[This is the Tenth article in the series.

This article and its companion posts may be treated as an extension of the series I posted on the Art of Painting in Ancient India .

The present article looks at the not-so-well-known Jain temple of Trailokya-natha-swami (Vardhamana) at Jaina Kanchi. It is one of the few surviving ancient Jain temples in Tamil Nadu.

This article presents the case of an overzealous and yet a wrong way of conserving the ancient murals. The Department of Archaeology of the State Government, in their wisdom, laid a fresh coat of paint over the sixteenth century murals drawn in Vijayanagar style, in order to keep the paintings fresh and bright. The art experts and art historians were shocked and angry; and described the action of the Government Department as thoughtless; and a disaster.

There surely must be a sensible way that falls somewhere between total neglect and overzealous reaction, which either way harms the ancient art-objects.

In the next article we shall look at the traditional mural paintings of Kerala. These 16th-17th century murals painted over the walls in temples and palaces have a unique style of depiction and colour schemes. ]

Continued from the Legacy of Chitrasutra – Ten – Lepakshi

40. Jainism in Tamil Nadu

40.1. It is believed that Jainism entered Southern India in around fourth century BC, when Acharya Bhadrabahuswamin, the last Shrutakevalin (433 BC- 357 BC), along with a body of twelve thousand disciples, started on a grand exodus towards the South; migrated to the Sravanabelagola region, in Karnataka, as he feared a period of twelve years of severe drought was about to hit the North India. The Mauryan emperor, Chandragupta, abdicating his throne in favor of his son Simhasena (according to Jain work Rajavali-Kathe) took Diksha and joined Bhadrabahuswamin on his exodus. As foretold by Bhadrabahuswamin, a terrible famine did brake out in the Northern country.

[ Please also read Studies in South Indian Jainism by Ramaswami Ayyangar, M. S; Seshagiri Rao, B , 1922 ]

Some time after reaching Shravanabelagola, Bhadrabahuswamin felt that his end was approaching; and, he then initiated Visakhamuni into a higher order. The Sruta Kevalin Bhadrabahuswamin , thereafter, entrusted the rest of the disciples to the care of Visakhamuni; and, instructed them all to move further South.

And, soon thereafter, the monk Visakhacharya, at the behest of Acharya Bhadrabahuswamin, moved over to the Chola and Pandya countries along with a group of Sramanas (Jain monks), in order to propagate the faith of the Thirthankaras.

It is said; Visakhamuni, in the course of his wanderings in the Chola and the Pandya countries, worshiped in the Jain Chaityas and preached to the Jains settled in those places. This would suggest that the Jains had already colonized the extreme south even before the Sallekhana of Bhadrabahuswamin, i.e., before 357 B.C.

40.2. Some scholars argue that a sizable number of Sravakas (Jain householders) were already present in the Madurai, Tirunelveli and Pudukottai regions; and , they lent support and care to the emigrant monks.

However, the exact origins of Jainism in Tamil Nadu are unclear.

Some scholars claim that Jain philosophy must have entered South India some time in the sixth century BCE; and, that Jains flourished in Tamil Nadu at least as early as the Sangam period.

According to other scholars, Jainism must have existed in South India, at least, well before the visit of Bhadrabhuswamin and Chandragupta. There are plenty of caves as old as the fourth century found with Jain inscriptions and Jain deities around Madurai, Tiruchirāppaḷḷi, Kanyakumari and Thanjavur.

The ancient Tamil history , culture and literature depict a rich legacy of the Jains

[Some scholars believe that Tholkappiar the author of the celebrated earliest Tamil Grammar Tholkappiam (estimated to be written between the 3rd century BCE and the 5th century CE) was a Jain.

And, Saint-poet, Thiruvalluvar, the author of the celebrated Tirukkurral (dated variously from 300 BCE to 7th century CE), one of the finest collections of couplets on ethics, political and worldly-wisdom, and love, was also a Jain.

Apart from these, the three other major works in Tamil of the ancient times – Silapaddikaram, Civaka Cintamani and Valayapathi – were written by Jain authors.

It is said, that in these texts, in the ancient Tamil regions, the Jain Thirthankaras were addressed as Aruga or Nikkanthan. And, the religion of Jains was called: Arugatha or Samanam. The senior Jain monks were called as ‘Kuruvattikal‘ (Guru), Atikal (Yati), Periyar or ‘Patarar‘ (Tamil form of Bhattara) .

The place where Jain monks lived was called as Aranthaanam and Aravor (Manimekalai. 3:86-112, 5:23); and, as Nikkanthak Kottam (Silappatikaram.9:63). The generous land donations made to the Jain monasteries (Palli) were called Palliccantam ( however, the exact meaning of the term Cantam , is much debated).

The more important cities where the Jains flourished in sizable numbers were said to be: Kaveripoompattinam (also known as Poompuhar or Puhar), Uraiyur, Madurai, Vanchi (also known as Karur or Karuvur) and Kanchi (Kanchipuram).

They all had monasteries (Vihara) which also functioned as schools (Samana palli) run by the Jain monks (the bigger Pallis were called Perumpalli) . Silappatikaram (11:1-9) mentions a Kanthan school and temple at Uraiyur as also in Madurai, the capital of Pandya kingdom.

Even though Manimekalai was a Buddhist, she went to Jain monks at Vengi, the Chera capital; and, learnt about the Jain concepts of morality (Manimekalai 27:167-201). And, Vengi was also the city where lived the celebrated Jain monk Ilango Adigal – the brother of King Cheran Chenguttuvan and the author of Silappatikaram, which is one of the five Epics of Tamil literature.

Sittanavasal Cave (Sit-tan-na-va-yil) – the abode of great saints – is a second -century complex of caves in Pudukottai District of Tamil Nadu. It is a rock-cut monastery that was created by Jain monks. Its name indicates that it was the abode of the Siddha (the monk or monks). It is also called Arivar Koil – the temple of the Arihants.

The first century Tamil-Brahmi inscription, found therein, names the place as ‘Chiru-posil’. It records that Chirupochil Ilayar made the Atitnam (Adhittana, abode or a dwelling place) for Kavuti Itan who was born at Kumuthur in Eorumi-nadu.

[A fairly large number of stone-inscriptions, etched in Tamil-Brahmi , are found in several caves in Tamil Nadu. And, most of such inscriptions are around Madurai , the capital of the Pandyas. The noted scholars like Iravatham Mahadevan and Ramachandran Nagaswamy, have made extensive studies of the early inscriptions. It is explained; the script of the inscriptions are named as ‘Tamil-Brahmi ‘, because it is , basically, Brahmi, but with slight modification to facilitate insertion of Tamil terms. For instance; in these inscriptions, the Prakrit term ‘Gani’ ( leader of a Gana , a group) becomes “Kani’; ‘Acharya’ becomes ‘Acirikar’; names like ‘Nanti’ become ‘Nattai or Nattu’; sacred images Prathima (Patima) be comes ‘tirumenai’; and,’Sranana’ ( a Jain monk) becomes ‘Amanan’.]

The Sittannavasal cave temple belonged to a period when Jainism flourished in Southern India. And, it served as a shelter for Jain monks till about 8th century when Jainism began to fade away in the Tamil region.

Sittannavasal has the distinction of being the only monument where one can find, in one place, Tamil inscriptions dating back from 1st century BC to the 10th century AD. It is virtually a stone library in time Sittanavasal is also renowned for remnants of its rare Jaina mural paintings.

It appears there were Jain Nunneries too. Silappatikaram (10:34-45 ) mentions that when Kovalan and Kannagi went to Madurai, on their way, they secured the blessings from Gownthiyadigal , situated close to Kaveripoompattinam, on the northern bank of the river Kaveri. It is said; Gownthiyadigal was a sort of Jain Nunnery. The Jain nuns, it appears, were variously called as Gownthi; Aariyanganai; Eyakkiyar; or Gurathiyar, the female Guru. It is also said , the Sanskrit term ‘Guru‘ and its plural form ‘ Guruvah‘ became in Tamil ‘kuru‘ and ‘Kuruvar‘. Its polite form was Kuruttiyar or Kuruttikal ]

Some scholars believe that Jainism became dominant in Tamil Nadu in the fifth and sixth century CE, during a period known as the Kalabhra interregnum. And, after the fifth century A.D, Jainism became so very influential and powerful as to even become the state-creed of some of the Pandyan kings.

[ I think , it needs to be mentioned that religious affiliations , say during the fifth century, were rather fluid. For instance, in the Silappadikaram , you find , sometimes, each member of a family followed her/his own favorite religion : Kovalan’s father Masattuvan became a Buddhist; and, Kannagi’s father Manyakan became an Ajivaka. And, while Appar , in the early part of his life, was attracted to Jainism and became a Jain monk , his sister continued to be a staunch devotee of Shiva. Manimekhalai, the daughter of Madhavi, a dancer by profession (Parathiyar), becomes a Buddhist nun. And, Kovalan and kannagi continued , till end, as Nagarathars – the merchant community.

Even as late as in the Eleventh – Twelfth Century, the wife of the Brahmin Chandramouli – a minister in the court of the Court of the Hoysala King Veera Ballala II – Achala Devi (also called Achiyakka) was a devout Jain. She caused the construction of a Jain temple (Basadi), at Shravanabelagola, in 1181 A.D, devoted to the twenty-third Jain Tirthankaras Parshwanath.

It was only when the Bhakthi movement took hold , large numbers of families finally became Vaishnavas or Shaivas. Those that continued to adhere to Jainism were reduced into small and a minor community of Jain laymen – Samaṇar, Nayiṉār (around 0.13% of the population of Tamil Nadu. ]

However, Jainism began to decline around the 8th century A.D., with many Tamil kings embracing Hindu religions, especially Shaivism.

Thus, during the middle half of the seventh and the beginning of the eighth centuries A.D., the Jains sustained a series of reverses both in the Pallava and the Pandya country. The Chola kings did not encourage during this period the Jain religion, as they were devoted to the worship of Shiva

In any case, there is evidence to indicate that Jainism came into existence in Tamil Nadu, at least, by about fourth century BC. Thereafter it took roots in Tamil Nadu and flourished till about sixteenth century when it went into decline, due a combination of reasons. It is estimated there are now about 50,000 Tamil – Jains or Samanar who have a legacy that is more than 2,000 years old; and that most of them are engaged in farming in the North Arcot (Thondai-mandalam) region.

40.3. As regards Kanchipuram, the capital city of the Pallavas and a renowned centre of learning, the Jainism flourished there because of the recognition, acceptance and encouragement it gained from the ruling class, as also from common people. It is said; the Pallava King Mahendra-varman I (600 – 630 CE), in the early part of his life, caused the construction of two temples dedicated to Thirthankaras Vrishabdeva and Vardhamana.

40.4. The Jain scholar-monks such as Acharyas Sumantha-bhadra, Akalanka, Vamana-charya Pushpa-danta, Kunda- kunda and others, were highly regarded for their piety and scholarship. Under their guidance a number of Jain temples and educational institutions (samana-palli) were established in the Tamil country, especially in its Northern regions.

[Palli is a Prakrit term, which by extension came to mean, in the Tamil – Brahmi inscriptions, a Jaina monastery or a temple or a rock shelter where the Jaina monks stayed and studied . Some say that the Tamil term for a school –“palli”- has its origin in the ancient samana-palli of the Jains].

40.5.The recognition accorded to Jainism is evidenced by the fact that a sector of Kanchipuram, along the banks of the Vegavathi , a tributary of the Palar River, was named as Jaina Kanchi. It is now a hamlet (Thiruparuthikundram) on the southwest outskirt of the present-day – Kanchi, a little away from the Pillaiyaar Palayam suburb. Jaina Kanchi does not ordinarily attract many tourists.

40.6. Jaina Kanchi is now of interest mainly because of its two temples: one dedicated to Chandra-prabha the eighth Thirthankara; and the other dedicated to Vardhamana the twenty-fourth Thirthankara who is also addressed as Trailokya-natha-swami. And, the other reason of interest is the ancient paintings in the Vardhamana temple.

The Chandra-prabha temple is the earlier and the smaller of the two. It was constructed during the reign of Parameswaravarman II, the Pallava king who came to throne in 728 AD.

According to Dr. T. N. Ramachandran, the Trailokya-natha-swami temple was built perhaps during the end of the Pallava period; that is, in the eighth-ninth century.

41. Trailokya-natha-swami (Vardhamana)

41.1. The Trailokya-natha-swami temple enjoyed the patronage of Pallava kings as also of Chola emperors Raja-raja chola II (reign ,c.1146–1173) ; Rajendra II (reign , c.1163 – c. 1178 CE) ; Kulottunga I (reign , 1178–1218 CE); and Raja-raja III (reign , c.1216–1246 CE) during whose periods some improvements were made and a front pavilion (mukha mantapa) was added to the sanctum. The Vijayanagar kings too supported this Jain temple.

During the year 1387, Irugappa, a disciple of Jaina-muni Pushpasena; and a minister of Vijayanagar King Harihara Raya II (1377-1404), expanded the temple by adding a larger pavilion- the Sangeetha mantapa.

Later additions were made by Bukka Raya II (in 1387-88) and Krishna Deva Raya (in 1518). It is also said; Krishna Deva Raya made a “land-grant” to the temple.

41.2. The Trailokya-natha, thus, developed into a complex of three shrines: One for Vardhamana and Pushpadanta; the other for Padmaprabha and Vasupujya; and the third for Parshvanatha and Dharma Devi. Each shrine has its own sanctum, ardha-mantapa and mukha-mantapa. The temple is also a repository of a large number of icons.

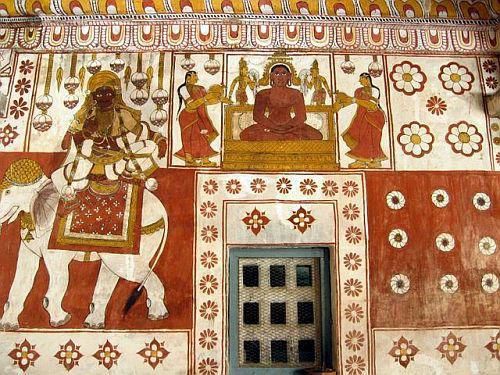

During the 14th and 16th centuries, the ceiling of the sangeetha – mantapa were decorated with beautiful paintings, in Vijayanagar style.

It appears Jainism was active in the Kanchipuram region at least till around the 16th century.

42. The Paintings

Sri Sridhar, T. S.- Former Commissioner of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Tamil Nadu , writes :

The ceiling of the Mukha-Mantapa and the Sangeetha-Mantapa in the Trilokyanatha temple bears a series of colorful paintings which illustrates the life stories of three out of the twenty-four Tirthankaras- Rishabadeva, the first, Neminatha, the twenty second along with his cousin Krishna, and Vardhamana, the twenty fourth. The paintings date back to the 15th century CE.

They are arranged in convenient groups, two running from north to south and two from east to west on the ceiling of the Sangeetha-Mantapa, and one group running from north to south on the ceiling of the Mukha-Mantapa. They are in rows of panels with a narrow band between every two rows for labels in Tamil Grantham explaining the incidents.

The paintings contain the life stories of Rishabadeva, the first Tirthankara, Neminatha, the 22nd Tirthankara, his cousin Krishna and Vardhamana or Mahavira who is the 24th Tirthankara. They depict different facets of the Tirthankaras life from birth to coronation, celebration of monkhood to renunciation and attainment of World Teacher status. The celebrated procession of Vardhamana and his return to the city and anointing ; the rows of animals with the elephant Airavata leading the procession, are beautifully depicted in vivid detail

42.1. The paintings drawn on the ceiling of the Sangeetha-mantapa during the period 14th and 16th centuries were in Vijayanagar style of painting; and they depicted the legends of the Thirthankaras, particularly those of Rishabha Deva and Vardhamana.

42.2. A narrative panel relates the story of Dharmendra, the serpent king, who offered his kingdom to the relatives of Rishabha Deva in exchange for their consent not to disturb the meditation of Rishabha Deva.

42.3. Such narratives were alternated with scenes depicting processions of elephants, horses, soldiers, standard bearers and musicians.

42.4. The sequence of the narratives and the court scenes was broken by depiction of Sama-vasarana the adorable heavenly pavilion where the eligible souls gather to receive divine discourse.

The term Sama-vasarana (Sama + avasarana) means an assembly which provides equal opportunities for all who gather there. Samavasarana, in Jain literature denotes an assembly of Thirthankara. At this assembly different beings – humans, animals and gods – are also present to behold the Thirthankara and hear his discourses. The common assembly, at which different beings are gathered for one purpose, treats all alike overriding the differences that might exist among them. A Sama-vasarana is thus, a tirth, a revered place.

The Sama- vasarana is pictured in a very interesting fashion. Each panel is depicted with eight concentric rings having miniature figures, trees and shrines painted along their periphery. A Thirthankara is enshrined at the core of the Samava-sarana theme.

42.5. There are a few panels that resemble the Krishna- Leela, the legends of Krishna. But, they in fact, depict life events of Neminatha, the twenty-second Jain Tirthankara. According to Jaina lore, Neminatha was the cousin of Krishna of Srimad Bhagavatha; and he is Krishna’s counterpart in the Jain tradition.

[Please also see ‘ The Paintings of Vijayanagar Empire’ by Dr.Rekha Pande]

43. The other side of bad maintenance

43.1. The pictures posted above are not as they were painted by the artists of the 14th and 16th centuries.

A few years back, the State Archaeological Department of Tamil Nadu repainted the 14th-16th century murals on the ceilings of the Trailokya-natha-swami temple. A fresh coat of paint was laid over the old murals. The repainting was done allegedly by untrained artists, who were not familiar with the techniques of conservation or restoration of ancient murals. As a result, the murals now dazzle in bright colors.

Sri Sridhar, T. S – Former Commissioner of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Tamil Nadu , writes in his article Conservation of Murals in Thirupparuttikundram temples of Jina Kanchi

Before proceeding with conservation of paintings in Trilokyanatha temple, we studied carefully the base on which they were etched. The granite roof had a thin layer of lime plaster on which the paintings were done, depicting the life stories of the three Tirthankaras. After studying the history of the paintings, which date to the15th Century, we also looked at the condition of the paintings. At the time of taking up conservation we found that the murals were intact in some places, but most of them were in a state of considerable damage. The colours had changed, the lime mortar had peeled off in many places, the plaster had fallen off and the labels were unclear in parts.

Overall, the condition of the murals was such that they required extensive conservation work. Accordingly, experts were consulted and it was finally decided to bring in a team from Karnataka. Since there are not many who are trained in Mural conservation it was found necessary to get the expert team from a neighboring state.

Next, we looked at the materials used for the paintings. Lime mortar was the base material; the colours were provided by the use of varied materials matching with the original paintings. For example, herbs like ‘Shank Pushpam’, ‘Neela Amary’ and green leaves to produce green; ‘Manja Kadambai’ for yellow; ‘Red Sandstone’ and ‘Lacquor Bee’ and ‘Wax’ for red; and, black color from burnt lamp waste etc., were used to derive different colours. A mixture of these ingredients was also applied to derive different shades of the above colours.

On studying the condition of the murals, and after detailed discussion with experts, we identified the several areas for restoration. The outside of the paintings was checked for cracks or lack of adhesion due to water accumulation or formation of bird nests. These were arrested and the conservation began. Cracks and fissures in the painted plaster was fixed to the support base by adhesives like Plaster of Paris, Fevicol or PVA solution mixed in Toluene. Wherever there was a bulge, a hole was made in the bulging plaster, and adhesive solution injected into the hole and kept pressed for some time. Later, the holes were filled with plaster of Paris mixed with suitable colors to match the base paintings

The entire mural conservation effort took nearly six months to complete; but it was well worth the trouble. The finished paintings looked stunningly beautiful and added considerably to the footfalls in subsequent months. On the whole, it was a very challenging, yet, satisfying experience.

****

The pictures you just saw were those of the “re-painted” art works.

43.2. The art experts and art historians were aghast, pained and angry at the thoughtless action, in violation of conservation norms, by the very Department that was entrusted with the task of protecting and maintaining the ancient murals.

Dr. David Schulman, an Indologist, (currently the Professor, Department of Indian, Iranian, and Armenian Studies, Hebrew University, Jerusalem) who has studied mural paintings of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, said “The paintings of the Trilokyanatha temple at Tiruparuttikunram have been ruined by over- painting. This is quite a common thing in Tamil Nadu. If you repaint it instead of conserving it, the subtlety will be lost; the old colors will be lost. This is disaster. These paintings have to be preserved as they were at their height. The way people do it in Europe.”

The other experts too remarked that repainted murals resemble neither the Vijayanagar style nor the present style.

K.T. Gandhirajan, who has studied murals in 35 temples in Tamil Nadu over a period of six years, said “Only experts can do that. The State government should give up repainting the faded murals because there are not enough trained artists to do the work. Instead, it can use the resources to conserve them.”

43.3. At an international seminar titled “Painting Narratives: Mural Painting Traditions in the 13th-19th centuries”, held near Chennai during Jan, 2008, the participating experts expressed their shock and disappointment at the state of conservation of ancient art in India.

According to the experts, the ancient paintings in India are threatened with destruction through negligence and desecration both by the public and, unfortunately, by the very persons entrusted with the task of preserving them. To cite an example , in a major “renovation “ exercise at the Meenakshi temple of Madurai an important series of Nayak murals from the 16th century were covered with cement paint. The ancient paintings are lost forever.

The mural paintings of Tamil Nadu have a long, rich and continuous tradition, ranging from the Pallava period to the Nayaka period. It was during the Vijayanagar and Nayaka periods that the art of painting in temples in Tamil Nadu flourished. Most of the murals in the State belong to the Vijayanagar and Nayaka periods. A few belong to the Maratha period of the 18th century.

Even in the temples where a few murals have survived, they have been whitewashed. In some cases, ignorance led to the neglect of the works of art. In many other cases, soot from oil lamps settled over the murals; electrical cables and switchboards were installed over them; or nothing was done to prevent cracked ceilings and sunlight endangering the murals.

44. And, now…

44.1. I have tried to present in this post the other side of the bad conservation. There are countless cases where the ancient art works are ruined because of neglect or wilful harm. There are also cases, as in Jaina Kanchi, where either by ignorance or by over enthusiasm, the authenticity of the ancient works is degraded. Between these extremes, somewhere, there surely must be a sensible way of taking care of our heritage. As Dr. Schulman remarked, “These paintings have to be preserved as they were at their height. The way people do it in Europe”.

44.2. These mural paintings are not mere bunch of drawings; they are the repositories of our art, culture, history and heritage; they are a part of our very being. It is essential that the general public in India and also the trustees of our art works are educated of the value of our heritage and their historical importance.

44.3. Doubtless, there are problems in taking care of our ancient wall paintings, for want of proper conservation facilities; dearth of trained and qualified conservators; paucity of resources etc. But what is more worrying is the absence of a plan or policy in place; and lack of a perspective vision to conserve even those wall paintings that are under the care and custody of the governments.

44.4. It is a task, which the government alone cannot handle well; several institutions, Universities as also traditional artists need to take part in this endeavour. I wish we had a sort of National Project for Conservation of Wall Paintings, which would comprehensively address the issues of research, training, creating special curriculums in art-schools, and mobilization of various sorts of resources; and above all an effective management and monitoring system.

Next

The traditional mural paintings of Kerala

References and sources

Tiruparuttikunram and its Temples.–By T. N. Ramachandran, M.A

Bulletin of the Madras Government Museum,

Printed by the Superintendent, Government Press, Madras.

http://www.ias.ac.in/jarch/currsci/3/00000187.pdf

http://spicyflavours.net/index.php?autocom=blog&blogid=5&showentry=95

http://www.india9.com/i9show/Tirupparuttikunram-25644.htm

http://www.tnarch.gov.in/cons/temple/temple5.htm

http://www.geocities.com/tamiljain/spread.html

Seminar proceedings

http://www.muralpaintingtraditionsinindia.com/Seminar%20proceedings.htm

Jainism in south India by T. K. Tukol

www.ibiblio.org/jainism/database/ARTICLE/south.doc

Recent discoveries of Jaina cave inscriptions in Tamilnadu by Iravatham Mahadevan

http://jainsamaj.org/literature/recent-171104.htm

Ravaged murals

http://www.hinduonnet.com/fline/fl2516/stories/20080815251606400.htm

Conservation problems of mural paintings in living temples by S. Subbaraman

http://www.muralpaintingtraditionsinindia.com/S%20Subbaraman.htm

Overview of the conservation status of mural paintings in India

http://www.muralpaintingtraditionsinindia.com/op%20agarwal.htm

All pictures are from Internet

Ruchika

August 4, 2014 at 6:07 am

Dear sir,

I am an artist and I am current planning to work on a new project about Jainism in tamil nadu.I found your information and article about the same really amazing and resourceful . Since I live in Mumbai and I am unable to visit the temple, I would like to know if you have any idea if the temple still exists and If the paintings on the wall are still the same.

Please get back to me on the same, Awaiting your reply.

Thank and Regards,

Ruchika Jain

sreenivasaraos

August 4, 2014 at 12:05 pm

Dear Ruchika

Thanks for breathing life into an old and a forgotten blog.

1. Yes; these Jain temples of 5-6th century decorated with murals later in the centuries do exist. They are located at a village near Kanchipuram. The name of the village is Tirupparuthikkundram (Pronounced: Tiru-paruthi-kundram) situated on the banks of a minor river the Palar. These temples are presently under the charge of the Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department.

Sadly; the temples are not a part of the popular tourist circuit. They are visited mostly by scholars who intend to study the murals. As I understand; the exteriors of the temples are in a rather bad shape. However, thanks to the efforts of some dedicated iJain families in the neighbourhood of the temples , the interior of the temple is fairly well maintained; and, the deities inside the temple are well preserved and worshipped.

Please check the following YouTube presentation of the murals on the walls and on the ceilings.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l9Mom2ILDKc

Please also check the following links for some more details of the temples and the associated poetry

http://www.herenow4u.net/index.php?id=76592

http://www.hindupedia.com/en/Kanchipuram

2. Please also check my blog on the murals at Sittanvasal

https://sreenivasaraos.com/tag/lotus-in-jain-paintings/

3. As regards Jainism in Tamil Nadu; please check

http://www.tamiljains.org/

and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tamil_Jain

and follow them up

Please keep talking.

Regards

[Incidentally, Jainism is a vibrant and living religion in parts of Karnataka – say , in the districts of Hassan, Chickmagalur and in border areas of Belgaum district. Jainism is particularly strong in in the South Kanara district. The third century huge monolithic statue of Gommata at Sravanabelagola is world renown. There similar statues of standing Bahubali at Venur and Karkala in South Kanara. All the related Jain temples are in active worship. The followers of this religion are entirely local people who have been its adherents over the centuries. Jainism is very much a local religion rotted in its soil; and , is not an implant.]

Ruchika jain

August 6, 2014 at 7:55 am

Dear sir,

I am so glad that you have replied. Thank you so much for The informations and details that you have provided , they are going to be very helpful for me. I am currently studying mural in jj school of arts Mumbai (post graduate).I am in my final year so I have decided to work on Jain Temple Tirupparuthikundram Kancheepuram for my final project. I would love to have your support for the same. I need to write a thesis on this so I would like to know a few more additional details :

1. I have read in many articles and blogs that the paintings in the temple were recently re painted , is it that they were re painted to the original work before or any modifications have been made on them. Is the originality still there ?

2. Further I shall be going to kanceepuram in the month September. You had mentioned earlier that the temples can be visited only by scholars who intend to study murals and not by tourists so if I go down to kanchi will I need any pre permission from TNAD. If yes, do you have any idea how do i approach them. Basically can I visit the temple for studying it..?

I am a growing artist and this project is one of my first big works, so it would be a great pleasure if you can please stay in touch and provide me your expertise knowledge in this field.

Thanks and regards,

Ruchika Jain

Ruchika

August 19, 2014 at 9:38 am

Dear sir,

I am so glad that you have replied. Thank you so much for The informations and details that you have provided , they are going to be very helpful for me. I am currently studying mural in jj school of arts Mumbai (post graduate).I am in my final year so I have decided to work on Jain Temple Tirupparuthikundram Kancheepuram for my final project. I would love to have your support for the same. I need to write a thesis on this so I would like to know a few more additional details :

1. I have read in many articles and blogs that the paintings in the temple were recently re painted , is it that they were re painted to the original work before or any modifications have been made on them. Is the originality still there ?

2. Further I shall be going to kanceepuram in the month September. You had mentioned earlier that the temples can be visited only by scholars who intend to study murals and not by tourists so if I go down to kanchi will I need any pre permission from TNAD. If yes, do you have any idea how do i approach them. Basically can I visit the temple for studying it..?

I am a growing artist and this project is one of my first big works, so it would be a great pleasure if you can please stay in touch and provide me your expertise knowledge in this field.

Awaiting your reply.

Thanks and regards,

Ruchika Jain

sreenivasaraos

August 20, 2014 at 10:41 am

Dear Ruchika

1.Please see para in the blog on restoration efforts

2.Please also check all the links provided at the bottom of the blog and my responsive to you.

3.Temple is open to public. But , not many tourists visit it

4.There are caretaker families residing near the temple (I read of Smt Padmavathi , am not sure)

Please make inquiries

5. If there are specific questions over which I can help , I surely will do

6.Please keep in touch

God Bless you

Warm Regards

sreenivasaraos

August 20, 2014 at 10:45 am

Please also see Jainism in South India by Justice TK Tukol

check Google

sreenivasaraos

March 19, 2015 at 8:00 pm

Thanks for the information… but i could not follow the comment

“k.t. gandhirajan, who has studied murals in 35 temples in tamil nadu over a period of six years, said “only experts can do that. the state government should give up repainting the faded murals because there are not enough trained artists to do the work. instead, it can use the resources to conserve them.”

43.3. at an international seminar titled “painting narratives: mural painting traditions in the 13th-19th centuries”, held near chennai during jan, 2008, the participating experts expressed their shock and disappointment at the state of conservation of ancient art in india.”

we are inefficient descendants of expert artists – does this reflect subversions from encroaching races by which people were forced to show no interest…

uno should spend money to preserve indian ancient heritage rather than squandering money on rich countries who already have power to preserve/conserve with their own money.

partiality will stub knowledge…

ether

sreenivasaraos

March 19, 2015 at 8:00 pm

dear ether, thank you. the experts were angry because the repainting was done by untrained artists, who were not familiar with the techniques of conservation or restoration of ancient murals. the desired the government to arrange for training the artists in restoration and conservation works.

as regards uno, it participates in conservation of only those recognized as unesco heritage sites or monuments. the unesco has its own set of norms. further, as dr. o.p. agrawal, director-general, intach (indian national trust for art and cultural heritage) said, “our country is full of wall paintings. in every state, there are hundreds of [wall] paintings, which are not so well known,” but, neither the intach nor the governments has an inventory of those murals. they have to necessarily do their home work, make attempts to preserve whatever that has survived, before approaching uno or unesco or any other external organization. in the current state of affairs, the ancient murals take the least priority. therefore, as shri dsampath remarked, the next generation might get to see these old things only through photographs, i fear.

wish you and your family a very happy and prosperous new year.

with best wishes and warm regards

sreenivasaraos

March 19, 2015 at 8:02 pm

here is a saying in tamil

does a donkey know the wonderful smell of camphor..?

i am sure eventually murals of the old will live on photographs tha have been taken..

wish you a happy and prosperous new year..

DSampath

sreenivasaraos

March 19, 2015 at 8:02 pm

dear shri sampath, thank you. your prediction might true eventually; i fear.

wish you and your family a very happy and prosperous new year.

with best wishes and warm regards