From: Venetiaansell

Dear Dr Rao, I read your post on sharad rtu with great interest. I am a student of Sanskrit and currently doing some research on the description of each rtu and in particular the flowers associated with each and would be interested to know more. Can you recommend any good books or articles about rtuvarnana in Sanskrit literature? I look forward to hearing from you. Best, Venetia

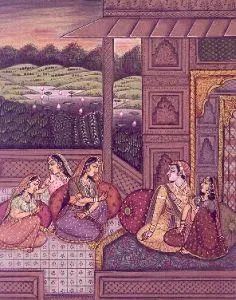

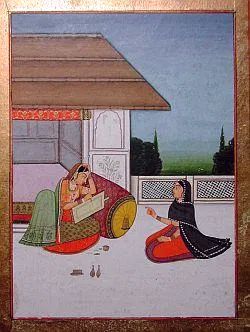

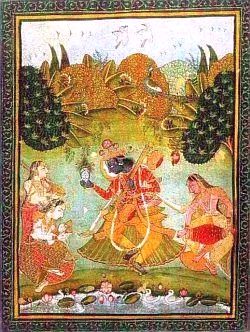

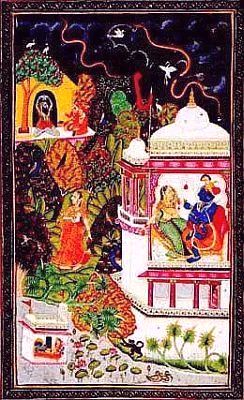

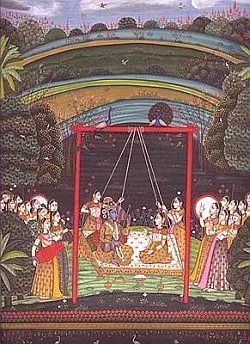

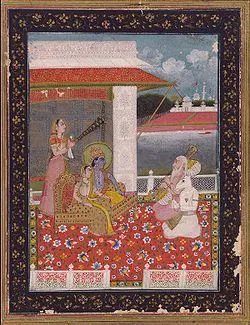

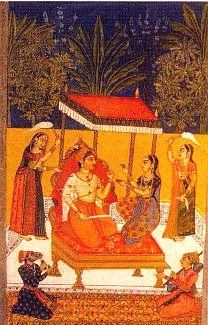

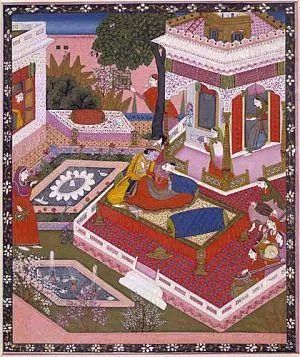

Creation of the Artist Kailash Raj

A. Ritu- varnana in Sanskrit Literature

1.1. Dear Venetiaansell , Greetings. The phenomena of the seasons, day and night, birds and beasts and flowers, are often employed in Sanskrit poetry to frame human emotions, or are personified as counterparts of the human subjects of the poet. And, throughout the literature, a deep love of nature is implicit, especially in the poems of Kalidasa; who, for this reason , among others, is regarded very highly.

Kalidasa’s Meghadutam, a work of little over 100 verses, has always been one of the most popular of Sanskrit poems. Its theme has been imitated in one form or another by several later poets both in Sanskrit and in the vernaculars. As compared to similar other Indian poems of that nature, this work has unity and balance; and, gives a sense of wholeness that is rarely found elsewhere. In its small compass, Kalidasa has crowded so many lovely images and word-pictures that the poem seems to contain the quintessence of the whole of Indian natural scenery.

As regards the ritu- varnana in its proper natural sequence, the most renowned, of course, is again that by the Great Kalidasa in his various poetic works, and especially in the Ritu-samharam, the melody of the seasons or the garland of the seasons, running into six cantos describing the six seasons of the year; and how with each change in the season, the mood and behaviour of a young lover too would alter. In his other work, the Meghdootam, the intensity of the lovelorn Yaksha is far deeper. However, he weaves his yearning around the clouds; and thus, the description is confined to the rainy season.

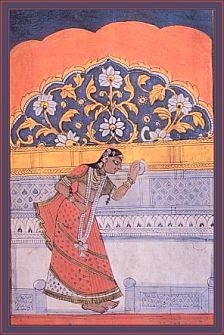

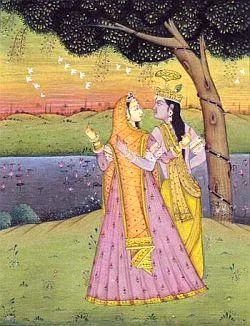

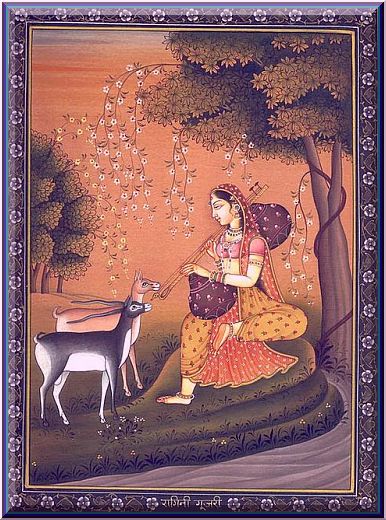

In Kalidasa’s romantic poetry; graceful sensuality, colours and the music of love resonate with the world of blossoms and birds. The urges and pains of his nayaka and nayika are shared by the deer, birds, trees and the sky. It is a world where trees long for the touch of a lovely woman as much as a man longs for her embrace. There is an unspoken bond between the song of the peacock and the lament of the separated lover. The messages of love are conveyed through clouds; and , the changing seasons mirror the changing colours of love.

Kalidasa’s nayika adorns herself with blossoms and sprouts of the forest as ornaments ; and decorates her lotus-like feet with the red dye from the forest flowers and herbs . She is decked in various fragrant flowers; a padma in her hands; kunda blossoms in her hair; the pollen of lodhra flowers on her face; the fresh kurbaka flowers in her braid ; the lovely sirisha flowers on her ears (Karna-avatamsam) ; and, the nipa flowers that bloom in the parting of her hair .

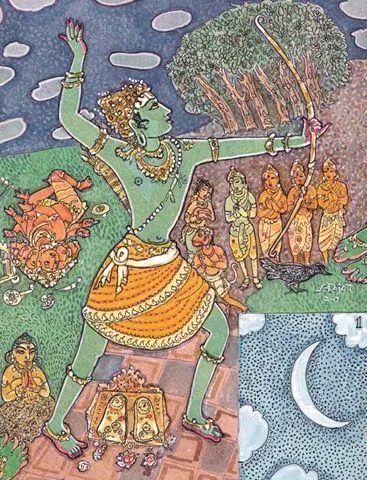

The nocturnal path of the lovelorn abhisarika nayika is traced at dawn by the mandara flowers that have fallen from her hair and the golden lotuses that have slipped off her ears (Ritusamharam 2.11-12). Kalidasa’s nayika is not a mere mortal but a yakshi, the very life and spirit of a tree; and the trees mirror her exuberant ardour.’

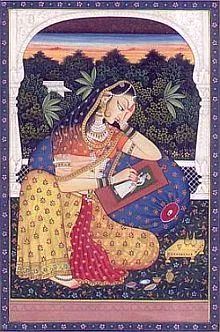

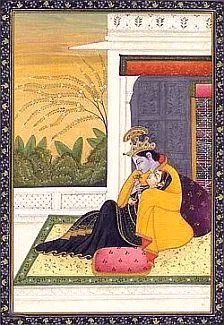

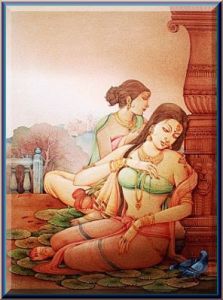

Kalidasa’s virahini-nayika of the Meghadutam, separated from her lover; like a lotus deprived of the sun ; like a solitary Chakravaka bird isolated from her mate ; and, crestfallen like a lotus withered by winter, is a chaste lovelorn woman, pining for her lover.

She sits with her face resting in the cup of her palms, her locks covering her face as clouds cover the moon. She spends her time alone in her bed with her ornaments cast off; counting the days of her separation by placing flowers on the threshold ; by painting the likeness of her beloved , singing songs reminiscent of her lover and talking to the Sarika bird (Meghadutam 2.20-2.33).

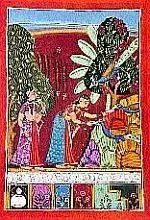

The Virahini Nayika sends messages to Krishna through her maid .

There is a certain dignity in her poignancy; a grace in her sorrow. The colors of her pathos resemble that of the wilted flowers and the movements of her eyes and limbs speak of her pain even when her words do not.

If Kalidasa’s Meghadutam is the epitome of the virahini in early Sanskrit poetry, his Ritusamharam is the poetic testimony of how intimately the loves, pathos and lives of the human are tied with the colours and sounds of the seasons. Of all the seasons’, vasanta or spring is especially important to those in love, for the blossoms of spring are like the arrows of Kama. Red is the colour of the spring season everywhere and it is when:

The mango tree bent with clusters of red sprouts kindle ardent desire in women’s hearts

The ashoka tree that bears blossoms red like coral makes the hearts of women sorrowful

The atimukta creepers whose blossoms are sucked by intoxicated bees excite the lovers

The kurabaka tree whose blossoms are lovely as the faces of women pain the hearts of sensitive men

The kimsuka grove bent with blossoms, waved by winds, appears like a bride with red garments. — Ritusamhara (15–20)

sugandhikālāgurudhūpitāni dhatte janaḥ kāmamadālasāṅgaḥ // KalRs_6.15 //

puṃskokilaś cūtarasāsavena mattaḥ priyāṃ cumbati rāgahṛṣṭaḥ /

kūjaddvirephāpyayam ambujasthaḥ priyaṃ priyāyāḥ prakaroti cāṭu // KalRs_6.16 //

tāmrapravālastabakāvanamrāś cūtadrumāḥ puṣpitacāruśākhāḥ /

kurvanti kāmaṃ pavanāvadhūtāḥ paryutsukaṃ mānasamaṅganānām // KalRs_6.17 //

āmūlato vidrumarāgatāmraṃ sapallavāḥ puṣpacayaṃ dadhānāḥ /

kurvantyaśokā hṛdayaṃ saśokaṃ nirīkṣyamāṇā navayauvanānām // KalRs_6.18 //

mattadvirephaparicumbitacārupuṣpā mandānilākulitanamramṛdupravālāḥ /

kurvanti kāmimanasāṃ sahasotsukatvaṃ bālātimuktalatikāḥ samavekṣyamāṇāḥ // KalRs_6.19 //

kāntāmukhadyutijuṣāmacirodgatānāṃ śobhāṃ parāṃ kurabakadrumamañjarīṇām /

dṛṣṭvā priye sahṛdayasya bhavenna kasya kandarpabāṇapatanavyathitaṃ hi cetaḥ // KalRs_6.20 //

Vasanta is also the season when cuckoos sing in indistinct notes; the bees hum intoxicating sweet sounds; and, the travelers separated from their lovers lament. Kama the god of love who wages a war, as it were, on those in love, fashions his arrows from the mango blossom; his bow from the kimsuka flower; the bowstring from a row of bees. His parasol is the moon; and, he wafts the gentle breeze from the Malaya mountain whose bards are the cuckoos (Ritusamharam 28).

1.2. Another poet and playwright , Rajashekhara (Ca.9th century) in his Kavyamimamsha , a treatise on poetry, summarized , for the benefit of the aspiring poets essaying to portray seasons in their works , how the seasons were portrayed in the poetic works prior to his time. In addition, he collated the standards as authorized by the texts. Rajashekhara came up with comprehensive season- descriptions, outlining each season’s basic characteristic features, months-wise divisions, individuality of each month, and the imagery that a poet should preferably employ for representing a season. He also deduced the natural human responses to a given season.

1.3. The great poet Dandin (Ca.6-7th century) renowned for his colorful Sanskrit prose, too, in his Kavyadarsha (‘Mirror of Poetry’) the handbook of classical Sanskrit poetics, mandated that a classic work of poetry (maha-kavya) should essentially include eighteen (ahsta-dasha varnana) types of descriptions including that of the

- city (nagara);

- ocean (saagara);

- mountains (shaila) ;

- seasons (vasantadi ritu);

- the moon;

- the sun rise and sunset (chandra-surya udaya –asthamana);

- parks (udyana);

- strolling in the gardens (vana vihara);

- water-sports (jala krida) ;

- pleasures of wine and love making (madyapana surata);

- wedding (vivaha);

- discussions with the wise (vipralamba) ;

- pangs of separation (viraha);

- birth of sons (putrodaya);

- state-craft (raja-mantra);

- gambling or sending messengers (dyuta);

- wars (yuddha);

- campaigns (jaitra-yatra); and,

- accomplishments of the hero (nayaka abyudaya).

1.4. The description of seasons thus became an integral part of classic poetry . Apart from Kalidasa’s poetry, there are some beautiful heart-warming descriptions of the seasons in the poetic works of other notable poets too; for instance, as in: Bhattikavya by Bhatti; Kiratarjuniya by Bharavi; Shishupala-vadha by Magha; Naishadhacharita by Shriharsha among others.

2.1. The Natya-shashtra too had earlier directed how seasons should be represented in a drama, especially on the stage through an actor’s performance – acts, gestures, facial demeanours and other expressions.

2.2. The Puranas also evinced interest in season-description. The Matsya Purana has a whole chapter dedicated only to the month of spring; while the Samba Purana alludes to different colours of the sun in the six ritus. The Chitra-sutra in the Vishnudharmottarpurana (c.6th century) prescribes certain general rules for the depiction of each of the four seasons.

3.1. According to Chitrasutra of the Vishnudharmottarpurana, the depiction of each of the four seasons could be symbolically represented in the paintings by employing certain idioms of expression, such as:

Summer: languorous men seeking shade under trees, from the harsh summer sun; buffaloes wallowing in the mire of muddy waters; birds hiding under a thick abundance of leaves; and, lions and tigers seeking cool caves to retire in.

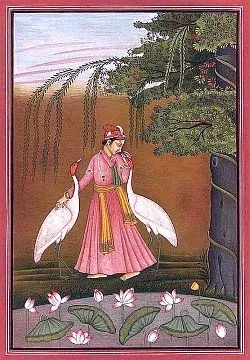

Rain: An overcast sky, with heavy rain filled clouds weighed down with their aquatic excess; flashes of lightning and the beautiful rainbow; animals like tigers and lions taking shelter in caves; and, sarus (cranes) birds flying in a row.

Autumn: Trees laden with ripe fruit; the entire expanse of the earth filled with ripened corn ready for harvest; lakes filled with beautiful aquatic birds like geese; the pleasant sight of blooming and blossoming lotus flowers; and, the moon brightening up the sky with a milky white lustre.

Winter: the earth wet with dew; the sky filled with fog; men shivering from the cold, but crows and elephants seem euphoric.

[A collection of learned essays by the great scholar Dr. V Raghavan ‘Rtu in Sanskrit Literature’ (1972) published by Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri Kendriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha , Delhi, comprehensively deals with all aspects of Rtu varnana in Sanskrit texts including Rig Veda and , epics and puranas.]

B. the Barahmasa tradition

4.1. With the decline of classic Sanskrit poetry, the ritu-varnana found abundant expression in the Barahmasa tradition. Barahmasa meaning twelve months are based on the lunar calendar comprising months of Chaitra, Vaishakha, Jyestha, Ashadha, Shravana, Bhadrapada, Ashvina, Karttika, Agrahayana, Paushya, Magha and Phalguna. Each two of them are respectively the ritus or seasons of Vasanta, Grishma, Varsha, Sharada, Hemanta and Shishira.

4.2. The glory and characteristic beauty of each season came to be celebrated in a specialized form of poetry, music and art (paintings) as Barahmasa, describing the splendour, aura and magic of nature as it emerges with the change of each season. The expressions of the ritu– theme were rendered highly eloquent with the emotive songs and music; as also by the exquisite miniature paintings depicting the glory and poignant character of each season woven into stories of tender love, separation and reunion.

4.3. The essential theme of the Barahmasa is the passionate yearning of lovelorn hearts, the pangs of separation that each change of season stimulates. Each month bringing a special message to the beloved, every season a special reminder of the joys of love and longing. The nature participates in the world of human emotions and mirrors the lovers’ or singer’s experience of tenderness and pain of love.

4.4. The transformations in nature such as the gentle unfolding of a bud’s petals; or melting of a winter night into dew-drops; or the dark dreadful clouds rending with their roar the sky and the earth and frightening the lovely nayika into the arms of her beloved Nayaka and bursting forth into torrential rains – all become symbolic expressions of the seasons and the state of love of the ardent lovers. The Barahmasa depictions of poetry, music and painting, bind the two confronting worlds, the worlds of man and of nature into one thread.

Barahmasa Poetry

5.1. The Barahmasa Poets over the centuries have used the imagery of the Ritu Varnana or changing seasons to depict different facets of human emotions and moods, varying states of romantic love as they respond and change in accordance with seasons. The songs of the seasons resonate with the heart of the lover and the beloved. Nature as always forms the very companion of the yearning lovers.

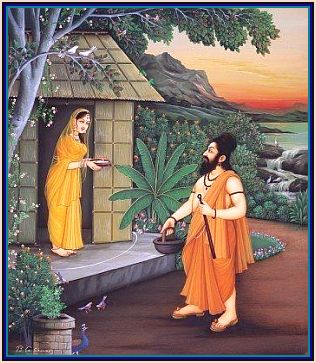

5.2.In expressing her lament and relating it to the colours and moods of the seasons , nayika the heroine likens the throbbing of her heart to the pulsating sap of the trees; the trembling longing within her to the drifting movement of the clouds ; and , the agony of her forlorn state to the pain of lonely birds. She is not alone in her anguish; her piquant cry is heard by the deer, the birds and the blossoms that surround her; they too empathize and share her pain. In Barahmasa poetry there is a strong and sympathetic resonance between the heart of the nayika and the world of nature around her, it is a world that shares her romantic urges and longings.

6.1.Let me add; the theme of Barahmasa occurs not merely in regional representations but in classical poetry too. Let’s, for instance, take the case of Kumarasambhava and the Ramayana. Both are epics; but, while the Kumarasambhava is a chaste classic observing all the mandated norms of poetics and other conventions,the Ramayana represents an amalgam of various folk traditions. In Ramayana, the poet attempts exploring the turmoil in the lovelorn heart of Rama the prince of Ayodhya in exile ,after separation from his beloved Sita , by placing his distress in contrast to the glowing beauty of the season; and picturing how it affects Rama.

The poetry here truly transforms into a viraha song. Rama describes to his brother Lakshmana the sublime beauty of nature that surrounds them; and gives vent to his grief of separation aggravated by the beauty that envelops him. Rama narrates the onset of monsoon in a rather intuitional manner describing the gathering of clouds ; and how they remind him of his brother Bharata and his friend Sugriva are with their wives and in their kingdoms while he is lonely and sad deprived of both.

Thus the vein of ritu-varnana in the Ramayana is closer to the Barahmasa convention. In contrast, the descriptions of nature in Kumarasambhava, in the context of Parvathi’s penance, lack such subjective responses.

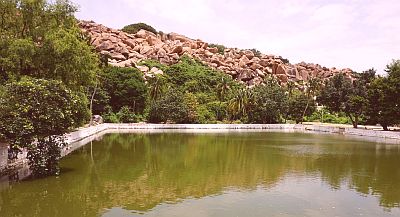

Oh! Soumitri, Pampa Lake is magnificent , glowing with her emerald green like waters (vaiduurya vimala udaka ); adorned with fully bloomed lotuses (phulla padma utpalavatī); surrounded by many trees , Pampa looks truly delightful (śobhate pampā).

saumitre śobhate pampā vaidūrya vimala udakā | phulla padma utpalavatī śobhitā vividhaiḥ drumaiḥ || 4-1-3||

This auspicious Pampa is pleasant with its delightful forests overspread with many diverse flowers, cool waters, though I am sad

śokārtasya api me pampā śobhate citra kānanā | vyavakīrṇā bahu vidhaiḥ puṣpaiḥ śītodakā śivā || 4-1-6||

The green pasture lands have turned into colorful pastures covered with variety of laden trees… and with flower-fall covering it like shining flowery carpet of varied colors of red, blue , yellow etc.,

adhikam pravibhāti etat nīla pītam tu śādvalam | drumāṇām vividhaiḥ puṣpaiḥ paristomaiḥ iva arpitam || 4-1-8||

Breeze coming out from those mountain caves along with the high callings of lusty black cuckoos are making the trees to dance, and the air itself is as though singing as an accompaniment to that dancing

matta kokila sannādaiḥ nartayan iva pādapān | śaila kandara niṣkrāntaḥ pragīta iva ca anilaḥ || 4-1-15 ||

At the shore of this Lake Pampa rejoicing are these birds in groups, and these trees loaded with the mating sounds of birds; and the callings of the male black cuckoos, are inspiring love in me.

asyāḥ kūle pramuditāḥ sanghaśaḥ śakunāstviha | dātyūharati vikrandaiḥ puṃskokila rutaiḥ api | 4-1-28 | svananti pādapāḥ ca ime mām anaṅga pradīpakāḥ |

***

7.1. But, the most eloquent and lovely expressions of Barahmasa are through songs and poetry of viraha, music full of pathos of a young woman Nayika deeply engrossed in love. These representations brimming with the finest imagery and most tender emotions, intense longing, lyrical felicity, rhythmic vibrancy and dramatic conflict of the worlds of man and nature, besides their mystic connotations, form the themes of Barahmasa.

7.2. The Barahmasa poetry has gifted the Indian literature with some of its best lyrics forming the heart-touching love-lore inspired by the folk traditions. Pictorially very rich and emotionally most fervent, the Barahmasa poetry, which subsequently had its transforms in art, is a genre of the Indian countryside. These forms of poetry, music and art are uniquely Indian. Its riches , distinctively Indian, are woven into the cyclic changes in nature and into the lives, loves, and woes of the Indian people in a manner that is not known in other literature and art traditions of the world. They are incomparable.

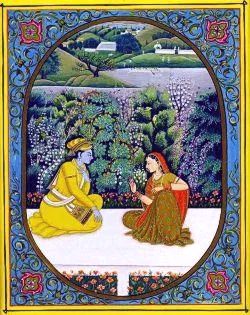

7.3. The Barahmasa themes are mostly entwined with the celestial love of Sri Radha and Krishna. Alberuni (ca.1030) observed that Vasudeva Krishna had a special place in the hearts of the common people who loved to call him by many names. He says; people called out Krishna, out of sheer love, by different names in each of the twelve months; such as: in Margasirsha: Keshava; Paushya: Narayana; Magha: Madhava; Phalguna: Govinda; Chaitra: Vishnu; Vaisakha: Madhusudana; Jyestha: Trivikrama; Ashadha: Vamana; Shravana: Sridhara; Bhadrapada: Hrishikesa; Ashvayuja: Padmanabha; and in Karttika: Damodara.

8.1. The Barahmasa poetry has two basic forms, one, literary, and the other, oral. The oral Barahmasa of the regional dialects later became an important ingredient of the literary poetic tradition. The literary traditions were inspired by the simple songs of the village women pining for the husband or the lover away from her, giving vent to “torments of separation, of estrangement, and feverish waits” ; sung either in the rainy four months from Ashadha to Ashvin or through the twelve months. Literary, Barahmasasare a part of the written literature and are endowed with poetic merit and compositional excellence. Barahmasa, oral or written, as a genre, has five broad types, namely, religious, farming-related, narrative, viraha, and the Barahmasa of chaste woman’s trial.

8.2. Viraha Barahmasa or the seasonal poetry of longing is the most evocative in this genre of romantic poetry. This group of the Barahmasa compositions is inspired by the romantic lore of Sri Radha and Krishna and their beautiful idealized love. The poets charged with Krishna-Radha intoxication recreated the celestial Vrindavana of the Braj country through a class of poetry called ritikavya. Of the many poets in this genre those that stand out are: Bidyapati (1352–1448), Keshavadasa (1555–1617), Bihari (16th century) and Ghanananda (1673–1760).

8.3. Bidyapati the Maithili poet glorifies the sublime love of Sri Radha-Krishna; and charmingly describes the essence of seasons and , in particular , of the lord of the seasons the Basanta the spring : ‘ the rays of the sun in their youthful prime; the golden kesara flower; the fragrant kanchan and Jasmine flower garland; the pollen of flowers floating in the air like a canopy over the patala, tula, kinsuka and clove-vine tendrils; the koil singing its sweetest note ; tribes of honey-bees arrayed their ranks; the water-lily that has just found life with its new leaves ; and the refreshing and shining in Brindaban’.

9.1. But, the archetype Barahmasa poetry and the inspiration for all forms of Barahmasa expressions are Keshavadasa’s sublime verses scripted in Brij-basha. The poet Keshavadasa (1555–1617) in his Rasikapriya (a comprehensive compendium of nayakas and nayikas, their moods, meetings and messengers, considered a lakshana grantha, foundational work, in riti kavya tradition), he vividly describes the essential features of the twelve lunar months of the year; and the pain each month evokes in the heart of the nayika at the impending separation from her beloved.

9.2. Starting with the month of Chaitra, Keshavadasa portrays the heroine urging her beloved not to leave her in that month; describing to him the beauty and tenderness of that month. She cajoles him to stay with her; and to enjoy along with her the thrill and ecstasy of living and loving in the paradise on earth created especially for their enjoyment. She convinces him that it is a blessing to be alive amidst that beauty. Such loving requests follow in each of the other months too; as every month has something special that makes separation painful and unbearable.

The following are briefly the suggestive descriptions of Barahmasa according to Rasikapriya.

Chaitra: charming creepers and young trees have blossomed and parrots, sarikas and nightingales make sweet sounds.

Baisakha: the earth and the atmosphere are filled with fragrance and all around there is fragrant beauty, but this fragrance is blinding for the bee and painful for the lover who is away from home.

Jyestha: the sun is scorching and the rivers have run dry and mighty animals like the elephant and the lion do not stir out.

Ashadha: strong winds are blowing, birds do not leave their nest and even the sadhus make only one round.

Shravana: rivers run to the sea, creepers have clung to trees, lightning meets the clouds, and peacocks make happy sounds announcing the meeting of the earth and the sky.

Bhadrapada: dark clouds have gathered, strong winds blow fiercely, there is thunder as rain pours in torrents, tigers and lions roar and elephants break trees.

Ashvina: the sky is clear and lotuses are in bloom, nights are brightly illuminated by the moon, people celebrate the Durga festivities and it is time for paying respects to ones ancestors.

Kartika: woods and gardens, the earth and the sky are clear and bright lights illuminate homes, courtyards are full of colourful paintings, and the universe seems to be pervaded by a celestial light.

Margashirsha: rivers and ponds are full of flowers and joyous notes of hamsas fill the air, this is the month of happiness and salvation of the soul.

Pausha: the earth and the sky are cold. It is the season when people prefer oil, cotton, betel, fire and sun shine.

Magha : forests and gardens echo with the sweet notes of peacocks, pigeons and koel and bees hum as if they have lost their way, all ten directions are scented with musk, camphor and sandal, sounds of mridanga are heard through the night.

Phalguna: the fragrance of scented powders fills the air and young women and men in every home play holi with great abandon.

9.3.The Barahmasa poetry reflects the moods of the lovers in the brilliant spring, sad autumn or monotonous winter; but none is so evocative as of the splendour and awe inspiring beauty of the Indian monsoon. It is uniquely Indian. Further, the Indian attitude to the monsoons is fundamentally different from that of the west. To a common Indian villager, monsoons are a symbol of hope and life; while a westerner might view rain and snow as a sign of gloom and despair.

When the rains come down like blessings from heaven, suddenly the world looks beautiful; the earth smells lovely, and the heart smiles! The bond that India has to rains is much like the colder nations of the North have towards spring. A lot of our happiness and physical well being is associated to raining, raining well and raining in time.

Monsoon poetry

10.1. Whether we are talking about music – classical, folk as well as devotional – dance, painting or sculpture, the rains and their incessant music are a recurring theme in India’s many-splendored art treasure. The diverse dialects of India’s far flung villages are replete with songs welcoming the life giving rains flowing down from heavens like blessings; and their message of bounty. And, they allude that just as all rain water falling from the skies flows to merge with the ocean, all living beings flow finally into the shining pool of divinity. The divine object of their single-minded devotion is Krishna – the Ghanashyam, dark like the monsoon clouds, the one born on a rain-stormy night in the monsoon month of Shravana. And Krishna the dark one is the icon of the monsoon season and the songs dedicated to him are composed in the soul-soothing monsoon Raga Megh Malhar. The romance of Radha and Krishna, the eternal lovers, is the theme of rain songs. The constant longing of any beloved waiting for her lover to return home is envisioned as an epitome as of Sri Radha.

10.2. As the Krishna-Sri Radha celestial love permeated into folk music and dance as well as into the celebration of festivals, the songs about their love created a treasure-house of Kajris, Shravan jhoolas, chaitis, thumris and other light classical music compositions with an edgy eroticism.

10.3. These soulful songs celebrate various seasons and sometimes the festivals occurring during such seasons, such as Holi in the month of Phalguna. In most cases Sri Radha is the lonely Nayikaconstantly longing and waiting for her beloved Krishna the eternal lover. In other cases it is a Nayikaseparated from her loved one, usually a warrior, in whose context the cycle of the changing seasons is depicted.

Barahmasa Music

11.1. The raga melodies of classical Indian music are in harmony not only with the time of the day or night but also with the seasons of the year. Each raga is personified by a colour, the overall mood bhava, the nature surrounding the hero and heroine (nayaka and nayika). The raga elucidation as envisioned in Indian music is a delightful amalgam of art, colour, poetry and music.

11. 2. As regards the seasons and the ragas, most of the ragas in the classical music are set in accordance to various seasons. Generally:

Basant (chaitra – vaishakha): the ragas Hindol and Raga Bahar sung early in the dawn are associated with the festive and invigorating season of spring Basant (chaitra –vaishakha) when kimshuka trees are full with lustrous red flowers; mango trees laden like bejewelled women; pond waters filled with lotuses; breezes loaded with their fragrances blowing pleasantly; the eventides and daytimes enjoyable with the fragrant breezes; air ringing with the passionate cries of male koil birds; and, women brimming with desire sporting in swimming pools like she elephants in heat; and bashful ladies playfully dressed in light silks of reddish hue of kusumbha flowers. The women decked in pearl pendants and in just unfolded whitish flowers of jasmine (mallika) and karnikara; and in red Ashoka flowers.

Grishma (jeshta –ashadha): raga Deepak sung during the evening of the Grishma (jeshta –ashadha) season of blazing summer light and the grief of separation when men are away from home on work or trade or war. And, the women decked in white pearly ornaments, jasmine garlands, cool silks and dabbed in pure sandalwood paste liquefied with coolant scents like yellow camphor, kastuuri etc laze on rooftops in moonlit nights savoring portions , enjoying music , lustfully awaiting their husbands or lovers. Just blossomed bright and fiery safflower kusumabha embrace the tree trunks with tongues of fire. Fragrant lotuses and patala (trumpet flowers) are overlaid on cool waters of the pond,

Varsha (shravana-bhadrapada : Raga Megha or Megh- Malhar or Desh and their derivatives sung during the midday of the rainy season of the Varsha (shravana-bhadrapada); the most romantic of all seasons ; the season of dark clouds rumbling like beats of war drums , the thunder and flashes of lightning ,the gentle patter of raindrops and the pageant of rainbows ; the season that delights the thirsty chataka birds, the lustily cheering peacocks brilliant with fanlike expansive colourful plumage; the season that captures the joy and relief from dry heat, the season that brings life and hope to all existence. The breeze is ruffling the wet treetops of Kadamba, Sarja, Arjuna and ketaki trees; and the fragrance of their flowers is wafting through the windswept woodlands. The intoxicated women decked in vakula, malalthi, Kadamba, Kesara and ketaki flowers and with bunch of Kakuba flowers adorning their ears, are hasting into the bed cambers and into the arms of waiting lovers.

Sharada (ashviyuja-karthika): the serene Raga Bhirav sung in tranquil mornings of the season of bright sun, lustrous moon; glowing blue sky; gentle flowing rivers with clear waters; lakes with abundance of white and blue lotuses and lazy swans floating just after a long flight from Lake Manasa in the Himalayas; trees pleasantly laden, swaging under the weight of flowers and fruits; the transitional phase between rains and winter is blessed with bounty of nature. The green earth is decked with red golden colourful trees; the grand flowers of Kadamba, Sarja, Katuja, Arjuna, and Nippa; and of the Shyama creepers as also flaming red Banduka flowers. The fragrance of those flowers is intoxicating. The joyous women with long, thick, black hair unfurled wearing pendants of pearl and gold are adorned in white jasmine and colourful lotuses

Hemanta (margashira-pushya) – The season is associated with the lofty raga Shree sung during late autumn twilights. Winter with the earth wet with dew; the sky filled with fog; men shivering from the cold, but crows and elephants seem euphoric. The lusty women retain body-heat by smearing their bosoms red with Kashmir kumkum and fragrant wood-turmeric (kalliyaka) skincare. And their hair is fumigated with vapours of kaala agaru ( aloe vera resin).

Shishira (magha –phalguna): the transitory season of cool days; the diminishing phase of winter; the season of cool comfort gladdening the hearts of lusty women with Malkoaunsa Raga sung in the chill and silent nights of winter.

11.3. It is said; the Seasonal Ragas can be sung and played any time of the day and night during the season with which they are associated despite the usual rule.

Miniature paintings

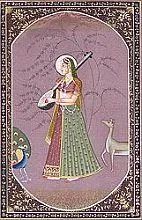

12.1. A vast number of schools of miniature paintings such as Bundi, Krishnagarh, Jaipur, Mewar and Marwar giving expression to the Barahmasa concepts and idioms flourished during the mid centuries under the patronage of Pala Kings of Bengal , the Mughals and the Rajputs of Rajasthan. The hill states and even smaller states from Central India too nurtured the paintings of Barahmasa tradition. Datia, one of the schools of painting in Central India, painted a timeless series of Ashtayama, another form of Barahmasa. . These sublime works of art, which gained fame as iconic representations of the seasons and as metaphors for emotions, have inspired generations of artists, poets and lovers. Over the generations, the artists of the diverse schools of miniature paintings have strained to retain the aesthetic values and technical excellence achieved by their pioneers.

2.2. In most of these depictions Krishna is the central figure of love and the embodiment of the magic of the seasons and the melodies specially associated with the season. Its scenery epitomizes the landscape of the imagination, in Indian painting. The Barahmasa schools lovingly capture the delights, the emotions and the enjoyment of the lovers in each of the six seasons. These pictures do tell a tale; each one narrates an event that illustrates the beauty, love and togetherness in the lives of the lovers. That story is entwined on the splendour of nature that surrounds them, in each season.

C. Ragamala

13.1. During the later periods, say by about the fourteenth century, the music- literature developed a series of short verses, in Sanskrit, called Dhyana slokas meaning verses for contemplation , outlining in brief the characteristics (swaroopa) of the raga expressions (raga –bhava) , treating a raga as a human person (nayaka –nayika) , divine (devatha) or semi-human being (gandharva). It also provided for descriptions of Raga wives, (ragini), their numerous sons (ragaputra) and daughters (ragaputri). This poetry often amorous, illustrates the love of a maiden and her lover.

13.2. This led to the creation of Ragamala (garland of Ragas) School of painting which attempted translating the emotional appeal of a raga into visual representations. Each raga personified by a colour, mood, the nature surrounding the hero and heroine (nayaka and nayika). It also elucidated the season and the time of day and night in which a particular raga is to be sung. The colours, substance and the mood of the Ragamala personified the overall bhava and context of the Raga. It is a delightful amalgam of art, colour, poetry and music.

The Barahmasa and the Ragamala – series of paintings are the evidence that the native genius in painting had survived the vicissitudes of political history since the days of Ajanta.

13.3. The development of the Ragamala School, however, got rather stunted as its theme lost relevance in the context of the present-day music. Further, the school did not seem to have the flexibility to accommodate and to describe newer raga innovations. The wonderful school therefore has virtually now faded away, sadly

14.1. Yet, the raga-ragini classification is still useful from the historical, academic, artistic and philosophical perspectives; and, could perhaps even help in understanding and performing music.

[ Dr. Anjan Chakraverty who did his post-graduation in Landscapes in Indian Miniature Painting from the Faculty of Visual Arts, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, explains:

http://vmis.in/upload/Assets/Exhibition/23/ragmala/part2.html

Every raga has its special sequence of ascending notes (aroha) and descending notes (avaroha) that determine its structure or that (lit. an array or setting). A raga experience would change from dawn to dusk, from a sunny afternoon to a moonlit night, from spring to autumn, so on and so forth. On the basis of this, ragas and raginis were associated with particular moods and regions, with particular seasons and, categorically, to the explicit hours of the day and night.

For example Dipaka raga was associated with fire and scorching heat while the recital of Megha raga, in contrast, was ideal for the season of clouds and rains, its flawless rendition promising downpour. Similarly, Vasanta raga is meant to express the joy of life in spring and Nata raga, the heroic martial spirit of the man. Bhairavi ragini is the plaintive melody of the morning and raga Yaman is meant to evoke the somber, explicitly devotional mood in the early hours of the evening. However, a raga is not a song or tune, on the other hand numberless songs can be composed in a certain raga-mould.

With a view to emphasize the divine qualities of music, each raga and ragini was attributed with a particular rupa or psychic form. The psychic form was further divided into the invisible sound form or the nadamaya rupa and tangible or image form referred to as devatamaya rupa. It was required on the part of a performer (kalavanta) to imbibe the presiding spirit or ethos of a melody and please the deified form. Raga-dhyanas or contemplative prayer-formulas were devised for the purpose, passed on from the master (acharya) to the student.

In Narada’s Sangita Makaranda, datable between 7th and 11th century C.E., do we come across for the first time a classification system of six ragas as male and six raginis, attached to each raga, as females forming six cohesive families, raga-parivara. However, this system was not followed by the painters.

It is in the Sangita Makaranda that we find for the first time a classification of ragas according to the proper hour for rendition. Mesakarna or Kshema Karna, a sixteenth-century rhetorician from Rewa (central India), in his treatise Ragamala compiled the elaborate system of six ragas, each with five raginis and eight ragaputras.]

List of books and other references.

Rtu in Sanskrit Literature by Dr. V Raghavan; Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri Kendriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha, Delhi (1972)

Kavyamimamsa of Rajasekhara: Original Text in Sanskrit and Translation with Explanatory Notes by Sadhana Parashar, D K Print world, (2000)

Vishnudharmottarapurana: English translation by Priyabala Shah, Baroda (1961)

The Seasons in Mahakavya Literature, by Danielle Feller : (1995 )

Barahmasa in Indian Literature, Charlotte Vaudeville; Triloki N. Madan (1986)

Barshmasa (Agam55) by V. P. Dwivedi

Baramasa: The Painted Romance of Indian Seasons (Portfolio) by Daljeet, National Museum, (2009)

The Flute and the Lotus: Romantic Moments in Indian Poetry and Painting by Harsha Dehejia, (2002)

The Loves of Krishna in Indian painting and poetry by WG Archer

Flora and Plant Kingdom in Sanskrit Literature by Shri Jyotsnamoy Chatterjee; Eastern Book Linkers, (2003)

Ritusamharam: http://www.giirvaani.net/giirvaani/rs/rs_intro.htm

Monsoon Ragas by Vimla Patil : http://www.esamskriti.com/essay-chapters/Monsoon-Ragas-1.aspxBarahmasa:

Songs of Twelve Months by Prof P. C. Jain and Dr. Daljeet http://groups.google.com/group/mintamil/browse_thread/thread/9b6cabddd8d32161?pli=1

Romantic Moments in Poetry : http://http-server.carleton.ca/~hdehejia/content/RMinPoetry.pdf

Bidyapati’s Description of spring: http://www.indiadivine.org/articles/382/1/Bidyapatis-Description-of-Spring/Page1.html

History of Flowers and Gardening in India By Dr. Jyoti Prakash : http://www.cityfarmer.org/indiagarden.html

All pictures are from internet

physical body(ananga).These relate to mental pleasures derived through five organs and through the modalities of mind: rejection(repulsion or withdrawal), acceptance (attention or attachment) and indifference(detachment).

physical body(ananga).These relate to mental pleasures derived through five organs and through the modalities of mind: rejection(repulsion or withdrawal), acceptance (attention or attachment) and indifference(detachment).

T

T T

T