaps the family of Bharatas – producers, directors (Sutradhara) and actors, as also their disciples of various talents and ranks, managed the theater as a group, under the leadership of the senior Bharata being in charge. It does, also, appear that the actors of various ranks of importance, dancers, musicians, assistants and minor functionaries did receive a systematic training in their craft.

Such a troupe leader (Bharata) might also have been the one who assigned roles in a play; and, taught the rules of the art/craft to the actors and actresses. His chief function seems to have been mostly supervisory. He might also have been involved in the design and structure of the theater hall (Natya-shala)

Thus, the Bharata, whoever he might be, should have been one capable of performing all those diverse and difficult tasks, with a sense of responsibility and commitment. Besides, he should have been one who was sensitive to human frailty; and, also conversant with the language customs and nature of people of different classes and regions,

The term Bharata perhaps initially referred to such a multi-talented virtuoso; and also, a producer / director of plays. The author of the Natya-Shastra was perhaps one such “Bharata”.

5.3. Incidentally, the text – in its chapter 35 – Bhumika vikalpa – provides a sort of elaborate explanation of the term Bharata, as : one who conducts as the responsible leader of a performance – as producer , director and stage manager – who is required to be an expert not only in acting but also in all those arts which together constitute a performance – by acting in many roles, by playing many instruments and by providing many accessories – is called Bharata – (Natya-Shastra 35: 63-68, 69-71).

[ In this connection, I shall speak of the qualities of a Director. An enumeration of his qualities will constitute these characteristics; they are: First of all, he should possess knowledge of characteristics of everything concerning the theater, desirable refinement of speech, knowledge about the Tala, rules for timing of songs, and of the theory relating to musical notes and to the playing of musical instruments.

63-68. One who is an expert in playing the four kinds of musical instrument, well-trained in rites prescribed in the Sastras, conversant witli the practices of different religious sects and with polity and the science of wealth, expert in the manners of courtezans (kama-shastra), and in poetics(kavya-shastra) , knows the various conventional Gaits and movements (gati-prakara), throughly appreciates all the States (bhava) and the Sentiments (rasa), is an expert in producing plays, acquainted with various arts and crafts, conversant with the rules of prosody and the metrical feet (chhandas shastra), and is clever in studying the different Sastras, acquainted with the science of stars and planets and with the working of the human body, knows the extent and customs of the earth, its continents and divisions, mountains and people, and the descendants of different royal lines (prasutivit) , is fit to attend to the Sastras relating to his works, capable of understanding them and of giving instruction [on the subjects]; should be made a teacher {acharya) and a Director (Sutradhara)

69-71. Now listen to me speaking about the natural qualities of a Director. He should be possessed of memory , intelligence and judgement; should be patient, liberal, firm in his words, poetical, free from any -disease, sweet [in his manners], forbearing, self-possessed, sweet-tongued, free from anger, truthful, impartial, honest, resourceful (pratimanta) and free from greed for praise.

– The Natyashastra – translation by Manmohan Ghosh – 1950 – (page 546) – Chapter 35. Bhumika vikalpa – Verses 63 to 71 ]

5.4. The author of the Natya-Shastra is also often addressed, in later times, as Bharatamuni. Shri Adya Rangacharya, a noted scholar, remarks. “The usual trappings of a muni (sage) are nowhere mentioned”. On the other hand, his sons misused their knowledge and ridiculed the sages (ṛṣīṇāṃ vyaṅgya-karaṇaṃ); and the enraged sages promptly cursed them “as due to pride ( madonmattā ) in your knowledge you have taken to arrogance (a-vinayam) ; your corrupt-knowledge (ku-jnana) will be destroyed (nāśameṣyati )” — (Natya-Shastra 36: 32 – 38).

yasmājjñāna-madonmattā na vetthā vinayāśritāḥ । tasmād etaddhi bhavatāṃ kujñānaṃ nāśameṣyati ॥ 38॥

5.5. Bharata recounting this sad episode, cautions the community of artists not to overreach themselves, in arrogance, just because the art had bestowed upon them a special position in the society . The art that empowered them, he counsels, derives its strength from the society; and, the artists, therefore, have a special responsibility to cultivate discipline, self-restraint and humility (Natya-Shastra 36: 29 – 38).

5.6. Bharata refers, repeatedly, to the power that creative art is capable of wielding; and to the responses – both subtle and intense – they can evoke in the hearts of men and women. He asks his sons and disciples not to destroy drama which has its origins in the hoary past of the Vedas and their upangas (supplementary texts). He implores them to preserve the dramatic art by teaching it to their disciples ( siṣyebhyaśca tadanyebhyaḥ); and to spread the art by practicing it (prayacchāmaḥ prayogataḥ ).

jānīdhvaṃ tattathā nāṭyaṃ brahmaṇā sampravartitam । śiṣyebhyaśca tadanyebhyaḥ prayacchāmaḥ prayogataḥ ॥ 36.49॥

mā vai praṇaśyatāmetan nāṭyaṃ duḥkha-pravartitam । mahāśrayaṃ mahāpuṇyaṃ vedāṅgo-upāṅga -sambhavam ॥ 36.50॥

5.7. [The attempt to explain Bharata as an acronym for three syllables Bha (bhava), Ra (raga) and Ta (tala) , somehow, does not seem convincing at all. At the time Natya-Shastra was composed, music was discussed in terms of pada (words), svara (notes) and tala (rhythm) forming components of a certain style of music called gandharva said to have been derived from Sama. Bharata talks about structured and unstructured music: bhaddha (structured like a verse or a stanza; and with rhythm) and anibhaddha (unstructured – without rhythm, analogues to the present-day aalap). The term raga did not come to prominence until Matanga (about sixth century), in his Brihaddesi, elucidated the categories of muchchhanas and jatis; and introduced the term raga and outlined its concept.]

5.8. Thus, the author of the Natya-Shastra, whoever he might be, comes across as a multi-talented virtuoso, a person of great learning, culture and rooted in good tradition (sampradaya, parampara). He was well grounded not merely in Vedic learning and its ethos, but also in kavya (literature) , fine arts, Ayurveda (medicine), jyothisha (astrology), ganitha (mathematics), vastu-shilpa (architecture) and hathayoga. His understanding of the human anatomy- particularly the motor and sensory systems and the joints; the relation between the physical stimulus and psychic response; as also the relation between psychic states and expressions through physical movements were truly remarkable.

6.1. As regards its date, it is not clear when the Natya-Shastra was initially articulated. There are, of course, a host of debates concerning the date of composition of the text. I however tend to go along with the argument that Natya-Shastra was a post Upanishad text; but, it was prior to the age of the Puranas; and certainly much earlier to the age of classic Sanskrit drama. The following, briefly, are some of the reasons:

*. Natya-Shastra describes itself as Natyaveda, the fifth Veda that would be accessible to all the four castes (1:12). It claims that the text imbibes in itself the articulated- spoken word (paatya) from Rig-Veda ; the ritual and the body-language (abhinaya) from Yajur Veda; musical sound , the sung-note, from Sama Veda; and Sattvika (understanding of the relation between mind and body-expressions) – for conveying various bhavas through expressions exuding grace and charm – from Atharva Veda . (Natya-Shastra – 1:17-19)

jagrāha pāṭhyamṛgvedātsāmabhyo gītameva ca । yajurvedādabhinayān rasānātharvaṇādapi ॥ 17॥

vedopavedaiḥ sambaddho nāṭyavedo mahātmanā । evaṃ bhagavatā sṛṣṭo brahmaṇā sarvavedinā ॥ 18॥

utpādya nāṭyavedaṃ tu brahmovāca sureśvaram । itihāso mayā sṛṣṭaḥ sa sureṣu niyujyatām ॥ 19॥

*. The text is permeated with the Vedic symbolism and the imagery. The theatrical production is compared to yajna; with the stage being the vedika, the altar. The dramatic spectacle, just as yajna, is said to have a moral and ethical purpose.

The text might have, therefore, arisen at a time when the Vedas were not a remote theoretical fountain head, but a living-immediate experience.

*. The text strongly recommends that puja, worship, be offered to the stage before commencement of the show. It however recognizes puja as distinct from yajna. There is, however, no reference to “image” worship.

*. The gods revered and worshiped in the text are the Vedic gods; and not the gods celebrated in the puranas. For instance, Natya-Shastra begins with a salutation to Pitamaha (Brahma) and Maheshwara. There is no specific reference to Shiva. There is no mention of Nataraja even while discussing karanas and angaharas. Ganesha and the avataras of Vishnu are conspicuously absent. There are no references either to Krishna or to the celestial raasa dance.

*.The gifts showered by the gods on successful performance of the play are similar to the gifts received by the performer at the conclusion of the yajna.

“Indra (Sakra) gave his auspicious banner (dhwaja) , then Brahma a kutilaka (a crooked stick) and Varuna a golden pitcher (bhringara) , Surya an umbrella, Shiva success (siddhi) and Vayu a fan , Vishnu a throne (simhasana), Kubera a crown and Saraswathi –visibility and audibility.” (Natya-Shastra-1.60-61)

brahmā kuṭilakaṃ caiva bhṛṅgāraṃ varuṇaḥ śubham । sūryaśchatraṃ śivassiddhiṃ vāyurvyajanameva ca ॥ 60॥

viṣṇuḥ siṃhāsanaṃ caiva kubero mukuṭaṃ tathā । śrāvyatvaṃ prekṣaṇīyasya dadau devī sarasvatī ॥ 61॥

*. It therefore appears; during the time Natya-Shastra was compiled the prominent gods were the Vedic gods such as Indra, Varuna and Vayu; and not the gods of the Puranas that came in to prominence centuries later.

*.The mention of the Buddhist bhiksus and Jain samanas indicate that Natya-Shastra was post –Buddha and Mahavira.

*. Natya-Shastra employs a form of Prakrit, which predates the great poet Ashvaghosha’s play (first century).

For these reasons, the scholars generally agree that Natya-Shastra might have been composed sometime between second century BCE and second century AD, but not later.

7. 1.The questions whether or not the Natya-Shastra was compiled in a particular year by a particular person are not very important. Whatever are the answers to those questions, the importance of the work would not be diminished nor its wisdom distracted. What is of great importance is that Natya-Shastra has provided a sustainable foundation and framework for development of theory and practice of arts in India. Just as Panini standardized the classical form of Sanskrit, Bharata standardized the classical form of drama. He gave it status and dignity; a form and an objective; a vision and finally a technique.

7.2. Bharata ensured that drama and dramatic performance is first a work of art before it is literature – drsya kavya a form of literature that could be seen and heard.

7.3. His brilliant intuition and intellect has inspired generations of artists over several centuries. It is immaterial whether or not Bharata was an individual or when he lived.

8.1. The Natyashastra consists of 36 chapters. The outer and spatial aspects, such as the stage, the theater building etc. are discussed in Chapters 1–5. Chapters 6–7 discuss the theory of rasa, i.e. the crucial question as to how to evoke a mood, while Chapters 8–13 focus on the physical acting technique. The verbal aspect, such as speech and sound, is dealt with in Chapters 14–19, while Chapters 20–21 discuss the types and structure of drama. The outer aspects of acting, such as the costume and the make-up types, are dealt with in Chapters 22–26. More general aspects are touched upon in several chapters, while Chapters 28–33 focus on music. Aspects of the theater troupe and the distribution of roles are then discussed, after which the focus returns to the very beginning, i.e. to the question of the divine origin of the art of the theater. ( Kapila Vatsyayan : Bharata, The Natyashastra, New Delhi, 1996).

*

It could be said that the Natya-shastra is broadly modeled into four sections, based on Abhinaya or modes of conveying theatrical expressions which bring pleasure, pure delight (Rasa) to the cultured spectators (sahrudaya). Such Abhinaya-s are: Sattvika (conveyed through expressions which delight the mind); Angika (natural and appropriate movements of body, limbs and face); Vachika (delivery through speech and songs); and Aharya (costume, decoration, make-up and such others to heighten the beauty or the effectiveness of the dramatic presentation).

The author of the Natya-shastra seems to have assigned greater importance to Sattvika elements, the expressions of which are conveyed through the aid of movements, gestures (Angika) and speech (Vachika).

Angika relates to the movement of the parts of the body, which is classified into three major parts – the Anga, Patyanga and Upānga . Angika relates to how the emotion, thoughts and the thing are to be expressed or represented through the movement of the Anga (limbs), which include facial expressions. There are two types of basic Abhinayas as Pada-artha abhinaya (when the artist delineates each word of the lyrics with gestures and expressions); and, Vākyā-rtha abhinaya (where the dancer acts out an entire stanza or sentence). Āngika abhinaya uses the total body to express certain meaning. Hasta (hand) Abhinaya is an important aspect of Āngika.

Vachika abhinaya is the expression through speech. It is done with the help of speech and songs. Bharatha deals in detail with the different meters in poetry, strong and weak points of poetic writing and diction. He also talks about Figures of speech (Alamkara) . Nātyasāstra says that words spoken during Nātya should be full of suggested meaning.

Nāṭyasāstra in its 15th -19th Chapters explains vocal movements. It recognizes the importance of expressions through the medium of voice in the presentation of a Drama; they are its basic features; and, form the very substance of the Dramas. Other movements depend on and follow vocal movements.

Bharatha mentions three kinds of voice expressions-: 1) Mandra; 2) Madhya; and, 3) Tāra.

The sound which origins from the heart , having a quality of bass is called Mandra. The sound originating from the throat, in the normal manner is named Madhya. And, Tāra is the high-pitched sound originating from the head.

According to Nāṭyasāstra, the vācikā-bhinayas divided into seven parts .

-

- 1) Prakāsa-bhāsana– loud and clear speech;

- 2) Ātmagata-bhāsaṇa– talking to self;

- 3) Apavārita-bhāsaṇa (asides);

- 4) Janāntika-bhāsaṇa (audiable to others);

- 5) Sāmūhika-bhāsana – group expressions (simultaneous talk);

- 6) Ekala- bhāsana – single expressions (monologue);

- 7) Ākāsa- bhāsana – talking to the sky (talking to no one in particular); and,

- 8) Rahasyakathana – stage-whisper

8.2. The Sattvika aspects are dealt in Chapters 6 and 7; followed by Angika in Chapters 8 to 13; and, Vachika in Chapters 14 to 20. The Aharya which deals with costume, scenic presentation, movement on the stage along with music from the wings etc follow in the later Chapters.

The 23rd Chapter of Nāṭyasāstra details the Āhārya abhinaya, which covers several aspects , such as the make-up (Angaracanā ); costumes and ornaments (Alankāra prasādhana); use of specific colors; hair styles; as well as costumes suitable for particular characters. The Aharya also covers the background sceneries (Pusta), stage props and décor.

The four-fold core Chapters are supported by information and descriptions about the origin and greatness of the theatrics; different forms of the stage and the norms for construction; qualifications and desirable modes of behavior of the actors; and the rituals and prayers before and after the play etc.

Thus, the core of the theatrical art and science is dealt in 29 Chapters – from 6 to 34.

9.1. A question that is often asked is: why were the ancient Indian scholars and seers reluctant to disclose, in their works, details of themselves and of their times? Did they lack a sense of history?

There is, of course, an array of explanations, in answer to that.

But, I think it had a lot to do with the way the ancients defined their relation to a school of thought, and the position, they thought, their text occupied in the tradition of that school. They always viewed themselves as a part of an ongoing tradition – parampara. Invariably, even the best known of our thinkers (say, the Buddha, Badarayana or Sri Sankara) did not claim that they propounded an absolutely new idea that was totally unknown hitherto. They always said, they were interpreting or elucidating the truth in the light of eternal pristine principles. They did not lay claim to novelty or uniqueness. They placed their work in relation to the larger and broader river or stream of the tradition. Within that tradition, individual styles, innovative ideas or enterprising leaps of thought were surely discerned; but, they were always placed and viewed in context of the overall ongoing tradition.

9.2. As regards Natya-Shastra, as Kapila Vatsyayan summed up beautifully:

“ it was analogous to the Gomukh demarcating the glaciers above and the rivers which flow with streams of the Alakananda and the Mandakini , the Bhagirathi and others with their manifold confluences and some divergences , but all of which we recognize as the Ganga. The analogy of streams, confluences (prayaga) and the continuous flowing and yet unchanging nature of the river is the closest approximation in which the parampara of the Natya-Shastra, the text and dramatics of inflow confluences, outflow and ultimate inflows in to the ocean, can be explained.”

9.3. The individual biological identity in terms of the physical events of the birth and the personal life of the author did not, therefore, seem to be a psychical concern. Individual effort and contribution in furthering a school of thought was, no doubt, important; but, it was viewed as an integral part of the dynamics of the flow and course of the river called parampara, characterized with its nature of continuity and change.

The attitude signified being alive to a sense of tradition rather than lack of a sense of history.

1 0. Why was the text called a Shastra?

The term Shastra does not always carry connotations of ritual or religion. Nor does it always mean classical, as in shastriya sangeeth.

The Sanskrit- English dictionary of Sir Monier-Williams describes the term as an order, a command, a rule, teaching, and instruction manual relating to religious precepts. But, Shastra, in fact, means much more than that.

10.1.In the Indian context , Shastra is a very extensive term that takes in almost all human activities – right from cooking to horse and elephant breeding; love making to social conduct; economics to waging wars; justice system to thievery ; and of course all the arts- from archery to poetry. There is a Shastra – a way of doing and rationalizing — for almost everything. A Shastra binds together the theory that provides a framework for rationalizing the practice; and the practice that illustrates the theory. Shastra is, at once, the theory of practice and practice of a theory- enriching each other.

10.2. The author of Natya-Shastra prefers to call it a prayoga Shastra – a framework of principles of praxis or practice. Bharata makes a significant opening statement: “I am creating a theory and text of performance; of practice and experimentation” . He also underlines the fact that the efficacy of its formulation lies in practice (prayoga) – vibhāvayati yasmācca nānārthān hi prayogataḥ ।NS.8.7

10.3. There is a certain flexibility built in to the structure of the text. It provides for varied interpretations and readings. The author himself encourages innovations and experimentation in production and presentation of plays. He even permits modification of his injunctions; and states the rules “can be changed according to the needs of time (kaala) and place (desha)” . The text accordingly makes room for fluidity of interpretation and multiple ways of understanding it. The intellectual freedom that Bharata provided to his readers/listeners ensured both continuity and change in Indian arts over the centuries.

11. 1.Natya-Shastra,throughout, talks in terms of the metaphor of the seed (bija) and the tree. It talks of the organic inter-relatedness of the parts and the whole; each branch of the text being distinct and yet inspired by the unitary source. Introduction of the core theme is the seed (bija) and its outer manifestation is like a drop of liquid or a point (bindu) that spreads and enlarges (vistara) to fill the structured space. That denotes both the process and the structure.

11.2. Bharata also explains the relationship between the structure of the drama, its plot, bhava and rasa through the imagery of a tree. The text grows like a tree and gives out shoots like the proverbial Asvattha tree.” Just as a tree grows from a seed and flowers and fruits… So the emotional experiences (rasa) are the source (root) of all the modes of expressions (bhava). The Bhavas, in turn, are transformed to rasa.”(Natya-Shastra: 6-38)

yathā bījād bhaved vṛkṣo vṛkṣāt puṣpaṃ phalaṃ yathā । tathā mūlaṃ rasāḥ sarve tebhyo bhāvā vyavasthitāḥ ॥ NS.6.38॥

11.3. This idea of multiplicity springing out of a unity is derived from the worldview nourished by the ancient Indians. Bhartrhari (Vakyapadiya), for instance, observes that diversity essentially pre-supposes an underlying unity (abedha-purvaka hi bhedah). In other words, he says, where there is difference or division there must be a fundamental identity underneath it ; else, each cannot relate to the other; and , each object in the world would be independent of , or unconnected to every other thing in existence.

Such holistic view treats the world as a living organism, a whole with each part interrelated and inter dependent. The expanding universe is viewed as a process of sprouting from the primordial source (bija), blooming, decaying and withering away, at some time; but only to revive and burst forth with renewed vigor. The seed (Bija) is the source / origin of the tree; and, Bija is also its end product. The relationship between the universe and the human; between nature and man, too, has to be understood within the cyclical framework of the Bija– and – the tree concept.

Bharata seems to suggest that theater is an organism, just as life is an organism that re-invents itself.

12 . Let me end this in the way Bharata concluded his Natya-Shastra:

“He who hears the reading of this Shastra , which is auspicious, sportful, originating from the mouth of Brahman , very holy , pure good, destructive of sins; and he who puts in to practice and witnesses carefully the performance of drama will attain the same blessed goal which masters of Vedic knowledge and performers of yajna – attain.” (Natya-Shastra-37:26-28 )

ya idaṃ śruṇuyān nityaṃ proktaṃ cedaṃ svayambhuvā । kuryāt prayogaṃ yaścaivamathavā’dhītavān naraḥ ॥ 26 ॥

yā gatirvedaviduṣāṃ yā gatiryajñakāriṇām । yā gatirdānaśīlānāṃ tāṃ gatiṃ prāpnuyāddhi saḥ ॥ 27 ॥

dānadharmeṣu sarveṣu kīrtyate tu mahat phalam । prekṣaṇīyapradānaṃ hi sarvadāneṣu śasyate ॥ 28 ॥

[ http://sanskritdocuments.org/doc_z_misc_major_works/natya37.html?lang=iast]

Please also read Abhinavabharati – an interpretation of Bharata’s Natya-Shastra

Sources and references

Bharatamuniya Natya-Shastra by prof.SKR Rao

Bharata: The Natya-Shastra by Kapila Vatsyayan

Introduction to Bharata’s Natya-Shastra by Adya Rangacharya

An introduction to natya shastra – gesture in aesthetic arts by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D.

Translation of the Natya-Shastra verses from the Natya-Shastra by Man Mohan Ghosh

http://sanskritdocuments.org/doc_z_misc_major_works/natya36.html?lang=iast

Images are from Internet

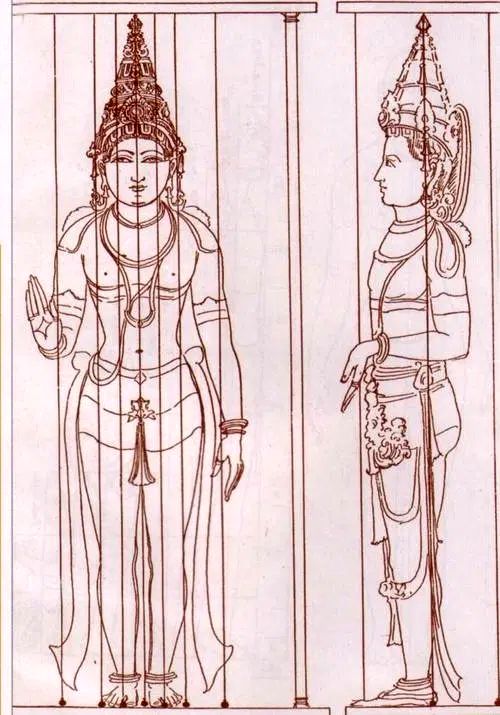

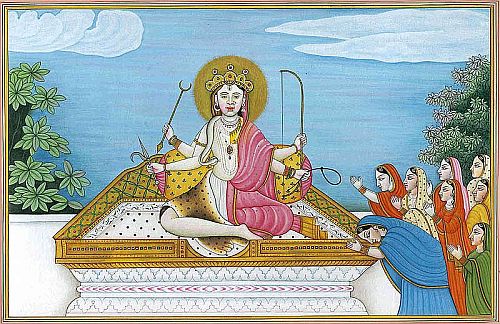

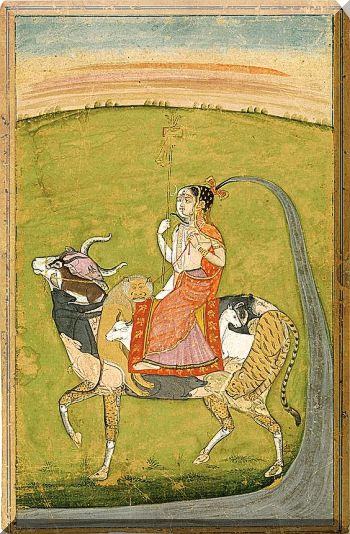

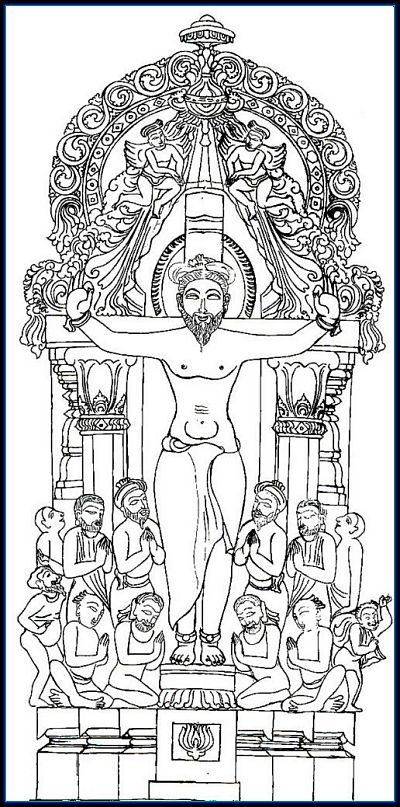

(Devi as Ardha-purusha)

(Devi as Ardha-purusha)

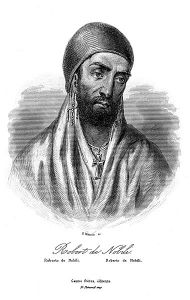

Having that in view, he tried entering in to the core of the orthodox society. He distanced himself from the image the people had about the uncouth Portuguese. He presentedhimself as a Kshatriya, a Raja_sanyasi from the country of Roma. People of Madurai did take notice of him but could not appreciate the strange amalgam of a foreigner, a Kshtriya and a sanyasi spreading the message of an alien god. He remained at best an object of curiosity and was not taken seriously.

Having that in view, he tried entering in to the core of the orthodox society. He distanced himself from the image the people had about the uncouth Portuguese. He presentedhimself as a Kshatriya, a Raja_sanyasi from the country of Roma. People of Madurai did take notice of him but could not appreciate the strange amalgam of a foreigner, a Kshtriya and a sanyasi spreading the message of an alien god. He remained at best an object of curiosity and was not taken seriously.

rto de Nobili decided to follow the steps of the fellow Jesuit, Ricci. Like Ricci, he took great care not to impose his Western views or culture on the local population. Instead, he tried becoming one among them by adopting the role, customs and attitude of a sanyasi.

rto de Nobili decided to follow the steps of the fellow Jesuit, Ricci. Like Ricci, he took great care not to impose his Western views or culture on the local population. Instead, he tried becoming one among them by adopting the role, customs and attitude of a sanyasi.

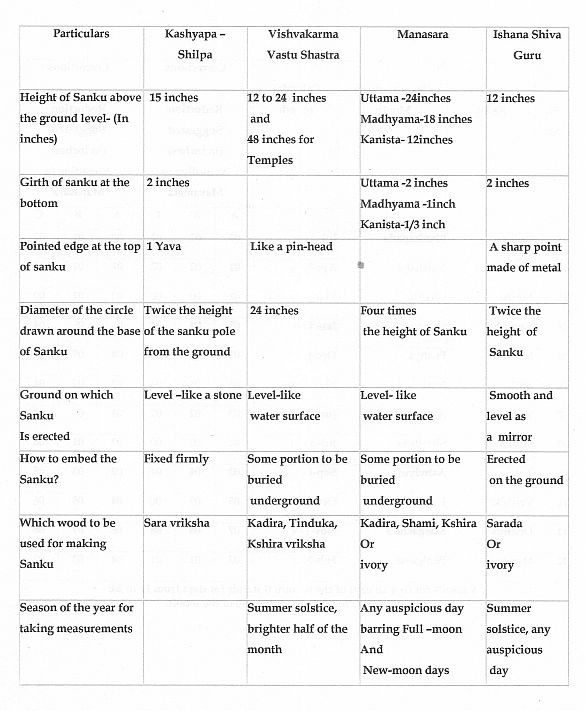

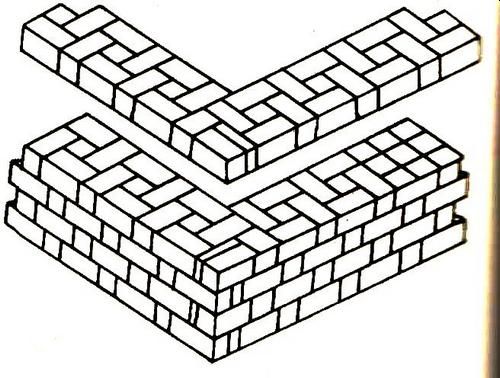

standing perpendicular to the ground. They suggest that in case the height of the Sanku is 12 inches, a circle should be described with the base of Sanku as the centre and with a radius of 16 inches. This in effect forms a right angled triangle , with the radius as the base of the triangle (16 inches), the Sanku as its height (12 inches); and the string(rajju) connecting the top of the Sanku to the point of intersection of the base of the triangle with the circle forming the hypotenuse. If the sanku stands absolutely perpendicular then the string (hypotenuse) should measure exactly 20 inches. This exercise was based on the theory of Brahmagupta (6thcentury AD) otherwise known as the Pythagorean Theorem.

standing perpendicular to the ground. They suggest that in case the height of the Sanku is 12 inches, a circle should be described with the base of Sanku as the centre and with a radius of 16 inches. This in effect forms a right angled triangle , with the radius as the base of the triangle (16 inches), the Sanku as its height (12 inches); and the string(rajju) connecting the top of the Sanku to the point of intersection of the base of the triangle with the circle forming the hypotenuse. If the sanku stands absolutely perpendicular then the string (hypotenuse) should measure exactly 20 inches. This exercise was based on the theory of Brahmagupta (6thcentury AD) otherwise known as the Pythagorean Theorem.

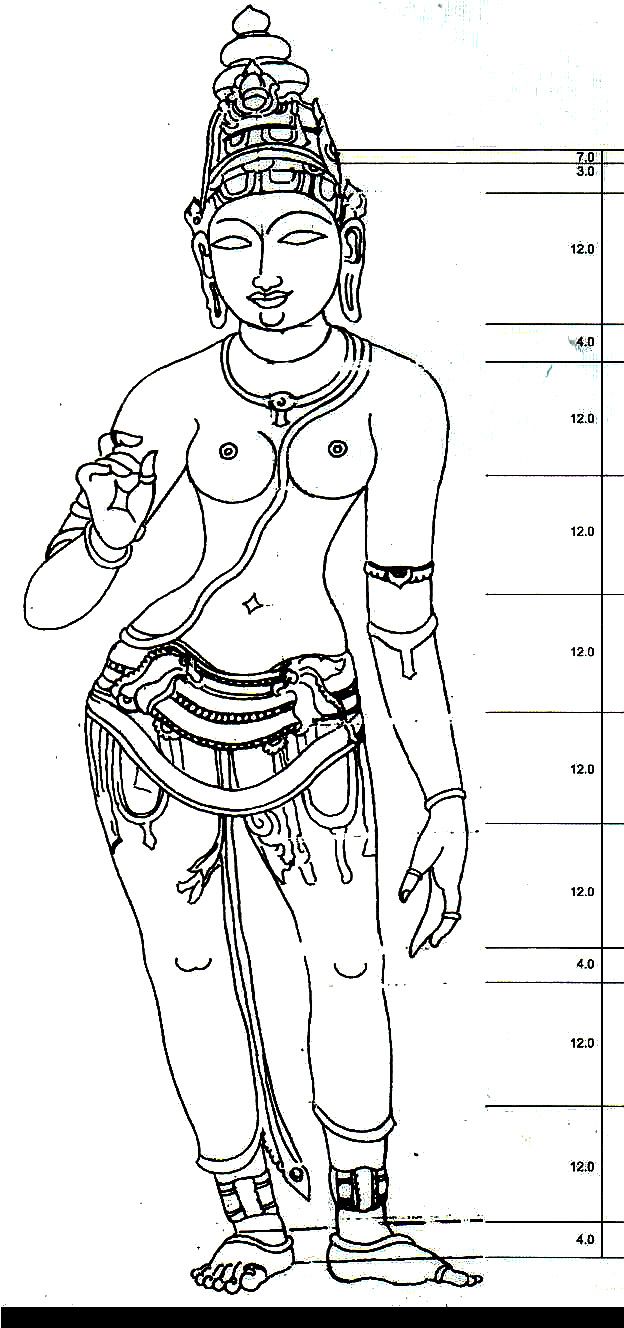

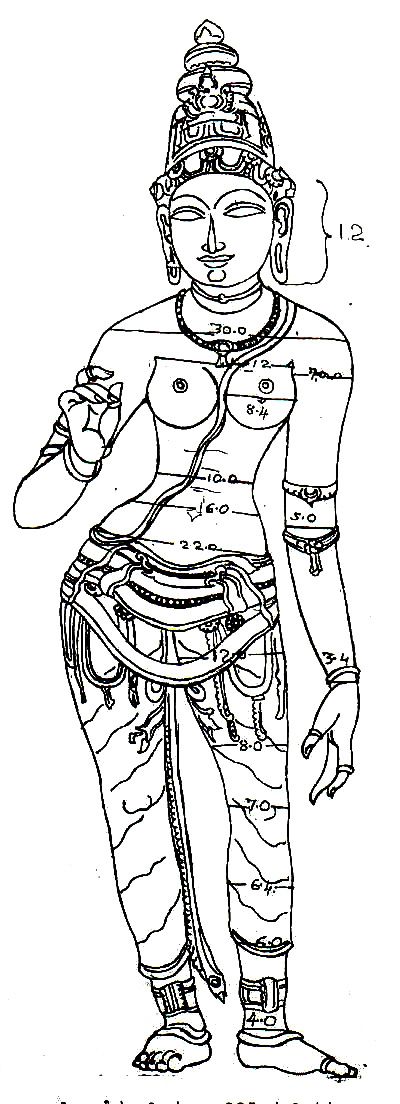

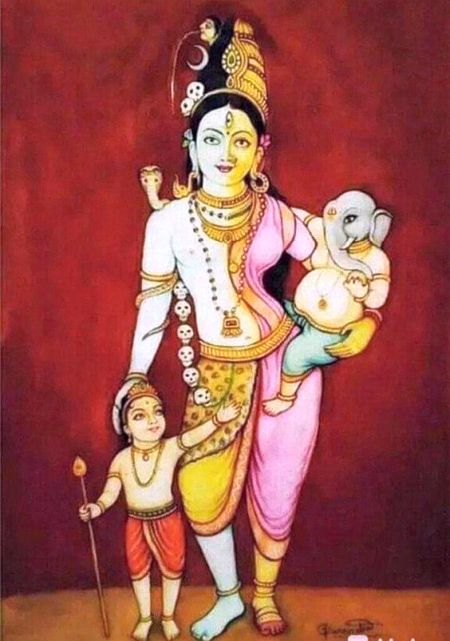

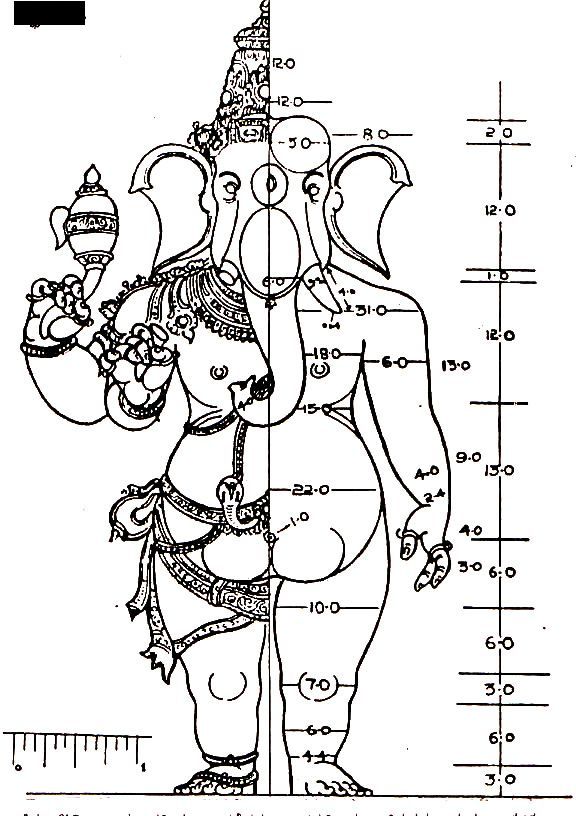

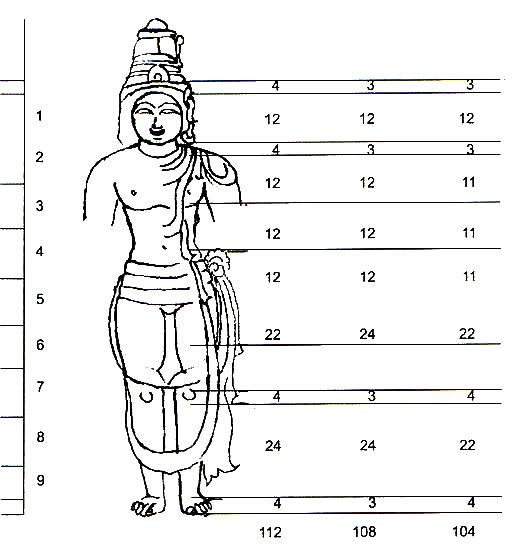

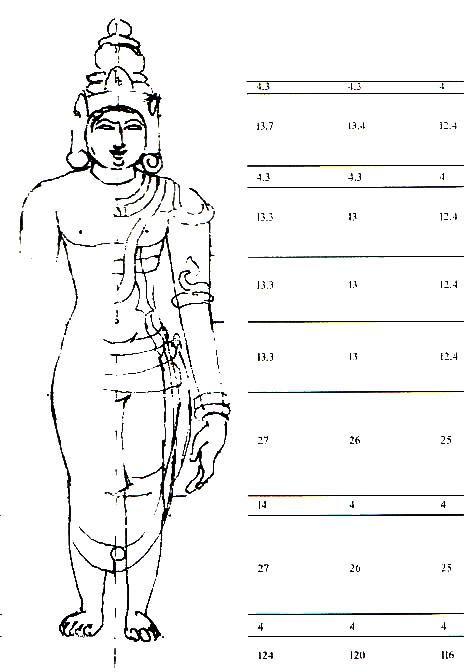

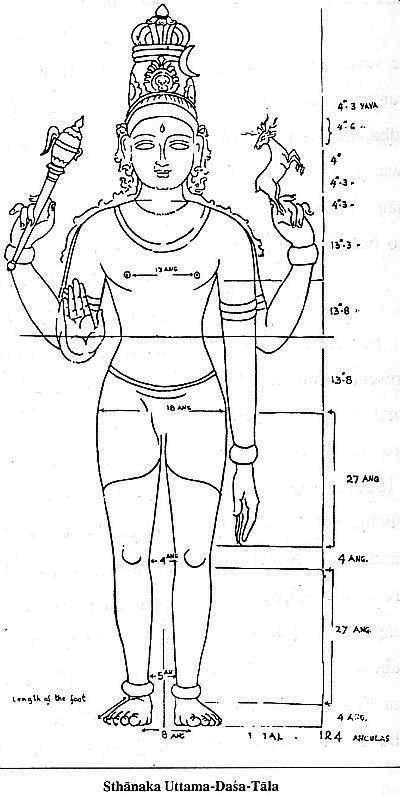

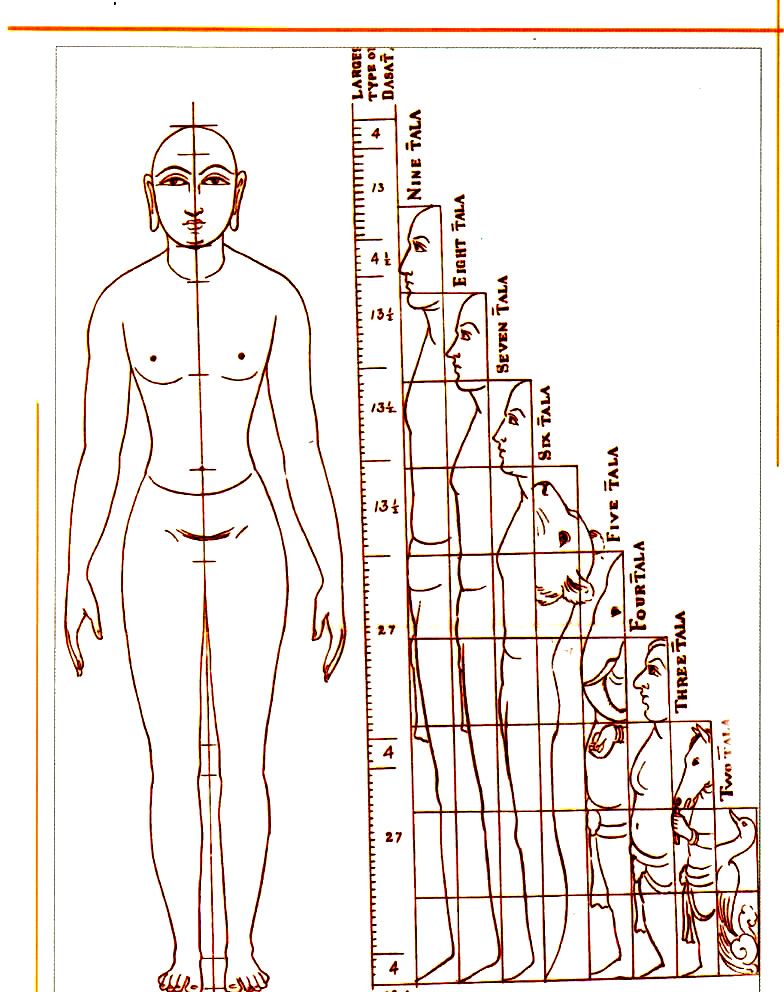

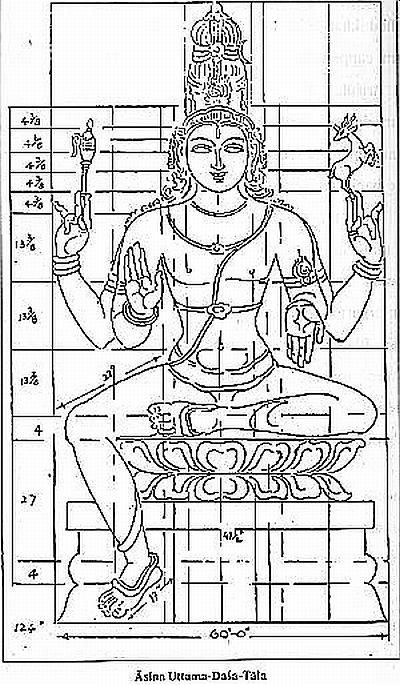

Dr. Stella Kramrisch explains in her Hindu Temple: the rules are that the proportions of the trunk are the same in all the four types. The distance from the root of the neck to the genitals is divided in to three equal parts, in each case: neck-heart; heart-navel; and navel-genitals. The length of the thigh and that of the leg are twice as long as each of the three earlier mentioned sections. Further, the knee and the foot are of equal height. The actual lengths of these lengths might vary, but their proportions are maintained. As regards the size of the face, it is 12 angulas (except in the case of dasatala).

Dr. Stella Kramrisch explains in her Hindu Temple: the rules are that the proportions of the trunk are the same in all the four types. The distance from the root of the neck to the genitals is divided in to three equal parts, in each case: neck-heart; heart-navel; and navel-genitals. The length of the thigh and that of the leg are twice as long as each of the three earlier mentioned sections. Further, the knee and the foot are of equal height. The actual lengths of these lengths might vary, but their proportions are maintained. As regards the size of the face, it is 12 angulas (except in the case of dasatala).