Differences with Marxism

Roy embraced Marxism as a philosophy of life that would change the world for better. He studied it deeply and tried hard to imbibe its principles into his faith, his working principles and as a guide to his many theses. During the later stages of his career in Comintern, after Stalin took control of the Communist Party and the USSSR, it dawned on him that Marxism in practice was altogether a different proposition from the Marxism in theory. The years of his incarceration in the Indian prisons allowed him time and opportunity to reflect upon various sorts of political philosophies that had been advocated and practiced over the centuries.

In the process, he also astutely examined the merits and de-merits of the Parliamentary system of Democracy and the practices of the Communist regimes – the “discrepancy between the ideal and the reality of the socialist order”. Roy then came up with his own theory of governance or a political, economic and social philosophy which he named it as Radical Democracy that we discussed in the earlier parts of this series.

Roy had a great admiration for Marx as a scholar and a theoretician who was very capable in drawing up strategies by translating objective statistics into subjective human experiences. Roy considered Marx as a humanist and a lover of freedom. Yet; Roy did not quite concur with some of the theoretical principles adopted by Marx as also with some assumptions that Marx made. Yet; Roy’s criticism is neither total rejection of Marxism; nor it ‘anti-Marxism’. Roy criticized the dogmatic and superficial application of Marxism. He tried to modify or keep aside some of its assumptions.

Though Roy examined Marx’s views on philosophy, history, sociology and materialism, he did not go into the technical details or the mechanics of Marx’s economic theories.

**

Roy’s basic objection of Marxism was that it retards the growth of free man; and that its “economic interpretation of history is deduced from a wrong interpretation of materialism”. The main elements here are human freedom and materialism.

Human freedom

As regards freedom, Roy held the view, as Ramendra Nath explains: freedom does not necessarily follow from the capture of political power in the name of the oppressed and the exploited….. A political system and an economic experiment which subordinates the man of flesh and blood to an imaginary collective ego, be it the nation or class, cannot possibly be the suitable means for the attainment of the goal of freedom. And therefore, Roy rejects “Dictatorship of any form, however plausible may be the pretext for it”; and, excluded it from the Radical-Humanist perspective of social revolution.

In his Introduction to Scientific Politics, Roy wrote: Those who regard Marxism as a closed system of thought cannot pretend to subscribe to principles of radicalism which knows no dogma and respects no authority”.

The central point of Roy’s critique of Marxism, as it was practiced, was that it ignored the dynamics of ideas; and disregarded the moral problems. According to Roy, there is a reciprocal interaction between the dynamism of ideas and the progression of social process.

Roy argued that the principle shortcoming of Marxism was its denial of individual liberty. The complete regimentation of Marxism left no room for individual freedom.

Marx had rejected the liberal concept of individualism after coming under the influence of Hegel’s theory of moral-positivism. And, that led to marginalization of the individual and his role. By rejecting or neglecting the concept of individual freedom Marx turned his back on the humanism of the earlier philosophers.

Roy, on the other hand, believed that Man was essentially a freedom loving being. He had always been struggling for freedom. And, his forming and joining the civil society and state was only on the hope and condition that his freedom would be protected. And if at any stage his freedom was threatened he rebelled against the oppressor in an attempt to guard his freedom.

[ Even in the judicial system , the harshest punishment that is usually handed down to a condemned criminal is to take away her/his freedom ; and, incarcerate her/him for life]

Materialism

According to Roy, Marx under the influence of Hegelian dialectics rejected the materialism of Feuerbach (which envisioned the coming dominance of politics and the natural sciences, displacing philosophy); and remarked ‘it was quite unfortunate of Marx’.

Roy believed that materialism pure, and simple, can stand on its own legs; and, therefore, he tried to de-link dialectics from materialism.

Roy considered the Hegelian heritage a weak spot of Marxism. Roy could not agree with Marx theory of Dialectical materialism. Roy observed that the Dialectical process of Marx does not leave any room for the greatest of the revolutionary aims: to change the world for better. Marx’s theory of dialectical materialism is in direct conflict with revolutionary ideals.

Roy revised and restated materialism in the light of twentieth century scientific developments. He envisaged a very close relationship between philosophy and science in bringing about intellectual revolution.

According to Roy, philosophy begins when man’s spiritual needs are no longer satisfied by primitive natural religion. And, no philosophical advancement is possible unless we get rid of orthodox religious and theological dogmas. The term ‘religion’ here also includes Marxism, Fascism, Nationalism and such other ’isms’.

The function of philosophy, as per Roy, is to know things as they are, and to find common origin of the diverse phenomena of nature, in nature itself. Thus, philosophy and science always go together. Thus, philosophy is the theory of life; a system of thought that endeavours to explain the world rationally and to serve as a reliable guide for life. It is also a way of thinking, which ensures a logical coordination of all the branches of positive knowledge.

Roy was opposed to speculative philosophy, which ‘ends in denying the existence of the only reality and declaring it to be a figment of man’s imagination’.

In sum, the task of philosophy, according to Roy, is not merely “to know things as they are, and to find the common origin of the diverse phenomena of nature, and, nature itself; to understand Man and his Universe…To explain existence as a whole”; but, more importantly, it is its power or force to change the world we live in, for better.

History and its interpretations

Roy also did not agree with the historical interpretations put forth by Marx. Roy strongly believed that Marx’s interpretation of history is defective, because it allowed no role for the mental activity in the social process – “History can never be interpreted solely with reference to materialistic objectivism”.

Marx’s history did not also seek to explain and analyze the primitive history of human species, wherein Man found satisfaction without pursuing economic factors. Thus, according to Roy, the philosophical materialism and Marx’s economic interpretation of history were disjointed.

Roy was not convinced with the Marxism notion of “history of ail hitherto existing societies is history of class struggle”. Rather, he believed that conflict and cooperation is part of social life.

Roy was highly critical of Marx’s vision of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’. On the contrary, we believed that the real “conflict was between totalitarianism and democracy, between all-devouring collective ego-nation or class and the individual struggling for freedom”.

Roy strongly put faith in education. He believed that revolution through education was the most suitable method for changing the world for better.

Roy advocated a humanist interpretation of history in which the human will have importance as a determining factor in history. He argued that human will cannot be directly related to the laws of physical universe. Ideas, too, have an objective existence, and are governed by their own laws. The economic interpretation of history is deduced from a wrong interpretation of materialism.

Roy was also not happy with Marx’s economic interpretation of history. Roy held the view that biological development of Man in the early stages of his evolution was more dominant than his economic activities. The early activities and struggles of human beings, he said, revolved not around economics; but around finding means to subsistence.

Roy did not also agree with Marxism theory of surplus value. He, on the other hand, believed that surplus provided one of the bases for society’s progress.

Human nature

Marx had said that the Man in the process of his evolution and struggles with nature, changes his own nature; human nature, basically, is thus highly unstable.

Roy, on the other hand, argued that there is something in human nature that is enduring, and it is the basis of his obligations and rights. Roy tried to explain human nature with reference to anthropology, biology, and psychology. He accepted the possibilities of unlimited changes in human nature within the ambit of biological laws. According to Roy ‘to change is human nature’. The greatest significance of human being in nature is due to his rationality, the liberty of judgement.

Ethics

Roy pointed out to the woefully weak ethical foundation of Marxism. According to Roy, Marx neglected ethics. Roy pointed out that Marxian materialism wrongly disowns the humanist tradition and thereby divorces materialism from ethics. The contention of Marx that “from the scientific point of view this appeal to morality and justice does not help us an inch farther” was based, according to Roy, upon a false notion of science.

Roy was against the stand taken by Marx which makes the survival of the fittest as the basis of ethics. According to Marx there is no ultimate standard of ethics, since ethics is relative to class.

Roy pointed out that the subordination of Man to the forces of production did neutralize his autonomy and creativity. But, morality and ethics was not a product of the economic forces. Roy, here, presented the humanist ethics which values the sovereignty of the individual and his urge for freedom and justice. Roy saw these as enduring virtues of human existence.

He advocated that social organization should strive for the moral development of each individual – ´ the good individuals may form a good society; rational individuals constitute a rational society; but, free individuals alone can build a free society”. The only purpose of the society and the state is to provide maximum liberty to the individual.

Roy forged a relation between the means and ends. He said “It is very doubtful if a moral object can ever be attained by immoral means”.

The predictions

The prediction made by Marx that the contemporary society would get divided into anti-sectors did not come true.

Marx was totally off the mark when he predicted disappearance of middle-class in the society. Instead, the middle-class emerged as the powerful and forceful factor that holds the society together and influences the political, economical and social policies and programs of any sort of regime. The middle-class has grown stronger both in its numbers and in its influence.

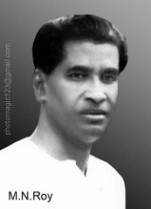

Relevance of MN Roy

Roy’s political philosophies are often criticized for being utopian and unrealistic. And , yet, even his critics concede that many of the political principles that Roy enunciates are relevant today.

His critics point out : Some of the ideas put forth by Roy are rather too idealistic or ethereal, even from the Humanist perspective. And some of the terms he employs are amorphous and imprecise. For instance; Roy talks of “spiritual needs” and “spiritual childhood” of human beings when he is arguing in favor of materialism. And, at the same time, as a materialist, he was opposed to the vain glorification of the so-called “spiritual” heritage of India.

His ideal of a party-less democracy also seems impractical. Further , the Freedom of association is one of cardinal virtues a democracy. Citizens with similar political ideas and programs are very likely to come together and cooperate with one another by forming political parties along with other non-party organizations. Therefore, the ideal of “party-less democracy” seems to be self-contradictory, impractical and unrealizable.

**

MN Roy was perhaps among the earliest few to realize the dangers of Marxism on one side and the inadequacies of Parliamentary Democracy, on the other. He recognized the need for a new kind of political structure based in a socio-economic philosophy that guarantees freedom of the individual. The People’ s Plan for Economic Development of India and the Draft Constitution of Free India prepared by Roy and his associates during 1944 and 1945 hold out some solutions to India’s current economic and political problems. His ideas in these regard are very relevant, today.

The cardinal principle of Roy’s scheme of things to come in Free India was the individual and his liberty. He envisaged a system of governance in which the individual citizen would exercise effective control over the people‘s representatives controlling the machinery of the state.

After rejecting both Communism and capitalism, Roy put forth a philosophy of decentralized Radical Democracy as an alternative to Parliamentary Democracy. He also rejected both the state ownership as well as unbridled capitalism as being destructive to democracy.

Roy, as early as in 1947, had foreseen the political degradation, corruption and the rot that would set in and erode democratic values of India. In his lecture on January 30, 1947, at Calcutta, Roy had said: “When political power is concentrated in the hands of a small community, you may have a façade of parliamentary democracy, but for all political purposes it will be a dictatorship, even if it may be paternal and benevolent.”

In his another lecture to the University Institute in Calcutta on February 5, 1950, Roy warned that the Parliamentary form of Democracy in India would breed corruption.

“The future of Indian democracy is not very bright, and that is not due to the evil intentions on the part of politicians, but rather the system of party politics. Perhaps in another Ten years, demagogy will vitiate political practice. The scramble for power will continue, breeding corruption, casteism and inefficiency. People engaged in politics cannot take a long view. Laying foundations is a long process for them; they want a short-cut. The short-cut to power is always to make greater promises than others, to promise things without the competence or even the intention to implement them.”

At the same time , he was cautious and conceded that it was too early for the Indian common men to understand the meaning and value of participatory democracy propagated by him because they were ’seeped in the feudal tradition of monarchic hierarchy as well as in the customs of a religious patriarchal society’

And, despite even after about sixty-seven years of democratic rule in India, Roy’s fears have not gone away. On the contrary, his prediction of doom has sadly turned out to be very true.

The system of Democracy that Roy advocated is more relevant today than ever. Although it is rather very late , his ideals of a working-democracy are worth consideration.

**

Roy had observed:

“the defects of a parliamentary democracy result from uncontrolled delegation of power. To make the democracy effective and functional , the real power must always vest in the people ; and there must be ways and means for the people to wield their power not once in a five years or periodically but on a day to basis” (New Humanism p.55)

He strongly believed that the greatest good of the greatest number can be attained only when members of the government are accountable in the first place to their respective constituencies He had built in safety measures like specifying their time-bound tasks in each constituency; fixing accountability on the elected representatives in fulfilling the tasks and promises ; and giving the citizens the power to re-call the erring elected members.

These issues are still debated today.

***

In the Draft Constitution that Roy proposed, the Indian State was to be organized on the basis of country-wide network of Peoples’ Committees having wide powers such as initiating legislations, expressing opinions on pending Bills, recalling representatives and referendum on important national issues.

Roy advanced the idea of a new social order based on direct participation of the people through People’s Committees and Gram Sabhas. Its culture would be based in minimum control and maximum scope for scientific and creative activities. The new society of India that Roy envisioned was a democratic, political, economic, as well as cultural, entity with the freedom of the individual as its core.

He believed that economic democracy would be suffocated if there is no political democracy. The truly democratic economic order , he believed, can be built around the principle of co-operation where there is also the participation of workers as co-owners

Roy, thus, envisaged formation of people’s local cooperative organizations as the nuclei of a new system of economy.

Jayaprakash Narayan did try to bring into practice some of the ideas of Roy regarding the de-centralized form of Democracy; and, ‘going back to the roots’. He of course got no opportunity. And, death was also premature. The Congress Government brought in half-hearted measures such as Panchayathi Raj; and, they lacked credibility and honesty of purpose. [Now, I believe, AAP is talking about of governance with Mohalla Samithi-s as basic units.]

Dr Rekha Saraswat, Editor of The Radical Humanist, (a magazine founded by Roy) writes eloquently:

We live in an age where production is sumptuous but distribution is partial; where science has conquered irrationality but religion is propagating myths and superstitions where technology has brought humanity closer but nationalism is instigating wars and terrorism. Philosophers and thinkers have contributed to the refinement of human knowledge; science and technology have given facilities of comfort and ease to human existence but frauds and deceptions have tried to spoil true human progress in all areas of the world’s living humanity.

In such a situation Roy’s principle of ethical-politics and rational-social morality appears to be the only solution for the salvation of human strife.

Writings of M N Roy

Roy was a prolific writer. He wrote many books edited, and contributed to several journals. He wrote books on a vast variety of subjects : Communism; politics; political philosophy; philosophy; Humanism; Radical Democracy; Religion; history; Sociology; economies; science besides Autobiographical notes. During his long career Roy edited numerous journals and regularly wrote articles on current and political affairs.

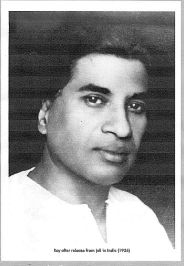

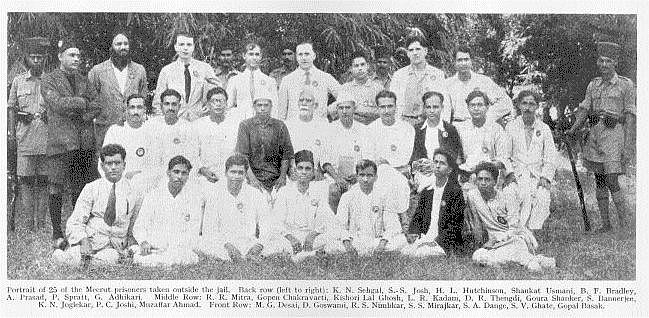

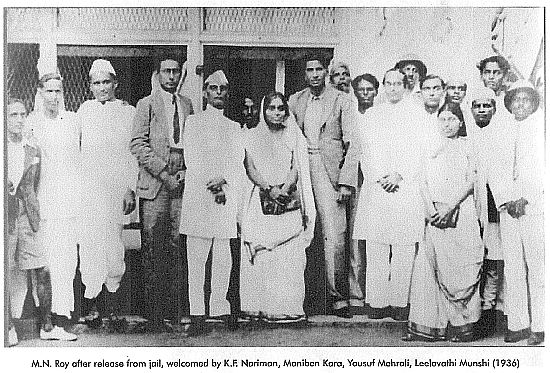

During the jail days, M.N. Roy produced extensively political, philosophical and social criticism. His systematic study of ‘the philosophical consequences of modern science’, in a way, was a re-examination and re-formulation of Marxism to which he had been committed since 1919.

The reflections, which Roy wrote down in jail, grew over a period of five years into nine thick volumes (approximately over 3000 lined foolscap-size pages).

Selected portions from the manuscript were published as separate books in the 1930s and the 1940s. The published books based on Roy’s Prison handwritten notebooks include Materialism(1934); Science and Superstition (1940); Heresies of the 20th century (1939); Fascism (1938);Historical Role of Islam (1939); Ideal of Indian womanhood (1941) ; Science and Philosophy(1947) and India’s Message (1950) . His monumental work tentatively entitled “The Philosophical consequences of Modern Science” is an outstanding contribution to the fields of philosophy and science. It is about his re-examination and re-formulation of Marxism to which he subscribed since 1919.

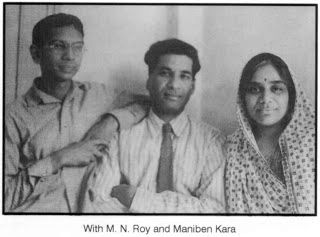

Four volumes of Selected Works of M. N. Roy, edited by Sibnarayan Ray, have been published by the Oxford University Press. Many of the writings of M. N. Roy such as Revolution and Counter-Revolution in China ; Beyond Communism; New Humanism – A Manifesto and Reason; Romanticism and Revolution. his books Scientific Politics (1942) along with New Orientation (1946) and Beyond Communism (1947) constitute the history of the development of radical humanism. His final ideas are, of course, contained in New Humanism.

For a list of MN Roy’s published writings please click here – Index on M N Roy

Please also check: M. N. Roy Books List

It is said; Roy’s ‘Prison Manuscripts’ have not so far been published in full; and are currently preserved in the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Archives in New Delhi.

7tt1.tif

Sources and References

Manabendra Nath Roy (1887—1954) by Ramendra Nath

M.N Roy’s Disagreements with the Marxism By Puja Mondal

- N. Roy and Marxism by A.P.S. Chouhan and Dinesh Kumar Singh

Indian Political Thinkers: Modern Indian Political Thought b y N. Jayapalan

Relevance of MN Roy – Dr Rekha Saraswat