The following is the second part of the article Rig Veda – Position of women (1/2)posted on Oct, 09 2007. The first part dealt comprehensively with the position of women in the Rig Vedic period; and , also discussed a comment posted on an earlier post. It was considered, that instead of imposing a later day’s priorities and prejudices on a society of a bygone era, it would be apt to take a holistic and an independent look and examine from the angles of (a) fair and equitable treatment of women ; and , (b) empowerment of women in the Vedic society.

Part one concluded that the social life portrayed in Rig Veda reveals a tolerant and moderately unbiased society characterized by the sanctity of the institution of marriage; domestic purity; patriarchal system; equitable position in the society for men and women and high honor for women. The women did receive a fair and an equitable treatment ; and, they were empowered to deal with issues that mattered in the life around them.

The second part discusses the views of the Rig Veda on certain specific issues such as the status of the girl child; her education; her marriage; married life’ her right to property; widowhood ; and, remarriage.

Read on..

Girl child

Many hymns in Rig Veda do express the desire to beget heroic sons. There are no similar prayers wishing for a girl child. This perhaps reflected the anxiety of a society that needed a larger number of male warriors to ensure its survival. Sons were preferred to daughters; yet, once a daughter was born, she was raised with tender care, affection and love.

For instance; Ushas’s mother decorated her daughter with much love and care; made her look Radiant like a little bride; before she took the girl out on a stroll.

su-saṅkāśā | mātṛmṛṣṭāiva | yoṣā | āviḥ | tanvam | kṛṇuṣe | dṛśe | kam | bhadrā | tvam | Uṣaḥ | vi-taram | vi | uccha | na | tat | te | anyāḥ | Uṣasaḥ | naśanta / RV.1.123.11/

In the Rig-Veda, there is no instance where the birth of a girl was considered inauspicious. The celebrations and others samskaras were conducted with enthusiasm. In a particular case, the twin daughters were compared to heaven and earth. The daughters were not unpopular. They were allowed Vedic studies; and , were entitled to offer sacrifice to gods. The son was not absolutely necessary for this purpose.

There is a reference to the birth of an only daughter, who was assigned the legal position of a son; she could perform funeral rites of her father; and, she could also inherit the property. It indicates that the position of a girl in Rig Vedic times was not as low as it was to become in medieval times. (Shakuntala Rao Shastri, Women in the Vedic Age– : Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1954).

Kerry Brown in her book ‘Essential Teachings of Hinduism’ explains: “In ancient India a woman was looked after not because she is inferior or incapable; but, on the contrary, because she is treasured. She is the pride and power of the society. Just as the crown jewels should not be left unguarded, neither should a woman be left unprotected. If there are costly jewels, we do not throw them here and there like brass vessels. Costly material is protected”.

Education

Education was an important feature in the upbringing of a girl child. Education was considered essential for girls and was therefore customary for girls to receive education. The girls with education were regarded highly.

The Vedic literature praises a scholarly daughter and says: “A girl also should be brought up and educated with great effort and care” (Mahanirvana Tantra). The importance of a girl’s education is stressed in the Atharva Veda which states,” The success of woman in her married life depends upon her proper training during the BrahmaCharya (student period)”

The Rigvedic Society recognized the power of knowledge; and, prepared their women to face the life in most of its aspects. They taught them Music, Dancing and art of self-defense, apart from the traditional learning.

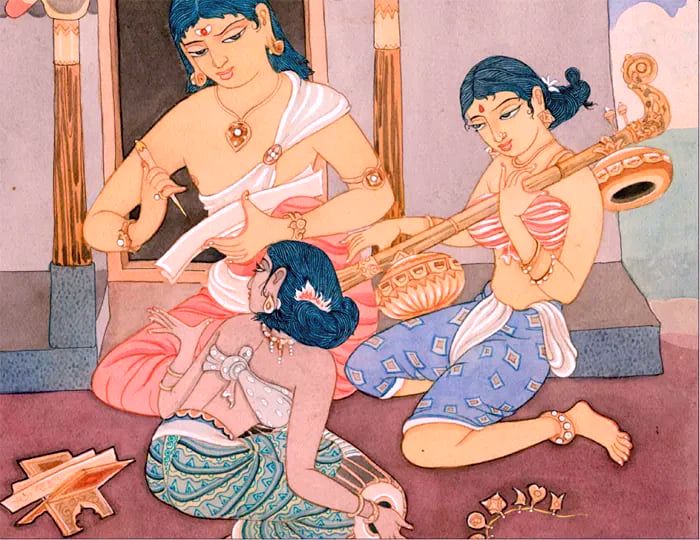

Family by Sri S Rajam

According to Prof. A.S. Altekar (Education in Ancient India; Published by Nand Kishor & Brothers, Benaras – 1944), since the Upanayana ceremony was linked to the commencement of education, the Upanayana of girls was as common as that of boys. The girls were entitled to Upanayana (to receive sacred thread); and, to the privilege of studying Vedas, just as the boys.

The Atharvaveda (XI. 5. 18) expressly refers to maidens undergoing the Brahmacharya discipline; and, the Sutra works of the 5th century B. C. supply interesting details in its connection. Even Manu includes Upanayana among the sanskaras (rituals) obligatory for girls (II. 66).

brahmacaryeṇa kanyā yuvānaṃ vindate patim | anaḍvān brahmacaryeṇāśvo ghāsaṃ jigīṣati ||AVŚ_11,5[7].18||

amantrikā tu kāryeyaṃ strīṇām āvṛd aśeṣataḥ / saṃskārārthaṃ śarīrasya yathākālaṃ yathākramam // Mn_2.66 //

Women performed religious rites after completing their education under a Guru. They were entitled to offer sacrifices to gods. The son was not absolutely necessary for this purpose.

There is ample and convincing evidence to show that women were regarded as perfectly eligible for the privilege of studying the Vedic literature and performing the sacrifices enjoined in it. The Rigveda contains hymns composed by twenty different poetesses, such as: Visvavara, Sikata Nivavarl, Ghosha, Romasa, Lopamudra, Apala and Urvasi.

For instance; Ghosa (Rv. 1-117; X-39-40); Lopamudra (Rv.1.179); Mamata (Rv. VI-10-2); Apala (Rv. VIII-91); Surya (RV.X-85); Indrani (Rv. X-86); Saci (Rv. X-24), Sarparajni (Rv. X-88) and Visvavara (Rv.V-28)

The woman seer Visvavara not only composed mantras, but also performed the functions of a Rtvik (priest) at a sacrifice. Another seer Apala composed a hymn in honor of Indra, and offered to him Soma-juice herself.

Even later in her life, a man could perform the Vedic sacrifices only if he had his wife by his side. According to Shrauta and Grihya Sutras, women chanted mantras along with their husbands while performing rituals. And, the housewife was expected to offer oblations in the household (grihya) fire unaided by the husband, normally in the evening and sometimes in the morning also. In the Srattararohana ritual of the Agrahayaga ceremony, the wife used to recite a number of Vedic hymns ; and , the harvest sacrifices could be performed by women alone, ‘because such was the long-standing custom’.

Women sometimes used to accompany their husbands in the battles against their rivals. the warrior queen Vispala, the wife of the king Khela, had lost her leg in a war; and in which place an iron (ayasi) one was implanted by the Asvins. And, thereafter , she continued to fight on.

yu̱vaṁ dhe̱nuṁ śa̱yave̍ nādhi̱tāyāpi̍nvatam aśvinā pū̱rvyāya̍ |

amu̍ñcata̱ṁ varti̍kā̱m aṁha̍so̱ niḥ prati̱ jaṅghā̍ṁ vi̱śpalā̍yā adhattam || RV_1,118.08

Mudgalani or Indrasena, wife of the sage Mudgala helped her husband in the pursuit of robbers who had stolen their cows; drove the chariot for her husband when he was put in a tight corner. Further, Nalyani Indrasena taking up husband’s bow and arrow, fought the robbers; defeated them; recovered and brought home her herd of cows.

ut sma vāto vahati vāso ‘syā adhirathaṃ yad ajayat sahasram | rathīr abhūn Mudgalānī gaviṣṭau bhare kṛtaṃ vy aced Indrasenā ||R.V.10.102.2||

There were eminent women in the field of learning and scholarship. These highly intelligent and greatly learned women, who chose the path of Vedic studies and, lived the ideal life of spirituality were called Brahmavadinis. And the women who opted out of education for married life were called ‘Sadyovadhus’. Co-education seems to have existed in this period; and, both the sexes got equal attention from the teacher.

As many as about thirty Brahmavadins of great intellect and spiritual attainment are immortalized in the Rig Veda and are credited with hymns. They participated in philosophical debates with men and were highly respected. To name a few of those significant women rishis (rishikā) who figure in the Rig Veda Samhitā: Goshā Kakshivati, Lopamudra, Romasha, Sarama Devasuni , Yami Vaivasvathi , Rathir Bharadwaja , Apala, Paulomi and others. Needless to say, they were held in high esteem for their work to be included in the important religious text of the era.

[ Dr. Rukmani Trichur (Distinguished Emeritus Professor, Concordia University) in her paper ‘Empowerment of Women Based on Sanskrit Texts’, while on the subject of Brahmavadini-s writes:

Gargi, as a learned woman, could have remained content as a composer of hymns like the 27 Risikas mentioned as composers of hymns. But, Gargi is not content with the ordinary, and is looking for answers to fundamental questions. Gargi can be called an extraordinary Brahmavadinī.

The term Brahmavadinī looks as though it was applied to both the composer of hymns, as one can surmise from the Brhad-devata, classifying Risikas like Lopamudra, Romasa and so on as Brahmavadinī s, as also to those who chose to remain unmarried, pursuing a life of learning, to which category Gargi would belong.

Harti-Smrti (ca 6thBCE) classifies women as being of two kinds i.e., Brahmavadinī and Sadyovadhū. It is generally understood that the term Brahmavadini implies a Kumari, who is unmarried. And, even in case a Brahmavadini was married, she could yet choose to continue to lead a life devoted to study; and, that would again indicate her exercising her own choice. Similarly, when Maitreyi opts for being educated in the Upanishad lore, she is exercising her choice; and, there is no indication whatsoever that Yajñavalkya tried to dissuade her from her decision.

Thus, Brahmavadinī is a woman of learning; whether within or outside of marriage. She is one who can make up her mind and can speak with confidence in an assembly of scholars; just as Gargi questioned even the learned Yajñavalkya.

The image of the Brahmavadinī was a powerful one, which exerted perpetual influence; and, it never faded away from the cultural memory. Thus, even when male offspring are prized, the Brhadaraṇyaka Upanishad does not forget to remind us that there is a mantra , which can ensure the birth of a pandita or learned daughter (6.4.17).

In the Grhya-sūtras of Asvalayana and Sankyayana, three Brahmavadini-s: Gargi Vachaknavi; Vadava Pratitheyi; and, Sulabha Maitreyi are celebrated.

It is generally acknowledged that the Vedic period was not unfair to women; and, therefore, the achievements of the Risikas and Brahmavadini-s need not surprise us.

The subsequent period of subjugation of women and her low educational status would naturally lead to her lack of agency. But again, that is not entirely true, for women continued to exercise their choice in adopting a life of learning, in times that were not so favorable

Panini’s Astadhyayi and the subsequent grammatical literature provide evidence of women who were Acharyaa-s and Upadhyayi-s. Bhattoji Dikshita in his Varittika on Panini’s Astadhyayi explains these terms as referring to those ladies who themselves were teachers (yatu svayameva upadhyayika).

While Panini refers to women belonging to Vedic Shakas, cites the instance of Kathi as being a student of Katha-shakha (PA 4.1.53). The Amara-kosha, the Sanskrit Dictionary, also makes a distinction between the female -teachers and the wives of male -teachers.]

Incidentally, let me mention that, later, the Shatapatha Brahmana lists some 52 generations of teachers, of which some 42 are remembered through their mothers. The teachers were males. This list acts like a bridge between the end of the Rig-Veda time and the Shatapatha Braahmana time. It is remarkable that a patriarchal society should remember its teachers through their mothers. The preference over the names of their fathers indicates the important position of women as mothers in Vedic society. Their mothers were considered that valuable, as their sons were recognized through their names.

http://www.surichat.nl/forum/index.php?topic=14696.65;wap2

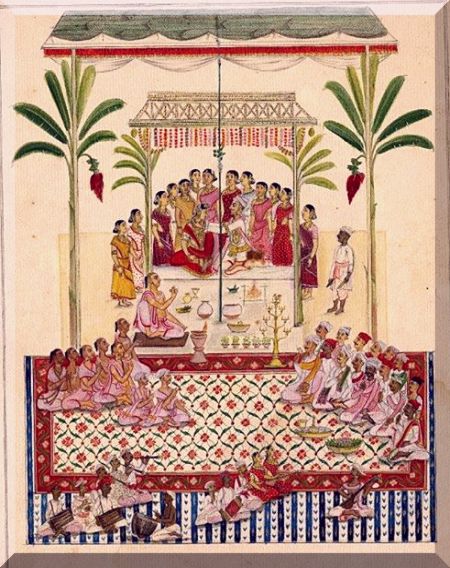

Marriage

There is very little evidence of child (or infant) marriage in the Rig Veda. A girl was married at 16 or more years of age, when her physical development was complete. Marriage was solemnized soon after wedding ceremony. The Vedic rituals presuppose that the married pair was grown up enough to be lovers, man and wife, and parents of children (marriage hymn). These go to show that a girl was married after she attained puberty. Surya, the daughter of Surya (the Sun), was married to Soma (the Moon), only when she became youthful and yearned for a husband.

[ Prof. A L Basham , in his ‘The Wonder That was India” , writes :

The marriage of boys, whether before or just after puberty, is no¬ where suggested, but the idea) of a rigorous period of studentship before marriage is always maintained. The child-marriage of both parties, which became common in later times among well-to-do families, has no basis at all in sacred literature, and it is very doubtful whether the child-marriage of girls was at all common until the late medieval period. The heroines of poetry and fiction are apparently full grown when they marry, and the numerous inscriptions which throw much light on the customs of the time give little or no indication of child-marriage. Ancient Indian medical authorities state that the best children are produced from mothers over sixteen, and apparently recognize the practice of child-marriage as occasionally occurring, but disapprove of it.]

The Rig-Veda (5, 7, 9) refers to young maidens completing their education as Brahmacharinis and then gaining husbands. The Vedas say that an educated girl should be married to an equally educated man “An unmarried young learned daughter should be married to a bridegroom who like her is learned. Never think of giving in marriage a daughter of very young age’”

– ā dhenavo dhunayantām aśiśvīḥ sabardughāḥ śaśayā apradugdhāḥ (RV 3.55.16).

Young women of the time could exercise their choice in the matter of their marriage. “The woman who is of gentle birth and of graceful form,” so runs a verse in the Rig Veda, “selects among many of her loved one as her husband. The term for the bridegroom was vara, the chosen one. ”The happy and beautiful bride chooses (vanute) by herself (svayam) her own husband” – (bhadrā vadhūr bhavati yat supeśāḥ svayaṃ sā mitraṃ vanute jane cit – RV 10. 27.12). The swayamvaram of the princesses are of course well documented.

kiyatī yoṣā maryato vadhūyoḥ pariprītā panyasā Vāryeṇa | bhadrā Vadhūr-bhavati yatsupeśāḥ svayaṁ sā mitraṁ vanute jane cit || RV.10.027.12 ||

Many marriages, as in the later day Hindu society today, involved the intercession of the families on either side, but a maiden was consulted and her wishes taken into account when the matrimonial alliance was discussed. The marriage hymns 139 in the Rig-Veda and the Atharvaveda indicate that the parties to marriage were generally grown up persons competent to woo and be wooed, qualified to give consent and make choice.

Young girls had the freedom to go out to attend fairs, festivals and assemblies’; the seclusion of women was not practiced. There is a reference to certain occasional festivals or gatherings called Samanas organized to help young boys and girls to get together. Rig Veda described Samana as where:

Wives and maidens attire themselves in gay robes and set forth to the joyous feast; youths and maidens hasten to the meadow when forest and field are clothed in fresh verdure to take part in dance. Cymbals sound and seizing each other lads and damsels whirl a about until the ground vibrates and clouds of dust envelop the gaily moving throng.

A girl often chose one of the suitors whom she met in these Samanas as her husband.

*

Dr. Bhagwat Saran Upadhya in his extensive work ‘Women In Rgveda‘ (Published by Nand Kishore and Brothers, Benares – 1941) writes :

**

Dr. Rukmani Trichur writes :

Vedic society was one which valued marriage very highly. If then, in a society that prized marriage as very high, a woman decided not to go through marriage, that would be a decision expressing not only her choice but also indicating her resolve to stand up to the pressure of society to go against its norms. That involves agency and power to take an independent decision. In Vedic society, we do find such women like Gargi.

Even in the Epics Ramayana and Mahabharata one finds women (like Damayanti, Savitri and Rukmini) who had the freedom to choose their spouse. And, Kuni-Garga (Shalya-parva- 52.3-25) refused to get married because she did not meet anyone suitable and up to her expectations. Similarly, Sulabha (mentioned in the Ashvalayana Grihya Sutra) refused marriage; for none of her suitors could match her in learning. She is celebrated in Mahabharata (Shanthi-parva-320) as a learned recluse who defeated King Janaka, in his own court.

**

The older texts talk of the seven steps around the Agni ; and , the vows taken based on mutual respect, taken during marriage

Sakaa -Sapthapadha -bhava Sakaayov -Saptha padhaa -Bhaboova

Sakyam -the’ -Ghame’yam Sakyaath -the’ Maayosham -Sakyan me’

Maayosta -Samayaava -Samayaava Sangalpaavahai -Sampriyov

Rosishnu -Sumanasyamanov Ishamoorjam – abhi -Savasaanov

Managhumsi -Samvrathaas smu Chiththaani -Aakaram -Sathvamasi

Amooham -Amoohamasmi saa -Thvam -dhyowraham

Pruthivee thvam -Retho’ aham -retho’ Bhruthvam -Manohamasmi

-vak thvam -Saamaa ham asmi -Rukthvam -Saamaam

Anuvradhaa -bhava Pumse’ Pumse’ -Puthraaya -Veththavai

Sriyai -Puthraaya -Veththavai ehi -Soonrurute’||

By these seven steps that you have taken with me, you have become my best friend. I will never move out of this relationship. God has united us in this bondage. We shall perform all activities together with love and affection and with good feelings. Let us be friendly in our thoughts. Let us observe our duties and rituals together. If you are the lyrics, I am the music. If you are the music I am the lyrics. If I am the heavenly body you are the earthly world. While I am the life source and you are the carrier of the same. I am the thoughts and you are the speech. When you are like the words, you work with me who is like the meaning of it. With your sweet words, come with me to lead a prosperous life begetting our progeny with children.

(Source: Taittiriya Ekagnikanda, I iii, 14. ; Sastri, 1918.)

It appears that the bride was given by her parents gold, cattle, horses, valuables , articles etc. which she carried to her new home .She had a right to deal with it as she pleased. No doubt the dowry a girl brought with her did render her more attractive. “How much a maiden is pleasing to the suitor who would marry for her splendid riches? If the girl be both good and fair of feature, she finds, herself, a friend among the people. “(Rig-Veda X .27.12)

kiyatī yoṣā maryato vadhūyoḥ pariprītā panyasā vāryeṇa |bhadrā vadhūr bhavati yat supeśāḥ svayaṃ sā mitraṃ vanute jane cit ||

There were also the woes of a father,” When a man’s daughter hath been ever eyeless, who, knowing, will be wroth with her for blindness? Which of the two will lose on him his anger-the man who leads her home or he who woos her?” (RV 10.27.11)

yasyānakṣā duhitā jātv āsa kas tāṃ vidvāṃ abhi manyāte andhām |kataro menim prati tam mucāte ya īṃ vahāte ya īṃ vā vareyāt ||

Marriage was an established institution in the Vedic Age. It was regarded as a social and religious duty; and not a contract. The husband-wife stood on equal footing and prayed for long lasting love and friendship. At the wedding, the bride addressed the assembly in which the sages too were present. [Rig Veda (10.85.26-27)]

pūṣā tveto nayatu hastagṛhyāśvinā tvā pra vahatāṃ rathena |gṛhān gaccha gṛhapatnī yathāso vaśinī tvaṃ vidatham ā vadāsi ||iha priyam prajayā te sam ṛdhyatām asmin gṛhe gārhapatyāya jāgṛhi |enā patyā tanvaṃ saṃ sṛjasvādhā jivrī vidatham ā vadāthaḥ ||

[The term Kanya-daan or the concept of the father gifting away his daughter does not appear in Rig-Veda. She is treated with much dignity , honor and Love]

Marriage was not compulsory for a woman; an unmarried who stayed back in the house of her parents was called Amajur, a girl who grew old at her father’s house. An unmarried person was however not eligible to participate in Vedic sacrifices.

A woman, if she chose, could marry even after the child bearing age. For instance Ghosa a well known female sage married at a late stage in her life (her husband being another well known scholar of that time Kaksivan) , as she had earlier suffered from some skin ailment. And, late in her life (vadhramatya), with the blessings of the Asvins, Ghosa gave birth to a son , who was named as Hiranyahastha.

yuvam ǀ narā ǀ stuvate ǀ kṛṣṇiyāya ǀ viṣṇāpvam ǀ dadathuḥ ǀ viśvakāya ǀ Ghoṣāyai ǀ cit ǀ pitṛ-sade ǀ duroṇe ǀ patim ǀ jūryantyai ǀ aśvinau ǀ adattam ǁ 1.117.07 ǁ

ajohavīt ǀ nāsatyā ǀ karā ǀ vām ǀ mahe ǀ yāman ǀ puru-bhujā ǀ puram-dhiḥ ǀ śrutam ǀ tat ǀ śāsuḥ-iva ǀ vadhri-matyāḥ ǀ hiraṇya-hastam ǀ aśvinau ǀ adattam ǁ1.117.24 ǁ

**

Monogamy normally prevailed but polygamy was also in vogue . Some scholars say that polyandry and divorce were also common. There are no direct references to that. I am not therefore sure of that.

[Polygamy, in ordinary circumstances, was not encouraged by the earlier legal literature. One Dharma Sutra definitely forbids a man to take a second wife if his first is of good character and has borne him sons. Another later source states that a polygamist is unfit to testify in a court of law. The Arthasastra lays down various rules which discourage wanton polygamy, including the payment of compensation to the first wife. The ideal models of Hindu marriage are the hero Rama and his faithful wife Slta, whose mutual love was never broken by the rivalry of a co-wife. However, polygamous marriages are so frequently mentioned that wc may assume that they were fairly common among all sections of the community who could afford them .

Polyandry, was not wholly unknown, though it was impossible for ordinary people of respectable class in most parts of India – Prof. A L Basham]

[ Prof. A L Basham (The Wonder That Was India) mentions :

Though the religious law books leave no room for divorce, the Arthasastra shows that it was possible in early times, at least in marriages not solemnized by religious rites. In this case divorce was allowed by mutual consent on grounds of incompatibility ; and one party might obtain divorce without the consent of the other if apprehensive of actual physical danger from his or her partner. The Arthasastra would allow divorce even after religious marriage to a wife who has been deserted by her husband, and lays down waiting periods of from one to twelve years, which vary according to circumstances and class. These provisions, however, do not appear in later law books, and were probably forgotten by Gupta times, when divorce became virtually impossible for people of the higher classes.]

Widows were allowed to remarry if they so desired, particularly when they were childless; and , faced no condemnation and ostracization socially.

Married life

A girl when she marries moves into another household where she becomes part of it. Her gotra changes from that of her father into that of her husband. She participates in performances of yagnas for devas and pitrs of her husband’s family. The bride takes charge of her new family that includes her husband, his parents, brothers and sisters; and others who lived there for some reason.

The Rig Veda hymn (10, 85.27) , the wedding prayer , indicates the rights of a woman as wife. It is addressed to the bride sitting next to bridegroom. It touches upon few other issues as well.

“Happy be you (as wife) in future and prosper with your children here (in the house): be vigilant to rule your household in this home (i.e. exercise your authority as the main figure in your home). Closely unite (be an active participant) in marriage with this man, your husband. So shall you, full of years (for a very long life), address your company (i.e. others in the house listen to you, and obey and care about what you have to say).” (Rig Veda: 10, 85.27)

iha priyam prajayā te sam ṛdhyatām asmin gṛhe gārhapatyāya jāgṛhi |enā patyā tanvaṃ saṃ sṛjasvādhā jivrī vidatham ā vadāthaḥ ||

The famous marriage hymn (10.85.46 ) calls upon members of the husband’s family to treat the daughter in law (invited into the family ‘as a river enters the sea’) as the queen samrajni.

samrājñī śvaśure bhava samrājñī śvaśrvām bhava I nanāndari samrājñī bhava samrājñī adhi devṛṣu ||

She is welcomed in many ways:

” Come, O desired of the gods, beautiful one with tender heart, with the charming look, good towards your husband, kind towards animals, destined to bring forth heroes. May you bring happiness for both our quadrupeds and bipeds.” (Rig Veda 10.85.44)

aghoracakṣur apatighny edhi śivā paśubhyaḥ sumanāḥ suvarcāḥ | vīrasūr devakāmā syonā śaṃ no bhava dvipade śaṃ catuṣpade ||

Over thy husband’s father and thy husband’s mother bear full sway. Over the sister of thy lord , over his brothers rule supreme”(Rig Veda 10.85.46)

samrājñī śvaśure bhava samrājñī śvaśrvām bhava |nanāndari samrājñī bhava samrājñī adhi devṛṣu ||

“Happy be thou and prosper with thy children here; be vigilant to rule thy household, in this home ‘. (Rig-Veda 10.85.27)

iha priyam prajayā te sam ṛdhyatām asmin gṛhe gārhapatyāya jāgṛhi |enā patyā tanvaṃ saṃ sṛjasvādhā jivrī vidatham ā vadāthaḥ ||

The idea of equality is expressed in the Rig Veda: “The home has, verily, its foundation in the wife”,” The wife and husband, being the equal halves of one substance, are equal in every respect; therefore both should join and take equal parts in all work, religious and secular.” (RV 5, 61. 8)

uta ghā nemo astutaḥ pumāṃ iti bruve paṇiḥ |sa vairadeya it samaḥ |

She was Pathni (the one who leads the husband through life), Dharmapathni (the one who guides the husband in dharma) and Sahadharmacharini (one who moves with the husband on the path of dharma).

To sum up, one can say that the bride in the Vedic ideal of a household was far from unimportant and weak. She did have an important position in the family and yielded considerable influence.

http://groups.msn.com/hindu-history/rawarchives.msnw?action=get_message&mview=0&ID_Message=181

Property –rights

The third chapter of Rig-Veda , considered its oldest part (3.31.1) commands that a son-less father accepts son of his daughter as his own son i.e. all properties of a son-less father shall be inherited by son of his daughter.

śāsad vahnir duhitur naptyaṃ gād vidvāṃ ṛtasya dīdhitiṃ saparyan |pitā yatra duhituḥ sekam ṛñjan saṃ śagmyena manasā dadhanve ||

Rik (3.31.2) commands that if parents have both son and daughter, son performs pindadaan (after death of father) and daughter be enriched with gifts.

na jāmaye tānvo riktham āraik cakāra garbhaṃ sanitur nidhānam |yadī mātaro janayanta vahnim anyaḥ kartā sukṛtor anya ṛndhan ||

Rik (2.17.7) also attests share of a daughter in property of her father .

amājūr iva pitroḥ sacā satī samānād ā sadasas tvām iye bhagam |kṛdhi praketam upa māsy ā bhara daddhi bhāgaṃ tanvo yena māmahaḥ ||

Married women inherited and shared properties. A Widow too was entitled to a share in the properties of the dead husband.

Widowhood and Remarriage:

Rig-Veda does not mention anywhere about the practice of the burning or burial of widows with their dead husbands. Rig Veda commands the window to return to her house, to live with her children and grand children; and confers on her the right to properties of her deceased husband. Rig Veda clearly approves marriage of the widow. Such women faced no condemnation or isolation in the household or society. They had the right to property inherited from the dead husbands. There are riks blessing the woman and her new husband, with progeny and happiness. Rig-Veda praises Ashwin gods for protecting widows.(X.40.8)

yuvaṃ ha kṛśaṃ yuvam aśvinā śayuṃ yuvaṃ vidhantaṃ vidhavām uruṣyathaḥ | yuvaṃ sanibhya stanayantam aśvināpa vrajam ūrṇuthaḥ saptāsyam ||

Ambassador O P Gupta, IFS has made an excellent presentation of the status of widows in Rig Vedic times

(http://sify.com/news/othernews/fullstory.php?id=13170729 )

According to him:

None of the Riks in Rig Veda calls for the burning or burial of widow with body of her dead husband.

A set of 14 Riks in 18th Mandala of the 10th book deal with treatment of widows.

Rik (X.18.8) is recited by the dead man’s brothers and others, requesting the widow to release her husband’s body for cremation. The Rik also commands the widow to return to the world of living beings, return to her home and to her children and grand children, “Rise, woman, (and go) to the world of living beings; come, this man near whom you sleep is lifeless; you have enjoyed this state of being the wife of your husband, the suitor who took you by the hand.”

ud īrṣva nāry abhi jīvalokaṃ gatāsum etam upa śeṣa ehi |hastagrābhasya didhiṣos tavedam patyur janitvam abhi sam babhūtha ||

This rik also, confers upon her full right on house and properties of her deceased husband. [It was only in the year 1995 the Supreme Court of India interpreted Section 14(1) of the Hindu Succession Act to allow Hindu widow full ownership rights over properties she inherits from her deceased husband]

Rig-Veda not only sanctions survival of a widow and her right to property; but also approves her marriage with the brother of her dead husband; and to live with full dignity and honor in the family. Rig Veda therefore expressly sanctions widow-marriage. Some scholars say the widow could marry any person, not necessarily the brother of the deceased husband or a relative.

Rik (x.18.8) blesses a woman at her second marriage, with progeny and prosperity in this life time:: Go up, O woman, to the world of living; you stand by this one who is deceased; come! to him who grasps your hand, your second spouse (didhisu) ,you have now entered into the relation of wife to husband.

In rik (X.18.9) the new husband while taking the widow as his wife says to her: let us launch a new life of valor and strength begetting male children overcoming all enemies who may assail us.

dhanur hastād ādadāno mṛtasyāsme kṣatrāya varcase balāya | atraiva tvam iha vayaṃ suvīrā viśvā spṛdho abhimātīr jayema ||

AV(XVIII.3.4) blesses the widow to have a happy life with present husband ::O ye inviolable one ! (the widow) tread the path of wise in front of thee and choose this man (another suitor) as thy husband. Joyfully receive him and may the two of you mount the world of happiness.

prajānaty aghnye jīvalokaṃ devānāṃ panthām anusaṃcarantī |ayaṃ te gopatis taṃ juṣasva svargaṃ lokam adhi rohayainam ||4||

**

[Prof. A S Altekar in his celebrated work ‘The Position of women in Hindu civilization’ , mentions under the Chapter – Position of the widow Part II ; Section II (Widow remarriage – Page 177) mentions :

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.56806/page/n195/mode/1up

The widow re-marriage prevailed in Vedic Society. The suggestion that the proposal for a re-marriage was made to the at the funeral of her husband is preposterous. It is based upon a wrong interpretation of a Vedic stanza –RV.5.10.18.8

udīrṣva nāryabhi jīvalokaṁ gatāsumetamupa śeṣa ehi | hastagrābhasya didhiṣostavedaṁ patyurjanitvamabhi saṁ babhūtha || 10.018.08 //

The Verse in question merely seeks to dissuade the widow from taking extreme steps. It aims to encourage the widow to come back to the living society and lead a purposeful life.

The Verse, in fact reads: ‘Oh Lady, get up; come back to the world of the living. As far as your wife-hood to your husband I, who had seized your hand in marriage, is concerned you have lived it out completely’.

*

At another place , Atharva Veda , referring to a woman marrying a second time, prescribes a ritual to secure the union of the new couple in heaven.

yā pūrvaṃ patiṃ vittvā ‘thānyaṃ vindate ‘param | pañcaudanaṃ ca tāv ajaṃ dadāto na vi yoṣataḥ ||AV.9.5.27// samānaloko bhavati punarbhuvāparaḥ patiḥ | yo ‘jaṃ pañcaudanam dakṣiṇājyotiṣaṃ dadāti |AV.9.5. 28//

*

The Widow-re marriage, was however going out of practice by about the first century of the common era. Nevertheless, the opponents of the widow remarriage were not against the remarriage of the child-widows. But, by about 600 AD, the prejudice against widow remarriage began to get deeper and harder.]

******

During the post-Vedic period, woman lost the high status she once enjoyed in society. She lost some of her independence. She became a subject of protection.

The period after 300 B.C witnessed a succession of invasions and influx of foreigners such as the Greeks, the Scythians, the Parthian, the Kushans and others. The political misfortunes, the war atrocities followed by long spells of anarchy and lawlessness had a disastrous effect on the society. Fear and insecurity haunted the common people and householders. Sons were valued higher than the daughters because of the need for more fighting males, in order to survive the waves of onslaughts. It was also imperative to protect women from abductors. It therefore became necessary to curtail women’s freedom and movements’ . Early marriage was perhaps employed as a part of those defensive measures. The education of the girl child was no longer a priority. Sastras too compromised by accepting marriage as a substitute for Upanayana and education.

After about the beginning of the Christian era, the Upanayana for girls went out of vogue. The discontinuance of Upanayana was disastrous to the educational and religious status of women. The mischief caused by the discontinuance of Upanayana was further enhanced by the lowering of the marriageable age. In the Vedic period girls were married at about the age of 16 or 17; but by Ca. 500 B. C. the custom arose of marrying them soon after the attainment of puberty. Later writers like Yajnavalkya (200 A. D.), Samvarta and Yama, vehemently condemned the guardian who failed to get his daughter married before she attained puberty. Therefore, the Smritis written by 11th century began to glorify the merits of a girl’s marriage at the age of 7, 8, or 9, when it was regarded as an ideal thing to celebrate a girl’s marriage (Ashta varsheth bhaveth Kanya) . It is not surprising that with marriage at such a tender age, female education could hardly take off or prosper.

The neglect of education, early marriage , imposing seclusion and insecurity that gripped their lives, had disastrous consequences upon the esteem and status of women . The society in turn sank into depravity.

The social conditions deteriorated rapidly during the medieval period.

For nearly 2000 years from 300 B.C. to A.D. 1800, truly the dark ages of India, the development of woman steadily stuttered though she was affectionately nurtured by the parents, loved by the husband and cared by her children.

Now, it is the time of reawakening. Women of India are beginning to get opportunities to establish their identity and be recognized for their potential, talent and capabilities. That is a good rebeginning. The process must improve both in terms of its spread and quality. The ancient principles of equal opportunities for learning and development, equitable position in place of work and right to seek out her destiny, with honor; that guided the Vedic society must soon find a place in all segments of the society. It may sound like asking for the moon. But, that is the only option India has if it has to survive as a nation.

References