tinued from Part Two – Overview (2) North – South branches

Part Three (of 22) – Overview (3)

Karnataka samgita

1.1. The Music of South India was referred to as Karnataka Sangita, perhaps, even slightly prior to 12th century. King Nanyadeva, a prince of a later branch of the Rastrakuta (Karnataka) dynasty who reigned in Mithtili (Nepal) between 1097 and 1133 A.D. in his Sarasvathi-hrdaya-alamkara-hara mentions Karnata-pata tanas.

Further, the Kalyana Chalukya King Someshwara III (1127-1139 AD) in his Manasollasa (also called Abhjilashitarta Chintamani) calls the Music of his times as Karnata Sangita . This, perhaps, is the earliest work where the name Karnataka Sangita is specifically mentioned .

Later, Thulaja the Nayak ruler of Tanjavuru in his ‘Sangita saramruta’ (1729 – 1735) calls the Music that was in vogue at his time as Karnataka Samgita. That was, perhaps, because the authorities and the Lakshana-granthas he quoted in his work were authored by Kannada-speaking scholars.

Later, Sri Subbarama Dikshitar in his ‘Sangita-sampradaya-pradarshini’ (1904) refers to Sri Purandaradasa as ‘Karnataka Sangita Pitamaha’ (father of Karnataka Music).

The contributions of the Kannada scholars in terms of – the Lakshna-grathas that articulated the theoretical aspects of the Music; defining the concept of classifying the Ragas under various Mela-s; refining the elements of Music such as Taala; coining fresh Music terms; and, systematizing the teaching methods , particularly in the early stages of learning – had been truly enormous.

Texts

1.2. One of the reasons for naming the Dakshinadi as Karnataka Samgita could be that in the initial stages of its development and even in later times up to the 18th century the texts delineating the Grammar (Lakshana –grantha) of Music were authored mostly by Kannada speaking Music-scholars (Lakshanika). The texts were, however, written in Sanskrit and not in Kannada.

The notable among such texts (Lakshana–grantha) in question, mention could be made of

: – Manasollasa (also called Abhjilashitarta Chintamani ) ascribed to Kalyana Chalukya King Someshwara III (12th century) ;

: – Sangita-Cudamani of Jagadekamalla (1138 to 1150 AD) – son of king Someshwara , author of Manasollasa;

:- Sangita-sara of Sage Sri Vidyaranya (1320 – 1380) which perhaps was the first text to group (Mela ) Ragas according to their parent scale;

: – Sad-raga-chandrodaya of Pundarika Vittala (1583 approx);

:- Kalanidhi of Catura Kallinatha (Ca,1430), a reputed commentary on on Sarangadeva’s Sangita-ratnakara ; he was in the court of Immadi Devaraya ( aka Mallikarjuna) the King of Vijayanagar (1446-65);

: – Swaramela-Kalanidhi by Ramamatya (Ca.1550) a poet-scholar in the court of Vijayanagar ;

: – Sangita Sudha, attributed to Govindacharya (aka. Govinda Dikshita, Ca 1630);

: – Chaturdandi-Prakasika (a landmark text in Karnataka Sangita) by Venkatamakhin, son of Govinda Dikshita (ca. 1635);

: – Sangraha Chudamani by Govindacharya (late 17th – early 18th century), which expanded on Venkatamakhi’s work;

:- and,

the Ragalakshanam ( early 18th century) of Muddu Venkatamakhin (maternal grandson of Venkatamakhin) which makes a drastic shift in the concept of Mela, identifies the Raga by the position of its notes (Svara-sthana) and characterizes a Raga by its Aroha and Avaroha ( ascending and descending notes).

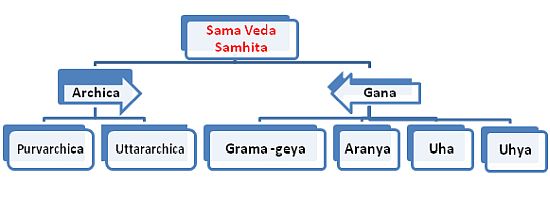

Mela

1.3. The practice of grouping (Mela) the Ragas according to their parent scale, it said, was initiated by Sage Vidyaranya in his Sangita-sara (14th century). Govinda Dikshita (who reverently addresses Sri Vidyarana as: Sri Charana) confirms this in his Sangita-sudha (1614). Sri Vidyaranya classified about 50 Ragas into 15 groups (Mela).

Mela is a Kannada term meaning collection or group; and it is still in use (eg. sammelana – is meeting or conference). Sri Vidyaranya ‘s work on Melakarta system was followed up and improved upon in later times by other Kannada–speaking scholars.

For instance; Ramamatya, following Sri Vidyaranya, in his Svara-mela-kalanidhi classified the then known Ragas into 20 Melas. His classification of Melas was based on five criteria (Lakshana): Amsa (predominant note); Graha (initial note); Nyasa (final note); Shadava (sixth note); and, Audava (pentatonic structure).

Ramamatya was thereafter followed by: Pundarika Vittala (16th century); Venkatamakhin (17th century); and his grandson Muddu Venkatamakhin (18th century).

Taala

1.4. Sri Sripadaraja (1406-1504) who presided over the Matta at Mulbagal in Kolar District, Karnataka, is credited with reorganizing the Taala system from out of the numerous Desi Taalas (rhythmic patterns) that were in use. He categorized the Taala under seven categories (Suladi sapta taala), each with a fixed number of counts: dhruva (14), matya (10), rupaka (6), jampa (10), triputa (7), ata (14), and eka (4). The counts were measured in terms of Laghu (of one matra duration- notionally to utter four short syllables) and Dhruta (half that of Laghu). He also provided scope for extending these counts (virama) by adding a quarter duration of a Laghu.

It appears; two other Taalas (jhompata, a Desi Taala and Raganamatya from folk traditions) were also in use.

Of course, today, the Taala regimen has completely been overhauled.

[ For more on The Suladi Sapta Taalas in Carnatik Music – please click here]

Music Terms

1.5 . Many of the Music-terms that are in use today were derived from Kannada. For instance: while the music-content of a song is called Dhatu, its lyrics are Mathu (meaning spoken word in Kannada). Similarly, the terms Sarale and Janti-varase are derived from Kannada. Sarale is, in fact, said to be the local (prakrta) version of the Sanskrit term Svaravali (string of Svaras). And, Varase (meaning style in Kannada) refers to ways of rendering the Svaras in high (melu-sthayi) and low (taggu-sthayi) pitch.

Further, the terms to denote ten modes of ornamentation (Dasha-vidha-Gamaka) were also said to be derived from Kannada: Hommu; Jaaru; Rave; and Orike etc.

Teaching Methods

1.6. Apart from charting the path for development of Music in South India, the teaching methods were systematized by Sri Purandaradasa through framing a series of graded lessons. Sri Purandaradasa is credited with devising a set of initial lessons starting with Maya-malava-gaula Raga and later in other Ragas. The Svaravalis, Janti varse, the Suladi Sapta taala alankaras and Gitams, composed by Sri Purandaradasa, form a part of Music-learning. He has also to his credit numerous lakshya and lakshna Gitams; Suladis, Ugabhogas, Devara Nama and kirtanas.

His compositions served as a model for Sri Tyagaraja. The other composers of the 18th century also followed the song-format devised by Sri Purandaradasa which coordinated the aspects of Raga, Bhava and Taala.

Contribution of Haridasas

2.1. As regards the Haridasas, their contributions to Karnataka Samgita, spread over six hundred years, have been immense, both in terms of the sheer volume and the varieties of their works.

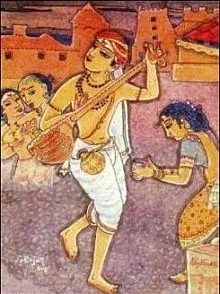

Haridasas were proficient singers and composers; and, spread their message – of devotion, wisdom, ethics in life and social values- through songs and Music. They composed their songs in Kannada, the spoken language of the common people; not in Sanskrit as was the practice until then. Their songs were accessible even to the not-so-literate masses; and, soon became hugely popular.

2.2. The range of Haridasa Music is indeed very wide. It spread from songs derived from folk traditions (lullaby (laali), koluhadu, udayaraga, suvvake, sobane, gundakriya etc) to Prabandha forms (gadya, churnika, dandaka, shukasarita, umatilaka and sudarshana), to musical opera and to the classic poetry.

But, the bulk of the Haridasa songs were in the format of: Pada; Suladi; and, Ugabhoga. When put together, their numbers run into thousands

2.3. As regards the Music, they seemed to have re-organised Ragas starting with malavagaula, malahari under 32 (battisa) Raga-groups.

[Incidentally, it is said, it was Sri Sripadaraya who first mentioned and introduced into Haridasa-music the stringed drone instrument Tamburi (Tanpura). And, later it came to be identified with the Haridasas in Karnataka music.]

Pada

3.1. Sri Naraharithirtha (13th century), a direct disciple of Sri Madhvacharya, was perhaps the first to compose Kannada songs in Pada- format. (His Ankita or Nama-mudra was Raghupathi.) The model he offered was fully developed and expanded by generations of Haridasa composers. That in turn led to evolution of other song-forms in Karnataka Samgita: Kriti, Kirtana, Javali etc.

3.2. Sri Naraharithirtha, after a considerable gap, was followed by Sri Sripadaraja (Ankita: Rangavittala) who lived for almost a hundred years from 1406-1504. He wrote a good number of Padas as also a long poem in Sanskrit (Bramara-geetha). He also introduced many innovations into Karnataka Music.

3.3. The later set of Haridasas, mostly, lived around the Vijayanagar times. The prominent among them was the most honoured Sri Vyasaraya (1447-1539), a disciple of Sri Sripadaraja. He composed many Padas (Ankita: Sri Krishna). He enjoyed the patronage of the Vijayanagar King Sri Krishnadevaraya; and, also had a large following of disciples. During the time of Sri Vyasaraya the Haridasa movement (Daasa-kuta) reached its heights. Sri Purandaradasa and Sri Kanakadasa were prominent members of the Daasa-kuta.

3.4. During the same time, Sri Vadiraja (Ankita: Hayavadana) who had his seat in Sode (North Kanara District) composed varieties of Padas, popular songs and lengthy poems in classic style.

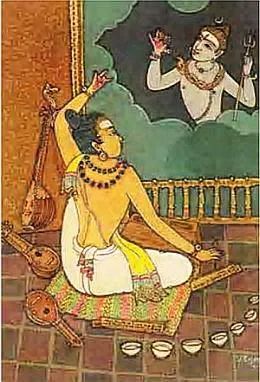

3.5. Among the Daasa-kuta , Sri Purandaradasa (1484-1564) a disciple of Sri Vyasaraya was , of course, the most well known of all. He composed countless Padas (Ankita: Purandara Vittala). Though he is said to have composed gita, thaya, padya-vrata (vrittanama) and prabandha (much of which is lost), he is today known mainly by his Padas, Suladis and Ugabhogas.

His songs cover a range of subjects such as: honesty and purity in ones conduct and thoughts; wholesome family life; social consciousness and ones responsibility to society; philosophical songs; futility of fake rituals; songs preaching importance of devotion and surrender to God; prayers; narrative songs etc.

Sri Purandaradasa systematized the methods of teaching Music; and blended lyrics (Mathu), Music (Dhatuu) and Dance (Nrtya) delightfully. He is credited with introducing early-music lessons such as: sarale (svarali), janti (varase), tala- alankaras as well as the group of songs called pillari gitas. These form the first lessons in learning Karnataka music even today. Sri Purandaradasa was later revered as Karnataka Samgita Pitamaha (father of Karnataka Music).

It is said; Sri Tyagaraja (1767-1847) derived inspiration from Sri Purandaradasa whom he regarded as one among his Gurus. Sri Tyagaraja, in his dance-drama Prahlada Bhakthi Vijayam pays his tribute to Sri Purandaradasa – వెలయు పురందరదాసుని మహిమలను దలచెద మదిలోన్ (I ponder, in my mind, on the greatness of Purandaradasa who shines in a state of ecstasy, always singing the virtues of Lord Hari which rescues from bad fates). Sri Tyagaraja brought into some of his Kritis the thoughts, emotions and concepts of Sri Purandaradasa.

3.6. A contemporary of Sri Purandaradasa was the equally renowned Sri Kanakadasa (1508-1606). He is remarkable for the range and depth of his works (Ankita: Nele-Adikeshava). He, like the other Haridasas, was driven by the urge to bring about reforms in personal and social lives of people around him. He wrote soulful songs full of devotion (Bhakthi), knowledge (jnana) and dispassion (Vairagya), besides composing classic epic-like poetry in chaste Kannada. His Kavyas: Mohana-tarangini (in Sangatya meter); Nalacharitre, Haribhakthisara and Ramadhyana-charite (in Saptapadi meter) are popular even today.

3.7. Following Sri Kanakadasa there were generations of Haridasas who continued to compose Padas, Devara Namas Ugabhoga, Suladi, Vruttanama, Dandaka, Tripadi and Ragale (blank verse) etc as per their tradition. Among them the prominent were : Mahipathidasa(1611-1681) ; Vijayadasa (1682-1755) ; Prasanna Venkatadasa (1680-1752) ; Gopaladasa (1722-1762) ; Helavanakatte Giriyamma (18th century) ; Venugopaladasa (18th century) ; Mohanadasa (1728-1751) ; Krishnadasa (18th century) and Jayesha Vittaladasa (1850-1932).

They all have contributed immensely to the development of Karnataka Samgita. Be bow to them with reverence and gratitude

Pada, Suladi, and, Ugabhoga

4.1. As said earlier; the bulk of Haridasa music can broadly be grouped under three categories: Pada; Suladi; and, Ugabhoga.

4.2. The Padas are structured into Pallavi which gives the gist, followed by Anu-pallavi and Charana (stanzas) which elaborates the substance of the Pallavi. Pada is set to a Raga and a Taala. The Pada-format is closer to that of a Kriti. The term Pada is again derived from Kannada, where it stands for spoken-word or a song.

[Please do read ‘Kannada Suladis of Haridasas’ by Smt Arati Rao ]

4.3. Suladi (some say that it could suggest Sulaba-hadi , the easy way) is a delightfully enterprising graded and a gliding succession of different Taalas (Tala-malika) and Ragas (Raga-malika). Some others say, the name Suladi also means Su-haadi (meaning a good path, in Kannada).

The Suladi is a unique musical form that evolved from the Salaga Suda class of Prabandha . It is made up of 5 to 7 stanzas ; and does not, generally, have Pallavi or Anu-pallavi. Each stanza explains one aspect of the central theme of the song. And, each of its stanzas is set to a different Taala (Taala–malika) chosen from among the nine Suladi Taalas (They in their modern form are: dhruva, mathya, rupaka, jhampa, triputa, atta and eka; in addition to two others jhompata and raganamathya), And, at least five Taalas are to be employed in a Suladi. Occasionally, the folk rhythm Raganmatya Taala is also used.

Therefore, in Suladi, particular attention is paid to the Taala aspect. Sometimes Ragas are not prescribed for rendering a Suladi. Towards the end of the Suladi there is a couplet called Jothe (meaning ‘a pair ‘in Kannada). Some speculate that Jothe might have been a reflection of Yati , an element of Vadya-prabandha that was sung after the Salaga-prabandha.

Mahamahopadyaya Dr. R. Satyanarayana , who has rendered immense service to various field of study such as Music, Dance, Literature and Sri Vidya, explains that the Dhruva Prabandha after which Suladi was patterned employed nine different types of Taalas, while they were sung as a series of separate songs. Thereafter, there came into vogue a practice of treating each song as a stanza or Dhatu (or charana as it is now called) of one lengthy song. And, it was sung as one Prabandha called Suladi. Thus, the Suladi was a Taala-malika, the garland of Taalas or a multi-taala structure.

Mahamahopadyaya Dr. R. Satyanarayana , who has rendered immense service to various field of study such as Music, Dance, Literature and Sri Vidya, explains that the Dhruva Prabandha after which Suladi was patterned employed nine different types of Taalas, while they were sung as a series of separate songs. Thereafter, there came into vogue a practice of treating each song as a stanza or Dhatu (or charana as it is now called) of one lengthy song. And, it was sung as one Prabandha called Suladi. Thus, the Suladi was a Taala-malika, the garland of Taalas or a multi-taala structure.

He mentions that there was also a practice of singing each stanza of a (Suladi) Prabandha in a different Raga. Thus, a Suladi type of Prabandha was a Taala-malika as also a Raga-malika.

Earlier to that, Matanga had mentioned about Chaturanga Prabandha sung in four charanas (stanzas) each set to a different Raga, different Taala , different language (basha) and different metre (Chhandas) . Similarly, another type of Prabandha called Sharabha-lila had eight stanzas each sung in a separate Raga and Taala.

Sarangadeva also mentioned several types of Prabandha-s which were at once Raga- malikas and Taala-malikas such as : Sriranga, Srivilasa, Pancha-bhangi, Panchanana, Umatilaka, and Raga-kadamba.

Thus , the Raga malika, Taala malika and Raga-Taala- malika concept which was described in the old texts was adopted and improved upon by the Haridasa (Sripadaraya, Vyasaraya, Vadiraja, Purandaradasa and others) to produce series of Suladi songs.

4.4. Ugabhoga is a piece of single stanza, sung in a Raga of performer’s choice. They are similar to Vrittams which evolved from the Prabandhas of Desi music. But, they are free from restrictions of meter or the length of the line. Most Ugabhogas don’t have prescribed ragas. It is a form of free rendering where Taala is absent or is not of much importance. Ugabhoga attempts to convey a message in a nutshell. Therefore, rendering of the theme is more important here. Ugabhoga is characterised by the dominance of Raga- ‘Svara Raga Pradhana’.

Some say; the name Uga-bhoga is related to elements (Dhatu) of Prabandha Music, called Udgraha and A-bogha. In the song set in Prabandha format, the element Udgraha consisting a pair of lines grasps (udgrahyate) the substance of poem; and, the element A-bogha completes the poem.

Baliya manege vaamana bandante | BhagIrathage sri Gange bandante |Mucukundage shrI Mukunda bandante | Vidurana manege shrI Krishna bandante | Vibhishanana manege shrI Raama bandante | Ninna naamavu enna naaligeli nindu | Sthalnali srI Purandaravittala ||

As can be seen, there is the opening section (Udgraha) and the last line (Abogha) with the signature (Birudu, Ankita or Mudra) of the composer. The Ugabhoga is not structured into sections.

There is no prescribed Raga; and there is no Taala either. This Ugabhoga was rendered famous by Smt. ML .Vasantha Kumari who sang the first part in Hamsanandi and the rest in Maand

4.5. The Haridasas through their Padas, Ugabhogas, Suladis and Geetas set to attractive Ragas and Taalas carried to the doors of the common people the message of Bhakthi as also of worldly wisdom.

***

Trinity of Music

5.1. The contributions of the celebrated Musical Trinity- Sri Tyagaraja, Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar and Sri Shyama Shastri – are enormous. Their period could doubtless be called the golden age of Karnataka Samgita. Though the three did not meet together, they seemed to have complemented each other wonderfully well. The approach of each was different from the other. And yet; their combined influences has bound the Music of South India into an integrated system and has given it an identity. For instance; of the three, Shyama Shastri seemed to favour tradition, as most of his compositions are in Ragas mentioned in older treatises. Sri Dikshitar was open to influences from the Music of the West (Nottu sahitya) as also that of the North (Drupad music of North India). Some of his compositions in Vilamba-kaala are set in Ragas derived from North Indian Music. Yet; Sri Dikshitar was authentically original; and was also rooted in tradition, following Mela-Ragas classification of Venkatamakhin and that of Muddu Venkatamakhin’s Ragalakshana.

5.2. Sri Tyagaraja seemed to be more innovative. He brought to life some rare Ragas that were long forgotten and had gone out of use. He also created some new ragas. He perfected the Kriti format of Musical compositions that are in vogue today; introduced the practice of Sangathi elaboration of the Pallavi; and built in Svaras into Sahitya. And, he was also a prolific composer, having produced large numbers of Kritis/Kirtanas, Utsava-sampradaya kirtanas, Divya nama samkirtanas and Geya Natakas (dance dramas).

5.3. The post-Trinity period saw an explosion of light musical forms, such as: Varnas, Thillanas, Swarajathis, Jathiswarams, Shabdams and Javali. The composers of these musical pieces were mostly the disciples of the Trinity and their subsequent generation of disciples and their followers.

Today and tomorrow

6.1. As you look back, you find that the Music of India developed and changed, over the centuries, at multiple layers due to multiple influences. The Indian classical music as we know today is the harmonious blending of varieties of musical traditions such as sacred music, art music , folk music and other musical expressions of India’s extended neighbourhood. And, yet the Music of India has a unique characteristic and an identity of its own.

6.2. The Music of India has travelled a long way. The modern day Music scene is markedly different from its earlier Avatar, in its practice and in its attitude. The traditional system of patronage vanished long back. Now, the professional musicians have to earn their livelihood by public performance, recoded discs, radio /TV channels, teaching in schools or at home. The relation between the teacher and student , the ways of teaching as also the attitudes of either teaching or learning have all undergone a sea change; almost a complete departure from the past practices and approaches . New technology and accessories are brought in to enhance the quality and volume of sound output. Many new instruments, starting with violin and Harmonium, are being adopted for rendering traditional music (saxophone, mandolin etc). The styles of rendering the Alap or the song or even selection of Ragas/kritis are all hugely different. Many musicians have been experimenting with fusion music of various sorts. And above all, there is the overbearing influence of film music.

6.3. But, at the same time, I believe the fundamental basics of Indian music are not yet distorted. It is, as ever, growing with change, adapting to varying contexts and environments. This, once again, is a period of exploration and change. It surely is the harbinger of the Music to come in the next decades.

In the coming instalments of the series, we will take a look at the various stages in the evolution of the Music of India, separately, each at a time :the Music of Sama Veda; the Music in Ramayana; Gandharva or Marga Music; the Music of Dhruvas in Natyashastra ; the Desi Music of Ragas; the Prabandhas along with Daru and other forms ; various types of song- formats; the best of all formats – the Kritis also ; and at the end , the Lakshana Granthas composed over the centuries, in a bit more detail.

****

In the next part of the series we shall try to catch a glimpse of the Music of Sama Veda.

Continued in Part Four

Music of Sama Veda

Sources and References

ಕರ್ನಾಟಕ ಸಂಗೀತ’ದಲ್ಲಿ ಕನ್ನಡ’

https://neelanjana.wordpress.com/

Important Treatises on Carnatic Music by Harini Raghavan

http://www.nadasurabhi.org/articles/39-important-treatises-on-carnatic-music

Haridasa s’ contribution towards Music

http://www.dvaita.org/haridasa/overview/hdmusic.html

Kannada Suḷādi-s’ by Arati Rao

https://www.academia.edu/37585064/Kannada_Suladi-s.pdf

All images are from Internet

4.2. The year 1779-80 was a restless and politically uncertain period in the state of Thanjavur. The British East India Company which had been scheming since 1749 to take over the State of Thanjavur finally succeeded. And, in October 1799 the East India Company assumed absolute sovereignty of the State by deposing Raja Serfoji II. The deposed Raja bereft of power and purse was allowed to retain only the capital and a small tract of surrounding villages.

4.2. The year 1779-80 was a restless and politically uncertain period in the state of Thanjavur. The British East India Company which had been scheming since 1749 to take over the State of Thanjavur finally succeeded. And, in October 1799 the East India Company assumed absolute sovereignty of the State by deposing Raja Serfoji II. The deposed Raja bereft of power and purse was allowed to retain only the capital and a small tract of surrounding villages.

S Rajam’s favourite composer is Koteeswara Iyer (January 1870 – October 21, 1936) popularly known as Kavi Kunjara Dasan. “I am deeply interested in Koteeswara Iyer’s compositions” S Rajam said, ” I do not compare any other composer with him, I find great pleasure in singing his compositions”. Koteeswara Iyer was the first composer, after Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar, who composed krithis in all 72 Melakartha-ragas. His monumental work, “kanda ganamudam” has songs, in praise of Lord Muruga, composed in all the 72 Melas. The songs are in chaste Tamil .

S Rajam’s favourite composer is Koteeswara Iyer (January 1870 – October 21, 1936) popularly known as Kavi Kunjara Dasan. “I am deeply interested in Koteeswara Iyer’s compositions” S Rajam said, ” I do not compare any other composer with him, I find great pleasure in singing his compositions”. Koteeswara Iyer was the first composer, after Sri Mutthuswami Dikshitar, who composed krithis in all 72 Melakartha-ragas. His monumental work, “kanda ganamudam” has songs, in praise of Lord Muruga, composed in all the 72 Melas. The songs are in chaste Tamil .