The music of Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar

Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar was a versatile intellect. He was open to varieties of influences. His works reflect some of those influences rather explicitly ; while some others shine through in a subtle way. Before we get into a discussion about Dikshitar’s creations, we need to recognize a few features that influenced him.

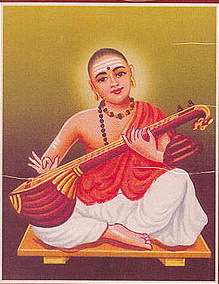

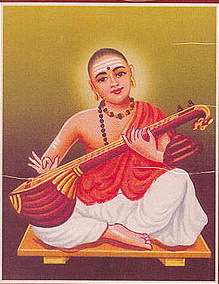

Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar was a vainika-gayaka, a musician who sang as he played on the Veena. He was well trained both in vocal and instrumental music. Naturally, the graces, the rich Gamaka prayogas of his compositions structured in slow tempo shine in mellow glow when played on the Veena.

In his childhood, he received training in the Lakshya and Lakshana aspects of Carnatic music. The Lakshana Gitams and Prabandhas of Venkatamakhi formed an important input of his training. Later, as a composer, he chose to follow Venkatamukhi’s system of Mela -classification of Ragas.

He spent seven years at Varanasi, in the prime of his youth. He was captivated by the grandeur, the spaciousness and the purity of the ancient Druphad School. He learnt Dhrupad diligently; and ,that left a lasting impression on his works.

Earlier in his teenage, he gained familiarity with Western music; and, the traces of its influence can be noticed in the movement of his songs.

He had a good command over Sanskrit; and, learnt to use it to express his ideals and aspirations in pristine poetry. He had a fascination for Sabdalankara, beautifully turned phrases and wordplay . He had the composure of a yogi and the heart of a poet. Dikshitar’s kritis are therefore adorned with poetic imagery, tranquil grace, a certain majesty steeped in devotion.

Sri Dikshitar had acquired a fair knowledge of Jyothisa, Ayurveda, and iconography and of temple architecture.

He was unattached to possessions or to a place . He was a virtual pilgrim (jangama) all his life. He visited a large number of shrines ; and, sang about them and the deities enshrined there.

He was intensely devotional ; yet, was not overly affiliated to a particular deity. He composed soulful songs in praise of a number of gods and goddesses.

He had a fascination for composing a set of kritis exploring the various aspects of a particular deity or the different dimensions of a subject , as if he had undertaken a project.

He was an Advaitin, well grounded in Vedanta.

And above all,

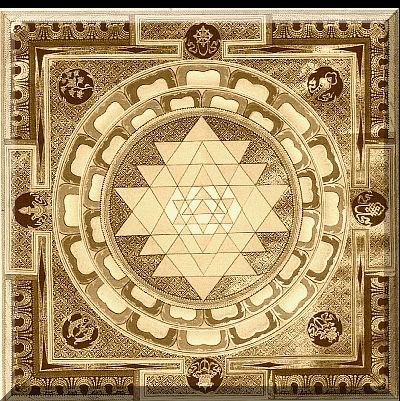

Sri Dikshitar was an ardent Sri Vidya Upasaka; a Sadhaka, an intense devotee of Devi, the Divine Mother. He was a master of Tantra and of Yantra Puja. The Tantra ideology permeates all through his compositions.

It is the harmonious confluence of these influences that one finds in Dikshitar’s music.

***

Output:

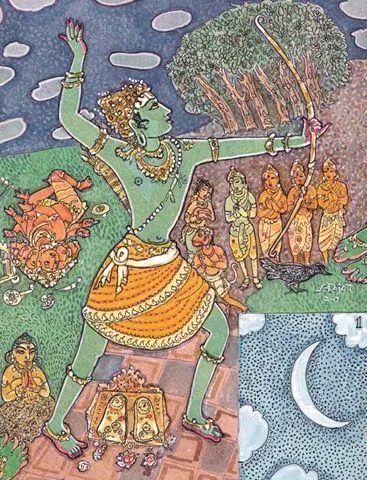

Anandamruthavarshini by Shri S Rajam

Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar was prolific; about 479 of his compositions have now been identified, spread over 193 ragas. These include four Ragamalikas and about forty Nottuswara sahithya verses.

[For a detailed statistical analysis of the compositions of Sri Dikshitar , as undertaken by Dr. P. P. Narayanaswami , please click here.

Please do refer to a very remarkable site created by a group headed by its Chief Data Analyst – Smt. Meera Subramanian , listing as many as 510 compositions of Sri Muttuswamy Dikshitar, along with its lyrics , audio and video files as also the deity-wise classification of his Kritis.

For the list of Dikshitar compositions compiled by Todd Mc Comb , please click here

The Website of Rasikas.org has listed 481 compositions of Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar . These include the four sub-categories : Guruguha Vibhakthi; Neelothpalamba Vibhakthi;Pancha-bhutha-linga Vibhakthi; and, Samgita Sampradaya Pradarshini ]

The great Venkatamakhi who formulated the 72 Mela-kartha ragas is reported to have wondered ”of the 72 Melas only a few are known and found in practice… and will the permutation be a waste.?‘(Dr. V Raghavan: paper presented at All India Oriental conference, at Hyderabad, 1941).

It was the genius of Muthuswami Dikshitar that gave form and substance to all the 72 Mela-kartha ragas, fulfilling the dream of Venkatamakhi. He gave expression to nearly 200 ragas of that system.

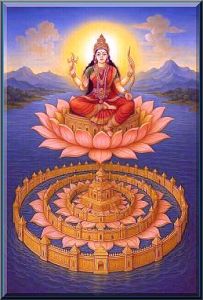

Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar was a pilgrim virtually all his life. He visited a large number of shrines and sang about them and the deities enshrined there. He was intensely devotional yet not overly affiliated to a particular deity. He composed soulful songs in praise of a number of gods and goddesses. About 74 of such temples are featured in his kritis; and there are references to about 150 gods and goddesses. The most number of his kritis (176) were in praise of Devi the mother principle, followed by (131) kritis on Shiva. Dikshitar was the only major composer who sang in praise of Chaturmukha Brahma.

Sri Dikshitar has composed songs in honor of some other lesser-known divinities : Saṇdhyā dēvīm Sāvitrīm-Rāga Dēvakriya, Ādi-Tāla; Bhūśāpatim – Rāga Bhūṣāvati, Rūpaka Tāḷa; and, Renukādēvi Samrakśtōham – Rāga Kannada Bangāḷa, Miśra Jhampe.

**

Some scholars have said that Dikshitar’s songs are summaries of Durga Suktam, Sri Suktam and Purusha Suktam. He built in the mantras in a few krithis like Sri Raaja raajeshwari (madyamavathi), pavanatmaja aagaccha (Naatta). For the benefit of those who couldn’t practice rituals he composed vaara krithis on navagrahas.

Similarly, he opened the doors to the secret world of Sri Vidya, for the benefit of all, through his Kamalamba navavarana kritis.

Krithi Groups

Dikshitar had a fascination for composing sets of kritis on a composite theme, perhaps in an attempt to explore the various dimensions of the subject. In some of these, he employed all the eight Vibhaktis, the various cases that delineate a noun. No other composer has attempted so many group kritis in such a planned, orderly, meticulous fashion. The following are some Important Krithi Groups. Please also check here.

The selection of Raga and Taala; and the diction of these kritis demonstrate his musical skills and intellectual refinement.

For greater information on Group Kritis of Dikshitar, please check here.

Ragamalika

Just as his father Sri Ramaswamy Dikshitar (who had composed the longest ever Raga-malika in Karnataka Samgita- the Ashtotrasata ragatalamalika – set in 108 Ragas and various Taalas) , Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar was also an adept in the Raga-malika format. Though he did not attempt anything as lengthy or as grand as his father did, the four delightful Raga-malikas that Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar created are true gems of art.

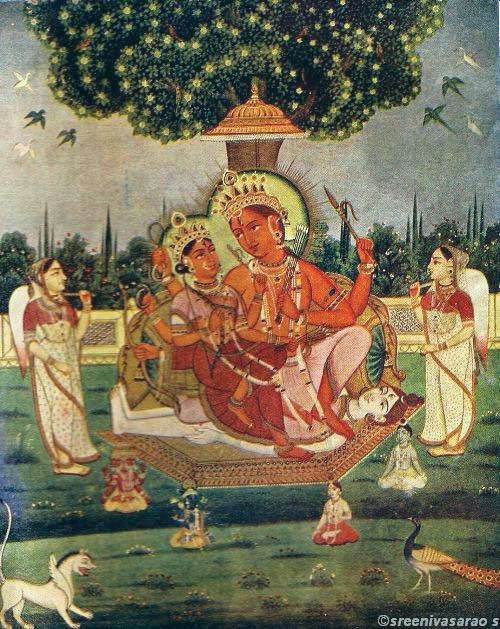

: – ‘Madhavo-mam-patu‘– is a Raga-malika on the ten avatars of Lord Vishnu, with ten passages set to ten Ragas (Nata, Gaula, Sri, Arabhi, Varali, Kedara, Vasanta, Surati, Saurashtra and Madhyamavati).

Of the ten Ragas employed in the Raga-malika, five are Ghana-ragas excellent for rendering Taana on the Veena. The sixth Raga Kedara , is invigorating and the last four Ragas are Mangala Ragas leading up to the final Mangalam in Madhyamavati.

The Raga of each passage blends admirably well its Sahitya. Here too, Sri Dikshitar adopts his favorite Vibhakthi scheme of addressing the subject. The first eight passages are in the eight Vibhakthi cases, in their order (krama) ; and , the rest two- ninth and tenth are in the accusative case .

While rendering the Raga-malika, the singers can progress from one passage to the next without having to repeat the Pallavi of the just concluded passage.

: – The Ragamalika ‘Purna-chandra-bimba-vadane‘ in celebration of Goddess Kamalambika at Tiruvarur is composed of six Charanas in six different Ragas: ‘Shad-raga-malika‘. The Ragas are: Poornachandrika, Saraswatimanohari, Narayani, Suddhavasanta, Hamsadhwani and Nagadhwani; and, all the six belong to ‘Dheera Sankarabharana’ (29th) Mela, Sri Dikshitar’s favorite.

: – The third Raga-malika ‘Simhasana-sthite‘ in four passages is addressed to most graceful Devi seated on her throne in a serene tranquil posture. The four are Mangala-prada Ragas, auspicious, soothing and peaceful – Saurashtra, Vasanta, Surati and Madhyamavati. This Raga-malika is therefore sung at the conclusion of Sri Dikshitar’ annual celebration festivals. It is also a favorite of the Bharatanatyam dancers.

:- Perhaps , Sri Dikshitar’s most famous Raga-malika is his ‘ Chaturdasha Raga-malika’ – ‘Sri Vishwanatham bhajeham’ set in fourteen Ragas singing in ecstasy the glory of the Lord of the universe Shiva. The fourteen Ragas are interwoven with the passages in an intricate pattern.

Chapter 12 of Shqdhganga describes this Ragamalika as

“ The Pallavi has two Ragas, starting with Sri Raga; and, each Raga is encapsulated in two lines of one Avarta; the second being in Madhyama kala. Similarly, the Anu-pallavi is set to four Ragas : Gauri, Nata, Gaula and Mohanam. But, at the end, after Mohanam, a Viloma passage takes us through the same four ragas of the Anu-pallavi and the two of the Pallavi in reverse order, back to Sri.

The same pattern is followed in the Charanam with eight Ragas : Sama, Lalita, Bhairavam, Saranga, Sankarabharanam, Kambhoji, Devakriya and Bhupala. And, these are again taken in reverse order in a Madhyama-kala sahitya, back to the Pallavi in Sri.

Sri Dikshitar has followed a pattern not only in the order of the occurrence of the Ragas, but also in terms of the lengths of the Avartas for each Raga.

The fifth and sixth Ragas- Gaula and Mohanam – have been allotted 1 ½ Avartas, all in Madhyama-kala; while the preceding Ragas have been given 2 full Avartas – one each in Sama kala and Madhyama kala.

The same pattern has been followed in the first half and second half of the Charanam of the Raga-malika. Another striking feature of the Sahitya of this Raga-malika of Sri Dikshitar is that the last part of the Svara-sahitya set to each Raga is composed of the same words as of the last part of the preceding line of Sahitya.”

Chronological order

It is rather difficult to arrange Sri Dikshitar’s compositions in a chronological order.

His Nottuswara-Shitya verses were, of course, composed in his early years while his family lived at Manali a small town near Madras. His first composition as Vak-geya-Kara was Srinathandi in Mayamalava-gaula, at the hill shrine of Tiruttani; and, his last composition was Ehi Annapurne in Punnagavarali while he was at Ettayapuram during his last years.

It is believed that the set of Vibhakti kritis followed his first composition. Thereafter, he traveled to Kanchipuram, Mayuram, Chidambaram, Vaidyanatha koil and Kumbhakonam. He often visited Tiruchirapalli (where it is said his daughter lived).

He spent his productive years at Tiruvavur and his final years in Ettayapuram. In between, he is believed to have visited about 70 temples; and, sung the glory of those deities. It is however not possible to arrange those kritis in a sequence.

Please check here for a map of his probable travels in South India:

Before going further, we need to talk a bit about Sri Muttuswami Dikshitar’s first Kriti as a Vak-geya-Kara , Srinathandi-guruguho-jayati in the Raga Mayamalava-gaula in the fifteenth Mela (the Mela in which Sri Dikshitar composed many Kritis) . The mantra of Sri Vidya also has fifteen matras (syllables).

After submitting salutations to the past Gurus of the Kadi-matha, the principal tradition of the Sri Vidya lore (shri nathadi guruguho) , Sri Dikshitar bows down to his Guru Yogi Chidambaranatha. Elsewhere, in another Kriti composed in Raga Purvi, a Bhashanga-janya-raga of Mayamalava-gaula, Sri Dikshitar adores his Guru and Master Chidambaranatha as none other than Guruguha; and , says ‘I am the humble servant of Guruguha, or I, myself, am of the form of Guruguha himself’

-shri guruguhasya dasoham nocet cidguruguha evaham.

The opening line Srinathandi-guruguho-jayati-jayati, which bows to all the deities and Gurus of the Sri Vidya traditions, has been much debated. This line is said to be an almost a takeoff from the opening lines of the first shloka of the Sri Vidya paddhathi:

Shri nathadi gurutrayam ganapatim pithatrayam bhairavam / siddhaugam vatukatrayam padayugam dutikramam mandalam/ viran dvyasta catushka shashti navakam viravali pancakam/ srIman-malini-mantra-rajasahitam vandeguror mandalam

This Shloka invokes the deities and the galaxy of Gurus (Guru-mandala) in the realm of the Supreme sovereign Srividya Parabhattarika. It begins with salutations to the three generations of Gurus (Srinathadi gurutrayam – one’s own Guru; his Guru – Parama Guru; and his Guru – Parameshthi Guru) ; and prayers to Ganapathi (Ganapatim).

It also recalls with reverence the three centres or seats of Shakthi (Piitha-trayam – Jalandhara, Purnagiri and Kamarupa); the eight Bhairavas (Bhairavam); the Siddhas (siddhaugam); the three celibates Brahmacharis (vatukatrayam – Skanda, Chitra and Virinchi); and then, submits to the feet of the Mother Goddess (Padayugam).

Then salutations are submitted to the group of Duti goddesses (dutikramam mandalam); to those who have attained Siddhi (Viran); to the sixty-four Siddhas (dvyasta catushka shashti); nine Mudra goddesses (navakam); and to the five supreme deities (viravali pancakam– Brahma, Vishnu, Rudra, Ishwara and Sadashiva).

Then, at the end, the devotee submits to the Goddess of Malini-Chakra with Mantra-raja; and, to all the Gurus of all the traditions of Sri Vidya (vande-guror mandalam).

Likewise, Sri Dikshitar, in his Kriti –jayati , submits to his Guru, the Lord of the Universe, and all the Gurus of the Kadi Matha of the Sri Vidya tradition. And, to the Srividya Parabhattarika, the supreme Mother Goddess, who is invoked by the mantra beginning with Ka and ending with Ma (The Kadi Vidya of Sri Manmatha runs: KA, E, I, LA , HRIM- vagbhavakuṭa), residing in the centre of the Mani Chakra which resembles a thousand-petalled lotus.

And, to Maheshwara the Lord who obliterates all types of illusions and delusions; who is meditated upon constantly by Hamsa mantra , the Ajapa-japa (you breath out with a sound of ’Sa’; and you breath in with a sound of ‘Ha’; and, throughout the day and night you perform the Hamsa Japa.

(The Hamsa Japa is : I am He , Shivo Hum, I am Shiva , breathing in and out continuously , instinctly and with ease , without being aware of your doing so. This effortless and ceaseless Japa is called Ajapa-japa).

And, to the Guruguha, Skanda, who is worshiped by kings of Mayamalava Gaula Desha and others; who is surrounded by Vishnu and other gods; and, who has expounded the real truth of Pranava to His father Mahesha.

**

The composition, ‘Sri Nathadi guruguho jayati jayati’ in Mayamalava-gau!a is ideal for the music students to practice in graded speeds, the ascent and descent of the Raga, the janta svara prayogas, alankara patterns, mandra-sthayi phrases etc.

In terms of Music, the first line of the Pallavi (Srinathandi-guruguho-jayati -jayati) summarizes all the ascending (Arohana) and descending (Avarohana) notes of the Mayamalava gaula: “SA RI Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni SA Ni Dha Pa Ma Ga Ri”, in all the three speeds (kaala).

[ It is said; upon his initiation into Sri Vidya Upasana , Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar was assigned the ordained name ‘Chidananda-natha‘. In the Pallavi of his first Kriti ‘, ‘Sri Nathaadi Guruguho Jayati,’ he refers to himself by his Diksha-name (rahasya-nama) as : ‘Sri Chidananda Naathoham iti’- श्री चिदानन्द नाथोऽहमिति ]

And , in regard to Sahitya , The prathama-akshara- prasa in the Charana and in the Madhyama-kaala–sahitya is very interesting , where each line commences with ma or Ma.

Charanam:

- MAyamaya vishvadhishthano

- MAtmaka kadi matanushthano

- MAlini mandalanta vidhano

- MantrAdyajapa hamsa dhyAno

- MAyakarya kalana hIno

- mAmaka sahasra kamallsiIno

- mAdhurya ganamrita pano

- mAdhavadyabhayavarapradano

- mAyashabaLita brahma rupo

- mArakoti sundara svarupo

- matimatam hridayagopuradIpo

- mattashuradi jayapratapo

- mAyamalavagauLadidesha

- mahipati pujita pada pradesha

- mAdhavadyamara brinda prakasha

- maheshasya maharthopadesha

Madhyama Kala Sahityam:

- MAyaamaalavagaulaadidesha

- Mahipati Pujitha Pada Pradesha

- MAdhavaadyamara Brunda Prakaasha

- Maheshasya Mahaarthopadesha

Ragas:

Dikshitar followed the Mela-paddhati (a system of classifying Ragas) devised by Venkatamakhi, to whose school he belonged. In handling the Vivadi-melas, Dikshitar followed Venkatamakhi; and, avoided inharmonious expressions, prayogas.

Further, since Kharaharapriya was not a part of Venkatamakhi’s scheme; there is no known composition of Dikshitar in that Raga. The twenty-second Mela-karta was Sri Raga; the Mangala kriti of the Navavarana series is composed in Sri Raga. Again, the Venkatamakhi-tradition treated Bhairavi and Anandha Bhairavi as Upanga Ragas; so did Sri Dikshitar.

[Though Sri Dikshitar generally followed the Asampurna-Mela system of Venkatamakhin, he was quite familiar with the other, Govindacharya’s Sampurna-Mela system as well.

For instance; the Raga of his Kriti Shri-shulinim-shritapalinim according to Asampurna-Mela is Shailadeshaksi. But, in the Kriti, he uses the Raga-mudra as Shulinim , which is the Raga-name in the Sampurna-Mela system.

Similarly, the Raga of his Kriti Hariyuvatim-haimavatim is Deshi-simharavam according to the older system; but, the Raga-mudra is Hemavathi which is the corresponding Raga-name in the other system.

And, his Kriti Shri Nilotpala-nayike in Raga Nari Ritigaula contains the Raga-mudra Natabhairavi in the Anupallavi as per the Sampurna-Mela system.]

Some scholars opine that Sri Dikshitar’s major service to Carnatic music is that he gave expression to nearly 200 Ragas of Venkatamakhi’s system. He also breathed life into a number of ancient Ragas that were fading away. Several ancient Ragas found a new lease of life though Sri Dikshitar’s kritis.

To name a few of them: Mangalakaisiki, Ghanta, Gopikavasanta, Narayana Gaula,Sulini, Samantha, maargadhesi and mohana naatta. Even today, their Lakshanas are illustrated mainly through Sri Dikshitar’s creations.

There are many Ragas which are employed only by Dikshitar. Take for instance: Saranganata, Chhaya Goula, Poorvi , Padi , Mahuri , Suddhavasanta ,Kumudakriya, and Amritavarshini.

In the Raga Dwijavanti, his Kritis Chetasri and Akhilandeshwari stand out in solitary splendor.

He transformed many Outhareya, the Hindustani Ragas into Karnataka form through his creative genius. His interpretation and rendering of Ragas like Dwijavathi, Ramkali, and Yamankalyan, Hamirkalyani, and Brindavan sarang are highly original and creative. He made them into his own. His Cheta-sri is so wonderfully well adapted to Carnatic Raga-bhava that one scarcely notices the Outhareya traces in its character. He took in the best aspects of the other system; transformed them ; and, enriched both the systems.

Shankarabharanam scale appears to have been his forte. There are as many as 96 kritis based on that scale. The kritis in Harikambhoji scale number about 63; while 57 kritis are in Kharaharapriya scale. He had a special affinity for Mayamalava-gaula in which he composed about 51 songs. The derivatives of that scale such as Saalanga Nata, Paadi and Mangala Kaishiki would have been lost but for Sri Dikshitar.

**

About forty-four of his compositions are set in forty Vivadi Ragas. Since Sri Dikshitar followed the A-sampurna-Mela-Paddathi of Venkatamakhin , even the Janaka-Ragas might look like Janyas. But, in fact, all those Vivadi-Ragas are Raganga or Melakartas. However, they do not have Vivadi-Svara-Sancharas. For instance; Raga Shuddha-Saveri under Kanakambari; and Manohari under Gangatarangini.

As many as forty of these Melas, are Vivadi-Ragas. Sri Dikshitar uses many means (Upaya) to counteract the jarring-effects of Vivaditva. These measures include :

-

- (i) Janti prayōga – using the Svara in pairs to reduce the Vivadi- effect;

- (ii) Alpatva – minimum usage or skipping of the Vivadi-Svaras;

- (iii) Dheergha-prayoga -Elongating one of the Vivadi Svaras to smoothen its effect; and

- (iv) Langhana or Dhatu-prayoga-using crisscross Svara pattern to reduce the Vivadi effect.

[ Please do read about the frequency Analysis of the Ragas used by Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar , as attempted by Sri Vishnu Vasudev. Please click here.]

Taala:

Sri Dikshitar was accomplished in the matter of Taalas, the rhythmic patterns. He is the only composer to have set his music in all the seven basic Taalas. He employed all the Saptha (Seven) Taalas in his Vara-Stutis i.e. a song for each day of the week. He is said to have used ten improvised varieties of Taalas in his compositions. The majority of his compositions are set in Adi (190) and Rupaka (139) Taalas.

Sri Dikshitar, in his compositions, has employed only Suladi Taalas; to the exclusion of Chapu and other Taalas. Each of his Nava-Graha Kritis is set in a different Suladi Taala.

Music:

The most fascinating aspect of Sri Dikshitar’s Kritis is the grandeur and majesty of his music, sublime lyrics, intellectual brilliance and the overall technical sophistication. They exude a tranquil joy. His vision of the Ragas and their structure is truly inspiring.

Sri Dikshitar was blessed with the heart of a poet and the composure of a yogi. He was an intense devotee; but, was undemonstrative. There is, therefore, a certain composure, measured grace, dignity and a mellow joy glowing through his music, as in his life.

The Druphad way of elaboration captured his imagination. The tempo of his songs is mostly the Vilamba-kala – slow, measured and majestic; rich in Gamaka just as the meends on a Veena. Sri Dikshitar aptly called himself “Vainika-gayaka Guruguha-nuta”.

[The musical structure of his Kritis display how well they are suited for playing on the Veena. For instance; he has employed wide Jaarus extensively in the phrase Murari-prabhruti occurring in his Kriti Sadashivam-Upasmahe (Raga Shankarabharanam; and, there is a Jaru from lower Shadja to Tara-sthayi -Rishabham). And again, the first line of the Charana of the Kriti Tyagaraja Maha-Dwajaroha (Raga Shri) has an elaborate Jaru :

Srishti-svarupa-vasanta-vaibhavam-ashtadhvajendra-vimana-bhuta-samashti-gaja-vrishabha-kailasa–vaham-ashlesha-mah-aratha -sthitam.]

Sri Dikshitar’s treatment of a Raga exemplifies the essence of the Raga bhaava; and, brings out its delicate shades. It is as if the musician is immersed in contemplative meditation. The graces, the rich Gamaka–prayogas of his compositions structured in slow tempo shine in mellow glow when played on the Veena.

This is amply reflected in his works ; for instance in

The other compositions of this genre are: Dakshinamuthe (Shankrabharanam); Manasa-guruguha (Anandabhiravi); Ehi-Annapaurne (Punnagavarali); Amba Neelayatakshi (Nilambari), and ,each of the Nava-avarana kritis. These are indeed monumental works.

It is not that all aspects of his music are slow and spacious. He built into his compositions exhilarating bursts of speed and sparkling delight as if in celebration of the divine spirit, towards the end. Certain kritis are interlaced with Madhyamakala-Sahitya, passages in tempo faster than the rest of the kriti (E.g. Mahaganapatim in Nata).

Although the Kritis of Sri Tyagaraja are known for their elaborate Sangathi improvisations, there are some archaic Sangahtis in the Kritis of Sri Dikshitar as well(e.g. in Arunacala-natham in Raga Saranga ; and, Pahimam-ratnachala –nayaka in Raga Mukhari).

Sri Dikshitar redefined the treatment of even the traditional Karnataka Ragas by way of elaborate beginning, rich in Gamakas resembling the sliding Meends as, for instance, in the slow paced majesty of Akshya-linga-Vibho (Shankarabharanam); or in Balagopala (Bhiravi), portraying the beauty of the divine child, Krishna. His Nirajakshi-Kamakshi in Hindolam with Dha flat entirely changed the way Hindolam came to be sung by his contemporaries, as also by the later Carnatic musicians.

It is believed; before the time that Sri Dikshitar went to Varanasi, the Hindola Raga in the Carnatic system was, generally, rendered with Chatusruti-Dhaivata (say, as in the kriti, Manasuloni of Sri Thyagaraja). While Sri Dikshitar was in the North, he had listened to Raga Malkauns (equivalent to Hindola of the South), sung with Shuddha Dhaivata, expanding it freely in all the three octaves. Sri Dikshitar felt such charm and appeal could be brought into the Hindola of the Karnataka-samgita. He thereafter, composed his splendid Nirajakshi-Kamakshi in Hindola with Dha flat, while retaining the purity of the Hindola Raga.

Some say; Sri Thyagaraja’s Kriti Samaja-vara-gamana in Hindola, shows the shades of Sri Dikshitar’s influence. Thais is because, his treatment of Hindola in his earlier Kriti – Manasuloni , was quite different.

*

Sri Dikshitar was well versed in the Alapana-paddhati; and, followed it in the elaboration of a kriti. The musicologists have said “The most outstanding aspect of the compositions of Sri Dikshitar is their richness in Raga-bhava”. His sense of selection of the apt Sancharas of the Raga to bring out the true emotion is remarkable. They range stretching from the Mandra to the Tara-sthayi ; and, give a complete picture of the Raga. It is said that if you sing his kriti in Akara, it can bring out the character of its Raga. His kritis are virtually, Raga-alapana, chiseled to fit in with Taala ; and ,dressed in Sahitya.

[ Please also read Smt. Vidya S Jayaraman’s conversation with Dr.V.V.Srivatsa ]

Structure of kritis

His kritis are well structured, close knit and written in graceful Sanskrit. Sri Dikshitar’s kritis do not usually have more than one Charanam; and, as many as 157 of his creations are Samasti-charanams, carrying no Anupallavi or the Anupallavi itself acting as Charanam. His rhythm is subtle ; and, the lyrics are divine.

Sri Dikshitar’s kritis with Samashti-charanam have enriched the variety of musical forms in Karnataka Samgita. These Kritis composed in Madhyama-kala are highly popular ; e.g.

Since he did not compose multiple Charanas, his single Charranas tended to be quite lengthy ,as compared to the Kritis composed in Pallavi-Anupallavi-Charanam format. Such fairly long Charanas, however, enabled Sri Dikshitar to provide exhaustive information about various deities, shrines, concepts of the Sri Vidya tradition etc. The Madhyama-kala-sahitya that he employed for such Kritis, also helped in introducing some variation in such long Charanas.

[Perhaps his only multiple-charana creations are his Kriti ‘Maye-tvam’ (Tarangini) ; and , his four Ragamalikas]

Each of his compositions is unique, brilliantly crafted and well chiseled work of intricate art. It is incredible how delicately he builds into his tight-knit kritis a wealth of information about the temple, its deity, its architecture and its rituals; and about jyothisha, tantra, mantra, Sri Vidya, Vedanta etc. He also skillfully builds into the lyrics, the name of the Raga (Raga-mudra) and his Mudra, signature.

Sri Dikshitar also built in phrases of Samgita-shastra in the body of the few of his kritis, sometimes giving technical details in precise ways.

For instance; in his Kriti ‘Meenakshi-me-mudam-dehi’ (Purvi-Kalyani), the phrase ‘Dasa-Gamaka-Kriye’ refers to Dasavidha-Gamakas discussed in ancient music-texts.

And, similarly, the phrase ‘Dvisapatati-raganga-raga-modinim’ in the Kriti ‘Sringira-rasa-manjari’ in Rasamanjari Raga (Rasikapriya) refers to the scheme of seventy two Melas.

Language and wordplay

Except for one kriti in Telugu and three Mani-pravala-kritis (Sanskrit+Telugu+Tamil) , all his other compositions are in Sanskrit.

[ The term is said to be made of mani + pravala, meaning a mixture of gems and coral]

Sri Dikshitar is credited with one Chauka-kala-pada-varnam – ‘Rupamu juchi’ (Todi, Ata taala) and a Daru ‘Ni sati‘ (Sriranjani) also in Telugu.

Sri Dikshitar had a good command over Sanskrit; and, had learnt to express through it his ideals and aspirations in pristine poetry. He had the composure of a yogi and the heart of a poet. Sri Dikshitar’s kritis are therefore adorned with poetic imagery, tranquil grace, a certain majesty steeped in devotion.

He had a fascination for Sabda-alankaras, adorning his poetry with beautifully turned phrases ringing sweetly like temple bells; captivating rhymes of Prasa and Anuprasa. He loved the intricate play of words and to coin sweet sounding phrases. Look at the pada lalithya, a grand procession of enchanting phrases :–

- Akalanka darpana kapola vishesha

- Mana matrike maye marakata chaye

- Devi Shakthi beejodbhava matrikarna swaroopini

- And

- Komlakara pallava pada kodanda Rama.

The rhyming and ringing phrases – Shyamalanga- vihanga- sadayapanga-satsanga- are of unparallel beauty.

***

The structures in the compositions of poetry and of a Kriti, as also in the playing of the Mrdanga are said to follow certain rhythmic patterns (Yati-s).

There is, of course, the usual format which follows the uniform length of lines (Sama).

In addition, there are certain varied and improvised patterns of composing and structuring the lines in a Kriti; such as :

(1) broadening or increasing like the flow of a river (Srotovaha);

(2) tapering or decreasing like a cow s tail (Gopuccha);

(3) increasing, then decreasing; broadening towards the middle like the contours of a drum (Mrdanga); and,

(4) first decreasing and then increasing; narrowing towards the middle, as the contours of an hourglass-shaped drum (Damaru).

And, there is also an arrangement that is devoid of any obvious pattern; it could be irregular or rugged (visama). It is rather difficult to define or illustrate such patterns.

Sri Dikshitar who was well versed in Kavya-prayoga, composing poetry, was, obviously familiar with these geometric patterns that were meant to improvise the structure of lines in a stanza.

*

Sri Dikshitar often structured his lyrics in geometric patterns. He enjoyed a childlike delight in employing Yatis (geometric patterns) such as Gopuccha (tapering like the tail of a cow) or it’s opposite, the Sorotovaha (broadening like the flow of a river) for structuring his lyrics. For instance; in his Sri Varalakshmi (Sri) and Maye–Twam-Yahi (Sudha Tarangini) he used the tapering pattern of Gopuccha.

|

Sarasa Pade,

Rasapade,

Sapade,

Pade.

de

|

|

Sarasa Kaye

Rasakaye

Sakaye

Aye

|

In his kriti Tyagarajayoga Vaibhavam (Anandabhairav) , Sri Dikshitar uses both the Yatis : Gopuccha Yati and Srotovaha.

The phrases are: Gopuccha Yati (like a cow’s tail):

Tyagaraja Yoga Vaibhavam

Agaraja Yoga Vaibhavam

Rajayoga Vaibhavam

Yoga Vaibhavam

Vaibhavam

Bhavam

Vam

And Srotovaha Yeti (flowing or expanding like a river )

Sam

Prakasham

Svarupa Prakasham

Tatva svarupa Prakasham

Sakala Tatva svarupa Prakasham

Shivashaktyadi Sakala Tatva svarupa Prakasham

Alamkaras

Sri Dikshitar brings out the beauty of the Raga and the Sahitya, at many places, through the Svarakshara. For instance:

In the Kriti ‘Pancamatanga-mukha-Ganapatina-paripalitoham-Sumukhena-Sri ’Malahari, Rupaka), the Pallavi is set to the Svaras ‘Pa- dha-Ma- pa –dha- pa- ma- ga- ri- sa- pa- dha- Sa’

In the Kriti ‘Sadacalesvaram-bhava-yamham’ (Bhupalam, Adi), the Pallavi has the Svaras ‘sa- Dha- sa- Pa’

*

Sri Dikshitar , at times, used Svara-sahitya i.e., the words matching with the syllables of the notes. For instance; Sadasrita (in Akshayalinga Vibho) could be tuned as Sa-Da-Pa-Ma; and, Pashankushsa-Dharam (in Siddhi Vinayakam) could be tuned as Pa- SA- Ga- RI- Ni- SA.

Muhana Prasa

Rhyming in the first letter of line is called Muhana. One can observe it in the entire Carana of the Kriti Tyagarajaya-namaste (Begada, Rupaka) as follows:

Mukundādi-pūjita-sōmaskanda-mūrtaye / Muchukundādi-bhakta-jana manōratha pūrtaye/ Mukurabhmba pratibimbitha mukha-spurthaye / Munipakṣi mṛga kītādi mukti-pradakīrtaye

Dvitiyakshara Prasa

Rhyming in the second letter of each line is called Dvitiyakshara Prasa. One can observe it in the Carana of the Kriti Tyagarajam-bhajare (Yadukula-kambhoji, Rupaka) as follows

paulōmīṣādi dikpālapūjita gātram / nīlōtpalāmbānukūla tara kalatram / trilōkya guru guha tātam trinetram / sailōkādi kaivalya prada caritram /

Antya Prāsam

Rhyming words at the end of the lines is called as Antya Prasa. One can observe it in the Anupallavi and in the entire part of Carana of the Kriti Ttyagarajo-virajate (Athaṇa, Rupaka) as follows:

Vāgartha mayabhuvana rājo / Hari vānchitārtha prada rājo / Hara śri guru gua ganeṣa rājo /Samsevita rājādi rājo /

Gamakas

A striking feature of his compositions is the Jaaru Gamakas; both the upward and the downward slides: Digu-Jaarua and Ettaru-Jaaru. For instance; in the Kritis Hiranmayim Lakshmim (Lalita); Arunachalanatham (Saranga);Ananda-natana-prakasham (Kedara) and , “Kari-kalabha-mukham’ (Saveri), one can see abundant use of Jaaru Gamakas.

He also uses many Chittasvara patterns like in the Kriti ‘Balambikē’ (Manoranjani), which has Shuddha-Rshabha and Shuddha Gandhara, bringing in the Vakratva: Ri- Ga- Sa-Ri-Ni-Sa-Dha-Sa,’; ‘Sa-Sa-Ri-Ri-Ga-Ri-Ga-Ga-Ri-Ri-Sa’.

Madhyama-Kala- Sahitya

The slow gait of his compositions is often balanced with an ornamentation of Madhyama-kala-Sahitya or Chittasvaras (For instance: Anandeshwarena-samrakṣhitoham– Anandabhairavi -Chapu Taala; and, Soundara-rajamashraye– Brindavanasaranga- Rupaka Taala)

The Madhyama-Kala -Sahitya is one among the many interesting decorative features (Anga) of the Kritis of Sri Dikshitar. It is seen mostly after the Carana; but, in some cases, the Madhyama-Kala section is also in the Anupallavi. It is also seen in both the Anupallavi and in the Carana; but, it rarely is also seen in Pallavi or in all the sections. The tempo of the Madhyama-kala, in all these cases, is double the tempo of the actual Vilamba Kala. There are numerous instances in his Thyagaraja- Vibhakthi –Kritis.

Apart from the Vibakthi group, the Kriti Tyāgarāja-mahādwajārōhanam in Sri Raga has the Madhyama-Kala passages in all its sections – Pallavi, Anupallavi and Carana.

Raga Mudra

Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar set the trend for embedding Raga-mudra, the name of the Raga, in the lyrics. This served the purpose of establishing the Raga of the kriti; and, it also added a novel lyrical beauty. Sometimes the Raga-mudra could be as simple as Brindavana Sarangendra; or Satchidananda Bhiravisham; or Krithika Suddha Dhyanyena.

In the Kriti ‘Panca-Matanga’ (Malahari),the Raga-mudra is woven in the phrase ‘Kali-malaharaṇa-catureṇa’. And, in the Kriti ‘Sri Parvathi- Parameshvarau’ (Bhouli), the Raga-mudra is embedded in the phrase ‘Chithbim –boulila- vigrahau’.

In the Kriti Tygāgaraja-pālayāṣumām (Gauḷa) the Raga-mudra is in the phrase ‘suthārtānga gaulāṅga’. In the Kriti Tyāgarāja-yōgavaibhavam (Anandabhairavi) it is depicted as ‘sacchit-ānanda-bhiravīṣam’. And, in Viravasanta- Tyāgarāja (Vīravasanta) it is in the beginning as ‘Vīravasanta-Tyāgarājamām’.

*

But, at times, he would ingeniously suggest the Raga by hiding it in a complex word, through shlesha, a skillful play on words. For instance, as in:

(Veena+Abheri) to suggest Abheri;

(Panchamukha+arishadvarga_rahita) to suggest Mukhari; and

(Chidbimbou+lilavigrahou) to suggest Bouli

Some of the Ragas have peculiar names and require great skill to blend them into the composition. For example; the Raga names like Paraz, Mahuri and Arabhi are rather unusual; and yet, he successfully binds them into the composition without marring its literary merit . For instance :

“Bhakthajananam athisamiparujumarga darsitam,

Tvamahurisadayo, Samsarabhithyapaham.”

Again there is a Raga with the name ‘Andhali’ which conveys no specific meaning. But in ‘Brihan-nayaki-varadayaki’ through the phrase ‘Andhaliharana-chana-pratapini’ he develops a fine poetic expression out of it: “The fragrance of her shining beauty attracts even blind bees.”

The name of the Raga ‘Varali’ enhances the artistic beauty of the song ‘Mamava-Minakshi’ through the phrase ‘Madhuravani-Varali-veni.’ These are typical of Sri Dikshitar’s poetic excellence and his ability to achieve natural flow of delightful phrases set to sublime music.

Sri Dikshitar also specialized in the use of different Vibhakti (the various cases that delineate a noun) running parallel. A striking example is the first batch of eight krtis he composed in praise of Lord Subrahmanya of Tiruttani.

Sanskrit language employs eight cases (vibhaktis) for the declination of a noun, namely nominative (prathama), accusative (dvitIya), instrumental (tritIya), dative (chaturthi), ablative (panchami), genitive (Shasti), locative (saptami) and vocative (sambhodhana). The eight cases for the noun Guruguha would be: Guruguhah (Guruguho); Guruguham; Guruguhena; Guruguhaya; Guruguhat; Guruguhasya; Guruguhe; and, (hey or Oh..!) Guruguha.

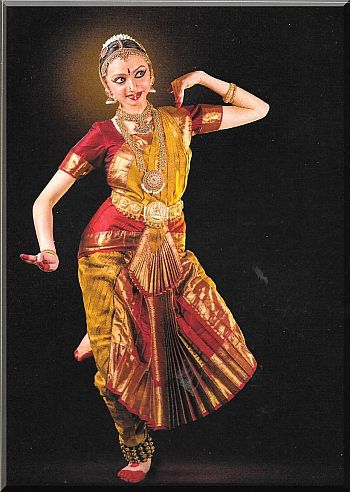

Dance

Many of the Kritis of Sri Mutthuswamy Dikshitar are eminently suited for depiction in Dance form. Just to mention a few: Rupamu-juchi (Todi, Adi Taala); Meenakshime –mudam (Gamaka-kriya, Adi); Chetah-Sri-Bala-Krishnam (Dvijavanthi, Rupaka) Kadambari Priyayai (Mohana, Misra Chapu) and Arunacha-natham (Saranga, Rupaka)

They also present a graphic picture of its principal characters.

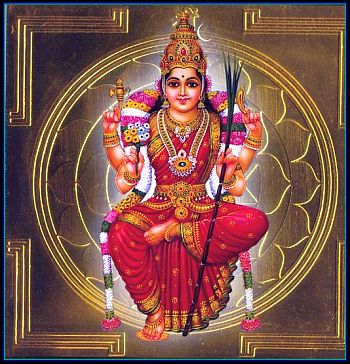

Meenakshime-mudam-dehi-mechakangi-Raja Matangi (Gamaka-kriya, Adi-Taala) is graphic picture of the Mother Goddess Meenakshi. The descriptive lyrics vividly portray the beauty, the grace and the virtues of the Goddess. It offers abundant scope for the Dancer to to meaningfully express through her Abhinaya the various facets of Her beauty , her power and her compassion. And, shades of Srngara are also woven into it by employing the Rati as the Sthayi Bhava; and, Moha, Harsha, Jadata, Mati and Vitarka as Sanchari Bhavas.

Sri Dikshitar weaves a picture of her beauty; with her eyes (Meenakshi, Meena-lochani), her face (vadane-vidambana – vidhu); her arms (mani-valaye); her radiant skin (marakata chaaye); and her waist (shaath-udari), which captivates all (vashankari) ,

Describing virtues and the nobility of Meenakshi, he calls her as: the fountainhead, the Mother of all knowledge (Maana-Matru; Meye); the means of achieving knowledge (Maye); adept in the art of Music (Dasha-kriye); the most compassionate Mother (Hrudaye) who rids one of all bondages (Pasha-mochani).

She verily is the loveliest one who resides in the Kadamba grove (Manini, Kadamba-vana-vasini). She the beloved of Mahadeva-Sundaresha (Mahadeva-Sundaresha-Priye) is the jubilant victorious one (Vijaye).

*

Chetah-Sri-Bala-Krishnam-bhajare (Dvijavanthi, Rupaka Taala) is a delightful word-picture of the most adorable child Krishna. It lovingly describes the beautiful features of the boy Krishna. One might even say, it is a form of meditation.

O mind, worship the child Krishna, the one who grants liberation; and the worship of whose lotus-feet assures fulfilment of all the desired objectives in life.

The child of Nandagopla is resplendent like the rain-bearing cloud; his neck is shapely like a conch; and, he is adorned in yellow glowing robes. The upholder of the Govardhana mountain, the spouse of Rukmini , the one who is the slayer of Putana and other evil-doers, is indeed the incarnation of Purushottama (Vishnu), whose arena of sport is the hearts of sages which are free from passions ,.

The mouth of the Bala Krishna is fragrant with the smell of fresh butter; the soft-spoken one; the one whose eyes are like lotus-petal; the one reclining on a Banyan leaf; the one whose nose is shapely like a Champa flower; the one who is radiant like the flax flower; the one bowed to by Indra and the other seven protectors of the eight directions of the world; the one wearing a deer musk Tilaka on his forehead; the one wearing fresh Tulasi and forest-flower Vanamala garlands; the one encircled by Rishis like Narada; the guardian of the worlds; he indeed is the cowherd extolled by Guruguha.

*

The Kriti Ananda-natana-prakasham, in the Raga Kedara , dedicated to Lord Nataraja of Chidambaram, is another Kriti that is eminently suited for Dance. The Kriti is studded with ‘Sollukattu’ that or Bols , the vocalized syllebles.

*

And, on the occasion of the Arangetram of Kamalam , one of his disciples and also one of the Dasis attached to the temple of Sri Thyagarajaswami at Tiruvarur, Sri Dikshitar composed a Padavarnam on Sri Thyagesha – Rupamu chuchi- in Raga Todi; and, a Daruvarnam – Nin sati Daivamandu ledani– the Raga Sriranjani.

*

Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar’s two Kritis – Kadambari Priyayai and Arunacha natham – do definitely differ from his other well known compositions steeped in Bhakthi and Vairagya Bhavas.

The Kriti Kadambari Priyayai-Kadamba Kananayayi –Namaste –Namaste (Raga Mohana, Misra Chapu Taala) is beautifully suited for an elaboration as a Padam in a Bharatha-natya recital. It brings nature and Srngara Rasa together beautifully. Its Kala -pramana is eminently suited for Abhinaya.

In his other Kriti – Aruaachala-natham-smarami-anisam-apeeta kuchamba-sametam– (Saranga, Rupaka Taala) , which is based in Srngara Rasa, Sri Dikshitar brings out the Nayaka-Nayika-bedha in its fullest expression.

The sheer beauty of this piece lies in the fact the Nayaka-Nayika-bedha is installed within a larger Bhava of Madura-Bhakti, wherein the Jeevatma and Paramatma are in union.

Here in these cases, Srngara should be viewed as an aspect of Madhura Bhakthi; and , should not be taken as something that is improper .

**

Guruguha:

The mudra, the signature for his kritis occurs as Guruguha not only in his classic creations commencing with Srinathadi, but also in this earlier Sanskrit verses grouped under Nottuswara-Sahitya. The term Guruguha means the Guru dwelling in the cave of my heart; and it normally refers to Kartikeya. The term however acquires shades of other meanings depending on the context.

Sri Dikshitar was an Advaitin; and, in that context, the term Guru refers to the Supreme Principle Brahman. In his Sri Guruguha-dasoham he says” I am Guruguha”.

Sri Dakshinamurthy, the yogic incarnation of Shiva, is often referred to by Sri Dikshitar as Guruguha.

Again, in his Jambu-pathe (yaman-kalyan), he refers to Shiva the Guru in nirvikalpa-Samadhi as Guruguha, the attribute-less (nir–vishesha), blemish-less (niranja) supreme consciousness (chaitanya)

– nir-vishesha- chaitanya- niranjana- Guruguha Guroo

Sri Dikshitar was also a yogi. In his Shrinathadi-guruguho-Jayati, the Guruguha is the Lord seated in his Sahasrara-Lotus; and, absorbing the nectar of his sweet music.

In the Shakta tradition, the universe is interplay of Shiva and Shakthi. The Guru is Shiva the body, and Shakthi the energy as Guhya-shakthi, the intrinsic power. Guruguha is at times a wordplay based on this dual principle.

Sri Dikshitar was also a Srividya-Upasaka ;and, as per its tradition ,he submitted his salutations to that Guru-parampara (the linage of his Guru’s). Sri Vidya graduates the evolution from the most subtle form (Shukshma) to the gross in 36 steps; the first being Shiva-tatva , and the final one being Prithvi-tatva.

According to this School, Shiva is Adinatha the progenitor; Shiva is Adi-guru. The Tantric texts identity the Guru and the Mantra with the deity; the three are one. The Mantra represents Manas (mind), the Devata stands for the Prana (vital force); and, the Guru represents the aspirants own self (Atman). That is the reason Sri Dikshitar in his Sri Guruguha-dasoham exclaims : “I am Guruguha”.

In the Sri Vidya tradition, the Guru is not an abstract concept. Guru is an individual. He also symbolizes the hoary tradition Sampradaya in a succession of masters. The human guru is the contemporary master; who has descended in an unbroken line of gurus beginning from Adi Guru Shiva himself. He not only reveals the transcendental reality to the disciple; but also helps him to realize his own essential reality (svartha–parartha-prakatana-paro-guruh). Devotion to the human guru is to purify the mind and fortify it with the spirituality of the Guru. In his Anandeshwara (Anandabhiravi), Sri Dikshitar refers to his Guru , who initiated him, as the incarnation of Guruguha (jnana-pradana- Guruguha-rupa).

Sri Dikshitar refers to the Guru-parampara as Adi- guruguha-varena. He mentions Paramashiva, Durvasa, Agasthya, Hayagreeva and other Gurus of Sri Vidya tradition. Elsewhere, he makes a mention of twelve Upasakas in three Schools of worship in Sri Vidya – Kadi, Hadi and Sadi – in his line Kamadi-dwadasha-bhi rupasthitha-kadi -hadi -sadi-mantra- rupinya-iharena-navanathena-adyena. Shiva is Adi-guru, the Guruguha who resides in the cave of the heart.

Influence of Advaita

Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar was well grounded in Vedanta ; and ,he was an Advaitin. The influence of that School of Vedanta is visible in several of his kritis.

For instance;

In these compositions, he speaks about the identity of jiva and Brahman; the superimposition, Aadhyasa; the seemingly real yet not- real (Maya); the errors in perception, each atom being the microcosm of the universe (chidvilasa koti koti cidabhasa) and other Advaita concepts. In his Kamalamba Navavarana kritis in Shankarabharanam he declares “I am guruguha”.

Influence of Sri Vidya

Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar was a Devi Upasaka; and, was well versed in all aspects of Sri-Vidya-Upasana. His kritis, permeated with Sri Vidya concepts, are too many to be listed here. The prominent among this genre is the Kamalamba-navavarana -kritis, a series that is rich in celebration of the deities and traditions of Sri Chakra worship, expounding in each of its nine kritis, the details of the each Avarana of the Sri Chakra.

According to Sri Dikshitar, Sri Vidya protects the devotee: Bhaktanam Abhayapradam; leads his way to well being ; and, also to the way to liberation (bhukti-mukti-prada-margam) .He sings in inspired devotion; and, beseeches the Divine Mother to protect him ; and, to guide him along the right path.

There are references to Shaktha tradition in his Nilothpalamba-Vibhakthi compositions, the Guruguha Vibhakthi and Abhayamba Vibhakthi compositions, in addition to references in several individual compositions.

Dikshitar composed about 40 kritis spread over four sets of compositions on the subjects related to Sri Vidya; Kamalamba Navavarana (11+2 kritis); Nilothpalamba kritis (9 kritis); Abhayamba kritis (10 kritis) and Guru Kritis (8 kritis).

Of these the Kamalamba set of kritis, is highly well organized; and, is truly remarkable for its classic structure , majesty and erudite knowledge.

Let us talk more about Sri Chakra, Sri Vidya and their influence on Sri Dikshitar, in the next sections.

Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar was a many splendored genius. He gave form and substance to all the 72 Mela-kartha-ragas. Besides, he breathed life into several ancient Ragas that were fading away from common memory. He redefined the paradigm of Karnataka Samgita . Each of his compositions exemplifies the essence of Raga-bhava; and captures the depth and soulfulness of the melody. His vision of the Ragas and their structure is sublime.

His compositions are crisp, well chiseled and rich in knowledge. His Sanskrit is delightfully captivating. His synthesis of Karnataka and Hindustani Music systems is creative and original. He took the best in the other systems and adorned the Carnatic System; enriching both. Dikshitar revolutionized Karnataka classic ethos , while being firmly positioned within its orthodox framework.

He excelled in all the four aspects of the traditional music viz. Raga, Bhava, Taala and Sahitya. The technical sophistication, intellectual brilliance and the majesty of his music is unsurpassed.

Sri Dikshitar was a scholar well grounded in good tradition (sampradaya). To him, music was more than an art; it was serene contemplation; a way of worship in tranquility; and, it was also an outpouring of his soul in celebration of the divine. He described the divine as embodiment of Raga, Bhava and Tala (Bhava-Raga-Taala – swarupakam).

He was a yogi, with the heart of a poet; there is therefore a certain composure and majesty in his music along with sublime poetic imagery adorned by grace and enchanting beauty. His Kritis exude with soulful repose, peace and transcendental joy.

[It is said; the compositions of Sri Thyagaraja reveal, as in a mirror, his personality; his family circumstances; his problems in life; his varying moods; his pains and pleasures; his spiritual yearning; and, his intimate mystic experiences. It seems possible to reconstruct his life-events and personality by piecing together some of his compositions. The same could be said, to a certain extent, in the case of few other musicians, such as: Jayadeva kavi; Kshetrayya; Annamayya; Sri Purandaradas; Sri Shyama Sastri; and others.

(For a comparative study of the compositions of Sri Dikshitar and Sri Thyagaraja , written by the well-known musician-musicologist Prof. S R Janakiraman, please click here and also here)

But, in the case of Sri Dikshitar; his compositions are remarkably free from personal elements. We may admire his scholarship, his mastery over language and music; his superb artistry enriching his creations with beauty and excellence; his dexterity in weaving together and harmoniously synthesizing various strands of elements into precise, compact, faultless Kritis; and, his greatness, in general. But, we do not get to peep into his family circumstances, his personal likes, dislikes, pains and pleasures in his life. He hardly brings into his works, the personal issues or factors; or, his reactions or views on the life around him. There is a sense of detachment; and, Yogic poise that permeates his compositions.

That does not mean that Sri Dikshitar, as a person ceased to be human. Sri Dikshitar was a Jivanmukta, the one who is liberated even while encased in the body. He existed in the real world; but, his moorings and attachments in the phenomenal world had withered away. He rested in himself (Svarupa-pratishta). And, he regarded his Music pursuit as a spiritual quest in search of the most sublime state of consciousness, his identity (sva-svarupa-prapti) with the Mother goddess.]

Continued in Part Five

Sri Chakra and Sri Vidya

Sources:

Compilation of Dishitar’s compositions – Dr. P. P. Narayanswami’s page

Statistical Analysis of Dikshitar’s compositions – Dr. P. P. Narayanaswami’s page

Group Kritis of Dikshitar

List of temples mentioned in his works

Muthuswami Dikshitar – A Creative Genius by Chitravina N Ravikiran

Guru principle and Guruguha in Dikshitar

https://ramsabode.wordpress.com/2008/11/19/lec-dem-the-beauty-of-sangeetham-sahityam-in-muthuswami-dikshitars-compositions/

I gratefully acknowledge the paintings by Sri S Rajam