[ This is the second in the series of articles I would be posting on the art of painting in ancient India with particular reference to the Chitrasutra of Vhishnudharmottara purana. This article covers certain general aspects discussed in Chitrasutra text. ]

1. The Text

1.1. The Vishnudharmottara Purana or the Vishnudharmottara (as it is usually referred to) is a supplement or an appendix to the Vishnu-purana. It is generally believed to be a later insertion into Vishnu Purana. Some say , it is affiliated to the Pancharatra Agama, associated with the Vyuha doctrine.

The part three of the Vishnudharmottara gives an account, among other things, of the then – known branches, theories, methods, practices and ideals of Indian painting.

The text deals not only with its religious aspects but also, and to a far greater extent, with its secular applications. It initiates the aspirant into a world of joy and delights that only the colors, forms and representation of things — seen and unseen — can bring forth.

1.2. The Vishnudharmottara asserts that it is but a compilation ; and , is an attempt to preserve the knowledge that was hidden in older sources. Sadly, all those older texts are lost to us. Vishnudharmottara is thus the earliest exhaustive treatise available to us on the theory and practice of temple construction, painting and image making in ancient India.

[Perhaps no other Indian text on art (except the Nätyashästra) received as much scholarly attention from art historians as did the Chitrasütra of the Vishñudharmottara Puräna. The text of Chitrasütra was first published in 1912. And, its earliest translation into English was rendered by Stella Kramrisch (1924). She also provided explanations of its art; the interpretations of the key concepts as given in the third khanda of the Chitrasütra. Kramrisch had, in the process, also discussed, in fair detail, the artistic criteria, as also their pictorial modes and conventions.

Ananda. K. Coomaraswamy, in 1932, took a broader perspective; and, provided the explanations on the creative processes involved in ancient Indian art, in general. He described the visualization of form of the subject, by the artist, through meditative internalization, as a sort of Yoga. It was in this light that he explained connotations of the specific idioms employed in the theories of Indian art. And, he then interpreted their depictions , in the light of the aesthetic and iconometric injunctions detailed under the six limbs (shad-anga) of traditional Indian painting , as given in the Chitrasütra

-

- sädrusya (similarity);

- pramäna (proportion);

- rüpabhedä (differentiations or typologies of form);

- varnika-bhanga (colour differentiation);

- bhäva (emotional disposition); and,

- lävanya yojanam (gracefulness in composition) .

The efforts of these two pioneers were carried forward by scholars, such as: Priyabala Shah (1958); C. Sivaramamurti (1978); Parul Dave Mukherji (1998); Isabella Nardi (2003); and others, who provided deeper insights, additional explanations and interpretations.

We owe all these scholars a debt of deep gratitude. ]

1.3. Chitrasutra is that part of the Vishnudharmottara which deals with the art of painting (citraśikhaṇḍa – Khanda III, Adhyayas 35-43). This section , which concentrates on the theory and practice of painting , is named after its first line of Adhyaya 35.1a :

– atah param pravakshyami Chitra-sutram tavanagha.

Its compiler described it as “the legacy of the collective wisdom of the finest minds”.

[As regards the structure of the text :

:- Adhyaya 35 considers the mythic origin of painting and the five types of males together with their differing proportions.

:- Adhyaya 36 discusses measurements and proportions of the different parts of the body and the colours and other distinguishing features of the five male types.

:- Adhyaya 37 deals with the measurements of the five types of females, hair and eye types, and the general characteristics of a Cakravartin, the supreme ruler.

:- Adhyaya 38 gives details on auspicious marks that divine images, both sculpture and painting, should possess.

: – Adhyaya 39 treats the different postures (sthanas) for figures.

:- Adhyaya 40 describes how to mix paints, prepare the surface, and apply the paints.

:- Adhyaya 41, of cardinal importance, defines the four types of paintings.

:- Adhyaya 42, equally significant, prescribes the manner in which a large number of beings–royalty, priests, nature and heavenly sprites, demons, wives, courtesans, attendants of vaisnava deities, warriors, merchants, and others should be depicted.

:- And, Adhyaya 43 talks about the nine Rasas in painting, strengths and defects in painting, as well as sculpture in different materials.

In the closing, III.43.37, as if to underscore the unity and interdependence of the arts, states that whatever has been left unsaid about painting can be understood from the section on dance, and what is not given there can be supplied from painting.

-Yad-artha noktham tanruta vigneyam Vasudadhipa / Nruttepi noktham tat Chitram na atra yojyam Naradhipa / ]

Explaining why he took up the compilation; Sage Markandeya said , he was prompted by his concern for the future generations; for their enlightenment, delight and quality of life .

He said it was his firm belief that paintings are the greatest treasures of mankind as they have the aura and power to beneficially influence the minds and lives of the viewers.

1.4. In that context Chitrasutra makes some amazing statements:

*. Great paintings are a balm on the troubled brow of mankind.

*.Of all arts, the best is chitra. It is conducive to attainments in life such as dharma-artha -kama ; and has the virtue to liberate (emancipate) an individual from his limited confines

Kalanam-Pratamam-Chitrm;Dharma-Artha-Kama-Mokshadam/Manglya-Pradam-chaita-tad-gruhe-yatra Pratishtitm

*. Wherever it is established- in home or elsewhere- a painting is harbinger of auspiciousness.

*. Art is the greatest treasure of mankind, far more valuable than gold or jewels.

*. The purpose of art is to show one the grace that underlies all of creation, to help one on the path towards reintegration with that which pervades the universe.

*. A painting cleanses and curbs anxiety, augments future good, causes unequaled and pure delight; banishes the evils of bad dreams and pleases the household -deity. The place decorated by a picture never looks dull or empty.

1.5. The Vishnudharmottara is dated around sixth century AD, following the age of the Guptas, often described as the Golden Age of Indian Arts. It is perhaps the world’s oldest known treatise on art. However, not much is known of its author, as is the case with most Indian texts .

Vishnudharmottara follows the traditional pattern of exploring the various dimensions of a subject through conversations (Samvada) that take place between a learned Master and an ardent seeker eager to learn and understand. Chitrasutra too employs the pretext of a conversation between the sage Markandeya and king Vajra who seeks knowledge about image making (shilpa).

2. Concepts

2.1. The Chapter 46 of the Third Book of the Vishnudharmottara commences with a request by king Vajra to sage Markandeya seeking knowledge about image-making.

King Vajra questions “How could one make a representation , in painting or image , of a Supreme being who is devoid of form , smell and emotion ; and destitute of sound and touch?”.

Rupa-Gandha-Rasa-hinaha, Shabda-Sparsha vivargitaha / Purushatu tvaya prokta tasya rupma idam katham / 3.46.1/

Sage Markandeya explains ”The entire universe should be understood as the modification (vikriti) of the formless (prakriti) . The worship and meditation of the supreme is possible for an ordinary being only when the formless is endowed with a form; and, when that form is full of significance. The best worship of the Supreme is, of course, contemplation of the formless with eyes closed and all senses subdued in meditation.”

Prakruti-Vikruti tasya rupena Paramathmanha / a-lakshyam tasya tad-rupam Prakruti sa prakeertita /3.46.2/

Sa-kara Vikruti-jneya tasya sarvam Jagatha-tasyaitam /Puja-Dhyana-adikam karthrum Sa-kara sevya shakyate /3.46.3/

2.2. With that, the life in its entirety becomes a source of inspiration for artistic expressions. In another passage, Chitrasutra cites the nature that envelops the artist as the source of his inspiration. The text, therefore, mentions that, as in dance so in painting, there has to be a close relation with the world around us; and, reflection of it in as charming a manner as possible

2.3. And, as regards the skill required to express those emotions in a visible form, the text suggests that painter should take the aid of Natya, because an understanding of Natya is essential for a good painter.

Yatha nritte , tatha chitre trailokya-anukritis smrita / drishtayas cha tatha bhava angopangani sarvasah / karas cha ye maya nritte purvokta nripasattama / ta eva chitre vijneya nrittam chitram param matam // 3.35.5-7 //

The sage then instructs that without the knowledge of music, one cannot understand Natya. And, without the knowledge of Natya , one can scarcely understand the technique of painting. — “He who does not know properly the rules of Chitra (painting)”, declares the sage , “can scarcely discern the essentials of the images (Shilpa)”.

The same teaching is put in another way too.

One who does not know the laws of painting (Chitra) can never understand the laws of image-making (Shilpa); and, it is difficult to understand the laws of painting (Chitra) without any knowledge of the technique of dancing (Nrtya); and, that, in turn, is difficult to understand without a thorough knowledge of the laws of instrumental music (vadya). But, the laws of instrumental music cannot be learnt without a deep knowledge of the art of vocal music (gana).

All these , mean to say that the arts of Music -> Dance -> painting -> sculpture are inter related; and, that Music is at the base of all such fine-arts.

**

Dr. Isabella Nardi , in her Doctoral Thesis ‘ The Theory of Indian Painting (2003) , in summary, opines :

It is difficult to strictly separate certain theories of painting from those of sculpture; as, these two artforms are sometimes treated side by side without distinction in the texts.

While term Citra is generally translated as “painting,” the texts posit Citra in a more abstract sense as a ‘mental image’ that can be differently interpreted and effectuated in practice in both painting and sculpture. The term Citra , therefore, is open to a variety of uses and interpretations; and, a more holistic approach needs to be adopted in understanding the theory of Indian painting.

The tendency to separate the theory of painting from the theory of sculpture is misleading. Indeed, the characteristically holistic outlook of Indian knowledge generally implies that the drawing of such strict boundaries between the sciences, whether art or non-art, is ‘unnatural’.

The text Chitra-sutra places painting and the science of painting in a wider perspective, together with the other arts. It explains how all the arts are correlated to each other; and, stresses the need to know all of them in order to perform painting or sculpting.

3. Chitra and Natya

3.1. That does not mean, the positions of the dancers have to be copied on murals or scrolls. What it meant was that the rhythm, fluidity and grace of the Natya have to be transported to painting . The Chitrasutra says “it (Natya) guides the hand of the artist, who knows how to paint figures, as if breathing, as if the wind as blowing, as if the fire as blazing, and, as if the streamers as fluttering. The moving force, the vital breath, the life-movement (chetana) are to be explicit in order to make the painting come alive with rhythm and force of expression . The imagination, observation and the expressive force of rhythm are the essential features of painting”.

[ The Visnudharmottara Purana deals with dance, in its third segment – chapters twenty to thirty-four. The following is an extract from The Evolution of Classical Indian Dance Literature: A Study of the Sanskritic Tradition (1989) by Dr. Mandakranta Bose, Somerville College.

In chapter twenty (the first chapter of the section) , the author follows the Natyasastra in describing the abstract dance form, nrtta; and, in defining its function as one of beautifying a dramatic presentation.

The chapter twenty deals with the appropriate places for the performance of each category, discussing aspects of the stage and the presentation of the preliminaries. The discussion includes the characteristics of actors, the four different types of abhinayas, namely – angika, vacika, sattvika and aharya, and the names of all the complicated movements necessary for the composition of a dance sequence. In addition, the author briefly touches upon the pindibandhas or group dances mentioned by Bharata and goes on to describe vrtti, pravrtti and siddh; that is – the style, the means of application and the nature of competence.

The twenty-first chapter discusses sthanas or postures while lying down, while the twenty-second deals with the sthanas assumed while sitting. The focus of these two chapters seems to be on dramatic presentation.

The twentythird chapter is devoted to postures meant for both men and women.

The twenty-fourth chapter lists the movements of the major limbs, the angas, along with the meaning attached to each of them. The major limbs, according to this text, are the head, the neck, the chest, the sides, the waist, the thighs, the shanks and the feet. In conclusion, the chapter defines the cari and the karana, the two vital and complicated movements required in dancing.

In the twenty-fifth chapter, the movements of the upangas or minor limbs are discussed, including the glances that express rasa and sthayi and vyabhicaribhavas, the movements of the pupils, eyebrows, nose, tongue and lips as well as the application of these movements.

The twenty-sixth chapter describes three types of hand-gestures, those made with one hand, those made with both-along with the meanings they can convey-and hand-gestures meant for dancing, which convey no meaning.

The twenty-seventh chapter is devoted to the explanation of different kinds of abhinaya and the costumes and decorations necessary for a performance.

The twenty-eighth chapter deals with samanyabhinaya, giving general directions for expressing different moods and responses to seeing, touching and smelling objects. Although the author designates this chapter as a discussion of samanyabhinaya, he includes citrabhinaya, that is, special presentations. In fact, this chapter is a conflation of the contents of chapters twenty-two and twenty-five of the Natyasastra and contains extensive quotations from it.

The twenty-ninth chapter describes the gatis, that is, gaits, the thirtieth discusses the nine rasas and the thirty-first the bhavas.

A new feature of the treatment of body movements that is added to the discussion of body movements appears in the thirty-second chapter, which deals with what is termed rahasyamudras, that is, hand-gestures meant for mystical and ritualistic purposes.

Continuing the discussion in the thirty-third chapter, the author lists more mudras, all meant for religious purposes, and calls them mudrahastas, and associates them with hymns to the gods and goddesses.

The thirty-fourth and final chapter on dancing is devoted to the legend of the origin of dancing. Since the work is devoted to the worship of Vishnu, it is not surprising that its author should view Vishnu as the originator of the art of dancing]

The Chitrasutra recognized the value and the significance of the spatial perspective.

*.“He who paints rolling waves, darting flames, smokey streaks; fluttering banners and Apsaras floating in the sky , indicating the direction and movement of the wind, should be considered a great painter”

Taranga- Agnisikha- Dhuman ; Vijayantya -Apsara -adhikam vayu-gatya likhed yas tu vijneyas sat u chitrakrit // 3.43.28

*.“He who knows how to show the difference between a sleeping , an unconscious and a dead man ; or who can portray the visual gradations of a highland and a low land is a great artist “

Suptam cha chetanayuktam , mritam , Chaitanya-varjitam / nimnonnata-avibhagam cha yah karoti sa chitravit // 3.43.29

3.2. The Shilpa (sculpture) and Chitra (painting) are closely related to Natya (dance) in other ways too. The rules of the iconography (prathima lakshana appear to have been derived from the Natya-shastra. The Indian sculptures are often the frozen versions or representations of the gestures and poses of dance (caaris and karanas) described in Natya-shastra. The Shilpa and chitra (just as the Natya) are based on a system of medians (sutras), measures (maanas), postures of symmetry (bhangas) and asymmetry (abhanga, dvibhanga and tribhanga); and on the sthanas (positions of standing, sitting, and reclining). The concept of perfect symmetry is present in Shilpa and chitra as in Nrittya; and that is indicated by the term Sama.

3.3. The Natya and Shilpa shastras developed a remarkable approach to the structure of the human body; and delineated the relation between its central point ( Nabhi, the navel), the verticals and horizontals. It then coordinated them, first with the positions and movements of the principal joints of neck, pelvis, knees and ankles; and, then with the emotive states, the expressions. Based on these principles, Natya-shastra enumerated many standing and sitting positions. These, demonstrated the principles of stasis, balance, repose and perfect symmetry; And, they are of fundamental importance in Indian arts, say, dance, drama, painting or sculpture.

3.4. Another aspect of the issue is that painting as a two-dimensional form, can communicate and articulate space, distance, time and the more complex ideas in way that is easier than in sculpture. That is because , the inconvenient realities of the three dimensional existence restrict the fluidity and eloquence of the sculpture.

The argument here is , making a sculpture is infinitely harder than making a painting.

According to that; it is almost not possible to depict, directly, in a sculptural panel the time of the day or night – darkness, evening, twilight or bright light etc.. That difficulty also applies to depiction of colours (colour, in fact, is not a medium directly compatible with sculpting). And, it is also not easy to bring out the differences between a dead body and a sleeping person, particularly if the two are placed side by side. The sculptor – artist (shilpi) will have to resort to some other clever suggestions to bring out the differences. That depends on the ingenuity of the artist.

4. Painting in ancient society

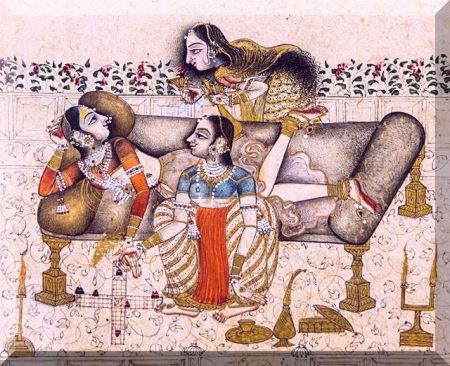

4.1. According to Chitrasutra, all works of art including paintings played an important role in the life of its society. The text mentions about the presence of paintings as permanent or temporary decorations on the walls of private houses, palaces and of public places. Apart from wall paintings, the floors of the rich homes and palaces were decorated with attractive patterns and designs inlaid with precious stones.

4.2. Paintings had relevance in the private lives too.The polite education of a Nagarika the educated urbane man of town included knowledge and skill of several arts in addition to erudition in literature, rhetoric, grammar, philosophy and allied subjects. Painting was rated high among these Vaiharika-silpas or vinoda-sthanas – seats of pleasure or hobbies or arts for one’s own pleasure, enjoyment and amusement (gītaṃ,vādyaṃ, nṛtyaṃ, ālekhyaṃ, viśeṣakacchedyaṃ, KS.1.3.15).

The gentleman of leisure and culture , painted for pleasure or in earnestness; but, of course, not for earning a living. Such persons, therefore, considered Alekhya, the art of painting as Vinodasthana – a pleasant diversion from other gnawing concerns and thoughts – Ardhalikitam idam Vinodasthanam asmabhihi .

[Sometimes, a gentleman of leisure who had learnt the art as a leisure pastime had to use it to earn a livelihood when bad days had fallen upon him . The Samvahaka in Mrichchakatika was one such hapless character who bemoans his lot forced to earn a living by practicing an art (kaleti sikshita jivikaya samvritta )… It was therefore said that , in any event, it is safer to learn some art , as it might come in handy in your lean days – who knows…!!! ]

Vatsayana as also Syamalika , describes the tasteful set up and arrangement in the room of a typical urban gentleman of pleasure who evinces interest in literature, dance, music and painting. The articles in his room would include a vina hanging from a peg on the wall (naaga-danta vasakta vina); a painting board (chitra palakam) ; a box-full of colors and brushes (vatika tulika samgraha) ; a cup for holding liquid colors (meant for painting) casually kept on the window sill (alekhya-varnaka-paatram) ; and, books of verses (kurantaka maala).

nāga-dantāvasaktā vīṇā. citra-phalakam. vartikāsamudgakaḥ. yaḥ kaś cit pustakaḥ. kuraṇṭaka-mālāś ca – Kamasutra 1.4.4

Tatoham aasannam alekhya -varnaka-paatram gavakshad aksipya.. Padataditaka of Shyamalika , a monologue play

The courtesans too were proficient in fine arts such as music, dance, painting poetry as also in body-care techniques. Damodaragupta mentions that a courtesan evinced keen interest in enhancing her array of skills; and, she devoted much time and effort to excel in painting and other fine-arts , to add to her other accomplishments

– alekhyadau vyasanam vaidagdhya-akhyataye na tu vinodaya (Kuttanimala)

Even a calculating courtesan would madly fall in love with a talented painter, though impoverished. Somadeva’s Katha-sarit-sagara narrates number of delightful stories of such young and impetuous courtesans, bordering on recklessness. .

Syamilaka , in his Bana play Padataditaka , provides the instance of Kusumavatika, a courtesan who passionately fell in love (mahan madanon-madah) with a Chitracharya (master painter) Sivasvamin. She was drawn to him mainly by his excellence in his art , though he was utterly poor.

Janita evasmatsvami yathasmatsakhya kusumavatikayah chitracharyam sivasvaminam prati mahan madanonmadah iti- Padataditaka

There were also Shilpini-s the court maidens in the service of the princesses. These talented Shilpini-s were well trained (prauda) painters who excelled in delicate drawing of portraits (viddha-chitra); and, they were often commissioned with the task of carrying the portraits they had drawn of their princess to distant courts to show them to the eligible princes for seeking alliance in marriage. And, sometimes such portraits – of princes and princesses – were sent round several Royal Courts in search of suitable alliances . The katha-sarit-sagara carries numerous such tales.

It is said; Nagarakas (city dwellers), connoisseurs of art, accomplished courtesans, painters, and sculptors among others studied standard texts on painting. Such widespread studies naturally brought forth principles of art criticisms as in alankara-sastra.

For the gentlemen of leisure , fine arts like music , dance painting and sculpture were the source of ones’s own pleasure and amusement (vaiharika-silpa or vinodasthana). But , there were several professionals who practiced these arts and art-forms as a craft, the main stay of their life.

Kautilya deems it a responsibility of the state to support all such art-masters that spread knowledge among youngsters.

The play Malavikagnimitra mentions that Chitracharyas who combined the theory of the art with proficiency in dance performance were respected and treated on par with Natyacharyas in the kings court.

The art of painting – chitra kala– was recognized as an essential part of the curriculum in the upbringing of children of “good families”.

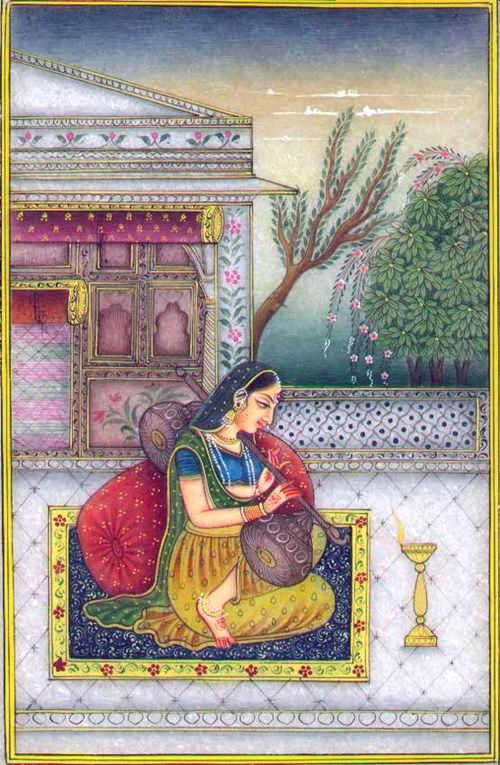

Education in fine arts like music, dance and painting was considered essential for unmarried maidens of affluent families. The ancient stories are replete with instances of young lovers exchanging paintings as loving gifts.

While on the subject , I may mention that Chitrasutra regards the Alekhyas or paintings as mangalya-lekhyas – auspicious in homes; and , it observes:

the pictures which decorate the homes (including the residential quarters of the king- rajnaam vasagriheshu) should display sringara, hasya and shantha rasa. Only such paintings that depict moods of laughter, fun, playfulness, love and peace should be seen at homes. They should exude joy, peace and happiness; and, should brighten up the homes and lives of its residents.

The pictures that depict horror; and , the ones that evoke fear, rage, disgust , sorrow and cruelty ; as also those that show battle scenes, death, cremation / burial grounds, heart rendering episodes, wretchedness, glorifying evil and base motives, inauspicious themes etc., should be forbidden and should never be displayed at homes where children dwell.

Further, the text mentions that the pictures which show a bull with its horns immersed in the sea; men with ugly features or those fighting or inflicted with sorrow due to death or injury; as also the pictures of war, burning grounds as being inauspicious and not suitable for display at homes.

But, the text says, the pictures of all types of depictions and Rasas could be displayed at court-halls, public halls, galleries and temples.

[Sringara, hasya, shantakhya lekhaniya griheshu te // parasesha na kartavya kadachid api kasyachit / devavesmani kartavya rasas sarve nripalaye / rajavesmani no karya rajnaam vasagriheshu te , sabhave’smasu kartavya rajnam sarvarasa grihe, varjayitva sabham rajno devavesma tathiva cha / yuddha-smashana-karuna-mrita-dukkha-aarthakutsitan / amangalyamscha na likhet kadachid api vesmasu // ]

**

4.4. Icons were generally classified into four categories:

(1) as those painted on the wall, canvass, paper, wall or pot (chitraja) ;

(2) as those molded in clay or any other material like sandal paste or rice flour (lepeja, mrinmayi, or paishti);

(3) as those cast in metal (pakaja, lohaja, dhatuja); and,

(4) as those carved in stone, wood or precious stones (sastrotkirana, sailaja, daaravi or rathnaja).

Early icons were made in clay or carved wood; and such images were painted over.

[ As regards the images made of clay, sand or lacquer etc., the Sukraniti-sara says : Images that are drawn or painted, or made of sand, clay or paste or those made for learning – it is no offence if such images fail to conform to the prescribed rules. For , these are intended only for temporary use; and, are usually thrown away, afterwards, as these are generally made for mere amusement. They need not always strictly adhere to the conventions prescribed by the Shastras.

Lekhya lepya saikati cha mrinmayi paishtiki tatha, Eteshani laksliana-bhave na kaischit dosha iritah ]

Hallow figures (sushira) of gods, demons, Yakshas, horses, elephants, etc., were placed on the verandas of houses , on the stages and in public squares etc., as pieces of decoration . Such hallow images were usually made of clay, cloth, wood or leather .

Paintings were classified as those drawn on the ground – like Rangoli, floor decorations etc (bhumika); those on the wall-like murals and frescoes (bhitthi); and, portrait (bhava chitra).The first two were fixed (achala); and, the third was portable

4.5. The Patas (poster or banner like paintings) were commonly displayed in public squares. It is mentioned, such paintings were employed as a means and as a method of communicating with the town’s people. The messages displayed picturesquely on the Patas could be understood by all – lettered and unlettered alike.

The art, thus, entertained , educated and enlivened common people.

5. Art Appreciation

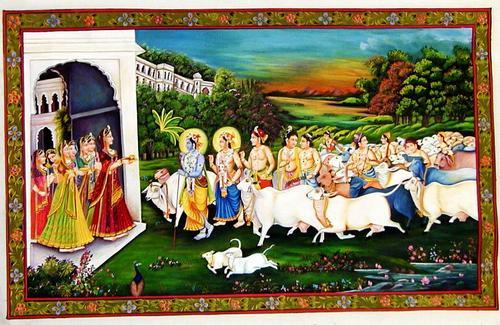

5.1. As regards the deities depicted in art, it is explained; in the Indian tradition a deity is a Bimba the reflection or Prathima , the image of god; but , not the god itself. Bimba is reflection, like the reflection of the distant moon in a tranquil pool. That reflection is not the moon ; but, it is a suggestion (prathima) of the moon. In other words, a deity is a personification of a sublime idea, a conception or his/her mental image of god, translated to a form in lines, color, stone, metal , wood or whatever .

The Chitrasutra says, those qualities that we admire in a divine being are within us. And, when we respond to those images brought to us in art, we awaken those finer aspects that are latent in us. When we are filled by that grace, there is no space left for base desires and pain; we have become that deity.

5.2. When we view sunrise or a great work of art, Chitrasutra says, we experience the joy brought to us by its sublime beauty (ananda , ahlada), as we let dissolve our identities and attachments; and, become one with the object of beauty. It is a moment that bestows on us the grace that underlies the whole creation. Art, it said, is a liberating experience.

[ Dr. Harsha V. Dehejia in his The Advaita of Art writes :

The concept of Artha also appears in the theories of Art-appreciation. There, the understanding of art is said to be through two distinctive processes – Sakshartha, the direct visual appreciation of the art-work; and, Paroksharta, delving into its inner or hidden meaning. The one concerns the appreciation of the appealing form (rupa) of the art object (vastu); and, the other, the enjoyment of the emotion or the essence (rasa) of its aesthetic principle (guna vishesha). Artha, in the context of art, is, thus, essentially the objective and property of art-work; as also the proper, deep subjective aesthetic art-experience.

In the traditions of Indian art, the artist uses artistic forms and techniques to embody an idea, a vision; and, it is the cultured, understanding viewer (sah-hrudaya), aesthete (rasika) that partakes that vision.

It is said; an art-object for a connoisseur is not only a source of beauty; but is also an invitation to explore and enjoy the reason (Artha) of that beauty. Thus, Artha is the dynamic process of art-experience that bridges the art-object and the connoisseur.

A work of art is not a mere inert object; but, it is so rich in meaning (Artha) that it is capable of evoking manifold emotions and transforming the aesthete.]

6. Elements of painting

6.1. While discussing the elements of a painting, the Chitrasutra says :

- The masters praise the rekha‘s –lines (delineation and articulation of form);

- the connoisseurs praise the display of light and shade;

- women like the display of ornaments; and

- the richness of colors appeals to common folks.

The artists, therefore, should take great care to ensure that the painting is appreciated by everyone”.

Rekha cha Vartana chaiva Bhushanam Varna meva cha / vijnaya manu-sresta Chitra-karma tu Bhushanam /3.41.10 /

Rekham prashamsam tya Acharyaha ,vartanam cha vichakshanaha / Stri yo Bhushanam icchanti , varnadai itare janaha / 3.41.11 /

Ithi mathva tatha yatnaha karthaya chitra-karmani / sarvasya chitta-grahanam yatha sthanai manujottama / 3.41.12 /

Talking about lines, Chitrasutra favors graceful, steady, smooth and free flowing lines; but not the crooked and uneven lines. It was said; while the free flowing, continuous, smooth and graceful line are soothing to the eyes (Rekha-nivesotra yad ekadharah), the broken lines offend the eyes. A good painting must be graceful, free of crooked lines.

idam cha paurandram avaimi karma Rekha-nivesstra yad eka-dharah // karma parinata-rekha mamsalair anga-bhangair laghur api likhiteyam drisyate purna-murtih

The text appears to hold the view; while delineation, shading, ornamentation and coloring are the decorative aspects (visual) of a painting, the rekha, the lines that articulate the forms are its real substance.

Its Masters valued the effects best captured by least number of lines. Simplicity of expression symbolized the maturity of the artist. The artist and the art critics appreciated the best effect in a picture captured by a minimum number of lines composing the figure. In the Viddhasalabhanjika , there occurs a remark of the vidushaka (court jester) that the painting looks complete with even a minimum of drawing : api laghu likhiteyam drisyate purnamurtih

Incidentally, the main characteristics of the Ajanta paintings are the use of free flowing lines for delineating beautiful figures and their delicate inner feelings; together with use of shading different parts of the body to produce three dimensional effects in the images. The other was the use of proper colors at times contrasting and at times matching to create magical effects. These were precisely the principles that Chitrasutra emphasized.

6.2. The text says in another context, when a learned and skilled artist paints with golden color, with articulate and yet very soft lines with distinct and well arranged garments; and graced with beauty, proportion , rhythm and inspiration, then the painting would truly be beautiful.

Sva anuliptva akasha nideshanam madhuka Shubha / su-prasanna abhi gupta cha bhumihi sat-Chitra-karmani /3.41.14 /

Su-snigdha vispusta Suvarna-rekham vidvan anyata desha vishesha vesham / Pramana Shobha-birahiyamanam krutam bhaveth Chitram ativa chitram/3.41.15 /

6.3. The elements that contribute to help a picture to attract a spectator are merits like delicacy of line , sweetness of execution , symmetry , likeness to the original , foreshortening , suitable background , spirited and life-like deportment of the figure and so forth .

And, as regards the defects that repel the viewer , they are generally :

-

- coarseness of line work ,

- weak and vague drawing ,

- lack of symmetry ,

- color-muddling ,

- inappropriate pose,

- lack of emotion,

- vacant look in the figure ,

- smudgy execution,

- life-less portrayal

- , disproportionate limbs ,

- disheveled hair

- and so on

Durbalyam, sthula rekhatvam , avibhaktatvam eva cha / varnanam sankaras, chatra chitradoshah , prakirtitah / sthanam pramanam bhulambho madhuratvam vibhaktata / sadrisyam kshayavriddhi cha gunastakam idam smritam / sthanahinam gatarasam sunya drishtimalimasam / chetanarahityam yat syat tad astakam prakirtitam // lasativa cha bhulambo slishyativa tata nripa / hasativa cha madhuryam sajiva iva drisyate//sasvasa iva yachchitram tachchitram subhalakshanam/ hinangamalinam sunyam baddha-vyadhibhayakulaih // vrittam prakirnakesaischa sumangalyair vivarjitam / pratitam cha likhed dhiman napratitam kathanchana // 3.43.17-23

6.4. The renowned scholar Sri C. Sivaramamurti , quoting another Shilpa text Upamiti-bhava prapancha-katha mentions :

For a critical appraisal of a picture of excellent drawing composed of fine lines, the brush strokes of which are almost imperceptible under a delicate coat of bright color :

it is essential to project an excellent treatment of an illusion of relief on a flat surface ,

-

- technically styled chiaroscuro ,

- appropriate ornamentation ,

- systematical representation of limbs composing an ideal body ,

- a proper shading of the figures by a mode of stippling, and

- a proper representation of emotion by an expression of it in the eyes , since it is the heart of the painting

these are all essential factors that go to make a good picture.

Tatas samarpito bandhulayasam dviputasamvartitas chitrapatah , pravighatya cha nirupito harikumarena / yavad drishtam alikhitam ekapute suvibhakto ujjvalena varnakramena nimnonnata avibhagena samuchhitena bhushanakalaapena suvibhaktha avayava archanayati vilakshanaya bindu vartinya abhinava Sneha rasotsukatyaya parasparam harshotphulla-abaddha-dristikam-samruddha-prema-ati-bhanduraikataya-alanghita-chittanivesam vidyadharam – mithunakam iti // Upamiti-bhava prapancha-katha

These qualities, while composing a picture, essentially, stress the importance of the virtues of

-

- purity of line-work;

- arrangement of ornamentation;

- appropriate manipulation of color; and,

- clarity in the expression of emotions.

It is said; the emotion is the most significant aspect of a painting, the true depiction of which sets apart a Master from the rest

Abhihitam anena aho ranjitoham anena chitrarara-kaushalena , tatha – atra suvishuddha rekha . saghatadi bhushanani , uchitkrama varnavichchhittih pari-sphuto bhava-atishayah – iti / dushkaram cha chitre bhava-aradhanam / tad eva chabhimatam ati-vidagdhanam / tasya chaatra prakashah paripusto drishyate // Upamiti-bhava prapancha-katha

The master-stroke of the painter, which makes great art distinctive; and which, independent of color and line, adds vitality to the picture is praised by scholars and connoisseurs

6.5. It is said; a great painter tries to represent the ideal. As for the faults that meet his eyes, he ignores them and presents only the good things in life. Thus, it is in his power to better the world we live in , at least in his picture.

Whatever that is not beautiful can be made to look different in painting ( yad yat sadhu na chitre tat tad anyata syat kriyate )

The Guna (merits) and the Dosha (blemishes), the proper portrayal of Rasas, emotions, suggestive imports, styles of execution are all elaborated in the Chitrasutra, the standard text on the principles of painting in ancient India.

Srungara Hasya Karuna Veera Raudra Bhayanakam / Bhibathsa Adbhuta Shantha cha Nava Chitra-rasaha smruthaha /3.43.1/

Tatra yat Kanthi Lavanya Lekha Madhurya Sundaram / Vidagda Vesha-bharanam Srungare tu Rase -bhaveth /3.43.2

The text at various places airs its clear opinions on what it considers auspicious (good) and “bad “pictures. To put some of these in a summary form :

*.Sweetness, variety, spaciousness of the background (bhulamba) that is proportionate to the position (sthana) of the figure, resemblance to what is seen in nature and minute and delicate execution are the good aspects of a chitra.

*.A painting drawn with care pleasing to the eye, thought out with great intelligence and ingenuity and remarkable by its execution, beauty and charm and refined taste and such other qualities yield great joy and delight.

*.Chitrasutra mentions: proper position, proportion and spacing; gracefulness and articulation; resemblances; increasing or decreasing (foreshortening) as the eight good qualities of a painting.

*.A picture in which all aspects are drawn in acceptable forms in their proper positions, in proper time is excellent.

*.A painting without proper position, devoid of appropriate rasa, blank look, hazy with darkness and devoid of life movements or energy (chetana) is inauspicious.

*.Weakness or thickness of delineation, want of articulation, improper juxtaposition of colors are said to be defects of painting.

*. In a picture one should carefully avoid placing one figure in front of another.

*.A painter who does not know how to show the difference between a sleeping and a dead man or who cannot portray the visual gradations of a highland and a low land is no artist at all.

*. A picture shaded only in some parts and other parts remaining un-shaded is bad (adhama)

*. Representation of human figures with too thick lips, too big eyes and testicles and unrestrained movement are defects.

[There was even a down-to-earth or rather a harsh discussion on what is ‘good’ and what is ‘beauty’ in a painting.

Nilakanta Dikshita (Ca. 16th-17th century), minister, poet and theologian of Nayaka-period, known for his incisive satirical wit and quick repartee , in his Vairagya-shataka, poses a mute question: ‘What is beauty?’.

And, he replies; there cannot be a single definitive answer to that question; as it differs from person to person. And, at times, what one appreciates and adores as ‘beautiful’, the others might find it utterly ridiculous.

At the end, the question remains unresolved.:

‘A dog delights in the curl of the bitch’s tail; the pig finds joy in the rotund belly of the sow; the monkey jumps with glee and great excitement at the sight of his mate’s toothy chuckle; a donkey can hardly restrain itself when drawn by the loud bray of his sweetheart; and, a human male goes agog bursting into song and dance at sight of lumps of flesh on a woman’s chest.

What is called ‘beauty’ is not in the thing; but, is in the feeling that it evokes. Each one rushes after his own sense of beauty – Loko bhinna ruchihi.

[Svanah pucchanchala-kutilatam; sukurah kukshiposham ; kisa danta-prakatana-vidhim; gardhabha ruksha gosham. . ! ; martyah vakshassvaya -thum api cha strishu dristva ramante tat saundaryam kim iti phalitam tattadajnanato anyat ..]

There are varied sorts of people who inhabit the earth. Among them are countless who are devoid of education, not to talk of aesthetic sensibilities, who are incapable of appreciating art. Only a few, cultured connoisseurs (sah-hrudaya, rasika) freed from prejudices are blessed with the gift of true art appreciation.

The artists , in general, intensely desire their work to be appreciated. In their such anxiety, some eagerly offer their creation or handiwork (hastochchyam) to the view of royal connoisseurs and wealthy patrons with deep humility. But, sadly , mere wealth does not guarantee true appreciation of art.

And, at the same time, the painter too has his own favorite among his creations. Thus, there is a wide range even among art-lovers.

*

Further, the concept of what is beautiful, what is appealing and what is appropriate , also depends on each viewer’s taste; rooted in her/his cultural and intellectual background.

Rudrabhatta, in his Srngaratilaka (3), describes a scene where a group of forest-dwelling hunters, along with their women folk , stray into an abandoned palace, whose king had fled following his defeat. As the hunter-folk wander through the deserted rooms in the building, they come upon murals painted on its walls.

As they gaze at the paintings, they are surprised, amused ; and, break into uncontrollable laughter. Each points out to the other in the group, the details in the painting; and, criticize the dim-witted painters. The women poke fun, ridicule and laugh heartily at the paintings, till their eyes are wet with tears .

“ I wonder , how could this dumb wit show pearl-strands as jewels on the breasts of these good-looking women, instead of adorning them with Gunja beads; and, why did he put such heavy lotus flowers on their delicate ears, instead of light and colorful peacock feathers. Strange are the ways of men ….!!!”

tyaktvā guñjaphalāni mauktikamayī bhūṣā staneṣv āhitā strīṇāṃ kaṣṭam idaṃ kṛtaṃ sarasijaṃ karṇe na barhicchadam / itthaṃ nātha tavāridhāmni śavarair ālokya citrasthitiṃ bāspārdrīkṛtalocanaiḥ sphuṭaravaṃ dāraiḥ samaṃ hasyate // ST_3.3b // ]

6.6. Chitrasutra cautions against inconvenient painting stance or a bad seat; sloppiness and bad temper ; thirst and absentmindedness – as such distractions might affect the quality of the painting.

Durasanam , duranitam , pipasa cha anyachittata / ete chitra-vinasanasya hetavah parikritah / – 3.48.13

6.7. Vishnudharmottara regards art creation (Chitra-yoga) almost as worship of the divine. It asks the artist to approach his task with reverence. While preparing to paint the deities, it advises the artist to be restrained; wear proper apparel; offer salutations to his Guru, to his elders; to contemplate on their Dhyana-slokas; sit, facing East, in a serene attitude of peace and joy in his heart; and, commence his task with diligence and great devotion.

Chitra-yoga viseshena svetavasa yatatmavan / brahmanam pujayitva tu svati vachya pranamya cha / pramukho devata-adhyayi chitra-karma samacharet – 3.40;11.13

6.8. Chitrasutra also mentions six limbs (Anga) of painting as:

- rupa-bheda (variety of form);

- pramana (proportion);

- Bhava (infusion of emotions);

- lavanya-yojanam (creation of luster and having rainbow colors that appear to move and change as the angle at which they are seen change);

- Sadrushya (portrayal of likeness); and

- varnika-bhanga (color mixing and brushwork to produce the desired effect)

Roopabhedah pramanani bhava-lavanya-yojanam | Sadrishyam varnakabhangam iti chitram shadakam ||

(i). Rupa-bheda consists in the knowledge of special characteristics of things – natural or man-made. Say, the differences in appearances among many types of men , women or natural objects or other subject matter of the painting.

(ii). Pramana: correct spatial perception of the objects painted and maintaining a sense of harmony, balance and a sense of proportion within the figure and also in its relation to other figures; and to the painting as a whole. The sense of proportion also extended to the way major figures are depicted by placing at the center and surrounding them with lesser figures in smaller size symbolizing their status Vis a Vis the main figure. The Indian artists were guided more by the proportions than by absolute measurements. The proportions were often symbolic and suggestive.

(iii). Bhava: consists in drawing out the inner world of the subject; to help it express its inner feelings. It takes a combination of many factors to articulate the Bhava of a painting; say , through eyes, facial expression, stance , gestures by hands and limbs, surrounding nature, animals , birds and other human figures. Even the rocks, water places and plants (dead or dying or blooming or laden) are employed to bring out the Bhava. In narrative paintings, the depiction of dramatic effects and reactions of the characters from frame to frame demands special skill.

Since colour is a major medium in painting, the emotions and moods are expressed through manipulating colours, their density, tones, lines, light, shades etc. The ingenuity, imagination and skill of the artist discover their limitations here..

(iv). Lavanya –yojanam: Creation of grace, beauty, charm, tenderness and illuminating the painting and the hearts of the viewer. It aims to uplift and brighten the mood of the figures, the viewers and the surroundings.

(v). Sadrushya: Achieving credible resemblance to objects of the world around and to the persons. The resemblances are not mere general but extend to details too. And ,

(vi). Varnika-bhanga : Artistic manner of improvising color combinations, tones and shades. It also involves delicate and skillful use of brushes and other aids. It represents the maturity of the artist’s techniques and fruitfulness of his experience.

Auchitya, the most appropriate expression of a theme, as either in poetry or in art, is a very relevant aspect of any creative activity. The painters took special care to adhere to the basic principles of that factor. It was said; a thing in its right place is beautiful; and, in a wrong place, it is just ugly. A piece of precious diamond that has fallen into one’s eye is nothing but a speck of dust that has to be hurriedly removed, with due care.

The merit of a painting is enhanced or diminished by arrangement of figures and the background in a picture appropriately; avoiding ill-advised depictions.

7. Types of presentations

7.1. The first requisite for a painting is bhu-labha or bhu-lambha the preparation of a proper, smooth, white surface to paint. It could be a canvas (pata), board (phalaka) or a wall (bhitti).

The paintings were executed on various surfaces: wall paintings (bitthi), pictures on board (phalaka), on canvas (pata), on scrolls (dussa-pata) and on palm leaf- manuscripts (patra). The last mentioned, i.e. the scrolls were often in the shape of lengthy rolls facilitating continuous representations. The Chitrasutra instructed that the surface chosen should suit the purpose of the proposed painting; and, in any case, it should be smooth and well coated (anointed). That would help achieve a better presentation of the painting.

7.2. As regards the shapes of the boards and scrolls, Chitrasutra mentions four types: sathya – realistic pictures in oblong frames; vainika – lyrical or imaginative pictures in square frames; naagara -pictures of citizens in round frames; and misra – mixed types.

Sage Markandeya says (41.1-5): Painting is said to be of four kinds:

-

- (1) true to life (Satya);

- (2) of the lute player (Vainika);

- (3) of the city or of common man (Nagara) ; and,

- (4) mixed (Misra).

I am now, going to speak about their characteristics.

Sathyam cha Vainikam chaiva Nagaram Mishra-meva cha / Chitram Chatur-vidham proktham tasya vakshyami lakshanam /3.41.1/

Yath kinchi loka Sadrushyam chitram tatsy ucchate / Dhirga-ange sa-pramanam cha Sukumaram su-bhumikam / 3.41.2/

Chatursram su-sampurnam , na Dhirgam, no ulbano -akriti / Pramanam sthana lamabadyam Vainikam tan nigadyate /3.41.3/

Drudo cha sarvangam vartulam nahya ulbhanam / Chitram tan Nagaram jneyam talpa -malya -vibhushanam /3.41.4/

:- a painting which bears resemblance (Sadrishya) to the things on earth with their proper proportions in terms of their height, their volume (gatra), appearance etc., is the “true to life or naturalistic” (sathya) category of painting. The resemblance should not be mere general; but, it should extend to details, such as all parts of the tree, creeper, mountains or the animals.[ Dr. Sivaramamurti interprets Satya as : “portraying some object of the world that it intends to represent.”]

:- a painting that is rich in details, in display of postures and maintaining strict proportions; and when placed in a well finished square format is called Vainika. It obviously is the delight of the connoisseurs. [In certain editions , the term daisikam is inserted in place of Vainikam, to suggest resembling (sadrsya) provincial or local characteristics.]

:- the Nagara which depicts common folks, is round , with well developed limbs , with scanty garlands and ornaments. ( It could also mean urban, in contrast to daisikam)

:- and, Oh ! The best of men, the Misra derives its name from being composed of the other three categories.

The text again cautions that an artist should not aim to copy. He may depict the resemblance but, more importantly, he should aim to bring out the essence or the soul of the object.

7.3. The concern of the artist should not be to just faithfully reproduce the forms around him. The Chitrasutra was referring to what is now termed as the “photographic reproduction”. It suggested; the artist should try to look beyond the tangible world, the beauty of form that meets the eye. He should lift that veil and look within. The Chitrasutra suggested to him to look beyond “The phenomenal world of separated beings and objects that blind the reality beyond”.

Next:

Chitrasutra continued

Sources and References:

Greatfully acknowledge Shri S Rajam’s sublime paintings

Citrasutra of the Visnudharmottara Purana by Parul Dave Mukherji

Stella Kramrisch: The Vishnudharmottara Part III: A Treatise On Indian Painting And Image-Making. Second Revised and Enlarged Edition ; (Calcutta University Press: 1928)

https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/dspace/bitstream/1887/2668/1/299_022.pdf

Technique of painting prescribed in ancient Indian Texts

The Painter in Ancient India by Dr. C. Sivaramamurti

The Theory of Indian Painting: the Citrasutras, their Uses and Interpretations by Isabella Nardi

I gratefully acknowledge the illustrations of Shri S Rajam

Other images are from internet

sreenivasaraos

September 18, 2012 at 5:00 pm

Thank you Dear marksackler .Regards

sreenivasaraos

September 18, 2012 at 5:04 pm

Dear marktoner1 , Thank you. Regards

Udaya Sankar challa

November 26, 2021 at 3:01 pm

Very nice article on chitrsutra

sreenivasaraos

December 7, 2021 at 11:50 pm

Dear Challa

Thank you for the visit ; and, for the appreciation

Regards

sreenivasaraos

September 18, 2012 at 5:14 pm

Thank you Dear mrhipps .You are welcome .Regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 3:55 am

hello srinivasaraoji,

another exposition of your brilliant acquaintance with our culture. most lucid.impeccable.

i am proud that the beautiful classial-type paintings you have reproduced here are by my uncle (mother’s elder brother) mr.s.rajam who lives in chennai (41, nadu strret, mylapore, chennai 4). he is a great carnatic singer too. he is 89 years old and spends at least 3 hours every day to paint!

cheers, and regards!

vs gopal

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 3:55 am

dear shri gopal,

thank you for reading and for the comments.

i propose to post a series of about six-seven articles on the art of painting in ancient india with particular reference to the chitrasutra of vhishnudharmottara purana. the one you just read and commented was the second in that series. the earlier one was about painting in ancient india and influence of chitrasutra on the artists of ajanta.

i hope to conclude with an article on the legacy of chitrasutra by tracing it to temples of panamalai ,kailasanatha ( kancheepuram), sittannavasal ,brihadeesvara , and vijaynagar. at the end of it i hope write about of shri rajam as the one, in the recent times, who truly inherited, protected, nurtured and kept alive the ancient tradition.

i fondly remember your post on shri rajam which you wrote with love, admiration and justifiable pride. you are blessed.

kindly read the earlier post and follow the rest too. please let me know.

regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 3:59 am

sreenivas:

what wonderful advice on the types of painting to decorate a home ?

the pictures which decorate the homes (including the residential quarters of the king) should display sringara, hasya and shantha rasa. they should exude joy, peace and happiness; and brighten up the homes and lives of its residents. pictures depicting horror, sorrow and cruelty should never be displayed at homes where children dwell.

also

we admire in a divine being are within us. when we respond to those images brought to us in art, we awaken those finer aspects that are latent in us. when we are filled by that grace, there is no space left for base desires and pain: we have become that deity.

there are echoes of advaita even in idol worship

also, in moghul art and in rajasthani and kangra paintings the third dimension was not stressed and most times ignored. i look forward to visiting ajanta to see the third dimension depicted.

incidentally, the main characteristics of the ajanta paintings are the use of free flowing lines for delineating beautiful figures and their delicate inner feelings; together with use of shading different parts of the body to produce three dimensional effects in the images.

also,

correct spatial perception of the objects painted and maintaining a sense of harmony, balance and a sense of proportion within the figure and also in its relation to other figures; and to the painting as a whole.

thoroughly enjoyed the reading !

rgds, girdhar

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 3:59 am

dear shri gopal,

thank you for the comments and the appreciation.

what you mentioned about kangra painting is right; they appear to lack depth and trhree dimensional presentation. they depended more on the grace and beauty of its subjects.

please read rest of the articles too.

regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 4:00 am

dear sreenivasa rao,

i missed thgis ..

some of the statements linking

well being with painting

spatial concepts with painting are quite intriguing..

the statemnt that chitra depicts better the spatial concepts than

shilpa is interesting..thanks…

DSampath

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 4:00 am

dear shri sampath,

pardon me for the delay in responding. thank you for the comments. please also check the fifth one which talks about symbolisms, visualization and personification of objects, in art.

regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 4:01 am

dear sreenivasarao s

this was such an informative post a treasure for keeps … photos of the ancient paintings speak volumes of indian ways of life – their attachment to spirituality from aeon…

thank you tons for the wonderful post

ether

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 4:01 am

dear ether, thank you for the comments and the recommendation. i am glad you read it. the article you just read dealt with certain concepts and theories about painting in india of about 6th century ad. these were also the principles that largely guided the artists of ajanta. regards.

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 4:01 am

shri rao

it is a pleasure to read this part too. especially capturing one’s interest are sections 1.4 and 2.1

on is able to discern the subtle details of the pictures you have posted here and realise that there is the ethereal quality in them despite not being “realistic” like ravi varma’s. indeed, they transcend this plane. yet another interesting note is that many of the pictures are of lord shiva/nataraja’s — going to show that he has been a favourite of artists/connoisseurs all through timeline.

wonderful colourful and interesting presentation. thanks

—

sadly, present day art seldom captures the ethos as in chitrasutra. the likes of mf hussain seem to interpret “freedom” to mean anything other than that of mental liberation!

—

thanks for the input on the art of se asia. as you say, the indian theme with local flavour is seen all over — bright and pleasant they are!

thanks and warm regards…

Riverine

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 4:02 am

dear riverine, thank you for reading and for the recommendation. i am glad you appreciated the subtle concepts and theories of the chitrasutra. regards

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 4:02 am

From: manjari dasi on 29 Jul 2009

Dear Srivas ji,

I stumbled upon your profile today and became delighted to read your in-depth overview of the citrasutra. I am an artist living in Vrndavan, UP and I thought you might be interested to see some things I have been working on. The painting in this message is entitled, “Gopi-Gita” and illustrates a segment of the rasa-panchadhaya from tenth canto of Srimad Bhagavatam. I hope you can enlarge it to view some of the details.

Gopi-Gita by Manjari Dasi

I studied art in America and I’ve been fortunate enough to study with Syamarani didi for the past six years in India. The style combines elements of Indian as well as western art. Her art can be viewed at http://www.bhaktiart,net.

Thanks again for sharing your knowledge of the citrasutra for the public, like myself, to benefit from.

Keep in touch

Sincerely,

Manjari

jai sri radhe

http://www.manjaridasi.wordpress.com

sreenivasaraos

March 20, 2015 at 4:03 am

Dear Manjari Dasi, Thank you very much for the lovely painting. Its concept and technique are both beautiful. You are a very talented and a devoted artist.I appreciates the gift of Love.

As regards Chitra-sutra , I tried to trace the influence of the Chitra-sutra from post-Ajanta period to the present day , in a series of about fourteen articles. Please go through the series starting from:The Legacy of Chitrasutra- One.

Please keep talking.

Regards

Nritya

May 28, 2015 at 11:29 am

Respected Sir,

Thanks for the very informative series.

Vishnudharmotara Purana mentions the dhyana shloka in shilpashastra.

Have you ever come across this particular sholka.

Regards,

Nritya

sreenivasaraos

May 28, 2015 at 1:56 pm

Thank you Dear Nrtya . I am glad you read ( I suppose the entire series) and found it useful.

As regards Dhyana Slokas , there many many indeed in Shilpashastra ( about 2,000 I reckon)

Each deity and each aspect of her/his has a Dhyana Sloka.

For more on that , please check the following and let me know :

https://sreenivasaraos.com/2012/09/09/temple-architecture-devalaya-vastu-part-six-6-of-7/

Cheers and Regards

Nritya

May 28, 2015 at 4:47 pm

Thank you for the pointers !!

Regards.

sreenivasaraos

May 30, 2015 at 4:28 pm

Dear Nitya , thank you.

Please do read other articles in the series and let me know.

Regards

Best Performing art collage in India

April 16, 2016 at 12:02 pm

Really nice to see the Awesome piece of collection of water colour paintings

sreenivasaraos

April 16, 2016 at 4:56 pm

Thanks for visit and the appreciation

I trust you read the articles

Else , please do

Thank you

Regards

ShagunRoyals

April 19, 2016 at 9:16 am

ThankYo Sir.

Excellent blog. Tomorrow is my exam and your blog has helped me alottttt.

ThankYo once again.

sreenivasaraos

April 19, 2016 at 9:26 am

Dear Shagun

T am happy for you. Good Luck and do well in the exam

I trust you read the entire series of six or seven articles

BTW, which is the exam you are taking

Obviously it seems to be art-related

Tell me about it , at your leisure

Cheers

Raj hariom

July 5, 2017 at 10:40 am

sarvottam is very responsive website you can visit us over here.

http://www.shreesarvottam.in/index.php

sreenivasaraos

July 5, 2017 at 12:09 pm

Thanks

Amir Mohtashemi

March 12, 2019 at 11:25 am

That is an excellent blog defining the importance of drawing in the ancient times. It’s like a disciplined way to define feelings & events.

sreenivasaraos

March 12, 2019 at 2:28 pm

Dear Amir

Thank you for the visit and for the appreciation

Please do read the other articles in the series

as also the the articles under the other Series The Legacy of Chitrasutra

Cheers

shriram

August 24, 2022 at 2:33 am

चित्रांचे महत्त्व स्पष्ट करणारा हा उत्कृष्ट ब्लॉग वाचून आनंद झाला.

sreenivasaraos

August 24, 2022 at 3:00 am

Dear Sriram

You are most welcome

Glad you liked this

Regards