Agama and Temple architecture

The Agama literature includes the Shilpa- Shastra, which covers architecture and iconography. The aspects of temple construction are dealt in Devalaya Vastu; and, Prathima deals with the iconography. Sometimes, the term Shipa is also used to denote the art of sculpting; but , here Shipa refers to the practice of the technique; while Shastra refers to its principles.

The worship dealt with in the Agama texts necessarily involves worship-worthy images. The rituals and sequences elaborated in the Agama texts are in the context of such worship-worthy image, which necessarily has to be contained in a shrine. The basic idea is that a temple must be built for the icon,and not an icon got ready for the temples; for, a temple is only an outgrowth of the icon; an expanded image of the icon. And an icon is meaningful only in the context of a shrine that is worthy to house it. That is how the Agama literature makes its presence felt in the Shilpa-Sastra, Architecture. The icon and its form; the temple and its structure; and, the rituals and their details, thus get interrelated . Further, the Indian temples should be viewed in the general framework of temple culture; which include not only religious and philosophical aspects but also the social, aesthetic and economic aspects .

Elaborate rules are laid out in the Agamas for Shilpa ; describing the quality requirements of the places where temples are to be built; the kind of images to be installed; the materials from which they are to be made; their dimensions, proportions; air circulation; lighting in the temple complex etc. The Manasara and Shilpasara are some of the works dealing with these rules. The rituals followed in worship services each day at the temple also follow rules laid out in the Agamas.

While describing the essential requirements for a place of pilgrimage , Shilpa Shatras of the Agamas elaborate on the requirements of the temple site; building materials; dimensions, directions and orientations of the temple structures; the image and its specifications. The principal elements that are involved are the Sthala (temple site); Teertha (Temple tank); and, Murthi (the idol). A temple could also be associated with a tree, called the Sthala Vriksham.

The Gupta Age marked the advent of a vibrant period of building and sculpting activities. The texts of this period such as the Arthashastra of Kautilya and Matsya Purana included chapters on the architecture of the way of summary. By the end of the period, the art and craft flourished; and branched into different schools of architectural thought; but, all were based on common underlying principles. These principles are now part of Vastushastra, the science of architectural design and construction. . It is explained that the term Vastu is derived from Vasu meaning the Earth principle (prithvi). This planet is Vastu; and, whatever that is created is Vastu; and , all objects of earth and those surrounding it are Vastu.

During the medieval period, vast body of Sanskrit references, independent architectural manuals were written, without reservation or uniformity; and were scattered across the country. Apparently, later, some attempts were made to classify and evaluate their contents in a systematic way.

Of the many such attempts that tried to bring about order and coherence in the various theories and principles of temple construction, the most well known compilations are Manasara and Mayamata. They are the standard texts on Vastu Shastra; and , they codify the theoretical aspects of all types of constructions; but specifically of temple construction. These texts deal with the whole range of architectural science including topics such as soil testing techniques, orientation, measures and proportion, divination, astrology and ceremonies associated with the construction of buildings.

Manasara is a comprehensive treaty on architecture and iconography. It represents the universality of Vastu tradition; and includes the iconography of Jain and Buddhist images. The work is treated as a source book and consulted by all.

The Mayamata too occupies an important position. It is a general treatise on Vastu shastra; and, is a text of Southern India. It is regarded a part of Shaiva literature ; and, it might belong to the Chola period when temple architecture reached its peak. It is the best known work on Vastu. The work is coherent and well structured. It defines Vastu as the arrangement of space, anywhere, wherein the immortals and mortals live.

These subjects are intertwined with Astrology. The Vastu Texts believe that Vigraha (icon or image of the deity) is closely related to Graha (planets).The term Graha literally means that which attracts or receives; and, Vigraha is that which transmits. It is believed that the idols receive power from the planets; and transmit the power so received. It not merely is a symbolism; but, it is also the one that provides logic for placement of various deities in their respective quarters and directions within the temple complex.

The texts that are collectively called Vastu Shastra have their origin in the Sutras, Puranas and Agamas; besides the Tantric literature and the Brhat-Samhita of Varahamihira (52 vāstuvidyā).

The Vastu texts classify the temple into three basic structures: Nagara, Dravida and Vesara. They employ, respectively, the square, octagon and the apse or circle in their plan. These three styles do not pertain strictly to three different regions ; but, are three schools of temple architecture that might be employed commonly. The Vesara, for instance, which prevailed mostly in western Deccan and south Karnataka, was a derivation from the apsidal chapels of the early Buddhist period which the Brahmanical faith adopted and vastly improved.

These three schools have given rise to about forty-five basic varieties of temples types. They too have their many variations ; and, thus the styles of temple architecture in India are quite diverse and virtually unlimited .

Among the many traditions inherited (parampara) in India, the tradition of Vishwakarma is unique. The mode of transmission of knowledge of this community is both oral and practical; and, its theories envisage a holistic universe of thought and understanding. The rigor and discipline required to create objects that defy time and persist beyond generations of artists, has imbued this tradition with tremendous sense of purpose, and zeal to maintain the purity and sensitivity of its traditions; and, to carry it forward . This has enabled them to protect the purity of the art and skills without falling prey to the market and its dynamics.

It is virtually impossible to state when the custom of building stylized temples took hold in our country.

The Rig Veda is centered on home and worship at home. There is not much emphasis on temple worship. The term employed in Grihya-sutras (Ashvalayana – 1.12.1; and Parashara – 3.11.10 ) to denote a temple was Chaithya , which literally means, piling up ; as piling up of the fire alter , agni-chiti from bricks (as in agni-chayana) where a Yajna was conducted – (Caitya yajñe prāk sviṣṭakṛtaś caityāya balim haret ; and ,caityavṛkṣaś citir yūpaś caṇḍālaḥ somavikray).

This perhaps suggests that Chaitya implied piling up bricks to form a shrine. This is consistent with the view that the earliest temples were relatively simple piled brick structures.

The use of the term Chaithya to denote a place of worship appears to have been in vogue for quite a long period after the Vedic age . In Mahabharata, the Rishi Lomaharsha mentions to Yudhistira that the tirtha on the Archika hill is a place where there are chaityas for the 33 gods (MBh 3.125).

ārcīka-parvataś caiva nivāso vai manīṣiṇām /sadāphalaḥ sadāsroto marutāṃ sthānam uttamam / caityāś caite bahuśatās tridaśānāṃ yudhiṣṭhira (MB. 03,125.013)

He also advises Pandavas to visit the Chaityas on the banks of the Narmada (MBh 3.121) –vaiḍūryaparvataṃ dṛṣṭvā narmadām avatīrya ca (MB.03.121.018)

[ Tirtha refers to any holy place, such as the river, the sea, or a site where a famous Yajna was conducted. It appears, in the ancient period, such Tirthas were, indeed, the pilgrim places; that is, before the emergence of temples per se. Even today, the rivers at Varanasi and Haridwar; the confluence of rivers at Prayag; the sea at Rameshwaram; the Nara-Narayana peaks at Badrinath; and the Mount Kailas are the primary worship centres to where the pilgrims depart devotedly. The temples in these places are either incidental or came up at a later time. ]

Mahabharata often refers to Chaithyas as being close to Yupas (chaithyupa nikata bhumi); Yupa being the spot where a major Yajna was performed. It is possible that small shrines were erected on the Yupa site to commemorate the Yajna.

Ramayana too mentions that Meghanada, the son of Ravana, tried to perform a Yajna in a temple located in the Nikhumba grove.

Zarathustra demands from Ahur Mazda “Tell me, can I uproot the idol from this assembly that set up by the angras and the karpanas?”. At another time, the Emperor Xerxes, a follower of Zarathustra declares “I destroyed this temple of daevas”.

The Buddhist and Jain texts mention of a certain Chaithya of Devi Shasti, consort of Kumara, at Vishala. Jain texts, in particular, mention the Chaithyas of Skanda in Savasthi; of Shulapani (Rudra) and of Yakshini Purnabhadra.

Therefore, by about six hundred BC, the Chiathyas were quite common. They were perhaps small-sized constructions (usually of brick), surrounded by groves of ashvattha or audumbara trees.

The Maurya period described in the Artha-shastra, had Chaithyas for a number of Devis and Devas, such as Indra, kumara, Rudra, and Aparajita etc. A description of the Chaitya of goddess Kaumari suggests that it had multiple Avaranas, one enclosing the other ; and, the outer Avarana having a circular arch. By the time of the Mauryas, the Chaithyas appeared to have steadily gained importance; and , become an integral aspect of city life. However, there is nothing to suggest that they were large structures like the classical Hindu temples that were to follow later.

The Buddhism, in its initial stages, rejected the of the Vedic practices; however, in due course, it came to adopt some features of the old religion. For instance; the ‘piling’ (Chayana) of the Vedic fire-altar was transformed into a Buddhist Chaitya. It is likely that the Buddhist Chaitya was initially meant to be a funeral pyre. But, in the later periods, it became a prime symbol of the Buddhist architecture. And, similarly, much later, Homa (offering oblation into the fire) became an accepted practice in the Mahayana Buddhism.

By about first century BC , the Buddhist places of congregation either as caves carved into rocks or as free standing structures, came to be known as Chaithya_grihas. These were patterned after the shrines of Vishnu, with the form of the fire altar being placed on the raised platform in the apse of the Chaithya hall. The term Chaithya later came to increasingly associated with the Buddhist Stupas or places of worship.

[ For more on the architecture of the Buddhist Stupas , please do read Stūpa to Maṇḍala: Tracing a Buddhist Architectural Development.. by Prof. Swati Chemburkar , Jnana-pravaha , Mumbai.]

It was perhaps during the period of the Imperial Guptas that a Hindu temple came to be regularly addressed as Devalaya, the abode of Gods. The oldest of the surviving structural shrines date back to the third or even fourth century A.D .They are made of bricks.

Some of the them might perhaps have been temporary structures, erected on occasions of community-worship. The canonical concept of pavilion (Mantapa) suggests that they might have been pavilions to accommodate those who gathered to participate in the worship ritual. It is only later that such structures tended to be permanent and bigger.

The earliest temples in North and Central India which have survived the vagaries of time belong to the Gupta period, 320-650 A. D. ; such as the temples at Sanchi, Tigawa (near Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh), Bhumara (in Madhya Pradesh), Nachna (Rajasthan) and Deogarh (near Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh). They consist of a square, dark sanctum with a small, pillared porch in front; both covered with flat roofs.

The brick temple at Bhitargaon ; and the Vishnu temple at Deogarh, built entirely of stone, both,have a square sanctum; but, instead of a flat roof there is a pyramidal superstructure (sikhara).

The rock-cut temple and monastery tradition also continued in this period, notably in Western India, where the excavations – especially at Ajanta acquired extreme richness and magnificence.

The temple groups at Aihole and Pattadakal in North Karnataka date back to about 5th century, and seem to represent early attempts to experiment with several styles; and, to evolve an acceptable and a standard regional format. Here, temples of the Northern and the Southern styles are found next to each other. Besides, Badami, the capital of the Early Chalukyas, who ruled much of Karnataka in the 6th to 8th centuries, is known for its ancient cave temples carved out of the sandstone hills above it.

The school of architecture in South India seems to have evolved from the earliest Buddhist shrines which were both rock-cut and structural. The later rock-cut temples which belong to 5th or 6th century A.D. were mostly Brahmanical or Jain, patronized by three great ruling dynasties of the South, namely the Pallavas of Kanchi in the East; the Calukyas of Badami; and the Rastrakutas of Malkhed – all of whom made great contributions to the development of South Indian temple architecture. The Kailasanatha temple at Ellora also belongs to this period.

The next thousand years (from 600 to 1600 A.D.) witnessed a phenomenal growth in temple architecture. The first in the series of Southern or Dravidian architecture was initiated by the Pallavas (600-900A.D.) The rock-cut temples (of the Ratha type) and the structural temples like those at the shore temple at Mahabalipuram; and the Kailasanatha and Vaikuntha Perumal temples in Kanchipuram (700-800 A.D.) are the best representations of the Pallava style.

The Kailasanatha (dating a little later than the Shore Temple), with its stately superstructure and subsidiary shrines attached to the walls is a great contraction. Another splendid temple at Kanchipuram is the Vaikuntha Perumal (mid-8th century), which has an interesting arrangement of three sanctums, one above the other, encased within the body of the superstructure.

***

Please do read the scholarly paper “Regionalism: Art and Architecture of the Decaan and South India” by Dr. Niharika K Sankrityayan

Politically by the eighth century CE the Deccan and southern India were experiencing changes in political environment. From the middle of the sixth century to the thirteenth century, the Deccan region of peninsular India came under the sway of a line of rulers.

An important dynasty was the Chalukyas of Badami ruling from their capital at Badami or Vatapi . The Early Chalukyas achieved political unification of much of the Deccan for almost 200 years, even though during this period portions of their territories were temporarily lost to the Pallavas from the Tamil country in southern India.

Just after 750 CE the Chalukyas of Badami succumbed to the Rashtrakuta invasion from Maharashtra in the northern Deccan. From 757 CE for about two centuries, the Rashtrakutas ruled over the Deccan.

In 973 CE, the Rashtrakutas were ousted by Taila II, a scion of the Chalukya family, who established his capital at Kalyani/Kalyana.

The decedents of Taila ruled from there until 1161 CE, when the region was temporarily occupied by the Kalachuris with their capital at Annigeri and was afterwards shifted to Kalyani.

The Chalukyas of Kalyani regained power and ruled until 1189 CE.

Due to the declining strength, the southern part of their territory was occupied by the Hoysalas and the northern by the Yadavas of Devagiri.

The Yadavas ruled from 1187-1310 CE.

The Kakatiyas who were vassals of the Chalukyas of Kalyani became independent after the defeat of the Chalukyas by the Kalachuris.

The Kakatiyas rose to power and ruled over a large part of the Deccan for nearly three centuries.

The Eastern Chalukyas established themselves in Vengi by the second half of the eighth century and ruled till late tenth century, when they defeated by the Cholas .

The Pallavas of Kanchi continued to rule till the ninth century coming constantly in conflict with the Chalukyas, Pandyas and Rashtrakutas, their power slowly dwindling replaced by the Cholas.

The Cholas came to power at Tanjore under Vijayalaya, who defeated the Muttaraiyar chiefs. In the beginning of their rule the Cholas accepted Pallavas as their overlords, but by the end of the ninth century, beginning of tenth the Cholas under the leadership of Aditya I(871-907 CE) had become one of the strongest dynasty ruling from south India.

By mid-twelfth century under the rule of the later Chola kings the empire began to dwindle loosing territory to the western Chalukyas and the emerging Hoysalas, who ruled Karnataka from the tenth to the fourteenth century.

Each of the political dynasties that ruled south India and Deccan created some of the exquisite examples of art, both in terms of temple architecture and sculpture.

The Kailāsanātha temple of Kanchipuram is one of the masterpieces of Pallava architects. It is attributed to the time of Rājasiṃha Pallava (700-728 CE), also known as Nṛsiṃhavarmaṉ II. His Queen Rangapataka is said to have associated herself actively in the construction of the Kailāsanātha temple.

The noted scholar Gerd J.R. Mevissen writes: Three large temple complexes in South India, all of them royal foundations and innovative in their layout, have one feature in common: They are the only temples in which occur multiple images of Tripurāntakamūrti, the cosmic warrior form of Śhiva.

The three temples are:

the Rājasiṃheśvara (now known as Kailāsanātha), built by the Pallavaruler Narasiṃhavarman II Rājasiṃha at his capital Kanchipuram in the early eighth century;

the Rājarājeśvara (now known as Bṛhadīśvara), constructed by Rājarāja Chola I at his capital Tanjavur in the early 11th century; and,

the Rājarājeśvara (now known as Airāvateśvara), erected by Rājarāja Chola II at his temporary capital Darasuram in the mid-12th century

As regards Kanchipuram: In the early eighth century, the Rājasiṃheśvara (Kailāsanātha) temple at Kanchipuram was probably the largest structural Hindu temple complex thus far built anywhere in India. The central temple is located in the western part of a large rectangular prākāra (walled enclosure), which is encircled by more than 50 Devakulikā-s (subsidiary shrines). The surface of these sub shrines as well as the spaces between them are carved with hundreds of sculptures, all related to Shaiva iconography, thus assembling the largest pantheon of Śhivamūrti -s perhaps ever created in India. Also the temple’s main body (Vimāna) with originally at least seven Parivara shrines built against its outer walls is carved all over with different forms of Shiva.

[Rājasiṃha is also credited with the construction of Rājasiṃheśvara or the Shore temple at Māmallapauram; Talagirīśvara at Paṉamalai; and, other temples for Shiva in Kāñci such as the Mukteśvara and Matangesvara.]

The architecture and iconography of the Kailāsanātha of Kāñci has been examined in recent times by many scholars from different points of view. some say it was a base of the Yogini cult, coexisting with Shivaism; having detailed the iconographic designs of the male or female syncretistic forms, such as: Somāskanda, Ardhanārīśvara, Harihara and so on. However, this is a much-debated subject; and the presence of the cult of Yoginis at Kailasanatha in inconclusive.

There is also a view that the temple Iconography, though the ideology is rooted in the Linga and Somāskanda, follows the Trimurthi concept, with the presence of Shiva in the crest; and Brahma and Vishnu in secondary and tertiary chambers.

About twenty- five images of Devī are in the Kailāsanātha of Kāñci. The location of these images is: Four on the Mukha-maṇtapa sections; four in southern Deva-kulikās; three on southern Deva-koṣṭhas; and, nine on the northern Deva-kulikās and so on.

The Kailasanatha temple is unique in plan; unlike in other Pallava temples.

Oblong and east-facing, the first to be built within the four walls is called Rājasiṃheśvara that occupies the western part of the complex.

The eastern half was fitted with another temple for Śiva, called Mahendra-varmeśvara added by his short-lived son, Mahendravarmaṉ III.

Both the temples in the Garbha-gṛha accommodate the Śiva- Linga superimposed on the back wall by the anthropomorphic Somāskanda.

The entire temple is fenced by a wall, which is fitted with miniature chapels, called devakulikā s. This is a distinctive pattern that we do not come across in other temples of South India.

The Kailāsanātha during the early eighth century was erected with sandstone, plastered and painted. What we find in the present temple is that the original plaster and paintings have fallen or disappeared in most cases. The fallen plaster seems to have been re-plastered sometime in the nineteenth or early twentieth century. Several Pallava temples have undergone renovation in Kāñci, nearby Kurram, and the Pallava feudatory Muttaraiyar cave temple at Malaiyaṭippaṭṭi in the Pudukkottai region, especially for Ranganatha (and Pandya caves at Kuṉṉakkuṭi. Therefore, Dr. R.K.K. Rajarajan , in his research paper The Iconography of the Kailāsanātha Temple , advises that when a scholar studies the Pallava iconographical features in the temples of Kāñci, he has to be very careful in differentiating the original Pallava with later re-plastered images.

***

Tirupparankunram

Located about 10 kilometres to the southwest of Madurai is the suburban town of Thirupparankundram (also spelled Tiruparankundram) with a massive monolithic rock. It is called Skandamalai locally. It consists of several layers of construction; the earliest is dated to the 8th-century early Pandya period, and the last to the 13th-century.

The Tirupparankunram south cave consists basically of three cellars; two on the lateral; and, the main, dedicated to Mahisāsura-mardinī, on the back wall. The lateral shrines are dedicated to Linga-Somāskanda (east-facing) and VisnuVaikunthamūrti (west facing).

In the Trikūta pattern, having a triangle structure at the summits, which are occupied by the sculptures of Trimūrtis (Brahma, Vishnu and Maheshvara). But, in the later times (by about the 8th Century), in the North group of the caves at Thirupparankundram, the Brahma figures were etched out; and, were replaced by the figures of the Devi.

According to Dr. Rajarajan, during the reign of Varaguna Pāndya (AD 767-815) some alterations and additions were made to the original rock-cut temple in the Kali year 3,874 (AD 773-4), to create cells for the images of the Devi. He also suggests that within the Pyramidal set-up of the North Cave of the Tirupparankunram temples, the images of the Devi were accommodated as per the Sri-Chakra structure (isometric).

***

The Talapurisvara temple at Panamalai is another excellent example. The Pallavas laid the foundations of the Dravidian school which blossomed during the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Vijayanagar kings and the Nayaks.

Most important of a large number of unpretentious and beautiful shrines that dot the Tamil countryside are the Vijayalaya Colisvara temple at Narttamalai (mid-9th century), with its circular sanctum, spherical cupola, and massive, plain walls; the twin shrines called Agastyisvara and Colisvara, at Kilaiyur (late 9th century); and the splendid group of two temples (originally three) known as the Muvarkovil, at Kodumbalur (c. 875).

The Vijayalaya Colisvara temple, with its first and second thala (base) of the Vimanam square in shape, the third in circular (vasara) and the griva and Shikhira also in circular shape; is a forerunner of the magnificent temple at Gangai-konda-chola-puram built by Rajendra Chola. Its Vimana is a fine mixture of Nagara and Vesara styles.

These simple beginnings led rapidly (in about a century) to grandeur and style. The temples, now built of stone, were huge, more complex and ornate with sculptures.

Dravidian architecture reached its glory during the Chola period (900-1200 A.D.). Among the most magnificent of the Chola temples is the Brhadishvara temple at Tanjore with its 66 meter high Vimana, the tallest of its kind. The later Pandyans who succeeded the Cholas improved on the Cholas by introducing elaborate ornamentation and huge sculptural images, many-pillared halls, new annexes to the shrine and towers (gopurams) on the gateways. The mighty temple complexes of Madurai and Srirangam set a pattern for the Vijayanagar builders (1350-1565 A.D.) who followed the Dravidian tradition. The Pampapati Virupaksha and Vitthala temples in Hampi are standing examples of this period. The Nayaks of Madurai who succeeded the Vijayanagar kings (1600-1750 A.D.) made the Dravidian temple complex even more elaborate by making the Gopurams very tall and ornate and adding pillared corridors within the temple long compound.

The Hoysalas (1100-1300A.D.), who ruled the Kannada country, improved on the Chalukyan style by building extremely ornate, finely chiseled, intricately sculptured temples mounted on star shaped pedestals.

The Hoysala temples are noted for the delicately carved sculptures in the walls, depressed ceilings, lathe-turned pillars in a variety of fanciful shapes ; and fully sculptured vimanas. The exterior is almost totally covered with sculpture, the walls decorated with several bands of ornamental motifs and a narrative relief.

Among the more famous of these temples, which are classified under the Vesara style, arethe twin Hoysalesvara temple at Halebid, the Chenna Kesava temple at Belur (1117), the Amrtesvara temple at Amritpur (1196), and the Kesava (trikuta) temple at Somnathpur (1268).

In the North, the major developments in Hindu temple architecture were in Orissa (750-1250 A.D.) and Central India (950-1050 A.D.) as also Rajasthan (10th and 11th Century A.D.) and Gujarat (11th-13thCentury A.D.).

Saas-bahu temple, Udaipur

Rani ki vav , Gujarat

The temples of Lingaraja (Bhubaneswar), Jagannatha (Puri) and Surya (Konarak) represent the Kalinga-Nagara style. The greatest center of this school is the ancient city of Bhubaneswar, which has almost 100 examples of the style, both great and small, ranging from the 7th to the 13th century. The most magnificent structure, however, is the great Lingaraja temple (11th century), an achievement of Kalinga architecture in full flower.

The most famous of all Kalinga temples, however, is the colossal building at Konarak, built by the Chandellas, dedicated to Surya, the sun god. The temple and its accompanying hall are conceived in the form of a great chariot drawn by horses.

The Surya temple at Modhera (Gujarat) and other temple at Mt. Abu built by the Solankis have their own distinct features in Central Indian architecture. Bengal with its temples built in bricks and terracotta tiles and Kerala with its temples having unique roof structure suited to the heavy rainfall of the region developed their own special styles.

The Sri Ramanathaswami temple (12th century) has the longest corridor among all temples in India; and, is elaborately decorated

Hindu temples were built outside India too. The earliest of such temples are found in Java; for instance the Shiva temples at Dieng and Idong Songo built by the kings of Sailendra dynasty ( 6th -9thcentury). The group of temples of Lara Jonggrang at Paranbanam (9th to 10th century) is a magnificent example of Hindu temple architecture.

[ Please do read “Hindu temple of India, Cambodia and Indonesia” by Dr. Uday Dokras ]

Candi Prambanan in Java- Image created by Peter Jordaan

Other major temples are: the temple complex at Panataran (Java) built by the kings of Majapahit dynasty (14th century); the rock-cut temple facades at Tampaksiring of Bali (11th century); the Mother temple at Beshakh of Bali (14th century); the Chen La temples at Sambor Prei Kuk in Cambodia (7th – 6th century); the temples of Banteay Srei at Angkor (10th century) and the celebrated Angkor Vat temple complex (12th century) built by Surya Varman II.

Sources:

Pictures from Internet

Devalaya Vastu By Prof. SKR Rao

Encyclopaedia Britannica

http://www.britannica.com/dday/print?articleId=109585&fullArticle=true&tocId=65333

To follow :

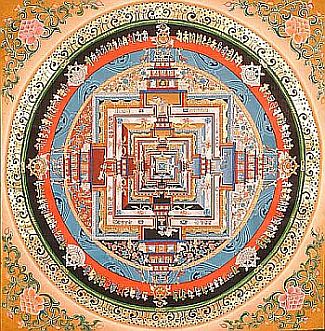

Vastu Purusha Mandala

Temple Layout

Parts of the Temple

Iconography

Norms and Measurements