[We will be trying to understand only a few concepts of Samkhya –Karika; and not discussing the entire text.)

O. The unfolding

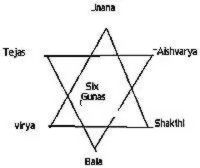

33.1. As mentioned earlier, Samyoga the proximity of the Purusha (consciousness) and the a-vyakta (undifferentiated un-manifest Prakrti) disturbs the Gunas, the dormant constituents of the a-vyakta. The three Gunas resting in a state of equilibrium turn restless, struggle among themselves for expression ; and, each strives for ascendency over the other two. That turbulence gives birth to the first stage of the evolution process.

[ However, it is not explained why such proximity should cause agitation among the Gunas]

33.2. It is said; the evolution process detailed in the Samkhya is twofold: one cosmic and the other individual.

Further, the outward process of the unfolding (sarga) is also meant to delineate the reverse process of absorption (apavarga). Samkhya considers evolution and absorption as processes that complement one other.

The evolution processes described in the Samkhya Karika are with particular reference to the individual.

33.3. The turbulence that takes place within the a-vyakta results in the Guna rajas gaining the ascendancy; the rajas then activates sattva. And, the two together overpower the inertia of the tamas; and set in motion the process of evolution.

P. The evolutes of Prakrti

Buddhi

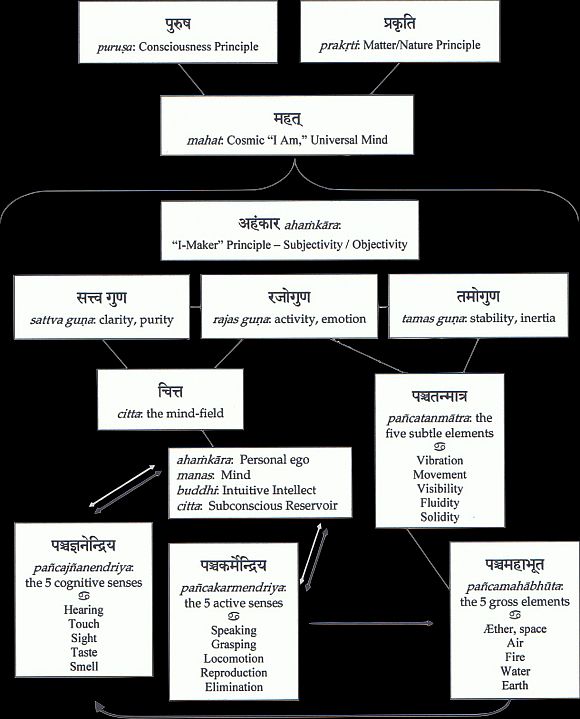

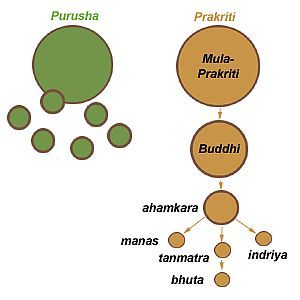

34.1. The first to evolve out of this churning of the Gunas is Buddhi (the intellect) or Mahat (the great one).The latter term is usually employed in the context of cosmic evolution, while the term Buddhi is used with reference to the individual. But, both (Mahat and Buddhi) represent the principle of intellect or discrimination buddhi-tattva.

34.2. Mahat or Buddhi is the first principle which the Purusha sees or witnesses; and, is the first phenomenon to emerge out of the undifferentiated ground of the un-manifest (a-vyakta) and to cross the threshold into manifestation (vyakta).

Buddhi represents the first phase of evolution, and is therefore described as the primacy phenomenon. For this reason, Buddhi or Mahat is otherwise called ‘the seed of the material world’ (prapancha-bija).

34.3. Buddhi is said to be very subtle, transparent, not extended in space and dominantly sattva in its nature. Buddhi is a unique faculty of human beings. It is man’s instrument for exercise of judgment and discrimination (viveka). It not only ‘knows’ but also ‘works’; meaning, it is awareness as well as the will to be active. For that reason, according to Samkhya-karika, the becoming of man is determined by his fundamental strivings which are guided by the Buddhi. In other words, the man’s place in this world depends upon his inclinations (Gunas) as directed by the Buddhi.

34.4. But, Buddhi, an evolute of Prakrti, is not consciousness; only the Purusha is consciousness. Buddhi is an effective instrument of knowledge or cognition.

Buddhi, the first evolute and the instrument of discretion, is the nearest to Purusha, of all the evolutes of the a-vyakta. It, in a way, compliments the functioning of the Purusha. If Purusha provides consciousness which makes evolution possible, the Buddhi provides requisite knowledge to attain liberation by isolating Purusha from everything else; by showing, at each stage, that Purusha (consciousness) is indeed different from Prakrti (matter) and its evolutes. The function of Buddhi is Adyavasaya or certainty leading to action. The Buddhi instructs the individual that he or she is not prakrti or any of its evolutes; but is essentially the pure consciousness itself. The Buddhi spurs the man to action. The Buddhi is, thus, the faculty that guides and bestows man the true understanding which liberates him. It is the paucity of this discriminating knowledge (viveka) that subjects the man to bondage and suffering.

[ Samkhya Karika (26) names the five sense organs [Bhuddhi Indriyas- because they are the means or the Dvara of perceiving sound etc by the internal organ] and five organs of action (Karmendriya) namely , voice , hand, foot , organ of excretion and organ of generation. And the Eleventh organ is the mind

buddhi-indriyaṇi cakṣuḥ srotra-ghrāṇa-rasana-tvak-ākhyāni | vāk-pāṇi-pāda-pāyū-upastāḥ karma-indriyāṇi-āhuḥ ||

In the Samkhya system , the senses , the sense-organs, the sense-objects and sense-perceptions are all discussed within the overall framework of the notion of Purusha and Prakrti ; the three Gunas; the levels of gross (sthula) and subtle (sukshma) ; as also the levels of the interplay of Manas, Ahamkara and Buddhi.

The last three (Buddhi, Manas and Ahamkara) constitute the inner organs (Antha-karana) .They are the powers that open and close the gates; monitor, control and register whatever is carried through. The body-mind complex of human system is active (kartar) through the ‘five organs of action’ (Karmendriya) and receptive through the ‘five organs of perception’ (Jnanendriya) .

These two sets of five each are the vehicles of alertness and responses. These faculties work outward (bahyendriya) and are akin to gates or doors (Dvara) ; while mind (Manas) and the ego ( sense of “I’) , intellect, judgement (Buddhi ) are the door-keepers. Since the mind (Manas) operates directly with the ten faculties (Bahyendra) it is considered as the eleventh (Ekadasha) and is called the ‘inner-sense’ (Antar –indriya).

Among the eleven organs of perception and action, mind is said to have the nature of both. Because, the organs of sight, speech, hearing etc function within the limitations of their assigned tasks; but are governed by the mind, which is the faculty that judges and determines . The organ of perception perceives an object as such , no doubt; but , it is the mind that identifies and determines : ‘it is an object’; ‘ it is of this nature’ or ‘it is not of this nature’ etc.

It is the mind (Buddhi) which continuously identifies, classifies and determines the objects it perceives. In the process, it is said, the mind keeps transforming itself into the shapes of the objects of which it becomes aware. Its subtle substance takes on the colours, forms of everything that is presented to it by the senses m by the memory and emotions. Yet, it has also the capability to calm and still the senses as also itself, like a jewel in a pond, by the power of the Yoga.]

(source : https://universaltheosophy.com/legacy/movements/movements-sankhya-2/ )

Ahamkara

35.1. Arising out of Buddhi and projected from it is Ahamkara the self-identity, bringing along with it notions of “I-ness” and “mine”. Ahamkara breeds ‘self-assertion’ (abhimana) or self-love; and even self-conceit or self-pity. The Ahamkara is the specific expression – ‘me’ and ‘mine’- of the general feeling of self.

35.2. It is the Ahamkara that sets apart the individual from rest of the world, erecting enclosures around the person. It makes the person think and to interpret everything and every notion in terms of I and the rest. All thoughts, action and speech of an individual are in terms of his or her sense of Ahamkara. It is the foundation of one’s actions of every sort.

35.3. Ahamkara pervades and influences all human experiences; it even colours the Buddhi; and is very scarcely silenced. If Buddhi is predominantly sattva, the Ahamkara is predominantly rajasa. It is dynamic in nature; and pervades all human experiences including mind, senses etc. Ahamkara is functionally an urge for self-preservation and self-perpetuation amidst series of environment changes and fluctuations. The Samkhya therefore regards Ahamkara as an ongoing ceaseless process (vritti) and not as a substance.

Group of sixteen

36.1. In the next stage of evolution, from out of the Ahamkara there emanates ‘a group of sixteen’ elements; in two sets: of eleven and five. Those sixteen elements (tattvas) are nothing but the various transformations (vaikruta) of Ahamkara. This means, the evolution stream which till then was vertical (avyakta — buddhi — Ahamkara) turns horizontal at the stage of Ahamkara.

36.2. The first set (of eleven) comprises manas (mind), five buddhi-indriyas (five senses of perception: hearing, touching, seeing, tasting and smelling) and five karma- indriyas (five organs of action or rather the functioning of these five organs: speech, apprehension, locomotion, excretion and procreation). The set of eleven represents the first stage of man’s contact with the world. It is characterized as sattvic-ahamkara; meaning its components are predominantly of sattva nature.

36.3. The Manas (mind) the first among the group of sixteen, according to Karika, is described as samkalpa, meaning it is constructive, or analytical or explicit. The Manas is concerned with determined perceptions .It arranges impulses or sensations coming from the senses and organs of action; and is a coordinator of various streams of thoughts, sensations and emotions. The manas acts as a bridge between the internal and external worlds; and, it is said to be involved mainly with a person’s waking experiences.

Antahkarana

37.1. The triad of manas, buddhi and Ahamkara form the antahkarana, the internal organ or instrument, which in other words is a psychological field that is subjective and individualized. It is the threshold area which connects man’s inner world to external world (bahya – karana).

[Yoga reduces the three components of antahkarana into one Chitta the seat of awareness.]

37.2. Though the antahkarana is formed by the evolutes of un-intelligent Prakriti, its constituent psychological categories are predominantly Sattva in nature. The antahkarana therefore reflects the intelligence of the Purusha, and appears as if it is a conscious entity.

38.1. These thirteen (anthahkarana plus five buddhi-indriyas plus five karma – indriyas) together form the essential psycho-physical instrument which enables Man to know, understand the world and himself. This set of thirteen is also a prelude to the emergence of the physical world.

38.2. In the Samkhya scheme of evolution, the physical world appears only after the basic constituents of mind and the sense and the functioning of sense organs are put in place.

Tanmatras and Bhuta

39.1. The ten senses or indriyas that follow are external (bahya) instruments (karana).

The second set of five (out of the group of sixteen mentioned above) consists the five subtle elements (tanmatras) : shabda, sparsha , rupa, rasa and gandha (elemental sound, touch, form, taste and smell). This set of five is characterized by rajasa, the Guna of action. The function of the rajasa Ahamkara is to motivate two other Gunas to be creative.

39.2. From out of the second set consisting five subtle elements, emerges Bhutas a set of five gross elements, the basic elements of nature: earth, water, fire, air and space (pancha-bhuta) leading to the gross or external world. This set of five gross elements is said to betamasa–ahankara, meaning they are the forms of Ahamkara characterized by predominance of the Guna tamas. Because of the predominance of tamas, the Bhutas or material elements are incapable of reflecting intelligence. They are therefore called insentient matter.

39.3. The gross elements are produced by various combinations of subtle elements. To illustrate:

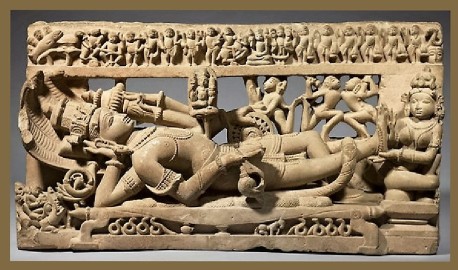

First to evolve is the tanmatra that is the essence of sound (sabda), which in turn produces akasha the space element. Therefore, the akasha element contains the quality of sabda perceived by the ear.

Shabda and sparsha together produce marut (air); the air element contains the attributes of sound and touch, although touch is the special quality of air and is sensed by the skin.

The teja (fire) element is derived from the essence of colour (rupa tanmatra). It combines the qualities of sound, touch, and co]or, and its special property sight as perceived by the eyes.

Shabda, sparsha, rupa and rasa together form apha (water). The water element has all the three preceding qualities–sound, touch, and colour– as well as its special quality taste, as sensed by the tongue.

All five elements combine to produce kshiti (the earth). The five gross elements combine in different ways to form all gross objects of the world that are perceivable. This grossest element kshiti (the earth) contains all of the four previous qualities.

| Akasha | Sabda | ||||

| Vayu | Sabda | Sparsha | |||

| Agni | Sabda | Sparsha | Rupa | ||

| Apah | Sabda | Sparsha | Rupa | Rasa | |

| Prithvi | Sabda | Sparsha | Rupa | Rasa | Gandha |

[Note: Earth means earthly properties, similarly wind means properties of the wind, sky means the ever pervading space and fire means the energy (of creation and destruction) and water means the organic properties]

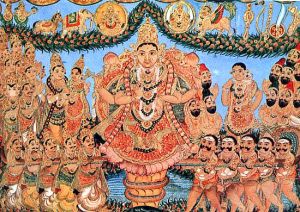

Q. Twenty-four tattvas

40.1. Thus, buddhi, Ahamkara, the group of sixteen and the five gross elements together make the twenty-three tattvas the basic components of the Samkhya karika. In addition, the text counts a-vyakta the un-manifest Prakrti as one of the tattvas; thus bringing up the total of the tattvas to twenty-four.

40.2. Thus, the objective world according to Samkhya karika is made of twenty-four tattvas each composed of varying degrees of the three Gunas: sattva, rajas and tamas. The term tattva is comprised of two words tat (that) and tva (you) meaning ‘thatness’ or the nature of a thing. The Purusha (consciousness) is not a thing and is not treated as a tattva; Purusha is different from everything else. This is what distinguishes the karika version of Samkhya from the older atheistic version; from the version of Panchashikha; as also from the later versions influenced by the Vedanta.

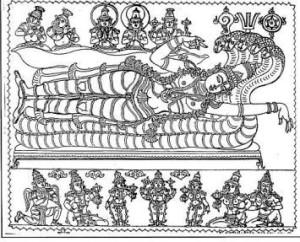

[To summarize; the first tattva to emerge from avyakta is buddhi (intellect), closely followed by Ahamkara (sense-of-self) and manas the mind or cognition. These three collectively referred to as the inner organ (antahkarana) is predominantly of sattva Guna; and determine how the world is perceived.

That is followed by the five sense organs and the five organs of action. These possess the combined qualities of sattva and rajas; and provide conditions necessary for human functions. At the same stage, the Guna rajas combines with tamas to produce five subtle elements tanmatras (sound, touch, form, taste, smell). This set of subtle elements, in turn generates five gross elements (space, wind, fire, water, earth).

These twenty-three, along with a-vyakta form twenty-four tattvas or basic components of matter, as per Samkhya karika. Since they are all evolutes of Prakrti, they are not-conscious or intelligent. They are the objects of experience of the Purusha, the consciousness.

Please see the figure at the bottom of the post.]

R . The scheme

41.1. The evolution as projected in the Samkhya –Karika systematically proceeds, in stages, from the extremely subtle matter in its un-manifest state (a-vyakta) down to the grossest physical element. The ‘group of eleven’, and more particularly the antahkarana which is a psychological field formed by the triad of the subtle forms of intellect, mind and ego is the threshold area which connects man’s inner world to external world (bahya -karana). In the Samkhya scheme of evolution, “physical world” appears only after the basic constituents of mind and the sense and the functioning of sense organs are put in place.

41.2. In a way, the Samkhya scheme is an inversion of the western model where the man and matter are just created. In contrast, what the Samkhya describes is not an act of creation but a process (vritti) of evolution originating from the most subtle towards the gross.

Samkhya regards the processes of evolution and absorption as complimentary to one another. The Samkhya scheme of absorption is therefore exactly the reverse of its evolution process. Samkhya also believes that just as that which had not existed before can never be brought into existence, that which exists cannot be entirely destroyed, either. Following these principles, the Samkhya projects its scheme of absorption. According to which, at the time of dissolution of the world, the reverse process sets into motion with each effect collapsing back into its cause; the gross physical elements broking down into particles; the particles into atoms; the atoms dissolving into finer energies which in turn merging into extremely fine energies; and ultimately the whole of existences dissolving back into the subtlest un-manifest Prakrti, the a-vyakta. Thus, Prakrti even when all its evolutes are withdrawn remains unaffected; and is eternal.

S. Enumeration

42.1. Some scholars say that the whole of the Samkhya karika can be viewed as a systematic enumeration of its twenty-four tattvas or basic elements which compose the man and his world. Such enumeration is in keeping with the meaning assigned to the term Samkhya suggesting reckoning, summing up or enumeration.

42.2. However, Samkhya Karika is not mere enumeration of categories; it is much more that. It is a method of reasoning, analysis and enquiry into the very core of man’s existence and his identity. The term Samkhya also refers to an individual who has attained true knowledge. Whatever be the meaning assigned to the term, Samkhya is one of the most important Schools of philosophy.

42.3. The method of enumerating their basic principles is not unique to Samkhya .The enumeration procedures seemed to be quite well accepted in the ancient times; and a number of ancient texts followed the enumeration method. For instance, the parts of man are enumerated and correlated with parts of the universe in Rig Veda (10.90) and in Taittiriya Upanishad (1.7).The dialogue that takes place between Yajnavalkya and his wife Maitreyi as many as seventeen of the twenty-five tattvas of the later Samkhya are enumerated (Br. Up . 4.5.12)

42.4. The Samkhya enumeration system is more through, purposeful and logical. The seemingly elaborate system of Samkhya enumeration of the elements of existence (tattvas) is a deliberate effort to systematically reduce the countless manifestations into comprehensible categories. It attempts to trace the stages of development of the categories of existence in their ordered phases of their evolution, consistent with a well thought out scheme (tattva-ntara-parinama).It proceeds from the most subtle to the most gross; and arranges the sets cogently in successive stages of their dependence in order to delineate their mutual relationships.

For instance; at the fundamental level the translucent pure –consciousness Purusha is neither generated nor generating; while the extremely subtle mula-prakriti is un-generated but generating. Buddhi, Ahamkara and the tanmatras are both generated and generating. The psychological fields manas, the buddhi-indriyas, karmendriyas, as also the elemental mahabhutas are generated and do not generate anything in turn, thus closing the onward flow of the evolution. The reverse process of absorption or dissolution starts with the gross elements at the outer periphery of existence; each stage collapsing back in to its source; and ultimately all dissolving into the primal source the mula-prakrti.

The Samkhya concept of liberation (of which we shall talk a little later) is described in terms of the involution or the absorption process of the manifest world. It is the reverse of the evolution process where the individual in quest of his true identity traces his way back to the origin viz presence of the pure-consciousness.

T. Purusha-Prakrti

43.1. The relation or rather the non-relation between the Purusha and Prakrti as depicted in the Samkhya Karika is of a very peculiar sort. Purusha never comes in contact with Prakrti; he is ever separate and aloof. Yet, Purusha’s proximity to the a-vyakta disturbs or influences the Gunas; and triggers the process of evolution.

43.2. The two are totally different realities of existence. Purusha is consciousness, passive and does nothing but see rather disinterestedly. Avyakta Prakrti, which is witnessed, is the root cause of the world containing in a potential form infinite possibilities of world and all its characteristics. But, Prakrti does not possess consciousness; it is inert and intelligible.

How Purusha and Prakrti were first formed or came into existence is not explained. But they together form the basis of all existence. Although the manifestation of Prakrti depends on Purusha, the Purusha has no role in creating Prakrti or giving it its shape and appearance.

Because Purusha is perfect and unchanging complete unto itself, there is no reason for it to take active role in the creation of Prakrti. Thus the concept of Purusha is entirely unlike the idea of God the creator of the world.

43.3. Samkhya karika says that Purusha and Prakrti (though unrelated) need one another .Prakrti requires the presence of Purusha in order to manifest and to be known; and Purusha requires the help of Prakrti in order to distinguish itself from Prakrti and thereby realize liberation. The manifest world (Prakrti) serves its own purpose by serving the purpose of Purusha. Samkhya karika compares the samyoga the association of Purusha and Prakrti to the teaming of a blind person with a lame person. The blind being Prakrti who can move but cannot see and is not intelligent (not conscious); the lame being Purusha who is intelligent and can see, but cannot move (SK: 21).

Purushasya darshanaartham kaivalyaartham tathaa pradhanasya | Pangva-andhavat ubhyorapi samyogh stat-kritah sargah ||

[ Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, (Indian Philosophy, Vol. II, p.326) writes :”If we admit the Samkhya view of prakriti and its complete independence of purusa, then it will be impossible to account for the evolution of prakrti. We do not know how latent potentialities become fruitful without any consciousness to direct them.,]

[The main problem appears to be the polarity between Purusha and Prakrti; Purusha is so indifferent and Prakrti so mechanical. The simile to explain their interaction as that of a blind man of good foot carrying a cripple of good eye is not a great analogy. It is rather brittle and should not be pressed too hard. Because, both the blind and lame are intelligent; whereas Prakrti is not. The simile would fit better if the lame had no desire to go anywhere and he says nothing and does nothing; while the blind person has no mind at all. Clearly in such a case they would not be able to cooperate; yet Samkhya somehow forges an association between Purusha and Prakrti.]

43.4. Samkhya seeks to understand the world and man’s place in it from the perspective of consciousness. Consciousness is the reason why there is a manifest world, although the Purusha adds nothing to the world. The Purusha only witnesses the world. Since its nature is to witness, it sees the world as an instrument for its own purpose and ends.

43.4. The world is that which is witnessed. Prakrti like a painting acquires meaning and comes alive only when it is viewed by a viewer. The painting is for the enjoyment of the viewer. Purusha is the seer and Prakrti is that which is seen; and Prakrti (matter) is meant for the enjoyment of the conscious Purusha. The world exists for the sake of Purusha. (Purushartha).

43.5. To start with, the manifest world appears because of the presence of Purusha. Further, all the objects of the world–including the mind, senses, and intellect—in in themselves unconscious — appear to be alive, intelligent, possessed of consciousness only because they are illuminated by the Purusha.

Purusha (consciousness) which has no form appears through objects, which by themselves do not posses consciousness. The objects appear as if they are possessed of consciousness; giving a false impression that consciousness is their nature. In other words, the world appears as conscious, which it is not. Similarly, the conscious appearing object is mistaken for Purusha; the Purusha appears as what it is not.

There is a perpetual dilemma here .The world is real but can manifest only because Purusha the pure consciousness is associated with it. But Purusha can realize its true nature only when it separates itself from Prakrti.

44.1. Since Purusha has no form it can be grasped or understood only in terms of what it witnesses. Samkhya therefore describes everything that appears to Purusha; and eventually discards all that it described. It then says Purusha is radically distinct from everything it witnesses and everything that was described.

The seer is not the seen. This distinction is crucial to Samkhya. The Samkhya follows a method of elimination; it seeks to understand Purusha by identifying what Purusha -is –not and rejecting all that. When Purusha is thus isolated from everything else, one understands that the ultimate ground of human existence is none other than Purusha itself.

U. Dualism in Samkhya karika

45.1. The fundamental dualism in Samkhya centres on the distinction between individual consciousnesses on one hand and the not-conscious world on the other. It is between Purusha and Prakrti in its manifest (vyakta) and un-manifest (a-vyakta) forms. The duality is between Prakrti the creative factors in creation (becoming) and Purusha (being).

45.2. Purusha is not characterized as made of the three Gunas. Purusha is beyond Gunas; it is subjective, specific, conscious and non-productive. In contrast, the Gunas are the expression of creative factors of Prakrti. In a way of speaking, the dualism in Samkhya could be between the real doers Gunas (becoming) and the passive Purusha (being).

45.3. The Samkhya dualism is not that of body and mind, or a dualism of thought and extension. All such dualisms are included and comprehended on the side of Prakrti, the not- conscious world. Because, according to Samkhya, the mind, the self-awareness of man is all evolutes emerging out of the mula-prarti. Similarly, all of man’s emotions and strivings and urges are also comprehended on the side of the mula-prakrti.

[Before going further some explanations appear necessary, here:

45.4. Samkhya Karika’s treatment of the subject is from the perspective of the individual consciousness. It does not speak of god or cosmic soul. The Purusha and Prakrti are ever separate and do not come together. There is no manifestation of world without Purusha; yet, Purusha exists apart from the world which is not-conscious. The dualism of the Karika is between consciousness and that which is not conscious.

45.5. As regards the plurality of Purushas, the Samkhya Karika underscores its assertion that man or the world is not derived from an all encompassing cosmic source; but each evolves following its own natural laws (svabhava). The Purusha of the Karika is individual; but not personal. The basic concern of the Samkhya Karika is individual suffering and the liberation of the individual. It is not concerned with abstract concepts of suffering or universal spirit. You might recall that the Buddha who had his initial training also pursued similar approach; and refused to get into discussions on cosmos or the cosmic soul. His approach too was highly individualized.

One might perhaps appreciate the concept of plurality of Purushas, if you treat it as jiva of Vedanta or Jainism .The Vedanta Schools however brought the jivas under the umbrella of Brahman or Parama-purusha.

45.6. Again, the question of god too is linked to Karika’s major concern: salvation from suffering. Karika regards the discriminative knowledge alone as the means of salvation. The salvation according to Karika is the realization that Purusha (consciousness) is distinct and separate from Prakrti (materiality). Isvara, god, in case he exists, according to Karika scheme of things, would be a part of Prakrti and therefore not-intelligent. And ,in which case the presence of god, becomes irrelevant to Karika.

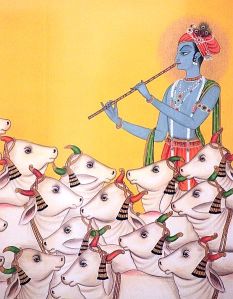

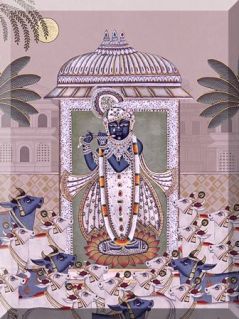

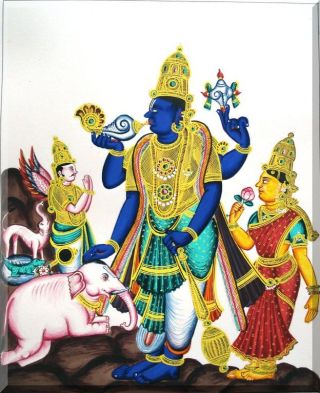

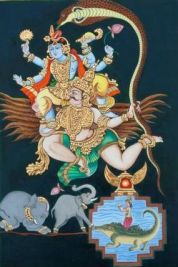

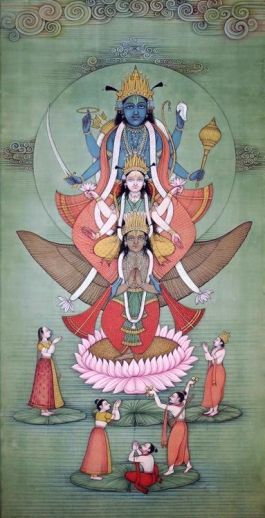

The Karika in fact refers to Vedic gods (SK 53 and 54) and makes no attempt to deny their existence; but they are treated as part of Prakrti. And, by implication those gods too are in need of salvation. In short, the question of salvation is viewed in Karika from non-theistic perspective. Whether or not a god exists makes little difference.

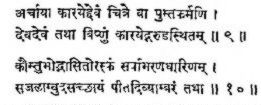

aṣṭa vikalpaḥ daivaḥ tairyagyonaḥ ca pañcadhā bhavati | mānuṣakaḥ ca eka vidhaḥ samasataḥ bhautikaḥ sargaḥ ||SK 53 ||

ūrdhvaṃ sattva-viśālaḥ tamo-viśālaḥ ca mūlataḥ sargaḥ | madhye rajo-viśālaḥ brahmādi stamba-prayaṅtaḥ ||SK 54 ||

The later Samkhya, of course, reconciled with the orthodox systems by accepting a God. Yoga too was theistic.]

V . Reverse process of release

46.1. Consciousness, ego and mind constitute the inner world of a human being (Samyogi purusha). Human contact (samyoga) with the material world of appearances, the contact between being and becoming is the real stuff of the world. The Man develops natural inclinations of attachment and involvement in the world that surrounds him. He nurtures clinging to certain urges; and he also dreads isolation. These are the foundations for all his actions. These are also his problems, aspirations, anxiety and frustrations of life.

The Samkhya believes that clinging to the world of appearances leads to suffering. It asks Man to detach from excessive involvements, to exercise control over senses, to discipline the mind and to move away from false identifications.

Samkhya compares the world to a dancing girl who withdraws when she finds no one is paying attention to her. When we look beyond the world, it will go away. This happens with the individuals as they separate themselves from hopes, fears, desires and passions, renouncing the Guna aspects of the intellect in order to realize their true identity as pure consciousness.

46.2. The Samkhya prescription for removal of suffering is the way of knowledge, the way of right understanding: ‘effective discrimination’ vijanana which separates pristine consciousness form everything that is not consciousness. It instructs that Prakrti is distinct from Purusha which has always been pure and free; and it is only the non- conscious Prakrti that is bound and strives for release.

Samkhya teaches that we should look beyond our personal affinities with Prakrti and realize the timeless unchanging nature of our true self, which resides beyond Prakrti as Purusha the pure consciousness. This realization can be understood as the reverse process of evolution back into the Purusha.

46.3. The Samkhya puts forward the premise, that the translucent consciousness adds nothing to the world ; and it can therefore be understood only in terms of what it witnesses: the un-manifest and manifest world viz, everything that is not consciousness. Following this, Samkhya enumerates all components of the un-manifest and manifest world; and suggests a process of enquiry guided by Buddhi, the faculty of discrimination (viveka), segregating everything that is not conscious in an attempt to view Purusha the consciousness in its isolation. Finally, he realizes Prakrti is distinct from Purusha. It is a state of realization (apavarga) that consciousness is ever pure and free; and consciousness is not matter.“No one is bound, no one is released…only prakriti in its various forms is bound and released” (SK .62).

The kaivalya isolation that Samkhya speaks about is not shuttered retreat from the world but is a way of being in the world sans entangled with Prakrti. The Buddhi which earlier was confused with wrong identities is now clear like a dust-free mirror reflecting the light of Purusha.

47.1. The practical method that Samkhya advocates is involution, a sort of returning to the roots of one’s existence; or returning to the origin or reversing the process of birth (prati- prasava). It is a systematic regression or an attempt to reverse the process of evolution; it is the opposite of spreading out (pra-pancha); leading back to the original state.

47.2. The Samkhya method of enquiry could therefore be described as an individual’s quest for his true identity ; a journey deep into the very core of his existence guided by Buddhi (viveka) ; travelling from the gross outer peripheries of his being into his subtlest inner core; going past the body, mind, senses, urges , etc ; shredding away every identity , every emotion and every thought ; all along the way, at each stage, rejecting what is not-consciousness and stepping into the next inner zone which is more subtle than the previous one; until he sheds away every aspect of Prakrti . It is also a method of giving up all identities. Once he finds Prakrti is distinct from Purusha he realizes the ultimate condition of “otherness”, freedom and isolation which is consciousness, Purusha in itself.

47.3. The relevance of the enumeration of the categories in Samkhya could be viewed in this context of involution. The hierarchical inversion begins with the elements of the body; progressively leading to the avyakata the un-manifest Prakrti which gets to see the Purusha the pure consciousness. To put it in another way, the evolution commences with Purusha seeing the avyakta; and, the cycle ends with the avyaktha seeing the Purusha; the seer becomes the seen. The un-differentiate Prakrti sees the un-differentiated consciousness. The reversal is complete. Yet, Purusha and Prakrti stay apart; there is no suggestion of the union of the two.

48.1. Samkhya ideology of reversing the normal trend of human existence in the world and attaining the condition of isolation or kaivalya provided the frame work for other spiritual persuasion, such as Yoga, Sri Vidya and other forms of Tantra.

It might perhaps help to understand better if one follows the Sri Chakra model of creation and absorption. In the Sri Vidya tradition, the aspirant regards his body as Sri Chakra wherein the innermost core of man is encased within a nine-fold fort of matter, senses, emotions, thoughts etc. He, following the samhara-krama the absorption method, proceeds from the outer periphery wall (body) to the innermost Bindu (consciousness) in an ascent through various levels of psychic states. As he proceeds inward from the outermost enclosure the devotee’s thoughts are gradually refined; and the association of ideas is gradually freed from the constraints of conventional reality.

Bindu the dimension-less point at the centre of the Chakra, just as the avyakta of Samkhya, represents not only the origin but also the ultimate end of all existence

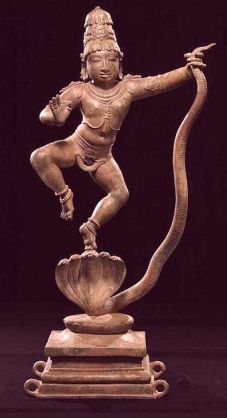

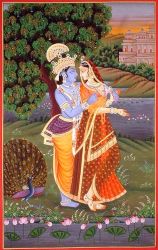

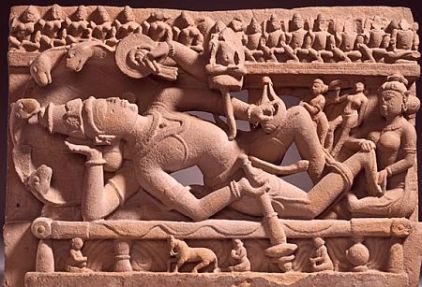

48.2. The Tantra too followed the hierarchical inversion of the twenty-four principles of Samkhya, but was not happy with Purusha and Prakrti being kept perpetually separate. It aimed to obliterate the subject-object duality; fuse the seer and the seen into one; and realize that unity in the Bindu symbolized as Ardhanarishwara the united Shakthi and Shiva. The Tantra improved upon Samkhya’s twenty-four principle- categorization by adding another twelve to render the dualistic universe into a unity.

48.3. The Yoga Sadhana too is patterned after the reversal of the Samkhya model of evolution. In the Yoga Sadhana, the yogi draws his energy from the root-chakra (muladhara) the earth element up to vishuddhi chakra the element of akasha space. Once at the vishuddha the five elements are purified, the prajna ascendants to ajna which is the collective frame of reference for manas the mind. The four chakras rising from the ajna correspond to the Samkhya tattvas of manas (Chandra chakra), Ahamkara (Surya chakra) , buddhi (Agni chakra) and avyakta prakrti (Sahasra chakra).In Yoga, the seer, seeing and the sight all dissolve into one.

49.1. The ultimate ground of human existence, according to Samkhya is Purusha pure-consciousness itself. One dwells in pure translucent consciousness, a kind of emptiness which transcends everything in the manifest and un-manifest world. The realization that one’s essential nature is consciousness: pure and free, relives one of all bondage and suffering. And, that is the supreme ambition of Isvarakrishna’s Samkhya karika.

Verily, therefore, the Self is neither bounded nor emancipated; No one is bound, no one is released. It is Prakrti alone, abiding in myriad forms that is bounded and released.

tasmāt na badhyate-asau na mucyate na api saṃsarati kaścit |

saṃsarati badhyate mucyate ca nānāśrayā prakṛtiḥ |

तस्मान्न बध्यतेऽद्धा न मुच्यते नापि संसरति कश्चित्।

संसरति बध्यते मुच्यते च नानाश्रया प्रकृतिः॥ ६२॥

(Samkhya karika: 62)

Next: Samkhya – Vedanta and Buddhism

References and Sources

Early Indian Thought by Prof.SK Ramachandra Rao

Classical Samkhya by Gerald James Larson

Samkhya Karika by Swami Virupakshananada

The Samkhya Karika

http://theosophytrust.org/tlodocs/SankhyaKarika.htm

http://www.archive.org/stream/svuorientaljourn015488mbp/svuorientaljourn015488mbp_djvu.txt

http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m09/m09050.htm

http://www.archive.org/stream/svuorientaljourn015488mbp/svuorientaljourn015488mbp_djvu.txthttp://www.hinduwebsite.com/sacredscripts/hinduism/philo/ch07.asp

–

–

–

–

V

V

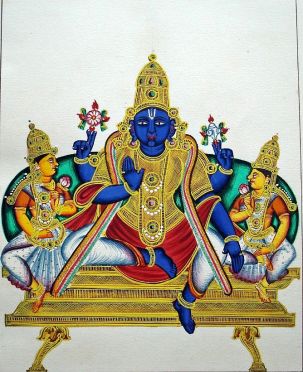

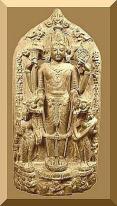

P

P

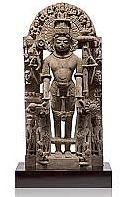

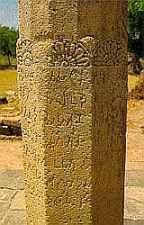

Devadevasa Va[sude]vasa Garudadhvajo ayam

Devadevasa Va[sude]vasa Garudadhvajo ayam

]

]