Radiant Goddesses

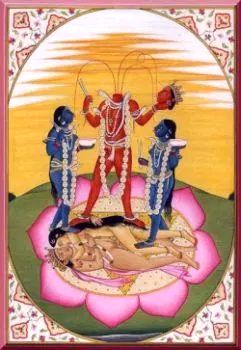

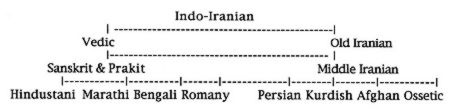

41.1. The group of seven mother-like goddesses, Matrikas, as commonly accepted, consist Brahmi, Vaishnavi, Maheshwari, Kaumari, Varahi, Indrani and Chamunda.

ब्राह्मी माहेश्वरी चैव कौमारी वैष्णवी तथा । वाराही च तथेन्द्राणी चामुण्डा सप्तमातरः ॥

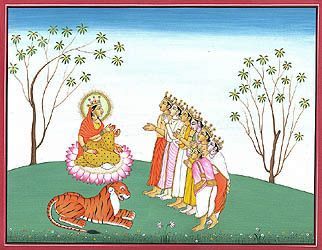

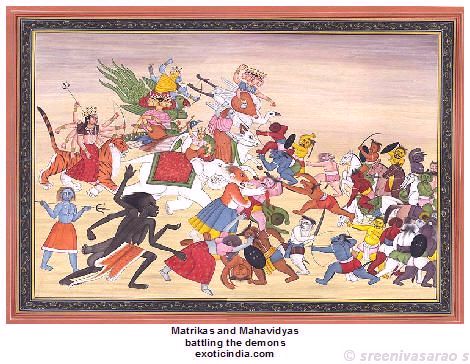

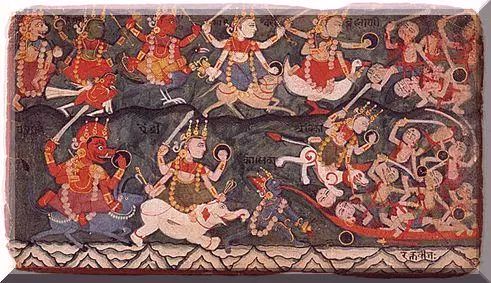

According to a version of their origin, as narrated in Devi Mahatmya, it is said, the Matrka goddesses were created by male Gods in order to aid Mahadevi in her battle against the demons Shumba and Nishumba.

The Matrkas emerge as Shakthis from out of the bodies of the gods: Brahmi form Brahma; Vaishnavi from Vishnu; Maheshwari from Shiva; Kaumari from Skanda; Varahi from Varaha; and Indrani from Indra. They are armed with the same weapons, wear the same ornaments and ride the same vahanas and also carry the same banners as their corresponding male Gods do.

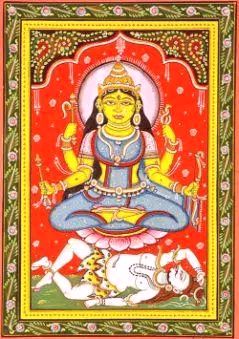

Saptamatrkas as a group indicate transformation of the male identities of gods into goddesses.

These seven mother goddesses, celebrated as a group, are an embodiment of the female principle of prakrti, the counterpart of purusha.

Group composition

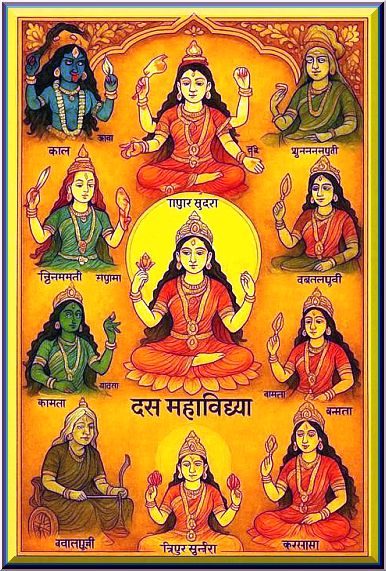

41.2. The Saptamatrka group is, thus, composed of: two Vaishnava Shakthis (Vaishnavi and Varahi); two Shaiva Shakthis (Maheshwari and Kaumari); one Brahmi Shakthi, in addition to Indrani (Aindri) and Chamunda. It is a group of six Deva Shakthis and one Devi Shakthi, making it into an integrated unit of seven.

42.1. Many have attempted to explain the rationale in the composition of Saptamatrka group.

One explanation mentions that the group of seven goddesses was derived from the gods that were considered important during the Gupta period. By then, the major gods – Shiva and Vishnu – had already attained independent – super status within the Vedic pantheon. Brahma was in any case one among the trinity, though a less impressive one. And, Skanda had risen into prominence since the time of Kushanas when he was absorbed into Shiva pantheon; and he developed further during the Gupta era. Varahi the counterpart of Varaha was more popular during the Gupta period than any other avatar of Vishnu. Aindri is the only counterpart of the Vedic gods who by then had lost their importance. Chamunda, of course, represents the principal feminine force.

The omission of the counter part of Surya who was a major god, acceptable to all sects, during the Gupta period is rather surprising. Similarly, of Ganapathi who was just beginning to rise to prominence.

42.2. The Saptamatrkas were earlier connected with Skanda (Kumara), but in later times were absorbed into the sect of Shiva himself. Aptly, the Saptamatrka panel begins with Ganesha, the son of Shiva; and ends with an aspect of Shiva such as Bhirava or Virabhadra. Sometimes, Natesha or Vinadhara – Dakshinamurthy represents Shiva.

The presence of Ganesha at the beginning of the panel, it is explained, is prompted by the faith that Ganesha as the Lord of the Ganas would remove obstacles; help the devotee in his pursuit; and guide him along his endeavour. From the sixth century onwards inclusion of Ganesha in the format became a standard practice. Thereafter, depiction of Ganesha and Shiva, and sometimes along with Skanda, became quite common. For instance, In the Matrka panels at Aihole and Elephanta caves Ganesha and Skanda are shown as child gods along with Shiva.

Thus, in association with Chamunda, the Saptamatrka panel was rendered into a composite unity.

43.1. As regards the presence of Ganesha and Virabhadra at either ends of the Saptamatrka panel, Shri DSampath observes, elsewhere: The Saptamatrikas symbolically represent the seven different aggressive tendencies of the female part of a human being. When unleashed; they tend to destroy the wellness that comes out of a fostering mother. Children below the adolescent age are likely to be influenced by such harmful energies. Those adverse influences breed in kids a sort of ’non- motherly’ destructive attitude. And, these aggressive tendencies (energies) are meant to be contained and held in check by the two male energies: of Vinayaka who was ‘mother- born’ and who regarded all women as mothers; and of Virbhadra who could invoke motherly virtues in any woman. Between the manifestation of rational Vinayaka and the fiery Virabhadra these female energies were to be harnessed.

43.2. The other significant aspect about the Saptamatrka group formation is the order in which they appear in the traditional texts. The order symbolizes the cycle of creation and its cessation; and presents it as the functions of female power-Shakthi.

The order of the Saptamatrka usually begins with Brahmi symbolizing creation. It is often represented by the all-comprehensive primordial Nada Om (pranava).Then, Vaishnavi provides the created world with symmetry, beauty and order. Maheshwari, who resides in the hearts of all beings, breaths in life and individuality. Kaumari, Guru-guha, the intimate guide in the cave of one’s heart, inspires aspirations to develop and evolve. Varahi is the power and aggressive intent to go after enjoyment. Indrani is the sovereignty intolerant of opposition and disorder . Chamunda is the destroyer of delusions and evil tendencies, paving way for spiritual awakening.

[ The number seven was found significant in understanding the composition of human body, which is made of seven types of bodily substances (Saptha-Dhatu).

Ayurveda has the concept of Dhatu-s i.e., Dhatu Siddhantha (theory of tissues formation and differentiation).

Ayurveda classifies the human body into seven constituents, or Saptha-dhatu. These are the elements in the human body that nourish, enable growth and support the body and mind. The seven dhatus are:

-

- Rasa/Twaca-Dhatu: (Plasma/lymph fluid/skin) – covers the body, circulates nutrients, hormones and proteins throughout the body;

- Raktha-Dhatu (Blood); preserves human life by transporting oxygen and nutrients throughout the body

- Mamsa-Dhatu (Muscles); it is the tissue that covers all organs and is related to strength and stability

- Medha-Dhatu (Fat); It is the storage site for excess fat in the body.

- Asthi Dhatu (Bones); it gives a structure and makes the human body strong

- Majja-Dhatu (Bone marrow); it is associated with the nervous system; govern metabolic process in the brain and the spinal cord.

- Shukra-Dhatu (Reproductive fluid or Semen); it is responsible for life, vitality and energy.

**

The seven types of bodily tissues (Saptha-Dhatus) are said to be symbolically associated the Saptha-Matrkas.

Each of the seven Dhatus is said to be ruled by a Matrka:

-

- Brahmi (Rasa/Twaca-skin);

- Maheshvari: (Raktha-blood);

- Kaumari (Mamsa-muscle);

- Vaishnavi (Medha-fat);

- Varahi (Asthi-bone) ;

- Aindri (Majja- bone marrow) and,

- Chamunda (Shukra-semen, vitality and energy)

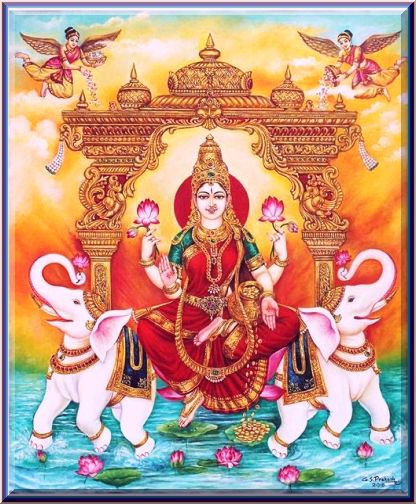

The Matrka-Vaishnavi (akin to Lakshmi), who rules over Medha-Dhatu (fat) and abundance ; and one who assures wealth and prosperity is traditionally placed at the center of the Matrka panel.]

*

43.3. The most important significance of Saptamatrka symbolism is the implication of the cyclical universal time and its cessation. In the standard versions, Brahmi symbolizes creation; Vaishnavi the preserver occupies the central position flanked by three goddesses on each side. The cycle of periodic time ends with dissolution symbolized by Chamunda. She is the only Devi Shakthi among the Matrkas. She is at times depicted as one who exists beyond death and time. Kalabhairava, who usually appears at the end of the Saptamatrka panel, symbolizes liberation from cycle of birth and death. Thus, it is said, Saptamatrkas epitomize the process of creation, preservation and death; and, the final liberation that takes one beyond time. This is in tune with the Shaktha theology which rationalizes creation, preservation and destruction of the world as the functions of female power-the Shakthi.

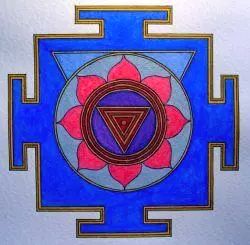

In Sri Chakra

44.1. In the Sri Chakra, Chatushra the outermost four-sided square field (bhupura – the earth stretch) known as Trailokya-mohana-chakra is composed of three lines which make way for four doors (dwara) on four directions. These sets of lines are also described as the layers of the enclosure wall which surround the city of the Devi (Tripura). The three lines are understood to represent three planes of existence: attainments, obstructions and powers. The three planes are related to the body-mind complex and its experiences with the world around. The associated goddesses are worshiped by the aspirant seeking protection and guidance as he/she enters into Sri Chakra.

44.2. Along the outer line the ten Siddhis (attainment-divinities) reside; along the middle line reside eight Matraka the Mother-like powers; and, and along the inner line are the ten Mudra-devatas (goddess who empower).

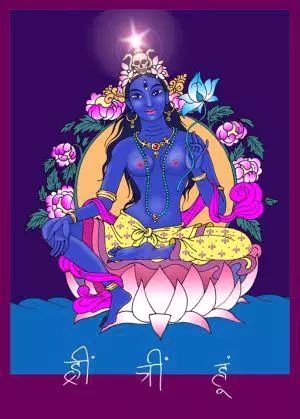

44.3. As said; the middle wall (line) is guarded by the Matrkas. The wall is red in colour; the red of the rising sun, signifying the Rajo guna of the Matrkas who are said to represent eight types of passions. The Matrkas, according to Bhavanopanishad of Bhaskararaya Makhin, are said to be dark blue in color; wearing red garments; carrying a red lotus and a bowl filled with nectar.

44. 4. The Bhavanopanishad (9) recognizes Matrkas as eight types of un-favorable dispositions, such as: desire, anger, greed, delusion, pride, jealousy, demerit and merit.

Tantra-raja-tantra (36; 15-16) expands on that and identifies :

- Brahmi with desire (Kama);

- Maheshwari with the tendency to degenerate and dissipate (krodha);

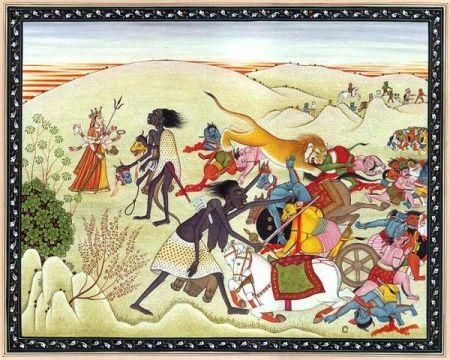

- Kaumari with youthful longings to enjoy (lobha);

- Vaishnavi with power to fascinate and delude (moha);

- Varahi with pride and arrogance (mada);

- Indrani with jealousy and envy (matsarya);

- Chamunda with urge to sin (papa) and hurt (abhichara); and ,

- Mahalakshmi with doing good (punya) with other than altruistic reasons.

Matrkas who rule over such un-favourable dispositions are worshipped by the Sadhaka with prayers to suppress and overcome the evil tendencies that obstruct his progress.

44.5. According to Khadgamala (vamachara) tradition of Sri Vidya, the eight Matrkas are located along the wall (four at the doors and four at the corners) guarding the city (Tripura) on all eight directions:

- Brahmi on the West;

- Maheshwari on the North;

- Kaumari on the East;

- Vaishnavi on the South;

- Varahi on North-west;

- Aindri on the North-east;

- Chamunda on the South-east; and,

- Mahalakshmi on the South-west.

Please see the figure below.

44.6. As you may notice, the Matrkas of Rajo–guna who govern over human passions are on the outer layer of the Sri Yantra. This signifies that the Sadhaka should get past passions and prejudices before he enters into the city of the Devi.

Matrka

Brahmi

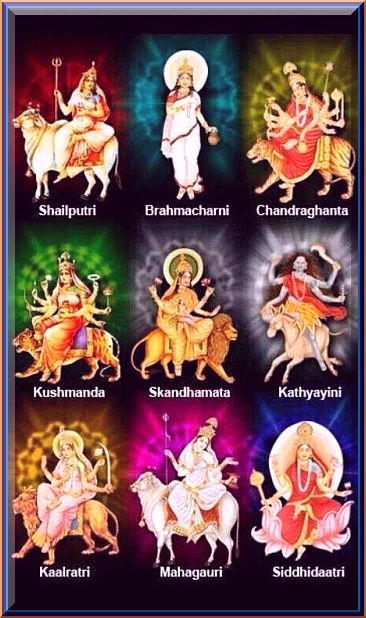

45.1. Brahmi or Brahmani the first Matrka is the shakthi of Brahma. She is depicted in bright golden complexion, having four faces and four hands. In her back- right hand, she carries a kamandalu and in the back- left hand an Akshamala. The front- right hand gestures Abhaya and the front- left hand bestows Varada. She is seated under a Palasha tree, upon a red lotus. She is adorned in a mellow bright garment (Pitambara) and various ornaments; and, has on her head karanda-makuta. Her vahana and her emblem is the swan (Hamsa): (Amsumadbhedagama and Purva-karanagama).

45.2. The Vishnudharmottara describes Brahmi as having six hands. Of the three hands on the left, the lowest one gestures Abhaya; while the other two hold Pustaka (book) and kamandalu. On her right, the lowest hand gestures Varada; while the other two hold Sutra and Sruva (a ladle for pouring oblations of ghee into fire). It also mentions deer-skin as a part of her attire.

Aum Dhevee Brahmani Vidmahe

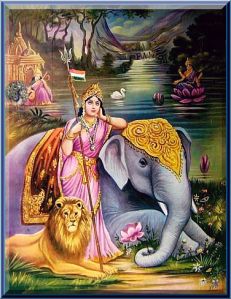

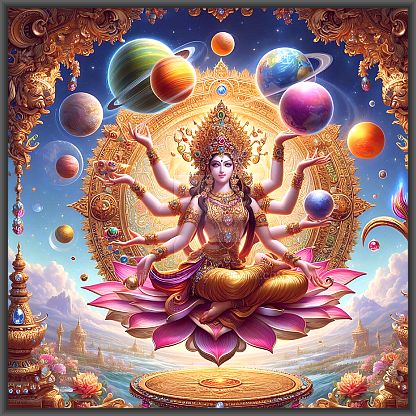

Vaishnavi

Vaishnavi Vishnu saddasi Garudapasi samsthitha

46.1. Vaishnavi is the Shakthi of Vishnu. She is seated upon a lotus, under a Raja – vriksha, the great tree. She is dark in complexion. She has a lovely face, pretty eyes and wears a bright yellow garment. Her head is adorned with kirita-makuta. She is richly decorated with ornaments generally worn by Vishnu. She wears the Vanamala, the characteristic garland of Vishnu. The emblem on her banner as well as her vahana is the Garuda. When depicted with four arms, she carries in one of her hands the chakra and in the corresponding left hand the shankha; her two other hands are held in the Abhaya and the Varada mudra. (Devi-Purana and Purvakaranagama)

46.2. The Vishnudharmottara states that like Brahmani, Vaishnavi also has six hands; the right hands are characterized by the Gada, Padma and Abhaya and the left ones by Shankha, Chakra and Varada.

Aum Thaarksh Yathwajaaya Vidmahe

Chakra Hasthaya Dhimahee

Thanno Vaishnavi Prachodayath

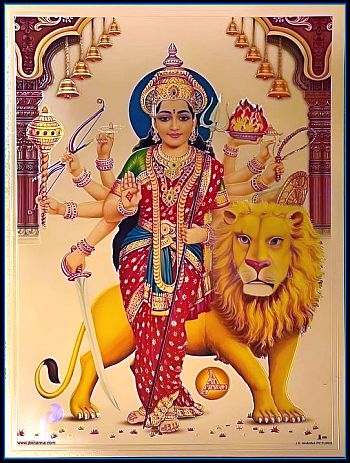

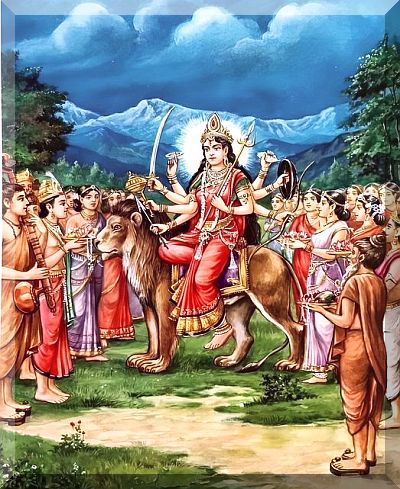

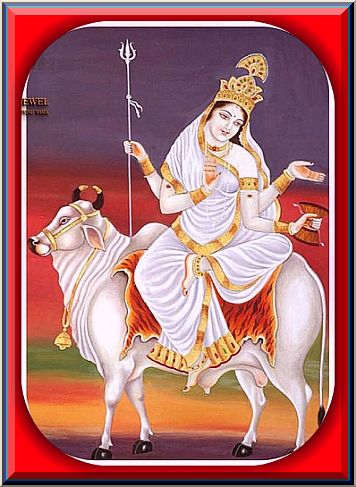

Maheshwari

Maheshwari prakarrtavaya Vrishabasana samasthitha

Kapala shula khatvanga varada cha chaturbhuja (Rupamandana)

47.1. Maheshwari also known as Raudri, Rudrani and Maheshi is the Shakthi of Shiva. She is white in complexion; and has three eyes. She is depicted with four arms; two of which are in the Varada and the Abhaya mudra, while the other two hands hold the Trishula and Akshamala .Sometimes, she is also shown holding Panapatra (drinking vessel) or axe or an antelope or a kapala (skull-bowl) or a serpent. Her banner as well as the vahana is Nandi (bull). She wears snake-bracelets; and Jata -makuta on her head.

47.2. The Vishnudharmottara mentions that Goddess Maheshwari should be depicted with five faces, each possessing three eyes and each adorned with jata-makuta crown and crescent moon. Her complexion is white. She is depicted with six arms. In four of the hands she carries the Sutra, Damaru, Shula and Ghanta. The other two hands gesture Abhaya and Varada mudra. Her banner also has the Bull for its emblem.

Aum Vrushath-vajaaya Vidmahe

Miruga Hasthaya Dhimahee

Thanno Maheshwari Prachodayath

Aindri

Indrani Indra-sadrishi vajra-shlu-gada dhara

48.1. Aindri, also known as Indrani, Mahendri, Shakri and Vajri, is the shakthi of Indra; her complexion is dark- red. She is seated under the Kalpaka tree. She is depicted as having two or three or a thousand eyes, like Indra. The Indrani is depicted with four arms. In two of her hands she carries the Vajra (thunderbolt) and the shakthi; while the other two gesture Varada and Abhaya mudra. Sometimes, she is shown holding Ankusha (goad) and lotus. She is richly ornamented; and adorned with Kirita Makuta. Her vahana as well as the emblem on her banner is the charging elephant. (Devi-purana and Purvakaranagama)

48.2. According to the Vishnudharmottara, Indrani should be depicted with thousand eyes; and she should be of golden colour. She should have six arms, four of the hands carrying the sutra, Vajra, Kalasa (a pot) and Patra (a drinking cup) and the remaining hands being held in Abhaya and Varada mudra.

Aum Gajath-vajaayai Vidmahe

Vajra Hasthaya Dhimahee

Thanno Indrani Prachodayath

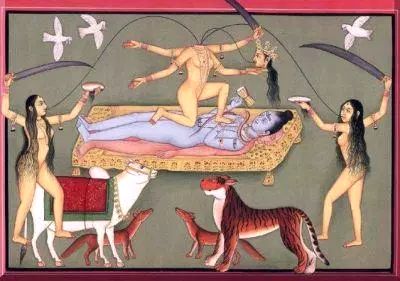

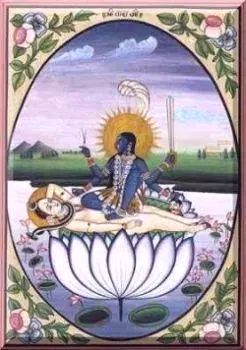

Varahi

49.1. Varahi is the Shakthi of Varaha, an incarnation of Vishnu. The Markendeya Purana praises Varahi as a granter of boons and the regent of the northern direction. Varahi is shown with the face of a boar and having dark complexion resembling the storm cloud. She is sometimes called Dhruma Varahi (dark Varahi) and Dhumavati (goddess of darkness). Varahi is seated under Kalpaka tree. And, her Vahana as well as the emblem on her banner is an elephant. She wears on her head a Karanda Makuta and is adorned with ornaments made of corals. She wears on her legs Nupura-anklets. She wields the hala and the shakthi and is seated under a Kalpaka tree. The PurvaKaranayama says that she carries Sarnga-Dhanush (bow), the hala (plough) and musula (pestle) as her weapons.

49.2. In other descriptions, Varahi is identified as the Yami, the shakthi of Yama. Varahi is described holding a Danda (rod of punishment) or plough, goad, a Vajra or a sword, and a Panapatra. Sometimes, she is said to carry a bell, chakra, chamara (bunch of yak’s hair used as flywhisk) and a bow; and riding a buffalo.

49.3. In the Raktabija episode of Devi Purana, Varahi is described as having a boar form, fighting demons with her tusks while seated on a preta (ghoul).

49.4. To this description the Vishnudharmottara adds that Varahi has a big belly and six hands, in four of which she carries the Danda (staff of punishment), khetaka (shield), khadga (sword), and pasha (noose); while the two other hands gesture Abhaya and Varada mudra-s.

49.5. When depicted as part of the Sapta-Matrika group, Varahi who is called Panchami (the Fivefold One) is always in the fifth position in the row of Matrikas. It is explained; Varahi summarizes fivefold elements: water, fire, earth, air and ether. Each of these elements is related to lion, tiger, elephant, horse and Garuda (bird-human) which serve as vehicles of Vishnu. Varahi as the shakthi of Vishnu is depicted with head of a boar having three eyes and eight arms holding in her six hands a discus, conch-shell, mace, lotus, noose and plough; while the other two hands gesture Abhaya and Varada mudra-s. She is depicted as riding, alternatively, a Garuda, a tiger, a lion, an elephant or a horse.

49.6. In the Sri Vidya tradition, Varahi occupies a special position as Para-Vidya (superior power) .She is described as Dandanayika or Dandanatha – the commander-general of goddess Tripurasundari’s army. She is also the chief- counsellor (maha-mantrini) to the Devi. Varahi is also said to stand in a ‘father’ position to the Devi, while Kurukulla is the ‘mother’.

49.7. Varahi has presence in the Buddhist Tantric lore, also. There, she is described as the fierce Vajra-varahi or Vajra-yogini.

Aum Varaaha-muhi Vidmahe

Aanthra-shani Dhimahee

Thanno Yamuna Prachodayath

Kaumari

50.1. Kaumari also known as Kumari, Karttikeyani and Ambika is the power of Kumara or Skanda; the war – god .Her depictions resemble that of Kumara. She is ever youthful, representing aspirations in life. Kaumari is also regarded as Guru-Guha the intimate guide who resides in the cave of one’s heart. She is shown seated under a fig tree (Oudumbara) riding a peacock, which is also her emblem. Her complexion is golden yellow; and is dressed in red garments. She wears garland of red flowers. Kaumari has four hands; and carries Shakthi and Kukkuta (cockerel) or Ankusha (goad). The other two hands gesture Abhaya and Varada mudras. She is adorned with a makuta said to be bound with Vasika or Vachika. She embodies ideas of valour and courage. (Purvakaranagama and Devi Purana).

50.2. According to the Vishnudharmottara, Kaumari should be shown with six faces and twelve arms; two of her hands gesturing Abhaya and Varada mudras. In her other hands she carries the Shakthi, Dhvaja, Danda, Dhanus, Bana, Ghanta, Padma, Patra and Parasu. Each of her heads has three eyes; and is adorned with karanda-makuta.

Aum Sikid-vajaaya Vidmahe

Vajra Hasthaya Dhimahee

Thanno Kowmari Prachodayath

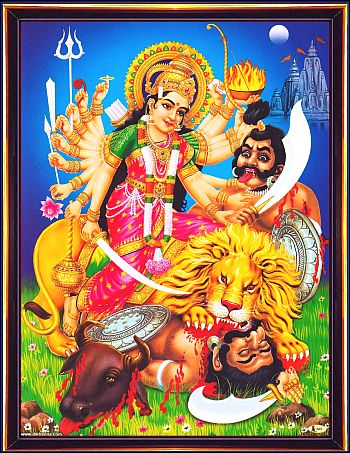

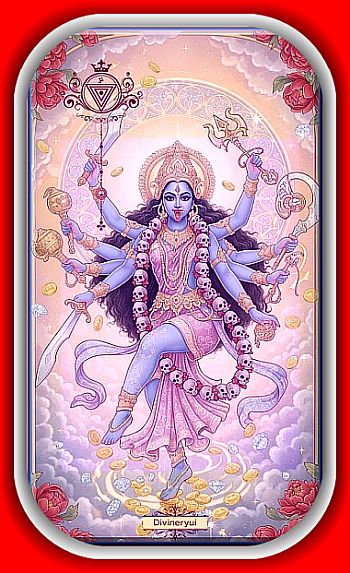

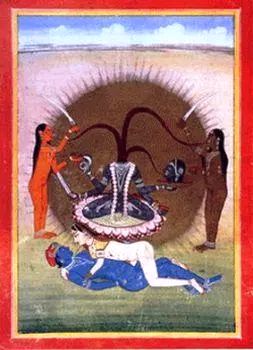

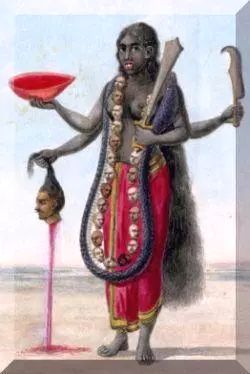

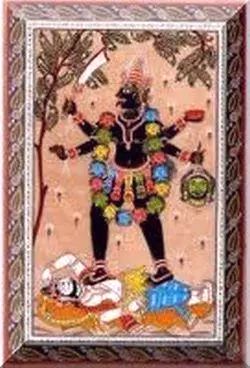

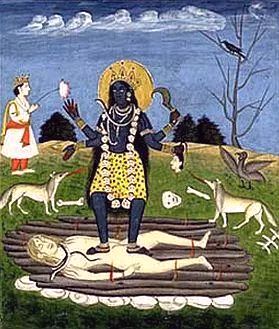

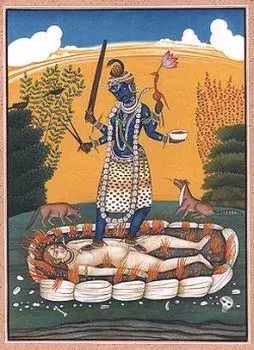

Chamunda

Dastrala kshindeha chagatrakarshana bhimrudani

51.1. Chamunda also known as Chamundi; and, Charchika is the Shakthi of Devi (Chandi). She is the destructive form of Devi; and is similar in appearance and habits to Kali. Devi Mahatmya recounts that in the course of her fight with demons Chanda and Munda, Devi created from her forehead the terrible form of Chamunda.

There are , however, alternate explanations.

According to the text of the Devi Mahatmya, Kali is celebrated as Chamunda after she overpowers and beheads Chanda and Munda.

śiraścaṇḍasya kālī ca gṛhītvā muṇḍameva ca । prāha pracaṇḍā aṭṭahāsa miśra mabhyetya caṇḍikām ॥ 7.23॥

The Devi, then, declares that since Kali presented her with the heads of these two demons, she would henceforth be renowned in the world as Chamunda – cāmuṇḍeti tato loke khyātā Devī bhaviṣyasi .Thereafter in the text, Kali and Chamunda become synonyms.

Yasmāc-Caṇḍaṃ ca Muṇḍaṃ ca gṛhītvā tvamupāgatā । Cāmuṇḍeti tato loke khyātā Devī bhaviṣyasi ॥ 7.27॥

Bhaskararaya Makhin, however, interprets the term Chamunda, differently, as: ‘chamum, ‘army’ and lati, ‘eats’; meaning that Chamunda is literally ‘she who eats armies’—a reference to Kali as Chamunda who drinks the blood of the army of the demon Raktabija.

jaghāna raktabījaṃ taṃ cāmuṇḍā apītaśoṇitam । sa papāta mahīpṛṣṭhe śastra saṅghasam āhataḥ ॥ 8.61॥

He regards the Mahadevi Chamunda, in her integrated form (Samasti), as of the nature of the Brahman- Brahma-svarupini. She combines in herself her other diversified (Vyasti) forms of Mahalakshmi (Aim); Mahasarasvathi (Hrim); and, Mahakali (Kilm).

51.2. Coming back to Chamunda as as a Matrika, unlike other Matrikas, Chamunda is an independent goddess. She is also praised as the fertility goddess of Vindhya Mountains She is also associated with Yama.

The descriptions of Chamunda are varied.

One of the descriptions of Chamunda mention of her as a goddess of terrible countenance, black and scowling, with drawn sword and lasso, holding a Khatvanga, wearing a garland of severed heads (munda-mala) suspended by their hair. Chamunda is clad in a tiger skin, hungry and emaciated, mouth hideously distorted and the tongue protruding out. She sits upon a seat made of three skulls; and has a cadaver for footrest. She plucked off the heads of Chanda and Munda and presented both heads to Kausiki.

51.3. In other descriptions, a bear’s skin is tied over Chamunda’s clinging skirt, with its head and legs dangling on her back. She wears the skin of an elephant as a cape and grasps two of the animal’s feet in her uppermost hands. In her other hands she brandishes an array of weapons and awe-inspiring objects.

51.4. Chamunda is often depicted as dark in colour with very emaciated body, having three eyes, sunken belly and a terrifying face with a wide grin. Her hair is abundant and thick and bristles upwards. Her abode is under fig (oudumbara) tree. On her sunken chest, swings garland of skulls (mundamala) in the manner of a Yajnopavita. She wears a very heavy jata-makuta formed of piled, matted hair tied with snakes or skull ornaments. Sometimes, a crescent moon is seen on her head. Her garment is the tiger skin. Chamunda is depicted adorned by ornaments of bones, skulls, serpents and scorpions, symbols of disease and death. And in her four hands she holds damaru (drum), trishula (trident), khadga (sword) and panapatra (drink-vessel). She is riding a Jackal; or is seated in Padmasana or is standing on a corpse of a male (shava or preta).She is accompanied by fiends and goblins. She is surrounded by skeletons or ghosts and beasts like jackals, who eat the flesh of the corpse that the goddess sits or stands on. The jackals and her fearsome companions are sometimes depicted as drinking blood from the skull-cup or blood dripping from the severed head.

51.5. Purva-karanagama mentions that Chamunda, red in colour, should be depicted with wide open mouth set in a terrifying face having three eyes. Her socket eyes are described as burning like flames. She has a sunken belly; and, wears on her head the digit of the moon as Siva does. She has four arms. The black or red coloured Chamunda is described as having four, eight, ten or twelve arms, holding a Damaru (drum), trishula (trident), sword, a snake, skull-mace (khatvanga), thunderbolt, a severed head and panapatra (drinking vessel, wine cup) or skull-bowl (kapala), filled with blood, an urn of fire. She wears in her ears Kundla-s made of Conch shell (Sankha Patra). Her Vahana is an Owl; and the emblem of her banner an Eagle.

51.6. Vishnudharmottara describes Chamunda as having a terrific face with powerful tusks and seated upon a male corpse. She has a very emaciated body and sunken eyes and ten hands. The belly of this goddess is thin and apparently empty. She carries in her ten hands: Musala, Kavacha, Bana, Ankusha, Khadga, Khetaka, Dhanus, Danda and Parasu.

Aum Pisaasath-vajaaya Vidmahe

Soola Hasthaya Dhimahee

Thanno Kali Prachodayath

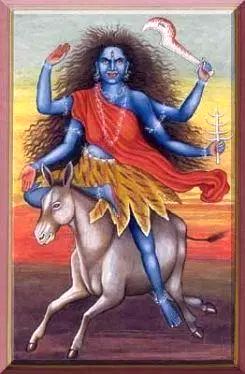

Narasimhi

52.1. In the Devi Mahatmya, the Saptamatrkas (the seven Matrkas) mentioned are: Brahmi, Maheshwari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Indrani and Chamunda. At times, Narasimhi is mentioned in place of Chamunda. In some versions, the Martkas are counted as eight (Ashta-Matara) by including Narasimhi. There is also a tradition of Ashtamatrikas, eight Matrkas, which is prevalent in Nepal region. In Nepal, the eighth Matrka is Maha-Lakshmi (she is different from Vaishnavi). Narasimhi does not figure in the lists of Devi Purana and in Nepal.

52.2. Narasimhi or Narasimhini or Narasimhika with the face of a lion, fierce claws and four arms is the shakthi of Narasimha. She is said to have came out from the heart of the Devi. As Matrka, Narasimhi is regarded as an independent deity; and not as a female counterpart of Narasimha. In The Vaishnava School, she is believed to be an aspect of Lakshmi who pacified the ferocious Narasimha.

52.3. In Devi Mahatmya, Narasimhi accompanies Devi in the fight against demons Shumbha and Nishumba. There Narasimhi is described as a ferocious warrior: Narasimhi arrived there, assuming a body like that of a Narasimha throwing the stars into disarray, bringing down the constellations by the toss of her mane (DM: 20) . And, Narasimhi, filling all the quarters and the sky with her roars, roamed about in the battle, devouring other great asuras torn by her claws (DM: 37).

52.4. Narasimhi is sometimes identified with Pratyangira who is endowed with four arms and a face as terrible as that of a lion. Her head is that of a male lion and her body is that of a human-female. Her hair stands erect on her head. In her hands she holds a skull, trident, Damaru and the noose (nagapasa). She is seated on a lion and by her power destroys all enemies.

52.5. In Tantric worship, Pratyangira is shown with a dark complexion, ferocious in aspect, having a lion’s face with reddened eyes and riding a lion wearing black garments, she wears a garland of human skulls; her hair strands on end, and she holds a trident, a serpent in the form of a noose, a hand-drum and a skull in her four hands. She is also associated with Bhairava, as Atharvana-Bhadra-Kali.

Sri Pratyangira Devi is also associated with Sri Chakra. She protects the devotees and guides him/her along the right path.

52.6. The Shaiva School suggests that Pratyangira sprung from the wings of Lord Sharabesha, the bird-lion-human form that Shiva assumed to pacify (subdue) the ferocious Narasimha.

[According to Kalikagama, the body of Sharabha should be that of a bird of golden hue, having two red eyes; and it should have two up-lifted wings and eight limbs. Sharabha, which is said to be mightier than an elephant, should have the fierce face of a lion grinning widely, having tusks and wearing kirita makuta. The torso of Sharabha resembles that of human male having four hands .The lower part of its body should resemble that of a lion having four legs, sharp claws and a tail. Sharabha should be shown carrying the figure of Narasimha in his human form with upraised folded hands, anjali mudra. ]

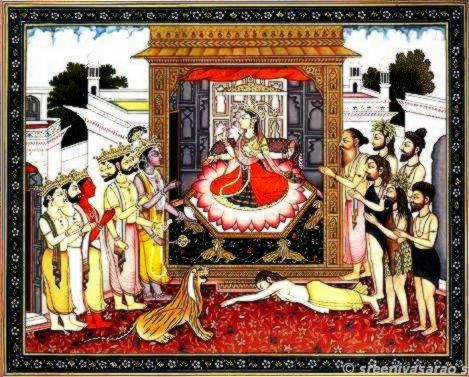

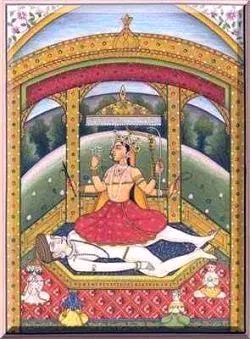

Mahalakshmi

53.1. Mahalakshmi is counted as the eighth Matrika in the Asta-matrika tradition followed in the Nepal region. Mahalakshmi, as Matrka, is not derived from Devi Mahatmya, although she is described as “Universal Mother’ in other contexts. As Matrka, Mahalakshmi is regarded as an aspect of Durga; not as Lakshmi the consort of Vishnu. Mahalakshmi here represents her subtle aspect as Mind, specially her Sovereignty.

53.2. In the Shaktha tradition, Mahalakshmi is an independent Supreme Divinity manifesting herself as Maha-Sarasvathi (Sattva), Mahalakshmi (Rajas) and as Maha-Kali (Tamas).

Devi Mahatmya explains Mahalakshmi as Devi in her universal form as Shakthi. She is the primordial energy and was the first to appear before everything (sarva-sadhya); she is both devoid of form (nirakara) and filled with forms (sakara); she is both manifest and un-manifest; She is the essence of all things (sarva sattva mayi). She creates and governs all existence (Isvari), and is known by various names (nana-abhidana-brut). She is the ultimate goal of yoga. Mahalakshmi is the creator of the Trinity: Brahma, Vishnu and Rudra.

53.3. Mahalakshmi is the presiding Goddess of the Middle episode (Chapters 2-4) of Devi Mahatmya. In her manifestation as Mahalakshmi, the Devi destroys the demon Mahishasura. The Goddess fought the demon for nine days starting from prathipath (the first day of the brighter half) of the month of Ashvayuja; and killed the demon on the tenth day Vijaya-Dashami ending his reign of evil and terror. Her victory symbolizes the victory of good over evil.

53.4. Mahalakshmi described as having been created by the effulgence of all the gods is depicted as Ashtadasha Bhuja Mahalakshmi, with eighteen arms.

Skanda Purana (Sahyadri khanda) describes Mahalakshmi as: “She who springs from the body of all gods has a thousand or indeed countless arms, although her image is shown with eighteen hands. Her face is white made from the light streaming from the face of Shiva. Her arms are made of substance of Vishnu are deep blue; her round breasts made of Soma are white. Her waist is Indra and is red. Her feet sprung from Brahma are also red; while her calves’ and thigh sprung from Varuna are blue. She wears a gaily coloured lower garment, brilliant garlands and a veil. In her eighteen arms, starting from the lower left, she holds in her hands : a rosary, a lotus, an arrow, a sword, a hatchet, a club, a discus, an ax, a trident, a conch, a bell, , a noose, a sphere, a stick, a hide, a bow, a chalice and a water pot.”

The Chandi Kalpa adds that Mahalakshmi should be seated upon a lotus (saroja sthitha) and her complexion must be that of coral (pravala prabha).

54.4. When she is shown with four hands, Mahalakshmi is depicted as seated on a lotus throne, holding padma, shankha, a kalasha and a fruit (bilva or maatulunga). Her four hands signify her power to grant the four types (chatur vidha) of human attainments (purushartha): dharma, artha, Kama and moksha.

54.5. The Shilpa text Rupa-mandana suggests Mahalakshmi with four arms (chatur-bhuja) should be depicted in the colour of molten-gold (taptha-kanchana-sannibha) and decorated with golden ornaments (kanchana bhushana). She is also described as having complexion of coral; and seated on a lotus. Her four hands carry matulunga fruit, mace, shield and bowl of liquor. Her head must be adorned with snake-hood and a linga.

[Note: 1.

The head-gears mentioned for the Matrkas are commonly the Kirita -makuta, Karanda-makuta and Jata-makuta. Mansara, the ancient text of Shilpa shastra, classifies these types of head-gears under the term makuta or mouli (Mansara: Mauli-lakshanam: 49; 1-232). For all makuta-s, the width commencing from the bottom should be gradually made lesser and lesser towards the top.

Among these, the Kirita-makuta is an elaborate crown that adorns major gods such as Vishnu and his forms (Narayana) and also emperors (Sarvabhouma).It has the appearance of Taranga-s (waves) and its middle is made into the shape of flowers and adorned with precious stones. The base of the Kirita-makuta should be curved like a crescent (ardha-chandra) just above the forehead. The height of the Kirita-makuta should be two or three times the length of the wearer’s face.

The Karanda-makuta is prescribed for lesser gods and for goddesses when depicted along with their spouse. It is simpler and shallower as compared to Kirita-makuta. The Karanda-makuta is a small conical cornet receding in tier. It is shaped like an inverted flowerpot, tapering from the bottom upwards and ending in a bud. The width of a Karanda-makuta at the top should, however, be only one-half or one-third less than that at its base.

The jata- makuta is suitable according to Mansara for Brahma and Rudra, as also for consorts of Shiva. Jata-makuta, is made up of jata or matted locks, which are twisted into encircling braids of spiral curls and tied into a knot looped at the top. It is held in place by a patta (band); and is adorned with forest flowers and by a number of ornamental discs like the makara-kuta, patra-kuta, and the ratna-kuta. In the case of Shiva, the jata-makuta is adorned with a crescent of the moon, a cobra and the Ganga.

In the case of Matrkas: Vaishnavi and Aindri are adorned with kirita-makuta; Brahmi, Varahi and Kaumari with karanda-makuta; while Maheshwari and Chamunda are adorned with jata-makuta.

Note: 2.

Among the Ayudhas carried by the Matrka deities the following are commonly mentioned:

-

- Khadga (Sword) ;

- Trishula (Trident) ;

- Chakra (Thunder – disc)

- Gada or Khitaka (Mace) ;

- Dhanush (Bow) ;

- Bana (Arrow);

- Bharji (Javelin) ;

- Parashu (Battle- Axe) ;

- Musula (pestle) ;

- Danda (staff);

- khatvanga (skull-mace),

- khetaka or Sipar (shield);

- Ankusha (Goad) ;

- Sutra or Pasha(Noose or lasso);

- Damaru (drum);

- Panapatra (drinking cup);

- Ghanta (Bell) ;

- Akshamala (rosary) ;

- Pustaka (book) ;

- kamandalu (water pot) ; and

- Vanamala (garland of forest-flowers

References and Sources

The iconography of the saptamatrikas: by Katherine Anne Harper: Edwin Mellen press ltd (1989-10)

Saptamatrka Worship and Sculptures by Shivaji K Panikkar; DK Print World (1997).

The Roots of Tantra by Katherine Anne Harper (2002)

Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions by David Kinsley; (1987)

Tribal Roots of Hinduism by SK Tiwari; Sarup and Sons (2002)

The Portrait of the Goddess in the Devī-māhātmya by David Kinsley

The Little Goddesses (Matrikas) by Aryan, K.C; Rekha Prakashan (1980)

Goddesses in Ancient India by P K Agrawala; Abhinav Publications (1984)

The Tantra of Sri Chakra by Prof. SK Ramachandra Rao ; Sharada Prakashana (1983)

Matrikas

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matrikas

Sapta Matrikas and Matrikas

http://shaktisadhana.50megs.com/Newhomepage/Frames/forumframebodyindex.html

The mother goddess in Indian sculpture By Cyril Veliath

http://www.info.sophia.ac.jp/fs/staff/kiyo/kiyo37/veliath.pdf

Some discussions on the Skanda – Tantra and Balagrahas

http://manasataramgini.wordpress.com/2008/09/03/some-discursion-on-skanda-tantra-s-and-balagraha-s/

The Mahabharata of Krishna –Dwaipayana Vyasa (Book 3, Part 2) Section 229

http://www.bookrags.com/ebooks/12333/180.html

Devis of the first enclosure

http://shaktisadhana.50megs.com/Newhomepage/Frames/gallery/Khadgamala/1stenclosureB.html

All pictures are from Internet

]

]