Symbolism of the temple

A Temple is a huge symbolism; it involves a multiple sets of ideas and imagery.

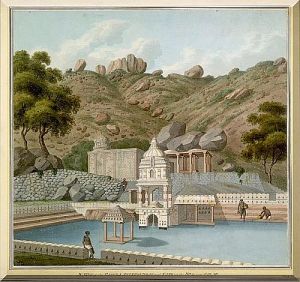

The temple is seen as a link between man and god; and between the actual and the ideal. As such it has got to be symbolic. A temple usually called Devalaya, the abode of God, is also referred to as Prasada meaning a palace with very pleasing aspects. Vimana is another term that denotes temple in general and the Sanctum and its dome, in particular. Thirtha, a place of pilgrimage is it’s another name.

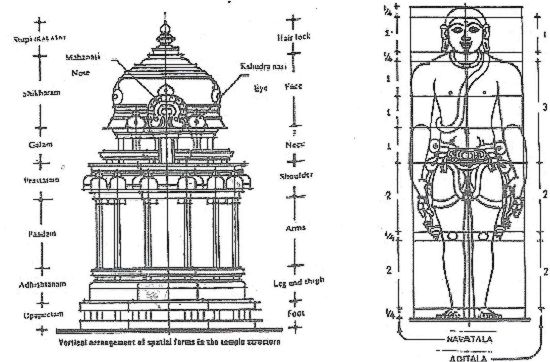

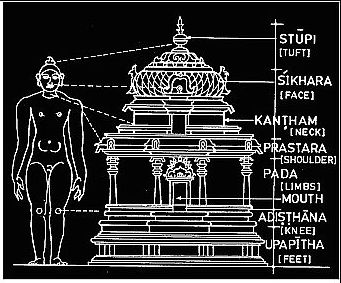

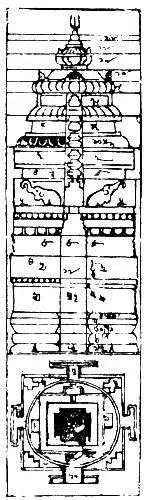

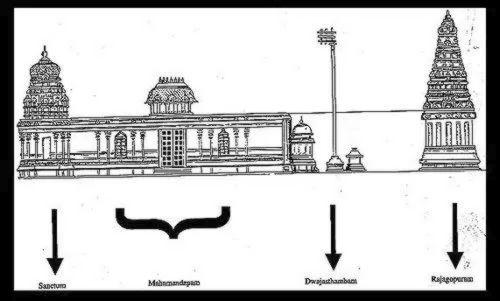

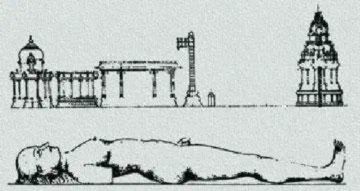

The symbolisms of the temple are conceived in several layers. One; the temple complex, at large, is compared to the human body in which the god resides. And, the other is the symbolisms associated with Vimana the temple per se, which also is looked upon as the body of the deity. And the other is its comparison to Sri Chakra.

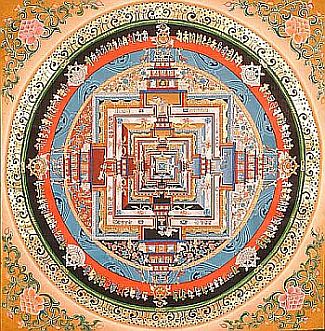

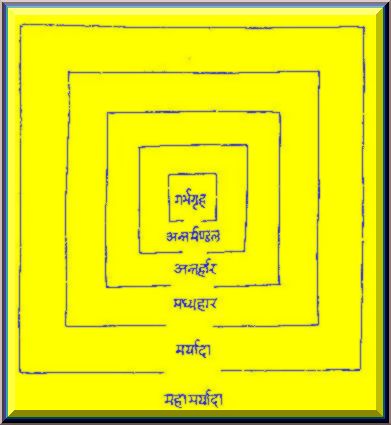

Let’s start with the temple complex being looked upon as a representation of Sri Chakra.

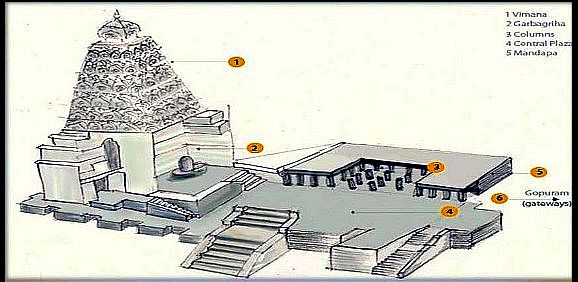

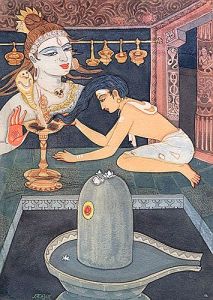

The shrine is itself an object of reverence. The icon at the center of the temple is the image of divinity and its purity that generations after generations have revered and venerated. That image residing at the heart of the temple is its life; and is its reason. One can think of an icon without a temple; but it is impossible to think of a temple without an icon of the divinity. The very purpose of a temple is its icon. And, therefore is the most important structure of the temple is the Garbagriha where the icon resides.

There are also views that assert saying that the temple has a sanctity of its own , independent of the icon; and, the icon’s sanctity is related to that of the temple . This view is based on the premise that even before the icon is placed within it, the temple-structure , is indeed sacred as its womb (Grha-garbha); and, the sanctum becomes the Gabha-griha (womb-house) only after the icon is installed within it. The temple (ayatana , the abode) and the image of the divinity placed within it are, thus, mutually complimentary.

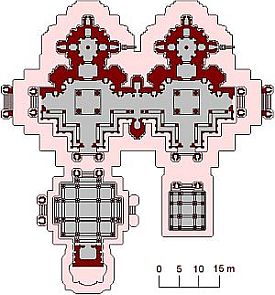

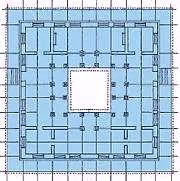

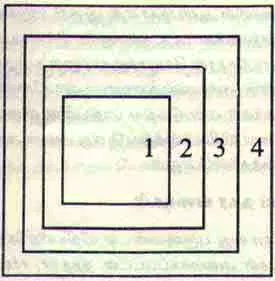

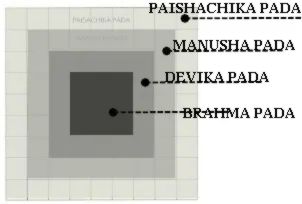

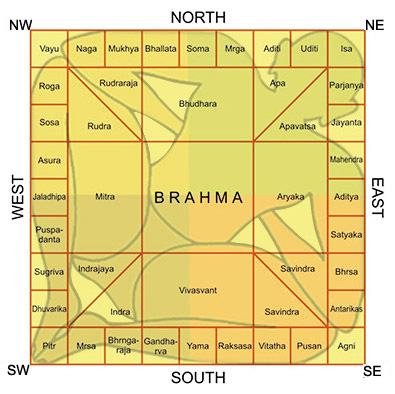

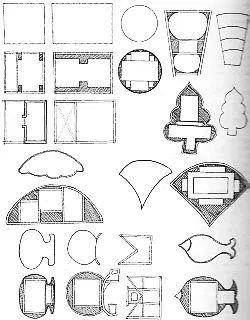

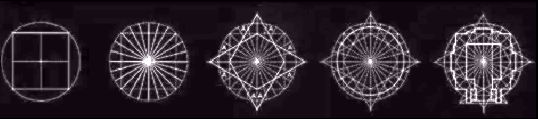

In fact, the entire temple is conceived as the manifestation or the outgrowth of the icon. And, very often, the ground-plan of a temple is a mandala. Just as the Sri Chakra is the unfolding of the Bindu at its centre, the temple is the outpouring or the expansion of the deity residing in Brahmasthana at the centre.

The temple as also the Sri Chakra employs the imagery of an all – enveloping space and time continuum issuing out of the womb. In the case of Sri Chakra the Bindu is the dimension-less and therefore imperceptible source of energy. The idol, the Vigraha, in the Garbagriha represents the manifestation of that imperceptible energy or principle; and it radiates that energy.

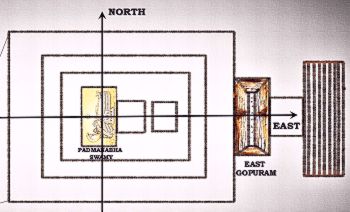

The devotee- both at the temple and in Sri Chakra- moves from the gross to the subtle. In the temple, the devotee proceeds from the outer structures towards the deity in the inner sanctum, which compares to the Bindu in the Chakra. The Sri Chakra upasaka too proceeds from the outer Avarana (enclosure) pass through circuitous routes and successive stages to reach the Bindu at the centre of the Chakr, representing the sole creative principle. Similarly the devotee who enters the temple through the gateway below the Gopura (feet of the Lord) passes through several gates, courtyards and prakaras, and submits himself to the Lord residing in the serenity of garbhagrha, the very hearts of the temple, the very representation of One cosmic Principle.

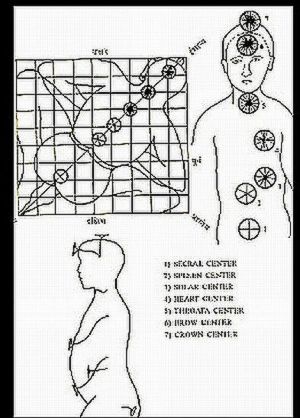

The other symbolism is that the human body is a temple in which the antaryamin resides. The analogy is extended to explain the various parts of the body as being representations of the aspects of a temple. In this process, the forehead is said to represent the sanctum; and the top of the head, the tower. The space between the eyebrows, the ajna chakra, is the seat of the divinity. The finial of the tower is the unseen the sahasrara located above the head.

Accordingly, the sanctum is viewed as the head; and Right on top of that head is the passage through which the currents of life ascend to the tower through that stone slab Brahma-randra_shila. Around the four corners of this slab are placed the images of the vehicles or emblems that characterize the icon inside the sanctum.

Garba Gruha Sirahapoktam; antaraalam Galamthatha; Ardha Mandapam Hridaya-sthanam Kuchisthanam; Mandapomahan Medhra-sthaneshu; Dwajasthambam Praakaram Janjuangeecha Gopuram Paadayosketha Paadasya Angula Pokthaha Gopuram Sthupasthatha Yevam Devaalayam angam uchyathe” – Viswakarmyam Vastu Shastra

***

Another interesting aspect is that the temple concept is a curious mixture of Vedic, Tantric and Agama principles. The Tantra regards the human body as a Mandala; and it is mobile (chara or jangama) Mandala. The Agama shastras regard a temple too as Mandala; and here it is an immobile (achala or sthavara) Mandala. The analogy of the temple with the human body finds closer relationships.

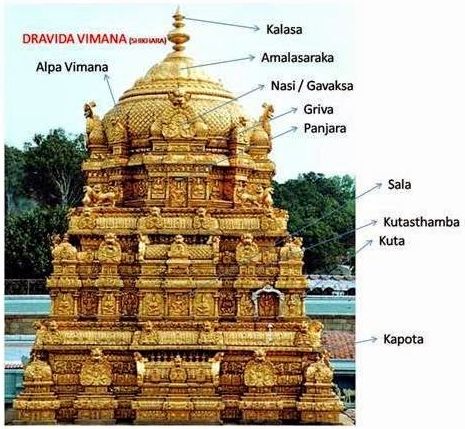

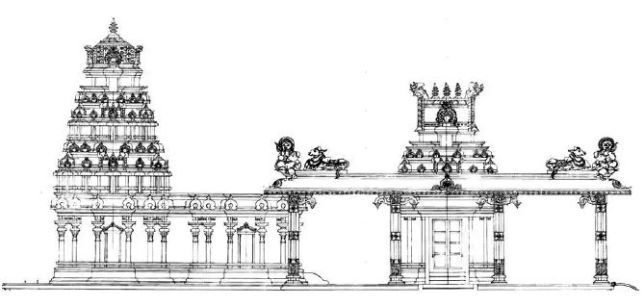

The symbolism extends to the conception of Vimana or the central part of the temple as the physical form of god. For instance, the sukanasi or ardhamantapa (the small enclosure in front of the garbhagrha) is the nose; the antarala is the neck; the various mantapas are the body; the prakaras are the hands and so on. Vertically, the garbhagrha represents the neck, the shikhara (superstructure over the garbhagrha) the head, the kalasha (finial) the tuft of hair (shikha) and so on.

The names assigned to various parts of the Vimana seem to go along with this symbolism. For instance, Pada (foot) is the column; jangha (trunk) is parts of the superstructure over the base; Gala or griva (neck) is the part between moulding which resembles the neck; Nasika (nose) is any nose shaped architectural part and so on. The garbhagrha represents the heart and the image the antrayamin (the indwelling Lord). These symbolisms also suggest seeking the divinity within our heart.

The temple is also seen as a representation of the subtle body with the seven psychic centres or chakras. In the structure of the temple, the Brahma randra is represented in the structure erected on top of the sanctum. The flat-roof (kapota) of the sanctum is overlaid by a single square stone slab known in the texts as Brahma-ranhra-sila (the stone denoting the upper passage of life). The sanctum is viewed as the head; and right on top of the head is the passage through which the currents of life ascend to the tower through this stone slab.

Interestingly, the Kalasha placed on top of the Vimana is not imbedded into the structure by packing it with mortar or cement. It is, in fact, placed in position by a hollow rod that juts out of the centre of the tower and runs through the vase, the Kalasha. It is through this tube that the lanchana ‘tokens’ (cereals and precious stones) are introduced. One of the explanations is the hallow tube represents the central channel of energy the Shushumna that connects to the Sahasra, the seat of consciousness, through the Brahma randra.

The other symbolisms associated with the Sanctum and the tower above it are, that sanctum is the water (aapa) principle and the tower over it is Fire (tejas); the finial of the tower (Vimana) stands for air (vayu) and above the Vimana is the formless space (akasha). The sanctum is thus a constellation of the five elements that are basic to the universe. And fire being the active element that fuses the others, the tower becomes an important limb in the structure of a temple.

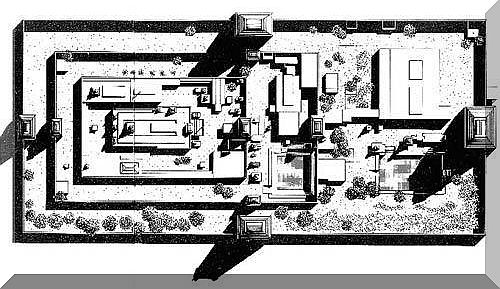

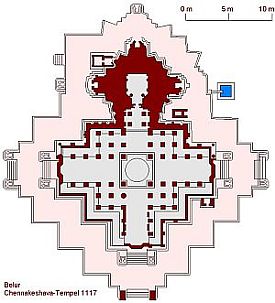

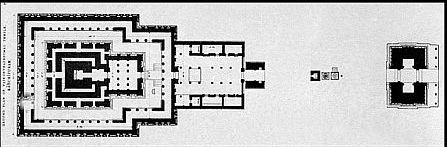

Symbolism of The Sri Vaikunta Perumal Temple at Kanchipuram

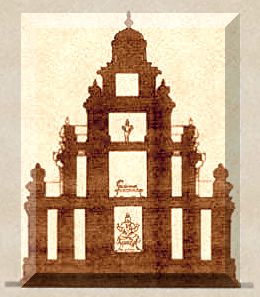

Dr D Dennis Hudson (1938-2006) who was the Emeritus Professor of World Religions at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts; and one who spent a lifetime in the study of Hinduism, particularly the Bhagavata tradition, in his book The Sri Vaikunta Perumal Temple at Kanchipuram, presents the interpretation of the symbolism that the temple structured as a three-dimensional Mandala.

His interpretation is based on Tirumangai Azhwar’s poetry and the theology of the Bhagavata Purana, which illumine layers of symbolism embodied in the architecture and sculpture of this temple.

According to Prof. Hudson, on the Sri Vaikunta Perumal Temple built in 770 C.E. by Nandivarman II Pallavamalla (731-796 C.E.) was , initially, given the name Parameshwara at the time of his coronation . And, it came to be known as Parameshwara-Vinnagaram (the abode of Vishnu), as sung by the Vaishnava saint, Tirumangai Azhwar.

The architecture of the Sri Vaikunta Perumal Temple is unique; with three sanctums placed one over the other, on the three floors; and, a concealed staircase leading to the upper floors.

The three sanctums enshrine Vishnu in three postures – seated, reclining and standing. The walls are adorned with more than fifty sculptures, besides the panels depicting the history of the Pallavas, leading to the coronation of Nandivarman.

According to Prof. Hudson, the temple reveals a visual theology, the `four formations (chatur-vyuha) as per the doctrine of Pancharatra Agama. The Vimana is structured as a three-dimensional Mandala.

He identifies the central figure in the sanctum of the ground floor as Vasudeva facing west, i.e. the Earth; Sankarshana facing north, the realm of human life; Pradyumna facing east towards heaven; and, Aniruddha facing south, the realm of ancestors.

The sculptural scheme matches the Pancharatra concept, representing the six `glorious excellences’ and the twelve murthis (dwadasa-namas). The six excellences are: the omniscient knowledge (jnana), power (bala), sovereignty (aishwarya), action (virya), brilliance (tejas) and potency (sakthi).

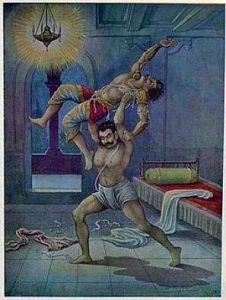

The Murti on the middle floor has the Vishnu is in lying pose known as Sheshashayee Vishnu, as he sleeps in the Kshirasagara. This Murti rests in a rather smaller room with plain walls. Here, the King serves Vishnu, as a disciple would serve his Guru.

The sanctum of the third floor represents the realm of space-time, depicting Vasudeva as he appeared in the human form of Krishna. The temple per se signifies the `body of God.

The staircase from behind the ground floor sanctum opens up a huge sculpture of Vishnu in sitting posture.

***

Iconography

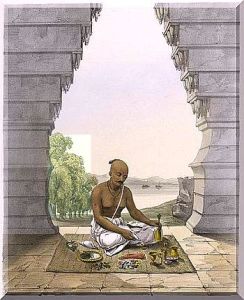

Before we deal with iconography per se , let’s briefly go-over some its general principles associated with it .

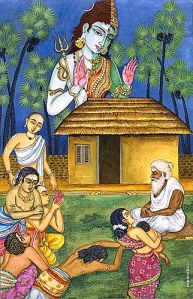

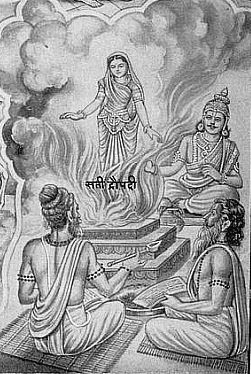

The Agama shastras are based in the belief that the divinity can be approached in two ways. It can be viewed as nishkala, formless – absolute; or as sakala having specific aspects.

Nishkala is all-pervasive and is neither explicit nor is it visible. It is analogues, as the Agama texts explain, to the oil in the sesame-seed, fire in the fuel, butter in milk, and scent in flower. It is in human as antaryamin, the inner guide. It has no form and is not apprehended by sense organs, which includes mind.

Sakala, on the other hand, is explicit energy like the fire that has emerged out of the fuel, oil extracted out of the seed, butter that floated to the surface after churning milk or like the fragrance that spreads and delights all. That energy can manifest itself in different forms and humans can approach those forms through appropriate means. The Agamas recognize that means as the archa, the worship methods unique to each form of energy-manifestation or divinity.

The idea of multiple forms of divinity was in the Vedas. Rig Veda at many places talks in terms of saguna, the supreme divinity with attributes. The aspects of the thirty-three divinities were later condensed to three viz. Agni, the aspect of fire, energy and life on earth; Vayu, the aspect of space, movement and air in the mid-region; and Surya the universal energy and life that sustains and governs all existence, in the heavenly region, the space. This provided the basis for the evolution of the classic Indian trinity, the Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu.

[Let me digress here for a while …

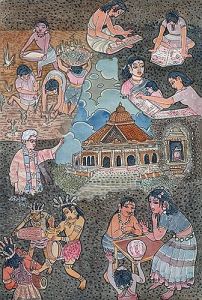

The study of Buddhist branch of Indian Iconography is one of the most interesting and fascinating subjects. In the present period, the study of the Buddhist Iconography is carried out mostly with reference to the available sculptures, bronzes, metal and miniatures sourced from various monuments.

As is well known, the earlier phase of Buddhism was free from a pantheon and representations of any gods and goddesses. The sculptural depictions found in the ancient monuments such as – Sanchi, Amaravathi and Bharhut etc., – relate to scenes of the Buddha’s life; and, to incidents picked up from the Jataka tales. The early representations of the Buddha were through symbols such as: the Bodhi-tree; the wheel of Dharma; the throne of exposition; sacred foot-prints; and so on.

The Buddha’s representation as a perfect human being came about much later, in the Gandhara School, perhaps through the influence of the Greek. The first image of the Buddha was fashioned in the Gandhara School, replicating the Greek Art.

The sculptures at Amaravathi are perhaps very near, in time, to the Gandhara School. That was followed by the Mathura School. Then come the sculptures of Saranath, Magadha, Bengal, Orissa, Java and Nepal (particularly in the Tantric context).

In the early Buddhism of the Pali tradition (Hinayana) , there was a marked absence of pantheon; and ritualistic worship of the idols of the Buddha or of any other deity.

But , with the birth and growth of the Mahayana ; and, particularly with the influx of the Vajrayana (which was a direct outcome of the Yogachara School) , the theories , principles and practices of the Buddhist iconography were thoroughly transformed into a totally different class.

The Tantric Vajrayana introduced many innovations of a revolutionary character that were alien and hitherto unknown to the Buddhist traditions.

For instance; it brought in the concept of five Dhyani Buddhas as embodiment of five Skandas or cosmic elements; and, formulated the theory of Kulas or families of the five Dhyani Buddhas, from which emerged numerous deities according to the disposition and the need of the practitioner.

Further, Vajrayana introduced the practice of worshiping the Prajna or Shakthi and a host of other gods and goddesses. It also elaborately composed articulate Sadhanas (Dhyana slokas) to enable the practitioner to visualize one’s chosen deity; and, to invoke the deity through its appropriate Mantras, Mudras, Mandalas and Yantras.

In order to heighten its psychic and emotional appeal, the Vajrayana introduced every conceivable tenet, dogma and ritual, calculated to enthuse its adherents of all classes – cultured, rustic, pious or aggressive etc. Many of those theories, worship-practices and deities were adopted from Hinduism as also from the folk traditions of Nepal and China.

As the Buddhism traveled far and beyond the Himalayas into Tibet, China and Mongolia; and, spread eastward right up to Korea and Japan, it imbibed and brought within its fold several characteristics, features and practices that were unique to each region. It is needless to say; Vajrayana, in due course, attained great fame and popularity.

Now, virtually, it is no longer possible to isolate the Buddhist iconography of India from its later Avatars in the new worlds, although they, initially, were influenced by the Buddhist Tantras of India. And, that is further complicated by the free and frequent interchange of deities and concepts among the three prominent religious systems – Hindu , Jaina and Buddhist.

I gratefully acknowledge the source , particularly the scholarly introduction to the Second Edition of The Indian Buddhist Iconography – mainly based on Sadhanamala by Prof. Benoytosh Bhattacharya ; Published by Firma K L Mukhopadhyay , Calcutta , 1958.]

The pantheon and the concept of polytheism gave tremendous impetus to all branches of Indian arts, literature and iconography. The polytheism is, in fact, the lifeblood of iconography; for it is only through a divinity with aspects one can represent and worship ones ideal with love, adoration and earnestness. Making an image involves an understanding of its attributes, virtues, powers, characteristics, symbols and its disposition. An image is the visual and concrete form of idealism; the idioms of beauty grace and power nurtured and honed by generations after generations. It is a representation of a community’s collective aspirations.

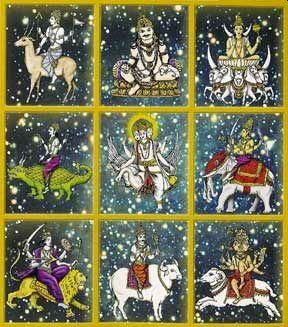

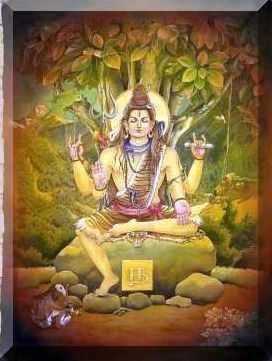

Iconographic representations of gods and goddesses are the idioms aiming to give expression to their attributes, powers, virtues and disposition. Multiplicity of heads denotes presence of their concurrent abilities; and multiplicity of hands denotes their versatile abilities. For instance, three heads of a divinity indicates trio guna (Guna-triad: Sattva, Rajas and Tamas) or shakthi traya [iccha (will), Jnana (consciousness) and kriya (action) shakthis or powers] . Four heads represent compreneshion or enveloping four Vedas ; or overseeing four directions . Five heads stand for five principles or elements (pancha-bhuthas) or five divine attributes or five stages of the evolutionary process

[shristi (creation), shthithi (expansion), samhara (withdrawal), triodhana (concealing) and anugraha (preserving till the commencement of the next cycle of evolution)]

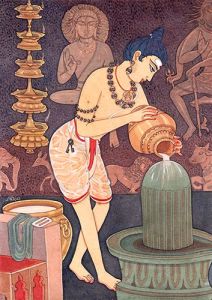

Not all divine representations are made through icons. Shiva is represented usually by a conic linga or an un-carved rock ; Vishnu and Narasimha are worshipped at homes as Saligrama (a special types of smooth dark stones found on bed of the Gandaki river); Ganapathi is best worshipped in the roots of the arka plant, and he is also represented by red stones (sona shila) or turmeric cones or pieces (haridra churna). The Devi in Kamakhya temple is worshipped in a natural fissure of a rock. Yet all these divinities have specified well defined iconographic forms.

According to the Agamas, icons can be constructed of stone; Kadira wood; metal; clay; precious stones; or painted on cloth. And, those made in metal are usually sculptured in wax form and then cast in metal.

kṛtvā pratinidhiṃ samyag dāru loha śilādibhiḥ | tat sthāpayitvā māṃ sthāne śāstra dṛṣena vartmanā || Padma Samhita Kriya Pada 1;5

Since the very purpose of the temple structure is the image residing in it; and the temple is regarded the virtual expansion of the image, let us talk for a while about temple iconography.

Iconography, in general terms, is the study and interpretation of images in art. But, in the context of this discussion it could be restricted to the study of icons meant for worship and the images used in temple architecture. The temple iconography is more concerned with the concept, interpretation and validity of the icon in terms of the themes detailed in the scriptures or the mythological texts; and with the prescriptions of the Shilpa Shastra. There is not much discussion on the styles of architecture or the art forms, per se.

Iconology could be understood as the study of the symbolism projected by the images. Here, the symbolism is the expression of reality through aesthetically presented suggestions; it is where two realms meet: the formless Absolute (Niṣkala) and the form with attributes (Sakala).

A symbol could be natural or conventional or otherwise. When we perceive a direct relationship between one orders of things with another a natural symbol develops.

[A short explanation about the term iconography. We are using it for want of a better term in English. The word icon is derived from Greek eikon; and it stands for a sign or that which resembles the god it represents.

In the Indian tradition what is worshiped is Bimba, the reflection or Prathima, the image of god, but not the god itself. Bimba means reflection, like the reflection of moon in a tranquil pool. That reflection is not the moon but an image (prathima) of the moon. In other words, what is worshiped in a temple is an idea, a conception or the mental image of god, translated to a form in stone or metal or wood; but, it is not the god itself. The principal Indian term for Iconography is therefore Prathima –lakshana, the study of images.

Various terms are used while referring to icons; such as:

- Bera : image;

- Mūrtī : an image with definite shape and physical features;

- Bimba: reflection of the original or model after which it is made (the Original Being of course is God);

- Vigraha : extension, expansion, form;

- Pratima : resemblance or representation;

- Pratīka : symbol;

- Rūpa : form; and ,

- Arca : object of adoration and worship.]

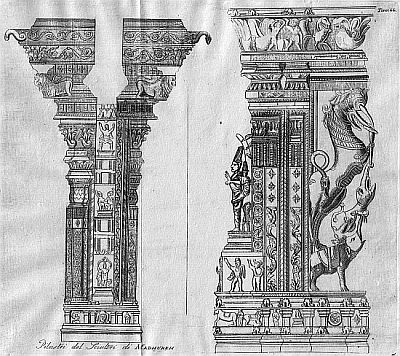

Apart from the Agamas, there are several texts that detail the processes involved in practicing the art; and specify the rules governing iconography and iconometry. The Brihat Samhita of Varahamihira (6th century AD) is an ancient text that provides descriptions of certain images. It refers to one Nagnajit, as the author of a contemporary work on Silpasastra – but not much is known about him or his work. Shukranithisara is another treatise which discusses aspects such as the proportions and the measurements recommended for the images of various classes and attributes. The subject he dealt with has since developed into Iconometry. Someshwara’s (a 1th century western Chalukya king) Abhilashitartha Chintamini contains interesting iconographical details of many important deities. And, Hemadri (13th century AD) who hailed from Dakshina Kannada region authored Caturvarga_chintamini, which deals with temple architecture and construction. He is credited with introducing a method of construction that did not use lime.

In addition, there are the major and authoritative texts that deal comprehensively with all aspects of Devalaya Vastu. These include Kashyapa shilpa samhitha, Mayamata, Manasara, Shilpa rathna, Kumaratantra, Lakshana_samuchayya, Rupamanada; and the Tantrasara of Ananda Tirtha (Sri Madhwacharya) , which contains sections dealing with the study of images (iconography and iconometry).

Among the puranas, the Agnipurana details the Prathima_lakshanam (the characteristics of images), Prathimavidhi (the mode of making images), and Devagraha nirmana (the construction of places of worship).

Similarly, the Matsya Purana (dated around second century AD) has eighteen comprehensive chapters on architecture and sculpture. This purana mentions as many as eighteen ancient architects (vastu_shatropadeshkaha): Brighu, Atri, Vashista, Vishwakarma, Brahma, Maya, Narada, Nagnajit, Visalaksa, Purandara, Kumara, Nanditha, Shaunaka, Garga, Vasudeva, Aniruddha, Shuka and Brihaspathi.

Many of these names appear to come from mythology; but quite a few of them could be historical. Sadly, the works of most of these savants are now lost. The Mathsya purana says that the best aspect of karma yoga is the building temples and installing deities; and therefore devotes several chapters to the subject of temple construction and image making.

The Vishnu purana (dated about 3rd century AD) too contains several chapters on the subjects of architecture and sculpture. Further, it includes the Vishnu_dharmotthara_purana (perhaps an insertion into the Vishnupurana at a later period), which is a masterly treatise on temple architecture, iconography and painting. This work which is in the form of a conversation between the sage Markandeya and the King Vajra is spread over 42 chapters. In part three of the text there is virtually a catalouge of the various deities with descriptions of their features, stance and gestures (mudras) apart from their disposition and attributes.

In addition to the Sanskrit texts, the Tamil works – Mandalapurusha’s Chintamini Nigandu and Sendanar’s Divakara nigandu, are well known and widely accepted. Besides, there is an ancient work by an unknown author, Silpam (perhaps a translation of an ancient Sanskrit text), which is popular among the shilpis.

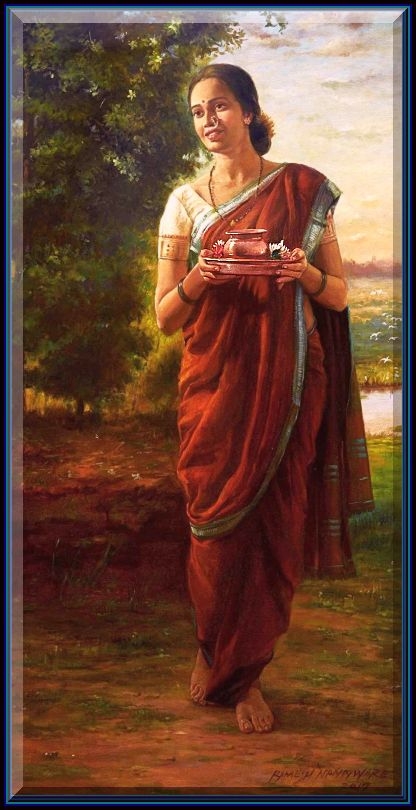

A special mention needs to be made about iconography ‘s (prathima lakshana) relation with Natyasastra.

The Shilpa and Chitra (painting) are closely related to Natyasastra (ca. second century BCE). The rules of the iconography (prathima lakshana), in particular, appear to have been derived from the Natyasastra. The Indian sculptures are often the frozen versions or representations of the gestures and poses of dance (caaris and karanas) described in Natyasastra. The Shilpa (just as the Natya) is based on a system of medians (sutras), measures (maanas), postures of symmetry (bhangas) and asymmetry (abhanga, dvibhanga and tribhanga); and on the sthanas (positions of standing, sitting, and reclining). The concept of perfect symmetry is present in Shilpa as in Nrittya; and that is indicated by the term Sama.

The Natya and Shilpa sastras developed a remarkable approach to the structure of the human body; and delineated the relation between its central point (navel), verticals and horizontals. It then coordinated them, first with the positions and movements of the principal joints of neck, pelvis, knees and ankles; and then with the emotive states, the expressions. Based on these principles, Natyasastra enumerated many standing and sitting positions. These, demonstrate the principles of stasis, balance, repose and perfect symmetry; And, they are of fundamental importance in Indian arts, say, dance, drama, painting or sculpture.

The demonstrations of those principles of alignment could be seen in the sama-bhanga of Vishnu, Shiva, abhanga of Kodanda-Rama and tribhanga of Nataraja; and in the vibrant movements of dance captured in the motifs carved on the walls of the Indian temples depicting gandharvas, kinnaras, vidyadharas and other gods and demigods. If the saala bhanjikas (bracket figures) recreate the caaris(primary movements) , the flying figures recreate the karanas (larger movements).The representations of about one hundred and eight of the karanas described in the Natyasastra find expression on the walls of temples spread across the country.

It is as if the rich and overpowering passages of Natyasastra are translated in to stone and published on temple walls.

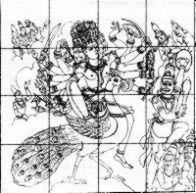

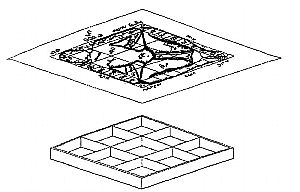

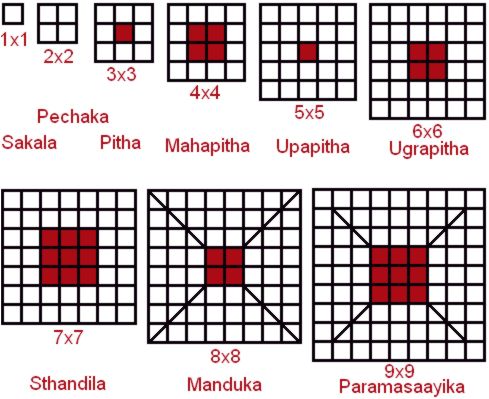

For the purpose of creating an image , initially, a square grid is divided into sixteen equal squares . These squares are grouped into six segments : Brahma -bhaga ( the central four squares) ; Deva -kesha or Deva shiro-alankara -bhaga ( two squares on top of Brahma-bhaga for depicting the crown or elaborate hair arrangement) ;Vahana-bhaga or peeta-bhaga ( space for pedestal – two bottom squares , below the Brahma-bhaga);Bhaktha -bhaga ( two bottom sqares on either side of Peeta -bhaga for locating images of the worshipping devotees); Devi-bhaga ( two squares each on either side of Brahma-bhaga for the accompanying female deities) ; and Gandharva-bhagha (two squares in the top on either side of Shiro-bhaga for depicting the Gandarvas).

The image of the main deity along with that of the consorts and subsidiary figures are located within the square grid. The central part of the main deity is accomodated in the Brahma-bhaga; its head or crown or hair-do is figured in the Deva-shiro-bhaga, while the f eet of the deity, the pedastal and the mount (vahana) are in the lower vahana-bhaga.

The vertical and horizontal axis of the square as also its diagonal axis of the square pass through what is known as the Brahma-bindu right at the centre of the Brahma-bhaga. It is at the Brahma-bindu the navel (nabhi) of the deity would be located. All other image parts are co-related to the Brahma-bindu.

Dhyana shlokas

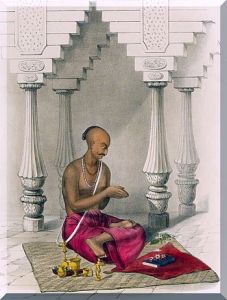

One of the main resources for a practicing shilpi is the collection of Dhyana shlokas.

Before a shilpi starts on a project to sculpt an image, he needs to be clear in his mind on its form, its aspects, its countenance, the details of its physiognomy, its facial and bodily expressions; its posture, details of the number of arms, heads and eyes; and details of its ornaments, ayudhas (objects it holds in its hands) etc. For this purpose, the Shilpis generally refer to a wonderful collection of most amazingly articulate verses called Dhyana Shlokas, the verses in contemplation.

Prof S K Ramachandra Rao , in his The Encyclopedia of Indian Iconography , writes :

These verses culled from various texts of Shipa Shastra, the Agamas and the Puranas; and also from Buddhist and Jain texts, describe, precisely, the postures (dynamic or static, seated or standing), the Bhangas (flexions – slight, triple, or extreme bends), Mudras (hand gestures), the attitudes, the nature, the consorts and other vital details of each aspect that provides the deity with power and grace. it is said that there are about 32 aspects or forms of Ganapathi, 16 of Skanda, 5 of Brahma, 64 of yoginis, and innumerable forms of Vishnu, Shiva and Devi .Each one of those forms has a Dhyana shloka illustrating its aspects and attributes.

[ As regards Vajrayana Buddhism, the Sadhanamala, a highly specialized Buddhist Tantric text, is a collection of Dhyana slokas (composed perhaps between the 5th and the 11th century), which deals with the Vajrayana Buddhist Tantric meditative practices; and , it provides detailed instructions on how the images of 312 Buddhist deities are to be visualized and invoked; each with its appropriate Mantra . The descriptions are meant to aid meditation; and, also to serve as a practical guide to the sculptors and painters. It enables the practitioner to visualize the nature, disposition, virtues and detailed iconographic features of a deity.]

Dhyana shlokas are more than prayers or hymns; they are the word-pictures or verbal images of a three-dimensional image. They help the Shilpi to visualize the deity and to come up with a line drawing of the image. It is said that there are more than 2,000 such Dhyana shlokas. How this collection came to be built up over the centuries is truly amazing. These verses have their origin in Sanskrit texts; and the scholars who could read those texts knew next to nothing about sculpture. The Shilpis who actually carved the images had no knowledge of Sanskrit and could not therefore read the texts or interpret the shlokas. This dichotomy was bridged by the generations of Shilpis who maintained their own set of personal notes, explanations and norms; as also references to shlokas; and passed them on to their succeeding generations and to their disciples.

[ Ram Raz (Rama Raja) (1790–1830) in his remarkable Essay on the Architecture of the Hindús also observed that only a few Brahmins could assist him in interpreting the Shilpa Shastras but they had no idea what so ever of architecture. The active rural craftsmen he approached were ignorant of Sanskrit and were unable to read the texts, their extensive practical knowledge having been learnt through pupillary succession. There seemed to be no interdependence between theoretical treatise and practical process.]

Thus, among the many traditions (parampara) inherited in India, the tradition of Vishwakarma is unique. The mode of transmission of knowledge of this community is both oral and practical. The rigor and discipline required to create objects that defy time and persist beyond generations of artists, has imbued this tradition with tremendous sense of purpose, and zeal to maintain purity and sensitivity of its traditions; and to carry it forward. This has enabled them to protect and carry forward the knowledge, the art and skills without falling prey to the market and its dynamics.

With the emergence of the various academies of sculpture and organized efforts to collate and publish the old texts with detailed explanations, there is now a greater awareness among the shilpis of the present day. Yet, the neglect of Sanskrit and inability to read the texts in Sanskrit is still an impediment that badly needs to be got over.

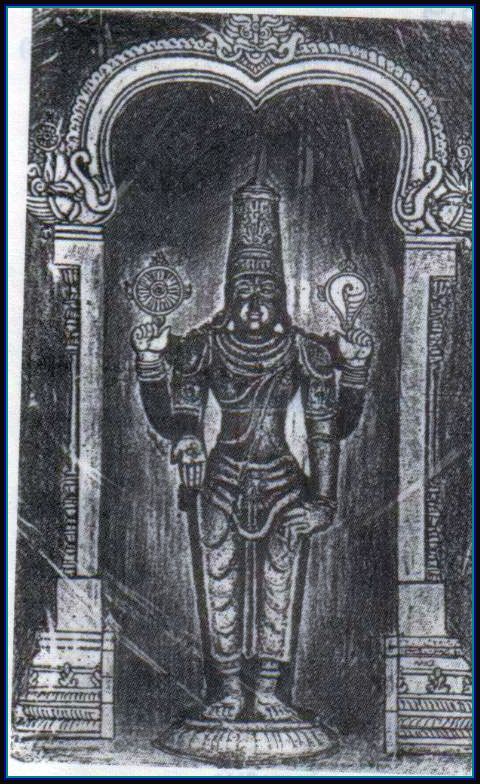

Please look at the summary of a few Dhyana shlokas.

The image of Lord Narayana must be made with ten , eight, four or two arms. His head should be in the form of an umbrella, his neck should be like counch, his ears like sukthi, he should have high nose, strong thighs and arms. His breast must bear the Srivatsa mark and be adorned with the Kaustubha gem. He should be made as dark as the Atasi (Linum usitatissimum), clad in yellow robes, having a serene and gracious countenance. He should be wearing a diadem and ear-rings. Of the eight hands the four on the right side must have the sword(nandaka), mace(kaumodaki), arrow and abhaya _hastha, mudra of assurance and protection (the fingers raised and the palm facing the devotees), and the four on the left side, the bow(saranga), buckler, discus (sudarshana) and conch (panchjanya).

In case the image is to have only four arms, the two hands on the right side will display the abhaya mudra or lotus; and discus respectively. And, in his hands in the left, he holds the conch and mace.

And, in case he is made with only two arms, then the right hand bestows peace and hope (shanthi-kara-dakshina hastha) and the left holds the conch. This is how the image of the Lord Vishnu is to be made for prosperity.

When Vishnu is two armed and carries discus and mace, he is known as Loka-paala-Vishnu.

Yogasana_ murthi (yoga Narayana) is Vishnu seated in yogic posture on a white lotus, with half-closed eyes. His complexion is mellow –bright like that of conch, milk or jasmine. He has four hands with lower two hands resting on his lap on yogic posture (yoga mudra). ; And the upper two hands holding conch and discus. He is dressed in white or mild red clothes. He wears modest but pleasant ornaments. He wears an ornate head dress or a coiled mop of hair. [Yogesvara is sometimes shown with four faces and twelve hands.]

Surya, the Sun-God should be represented with elevated nose, forehead, shanks, thighs, cheeks and breast; he should be dressed in robes covering the body from breast to foot. His body is covered with armor. He holds two lotuses in both of his hands, he wears an elaborate crown. His face is beautified with ear-rings. He has a long pearl necklace and a girdle round the waist. His face is as lustrous as the interior of the lotus, lit up with a pleasant smile; and has a halo of bright luster of gems (or, a halo that is made very resplendent by gems on the crown). His chariot drawn by seven horses has one wheel and one charioteer .Such an image of the Sun will be beneficial to the maker (and to the worshipper).

Surya, the Sun-God should be represented with elevated nose, forehead, shanks, thighs, cheeks and breast; he should be dressed in robes covering the body from breast to foot. His body is covered with armor. He holds two lotuses in both of his hands, he wears an elaborate crown. His face is beautified with ear-rings. He has a long pearl necklace and a girdle round the waist. His face is as lustrous as the interior of the lotus, lit up with a pleasant smile; and has a halo of bright luster of gems (or, a halo that is made very resplendent by gems on the crown). His chariot drawn by seven horses has one wheel and one charioteer .Such an image of the Sun will be beneficial to the maker (and to the worshipper).

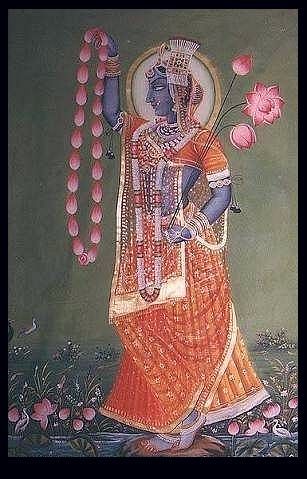

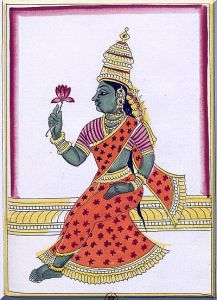

The dhyana shloka preceding the middle episode of Devi Mahatmya gives the iconographic details of the Devi. The Goddess is described as having eighteen arms, bearing string of beads, battle axe, mace, arrow, thunderbolt, lotus, bow, water-pot, cudgel, lance, sword, shield, conch, bell, wine-cup, trident, noose and the discuss sudarsana. She has a complexion of coral and is seated on a lotus.

The Mahakali is “Wielding in her hand the sword, discuss, mace, arrow, bow, iron club, trident, sling, human head, and conch, she has three eyes and ornaments decked on all her limbs. She shines like a blue stone and has ten faces and ten feet. That Mahakali I worship, whom the lotus born Brahma lauded in order to slay Madhu and Kaitaba when Hari was asleep”.

Pancha bera

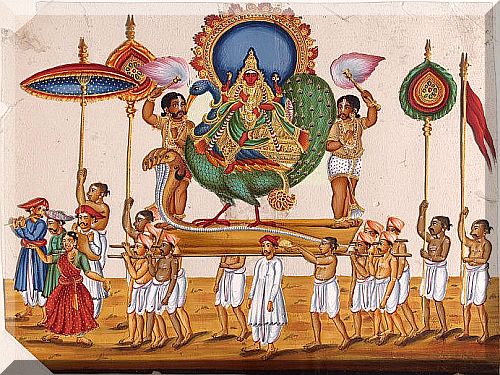

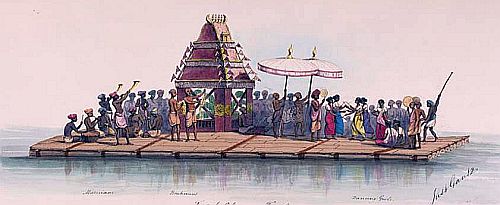

The images in the Hindu temples can be classified into three broad groups: Shaiva, Shakta and Vaishnava, representing the three cults of Shiva, Shakti and Vishnu, respectively. The images in the temple could be achala (immovable) Dhruva-bimba or dhruva-bera; and chala(movable). The chala bera, usually made of pancha loha (alloy of five metals), are meant for other forms of worship and ceremonial services.

The dhruva-bera is the immovable image of the presiding deity of the temple and resides in the sanctum and to which main worship is offered (archa-murti). It is usually made of stone. In a temple following the Vaikhanasa tradition, the immovable (dhruva-bera) represents the primary aspect of the deity known as Vishnu (Vishnu-tattva). The other images in the temple that are worshiped each day during the ritual sequences are but the variations of the original icon (adi-murti). These other forms are emanations of the main idol, in successive stages. And, within the temple complex, each form is accorded a specific location; successively away from the Dhruva bera.

A major temple, apart from the Dhruva bera, would usually have four or five representations of the principal deity (pancha bera).They are:

Dhruvam tu grāma rakṣārtham; arcan artham tu Kautukam | snānārtham Snapanam proktam; balyartham Bali-berakam | Utsava cotsavartham ca Paṅca-Bera prakalpitāḥ ||

:- Kautuka –bera is a mini replica of the main idol (usually madeof gems, stone, copper, silver, gold or wood and about 1/3 to 5/9 the size of the Dhruva-bera), and is placed in the sanctum near the main idol and is connected to it by a metal string or silk thread. It receives all the daily worship(nitya-archana) including those of tantric nature.

:- The next is the Snapana-bera (usually made of metal and smaller than Kautuka) which receives ceremonial bath (abhisheka) and the occasional ritual- worship sequences(naimitta-archana).

:- The third is the shayana-bera, to which the services of putting the Lord to sleep are offered.

:- The fourth is the Uthsava (always made of metal); is meant for taking the idol out of the temple premises on ceremonial processions.

:- The fifth idol is Bali – bera ( always made of shiny metal) taken out , daily , around the central shrine when food offerings are made to Indra and other devas, as well as to Jaya and Vijaya the doorkeepers of the Lord ; and to all the elements.

To this, sometimes another icon is added for daily worship, special rituals, and processions and for food-offering, it is known as Bhoga-bera.

These five forms together make Pancha bera or Pancha murti. But, these different icons are not viewed as separate or independent deities; but are understood as emanations from the original icon, Dhruva–bimba.

[There is also a mention of A Karma- bimba, which , in effect, is a proxy image of the main Icon; and , it is used for a variety of practical purposes. The life force (Prana) from the main Icon is transferred into the karma bimba for a short duration for serving the particular purpose. Thereafter it is transferred back into the main Icon. These karma-bimbas have to correspond, in every way, to the iconic forms of the Mula-bimba or the Dhruva-bera. These relate to the disposition, attributes, postures and other iconographic features of the Dhruva-bera.

karmārcā sarvathā kāryā mūla-bimba anusāriṇī | Viśvaksena Samhita 17; 11.

But, in terms of their size: the karma-bimbas should be either a quarter, a third or half of the height of the Mula-bimba.

Mūla-bimba samucchrāyāṃ dvidhā vāpi tridhāpi va | caturdhā vā saṃvibhajya eka bhāgena kalpayet || utsavārcāṃ tad ucchrāyāṃ dvidhā vāpi tridhāpi vā | caturdhā vā vibhajya eka bhāgena parikalpayet || īśvara Samhita 17; 242, 243 || ]

[One of the few cases (that I am aware of) where the principal deity is taken out of the sanctum for procession, is that of Lord Jagannath of Puri. Such images are regarded chala-achala (both movable and immovable)]

According to Vyuha -siddantha of the Agamas, the dhruva bera which is immovable represents Vishnu (Vishnu-tattva); and it symbolizes Para, the transcendent one (Vishnu). The kouthuka is bhoga (worship idol) representing purusha (personification of the Supreme), Dharma and Vasudeva. The snapana is ugra (fearsome aspect) represented by Pradyumna or Achutha. The uthsava bera is vaibhava (the resplendent) representing Jnana (knowledge), truth (Sathya) and Sankarshana. And, the Bali bera is antaryamin (one who resides within) representing Vairagya (spirit of renunciation) and Aniruddha.

And again it is said, Purusha symbolized by Kautuka-bera is an emanation of the Dhruva-bera. Satya symbolized by Utsava-bera emanates from Kautuka-bera. Achyuta symbolized by Snapana-bera emanates from Utsava-bera. And, Aniruddhda symbolized by Bali-bera emanates from Bali-bera.

The symbolisms associated with the four murtis (chatur-murti) are many; and are interesting. The four are said to compare with the strides taken by Vishnu/Trivikrama. The main icon represents Vishnu who is all-pervasive, but, does not move about. When the worship sequences are conducted, the spirit (tejas) of the main idol moves into the Kautuka,-bera, which rests on the worship pedestal (archa-pitha). This is the first stride of Vishnu.Again, at the time of offering ritual bath, the tejas of the main idol moves into the Snapana-bera which is placed in the bathing-enclosure (snapana –mantapa). This is the second stride taken by Vishnu. And, the third stride is that when the Utsava-bera is taken out in processions. This is when the tejas of the Main idol reaches out to all.

In Marichi’s Vimana-archa-kalpa the five forms, five types of icons, the pancha-murti (when Vishnu is also counted along with the other four forms) are compared to five types of Vedic sacred fires (pancha-agni): garhapatya; ahavaniya; dakshinAgni; anvaharya; and sabhya. These in turn are compared to the primary elements (earth, water, fire, air, and space). And, the comparison is extended to five vital currents (prana, apana, vyana, udana and samana).

Further it is explained; the Vaikhanasa worship-tradition retained the concept of Pancha-Agni, but transformed them into five representations of Vishnu (pancha –murthi): Vishnu, Purusha, Satya, Achyuta and Aniruddha. And, that again was rendered into five types of temple deities as pancha-bera: Dhruva, Kautuka, Snapana, Utsava and Bali.

Let us, for instance, take the case of the idols in the shrine on the hills of Tirumala. The practices at the Tirumala temple are slightly at variance with the standard procedures, perhaps because the temple predates most of the other temples in South India and that it has a tradition of its own.

The dhruva bera at the Tirumala shrine is of course the magnificent and most adorable image of the Lord made of hard-black-stone; and has a recorded history of about two thousand years. He is addressed as Sri Venkateswara, Sri Srinivasa and by host of other names. (Let’s talk more about the dhruva bera, towards the end of this post).

It is said that around the year 614 AD, the Pallava Queen, Devi Samavai (also known as Kadavan-Perundevi), donated an almost (but not exact- as it holds the Sanka and Chakra ) replica of the dhruva bera, made of silver. In terms of the Agama texts, this image is called kouthuka bera; but in the Tirumala shrine it is called Bhoga Srinivasa., In Tirumala , the kauthuka serves as snapana bera too (that is, the one to which ceremonial bath service is rendered). This image has come to be known as Bhoga srinivasa; perhaps because the other services such as the daily ceremonial bath and Ekantha seva that are due to the dhruva _bera are rendered to it. There is a six cornered Vaishnava chakra (mandala)- in the shape of two inter placed equilateral triangles – placed at the foot of the kauthuka, representing the six virtues of knowledge (jnana), abundance (Aishvarya), power (shakthi), strength (bala), resplendence (tejas) and valor or virility (veeerya). The kauthuka is placed right in front of the Lord’s foot stool (paada pitha) and is linked to the dhruva_bera through a string with strands of gold, silver and silk. It is ever linked to the dhruva bera and is never brought out of the antarala (bangaru vakili). For that reason it is also addressed as sambhandha-sutra-kauthuka-murthy.

The Uthsava_bera at Tirumala shrine is named Malayappan, the earliest reference to which is found in an inscription dated 1369 AD. This idol might have entered into the temple regimen with the rise of the Pancharathra School of worship. Malayappan is a very skillfully crafted, beautiful image, made of panchloha, standing three feet tall on a pedestal of fourteen inches. It does not greatly resemble the dhruva_bera. Yet, it has a very pleasing disposition and is modestly ornamented. His consorts Sridevi and Bhudevi (of about twenty-nine inches height) are on his either side. All services, processions and celebrations conducted outside the sanctum are rendered to Malayappan.

The Bali bera in Tirumala shrine is addressed as Koluvu srinivasa. After the rendering the ceremonial food service to the dhruva_bera, offerings are made to the bali_bera who accepts it on behalf of the basic elements in nature , the host of spirits guarding the temple and other minor deities. A unique feature of the bali_bera in Tirumala shrine is that, it seated on a golden throne placed in Snapana Mandapam, presides over the formal court summoned at the commencement of the day, where the day’s almanac is read out, and where the accounts of the previous day’s collections at the Srivari hundi are submitted. This is done is Snapana Mandapam before the dusk ;and, in Ghanta Mandapam after dawn. The traditional distribution of the daily remuneration, in the form of food grains and provisions, to the temple priests and attendant staff takes place in the presence of koluvu_srinivasa. It is not clear how this practice came into being at Tirumala.

The other bera in the Tirumala temple is the Ugra Srinivasa, which apart from the dhruva bera is perhaps the oldest idol in Tirumala shrine. But, it has a rather sad history. The earliest reference to this idol is in an inscription dated 10th century. Ugra Srinivasa was used as the Uthsava murthy till about 1330 A.D, when a fire broke out in the temple; and thereafter it was replaced by Malayappan. The Ugra Srinivasa no longer serves as the uthsava bera and it is never bought out of the temple after sunrise; except on a single occasion in a year (utthana dwadasi in karthika month-Kaisika Dwadasi ) that too well before the sunrise. It is feared that if the sunrays touch the idol, it would spark fire in the temple premises.

The iconography of Sri Venkateshwara in the Tirumala temple:

There are no known descriptions or specifications of the iconography of the Sri Venkateshwara idol in any texts of the Shilpa shastra. Till about the Vijayanagar period there were no temples of Sri Venkateshwara, outside Tirumala, Tirupathi and Mangapura regions. The idol does not also fall within the interpretations of any of the known schools of architecture such as Pallava, Chalukya, and Chola etc. That might be because the image of Sri Venkateshwara predates all such schools.

The sanctum at Tirumala is eka murthy griha a sanctum housing a single deity; Sri Vekateshwara is standing alone, not accompanied by his consorts. The icon is made of hard- black – polished stone (often described as saligrama shila) .Though the precise measurements of the image of the deity cannot be ascertained, it is said, it stands more than six feet in height, with the Kirita , the crown, measuring about twenty inches high; and the idol is mounted on a pedestal of about eighteen inches. The pedestal with lotus motif is almost at the ground level. The total height of idol is estimated to be a little more than eight feet (A person of normal height with arms raised just falls short of reaching the top of the idol’s crown) .

The idol, crafted with great skill, is wonderfully well proportioned and is very pleasing to look at. It has four arms though its two upper hands are always kept covered (for whatever reason). Of the other two hands, the right hand is in Varada mudra, in a posture of benediction, blessing the devotees. The left hand is almost near the left knee in Katyavalambita mudrawith the thumb almost parallel to the waist, as if to assure that the mire of the samsara , the mundane existence , is only knee deep for those who submit to him and seek salvation.

Let’s discuss some specific forms of iconography in the next segment.

Iconography continued in the next part…>

References:

Shilpa Soundarya by KT Pankajaksha

The Lord of Seven Hills by Prof. SKR Rao

Line drawings of kirita and ornaments

By the renowned Shilpi and Yogi Sri Siddalinga Swamy of Mysore

Other Line drawings are from Shilpa Soundarya

Other pictures are from internet

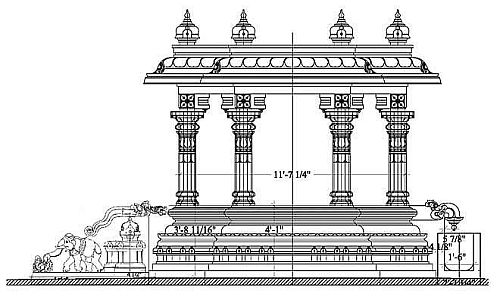

feet and nine inches. The sanctum is considered so holy that it is addressed as Koil Alwar meaning the divinity in the form of temple. The three sides of the sanctum (other than the one with the opening to view the deity) are enclosed by another set of wall/s. The total thickness of the walls surrounding the sanctum is about seven feet and two inches. Perhaps this is the most secure sanctum wall one can find. The pleasing Ananda Nilaya Vimana stands on these sets of walls. It is surmised that the outer wall might have been erected sometime around 1260AD.

feet and nine inches. The sanctum is considered so holy that it is addressed as Koil Alwar meaning the divinity in the form of temple. The three sides of the sanctum (other than the one with the opening to view the deity) are enclosed by another set of wall/s. The total thickness of the walls surrounding the sanctum is about seven feet and two inches. Perhaps this is the most secure sanctum wall one can find. The pleasing Ananda Nilaya Vimana stands on these sets of walls. It is surmised that the outer wall might have been erected sometime around 1260AD.

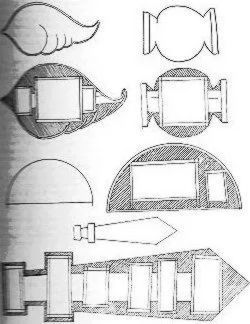

The ‘Barrel-vault’ also known as a tunnel vault or a wagon vault is an architectural design looking like an oblong wagon-top or a vault or resembling a boat placed up-side down, is rather an old feature of the Indian temple architecture. Its curvy shape lends the structure a semi-cylindrical appearance. Such a design is assigned with many names, depending on the architectural school that it was involved with. The various parts of the temple are given different names in different parts of India.

The ‘Barrel-vault’ also known as a tunnel vault or a wagon vault is an architectural design looking like an oblong wagon-top or a vault or resembling a boat placed up-side down, is rather an old feature of the Indian temple architecture. Its curvy shape lends the structure a semi-cylindrical appearance. Such a design is assigned with many names, depending on the architectural school that it was involved with. The various parts of the temple are given different names in different parts of India.

And, there is the Bhima-ratha, one of the five Rathas or architectural models, at Mahabalipuram. Like the other four Rathas, the Bhima–ratha is also a stone-version or a model of a wooden structure. It is said to replicate the Chaiyta-model. The Bhima-ratha is an Ektala or single tiered oblong structure, with a barrel-vaulted roof (Sala Vimana) like a tilted boat, and ornate columns.

And, there is the Bhima-ratha, one of the five Rathas or architectural models, at Mahabalipuram. Like the other four Rathas, the Bhima–ratha is also a stone-version or a model of a wooden structure. It is said to replicate the Chaiyta-model. The Bhima-ratha is an Ektala or single tiered oblong structure, with a barrel-vaulted roof (Sala Vimana) like a tilted boat, and ornate columns.

I

I

T

T

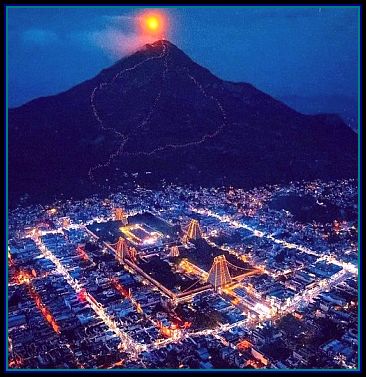

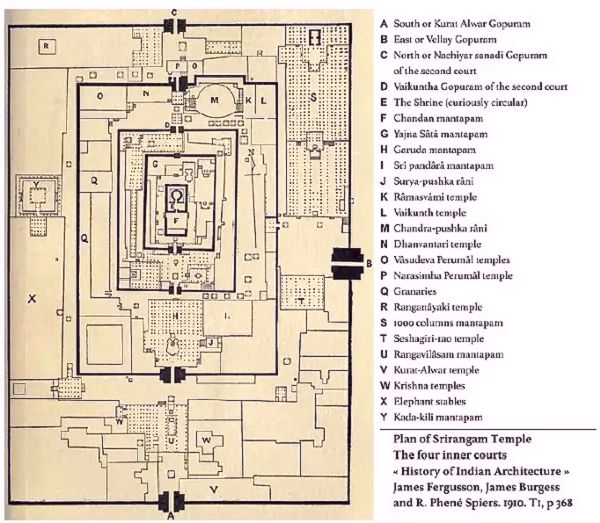

towers erected over the entrance gateways of these walls are the Gopuras. These rectangular, pyramidal towers, often fifty metres high dominate the city skyline. And, adorned with intricate and brightly painted sculptures of gods, demons, humans, and animals, have become the hallmark of southern architecture; though, strictly, they are not the essential aspect of a temple layout or its structure. The Gopura emphasizes the importance of the temple within the city.

towers erected over the entrance gateways of these walls are the Gopuras. These rectangular, pyramidal towers, often fifty metres high dominate the city skyline. And, adorned with intricate and brightly painted sculptures of gods, demons, humans, and animals, have become the hallmark of southern architecture; though, strictly, they are not the essential aspect of a temple layout or its structure. The Gopura emphasizes the importance of the temple within the city.

T

T

C

C

.jpg)