[This is the third in the series of articles I would be posting on the art of painting in ancient India with particular reference to the Chitrasutra of Vhishnudharmottara purana. The previous (second) article covered certain concepts and general aspects discussed in Chitrasutra.

The current article deals with the physical features of various classes and types of images, proportions, projections, foreshortening etc.

The next article discusses colours and representation of things seen and unseen; and briefly talks about certain symbolisms mentioned in the text.]

8. Tala-mana

8.1. The Indian artist never took in the world at a sweeping glance. He had an eye for details. In the canons of Indian art there is a definite and prescribed proportion of the limbs and their ratio to one another. The Indian artist paid more attention to ratio than to the actual standard of measurement of the different limbs. The ratio being the same, the figures may be pygmy or colossal. A standard measurement, however, was in vogue.

The absolute and relative systems of measurement

It is said; the Indian Vastu and Shilpa shastras recognize two standards of measurement: the absolute and the relative systems.

In the absolute standard, the smallest unit of measurement is the almost microscopic particle of dust observable in the solar rays or atom. This measurement is named in different ways according to the texts, like for example Trasarenu, Paramanu or Chayanu (shadow of an atom).

Other measurements of the absolute system are the particle of dust called raja or renu, the tip of hair called Balagra, Valagra or Keshagra, the nit called Liksha or Likhya, the louse or yuka, the barley com or yava and the highest unit of this system is the digit or angula which corresponds to the width of the middle finger. They have a relation of one to eight as follows:

- 8 paramanus make 1 renu

- 8 renus make 1 balagra

- 8 balagras make 1 liksha

- 8 likshas make 1 yuka

- 8 yitkas make 1 yava

- 8 yavas make 1 angula

- 12 angulas make 1 Tala

Manangula is a linear measure; a determined by the length of the middle finger of the artisan or of the patron’s right hand and is employed for the construction of images. This measurement is a fixed unit.

Dehangula is the angula that is in relation to the image itself; and, is derived from the total height of the image to be fashioned. The Dehangula is essentially a relative unit, to indicate the height of an image.

**

According to the Citra-sutras, there are six types of measurement (mana) to be taken along the body of an image. These kinds of measurements constitute the six kinds of iconometric measurement as applied to standing, seated and reclining images.

Mana or measurement of the length of the body or its units (dhirgha); such as the distance from the hair-limit to the eye-line; from that point to the tip of the nose; the length of the arms and of the legs; and so on.

Pramana is the horizontal measurement or breadth (vistara), such as the distance between the two shoulders, the width of the body at the chest level, the width of the belly or the width of the arm or of the thigh

Unmana is the measurement of the elevation or thickness, such as the height of the breasts or of the nose

Parimana is for instance the girth of the arm or of the thigh.

Upamana is the measurement of the interspaces, i.e., the width of the navel, the interval between the two thighs or the two big toes.

Lambamana are measurements taken along the plumb-lines or sutras.

***

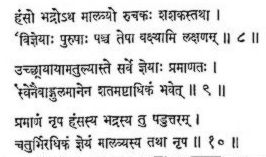

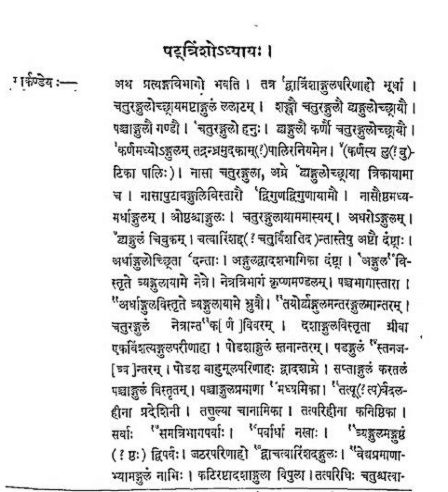

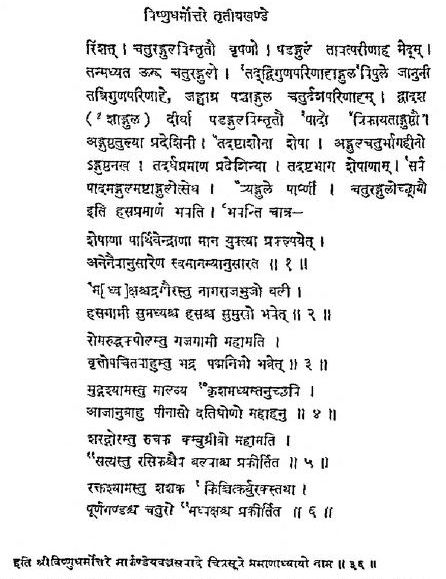

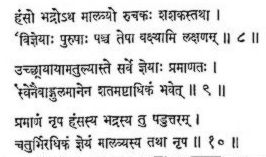

The Chitrasutra gives an elaborate classification of different types of men and women. They are classified into one of the five standard types (Pancha-purusha) called: Hamsa, Bhadra, Malavya, Ruchaka and sasaka.

Hamso Bhadrao tatha Malavyo Ruchaka Sasaka tatha/Vigneyaha Purushaha panch tesham vakshami lakshanam /3.35.8/

Their respective measures are given in terms of angula. The measurement of each of the types would be relative to their respective angulas, such as 108, 106, 104, 100, and 90 angulas.

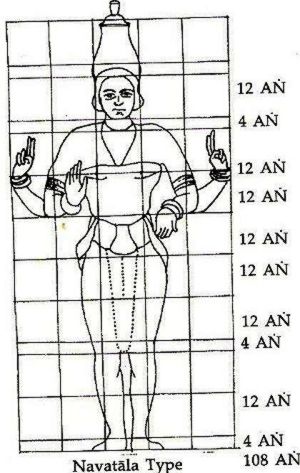

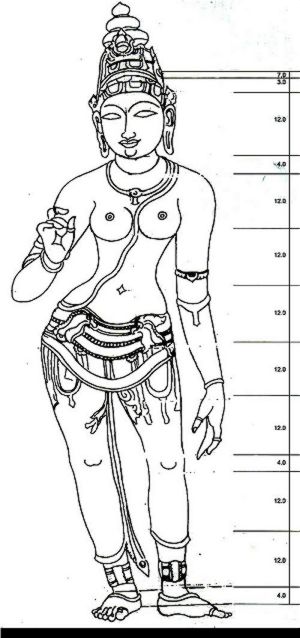

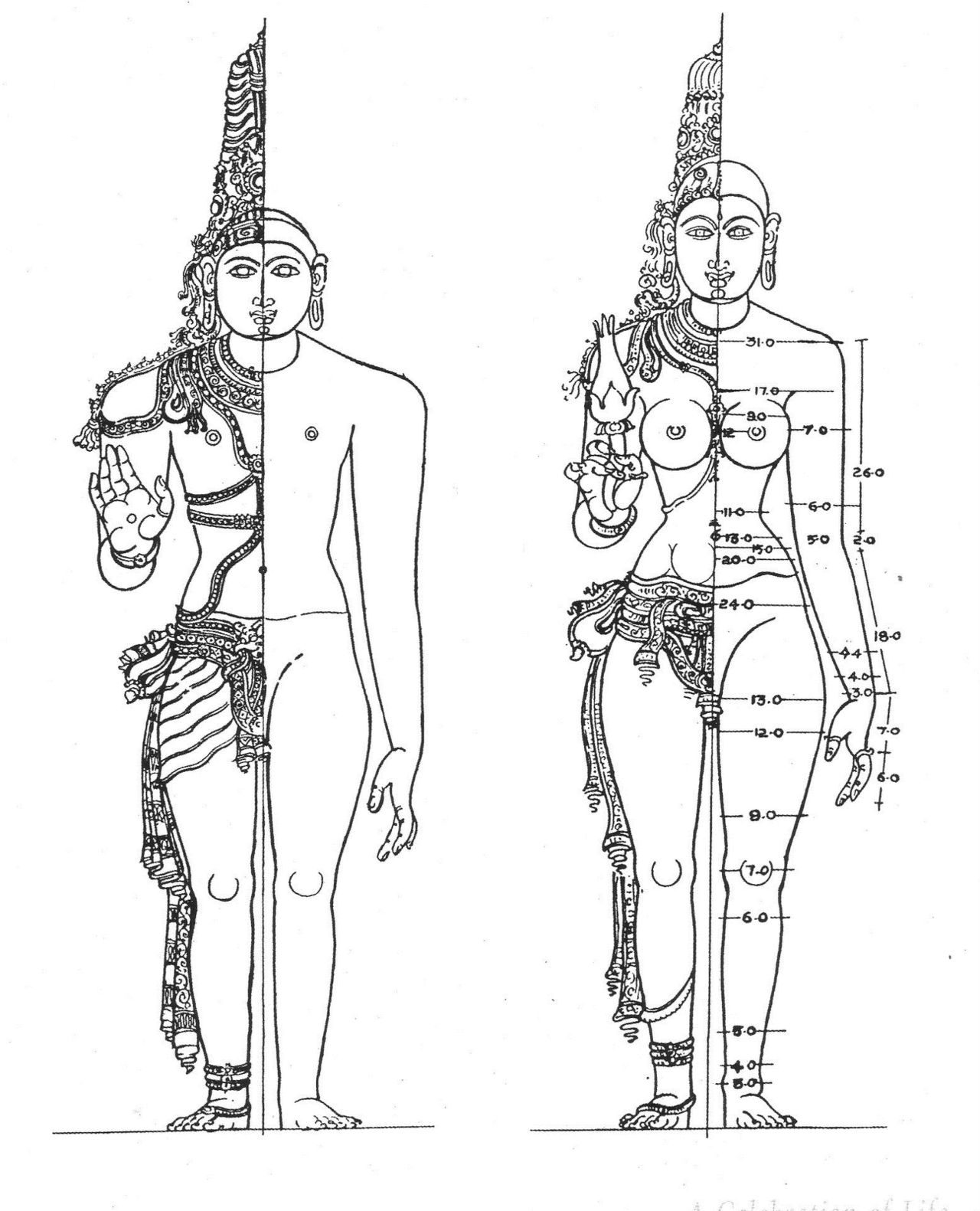

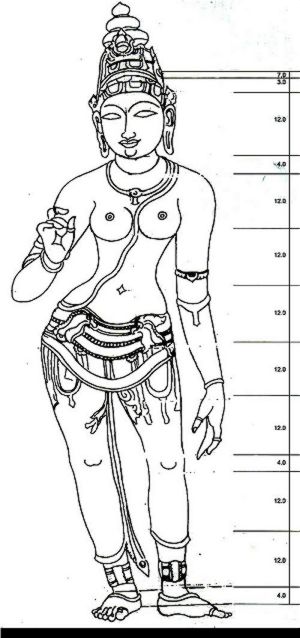

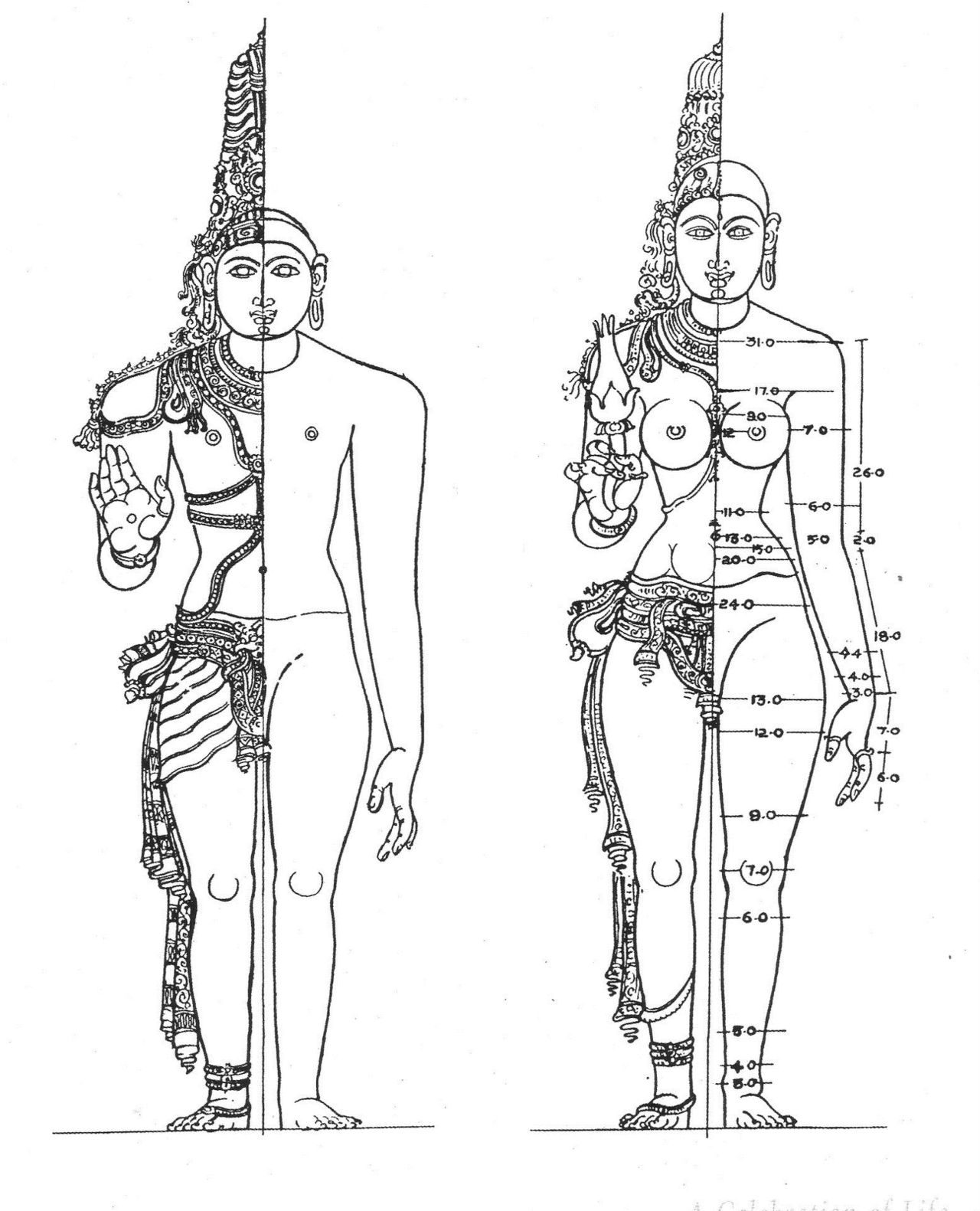

In the context of mana or proportion, the division of the limbs in terms of tala measurement is elaborately discussed in the Vishnudharmottara. Tala is said to be made of 12 Angulas : dvadasa-angula-vistaras tala ityabhidhiyate (3,35,11) . And, one tala, was taken as the length of the palm from the edge of the wrist to the tip of the middle figure. Usually, the face of the image would measure a length of one tala, which, in other words, would be one-ninth of the body length of a Hamsa category image. The proportions of the various parts of the image –body would be in terms of the tala and its denomination (the angula). Hamsa is the standard measurement of body -length of an image; and the proportions of the other categories of images (Bhadra etc.) are to be worked out by taking Hamsa as bench mark.

[A similar tala-mana system of proportions and measures governs the shilpa iconography. Its iconometry prescribes the proportion of the limbs and other parts of its body in relation to its face -length. The Indian artists are governed by proportions than by actual measurements. Thus a figure might look pygmy or colossal while the principles that govern the proportions would be the same.

These rules specify the various standards to be adopted for ensuring a harmonious creation endowed with well proportioned height, length, width and girth. These rules also govern the relative proportions of various physical features – of each class and each type of images.

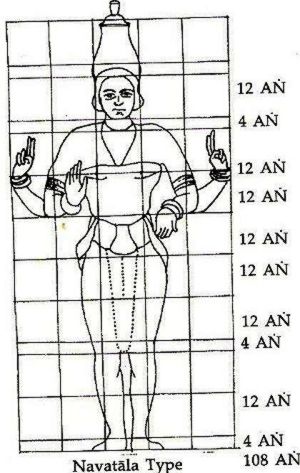

In shilpa-sastra, the madhyama navatala(standard height of nine-face lengths) is normally used for images of celestial beings such as Yakshas, Apsaras and Vidhyadharas. Here, the height of the image would be nine talas (with each tala divided in to 12 angulas) or a total height of 108 angulas.The angula (literally ‘finger’) is a finger’s width and measures one quarter of the width of the shilpi’s fist. The value of the angula so derived becomes a fixed length (manangulam), for all practical purposes, for that image. All other measurements of the image are in terms of that unit.

The face – length of the image i.e., from its chin up to the root of its hair on the forehead – would be 12 angulas or one tala. The length from throat to navel would be two tala; from navel to top of knee would be three tala; from the lower knee to ankle would be two tala making a total of eight tala. One tala is distributed equally between the heights of foot, knee, the neck and topknot. The nava tala thus will have a total of nine tala units, in height (108 angulas).

Hamsa of Chitrasutra corresponds to Nava-tala of the Shilpa sastra.

*

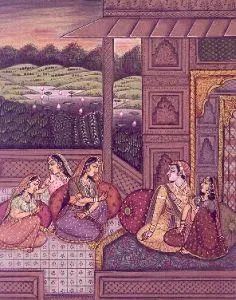

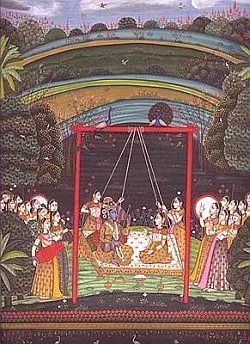

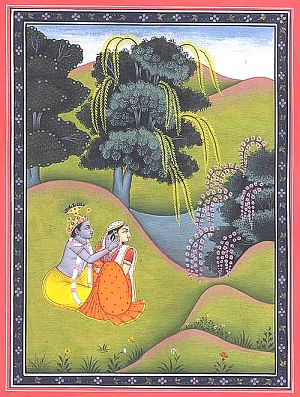

Sthana or stance for the figures grouped in a painting is very important; for, it is vital to indicate the action or repose in the picture, apart from highlighting its central theme.

“In composition the central figure is given importance over the other figures. And , that leads to the heightening of the fundamental emotions or fuller expression of the central figure for which alone the others exist.”

8.2.The text describes the characteristic features of the five categories of men.

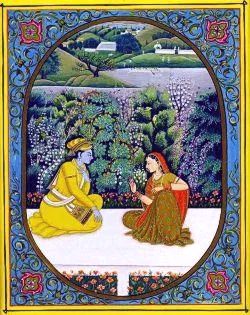

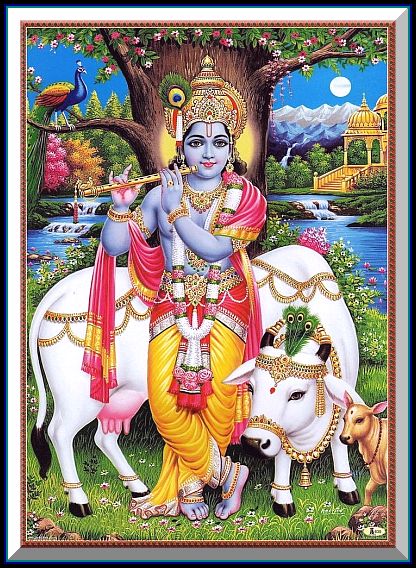

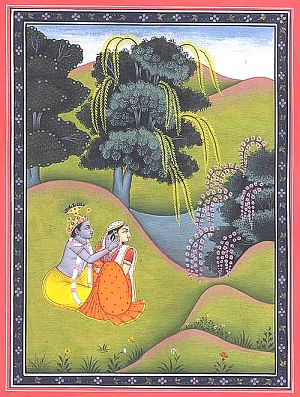

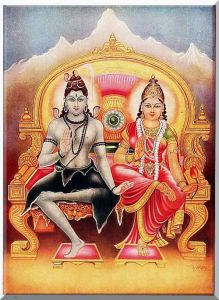

(i). Hamsa (108 angulas) should be strong, with arms resembling the king of serpents (Sesha) , with moon-white complexion, having sweet eyes, having the color of honey, set in a good-looking face; and with lion-like waist and swan-like majestic gait. The deities are depicted in Hamsa category of style.

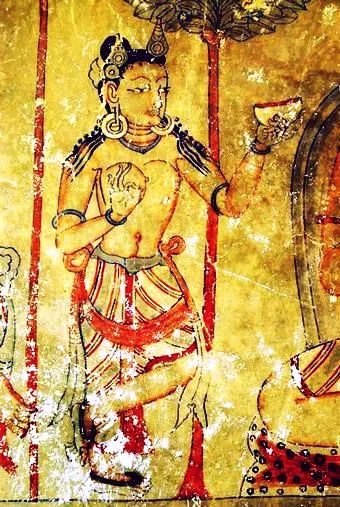

(ii).Bhadra (106 angulas) is learned, is of the color of lotus; with full grown tapering round arms, a hairy cheeks and elephant like step. The rishis, gandharvas, vidhyadharas, ministers and family priests are depicted under this category.

(iii). Malavya (104 angulas) is dark like a mudga –pulse (kidney bean?), good looking ; with a slender waist, arms reaching up to the knees, thick shoulders, broad jawas and a prominent nose like that of an elephant. The kinnaras, nagas, rakshasas and domestic women are depicted under Malavya category.

(iv). Ruchaka (100 angulas) is high souled, truthful and clever, of good taste. He is of autumn-white complexion and strong with a conch-like neck. Yakshas, vaishyas and prostitutes are depicted under this category. And,

(v). Sasaka (90 angulas) is clever reddish dark and of a slightly spotted colour; with full cheeks and sweet eyes. The tribal chiefs and sudras are depicted as Sasaka.

Measurement of Hamsa is the standard measurement given, in relation to which the measurements of the other types are to be worked out; keeping in mind the characteristics of that particular type.

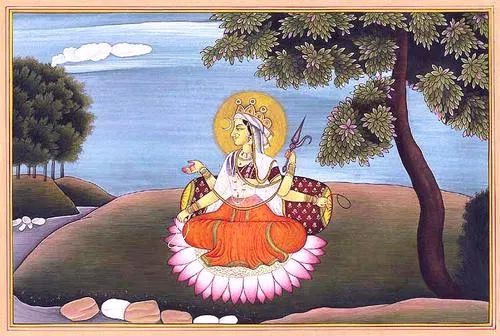

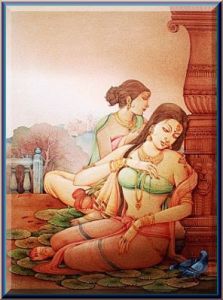

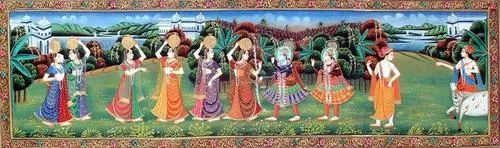

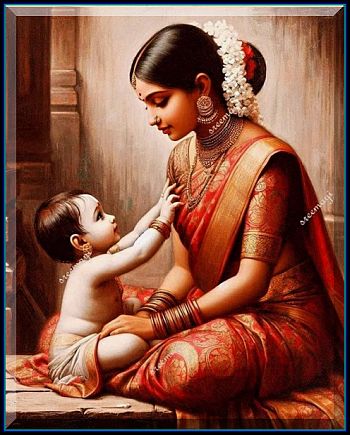

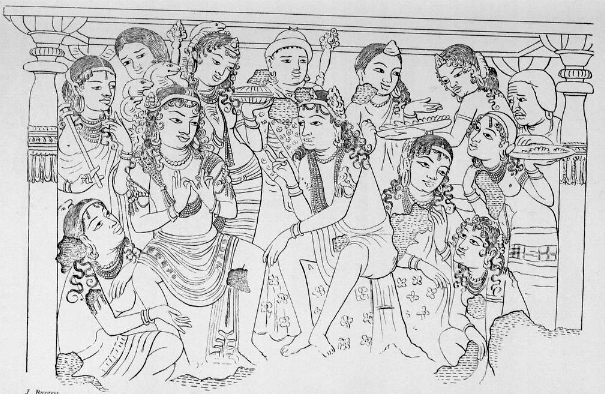

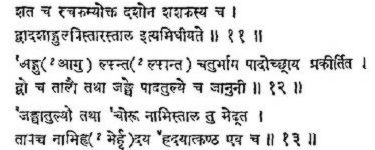

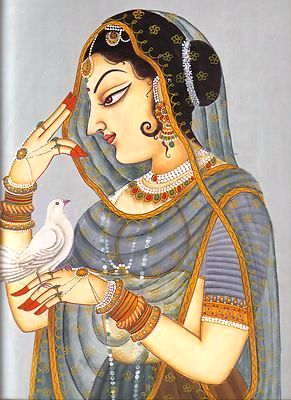

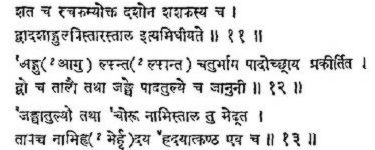

8.3. As regards the female figures, there is a discussion about the body types of women; but , it has not been specified .However, the discussion does state that they too fall under each of the above five categories of males, according to the measurements of the limbs and parts. Therefore, there would be five kinds of female bodies. The figures corresponding to various categories (say Hamsa, Bhadra etc.) too should be depicted in proportions that are applicable to that male-category.

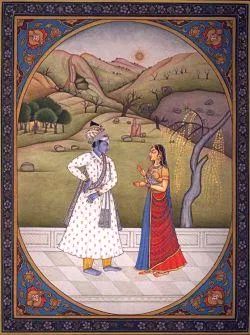

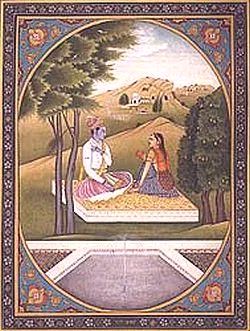

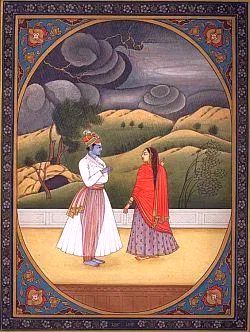

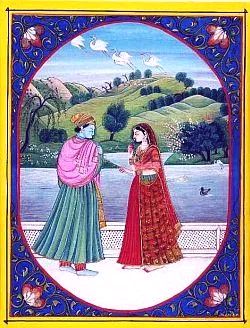

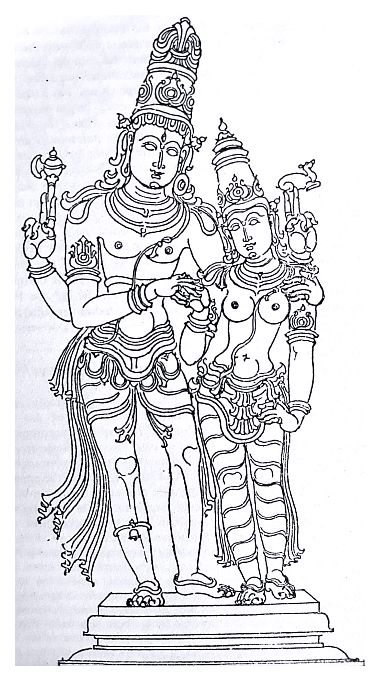

But the size of the female figures should be smaller than of the male figures appearing on the same canvass or surface. Her height should be made to reach the shoulder of the man placed near her, in proportion. Her waist should be two angulas thinner than that of a man. On the other hand, her hips should be made wider by four angulas. The breasts should be rendered soft, charming and proportionate to her chest.

Purushasya sameepastha kartavya Yoshi-Isvara /Nara-skanda pramanena karyeka sa yatha -mithi / 3.37.2/

Angulau dva Nara-vaksham Striyo madhyam vidiyate / adhika cha katih karya tathaiva chatur-angulam /3.37.3 /

Uruh pramanataha karyai sthanau nrupa manoharau / Nrupascha sarve karthaya Maha-purusha lakshanaha /3.37.4/

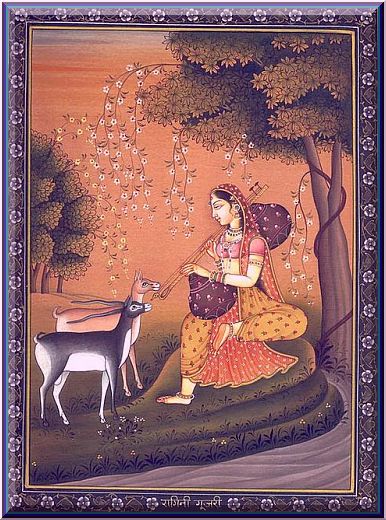

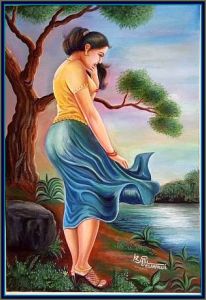

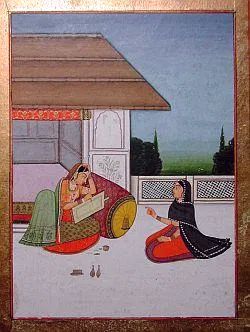

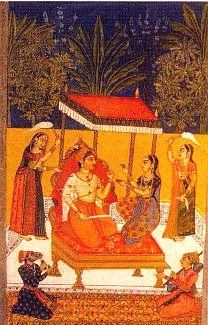

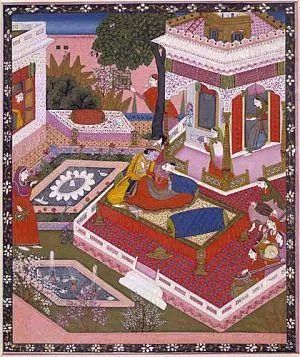

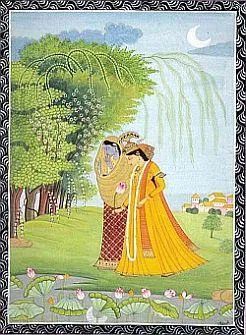

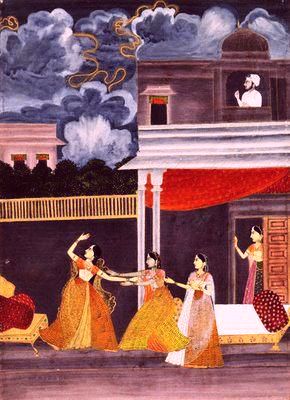

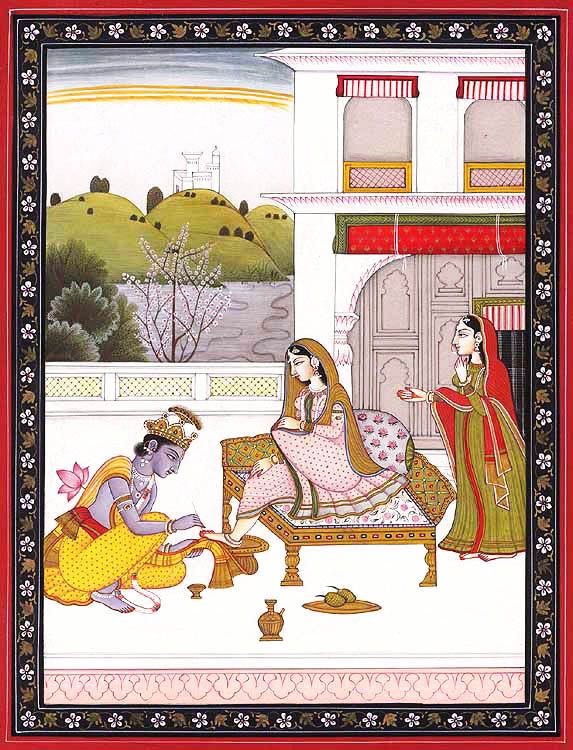

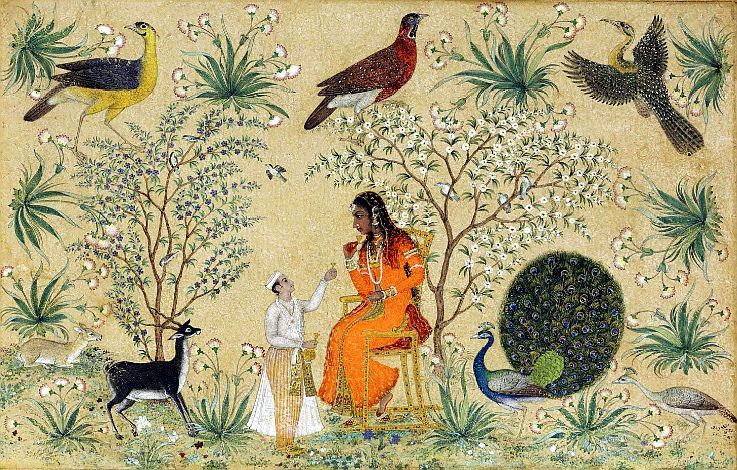

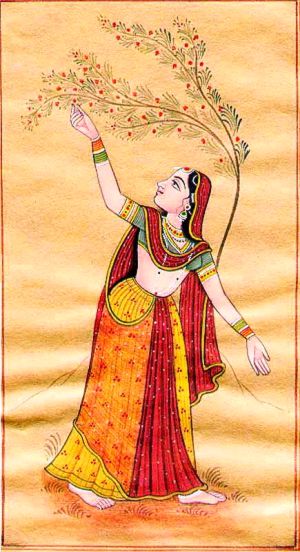

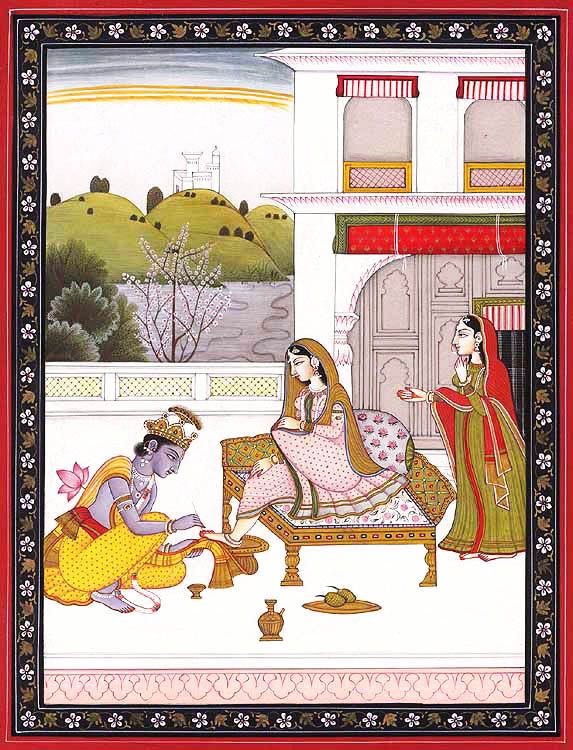

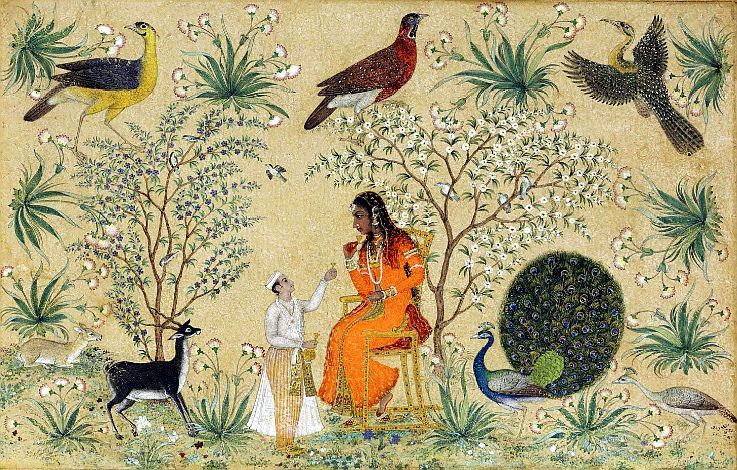

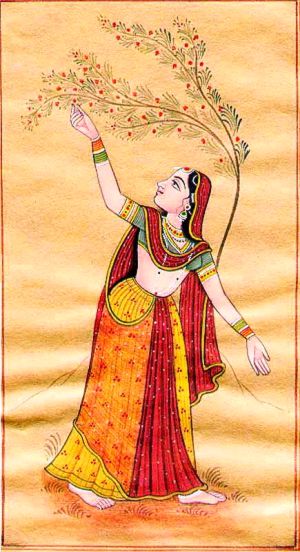

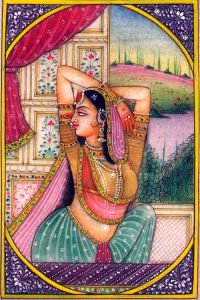

Talking about women, the text mentions elsewhere, “a female figure should be drawn with one foot calmly advanced, and with the part about the hips and loins broad and flurried on account of amorous dalliance”.

Leela-vilasa-vibrantham-vishala-jhagana-sthalam/sthira-eka-paada-vinyasam-stri-rupam-vilekhe-adbudhaha/ 3.39.50//

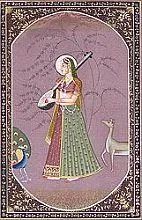

The women of good-family should be made bashful, wearing modest ornaments and not-showy dresses; and, with a slender waist, depicted under Malavya characteristics.

– Malavya maana-thaha karya lajja-vathyaha Kula-striyaha ; Na atyunnatena veshena sa-alamkara thathiva cha / 3.42.25/

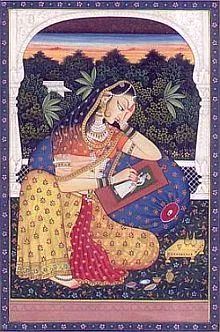

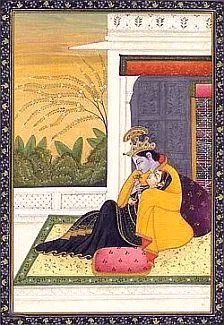

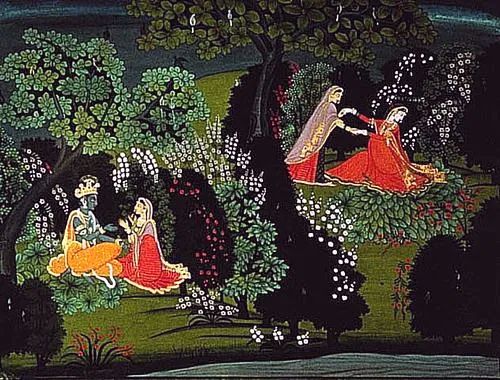

Her expressions of love are Sukumara (gentle, delicate and graceful). When she is in love, her eyes clearly show her feelings. Her eyes are, at the same time, tearfully smiling, slightly closed; while her eyelids droop. When she looks at her lover with half closed eyes, she appears beautiful, graceful and inviting. And, when she blushes, there are drops of sweat on her cheeks; and, there is a discreet thrill, stiffening her body. It is mainly through her smiling eyes that she expresses love. Her quivering lips, sometimes, show her agitation.

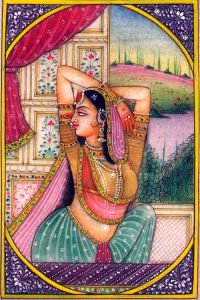

The courtesans on the other hand should be painted with vermilion or emerald color, moon-like complexion or dark like the petals of blue-lotus. Her dress should be unrestrained, designed to excite and evoke erotic feelings. She should be painted as a Ruchaka character.

– Ruchakasya tu maanena Veshyaha karya tatha striyaha / Veshyanam uddatham vesham karyam srungara sammatam / 3.42.24 /

The courtesan expresses her desire through alluring side glances; by touching her ornaments; by scratching her ears, while her big toe draws designs on the ground; and, generally by attractive body-gestures. She is also shown as exposing her navel, and partially, her breasts; polishing her nails; lifting up her arms ; and, tying her hair.

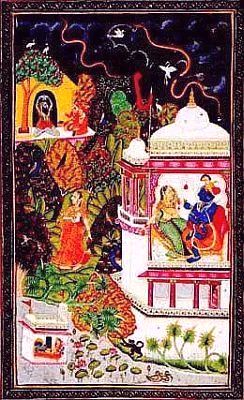

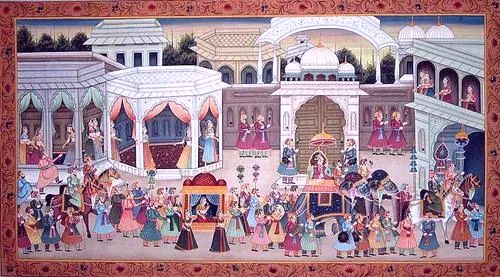

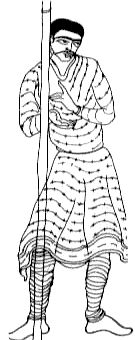

9. Drista – those things visible

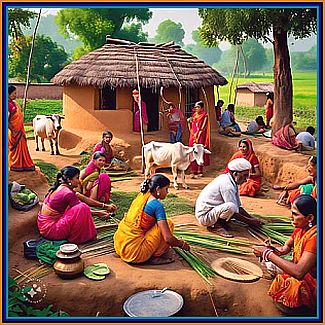

9.1. The text then goes to describe in great detail the characteristic appearances of country folk, the nobility, widows, courtesans, merchants, artisans, soldiers, archers, door-keepers, wrestlers, monks , mendicants , bards , musicians , dancers and others. Vivid descriptions of their dresses, movements, habits, and features peculiar to their class are given in Chitrasutra. They make a very interesting reading.

9.2. The text also describes the characteristics of different tribes and castes as distinguished by their complexion; noticeable physical features, costumes and habits.

9.3. The Chitrasutra instructs things that are usually visible should be well represented; resembling what is ordinarily seen in life. The aim of painting is to produce a credible resemblance; but not to merely copy. Persons should be painted according to their country; their colour, dress, and general appearance as observed in day-to-day life . Having well ascertained the person’s country, region, occupation, age and his status in life; his other details such as his seat, bed, costume, conveyance, stance, and his gestures should be drawn.

[The Chitrasutra explores this subject in great depth detailing characteristics of persons hailing from various regions and occupations. It is rather too detailed to be posted here. I have posted a summary of that, along with few other issues, separately, in the next article.]

10. Features of the Chitra

10.1. General

There is a detailed enumeration of the features of the images of deities, kings and other class. The Chitrasutra also makes some general remarks of such paintings; and says:

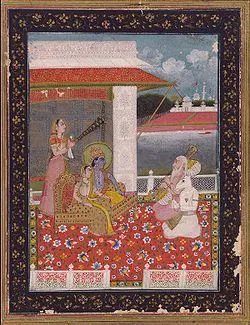

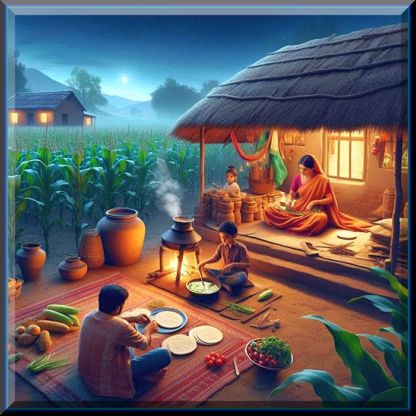

A painting drawn with care pleasing to the eye, thought out with great intelligence and ingenuity and remarkable by its execution beauty and charm and refined taste and such other qualities yield great joy and delight.

A painting without proper position, devoid of appropriate rasa, of blank look, hazy with darkness and devoid of life movements or energy (chetana) is considered inauspicious.

A painting cleanses and curbs anxiety, augments future good, causes unequalled and pure delight; banishes the evils of bad dreams and pleases the household deity. The place decorated by a picture never looks dull or empty.

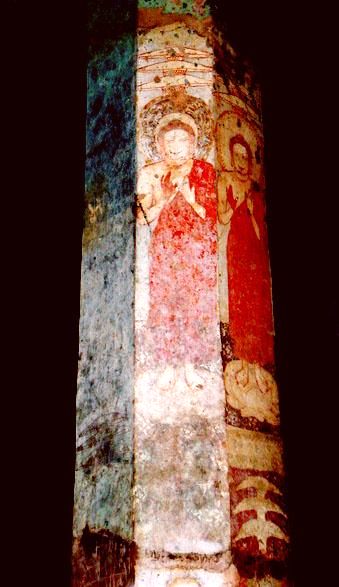

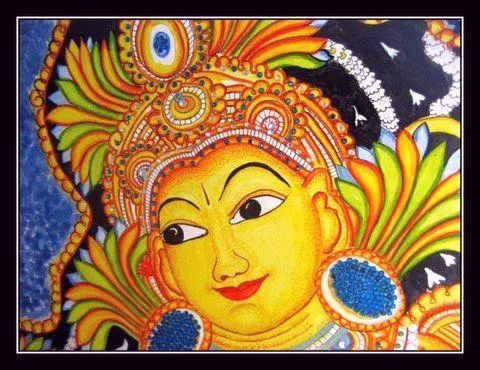

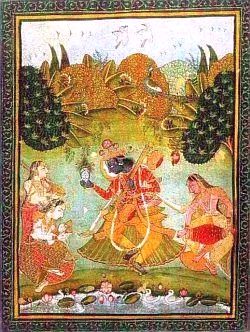

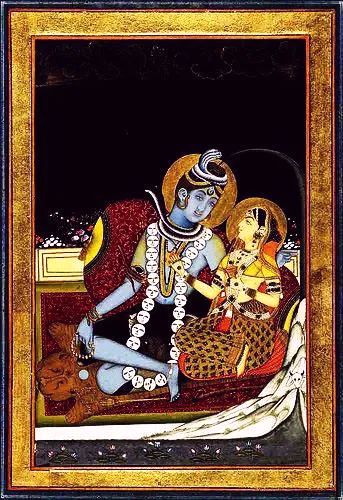

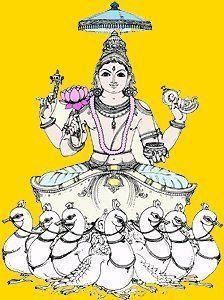

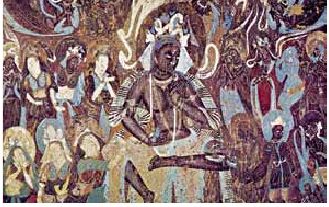

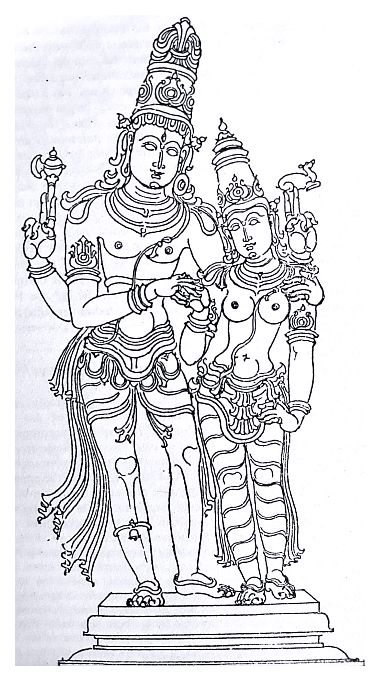

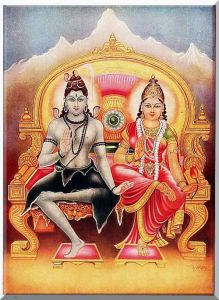

10.1. a. Deities

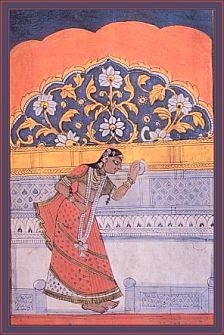

While discussing the image of the deities to be painted, the text says, the painted image should have a pleasing body, a well finished and well proportioned limbs, delicately painted effects of shade and light, facing the viewer. It should be pure and charming adorned by manifold lines and embellishments.

The front view, face, chest and abdomen should remain undiminished; but, it should grow narrow towards the waist from thighs and also from the shoulders. Its shoulders should be broad. The abdomen should neither be shrunk nor bloated.

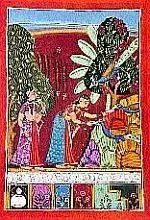

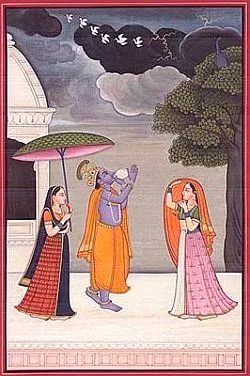

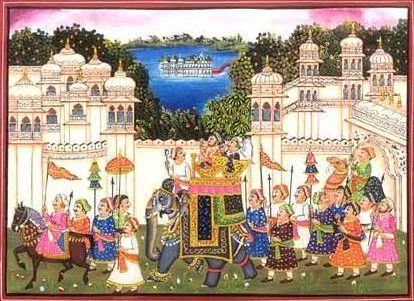

The deities should be drawn wearing strings of garlands and ornamented by crowns, earrings, necklaces, bracelets, ornaments of the upper arms, long girdles reaching up to the ornaments on their feet, and sacred threads with ornaments for the head.

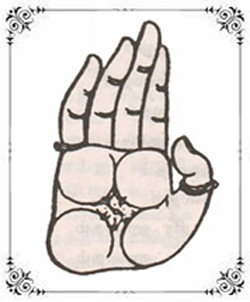

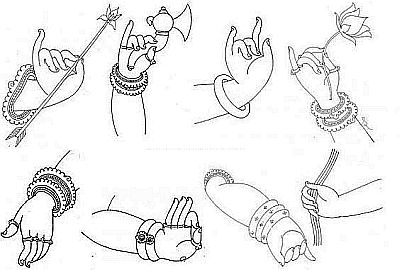

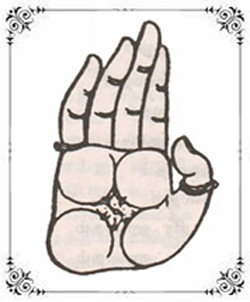

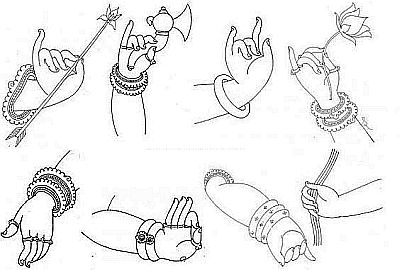

The text says, in general, an image possessed of all auspicious and beautiful marks is excellent from every point of view. Its mudras (gestures of hand and fingers) should be benevolent blessing people with welfare, peace and prosperity. Such an image would add to the wealth, crops, fame and the longevity of life of the worshipers. ” Blessed is the work of art that is endowed with auspicious marks as it is a harbinger of fortune, fame to the country, to the king and to the maker.”

As regards the depiction of great men such as kings and noble persons, the text recommends their images should possess the auspicious lakshanas associated with greatness.

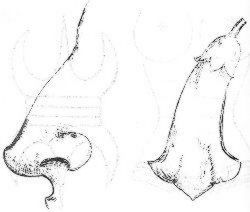

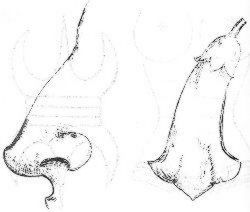

The height of the head should be 12 angulas and its girth 32 angulas. The structure of the face should be divided into three parts: forehead (lalata) – 4 angulas high and 8 angulas wide; nose (nasika)- 4 angulas high, 2 angulas deep and 3 angulas wide; the nostrils being 1 angula broad and 2 angulas wide and, chin (hanu or chibaku) – 4 angulas high.

The Chitrasutra lists typical features of the Hamsa – including that of Urna (tuft of hair on the forehead, between the eyebrows) – ½ angula; and, Usnisa ( a sort of protrusion of the skull) – 4 angula high and 6 angula wide. (Yuva is 1/8 of an angula).

The hair on the head should be made thin, wavy, shiny, with natural glossiness and like the dark blue sapphire. They should be properly ornamented.

As regards the ears, they should be 2 angulas wide and 4 angulas high; the opening auricle being half (1/2) angula wide and 1 angula high.

As for the mouth, the Chitrasutra (36.12-14) mentions that the space between the nose and the lip should be half (1/2) angula. The size of the upper lip is 1 angula; and, the thickness of the lower lip is half (1/2) angula. The mouth is 4 angula wide.

In chapter (36.25-27) the Chitrasutra mentions some bodily measures, as: the nape is 10 angulas high and 21 angula girth. The distance between the nipples is 16 angulas. The space between the chest and the clavicle is 10 angula. And again, in the same chapter (lines 37-42) it mentions: the abdomen measurement is 42 angulas. The navel is 1 angula. The hip is 42 angulas wide. The penis being 6 angula in size.

Chitrasutra (35.13) mentions the distance between the penis and navel as 1 Tala; and the same measure from navel to heart; and from heart to throat.

Apart from that, it also mentions that their hands should reach up to their knees (aa-janu bahu). The hands and feet of a chakravartin should be webbed (jala). The auspicious mark of small circle of hair (urna or tuft of hair) should be shown between their eyebrows. On the hands near the wrist three delicate auspicious lines slender curving should be drawn; as if scratched by a hare.

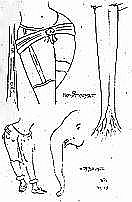

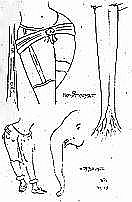

Shoulder to elbow 17 angulas long and 18 angulas in girth; and Elbow to wrist: 17 angulas long and 12 angulas in girth

As per Chitrasutra (36.30-34) : Palm is 6 angula long and 5 angula wide. The middle finger has a measure of 5 angula. The forefinger is half the size of a part less. The fourth finger has the same proportion. The little finger is the smallest among them.

The thumb should be divided into two parts: 4 angulas and 3 angulas. The space between the fingers should be webbed (jaala-anguli)

As regards legs and feet; the Chitrasutra (35.12-13) indicates: the height of the foot up to the end of the ankle should be ¼ tala (3 angulas). The legs- from ankle to the knee- are 2 talas (24 angulas); and, the same are from knees to thighs. Heels -3 angula wide and 4 angula high. Foot 12 angula long and 6 angula wide.

As regards the toes; the big-toe is 3 angula; the next toe is as long as the big-toe; and the other toes are 1/8 shorter than those.

The text also warns, when an image is devoid of these auspicious marks (lakshanas) it would cause destruction of wealth and crops. And, it instructs that such an image should therefore be made with great care, dedication and devotion.

[ The Sukraniti-sara says:

Where the image is intended for worship and is approached in the spirit of a devotee submitting to his deity, or of a servant appearing before his master, the image must be made to adhere, scrupulously, to the forms and characters prescribed by the Shastras. All other images, which are not meant for worship, can be made according to the artist’s own individual preferences.

Sevaya-sevaka-bhabeshu pratima- -lakshanani smritam. ]

As regards the images of the deities, Prof, S K R Rao writes (The Encyclopedia of Indian Iconography) :

10.1. b. Others

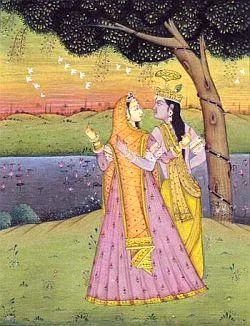

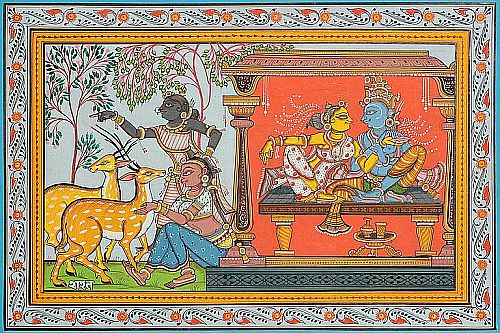

Vidhyadharas should be shown with garlands and ornaments; and accompanied by their wives on either side. They should be shown either on land or in air, with swords in their hands.

10.2. Face:

10.2. a. Deities

The gods should be represented according to Hamsa measure. The face beautiful should be well developed, well finished, and benign marked with all the auspicious lakshanas. The face should be youthful radiating peace and joy. The face should not be triangular or crooked; nor should it be oval or round. The face should never look angry, sad or blank and lifeless . If such expressions creep in, the image should be discarded.

All organs of senses like eyes, nose, mouth and ears should be made visible.

Gods and gandharvas should be represented without crowns but with crests.

10.2. b. Others

All kings should be endowed with auspicious marks. They should be ornamented suitably.

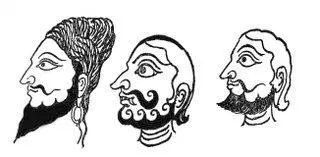

Daityas and danavas (demons) should be made to have frightened mouths, frowning faces round eyes and gaudy garments but without crowns.

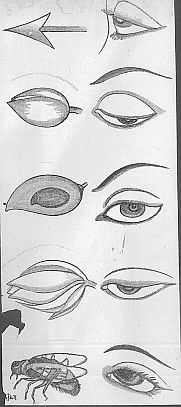

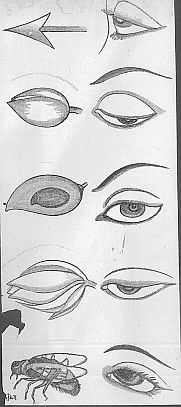

10.3. Eyes:

The text pays enormous importance to the depiction of eyes of a painted figure.

The text informs that the eyes are the windows to the soul; and it is through their eyes the figures in the painting open up their heart and speak eloquently to the viewer.

The section related to the eyes is quite detailed. It gives the measure of each part, as also the descriptions of different types of expressions. The Chitrasutra emphasizes the fact that the fundamental element for a painting to be auspicious is the way that the figure glances – neither upward nor downward; neither too strong nor weak; and, neither angry nor fierce.

Unmilana, ‘opening of the eyes’ , infusing life into the picture by opening the eyes of the figure was the final stage of painter’s work. The importance given to Unmilana is stressed by Vishnudharmottara: Sajiva iva drisyate, sasvasa iva yachchitram tachchitram subhalakshanam (3.43. 21-22) – ‘that is an auspicious painting in which the figures appear to be alive and almost breathe and move’

As regards the measure of the eyes, Chitrasutra (36. 19-22) mentions: ‘the eyes are 1 angula high and 3 angula wide; the black orb (Krishna-mandala) – perhaps the iris- is the third part of the eye. The pupils are the fifth part. The eyebrows are half (1/2) angula thick and 3 angulas long.

The text describes some positions of the eyes : looking straight; half of eyes , nose and forehead are seen ;one eye is seen in full and half of the eyebrow is suppressed; one eye, one eyebrow, one temple , one ear , half of chin are seen etc.

In each case it describes how the eyes and eyebrows should be foreshortened, that is delicately reduced in size or suppressed by artistic means such as gentle lines, delicate shading or by dots.

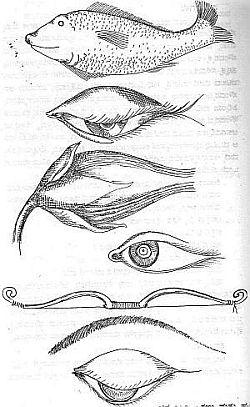

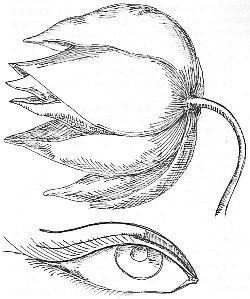

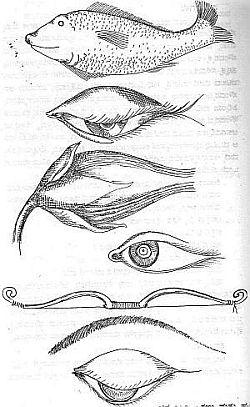

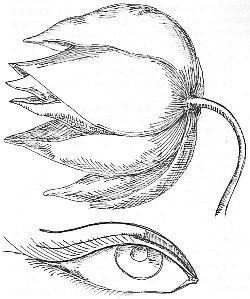

The text describes five basic types of eyes. And, it says the eye could be in the form of a bow (chapakara); or like the abdomen of a fish (matsyodara); or like the petal of blue lotus (utpalaptrabha); or like a white lotus (padmapatranibha) or like a conch (sankhakriti).

Chapakara – 3 yava measure; Matsyodara– 4 yava; Utpalapatrabha – 6 yavas; Padmapatranibha – 9 yavas; and Sankakriti – 10 yavas ( 8 yuvas make 1 angula)

It is explained that the eye assumes the shape of a bow when looking at the ground in meditation or when lost in a thought.

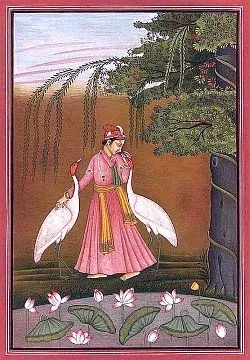

The eye in the shape of fish should be painted in the case of women and lovers.

The eye in the shape of blue lotus is said to be ever calm and look charming with red at the corners and with black pupils, smiling, gentle and ending in long eye lashes sloping at its end.

The eye in the shape of white lotus petal befits a damsel frightened and crying.

A conch like eye suggests angry and woe stricken state.

10.3. a. Deities

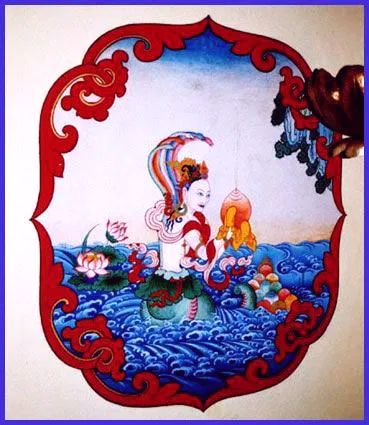

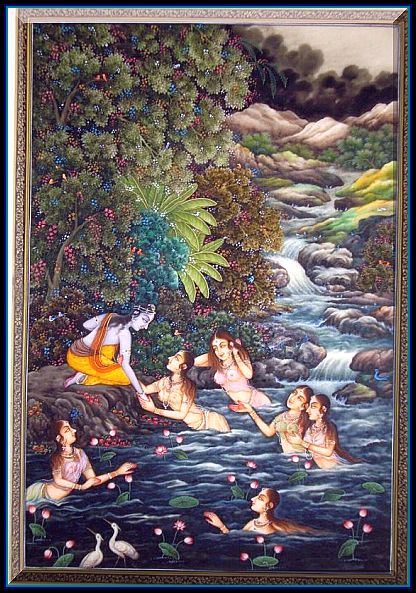

The eyes of gods ( of Padma-patra type) should be wide with black pupils, enhancing the beauty of the divine face, beautiful to look at, charming the mind, smiling and with slight reddish tint at its ends like those of blue-lotus petals, with eyelashes bent at the ends, of equal size, gentle; and fluid and pure like cow’s milk. Such gentle serene eyes and pools of tranquility expressing love and compassion bless the viewers with happiness.

The images with white-lotus petal eyes bring wealth and prosperity. Its eyes should also be even, wide, serene and pleasant to look at. It should have eye-lash sloping at the end and black pupil. Its look should be placid,

Unmilana ‘opening of the eyes’ of the figure is described as the final act; a painting would be complete only with that; and after that, ” an auspicious painting in which the figures will appear to be alive and almost breathe and move’ . Drawing of eyes with delicate lines and giving an expression to the image infuses life into it.

The artist is cautioned to be careful and not to give an upward or downward or sideward look to the deity. An image of god with too small or too wide eyes; or looking depressed, angry or harsh should be discarded. In case such mistakes happen, the deity should be discarded.

The text warns of the ill effects of making a painting of a deity with bad proportions or unacceptable dispositions.

[ In a similar manner, the Shukraniti-sara also warns : An emaciated image always causes famine ; a stout image spells sickness for all ; while the one that is well proportioned, without displaying any bones, muscles or veins, will ever enhance one’s prosperity.

Krisa durbhikshada nityam; sthula rogaprada sada, Gudhasandhi asthi-dhamani sarvada saukha vardhini ]

An image of god should , therefore, be properly made with great care and devotion; and with all the auspicious marks

10.3. b. Others

Daityas and danavas should be given round eyes wide open in fright. Their mouths should also be open as if about to scream. They should be given gaudy ornaments, but no crown.

Representation of human figures with too thick lips, too big eyes and testicles and unrestrained movement are the defects.

10.4. Hair

Hair is an important aspect of the image. It provides it with individuality and it also symbolizes its character.

The text specifies six types of hairstyles: Kuntala (loose) hair; Dakshinavarta (curled towards the right); Taranga (wavy); Simha kesara (lion’s –mane); vardhara (parted) and jatatasara (matted).

10.4. a. Deities

Hair should be represented auspicious, fine resembling deep blue sapphire, adorned by its own greasiness and with endearing curls.

In case of gods, the halo should be drawn around their heads, proportionate to the measurement of the head and colour of the hair. The colour of the halo circle should enhance the glow of the deity. Their body should be devoid of hair. On their faces, they should have hair only on their eyelashes and eye brows.

Gods and gandharvas should be represented without crowns but with crests.

10.4. b .Others

Sages emaciated yet full of splendour should be represented with long stresses of hair clustered on top of their head, with a black antelope skin as upper garment.

The manes of the sages, ancestors and gods should be made to glow like gold and with ornaments consistent with their own colour, outshining all others.

In the case of kings a circle of hair should be drawn auspiciously between their eyebrows. The hair on a king’s body should be drawn one by one.

The respectable people of country and town should be painted with almost grey hair, adorned with ornaments suitable to their status.

Merchants should be represented with their head covered on all sides by turbans.

Wrestlers should be represented with cropped hair, looking arrogant and impetuous.

Widows are to be shown with grey hair , wearing white dress and devoid of ornaments.

The artist should use his skill and imagination in providing appropriate hair-styles to the figures.

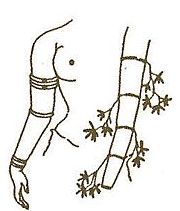

10.5. Arms and hands

In case of gods and kings, arms reaching up to the knees should be strong and tapering resembling the king of serpents or the trunk of an elephant; and should reach up to the knees. Hands should be delicate. The images of the kings should be shown with webbed hands. (I do not know the “why” of this requirement). All kings should be endowed with auspicious marks.

The hands of deities should be delicate and expressive. Their mudras, the gestures by hands and fingers, should be auspicious in benediction.

10.6. Feet

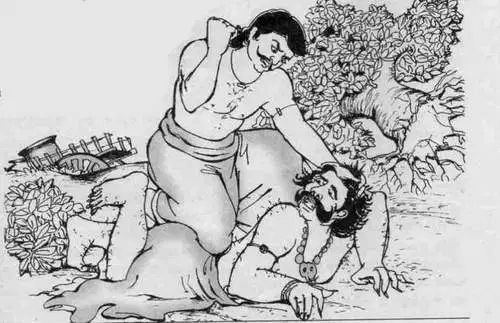

There is an elaborate discussion on the feet-positions, which enhance the mood and message of the image. The positions described include, standing straight in traditional position (sampada); standing with a spans apart (vaisakha) ; half straight with left knee advanced and right knee retracted- suggesting movement (pratyalidha); its counterpart that is right knee advanced (alidha) legs in circular motion (mandala).

The knee-bent positions are related to an archer or a javelin thrower or a swords person etc. (as in pratyalidha or alidha). These positions are improvised to show a fat man running or a pitcher- carrier. The bent knees and feet apart positions are also used to depict the broad hips, flurried loins of the amorous dalliance of a woman.

Accordingly, the gods should always be made beautiful, having gaits like: a lion, bull, elephant or a swan.

[ The Sukranitisara, another text, recognizes five different classes of images: — Nara (human); Krura (terrible); Asura (demoniac); Bala (infantile); and, Kumara (juvenile). Each of these five classes or sets of images (murtis) is assigned a particular scale/proportion (Tala-mana):

Nara murti = ten Talas; Krura murti = twelve Talas; Asura murti = sixteen Talas; Bala murti = five Talas; and, Kumara murti = six Talas.

Here, a Tala is defined as: a quarter of the width of the artist’s own fist is called an Angula or finger’s width. And, twelve such Angulas make one Tala.

It says; besides these given measures there is another measure current in Indian iconography which is known as the Uttama Nava-tala. In this type of images, the whole figure is divided into nine equal parts which are called Talas. A quarter of a Tala is called an Amsa or Unit. Thus, there being four Amsas to each Tala, the length of the whole figure from tip to toe is 9 Talas or 36 Amsas.

The Sukraniti-sara and Brihatsamhita describe the details of the various features of a Nava-tala image.

According to Sukraniti-sara :

Head :

The face of the figure is divided into three equal portions: middle of forehead to middle of pupils; pupils to tip of the nose; and, from tip of the nose to chin.

The Forehead should resemble the form of a bow. The space between the eye-brows and the fringe of hair in front should show the arched crescent form of a slightly drawn bow.

The Eyebrows are to be like the leaves of a Neem tree or like a bow. The various emotions, of pleasure or fear or anger etc., are to be shown by raising, lowering, contracting or otherwise modifying the eye-brow like a leaf disturbed by the wind or a bow under different degrees of tension.

The Eyes are usually described as ‘fish-shaped’. But all similes used to describe the eyes are inadequate; as the range of emotions and thoughts that can be expressed through them are truly endless .

The nose should have the shape of the sesame flower ; and the nostrils are to be like the seed of the long bean. Noses shaped like the sesame flower are to be seen chiefly in the images of goddesses and in paintings of women. In this form, the nose extends in one simple line from between the eyebrows downwards, while the nostrils are slightly inflated and convex like a flower petal.

Parrot-noses are chiefly for the images of gods and male figures. In this type ; the nose, starting from between the eyebrows rapidly gains in height and extends in one sweeping curve towards the tip, which is pointed, while the nostrils are drawn up towards the corners of the eyes. Parrot-noses are invariably associated with heroes and great men, while, among female figures, they are to be seen only in the images of Devi .

Lips, being smooth, moist and red in color, are to resemble the Bimba fruit. The red and luscious Bandhuka flower should admirably be adapted to express the formation of the lower and upper lips.

The Chin should have the form of the mango-stone. As compared to the eyebrows, the nostrils, the eyes or the lips, the chin is more or less inert; being scarcely affected by the various changes of emotion which are so vividly reflected in the other features. It has therefore appropriate to compare the chin to the inert stone of a fruit, while the others to the living objects like flowers, leaves, fish, etc.

The ear is also a comparatively inert portion of human face, and, its shape is compared to the letter ला ( La in Sanskrit ) .

Neck:

The Neck is supposed to exhibit the form of a conch, the spiral turns at the top of a conch being often well simulated by the folds of the neck. Besides, as the throat is the seat of the voice the analogy of the conch is well suited to express the function, as well as the form of the neck.

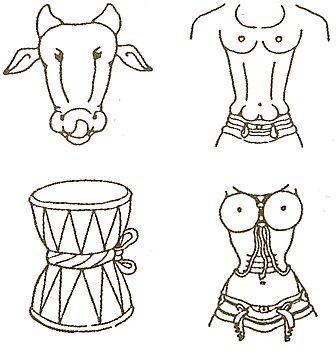

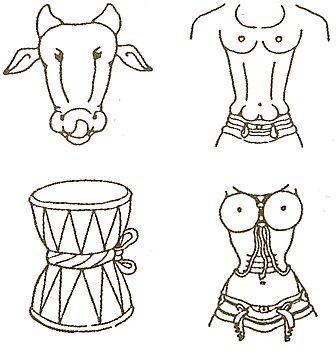

Trunk

The Trunk, from just below the neck to the abdomen, is to be formed like the head of the cow; suggesting the strength of the chest and the comparative slimness of the waist as well as the loose and folded character of the skin folding near the abdomen.

The middle of the body should resemble in shape a Damaru (Hour-glass formation); and, the lion’s waist (Simha kati).

Arms and hands

The, arms are to resemble Elephant’s trunk; strong and supple.

The Forearms, from the elbows to the base of the palms, are to be modeled like the trunk of a young plantain tree; emphasizing the supple symmetry as well as the firmness of the arms.

The Fingers are to resemble the formation of young Champaka flower-buds.

Lower Limbs

The human thigh, in male as well as in female figures, is to be like the trunk of the plantain tree, simulating its smoothness, strength and firmness of build.

The knee-cap should compare to the shell of a crab

The Shins are to be shaped like fish full of roe.

And, generally, the Hands and Feet should have a resemblance to the lotus or the young leaves of plants .

***

As regards the measures and proportions of various features of a Nava-tala image, the Sukraniti-sara and Brihat-samhita prescribe :

From the crown of the head to the lower fringe of hair = 3 Angulas in width; forehead = 4 Angulas ; nose = 4 Angulas ; from tip of nose to chin = 4 Angulas; and , neck = 4 Angulas in height; eye-brows = 4 Angulas long and half an Angula in width; eyes = 3 Angulas in length and two in width ; pupils = one third the size of the eyes ; ears = 4 Angulas in height and 3 in width. Thus, the height of the ears is made equal to the length of the eye-brows.

Palms = 7 Angulas long’ the middle finger = 6 Angulas; the thumb = 3 Angulas, extending to the first phalanx of the index finger.

The thumb has two joints or sections only-, while the other fingers have three each. The ring finger is smaller than the middle finger by half a section; and, the little finger smaller than the ring finger by one section, while the index finger is one section short of the middle.

The feet should be 14 Angulas long; the big toe= 2 Angulas; the first toe = 2 ½ or 2 Angulas; the middle toe = 1 1/2 Angula; the third toe = l ½ Angula ; and , the little toe = l ½ Angula.

Female figures are usually’ made about one Amsa shorter than males.

The proportions of child-figures should be as follows:—the trunk, from the collar-bones below, should be 4 ½ times the size of the head. Thus the portion of the body, between the neck and the thighs is twice and the rest 2 1/2 times the size of the head. The length of the hands should be twice that of the face or the feet.

***

Prof. Ordhendra Coomar Gangoly (1881-1974), popularly known as O.C. Ganguly, one of the foremost authorities on Indian Art, remarks:

The Talas given here (Sukranitisara and Brihat-Samhita) do not exhaust the various measures current in Indian sculpture. In the 4th chapter of the Sukrnniti Sara as also in the chapter on Pratima lakshana of the Brihat Samhita measurements are given for the average human body according to which the average male figure is stated to be eight times the face which is represented by one Tala.

Any height for a human ‘male, which is less than the eighth measure is conceived in the Sukranitisara as dwarfish or below the average.

The average human female figure is given as of the seventh measure (Sapta-Tala).

The average infant figure is laid down as of the fifth measure (Pancha-tala).

The measures higher than the Asta Tala are reserved for the images of gods ;, demons, Rakhsas and other super-human beings.

Thus the image of the goddess according to the Sukranitisara is always in the ninth measure (Nava Tala smrita Devi).That of the Rakshasas is the tenth measure.

The South Indian manuscripts however differ a little from the Sukranitisara and other works in respect of the rules for the measure of the deities.

But; except in the case of the image of Ganesha and Krishna, all the measures given for the images of the deities are higher than the Asta-tala , the average human measure, the higher measurements suggesting a relatively ‘heroic’ type.

In the South Indian manuscripts each measure is again divided into three different classes e.g. the Uttama (best) Madhyamā [medium) and the Adhama (lowest). Thus the Uttama Dasa-tala is represented by 124 Angulas or parts; the Madhyamā-dasa-tala by 120 parts; and, the Adhama-dasa -tala by 116 parts. Special injunctions are laid down for constructing particular images in a measure specially reserved for them. ]

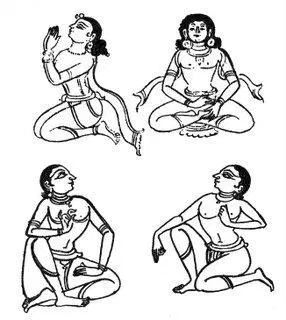

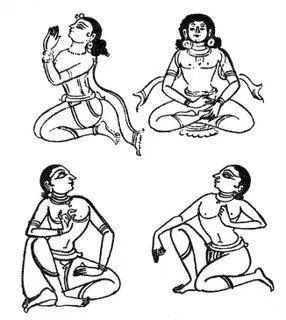

11. Postures and perspectives

Chitrasutra mentions that an image could be presented in any number of positions; but categorizes nine positions as the leading attitudes.

[For more on postures (Sthanas) please click here; and, for more on measures and proportions (Tala-mana) please click here]

11.1. The nine postures, mentioned under, can perhaps be understood as stylized views, as they are the same figure viewed from different angles. That causes portraying the same figure, with altered body- proportions, because some parts are hidden from view while some others are prominent. The ratio of the head with the other limbs of the body has to be altered in accordance with the different postures and view positions (perspectives). Yet, the image should not look disproportionate. That has to be done by manipulating density of light and shades. These indicate that the Chitrasutra had a sound understanding of the spatial perspective of things.

11.2. The various positions and perspectives are achieved by what the Chitrasutra calls – kshaya and vridhi, decrease and increase, which is the art and skill of foreshortening. The positions are:

(i)*. front view (rivagata);

(ii)*.back view (anrju);

(iii)*.bent position – in profile view (sat-chikrat-sarira);

(Iv)*.face in profile and body in three quarter profile (ardha-vilochana);

(v)*.side view proper (paravagata);

(vi)*.with head and shoulder-belt turned backwards (paravritta);

(vii)*.back view with upper part of the body partly visible in profile (prastagata);

(viii)*.with body turned back from the waist upwards (parivrtta);

And

(ix)*.the back view in squatting position with head bent (samanata).

*

11. 3. Then, the Sage goes on to describe the nature of these positions; and how to draw them (39. 1-32)

(1) The front view (rivagata) is, of course, the pre-eminent position amongst those enumerated earlier. It presents a beautiful static posture (rju) of a well-proportioned pleasing body , expertly shaded with artistic display of light and shade . The pure, charming figure, adorned by manifold lines and embellishments, faces the viewer, in full. The front view, face, chest and abdomen should also remain undiminished. The figures grow narrower towards the waist from the thighs, as well as from the shoulders. Their nose-wings and lips appear foreshortened by a fourth part of their width; and their limbs are foreshortened by a third part of their breadth.

(2). For the back view (anrju), the portions on the back should be without foreshortening (lit. diminished limbs)

(3) . The profile view in a bent position (sat-chikrat-sarira) could be very alluring. The bent posture (tiryak), well rounded, but slender and tender limbs all contribute to enhance the charm of the posture. In this profile; only one of the eyes and a portion of the forehead and also of the nose are shown. The one eye that is shown, in the profile, is foreshortened by artistic means; and, the eyebrow is also artistically suppressed (i.e., foreshortened); and is painted with gentle lines. The face is neither straight nor serious; neither black nor shady.

(4) The next position is called ardha-vilochana ‘ – with one eye – face in profile and body in three quarter profile. Here, the one eye in the face of the figure is shown in full; and, half of the eyebrows is suppressed (i.e., one eyebrow is not to be seen). The forehead (the curve of the forehead in half its usual size); and, the curve of one eyebrow are visible. The other visible part is half of the cheek from one side only; while the other half is invisible (lit. suppressed). Half of the usual length (lit. measure) of the lines on the throat and a yava only of the chin are shown. The navel, one angula less than the opening of the mouth, and three quarters (lit. half and half of that half) of the waist and other (parts) should be shown.

(5) The side view proper (paravagata) or Parsvagata is as if it is emerging out of the side or the wall (bhittika) or out of the shade (chhayagata). Only its one side is seen – either the right or the left. Only its one eye, one eyebrow, one temple, one ear; and, half of the chin and the hair should be shown. The figure which is well proportioned should exude grace and sweetness.

(6) . The position with the head and shoulder-belt turned backwards (paravritta) is said to be ” turned back by the cheek” (ganda-paravrtta) whose limbs are not very sharply delineated. It has appropriate measurement in proper places; looking tender; and, artistically foreshortened, kshaya with dark shades in forehead, cheek and arm and also in the throat, (i.e., the parts that are vaguely discernible, as they are lying in the shade) .

(7) Usually, the wall paintings presenting a back view with upper part of the body, partly visible in profile, are tradition-ally called (prastagata)- ‘derived from the back ‘. Such pictures reveal the attractive back frame of the body, showing muscles and joints. In such depictions, only one side is seen; the chest, (one) cheek and the outer corner of the eye are only faintly visible. Such well-proportioned profiles possess qualities like sweetness (madhurya) and grace (Lavanya) .

(8) The Parivrtta is a figure whose upper part of the body is turned back from the waist upwards; and, only a half of it is seen on account of its reversed position. The upper and lower portions of the body, towards the front, are somewhat lost in shade. Its face is tainted with envy; and, the lower half of the body is like that of a rustic; and, its middle is properly foreshortened and made agreeable to the eye.

(9) The back view in squatting position, with the head ; with the buttocks in full view; with the soles of the feet joined; with half of the body faintly seen from above; with the part about the entire waist shown; with the two entire soles shown; with foreshortened lower part of the toes, beautiful all round, well finished, not terrible-looking, with arms visible ; with head and trunk well joined and bent down towards the legs is known by the name of Samanata – methodically bending .

The text cautions; these positions should be drawn with care, accompanied by qualities like mana (proportionate measurement, etc.). And then , it adds; if these nine positions are depicted thoroughly , as prescribed, ‘there is none besides and superior to these’- ( 39. 34-51 )

12. Foreshortening

The concept of foreshortening i.e. the lengthening or the shrinking of the limbs is called Kshaya-vriddhi. It is explained with the help of nine postures (as mentioned above) when viewed from different angles.

The techniques of foreshortening – Kshya (decrease); Vrrddhi (increase) and Pramana (proportionate measurement) – are vital to the art of drawing. These techniques are said to be of two kinds – Chitra (simple) and Vichitra (multicolored). the latter, again is graded into three sorts, according to the quality of the results obtained by proportionate measures: Uttama (full), Madhyama (middling) and Adhama (small).

Further, the techniques of Kshya and Vrddhi are said to be of thirteen varieties, depending upon the nine positions or postures to be depicted in the painting, as mentioned above. The foreshortening will also have to take into account the various positions of the feet and the series of their movements like alidha (the right knee advanced and the left leg retracted); pratyalidha (i.e., with the left knee advanced and the right knee retracted); and, vaisakha (i.e., with feet a span; apart)- as described above.

*

In describing the various kinds of postures, the Chitrasutra advises the display of various kinds of light and shade in and through which the exact position of the postures could be expressed. According to diversity in posture there is a diversity of relation of the different parts of the body which disturbs the normal relation that the head bears to the different limbs. Twelve such postures are described in the Chitrasutra

Foreshortening is achieved, as the text says, by manipulating light and shadows with the aid of coloring, shading with delicate cross lines, stumping and dots; and at the same time maintain the proper proportion (pramana) of the figure and its aspects.

“Weakness or thickness of delineation, want of articulation, improper juxtaposition of colors are said to be defects of painting.”

Daur-balyam sthula-rekhatvam avibhakta tvameva cha / varnanam samkaracha tre chitra-doshaha prakirthitaha / 3.43.18/

*A painting without proper position, devoid of appropriate rasa, blank look, hazy with darkness and devoid of life movements or energy (chetana) is inauspicious.

Sthana -hinam gata-rasam shunya-dristi malimasam /Hina-angam malinam shunyam bhaddam vyadi bhayakulaihi /3.43.22/

“Proper position, proportion and spacing; gracefulness and articulation; resemblances; increasing or decreasing (foreshortening) are the eight good qualities of a painting.”

Sthana Pramanam Bhu-lambo Madhuratvam vibhaktata /Sadushyam Kshaya-vruddi cha gunah astaka idam smrutham /3.43.19 /

Lasativa Bhu-lambo bhibyati iva tatha Nrupa / Hasativa cha Madhuryam Sa-jiva iva drushyate /Sa-svasa iva chitram tat-chitram Shubha-lakshanam /3.43.1-21-22/

The paintings created by the competent artists well-versed in the Shastras, ushers in prosperity; drives away poverty and wretchedness. A painting properly and well positioned, is viewed with wonder and admiration. It ensures a pleasing ambiance, charged with love and happiness. It drives away nightmares; and pleases the Deities resident in the homes. The home indeed looks complete with all the auspicious aspects.

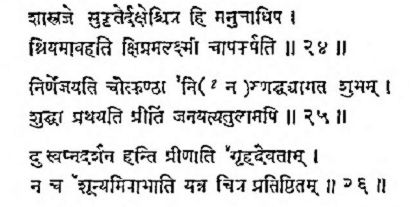

Shastragnaihi su-krutam dakshai Chitram hi Manujaadipa/ Sriya -mavahati kshipram A-lakshmim chapakarshati /3.43.24/

Nirner-jayathi cha utkantam nirudhya-gatam shubhum / shuddam prathayati -pritim janyatya -tulamapi /3.43.25/

Dus-swapna-darshanam hanthi preenathi Griha Daivatham /3.43.26 /

Next:

Chitrasutra continued

Sources and References:

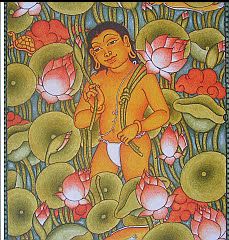

I gratefully acknowledge Shri S Rajam’s sublime paintings; And the other paintings from internet.

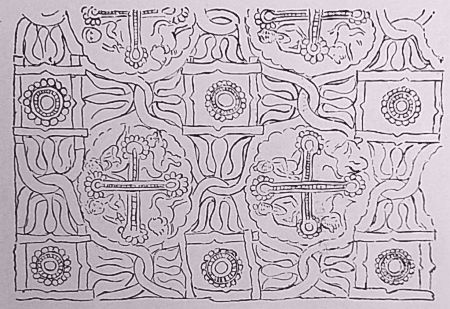

Line drawings from Dr. G Gnanananda’s Brahmiya Chitrakarma Sastram

Citrasutra of the Visnudharmottara Purana by Parul Dave Mukherji

Stella Kramrisch: The Vishnudharmottara Part III: A Treatise on Indian Painting and Image-Making. Second Revised and Enlarged Edition ; (Calcutta University Press: 1928)

Technique of painting prescribed in ancient Indian Texts

http://curiosity-the-key-to-knowledge.blogspot.com/2006/12/technique-of-painting-prescribed-in.html

The “Sarvatobhadra” temple of the Vishnu-dharmottara-purana

https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/dspace/bitstream/1887/2668/1/299

_022.pdf

Problems of Iconometry: Comparing the Citrasūtra with the Citralakṣaṇa by Matteo Martelli

I gratefully acknowledge the illustrations from the works of Shri S Rajam

All other pictures are from internet