[This Twelfth article in the series; and , it follows the one on the murals of Kerala which talked, in general, about some of the main features of the traditional mural art of Kerala, which has a unique style of drawing and depiction; and colour schemes.

The present article looks at the murals at Mattanchery and Padmanabhapuram Palaces, as particular instances of traditional Kerala mural art..

This article and its companion posts may be treated as an extension of the series I posted on the Art of Painting in Ancient India ..

In the next article we shall move on to the 20th and 21st century and admire the sublime paintings of Shri S Rajam, perhaps the sole votary of Chitrasutra tradition in the modern times. ]

Continued from the Legacy of Chitrasutra- Eleven- The Murals of Kerala

A. Mattancherry Palace

49.1. Mattancherry , in Cochin, had been the former capital of the erstwhile rulers of Kochi. It was a bustling sea port to where the Portuguese and the Dutch traders were drawn by the lure of the legendary spices of the East, especially the black pepper. They established business houses and built large warehouses, at Kochi.

49.2. It is said; the Portuguese traders, in order to seek favours, beguile or appease the then king of Kochi, Veera Kerala Varma Thampuran (1537-61), built for his use (in 1552/1555) a palace at Mattanchery and also gifted him a golden crown. The Dutch, who later arrived on the scene by 1663, promptly displaced the Portuguese and took over the spice trade. The Dutch, for reasons similar to the ones that prompted the Portuguese, refurbished the king’s palace at Mattanchery. Since then, the Mattanchery palace has come to be known as the Dutch Palace. It had been the residence of the Kochi royal family for about two centuries.

49.2. There is a certain medieval charm and simplicity about the Mattancherry Palace .The palace is a blend of Portuguese architecture and Kerala style of construction,; a ‘Nettukettu’ (four buildings) with a shrine of Pazhayannur Bhagavathy, deity of the royal family, in the central courtyard. Its interiors are made beautiful with rich wood work and exquisite flooring that looks like polished black granite; but it is actually made of a mixture of charcoal, burnt coconut shells, lime, plant juices and egg whites. The palace has within it two other temples, dedicated to Krishna and Shiva.

The Mattancherry Palace is included in the ‘Tentative list of nominations‘ in India , under the World Heritage List of the UNESCO.

50. The Murals

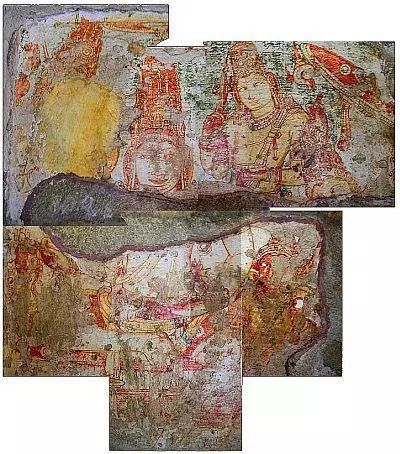

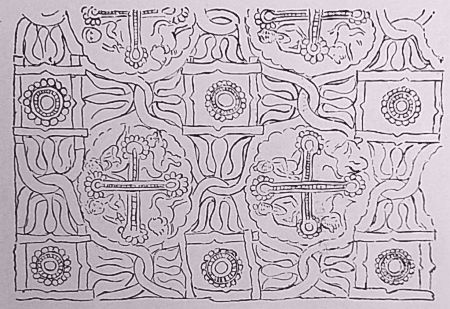

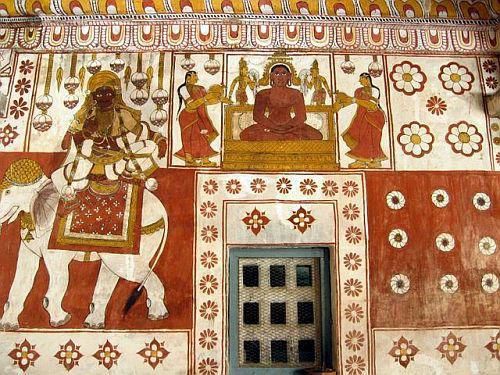

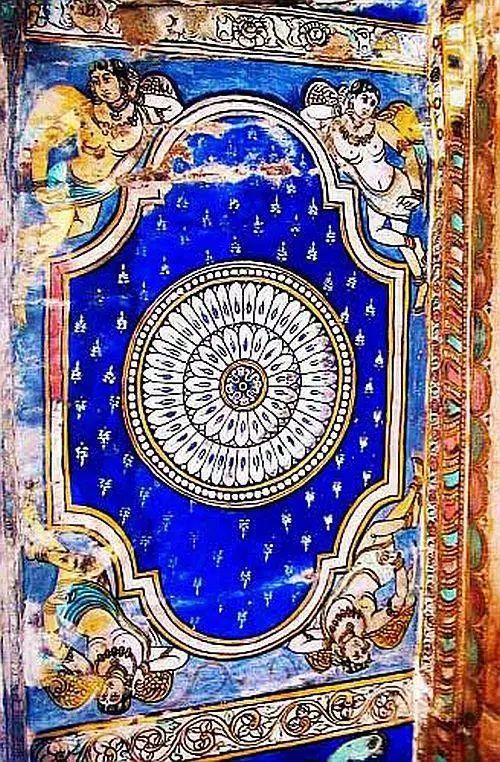

50.1. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the walls in some rooms of the palace were painted with scenes from Ramayana, Mahabharata and other epic poems. Most of the murals are adorned with decorative textile design borders filled with figures of the flowers, creepers, birds, animals etc.

The paintings are massive and are spread over a total area of almost 1000 sq. ft.

50.2. The palace is a treasury of the 16th-17th century Kerala art. It is an artist’s delight. It is said; the late Amrita Sher Gill, the well known painter who visited the palace in 1937 was fascinated by these ‘perfectly marvellous old paintings’. In a letter to her sister, she said she was surprised by the technique and the amazing knowledge of form and the power of observation of the painters. According to her, the Mattanchery paintings were more powerful than the Ajanta frescoes; but the latter were superior from the painting and artistic aspects.

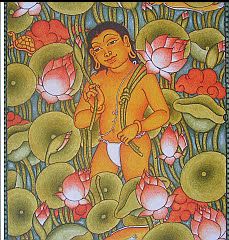

50.3. The earliest paintings of the 16th century are on the theme of Venugopala (Krishna as the divine flute player). These panels were, in later years, interspersed with paintings depicting episodes from the epic-poem the Ramayana. Some say that the Mattanchery palace Ramayana murals are the visual interpretations of the Adhyatma Ramayana of Ezhuthachan, the great Malayalam poet of the 15th century.

50.4. The Ramayana murals

The Ramayana murals of Mattanchery palace depict the story of Rama, commencing from Dasharatha offering a yajna praying to gods to grant him sons; and it concludes with Rama returning, triumphantly , to Ayodhya , along with his beloved Sita and brother Lakshmana. The Rama-story is rendered in about 48 paintings covering nearly 300 sq ft (28 m2) of wall surface. Rama’s nobility, unsullied character and composure even while placed in adverse situations, comes through serenely.

The narration of the episodes flow smoothly, each panel theme lucidly leading to the next. The themes are separated from one another by decorative borders, unique to the Kerala mural tradition. Besides giving a subtle form of relief to the pictures, they seem to convey a sense of motion.

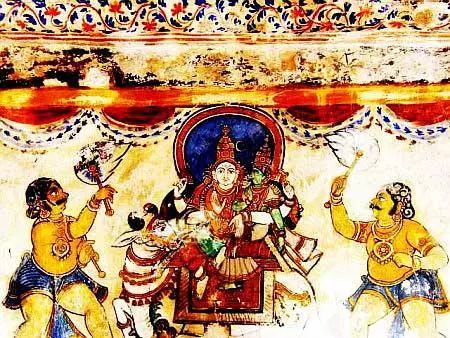

50.5. Besides the Ramayana paintings there are portrayals of Krishna holding aloft Govardhana hill, another of a flute-playing Krishna (Venugopala) in jewel-like green.

There is also a mural of Krishna in reclining posture, surrounded by gopis,. His languid pose belies the activity of his six hands and two feet, caressing his adoring admirers. Apparently, these panels were later additions.

50.6. The themes from the epic poem Kumara-sambhavam of the poet Kalidasa depict Shiva and Uma in their snow abode atop the Mount Kailas.

A painting on the walls of the Raja’s bedroom depicts Shiva and his consort Parvathi in embrace. They are surrounded by their son Ganapathi and other admirers. Interestingly, a guard wearing a Portuguese helmet and wielding a halberd, slaves and sages stand nearby. These paintings belong to a much later period than the Ramayana scenes; some of them to the beginning of the 18th and 19th centuries.

50.7. Among the depiction of Vishnu, his portrayal as Vaikuntanatha and Ananthasayanamurti are well known.

The seated Vishnu (Vaikuntanatha) under the canopy of five-hooded Anantha-naga is a rare depiction of Vishnu. It is said to be a replica of the deity at the Sree Poornathrayeesa Temple at Tripunithura, the family deity of the erstwhile Kochi dynasty. The Vishnu image at Tripunithura was, in turn, perhaps inspired by the Vishnu sculpture at the 6th century rock – cut temple of Badami.

There is also a composition of Lakshmi seated on a lotus. These are among the latest works in the palace.

50.8. According to the website of the Corporation of Cochin, many of these murals were painted in the traditional style by one Shri Govindan Embranthiri of Narayana- mangalam. No details are given.

51. True to the Kerala tradition

51.1. The beautiful and extensive murals of Mattanchery palace are fine examples of traditional Kerala mural art. Some of them are hailed for their style of depiction.

51.2. The murals are packed with details in gloriously rich colours; the style is never strictly true-to-life; the treatment of facial features is trimmed down to the simplest of lines for the mouths, and aquiline noses.

51.3. True to the Kerala tradition, the murals at Mattanchery are characterized by the warmth and grandeur of rich colours, elaborate ornamentation, sumptuousness of the outline, depiction of volume through subtle shading, a crowding of space by divine or heroic figures; a strong sense of design and well defined picturization.

******

B. Padmanabhapuram Palace

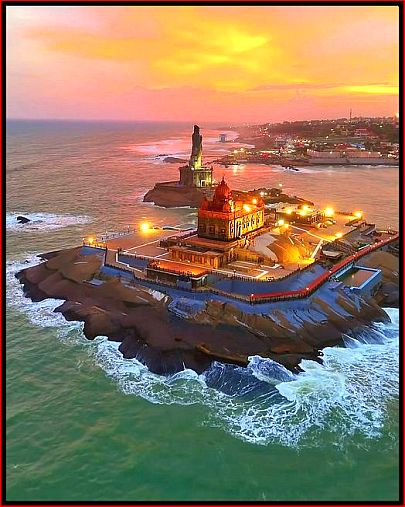

54. The palace

54.1. Padmanabhapuram palace, the exquisite wooden palace was constructed in the early years of the seventeenth century (say, around 1602) during the reign of by Iravipillai Iravivarma Kulasekhara Perumal who ruled Travancore State between 1592 and 1609 A.D. It is said to have been built upon an earlier mud palace in the Nalukettu style of architecture, constructed during the 14th Century.

The Padmanabhapuram palace is a splendid illustration of the traditional Kerala architectural style. it is unlike any other palace in India. Replete with intricate wood carvings and ornate murals, the Palace is an exceptional example of indigenous building techniques and craftsmanship in wood; a style unparalleled in the world and based on historic building system, Taccusastra (the science of carpentry) unique to this region.

The 6.5 acres of the Padmanabhapuram Palace complex is set within a fort of 185 acres located strategically at the foot hills of Veli hills, Western Ghats. The palace complex, which includes fourteen function specific independent buildings surrounded by a 4 km-long stone fort, is located virtually at the land’s-end. The fourteen denoted structures include Kottarams (Palaces); Pura (House or structure); Malikas (Mansions); Vilasams (Mansions) and Mandapams (large Halls).

The Palace structure is constructed out of wood with laterite (locally available building stone) used very minimally for plinths and for a few select walls. The roof structure is constructed out of timber, covered with clay tiles.

54.2. The Palace served as the secure official residence to the Travancore Kings for about two hundred years from 1550 to 1750.

It is said, the reign of the King Marthanda Varma (1729-1758), was a glorious period in the history of Padmanabhapuram palace. He provided a serene and secure ambiance to the palace; and gave it its present name – Padmanabhapuram palace (c.1744) in honour of the State’s patron deity. Its earlier name was Kalkulam.

The Padmanabhapuram palace was the centre of political power during the years 1600 to 1790, that is till the time the state capital was shifted to Thiruvananthapuram (also known as Trivandrum).

[ There is an interesting sidelight concerning Martanda Varma and the Dutch.

On February 4, 1741, the Dutch forces launched an assault hoping to unseat Marthanda Varma. In response, Marthanda Varma’s army surrounded the attackers; and, laid a siege , cutting down their supply lines. The siege ended on August 5, 1741, with an unconditional surrender of all the Dutch forces.

The Dutch East India Company commander and his lieutenant were captured; and, were later employed to train; to modernize the Army of Travancore ; and, to build forts. The Dutch signed the treaty of Mavellikara, formalizing their defeat.

The Dutch trained Travancore Army was later absorbed into the Indian Army ; and, formed the 9th Battalion of the Madras Regiment. The battalion still celebrates July 31 every year as Colachel Day . ]

In 1993, a Museum building was set up in the Southwest corner of this Palace complex, and houses numerous invaluable stone inscriptions and copper plate inscriptions, sculptures in wood and stone, armoury, coins, paintings, and household objects pertaining to the history and heritage of the region.

Padmanabhapuram Palace is the oldest, largest and well preserved surviving example representative of the traditional wooden architecture in India. It is an testimony to the traditional architectural knowledge and skill of Kerala. It is , therefore, included in the ‘Tentative list of nominations‘ in India , under the World Heritage List of the UNESCO.

55. The Murals

55.1.One of the structures in the Palace is an outstanding example of the Mural art form.

The splendid antique interiors are adorned with intricate rosewood carvings and sculptured décor; and the elegance of the palace is enhanced by some beautiful 17th and18th century murals

55.2. The murals at Padmanabhapuram are exceptional. Besides the depiction of scenes and characters from Hindu mythologies, there are murals also on secular themes which reflect the socio political conditions, fashions and customs of the times.

The UppirikaMalika or the four-storeyed building, constructed in 1750 CE, includes the treasury chamber on the first floor, Maharaja’s resting room on the second floor, and the revered prayer room on the third floor the walls of which are replete with traditional Kerala mural art work.

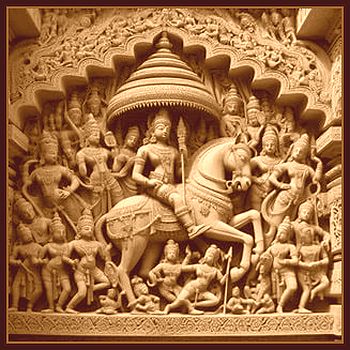

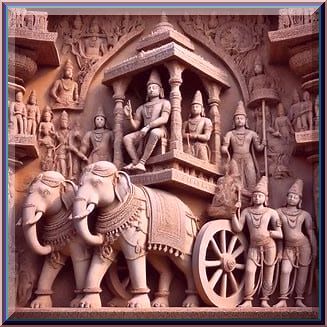

The walls of the chamber in the topmost floor (Upparika malika) of the palace are covered with beautiful murals painted in the traditional Kerala style; and, they resemble the paintings at the Sri Padmanabha Swami Temple of Thiruvananthapuram. About forty-five of those murals occupy almost 900 sq ft of wall surface, depicting Vaishnava themes, such as: Anantasayanan, Lakshminarayana, Krishna with Gopis, Sastha etc.

The murals at the Padmanabhapuram palace – executed in the traditional style invoking rich and vivid realism and infusing grace and beauty of the figures – are the best preserved in the State .

The depiction of the Krishna theme (Krishna – leela) is inspired by Sri Krishna Karnamrutham, a collection of divine verses charged with intense love of Krishna, attributed to Biva-mangala (c.1220-1300 AD).

55.3. Shri Benoy K Behl, the scholar and art historian, remarks,” Unlike the Mattanchery paintings, the gods (in the murals at Padmanabhapuram palace) are presented in their iconic forms and not in narrative situations. The paintings again reveal the close relationship between the styles of art in diverse regions of India. The beautiful textiles as well as some of the forms recall the paintings of Alchi in Ladakh.”

Next

We shall move on to the 20th and 21st century and admire the sublime paintings of Shri S Rajam, perhaps the sole votary of Chitrasutra tradition in the modern times.

References and sources

http://www.cochin-ernakulam.com/travelinformation/mattancherrypalace.htm

http://www.indiamonuments.org/Mattancheri_Palace.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murals_of_Kerala

http://www.bharatonline.com/kerala/travel/cochin/mattancherry-palace.html

http://www.indianetzone.com/9/dravidian_mural_painting.htm

http://www.hinduonnet.com/fline/fl2121/stories/20041022000406400.htm

http://www.muralpaintingtraditionsinindia.com/krishnakumar.htm

http://sadanandan.com/keralamurals.html

http://www.thrikodithanam.org/mural.htm

http://tourism.webindia123.com/tourism/monuments/palaces/dutchpalace/index1.htm

http://www.keralamurals.in/2008/12/02/mattancheri-murals/

http://www.corporationofcochin.org/pages/Maintemp.asp?id=6&val=3

Murals of Kerala by M G Shashibhooshan, Dept. Of Public Relations, Kerala State.

http://www.keralamurals.in/2007/09/18/padmanabhapuram-murals/

http://travel.paintedstork.com/blog/2008/09/photo-essay-padmanabhapuram-palace.html

http://hubmagazine.mayyam.com/jan07/?t=8929

http://www.kerala.gov.in/dept_archaeology/index.htm#p

All pictures are from Internet

![10[1]](https://sreenivasaraos.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/1012.jpg?w=645)

![14[1]](https://sreenivasaraos.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/1412.jpg?w=645)

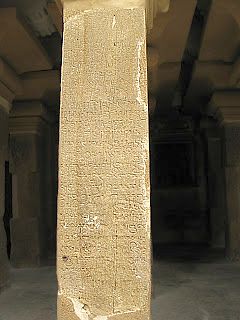

Hail Vikramaditya –sathyashraya, the favourite of Fortune and of earth, Maha-rajadhiraja Parameshwara Bhattara having captured Kanchi and after having inspected the riches of the temple, submitted them again to god of Rajasimheshwaram.

Hail Vikramaditya –sathyashraya, the favourite of Fortune and of earth, Maha-rajadhiraja Parameshwara Bhattara having captured Kanchi and after having inspected the riches of the temple, submitted them again to god of Rajasimheshwaram.