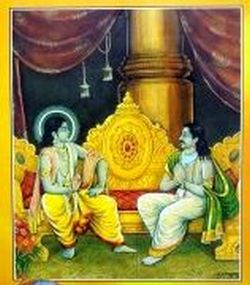

Anugita (that which follows the Gita), appears in the Ashvamedha Parva of the Mahabharata, as a sequel to the Bhagavad-Gita. It again is a conversation between Krishna and Arjuna. It takes place at the Pandavas’ palace in Indraprastha, as Krishna was on his way back to Dwaraka after helping to restore the kingdom of Hastinapura to the Pandavas following their victory in the war at Kurukshetra.

kṛṣṇena sahitaḥ pārthaḥ svarājyaṃ prāpya kevalam । tasyāṃ sabhāyāṃ ramyāyāṃ vijahāra mudā yutaḥ ॥ 2॥

Arjuna requests Krishna to recapitulate the teachings he imparted on the battlefield at Kurukshetra as most of that had “gone out of his mind “.

yattu tadbhavatā proktaṃ tadā keśava sauhṛdāt । tatsarvaṃ puruṣavyāghra naṣṭaṃ me naṣṭa cetasaḥ ॥ 6॥

Krishna obviously is not pleased with his disciple, nevertheless agrees to impart the instructions. Krishna mentions, “It is now virtually impossible for me to repeat my earlier instructions verbatim”. In lieu of that, he says, he would try to teach similar instructions through certain ancient stories (Purathana Ithihaasa). Krishna’s rendering, which then followed is “Anugita” (anu = after or later).

paraṃ hi brahma kathitaṃ yogayuktena tanmayā । itihāsaṃ tu vakṣyāmi tasminnarthe purātanam ॥ 12॥

**

Anugita is spread over 34 chapters (from 16th to 50th) of the Ashvamedha Parva. It comprises three sections. The subject matter of the text pertains to transmigration of souls, means of attaining liberation, and discussions about gunas, ashramas (stages of life), Tapas (penance), Yoga and Dharma.

- The first section of the text is a discussion between a Siddha (the one who has attained) and a descendent of Kashyapa.

- The second is a discussion between a Brahmana and his wife; and

- the last one is a discussion between a Guru and his disciple.

All the three discussions are narrated by Krishna.

Anugita is not a well-known work despite its considerable antiquity and its somewhat different presentation of the later Upanishad thought. Though Sankara quoted from it a couple of times, its general appeal is rather limited and the text is not often discussed.

It looks certain that Anugita is a later insertion into Mahabharata. Rishi Veda Vyasa was therefore not its author. Its authorship is unknown. The question whether its three sections are the work of one author or whether the writings of different authors were put together to form the text, is also a matter of debate.

The renowned scholar Kashinath T Telang, who first translated the text into English during 1880, after much discussion concluded, “Upon the whole, therefore, we here conclude, though not without doubt, that the whole of the Anugîtâ is the work of one author.”

The age of the text is uncertain. All scholars agree that Anugita is an ancient text, but argue about its age. Kashinath T Telang after a lengthy and an interesting analysis plots the age of Anugita as under:

*Anugita belongs to a period far removed from the later Upanishads.

*Mahabharata and Bhagavad-Gita preceded Anugita by several centuries.

*Anugita just preceded Jainism, Buddhism and Yoga philosophy.

*Anugita is much older than Apastamba’s Dharma Sutras.

*Bhagavad-Gita, Anugita and Dharma Sutras of Apasthamba belong to different stages of ancient Indian society. The stage to which Bhagavad-Gita belonged is the earliest and the stage to which Apasthamba belonged to was the latest.

*Anugita is several centuries earlier to Puranas. The theology of Anugita is closer to that of the Vedas, as Mitra, Varuna, Agni and Prajapathi are the major deities in Anugita.

*It would therefore seem that Anugita belongs to a period prior to the sixth century B.C.

(http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/sbe08/sbe0827.htm)

The language and style of Anugita are not quite smooth, as compared to Bhagavad-Gita. Anugita is a rather difficult text. Lucidity and clarity are not among its strengths. It is riddled with ambiguity, at several places. Its commentaries by Arguna Mishra and Nilakantha too suffer from similar defects. Added to that, its translations into English by KT Telang and KM Ganguli are also not easy to read either, peppered with numerous footnotes and explanations. It is not surprising the text is not very popular among the general readers.

Nonetheless, Anugita is a valuable ancient text, which provides a unique perspective to Indian philosophical themes following the Upanishad style of exposition. It deals certain subjects more comprehensively than Bhagavad Gita does. It encourages human enterprise and endeavor; and asks one to think for oneself, analyze and find ones way to liberation rather than depend on external aid or look for divine intervention. Certain of its passages are beautifully written. I wish more people pay attention to this ancient text. It deserves serious study .

The first section of the text is a discussion between Kashyapa a learned Brahmana and a Siddha that is a Spiritual Master. It commences with Kashyapa requesting for instructions about rebirth and the way to attain liberation from cycle of births. The Siddha at the outset points out that the sacrifices at best lead to the short-lived pleasures of celestial abode (swarga).They are not the right means for escape from the cycle of births.

Kashyapa then desires to know how the soul departs from the body; and then how the body is produed.The Master in reply comments on the irregular living habits of the humans. Thanks to merits inherited from previous births, a person is blessed with health, fortune and fame; but soon he throws away those benefits by his irregular living.

“He eats sometime to excess, sometimes nothing. He eats highly spiced meal and sleeps all daylong. He catches lethal diseases. An unhealthy heat generated in his body, kindled by irregular heavy breathing, hinders the body functions and blocks the vital forces (winds).As the compact association of the five elements is broken up, the life, tormented, leaves the body.”

rasāti yuktamannaṃ vā divā svapnaṃ niṣevate । apakvānāgate kāle svayaṃ doṣānprakopayan ॥ 12॥ sva doṣa kopanādrogaṃ labhate maraṇāntikam ।

atha codbandhanādīni parītāni vyavasyati ॥ 13॥

The Siddha continues his lesson on the future of the soul which either goes up to heaven or goes down to hell, until it becomes an embryo: “Just as melting iron takes the shape of the mould, the soul slips into the embryo. Just as a lit lamp lights a room, the conscience lights the body “.

yathā hi lohaniṣyando niṣikto bimbavigraham । upaiti tadvajjānīhi garbhe jīva praveśanam ॥ 8॥ lohapiṇḍaṃ yathā vahniḥ praviśatyabhitāpayan । tathā tvamapi jānīhi garbhe jīvopa pādanam ॥ 9॥ yathā ca dīpaḥ śaraṇaṃ dīpyamānaḥ prakāśayet । evameva śarīrāṇi prakāśayati cetanā ॥ 10॥ yadyacca kurute karma śubhaṃ vā yadi vāśubham । pūrva deha kṛtaṃ sarvam avaśyam upabhujyate ॥ 11॥

One has to break that chain by cultivating a discipline of renunciation from attachment to senses, to objects, to opposites and to excesses. One should look upon this universe as transient, like an Aswath tree, always full of birth, death, and old age. Restraining the senses, one should fix the mind, as a lamp, on the Spiritual Principle (mahat).

“The jiva sees the self come out from the body; and abandoning his body, he perceives the Self, — holding it to be the immaculate Brahman,—with, as it were, a mental smile. Then depending upon it thus, he attains final emancipation in me. “

sukhaduḥkhe sadā samyaganitye yaḥ prapaśyati । kāyaṃ cāmedhya saṅghātaṃ vināśaṃ karma saṃhitam ॥ 30॥ yacca kiṃ citsukhaṃ tacca sarvaṃ duḥkhamiti smaran ।saṃsāra sāgaraṃ ghoraṃ tariṣyati sudustaram ॥ 31॥jātī maraṇarogaiśca samāviṣṭaḥ pradhānavit । cetanāvatsu caitanyaṃ samaṃ bhūteṣu paśyati ॥ 32॥nirvidyate tataḥ kṛtsnaṃ mārgamāṇaḥ paraṃ padam । tasyopadeśaṃ vakṣyāmi yāthātathyena sattama ॥ 33॥

**

The second section is a discussion between a learned Brahmana and his wife. She is rather anxious about her afterlife. “What sort of Salvation awaits me?” The husband reminds her of the Absolute in every being. He tells her,

“The temple is inside me. The temple cannot be smelled by the nose, nor tasted by the tongue, nor felt by the touch. Its access is through the mind.”

It is from which the whole expanse of universe proceeds and on which it rests. It is from here the five breaths (vayus) Prana, Apaana, Samana, Vyana and Udana proceed and into it, they enter.

vairāgya buddhiḥ satataṃ tāpadoṣavyapekṣakaḥ । ātmabandhavinirmokṣaṃ sa karotyacirā diva ॥ 9॥agandha rasamasparśamaśabdamaparigraham । arūpa mana abhijñeyaṃ dṛṣṭvātmānaṃ vimucyate ॥ 10॥ pañca bhūtaguṇairhīnamamūrti mada lepakam । aguṇaṃ guṇa bhoktāraṃ yaḥ paśyati sa mucyate ॥ 11॥

In the midst of those life-winds, which move about in the body and swallow up one another, the Vaishvanara fire blazes seven-fold. The nose, tongue, ears, eyes, skin, mind and the understanding are the seven tongues of the Vaishvanara. The objects of smell, taste, sound, color and touch as also that which is to be thought and that which is to be understood are the seven kinds of fuel (offerings). The sensations of smell, sound, sight etc are the seven officiating priests. These seven pour seven offerings into seven fires (meaning that he, who smells, tastes, hears and so on, and pours into his organs of perception the perceived information.). By restraining the senses and the mind and by pouring (offering) the objects of those senses and the mind as libations into the sacred fire of the Soul within the body, one performs the Yajna. The commentators clarify, here, that it is the senses that enjoy; and not the Soul.

Brahmana then explains the principle of Chaturhotra, the four-sacrifices.The nose, and the tongue, and the eye, and the skin, and the ear; and the mind and the understanding, these seven, acquire the knowledge about the qualities of the objects. Smell, taste, color, sound, and touch as the fifth, the object of the mental operation and the understanding, these seven, lead to action. He, who smells, eats, and sees, and so on is the agent. It is from these seven the Self is to be emancipated. The instrument, the action, the agent, and emancipation are the four Hotris by whom this universe is enveloped. (The commentators remark the intention of the author has not come out here clearly).

The ten organs (The ear, the skin, the two eyes, the tongue, the nose, the two feet, the two hands, speech, the genital organ, and the anus) are the makers of the offering. They are the ten priests at the Yajna. The Sound, touch, color, and taste, smell, words, action, motion, and the discharge of semen, urine, and excrement are the ten oblations (offerings). Thus, the ten organs are the offers; the ten objects of senses are the offerings. They are offered into ten fires. The mind is the ladle; and the benefit is the pure highest knowledge.

The ego (self) within the body the upholder of the frame, is the Gârhapatya fire; and into this the offering is thrown.

The ego (self) asks for everything knowable in the universe as its offering. This is the internal Yajna. This Yajna is going on daily in this body and it is going on everywhere in the world, outside and inside.

There are often conflicts between the mind and the organs of senses. The senses point out that without their functioning, mind would not apprehend anything. The five Vayus argue among themselves, which among the five is the most important. The mind in turn points out that in its absence, the senses have no purpose and cannot function. Brahma, the creator resolves the dispute,

“You are all greatest, and not greatest. You are all possessed of one another’s qualities. All are greatest in their own spheres, and all support one another. There is one unmoving vital. The others are moving about in the body. Being friendly with one another, and pleasing one another, go away happily. Welfare be to you. Support one another.”

The discussion then shifts to which of the five Vayus came first and how do they move about in the body. Brahmana explains that the combination of Udana and the mind produces the sensations and the desire. Vyana and Samana produce blood and semen. The combination of semen and ovaries produce Prana, which is followed by Apana.The pair-Prana and Apana- move upward and downward in the body. The other pair of Samana and Vyana move transversely. Samana’s function is the digestion of food, while Vyana distributes the essence of the digested food to all parts of the body through the Nadis. Prana and Apana controls Samana and Vyana. The former two-Prana and Apana- are in turn controlled by Udana, which thus controls all the rest life-winds. Into that Udana, all the other life-winds merge. Udana in turn is controlled by penance (Tapasya). Penance and Yoga then destroy the round of rebirths and leads to absorption into Brahman.

The fire in these passages stands for Self. One has to get rid of all notions of conflicts and dualities of existence and non –existence, by offering them into the fire of Self. That is the yajna leading to the final emancipation.

There is then a discussion about the difficulties in understanding within the forest of knowledge. For instance, the syllable Om might not mean the same to all. The snakes may take it to mean, “to bite”, the demons “to deceive”, the gods “to give” and the sages “for self-control” etc.

This is followed by a discussion that upholds the virtues of non-violence.

The second section concludes with the thought that there is no single way to final emancipation but there are many. One has to choose the apt way for him.

The Brahmana’s wife attains her emancipation.

Krishna ends the second section with a remark that the Brahmana in the discussion represented Manas (intuition) while his wife represented Buddhi (intellect).All truths are not understandable by the intelligence alone.

***

The third section comprises a discussion between an enlightened Guru and his disciple. The discussion commences with the disciple submitting a comprehensive plea “which is the highest truth? What are called the qualities by the good? And what paths are happy? What is pleasure and what sin?”

The Guru launches into an elaborate explanation of the scheme of the three Gunas-Satva (the very fact of being -goodness), Rajas (the dust- passion) and Tamas (darkness).

The word sattva is derived from “sat”, which conveys the meaning of being or existing. It also has the sense of real or true. Sat also means good or virtuous. Thus sattva literally means “existing-ness” or goodness.

The word rajas is derived from the verbal root “raïj-” meaning of which ranges from “being colored”, to “being affected or attracted”. The word is used to denote things which color or partially darken the sky, such as mist, clouds and dust. In a more abstract sense it refers to emotion and powerful and controlling feelings.

Tamas is darkness. It is opposed to sattva in being heavy (guru) and in causing ignorance (ajïäna), by obscuring knowledge (jïänam ävåtya) and the ability to know. It also resists rajo-guëa as it restrains the motion of things and produces the state of apathy and indifference. The predominance of tamo-guëa thus results in indolence, sleep and confusion

Tamas the Darkness is associated with obscurity, delusion, depravity, ignorance, apathy, error and sinful actions.

Rajas the Passion is associated with activity, desire, impurity, passion, feelings and misfortune. When it prevails, it causes more actions, production and restlessness.

Satva the goodness is marked by light, lightness and faith. It is associated with the values of Virtue, kindness, purity and happiness; indicating that that existing is not contemptible or regrettable.

The gunas cannot be explained altogether distinctly from one another. Rajas, Satva, and Tamas are mixed up with one another. They are attached to one another, serve one another, they feed on one another. They all depend on one another, and likewise follow one another. They act, unperceived, by turns in the several places in several ways. Everything in the world is made of these three gunas. The creation of the gunas is eternal.

As long as there is goodness so long, darkness exists. And, as long as goodness and darkness exist, so long the passion exists. They perform their journey together, in union, and moving about collectively.

Where Tamas is dominant in the lower entities, there the Rajas is present to a little extent, and the Satva to a lesser extent. Where Rajas is dominant, there Tamas is present to an extent and Satva to some extent. And, where Satva is developed, there the Tamas is in a little extent and Rajas to some extent. The shortcoming of one of the gunas leads in every case to the excess of the others.

Where Tamas is restrained, Rajas prevails there. Where Rajas is restrained, Satva prevails there .Whatever there is in this world, all that is made of these three qualities

“The light of the sun- it is the Virtue (Satva), its heat the desire (Rajas), its eclipses the darkness (Tamas): in such a way, the three tendencies spread in all the stars.”

Those who adhere to the ways of Satva go up; the Rajas remain in the middle; the men of the quality of Tamas, being connected with the lowest quality, go down.

“He who understands correctly the unperceived, and the gunas, and its pure operations, he, freed from the body, understanding the truth about (all) distinctions, and being free from all misery, is released from all gunas.”

The discussion then continues, taking up typical notions of samkhya, explaining how the world is built from the Unmanifested (avyakta) to the Great Soul (mahat), then to the self-awareness (ahamkara), then to the material and subtle elements. The Samkhya is a dualistic system, separating the mind from the matter: the matter spreads in order that, at the end, the mind does no more need it, and discovers its profound independence.

That is illustrated by the image of a dancer bewitching her spectator until the latter discovers the illusion represented by this dance. Besides, the discussion puts the emphasis on the impermanence of this world, on the necessity to end ones life as a hermit:

“who brings from all sides his senses back into himself as a tortoise its limbs to obtain the Sacred (Brahman). He, who, at the time of his death, withdraws into himself not becoming confused; he, who masters his breathing by means of respiratory exercises, obtains immortality.”

Finally, the discussion ends by an invitation to meditate.

“Expelling all impressions and restraining the self in the Self, he understands that holy Brahman, than which nothing greater exists. …One who is alike to all beings; who is without attachment; who is without expectations, and who looks alike on everything can reach this goal. I have now declared everything to you. Act thus forthwith; then you will acquire perfection.”

Arjuna finally questions Krishna, who was the Guru and who was the disciple.

Krishna replies,” I am the preceptor, the mind is the pupil.” The commentator Arguna Mishra explains it;” The meaning of this is that anybody who has not acquired knowledge is treated here as a pupil; there is no other special pupil intended.”

You are all greatest, and not greatest.

You are all possessed of one another’s qualities.

All are the greatest in their own spheres,

and all support one another.

Being friendly with one another,

and pleasing one another, go away happily.

Welfare be to you! Support one another.

CONTINUED IN PART TWO

References:

http://www.phx-ult-lodge.org/anugita.htm

http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/sbe08/sbe0827.htm

Introduction to Anugita https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/sbe08/sbe0827.htm

Next:

Anugita (2 of 2)-