Asya Vamasya sukta forms section 164 in Book 1 of Rig Veda, and, it consists 52 hymns. It is dedicated to several deities; and is composed in different meters.

The author’s name is Dhirgatamas-Auchatya (दीर्घतमस्– उचथ्य) *; so, says the text at the beginning of this section as codified by Sri Sayanacharya, who lived in the 15th century as a minister in the Vijayanagar kingdom. His compilation and interpretation are the definitive and authoritative text-sources for most of the later translations. Even the recent translation and commentary by Swami Amritananda is based upon Sri Sayana’s Bashya. *[At times, he is also called Dhirgatamas-Mamateya-ढीर्गतमस् ममतेय ]

Dr. Kunhan Raja’s translation is based upon these two commentaries.

The Text is assigned its title using its commencing words

अस्य–वामस्य–पलितस्य–होतुस्तस्य–भ्राता–मध्यमो–अस्त्यश्नः॥तृतीयो–भ्राता– घृतपृष्ठो– अस्यात्रापश्यं विश्पतिं –सप्तपुत्रम् ॥१॥

asya vamasya palitasya hotus tasya bhrata madhyamo asty asnah trtiyo bhrata ghrtaprsAo asyatrapasyam vispatim saptaputram ॥१॥

Asya Yamasya Hymn: Dr C Kunhan Raja: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet Archive

Dr. Kunhan Raja explains:

On the whole, Dhirgatamas and his real inspired vision had a very great role in shaping Indian philosophy. His commendable knowledge in spirituality, and his extreme talent in poetry; and his inspired gift of vision stand unparalleled even to this day. No doubt that is why he is confident that none other than a wise poet can even hope to interpret his poems. To date, none has been able to fully decode his poems; at least the Asya vaamasya poem (RV 1.164).

Even his Ashvamedha poem is one of a kind; – perhaps a pun (स्लेश–Slesha), a satire of a ritual. His poems on Ribhus (ऋभु,) are another masterpiece. Even his metaphor poem on the horse-sun is much exquisite and unparalleled in its beauty.

[ Ribhu (ऋभु) in Sanskrit, broadly means Skilful, clever, prudent (as an epithet of Indra, Agni, Aditya) ऋभुमृभुक्षणो रयिम् (ṛbhum ṛbhukṣaṇo rayim) Rigveda 4.37. In early stages of the Vedic literature, it referred to Sun- deity.]

Now; let us commence with the famous hymns presented in the text Asya Vamasya Sukta. Please also refer to its translation and commentary by Dr. Kunhan Raja.

Verse 1

The poet starts with the mention of “a beloved invoker grown grey, with his two brothers, who is the Lord, and father of seven children” (verse 1).

अस्य । वामस्य । पृषतस्य । होतुः । तस्य॑ । भ्राता । मध्यमः । अस्ति । अशनः | ततीयः । श्रातं । धृतऽपुष्ठः । अस्य॒ । अत्रं । अपर्यम् । विदपतिम् । स्तऽपुत्रम् ॥

Of this beloved invoker, grown grey — of him there is the middle brother, the all-pervading; his third brother is the one who bears ghee on his back. In them I saw the Lord of the People with seven sons.

The poem concludes with a prayer to “the swift-moving divine bird, the majestic bird (Sun), producer of water, which gives life to the herbs; he who brings happiness with timely rains,” for protection, (verse 52).

दिव्यम् । सुऽपर्णम् । वाय॒सम् । बृहन्तम् । अपाम् । ग्मम् । ददतम् । ओष॑धीनाम् । अभीपतः । वृष्टिऽभिः । त॒पै्यन्तम् । सरसन्तम् । अवसे | जोहवीमि ॥ १.१६४.५२

The divine bird, the great bird, the child of waters, of herbs, worthy to be seen, who brings satisfaction with rams in the rainy season, that Sarasvati I invoke again and again for protection.

Dr. Raja remarks:

The one supports the six regions; the one stands upright and supports three mothers and three fathers: those who have eyes can see this underlying truth.

I do not find in this philosophical hymn merely some anticipations of philosophy. These are not loose ends of broken threads.

One can trace a continuous stream of thoughts. I see a beginning and a conclusion in the poem, consistent with each other, and with a continuity in the current of thought. The poet has presented a full picture of things that are hidden from the understanding of the ordinary people.

**

The first Mantra pictures the symbolism of the three brothers, the three luminaries in the regions; the three forms of fire : Agni, Vayu (Air) and Aditya (Sun).

Yaskacharya explains that there is indeed only One Deity; and, that Deity manifests in the three worlds as Surya (Sun) in heaven (Dyu-Loka); Indra or Vayu (wind) in the middle region (Antariksha); and, fire on the earth (Bhu-Loka). They are the basic foundations of our existence.

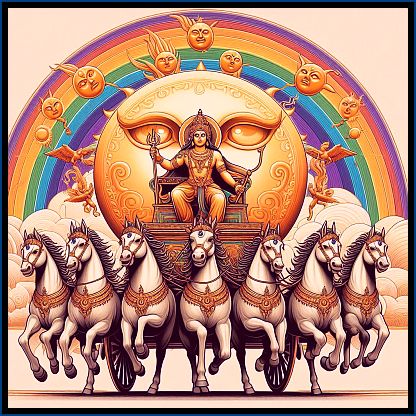

Of these three brothers; Aditya (Sun) shining in the sky, the protector (पलितस्य) of the Universe, who is worshipped by all (वामस्य), is the Supreme. He is accompanied by seven sons (सप्तपुत्रम्), who are not different from himself (his seven rays of seven colours).

The three brothers or the three aspects of Agni (Agni-traya) form the Tripod of Life. They exist and function together.; and, are the basic factors of our existence.

Verses 2 and 3

Immediately after referring to the “beloved invoker grown grey” in verse 1, the imagery of a chariot has been presented; perhaps suggesting movement or the progression of the world emerging out of the first cause.

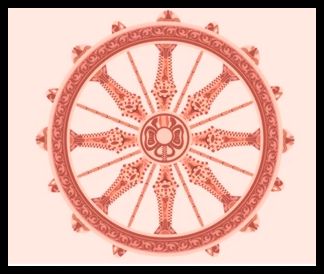

It brings in many terms having symbolic connotations: Chariot (Ratha); Chariot with single wheel (Eka-chakra) and having three naves (Tri-Nabhi); the seven who yoke it; and, a Horse with seven names.

These metaphoric imageries have been discussed by many scholars and interpreted in various ways; each according to the ideologies of the School of thought to which he is affiliated.

**

सप्त । युञ्जन्ति । रथम् । एकचक्रम् । एकः । अश्वः । वहति । सप्तनामा । त्रिनाभि । चक्रम् । अजरम् । अनर्वम् । यत्र । इमा । विश्वा । भुवना । अधि । तस्थुः ॥॥ १.१६४.०२ II

sapta | yuñjanti | ratham | eka-cakram | ekaḥ | aśvaḥ | vahati | sapta-nāmā | tr i-nābhi | cakram | ajaram | anarvam | yatra | imā | viśvā | bhuvanā | adhi | tasthuḥ II 2 II

The seven yoke the one-wheeled chariot; one horse having seven names draws it. The wheel has three navels, never gets old, is never overcome, in which have been remaining all these beings

इमम् । रथम् । अधि । ये । सप्त । तस्थुः । सप्तचक्रम् । सप्त । वहन्ति । अश्वाः। सप्त । स्वसारः । अभि । सम् । नवन्ते । यत्र । गवाम् । निहिता । सप्त । नाम ॥॥ १.१६४.०३ II

imam | ratham | adhi | ye | sapta | tasthuḥ | sapta-cakram | sapta | vahanti | aśvāḥ | sapta | svasāraḥ | abhi | sam | navante | yatra | gavām | ni-hitā | sapta| nāma

Which seven have been remaining on this chariot with seven wheels, those seven horses draw it. The seven sisters utter forth songs together, where are concealed the seven names of the cows.

**

They yoke (युञ्जन्ति) seven horses to the one-wheeled chariot (रथमेकचक्रमेको); and, one horse having seven names (सप्तनामा) draws it along. The wheel has three naves, never gets old, is never overcome. And, in it all the beings and regions of the universe abide.

The chariot is said to represent the cosmos, wherein all the worlds reside; as also the human body, which is conceived as a moving chariot.

Again, it is also said; the chariot represents the universe and its creative process, symbolized by its movement. Its wheel is the symbol of its mobility (Gati). The one horse with seven names is the Time (Kaalo Ashvo vahathi sapta-rasmihi – AV.19.53.1). Its passage provides movement to the creative process.

The sun is compared to a chariot wheel; so is the sky. And, elsewhere the body is compared to a chariot, with the mind as the rein; the sense-organs as the horses; and, the Self as the charioteer.

The single-wheel of the chariot is said to symbolize the basic unity that is essential for propelling along the diverse creative processes of the universe.

[Yaskacharya compares the wheel to the Year (Samvathsara), which rotates endlessly. It may have three distinct periods of Time; Past(भुत)-Present(वर्तमान)-Future (भविस्यत्). Thus, the Time shines in a threefold manner-Trida Nabhati.]

Seven horses, having seven names, are yoked to the chariot. These seven horses are really the same, the difference being only in their names.

Seven sisters ride in it. These seven sisters could either be the seven solar rays , which move in unison like sisters; or the seven portions of a year: Ayana (solstice season), month, fortnight, day, night, hour; seven horses. It might even refer to seven types of speech.

Or, if the term Gavām (गवां) is used in the sense of water, it might mean the seven divine rivers (sapta-sinddhuva) of the Vedic region.

The seven horses could also be compared to the seven rays of the Sun. It may also mean Seven seasons in a year [as per Sri Sayana -six regular seasons and one extra month in the year (अधिक मास –Adhika-masa)].

There is no beginning and there is no end; but there surely is a constant change or transformation that can be felt. Each season has distinctive patterns of weather changes; plant and animal activities; each period with its own special purpose.

The seven rays of the Sun are indeed its seven limbs. And, the seven seasons of the year are the imagined divisions of the invisible Time. The Sun and the seasons are in fact One.

The Sun regulates the time, in which all its movements are encased.

Dhirgatamas uses the extended metaphor of human life span in terms of wheel imagery. This illustration is repeated in the later texts.

The hymn is composed as a riddle (Brahmodya)* with the answer phrased in pun (Slesha-alankara). It describes the ageless cosmic wheel of order, Rta, revolving continuously across the firmament. It is also harmonized with time, involving three naves (three seasons- summer, rainy and winter- through which cycle –Samvatsara-Chakra– the years rotate) and twelve spokes (months).

[ * Brahmodya class of poetry is speculation clothed in riddles and allegories about the wonder of nature, human life, time, language and their interplay. Here, Brahman refers to the statement of truth concerning the symbolic (hidden) connection of things; and the homogeneous net-works established by Yajna.]

The speculative attribute of this wheel is that though it revolves ceaselessly since the times unknown, it is not destined to age, break up or decay (Ajara). Thus, it is faultless (Anarva), devoid of destruction and end. Its aspect is that of subtle unmanifest principle, which is eternal (Sukshma-deham-ashtriyokam).

The world mounted on the cosmic wheel is also subject to rotations. But it is conditioned by aging and decay. Its relation to death and disease is expressed through its mortal aspect – mruthu-bandhu – bound to death- (Sthula-deham-ashritya).

Prof. Wendy Doniger, in her book The Rig Veda An Anthology (Penguin Books) explains:

Working with the implicit and explicit patterns woven into the hymn, it might be possible to decode the hymn.

The sun is often identified with Agni, who is mentioned in the hymn at several points: he is explicitly identified with the One (46); he appears in three forms (1); and he has names that are like long hair (44).

Agni lurks behind other images: he is, like the sun, the first-born child of Order (11, 37, 47) or Truth (cf. 10.5.7) ; and is born of the waters (52).

The interaction of the sun and the waters makes sense of a number of obscure references to a Vedic theory of the rain cycle: the rays of the sun (cows) drink up earthly waters with the lowest point of the ray (the foot) and then give back rain (milk) from their top (head) after they carry the moisture back up to the sun (7, 47, 51, 52). The sun is thus clothed in the waters (7, 31).

The relationship between the sun and the sacrifice (through the concept of the yearly solar renewal and yearly sacrifice) is present in the number symbolism linking the chariot (of the sun) with the sacrifice (as in the extended metaphor of 10.135, the opening verse of which is echoed in verse 22 of the present hymn).

The seven horses or sons or embryos are seven priests or offerings, the three or six or have naves or spokes are seasons (variously enumerated in different sacrificial reckonings), the twelve are the months, the 360 the days of the years (the 720 the days and nights in pairs), and so forth.

Verse 4

In the first three Riks (verses) the Sun and the Time-element are described as being responsible for the sustenance of all the worlds. The next verse goes back to the period before the creation. It poses a series of questions.

This verse is in the Brahmodaya format, posing questions; and, encouraging the student to introspect, to explore and to arrive at credible answers.

कः । ददर्श । प्रथमम् । जायमानम् । अस्थन्वन्तम् । यत् । अनस्था । बिभर्ति । भूम्याः । असुः । असृक् । आत्मा । क्व । स्वित् । कः । विद्वांसम् । उप । गात् । प्रष्टुम् । एतत् ॥ ॥ १.१६४.०४ II

kaḥ | dadarśa | prathamam | jāyamānam | asthan-vantam | yat | anasthā | bibharti | bhūmyāḥ | asuḥ | asṛk | ātmā | kva | svit | kaḥ | vidvāṃsam | upa | gāt | praṣṭum | etat – II 4 II

Who has been seeing the first-born possessing bones, which what has no bones has been bearing? Where then is the life, the blood, the self of the Earth? Who went near the wise to ask this?Who has seen him at the time of his being born (को ददर्श प्रथमं)?

-

- Who was there even before creation?

- Who has seen the first formation of all that exists around us?

- Where then is the life, the blood, the self of the Earth?

- Who went near the wise to ask this?

- Has any inquisitive person, desirous of knowing the origin of the world, approached a true -knower of the cause of all this existence?

*

The latter part of the verses concerns the three fundamental elements of living: Blood (असृक् Asṛk); Life (असुः– Asuḥ); and Spirit (आत्मा– Atmā).

The verse also talks about that which is endowed with substance; that which having bones, having a form (body); and, about that which is bone-less, form-less (sprit) – asthanvantam yad anasthā bibharti.

The question is about the source of these subtle and gross bodies, which are related with the Earth Bhumi), a symbol of Motherhood, which supports us.

The breath and blood may be from the Earth. But, where does the soul come from?

Who seeks and answer to these questions?

Where is the teacher who knows; whom one may approach, ask him questions?

– कः । विद्वांसम् । उप । गात् । प्रष्टुम् । एतत्

Verse 5

पाकः । पृच्छामि । मनसा । अविजानन् । देवानाम् । एना । निहिता । पदानि । वत्से । बष्कये । अधि । सप्त । तन्तून् । वि । तत्निरे । कवयः । ओतवै । ऊँ इति ॥ १.१६४.०५ II

pākaḥ | pṛcchāmi | manasā | avi-jānan | devānām | enā | ni-hitā | padāni | vatse | baṣkaye | adhi | sapta | tantūn | vi | tatnire | kavayaḥ | otavai | oṃ iti

I the unripe, without knowing by my mind, ask about these positions of the gods that are concealed. Over this young calf the poets have spread the seven threads, aye to weave

**

Immature (पाकः) as I am, I ask (पृच्छामि) questions to one who knows the Truth (अत्र॑–क॒वीन्– पृ॒च्छा॒मि॒ –वि॒द्मने॑) about things that are hidden even from the gods. what are the seven threads (सप्त तन्तू), which the sages have spread to envelop the sun, in whom all abide?”

- Here, Surya is called a calf.

- The sages spread seven threads woven upon the young calf.

- Which is this calf?

- What are the seven threads?

It is suggested that these threads might refer to seven forms of the soma sacrifice, or the seven metres (chhandas) of the Vedas.

*

The Sun is said to be at the center of a well-arranged Cosmic System; and the whole world is a garment that envelops the center. This is conceived a as a cloth woven with Seven-threads.

The purpose of the poet is to bring together, in a compact set of verses, a number of Vedic Doctrines concerning the Universe, Cosmology and the Time-principle.

The Universe and the individual are interrelated.

It is also said: As per the ancient practice, a cloth of seven threads is woven year after year. And, each year a new Calf is brought altar for worship. This practice may have roots in the mythical tales, where the sun is rejuvenated each year.

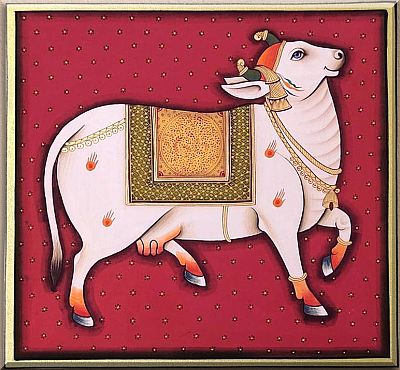

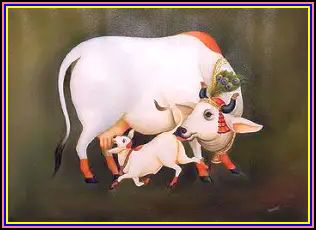

Why is Surya called a calf? Dr. Agrawala explains: Surya is the son of Viraj, the universal Mother Cow; and , when the Cow comes to mortals , she always brings the Calf with her (RV.1.164.17).

But Sri Sayana says: the cow may typify the solar rays collectively and the calf the worshipper.

*

Dhirgatamas cries out: I earnestly desire to know the Truth (पृच्छामि विद्मने.) I seek a teacher who can unveil the Truth.

Verse 6

अचिकित्वान् । चिकितुषः । चित् । अत्र । कवीन् । पृच्छामि । विद्मने । न । विद्वान् । वि । यः । तस्तम्भ । षट् । इमा । रजांसि । अजस्य । रूपे । किम् । अपि । स्वित् । एकम् ॥ १.१६४.०६॥

acikitvān | cikituṣaḥ | cit | atra | kavīn | pṛcchāmi | vidmane | na | vidvān | vi | yaḥ | tastambha | ṣaṭ | imā | rajāṃsi | ajasya | rūpe | kim | api | svit | ekam II 6 II

Not having seen, I ask the poets who have seen, for the sake of knowing, not having known. Who has held apart firm these six regions, what then is that One, in the form of the unborn?

*

This is in continuation of the questions raised in verse 5, where the poet speaks about the beginnings of the formation of the six regions of the physical world from the unborn ultimate reality. He employed the imagery of seven threads that hold the young calf.

They all refer to the emergence and formation of the physical world from out of the unmanifest ultimate reality.

Not having seen, not having known; and, for the sake of knowing, I ask the sages (Kavis) who know the Truth and who have seen: Who is this mysterious unborn one; the One that has established and held firm these six regions. What then is it?

[Sri Sayanacharya explains: The tradition counts seven regions (Lokas); the seventh being the Sathya-Loka, which is beyond the uninitiated, tied to the mundane world of rituals. The other six Lokas (shad-rajamsi) which are said to be created by the movement of the Rajo-Guna are: Bhu (Earth); Bhuvaha (Mide-region); Followed by Four types of Heavens: Suvaha (Heaven); Mahaha; Janaha; and Tapaha.]

As regards the phrase अ॒जस्य॑ । रू॒पे । किम् । अपि॑ । स्वि॒त् । एक॑म्, Sri Sayana says term Ajasya (Aja- the unborn) refer to Aditya, the eternal one, who has created seasons according to the period of the year

*

This and the previous Mantras wonder about the formation of the existence from out of the unborn, non-existent, ultimate reality.

Verse 7

इह । ब्रवीतु । यः । ईम् । अङ्ग । वेद । अस्य । वामस्य । निहितम् । पदम् । वेरिति वेः । शीर्ष्णः । क्षीरम् । दुह्रते । गावः । अस्य । वव्रिम् । वसानाः । उदकम् । पदा । अपुः॥१.१६४.०७॥

iha | bravītu | yaḥ | īm | aṅga | veda | asya | vāmasya | ni-hitam | padam | veri tiveḥ | śīrṣṇaḥ | kṣīram | duhrate | gāvaḥ | asya | vavrim | vasānāḥ | udakam | padā | apuḥ II 7 II

Let him declare here who surely knows this—the con[1]cealed position- of this lovable bird. From his head the cows draw milk; they have been drinking the water with their foot, wearing the vesture

**

Let him, who surely knows the Truth, declare here (इह ब्रवीतु)— the concealed position of this lovable bird (वेदा॒स्य–वामस्य). From his head the cows draw milk; they have been drinking the water with their foot, wearing the vesture.

The Sun, Aditya, who is constantly moving has an attractive luminous form. His rays emanating from his shining abode, concealed (निहितं) in the high skies (शी॒र्ष्णः), pour rains on to the earth. And, the same rays (गावः॑) absorb back those waters (उदकं) through the very path (पदा) they poured the rains.

[ Dhirgatamas employs here the imagery of cow (गावो) and milk (क्षीरं) to suggest sun-rays and rains that sustain life on this planet. The rays of the Sun (cows) absorb fluids from all sources, including vegetation; and, convert them into life-giving milky substance (rains) that generates and protects life.

Similarly, the ordinary cow too drinks water; and converts it into the precious life-nurturing milk.

The Earth too is also a sort of Mother Cow. It absorbs rains and gives life to vegetation, which sustains our lives.

Similar is the sun-rays, they shine, give light and heat; take away moisture from the Earth; and then send back life through rains.

This analogy is extended to the relation between the senses and human body. The physical body consumes food, which nourishes the mind (brain); which again controls the body mechanism

Thus, the metaphors of cow-water-milk seems to hold good in a number of cases.]

**

The Universal-Cow-principle (Gauh-tattva) was seen as a symbol of the Thousand-syllabled speech

Vag va idam Nidanena yat sahasri gauh; tasya-etat sahasram vachah prajatam –4.5.8.4.

Vac (speech) is depicted as a milch-cow that provides nourishment; and one which is accompanied by her calf. She constantly cuddles her calf with great love, and lows with affection for her infant

In the traditional texts, Vac, which expresses the wonders and mysteries of the Universe, was compared to the wish-fulfilling divine cow

dhenur vagasman, upasustutaitu –RV. 8.100.11.

Thus, Gauh-Vac is symbolically portrayed as cow. It is hailed in the Rig-Veda (8.101.15) as the mother principle, the source of nourishment (pusti) of all existence; and bestowing immortality (amrutatva).

[ Commenting upon verses 4-7, Dr. Kunhan Raja explains:

These four verses form a unit. Who has seen this mystery of the first formation of the universe? Who can go and ask about this? And where is the location of that mystery? This is the general idea in verse 4, after describing the chariot and the wheel and the various things concealed in the chariot or its wheel (in verses 2 and 3). The same question is repeated in the next verse.

The poet changes over to the first person. He asks about the concealed position of the gods. The poets have woven some mystery (verse 5). Poets know who gave form to the universe (verse 6). The milk drawn from the head, and the drinking of water with the foot are also puzzles in verse 7.

Here there is a mention of the concealed position of “this lovable” bird. The same words, used as in verse 1, show that there is some relation between that of which there are the brothers (verse 1) and the bird whose position is concealed (verse 7).

The close relation of ideas must also be noted as: where all these beings stood (verse 2), the incorporeal bears the corporeal (verse 4), and who has held firm the six regions in the form of the unborn (verse 6).

Then there are the parallels like: one horse with seven names draws the chariot (verse 2), where the seven names of the cows are concealed (verse 3), and these concealed names of the gods (verse 6).

There is also the antithesis of the poet who is the author and who does not know and the poets who know, mentioned in verse 5 and verse 6. Certainly, the poet had been thinking of some mystery of the universe, its origin and the distinction between the formed and the formless. The cows draw milk from its head (verse 7), the secret names of the cows (verse 3); in the young calf (verse 5). Here also there are indications of some common idea about cows.]

Verse 8

माता । पितरम् । ऋते । आ । बभाज । धीती । अग्रे । मनसा । सम् । हि । जग्मे । सा । बीभत्सुः । गर्भरसा । निविद्धा । नमस्वन्तः । इत् । उपवाकम् । ईयुः॥ १.१६४.०८ ॥

mātā | pitaram | ṛte | ā | babhāja | dhītī | agre | manasā | sam | hi | jagme | sā |bībhatsuḥ | garbha-rasā | ni-viddhā | namasvantaḥ |it| upa-vākam | īyuḥ II 8 II

The mother has been giving the father the share in the Rta indeed, she has been coming together with thought and with mind, in the beginning. She is timid, having the juice within, being hit into. There they came bearing adorations, to address nearby.

*

The mother, (माता -earth), worships (बभाज) the father, (पि॒तर॑म् -Sun), with holy rites (Yajnas), for the sake of water; but he, in his mind, has anticipated (her wants); whereupon desirous of progeny, she is penetrated by the dews of impregnation (गर्भरसा), and, (all) expectant of abundance, exchange words (of congratulation).”

The earth is usually the mother; and the heaven is the father. The term Dhiti (धीती) is Dhyana– intense contemplation. Manas (मनसा) is thought. The mother went close to the father. She was shy (बीभत्सुः) and full of joy.

The earth is drenched (उपवाकम्) by the rain-waters, enabling it to produce crops and also to generate and sustain life.

[Sri Sayana opines that in this verse, a conjugal relation between the Earth and the Sun is imagined. Mother Earth desires water for production; approaches the Sun, who satisfies her with heat, light and rains. These elements unite the Earth (उपवाक)with the Sun.]

Verse 9

युक्ता । माता । आसीत् । धुरि । दक्षिणायाः । अतिष्ठत् । गर्भः । वृजनीषु । अन्तरिति । अमीमेत् । वत्सः । अनु । गाम् । अपश्यत् । विश्वरूप्यम् । त्रिषु । योजनेषु ॥१.१६४.०९॥

yuktā | mātā | āsīt | dhuri | dakṣiṇāyāḥ | atiṣṭhat | garbhaḥ | vṛjanīṣu | antariti |amīmet | vatsaḥ | anu | gām | apaśyat | viśva-rūpyam | triṣu | yojaneṣu II 9 II

The mother was tied on to the yoke of the right side; the womb has been remaining within the water-cloud. The calf lowed, looked towards the cow having all forms, in the three expanses of space.

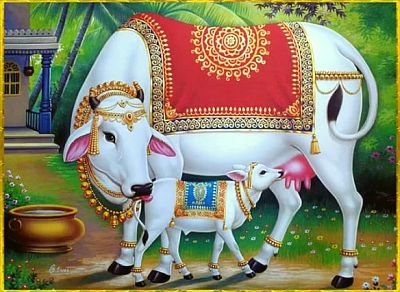

The Dyu-Loka, the mother of all creations, (sky), was engaged in her duty of sustaining and protecting the earth, which fulfils all her desires (युक्ता–माता–आसीत्). The embryo (water) rested within the womb of the clouds. And, as soon as it was delivered, the calf (water) bellowed (made sounds while raining), and beheld the cow (earth) with its forms (अनु –अपश्यत्), in its three combinations (त्रिषु । योजनेषु) of the clouds, the wind and the Sun-rays.

Dr. Raja writes: The idea of a union of the mother (माता) and the formation of a Garbha (गर्भः – womb or pregnancy), is clear in the first half. In the second half, there is mention of the calf (वत्सः) that bellowed (अमीमेत्) and looked (अपश्यत्) at the Great Mother Cow (दक्षिणाया), which had countless manifestations (विश्वरूप्यम्). There upon the clouds thundered.

It may perhaps mean: the rains (calf) met the Mother- Earth in its various forms, textures and colors; producing countless varieties of crops and vegetations, with the help of the clouds, the wind, and the rays of the sun.

[Sri Sayana comments: The calf bellowed; the cloud thundered; the all-protecting cow: viśvarūpyam gām triṣu yojaneṣu = the earth diversified by various crops in consequence of the co-operation of the cloud, the wind, and the rays of the sun.

in the early texts, the cow is compared to Earth as an exemplary symbol of Motherhood. She is the life-giving, nourishing Mother par excellence, who cares for all beings and nature with selfless love and boundless patience.

Further, the nourishing and life-supporting rivers too are compared to cows (e.g. RV. 7.95.2; 8.21.18). For instance; the Vipasa and the Sutudri the two gentle flowing rivers are said to be like two loving mothers , who slowly lick their young-lings with care and love (RV . 3,033.01)

– gāveva śubhre mātarā rihāṇe vipāṭ chutudrī payasā javete ]

*

[ The symbolisms associated with Father and Mother; Cow and the calf; keep changing.

The terms are context-sensitive. And, it is not easy to decode. To say the least; it is often confusing too.

For instance, in the previous verse: Father (पितरम्) stood for the sky; while the Earth meant the mother (माता). And, in the verse 9, the Sky (Dyu-Loka) is referred to as the mother of all creations.

Here, the clouds are the mother; and, water is its calf. It says, the calf, which was in the womb (गर्भः), as soon as it was delivered, bellowed; looked at (अपश्यत्) and met the Great Mother Cow (Earth), in her varied forms. All were happy.]

Verse 10

तिस्रः । मातॄः । त्रीन् । पितॄन् । बिभ्रत् । एकः । ऊर्ध्वः । तस्थौ । न । ईम् । अव । ग्लपयन्ति । मन्त्रयन्ते । दिवः । अमुष्य । पृष्ठे । विश्वविदम् । वाचम् । अविश्वमिन्वाम् ॥ १.१६४.१० ॥

tisraḥ | mātṝḥ | trīn | pitṝn | bibhrat | ekaḥ | ūrdhvaḥ | tasthau | na | īm | ava | glapayanti | mantrayante | divaḥ | amuṣya | pṛṣṭhe | viśva-vidam | vācam | aviśva-minvām II 10 II

Bearing the three mothers, the three fathers. One has been standing upright; they do not fatigue him down. Behind of that heaven they utter in a low voice the word that com[1]prehends all, that does not move all –aviśva-minvām

**

The three verses (8 to 10) form a group. They speak about the father and the mother; and of the womb and the calf. It is explained that the Three mothers( तिस्रः –मातॄः ) and three fathers (त्रीन् पितॄन् ) refer to the three worlds, Earth, Sky, Heaven; and to the three deities presiding over them (ऊर्ध्वः तस्थौ ) : Agni, Vayu, Surya, who are the protectors of the three worlds.

The gods (दिवः) chant (ग्लपयन्ति मन्त्रयन्ते) the glories of Aditya (Sun), Aja, the one who stands above all (ऊर्ध्वः-तस्थौ), in a language that can be understood by all (viśvavidam vācam aviśvaminvām); and also, in a language that many may not even know (a-sarvavyāpinīm).

*

It is explained: Aditya, on the summit of the sky, alludes here to the Time-element, which is eternal and indivisible. Everything is born and dies in Time.

Aditya, the Time, is perpetual and inseparable. It is absolute. The year (Samvathsara) is a unit of Time. The events such as: birth, growth and death are measured in the sub-elements of the year, such as: the months, weeks, days, Mahurtha, Kshna (seconds) , and Lava ( sub-units of a second).

Perhaps the main idea is continued in the following verses also.

The first ten verses are said to deal with zodiac- astrophysical – questions and the related speculations.

Many scholars have surmised that, in a way, these verses have cosmological implications. And the numbers – 3,5,7 and 12- mentioned there in; as also the references to horses, chariots, wheels and yokes are symbolic references to planetary positions and movements.

They also serve as code-symbols of metaphysical principles at several levels of this universe.

The meaning or the intent underlying these are elastic, amenable to be interpreted in any number of ways.

The celebrated scholar David Frawley, in his article on the Vedic origins of the zodiac hymns of Dhirgatamas explains: (the following are a few extracts)

The hymns of Dhirgatamas speak clearly of a zodiac of 360 degrees, divided in various ways, including by three, six and twelve, as well as related numbers of five and seven.

In regard to the planetary rulership of the twelve signs, Dhirgatamas shows the mathematical basis of such harmonic divisions of a zodiac of 360 degrees.

If we examine the verse, we see that a heavenly circle of 360 degrees and 12 signs is known, along with 7 planets. It also has a threefold division of the signs which can be identified with that of fire, wind and Sun (Aries, Sagittarius and Leo) ; and a sixfold division that can be identified with planets each ruling two signs of the Zodiac. This provides the basis for the Zodiac and the signs we have known historically. We have all the main factors for the traditional signs of the Zodiac, except for the names and symbols of each individual sign.

The number 3 (in verse 1) is said to refer to the Triad of three brothers – Agni on Earth; the wind (Vayu) in the mid region; and Sun (Surya), the symbol of Supreme Light, in the heavens.

The heavenly space has 7 astronomical bodies: the sun, moon and five planets.

The twelve signs of Zodiac are also divided in a similar manner. Aries or Mars ruled by the principle of Fire; then Sun or Leo; and Sagittarius the atmospheric wind ruled by Jupiter the god of rains.

The Vedic horse (Ashva) is the symbol of energy or propulsive force.

*

There is a mention to The Father with five feet and twelve forms. He dwells in the higher half of heaven full of waters.

It is surmised that it refers to Sun (father) and the five planets or the five elements. And, his twelve forms are the twelve Zodiac signs.

The Sun in the higher half of heaven is with the other five planets – being his five feet, each ruling two signs.

In Vedic thought, the Sun is the abode of the waters, which we can see in the zodiac by the proximity of the signs Cancer and Leo.

*

There is another reference to number 5. The poem says: Revolving on the five-spoked wheel all beings stand. Though it carries a heavy load, its axle does not over heat or break.

The five-spoked wheel is again the zodiac ruled by five planets and five elements and their various internal and external correspondences.

*

There are many places where the number seven occurs, alone and in combination.

The poem say that the seven yokes of the chariot have a single wheel (Eka-chakra). One horse that has seven names caries it. The wheel has three naves. It is un-decaying and never overcome, where all these beings are placed.

The Zodiac is the single wheeled chariot or circle yoked by seven planets which are all forms of sun or sunlight. It is the wheel of time on.

*

The sevenfold wheel is the zodiac moved by the seven planets. The six spokes are the six double signs through which the planets travel.

According to Dhirgatamas, the sun has ‘seven heroes’ for sons, and he rides ‘seven yoked chariot, one wheeled’,

The verse 14 says: The un-decaying wheel (circle) together with its felly (circumference), ten yoked to the upward extension carry it. The eye of the Sun moves encompassing the region. In it are placed all beings.

This may again refer to the ten signs ruled by the five planets, with each planet ruling two signs. The eye of the Sun may be the sign Leo through which the solar influence pervades the zodiac or just the Sun itself. The upward extension may be the polar region.

*

Verse 48 mentions a wheel having three naves. They are held together by 360 spokes, moving and non-moving

This perhaps refers to the zodiac of twelve signs and three hundred and sixty degrees.

The circle of the zodiac has twelve signs. It has 720 half degrees or twins, making 360 total.

The 360 spokes are the 360 degrees which revolve in the sky but remain in the same place in the zodiac. This may mean the 360 subdivisions within the 720:360 octave matrix.

The wheel is the year; the twelve spokes are the twelve months; the seven hundred and twenty children of Agni are 360 days and 360 nights of solar year.

The twelve spokes are twelve tones of an octave tonal-zodiac. The three naves may the three prime numbers ,2,3, and 5, each rotating in the sense of its own speed, correlated with the terminating number which includes all three along its factors.

In the subsequent instalments of this series,

let us briefly go through the remaining Verses of

CONTINUED

IN THE

NEXT PART

References

- A History Of Pre-Buddhistic Indian Philosophy: Benimadhab Barua : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- A History of Pre-Buddhistic Indian Philosophy: Benimadhab Barua : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- https://aseemamag.com/vedic-origins-of-the-zodiac-hymns-of-dirghatamas-in-the-rig-veda/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359710805_Description_of_Twelve_Zodiac_Signs_in_Ancient_Indian_Texts

- ALL IMAGES ARE FROM INTERNET