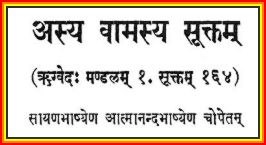

Who Was Dhirgatamas – PART NINE

Verse 43

शकमयम् । धूमम् । आरात् । अपश्यम् । विषुवता । परः । एना । अवरेण । उक्षाणम् । पृश्निम् । अपचन्त । वीराः । तानि । धर्माणि । प्रथमानि । आसन् ॥ R.V. 1.164.43 ॥

śaka-mayam dhūmam|ārāt|apaśyam|viṣu-vatā|paraḥ|enā | avareṇa | ukṣāṇam| pṛśnim | apacanta | vīrāḥ | tāni | dharmāṇi | prathamāni | āsan॥ R.V. 1.164.43 ॥

I beheld near (me) the smoke of burning cow-dung; and by that tall-pervading mean (effect, discovered the cause (fire); the priests have the Soma ox, for such are their first duties

**

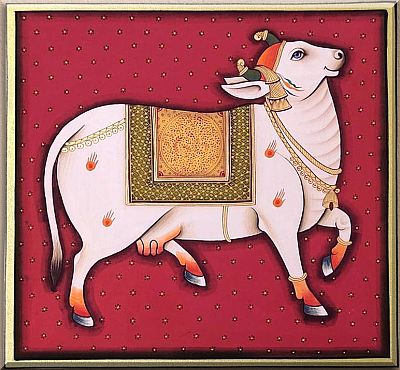

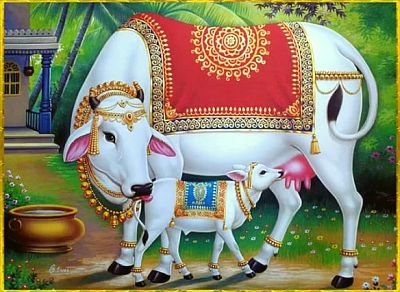

I see (विषुवता) near (आरात्) me the smoke of cow-dung burnt (शकमयम् धूमम्) that is spreading (अवरेण). I know this smoke is caused by the fire. the priests (वीराः -Ritviks) have the white (पृश्निम्) Soma ox, for such are their rituals (तानि–धर्माणि).

*

This verse is said to be about the ritual. One of the explanations is that the white Soma-bull (पृश्निम्) confers on the devotees the desired fruits of action (उक्षाणम्– फलस्य सेक्त्तIरं). The Ritviks who are good in carrying out the rituals (वीराः विविधेरण् कुशलाह) move about and chant loudly. The covering of the smoke spreads wide (विषुवता–व्यप्तिमता) like a cloud (शक).

**

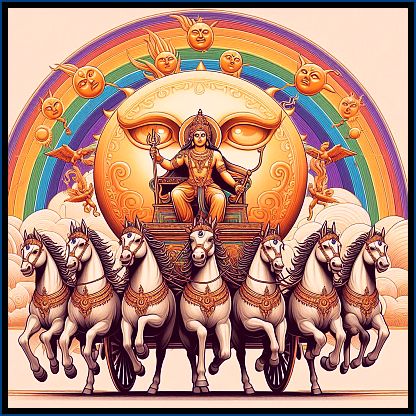

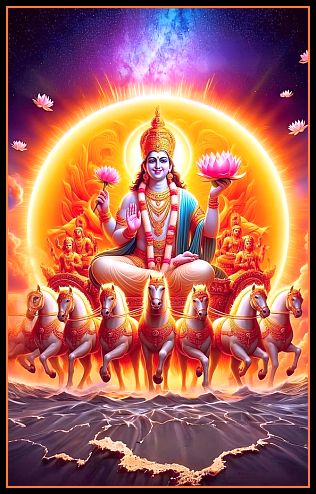

It is also said; the term पृश्निम्— pṛśnim – though some take it to mean Soma, it normally refers to Surya. Then, the Verse would be about the Sun, a kind of Agni, Apam Napatu, (अपां–नपातु) the raging fire, emerging out of the ocean-waters.

**

Dr. Raja has an alternate explanation:

The meaning of the second half is that the heroic ancestors prepared Soma for drink at the Rituals, and this became the earliest Dharma or religious practice.

I am not sure what is meant by the cow-dung and smoke.

**

Verse 44

त्रयः। केशिनः।ऋतुथा ।वि ।चक्षते।सव्ँम्वत्सरे । वपते।एकः। एषाम् ।विश्वम्। एकः। अभिI चष्टे । शचीभिः। ध्राजिः।एकस्य।ददृशे । न । रूपम् ॥R.V. 1.164.44॥

trayaḥ | keśinaḥ | ṛtu-thā | vi | cakṣate | saṃvatsare | vapate | ekaḥ | eṣām | viśvam | ekaḥ | abhi | caṣṭe | śacībhiḥ | dhrājiḥ | ekasya | dadṛśe | na | rūpam ॥R.V. 1.164.44॥

The three, with beautiful tresses, look down in their several seasons upon the earth; one of them, when the year is ended, shears (the ground); one, by his acts, overlooks the universe; the course of one is visible, though not his form

**

Three (त्रयः) deities with long beautiful stresses, long matted locks (केशिनः–Keshin), appear according to seasons (ऋतुथा). One of them (एषाम्) when the year (सव्ँम्वत्सरे) is ended sheers (वपते) the earth. Of the other one (एकस्य), the course (ध्राजिः) of his sweep is seen; but not his form (न– रूपम्) . One of them has a vision of the universe (विश्वम्) and oversees (वि– चक्षते) with his powers (अभिI चष्टे).

*

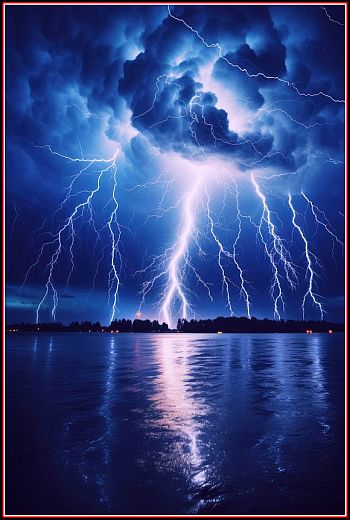

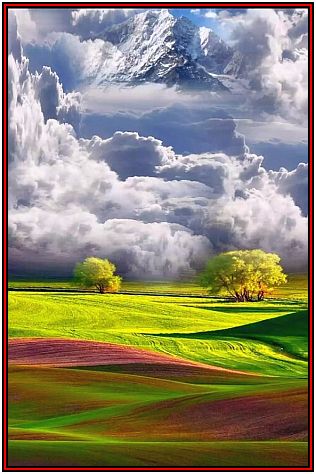

Agni, on earth, has flame-like tresses (केशिनः-Keshin) . Vayu, who occupies the mid-regions (अन्तरिक्ष्-Antariksha) has flashes of lightning as his curls. Adiya, the Lord of the Dyu-Loka (skies) shines with his brilliant rays. These – the flames; the flashes of lightning; and the rays- enhance their glory. Therefore, they are the Keshins (केशिनः).

Here, the three forms of the Supreme are mentioned. Each has its own functions. Yet, they are not independent; they are aspects of One Absolute Being.

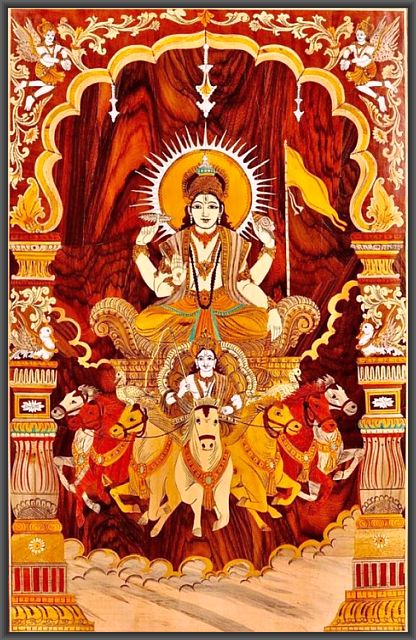

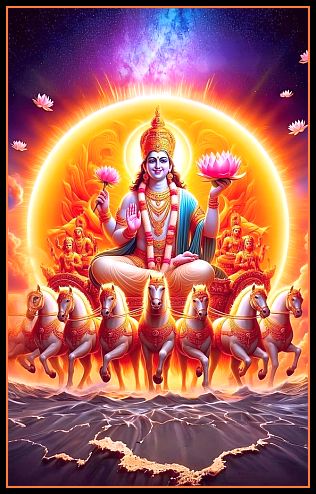

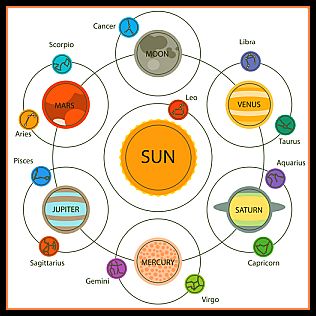

The three deities referred to in this Verse are Agni, Vayu and Surya.

Sri Sayana explains the three are the three forms of Agni, who burns up the earth; the Sun, who revives it by his light and by the rain which he sends down; and Vayu, the wind, who contributes to the showers of rain.

Yaskacharya had also earlier explained that there is indeed only One Deity; and, that Deity manifests in the three worlds as Surya (Sun) in heaven (Dyu-Loka); Indra or Vayu (wind) in the middle region (Antariksha); and, Fire on the earth (Bhu-Loka). They are the basic foundations of our existence.

In the opening Verse of Asya Vamasya Sukta, similar ideas were expressed. There, the three luminaries in three regions were called as three brothers; who indeed are the three forms of Fire: Agni, Vayu (Air) and Aditya (Sun).

अस्य । वामस्य । पलितस्य । होतुस्तस्य । भ्राता । मध्यमो । अस्त्यश्नः। तृतीयो । भ्राता । घृतपृष्ठो । अस्यात्रापश्यं । विश्पतिं सप्तपुत्रम् ॥ १.१६४.०१ ॥

The three brothers or the three aspects of Agni (Agni-traya)- The Sun, the Lightning and the Fire – form the Tripod of Life. They exist and function together.; and, are the basic factors of our existence

Of these three brothers; Aditya (Sun) shining in the upper regions – parastat, the protector (पलितस्य) of the Universe, who is worshipped by all (वामस्य), is the Supreme.

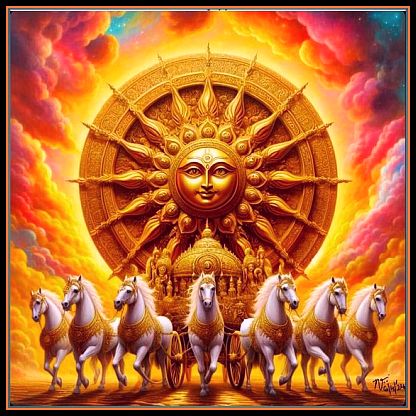

There, Dhirgatamas had said that the Sun, blazing with dazzling radiance and warmth, is the oldest of the three; and is the first cause. This Sun, held up and propelled by its inherent force (स्वध Svadha), clad in its own splendor, travels in all the worlds, without stoppage.

अनत् । शये । तुरगातु । जीवम् । एजत् । ध्रुवम् । मध्ये । आ । पस्त्यानाम् । जीवः। मृतस्य। चरति । स्वधाभिः । अमर्त्यः । मर्त्येन । सयोनिः ॥१.१६४.३० ॥

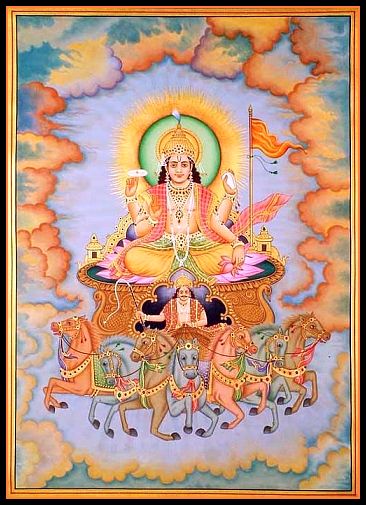

In the hymns of the Rigveda, Sun (Surya) is celebrated as the Soul (Atman) of all that moves or is immoveable; enlivening the heaven, the earth, and all the surrounding space –

अप्राः । द्यावापृथिवी इति । अन्तरिक्षम् । सूर्यः । आत्मा । जगतःतस्थुषः । च ॥ – Rig Veda 1.115.1 .

He is the Divine power in the heavens; the Lightening in the atmosphere; and the Fire on Earth. These are the three main manifestations of light in our visible world.

Sun moves in its orbit, which itself is moving. Earth and other bodies move around sun due to the force of attraction (आकर्षण)

**

Verse 45

चत्वारि । वाक् । परिमिता । पदानि । तानि । विदुः । ब्राह्मणाः । ये । मनीषिणः । गुहा । त्रीणि । निहिता । न । इङ्गयन्ति । तुरीयम् । वाचः । मनुष्याः । वदन्ति ॥ R.V. 1.164.45॥

catvāri | vāk | pari-mitā | padāni | tāni | viduḥ | brāhmaṇāḥ | ye | manīṣiṇaḥ | guhā | trīṇi | ni-hitā | na | iṅgayanti | turīyam | vācaḥ | manuṣyāḥ | vadanti |

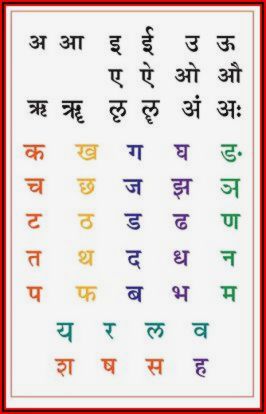

Four are the definite grades of speech; those who are wise know them; three, deposited in secret, indicate no meaning; men speak the fourth grade of speech

**

Speech (वाक्) is graded (पदानि) as four regulated levels (चत्वारि परिमिता) ; the seers or the poets who have intuition know (विदुः) them. Three of them (त्रीणि), not clearly known (निहिता –न – इङ्गयन्ति), concealed in the cave (गुहा), do not move; the fourth of the speech (वाचः तुरीयम्), men speak (मनुष्याः वदन्ति).

**

This theory of the four-fold division of speech or the four stages in the development of sounds – three being internal and the fourth one external uttered sound – is much discussed by a number of scholars of various Schools of though. Each scholar, according to his inclination, has offered his own explanation.

**

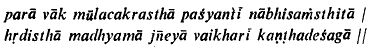

One of the explanations is that While the Grammarians, generally, speak about three levels of speech, the philosophers identify four levels or stages of speech (Vac): Para, Pashyanti, Madhyama and Vaikhari.

Of these four forms of Vac, Para and Pashyanti are the subtle forms of Vac; while Madhyama and Vaikhari are its gross forms.

While Para Vac is pure consciousness; the three other forms are its transformations. The three lower forms of speech viz. Pashyanti, Madhyama and Vaikhari which correspond to intention, formulation and expression are said to represent its powers, such as:

Iccha Shakthi (power of intent or the will), Jnana-Shakthi (power of knowledge) and the power of becoming (bhuti-shakthi) or the power of action (Kriya-Shakthi).

Thus, out of the transcendent Para, the three phases of its power (Shakthi) emanate.

**

The notion that there are four quarters or four levels of existence; and of which, only one quarter is within the experience of mortals also appears in the Purusha-sukta (Rig-Veda 10.90.3) ascribed to Rishi Narayana – Paadosya Vishva Bhutaani Tri-Paada-Asya-Amrtam Divi.

There are similar notions with regard to Pranava-Om where the three syllables A, Vu, and Ma (अ–उ–मा) are normally visible. But it is its fourth element the Anusvara (Brahma-Bindu) that leads from being to non-being; and, from the word to the silence beyond it.

svarena samdhayed yogam asvaram bhävayet param asvarena hi bhävena bhävo näbhäva isyate– Brahma Bindu Upanishad

The Maitrayaniya (Maitri) Upanishad (1, 11.5), of Krishna-Yajur-Veda, mentions the four quarters of speech as those belonging: to the upper region – the heavens (Divi); to the intermediate space (Antariksha); and, to the region of earth (Prithvi) as spoken by the humans (Manusi); and, to the animals (Pashu)

– vāk sṛṣṭā caturdhā vyabhavad eṣu lokeṣu trīṇi turīyāṇi paśuṣu turīyaṃ yā pṛthivyāṃ sāgnau sā rathantare yāntarikṣe.

The Atma-vadins (mainly those belonging to Nyaya and Vaisesika Schools) say: the four-fold speech can be found in the animals; in musical instruments (such a flute); in the beasts; and, in the individuals (Atmani)

– pasusu tunavesu mrgesu atmani ca iti atmavadinah

The Shatapatha Brahmana (1.3.16) categorizes the speech into four kinds: as that of the humans; of animals and birds (vayamsi); of reptiles (snakes); and, of small creeping things (kshudram sarisrpam)

– varṣā vā iḍa iti hi varṣā iḍo yadidaṃ kṣudraṃ sarīsṛpaṃ 1.5.3.11

Similarly, those who believe in myths and legends say that – the serpents; birds; evil creatures; as also the humans in their dealings with the rest of the world – all use speech of their own.

Sarpanam vagvayasam ksudrasarispasya ca caturthi vyavaharika-ityaitihasikah

The Jaiminiya-Upanishad-Brahmana (1.40.1) deals with the four levels of speech in a little more detail.

In a verse that is almost identical to the one appearing in Rig-Veda Samhita – 1.164.45, it mentions that the discriminating wise know of four quarters of speech. Three of these remain hidden; while the fourth is what people ordinarily speak.

Chatvaari vaak parimitaa padaani / taani vidur braahmaanaa ye manishinaah. Guhaa trini nihita nengayanti / turiyam vaacho manushyaa vadanti //

Then, the text goes on to explain that of the four quarters of speech: mind is a quarter, sight is another quarter, hearing is the third quarter; and, speech itself is the fourth quarter.

tasya etasyai vaco manah padas caksuh padas srotram pado vag eca caturtah padah

Further, it says: what he thinks with the mind, that he speaks with speech; what he sees with the sight, that he speaks with the speech; and, what he hears with hearing, that he speaks with speech.

tad yad vai manasa dyayanti tad vaco vadati; yac caksus pasyati tad vaca vadati; yac srotrena srunoti tad vaco vadati /

Thus, finally, all activities of senses unite (Sam) into speech. Therefore, speech is the Saman.

Nagesh Bhatta (Ca. 1670 to 1750), in his commentary on Patanjali’s Mahabhashya, accepts the four forms of Vac; and, explains the expression ‘Catvari padjatani namakhyato-upasargani-patah ‘as referring to Para, Pashyanti, Madhyama and Vaikhari:

Bhashya padajatani Para-Pashyanti-Madhyama- Vaikhari rupani / ata evagre nipatah ceti cakarah sangacchate

**

Sri Sayana in his Rig-Bhashya deals with the subject of four levels of speech in a greater detail.

The various ancient texts speak of the levels of speech, which, generally, are taken to be four. Each School – Grammarians, Mimamsa, Upanishads, Tantra, Yoga, mythology etc – offers its own understanding and explanation of the four levels of speech.

These levels are variously explained as the varieties of speech that are said to be spoken either in four regions of the universe; or spoken by divine beings and humans; or as speech of the humans, animals, birds and creatures.

These four are even explained as four levels of consciousness.

He says, people use speech in a variety of ways to fulfil their roles and responsibilities in life. And, similarly, the animals, birds, creatures and objects in nature do use their own sort of speech to serve their needs.

**

च॒त्वारि॒वाक्परि॑मिता प॒दानि॑ –Catvāri vākparimitā padāni: –

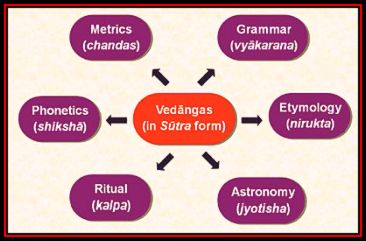

The four types relate to the language of the Vedic mantras; the Kalpas; the Brahmana texts; and laukika, or current day-to-day speech (Taittirīya Samhita 1.31.2).

मन्त्र कल्पो ब्राह्मणं चतुर्था व्य्वहरिकीति यग्निक

Here, मन्त्र कल्पो ब्राह्मणं are Vedic speech. The fourth one is used by humans in worldly transactions – तुरीयं वाचो मनुष्य वदन्ति

*

Only those Yogis, mystics or the wise who are acquainted with the Shabda-Brahma, the ultimate Vac, know the fourth level of speech. It is only such realized wise seers speak both languages, that of the gods and that of men-

तस्माद् ब्राह्मणं उभयो वाचम् वदन्ति वा च देवानामं वा च मनुस्यनाम् – tasmād brāhmaṇā ubharyo vācam vadanti yā ca devānām yā ca manuṣyāṇam (Nirukta 13.9)

Vac: speech, was created fourfold, three kinds of which are in the three regions, the fourth amongst the mortals.

- The form on earth, associated with Agni is in the Rathantara;

- the form in the firmament, associated with Vayu, is in the Vāmadevya mantras;

- that which is in heaven, with Aditya, is Bṛhatī, or in the thunder (stanayitnau);

- whatever else was placed amongst the humans and animal-life

*

He then, while explaining these four levels or quarters of speech (ani tani catwari itya atra bahavah), remarks that each School offers explanations (bahudha varnayanti) according to its own tenets (sva- sva-mantanu-rodhena).

Next, he briefly mentions what those explanations are:

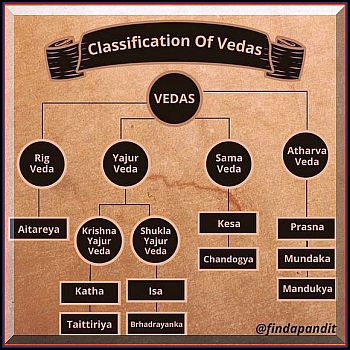

: – According to Vedantins, the four levels of speech could be the Pranava (Aum) – which is the sum and substance of all the Vedic terms (sarva-vaidika-vag-jalasaya), followed by three Vyahritis (Bhu-Bhuh -Suvah). Thus, the Pranava along with three Vyahritis form the four quarters of speech.

: – According to Nirukta (Etymology), the language of the three Vedas (Rik, Yajus and Saman ) and the speech commonly used for dealings in the world , together make the four quarters of speech – (Rg-yajuh-samani-caturdhi vyavharikiti nairuktah – 13,8 )

: – The four levels of speech could also be related to four regions representing four deities: on the Earth as Agni (yo prthivyam sa-agnau); in the mid-air as Vayu (Ya-antarikshe sa vayau); and, in the upper regions as Aditya (Ya divi saditye). And, whatever that remains and transcends the other three is in Brahman (Tasya-mad-brahmana).

: – The speech, though it is truly indivisible, is measured out or analyzed in the Grammar as of four kinds or four parts-of-speech (akhandayah krtsnaya vacah caturvidha vyakrtattvat). Accordingly, the four divisions of speech are named by the followers of the various Schools of Grammar (vyakarana-matanus-arino) as: Naaman (Nouns), Akhyata (Verbs), Upasarga (prepositions or prefixes) and Nipata (particles)

: – According to the wise who are capable of exercising control over their mind; the Yogis who have realized Sabdabrahman; and, others of the Mantra (Tantra) School, these four levels of speech (Evam catvari vacah padani parimitani) are classified as : Para, Pashyanti, Madhyama and Vaikhari.

Manisinah manasah svaminah svadhinamanaska brahmana vacyasya sabdabrahmani dhigantaro yoginah paradicatvari padani viduh jananti

Apare-mantrkah-parkarantarena-pratipadanti-Para-Pasyanthi-Madhyama-Vaikari Chatvari

**

Verse 46

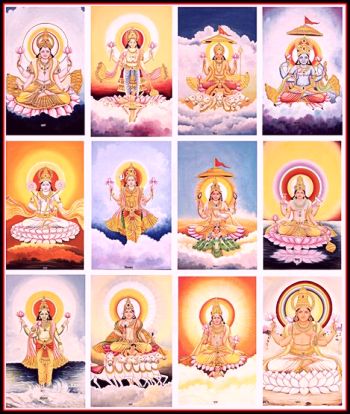

इन्द्रम् । मित्रम् । वरुणम् । अग्निम् । आहुः । अथो इति । दिव्यः । सः । सुपर्णः । गरुत्मान् । एकम् । सत् । विप्राः । बहुधा । वदन्ति । अग्निम् । यमम् । मातरिश्वानम् । आहुः ॥R.V. 1.164.46॥

indram | mitram | varuṇam | agnim | āhuḥ | atho iti | divyaḥ | saḥ | su-parṇaḥ |garutmān| ekam | sat | viprāḥ | bahu-dhā | vadanti | agnim | yamam | mātariśvānam | āhuḥ |

Truly there is only One. They may call Him by any names. They call him, as Indra, Mitra, Varuna, and he is the celestial, winged-bird (Sun); names as they speak of Agni, Yama, Mātariśvan. The learned priests call the One and the only one by many names

**

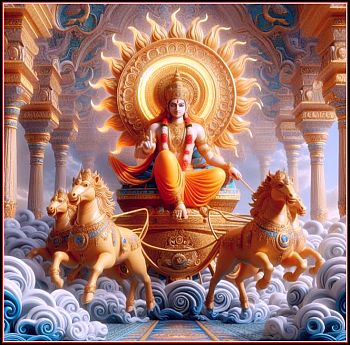

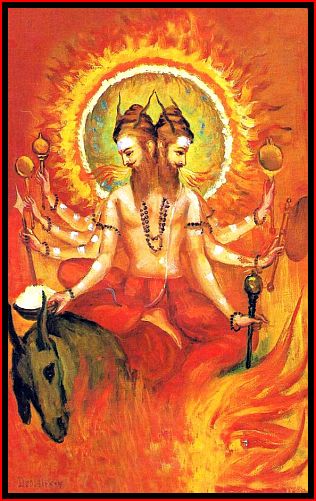

The One Aditya (आहुः) is called by various names as: Indra, Mitra, Varuna and Agni (इन्द्रम् – मित्रम् –वरुणम् –अग्निम्). And, again (अथो इति), he is also the beautiful-winged celestial bird Garutman (गरुत्मान्), Garuda (सुपर्णः Suparna) of graceful flight. The wise ones (विप्राः) speak of in many ways (बहुधा वदन्ति); call (आहुः) the One (Supreme Being (एकम् सत्) in many names as Agni, Yama, Matarisvan. (अग्निम् –यमम्– मातरिश्वानम्)

This verse is a thread that ties together the Deva-Vidya with Brahma-Vidya. It celebrates the essential unity of celestial beings (Devas) as various manifestations of One and the Only One Supreme Principle (Parama-tattva). All the gods are different forms of the same Paramatman. The worship offer ed to different gods is indeed the worship of That One.

Sri Sayana identifies that supreme Being as Surya; while, earlier, Yaska had described him as Agni.

But, again, it also said the Agni and Aditya are indeed one.

In any case, all the divinities are the manifestations of One and Only One Supreme Principle (Parama-tattva)

**

Verse 47

कृष्णम् । नियानम् । हरयः । सुपर्णाः । अपः । वसानाः । दिवम् । उत् । पतन्ति । ते । आ । अववृत्रन् । सदनात् । ऋतस्य । आत् । इत् । घृतेन । पृथिवी । वि । उद्यते ॥R.V. 1.164.47॥

kṛṣṇam | ni-yānam | harayaḥ | su-parṇāḥ | apaḥ | vasānāḥ | divam | ut | patanti | te | ā | avavṛtran | sadanāt | ṛtasya | āt | it | ghṛtena | pṛthivī | vi | udyate |

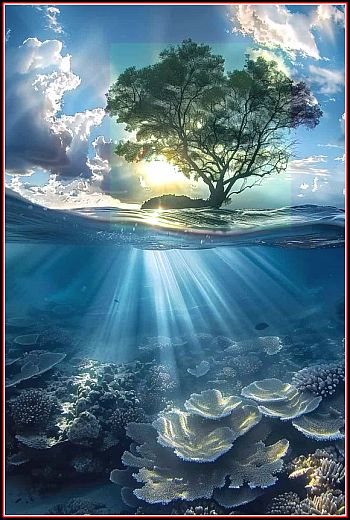

The smooth-gliding waters (of the rain, the solar rays), clothing the waters with a dark cloud, ascend to heaven; they come down again from the dwelling of the rain, and immediately the earth is moistened with water.

**

The smooth gliding rays (सुपर्णाः) carry water(हरयः). They cover(वसानाः) the dark clouds (कृष्णम्) moving steadily(नियानम्) carrying water (अपः). They spread upward (उत् । पतन्ति) towards the heaven (दिवम्). They return from the Sun (आ । अववृत्रन्), the home of all waters (सदनात् ऋतस्य). Immediately (आत्–इत्) the Earth(पृथिवी) is awash with water (घृतेन उद्यते).

**

According to Sri Sayana : Rigveda Sayana Bhashya

The Aditya has two courses: उत्तरायण (Uttara Yana) and दक्षिणायन (Dakshina Yana) . The former is also called शुक्ल (Shukla); and, the latter as कृष्णं (Krishna).

The night of the gods is दक्षिणायन. And, when the Sun follows the उत्तरायण course , his rays spread over the universe absorb water from all sources; and reach back Aditya by night – that is – by दक्षिणायन. This is the rainy season for the earth. There will be plenty of rains during this season.

यद्वा कृष्णं नियाम नियमनम् रात्रिः / देवानां हि रात्रिहि दक्षिणायनम् / तत्प्र तस्मिं वर्षकाले इयर्थः

ऋतस्य सदनात् – उदकस्य स्थानदादि आदित्य मण्डलात्

Yaska-charya in his Nirukta chose to relate tis verse to Agni.

He said Agni ascends to the sky in the form of smoke; it becomes a cloud; pours down the rain, while returning from the solar region, in the form of rays

Either facing up or moving downward, he rays are indeed called Suparna (सुपर्णाः), moving with grace.

vavṛtrant.sadanād.ṛtasya.āt.it.ghṛtena.pṛthivī.vyudyate 7,24: ”

kṛsnam.nirayanam.rātrir.ādityasya,.harayaḥ.suparṇā.haranā.āditya.raśmayah,.te.yadā.amuto.arvāñcaḥ.paryāvartante.saha.sthānād.udakasya.ādityād,.atha.ghṛtena.udakena.pṛthivī.vyudyate/[820]

yatra.suparṇāḥ.supatanā.āditya.raśmayaḥ.amṛtasya.bhāgam.udakasya.animisantas.vedanena.abhisvaranti.iti.vā.abhiprayanti.iti. vā

vayo.ver.bahuvacanam.suparṇāḥ.supatanā.āditya.raśmi1.upasedur.indram.yācamānāh

Verse 48

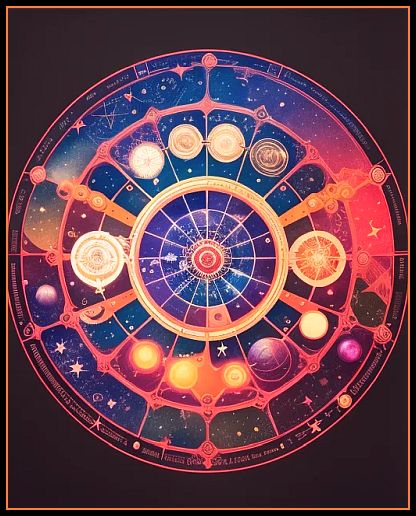

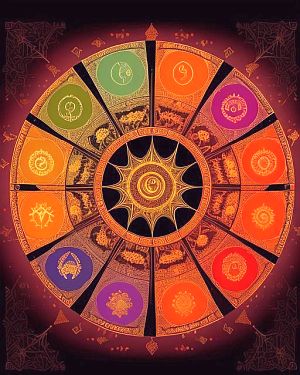

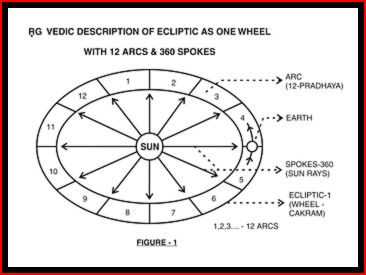

द्वादश । प्रधयः। चक्रम् । एकम् । त्रीणि । नभ्यानि । कः । ऊँ इति । तत् । चिकेत । तस्मिन्। साकम् । त्रिशताः । न । शङ्कवः । अर्पिताः । षष्टिः । न । चलाचलासः ॥R.V. 1.164.48॥

dvādaśa | pra-dhayaḥ | cakram | ekam | trīṇi | nabhyāni | kaḥ | oṃ | iti | tat | ciketa | tasmin | sākam | tri-śatāḥ | na | śaṅkavaḥ | arpitāḥ | ṣaṣṭiḥ | na | calācalāsaḥ

The fellies are twelve; the wheel is one; three are the axles; but who knows it? within it are collected 360 (spokes), which are, as it were, moveable and immoveable

The spokes (प्रधयः) are twelve (द्वादश); the wheel (चक्रम्) is one(एकम्); three are the axles (त्रीणि–नभ्यानि); but who indeed has known this? (तत्–चिकेत)? within it (तस्मिन्) are revolving (चलाचलासः) 360 (त्रिशताः षष्टिः spokes), which are, as it were, moveable and immoveable; not in the least shaking joined together (साकम् अर्पिताः).

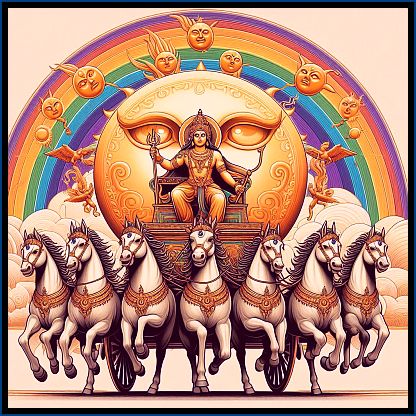

This verse , again, describes Aditya picturized as a Time-wheel (Samvathsara Chakra) , whose one revolution makes a year. . It has twelve spokes, three axels, hold together 360 spokes joined to them

-द्वादश । प्रधयः परिधय तत् स्थानीया द्वादश मासाह

The twelve spokes represent twelve months in a year or the twelve Rashis (Zodiac signs). , with 360 pairs of day and night.-

त्रीणि- नभ्यानि – नभ्याश्रयIणी फलकानि तत् स्थानियानि ग्रीष्म वर्षा हेमन्त ख्यायश्रितानि

The three Nabhis indicate here , the three seasons (Ritus) -summer , rains and winter (ग्रीष्म वर्षा हेमन्त ).

Or, it might be the three junctions (सन्ध्याहः) in time – past, present and future tenses

Well, who is there to that truly knows the secret – कः तत् चिकेत कोपि महान जानति ? !!

Sri Sāyaṇa in his Ṛgveda-bhāṣya says that 360 moves on and on ; revolves; repeats itself – चलI चलIसह

**

Verse 49

यः । ते । स्तनः । शशयः । यः । मयःभूः । येन । विश्वा । पुष्यसि । वार्याणि । यः । रत्नधाः । वसुवित् । यः । सुदत्रः । सरस्वति । तम् । इह । धातवे । करिति कः ॥R.V. 1.164.49॥

yaḥ | te | stanaḥ ḥ śaśayaḥ | yaḥ | mayaḥ-bhūḥ | yena | viśvā | puṣyasi | vāryāṇi | yaḥ | ratna-dhāḥ | vasu-vit | yaḥ | su-datraḥ | sarasvati | tam | iha | dhātave | karitikaḥ |

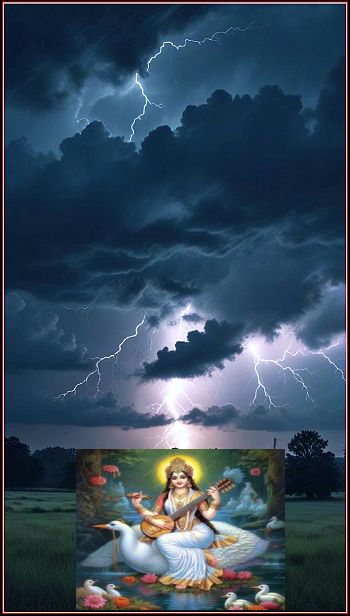

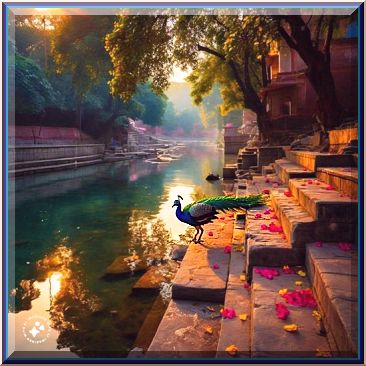

Sarasvati, that retiring breast, which is the source of delight, with which you bestow all good things, which is the container of wealth, the distributor of riches, the giver of good (fortune); that (boon) do you lay open at this season for our nourishment

**

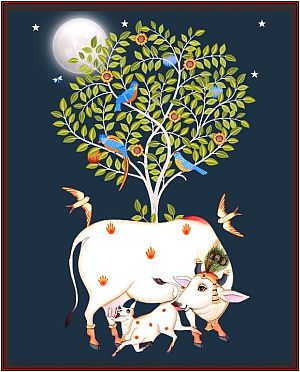

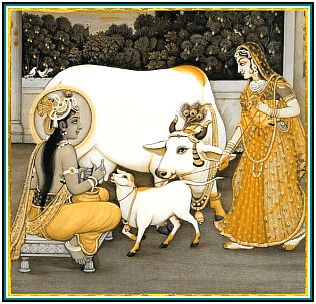

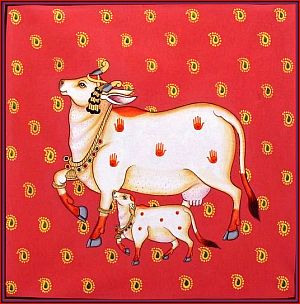

The Deity here is Sarasvati. Here, Goddess Sarasvathi is described as a mother. We had some reference to mother and child in previous verses (5, 7, 8, 9, 0, 11, 26, 27, 28). Mother, cow, water and many ideas refer more or less to the same thing.

**

There are four kinds of references to Vac in Rig Veda:

- Vac is speech in general;

- Vac also symbolizes cows that provide nourishment;

- Vac is also primal waters prior to creation; and,

- Vac is personified as the goddess revealing the word.

Commencing with the Brahmana-texts, Vac gets identified with Sarasvathi the life-giving river; the goddess of learning and wisdom; as also with Vac.

**

The name Saraswati (सरस्वती) indicates one who is associated water (सरस्) or that which is fluid Salila (सलील). When the term is taken as a composite word of Sarasu-ati (सरसु+अति) it also means one with plenty of water (उदकम्).

In the Nighantu (1.12), Sarah is one of the synonyms for water. That list of synonyms for water, in the Nighantu, comes immediately next to that of the synonyms for speech (Vac).

Yaska also confirms that the term Sarasvathi primarily denotes the river (Sarasvathi Sarah iti- udakanama sartes tad vati –Nirukta.9.26). Thus, the word Sarasvathi derived from the word Sarah stands for Vagvathi (Sabdavathi) and also for Udakavathi

*

Vac is sometimes identified with waters, the primeval principle for the creation of the Universe.

In the Vak Suktha or Devi Suktha of Rig Veda (RV.10. 10.125), Apah, the waters, is conceived as the birth place of Vac. And, Vac who springs forth from waters touches all the worlds with her flowering body and gives birth to all existence. She indeed is Prakrti. Vac is the creator, sustainer and destroyer. In an intense and highly charged superb piece of inspired poetry Vac declares “I sprang from waters there from I permeate the infinite expanse with a flowering body. I move with Rudras and Vasus. I walk with the Sun and other Gods. It is I who blows like the wind creating all the worlds”.

*

In initial passages of the Rigveda, the word Sarasvati refers to the river “Best of mothers, the best of rivers, best of goddesses” (अम्बितमे नदीतमे देवितमे सरस्वति – Rigveda 2.41.16)

In the Rig-Veda, Sarasvathi is the name of the celestial river par excellence (deviyā́m), as also its personification as a goddess (Devi) Sarasvathi, filled with love and bliss (bhadram, mayas).

And Sarasvathi is not only one among the seven sister-rivers (saptásvasā), but also is the dearest among the gods (priyā́ deveṣu).

Again, it is said, the Sarasvathi as the divine stream, has filled the earthly regions as also the wide realm of the mid-world (antárikṣam) –

- āpaprúṣī pā́rthivāni urú rájo antárikṣam | sárasvatī nidás pātu | RV_6,061.11)

Invoked in three full hymns (R V.6.6.61; 7.95; and 7.96) and numerous other passages, the Sarasvathi, no doubt, is the most celebrated among the rivers.

*

In the Aitareya Brahmana (3.37) Vac is directly identified with the life-giving Sarasvathi (vag vai Sarasvathi).

The Vac-Sarasvathi in the form of river (Sarasvathi-nadi-rupe) is the generous (samrudhika) loving and life-giving auspicious (subhage) splendid Mother (Mataram sriyah), the purifying (pavaka) source of great delight (aahladakari) and happiness (sukhasya bhavayitri) which causes all the good things of life to flourish.

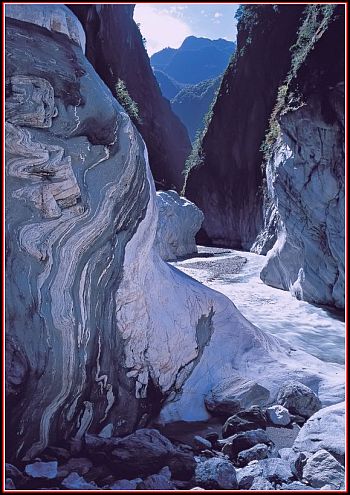

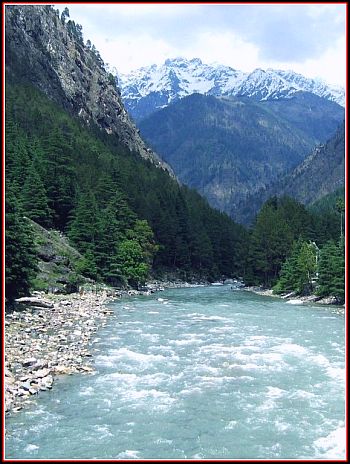

There are abundant hymns in the Rig-Veda, singing the glory and the majesty of the magnificent Sarasvathi that surpasses all other waters in greatness, with her mighty (mahimnā́, mahó mahī́) waves (ūrmíbhir) tearing away the heights of the mountains as she roars along her way towards the ocean (ā́ samudrā́t). She is the swiftest among the speediest- vegavatinam vegavattama .

Sarasvathi is loud and powerful flood who roars like a bull and cannot be controlled.

She is the one bursting the ridges of the hills (paravataghni) with mighty waves – yásyā anantó áhrutas tveṣáś cariṣṇúr arṇaváḥ | ámaś cárati róruvat | (RV_6,061.08

Pra-ya-mahimna-mahinasu-cekite-dyumnebhiranya-apasamapastama – the one whose powerful limitless (yásyā anantó) , unbroken (áhrutas) swiftly flowing (cariṣṇúr arṇaváḥ) impetuous resounding current and roaring (róruvat) floods, moving with rapid force , like a chariot (rathíyeva yāti), rushes onward towards the ocean (samudrā́t) with tempestuous roar; .. and so on.

Rishi Gṛtsamada adores Sarasvathi as the divine (Nadinam-asurya), the best of the mothers, the mightiest of the rivers and the supreme among the goddesses (ambitame nadltame devitame Sarasvati). And, he prays to her: Oh, Mother Saraswati, even though we are not worthy, please grant us merit.

Ámbitame nádītame dévitame sárasvati apraśastā ivasmasi praśastim amba naskṛdhi – (RV_2,041.16)

Sarasvathi is the most sacred and purest among rivers (nadinam shuci). Prayers are submitted to the dearest (Priya tame) seeking refuge (śárman) in her – as under a sheltering tree (śaraṇáṃ vr̥kṣám). She is our best defence; she supports us (dharuṇam); and, protects us like a fort of iron (ā́yasī pū́ḥ). She is most liberal to her friends (Uttara sakhibhyah).

The Sarasvathi, the river that outshines all other waters in greatness and majesty is celebrated with love and reverence; and, is repeatedly lauded with choicest epithets, in countless ways:

The Sarasvathi, most beloved among the beloved (priyā́ priyā́ su) is the ever-flowing bountiful (subhaga; vā́jebhir vājínīvatī) energetic (balavati) stream of abounding beauty and grace (citragamana citranna va) which purifies and brings fruitfulness to earth, yielding rich harvest and prosperity (Sumrdlka). She is the source of Vigor and strength.

Her waters which are sweet (madhurah payah) have the life-extending (ayur-vardhaka) healing (roga-nashaka) medicinal (bhesajam) powers – (aps-vantarapsu bhesaja-mapamuta prasastaye – RV_1,023.19).

She is indeed the life (Jivita) and also the nectar (amrtam) that grants immortality. Sarasvathi, our mother (Amba! yo yanthu) the life giving maternal divinity, is dearly loved as the benevolent (Dhiyavasuh) protector of the Yajna – Pavaka nah Sarasvathi yagnam vashtu dhiyavasuh (RV_3,003.02).

She personifies purity (Pavaka). Sarasvathi is depicted as a purifier (pavaka nah sarasvathi) – internal and external. She purifies the body, heart and mind of men and women- viśvaṃ hi ripraṃ pravahanti devi-rudi-dābhyaḥ śucirāpūta emi | (10.17.20); and inspires in them pure, noble and pious thoughts (1.10.12). Sarasvathi also cleanses poison from men, from their environment and from all nature –

uta kṣitibhyo, avanīr avindo viṣam ebhyo asravo vājinīvati (RV_6,061.03).

Prayers are submitted to Mother Sarasvathi, beseeching her: please cleanse me and remove whatever sin or evil that has entered into me. Pardon me for whatever evils I might have committed, the lies I have uttered, and the false oaths I might have sworn.

Idamapah pravahata yat kimca duritam mayi, yad vaaham abhi dudroha, yad va sepe utanrtam (RV.1.23.22)

The beauty of Sarasvathi is praised through several attributes, such as: Shubra (clean and pure); Suyanam, Supesha, Surupa (all terms suggesting a sense of beauty and elegance); Su-vigraha (endowed with a beauteous form) and Saumya (pleasant and easily accessible). Sri Sayana describes the beauteous form of Sarasvathi: “yamyate niyamytata iti yamo vigrahah, suvigraha…”

Sarasvathi is described by a term that is not often used: ’ Vais’ambhalya’ , the one who brings up, nurtures and protects the whole of human existence – visvam prajanam bharanam, poshanam – with abundant patience and infinite love.

Sri Sayana, in his Bhashya (on Taittiriya-Brahmana, 2. 5.4.6) explains the term as: Vlsvam prajanam bharanam poshanam Vais’ambham tatkartum kshama vaisambhalya tidrsi.

Thus, the term Vais’ambhalya, pithily captures the nature of the nourishing, honey-like sweet (madhu madharyam) waters of the divine Sarasvathi who sustains life (vijinivathi); enriching the soil ; providing abundant food (anna-samrddhi-yukte; annavathi) and nourishment (pusti) to all beings; causing overfull milk in cows (kshiram samicinam); as Vajinivathi enhancing vigour and strength in horses ( vahana-samarthyam) ; and , blessing all of existence with happiness (sarvena me sukham ) – (Sri Sayana’s Bhashya on Taittiriya-Brahmana).

Yaska mentions that Sarasvathi is worshipped both as the river (Nadi) and as the goddess (Devata) –

vāc.kasmād, vaceh / tatra. sarasvatī. ity. etasya. nadīvad. devatāvat . ca . nigamā. bhavanti. tad. yad. devatāvad. uparistāt. tad .vyākhyāsyāmah / atha . etat. nadīvat/ /– Nirukta.2.23

Thus, Sarasvati is a river at first; and, later conceived as a goddess

Sarasvathi, the best of the goddesses (Devi-tame) and the dearest among the gods (priyā́ deveṣu) is associated with Prtri-s (departed forefathers – svadhā́ bhir Devi pitŕ̥bhir; sárasvatīṁ yā́m pitáro hávante) as also with many other deities and with the Yajna.

She is frequently invited to take seat in the Yajnas along with other goddesses such as: Ila, Bharathi, Mahi, Hotra, Varutri, Dishana Sinivali, Indrani etc.

She is also part of the trinity (Tridevi) of Sarasvathi, Lakshmi and Parvati.

Sarasavathi as Devata, the Goddess is also said to be one of the three aspects of Gayatri (Tri-Rupa-Gayatri): Gayatri, Savitri and Sarasvathi.

Here, while Gayatri is the protector of life principles; Savitri of Satya (Truth and integrity of all Life); Sarasvathi is the guardian of the wisdom and virtues of life.

Among these Tisro Devih, Sarasvathi, the mighty, illumines with her brilliance and brightness, inspires all pious thoughts – cetantī sumatīnām (RV.1.3.12 ;).

Her aspects of wisdom and eloquence, which enlighten all this world (dhiyo viśvā vi rājati), are praised, sung in several hymns. She evokes pleasant songs, brings to mind gracious thoughts; and she is requested to accept our offerings (RV.1.3.11)

codayitrī sūnṛtānāṃ cetantī sumatīnām | yajñaṃ dadhe sarasvatī ||maho arṇaḥ sarasvatī pra cetayati ketunā | dhiyo viśvā vi rājati ||RV.1.3.11-12

According to Sri Sayana, Sarasvathi – Vac is depicted as a goddess of learning (gadya-padya rupena–prasaranmasyamtiti–Sarasvathi- Vagdevata).

Sarasvathi as Vac is adored as the power of truth, free from blemishes; inspiring and illuminating noble thoughts (chetanti sumatim).

In the Taittariya Brahmana, the auspicious (subhage), the rich and plentiful (vajinivati) Vac is identified with Sarasvathi adored as the truth speech ‘Satya-vac’.

Sarasvathi subhage vajinlvati satyavachase bhare matim. idam te havyam ghrtavat sarasvati. Satyavachase prabharema havimsi- TB. II. 5.4.

The Vac-Sarasvathi, the power of speech, is hailed as the mother of Vedas – Veda Mata. She is the abode of all knowledge; the vast flood of truth (Maho arnah); the power of truth (Satya vacs); the guardian of sublime thoughts (dhinam avitri); the inspirer of good acts and thoughts; the mother of sweet but truthful words; the awakener of consciousness (chodayitri sunrtanam, chetanti sumatinam); the purifier (Pavaka); the bountiful blessing with vast riches (vajebhir vajinivati); and the protector of the Yajna (yajnam dadhe).

Vac- Sarasvathi is regarded the very personification of pure (pavaka) thoughts, rich in knowledge or intelligence (Prajna or Dhi) – (vag vai dhiyavasuh)

Pavaka nah sarasvatl yajnam vastu dhiyavasur iti vag vai dhiyavasuh – AB. 1.14.

In the Shata-patha-Brahmana (5. 2.2.13-14) , Vac as Sarasvathi is first taken to be her controlling power, the mind (manas), the abode of all thoughts and knowledge, before they are expressed through speech.

sarasvatyai vāco yanturyantriye dadhāmīti vāgvai sarasvatī tadenaṃ vāca eva yanturyantriye dadhāti – 5. 2.2.13

Again, the Shata-patha-Brahmana (I.4.4.1; 3.2.4.11) mentions the inter-relations among mind (manas), breath (prana) and Speech (Vac). The speech is evolved from mind; and put out through the help of breath. The speech (Vac) is called jlhva Sarasvati i.e., tongue, spoken word. Vac-Sarasvathi is also addressed as Gira, one who is capable to assume a human voice.

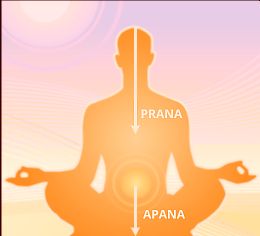

Taittirlya Brahmana refers to Sarasvathi as speech manifested through the help of the vital breath Prana; and, indeed even superior to Prana –

- (vag vai sarasvatl tasmat prananam vag uttamam – Talttirlya Brahmana, 1.3.4.5).

The Tandya Brahmana identifies Sarasvathi with Vac, the speech in the form of sound (sabda or dhvani). Here, Sarasvathi is taken to be sabdatmika Vac, displaying the various form of speech (rupam) as also the object denoted by speech (vairupam): vag vai sarasvati, vag vairupam eva’smai taya yunakti – TB. 16. 5.16.

By the time of the later Vedic texts, the identity of Vac with Sarasvathi becomes very well established. The terms such as ‘Sarasvathi –Vacham’, ‘Vac- Sarasvathi’ etc come into use in the Atharva-Veda. Even the ordinary speech was elevated to the status of Vac

**

Verse 50

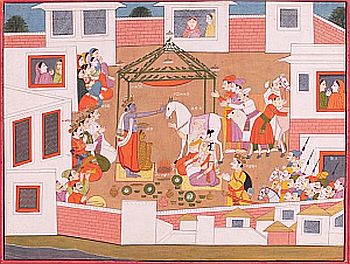

यज्ञेन । यज्ञम् । अयजन्त । देवाः । तानि । धर्माणि । प्रथमानि । आसन् । ते । ह । नाकम् । महिमानः । सचन्त । यत्र । पूर्वे । साध्याः । सन्ति । देवाः ॥ R.V.1.164.50 ॥

yajñena | yajñam | ayajanta | devāḥ | tāni | dharmāṇi | prathamāni | āsan | te | ha | nākam | mahimānaḥ | sacanta | yatra | pūrve | sādhyāḥ | santi | devāḥ

The gods performed a sacrifice for such are their first duties; those mighty ones assemble in heaven, where the divinities who are to be propitiated (by sacred rites) abide

**

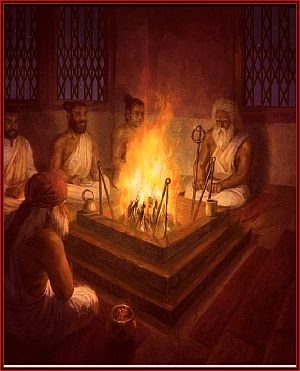

The gods(देवाः) performed(अयजन्त) a sacrifice(यज्ञम्) ; with that they became greater (महिमानः); the first of the Dharmas (तानि– धर्माणि– प्रथमानि). Lo, these greatness’s resorted to the heaven, where the ancient Sadhyas, the gods, are (yatra-pūrve -sādhyāḥ– santi -devāḥ).

Yajnas bring gods and humans together to achieve their common goals and participate in God’s eternal duties as active participants in the sacrifice of creation. The source of Yajna is God himself.

This verse is in praise of the Yajna (यज्ञ). A great Yajna rewards immensely in the heavens (। ते –ह – नाकम् –महिमानः– सचन्त). There is no place for grief there.

*

Commentary by Sāyaṇa: Ṛgveda-bhāṣya

Where the divinities: yatra pūrve sādhyāḥ santi devāḥ: sādhyāḥ = karma-devaḥ, divinities presiding over or giving effect to religious acts, yajñādi sādhanavantaḥ; or, the term may mean those who have obtained the portion, or the condition of gods, by the former worship of Agni, or the sādhyās = ādityas, or the aṅgirasas, or deities presiding over the metres, chando abhimāninaḥ; sādhyās are named among the minor divinities in Amarakośa

Verse 51

समानम् । एतत् । उदकम् । उत् । च । एति । अव । च । अहभिः । भूमिम् । पर्जन्याः । जिन्वन्ति । दिवम् । जिन्वन्ति । अग्नयः ॥ R.V.1.164.51 I

samānam | etat | udakam | ut | ca | eti | ava | ca | aha-bhiḥ | bhūmim | parjanyāḥ| j invanti | divam | jinvanti | agnayaḥ |

This water comes up and down alike day by day. The Parjanyas enliven the earth; the Fires enliven the heaven.

**

The same water goes upward and downward in course of days. The clouds give joy to the earth. The Fire pleases the gods in the Dyu-Loka, the upper worlds.

Dr. Raja explains:

The first half of the verse states that the water goes up and down day by day alike, without any difference. The similarity is in its going up and down. This is explained in the second half. Water here is only some kind of transcendental joy, which migrates from earth, from men to the gods in heaven and from heaven, from the gods, to men on earth. Both the courses are alike. This has close resemblance with the idea found in the Bhagavad-Gita that men must propitiate the gods with sacrifices and that the gods will make men happy in return (ग).

Here also we find the harmony between the ritual mentioned in this verse and the value of knowledge that is the main topic in the poem.

The Deity here is Surya, Parjanya or Agni.

**

The same form (समानम्) of water (एतत् -उदकम्) during certain days (summer अहभिः ) ascend upward to the sky (उच्चैति ). And, goes downward during rainy season (अव-च ). The clouds (पर्जन्याः), whose nature is to please (जिन्वन्ति )the earth (भूमिम्) come down. The Fires (अग्नयः – आहवनीया) please the upper worlds ( दिवम् द्द्युल्लोके जिन्वन्ति ) .

The clouds make the people of the earth happy by helping them to grow rich food crops .

The fires of the Yajnas carry the oblations to the gods in Dyu-Loka ; and make them happy.

Therefore, Parjanya and Agni together take care of the welfare of the people on earth and in the upper regions. These two are interdependent. They also bring together, the humans on earth and gods in the heavens. It is by virtue of their mutual cooperation, the universe progresses safely and happily.

Verse 52

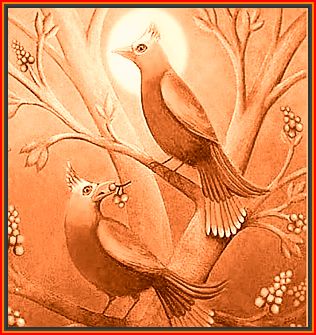

दिव्यम् । सुपर्णम् । वायसम् । बृहन्तम् । अपाम् । गर्भम् । दर्शतम् । ओषधीनाम् । अभीपतः। वृष्टिभिः । तर्पयन्तम् । सरस्वन्तम् । अवसे । जोहवीमि ॥ R.V.1.164.52 II

divyam | su-parṇam | vāyasam | bṛhantam | apām | garbham | darśatam | oṣadhīnām | abhīpataḥ | vṛṣṭi-bhiḥ | tarpayantam | sarasvantam | avase | johavīm i

I invoke for our protection the celestial, well-winged, swift-moving, majestic (Sun); who is the germ of the waters; the displayer of herbs; the cherisher of lakes replenishing the ponds with rain

***

The divine bird, the great bird, the child of waters, of herbs, worthy to be seen, who brings satisfaction with rains in the rainy season, that Sarasvat I invoke again and again for protection.

*

Again and again, I invoke for our protection, the celestial beautiful-winged, swift moving, majestic, graceful, Lord, who is the protector of waters. He is the guardian of herbs, filled with water. It is he who protects and enlivens the world by sending down timely rains.

*

Born in the Dyu-Loka (दिव्यम्), Suparna (सुपर्णम्) of graceful flights, always moving (वायसम्), covered with glory and majesty (बृहन्तम्), produces waters (अपाम्– गर्भम्), of herbs (ओषधीनाम्), reveller (दर्शतम्) , favorable with rains (वृष्टिभिः) ,pleases the worlds (तर्पयन्तम्), full of waters (सरस्वन्तम्), for protection (अवसे ) , I invoke again and again (जोहवीमि)

The Sun may not have waters in him, but, he moves in celestial waters.; and he produces waters. Therefore, he is Sarasvan. This Rik can be interpreted both with reference to the Sun and Sarasvan..

*

The poet Dhirgatamas starts with the mention of “a beloved invoker grown grey, with his two brothers, who is the Lord, and father of seven children” (verse 1).

अस्य । वामस्य । पृषतस्य । होतुः । तस्य॑ । भ्राता । मध्यमः । अस्ति । अशनः | ततीयः । श्रातं । धृतऽपुष्ठः । अस्य॒ । अत्रं । अपर्यम् । विदपतिम् । स्तऽपुत्रम् ॥

Of this beloved invoker, grown grey — of him there is the middle brother, the all-pervading; his third brother is the one who bears ghee on his back. In them I saw the Lord of the People with seven sons.

The poem concludes with a prayer to “the swift-moving divine bird, the majestic bird (Sun), producer of water, which gives life to the herbs; he who brings happiness with timely rains,” for protection, (verse 52).

दिव्यम् । सुऽपर्णम् । वाय॒सम् । बृहन्तम् । अपाम् । ग्मम् । ददतम् । ओष॑धीनाम् । अभीपतः । वृष्टिऽभिः । त॒पै्यन्तम् । सरसन्तम् । अवसे | जोहवीमि ॥ १.१६४.५२

The divine bird, the great bird, the child of waters, of herbs, worthy to be seen, who brings satisfaction with rams in the rainy season, that Sarasvati I invoke again and again for protection.

The first Mantra pictures the symbolism of the three brothers, the three luminaries in the regions; the three forms of fire: Agni, Vayu (Air) and Aditya (Sun).

Yaskacharya explains that there is indeed only One Deity; and, that Deity manifests in the three worlds as Surya (Sun) in heaven (Dyu-Loka); Indra or Vayu (wind) in the middle region (Antariksha); and, fire on the earth (Bhu-Loka). They are the basic foundations of our existence.

Of these three brothers; Aditya (Sun) shining in the sky, the protector (पलितस्य) of the Universe, who is worshipped by all (वामस्य), is the Supreme.

He is accompanied by seven sons (सप्तपुत्रम्), who are not different from himself (his seven rays of seven colours).

The three brothers or the three aspects of Agni (Agni-traya) form the Tripod of Life. They exist and function together.; and, are the basic factors of our existence.

REFERENCES

- History of Pre-Buddhist Indian Philosophy by Dr. Beni-madhab Barua -Motilal Banarsidas-1921

- Tagore Law Lectures 1930 – The History Of Hindu Law by Prof Radha Binod Pal; University of Calcutta – 1958

- Vision in long darkness by Prof. Vasudeva Agrawala

- https://who.rocq.inria.fr/Ramakrishna.Upadrasta/Veda/Asya_Vamiya/AVMS/AVMS_1-100.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r86l_TF9XWc

- https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.226346

- https://istore.chennaimath.org/products/rig-vedic-suktas-asya-vamiya-suktam/1309294000102324374

- pdf (archive.org)

- https://religion.fandom.com/wiki/Dirghatamas

- ऋग्वेदः सूक्तं १.१६४ – विकिस्रोतः (org)

- org/mirrors/rigveda/sanskrit03/RV0310noaccent.html

- ALL IMAGES ARE FROM INTERNET

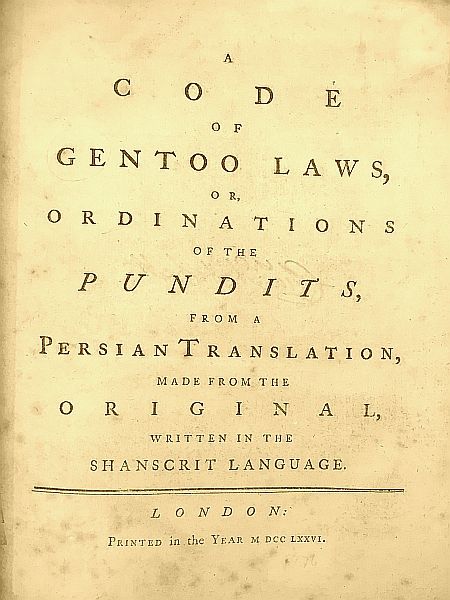

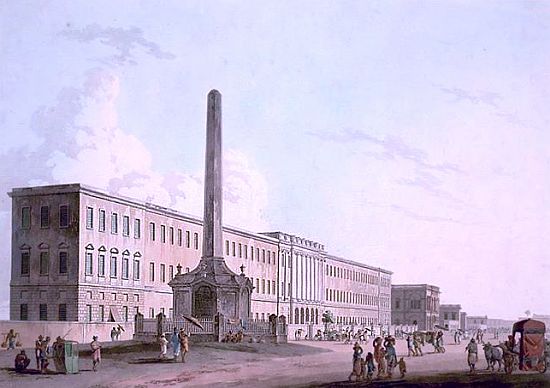

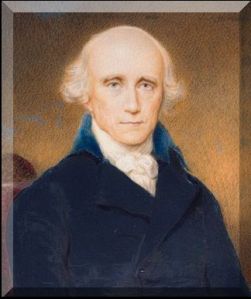

Accordingly, Warren Hastings who was appointed as Governor General of Bengal in April, 1772 was asked to execute the Company’s decision; and, interalia come up with a ‘Judicial Plan’. His immediate object thereafter was to devise an arrangement to dispense law/justice to the Indian litigants in ways that are as close as possible to their own customs, in matters of person and property; and, particularly, on matters considered as religious. But, the dispensation of justice had to be according to the British norms and by British Judges; and it was made explicitly clear that employing the Indian scholars or pundits as judges was totally out of question.

Accordingly, Warren Hastings who was appointed as Governor General of Bengal in April, 1772 was asked to execute the Company’s decision; and, interalia come up with a ‘Judicial Plan’. His immediate object thereafter was to devise an arrangement to dispense law/justice to the Indian litigants in ways that are as close as possible to their own customs, in matters of person and property; and, particularly, on matters considered as religious. But, the dispensation of justice had to be according to the British norms and by British Judges; and it was made explicitly clear that employing the Indian scholars or pundits as judges was totally out of question.